It's tough delivering maternal care in rural areas.

Will federal cuts prompt more hospitals to close OB units?

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Dr. Paul Berndt enjoys looking around the field at his son’s T-ball practices in Parkston, South Dakota, and seeing how many players he delivered.

“In a small town, it gets to be a pretty small little network,” said Berndt, an obstetrician and family practitioner.

The population of Parkston is just over 1,500 people and Avera St. Benedict Health Center, where Berndt practices, sees about 60 deliveries a year. Berndt says the residents of Parkston are grateful for his services and trust Avera St. Benedict for their care.

Mercy nurses test new technology that makes their jobs easier

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

When Tracy Breece and Cheryl Denison and a team of nurse leaders visit Mercy hospitals to see how technology is helping or hindering nurses, the nurses track them down.

“They’re like, ‘Oh, she’s here. Are you getting all of my feedback?’” said Breece. “They understand that feedback loop is important, and they’re eager to share.”

Breece, executive director of nursing informatics, and Denison, nursing systems engineer, are leading Mercy’s Project ANEW, which stands for Advancing Nursing

No One Dies Alone volunteers provide ‘compassionate presence’ in last hours

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Sometimes, a dying person doesn’t have a family. Other times, they’re estranged. Sometimes, a dying person’s family lives across the country and can’t be at their side. Other times, the family simply can’t handle being there.

No One Dies Alone volunteers don’t care about why. If a dying patient is alone, they want to be there.

“We’re trying to bring as much compassion and love to that circumstance that we can, and that’s the most we can offer,” said Shawn Kiley, chief mission integration officer and executive sponsor of the No One Dies Alone program at Providence

Continued on 9

Providence initiative leads to dramatic rise in goals-of-care conversations

By LISA EISENHAUER

When Providence St. Joseph Health began documenting goals-of-care conversations for adults in intensive care units in 2016, the total was 555, or 6.8% of the patients. By last year, the number hit 8,533, or 84.8% of patients who were in one of the system’s 45 ICUs for at least five days.

In the intervening years, Providence launched, fine-tuned and expanded systemwide training for clinicians on how to hold the conversations and simplified

Continued on 5

Tour immerses new physicians into community around CHRISTUS hospital

By JULIE MINDA

Even though Dr. Jasmine Thomas grew up in East Texas and completed a student rotation in Longview during medical school, it wasn’t until a recent bus tour that she got an up-close perspective on what life is like for marginalized members of the Longview community.

She is one of 13 physicians who in late June started their internal medicine residency at CHRISTUS Good Shepherd Medical Center — Longview with a bus tour of the community they’ll be serving for the next three years. On the tour, Dr. Tiffany Egbe of Good Shepherd described the area. The group stopped at two Longview nonprofits that serve vulnerable people. The physicians got to talk with leaders and Continued on 8

Virtual care model

As Trinity Health was creating TogetherTeam Virtual Connected Care, which adds virtual nurses to the bedside care team, it was intentional about maintaining the sacred aspect of Catholic health care.

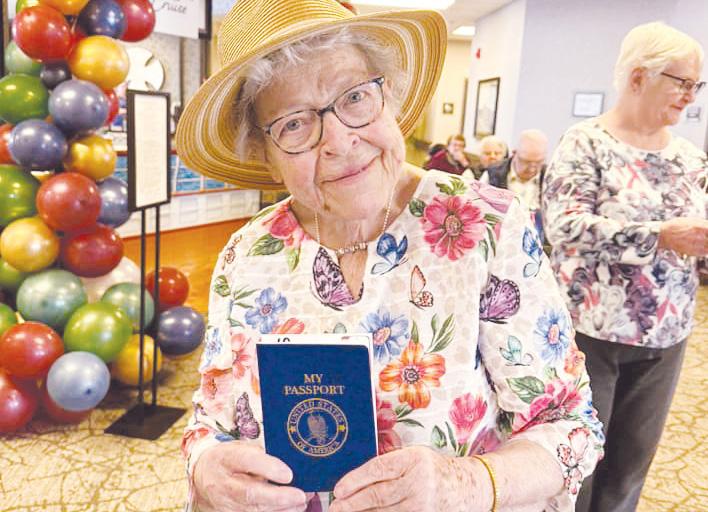

Creative activities

With innovative activities such as virtual cruises, college courses and sip-and-paint gatherings, Catholic long-term care communities stretch their imaginations to keep residents engaged.

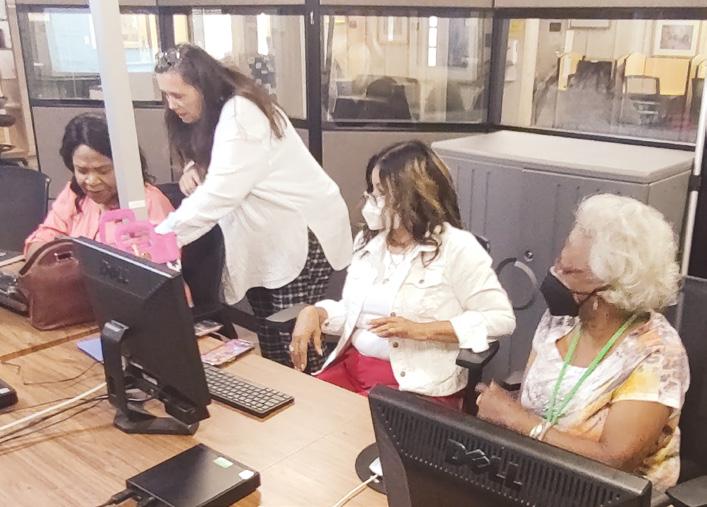

Adding resources

St. Joseph's/Candler resource center in Savannah, Georgia, helps people get health information and address the social determinants of health. Now it is increasing its focus on chronic disease management.

Surgeon performs nation’s first robotic heart transplant at Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center in Houston

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Dr. Kenneth Liao knew his patient, Tony Ibarra, was getting sicker. The 45-year-old had been in the intensive care unit at Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center in Houston for months, waiting for a heart transplant.

Meanwhile, Liao and his team had been performing heart surgeries using surgical robots, often three a day and in total more than 800, over the last six years.

Last year, they started planning how they might perform a robotic heart transplant to remove a diseased heart and replace it with a new one without splitting open the breastbone.

Liao presented the idea of having such a surgery to Ibarra, who was willing. In early March, Liao and his team performed the operation, the first fully robotic heart transplant in the United States. Liao’s team is the second to transplant a heart with surgical robots. In September 2024, a team at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, completed a fully robotic heart transplant on a 16-yearold boy.

“(What) I always tell my colleagues or the students, is that this happens, and you need two things: surgical expertise and the technology,” said Liao. “And (when) these two things converge, then some miracle will happen. That’s exactly what happened in this case.”

Liao is a professor and chief of cardiothoracic transplantation and circulatory support at Baylor College of Medicine and chief of cardiothoracic transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at Baylor St. Luke’s. The medical center is part of St. Luke’s Health, a subsystem of CommonSpirit Health.

Aligning circumstances

Ibarra had a history of heart failure after suffering a stroke. In November, he was admitted to the hospital as his condition worsened. He was on mechanical support devices for months in the ICU, waiting for a transplant.

Because he had been bedridden for so long, it would take longer to recover from a traditional heart transplant and he would be prone to infection. That made him a good candidate for the relatively gentler robotic approach, Liao said.

In March, a local heart became available for transplant and the surgical team was given more than 24 hours’ notice, which gave them time to prepare.

Liao said the surgical robot is like a natural extension of his hands. He and his team had plenty of practice with it and were “doing parts of the heart transplant surgery every day,” he said.

He added: “The historical part is that the robotic heart transplant is a little complex, because we put all the other robotic procedures together into one.”

Precise work

In a traditional transplant, surgeons cut through the sternum, which leads to a longer recovery time and higher possibility of complications. Using the surgical robot, Liao’s team cut a five-inch incision above the navel and snipped the cartilage at the tip of the breastbone to get behind the sternum. They then opened the preperitoneal space in the abdomen to reach the diseased heart.

