In new movie Soul On Fire, Catholic health care plays a starring role

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

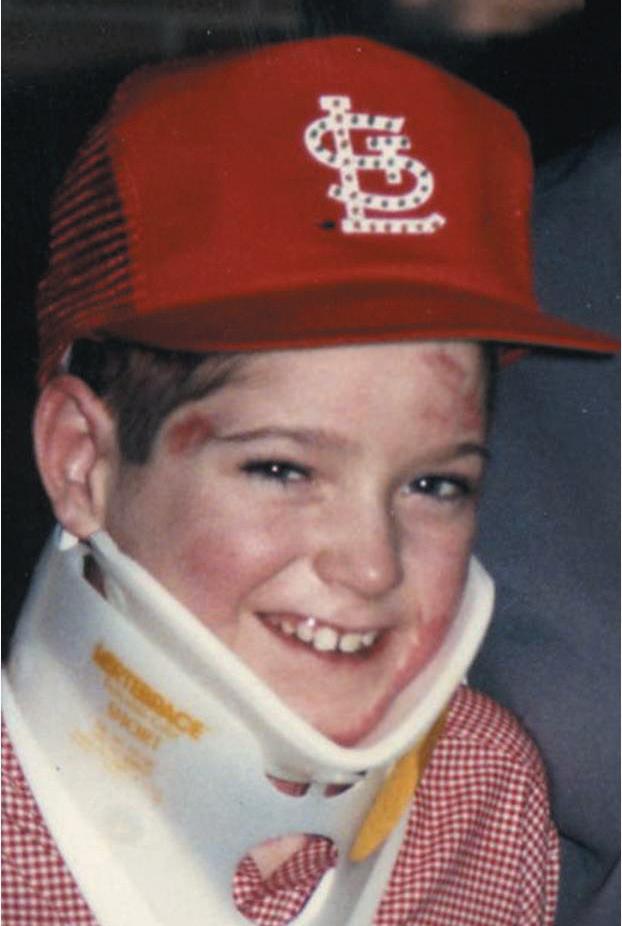

ST. LOUIS — Inside the emergency room of what’s now Mercy Hospital St. Louis, 9-year-old John O’Leary lies burned on 100% of his body. He asks his mother if he is going to die. “John, do you want to die?” she answers. “Mom, I don’t want to die,” he responds. “I want to live.” His mom pats his head and replies: “Then baby, you need to fight like you’ve never fought before. You need to take the hand of God and you need to walk this journey with Him. But John, you listen to me: You are going to have to fight.” The scene is from Soul On Fire, which debuts in theaters nationwide on Oct. 10. The movie is based on the book On Fire by O’Leary, now 48.

Providence-backed partnership helps ease child care crisis in Northwest Oregon

By JULIE MINDA

Clatsop County in Northwest Oregon already had a shortage of child care options when the pandemic greatly exacerbated the problem.

Concerned about the situation, a collaborative of leaders from public and private organizations convened to assess the problem and come up with solutions.

Providence St. Joseph Health’s Oregon region is a backer of the Clatsop Child Care Retention and Expansion Program. Continued on 8

SSM

Health expands age-friendly care initiated in Wisconsin across system

By LISA EISENHAUER

When leaders of SSM Health’s Wisconsin region decided to give the Age-Friendly Health Systems care model a go, the initial idea was to pilot it at SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital — Madison. But before the launch, they decided to go bigger.

The age-friendly model is an initiative of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and The John A. Hartford Foundation, two nonprofits focused on better health care, in partnership with CHA and the American Hospital Association. The model was designed to meet the challenge of caring for the nation’s aging population, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement has recommended starting the model in a single unit.

Chris Baker, Wisconsin region administrative director of nursing excellence and professional practice, is one of the SSM Health leaders who have championed agefriendly care. “We were already breaking the mold by doing it on 23 units at Madison,” Baker recalls. “And then we thought,

‘Nobody wants to go to work and be scared’: Bon Secours Mercy rolls out wearable panic buttons for staff

By JULIE MINDA

Over the next half year, Bon Secours Mercy Health is outfitting select staff with wearable panic buttons, or duress badges. If the employees feel that their safety is threatened, they can double-tap the buttons to discreetly summon help.

The health system is making the devices available to most patient-facing team members in emergency departments and behavioral health units and at on-campus medical practices at its 50 hospital locations across Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, New York, Ohio, South Carolina and Virginia. Bon Secours Mercy Health is using the technology because of increasing threats or incidences of violence against health care workers in recent years, says Jodi Pahl, Bon Secours Mercy Health chief nursing officer for workforce, outcomes and experience of care. “Nobody wants to go to work and be scared of being there,” Pahl says. “With

A young John O’Leary is wheeled out of the hospital in the movie Soul On Fire, which tells the story of his recovery and transformation into a motivational speaker. Many of his caregivers at what is now known as Mercy Hospital St. Louis served as extras.

Amanda Shelley runs Magical Moments In-Home

and Play School in Seaside, Oregon. She opened the child care with funding from the Clatsop Child Care Retention and Expansion Program.

Community Connect

Hospital Sisters Health System, with locations in Illinois and Wisconsin, creates a digital database to help people learn about and reach free or reduced-cost community-based services.

ICU wedding

An Ascension hospital lends a hand to stage a bedside wedding so a father can witness his daughter’s big day. The bride's grandfather performed the ceremony and other relatives were witnesses.

$5 million donation

CHI St. Vincent gets its largest single gift ever for the regional health network that serves Central and Southwest Arkansas. The money will be used to build a cardiac care center.

Clinical Innovation Institute to take Ascension to ‘next level’

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Ascension recently launched a Clinical Innovation Institute, which brings together a team of its leaders to focus on improving patient care and the experience of clinicians through technology and innovation.

“We’re accelerating a lot of great work,” said Dr. Thomas Aloia, Ascension executive vice president and chief clinical officer, a role he assumed in January. “This isn’t like a start from zero. Maybe the car was going at 60 mph, and now we have an infusion of leadership, commitment and capital to take it to the next level and speed us up.”

The current budget for the institute is $20 million and there are more than 100 full-time equivalents of staff working under its various units.

The institute, announced in early August, will take a closer look at technology that will help patients while at the same time reduce digital and administrative burdens. The institute also will facilitate access to the latest critical trials to advance care.

The four leaders who will direct the insti-

tute are: Dr. Mitesh Patel, vice president and chief clinical transformation officer; Dr. Samit Desai, vice president and chief medical information officer; Dr. Fred Masoudi, vice president and chief academic officer; and Jon Taves, associate vice president of clinical innovation.

Charged to ‘achieve excellence’

When Aloia took on his new role, he said CEO Joseph Impicciche and President Eduardo Conrado, set to be CEO upon Impicciche’s retirement at the end of this year, challenged him to envision the next 10 years of clinical care. He said they wanted leaders to ponder: “How are we going to differentiate, and how are we going to achieve excellence?”

“Ascension doesn’t have the luxury of innovating for innovation’s sake,” Aloia said. “We really have to tie it to the mission. We have to tie it to quality and safety.”

Ascension is one of the largest Catholic health care systems in the United States. It operates in 16 states and the District of Columbia, running 94 wholly owned or consolidated hospitals.

The mere size of the system forces its leaders to be deliberate in their work, Aloia

said. “You might have a vendor approach 11 of our hospitals a day with a great idea, or what appears to be a great idea,” he said. “If we can vet it and then facilitate it for the markets, that’s gold.”

The institute’s leaders will charge themselves to catch up with technology. Like many health care organizations in the United States, Ascension relies in part on technology that can date as far back as the 1980s, Aloia pointed out. “The watch on your wrist has vital signs capabilities that exceed what we use in a typical hospital in America,” he said. “That’s a great example of catch up, and then do true innovation.”

Aloia said that despite the challenges ahead, especially with potential Medicare cuts, Ascension will continue to care for the poor and vulnerable.

“There’s no way the traditional ways of doing health care are going to work in the future,” he said. “So we’ve got to create new care models and be hyper selective and call out those brilliant, game-changing technologies and implement them if we’re going to be successful. If we don’t innovate, we will fail against the challenges of payment reform.”

vhahn@chausa.org

CHA’s enhanced community benefit guide includes new look, updated rules

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

CHA has recently released an updated edition of A Guide for Planning & Reporting Community Benefit

Considered the essential source for Catholic and other not-for-profit health care organizations that are working to respond to the unique needs of their communities, the 340-page guide includes an easier-tonavigate layout and updates on definitions and community benefit categories.

