CAITLIN MURRAY 2 Message from the Director Mensaje de la Directora

ROBERTO TEJADA 6 Zoe Leonard: Al río / To the River The Chinati Foundation, October 2024–July 2025 La Fundación Chinati, octubre de 2024 – julio de 2025

ERICA COOKE AND JULIAN ROSE 30 Latent Permanence: On Donald Judd’s Concrete Buildings Permanencia latente: sobre los edificios de hormigón de Donald Judd

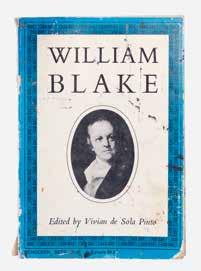

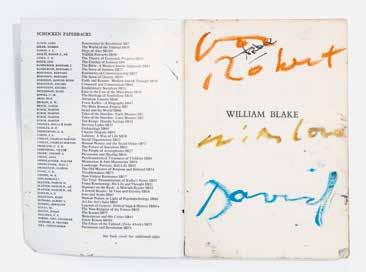

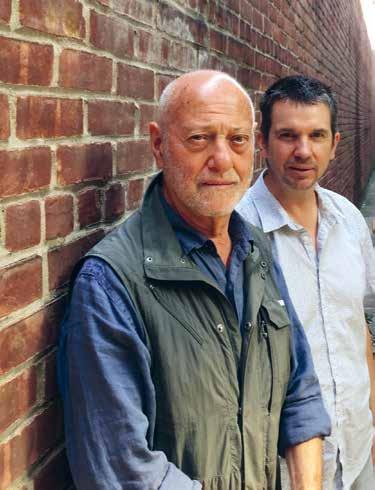

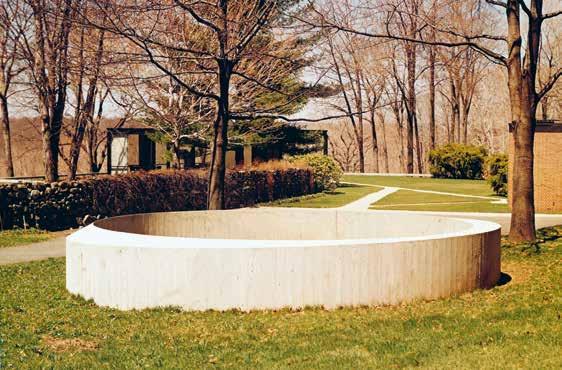

ROBERT ARBER, JOHN BEECH, AND TIM JOHNSON 44 “Energy Is Eternal Delight”: A Conversation on David Rabinowitch “La energía es un deleite eterno”: una conversación sobre David Rabinowitch

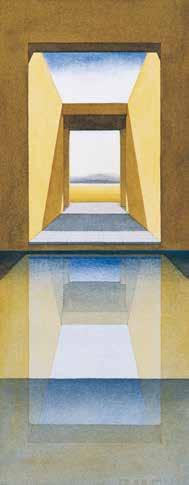

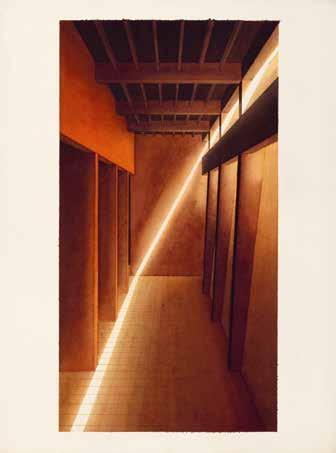

REBECCA SIEFERT 50 Lauretta Vinciarelli and the Arena of Influence Lauretta Vinciarelli y la arena de la influencia

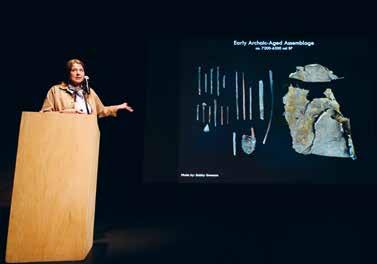

CAITLIN MURRAY 58 Art in Context , Part I: Opening Remarks Arte en contexto , parte I: discurso de apertura

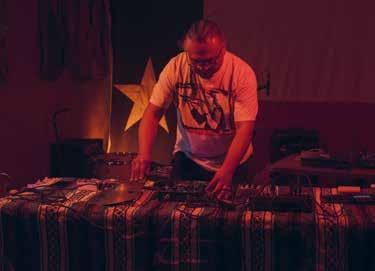

NATHAN YOUNG AND CAITLIN MURRAY 68 The Ch’íná’itíh (Chinati) Intertribal Noise Symposium: A Conversation with Nathan Young El Simposio Intertribal de Noise Ch’íná’itíh (Chinati): una conversación con Nathan Young

ZADE WILLIAMSON 74 Conservation Report Informe sobre la conservación

HALEY LEVIN 76 Education Report Informe sobre la educación

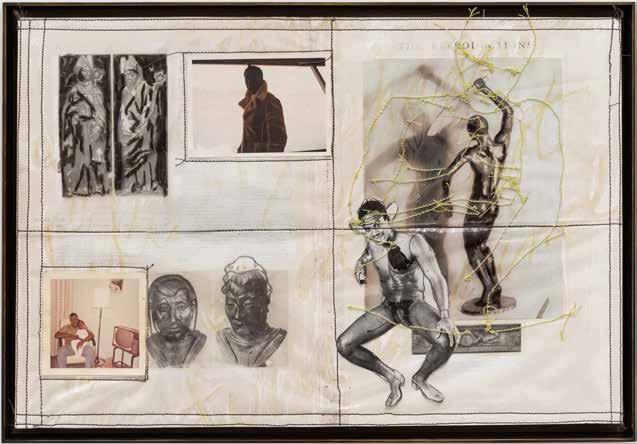

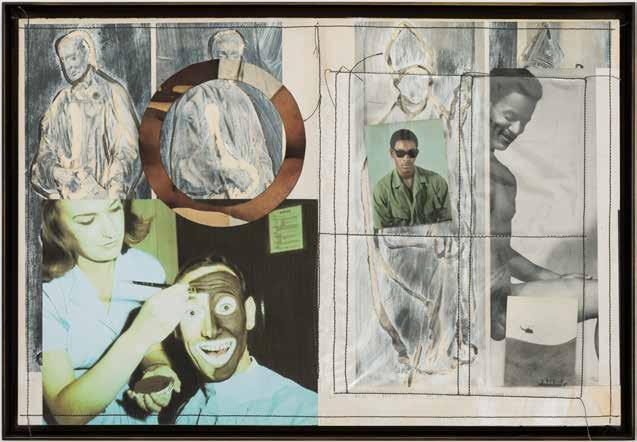

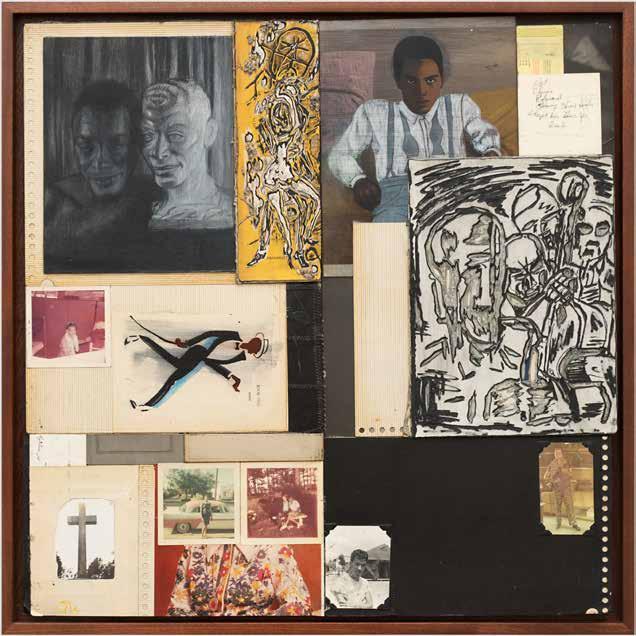

Artists in Residence 2024–2025 80 Troy Montes Michie

Artistas en Residencia 2024–2025 82 Willie Binnie

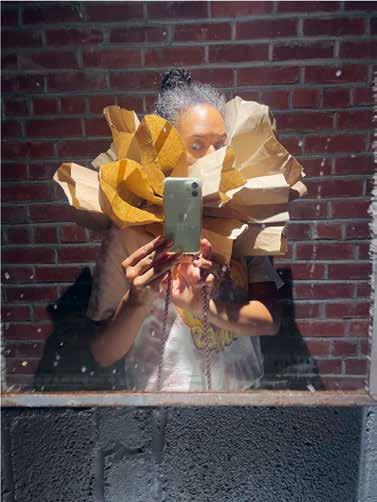

84 Leslie Cuyjet

86 dean erdmann

90 Membership Edition: Katharina Grosse Edición para los afiliados: Katharina Grosse

92 The Year in Public Programs El año en programas públicos

98 Staff News Noticias sobre nuestro personal

99 Internship Program Programa de prácticas

100 Funding and Membership Financiación y Afiliación

103 Board of Trustees and Staff Junta directiva y Personal

104 Colophon and Image Credits Colofón y Atribuciones de imagen

This year, the Chinati Foundation has continued our commitment to gathering voices in ways reflective of Donald Judd’s vision for Chinati, where he hoped that “art, all of the arts, in fact all parts of the society, have to be rejoined, and joined more than they ever have been.” Since October 2024, we’ve proudly hosted two symposia, a series of readings and conversations on Zoe Leonard’s Al r í o / To the River , and a weeklong Grassland Restoration Practicum, alongside many other programs and events.

Last fall, Chinati opened the first institutional exhibition of Zoe Leonard’s Al río / To the River in the Americas. Leonard’s work, which consists of photographs taken along the 1,200mile stretch where the Rio Grande/ Río Bravo is used to demarcate the international boundary between Mexico and the United States, was installed across three buildings of Chinati’s campus. Leonard’s installation offered a compelling formal language through which to examine the convergence of ecological, cultural, architectural, historical, and artistic concerns that shape Chinati today. In conjunction with Al río / To the River , we hosted artists, archaeologists, poets, historians, and curators, whose contributions are outlined in the “Year in Public Programs” section of this newsletter. These programs provided vantages from which to consider the confluence of interests that characterize Leonard’s work. It is from La Junta de los Rios, sixty miles south of Marfa where the Conchos River and Rio Grande meet, that we learn confluence promotes both ecological and cultural richness.

Este año, la Fundación Chinati ha reafirmado su compromiso de reunir voces de manera que reflejen la visión de Donald Judd para Chinati, donde anhelaba que “el arte, todas las artes, de hecho todas las partes de la sociedad, volvieran a unirse, y más profundamente de lo que nunca lo han estado”. Desde octubre de 2024, hemos tenido el honor de acoger dos simposios, una serie de lecturas y conversaciones en torno a Al río / To the River , de Zoe Leonard, y un programa de Prácticas de Restauración de Praderas de una semana, entre otros muchos programas y eventos.

El pasado otoño, Chinati inauguró la primera exposición institucional en América de la obra Al río / To the River , de Zoe Leonard. La obra —compuesta por fotografías tomadas a lo largo de los 1.931 kilómetros donde el Río Bravo/Rio Grande marca la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos— se instaló en tres edificios del campus de Chinati. La instalación de Leonard ofreció un lenguaje formal poderoso desde el cual examinar la convergencia de preocupaciones ecológicas, culturales, arquitectónicas, históricas y artísticas que hoy conforman Chinati. Junto con Al río / To the River , recibimos a artistas, arqueólogos, poetas, historiadores y comisarios de arte, cuyas contribuciones se detallan en la sección “El año de programas públicos” de esta publicación informativa. Estos programas ofrecieron miradas diversas desde las cuales considerar la confluencia de intereses que caracteriza la obra de Leonard. Es desde La Junta de los Ríos —a unos noventa y siete kilómetros al sur de Marfa, donde se encuentran el Río

Conchos y el Río Bravo— que aprendemos que la confluencia promueve tanto la riqueza ecológica como la cultural. En marzo de 2025, Chinati se asoció con el artista y académico Nathan Young

In March 2025, Chinati partnered with the artist and the scholar Nathan Young and the Marfa-based curatorial platform Atomic Culture to present the Ch’íná’itíh (Chinati) Intertribal Noise Symposium, a weekend of performance and dialogue. As Young describes in this volume, the goal of the symposium was to “create a site of cultural convergence, experimentation, and agency.” Young conceived of the symposium as a gathering, bringing together a community of artists around sound, while also attuning a new community of listeners to the expansive, adaptive, and culturally resilient qualities of noise. At Chinati, where artists have installed work in the context of architecture and land, Young reminds us that “sound can be both material and spatial when played in the right context.” The integration of art, architecture, and land—as exemplified by Donald Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill

y la plataforma marfeña de conservación Atomic Culture para presentar el Simposio Intertribal de Noise Ch’íná’itíh (Chinati), un fin de semana con performances y diálogos. Como describe Young en esta edición, el propósito del simposio fue “crear un lugar de convergencia cultural, experimentación y capacidad de acción”. Young concibió el simposio como un encuentro que reuniera a una comunidad de artistas en torno al sonido, al tiempo que sintonizaba a una nueva comunidad de oyentes con las cualidades expansivas, adaptativas y culturalmente resistentes del noise . En Chinati, donde los artistas han instalado sus obras en relación con la arquitectura y la tierra, Young nos recuerda que “el sonido puede ser tanto material como espacial cuando se presenta en el contexto adecuado”.