After the team removed the old heart, they inserted the new one through the same abdominal space. They made three smaller incisions in the chest for other robotic arms necessary for the surgery. The approach helped prevent excessive bleeding and the need for blood transfusions.

The team could have changed course during the surgery and transplanted the heart the traditional way if needed, Liao said. “This robotic surgery didn’t have any potential harm to the patient,” he said. “That’s the beauty of this. Everything we do is to the best benefit of the patient.”

After the surgery, Ibarra recovered in the hospital for a month. Doctors monitored him closely for three months after his release. He doesn’t need to be checked for another year, Liao said.

“I can’t believe I’m alive,” Ibarra said in

an interview with Houston television station KHOU. “I always had God, so it came out good.”

Another historic moment

Liao called the transplant a historic moment but a natural progression in the field of heart surgery. He pointed out other historic moments, such as the first humanto-human heart transplant in South Africa in 1967, and the implantation of a new type of artificial heart in a patient last year at Baylor St. Luke’s. He added that other surgeons will innovate and perform robotic transplant surgery in new and slightly different ways.

Liao is already responding to texts and emails inviting him to conferences to tell others about the operation and he will teach others at Baylor St. Luke’s his technique.

This aligns with the mission of the hospital’s care providers to help others, he said, and to take a humble approach to their work.

“You work in this hospital, and then you do everything to help the people, and then you advance the technology to help the people. You transform the health care,” he said. “And then that’s it. That’s all we do.”

vhahn@chausa.org

Health World (ISSN 87564068) is published monthly and copyrighted © by the Catholic Health Association of the United States. POSTMASTER: Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to CHA Service Center, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone: 800-230-7823; email: servicecenter@ chausa.org. Periodicals postage rate is paid at St. Louis and additional mailing offices. Annual subscription rates: CHA members free, others $29 and foreign $29.

Opinions, quotes and views appearing in Catholic Health World do not necessarily reflect those of CHA and do not represent an endorsement by CHA. Acceptance of advertising for publication does not constitute approval or endorsement by the publication or CHA. All advertising is subject to review before acceptance.

President

and Marketing Brian P. Reardon

Editor Lisa Eisenhauer leisenhauer@chausa.org 314-253-3437

Associate Editor Julie Minda jminda@chausa.org 314-253-3412

Associate Editor Valerie Schremp Hahn vhahn@chausa.org

CHA’s Faithfully Forward builds student awareness of ethics, mission careers

By JULIE MINDA

The forecast is certain: There are not enough candidates in the pipeline for positions at ministry facilities in ethics, mission, formation, and spiritual and pastoral care. One reason is that university students interested in these fields are not aware of the many opportunities available to them in Catholic health care.

CHA is working to address the issue through the newest phase of its Faithfully Forward initiative. The effort includes partnerships with Catholic universities offering degrees in the fields of concern to make faculty and students aware of the many roles available in Catholic health care and how to pursue them.

This effort is part of broader, ongoing work to head off severe shortages in these critical positions.

“It is becoming more and more difficult for Catholic health systems and facilities to find people with the right skill sets for these positions,” says Brian Kane, CHA senior director of ethics. “We are asking, ‘Can we influence universities in how they prepare students, and can we influence the universities in how they shape curriculum?’”

“It’s exciting that this new platform can help us engage a broader universe of people as we promote these vocations in a more effective way,” says Nathaniel Hibner, CHA’s other senior director of ethics.

Surveying the landscape

Based on member concern, CHA included an initiative in its 2018 to 2020 strategic plan to assist the ministry in talent development and succession planning in mission, pastoral care and ethics roles.

To better understand the issue, the association interviewed ministry sponsors, CEOs and mission leaders; surveyed CHA member systems; organized workgroups to study the problem; and convened an advisory committee. This work, dubbed Project Legacy, involved more than 100 CHA members and other experts.

The project revealed that top leadership throughout ministry systems and facilities view roles in mission, pastoral care and ethics as essential to Catholic identity. The work also found that leadership knew recruitment, formation and retention of staff in these roles is a priority. The leaders said there was a need to establish clearer

Palliative

Hibner, CHA senior director of ethics, presents at the

Health Care in March. A key area of focus for CHA’s

ethicist positions in the ministry.

standards for these mission and ethics roles and to improve compensation. They also said internships and fellowships in these areas were scarce.

Project Legacy led to CHA efforts beginning around 2019 called Faithfully Forward to address these priority areas. But when the association’s focus shifted to the pandemic starting in 2020, the work stalled.

COVID worsens outlook

Recently, CHA’s sponsorship and mission services department — which led the Project Legacy and initial Faithfully Forward work — refocused on the pipeline issue. Hibner says that, restudying the landscape, CHA has confirmed that not only is there still a critical need to increase the pipeline, but also that turnover in these roles during the pandemic has worsened the situation.

The emergence of new challenges has made the issue even more critical. Hibner explains that with health care systems and facilities facing increasingly complex issues and decisions, roles in mission and ethics are more important than ever. For instance, ethicists’ influence is needed as these organizations determine how to appropriately use artificial intelligence technology. So, Hibner says, the ministry needs more highly trained staff even as it struggles to meet current demand.

CHA also recognizes that the ministry needs more diversity in these roles so mis-

out to Catholic universities to make faculty and students more aware of career paths in ethics, mission, formation, and spiritual and pastoral care. The association is sharing informational materials, including this brochure.

sion leaders, ethicists, pastoral care leaders, chaplains and others better reflect the communities they serve.

University partnerships

Kane and Hibner recently led the development of this newest phase of Faithfully Forward and are heading its implementation. This has included identifying Catholic colleges and universities offering academic programs in mission, ethics and pastoral

care and serving a diverse population of students. Kane, Hibner and colleagues have been reaching out to these universities to discuss how best to connect with faculty and students.

Based on those conversations and meetings, they have developed materials in both print and digital formats that describe what leaders in mission, ethics, formation, and spiritual and pastoral care do in Catholic health care; why these roles are important; why there is such a need for new candidates; the benefits of pursuing these roles; and best ways to pursue them.

CHA has arranged for the university contacts to share the materials with students beginning this month. The materials contain a QR code that students can scan to learn more.

CHA will offer additional resources to help students learn more about role responsibilities as well as potential formation experiences.

Kane and Hibner say they welcome partnerships with more universities.

Clinical fellowships

Kane notes that these partnerships are just one avenue to address the pipeline issue.

Another major recent initiative has to do with establishing more fellowships and internships in ethics. This is to address a longtime concern that candidates for ethics jobs often do not have sufficient practical experience. CHA has joined with the Association of Bioethics Program Directors to form the Council on Program Accreditation for Clinical Ethicist Training. Within the past year, the council became a member of the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs. These moves pave the way for creating more practicums for aspiring ethicists.

Kane says CHA is supporting member systems and facilities in establishing more sites for fellowships, internships and similar programs.

All of this work is about getting more organizations on board to recruit and prepare the next generation of ethics and mission leaders. “We’re trying to identify organizations to advocate for these careers and to recruit these professionals we know we need in the ministry,” Hibner says.

This is the fifth article in a series on how CHA’s sponsorship and mission services department is reimagining its work.

jminda@chausa.org

care requires looking at all dimensions of what it is to be human, advocates say

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Thomas had undergone treatment for cancer in his head and neck. The 53-yearold was free of the disease, but still suffered dehydration, malnutrition and profound depression. An inpatient palliative care team with Providence St. Joseph Health saw him in the hospital, and when he was discharged, he was one of the first patients at a new outpatient palliative care clinic.

“This was clearly not an imminent, end-of-life situation,” said Dr. Gregg VandeKieft, a clinical ethicist and palliative care physician at Providence St. Peter Hospital in Olympia, Washington, speaking about his patient during a June 24 CHA webinar called “Whole Person Care and the End of Life: Uniting Community, Health, and Policy for Human Flourishing.”

