Glacial Channel, Southeastern

Canyon was formed

Glacial Channel, Southeastern

Canyon was formed

SARAH SCHULTZ, TECHNICAL EDITOR FOR THE RESERVOIR

TO OUR NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER ISSUE OF THE CEGA RESERVOIR!

CEGA has a lot of excellent technical luncheon and technical division talks scheduled for the remainder of 2025 and beginning of 2026. Please check the CEGA website to register for these talks and short courses.

In this issue we present the continuation of our regular articles:

• Geology in Motion: The Battle for Oil in WWII

• From the Desk of the AER: 2025 Summer Student Project Summaries

• Geomechanics Today Series: Induced Seismicity in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin

In this issue we present the following technical articles:

• Clinton Tippett: Petroleum History Society and Turner Valley Oilfield Society

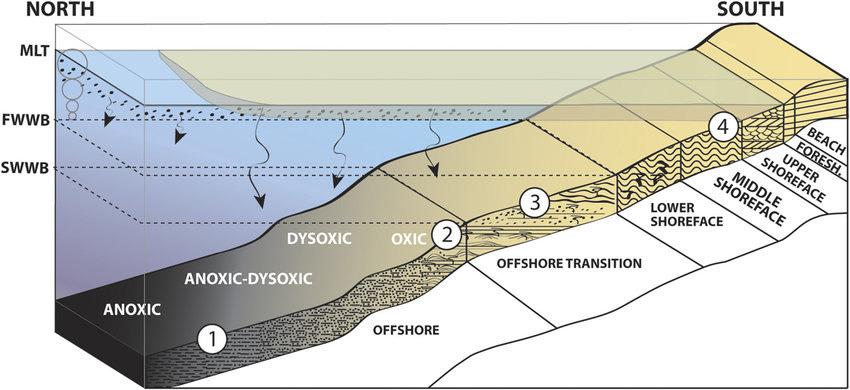

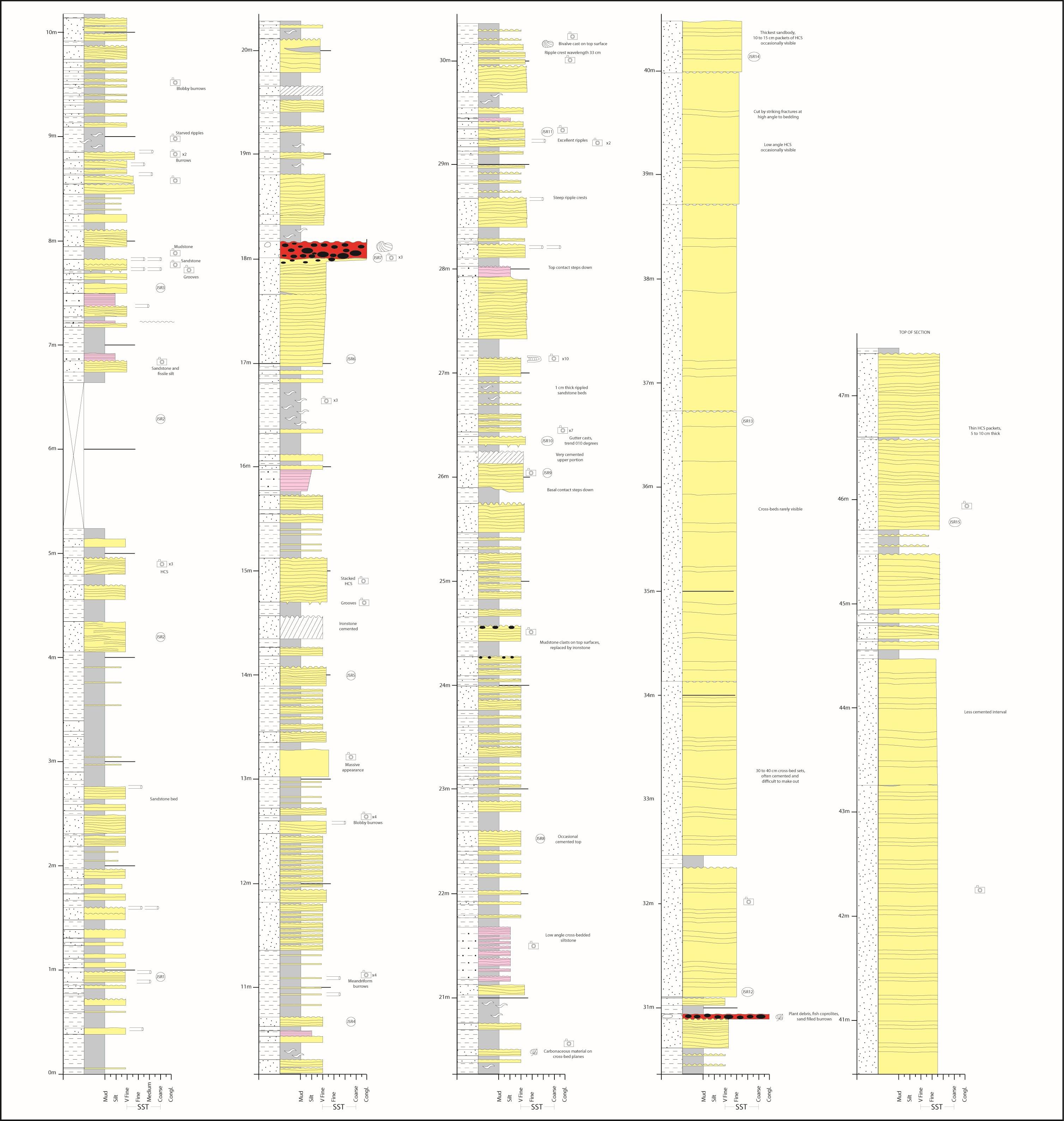

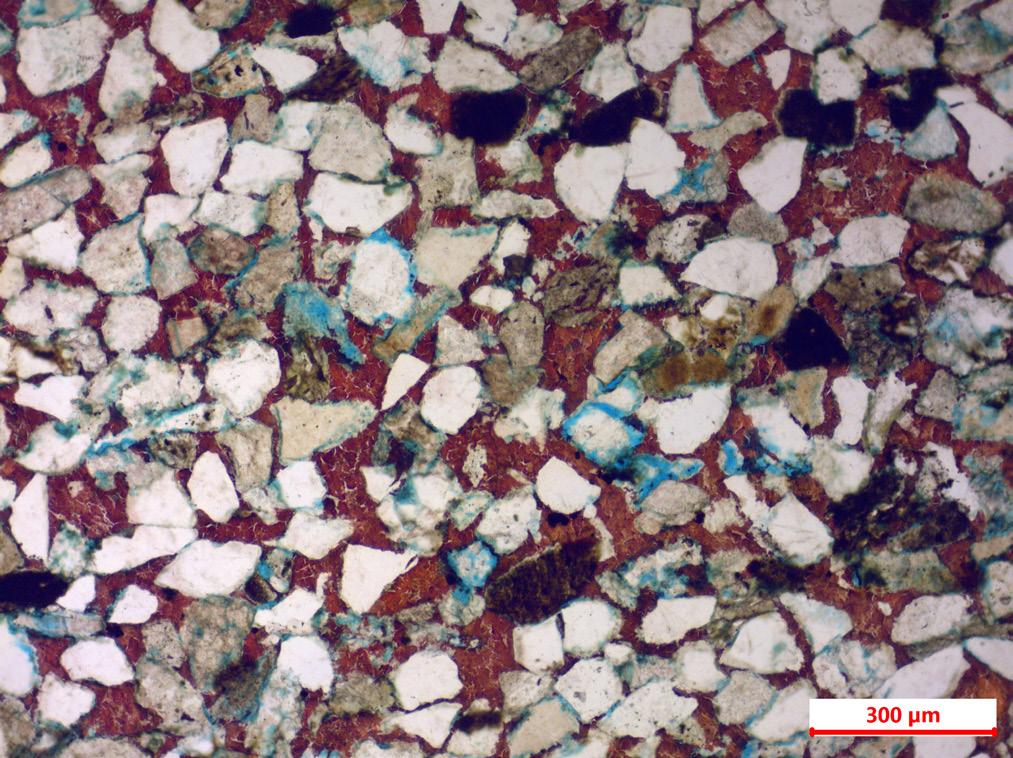

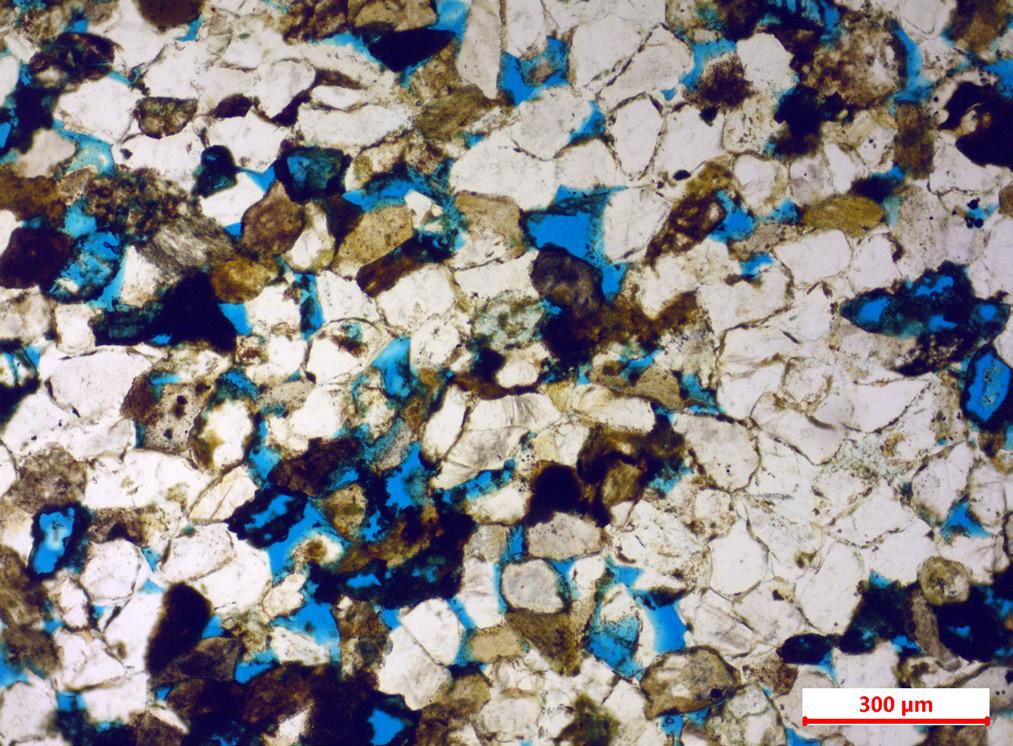

• Jon Noad: The Black Sheep: Book Cliffs of the North

The CEGA Core Conference committee is now accepting abstracts for the 2026 conference which will be held May 7-8, 2026. Please check out the conference website to submit an abstract or to get more information regarding this event.