La integración de arte, arquitectura y paisaje —ejemplificada por las 100 obras sin título en aluminio en bruto de Donald Judd— fue el foco del simposio

aluminum—was the focus of Art in Context: Art, Architecture, and the Middle Landscape , a two-part symposium cohosted by Chinati and the Rice School of Architecture in April. One point of inspiration for developing this symposium was a study of two previous Chinati symposiums: Art in the Landscape , from 1995, and Art and Architecture , from 1998. These convenings set the precedent for discussions of Judd’s work and the scope of concerns he established for Chinati. There, artists, architects, and historians gathered to address a general topic resulting in a rich diversity of sometimes consonant, sometimes dissonant, positions and methodologies.

With this precedent in mind, each of the participants of this year’s symposium addressed how context impacts our experience of art and architecture, with lectures by the architects

Arte en Contexto: arte, arquitectura y el paisaje intermedio , copresentado por Chinati y la Escuela de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Rice en abril. Una de las inspiraciones para desarrollar este simposio fue el estudio de dos encuentros anteriores en Chinati: Arte en el paisaje (1995) y Arte y arquitectura (1998). Aquellas reuniones establecieron el precedente para los debates sobre la obra de Judd y el alcance de las preocupaciones que definió para Chinati. Allí, artistas, arquitectos e historiadores se reunieron para abordar un tema común, generando una riqueza de posturas y metodologías a veces disonantes, a veces en armonía.

Siguiendo ese ejemplo, los participantes del simposio de este año reflexionaron sobre cómo el contexto transforma nuestra experiencia del arte y la arquitectura, con ponencias de los arquitectos Carme Pigem, Tatiana Bilbao y Alberto Kalach, y conversaciones con los artis -

Carme Pigem, Tatiana Bilboa, and Alberto Kalach and conversations with the artists Larry Bell and Christopher Wool. A panel discussion with the art and architecture historians Shantel Blakely, Erica Cooke, Julian Rose, and Richard Shiff focused on Judd’s vision for the integration of his 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, the former artillery sheds in which they are housed, and the land on which the buildings were sited. Additionally, the symposium addressed site and landscape, turning from Land art and, instead, addressing the concept of the titular Middle Landscape. Key to this discussion was the consideration, articulated by the landscape architects Rosetta Elkin, Maggie Tsang, and Isaac Stein, that Chinati, although located in the Chihuahuan Desert, is sited on land heavily damaged by previous military use. Here, it proved productive to explore a concept that provides alternatives

tas Larry Bell y Christopher Wool. Una mesa redonda con los historiadores del arte y la arquitectura Shantel Blakely, Erica Cooke, Julian Rose y Richard Shiff se centró en la visión de Judd para la integración de sus 100 obras sin título en aluminio en bruto, los antiguos cobertizos de artillería que las albergan y el terreno sobre el cual se sitúan. Además, el simposio abordó el tema del emplazamiento y el paisaje, no desde el arte de la tierra ( Land art ), sino desde la idea del Paisaje Medio, el Middle Landscape que da nombre al encuentro. Fundamental para esta reflexión fue la observación, articulada por los arquitectos paisajistas Rosetta Elkin, Maggie Tsang e Isaac Stein, de que Chinati, aunque ubicado en el desierto de Chihuahua, está asentado sobre tierras fuertemente dañadas por el uso militar anterior. Resultó fértil, entonces, explorar un concepto que proponga alternativas a las narrativas binarias del paraíso rural y del poder urbano,

to conventional binary narratives of rural arcadia and urban power, neither of which apply to Judd’s work in Marfa.

Later in April, as the weather began to warm, we hosted our second Grassland Restoration Practicum. The practicum provided a small group of local participants a paid opportunity for direct mentorship and fieldwork in the techniques of grassland stewardship on Chinati’s grounds. In this weeklong program, regional experts working in soil science, biology, conservation, land and water management, and agronomy demonstrated methods to promote healthy grasslands utilizing the six courtyards of Dan Flavin’s untitled (Marfa project) as a case study. Fundamental to the pedagogy was the understanding that our experience of the art at Chinati is intertwined with our experience of the land, necessitating

ninguna de las cuales se ajusta a la obra de Judd en Marfa.

Más tarde en abril, con el inicio del calor, organizamos nuestras segundas Prácticas de Restauración de Praderas. Este programa brindó a un pequeño grupo de participantes locales una oportunidad remunerada de mentoría directa y trabajo de campo en técnicas de gestión de praderas en los terrenos de Chinati. A lo largo de la semana, expertos regionales en suelos, biología, conservación, gestión de agua y tierra, y agronomía compartieron métodos para promover praderas saludables, utilizando los seis patios del untitled (Marfa project) [sin título – proyecto Marfa] de Dan Flavin como caso práctico. Un principio fundamental de esta pedagogía es la comprensión de que nuestra experiencia artística en Chinati está entrelazada con nuestra experiencia de la tierra, lo cual exige una aproximación cuidadosa y consciente a la conservación. Como

a careful and considered approach to conservation. As Sterry Butcher beautifully reminded us in her reflection of last year’s practicum, “Turns out, people do care. They care about each other, and they care about the land. Turns out there’s a lot of room for optimism.”

We are grateful to our members, Director’s Circle, Board of Trustees, and all of our guests for providing us with the ability to support Chinati’s vitality by gathering in all these ways. Each year, through the newsletter, we also gather in print to give voice to our recent work and to deepen our understanding of the art and artists that shape the Chinati Foundation. We thank you for joining us in these pages and hope you will join us as a member of Chinati.

Caitlin Murray

nos recordó bellamente Sterry Butcher en su reflexión sobre las prácticas del año pasado: “Resulta que a la gente sí le importa. Se preocupan los unos por los otros, y se preocupan por la tierra. Resulta que hay mucho espacio para el optimismo”.

Agradecemos profundamente a nuestros miembros, al Círculo de la Directora, a la Junta Directiva y a todos nuestros visitantes por permitirnos apoyar la vitalidad de Chinati al reunirnos de todas estas maneras. Cada año, a través de esta publicación informativa, también nos reunimos en papel para dar voz al trabajo reciente y profundizar en la comprensión del arte y los artistas que dan forma a la Fundación Chinati. Gracias por acompañarnos en estas páginas. Esperamos que también lo hagan como miembros de Chinati.

