A conference sponsored by the Center for Theology and Ethics in Catholic Health and the Institute for the Liberal Arts at Boston College

MARCH 20-21, 2026, AT BOSTON COLLEGE

Keynote Speaker

The “Artificial Intelligence, Authentic Mercy: Navigating AI Ethics in Catholic Health” conference will bring together physicians, nurses, health care administrators, biomedical engineers, technologists, theologians and ethicists to explore the opportunities and challenges presented by AI in Catholic health care settings. The goal is to ethically analyze AI in health care through the lens of Catholic moral teaching and theological ethics.

Illustrations by J.S. Dykes

4 ACCESSIBLE, AFFORDABLE, BENEFICIAL: HOW CAN U.S. HEALTH CARE BE RESHAPED TO BETTER SERVE PATIENTS?

Elizabeth Garone

9 TREATING FEAR: STEPS TO HELP YOUR IMMIGRANT PATIENTS

Monica Maalouf, MD, Amy Blair, MD, and Mark Kuczewski, PhD

15 RALLYING AROUND RURAL CARE: HOSPITALS STRIVE TO DELIVER ACCESSIBLE SERVICES

Robin Roenker

22 ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE WITH A PURPOSE AT PROVIDENCE

Sara Vaezy, MHA, MPH

26 ACCOUNTABLE CARE ORGANIZATIONS SAVE BILLIONS, BUT STRUGGLES REMAIN IN THE SHIFT TO VALUE-BASED CARE

Kelly Bilodeau

32 MARYLAND’S TOTAL COST OF CARE MODEL ALIGNS HEALTH INNOVATION WITH MISSION-DRIVEN CARE

Mitch Lomax, MBA, Trevor Bonat, MA, MS, and Olivia D. Farrow, Esq.

36 PLACE HUMAN DIGNITY AT THE CENTER OF HEALTH CARE REFORMS

Sarah Reddin, D.HCML, and Richard Fogel, MD, FACC, FHRS

40 FINDINGS FROM CHA SURVEY: FORMATION REACHES DEEPER INTO MINISTRIES, INCREASES DEMAND FOR NEW RESOURCES

Darren M. Henson, PhD, STL

2 EDITOR’S NOTE BETSY TAYLOR

47 COMMUNITY BENEFIT

What’s the Point of Doing a Needs Assessment and Improvement Plan if They Don’t Lead To Real Change?

STEPHANIE MOXLEY, CAROLINE GAGNE and MADISON THOMPSON

50 ETHICS

50 Years Later: The Enduring Legacy of Karen Ann Quinlan Continues to Influence End-of-Life Decisions

BRIAN M. KANE, PhD

54 MISSION Weaving Foundational Mission-Related Competencies Into Workplace Expectations

DENNIS GONZALES, PhD, BART RODRIGUES, MDiv, MA, MBA, JOYCE MARKIEWICZ, RN, BSN, MBA, and LAURA CIANFLONE, MA

58 FORMATION

A Sign of Hope, 30 Years Later

DARREN M. HENSON, PhD, STL

61 THINKING GLOBALLY

Why We Need Serenity, Courage and Wisdom Now to Protect Our Most Vulnerable BRUCE COMPTON and NEERAJ MISTRY, MD

31 POPE LEO XIV — FINDING GOD IN DAILY LIFE

64 PRAYER SERVICE

IN YOUR NEXT ISSUE AGING & LONGEVITY

When it comes to thinking about this issue of Health Progress exploring Health Care Across America, it’s helpful to consider: What are our values, and how are those reflected in our health care system?1

In a Catholic care environment, articulation of values is clearer than in many other settings, and consideration of that question is woven throughout this issue. And I think this question leads to other ones, including: Who do we value? In Catholic social teaching, the Church “proclaims that human life is sacred and that the dignity of the human person is the foundation of a moral vision for society.” As the U.S. bishops summarize in a reflection on these teachings, “We believe that every person is precious, that people are more important than things, and that the measure of every institution is whether it threatens or enhances the life and dignity of the human person.”2

We don’t just value someone if they’ve got the correct papers and pay their bills. Those matters are important, but they’re not the litmus test by which a Catholic health care ministry provides care. Are our institutions threatening or enhancing the life and dignity of all people? And if, in Catholic institutions, we feel we do better at this than some other organizations — or at least aspects of it better — is there a way to raise our voices together to tend to a national health care system in need of reimagination?

Across our nation, people are confused by a splintered health care system. They may swim in medical debt, have trouble understanding a doctor’s guidance, or be in pain, afraid or even just bone-tired. I could cite a study, but every one of us has seen this with our own eyes at one point or another.

And it is not enough to shrug off a broken system, because we — Catholic health care collectively — are in the system-fixing business. And we are in the system-fixing business because the nation’s patients deserve nothing less than that.

1. This video, by The Washington Post, features a lot of food for thought about other nations’ health care systems, and what they may reveal about our own system, including a few speakers who discuss the role that a society’s values play related to its health care system: “What Experts Say About Who Has the World’s Best Health Care System-Opinion,” The Washington Post, June 17, 2021, YouTube video, 9:14, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=wfsJXo1h1G0.

2. “Seven Themes of Catholic Social Teaching,” United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, https://www.usccb.org/beliefs-and-teachings/ what-we-believe/catholic-social-teaching/ seven-themes-of-catholic-social-teaching.

VICE PRESIDENT, COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING

BRIAN P. REARDON

EDITOR

BETSY TAYLOR btaylor@chausa.org

MANAGING EDITOR

CHARLOTTE KELLEY ckelley@chausa.org

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

NORMA KLINGSICK

ADVERTISING 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797, 314-253-3447; fax 314-427-0029; email ads@chausa.org.

SUBSCRIPTIONS/CIRCULATION Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to Service Center, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone 800-230-7823; email servicecenter@chausa.org. Annual subscription rates are: complimentary for those who work for CHA members in the United States; $29 for nonmembers (domestic and foreign).

ARTICLES AND BACK ISSUES Health Progress articles are available in their entirety in PDF format on the internet at www.chausa.org. Photocopies may be ordered through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923. For back issues of the magazine, please contact the CHA Service Center at servicecenter@chausa.org or 800-230-7823.

REPRODUCTION No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from CHA. For information, please contact copyright@chausa.org.

OPINIONS expressed by authors published in Health Progress do not necessarily reflect those of CHA. CHA assumes no responsibility for opinions or statements expressed by contributors to Health Progress.

2025 AWARDS FOR 2024 COVERAGE

Catholic Media Awards: Magazine of the Year — Professional and Special-Interest Magazines, Second Place; Best Cover — Small, First Place; Best Special Section, Second Place; Best Special Issue, First Place; Best Regular Column — Spiritual Life, Honorable Mention; Best Coverage — Disaster or Crises, Third Place; Best Feature Article — Professional and Special-Interest, Third Place; Best Reporting of Social Justice Issues — Dignity and Rights of the Workers, Second Place; Hot Topic — Eucharistic Revival, Third Place; Hot Topic — 2024 Election, Third Place; Best Writing — Analysis, First Place; Best Writing — In-Depth, Second Place.

American Society of Business Publication Editors Awards: Print — Special Section, National Bronze Award and Regional Gold Award; All Content — How-To Article, Regional Silver Award.

Produced in USA. Health Progress ISSN 0882-1577. Fall 2025 (Vol. 106, No. 4).

Copyright © by The Catholic Health Association of the United States. Published quarterly by The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797. Periodicals postage paid at St. Louis, MO, and additional mailing offices. Subscription prices per year: CHA members, free; nonmembers, $29 (domestic and foreign); single copies, $10.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Health Progress, The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797.