“Community benefit is an extension of our mission,” says Nancy Zuech Lim, CHA’s director of community health improvement. The guide is a go-to resource for ministry organizations and governmental leaders to ensure that not-for-profit health care providers measure and report community benefit in a consistent way.

CHA has been the leader in nonprofit hospital community benefit for more than 35 years. In 1989, CHA published the Social Accountability Budget: A Process for Planning and Reporting Community Service in a Time of Fiscal Constraint and has built on that to offer guidance to the field of community benefit. Over time, this guide has had several editions and the name transitioned to its current title in the early 2000s. The community benefit categories and definitions developed by CHA and included in the newest edition informed the IRS’s creation of Form 990 Schedule H, which is submitted by nonprofit hospitals to report their expenses related to commu-

nity benefit as required for their tax-exempt status. CHA’s guidance and the IRS Form 990 Schedule H instructions continue to align today.

The guide includes recommendations on assessing community health needs, developing action plans and programs to address needs, monitoring and reporting outcomes, and telling the community benefit story. The last update was in 2022.

“The guides have evolved over time, and at the core they’ve always been about our mission of being a part of the community, looking around and seeing what was needed, and then answering the need,” Lim says. “That’s part of how we formed as Catholic health care.”

She points out that the guide not only outlines federal policies that need to be

fulfilled but also lays out a call to serve the community and to pursue and attain health equity, so all may flourish. Community benefit flows from Catholic social teaching and the core values of human dignity, the common good and a special concern for those who experience poverty and marginalization.

“We do this work, not because it’s required, but because it’s the right thing to do, it’s central to our mission as not-forprofit health care, and it’s what we have always done,” she says.

The 2025 edition updates include: Community health improvement services category definition and examples to align with the 2023 changes to the instructions for Form 990 Schedule H.

Enhanced guidance on accounting for indirect costs.

Updates within Category B: Health Professions Education to include graduate and undergraduate medical education and continuing health professions education as separate categories.

The pages that divide chapters include one graphic flourish: a line drawing that represents a healthy EKG reading that then evolves into an outline of buildings and trees, which represent rural, suburban and urban communities. “Individual health is influenced by social factors and the health of the community,” Lim says. “So much about how well and how long we live is based in the systems and policies of our communities.”

The 2025 edition is available to members and nonmembers. To learn more and access the guide, visit chausa.org/guide.

Catholic Health World (ISSN 87564068) is published monthly and copyrighted © by the Catholic Health Association of the United States. POSTMASTER: Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to CHA Service Center, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone: 800-230-7823; email: servicecenter@ chausa.org. Periodicals postage rate is paid at St. Louis and additional mailing offices. Annual subscription rates: CHA members free, others $29 and foreign $29. Opinions, quotes and views appearing in Catholic Health World do not necessarily reflect those of CHA and do not represent an endorsement by CHA. Acceptance of advertising for publication does not constitute approval or endorsement by the publication or CHA. All advertising is subject to review before acceptance.

Associate Editor

Vice President Communications and Marketing Brian P. Reardon Editor Lisa Eisenhauer leisenhauer@chausa.org 314-253-3437

Associate Editor Julie Minda jminda@chausa.org 314-253-3412

Aloia

Lim

In fellowship program, Providence staff devise practical solutions for real-life health inequities

By JULIE MINDA

Under a fellowship program that Providence St. Joseph Health launched amid nationwide racial unrest, a group of its associates get in-depth education and training on health inequity and develop practical approaches for closing equity gaps.

Staffers from across Providence attend monthly learning sessions with internal and external faculty as a cohort. At the same time, they design and put in place programming to address health inequities in their own facilities. After the fellowship, the participants teach others what they’ve learned, share their successful programs, and spread enthusiasm for health equity throughout Providence.

“We’re making an investment in about 20 fellows every year, but we’re really getting hundreds of champions from this program over time,” says Whitney Haggerson, vice president of health equity and Medicaid. “All of our fellows are deeply committed to advancing health equity and to teaching others to do the same.”

Multimillion-dollar pledge

Providence founded the fellowship under a body of work it began in late 2020 in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer. Floyd’s death put a spotlight on racial disparities across the nation. Providence and many other health systems took a hard look at how differential treatment of many minority people and other vulnerable populations resulted in worrisome health inequities.

In September 2020, Providence pledged $50 million over five years to address such inequities.

Haggerson says before the fellowship program Providence had involved large groups of associates in an Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative learning program on health system change.

Providence hospital associate improves sepsis outcomes for vulnerable population

By JULIE MINDA

A staffer of a Providence St. Joseph Health hospital used her time in a yearlong health equity fellowship to study sepsis outcomes of people with limited English proficiency, survey affected patients, consider evidence-based solutions, and put those interventions in place.

But, she says, Providence wanted to find a way to give associates an even deeper understanding of health inequity and an opportunity to put the ideas into practice. So, the health system developed the fellowship using evidence-based concepts on change management. It launched the fellowship in 2023.

Fellows, sponsors, champions

Providence employs about 125,000 staff in its 51 hospitals, 1,014 clinics and its other sites across Alaska, California, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas and Washington. Any staff member can apply for the fellowship, which has cohorts running from June to June. The third cohort is currently underway.

When associates apply for the fellowship, they must share their idea for a project they will complete during the year to address health inequities. The project may change during the course of the fellowship.

When selecting fellows, Haggerson says, “we prioritize high-impact, high-value ideas” that are replicable throughout the system.

Those accepted attend monthly virtual sessions with a comprehensive curriculum on health disparities. Faculty are Providence administrative and clinical leaders as well as external contributors including leaders from IHI, the National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Each of the fellows has an executive

Include your organization’s Christmas message in the December issue of

Catholic Health World invites you to extend a seasonal greeting to your employees and to colleagues in the Catholic health ministry. Visit chausa.org/Christmas for more details. Send an email to ads@chausa.org to reserve your ad space.

Ads due by Nov. 17

sponsor at their facility who guides them as they execute their project, a champion who is a system-level leader who can assist in getting Providence support, and a coach who helps address the practicalities of carrying out their project.

The fellows give about 20% of their work time to the program. They not only attend the virtual learning sessions, they also attend virtual group discussions to talk through how their projects are going and what’s ahead. They meet in person halfway through the fellowship for more learning and to refine their projects and then again at the end to formally present the results.

Past fellows have completed a range of projects. For instance, one project markedly reduced the length of stay and readmission rates for people with sepsis who had limited English proficiency. Another led to improvements in those metrics for Black patients with sepsis.

All the fellowship graduates share what they’ve learned, including by serving in various roles with the subsequent cohort. Those whose projects were successful work to spread their approaches beyond their immediate facility, including by presenting the ideas to other health facilities, some of them outside of Providence.

‘Raw enthusiasm’

Haggerson says the fellowship program has been transformational at Providence, enabling frontline associates to address the root causes of inequities at their facilities. “The fellows are taking what they learn and applying it in real time,” she says. “This is not just academic.”

She says the fellows “elevate the visibility of problems” at the local level. “It is valuable to get this type of response to the unique needs of communities, and you get more passion … because this is deeply personal work,” Haggerson adds. “This is affecting the fellows’ families and neighbors.”

She says because the fellowship employs a continuous learning model and quality improvement science, and because adaptability and flexibility are encouraged, the fellows can evolve their projects in real time. This refinement has resulted in programs that advance care quality and promote positive health outcomes.

Haggerson says that since fellows are encouraged to spread their knowledge, this teaches everyone “that health equity is the job of all of us.”

She notes that the fellows also grow as leaders because they learn about maintaining executive presence, gain the capability to use data well, build confidence, and interact with top executives from throughout Providence. “We’re developing the workforce of the future,” she says.

“We are really getting raw enthusiasm from some rising leaders,” Haggerson says. “And at the same time, we are getting at the root causes of health inequity. I can’t think of anything more important to do.”

jminda@chausa.org

Moojan Rezvan, who is a medical interpreter and the interpreter services supervisor at Providence Mission Hospital, led the project beginning in summer 2023. The work resulted in measurable improvements to the health outcomes of patients with sepsis who were not proficient in English. Because of the pilot project’s success, it is now a permanent offering of Providence Mission Hospital, which is in Mission Viejo, California.

Lack of trust, communication

At the start of her project, Rezvan worked with Mission Hospital’s quality improvement team to analyze data and learned that sepsis patients with limited English proficiency had longer lengths of stay and higher readmission rates than other patients with sepsis.