Caitlin Murray

THE CHINATI FOUNDATION

OCTOBER 2024–JULY 2025

LA FUNDACIÓN CHINATI

OCTUBRE DE 2024 – JULIO DE 2025

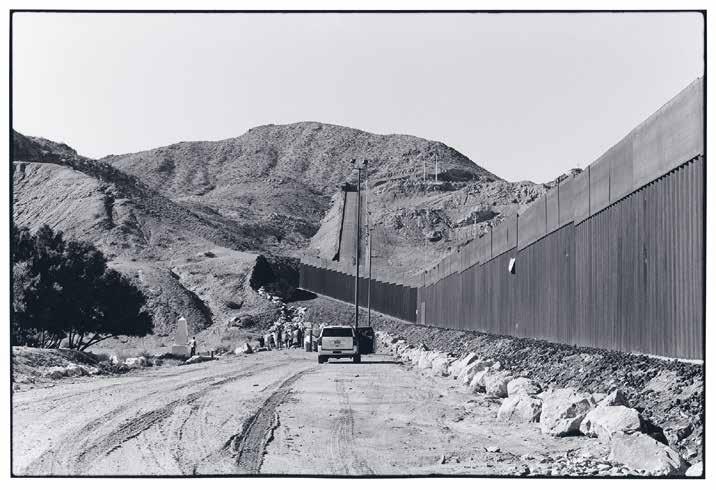

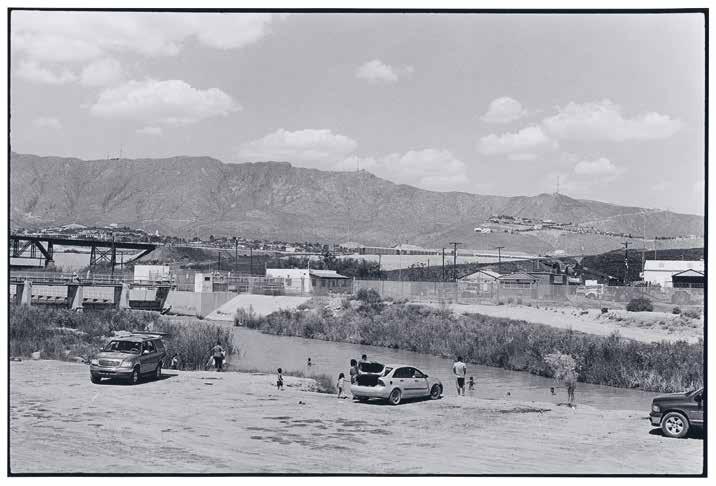

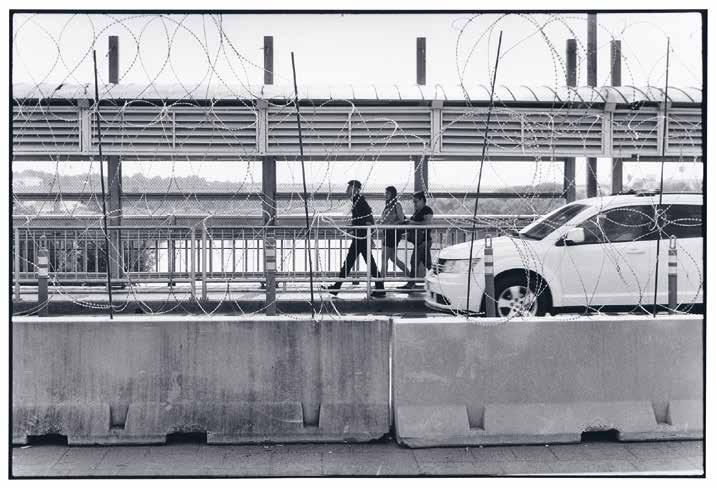

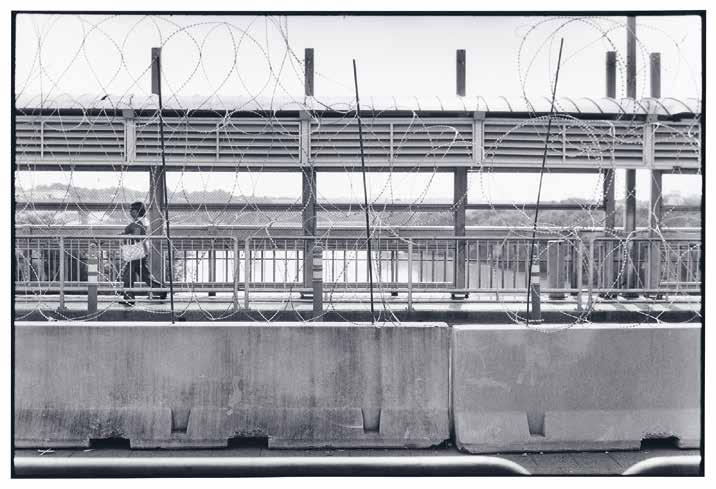

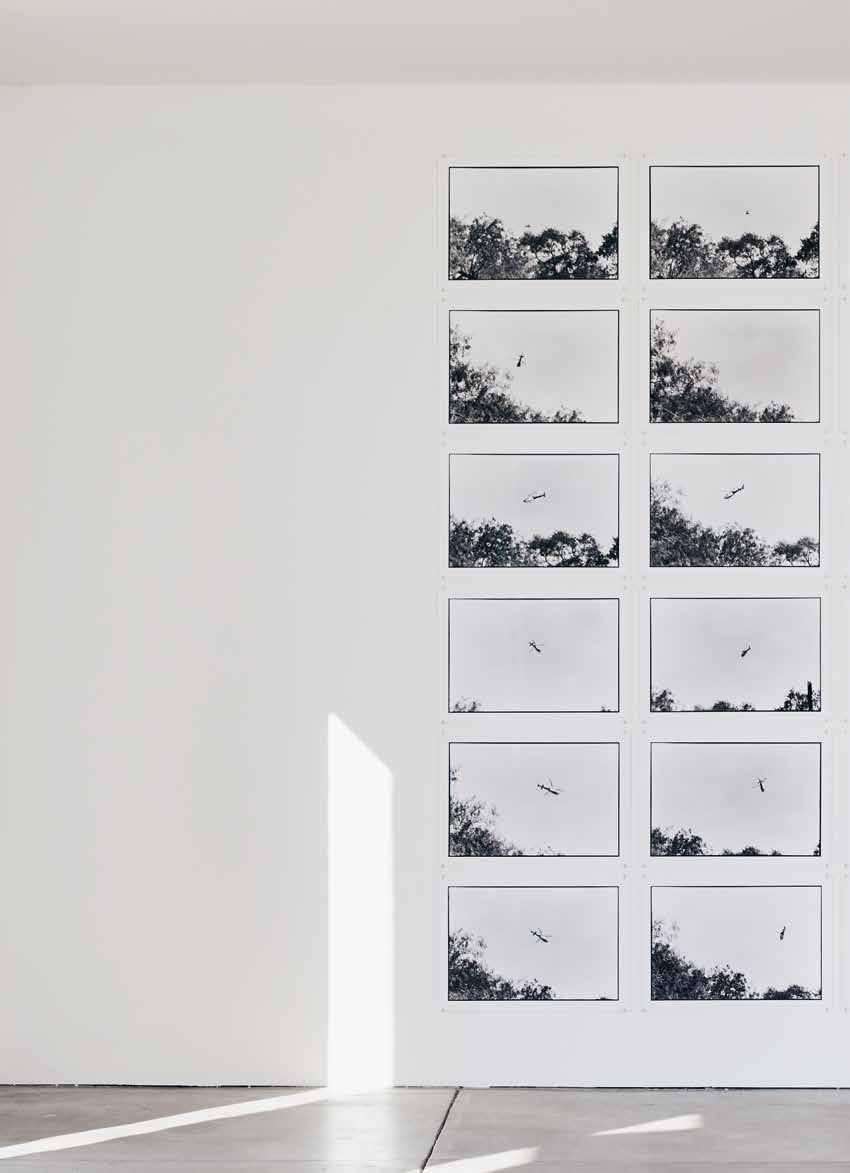

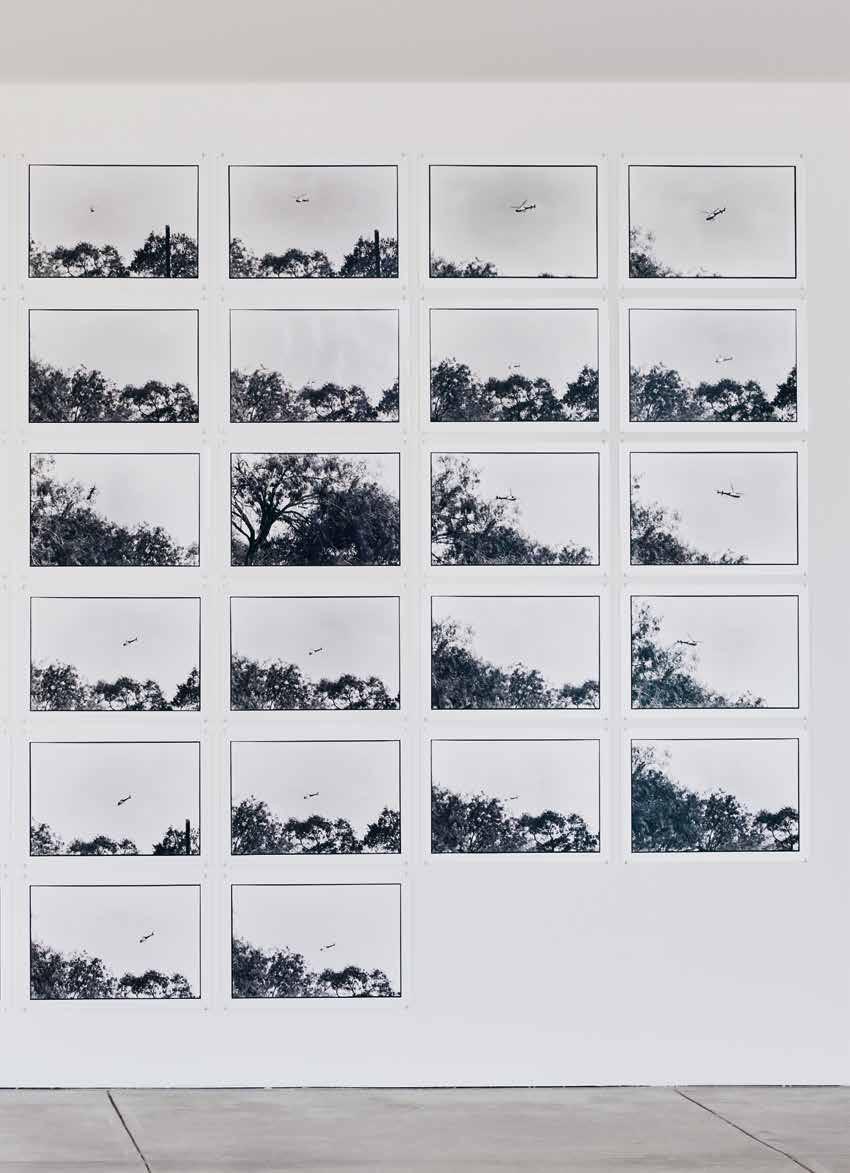

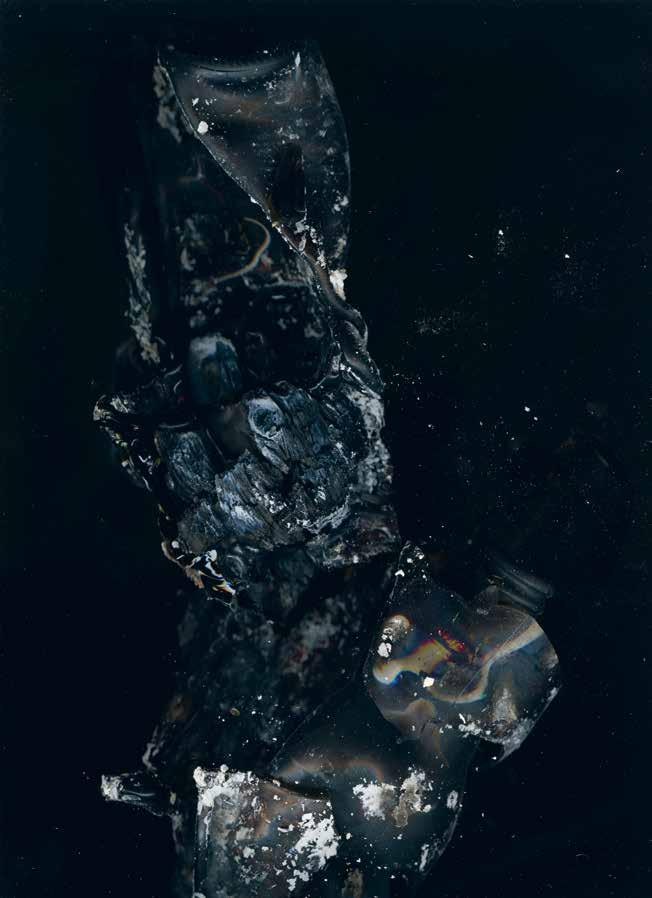

PAGES 4–29: ZOE LEONARD: AL RÍO / TO THE RIVER . INSTALLATION VIEWS, THE CHINATI FOUNDATION, 2024, AND ZOE LEONARD, AL RÍO / TO THE RIVER (DETAILS), 2016–22. GELATIN-SILVER PRINTS, C-PRINTS, AND INKJET PRINTS / PÁGINAS 4–29: ZOE LEONARD: AL RÍO / TO THE RIVER . VISTAS DE LA INSTALACIÓN, LA FUNDACIÓN CHINATI, 2024, Y ZOE LEONARD, AL RÍO / TO THE RIVER (DETALLES), 2016–22. IMPRESIONES EN GELATINA DE PLATA, IMPRESIONES CROMOGÉNICAS E IMPRESIONES DE INYECCIÓN DE TINTA

From a high-angle view overlooking a segment of the river in proximity to its bank—and so perched on firm ground as to avoid slipping, on a boulder maybe, or a landing, at any rate in very close communication— the photographer obtains a surging choreography of the water below, a series of waves given to ripples and furrows and pockets of air, now suggesting tiny amulets or overlays, now veins or blemishes or scar tissue, along a sort of membrane, a primordial skin now retracting in pulses that coalesce, shudder, and let loose. The images register first as if in black and white, but they soon surrender perceptible orbits of slate, foam, fossil gray, and olive-green shades suddenly insinuating, as from an aerial view, the wild ridges of an otherworldly geological map.

Water, dermis, land. This sequence of color photographs by the US artist Zoe Leonard, abstracted from the flow of the Rio Grande/Río Bravo, its meanders defining the Texas–Mexico borderlands, serves as a prelude to the capacious yearslong project Al río / To the River , an open work that, from 2016 to 2022, involved extensive travel and field work along the 1,200 mile stretch of the river from Ciudad Juárez and El Paso to the Gulf of Mexico by way of Boca Chica, beyond Brownsville. In the process, Leonard made an artwork comprising several hundred photographs, some in color—like the abstract river surfaces or another sequence of extreme close-ups, the florescent pink of the low-lying pitaya cactus— even as the overwhelming majority are black-and-white prints in various formats and configurations. In their totality, they register scenes and situations—geographic, technological, economic, cultural, sociopolitical— along the binational river habitats, as well as the grandeur of the landscape, touched and untouched by human art and industry, brimming with the everyday life of its inhabitants and of those in transit. In addition to museum and gallery exhibitions, essential to the meaning of the vast work that is Al río / To the River , is a book in two volumes: The first features Leonard’s more than 285 photographs variously sequenced across three hundred pages, a landscape, too, in elongated print format, but devoid of any captions or checklist. 1 The second is a volume of writings authored by a host of collaborators including the environmental historian C. J. Alvarez, the journalist Cecilia Ballí, the art historians Darby English, Esther Gabara,

Desde un ángulo de visión elevado que domina un tramo del río cercano a su orilla —y tan encaramada sobre terreno firme para evitar resbalones, tal vez sobre una roca o un pequeño rellano, en todo caso en comunicación muy estrecha— la fotógrafa capta una coreografía impetuosa del agua que fluye abajo, una serie de olas que se disuelven en ondas, surcos y bolsas de aire, insinuando ahora diminutos amuletos o superposiciones, ahora venas, marcas o tejido cicatricial, sobre una especie de membrana, una piel primordial que se contrae en pulsos que se fusionan, se estremecen y se sueltan. Las imágenes se manifiestan al principio como si fueran en blanco y negro, pero pronto revelan órbitas perceptibles de pizarra, espuma, gris fósil y tonalidades verde oliva que de pronto insinúan, como desde una vista aérea, los pliegues salvajes de un mapa geológico de otro mundo.