We look forward to receiving your manuscripts for the upcoming 2026 issues of the CEGA Reservoir.

The RESERVOIR is published 6 times per year by the Canadian Energy Geoscience Association. The purpose of the RESERVOIR is to publicize the Association’s many activities and to promote the geosciences. We look for both technical and non-technical material to publish.

The contents of this publication may not be reproduced either in part or in full without the consent of the publisher.

No official endorsement or sponsorship by the CEGA is implied

for any advertisement, insert, or article that appears in the RESERVOIR unless otherwise noted. All submitted materials are reviewed by the editor. We reserve the right to edit all submissions, including letters to the Editor. Submissions must include your name, address, and membership number (if applicable). The material contained in this publication is intended for informational use only.

While reasonable care has been taken, authors and the CEGA make no guarantees that any of the equations, schematics, or

devices discussed will perform as expected or that they will give the desired results. Some information contained herein may be inaccurate or may vary from standard measurements. The CEGA expressly disclaims any and all liability for the acts, omissions, or conduct of any third-party user of information contained in this publication. Under no circumstances shall the CEGA and its officers, directors, employees, and agents be liable for any injury, loss, damage, or expense arising in any manner whatsoever from the acts, omissions, or conduct of any third-party user.

PRESIDENT

Shelley Leggitt

Kiwetinohk Energy Corp. shelley.leggitt@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

FINANCE DIRECTOR ELECT

David Lipinski

AtkinsRealis directorfinance@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

DIRECTOR

Michael Wamsteeker ExxonMobil publications@cegageos.ca Linkedin

PAST PRESIDENT

Andrew Vogan

ConocoPhillips Canada Ltd. andrew.vogan@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

DIRECTOR

Gary Bugden

Cabra Consulting Ltd membershipdirector@cegageos.ca Linkedin

DIRECTOR

Kevin Webb

Aquitaine Energy Ltd. conferences@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

PRESIDENT ELECT

Christa Williams

Canadian Discovery Ltd. christa.williams@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

DIRECTOR

Scott Leroux

Taggart Oil Corp. education@cegageos.ca Linkedin

DIRECTOR

Dilpreet Khehra Chinook Consulting Services outreach@cegageos.ca LinkedIn OFFICE CONTACTS

MEMBERSHIP INQUIRIES

Tel: 403-264-5610

Email: membership@cegageos.ca

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Rachel Lea

Suncor Energy directorfinance@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

DIRECTOR

Michael Livingstone

GLJ Ltd

technicaldivisions@cegageos.ca LinkedIn

CEGA OFFICE

#415, 500 4th Ave SW

Calgary Alberta, Canada T2P 2V6

Tel: 403-264-5610 | cegageos.ca

ADVERTISING INQUIRIES

Latoya Graham

Tel: 403-513-1230

Email: latoya.graham@cegageos.ca

CONFERENCE INQUIRIES

Kristy Casebeer

Tel: 403-513-1234

Email: kristy.casebeer@cegageos.ca

MANAGING DIRECTOR

Emma MacPherson

Tel: 403-513-1235

Email: emma.macpherson@cegageos.ca

MICHAEL L. WAMSTEEKER; PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR

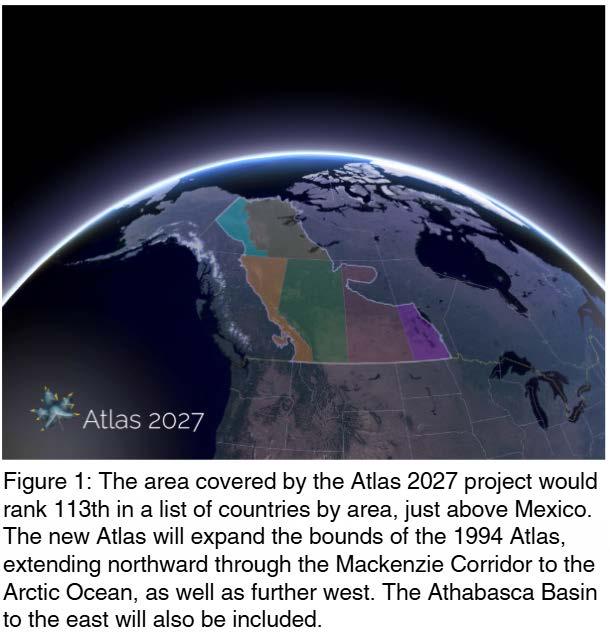

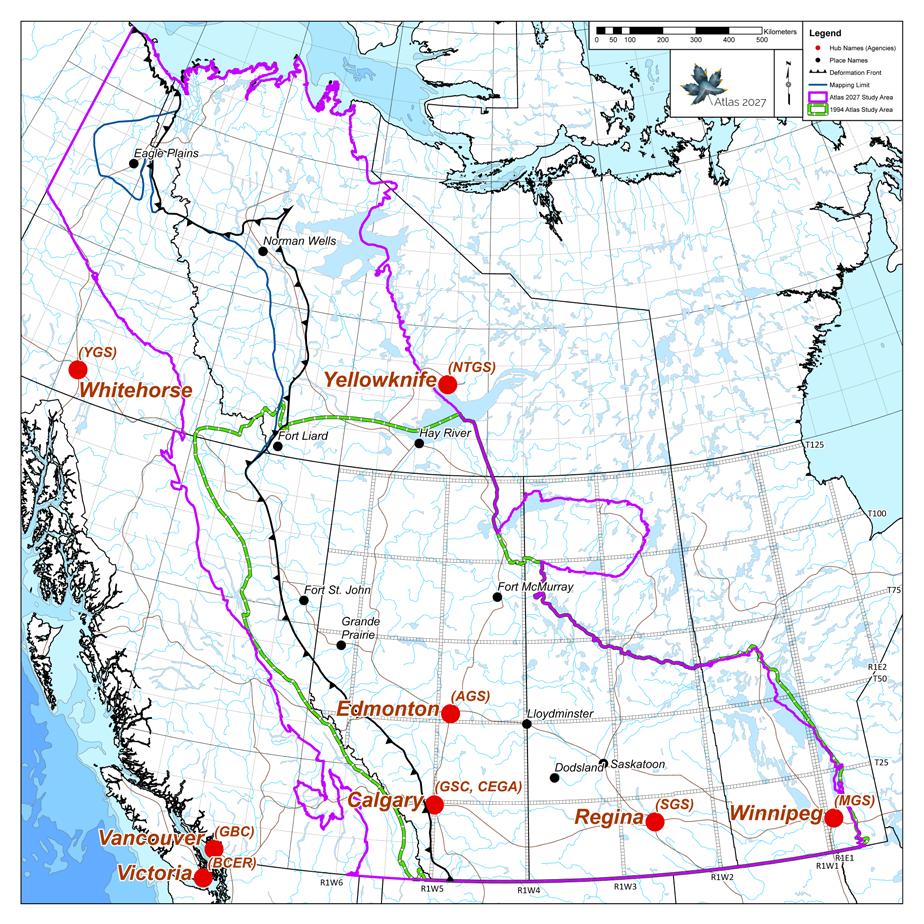

ew publications can match the importance of the Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (ATLAS) to the Canadian energy geoscience community. It embodies several of the noble aspirations of our profession, but perhaps none more important than the commitment to collaborate and share knowledge for the improvement of all members and society. As such, it serves to provide the geoscientific basis for all participants in the energy industry to engage each other—from idea and value creation to development and regulation.

The ATLAS must evolve as new data, scientific concepts, and technology change the scope and nature of energy geoscience. Recent decades have witnessed the advent of widespread unconventional and oilsands development, and initial stages of carbon sequestration, geothermal, lithium, helium, and hydrogen exploration and extraction. An update to the venerable 1994 ATLAS is needed to maintain its relevance and functionality.

Volunteers from industry and federal and provincial regulators belonging to the ATLAS 2027 Organization have been stewarding this update for the past five years. Containing 50+ chapters created by over 200 authors, the new ATLAS will also change to reflect digital realities of information consumption and integration, with print (on demand), PDF, and webmap versions. Initial publication will coincide and form a central and poignant part of the upcoming CEGA 100th Anniversary celebrations in 2027.

As we enter the final months of this year, ATLAS 2027 is reaching a critical juncture. Initial chapter drafts are due at year end, with

integration, editing, and document production commencing and forming the focus of 2026 activities. This will be a considerable task, requiring the focus and energy of a committed group of people. As such, the ATLAS 2027 Organization is issuing a formal Request for Proposals for interested organizations or group of persons to compile, review, and execute production of Atlas 2027 materials for publication. A brief description, as well as contact information for further questions and submission is included in this edition of the Reservoir. Interested parties are also invited to contact Ben McKenzie, Chair of the Technical Support Committee, directly (atlas2027.gis@gmail.com).