Rezvan set up a focus group. Surveyors spoke with patients who were Spanishspeaking and not proficient with English and who’d been hospitalized with sepsis. Talking with those patients and their family members, the team found four main areas of concern: People did not have a good understanding of the disease process for sepsis, they did not fully trust hospital staff, there were communication breakdowns, and there was a lack of continuity in care post-discharge.

Based on those findings and additional research, Rezvan developed and put in place solutions. One was to build partnerships, including with clinics, to educate community members generally about sepsis in their own language and to address barriers to care. Another was to create printed materials about sepsis and have them translated into the top four languages spoken by Mission Hospital patients.

Nurse navigators

But the most impactful intervention, Rezvan says, was to put in place four sepsis nurse navigators. These nurses met with sepsis patients while they were in the hospital. They provided the patients with information in their native language, sought to ensure the patients understood the information, coordinated care among the patients’ clinical team, and helped address barriers to follow-up care upon discharge. “The goal was discharge readiness,” Rezvan explains.

After discharge, the nurses kept in regular contact with the patients and their families, ensuring they had the information and means needed to follow discharge instructions.

Rezvan says of those nurses, “They have a love for helping the underserved. They went above and beyond.”

The project achieved a 25% reduction in average length of stay and a 28% reduction in 30-day readmissions for the selected patient population.

Because of the success, the facility has made the interventions permanent.

Physicians and clinician champions at Providence Mission Hospital in Mission Viejo, California, discuss an education project that led to shorter hospitalizations and fewer readmissions for patients with limited English proficiency who had sepsis. The initiative was conceived and led by a participant in the health equity fellowship program offered by Providence St. Joseph Health.

Haggerson

Rezvan

CHA prepares to help ministry address challenges to providing spiritual care

By JULIE MINDA

As the U.S. health system has changed dramatically in recent years, so too has the spiritual care that is delivered in Catholic health systems and facilities. The role of the chaplains who deliver this type of care also has changed.

A 14-member committee made up primarily of CHA and Catholic health system leaders is overseeing a study of the changes and challenges for spiritual care providers, as well as future opportunities.

“We need health care leaders and others to have a better understanding of the strategic role of spiritual care in health care — we need a new framework for understanding spiritual care’s importance,” says Jill Fisk, CHA mission services director.

Fisk staffs the Spiritual/Pastoral Care Advisory Council that spearheaded a survey this summer. That council will oversee the development of a white paper on the essentiality of spiritual care in the ministry, which will complement the survey results. The association is partnering in the work with the National Association of Catholic Chaplains. NACC’s executive director, Erica Cohen Moore, is on the council.

Through this work, Catholic health care will be “putting a stake in the ground when it comes to having a foundational understanding of the need for spiritual care,” says council member Antonina M. Olszewski, Ascension vice president of spiritual care and mission integration.

“This work is important because this is who we are as Catholic health care — we are obligated to care for the whole person, and to do it well,” says Theresa Vithayathil Edmonson, vice president of spiritual health for Providence St. Joseph Health and another council member. “We need to make sure all our patients — and especially those who are poor and vulnerable — get the spiritual care interventions they need to flourish.”

CHA’s Spiritual/Pastoral Care Advisory Council

Fr. Lawrence X. Chellaian, senior vice president of mission integration, CHRISTUS Health

Vic Dippenaar, vice president, spiritual care, Trinity Health

Theresa Vithayathil Edmonson, vice president, spiritual care, Providence St. Joseph Health

Ruth Jandeska, vice president, spiritual health services, mission, Bon Secours Mercy Health

Erica Cohen Moore, executive director, National Association of Catholic Chaplains

Rev. Gregory Nealon, division director, mission and spiritual care, St. Joseph Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington

Nelu Nedelea, vice president, mission and ministry, Mercy, Chesterfield, Missouri

Antonina M. Olszewski, vice president of spiritual care, mission integration, Ascension

Mary J. Salm, vice president of mission and spiritual care, Hospital Sisters Health System

Timothy G. Serban, spiritual care consultant

Kelvin Thompson, system director of mission and spiritual care, PeaceHealth

Jill Fisk, director, mission services, CHA

Dennis Gonzales, senior director, mission innovation and integration, CHA

Karla Keppel, associate director, mission services, CHA

Integral to ministry’s mission

As delineated in the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services and as described in CHA’s Shared Statement of Identity for the Catholic Health Ministry, Catholic health care provides holistic and sacramental care to patients, and it supports the well-being of its staff. Spiritual care staff — primarily chaplains — are essential to ensuring that ministry systems and facilities pursue these aims effectively, say advisory council members.

Edmonson adds that the spiritual care discipline is key to advancing the quintuple aim framework for optimizing health care system performance, not just narrowly defined spiritual care goals. The framework strives to reduce costs, improve population health and patient experience, advance health equity and attend to health care team well-being.

Fisk says CHA long has worked to promote a comprehensive understanding of spiritual care and chaplaincy, why they are essential to the ministry’s mission, and how to prioritize them. The association has developed a library of resources and offers programming in this area. Related resources include the “Essential Services of Spiritual Care” overview for acute care settings and another for continuing care settings as well as the publication “Standard Work and Staffing Tool for Acute Care Settings.”

Also, CHA is working with NACC to develop new career pathways and pipelines for the chaplain role. This work is parallel to CHA’s work on a Faithfully Forward initiative for building a pipeline of ethics and mission leaders.

CHA has created a video series on what a chaplain is and why that role is critically important. The videos will be released soon and can be used for awareness-building among ministry colleagues and those considering the profession of health care chaplaincy.

New landscape

While the existing resources and programming from CHA and NACC remain vitally important, spiritual care experts say recent changes make it necessary to reassess the state of spiritual care and chaplaincy, how the ministry should respond, and how CHA and NACC can support this response.

Edmonson notes that in the past hospital leaders thought of chaplains primarily as providers of bedside spiritual care to patients and their families in acute care settings. Now, she says, leadership is seeing the value of involving chaplains in aspects of health care beyond the bedside. Chaplains are working across the continuum of care, including outpatient, long-term care and virtual care settings. They tend not just to patients and families but also to staff who can struggle with the toll of caregiving.

Olszewski says health care leadership is starting to recognize that spiritual care and chaplaincy can strategically support their facilities’ top priorities, including improv-

ing patient care and experience, preventing violence against staff and improving staff retention.

Moore adds that other changes involve who is serving in spiritual care and who is being served. While men and women religious used to occupy most chaplain roles, it’s now mainly laity with diverse backgrounds. They have not been formed in the same way as clergy. And chaplains are providing spiritual care to populations with a wide range of spiritual backgrounds, whereas religiosity of patients was more homogenous in the past.

Fisk adds that even as spiritual care and the chaplain role become more complex, there is a lack of qualified candidates for chaplain and spiritual care leadership positions.

Need for visibility

Moore notes that there also is increased pressure on health care executives to make cuts to save money. Olszewski says in this environment, “it could be seen as easy to cut spiritual care services because they’re considered to be non-revenue generating.”

She says, “It’s an issue of visibility. We need to raise up the essentiality of spiritual care and we need to cement the idea that spiritual care creates value in health care.”

The survey that CHA conducted starting in July went to professional health care chaplains, chaplains serving in leadership roles, leaders overseeing spiritual care departments and human resource leaders. The survey is expected to illuminate innovations and issues that spiritual care is facing and other concerns.

Moore says, “If we want to remain relevant to the people we serve, we need to transform as their needs change. With this work we’re doing, CHA is providing a roadmap or a pathway for change — where we need to head, what resources are needed, being honest and transparent about the obstacles we face.”

Part of clinical team

Fisk, Edmonson, Olszewski and Moore say they anticipate the work will build awareness of the vital importance of spiritual care and chaplaincy to the Catholic health mission. They think the work will shed light on the key role spiritual care providers play on the clinical team and the value they add to the health care ecosystem.

The work likely will also make the case for continued emphasis on metrics to document the value of spiritual care providers. As part of this push toward greater transparency, there likely will need to be a continued prioritization of standardizing spiritual care work, and ensuring all those who practice it have the best training and are fully certified.

Olszewski says spiritual care team members “are a largely untapped resource to support all the needs” of health systems and facilities. “And, I personally believe that we cannot treat physical health without addressing the mind and the spirit.”

This is the final article in a series on how CHA’s sponsorship and mission services department is reimagining its work.

jminda@chausa.org

The Catholic Health Association invites you to experience Finding Hope in the Darkness — a beautifully curated daily Advent resource designed to inspire prayer, reflection and connection throughout this sacred season.

Edmonson

Olszewski

At Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital in Spokane, Washington, Chaplain Lin Preiss comforts a young patient before surgery. Sacred Heart is part of Providence St. Joseph Health.