Agua, dermis, tierra. Esta secuencia de fotografías en color de la artista estadounidense Zoe Leonard, abstraídas del flujo del Río Grande/Río Bravo, cuyos meandros definen las tierras fronterizas entre Texas y México, funciona como un preludio al amplio proyecto de años titulado Al río / To the River , una obra abierta que, entre 2016 y 2022, implicó extensos viajes y trabajo de campo a lo largo de los 1.931 kilómetros del río, desde Ciudad Juárez y El Paso hasta el Golfo de México mediante Boca Chica, más allá de Brownsville. En ese proceso, Leonard creó una obra compuesta por varios cientos de fotografías, algunas en color —como las superficies abstractas del río o una secuencia de primeros planos extremos del rosa fluorescente del cactus pitaya que crece a ras del suelo— aunque la gran mayoría son impresiones en blanco y negro en diversos formatos y configuraciones. En su conjunto, estas imágenes registran escenas y situaciones —geográficas, tecnológicas, económicas, culturales y sociopolíticas— a lo largo de los hábitats binacionales del río, así como la majestuosidad del paisaje, tocado y no tocado por la industria y el arte humanos, rebosante de la vida cotidiana de sus habitantes y de quienes están en tránsito. Además de las exposiciones en museos y galerías, parte esencial del significado de esta vasta obra que es Al río / To the River es un libro en dos volúmenes: el primero presenta más de 285 fotografías de Leonard, dispuestas en distintas secuencias a lo largo de trescientas páginas, un paisaje también en formato impreso alargado, pero sin pies de foto ni lista de obras. 1 El segundo volumen reúne textos de una serie de colaboradores, entre ellos el historiador ambiental C. J. Álvarez, la periodista Cecilia Ballí, los historiadores del arte

and Josh T Franco, and the poets Dolores Dorantes and Natalie Diaz, to name only a handful of the more than twenty-five collaborators.2 The writers and scholars were invited to imagine their contributions in diagonal relation to Leonard’s photographic work. The “two-volume structure of Al río / To the River was conceived,” writes its editor, Tim Johnson, “as a method as well as a structure, implicitly inviting conversation and comparison, allowing for different points of view to exist alongside and in relation to each other.”3

Encounter, interface, recordkeeping. These principles have long been at the center of Leonard’s elective affinities and practice. At the onset of a previous work, the large-scale decade-long undertaking Analogue , the artist related how she had begun taking pictures of storefronts in the neighborhoods of her New York childhood and adolescence where she lived first along the “edges of Harlem” and later “at sixteen, in 1977” on the Lower East Side. From 1998 to 2009, Leonard made over fifteen thousand photographs into a grid-based sequence of 412 photographs creating a vast record of store facades—“the bodegas, the butcher, the linoleum store”—or the display of objects for sale in public space pertaining to residual small-scale economies, both at home and abroad in her travels. In an inspired account of this series, and of Leonard’s corpus in terms of photographic practice today, the art historian George Baker expands on the meanings of the film medium within a then-nascent digital ecosystem, and on the wager of Leonard’s commitment to the analogical: an intensified identification with the camera-generated account and filmic recordkeeping to which the artist laid claim in the late 1990s, a “specific moment in history—the end of the mechanical age, the beginning of the digital era.”4 For Baker, Leonard’s determination to re-enchant the analog image confirmed a technological “lateness” that in turn inaugurated an affective and corporeal “openness” to the world. Baker writes of this photography understood, in light of the Analogue series, “as inherently relational— affective and loving—its operations not just the indexical fixative of the double or the trace, but the unending (desiring) quest for similarity, comparison, connection, and analogy.” That is, Baker aligns “openness” in a system that relates reception to displacement, to endlessly mutable forms, to

Darby English, Esther Gabara y Josh T Franco, y las poetas Dolores Dorantes y Natalie Diaz, por nombrar solo a algunos de los más de veinticinco colaboradores.2 A estos escritores y académicos se les invitó a imaginar sus contribuciones en una relación diagonal con la obra fotográfica de Leonard. “La estructura en dos volúmenes de Al río / To the River fue concebida”, escribe su editor Tim Johnson, “tanto como un método como una estructura, invitando implícitamente al diálogo y la comparación, permitiendo que distintos puntos de vista existan uno al lado del otro y en relación mutua.” 3 Encuentro, interfaz, registro. Estos principios han estado desde hace tiempo en el centro de las afinidades electivas y la práctica artística de Leonard. Al comienzo de una obra anterior, la ambiciosa empresa de una década titulada Analogue [Analógico], la artista relató cómo había comenzado a tomar fotografías de escaparates en los vecindarios de su infancia y adolescencia en Nueva York, donde vivió primero en las “afueras de Harlem” y más tarde “a los dieciséis, en 1977”, en el Lower East Side. De 1998 a 2009, Leonard tomó más de quince mil fotografías e hizo en una secuencia de 412 imágenes dispuestas en cuadrícula: un extenso registro de fachadas de tiendas —“las bodegas, la carnicería, la tienda de linóleo”— y de objetos expuestos para la venta en el espacio público, pertenecientes a economías residuales de pequeña escala, tanto locales como extranjeras durante sus viajes. En una interpretación inspirada de esta serie, y del corpus de Leonard en relación con la práctica fotográfica contemporánea, el historiador del arte George Baker profundiza en los significados del medio fílmico dentro de un ecosistema digital entonces naciente, así como en la apuesta que supone el compromiso de Leonard con lo analógico: una identificación intensificada con el relato generado por la cámara y el registro fílmico que la artista reclamó como suyo a fines de los años noventa, un “momento específico en la historia: el fin de la era mecánica, el inicio de la era digital.” 4 Para Baker, la determinación de Leonard de devolver la magia a la imagen analógica confirma una “tardanza” tecnológica que, a su vez, inaugura una “apertura” afectiva y corporal hacia el mundo. Baker escribe sobre esta fotografía entendida, a la luz de la serie Analogue , “como inherentemente relacional —afectiva y amorosa—, sus operaciones no son solo el fijador indiciario del doble o la huella, sino la búsqueda (deseante) sin fin de la similitud, la comparación, la conexión y la analogía”. Es decir, Baker vincula esta “apertura” a un sistema que relaciona la recepción con el desplazamiento, con formas infinitamente mutables, con la interconexión,

connectedness, enclosure, and layers of reflection in the interplay of likeness and desire. “To receive, for Leonard, is to want to bring the new object close, almost to draw it into the void of one’s camera—to incorporate the image, again, like one internalizes a lost object. And in the photographs, we feel this drive everywhere enacted: physically, corporeally, psychically,” he stated.5

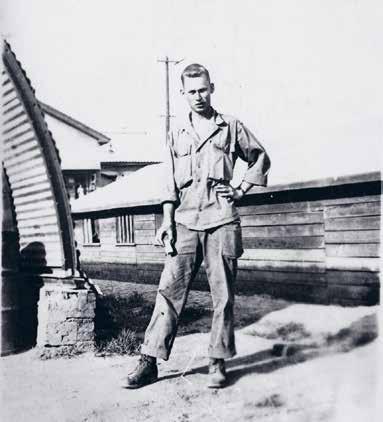

In the first of three galleries of the presentation of Al río / To the River at the Chinati Foundation, Leonard appeals to the sheer physical attributes of the river, in the grammar of minimalist repetition. In a horizon line traversing the overbright gallery space, twenty-four photographs align the four walls in sequences of eight and four—the hours of a day. In one riversurface image, the eddies appear to amalgamate even as they recoil in the same pull and plunge forming a row of clusters held together as though the current depended on such forms of cooperation. In the variable flows, in the turbid stress and spinning release, the literal and iterative registers of succession so merge and transfigure in patterns commensurate with a viewer’s qualities of attention as to collapse the division between the particular—a detail—and its totality. In this regard, Al río / To the River, designed to be viewed in three

el confinamiento y las capas de reflexión en el juego entre semejanza y deseo. “Recibir, para Leonard, es querer acercar el nuevo objeto, casi atraerlo hacia el vacío de su cámara: incorporar la imagen, de nuevo, como se internaliza un objeto perdido. Y en las fotografías sentimos este impulso activarse en todas partes: física, corporal y psíquicamente”, escribió. 5 En la primera de tres galerías que conforman la presentación de Al río / To the River en la Fundación Chinati, Leonard apela a los atributos físicos del río, empleando la gramática de la repetición minimalista. A lo largo de una línea del horizonte que atraviesa el espacio sobreiluminado de la galería, veinticuatro fotografías se alinean en las cuatro paredes en secuencias de ocho y cuatro: las horas de un día. En una de las imágenes de la superficie del río, los remolinos parecen amalgamarse incluso cuando retroceden en el mismo impulso de atracción y hundimiento, formando una hilera de agrupaciones mantenidas unidas como si la corriente dependiera de esa forma de cooperación. En los flujos variables, en la tensión turbia y la liberación giratoria, los registros literales y repetitivos de la sucesión se funden y transfiguran de tal modo en patrones acordes con las cualidades de atención del espectador, al punto de colapsar la división entre lo particular —un detalle— y su totalidad. En este sentido, Al río / To the River , concebido para ser contemplado en tres

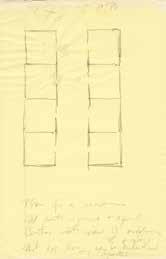

different buildings among those comprising the grounds of the Chinati Foundation—formerly Camp Albert, a US military base established in 1911 to patrol the US–Mexico border, later Camp Marfa, and eventually Fort D. A. Russell—further reverberates with past and present meanings imbuing its location of display in direct proximity to the US Customs and Border Protection offices and Big Bend Sector headquarters adjoining the Chinati grounds. In critical relationship as well to neighboring works by Donald Judd, John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin, and Robert Irwin, among others, Leonard’s photographic narratives mark the dividing line between the safeguarded realm of artworld display and speculation, even in the expanded field of Marfa, and the material, geopolitical, and environmental contradictions that specify the Texas–Mexico borderlands.

In the second building, Leonard’s images follow a discontinuous succession of places where the Rio Grande/ Río Bravo is made to serve as international boundary between the United States and Mexico, at the American Diversion Dam just above the US–Mexico border in El Paso. The series makes visible a staggered itinerary along the river’s course, through waterways and wetlands leading to the Rio Grande Valley and the Gulf

edificios distintos dentro del terreno que ocupa la Fundación Chinati —anteriormente Campamento Albert, una base militar estadounidense establecida en 1911 para patrullar la frontera entre EE. UU. y México, más tarde Campamento Marfa, y finalmente Fuerte D. A. Russell— resuena también con los significados del pasado y del presente que impregnan el lugar de exhibición, en proximidad directa con las oficinas de Aduanas y Protección Fronteriza de EE. UU. y la sede del Sector Big Bend, adyacentes al recinto de Chinati. En relación crítica con las obras vecinas de Donald Judd, John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin y Robert Irwin, entre otros, las narrativas fotográficas de Leonard marcan la línea divisoria entre el ámbito resguardado de la exhibición y especulación del mundo del arte —aun dentro del campo expandido de Marfa— y las contradicciones materiales, geopolíticas y medioambientales que caracterizan la región fronteriza entre Texas y México. En el segundo edificio, las imágenes de Leonard siguen una sucesión discontinua de lugares donde el Río Grande/Río Bravo sirve como frontera internacional entre Estados Unidos y México, en la presa American Diversion justo al norte de la línea fronteriza en El Paso. La serie visibiliza un itinerario fragmentado a lo largo del cauce del río, atravesando canales y humedales que conducen al Valle del Río Grande y al Golfo de México. Entre los lugares fotografiados se encuentran puntos

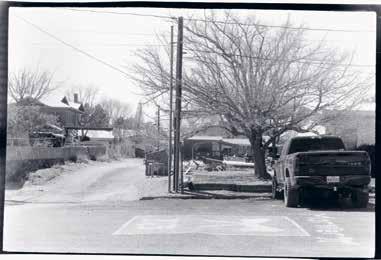

of Mexico. Among the places photographed are points around the twenty-eight international bridges and border crossings, which include “two dams, one hand-drawn ferry, and twenty-five other crossings that allow commercial, vehicular and pedestrian traffic.”6 The photographs register as well the intersecting urban and industrial sprawl—namely “the border construction during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries” that the environmental historian C. J. Alvarez classifies as “compensatory building … designed to mitigate the unintended consequences of previous building projects.”7 In a lens perspective that has no particular purchase on a heightened sense of eventfulness, nor on a relation of detachment to the “man-altered landscape” specified by exponents of the New Topographics, for instance, so many of the images in Al río / To the River render the middle distance from a standpoint, a certainty “in person,” so to speak.8 In this sense, active viewership resembles a form of embodied hesitation at the intervals—now unambiguous, now indiscernible—that open up between the built world, the natural landscape, and social processes along the border zone.