Follow CHA: chausa.org/social

Trevor Bonat, MA, MS, chief mission integration officer, Ascension Saint Agnes, Baltimore

Sr. Rosemary Donley, SC, PhD, APRN-BC, professor of nursing, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh

Fr. Joseph J. Driscoll, DMin, director of ministry formation and organizational spirituality, Redeemer Health, Meadowbrook, Pennsylvania

Jennifer Stanley, MD, physician formation leader and regional medical director, Ascension St. Vincent, North Vernon, Indiana

Rachelle Reyes Wenger, MPA, system vice president, public policy and advocacy engagement, CommonSpirit Health, Los Angeles

Nathan Ziegler, PhD, system vice president, diversity, leadership and performance excellence, CommonSpirit Health, Chicago

ADVOCACY AND PUBLIC POLICY: Lisa Smith, MPA; Kathy Curran, JD, MA; Clay O’Dell, PhD; Paulo G. Pontemayor, MPH; Lucas Swanepoel, JD

COMMUNITY BENEFIT: Nancy Zuech Lim, RN, MPH

CONTINUUM OF CARE AND AGING SERVICES: Indu Spugnardi

ETHICS: Nathaniel Blanton Hibner, PhD; Brian M. Kane, PhD

FINANCE: Loren Chandler, CPA, MBA, FACHE

GLOBAL HEALTH: Bruce Compton

LEADERSHIP AND MINISTRY DEVELOPMENT: Diarmuid Rooney, MSPsych, MTS, DSocAdmin

LEGAL, GOVERNANCE AND COMPLIANCE: Catherine A. Hurley, JD

MINISTRY FORMATION: Darren Henson, PhD, STL

MISSION INTEGRATION: Dennis Gonzales, PhD; Jill Fisk, MATM

PRAYERS: Karla Keppel, MA; Lori Ashmore-Ruppel

THEOLOGY AND SPONSORSHIP: Sr. Teresa Maya, PhD, CCVI

HEALTH CARE ACROSS AMERICA

ELIZABETH GARONE

Contributor to Health Progress

As a cardiologist in the Philadelphia area, Dr. Peter Kowey treated countless patients over the decades for different heart ailments. So, he wasn’t surprised when he received a call from one of them. What was surprising was that the patient was asking him about her hip replacement surgery. She was in extraordinary pain and had gone in to see her surgeon for a follow-up appointment.

“The surgeon came in and said, ‘This device is broken. We’re going to have to replace it,’ and then he walked out, leaving her with a gazillion questions,” said Kowey. Totally frustrated and unable to get her questions answered, she called Kowey, knowing he would take the time to explain everything to her.

As anyone enmeshed in the world of health care will share, doctors are under increasing pressure to see more patients but for shorter amounts of time, often to bolster the bottom line. Compounding this and other pressures is the uncertainty around the future of the health care landscape with the July 4, 2025, passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). One aspect remains certain: The health care system has a lot of work to do to make care more accessible, affordable and beneficial to everyone, especially given the constraints of the new law, with many pieces of the legislation going into effect in 2026. The Congressional Budget Office is projecting OBBBA to cause around a $1 trillion reduction in federal health care spending through 2034 and increase the number of uninsured people by 10 million.1

As health care continues along this uncer -

tain path, there are many issues that need to be addressed.

For doctors to do their jobs well and for patients to get the answers they need, something has to give, according to Kowey, a professor of medicine and clinical pharmacology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia who recently authored the book Failure To Treat: How a Broken Healthcare System Puts Patients and Practitioners at Risk. Otherwise, very few doctors can give the attention and care necessary to fully address patients’ concerns and symptoms.

“We’re stacking the patient schedule every 15 to 20 minutes per patient, and the patients suffer, of course, because they don’t think that they have enough time,” said Kowey. “By the time the technician puts the patient in the room and gets a cardiogram and vital signs, we’re halfway through the visit. So, part of the problem is that even when you get in, you don’t necessarily have a satisfactory visit, or that you don’t walk out feeling like you got what you needed.”

It isn’t just patients feeling unsatisfied. Due to

myriad pressures, physicians are walking away or retiring earlier than planned. In a recent MedCentral survey, more than one-third (35%) of physicians said they have considered leaving the medical practice since the start of 2025. Top reasons cited include personal burnout, early retirement and clinical demands. 2 If the current situation continues, the U.S. can expect a physician shortage of up to 86,000 physicians by 2036, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.3

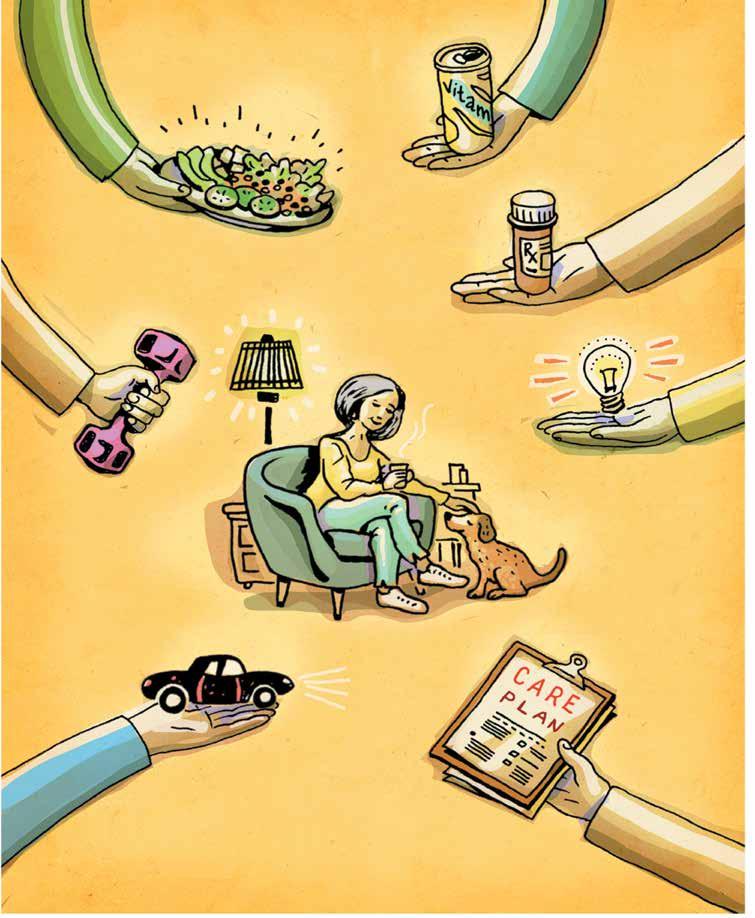

One area that needs to be addressed is the haphazard approach to health care in the U.S., according to Dr. Jeff Salvon-Harman, CPE, CPPS, vice president of safety for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). “In the U.S., we have not done a great job at keeping people from becoming patients,” he said. “As a result, what we’re seeing that is affecting hospitals is patients with four or five chronic, comorbid conditions that impact each other, such that when any one of them causes an acute complication, the multiple others that are in the background are also being impacted. We have to do a better job in communities, in ambulatory care, in primary care, not only delivering care, but creating safer environments for people, so that people don’t have to become patients.”

In 2023, approximately 76% of U.S. adults reported one or more chronic conditions, and about 51% reported multiple chronic conditions. That number jumped to nearly 79% for older adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4

A more strategic approach needs to be taken, according to Salvon-Harman. “Part of what we have to acknowledge is that the health care system that we have today did not come to be through intentional design. Nobody convened a committee or a working group or a task force to say, ‘Let’s design perioperative care for the whole country. Let’s design primary care for the whole country. Let’s design specialty care, inpatient and outpatient for the whole country.’ Every health system has pulled together, starting out with individual hospitals becoming multiple hospitals, and then becoming a large organization. They’ve adapted and adopted and added as they needed to for their business models or as care paradigms changed.”

At New Jersey’s Saint Peter’s Healthcare System,

President and CEO Leslie Hirsch is seeing the shift from inpatient to outpatient visits that many hospitals across the country are experiencing. Medical procedures that, in the past, would have required multiple days in the hospital, such as hip surgery, can now be done as a one-day appointment for otherwise healthy patients.