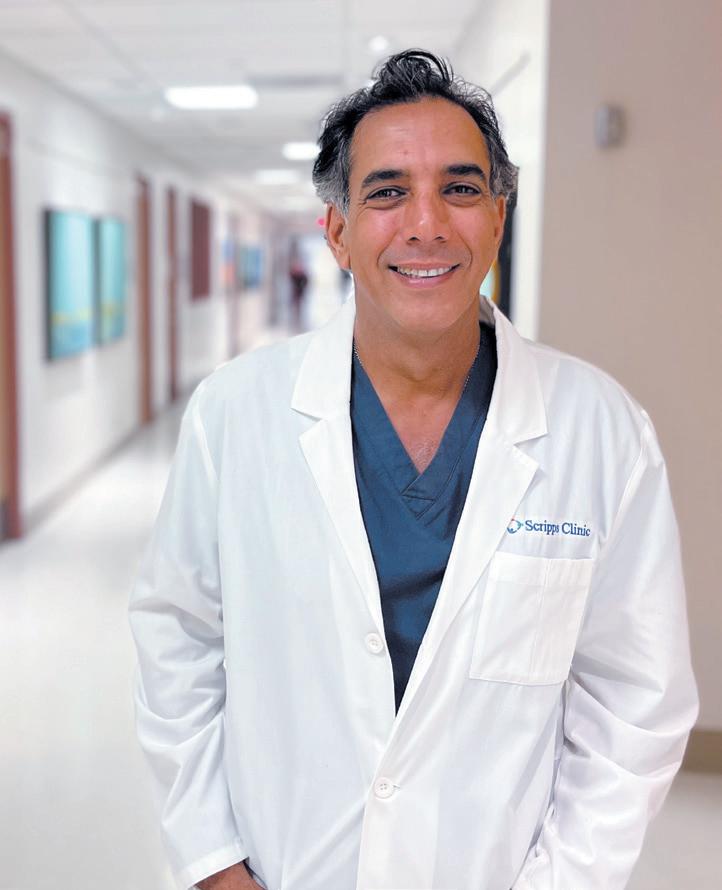

Scripps Health launches Fourth Trimester program for high-risk mothers

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Like many doctors around the country, over the last several years Dr. Sean Daneshmand has seen more women with complicated pregnancies, such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, or with chronic medical issues including high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. More expectant mothers are obese or severely depressed.

Daneshmand, medical director for the Scripps Clinic Maternal-Fetal Medicine Program for San Diego-based Scripps Health, started the Fourth Trimester Continuum of Care program last fall to address the needs of these women.

The program is designed to identify high-risk mothers before they give birth and help them get the care they need shortly after they deliver — in the “fourth trimester.” In 2024, about 9,000 babies were delivered at Scripps Health’s hospitals across San Diego County. Two of its five hospital campuses, Scripps Mercy Hospital San Diego and Scripps Mercy Hospital Chula Vista, are Catholic.

“New moms, as you know, always put their baby’s health above their own,” he said. “And we need to make sure they take care of themselves in order to be there for their child. We know that women truly are the CEOs of our community. They really are the centerpiece of the family and society. So we need to go the extra miles to take special care of them.”

Worsening outcomes

Daneshmand cited a Blue Cross Blue Shield report that says pregnancy complications increased by more than 16% from 2014 to 2018. The report says that

High school students get ‘raw’ experience of what it’s like to be a clinician through Holy Name career program

By JULIE MINDA

When Alexis Freedman applied for the Holy Name Medical Center Healthcare Careers Discovery Program, she knew she’d get exposure to the goings-on at the 361bed hospital in northern New Jersey. But when she actually took part in the weeklong session this summer, she was shocked at how much she, as a high school student, got to do.

“It was very hands-on, and I was so excited when I saw how raw the experience would be. It was beyond exciting,” says Freedman, a student at Montville Township High School in New Jersey.

In the simulation lab, Freedman gave injections and delivered the babies of lifelike manikins. She took the vitals of other high school students participating in the session. And she did mock job interviews with staff members of Holy Name Medical Center, which is in Teaneck, New Jersey.

Abigail Goldman, who participated in the more advanced session of the Healthcare Careers Discovery Program shortly after Freedman’s, was similarly amazed by the level of access. She rotated through multiple units of the hospital, shadowing clinicians. She even observed a gallbladder removal. “I saw the teamwork and conversation between the nurses and doctors and others,” she says. Goldman is in her junior

among pregnant women, there has also been a 35% increase in major depression, a 31% increase in hypertension, and a 28% increase in Type II diabetes.

In the United States, pregnancy-related deaths continue to rise, with one 2025 study citing cardiovascular disease as the leading cause, accounting for more than 20% of maternal deaths. Another study says the prevalence of chronic hypertension in pregnancy doubled from 2007 to 2021.

“Unfortunately, I don’t think the trend is leading towards a healthier society, whether it’s activity, whether it’s diet,” he said. “But we know that physical, preexisting conditions before pregnancy have been on the rise.”

Building bridges

In the Fourth Trimester program, when clinicians identify risk factors in a pregnant woman, they flag them in the patient’s

chart, Daneshmand explained. After the woman delivers her baby, an automated message goes to her primary care team to schedule an appointment, in addition to her two usual postpartum visits with her obstetrician/gynecologist.

“Rather than relying on the moms to initiate the appointment, we make sure that we’re proactive with follow-up with their primary care physician soon after the delivery,” he said.

Also, at the baby’s pediatric visits, the pediatrician is prompted to ask the mothers about their health as well.

“Essentially, we’re building a bridge to get patients care,” he said. “And this includes a close collaboration between maternalfetal medicine, primary care, administrative leadership and obviously others.”

While it’s too early to analyze the data collected so far from the program, Daneshmand personally knows patients with severe hypertension who have benefited.

A broader effort

The Fourth Trimester Continuum of Care supplements other Scripps Health initiatives to help pregnant mothers. In recent years the system has added:

Two dedicated patient navigators who work with women in high-risk pregnancies, which Daneshmand said is rare in a maternal-fetal medicine specialty. The navigators help coordinate tests and appointments and answer patient questions. “It makes sense to have something like this, because stress has consequences that we’re not aware of,” he said. “We still don’t understand the biological effects of stress, not only on the mother herself, but also on the child. So we’re doing everything we can to make sure that this mom has someone to

talk to, and there’s someone in charge who is collaborating and making sure that those questions are addressed.”

A neonatal intensive care unit partnership between Scripps and Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. The partnership has been in place since the mid-1990s. If a mother has a complicated pregnancy, the baby often will spend time in the NICU at Rady. “This is very important to the families, because they receive specialized expertise at Rady Children’s, with Rady Children’s experts,” Daneshmand said.

Close partnerships with local community health clinics, specifically those run by San Ysidro Health, a federally qualified health center that has more than 50 clinics and program sites across San Diego County. The clinics serve a largely Hispanic community, and Scripps provides maternalfetal medicine services to those patients, including care for high-risk pregnancies. “This improves equity, obviously expanding these services and access to these moms,” Daneshmand said.

Daneshmand hopes the initiatives can serve as a model for other health systems. He’s passionate about his work because of the connections he makes with his patients during pregnancy, a very “raw and real” experience for mothers. Their unconditional love for their child starts the minute they see the heartbeat, he said.

“And regardless of where we come from, our political views, all the differences that people see in the world, all of us love our children the same way. We all want the best for our children, and that’s what unites us,” he said. “For us, it’s how do we make sure that society is better as a whole? We have to focus on moms.”

vhahn@chausa.org

certification.

The students in the advanced session spend more time on the units shadowing clinicians and, as circumstances allow, can observe clinical care delivery, such as the gallbladder removal that Goldman watched.

Holy Name accepts applications for the program between January and March before the sessions that run in midsummer. Hundreds apply. This year, 24 students were chosen for each of the two sessions. The program costs $875 to attend. Holy Name offers scholarships for students who cannot afford the cost.

‘Bright and eager’

Igniting the career passions of students like Freedman and Goldman is exactly what Holy Name leadership had in mind in 2015 when it began the Healthcare Careers Discovery Program. The summer program gives high school students who are considering a medical career a wide range of experiences at the hospital, including shadowing clinicians, rotating through medical units, attending a panel discussion with clinicians, practicing interview and job-seeking skills, and learning clinical procedures in the simulation lab.

Holy Name is one of many Catholic hospitals across the nation with similar programs that offer career-building opportunities to students.