After about a year of treatment at the clinic, Thomas came in one morning and said someone else could have his space on the clinic schedule. “I only came in today to say thank you,” he said. “You’ve utterly changed my life.”

That was in 2015. About six months ago, the cancer returned, and Thomas was readmitted to the hospital. In mid-June, he died while in hospice care.

“This is over 10 years after he was first seen by palliative care, and we were able to have a meaningful impact on his life, both upstream when he had years ahead, and also at the end of life, when it was time for him to have hospice care,” VandeKieft said.

VandeKieft spoke about the benefits of palliative care alongside Robert Vega, director of public policy, secretariat of prolife activities for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops; and Rebecca Freeman, the pastoral care ministry coordinator for the office of family life for the Diocese of Orange in Southern California. They pointed out that true whole-person palliative care requires addressing the physical, social, economic and spiritual needs of patients.

Defining palliative care

Vega quoted Pope Francis, who said palliative care “is above all a concrete sign of closeness and solidarity with our brothers

and sisters who are suffering” and a “genuine form of compassion” that responds to suffering.

He said that palliative care is a community approach, and the Catholic Church recommends palliative training in the educational and health sectors.

There are challenges to funding, personnel and awareness, he said. The USCCB and CHA have repeatedly endorsed The Palliative Care Hospice Education and Training Act, a bipartisan measure, which has stalled in Congress.

Sharing resources

Freeman said her experience with her father’s death led her into chaplaincy and then into her role as a diocese and statewide coordinator of the Whole Person Care Initiative, a collaboration of Catholic bishops and Catholic health systems in California. She encouraged participants to share resources, including ones from CHA, the USCCB’s Respect Life Store, and the Whole Person Care Initiative.

“As we were talking to the faithful, as

we’re talking to parishes, we found that, unfortunately, people just didn’t have a lot of information at all around this topic,” she said.

Freeman sees the steps to caring for the whole person as separate buckets: educating people and encouraging them to talk to loved ones about their wishes for end-oflife planning; building a network of partners at the diocesan, state and federal levels; and educating a parish community so they know what is available, especially the sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick.

Other groups also can fit into the network: The Emmaus Ministry for Grieving Parents; Catholic Aging, which provides support for loved ones of people with dementia; Project Rachel, for those grieving a loss of a child by abortion; and the National Association of Catholic Chaplains. VandeKieft, the palliative care physician, said quality-of-life care should look at emotional, social and spiritual needs and the whole person, “all the dimensions of what it means to be human.”

“Providing high-quality palliative care encompasses all those dimensions,” he said. vhahn@chausa.org

The Grey Nuns Thrift Shop in New Hampshire is popular spot to find support and a bargain

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

It was a freezing early spring day outside

The Grey Nuns Thrift Shop in Nashua, New Hampshire, when a woman wearing highheeled sandals walked up to Michele Canto.

The woman’s feet were bright apple red.

Canto was helping at the shop’s monthly Mission Meals & Medical event where the St. Joseph Hospital Mobile Health Clinic provides health checks and serves hot meals. Canto, the hospital’s director of community ministries, knew the shop could help with another immediate need.

“Your feet have got to be killing you,” Canto said to the woman.

“Well, I don’t have any other shoes,” the woman replied.

“Well, let’s go in and get you some shoes,” Canto said.

Canto found a pair of fur-lined L.L. Bean slip-ons. The woman teared up and thanked her. “I couldn’t even think of walking back home,” the woman said.

The Grey Nuns Thrift Shop has become more than a place to find a bargain. “The pride of our mission in the community is knowing that every day we all go home knowing that we’ve made a difference in at least one person’s journey,” Canto said.

Willing supporters

The shop has grown exponentially in recent years, partly because it moved to a more visible location on Main Street in 2021, and partly because of growing partnerships with other community agencies and groups. Not only can the public donate items and shop there, but the groups also provide vouchers to clients so they can choose items such as pots and pans, an outfit for a job interview, or a warm coat. The groups outline in the vouchers what is needed, including sizes for clothing. The store documents the value of the items and reports it monthly to its leadership team. Neither the agencies nor the clients have to pay for the items.

In 2024, the shop accepted 1,400 vouchers for a total of $41,400 in goods. It also gave 48 sleeping bags and 61 tents to people who are unhoused.

As of May, the shop had accepted 784 vouchers for $31,200 in items this year. It has given away 24 sleeping bags and 43 tents.

Canto looks for grant opportunities for the shop, speaks publicly about its mission, and serves as the bridge between the shop and senior hospital leadership.

“When people find out about what we do and how we do it, they are more than willing to hop on board and support us however they can,” she said.

Visibility and viability

The Sisters of Charity of Montreal, St. Joseph Hospital’s founders and an order also known as the Grey Nuns, opened the thrift shop in 1997. They wanted a place to support people in need in the community.

A watercolor painting of order foundress St. Marguerite d’Youville hangs in the shop. The painting sparks conversation (“My aunt was a Grey Nun!”) and helps tell the order’s story.

Around 2010, the Grey Nuns turned over the shop to the hospital, which is part of Covenant Health. Canto began overseeing the shop around 2015 and is responsible for putting together a team for daily operations. She didn’t know much about thrifting or vouchers, and the shop was lucky to make a couple hundred dollars in sales each month to help with rent, she said. Then the pandemic hit and the shop temporarily closed.

When it reopened, Canto started looking for a more visible location. She found one at 11 Main Street in the central part of Nashua, less than 2 miles from the hospital and near a neighborhood with stately Victorian homes that is often a rich source of donations.

“We get designer clothing with tags still on,” said shop manager Mary Deshaw. “I got a pair of pants one time that had a $798 price tag on it.”

She said most vintage items and antiques go to a designated area of the shop. Her seven employees and two dozen volunteers sort donations and stock and straighten the store, often focusing on departments that interest them, like books or linens. Often volunteers come in for the camaraderie on days they’re not scheduled to work, she said.

“Everybody works really hard to make it look like a boutique,” Deshaw said. “It’s really important to us to have it be a space that all of those people love and they know they’re going to get great deals and find unique things.

“But even more importantly, it’s a space where our voucher clients can come in and be treated with respect. All we ask back is that we get respect from them.”

A growing need

The thrift shop partners with 30 community agencies, such as Greater Nashua Mental Health, Nashua School District, and family social services agency Marguerite’s Place, that send clients to the shop with vouchers. Thrift shop staffers and volunteers sometimes direct clients to agencies for help if they are not connected already. St. Joseph Hospital also refers people to the thrift shop or uses it as a source of clothing for patients when they’re discharged.

Voucher clients shop for themselves and get the same service as any customer. “It’s very rewarding when people leave here

feeling better than they did when they came in,” Deshaw said.

Carol Weeks, the director of communications, events and volunteers for the Nashua Soup Kitchen & Shelter, said the organization has a long-standing relationship with St. Joseph Hospital. Hospital employees have served food at the soup kitchen. The shelter has given thrift shop vouchers to clients for about 10 years.

“It’s been working out really, really well,” she said. “We have had people go back to work because they’ve been able to get the correct attire or shoes or whatever through the thrift shop. We’re just so grateful that they’re willing to do that for us.”

Deshaw said the community is generous. This winter, during stretches of bitter temperatures, she put calls out on the shop’s Facebook page for warm blankets. Many of the donations that poured in were new.

Deshaw set the blankets out front with a “free” sign, and they disappeared quickly. “The response was incredible,” she said. “The community just comes through big time.”

Seeking support

Two years ago, the thrift shop organized what’s become an annual fashion show to raise money. The show helps spread the word about the shop. Deshaw also regularly posts items and stories on the shop’s Facebook page, which attracts new customers, including vintage resellers from Boston.

Deshaw said St. Joseph Hospital subsidizes the shop’s bills if needed.