While the advancements in technology that make this possible are, as Hirsch describes, “incredible,” it has also meant that insurers want to pay less wherever they can. “The role that insurers play in pre-authorization and denials for consumers and then for providers has resulted in an extremely complex and frustrating system for both consumers and providers,” said Hirsch. Even if a patient stays in the hospital for multiple nights, but insurance classifies them as “observation status,” they are still considered an outpatient. That means insurance pays a fraction of what it would have paid had it been an inpatient visit, yet the patient is receiving the same level of care and services, and the hospital is using just as many resources and staff. “What’s going to happen is the payer, the insurance company, is going to deny us payment on that, and then we’re going to have to appeal,” he said. Hospitals end up having to leave millions of dollars on the table because of this. “It’s just this is the game that insurers play,” said Hirsch.

Technological advances have saved many lives and a lot of time, but they must be carefully implemented, according to Salvon-Harman. Many manual surgeries and open surgeries have become laparoscopic and are now becoming robotic. “Those kinds of changes happen over time. None of that was intentional. Nobody said, ‘We need to have a robot to do surgeries, because it’ll be better than laparoscopes and open surgeries.’ The technology evolved and emerged, and we said, ‘Yes, we could use that because that looks like it’s better, that might be more effective, that might be more consistent [for some surgeries].’”

As a result of the way our health system has evolved, there are a lot of inconsistencies. “When you move across one organization to another, sometimes even within the same parent organization, different sites of care may be doing things differently. And so, we’re always trying to balance the structures, the processes and the culture of the large parent organization, but also each and

every one of the individual sites of care, whether a hospital or an outpatient practice,” said SalvonHarman. “So, there’s still a lot to do around achieving those higher levels of consistency and, in some cases, being in sync with other parts of the system. Technology holds some promise in closing some of those gaps, moving us in that direction, but it hasn’t yet done it completely successfully.”

Many of the new technologies are intended to help us “work smarter, rather than harder, and are supposed to increase the efficiency or the effectiveness of what we do,” said Salvon-Harman. But we need to be cognizant of the ways they introduce additional complexity. “They have a learning curve for how to use them optimally. They have various influences, like what we call human factors: how the human interfaces with that piece of equipment or that technology that may introduce risk at the same time that it is eliminating other risks.”

At the same time, we are at a point when new technologies must be embraced, as they can keep health care moving forward and are what many patients have come to expect, according to Yunan Ji, an assistant professor of strategy with a focus on the design and regulation of health care markets at the Georgetown University McDonough School of Business. With more transparent pricing than in the past, health care organizations also need to find effective ways to communicate “nonprice attributes,” such as clinical outcomes and patient experience, in ways that resonate with consumers who are making choices about where to receive care.

platforms — ranging from online scheduling and virtual visits to personalized cost estimators and mobile engagement tools — will be better positioned to attract and retain patients. In a competitive environment where convenience, transparency and digital experience matter more than ever, digital maturity is becoming a key differentiator for providers.”

At Bon Secours Mercy Health, one of the goals is to make health care easier for patients and for consumers. In 2024, Bon Secours Mercy Health launched a conversational, artificial intelligence (AI)-powered digital guide called “Catherine,” (named in honor of Catherine McAuley, the founder of the Sisters of Mercy) aimed at transforming how patients access information and resources when they have knee, hip and shoulder pain.5

“Conversational AI represents the modern era of patient engagement,” said David Cannady, Bon Secours Mercy Health’s chief strategy officer. “It’s time to offer a solution that goes beyond what patients can currently access in Google searches or on social media platforms.” In addition, the health system is working toward same-day access

“In a competitive environment where convenience, transparency and digital experience matter more than ever, digital maturity is becoming a key differentiator for providers.”

— YUNAN JI

“This shift also reflects a broader transformation toward a more digital, consumer-oriented health care ecosystem — accelerated by the rise of telemedicine, on-demand care and virtual-first models. Just as consumers have come to expect seamless, intuitive digital experiences in sectors like retail and banking, they now bring those same expectations to health care, particularly for elective services, outpatient care and administrative interactions,” Ji said. “Hospitals and health systems that invest in modern, user-friendly digital

for patients, which Cannady believes will be driven by AI and automation. “We utilize AI to help patients access the right care at the right time by simplifying the process, from appointments and scheduling to finding the appropriate provider for their health needs, whether preventive or acute.”

Leaders at Bon Secours Mercy Health are watching several legislative and regulatory discussions that could have a potential impact on patient care and the providers of that care, said Cannady. “Key topics include Medicaid and Affordable Care Act

Exchange enrollment eligibility and other proposed reductions,” he said. “Should enrollment and public program reimbursement decline, health systems might face decisions such as the rationing of services to sustain a viable community-based model of care. In some cases, unfortunately, there may be closures of service lines or even hospitals in rural and other communities.”

For IHI’s Salvon-Harman, it means thinking about new delivery paradigms, new ways to identify what is meaningful. “Is it better for a patient to have a 15-minute appointment monthly, three months in a row? Or is it better for that patient to have 45 minutes with their health care provider one time in three months but get a much more substantive dose of health care in that 45-minute appointment?” he asked. “Do we need to think about how we acquire information in the health care setting, and how we process information? Do the standard tools for a history and physical examination that have been taught for over 100 years and used for over 100 years still serve the purpose?”

He suggests we look at adapting those models and collecting information differently so we can analyze that information, and we can apply the thinking from that analysis to each patient. “I feel like that’s really where we’re at now in ambulatory care: needing to really question the models we’ve been using and their effectiveness, and identifying and testing new models to see if they enhance our ability to diagnose more accurately, more timely,” said Salvon-Harman. “And to better coordinate across different specialties more efficiently and effectively, creating venues for more cross talk in real time, across specialties and across providers, leveraging AI and leveraging virtual technology to support better information sharing closer to real time. I think those are a lot of the opportunities that are emerging but haven’t yet been successfully harnessed.”

There are also error and human factors, according to Thomas Jefferson’s Kowey. While AI and technology can help, they can’t replace human judgment. “We’re not dealing with widgets here. We’re dealing with biological organisms with feelings, with emotions, with expectations, with

fear and anxiety,” he said.

Everything comes down to making systemic changes, according to Kowey, who was motivated to write his book by the “tremendous number of problems” in the U.S. health care system. “As the title says, it’s broken. It’s impacting both the quality of patient care and the well-being of providers. Burnout is real. But I truly believe it doesn’t have to be this way,” he said. “It’s a call to action for patients, legislators, administrators and providers. We still have options, but not a whole lot of time. If things keep going the way they are, we may lose the quality of care we’ve come to expect, possibly for good.”

ELIZABETH GARONE is a freelance writer who has covered health, business and human-interest topics. Her writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, BusinessWeek and The Mercury News, among other publications.

1. “Health Provisions in the 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation Law,” KFF, August 22, 2025, https://www.kff. org/medicaid/health-provisions-in-the-2025-federalbudget-reconciliation-law.

2. Marcia Frellick, “Survey Shows One-Third of Physicians Considering Leaving Medicine,” MedCentral, June 17, 2025, https://www.medcentral.com/biz-policy/ survey-shows-one-third-of-physicians-consideringleaving-medicine.

3. “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036,” Association of American Medical Colleges, March 2024, https://www. aans.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/aamc-2023workforce-projections-report.pdf.

4. Kathleen B. Watson et al., “Trends in Multiple Chronic Conditions Among U.S. Adults, by Life Stage, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2013–2023,” Preventing Chronic Disease 22 (2025): http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5888/pcd22.240539.

5. “Mercy Health Cincinnati First to Launch AI Powered Digital Assistant,” Mercy, December 20, 2024, https://www.mercy.com/news-events/news/ cincinnati/2024/mercy-health-cincinnati-first-tolaunch-ai-powered-digital-assistant.

MONICA MAALOUF, MD, AMY BLAIR, MD, and MARK KUCZEWSKI, PhD

Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Chicago

First, remember your vocation. Caring for patients is the main thing that doctors, nurses and health care professionals do. Navigating the nuances of immigration policy? Not so much. Unfortunately, immigration enforcement has become highly politicized, impeding the ability of healers to effectively treat their patients and to promote their health. Health care professionals need tools to address the social influencers of health related to immigration enforcement.