Matthew Kostelnik, the lead simulation specialist at Holy Name, says with its program, the hospital is “taking a stance, preparing for the future workforce shortages that are coming with nurses and physi-

cians” and other clinicians.

“The students leave here empowered,” he says.

Experiential learning

Kostelnik says the program began when Holy Name leaders identified a gap in the number of candidates available to fill clinical positions at the hospital.

While the program has evolved over the years, the current iteration features the initial program for younger students and the advanced program for older students who have attended the basic program. Both the basic and advanced program include a combination of classroom and simulation learning experiences and exposure to the hospital environment. Some of what the students learn is basic life support, labor and delivery practices, airway intubation and suturing. They can earn first aid

According to a 2024 report from the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, which is affiliated with the Health Resources and Services Administration, “as of June 14, 2024, approximately 75 million people live in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area.” The report also said that “across all physician specialties in the United States, there is a projected shortage of 187,130 full-time equivalent physicians in 2037.” According to a Health Workforce Analysis published by the center in 2022, there was a projected shortage of 63,720 full-time nurses in 2030. That report said New Jersey was among 10 states with the largest projected shortages.

Kostelnik says it has been heartening to see hundreds of high school students moving through the program, “bright and eager,” and enthusiastic about careers in medicine — although it’s also a good way for students to discover early whether it is perhaps not the career for them after all.

Kostelnik says graduates of the program have returned years later to work at Holy Name.

He says the program builds confidence in the students. “They walk away being comfortable with whatever situation we put them in,” he says.

jminda@chausa.org

Daneshmand

Freedman

Goldman

Ben Mazza Jr., a nurse, simulation educator and manager of emergency preparedness training, teaches IV skills to students in the Holy Name Medical Center Healthcare Careers Discovery Program. year at Cresskill High School in Cresskill, New Jersey.

Kostelnik

Little acts that make a difference: Volunteer Angels carry on tradition of service

By DALE SINGER

Don’t try to tell Agnes Cannella there’s no such thing as angels. She knows better. Cannella is director of mission services at St. Joseph’s/Candler in Savannah, Georgia, where she has led the Angels of Mercy for five years. Named in honor of the Sisters of Mercy who started what was then St. Joseph’s Hospital and their nearly 200-year mission of service to those in need in coastal Georgia, the volunteers, primarily staff members, undertake projects that promote wellness and assist underserved residents.

With projects at least once a month, from bed building to a fall festival and a program with the Salvation Army, the Angels have a busy schedule.

Cannella sees the Angels’ community outreach work as an extension of the mission of the health system that includes two anchor hospitals and serves parts of Georgia and South Carolina. Friends and family members of staff are invited to join the Angels’ projects. Anywhere from five to 50 volunteers might be needed.

Soul On Fire

From page 1

O’Leary has built a career as an inspirational speaker since the accident, which occurred when he lit a can of gasoline on fire in his suburban St. Louis garage in January 1987. He spent five months in the hospital, then known as St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, and endured several surgeries. The movie spreads a message of hope, resilience and faith.

“Our hope today, family and friends, is when the lights go back up, that the room is filled with hope and faith and applause, not for what I did, but for what God does in broken hearts,” O’Leary told a crowd who gathered in St. Louis this summer for a screening of the film. “I think as you see this film play up, you’ll see a whole bunch of others who stepped alongside a desperate family and a broken-down little boy and reminded him that, in spite of what he felt and thought, that he was worthy, which is a message that I think our world needs today.”

Mercy’s central role

In an interview, O’Leary said: “Catholic health care plays a central role in this little boy’s survival.”

Mercy Hospital St. Louis is part of Chesterfield, Missouri-based Mercy, a health system with facilities in Arkansas, Kansas, Illinois, Missouri and Oklahoma.

O’Leary pointed to a scene in the movie where his mother, Susan, prays in the Mercy hospital’s chapel. “Mom is praying and Dad comes in, the stained glass is just radiating light, and Mom’s sad, but there’s hope in this,” he said. “There’s something just beautiful about hope in the midst of struggle, and Catholic organizations can claim that like no others can.”

The film was shot in St. Louis, and most hospital scenes were filmed in a former hospital on the Saint Louis University campus. Mercy branding is seen on the hospital walls and in exterior shots. Images of stained-glass windows from four Mercy chapels were edited into the chapel scene in postproduction, O’Leary said.

Though the Mercy caregivers who tended to O’Leary have moved on or since retired, many are depicted in the film and have stayed in touch with the O’Learys. Many friends and family members appeared in the film as extras, and O’Leary himself makes a cameo.

Dr. Vatche Ayvazian was the primary burn doctor who is depicted in the film.

The Angels got their start during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, which required a large volunteer corps to handle the influx of international visitors. As a major local employer, the health system accepted an invitation to take part.

“As a continuation from that, we just decided this was a great way for new coworkers to get together and meet each other

In one scene, which happened in real life, Ayvazian quizzes a group of young doctors at the boy’s bedside, asking who is the most important person to the boy’s recovery. One guesses the doctor; another guesses the boy. Ayvazian says no and points out the man cleaning the room. Since that worker was keeping the room clean and germ free, he is critically important to the boy’s survival, Ayvazian tells the doctors.

“I’m going to have to ask for a raise,” the worker says in the film.

In early January, O’Leary drove six hours to Cincinnati to surprise Ayvazian for his 90th birthday.

Nurse Roy Whitehorn is also portrayed in the film. Scenes show him urging a bandaged O’Leary to walk. “Boy, you are gonna walk again,” he says. “And I’ll walk with you.”

O’Leary reunited with Whitehorn as an adult, and the reunion is depicted in the film.

Continued relationships

Sue Hornof Rodrigues was one of O’Leary’s main caretakers, and she and other nurses who cared for him play nurses in the movie. They don’t have speaking roles, but during the filming they wrapped the actor who played young O’Leary, James McCracken, in bandages for the hospital scenes. They advised crew members on things like the accurate colors of scrubs or paper gowns.

“It brought back a lot of memories, and it was interesting to see characters they picked for nurse Roy or the parents,”

while also living our mission,” Cannella recalled.

Meredith Scaccia, the health system’s director of women’s and children’s services, said such enthusiasm can be contagious. “We’re all very passionate,” she said. “We’re just trying to make a little bit of a difference, one day at a time.”

Life lessons

Creativity is important when the Angels are looking for projects — and surprises also play a role. For example, Cannella said helping at a free foot care clinic taught some of the volunteers a valuable lesson. The clinic was held in a central location, on a bus route, with a population generally served by other hospital programs.

Some of the people who came to the clinic needed special shoes that addressed issues caused by diabetes. But some of the volunteers didn’t understand that the cost put those shoes out of reach for some people.

“We were able to buy certificates that they gave to some of the clients that allowed them to buy diabetic shoes,” Cannella said.

She added: “Bringing somebody into a new world that they may not be aware of — and seeing that someone’s actual condition

Rodrigues said. “I think it was hard for John to see. It was more inspiring for me to realize what he actually went through and what he brought out of it.”

She has stayed in touch with the family over the years. Shortly after O’Leary was released from the hospital, Rodrigues ran into his father, Denny, at a gas station. He paid for her gas, telling the cashier she helped save his son’s life. Years later, Rodrigues and other nurses attended John O’Leary’s wedding.

“It’s been tremendous to see what an impact John has had on people’s lives,” she said.

Cissy Condict was the head nurse in the St. John’s Mercy burn unit and was there the winter Saturday when O’Leary was brought in. “I’ll never forget it,” she said.

His father came into the room first, then his mother, who quickly got on the phone to ask family and friends to have Mass that evening dedicated to her son. “The waiting room was filling up with the people and priests, and pretty soon the priests are almost outnumbering the laypeople,” Condict said. “I thought, my goodness, who are these people?”

She has stayed in touch with the family over the years, even attending years of family Thanksgivings, and, this past June, the funeral of Denny O’Leary.

The family’s faith has inspired Condict and helping O’Leary has helped her. “You become a better person because he’s a better person,” she said. “It was a miracle in many ways, but it was also a real tribute — I was so proud of the burn unit and how we

is not through any fault of their own — that really helped them.”

Measuring success

Another successful project for the Angels has been working with the organization Sleep in Heavenly Peace, which assembles and donates beds for children in need ages 3 to 17. The Angels of Mercy volunteer with Sleep in Heavenly Peace every year.

Cannella said the Angels contribute more than just sweat equity. “When it first started, if we needed any money, we were all chipping in ourselves,” she said.