She has advice to others who might run a similar, hospital-affiliated thrift shop: “Make as many connections as you can, because you’re going to make friends who are going to support you when you need it. You’ve got to put yourself out there.”

One woman who saw Deshaw’s plea on Facebook donated new blankets and gave her number to Deshaw. “Call me whenever you need help,” she said.

Recently, Deshaw did, and the woman brought new underwear and 15 backpacks, items clients needed but the shop didn’t have on hand.

Gratitude comes from unexpected places. A man who works at a recovery center that sends clients to the shop had talked to Deshaw off and on over the telephone. One day, he told her: “I just want you to know that I am three years sober, and you guys were huge in helping me to get where I am, because you treated me like a human being.”

He told Deshaw that the safety he felt and the respect he was shown on his visits to the shop helped him stay strong.

He added: “And now I work here, and I help people that are where I used to be.” vhahn@chausa.org

By JULIE MINDA

Ministry eldercare facilities have a mission — and requirement — to provide their residents with person-centered care that honors their dignity and meets their needs. These facilities also have a moral and legal obligation to respect the dignity of their staff members.

What happens when these two callings come into apparent conflict, such as if a resident requests that a staff member be reassigned because of that staff member’s race or sexual orientation?

During a CHA webinar in June, consultant Dawn Hawkins Johnson explained how ministry facilities can respond to such conflicts in a way that honors the dignity of both the resident and the targeted staff member.

“We need to ask, ‘Did we lead with compassion with staff and residents in this situation?’” said Johnson, who is president and CEO of the DHJ Services consultancy. The firm describes its mission as “to ensure that health policy and health care delivery are centered in equity that leads to improved health, quality and care.”

Patient and staff suffering

CHA offered this webinar in response to concerns expressed by members. The members said they wanted ideas on how to handle ethical issues that arise when there are differences between residents and staff.

Having the right infrastructure in place at long-term care sites can potentially head off such concerns, Johnson said. This includes policies, procedures and a culture that focus on quality of life and personcentered care for residents and comprehensive training and a safe and supportive environment for staff.

Johnson recommended prioritizing the 4Ms as promulgated through the Age-Friendly Health Systems movement: assessing what matters to a resident, what the person’s medication and mobility needs are and what their mentation is. Understanding a resident’s 4Ms at the outset and throughout their stay in a facility can help guide care plans and decisions. Attention to the 4Ms also can help identify and head off potential or actual conflicts between residents and staff arising from differences in their backgrounds.

Johnson said it is also important for staff to be well trained in working with a variety of residents and on how to interact with residents who may have a different background, language, cultural understanding and spiritual tradition than them. Staff also should be trained in trauma-informed approaches. Johnson called this comprehensive approach concordant care.

Cultural humility

Johnson said facilities should build an environment with cultural humility. Cultural humility is the practice of self-reflection and learning from others to honor their beliefs, customs and values. Johnson said facilities also should strive to have diverse, multilingual teams with staff who reflect the makeup of the resident population.

She noted that leadership must encourage collaboration and partnership among all staff and residents. “We need to build bridges,” she said, “and not put up walls.” jminda@chausa.org

Goals of care initiative

From page 1

the process to document patients’ goals of care within the electronic health record. Across Providence, the number of documented goals-of-care conversations for all adult nonobstetric patients in acute care increased from 8,296 out of 382,067 patients, or 2%, in 2017 to 102,066 out of 376,586 patients, or 27%, last year.

Dr. Matthew Gonzales, chief medical and operations officer at Providence’s Institute for Human Caring, has led the effort. He sees the goals-of-care conversations as essential to Providence’s mission, which includes the promise to “Know me, care for me, ease my way.”

“We can’t deliver on ‘care for me’ or ‘ease my way’ unless we actually know who people are,” Gonzales said. “And so, this feels like a fundamental first step in getting health care right.”

Gonzales stressed that the conversations are not about reducing the quality or intensity of care. “We’re not trying to say people should get less care, but we are trying to say that if you’re sick and in a hospital we should know what matters to you, and we should figure out how we can align the care that we provide to what you’re hoping for,” he explained.

Empathy and honesty

Gonzales is the lead author of “Successful Strategies for Operationalizing Goalsof-Care Documentation,” an article published in May in the New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst that details Providence’s initiative. Providence’s Institute for Human Caring has driven the effort. The institute is focused on improving the delivery of person-centered care systemwide.

“ We can’t deliver on ‘care for me’ or ‘ease my way’ unless we actually know who people are. And so, this feels like a fundamental first step in getting health care right.”

— Dr. Matthew Gonzales

In developing training for goals-of-care conversations, Gonzales said he and his colleagues were mindful that Providence caregivers would need to be equipped “with better skills to be able to respond with empathy and from a place of genuine honesty, as we talk about some really hard things sometimes.”

For the initiative, Providence adapted the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and

related training created by Ariadne Labs, a nonprofit health innovation center. The guide offers patient-tested language for caregivers to use when talking to patients about their goals and values.

Based on the guide, Providence’s goalsof-care conversations generally follow a series of milestones, including asking permission to discuss the topic, sharing the clinician’s understanding, eliciting the patient’s core values, and developing a shared plan for the future.

Instruction and role-playing

The training begins with instruction that includes why the conversations are important. (One reason: Data has shown they lead to better health care outcomes for patients and less anxiety and depression for families.) Gonzales at first presented that part of the training in-person at Providence hospitals. It is now in modules that clinicians can access online at their convenience.

The second part of the training is roleplaying, with clinicians taking turns as questioner, patient and observer. This part is done mostly virtually with a trainer included.

Gonzales said trainees are sometimes initially reluctant to role-play. They express embarrassment about performing or concern that the scenario is fake.

“What we found, though, in evaluations from the course, which we didn’t put in the paper, is that 98% of people thought the role-play was valuable and would want to do it again,” he said.

Over the years, 5,000 Providence caregivers have received the training. Meanwhile, the training has been condensed from about 2½ hours to about 1½ hours. Providence is now developing tools that use artificial intelligence to simulate the experience with a virtual patient and a virtual communication coach.

“There is recognition that even despite doing this in-person and doing this virtually with modules plus role-play, that ultimately we need to get to a more scalable, better solution,” Gonzales said.

Leadership, training, technology

The initiative began in 2016 with pilots at two hospitals. The pilots’ success prompted Providence to expand the effort systemwide and aim for documented goals-of-care conversations with 65% of adult ICU patients. By 2024, of the 45 Providence hospitals with ICUs, 38 hospitals exceeded the target and 20 hospitals surpassed 90%.

Gonzales credited the success of the initiative to several factors. One is support from Providence leaders, who prioritized and funded the effort.

Another is pivoting during the pilot phase from focusing the training on physicians to focusing it on nurses. Gonzales said the nurses quickly implemented the conversations and began discussing during rounds whether the talks had happened and been recorded, which led to a tremendous upswing.

Celebrating Extraordinary Contributions to the Catholic Health Ministry

TOMORROW’S LEADERS PROGRAM

Honoring young people who will guide our ministry in the future

LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

For a lifetime of contributions

SISTER CAROL KEEHAN AWARD

For boldly championing society’s most vulnerable

ACHIEVEMENT CITATION

For innovative programming that changes lives

NOMINATE AN EXCEPTIONAL PERSON OR PROGRAM TODAY!

Submission Deadline

SEPT. 15, 2025

For more information or to submit an entry, visit chausa.org/awardnominations

Assembly 2026

ST. LOUIS | JUNE 2 - 4

Plan now to attend Assembly 2026 to celebrate the recipients of these distinguished awards and unite for change.

A third factor was working with Epic to simplify the documentation process in Providence’s electronic health record. What began as a standalone note typed into the record evolved into a documentation tool available in any note type, and now AI scans those notes to automatically detect goalsof-care documentation. Regardless of the input method, all goals-of-care conversations are consolidated into a dedicated view within the electronic record for easy review. Gonzales said before the technological improvements, the process of documenting the conversations had been too complicated for some care providers. That sometimes led to several providers asking patients the same questions. The updates to the Epic system mean any clinician can have a goals-of-care conversation with a patient and then the whole care team has easy access to the results.