Production and publication will require financial support. Assembling the required funding in the next couple months to provide a solid basis for production is imperative. As such, volunteers from ATLAS will be entering a period of intensive canvasing for donations from individuals and organizations within the Canadian energy industry. If you, or your organization, is interested in donating, please contact Jackie Urban (urban@agatlabs.com) to discuss and review the sponsorship proposal.

The ATLAS 2027 Organization would like to thank everyone for their efforts and contributions over the past five years. With continued support, we look forward to a productive 2026 and eventual completion and celebrations in 2027!

Yours truly,

Mike Wamsteeker

On behalf of the 2027 ATLAS Organization and CEGA

Atlas 2027 represents the large undertaking to renew the classic 1994 Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, published by the Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists and the Alberta Research Council (predecessors to the Canadian Energy Geoscience Association (CEGA) and the Alberta Geological Survey (AGS)). Similar to the previous Atlas (Atlas 1994), this version will take over seven years to, require support from multiple agencies, and thousands of hours of commitment from hundreds of authors and volunteers. Combined with the data of hundreds of thousands of wells, outcrop observations and remote sensing, the final result will be one of the most extensive geological treatises ever published.

Over 200 volunteer geoscientists have been working in groups on specific chapters to update the Atlas. They are tasked with providing publicationready material for their chapter by the end of 2025.

The task outlined by these RFPs is to communicate with the various authors, obtain and/or create, compile the submitted materials, review and prepare them to a publication-ready state by February 1, 2027

ATLAS 2027 invites organizations, or groups of individuals, to respond to two separate Requests for Proposals to create a project team to make the 2027 ATLAS reach completion.

1. RFP 2025-01: Atlas 2027 Publication Preparation. Services to be provided will include assisting authors with graphics and GIS mapping as required, coordinating submitted material from Atlas 2027 authors, ensuring material meets Atlas 2027 guidelines, and preparing documents and export files from material for both PDF and WebMap publication.

2. RFP 2025-02: Atlas 2027 Regional Cross-Sections. Contracted services will include obtaining logs and assembling them into crosssections similar to those in the 1994 Atlas, coordinating tops and correlations with Atlas 2027 authors, digitizing logs as required, and providing digital files ready for publication

Detailed RFP documents can be obtained by contacting Ben McKenzie, Chair of the Technical Support committee at atlas2027.gis@gmail.com.

Bidders are encouraged, but not required to submit proposals for both requests. However, successful bidders not participating in RFP 2025-02 will be required to work with and integrate their product with winning bidder of the RFP 2025-01.

Submission Deadline for both proposals is December 1, 2025, with earliest contract start date January 1st, 2026.

The Alberta Energy Regulator and the Alberta Geological Survey, a branch within the regulator, offer summer student positions each year, helping to train the next generation of geoscientists. The projects help to meet research objectives. We have short descriptions from four of the students that joined us this past summer.

Haedon

Evanski, BSc (Honours) student, Queen’s University

This summer, I participated in a five-week field program with the Emerging Resources team at the Alberta Geological Survey focused on investigating mineral systems of the Canadian Shield in northeastern Alberta. Our fieldwork was primarily supported by float planes operating out of Fort McMurray.

During the first half of the program, we camped on the north shore of Lake Athabasca,

using inflatable Zodiac boats to access various traverse locations. For the latter half, we stayed at two fishing lodges farther north on the Canadian Shield, providing better access to key areas of interest.

I assisted on geological traverses, helping to interpret the area’s complex geology and evaluate its potential to host a wide range of critical minerals. While the Alberta Geological

Survey mapped this region in detail during the 1960s and 70s, high-resolution mapping has not been conducted since. Our objective was to revisit specific areas of the Canadian Shield using modern methods to better assess their mineral potential. Particular attention was given to resources critical to today’s economy, such as lithium, rareearth elements, uranium, and both base and precious metals.

1

Examining an outcrop of Burntwood Complex on the north shore of Lake Athabasca

Derek Dubrule, BSc in a Double Major Computer and Earth Science Program, University of Alberta

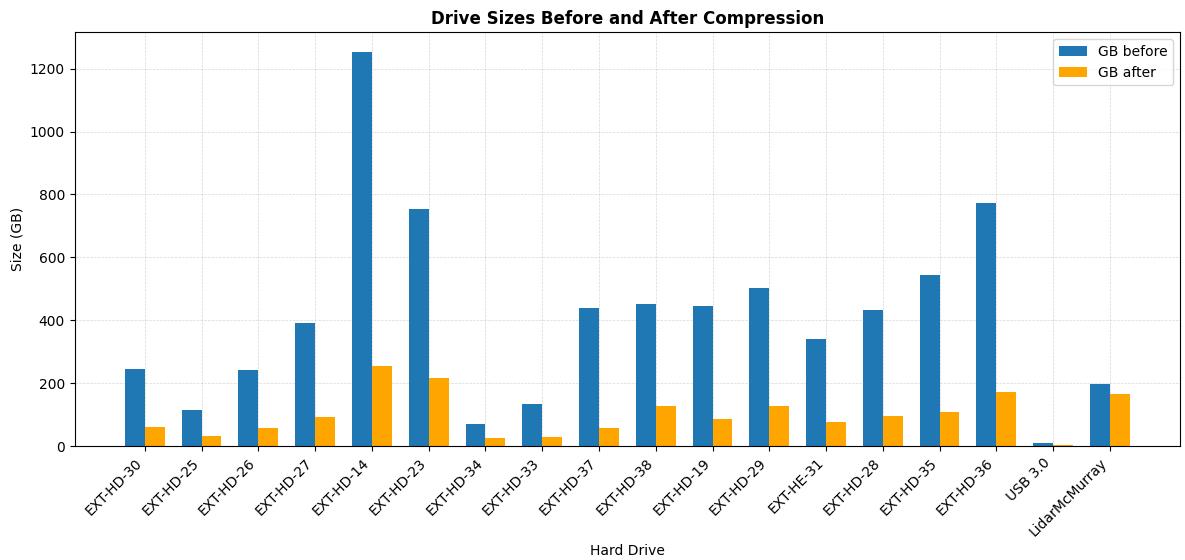

This summer at the AER, I worked on the Data Management Solutions 2 project. Within this project, I was working on the Legacy Digital Data task. I built an automated data pipeline that extracts decades of old LiDAR data from external hard drives and uploads a compressed version to Azure Blob storage. Written in Python, the script iterates through each drive and converts .las point-clouds to compressed .laz files, transforms ASCII grids into GeoTIFFs, and skips non-essential hillshade and bare-earth files. This resulted in 7.3 TB of raw data being reduced to 1.8 TB in the cloud. This was a 75% space reduction that greatly cuts storage costs.

More importantly, this data will eventually be moved to a spatial database, such as PostGIS, enabling AGS employees to access these high-value datasets more efficiently and improve the workflow of future projects. The accompanying figure shows a comparison of the size of each hard drive before and after the project.

As the Legacy Digital Data project wrapped up, I was able to join another exciting challenge in the Data Management Solutions 2 project, called Metadata System Discovery. Working alongside a great team of a data scientist and geologist, I helped with the prototyping of a dashboard that will allow staff to search a

database using natural language processing (NLP), visualize the data on a map, and download the records as needed; a future goal is to give users the option to input data into the system as well. In this phase, I am currently evaluating UI frameworks and testing different NLP approaches to deliver the best user experience. Together, these projects are modernizing how AGS retrieves and stores its valuable data. This will result in more efficient and streamlined access to this data, improving work productivity and project outcomes.

Shiv Khetarpal, BSc

The Southern Alberta Groundwater Evaluation (SAGE) project’s objective is to map and describe groundwater resources across Southern Alberta. Aquifer recharge (i.e., where water on the landscape infiltrates to replenish groundwater) is regionally mainly driven by depression-focused recharge. In this mechanism, water collects in small depressions on the landscape and percolates into the ground during seasonal thaw.

This summer, I have been developing a workflow to spatially distribute estimated recharge values. This involved working with LiDAR digital elevation models and modifying a terrain analysis workflow in GIS software to include a morphology-based surficial classification, which describes the landscape topography more accurately than surficial geology classifications. From the terrain analysis, I extracted depression characteristics from a sub-area and used existing recharge data to calculate and distribute new annual recharge estimates to the larger study area based on morphology. Understanding where and how much aquifer recharge occurs is important as it is essential for managing groundwater resources.

I also had the opportunity to go on a field trip to northeastern region of the SAGE project area, north of Brooks all the way to the Saskatchewan border. We were section logging and collecting samples to supplement a subsurface model that is being made. It was a lot of fun, and I learned a lot about the geomorphology of southern Alberta.