Now the Angels accept financial assistance from colleagues who don’t have the time or the physical ability to join their projects. Using money from their annual campaign, the Angels this year donated $500 to Sleep in Heavenly Peace that went toward the cost of lumber.

How would Cannella measure whether the Angels of Mercy are a success? The answer, she says, is simple but basic.

“Health care is all about numbers,” Cannella said, “but when you’re doing service, is it really about numbers? You helped one person, and you touched one life by the activity that you did. You made a difference. That’s a success.”

Mercy screenings

Mercy is inviting caregivers to screenings across its markets and is working on ways to connect the story to caregivers throughout the upcoming year, Barbara Miller Riesen, the system’s vice president of marketing strategy, said.

“The portrayal in this film of Mercy and our remarkable caregivers is completely authentic, especially how they never give up,” she said. “Our role is to come alongside the patient and help them endure, recover and heal.

“We’re so thankful that we were part of his miraculous story, and that we’ve continued to be a part of his journey to fullness of life.”

O’Leary went through years of surgeries and therapies with Mercy providers. Through the generosity of health care organizations, he also attended camps with other young burn survivors.

O’Leary has since given talks for groups at Mercy, SSM Health, Ascension and other Catholic health care ministries. He is also scheduled to speak at the 2026 CHA Assembly. He and his wife, Beth, have a daughter and three sons and live in suburban St. Louis.

“I think we in Catholic health care can remind our people that regardless of their job, you are the hands and the feet of a living Christ,” O’Leary said. “Do that well, and watch how you change the lives of those you encounter.” vhahn@chausa.org

John O’Leary endured several surgeries as a boy to help him heal and use his hands again. His life is depicted in Soul On Fire. all just worked as a real team.”

Cannella

Angels of Mercy volunteers from St. Joseph’s/ Candler assemble beds for children in need in partnership with Sleep In Heavenly Peace.

Scripps Health security lead focuses on reducing ‘opportunities for violence’

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

When Scripps Health experienced a cyberattack in 2021, supervisory FBI special agent Todd Walbridge was part of the investigation. He got to know the organization and Scripps President and CEO Chris Van Gorder, a former police officer himself.

In October 2023, when Walbridge retired from the FBI, Van Gorder tapped him to help the Southern California health care system full time.

Walbridge is now the senior director for safety and security for Scripps. Van Gorder initiated the Hospital Violence Task Force in San Diego, a group that started in late 2023 and includes leaders from hospitals and health systems as well as law enforcement agencies and the San Diego County District Attorney’s Office.

Walbridge sits on the task force and focuses on how to reduce violence within the Scripps Health system. Two of its five hospital campuses, Scripps Mercy Hospital San Diego, and Scripps Mercy Hospital Chula Vista, are Catholic.

Across the country, violence in hospitals has “significantly increased” over the past decade, with rising rates of assault, homicide, suicide and firearm incidents,

Panic buttons

From page 1

this new technology, there is more peace of mind for our staff. They can get help when they need it. They’re not by themselves. Someone has their back.”

‘It really breaks our heart’

According to a 2024 National Nurses United report, 81.6% of nurses experienced some form of workplace violence in the year prior to the study, and 36.2% had been physically hit at work.

Pahl says, “Nurses and caregivers go into this profession to take care of folks, and it really breaks our heart to hear of any caregiver, any provider, and really anybody in our facilities or medical group practices being harmed or injured either emotionally or physically.”

Bon Secours Mercy Health began around 2023 exploring solutions beyond its existing protective measures. It put out a request for proposals for wearable protective devices, technology that Pahl says is being used increasingly in health care facilities in the U.S. After research and a pilot program at two locations, the health system signed on with 911Cellular.

Securing the scene

Pahl says the technology is “relatively inexpensive,” especially given the importance of the investment. As Jeff Dempsey, president of Mercy Health — St. Vincent Medical Center, says in a press release about the panic badges, “This investment is one more way we’re creating a secure, supportive environment where our teams can thrive, and our patients can heal.” St. Vincent Medical Center, a Bon Secours Mercy Health hospital in Toledo, Ohio, is deploying the panic buttons into early October.

Bon Secours Mercy Health is funding the technology through a well-being grant connected with the system’s associate health plan. The investment “reflects the ministry’s larger commitment to associate safety, wellness and engagement,” the release says. 911Cellular staff work with technology and security departments to connect the duress badge system into each facility’s

according to the American Hospital Association. These incidents were further exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. The violence comes at a cost: the AHA estimates the price to prevent violence and pay related expenses was $18.27 billion in 2023.

Walbridge reports that Scripps Health reduced workplace violence injuries by 31% last year compared to 2023. Calls for “code 55,” or violence in action, dropped 22%. Calls for Behavioral Urgent Response Teams went down 14%.

Catholic Health World spoke with Walbridge about the system’s approach to reducing violence and encouraging communication. His answers have been edited for length and clarity.

How did you bring your FBI experience to health care?

As a SWAT team leader, my specialty in planning operations was: How do we bring a very violent person into custody safely? And the underlying tactic is: How do we reduce opportunities for violence? The opportunities for violence have driven our planning and preparation and reduction of workplace violence. Here at Scripps Health, I oversee all five hospital campuses, all 30-plus clinics, plus our corporate buildings. We’ve been making a lot of changes to how we do things, everything from the structure of our security program,

to empowering our staff on what a correct response looks like for behavioral response versus a medical response and being able to delineate that difference and respond differently than they have in the past.

You have all those buildings, doors, people and opportunities. Where do you even start?

What it starts with is level-setting my security team and then reaching out as frequently as I can to all staff members. One of the things I’ve passed on to our staff is very similar to what we did on our SWAT teams, which is, protect yourself; protect your buddy. I had to explain that no, it’s not selfish, because if you don’t get injured, that means you’re here today and tomorrow and the next day to not only care for our patients, but also so that the load is not shifted to the rest of your co-workers. They had never been told about the importance they have in the plan, and how important not being injured is to the organization from an operational standpoint, from a human being standpoint, and even a financial standpoint. The bottom line is also impacted by violence injuries that cost organizations money.

How have you trained your staff?

Our security (team) has been trained in de-escalations. We have a full day of train-

WiFi network and configure the technology to send wireless signals when activated. Those wireless signals let campus security officers — and any other designated protectors — locate the distressed employee. Each facility chooses who will get the signal; most facilities alert a house supervisor or charge nurse in addition to campus security. Smaller facilities likely also summon local police.

When responders arrive after an alert, they secure the scene and then determine whether additional team members need to be called, such as behavioral health experts, social workers, spiritual care staff or local police.

Discreet technology

Each Bon Secours Mercy Health facility that adds the technology can specify the number of badges they need. Employees put on their badge when they begin their shift then return it for their replacement to use after shift change.

Pahl says education and training have been essential to the rollout of the badges. Her team secured leadership buy-in and has been engaging each facility to start acclimating the staff to the technology

ing on what’s called AVADE, which focuses on health care. We are doing more advanced training on behavioral care issues. I write an article at least once or twice a month and work with our marketing department, and we continue to broadcast what our messaging is about. We just created a video last week with our chief medical officer and our CEO called “10 Things You Can Do to Be Safer at Work.” Lesson number one is mindset. Be mentally prepared. If you’ve never envisioned violence, then you’re going to struggle to understand it when it’s happening before you.

Scan to read an extended version of this story.

before they use it. A mandatory educational video for staff explains how the panic buttons work, the need to ensure they are sufficiently charged, and the need to tap twice when activating the device. Each facility will conduct monthly drills to practice using the technology.

Katy Stringfellow is chief nursing officer at St. Vincent Medical Center. That facility was so enthusiastic about the wearable duress badges it used its own grant dollars to expand the program throughout the facility, not just at units included in the systemwide rollout. St. Vincent Medical Center is deploying 300 badges by mid-October. Stringfellow notes that upfront trustbuilding was needed before the badge rollout because some staff feared that the devices would track their movements. She and her team have reassured staff that the device only tracks their location when activated.

Stringfellow says the devices are discreet, so unlike some ways of hailing help, the double-tap of the button likely will not further escalate a brewing situation.

Tell me more about the task force. The big thing that this task force has brought is the education to our staff that, unlike television, if you file charges, it doesn’t mean you’re going to be on the stand in court, testifying. The district attorney’s office has prosecuted over 40 health care cases in San Diego, which includes Scripps and others, since the task force started. The defendants all pled guilty, so there’s been no need to testify in court, which is very powerful for our people. vhahn@chausa.org

Pahl says even though the technology has not yet been used long, it is already proving its value. An employee at a Bon Secours Mercy Health site recently was cornered in a room by a patient and family, and tension was growing. After that staff member activated the device, a security officer quickly arrived to de-escalate the situation.