100,000 conversations

While he is proud of the effort’s success, Gonzales said what heartens him most is knowing that last year alone Providence caregivers learned from 102,066 patients or their families what their hopes were for their care.

He said he celebrated after the first year of the initiative, when the number of documented conversations rose to about 1,100. “I was ready to put up the mission accomplished banner. I was so excited and felt like we had really done something good, and we had,” he said. “But sometimes, when I look back at that graph that we put out and recognize that there were 100,000 of them last year alone, it is hard not to feel really excited about that.”

He said a key overall learning from the initiative is that clinicians aren’t averse to holding or documenting goals-of-care conversations. They just need training on how to lead the talks and simple tools to record the outcomes.

Gonzales and his colleagues behind the effort are now talking with other specialists — such as oncologists, hospitalists and emergency care providers — about how to move the conversations upstream, before patients are in acute care.

“I think that, at the end of the day, patients want to be heard and understood, and I think this is one way for us to be able to get that,” he said. “I would just encourage folks to invest some time in this, because I believe that when we get this right, it’s going to increase engagements and excitement to engage with health care from the people that we serve and take care of.” leisenhauer@chausa.org

On a mission: Cancer program coordinator follows calling to assist others

By JILL MOON

When Alesa Garner was retiring as oncology care center coordinator at CHI St. Vincent Infirmary, hospital leaders asked her if she would consider running the New Outlook Cancer Recovery Program.

A cancer survivor herself who was familiar with New Outlook, she not only accepted but decided to “jump in with all four feet, not just two.” She set her retirement plans aside and has stayed for 26 years with the program that provides free services to cancer patients treated at the Little Rock, Arkansas, hospital and others from a wide region.

“I have helped with, in my time here, someone in every county except one in Arkansas,” Garner, 69, said, “and from all over surrounding states.”

CHI St. Vincent’s auxiliary launched New Outlook 29 years ago, originally to gather resources for women diagnosed with cancer. It now offers a wide range of support, counseling and other forms of assistance, such as access to wigs and mastectomy bras that can be custom ordered, for patients fighting or recovering from cancer. The program is funded by the CHI St. Vincent Foundation.

“People don’t have to be St. Vincent patients,” Garner noted. “We do Zoom counseling for those out in rural Arkansas and navigate for any person, to services they might need in a year, even if it’s not time yet, we give the resources.”

New Outlook also provides blankets, sleep caps, cushions for chemotherapy ports and mastectomy pillows. “They’re all handmade. That’s really special,” Garner said.

The program also helps patients at the Arkansas Children’s Hospital, which doesn’t have a wig program. “If they have kids going through chemo, they come over here,” Garner said. “Caps come in pink for females and purple for males. Guys, they get cold, too, and bald, not just women.”

Foundation donates $75 million to Holy Name in New Jersey

Holy Name Medical Center of Teaneck, New Jersey, has received a $75 million gift from the Douglas M. Noble Family Foundation, which Holy Name says is the largest gift ever to a U.S. Catholic hospital.

The medical center said in a press release it will use the gift to “accelerate innovation and new scientific discovery, advance capital projects, fund medical education and allow the hospital to achieve a future that was previously only a vision.”

This endowment is the latest in a series of gifts the foundation has made to Holy Name. It has provided capital to build and equip Holy Name’s neonatal intensive care unit. The new funds will establish a graduate medical education program. Those funds also will go toward bringing new technology for Holy Name clinical areas, including a neuroendovascular institute.

The gift comes as Holy Name celebrates its centennial.

Douglas Noble was an accomplished neuroradiologist who was owner and medical director of The Imaging Center at Morristown, New Jersey. He died in 2019 at age 59 of a tumor.

A cancer survivor

A clinical microbiologist by training, Garner has been with CHI St. Vincent or in her current role with its foundation for 41 years. Her mother and sister also worked at and retired from CHI St. Vincent, which is part of CommonSpirit Health.

Garner was diagnosed with breast cancer in the late 1990s while raising two teenage children. Her family had no history of any type of cancer. “It was a very shocking thing to happen,” Garner said. Her cancer was caught at stage one and

had not spread. Since her treatment, she has been cancer free. “It was caught so very early, which is such a proponent of preventative care, and listening to your body,” she said.

Before being hired to run New Outlook, she learned about the program through a support group for cancer patients at CHI St. Vincent.

As the program’s coordinator, Garner estimates that she works with 50 to 60 patients per month. Her assistant, Rasa Gillean, was one of them. Gillean came to the

program because of a breast cancer diagnosis 17 years ago. Now she volunteers with New Outlook once a week. She processes patients’ requests for resources, sends mail and helps fit wigs.

Her assistance allows Garner to spend more time with patients. “She’s an inspiration to me in my life, every time I see her,” Gillean said.

Education and support

In her role, Garner educates patients about side effects of treatment and management of symptoms. She also recommends counseling. “None of us are perfect in our brain,” she said. “There’s been a lot of research, but just hearing the words, ‘You have cancer,’ can cause PTSD.”

She also encourages cancer patients to join support groups. “It’s very important,” she said. “People resist getting involved in a support group because they think you sit and cry. But it’s not that; it’s camaraderie seeing people’s faces going through the same thing you went through, experiencing the same thing, but people still living life.”

Over the years, other cancer centers have tried to entice Garner with job offers and higher salaries. She has turned them down because of her dedication to CHI St. Vincent’s mission to help the vulnerable and the poor.

“It’s not about making money,” Garner said. “I like the morning and evening prayer. I like the mission. When you are diagnosed with cancer, you are vulnerable. Everyone is born with a mission. Let’s get about doing it.”

Rural maternity care

From page 1

“I think to continue to do obstetrical care, you have to have a lot of community buy-in,” he said. “If those patients don’t trust the care in their local facility, if they’re going to drive right past that to the next facility, a lot of times that leads to programs not being able to sustain.”

Finding obstetric care in rural regions such as the one that surrounds Parkston in Eastern South Dakota is getting more difficult. The Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a national policy center, says that since 2020, more than 100 rural hospitals have stopped delivering babies. The reasons are many, experts say. They predict the recently passed federal budget bill will be another.

Maternity care deserts

Already, some of Berndt’s patients drive as far as 90 minutes for an obstetric appointment. In South Dakota, nearly 58% of counties are defined as maternity care deserts, compared to about 35% of all counties in the United States, according to a March of Dimes report. The report bases its definition of a maternity care desert on three factors: the ratio of obstetric clinicians to births, the availability of birthing facilities, and the proportion of women without health insurance.

Nearly 24% of women in South Dakota had no birthing hospital within 30 minutes compared to nearly 10% of women nationwide.

South Dakota is among the top six states in terms of percentage of counties that are maternity care deserts, in company with North Dakota, Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska and Arkansas.

Women living in these deserts “have poorer health before pregnancy, receive less prenatal care, and experience higher rates of preterm birth,” said the report.

With rural hospitals already running on tight margins, hospital administrators are worried about the tax package signed July 4 by President Donald Trump that will cut more than $1 trillion in Medicaid and other health care spending over the next decade, although the measure does include a $50 billion fund for “rural health transformation.”

“We know that it’s going to be devastating,” said Ashley Stoneburner, director of applied research and analytics for March of Dimes, which operates mobile health centers for maternity care in underserved areas.

Stoneburner said the March of Dimes is looking at the potential impact of the budget bill on hospitals and whether it will lead to closures and more maternity care deserts. “We don’t know how each state will handle the changes, but we’re worried that states that already have the worst outcomes will have even worse,” she said.