Steel metal grates of the border wall cut through slopes of the high desert

en torno a los veintiocho puentes y cruces fronterizos internacionales, que incluyen “dos presas, un ferry manual y otros veinticinco cruces que permiten el tránsito comercial, vehicular y peatonal.” 6 Las fotografías registran también la expansión urbana e industrial entrecruzada, particularmente “la construcción fronteriza durante los siglos XX y XXI” que el historiador ambiental C. J. Álvarez clasifica como una “arquitectura compensatoria… diseñada para mitigar las consecuencias no previstas de proyectos constructivos anteriores.” 7 Desde una perspectiva fotográfica que no pretende resaltar un dramatismo puntual, ni tampoco establecer una distancia crítica frente al “paisaje modificado por el ser humano” —como lo proponían, por ejemplo, los exponentes de la Nueva Topografía— muchas de las imágenes de Al río / To the River representan la media distancia desde un punto de vista directo, una certeza “en persona”, por así decirlo. 8 En este sentido, la mirada activa se asemeja a una forma de vacilación encarnada en los intervalos — ya inequívocos, ya imperceptibles— que se abren entre el mundo construido, el paisaje natural y los procesos sociales a lo largo de la zona fronteriza. Rejas de metal del muro fronterizo cortan las pendientes del terreno del alto desierto cerca de El Paso, donde un todoterreno y un grupo de visitantes, ensombrecidos por el terreno y la construcción, se aproximan al Monumento de Límite Número

terrain near El Paso where an SUV and a group of visitors, overshadowed by the land and construction, approach the Boundary Monument One, “erected in 1855 by the EmorySalazar surveyors.” 9 The marker, now managed by the International Boundary and Water Commission, bears a plaque that specifies the “Boundary of the United States of America,” while a neighboring image captures at close range a section of zigzagging wall restricting access to the monument, with a banner on display from the privately funded organization “We Build the Wall.”

Present viewing confers on images realities unavailable to the time of their making that are undeniable now, such as a press release of April 26, 2023, from the offices of Damian Williams, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, announcing the sentences issued to Brian Kolfage and Andrew Badolato by United States District Judge Analisa Torres “for their respective roles in carrying out a scheme to defraud hundreds of thousands of donors in connection with an online crowdfunding campaign known as ‘We Build The Wall’ by soliciting donations using false statements and then stealing the resulting donations.”10

These images contrast with another set of photographs from the side of

Uno, “erigido en 1855 por los topógrafos Emory-Salazar”. 9 El marcador, ahora gestionado por la Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, ostenta una placa que señala el “Límite de los Estados Unidos de América”, mientras que una imagen cercana captura un tramo del muro en zigzag que restringe el acceso al monumento, junto a una pancarta de la organización privada “We Build the Wall” [Construimos el muro]. La contemplación actual otorga a las imágenes realidades que no estaban disponibles en el momento en que fueron tomadas y que hoy resultan innegables, como el comunicado de prensa del 26 de abril de 2023 emitido por la oficina de Damian Williams, Fiscal de los Estados Unidos para el Distrito Sur de Nueva York, anunciando las condenas dictadas por la jueza de distrito Analisa Torres contra Brian Kolfage y Andrew Badolato “por su participación en un esquema para defraudar a cientos de miles de donantes en relación con una campaña de micromecenazgo en línea conocida como ‘We Build The Wall’ mediante la solicitud de donaciones a partir de declaraciones falsas y el robo de los fondos recaudados”.10

Estas imágenes contrastan con otra serie de fotografías tomadas desde el lado de Ciudad Juárez, una línea del horizonte que une el Monte Cristo Rey en la lejanía con una red de infraestructuras —secciones de la presa estadounidense rodeadas de almacenes industriales,

Ciudad Juárez, a horizon line that joins Mount Cristo Rey in the far background to the network of engineering—sections of the American Dam surrounded by industrial warehouses, bridges, and chain-link fences—the river below providing a patch of public beach behind Casa de Adobe, a heritage site and museum devoted to material culture and photography of the Mexican Revolution. Throughout the series, compositions along the riverbanks reveal material disparities between one side and the other, as well as visual collisions between protected natural environs, commercial works of civil engineering, the infrastructure of trade, subsistence farming, and large-scale agriculture, along with the ever-pervasive manifestations of border security and the surveillance apparatus. Covering one gallery wall is a grid comprised of thirty-four photographs that track a helicopter circling the sky above the crest of several river-adjacent trees, a storyboard whose last two absent frames serve to suggest those who go missing and perish in a terrain hostile to human crossing, possibly contesting such commonplace occurrences in the borderland field of vision, in that the implied cinematic action is deprived of its structural culmination, the grid incomplete and truncated. On a riverbank road near McAllen,

puentes y vallas de alambre— mientras que el río debajo ofrece un pequeño tramo de playa pública detrás de la Casa de Adobe, un museo patrimonial dedicado a la cultura material y la fotografía de la Revolución Mexicana. A lo largo de la serie, las composiciones a orillas del río revelan las disparidades materiales entre un lado y el otro, así como las colisiones visuales entre entornos naturales protegidos, obras de ingeniería civil, la infraestructura del comercio, la agricultura de subsistencia y a gran escala, junto a las omnipresentes manifestaciones de la seguridad fronteriza y el aparato de vigilancia. En una pared de la galería se despliega una cuadrícula compuesta por treinta y cuatro fotografías que siguen a un helicóptero que sobrevuela las copas de unos árboles a la vera del río, una suerte de guión gráfico cuyos dos últimos fotogramas ausentes sugieren a quienes desaparecen y perecen en un terreno hostil para el cruce humano, posiblemente impugnando la habitualidad con la que se perciben estos episodios en el campo visual fronterizo, ya que la acción cinematográfica queda privada de su culminación estructural, la cuadrícula incompleta y truncada. En un camino ribereño cercano a McAllen, Texas, un escuadrón de vehículos de la Patrulla Fronteriza ha rodeado una furgoneta blanca, y la secuencia de imágenes representa la detención y traslado del grupo que ha sido acorralado

Texas, a squad of Border Patrol vehicles has surrounded a white van, the cluster of images depicting the detention and removal of the huddled and apprehended, a duration of migrant time in view of a police tower just beyond a nearby railroad-track crossing. The ethnographer Ruben Andersson has described how speed and stasis together compose the time of migration, the economically engineered durations that link “cross-border movement and waiting.” Technologies of control, working steadily to outpace the action of migrants and asylum seekers, ever amplify the velocity of “real-time intelligence,” for which lens-based surveillance systems serve as legitimating reason for the escalation of patrolling and militarization along the US–Mexico divide. States that fund border agencies and outsource defense companies to run detention centers produce something like “state time” palpably distinct from “subjective time.” In this scenario, a “quest for speed is intimately tied up with the concept of risk” and the temporal modalities of risk, in turn, define “time-space compression” that further motivates “large investments in new information sharing systems,” making border zones an “information channel, communicating up, sideways, and down in a chain of

y aprehendido, una duración del tiempo migrante a la vista de una torre de vigilancia policial más allá de un cruce ferroviario cercano. El etnógrafo Ruben Andersson ha descrito cómo la velocidad y la inmovilidad componen juntas el tiempo de la migración, las duraciones económicamente diseñadas que entrelazan “el movimiento y la espera transfronterizos”. Las tecnologías de control, que actúan sin cesar para superar en ritmo a los migrantes y solicitantes de asilo, amplifican sin descanso la velocidad de la “inteligencia en tiempo real”, para la cual los sistemas de vigilancia basados en imágenes funcionan como justificación para la expansión del patrullaje y la militarización a lo largo de la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos. Los estados que financian a las agencias fronterizas y subcontratan empresas de defensa para gestionar los centros de detención producen algo parecido a un “tiempo estatal” claramente distinto del “tiempo subjetivo”. En este escenario, la “búsqueda de velocidad está íntimamente ligada al concepto de riesgo” y las modalidades temporales del riesgo, a su vez, definen una “compresión tiempo-espacio” que motiva aún más “grandes inversiones en nuevos sistemas de intercambio de información”, convirtiendo a las zonas fronterizas en un “canal informativo que comunica hacia arriba, lateralmente y hacia abajo mediante una cadena de señales”. En el régimen espacio-temporal

signals.” In the time-space regime of globalization, “the possibilities of anticipation, interception, and deferral opened up by compression and speed have led to precisely the opposite reality for those who are targeted: a world of slowness and stasis,” Andersson wrote.11

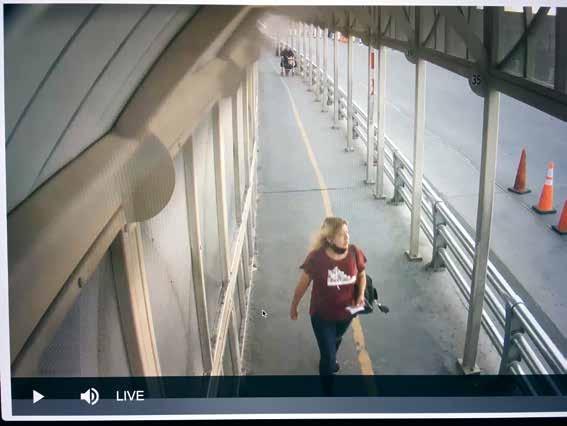

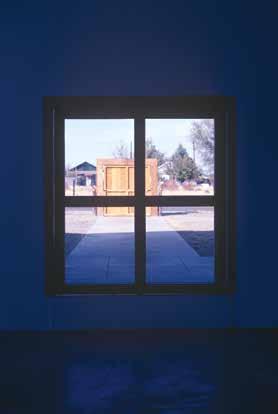

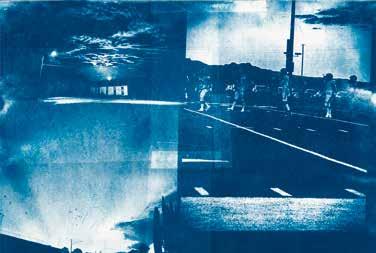

As a technology of “lateness,” in Baker’s definition, and her camera no less extricable from the image system and its state-convenient information channels, Leonard detains the relentless flow of real-time streaming video to offer for viewing ink-jet prints of photographs that capture her laptop computer screen, its search window open to a live border-cam feed whose surveillance lens is aimed at pedestrians crossing from Juárez to El Paso on the Paso del Norte International Bridge. Whether alone or in group configurations, some of the subjects wear surgical masks, in a time-stamp of the coronavirus pandemic, depicted beside the adjacent lane for vehicles, the visual field betraying the warp of the surveillance camera, and a degree of pixelation, with the LIVE legend and streaming bar on the lower end of the pictured screen. Displayed in the third exhibition building, these prints are encased in a row of wooden vitrines that alter the viewing experience from that of the horizon line or grid

de la globalización, “las posibilidades de anticipación, intercepción y diferimiento que abre la compresión y la velocidad han conducido a la realidad precisamente opuesta para quienes son blanco de estas medidas: un mundo de lentitud y estancamiento”, escribió Andersson. 11 Como una tecnología de “tardanza”, según la definición de Baker, y con su cámara no menos inextricable del sistema de imágenes y de sus canales informativos convenientes para el Estado, Leonard detiene el flujo implacable del video en tiempo real para ofrecer a la vista impresiones de inyección de tinta de fotografías que capturan la pantalla de su laptop, con la ventana de búsqueda abierta a la transmisión en vivo de una cámara fronteriza cuya lente de vigilancia apunta a los peatones que cruzan de Juárez a El Paso por el Puente Internacional Paso del Norte. Ya sea solos o en grupos, algunos de los sujetos llevan mascarillas quirúrgicas, en una marca temporal de la pandemia de coronavirus, retratados junto al carril adyacente para vehículos, el campo visual traicionando la distorsión de la cámara de vigilancia y cierto grado de pixelación, junto con la leyenda LIVE [en vivo] y la barra de transmisión en la parte inferior de la pantalla fotografiada. Exhibidas en el tercer edificio de la exposición, estas impresiones se muestran en una fila de vitrinas de madera que alteran la experiencia de visualización de la línea del horizonte o la cuadrícula a

to a form of display associated with specimen observation, “such as the work’s being like an object or being specific,” in the language Donald Judd used to describe art-world specific objects.12 In a critical collision for the viewer, several of Judd’s 15 untitled works in concrete (1980–84) can be discerned in the faraway distance through the open windows of the Chinati exhibition space. More than the other buildings on Chinati’s grounds, all of which are the remnants of a United States military base, this weathered building, without windows and doors, serves as a frame that blurs residual histories and material actualities—a lateness in the sense George Baker attributes to Leonard’s practice, now amplified across the political geography of technological excess in Homeland Security surveillance techniques that join ground sensors, drones, dirigibles, and radar to fixed and mobile video systems.