Vlad Stepanov, Master of Data Science and Analytics (MDSA) Program, University of Calgary

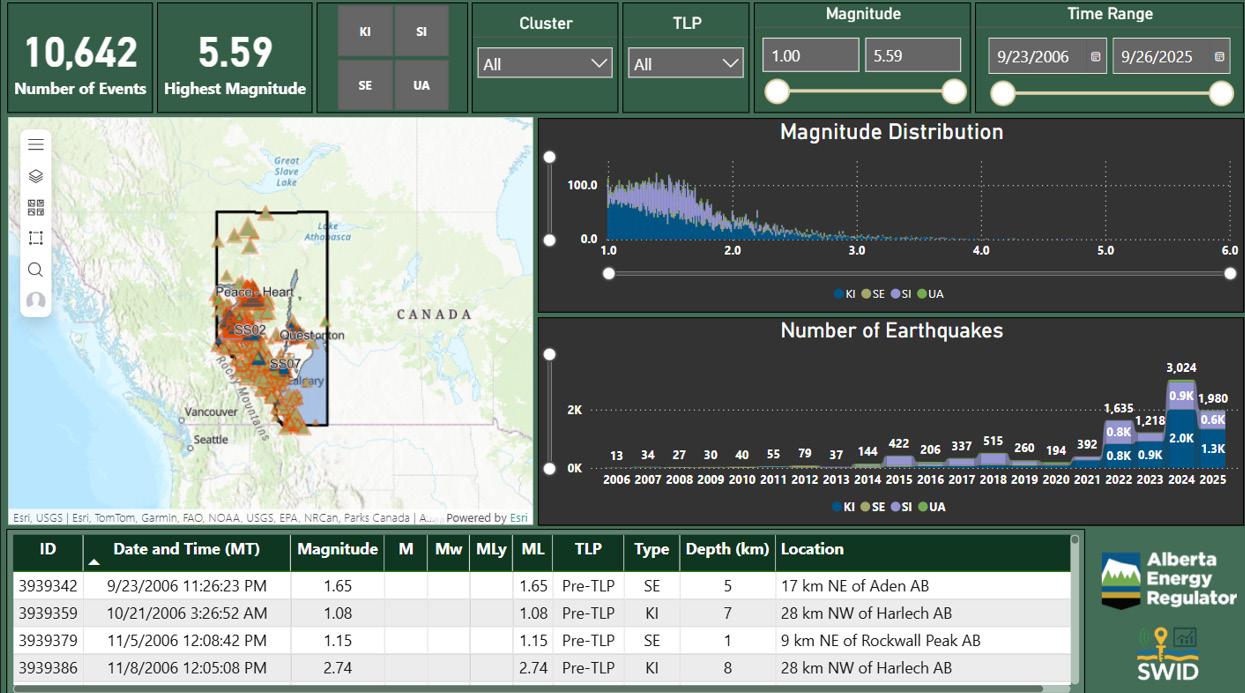

Within the last several years, Alberta has seen a notable rise in seismic events with a major contribution coming from subsurface energy operations. This highlights the need for quick access to reliable information to support analysis and regulatory decision-making. To address this, the Seismic Well Integrated Dashboard (SWID) was developed around a “3D” (Data, Dashboards and Decision) framework with three key objectives:

integrate seismic and disposal well activity data, enable spatial analysis and versatile filtering, and facilitate decision-making. Direct connection to AER databases, set up in Power BI, ensured the latest event history and most relevant data, while built-in ArcGIS map visuals combined with Haversine geospatial methods enabled intuitive and effective spatial analysis. The final product is a set of four interactive reports: Data Quality page

showing data sources and percent missing information, Seismic page with history of seismic activity in Alberta, Wells page with details on disposal wells and Combined page that integrates well and seismic data for detailed geospatial analysis – providing easy and reliable access to the data when it is needed.

4 Seismic-well integrated dashboard developed for internal use at the AER

November 12

Wednesday, 11:45 AM - 1:00 PM

Technical Luncheon

Addressing Challenges in RTA using New Core Analysis Method - A Luncheon Hosted in Collaboration with SPE Calgary Chapter

Speaker: Dr. Christopher Clarkson

Location: De CalgvonaryianPeBallrtroleumoomClub, 319 5 Avenue SW,

November 19

Wednesday, 12:00 – 1:00 PM

International Technical Division

A Decade of Discovery: CNOOC’s Journey in the Guyana Stabroek Block

Speaker: Tim Truax

Location: New CEGA Classroom, 500 4 Ave SW, Calgary, AB

November 20

Thursday, 12:00 – 1:00 PM

Hybrid GeoWomen Talk

Solo Across Indonesia, Land of Volcanoes, Ancient Temples, Giant Lizards, and Wild Beauty

Speaker: Solange Angulo, PhD., P.Geo.

Location: New CEGA Classroom, 500 4 Ave SW, Calgary, AB

November 21

Friday, 7:30 - 9:00 PM Hybrid Palaeontology Technical Division Talk

Fifty+ Years of Research at the Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, SD

Speaker: Chris Jass, Ph.D., Curator at Royal Alberta Museum, Edmonton, Alberta

Location: Mount Royal University Room B108, 4825 Mt Royal Gate SW, Calgary, AB

November 25

Tuesday, 11:45 AM - 1:00 PM In-Person

Technical Luncheon

Planning Big Versus Building Big: The Reality of Canada’s Energy Workforce Woes

Speaker: Bill Whitelaw, Rextag

Location: Calgary Petroleum Club, 319 5 Avenue SW, Devonian Ballroom

December 2

Tuesday, 4:00 - 6:00 PM In-Person

International Technical Division

Holiday Social

Location: LOCAL Public Eatery Barclay 201 Barclay Parade SW, Calgary, AB

December 3

Wednesday, 12:00 – 1:00 PM Hybrid BASS Technical Division

Capturing your vision of the stratigraphy in a 3D geological model

Speaker: Thomas Jerome

Location: New CEGA Classroom, 500 4 Ave SW, Calgary, AB

December 10

Wednesday, 12:00 – 1:00 PM Online Only

Geothermal Technical Division

EGS Geothermal - A Past, Present, and Future Perspective

Speakers: Evan Renaud and Saurabh Agarwal

January 27

Tuesday, 11:30 AM - 1:00 PM In-Person

Technical Luncheon

Facies Sedimentology, Heterogeneity and Reservoir Quality of a New Montney Turbidite Play, Simonette, Alberta

Location: Calgary Petroleum Club, 319 5 Avenue SW, Devonian Ballroom

Speaker: Thomas F. Moslow, Ph.D., P.Geol., Moslow Geoscience Consulting Ltd.

I would like to take this opportunity to introduce CEGA members to two local organizations that are closely related to the history of the Canadian petroleum industry.

The Petroleum History Society (PHS) was founded in 1985 with a mandate to collect and conserve the historical recollections of industry participants through a major oral history project spearheaded initially by industry author, geologist Aubrey Kerr. In addition, the PHS undertook an initiative to promote establishing a petroleum-related learning centre in Turner Valley, where the industry’s first major gas-processing facility had just been shut down. Although the interpretive facility was not constructed, the PHS has continued with its program of luncheon talks, field trips, and walking tours over the intervening decades. The PHS holds these interesting luncheon talks at the Petroleum Club on 5 Avenue, quite close to CEGA’s offices. They are scheduled at noon 5-6 times per year. The cornerstone of its activities is its website (petroleumhistory.ca) and Archives newsletter, issued six to eight times per year; both the website and newsletter contain a wealth of information. The PHS has carried on the tradition of oral history through its Oil Sands Oral History Project, which involved interviewing many of the past and present key players in that sector. Although geologists have played a leading role with the PHS, people from other disciplines have also contributed, including geophysicists, engineers, landmen, petrophysicists and historians.

The PHS and CPSG/CEGA have a long history of overlap via individuals who have been active in both organizations. This is expected given the strong geological content in many industry events with leading figures having been geologists. Aubrey Kerr and Jack Porter, both PHS directors, authored a pair of popular series of historical articles in the Reservoir. Jack was the longtime chair of the CSPG’s History and Archives Committee. Jack and I were involved with David Finch in the production of his 2002 book “Field

Notes”, which was produced on the 75th anniversary of the CSPG. I was chair of the Stanley Slipper Gold Medal Committee, which has a strong historical overprint. Other geologists who have played roles in both organizations are Ian Kirkland, Bill McLellan, and Tako Koning.

Our sister group, the Turner Valley Oilfield Society (TVOS), was chartered in 1978 with the target of preserving the history of the Turner Valley region. Over the years, its focus has centred on the history of the local petroleum industry and the aforementioned natural-gas processing plant. A similar plan to support an interpretive venture did not bear fruit, but the TVOS has continued to be active in the community. This has been partly in cooperation with Alberta Culture, which now owns the gas plant site that was designated as a Provincial Historic Resource in 1989 and a National Historic Site in 1995. Their program of plant tours is a popular activity for individuals and groups. The TVOS is a federally-registered charity, and its website, containing a tremendous amount of information about the history of the Turner Valley Oilfield, is turnervalleyoilfieldsociety.ca.

The PHS and the TVOS have recently established a working relationship in which membership in the TVOS is included in PHS membership. The cost of that membership is $30 per year with one becoming a member of both societies.

If you are interested in joining us, as either a member or a volunteer, please visit our website at petroleumhistory.ca for details and instructions. Alternatively, I would be pleased to hear from you at clintontippett88@gmail.com.

ALIREZA BABAIE MAHANI, PH.D. P.GEO., BGC ENGINEERING INC.

The Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) is one of Canada’s most important geological provinces for hydrocarbon production, hosting extensive unconventional resources in northeast British Columbia (NE BC) and western Alberta. While historically characterized by low levels of natural seismicity, this region has experienced a notable increase in the rate of seismicity attributed to the expansion of unconventional oil and gas development, particularly from injection of large volumes of fluid for the purpose of hydraulic fracturing of low-permeability reservoir rocks and the subsequent disposal of wastewater byproduct.

The increase in the rate of seismicity and the occurrences of several significant earthquakes (magnitudes ≥ 4) have prompted regulatory bodies in both Alberta and BC to implement orders, guidelines, traffic light protocols, and mandatory monitoring zones with the aim of reducing the likelihood of potentially destructive earthquakes. However, challenges remain in several areas, such as developing robust predictive tools and assessing the long-term seismic hazard from induced earthquakes.

The goal of this paper, which draws from the author’s experience in induced-seismicity research and consulting over the last decade, is to

1) document the current state of knowledge regarding induced seismicity in the WCSB;

2)highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach towards understanding induced-seismicity processes involving geology, geomechanics, and seismology;

3)discuss the existing regulatory framework for monitoring and mitigation of induced seismicity hazard; and

4)discuss induced seismicity hazard assessment.