Broader efforts

Pahl says employee and patient safety and security are of utmost importance to Bon Secours Mercy Health, and so there are numerous safety approaches, practices and programs already in place or coming soon. The wearable devices “are one additional tool in the toolbox,” she says.

Bon Secours Mercy Health has a systemlevel violence prevention committee, and each facility has its own committee with representation from frontline workers. This group shares experiences and best practices in the hopes of making their campuses safer.

Additionally, all patient-facing staff receive ongoing training in de-escalation. Also, many facilities already were using stationary duress buttons — normally located in a discreet location. All have code systems for quickly calling a multidisciplinary team of responders. At St. Vincent Medical Center, calling a certain code on the overhead address system brings security, the charge nurse, a hospital social worker and a chaplain to de-escalate a situation.

In addition, several Bon Secours Mercy Health facilities are using grant dollars to install weapon-detection systems powered by artificial intelligence, similar to what many concert venues use.

Pahl says Bon Secours Mercy Health facilities also are going well upstream of potential violent incidents by promoting spiritual and behavioral health and wellbeing, so staff and patients alike are wellgrounded before a potentially triggering situation arises.

Pahl says, “Mental and spiritual health are so important for our patients and staff … and it’s a true collaboration among disciplines to support great mental health for our staff and great behavioral health for our patients.”

Stringfellow says, “It’s about staying one step ahead — it’s about prevention.” jminda@chausa.org

Walbridge

Pahl

Nurses Angela Murphy and Dylan Cox of Mercy Health — St. Vincent Medical Center in Toledo, Ohio, examine a wearable panic button. Bon Secours Mercy Health is providing the devices to some units at all of its hospitals.

Stringfellow

Child care grant program

Providence Seaside Hospital is in Clatsop County. The collaborative has used public and private dollars to issue grants to stabilize and expand child care providers in the community, teach them to run their businesses more smartly, train their staff and provide scholarships to parents to subsidize the cost of the care.

In five years, the collaborative has succeeded in expanding child care options, but much work remains for future grant cycles.

“There’s an economic boost when you no longer have families at risk of not having child care,” said Amanda Shelley, a child care provider who used grant dollars from the collaborative to establish the Magical Moments In-Home Child Care and Play School in Seaside, Oregon.

Shining a spotlight

Eva Manderson, director of Northwest Regional Child Care Resource and Referral, said a lack of child care long has been an issue in Northwest Oregon, but the pandemic “shone a spotlight” on the problem.

According to a 2022 study by Oregon State University, most Oregon counties are child care deserts for infants and toddlers, and half of the counties in the state are deserts for preschoolers. A child care desert is a county where there is just one licensed child care slot available for every three or more children.

Manderson explained that when COVID hit, local governmental agencies in Clatsop County closed all regularly operating child care programs. The programs were allowed to reopen as emergency child care facilities if they could commit to different rules and standards. “Many programs took that time to close permanently due to the rising standards needed to stay operational and in compliance,” Manderson said.

She added that many long-time child care providers retired or changed professions around that time.

Dan Gaffney, a retired school administrator who helped lead the collaborative, said in the early days of the pandemic, the child care strain became a crisis in Clatsop County. The community was at risk of losing essential first responders and medical personnel because they had no child care available. Unlicensed providers opened to fill the gap, parents sought the help of relatives, and some people posted pleas for help on Facebook. For most families, there were no ideal options.

Manderson said the situation revealed that “the child care industry exists in a fragile balance.”

At the start of the pandemic, Shelley had about a decade of child care experience. She was working at a child care facility and had a baby of her own. She saw that she and others were locked out of the market when they sought child care for their own children because of the high cost.

She added that, as is common nationwide, providers in Clatsop County were having trouble recruiting and keeping good staff because they couldn’t pay much on the low margins of a small child care facility. “You could get paid more at Taco Bell,” Shelley said.

Stabilization

Gaffney had retired pre-pandemic after decades of work in education in Northwest Oregon and had been volunteering his expertise locally to address early childhood education shortfalls. He connected with other community leaders in the early days of the pandemic to address concerns about the severe lack of child care.

This group formed the collaborative of more than a dozen local leaders, includ-

“ Local businesses have been getting interested in our work because they realize you don’t have reliable employees if you don’t have child care available.”

— Eva Manderson

ing some associated with the county, the schools, health care and early childhood care and education.

They canvassed the community to assess the situation and then came up with the solution of stabilizing and expanding the child care facilities through grant-making. The group has secured about $1 million in funds since 2020. Providence Oregon contributed $200,000 and has provided in-kind support through data analysis by its Center for Outcomes Research and Education.

The Clatsop Child Care Retention and Expansion Program has completed four grant-giving rounds since 2021. The grants have been used to establish or stabilize child care, coach providers in good operating practices, improve the quality of facilities and subsidize the cost of care for parents. In August, the collaborative’s advisory board approved the fifth grant round, which will allot $155,000 to nine child care providers, $141,660 for tuition for families, and $13,500 for professional development for teachers. Child care center owners who receive the grants will take part in courses on how best to run their businesses.

Seeking supporters

The expansion program has added more than 300 child care slots in the county. Thanks to this program — as well as some other local efforts that government entities undertook — the community no longer is a child care desert for preschoolers. It is still one for infants and toddlers. The Clatsop Child Care Retention and Expansion Program has made expanding infant and toddler care a focus.

The collaborative is looking at how to improve and build upon its work. It is exploring how best to secure “micro donations” from local businesses to fund continued expansion.

“Local businesses have been getting interested in our work because they realize you don’t have reliable employees if you don’t have child care available,” Manderson said.

Capacity-building

Joseph Ichter, senior director of community health investment for Providence Oregon, said a key reason Providence decided to support the expansion program is that economic security is a top priority identified in Providence Seaside’s community

health improvement plans, and child care availability and affordability is an aspect of economic security. Also, Providence saw promise in the collaborative’s early success and wanted to accelerate that progress.

Ichter noted that child care operators who receive grant funding from the program agree to provide data to the Clatsop Child Care Retention and Expansion Program. That program is working with Providence’s Center for Outcomes Research and Education to process the data and analyze it to figure out how to continually improve the child care providers’ work and to give them the opportunity to increase their capacity.

Fun in the sun

Shelley is one of nearly a dozen providers who have gotten grant funds to expand. She opened her in-home child care in 2024 when she received a grant. The grant enabled her to hire her partner as well as a friend to work at the child care, making it possible to care for more children.

Shelley said her child care prioritizes outdoor fun for the 16 kids she and her team take care of daily. The kids get lots of fresh

Providence supports child care expansion in Southern Oregon

Providence St. Joseph Health’s Oregon region not only helps to address child care availability in Northwest Oregon, it also supports similar efforts in Southern Oregon. Providence operates Providence Medford Medical Center in that area.

Providence awarded grants to the Southern Oregon Education Service District and the Southern Oregon Early Learning Hub in 2024 to:

Provide early childhood teachers with training on how best to provide care to kids with behavioral

Increase families’ access to quality child care

Build awareness of the benefits of a child care career

Subsidize families’ child care costs

Provide internships to people considering a career in early childhood education or child care

The overarching objective is to greatly increase the availability and quality of child care in Southern Oregon.

Providence has awarded $375,000 through three grant rounds to the service district and learning hub.

— JULIE MINDA

air, hands-on activity and sunshine. She said this has been a welcomed environment for families with kids who had trouble adjusting to more structured environments. She said without her child care, multiple families would have had nowhere to go. She also offers the flexibility needed by families with odd work schedules.

Gaffney said enabling providers like Shelley to expand is good for the community over time. “If you really want to retain and preserve quality of life in the U.S., you must invest in our kids,” he said, “or you can’t expect to have as positive a future as it could be.”

jminda@chausa.org

U.S. Postal Service

STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT, AND CIRCULATION (Required by 39 U.S.C. 3685)

1. Publication title: Catholic Health World

2. Publication number: 8756-4068

3. Filing date: Sept. 30, 2025

4. Issue frequency: Monthly

5. No.

Gaffney

Manderson

Ichter

Children enjoy outdoor fun at the Magical Moments In-Home Child Care and Play School in Seaside, Oregon. Amanda Shelley used grant dollars to open the child care.

ArchCare nursing home adds child day care to attract staff, meet community need

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

A nursing home and rehabilitation center in the Hudson Valley of New York state opened a day care center on its campus to tackle a big challenge: attracting and retaining employees in an area where child care is hard to find.