Discussing immigration often arouses suspicion of a hidden political agenda. However, the duty to care for patients is at the heart of the healer-patient relationship.1 Health care professionals are trained to set aside personal opinions and reactions to social circumstances in the service of optimizing patient care. Policies and opinions of recognized professional bodies, such as the American Medical Association, support addressing immigration-related barriers to care.2 We propose actions for clinicians that follow from the values that comprise the identity of the healing professions.

Because Catholic health care institutions espouse a commitment to carry out the healing ministry of Jesus Christ, marginalized and stigmatized patients are a focus of attention. Migrants and refugees are often among the named groups for which Catholics and Catholic institutions must exercise special care because they are politically underrepresented and lack opportunities to make their voices and concerns heard. As Pope John Paul II stated, “The Church in America must be a vigilant advocate, defending against any unjust

restriction the natural right of individual persons to move freely within their own nation and from one nation to another. Attention must be called to the rights of migrants and their families and to respect for their human dignity, even in cases of nonlegal immigration.”3

This recognition of migrants’ dignity or worth as rooted in their humanity has a long history that cuts across differences between so-called “liberal” or “conservative” Catholics and is encoded in key documents such as the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Pope Francis articulated that the situation of migrants should be seen as on par with “grave” bioethical questions.4 Of course, these foundational teachings are distilled into Catholic health care’s touchstone, the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs).

The ERDs articulate the social mission of Catholic health care to those “whose social condition puts them at the margins of our society ... immigrants and refugees.”5 And they remind us that our respect for the worth or dignity of the human person “extends to all persons who are served by Catholic health care.”6 Undermining

that mission by violating patient privacy or in any way violating the trust of vulnerable patients cannot be tolerated.

Employees of a Catholic health care institution must respect and uphold the religious mission of the institution and adhere to these Directives. They should maintain professional standards and promote the institution’s commitment to human dignity and the common good.7

Second, create a culture of safety in the providerpatient relationship. The Trump administration has rescinded guidance that designated hospitals as protected sites, locations where routine immigration enforcement should not take place.8 For many who are undocumented, the act of seeking care and providing personal information is now an act of courage. Recent reports show that since the beginning of the year, 20% of lawfully present immigrants in the U.S. say they or a family member have limited their participation in activities outside the home due to concerns about drawing attention to immigration status.9

patients of varying immigration status. The key tenets of this approach include open-ended communication, collaborative care approaches, active listening and empathy.

Open-ended communication is essential to ensure patients can guide the visit, express their goals and health concerns, and not feel pressured by the provider’s priorities for the visit. Openended questions also help frame patients as active agents in sharing their health care story, provide them with a sense of control, and increase the collaborative nature of the visit.11

As patients feel a baseline sense of safety, providers can enhance a deeper sense of trust through active listening. This skill can help the provider elicit clues, either verbal or nonverbal, that may signal the larger social and structural factors influencing the patient’s health. For example, patients may report a general sense of worry about current events or exhaustion over elements outside of their control. Patients may express worry about a family member or the ability to safely travel to appointments.

A provider who demonstrates empathy and communicates nonjudgmentally is more likely to assuage some of the fear brought by immigration status, allowing patients to access the care they need.

One way many people with immigrationrelated fears respond to increased immigration enforcement is to avoid health care altogether. In one study, Hispanic patients were less likely to report having a regular care provider or attending preventive visits.10 These patients were also less likely to present for diabetes care. The implications of this care avoidance can be devastating for individuals, resulting in social and financial losses due to illness going untreated, as well as the loss of early cancer detection and modifiable disease prevention.

For the physicians and providers who see and treat patients, fostering trust and a sense of safety is crucial to ensure patients do not fear accessing the care they need. The principles of trauma-informed care and patient-centered care are useful frameworks for addressing fear among

Providers may open additional avenues for conversation by normalizing fearful circumstances. For example, a provider might say, “Some of my patients find that current events are causing fear that affects their health. Is that something you have experienced?”

Another helpful strategy is summarizing what has been said to encourage specificity. For example, “You said that the chest pain is worse when you are feeling stressed. Can you tell me anything else about the situations that are particularly stressful for you right now?” These foundational patientcentered techniques can facilitate communication, validate patient concerns and foster safety for patients sharing their stories.

However, providers should also be cautious to avoid retraumatization or probing for details that a patient might be unwilling to share. Active listening can again be used to notice signs of discomfort or pauses in the patient’s story, demonstrating hesitancy. These situations warrant a slow and deliberate approach that focuses on the patient’s needs. Like all discussions of difficult topics in the health care setting, patients should feel in control and be able to slow or stop conversations at their

discretion.

A provider who demonstrates empathy and communicates nonjudgmentally is more likely to assuage some of the fear brought by immigration status, allowing patients to access the care they need. Patients who do feel comfortable discussing immigration status may disclose varying levels of details of past events or future fears. Providers in primary care relationships may choose to assure patients that they can talk about it again in the future, when the patients are ready.

Third, recognize and address the manifestations of fear. Accessing affordable health insurance is a complex task for most Americans, but even more so for immigrant patients. Undocumented patients face significant barriers because they are not eligible for federally funded programs such as Medicare or coverage through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. Most private insurance plans require a Social Security number or proof of lawful residency, which undocumented individuals typically cannot provide.

While federal Medicaid is largely off-limits to undocumented individuals, some states — including New York, California and Illinois — have created programs using state funds to fill in gaps, especially for children, those who are pregnant and those with urgent medical needs. However, financial challenges in public insurance have caused programs such as the Illinois Health Benefits for Immigrant Adults to be implemented, paused and then canceled, all in four years.12

manifest in the medical encounter. Some patients may ask for expedited or expansive testing that is outside of what is indicated by accepted standards of care. For example, women may ask for early mammograms or scans to “make sure” no serious complications are present. Some patients may also request additional refills of medications needed for diabetes, high blood pressure or other chronic diseases.

These requests stem from the uncertainty of both future insurance coverage and future ability to safely present for care. Patients who request additional services may be mistakenly written off by health care teams as unreasonable, overly anxious or experiencing somatization.

To optimize the health of all patients, providers should seek to understand the patient perspective and provide flexibility. Acknowledging the fear patients are experiencing and calling out the uncertainty of the system can also empower the patient-provider relationship. Helpful statements may include, “We cannot predict whether the policy (access) will change in the future, but I am an advocate for your health and will ensure we make the best decisions for you today.”

optimize the health of all patients, providers should seek to understand the patient perspective and provide flexibility. Acknowledging the fear patients are experiencing and calling out the uncertainty of the system can also empower the patient-provider relationship.

This rapidly changing landscape of eligibility and the prospect of financial catastrophe that people without health insurance face is at the forefront of patients’ decision-making. Turbulent times perpetuate fear and discomfort in seeking care. Beyond fears related to the cost of treatment, many who are undocumented avoid interfacing with public benefit systems simply to avoid disclosing private information that may compromise their safety.

For those patients who do seek health care, it is important for providers to recognize how fear can

Physicians can offer patients flexibility by offering virtual or telephone visits, after-hours health care options, and by providing extra refills of chronic medications between visits if it is safe to do so.

During these periods of legal and political uncertainty, it may be difficult for members of the health care team to project reassurance or calm, particularly when health care providers may have personal concerns about their rights or legal status. Relying on communities of practice focused on justice within a health care team is essential for maintaining strength amid uncertainty.

Fourth, make your clinic a safe and resourcerich environment. Earlier, we provided some ideas on interacting with patients to create a culture of safety in the provider-patient relationship. It is also important that health care professionals draw upon developed resources to make their clinic a safer place for these patients.