The WCSB is a vast sedimentary basin extending from the Canadian Rocky Mountains eastward across NE BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and into Manitoba. The basin is composed of a thick sequence of sedimentary rocks (thickening from east to west), with a maximum thickness of ~6 km, that overlies the Precambrian crystalline basement. The WCSB hosts major hydrocarbon plays, such as the Montney Formation in NE BC and northwest Alberta and the Duvernay Formation in west-central Alberta. These formations are prolific hydrocarbon producers and have been the focus of intensive hydraulic fracturing operations and wastewater disposal. The regional stress field within these resources is characterized

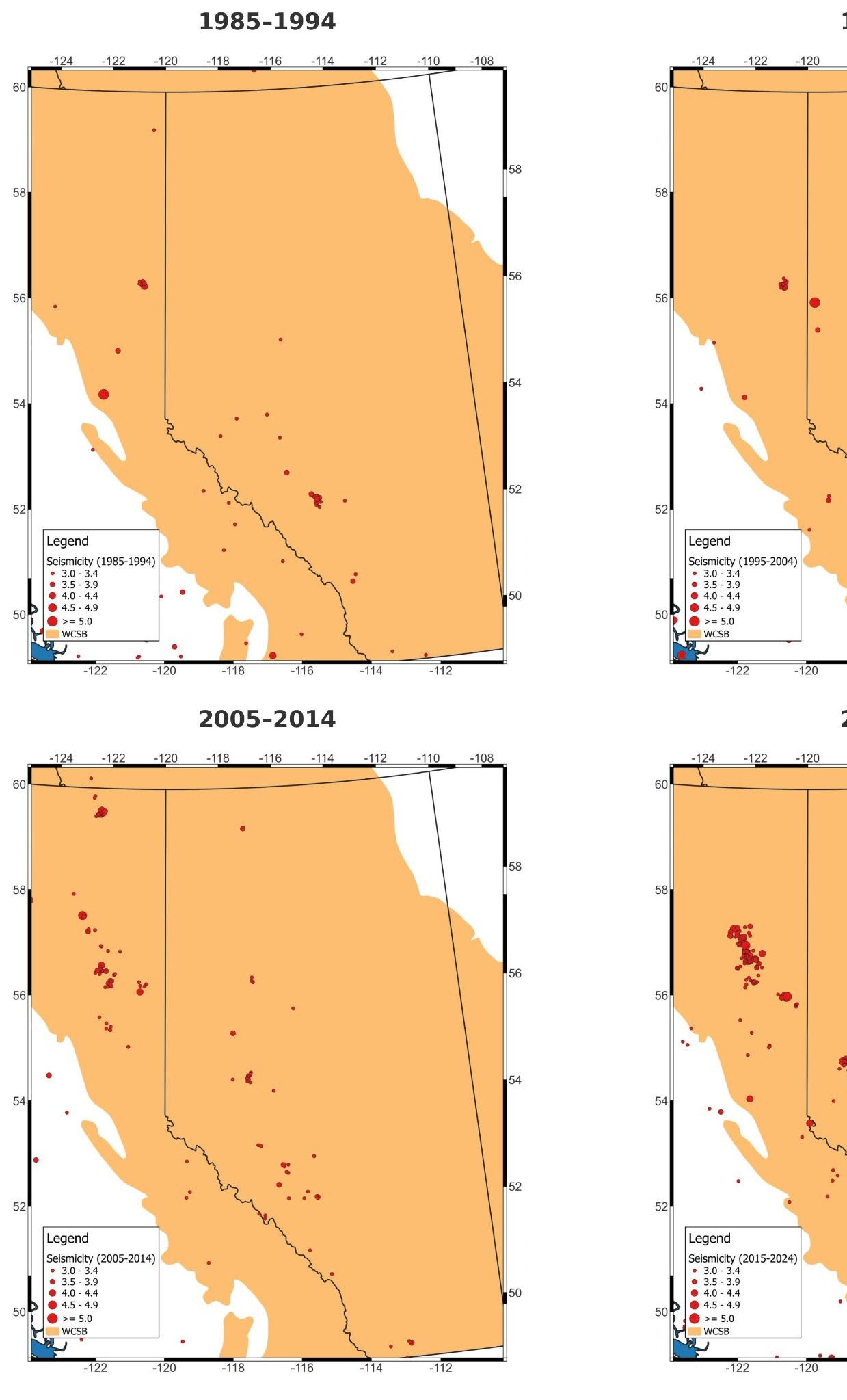

by a dominant NE–SW maximum horizontal stress, consistent with a compressional regime. Within this compressional regime, earthquake focal mechanisms confirm thrust faulting for events that are close to the Rocky Mountains (Babaie Mahani et al., 2017a). Away from the deformation front, however, complex geological conditions are manifested by other solutions, such as strike-slip or normal mechanisms in areas like the Fort St. John Graben (Babaie Mahani et al., 2020). Extensive research has correlated the occurrence of induced seismicity to fluid injection (mainly to hydraulic fracturing) both temporally and spatially within the WCSB (e.g., Atkinson et al., 2016). Figure 1

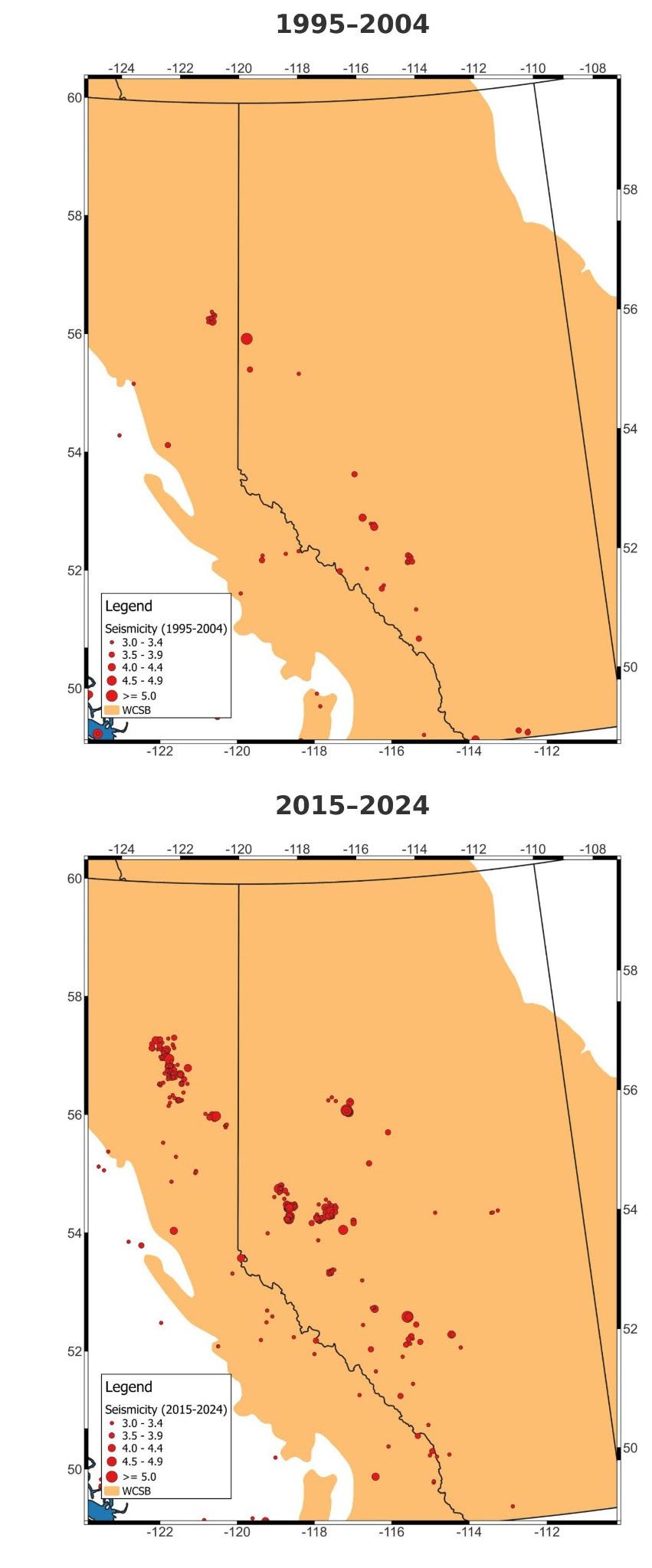

shows maps of seismicity (from the National Earthquake Database of Natural Resources Canada [NRCan]) with magnitudes ≥ 3 in NE BC and western Alberta over the past four decades. Only earthquakes with magnitudes ≥ 3 are shown because 1) earthquakes smaller than 3 are usually not important from the point of view of hazard potential and 2) this value should be close to the magnitude of completeness1 within the WCSB over four decades ago and certainly well above the magnitude of completeness in recent years in many areas due to increased monitoring. In other words, it is safe to assume that all earthquakes that have occurred in the past four decades with magnitudes ≥ 3 were detected and catalogued in the national database. Seismicity in Figure 1 is shown over four time periods of 1985–1994, 1995–2004, 2005–2014, and 2015–2024. The increase in the level of seismicity in NE BC and western Alberta is evident from the seismicity clusters. To put this increase in perspective, Figure 2 shows the frequency-magnitude distribution of earthquakes in NE BC (latitudes 55° to 60° N and longitudes 120° to 125° W) in each period by plotting the cumulative annual number of earthquakes versus magnitude. While the difference between the annual number of earthquakes (magnitudes ≥ 3) is subtle between the time periods of 1985–1994 (annual rate of 1.6) and 1995–2004 (annual rate of 1.4), this difference becomes more significant for the time periods of 2005–2014 (annual rate of 7.4) and 2015–2024 (annual rate of 13.8). Another important insight from Figure 2 is that the increase can be seen not only for overall seismicity but for larger earthquakes as well (magnitudes ≥ 4). While there were 0.4 events per year with magnitudes ≥ 4 during 2005–2014, there were 1.5 such events in 2015–2024—a threefold increase.

In Canada, NRCan monitors seismic activity across the country through a dedicated national network. Considering that the national network’s focus is to monitor seismicity across different regions, both inland and offshore, several regional networks have also been established to monitor induced seismicity in BC and Alberta. Moreover, oil and gas companies have also established their own local seismograph networks, which have proven effective in providing valuable data, especially at close distances to injection operations (Babaie Mahani, 2025). In 2012,

1. Maps of seismicity (magnitudes ≥ 3) in northeast British Columbia and western Alberta since 1985. WCSB: Western Canada Sedimentary Basin.