To cut a pathway, a through line across the totality of images in Al río / To the River , the complexity of cultural processes and interdependence they compel, is to be overcome by the consciousness of an effort that seeks the exhaustive account, the drive to identify and the inclination to know, the desire to make all that is calculable a question

una forma de presentación asociada a la observación de especímenes, “como que la obra sea como un objeto o que sea específica,” en palabras que Donald Judd usó para describir los objetos específicos del mundo del arte. 12 En una colisión crítica para el espectador, varias de las 15 obras sin título en hormigón (1980–84) de Judd pueden distinguirse en la lejanía a través de las ventanas abiertas del espacio expositivo de Chinati. Más que los demás edificios en los terrenos de Chinati, los cuales son los remanentes de una base militar de Estados Unidos, este edificio desgastado, sin ventanas y puertas, funciona como un marco que difumina historias residuales y materialidades reales: una tardanza en el sentido que George Baker atribuye a la práctica artística de Leonard, ahora amplificada a través de la geografía política del exceso tecnológico en técnicas de vigilancia del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional que unen sensores terrestres, drones, dirigibles y radares a sistemas fijos y móviles de video.

Abrirse paso a través del total de imágenes en Al río / To the River —la complejidad de los procesos culturales y la interdependencia que exigen—, es verse sobrecogido por la conciencia de un esfuerzo que persigue el registro exhaustivo, el impulso por identificar y la inclinación a saber, el deseo de convertir todo aquello calculable en un asunto de descripciones. “Me doy cuenta de que soy

of description. “I find myself unable to settle on a single description or subject position,” writes Leonard to the Chicano art historian Josh T Franco, “the river is both singular and plural.”13

To so concede to the obligatory impasse, to Al río / To the River ’s epistemological challenge that subsists in the intervals, is to return to the opening frames on the riverbank contractions, ripples, and the promise of ceaselessly flowing water. And it is a turn to recent news by Rachel Lee of the Wilson Center relating the conditions of extreme drought and overextraction that “have also caused tension for those dependent on the Rio Grande at the border, as competing water users struggle to meet their own needs” and compliance with a 1944 water-sharing treaty between the United States and Mexico that “governs water allocation from the Rio Grande and Colorado River.” 14

According to a 2024 report, between 2017 and 2023, 1,107 human lives have perished by drowning in the Rio Grande, a “graveyard for migrants, many of whose deaths are never recorded by authorities on either side of the border.”15

And as of April–May 2025, militarization in the region has again reached newer unthinkable levels of escalation. In rapid succession the Department of the Interior “transferred 170 miles of the Roosevelt Reservation—a 60-foot-wide federally owned strip of

incapaz de conformarme con una sola descripción o punto de vista”, escribe Leonard al historiador del arte chicano Josh T Franco, “el río es a la vez singular y plural.” 13

Ceder ante el impasse obligatorio, al desafío epistemológico que subsiste en los intervalos de Al río / To the River , es regresar a los fotogramas iniciales en la ribera del río: las contracciones, las ondulaciones y la promesa del agua que fluye sin cesar. Y es también volverse hacia las noticias recientes de Rachel Lee, del Wilson Center, que describen las condiciones de sequía extrema y sobreextracción que “también han causado tensiones para quienes dependen del Río Grande en la frontera, ya que los usuarios en competencia luchan por satisfacer sus propias necesidades” y por el cumplimiento de un tratado de 1944 entre Estados Unidos y México que “regula la asignación del agua del Río Grande y el Río Colorado”. 14

Según un informe de 2024, entre 2017 y 2023, 1.107 vidas humanas perecieron ahogadas en el Río Grande, un “cementerio para migrantes, muchas de cuyas muertes nunca son registradas por las autoridades en ninguno de los dos lados de la frontera”. 15

Y desde abril–mayo de 2025, la militarización en la región ha vuelto a alcanzar niveles de escalada impensables. En rápida sucesión, el Departamento del Interior “traspasó 170 millas [274 kilómetros] de la Reserva Roosevelt —una franja de tierra de propiedad federal de 60 pies [18 metros] de ancho a lo largo de la frontera entre Nuevo México y México”—,

land along the border between New Mexico and Mexico” while “the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) transferred land that “begins at the American Dam in El Paso and extends 63 miles southeast to Fort Hancock, Texas,” both of which the government has christened “National Defense Areas.” Border journalist and author Melissa del Bosque writes that all persons “detained in these militarized zones”—be they migrants, activists, or artists—face “federal trespassing charges for being on a military installation.”16

In Al río / To the River , single photographs and sequences so escalate as to match the immensity of the river surround, its industrial and natural environments, the physical markers of sprawling financial networks and systems of militarization that turn the technologies of surveillance, law enforcement, custody, and detention into joint political and economic orders that profit from global displacement, from laboring bodies and migratory lives, next to everyday acts of tenacity within a structure inclined to dehumanize. In the wave contractions, surface and depth conflate as provisional extensions of the material and human processes for which the eddies are a correlative—the lifeways that double as effect and cause of the river environs, whether on display or hidden from view.

mientras que “la International Boundary and Water Commission [Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas] (IBWC) cedió terrenos que ‘comienzan en la presa American Dam en El Paso y se extienden 63 millas [101 kilómetros] al sureste hasta Fort Hancock, Texas’”, espacios que el gobierno ha rebautizado como “Áreas de Defensa Nacional”. La periodista fronteriza y autora Melissa del Bosque escribe que todas las personas “detenidas en estas zonas militarizadas” —sean migrantes, activistas o artistas— se enfrentan a “cargos federales por invasión de propiedad privada de una instalación militar”. 16

En Al río / To the River , tanto las fotografías individuales como las secuencias se intensifican hasta igualar la inmensidad del entorno fluvial, sus entornos industriales y naturales, los marcadores físicos de redes financieras expansivas y sistemas de militarización que convierten las tecnologías de vigilancia, cumplimiento de la ley, custodia y detención en órdenes políticos y económicos que se benefician del desplazamiento global, de los cuerpos que trabajan y las vidas migrantes, junto a actos cotidianos de tenacidad dentro de una estructura que tiende a deshumanizar. En las contracciones de las olas, la superficie y la profundidad se entrelazan como extensiones provisionales de los procesos materiales y humanos para los cuales los remolinos son un correlato: los modos de vida que funcionan como efecto y causa de los entornos del río, ya sean visibles o permanezcan ocultos a la vista.

Roberto Tejada es autor de obras sobre historia de los medios y del arte, incluyendo National Camera: Photography and Mexico’s Image Environment [Cámara nacional: la fotografía y el entorno de la imagen de México] (2009) y Celia Álvarez Muñoz (2009), así como de una colección de ensayos sobre arte y cultura latinx titulada Still Nowhere in an Empty Vastness [Todavía en ninguna parte en un vacío inmenso] (2019). Entre sus libros de poesía se encuentran Carbonate of Copper [Carbonato de cobre] (2025), Why the Assembly Disbanded [Por qué se disolvió la asamblea] (2020), Exposition Park [Parque de exposiciones] (2010) y Mirrors for Gold [Espejos por oro] (2006). Fue galardonado con la Beca de la Fundación Conmemorativa John Simon Guggenheim en Poesía (2021) y actualmente es Profesor Distinguido Hugh Roy y Lillie Cranz Cullen en la Universidad de Houston, donde enseña escritura creativa e historia del arte.

El apoyo para la obra de arte ha sido proporcionado por la Fundación Graham para Estudios Avanzados en Bellas Artes, la John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, la Galerie Gisela Capitain, en Colonia, y Hauser & Wirth, en Nueva York

Roberto Tejada is the author of media and art histories, including National Camera: Photography and Mexico’s Image Environment (2009) and Celia Alvarez Muñoz (2009), as well as the collected essays on Latinx art and culture, Still Nowhere in an Empty Vastness (2019). His poetry collections include Carbonate of Copper (2025), Why the Assembly Disbanded (2020), Exposition Park (2010), and Mirrors for Gold (2006). Awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in Poetry (2021), he is the Hugh Roy and Lillie Cranz Cullen Distinguished Professor at the University of Houston where he teaches creative writing and art history.

Support for the artwork has been given by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

1 The exhibition Zoe Leonard: Al río / To the River featured at the Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (2022) was organized in collaboration with the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris–Paris Musées (2022), curated by Suzanne Cotter and Christophe Gallois, and traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney (2023). Related gallery exhibitions have been presented at Hauser & Wirth, New York (excerpts from Al río / To the River, 2022), Capitain Petzel, Berlin (2022), and Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan (2023/2024); for the publication, see Zoe Leonard et al., Al río / To the River, ed. Tim Johnson (Hatje Cantz; Mudam Luxembourg; Musée d’Art Moderne GrandDuc Jean, 2022).

2 The full list of collaborators includes C. J. Alvarez, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Cecilia Ballí, Carolyn Boyd, Remijio “Primo” Carrasco, Alfredo Corchado, Yuri de la Rosa, Natalie Diaz, Dolores Dorantes, Darby English, Álvaro Enrigue, Catherine Facerias, Nadiah Rivera Fellah, Josh T Franco, Esther Gabara, Adolfo GuzmanLopez, Angela Kocherga, Land Arts of the American West, Elisabeth Lebovici, Aimé Iglesias Lukin, José Rabasa, Cameron Rowland, Inocencio Lugo Ruiz, Benjamin Alire Sáenz, Roberto Tejada, and Karla Cornejo Villavicencio.

3 Tim Johnson, “Editor’s Note,” in Al río / To the River, 16, 17.

4 Zoe Leonard, “Out of Time,” artist questionnaire by George Baker, October, no. 100 (Spring 2002): 89, 95.

5 George Baker, Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography (University of Chicago Press, 2023), 56, 57.

6 “Texas–Mexico Border Crossings,” Texas Department of Transportation, https://www. txdot.gov/projects/projects-studies/statewide/texas-mexico-border-crossings.html.

7 C. J. Alvarez, “A Brief History of the River,” in Al río / To the River, 25.

8 William Jenkins, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, exh. cat. (International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1975).

9 National Park Service, Chamizal National Memorial, https://www.nps.gov/places/boundary-monument-one.htm#:~:text=Boundary%20Monument%201%20 was%20erected%20on%20the%20international%20boundary%20to,Mexican%20 state%20of%20Chihuahua%20meet.

10 The press release also states that: “Damian Williams, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, announced that BRIAN KOLFAGE and

1 La exposición Zoe Leonard: Al río / To the River presentada en el Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (2022) fue organizada en colaboración con el Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris- Paris Musées (2022), comisariada por Suzanne Cotter y Christophe Gallois, y viajó a otros lugares como el Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney (2023). Se han presentado exposiciones relacionadas en galerías como Hauser & Wirth, Nueva York (extractos de Al río / To the River , 2022), Capitain Petzel, Berlín (2022), y Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milán (2023/2024); para la publicación, véase Zoe Leonard et al., Al río / To the River , ed., Tim Johnson (Hatje Cantz; Hauser & Wirth, Nueva York). Tim Johnson (Hatje Cantz; Mudam Luxembourg; Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, 2022).

2 La lista completa de colaboradores incluye a C. J. Álvarez, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Cecilia Ballí, Carolyn Boyd, Remijio “Primo” Carrasco, Alfredo Corchado, Yuri de la Rosa, Natalie Diaz, Dolores Dorantes, Darby English, Álvaro Enrigue, Catherine Facerias, Nadiah Rivera Fellah, Josh T Franco, Esther Gabara, Adolfo Guzman-Lopez, Angela Kocherga, Land Arts of the American West, Elisabeth Lebovici, Aimé Iglesias Lukin, José Rabasa, Cameron Rowland, Inocencio Lugo Ruiz, Benjamín Alire Sáenz, Roberto Tejada y Karla Cornejo Villavicencio.

3 Tim Johnson, “Editor’s Note” [Nota del editor] en Al r í o / To the River , p. 16, p. 17.

4 Zoe Leonard, “Out of Time” [Fuera de tiempo], cuestionario para artistas de George Baker, October , núm. 100 (primavera 2002): p. 89, p. 95.