One easy-to-use resource to analyze your clinical environment’s preparedness for this era of ubiquitous immigration enforcement is the Model Policy developed by the Illinois Alliance for Welcoming Health Care. 13 This outstanding resource can walk you through the needed protocols of a “front door policy” to guide preparation for a potential entry into your facility by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement or other law enforcement officials seeking to perform immigration enforcement. It will also guide you through specific practices regarding the allimportant designation of private spaces. If you desire further context on how these practices fit with what other health care facilities have done, we recommend consulting the Doctors for Immigrants’ tool kit.14 Furthermore, patients need usable information to take control of their situation, including resources and emergency planning materials. The number of outstanding online resources that can help with these tasks is rapidly growing, and it is tempting to provide a long list of links. However, most patients are better served by referral to a small number of useful and reliable resources that will enable them to begin taking action.

easy access to reliable information is an important way that you can parlay your credibility into patient empowerment.

Above all else, become the healer your patients need. We have focused on basic ways to support immigrant patients. Becoming a maximally effective health care provider for these patients requires some skill development and refinement that can be tailored to your patient population. This requires engagement.

Engage with your relevant professional organizations. For instance, the American Academy of Pediatrics has a Council on Immigrant Child and Family Health, the Society of General Internal Medicine boasts an Immigrant and Refugee Health Interest Group, and the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities has an active Immigration Affinity Group. The American Medical Association regularly issues policy statements regarding the humane care of immigrant patients.

Engage with relevant community organizations. Such networks can enhance your ability to support your patients significantly.

Such communities foster values formation and provide information regarding current developments and patient needs. Similarly, keeping abreast of advocacy information that is posted by CHA can secure and build your foundational knowledge.16

The Sanctuary Doctor tool kit was created to provide this information in a succinct, one-stopshopping kind of way. The website is available in English and Spanish.15 Convenient two-sided wallet cards with the QR codes to the English and Spanish web pages are available upon request from sanctuarydoctor@luc.edu. This is an easy and unobtrusive way to provide patient access to needed information on finding an immigration lawyer and developing an emergency plan.

While pointing patients toward such resources may seem insignificant, immigrant communities are often preyed upon by opportunists who misrepresent themselves as attorneys and defraud this already vulnerable population. Providing

Engage with relevant community organizations. Such networks can enhance your ability to support your patients significantly. For instance, while the legal resources section of the Sanctuary Doctor tool kit can assist your patients in finding qualified representation in your area, networking with local immigration advocacy organizations often results in knowledge of nearby legal services available to low-income clients on a pro bono or sliding scale basis. Similarly, such organizations can provide services and workshops that empower your patients. Contact with such groups can also enhance your understanding of the concerns your patients are facing.

In closing, we hope that you will find this information useful and helpful in supporting your

patients. Do not be overwhelmed by concerns about being inadequate for the task or not yet having the knowledge and skills you believe are optimal. As with most aspects of clinical practice, assistance is all around you, and you will quickly come to see how valuable your efforts are. Most importantly, your patients will respond to your care and reward you with trust. And, of course, in a trusting relationship, your patients will also become your teachers.

At Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, DR. MONICA MAALOUF is an associate professor of medicine and the assistant dean of diversity, equity & inclusion. DR. AMY R. BLAIR is a professor of family medicine and is the assistant dean of medical education. MARK KUCZEWSKI is the Fr. Michael I. English, SJ, professor of medical ethics and the director of the Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics.

1. Sabrina Derrington et al., “Plan, Safeguard, Care: An Ethical Framework for Health Care Institutions Responding to Immigrant Enforcement Actions,” Hastings Bioethics Forum, April 1, 2025, https://www. thehastingscenter.org/plan-safeguard-care-an-ethicalframework-for-health-care-institutions-responding-toimmigrant-enforcement-actions/.

2. Rachel F. Harbut, “AMA Policies and Code of Medical Ethics’ Opinions Related to Health Care for Patients Who Are Immigrants, Refugees, or Asylees,” AMA Journal of Ethics 21, no. 1, (2019): https://journalofethics. ama-assn.org/article/ama-policies-and-codemedical-ethics-opinions-related-health-care-patientswho-are-immigrants/2019-01.

3. Pope John Paul II, “Ecclesia in America,” The Holy See, January 22, 1999, section 65, https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_ exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_22011999_ ecclesia-in-america.html.

4. Pope Francis, “Gaudete et Exsultate,” The Holy See, March 19, 2018, section 102, https://www.vatican.va/ content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/

papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20180319_gaudeteet-exsultate.html.

5. Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services: Sixth Edition (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018), 9.

6. Ethical and Religious Directives, 13.

7. Ethical and Religious Directives, 9.

8. Lynn Damiano Pearson, “Factsheet: Trump’s Recission of Protected Areas Policies Undermines Safety for All,” National Immigration Law Center, February 26, 2025, https://www.nilc.org/resources/factsheet-trumpsrescission-of-protected-areas-policies-underminessafety-for-all.

9. Shannon Schumacher et al., “KFF Survey of Immigrants: Views and Experiences in the Early Days of President Trump’s Second Term,” KFF, May 8, 2025, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/ poll-finding/kff-survey-of-immigrants-views-andexperiences-in-the-early-days-of-president-trumpssecond-term/.

10. Abigail S. Friedman and Atheendar S. Venkataramani, “Chilling Effects: U.S. Immigration Enforcement and Health Care Seeking Among Hispanic Adults,” Health Affairs 40, no. 7 (2021): https://doi.org/10.1377/ hlthaff.2020.02356.

11. Jeffrey D. Robinson and John Heritage, “Physicians’ Opening Questions and Patients’ Satisfaction,” Patient Education and Counseling 60, no. 3 (2006): 279-285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.009.

12. Peter Hancock, “Illinois on Track to End Health Coverage Program for Immigrant Adults,” WTTW News, May 14, 2025, https://news.wttw.com/2025/05/14/illinoistrack-end-health-coverage-program-immigrant-adults.

13. “The Model Policy,” Illinois Alliance for Welcoming Health Care, https://www.ilalliancehealth.org/policies.

14. “Our Toolkit,” Doctors for Immigrants, https:// doctorsforimmigrants.com/ourwork/#ourtoolkit.

15. “Treating Fear: Sanctuary Doctoring,” Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, https://www.luc.edu/stritch/bioethics/ medicaleducation/sanctuarydoctor/.

16. “Advocacy: Immigration,” Catholic Health Association of the United States, https://www. chausa.org/advocacy/issues/immigration.

HEALTH CARE ACROSS AMERICA

ROBIN ROENKER Contributor to Health Progress

Roughly 1 in 5 Americans — more than 60 million in all — live in rural areas across the country. For these residents of rural ZIP codes, locating accessible health care can feel like an uphill battle.1

The striking provider disparity between urban and rural areas in America is one key reason why. While urban areas currently average 31 providers per 10,000 people, rural areas have just 13 per 10,000 residents. And while urban areas boast 263 specialists for every 100,000 individuals, rural areas have only 30 specialists available per 100,000 people, according to the National Rural Health Association.2

Across the country, Catholic hospital systems are working diligently to bridge this divide and provide greater health care access to residents of small towns and farm communities.

When it comes to maximizing rural health care delivery, “It’s really a theme of each patient getting the right care at the right place at the right time,” said Kevin Post, DO, chief medical officer for Avera Health. To pursue that mission, Avera has prioritized “keeping the patient at the center of focus, while leveraging innovative tools” to support rural health care providers, Post said.

Other systems, including SSM Health and Intermountain Health, are doing the same. Drawing on innovative telehealth applications, creative

staff recruitment initiatives and organizational models that optimize the reach of available staff and facilities, Catholic health systems strive to provide all patients with top-notch care, unhindered by community size.

Historically, rural residents have poorer health outcomes, on the whole, than those who live in urban areas. 3 Death rates from heart disease, cancer, stroke and respiratory disease tend to be higher in rural areas,4 leading to a life expectancy for rural residents that’s roughly 2.5 years lower than their urban counterparts — a gap that continues to widen.5 These outcomes are tied to a myriad of health determinants, from smoking rates and obesity rates to residents’ access to nutritious food, health insurance and accessible health care, among other factors.

Hospital administrators said tackling this rural-urban disparity will require a multipronged approach, with telehealth programming serving as a powerful tool to help level the health care playing field.