1 Magnitude of completeness is the minimum magnitude above which all earthquakes within a region are reliably recorded.

Figure 2. Cumulative annual number of events with magnitudes ≥ 3 in northeast British Columbia during 1985–1994, 1995–2004, 2005–2014, and 2015–2024.

the BC Seismic Research Consortium was established with the main objective of providing infrastructure for seismic monitoring across the unconventional resource regions of NE BC (i.e., Liard Basin, Horn River Basin, Cordova Embayment, Montney play) (Salas et al., 2013; Salas and Walker, 2014; Babaie Mahani et al., 2016). The consortium is a partnership between the BC Energy Regulator (BCER), Geoscience BC, NRCan, and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP). Over the years, many seismographic stations have been installed, mostly in the Montney play, which have recorded thousands of induced earthquakes, resulting in the development of comprehensive earthquake databases that include seismicity catalogues and groundmotion datasets (Visser et al., 2017, 2020, 2021; Goerzen et al., 2024). Similarly, the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) has established the RAVEN seismographic network in Alberta and has continuously expanded this network over the years as new clusters of seismicity have emerged across the province (Schultz and Stern, 2015).

The regulatory framework in BC is established by the BCER (through a close relationship with industry) through special project orders for two areas in the southern and northern Montney play. The Kiskatinaw Seismic Monitoring and Mitigation Area (KSMMA) Special Project Order, which first came into effect in May 2018, was last updated in February 2025. It applies to hydraulic fracturing operations in the southern Montney play and includes the following specifications:

• Companies are required to perform a baseline seismicity study in the area prior to starting their hydraulic fracturing operations.

• Companies are required to have a monitoring, mitigation, and response (MMR) plan.

• Seismic monitoring is required within 5 km of the injection well. Reporting is required for any earthquake with local magnitude (ML) ≥ 1.5, and the MMR plan should be implemented for events with ML between 2.0 to 2.99. Suspension of operations happen following an earthquake with ML ≥ 3.0 (red light earthquake). Following resuming operations, if another event with ML ≥ 2.7 occurs, operations should be suspended again.

• Companies are required to submit their passive seismic data in case of felt events or recorded ground motions in excess of 0.008 g.

The North Montney Seismic Mitigation and Monitoring Area (NMSMMA) Special Project Order was issued in February 2025 and applies to the northern Montney play with the following specifications:

• Companies are required to perform a baseline seismicity study in the area prior to starting their hydraulic fracturing operations.

• Companies are required to have an MMR plan.

• Seismic monitoring is required within 5 km of the injection well. Reporting is required for any earthquake with local magnitude (ML) ≥ 2.5 and the MMR plan should be implemented for the events with ML between 3.0 to 3.99. Suspension of operations happen following an earthquake with ML ≥ 4.0 (red light earthquake). Following resuming operations, if another event with ML ≥ 3.7 occurs, operations should be suspended again.

• Companies are required to submit their passive seismic data in case of felt events or recorded ground motions in excess of 0.008 g.

The BCER has also published several documents to help industry follow these orders, such as technical guides on issues related to seismic monitoring, earthquake magnitude, and ground-motion estimation and reporting (Babaie Mahani and Kao, 2020; Babaie Mahani, 2025).

Similarly, the AER establishes the regulatory framework for hydraulic

fracturing operations in Alberta through subsurface orders for the Duvernay play in central Alberta (Subsurface Order No. 2A effective as of November 6, 2024), Brazeau region (Subsurface Order No. 6 effective as of May 27, 2019), and Red Deer (Subsurface Order No. 7 effective as of December 9, 2019). Generally, these subsurface orders require the companies operating within the relevant areas to perform a baseline seismicity study prior to starting hydraulic fracturing operations and have an MMR plan in place. The following are specifications pertinent to each subsurface order:

• Subsurface Order No. 2A: Seismic monitoring is required within 5 km of the injection well with capability of detecting earthquakes as small as ML = 2.0. The MMR plan should be implemented in case of earthquakes with ML ≥ 2.0 and should be reported to AER. Operations should be suspended in case of earthquakes with ML ≥ 4.0 and passive seismic data should be submitted to AER

• Subsurface Order No. 6: Seismic monitoring is required within 5 km of the injection well with capability of detecting earthquakes as small as ML = 1.0. The MMR plan should be implemented in case of earthquakes with ML ≥ 1.0 and should be reported to AER. Operations should be suspended in case of earthquakes with ML ≥ 2.5 and passive seismic data should be submitted to AER.

• Subsurface Order No. 7: Seismic monitoring is required within 5 km of the injection well with capability of detecting earthquakes as small as ML = 1.0. The MMR plan should be implemented in case of earthquakes with ML ≥ 1.0 and should be reported to AER. Operations should be suspended in case of earthquakes with ML ≥ 3.0 and passive seismic data should be submitted to AER.

The AER has also updated Directive 065 with sections specific to seismic monitoring and seismic hazard assessment of fluid disposal-induced seismicity (including CO2 storage) (AER, 2024). The new update (effective as of November 12, 2024) requires companies applying for new fluid disposal wells or amending the operating conditions of existing wells to perform seismic-hazard assessment by, for example, following the methodology for probabilistic seismic hazard assessment. If the hazard assessment shows considerable level of seismic hazard, companies are required to submit, with their application, the results of both seismic hazard and seismic risk assessments and to propose an MMR plan. This situation will likely hold true for areas with historical seismicity (Figure 1)(the section “Induced Seismicity Hazard Assessment” below provides more details on a case study that can be applied to any area within the WCSB in order to follow the regulatory guideline of Directive 065). If the seismic hazard assessment does not show a significant level of seismic hazard, companies are required to only submit with their application the results of the seismic hazard assessment. For existing wells that become seismogenic (e.g., encountering seismicity as described in BCER and AER orders), companies are required to perform and submit the results of a seismic risk assessment and propose an MMR plan. Note that the main difference between seismic hazard and seismic risk assessments is the inclusion of exposure and vulnerability of the built environment and everything that is subject to seismic hazard (including people and structures) in seismic risk assessment.

Although most induced earthquakes caused by fluid injection are very small, many too small to even to be felt at the surface (magnitudes < 1), larger events can be felt (starting at magnitudes > 2) and even cause significant ground motions (usually magnitudes > 3) at close distances due to their shallow depths. With the expansion of the monitoring

networks across the WCSB, more near-field ground motions have been recorded, which are essential in understanding ground-motion hazard and its variability. For example, the August 17, 2015, earthquake with moment magnitude (Mw) of 4.6 in the northern Montney play of BC was recorded by a local seismograph network, owned by Progress Energy Canada Ltd., at a distance range of 5 to 100 km. Although waveforms from this event were clipped at epicentral distances as far as ~40 km (an indicator of large ground motion at close distances), reconstruction of the clipped waveforms provided estimates of peak ground acceleration (PGA) as high as ~173 cm/sec2 (~17% of g) at epicentral distance of ~5 km (Babaie Mahani et al., 2017b). In another study, Babaie Mahani et al. (2021) provided a comprehensive dataset of macroseismic intensity distribution from induced earthquakes that occurred in NE BC between 2016 and 2020. For each felt report gathered by the BCER, an intensity value was assigned according to the Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) scale based on the descriptions given in the report. Using the compiled dataset, Babaie Mahani et al. (2021) constructed the isoseismal map of the November 30, 2018, Mw 4.6 hydraulic-fracturing-induced earthquake that occurred in the southern Montney play of NE BC and reported a radius of ~10 km for the approximate extent of the maximum intensities (MMI of 4–5). Note that an MMI of 5 corresponds to moderate shaking, described by the USGS as felt by nearly everyone (many awakened), some dishes and windows broken, unstable objects overturned, and pendulum clocks may stop. Moreover, through quantitative analysis of the distance decay of intensity from events with Mw between 4.5 and 4.7, Babaie Mahani et al. (2021) showed that at close distances (10–15 km), shallow (depth ≤ 5 km) induced events generate higher intensities than deeper (depth ≥ 10 km) natural earthquakes. At greater distances, however, intensities from shallow earthquakes drop significantly and become lower than deeper events. Observation of high intensities at close distances from shallow induced earthquakes is an important factor that should not be overlooked in future hydrocarbon resource developments. As a mitigation strategy, buffer zones can be established around infrastructure where fluid injection operations can not take place. Although large ground-motion amplitudes are expected at close distances from induced earthquakes, an important factor to consider is the short duration of these ground motions (e.g., ~1 sec). The implication is that while large ground accelerations (above structural damage threshold) can be expected, the resulting ground velocity is small and bellow the structural damage threshold since velocity is the integral of acceleration.

Extensive research has been done on induced seismicity within the WCSB by academia, government agencies, and the private sector, particularly in the past 5–10 years, corresponding to the increase in the occurrence of induced seismicity as discussed earlier. These studies address a full range of topics around induced seismicity, including its geological, geomechanical, and operational causes and risk factors, monitoring technologies, mitigation strategies, and hazard assessment. In addition to a large body of peer-reviewed publications, the results of much of this research are available to the public via the websites of the hosts and/or funding agencies, such as the BCER, the BC Oil and Gas Research and Innovation Society, Geoscience BC, and the AER (including the Alberta Geological Survey).

In some cases, researchers have utilized artificial intelligence algorithms for this purpose, especially for event detection on seismic records and for getting insights into the complex processes involving geological, operational, and seismological factors. For example, Esfahani et al. (2024) analyzed the most influential controlling factors of hydraulic

fracturing-induced earthquakes within the Montey play of NE BC using machine learning. They found that, in general, the number of hydraulic fracturing stages is the most important factor controlling induced seismicity, followed by the volume of injected fluid. However, they observed that the correlation between these operational factors and the occurrence of induced seismicity does not follow a linear trend. For example, the influence of the number of hydraulic fracturing stages on the number of induced earthquakes becomes significant when the number of hydraulic fracturing stages reaches ~2200. For the cumulative volume of injected fluid, they reported a threshold of ~500,000 m3 Moreover, they reported that the occurrence of induced earthquakes is mostly encouraged when injections occur within ~300 m below the top of Montney Formation (associated with the maximum thickness of this formation in NE BC) and at ~1700 m above the top of basement.