5 George Baker, Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography [Tarde y añoranza: sobre el más allá de la fotografía] (University of Chicago Press, 2023), p. 56, p. 57.

6 “Texas–Mexico Border Crossings” [Pasos fronterizos entre Texas y México], Texas Department of Transportation, https:// www.txdot.gov/projects/projects-studies/ statewide/texas-mexico-border-crossings. html.

7 C. J. Álvarez, “A Brief History of the River” [Una breve historia del río] en Al r í o / To the River , p. 25.

8 William Jenkins, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape [Nueva topografía: fotografías de un paisaje alterado por el hombre], catálogo de la exposición (International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1975).

9 National Park Service, Chamizal National Memorial, https://www.nps.gov/places/ boundary-monument-one.htm#:~:text=Boundary%20Monument%201%20was%20 erected%20on%20the%20international%20 boundary%20to,Mexican%20state%20 of%20Chihuahua%20meet.

10 El comunicado de prensa también afirma que: “Damian Williams, Fiscal de los Estados Unidos para el Distrito Sur de Nueva York, anunció que BRIAN KOLFAGE y ANDREW BADOLATO fueron sentenciados hoy por la Juez de Distrito de los Estados Unidos Analisa Torres. KOLFAGE fue condenado a 51 meses de prisión, y BADOLATO fue condenado a 36 meses de prisión, por sus respectivos papeles”, Oficina del Fiscal de los Estados Unidos para el Distrito Sur de Nueva York, “Two Sentenced To Prison For ”We Build The Wall’ Online Fundraising Fraud Scheme” [Dos condenados a prisión por el fraude de la recaudación de fondos en línea “Construimos el muro”], comunicado de prensa, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/two-sentenced-prison-we-build-wallonline-fundraising-fraud-scheme.

11 Ruben Andersson, “Time and the Migrant Other: European Border Controls and the Temporal Economics of Illegality” [El tiempo y el otro inmigrante: los controles fronterizos europeos y la economía temporal de la ilegalidad], American Anthropologist 116, núm.

ANDREW BADOLATO were sentenced today by United States District Judge Analisa Torres. KOLFAGE was sentenced to 51 months in prison, and BADOLATO was sentenced to 36 months in prison, for their respective roles,” United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, “Two Sentenced To Prison For ‘We Build The Wall’ Online Fundraising Fraud Scheme,” press release, https://www.justice.gov/ usao-sdny/pr/two-sentenced-prison-webuild-wall-online-fundraising-fraud-scheme.

11 Ruben Andersson, “Time and the Migrant Other: European Border Controls and the Temporal Economics of Illegality,” American Anthropologist 116, no. 4 (December 2014): 795–809; see also Ruben Andersson, Illegality, Inc: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe (University of California Press, 2014).

12 Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” Arts Yearbook 8 (1965): 74–82. Reprinted in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959–1975 (The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 2005), 181–89.

13 Zoe Leonard, email to Josh T Franco, in Josh T Franco, “Bridgeless (Notes for Zoe and Tim),” Al río / To the River, fn. 15, 133.

14 Lee continues: “This situation, however, is arguably more contentious. Since 1992, Mexico’s water deliveries to the US have been irregular. The current five-year cycle that ends in October 2025 is no different, as the US has only received a little over a year’s worth of water thus far. Texas’ agricultural sector has faced significant setbacks from deficient deliveries. Due to the lack of water, the state’s last sugar mill shut down last year. Its citrus industry is also under threat. As a result, Texan politicians have repeatedly threatened to impose sanctions on Mexico. The US State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs also stated that it would cut Colorado River water deliveries to Tijuana. The recent $280 million grant agreement dedicated to providing economic relief to Rio Grande Valley farmers has only mitigated some tension. To make up for past shortfalls, Mexico has used its own storage from the Amistad and Falcon Reservoirs—two major water sources located and shared at the border that are experiencing record lows. Such last-minute decisions have provoked tension in downstream districts, where Mexican residents and farmers are already facing their own domestic water issues,” Rachel Lee, “Water Security at the US–Mexico Border,” April 1, 2025, Wilson Center, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/water-security-us-mexico-border-part-1-background#:~:text=Water%20security%20has%20been%20 a,River%20and%20the%20Rio%20Grande; “US Rejects Mexico’s Request for Water as Trump Opens New Battle Front,” The Guardian, March 20, 2025, https://www. theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/20/ tijuana-mexico-water-trump

15 Miriam Ramírez, “Río Bravo: El caudal de los mil migrantes muertos,” El Universal, December 8, 2024, https://interactivos.eluniversal.com.mx/2024/migrar-unico-camino/rio-bravo.html; Melissa del Bosque et al., “Drownings and Deterrence in the Rio Grande,” Lighthouse Reports, copublished with The Washington Post and El Universal, December 8, 2024, https://www.lighthousereports.com/investigation/drowningsand-deterrence-in-the-rio-grande/#:~:text=Our%20data%20on%20drownings%20 reveals,increasingly%20dying%20in%20 the%20river.

16 Melissa del Bosque, “A New Phase in Border Militarization: Trump’s ‘National Defense Areas,’” The Border Chronicle, May 8, 2025, https://www.theborderchronicle. com/p/a-new-phase-in-border-militarization.

4 (diciembre de 2014): pp. 795–809; véase también Ruben Andersson, Illegality, Inc: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe [Ilegalidad, Inc: migración clandestina y el negocio de crear fronteras en Europa] (University of California Press, 2014).

12 Donald Judd, “Specific Objects” [Objetos específicos], Arts Yearbook 8 (1965): pp. 74–82. Reimpreso en Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959 –1975 [Donald Judd: los escritos completos 1959 –1975 ], (The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 2005), pp. 181–89.

13 Zoe Leonard, correo electrónico a Josh T Franco, en Josh T Franco, “Bridgeless (Notes for Zoe and Tim)” [Sin puentes – notas para Zoe y Tim], Al r í o / To the River , nota a pie de página 15, p. 133.

14 Lee continúa: “Esta situación, sin embargo, es posiblemente más conflictiva. Desde 1992, las entregas de agua de México a Estados Unidos han sido irregulares. El actual ciclo quinquenal, que finaliza en octubre de 2025, no es la excepción, ya que Estados Unidos solo ha recibido poco más del equivalente a un año de agua hasta ahora. El sector agrícola de Texas se ha enfrentado a importantes contratiempos debido a las entregas deficientes. Por la falta de agua, el último ingenio azucarero del estado cerró el año pasado. Su industria citrícola también está en peligro. Como resultado, los políticos texanos han amenazado repetidamente con imponer sanciones a México. Asimismo, la Oficina para Asuntos del Hemisferio Occidental del Departamento de Estado de Estados Unidos ha declarado que reducirá las entregas del Río Colorado a Tijuana. El reciente acuerdo de subvención por 280 millones de dólares destinado a proporcionar alivio económico a los agricultores del Valle del Río Grande solo ha aliviado parte de la tensión. Para compensar los déficits anteriores, México ha recurrido a sus propias reservas en las presas Amistad y Falcón —dos fuentes importantes de agua ubicadas en la frontera y que experimentan niveles históricamente bajos—. Estas decisiones de último momento han provocado tensiones en los distritos aguas abajo, donde los residentes y agricultores mexicanos ya se enfrentan a sus propios problemas hídricos nacionales”, Rachel Lee, “Water Security at the US–Mexico Border” [Seguridad del agua en la frontera entre EE.UU. y México], 1 de abril de 2025, Wilson Center, https://www. wilsoncenter.org/ article/ water-security-us-mexico- border-part1ackground#:~:text=Water%20security%20 has%20been%20a,River%20and%20the%20 Rio%20Grande; “US Rejects Mexico’s Request for Water as Trump Opens New Battle Front,” The Guardian , March 20, 2025, https:// www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/ mar/20/tijuana-mexico-water-trump

15 Miriam Ramírez, “Río Bravo: El caudal de los mil migrantes muertos,” El Universal , el 8 de diciembre de 2024, https://interactivos. eluniversal.com.mx/2024/migrar-unico-camino/rio-bravo.html; Melissa del Bosque et al., “Drownings and Deterrence in the Rio Grande” [Ahogamientos y disuasión en el Río Grande], Lighthouse Reports, copublicado con The Washington Post y El Universal, el 8 de diciembre de 2024, https:// www.lighthousereports.com/investigation/ drownings-and-deterrence-in-the-riogrande/#:~:text=Our%20data%20on%20 drownings%20reveals,increasingly%20 dying%20in%20the%20river.

16 Melissa del Bosque, “A New Phase in Border Militarization: Trump’s ‘National Defense Areas’” [Una nueva fase en la militarización fronteriza: las ‘Áreas de Defensa Nacional’ de Trump], The Border Chronicle , el 8 de mayo de 2025, https://www. theborderchronicle.com/p/a-new-phase-inborder-militarization.

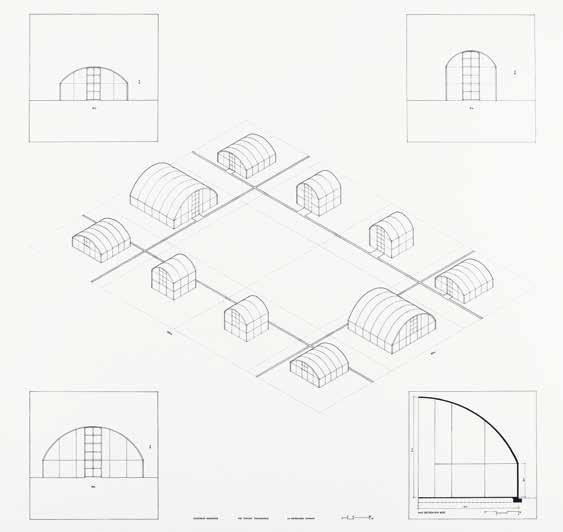

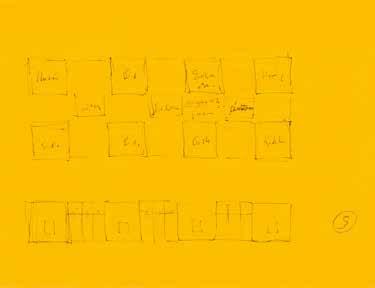

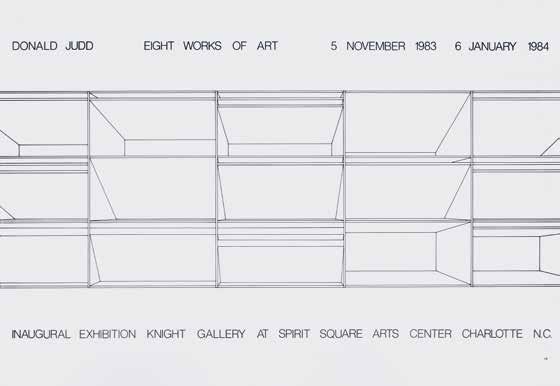

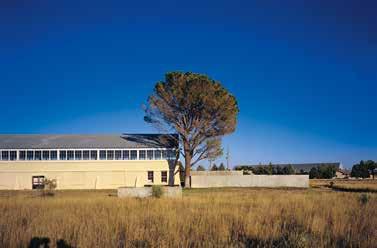

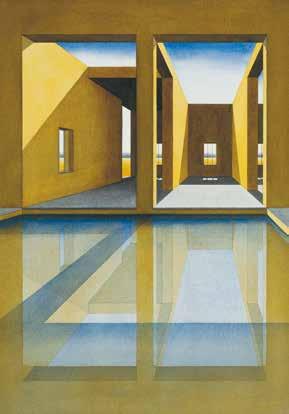

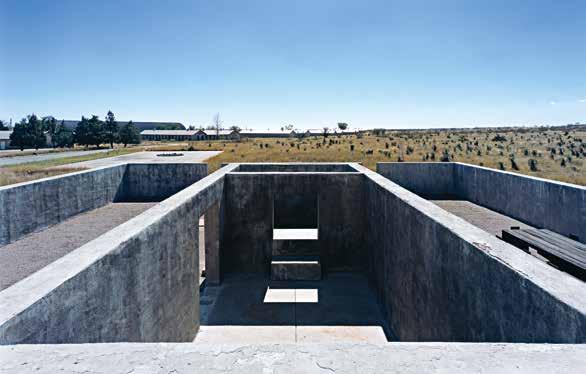

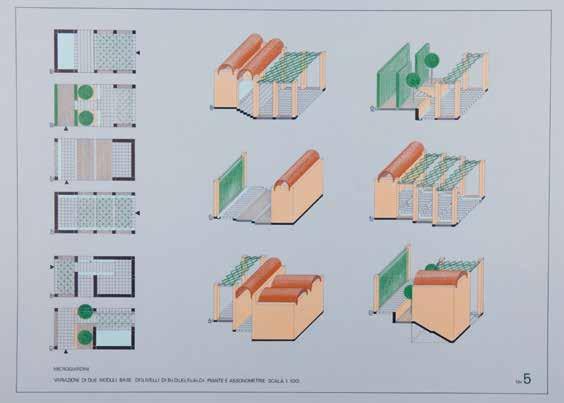

When Donald Judd entered into a contractual agreement with the Dia Art Foundation in 1979, the “Marfa project,” Dia funded not only the purchase of Fort D. A. Russell in Marfa and the transformation of many extant buildings on this 340-acre defunct army base but also commissioned Judd to create new artworks intended to be permanently on view there. This approach yielded many of the Chinati Foundation’s best-known installations, including Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, housed in two former artillery sheds, and his 15 untitled works in concrete, situated outdoors on the grounds. But with Dia’s support, Judd also produced eighteen artworks—thirteen horizontal progressions, three vertical stacks, and two freestanding works (the U and V channel pieces)—that never found a permanent home during his lifetime. Several years after fabricating these artworks, Judd explored installing them in a series of new concrete buildings he designed for a site on the western edge of the fort’s grounds. Judd’s plan to build from the ground up consisted of a rectangular plot of land subdivided into a twelve-square