Beginning with telehealth programming for critical care in 2014, Intermountain Health has grown its telehealth services footprint to include 105 programs, including telestroke, telehospitalist, teleoncology, telechaplaincy and telecrisis (behavioral health) services. The telehealth programs serve Intermountain Health’s entire 33-hospital footprint, including five Catholic hospitals across Montana and Colorado, as well as 43 hospitals outside of the Intermountain Health system that receive services on a contract basis.

“Through telehealth, we can bring specialty care to the patients, instead of bringing the patient to specialty care,” said John Williams, Intermountain Health’s assistant vice president of telehealth services. Having access to specialists via telemedicine reduces travel time for patients, allowing them to receive expert care in smaller, local, critical access hospitals, which frequently do not have specialists, like neurologists, on staff.6

“If we have a patient who walks into the emergency room who is suspected of having a stroke, staff will call our command center to be immediately connected with our telestroke team,” Williams said. “Typically, in under three minutes, [the remote specialists] are able to see that patient, and they’re able to run through their assessments, using video technology, to work with the local physician or local APP [advanced practice provider], depending on how that hospital is staffed, to help develop a care plan for that patient.”

“Our patients [in rural hospital settings] will see local, advanced practice providers, while getting remote access to specialists — perhaps back in Sioux Falls — so they really feel like they’re getting cared for by a team,” Post said.

Operating 23 hospitals across Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma and Wisconsin, SSM Health, too, is “leaning heavily into telehealth to see how we can better open up care access for our patients,” said Stephanie Duggan, MD, the system’s chief clinical officer. She notes that SSM Health’s adoption of specialty services using telehealth — including stroke services — is well integrated across their network. Their next goal: integrating primary care using telehealth just as effectively, drawing on a regional service model.

“We need to lean into [telehealth] resources in a different way,” she said. “Telehealth can feel a bit impersonal, but if we can develop a regional telehealth center [where patients see the same, regionally based primary care providers] … we can help patients gain greater trust and confidence in the person on the other end of that camera.”

Like many systems, SSM Health, Intermountain Health and Avera Health also use telehealth services paired with remote monitoring technology as a prevention tool. These programs provide real-time biofeedback for patients at risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes or even prepartum7 or postpartum complications. This allows providers to identify and address possible red flags before symptoms progress to critical levels.

“Through telehealth, we can bring specialty care to the patients, instead of bringing the patient to specialty care.”

— JOHN WILLIAMS

Systems generally transfer patients to tertiary sites if a higher acuity of care or an ancillary service is needed to maintain quality and safety of care.

At Avera — where 37 hospitals serve a footprint of 72,000 square miles across South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa and Minnesota — a similar approach uses telehealth to deliver specialty services, like cardiac or oncology care, to rural facilities without those specialists on staff. “Telehealth services allow us to leverage our care team to the top of license,” said Post, noting that 90% of Avera’s hospitals are critical access facilities with 25 or fewer beds.

From a health care provider’s perspective, having the support of telehealth services can, in some cases, lessen the challenges of accepting a post in a rural area, where staffing can be stretched thin. Avera is among the systems that have found success, for example, in implementing an artificial intelligence-supported virtual nursing program that lets remote, central hub teams use in-room cameras to monitor patient fall or bed sore risk, reconcile medications and do other routine tasks.8 This addition of “virtual eyes on beds” helps free on-site nurses to focus their expertise on other, high-level responsibilities, Post said.

Additionally, Intermountain Health found that hospitals using its nighttime telehospitalist services discovered it’s now easier to retain staff, Williams said. “Because this service allows us to

handle admit orders overnight virtually, on-site physicians no longer have to be on call 24/7. It allows the on-site teams to refresh and have some time with their families. As a result, these communities are able to recruit and retain physicians much more successfully.”

Recruiting and retaining staff is a critical concern at rural hospitals and clinics, as it is everywhere in health care.

Administrators at SSM Health, Intermountain Health and Avera Health agreed that building a pipeline of rural care providers remains a key focus. Each system is developing specific outreach programming to address ongoing staffing needs.

“We have to have people see rural medicine in a different light,” Duggan said, pointing to the power of offering on-site, rural shadowing opportunities for young physicians. “It’s about showing [them] how vital and what an important role and a difference one can make by being a part of

a smaller community,” she said. “Often that is enough for them to say, ‘Hey, maybe I could see myself living in a more rural community, even though I didn’t grow up there.’”

For some providers, the rural setting is a real draw. SSM Health’s two southern Illinois hospitals, St. Mary’s Hospital in Centralia and Good Samaritan Hospital in Mount Vernon, for instance, have found notable success recruiting locally. Partnering with area community colleges, the hospitals offer a nursing extern program that allows current nursing students to gain hands-on training while still in school. To date, roughly 85% of program participants have gone on to accept full-time SSM Health nursing positions in either Centralia or Mount Vernon. The hospital system hopes to expand the program soon to include other modalities, including respiratory therapy.

SSM Health also actively works to build partnerships with area high schools, sending representatives to career days and health class presentations, all with the hope of attracting local stu-

dents to the diverse array of health careers at an earlier age.

“We’re having to get more creative to build our own [workforce] pipelines,” said Damon Harbison, president at both SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital — Centralia and Good Samaritan Hospital. “While we of course welcome outsiders, what we have found is that when you’re able to attract locals who already have staked their claim to the area, so to speak, you’re going to have more success in retention.”

For its part, Avera has found traction in attracting and retaining nurses through internships and an innovative internal travel nurse recruitment program. This program offers high-paid travel placements limited to 13 Avera sites across three states.

“It’s a win-win,” Post said. “Participating nurses get the benefit of a higher compensation rate, but with the security of having employment by a health system. Meanwhile, from a system perspective, we’re getting the benefit of placing our own team members who can move seamlessly between sites because they’re comfortable with our care protocols.”

Since 2005, 112 hospitals serving rural counties across the country have closed completely. During the same period, another 84 rural-serving hospitals converted to non-acute or non-inpatient care, according to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research.9

In the last five years, more than 100 rural labor and delivery units have closed across the U.S. Today, fewer than half of America’s rural hospitals offer maternity services.10

These closures offer glimpses of what could become a growing trend. Already, roughly 44% of rural hospitals in America are operating with negative margins, according to KFF (formerly the Kaiser Family Foundation).11

As hospital system margins become further squeezed by health cost escalations and dwindling reimbursements, rural systems, especially, will need to continue making careful decisions regarding where and how best to deliver care to maximize efficiencies, leaders said.

Service delivery challenges may become even more difficult after the passage in July of HR-1, better known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Those who opposed this legislation fear that reductions

in Medicaid and Medicare funding could lead to the shuttering of many rural care facilities.

Just after the bill’s passage, Ascension posted a statement from its president, Eduardo Conrado, noting that the impending cuts “risk destabilizing the health care system, especially in rural and underserved areas.”12

While the newly signed legislation does include $50 billion in federal funding for a new “rural health transformation program,” that figure represents only slightly more than one-third of the estimated loss of federal Medicaid funding in rural areas, according to KFF.13

While some details of the fund’s allocation remain unclear, it’s expected that half will be distributed equally across all 50 states, with CMS retaining discretion regarding allocation of the remaining $25 billion.14

In times when there’s a challenging operational climate, rural systems will be forced to rethink their delivery approach, Harbison said.

“Twenty-five or 30 years ago, every community hospital was trying to offer every service they possibly could. Those times are over,” he said. “With the impending reimbursement cuts, there will be a lot of boardroom discussions about the need to potentially close services or consolidate or close hospitals.”

In navigating those decisions, SSM Health will focus on how best to deliver the precise, tailored services each community needs, Harbison said. To identify those services, the system already leverages a multistep approach, including patient surveys, dialogues with providers, and formal community needs assessments.

SSM Health also plans to continue building partnerships with community agencies and even competing health systems to ensure health services remain available in small market areas.

“If we can help patients by doing something together, then that’s the right thing to do,” Harbison said.

At Avera, care delivery optimization plans include ramping up core care services at its regional hospitals, so patients in very remote areas can still access critical care within, say, a two-hour drive rather than needing to travel four or more hours to an urban, tertiary site, Post said.