In June, the Ferncliff Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center in Rhinebeck opened the Honeybee Child Care Center in an underutilized wing. Ferncliff is run by ArchCare, the continuing care community of the Archdiocese of New York.

Ferncliff staffers, 76% of whom are women in need of child care services, get 25% off tuition at the day care, which has space for 41 infants, toddlers and preschool-age children. As of early August, the center had nine enrolled, about half of them children of Ferncliff staff, and expected more as word got out.

“A couple of days ago, we had a CNA with a young child come in and apply, tour the day care center, and accepted the full-time position immediately,” said Dorice Tokarz, administrator of the nursing home.

“She’s absolutely thrilled.”

Ferncliff isn’t the only health care provider adding convenient child care as a workforce enticement and community service. Mercy Health-St. Rita’s Medical Center in Lima, Ohio, opened a day care, Mercy Tots, in July. The center with room for 108 children is in a building donated to Mercy Health-St. Rita’s, part of Bon Secours Mercy Health, just two blocks from the hospital. The child care opened to children of employees before welcoming the children of other families.

“We know access to safe, reliable child care is critical for working families, and we are thrilled to be able to open Mercy Tots to our greater Lima community,” Aimee Kuhlman, director of Mercy Tots, said in a news release.

A unique setting

Ferncliff is planning a grand opening of its child care this month. Tokarz said staff members can visit their children at the day care as time permits. “They feel very secure that their children are on-site so they can go see them. It’s nothing but positive reviews,” she said.

Jason Hutchens, chief operating officer of ArchCare, said the ministry tries to meet the needs of the community it serves. By

opening the day care, ArchCare can “provide another level of service while also helping our own” care providers, he said.

Rhinebeck is about 50 miles south of Albany and 100 miles north of New York City. Earlier this year, the New York comptroller released a report that said about 55% of census tracts in the mid-Hudson region are considered child care deserts, with at least three children under age 5 for each available slot among registered homebased providers or centers.

It has been difficult to staff the nursing home since the pandemic, and when a day care center nearby closed recently, ArchCare administrators knew that could exacerbate the situation.

Honeybee Child Care Corp. runs centers

in Poughkeepsie and Wappingers Falls, just south of Rhinebeck. About two years ago, ArchCare administrators asked Kathy Evans, Honeybee’s chief financial officer, if she would be interested in opening a center at Ferncliff. She said that would be financially difficult for her company. About a year later, ArchCare approached her again and proposed building the center. Evans worked with ArchCare to get the proper approvals and to plan and equip the space. Until this month, ArchCare let Honeybee use the space rent-free.

The center has an outside entrance separate from Ferncliff’s and an outdoor playground in a tree-filled setting. “It really is state-of-the-art,” Tokarz said.

Uniting the generations

Ferncliff has a 66-bed Huntington’s disease unit and a 37-bed, Montessori-based advanced memory care unit. Once more children are enrolled in the day care, Ferncliff and Honeybee plan to do intergenerational programming such as sing-alongs, crafts and holiday celebrations. A large auditorium at Ferncliff will make it easy to bring the groups together, Tokarz said.

Evans is excited about the possibilities at Ferncliff. The Honeybee day care in Poughkeepsie is next door to a nursing home and the children there regularly engage with the residents. “The kids call them the grandmas and the grandpas,” she said.

Many of those “grandmas and grandpas” get few visitors, Evans pointed out. “When they see the kids, they just brighten up,” she said. “It brings that light to them, that energy to them.”

vhahn@chausa.org

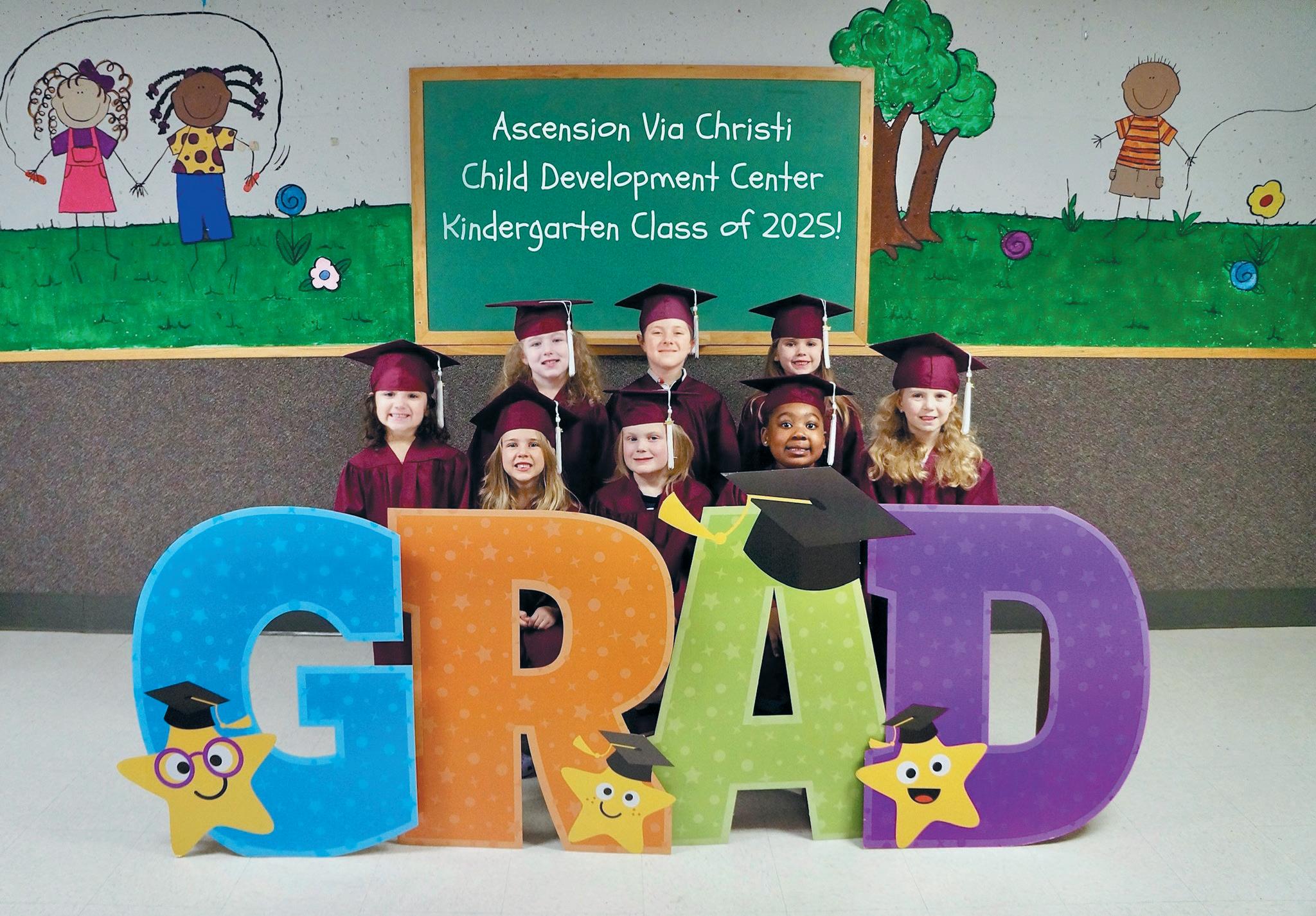

Day care on Ascension campus celebrates 45 years of serving employee families

By VALERIE SCHREMP HAHN

Jane Swindle and Terri Wittrig admit they do not remember all the faces. But after 45 years at the Child Development Center at Ascension Via Christi St. Francis Hospital in Wichita, Kansas, it’s surprising how many adult faces they recognize as the toddlers or preschoolers they cared for long ago.

“We were going through pictures of all these years, and everyone’s like, ‘Jane, who is this?’” Swindle said. “And I’m like, that’s so-and-so, that’s so-and-so.”

The women both began working at the day care center for the children of Ascension employees when it opened in 1980: Swindle from the very beginning, and Wittrig a few months later. They were both 19 and eager to start careers in child care. Swindle worked for years as a teacher for 2-yearolds, and now she’s the center’s manager. Wittrig is a part-time teacher of 2-year-olds.

The Sisters of the Sorrowful Mother, who founded the hospital in 1889, thought it was important for nurses and other employees to have somewhere for their children to be cared for while they worked, Swindle said.

The hospital opened the center on the first floor of an apartment building next to the hospital, with space for 100 children.

“They were over here all the time,” said Swindle of the sisters. “They backed us 100%.”