The cost of obstetric care

Workforce shortages and payments from both commercial health insurance and Medicaid programs that are lower than the cost of delivering the services have contributed to closures of obstetric units. While expanding and extending Medicaid has helped, according to the March of Dimes report, one in every 25 obstetric units in the United States has closed in the last two years and already over half of counties lack a hospital that provides obstetric care.

“It’s an unusually difficult service to have because it’s a 24/7 service that requires multiple types of clinical professionals to be available for every birth,” said Harold Miller, president and CEO of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

For a hospital to provide labor and delivery service, a physician who can perform

Maternal care access

The March of Dimes defines maternity care deserts as “areas without a single birthing facility or obstetric clinician.” 35.1% 3.6% 4.1%

Source: March of Dimes

1,104 of 3,142 counties are maternity care deserts 2.3 million of 65 million reproductive-age women live in maternity care deserts

cesarean sections, an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist, and obstetric nurses must always be available. Miller pointed out that with birthrates going down, the fixed cost of having all these clinicians available at all times is causing the average cost per delivery to increase, and many health care plans already don’t reimburse hospitals adequately.

“ We already have a maternal health crisis. We already have poor maternal health outcomes. ... What more is going to happen as a result of the new law?”

— Elisabeth Wright Burak

A bill called the Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act that a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced in June would prevent private health insurance companies from requiring parents to share the costs of childbirth and related maternity care. Miller pointed out that the measure doesn’t ensure that providers will get adequate reimbursement for the cost of the care.

Although adequate reimbursements would enable many small rural hospitals to keep their obstetric units open, Miller noted that many larger hospitals close their units “not because they’re being forced to do it, but simply because they don’t want to continue providing an expensive service that is difficult to staff.”

A ‘gutted’ safety net

Nationwide, 23.3% of women of childbearing age in rural areas are covered by Medicaid, compared to 20.5% of women in metro areas, according to the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy Center for Children and Families.

Elisabeth Wright Burak, a senior fellow with the center, said Medicaid pays for nearly half of births in rural areas. How the upcoming cuts to Medicaid will affect those payments is unclear, but the loss of funding could prompt states to reduce funding to hospitals, which then might be forced to end costly services that don’t generate much revenue, such as obstetric care.

“Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of questions about what the biggest cut in Medicaid history is going to mean for rural communities and the women who rely on Medicaid there,” Burak said, referring to the federal budget cuts. “We already have a maternal health crisis. We already have poor maternal health outcomes. We’re already in a situation where women are having to drive longer distances to have babies. What more is going to happen as a result of the new law?”

Because of lost federal dollars, states likely will have to make funding cuts that might affect everyone’s health outcomes, not just those of pregnant mothers, Burak pointed out.

“That unfortunately puts a lot more

SSM Health uses federal grant funds to reach patients in Southeast Missouri

Donna Spears, administrator for SSM Health Women’s Health, will never forget the time she visited New Madrid, Missouri, and a pregnant woman pulled up on a riding lawn mower for prenatal care at the health clinic. It was a warm day, and the lawn mower was the woman’s only transportation from her home across town. A young child sat in a trailer behind her.

“And that tells you how the poverty in this area is just unbelievable,” said Spears.

New Madrid is in the Missouri bootheel, where the poverty rate is particularly high. There is not only a lack of access to care but also transportation and internet connectivity issues.

The New Madrid clinic is one of four locations in Southeast Missouri where SSM Health has used federal grant funding to provide maternal care. The system has trained on-site clinicians on how to do the work, and a high-risk obstetrician consults remotely.

“There’s a lot of gratitude,” for the services, said Spears, who oversees women’s health in Missouri and Illinois.

Last fall, SSM Health received a fiveyear federal grant totaling more than $7 million from the Health Resources and Services Administration to develop medical home models to provide other resources, like a social worker, diabetes education, or midwifery or doula support, to patients in remote areas. Years earlier, SSM Health partnered with the Bootheel Perinatal Network to share resources to improve maternal and infant health in the area’s six counties.

Spears has advice for other health systems regarding maternal care access: Listen to people in local communities, and then “partner and dig in.”

“They don’t need the big city telling them what to do,” she said. “They need partners, and we need to hear from them. What do you need? What are your resources? What are your gaps?”

On its own, Spears said SSM Health wouldn’t know the breadth and depth of problems, which is needed to seek and justify grants.

“None of that’s possible without the partnerships,” she said.

— VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

strain on the Catholic social and health service systems already challenged to do everything they can do for their families with limited resources,” she said. “It’s the entire safety net that’s going to be gutted.”

New payment and staffing models

Miller said that because of the difficulties in attracting obstetricians to live and work in small rural communities, some small rural hospitals have adopted a model in which physicians with obstetric training

150,000 of 3.5 million births in 2022 were to mothers who live in maternity care deserts

who live in a different community come to the rural hospital for a week or more at a time to handle labor and deliveries. The cost of doing this is higher, Miller said, but the model alleviates the challenge of finding specialists who are willing to be fulltime employees in the rural community.

A potential solution to ensuring adequate payment for obstetrics care in rural areas, he said, is for insurance companies to adopt a two-part payment model that would offer a “standby capacity payment” designed to cover the fixed costs of maintaining 24/7 obstetric care staffing and fees for individual services designed to cover the additional variable costs incurred when a baby is born. A hospital provides an important service simply by being there and available to deliver a baby, Miller said, and the standby capacity payment would ensure the cost is covered regardless of how many babies are delivered at the hospital in a particular year.

“It’s the same thing in terms of the ED,” he said. “It’s a good thing that if I don’t need emergency care, but I certainly want the ED to be there in case I do. Health insurance plans need to pay hospitals adequately to have emergency physicians and nurses available on a 24/7 basis regardless of how many emergencies there actually are.”

Fixes in rural areas

As access to obstetric care tightens, hospital systems are coming up with ways to help expectant mothers in rural areas.

In Southern Illinois, SSM Health is part of the Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative. The collaborative promotes initiatives such as one focused on safe sleep for infants; education on perinatal mental health conditions; and effective communication, collaboration and clinical care during childbirth.

In Louisiana, the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System announced in April that three of its hospitals have earned designations from the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative. To earn the designation, the hospitals had to meet stringent criteria in categories like health equity, evidence-based policies and education, and measurable outcomes.

Avera is using grant funding from the federal Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies Program to increase access to obstetric services and help prevent conditions such as preterm labor and low birth weight. The federal funding allows for remote patient monitoring. A virtual hub of experienced labor nurses can review fetal heart strips or advise nurses at the bedside who don’t deliver babies as often.

Berndt calls the hub “a huge resource for our nurses.” He has had a few high-risk patients who don’t want to travel to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, to see a specialist, so he monitors them while staying in touch with the specialist.

“We hope, or I always believe, that if we can provide obstetrical and general wellness care that’s at a high-quality level, that helps our small communities to grow, they don’t have to go anywhere else for the care that they need,” Berndt said. “Hopefully, down the road, that leads to more patients, stronger communities, better care. But you have to believe in that, because it is a lot of investment to provide rural obstetric care.” vhahn@chausa.org

Hogs House at Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital gives families a place to stay

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Love — and a love of pigs — is apparent inside the family support home next door to Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

There’s a paper-mâché pig in the living room area. Pig signage on the doors. A pig mural.

“You have to find joy,” said Dr. Shaun Kemmerly, chief medical officer for the hospital. “You can find joy in pigs.”

Families of children treated at the hospital can stay for free at the home, called Hogs House. Its full name is Hogs for the Cause Family Support Home at Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital.

It opened in February 2024, thanks to community contributions and a $2.25 million pledge from the nonprofit Hogs for the Cause.

The group fundraises year-round to support families and pediatric brain cancer research. It hosts one of the largest barbecue and music festivals in the country each spring in its home base of New Orleans, which Kemmerly and some of her friends and colleagues attend.

“We take a big bus and we go,” she said. “It’s a lot of fun.”

Hogs for the Cause also has helped fund a family support home at Manning Family Children’s hospital in New Orleans and is planning one in Florida.