Avera also plans to remain laser-focused on meeting community service needs and developing local partnerships to address rural citizens’ food, housing and transportation insecurities.

Additionally, across the country, many small

hospitals have found success working with larger regional hospitals — as either managed or affiliate partners — to leverage efficiencies in supply chain management, regulatory protocols and other top-level administrative demands.

These partnerships have led to substantial cost savings and operational advantages for participants in Illinois, said Harbison, who serves as president of SSM Health’s Southern Illinois rural health network.

“Over the last several years, we have worked with smaller hospitals in the area to … build relationships to ensure that everyone is working at the top of their scope to help their communities,” Harbison said.

“I think we are going to see this more and more, that [community] hospitals are going to partner up with bigger systems” to operate successfully, Harbison added. “There’s a sense that we don’t need to be operating in silos. People are realizing there’s power in working as a system to create a [best practice] playbook for rural health.”

Finally, health care providers must continue assessing the quality of their care delivery through the lens of patient experience. At every turn, health care leaders said, their goal is to provide streamlined, accessible, top-notch care, regardless of an area’s population size.

“I think one of the most important things we can do,” SSM Health’s Duggan said, “is to lean into available technology, standardizing where it makes sense, so our patients have a consistent, quality care experience.”

ROBIN ROENKER is a freelance writer based in Lexington, Kentucky. She has more than 15 years of experience reporting on health and wellness, higher education and business trends.

1. “How We Define Rural,” Health Resources & Services Administration, February 2025, https://www.hrsa.gov/ rural-health/about-us/what-is-rural.

2. “About Rural Health Care,” NRHA, https://www. ruralhealth.us/about-us/about-rural-health-care.

3. Kendal Orgera, Siena Senn, and Atul Grover, “Rethinking Rural Health,” AAMC, September 27, 2023, https:// www.aamc.org/advocacy-policy/rethinking-rural-health.

4. Sally C. Curtin and Merianne Rose Spencer, “Trends in Death Rates in Urban and Rural Areas: United States, 1999-2019,” NCHS Data Brief, no. 417 (2021): https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:109049; Macarena C.

Garcia et al., “Preventable Premature Deaths from the Five Leading Causes of Death in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties, United States, 2010-2022,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries 73, no. 2 (May 2, 2024): http://dx.doi.org/ 10.15585/mmwr.ss7302a1.

5. Jaime Aron, “What’s Health Care Like in Rural America? We’re Taking a Close-Up Look,” American Heart Association News, April 30, 2024, https://www.heart. org/en/news/2024/04/30/whats-health-care-like-inrural-america-were-taking-a-close-up-look; Jack M. Chapel, Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, and Bryan Tysinger, “The Urban-Rural Gap in Older Americans’ Healthy Life Expectancy,” The Journal of Rural Health 41 (2025), https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12875.

6. “Critical Access Hospitals,” Rural Health Information Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/ critical-access-hospitals.

7. Julie Minda, “Avera Health Uses Remote Monitoring to Improve Health Outcomes for New Moms in Eastern South Dakota,” Catholic Health World, June 2025, https://www.chausa.org/news-and-publications/ publications/catholic-health-world/archives/june-2025/ avera-health-uses-remote-monitoring-to-improvehealth-outcomes-for-new-moms-in-eastern-southdakota.

8. “Avera Expands Telemedicine Efforts to Virtual Nursing,” Avera, Balance (blog), December 12, 2023, https://www.avera.org/balance/family-medicine/ avera-expands-telemedicine-efforts-to-virtual-nursing/.

9. “Rural Hospital Closures,” Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, https://www. shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/ rural-hospital-closures/.

10. “Stopping the Loss of Rural Maternity Care,” Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform, June 2025, https://chqpr.org/downloads/Rural_Maternity_Care_ Crisis.pdf.

11. Zachary Levinson and Tricia Neuman, “A Closer Look at the $50 Billion Rural Health Fund in the New Reconciliation Law,” KFF, July 24, 2025, https://www.kff.org/ medicaid/issue-brief/a-closer-look-at-the-50-billionrural-health-fund-in-the-new-reconciliation-law/.

12. Eduardo Conrado, “Statement on Medicaid and ACA Cuts in Newly Passed Legislation,” Ascension, July 3, 2025, https://about.ascension.org/news/2025/07/ statement-on-medicaid-and-aca-cuts-in-newly-passedlegislation.

13. Levinson and Neuman, “A Closer Look at the $50 Billion Rural Health Fund.”

14. Levinson and Neuman, “A Closer Look at the $50 Billion Rural Health Fund.”

SARA VAEZY, MHA, MPH Chief Transformation Officer, Providence St. Joseph Health

At Providence, our commitment to delivering high-quality, mission-driven care guides us in everything we do, including leveraging technology solutions. To help give time back for what matters most — patient care and human connection — we’re investing in artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled tools designed to streamline workflows and simplify day-to-day processes.

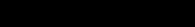

In our 2030 strategic plan, we are focused on making Providence the best place to give and receive care, as we create a delivery model for the future supported by innovation and positive change. Our five-year road map is anchored in three strategic pillars: be the best place to give and receive care, create the delivery model of the future, and drive focused innovation for positive change.

Using technology as a tool to transform and improve the patient and caregiver experience enables all three strategic pillars. At Providence, all our employees are called caregivers, recognizing that each of us plays a part in caring for patients and each other.

Pertaining to patient care, Providence is focused on patient experience and has established three focus areas to help our patients navigate their care: making it frictionless, personalized and navigable. Frictionless means making it easier for people to find and use our services. For example, we aim to ensure that all schedulable appoint -

ments have the option of being booked online. While that option is currently not exercised at each location, we know that, as a system, we seek to have everyone operating from the same data. Whether an appointment is made by phone or online, we help patients get the most information about where to get care.

We’re also focused on the personalization of care. We serve 5 million patients annually in our seven-state footprint. Each patient is different, with different needs, motivations and expectations of the services they are using. We connect with patients in a way that keeps them engaged.

Finally, when it comes to navigation, patients want to be able to navigate getting and receiving health care the way they are used to doing things in real life, just as they do with online shopping and banking. We focus on web, mobile and call center experiences to make it easy for our patients to get care. Navigation means being able to easily get into the right care at the right time, find the information you need, and get the job done (for example, booking an appointment) as a patient with minimal effort.

Providence Considers Health Care Trends as It Determines How Best To Use AI

Ongoing uncertainty and volatility in government

Changing supply and demand/ economic trends

Distribution, decentralization and emergence of ecosystems

Ongoing workforce challenges and competition for workforce

Digital enablement of consumer experience

Consolidating ambulatory environments

The rise of the “payvider”

A new flavor of health system mergers and acquisitions

Growing focus on diversification

Artificial intelligence adoption and data emerging as differentiators

Providence leaders gather data and forecasts as they plan for the future. They begin with a foundational understanding of the provision of health care as a public good, and examine the impact of the overall geopolitical landscape, the nature of supply and demand, workforce concerns, anticipated changes in reimbursement, and shifting market dynamics, such as the rise of the payvider, which is an entity that provides both insurance and care delivery services.

On the clinical side, we are focused on using AI technology to give our providers more quality time with our patients through what we call “sacred encounters.” For instance, an overwhelming number of messages that patients submit through their patient portal take a lot of clinician time away from direct patient interaction because care teams must respond to messages. Providence clinicians receive about 7 million patient-generated messages annually, and responding to these messages is a source of clinician burnout and fatigue.

We are taking a multipronged approach to this problem: by reducing the number of patientgenerated messages by providing direct patient access to the information they need or the task they’re trying to complete; by triaging messages to the right member of the care team; and by helping clinicians efficiently respond to messages.

All this said, AI within the health care realm is complicated and requires oversight, governance and guardrails. We’ve put in place key initiatives to ensure that we keep patients and caregivers safe and set ourselves up for success.