These observations do not imply that smaller scales of hydraulic fracturing operations can not induce earthquakes; rather, they point to the complex nature of induced-seismicity process where other factors, such as in situ stress condition and distance to geological features (faults or pre-Cambrian basement), are also important. These findings are also in line with earlier statistical work on induced seismicity within the WCSB that suggested only a very small fraction of injection operations are correlated with significant level of induced seismicity (magnitudes ≥ 3)(Atkinson et al., 2016).

In recent years, several similar machine-learning studies performed in various areas of the WCSB have resulted in a wide range of (sometimes conflicting) results, making it clear that we still have much to learn regarding the causes and mitigation strategies of induced seismicity.

Monitoring present-day fluid injection and collecting seismicity data (e.g., earthquake locations and recorded ground motions) are crucial in understanding the induced-seismicity process, compliance with regulatory framework, and implementation of mitigation strategies. However, evaluating seismic hazard has been standardized for more than 50 years, since the publication of Cornell (1968), which provided the mathematical framework for probabilistic seismic hazard assessment (PSHA). Since then, PSHA has been a standard practice in providing inputs to the design of buildings and critical infrastructure. The immediate output of PSHA is a hazard curve that provides annual exceedance rates for a range of ground-motion levels (e.g., PGA values between 10 and 1000 cm/sec2). The ordinate of a hazard curve can also be expressed in percentages for a given period (usually 50 years) assuming a Poissonian process. For example, annual exceedance rate of 1/2475 (where the denominator is the return period in years) corresponds to 2% probability of exceedance in 50 years (widely used percentage in national building codes). The development of hazard curves requires 1)identification of sources of seismicity and their characteristics, such as source geometry, activity rate, seismogenic depth, and maximum magnitude and 2) estimation of ground motion at the target using ground-motion prediction equations. An important aspect of PSHA is the treatment of uncertainties, which are grouped into the aleatory (or random) and epistemic uncertainties. The aleatory uncertainty deals with randomness in a PSHA element, which is usually the variability in a ground-motion intensity measure (e.g., variability in PGA). This type of uncertainty is treated by using a parameter, sigma, which is basically the standard deviation or the scatter of ground motions around a mean value. The epistemic uncertainty deals with our lack of certainty about an element of source or ground motion characteristics. For example, different activity rates can be considered for a seismic source, which are all included in hazard calculation by using a logic tree where each

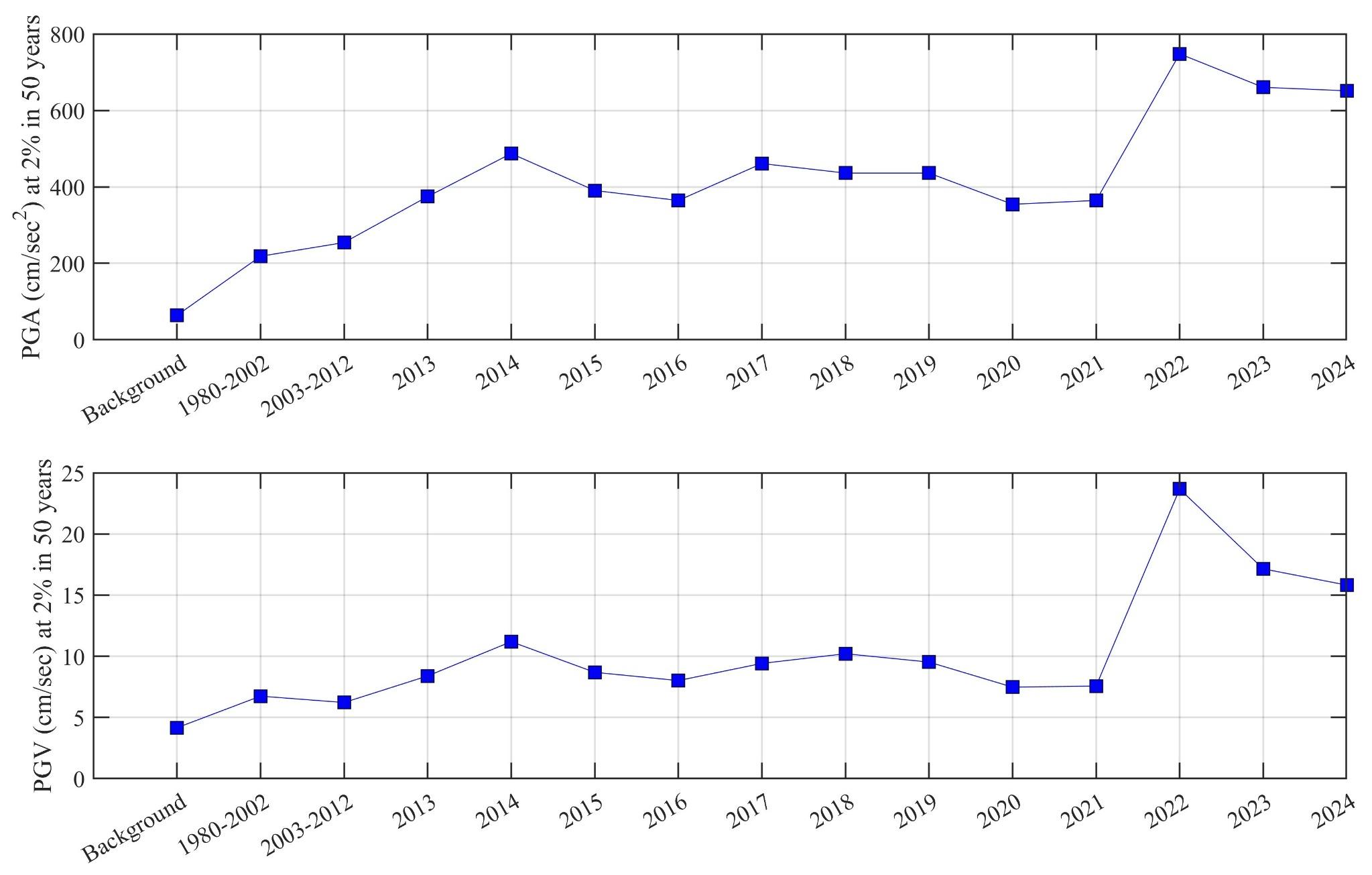

Figure 3. Peak ground acceleration (PGA) and peak ground velocity (PGV) in Fort St. John, British Columbia, for the probability of 2% in 50 years over time. Recreated from Babaie Mahani et al. (2025).

alternative is given a weight depending on our confidence in the alternative.

In Canada, NRCan has issued several updates to the seismic hazard map of Canada, with the most recent update being the sixth generation (CanadaSHM6) released in 2020. These maps, however, have not yet included induced seismicity and, therefore, their applicability for the WCSB is debated. Babaie Mahani et al. (2025) analyzed the variation in the level of seismic hazard for the city of Fort St. John, NE BC, due to induced seismicity over the past 40 years by performing PSHA based on Monte Carlo sampling. Their results (Figure 3) show an increase in both PGA and peak ground velocity (PGV) over the years, although the increase in PGA appears to be much larger. The peak ground motion occurs in 2022 (for both PGA and PGV), which corresponds to ~12 times increase in PGA compared to the baseline (considering only natural seismicity) value of ~60 cm/sec2 at the 2% probability of exceedance in 50 years. On the other hand, the 2022 PGV corresponds to ~5 times increase compared to the baseline value of ~4 cm/sec.

The development of hydrocarbon resources in the WCSB has fundamentally reshaped the region’s seismological landscape,

transforming an area once considered seismically quiet into one with multiple clusters of seismicity associated with hydraulic fracturing and wastewater disposal. The volume of injected fluids has the potential to influence the seismic character of the region for future decades, suggesting that parts of the WCSB should now be considered seismically active zones.

While significant progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms driving induced seismicity, critical gaps remain—particularly in hazard assessment and the development of effective mitigation strategies. The following two areas of research warrant special attention:

1) Developing predictive algorithms capable of forecasting significant “red light” events during or after industrial operations.

2)Integrating induced seismicity into PSHA frameworks to better evaluate and manage seismic hazard.