Becker Hall, one of the group’s founders, said a Hogs House gives families “emotional healing.”

“It removes a financial burden, and it gives them a sense of community,” he said. “It allows families, a lot of times, to stay together.”

Kemmerly explained that when Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital, part of the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System, opened as a freestanding

Community bus tour

From page 1

clients of the nonprofits and hear about some of the challenges of living on the margins in Longview.

Thomas says she and the other tour participants “learned how much of a struggle some community members face. We learned about the stressors they have.” Thomas says several of the doctors now want to volunteer with the nonprofits.

Egbe hosts the bus tour. “It’s important to get to know your community and get involved and connected,” she says.

She says the tour helps the medical residents understand the context of residents’ lives. “Much of people’s medical treatment takes place after they go home from the hospital,” she adds. “Do they follow through? If you don’t have context, how can you help them?”

‘Alarming’ disparities

The annual bus tour is affectionately called “Who Are the People in Your Neighborhood?” in a nod to the old ditty once sung on Sesame Street. Egbe started the tours in 2018 after becoming the program director for the internal medicine residency at Good Shepherd. That three-year residency is a partnership between CHRISTUS Health and Texas A&M University College of Medicine.

Egbe says one reason she started the bus tour is that she saw very poor health outcomes in East Texas despite its great health care facilities and clinicians. She believes by seeing the whole picture of patients’ lives and understanding their lived experiences,

hospital in 2019, parents’ options were to stay the night in the hospital rooms or at a hotel or travel back and forth from home.

“As we’ve grown, we’re taking care of children from all over the state of Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas,” said Kemmerly. “We realized that we were just taking care of kids from farther away. So we felt this would be a huge benefit to our families.”

Hogs House allows the hospital to stay true to its mission as a Catholic health care provider, she said.

“It just allows us to give back to the community in a special way that’s not necessarily at the bedside or medical, but it’s still healing,” Kemmerly said. “I think they definitely feel the presence of Jesus Christ, and that’s important.”

physicians can do a better job of treating them.

And change is necessary. According to analysis by the East Texas Health Project at the University of Texas at Tyler, Northeast Texas “is a large, primarily rural region of the state that has alarming health and mental health disparities. The region suffers from some of the highest rates of chronic health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and cancer. In addition, mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder are more common in Northeast Texas when compared to state and national averages.”

That analysis adds that “many of these health conditions remain untreated or undertreated due to increased barriers to care faced by rural communities ... Particularly for mental health services, Northeast Texas suffers from a chronic shortage of mental health providers, long waitlists for behavioral health services, and increased travel time and costs for patients seeking treatment.” The analysis says that the pandemic exacerbated disparities that existed before 2020.

Court advocates, family services

Each summer, the bus tour takes place during the residents’ orientation. The bus, which the city of Longview donates for the several hours of the tour, meanders around south Longview neighborhoods.

Egbe says this area used to be a hub of the city, but the population shifted north, leaving the south side in decline. Now, much of the south Longview population is low-income, with many elderly people on fixed incomes, she says.

The tour stops at nonprofit partners of Good Shepherd. In past years, these partner organizations have included Newgate Mission, Highway 80 Rescue Mission and OneLove, organizations that meet the needs of marginalized people; Longview Child Development Center; Longview

Forming the partnership

Hogs House is in the back corner of the hospital’s parking lot, and families can walk there or get a golf cart ride from security. There’s a reception space, a living room, a kitchenette stocked with microwaveable foods, washers and dryers, vending machines, and six private rooms on the first floor and six on the second. The private rooms have a queen-sized bed and a single bed. The home also has a “sweet little back yard” and a “sweet little back porch,” said Kemmerly.

The community voted on Facebook to name the Hogs House pig mascot Rosie. The vote was a fun way to engage staff and the community, Kemmerly said.

A manager runs the house, and it’s

Animal Adoption Center; East Texas Court Appointed Special Advocates; and the Refuge International medical mission organization.

This year’s stops were at the Court Appointed Special Advocates organization, where the visitors heard moving stories from volunteers who stand up for children in the legal system; and Buckner Children and Family Services, where the group met single moms and their families facing many barriers to success but getting help to address those concerns. At Buckner, the physicians played with children whose families are clients of the nonprofit.

Food deserts and money deserts

Egbe says that while touring south Longview, the physician residents can see that there are few grocery stores or banks, but many convenience stores and predatory check-cashing businesses. At the stops at the nonprofits, they hear about how difficult it is for families to get by. Learning about food deserts, money deserts and other social determinants of health, says Egbe, the physicians “immediately feel more empathy and respect for our patients” who face such obstacles. Through conversations, she adds, “the residents see how challenging access to health care can be.”

In addition to fostering understanding among the physicians, Egbe seeks to encourage the physicians to build relationships with their patients as well as the broader community. She says a goal of the residency is to encourage internal medicine physicians to remain in East Texas, which has a severe shortage of primary care physicians.

An additional motivation for the bus tour and for the residency, she says, is to ignite “an initial understanding of and connection to the Longview community and to our patients. We hope to also awaken a lifelong calling to serve others and to continue to

staffed 24 hours a day by team members. Security and maintenance staff also provide support.

Kemmerly and others have been working with the hospital’s social workers and schedulers to spread the word about Hogs House. A pig-themed celebration on the one-year anniversary of the home’s opening helped. Families who stay at the home must demonstrate a financial need, though the parameters are generous, Kemmerly said. In just one year, the Hogs House welcomed 244 families, including 126 who returned for multiple stays.

A relieved family

Amelia Green stays at Hogs House once or twice a month when she brings her 3-year-old son, Maverick, to medical appointments. Maverick has a genetic disorder called campomelic dysplasia. The family lives about 200 miles away in northern Louisiana.

When Maverick was born in early 2022, he was in the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit for 53 days, and the family stayed in the room with him. When Green and her husband got COVID-19 during that time, they had to stay in a hotel.

At Hogs House, they have a welcoming home that eases a financial and emotional burden. “The front desk staff, they’re always so nice. Everything’s always so clean. It’s right by the hospital, so you don’t even have to drive,” Green said.

And every time Maverick visits, he has to get a picture with the paper-mâché version of Rosie the pig, she said.

“One of my good friend’s sons just started seeing the neurologist there, and I told her about the Hogs House, so they also utilize it,” she said. “I just think it’s a good resource. I try to tell anybody that I can about it.”

vhahn@chausa.org

spread the healing ministry of Jesus Christ.”

The strategies work. The new doctors often volunteer for the organizations they visit during the tour, as well as for other organizations they learn of from Egbe and others on the team that works with the residents. Also, many of the residents stay at Good Shepherd to practice post-residency.

Partner connections

The tour is just one part of the relationship between Good Shepherd and its nonprofit partners.

Many of the partners receive grant dollars from CHRISTUS Health’s Community Impact Fund. The fund invests in nonprofits that address the social determinants of health.

Relationships with the partner organizations have paid off in unexpected ways, notes Egbe. For instance, when COVID first hit, Good Shepherd was in dire need of personal protective equipment, and one partner, Refuge International, gave Good Shepherd its excess.

New perspective

Physician resident Thomas says she found the bus tour enlightening. She was struck by the disparities endured by the families the tour participants met. But she was pleasantly surprised by the wealth of programs and resources that the nonprofits offer to help.

She says the tour gave her new insights that she certainly will apply in her practice. “When I interact with patients, I will be considering the family stressors, and what issues they are facing,” Thomas says, “because that could affect their health and health care access.”

She adds, “As part of a multidisciplinary team, if I know of issues facing my patients, I will want to work with case management to ensure those issues are addressed.”

jminda@chausa.org

No One Dies Alone

From page 1

Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center near Los Angeles, a part of Providence St. Joseph Health.

The program relies on trained volunteers to take shifts to sit at a dying person’s bedside. They read aloud, pray, play music, and watch for changes or signs of distress. Most importantly, they provide a compassionate presence.