There are two key bodies of work happening at Providence, each composed of multiple initiatives. The first is our internal AI work groups. The Clinical AI Work Group is a dedicated multidisciplinary team led by clinicians who provide oversight, feedback and guidance around priority work areas for clinically oriented AI. The second work group is our Enterprise AI Guardrails Work Group. With so many AI-based solution implementations in flight, Providence leaders need visibility into these projects to provide guidance. This group evaluates AI solutions for safety, equity, risk, legal, compliance,

ethics and privacy guardrails. The team implements a governance structure to prioritize, safeguard patient data, prevent bias and ensure access to innovations for all, including underserved populations.

The other body of work is the Office of Transformation. The office aims to create a multidisciplinary and cross-functional approach that brings together technology, operations, clinical and financial aspects to drive large-scale changes throughout our system. There are two workstreams built into the Office of Transformation: current initiatives and future initiatives.

Current efforts this year are focused on reducing clinical administrative burden through clinician-facing documentation and charting support with ambient solutions, and supporting the

reduction and response to in-basket messages. These tools can save clinicians time during and after care. The tools also allow providers to spend more meaningful time with patients and still wrap up their day at a reasonable hour.

One guiding principle is that we are not going to automate what isn’t working — it is not substitutive. We will do things better and think about these issues more materially. Our future initiatives include workflow automation and new models of care delivery through virtual and asynchronous care. All will incorporate AI solutions as part of the process. When done right, AI is going to help our patients and caregivers.

SARA VAEZY is chief transformation officer for Providence St. Joseph Health in Seattle.

1. As you think about how Providence St. Joseph is working to ensure patient experiences that are frictionless, personalized and navigable, what struck you about the way the system is involving technology and artificial intelligence (AI) in their processes? What interested you most about the approach?

2. Does your organization have internal work groups similar to those this system is using? What aspects of creating groups like a Clinical AI Work Group and an Enterprise AI Guardrails Work Group appealed to you?

3. In Catholic health care, keeping humanity at the center of care is foundational to the work. What can you contribute to your organization’s understanding of the use of AI, whether it’s a perspective on mission, ethics, clinical, all of these, or your own distinct perspective? What are some ways to discuss these evolving issues and how they are implemented where you provide care?

4. How might Catholic social teaching, organizational ethics and bioethics inform the appropriate design, implementation and use of AI in health care?

KELLY BILODEAU Contributor to Health Progress

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are reshaping American health care, cutting billions in costs and improving patient outcomes through a patient-centered, preventive approach. Despite these successes, ACOs are facing growing challenges, prompting calls for reform to help these models achieve their full potential.

The money saved by ACOs often comes from seemingly small changes in clinical practice that can yield outsized benefits. An example comes from Hospital Sisters Health System (HSHS), which launched its ACO in 2015 in central and southern Illinois. At the time, doctors rarely screened for depression during visits, even though the condition puts a substantial clinical and financial burden on both the patient and the health care system.

Experience and research show that patients with untreated depression have high use of acute care services, and that is costly, especially when the underlying condition isn’t addressed, explained Dr. Leanne M. Yanni, president and CEO of Illinois Physician Enterprise for HSHS.

The organization wanted to do more for patients to respond to this “common mental health condition that needs both screening and timely treatment,” she said.

As part of the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), a value-based ACO model established by the Affordable Care Act and implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2012, the organization made depression screening a priority. As a result,

screening rates increased from 2 in every 10 patients to near universal levels, leading to more prompt treatments and better patient outcomes, Yanni said.

ACOs, like this one, have shifted away from a fee-for-service model toward a coordinated, preventive care approach that targets chronic conditions and social and behavioral determinants. The approach is producing tangible benefits. In 2023, the MSSP ACOs generated more than $3 billion in total earned shared savings, according to CMS.1

“The story of ACOs has been a very positive story, about growth, savings, improved clinical outcomes, better care, better health, lower cost,” said Emily Brower, president and CEO of the National Association of ACOs (NAACOS), which advocates for health care members of these organizations. “They’ve been incredibly successful.”

While they’ve shown broad improvements overall, ACOs are not equal, said Rob Saunders, PhD, senior research director for health care transformation at the Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy. “There are ACOs out there that have done amazing things and have really bought in, and their leadership is on board,” he said. Other ACOs have struggled. They may have conflicting

incentives, limited capital for making upfront investments, or their leadership is managing multiple priorities, he explained. “Not surprisingly, their results are often underwhelming.”

Spotty commitment isn’t the only issue affecting ACO performance. NAACOS and other advocates say that more than a decade into the ACO era, structural challenges with models, including the MSSP, are hindering progress. NAACOS is now advocating for revised reimbursement structures that better reward high performers and reduce administrative burdens. They also seek to create incentives to encourage organizations that are still sitting on the sidelines to engage in these value-based initiatives. Nearly 90% of 168 health care professionals in a recent NAACOS survey cited financial risk as a primary barrier to valuebased care.2

“We’ve produced enough evidence that these models are good for patients and providers. Let’s keep going and keep making it better,” Brower said. “Nobody wants to revert to fee-for-service because there’s not enough opportunity, or for organizations to drop out of ACOs because of the heavy administrative or regulatory burden.”

ACO models come in many different forms. Medicare’s MSSP was the first major driver for ACO adoption, although there were some earlier predecessors, Saunders said. Today, it’s one of several federal ACO models, including CMS Innovation Center models such as ACO Reach, ACO Primary Care Flex Model and the Enhancing Oncology

which now cover more than half of Medicare beneficiaries, are also driving value-based care, but do it by using capitated payments for each patient, rather than the ACO shared savings approach. 5 (Capitated payments are fixed, prearranged payments per patient.)

There are also commercial ACOs, coordinated by insurers such as Aetna, UnitedHealthcare and Cigna, which were once smaller than federal programs, but have grown rapidly and now rival or exceed Medicare ACOs in size, Saunders said. In 2022, approximately 45% of doctors participated in commercial ACOs, compared to about 38% in Medicare ACOs, according to the American Medical Association.6

Shared savings models vary in the amount of financial risk they place on ACOs. Some offer upside-only arrangements, where organizations only get a share of savings and no penalty for losses. Others, such as the MSSP Enhanced track, offer the opportunity to earn more from shared savings, but the program can also cost them more in losses.

Since they began, ACOs have achieved a 2% to 3% improvement in overall cost trends. While these percentages may sound slight, the reductions are in relation to trillions in expenditures, Duke’s Saunders said.

St. Louis-based Mercy has seen successes through its participation in the Enhanced track of CMS’s MSSP, the higher-risk and reward model. “Over the last five years, we’ve managed the total cost of care at 6% to 8% [it varies by year] lower than our peers in our given markets and our given communities,” said Dave Thompson, senior vice president, chief growth officer and president of population health at Mercy.

Organizations often need to invest in changes for three to five years before their efforts pay off, Saunders said. “You can’t just start an accountable care organization tomorrow and suddenly be able to improve quality and reduce costs,”

he said. “It

takes time.”

Model, among others.3 More than half of Medicare beneficiaries are now aligned in an accountable care relationship with a provider, according to CMS.4 In addition, Medicare Advantage plans,

In contrast to high-performing organizations like Mercy, many struggle to achieve results. Nearly 40% of Medicare ACOs made no savings or incurred losses, according to a report from Arcadia CareJourney.7

Organizations often need to invest in changes for three to five years before their efforts pay off, Saunders said. “You can’t just start an accountable care organization tomorrow and suddenly be able to improve quality and

reduce costs,” he said. “It takes time.”

Comparing results from federal and commercial programs is difficult because commercial programs rarely release public data and because of program variability. This variability also presents a challenge for organizations trying to participate across multiple programs, Saunders said.

While data isn’t available on all ACOs, a Congressional Budget Office report identified performance trends across Medicare programs. Those that do the best are those run by physician groups or have a larger proportion of primary care providers, and those who initially invested more in the programs than the regional average.8

It’s not surprising that physician-led ACOs tend to outperform hospital-led models because it’s often an apples-to-oranges comparison, Saunders said. Hospitals, which tend to be larger organizations with a lot of infrastructure, may face difficulties if they try to quickly change things like their workflows, processes and structures, he explained.