Cuando Donald Judd firmó un contrato con la Dia Art Foundation en 1979 para el “proyecto Marfa”, Dia financió no solo la compra del Fuerte D. A. Russell en Marfa y la transformación de muchos de los edificios existentes en esta base militar abandonada de 1.376 kilómetros cuadrados, sino que también encargó a Judd la creación de nuevas obras de arte destinadas a exhibirse allí de forma permanente. Este enfoque dio lugar a algunas de las instalaciones más conocidas de la Fundación Chinati, incluidas las 100 obras sin título en aluminio en bruto, ubicadas en dos antiguos cobertizos de artillería, y las 15 obras sin título en hormigón, situadas al aire libre en los terrenos. Pero con el apoyo de

grid, with ten buildings occupying the squares on the perimeter and two squares left open in the center [fig. 3]. A brief construction phase from 1987 to 1988 resulted in two incomplete concrete structures, and from 1989 until Judd’s death in 1994 no further work was done on the buildings or the installation of these eighteen works, which have remained without a permanent context for viewing at Chinati.

Dia, Judd también produjo dieciocho obras —trece progresiones horizontales, tres pilas verticales y dos obras independientes (las piezas en forma de canal U y V)— que nunca encontraron un lugar permanente durante su vida. Varios años después de fabricar estas obras, Judd exploró la posibilidad de instalarlas en una serie de nuevos edificios de hormigón que diseñó para un emplazamiento en el extremo occidental del terreno del fuerte. El plan de Judd de construir desde cero consistía en una parcela rectangular de tierra subdividida en una cuadrícula de doce cuadrados, con diez edificios ocupando los cuadrados del perímetro y dos cuadrados abiertos en el centro [fig. 3]. Una breve fase de construcción de 1987 a 1988 dio como resultado dos estructuras de hormigón incompletas, y desde 1989 hasta la muerte de Judd en 1994 no se avanzó más en los edificios ni en la instalación de estas dieciocho obras, que aún no cuentan con un contexto permanente para su exhibición en Chinati.

Aquí, Erica Cooke y Julian Rose reconsideran el legado de estas obras y exploran las implicaciones de los planes de Judd para instalarlas en edificios de nuevo diseño y construcción.

Here, Erica Cooke and Julian Rose reconsider the legacy of these works and explore the implications of Judd’s plans to install them in newly designed and constructed buildings.

JULIAN ROSE: I’m thrilled to join you for this conversation because I think Judd’s plans for these ten concrete buildings represent the precise intersection of our research interests. On the one hand, this was the only time in his life that he designed ground-up buildings to house specific artworks, so the project represents a watershed in his thinking about exhibition spaces. On the other hand, the eighteen works themselves—and the thirteen horizontal progressions, in particular—are crucial for understanding how Judd thought about his work in relation to the surface of the wall, and for how he thought about the relationship between two and three dimensions more generally.

The concept of the “room”—an enclosed unit of space that establishes the context for the artwork within— has been important for both of us in understanding Judd, so I’d like to begin there. When do you think the room became important for Judd? Was it when he first moved off the wall and onto the floor, from his early paintings and reliefs to his first freestanding works? Or was it later, when he moved back to the wall with his stacks and progressions?

ERICA COOKE: The general literature on Judd often wants to find “origin” works that define transitional

3. CLAUDE ARMSTRONG AND DONNA COHEN, AXONOMETRIC DRAWING FOR DONALD JUDD’S CONCRETE BUILDINGS AT THE CHINATI FOUNDATION, 1987. INK ON

PAPER. 42 × 42 IN. / CLAUDE ARMSTRONG Y DONNA COHEN, DIBUJO AXONOMÉTRICO PARA LOS EDIFICIOS DE HORMIGÓN DE DONALD JUDD EN LA FUNDACIÓN CHINATI, 1987.

DE CALCO. 106,7 × 106,7 CM

JULIAN ROSE: Me entusiasma participar con usted en esta conversación porque creo que los planes de Judd para estos diez edificios de hormigón representan la intersección precisa de nues -

moments in his career. But when I think about Judd first exploring what it means to install his work in a room— engaging with that concept of a continuous space defined by walls, floor,

tros intereses de investigación. Por un lado, fue la única vez en su vida que diseñó edificios desde cero para albergar obras específicas, por lo que el proyecto representa un punto de inflexión en su forma de pensar sobre los espacios de exhibición. Por otro lado, las dieciocho obras en sí —y las trece progresiones horizontales, en particular— son fundamentales para entender cómo Judd concebía su obra en relación con la superficie de la pared, y cómo pensaba la relación entre lo bidimensional y lo tridimensional en general. El concepto de la “sala” —una unidad de espacio cerrado que establece el contexto para la obra de arte que contiene— ha sido importante para ambos en la comprensión de Judd, así que me gustaría empezar por ahí. ¿Cuándo cree que la sala se volvió importante para Judd? ¿Fue cuando dejó la pared y pasó al suelo, desde sus primeras pinturas y relieves hasta sus primeras obras exentas? ¿O fue más tarde, cuando volvió a la pared con sus pilas y progresiones?

ERICA COOKE: La literatura general sobre Judd a menudo intenta encontrar obras “de origen” que definan momentos de transición en su carrera. Pero

and ceiling extending along horizontal and vertical axes—what comes to mind is more of a constellation of objects as seen in Judd’s solo exhibition at Green Gallery, in 1963, when he installed a combination of floor and wall-bound works [figs. 1, 2].

JR: What was it about that show in particular?

EC: To begin with, the extraordinary spatial complexity of several of the objects themselves. This installation included the cadmium-red box with semicircular slats subdividing its interior [fig. 4]. That work really creates tension between internal and external space because the internal divisions substantiate a space within a space, raising the question of whether an object can be both container and contained.

It’s shown next to what we could call one of Judd’s first “reliefs,” where he has attached curved galvanized steel to the top and bottom edges of a painted plywood rectangle [fig. 5]. Judd claimed that he resorted to these materials after he had attempted, but failed, to suitably curve the edges of a canvas. With untitled (1961), he’s asking, What does it mean when an object is affixed to the wall, but also appears to project off the wall and enter space?

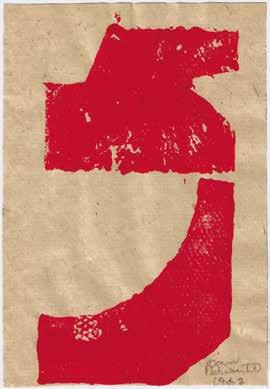

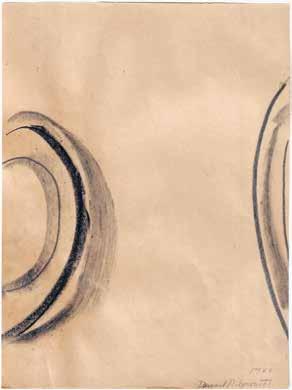

Then, also hanging on the wall, there are three woodblocks that Judd had used to make prints—which were not themselves on view. Many people don’t know that these blocks were included in the show because they were not photographed, but I think they made a crucial conceptual contribution to this constellation I’m describing [fig. 7]. They are very much about the notion of sequential disclosure:

cuando pienso en Judd explorando por primera vez lo que significa instalar su obra en una sala —interactuando con ese concepto de un espacio continuo definido por paredes, suelo y techo que se extiende a lo largo de ejes horizontales y verticales—, lo que me viene a la mente es más una constelación de objetos como se ve en su exposición individual en la Green Gallery, en 1963, cuando instaló una combinación de obras en el suelo y en la pared [figs. 1, 2].

JR: ¿Qué tenía de especial esa exposición?

EC: Para empezar, la extraordinaria complejidad espacial de varios de los objetos en sí. Esta instalación incluía la caja de color rojo cadmio con listones semicirculares que subdividen su interior [fig. 4]. Esa obra realmente crea tensión entre el espacio interno y el externo, porque las divisiones internas consolidan un espacio dentro de otro espacio, planteando la pregunta de si un objeto puede ser tanto contenedor como contenido.

Se muestra junto a lo que podríamos llamar uno de los primeros “relieves” de Judd, donde ha fijado acero galvanizado curvado en los bordes superior e inferior de un rectángulo de madera contrachapada pintada [fig. 5]. Judd afirmó que recurrió a estos materiales después de haber intentado, sin éxito, curvar adecuadamente los bordes de un lienzo. Con sin título (1961), se pregunta: ¿Qué significa un objeto cuando está fijado a la pared, pero también parece proyectarse y entrar en el espacio? Luego, también colgadas en la pared, hay tres planchas de madera que Judd había utilizado para hacer grabados, los cuales no estaban en exhibición. Mucha gente no sabe que estas planchas fueron incluidas en la muestra

to experience these three works is to absorb the fact that you are seeing three distinct variants of a woodblock, or rather three different ways that the artist has carved lines into woodblocks of identical dimensions. Each is considered an individual work, but, within the space of the gallery, they seemingly exist together as a whole.

JR: That seems like an important idea to capture as we think about Judd extending his work into the room: How do these things on the wall exist independent of each other, but also together?

EC: I’m imagining myself back in time—in New York City circa 1963— visiting the Green Gallery. There is no privileged view of any given work; instead, I must move around the room and gather manifold viewpoints—not only of each artwork, but of artworks in relation to each other, and then in relation to the room itself. And my encounter with this spatial context is much more uninhibited than it would be in a traditional exhibition of painting and sculpture in 1963 because Judd made a radical decision to not place his works on pedestals or inside of vitrines or within frames. He wished for the viewer to have a much more direct encounter with the work of art.

porque no fueron fotografiadas, pero creo que hicieron una contribución conceptual crucial a esta constelación que estoy describiendo [fig. 7]. Se centran profundamente en la noción de revelación secuencial: experimentar estas tres obras es absorber el hecho de que estás viendo tres variantes distintas de una plancha de madera, o más bien, tres maneras diferentes en que el artista ha tallado líneas en bloques de madera de dimensiones idénticas. Cada una se considera una obra individual, pero, dentro del espacio de la galería, aparentemente existen juntas como un todo.

JR: Esa parece una idea importante a capturar mientras pensamos en Judd extendiendo su obra hacia el espacio de la sala: ¿Cómo existen estas cosas en la pared de manera independiente, pero también como parte de un conjunto?

EC: Me imagino a mí misma retrocediendo en el tiempo —en la ciudad de Nueva York, hacia 1963—, visitando la Green Gallery. No hay una vista privilegiada de ninguna obra en particular; en cambio, debo moverme por la sala y reunir múltiples puntos de vista, no solo de cada obra, sino de las obras entre sí, y luego en relación con la sala misma. Y mi encuentro con este contexto espacial es mucho más libre de lo que sería en una exposición tradicional de pintura y