“There’s dignity and love, even in death,” Kiley said. “How can we provide that and make that happen?”

Sandra Clarke, then a PeaceHealth nurse in Eugene, Oregon, started the No One Dies Alone program in 2001 after she was called away from the bedside of a dying man who had no visitors, and she missed the moment he died. The concept has since spread worldwide, although hospitals have various approaches and names for their programs.

“Death is the second most natural part of life. Birth and then death. It’s a continuum. I think we’ve lost the interest in that last portion — it’s treated as a failure or something to be ignored,” Clarke said in a 2008 interview with Nurse.com.

Companionship beyond the dying

Barbara Stephen is the head of the volunteer department and a bereavement

specialist for Trinity Health Oakland and Trinity Health Livonia in Michigan. She started the hospitals’ Comfort Companion program in 2005 after her mother’s death from cancer the year before. While she visited her mother in a hospice, she noticed that other dying patients didn’t have friends or family. When her mother was sleeping or had visitors, Stephen slipped out to sit with them.

The Comfort Companion program is not just for the dying — it’s also for patients who likely will recover but have nobody to sit with them, she explained. A volunteer might talk with or read to a patient. The companions also stay with patients whose family members simply need a break.

“My big thing is I want family to be family,” Stephen said. “I don’t want them to be a caregiver during this time. So let us take that burden and just be with your loved one.”

If a companion is needed, hospital staff and palliative care teams contact Stephen, who consults her roster of about 40 volunteers.

Most of the patients referred to the program are in a comatose state when their companions arrive. Still, the volunteers try to learn as much about the patients as they can, including their spiritual beliefs or religious background, so they can respond appropriately.

Stephen remembers asking the daugh-

Hope. Healing

ter of a dying man what she remembered about him growing up. The woman replied that he never missed a day reading The Wall Street Journal. Stephen arranged for volunteers to read that newspaper to him over the three evenings they sat with him. When the woman saw Stephen next, she burst into tears. Stephen thought something was wrong.

“It was perfect,” the daughter said. “I walked in this morning and one of the gentlemen was reading The Wall Street Journal to him.”

Stephen trains volunteers and coordinators around the country and happily shares her materials. She teaches volunteers to always introduce themselves even if the patient isn’t awake, because often patients can hear. She asks volunteers to keep an eye out for any signs of distress so they can call staff. They don’t provide medical care but can moisturize a patient’s lips or cool them with a washcloth. They may hold a patient’s hands unless the patient withdraws.

“For as many times as I have done it, it is very fulfilling, because we find out that especially those that have no family, it’s like they really want to be remembered,” Stephen said. “That’s the one thing that we always reassure them: that they will always be remembered.”

Connecting

through stories

Colleen Storey is the holistic care supervisor of PeaceHealth Hospice based in Vancouver, Washington. Its No One Dies Alone

program extends to hospice and community settings, including assisted living and skilled nursing facilities.

Storey didn’t know Clarke, who also worked for PeaceHealth. Storey and her supervisor launched their program in 2017 after seeing it at work elsewhere.

When she trains volunteers, she pairs them off and asks them to imagine and share what their deathbed scene looks like. At first, they are somewhat appalled by the notion, but Storey presses them. At the end of the exercise, she asks for a show of hands: How many of you were in pain? How many of you were alone?

“Not one hand goes up,” she said.

She shares stories with them, to make the prospect of sitting with the dying less intimidating. There was the elderly man who told Storey about fishing with his granddad when he was a boy. Then he leaned back in bed and looked toward a corner of the room. “Yes sir, I’m ready,” he said. Storey asked who he was talking to, and he said, “Granddad’s right here.” The man leaned back against his pillow, shut his eyes, took a breath, and died.

Storey stayed with an elderly woman who was unconscious and actively dying. The woman had a favorite grandson who was an archaeologist working at a remote site in China. As the grandson made the five-day trip back to the United States, Storey and the woman’s daughter assured the dying woman he was on his way.

The door finally opened, and the grandson came in, wearing his archaeologist’s hat and clothes. “It was like a scene out of Indiana Jones,” she said. The grandson told his grandmother he was there. The woman gave the slightest smile, took a deep breath, and died.

The PeaceHealth Hospice program has about 90 volunteers. “It changes us in such deep, profound ways,” said Storey. “We have volunteers who have done this for a while, and they say, ‘The gifts I have received far outweigh what I do.’”

Employees as volunteers

Kiley said Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center would like to expand its program to serve people who need companionship but aren’t necessarily dying. The program’s roster is mostly hospital employees — executives, food and nutrition service workers, and care providers — who often go into volunteer mode before or after their regular shift. They keep a journal that serves as a record for the next volunteer. It might contain personal information about the person and what happened on the shift. If there are family members, the journal is given to them as a record of the person’s final days.

“When there’s family involved, I think it’s healing for them to know that there’s somebody with their loved one,” said Terry Lucas, a nurse manager at the hospital who volunteers for the program. The staff appreciates knowing someone will be with their patients, too.

Lucas became a nurse during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and saw many young people with no one at their bedside in their final hours. “I’ve just always been very sympathetic to somebody dying alone in the hospital,” she said.

Sitting with a dying patient compels her to reflect on life and the patient’s circumstances. “I guess we all help people in other ways, but this, we get to help people in very vulnerable times,” she said.

Kiley pointed out that no one is born alone. “And I think that as a human being, that speaks to us as caregivers and as humans, just to say we can do better,” he said. “Let’s provide some compassionate presence.” vhahn@chausa.org

St. Joseph’s Hospital in Savannah, Georgia, marks its 150th anniversary

St. Joseph’s/Candler Health System in Savannah, Georgia, recently commemorated the 150th anniversary of the founding of its St. Joseph’s Hospital with an employee gathering, Mass, celebratory meal and other events.

At the staff celebration on the June 30 official anniversary date, employees received a commemorative glass teacup to bring to mind the call by Catherine McAuley to her fellow sisters to provide a good cup of tea to comfort anyone in need. Nuns from the Sisters of Mercy congregation that Venerable McAuley established were the foundresses of St. Joseph’s. The Mass that took place a couple of days before the employee event was concelebrated by Bishop of Savannah Stephen D. Parkes and priests from throughout the diocese. After the Mass, the hospital hosted a meal for all attendees. The hospital also hosted a luncheon for the Sisters of Mercy.

During a press conference St. Joseph’s/ Candler held amid the celebrating, President and CEO Paul Hinchey credited the “extraordinary” legacy of St. Joseph’s to the sisters whose “commitment to this community, and their bold vision for the future … brought us to this moment.” He also thanked employees, physicians and community leaders for their significant contributions to the hospital’s success.

St. Joseph’s traces its start to 1875, when Fr. Jeremiah Francis O’Neill asked six Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Mercy, a congregation that was part of the Sisters of Mercy, to take over operations of a Savannah sailor’s hospital called Forest City Marine Hospital.

Volunteers with Cape Girardeau, Missouri’s Saint Francis Healthcare System pack boxes of food.

In total, about 200 volunteers filled 153 boxes with 33,048 meals, which were given to two community organizations for distribution to people in need.

The meal packing event was in honor of the facility’s 150th anniversary.

Those sisters had been serving as educators at a private Catholic school and orphanage in Savannah. The women took over operations of the struggling hospital and a year later moved the facility to a shuttered medical college, renaming it St. Joseph’s Infirmary. That summer, the sisters helped save many patients from the yellow fever epidemic.

In 1901, the facility got a new name: St. Joseph’s Hospital.

In 1997, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Candler Hospital of Savannah entered into a joint operating agreement to form the St. Joseph’s/Candler system.

Over the years, the St. Joseph’s facility has grown into a 330-bed hospital, renovated and added outpatient sites.

Idaho’s Saint Alphonsus offers loan repayment program for health care workers in some roles

Saint Alphonsus Health System of Boise, Idaho, has started offering a student loan repayment program for workers in some clinical roles.