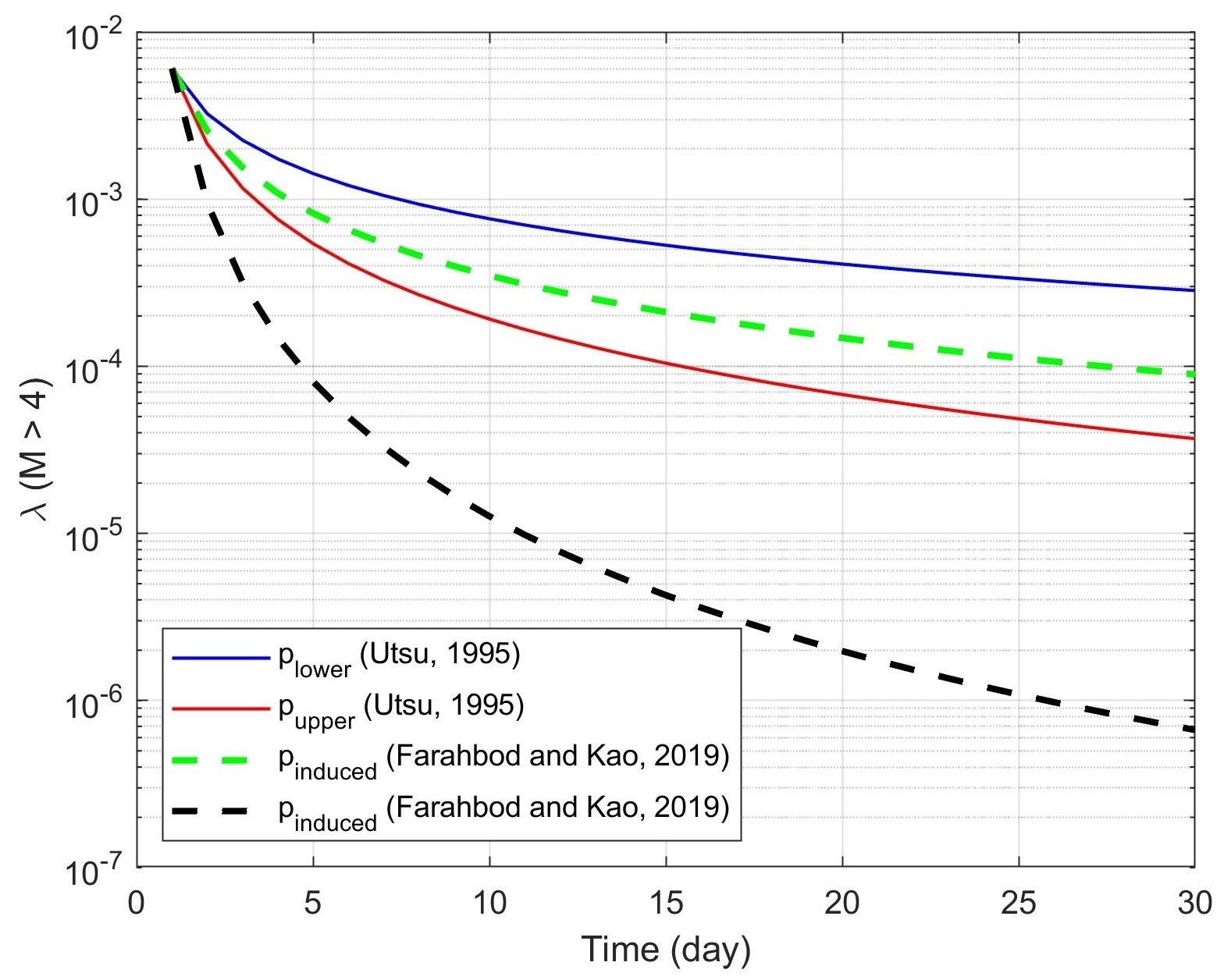

Predictive tools, whether physics-based, statistical, or machine learningdriven, are increasingly being explored to estimate the likelihood and potential magnitude of induced events following fluid injection. For example, Figure 4 demonstrates a physics-based approach grounded in two established seismological relationships: the Gutenberg–Richter law (Gutenberg and Richter, 1944), which relates magnitude to earthquake frequency, and the modified Omori law (Utsu et al., 1995), commonly applied to model aftershock decay. By combining these principles,

the figure illustrates the exceedance rate (λ)—the expected number of earthquakes with magnitude greater than 4—over time following hydraulic fracturing. The decay rate of seismic activity is strongly influenced by the “p-value” parameter in the modified Omori law, where higher p-values correspond to faster sequence decay. Although relatively simple, this approach offers valuable insight for monitoring and mitigation planning. More advanced predictive models (e.g., those leveraging machine learning) hold promise for providing more robust forecasts of induced seismicity.

Another critical area is hazard assessment. Current national seismic-hazard maps, while essential for long-term planning and regulation, do not account for induced seismicity. This omission can significantly underestimate seismic hazard in regions with a history of induced events, such as the WCSB. As shown in the section “Induced Seismicity Hazard Assessment,” sitespecific PSHA that incorporates historical inducedseismicity data produces much higher ground-motion estimates compared to national maps. To ensure public safety and regulatory compliance, site-specific PSHA that integrates induced-seismicity data, along with expert evaluation of associated uncertainties, is essential for informed decision-making and risk management in these regions.

Figure 4. Exceedance rate (λ) of M > 4 versus time for different p values for the global lower and upper limits and the two largest induced earthquakes in Northeast British Columbia (Farahbod and Kao, 2019).

I would like to thank Amy Fox and Neil Watson for their constructive comments and discussions about this paper.

Alberta Energy Regulator (2024). Directive 065: Resources Applications for Oil and Gas Reservoirs, https://static.aer. ca/prd/documents/directives/Directive065.pdf

Atkinson, G. M., Eaton, D. W., Ghofrani, H., Walker, D., Cheadle, B., Schultz, R., Shcherbakov, R., Tiampo, K., Gu, J., Harrington, R. M., Liu, Y., van der Baan, M., and Kao, H. (2016). Hydraulic fracturing and seismicity in the western Canada sedimentary basin. Seismological Research Letters, 87, 631-647.

Babaie Mahani, A., Kao, H., Walker, D., Johnson, J., & Salas, C. (2016). Performance evaluation of the regional seismograph network in northeast British Columbia, Canada, for monitoring of induced seismicity. Seismological Research Letters, 87, 648–660.

Babaie Mahani, A., Schultz, R., Kao, H., Walker, D., Johnson, J., & Salas, C. (2017a). Fluid injection and seismic activity in the Northern Montney Play, British Columbia, Canada, with special reference to the 17 August 2015 Mw 4.6 induced earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 107, 542–552.

Babaie Mahani, A., Kao, H., Johnson, J., & Salas, C. (2017b). Ground motion from the August 17, 2015, moment magnitude 4.6 earthquake induced by hydraulic fracturing in Northeast British Columbia. In Geoscience BC Summary of Activities 2016 (pp. 9–14). Geoscience BC, Report 2017-1.

Babaie Mahani, A., Esfahani, F., Kao, H., Gaucher, M., Hayes, M., Visser, R., & Venables, S. (2020). A systematic study of earthquake source mechanism and regional stress field in the Southern Montney unconventional play of Northeast British Columbia, Canada. Seismological Research Letters, 91, 195–206.

Babaie Mahani, A. and H. Kao (2020). Determination of Local Magnitude for Induced Earthquakes in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin: An Update, RECORDER, V.

45, No. 02, 12 pages, https://csegrecorder.com/articles/ view/determination-of-local-magnitude-for-inducedearthquakes-in-the-wcsb

Babaie Mahani, A., Venables, S., Kao, H., Visser, R., Gaucher, M., Dokht, R. M. H., & Johnson, J. (2021). Intensity of induced earthquakes in Northeast British Columbia, Canada. Seismological Research Letters, 92, 3482–3491.

Babaie Mahani, A. (2025). Audit Ground Motion Data Submitted to the BC Energy Regulator, BC Oil and Gas Research and Innovation Society, https://www.bcogris. ca/projects/audit-ground-motion-data-submitted-tothe-bcer/

Babaie Mahani, A., H. Kao, and K. Assatourians (2025). Variation in the Level of Seismic Hazard in Northeast British Columbia, Canada, Due to Induced Seismicity, Journal of Seismology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950025-10307-x

Cornell, C. A. (1968). Engineering seismic risk analysis. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 58, 1583–1606.

Esfahani, F., A. Babaie Mahani, and H. Kao (2024). Analysis of the Influential Factors Controlling the Occurrence of Injection-Induced Earthquakes in Northeast British Columbia, Canada, using MachineLearning-Based Algorithms, Journal of Seismology, Vol. 28, No. 5, p. 1489-1504, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10950-024-10248-x

Farahbod, A. M. and H. Kao (2019). Aftershock decay rate of large injection-induced earthquakes in northeast British Columbia: a case study for two sequences in the Montney play, CSEG Recorder, 44, 11 pages. Gutenberg, B. and C. F. Richter (1944). Frequency of earthquakes in California, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 34, 185–188.

Salas, C. J., Walker, D., & Kao, H. (2013). Creating a regional seismograph network in northeast British Columbia to study the effect of induced seismicity from unconventional gas completions. In Geoscience BC Summary of Activities 2012 (pp. 131–134). http:// cdn.geosciencebc.com/pdf/SummaryofActivities2012/ SoA2012_Salas_Seismograph_Network.pdf

Salas, C. J., & Walker, D. (2014). Update on regional seismograph network in northeastern British Columbia. In Geoscience BC Summary of Activities 2013 (pp. 123–126). http://cdn.geosciencebc.com/pdf/ SummaryofActivities2013/SoA2013_SalasWalker.pdf

Schultz, R. and V. Stern (2015). The Regional Alberta Observatory for Earthquake Studies Network, RECORDER, V. 40, No. 08, 4 pages, https://csegrecorder.com/assets/ pdfs/2015/2015-10-RECORDER-AB_Observatory_for_ Earthquakes.pdf

Visser, R., Smith, B., Kao, H., Babaie Mahani, A., Hutchinson, J., & McKay, J. (2017). A comprehensive earthquake catalogue for Northeastern British Columbia and Western Alberta, 2014–2016. Geological Survey of Canada Open File 8335, 28 pp. https://doi. org/10.4095/306292

Visser, R., Kao, H., Smith, B., Goerzen, C., Kontou, B., & Dokht, R. M. H. (2020). A comprehensive earthquake catalogue for the Fort St. John-Dawson Creek region, British Columbia, 2017–2018. Geological Survey of Canada Open File 8718, 28 pp. https://doi. org/10.4095/326015

Visser, R., Kao, H., Dokht, R. M. H., Babaie Mahani, A., & Venables, S. (2021). A comprehensive earthquake catalogue for Northeastern British Columbia: The Northern Montney Trend from 2017 to 2020 and the Kiskatinaw Seismic Monitoring and Mitigation Area from 2019 to 2020. Geological Survey of Canada Open File 8831, 23 pages. https://doi.org/10.4095/329078

The Bow Sky Garden Auditorium, Calgary

The Canadian Energy Geoscience Association is proud to introduce the Reservoir Symposium, a biennial event that focuses on the core theme of Reservoir Characterization. Designed to engage a broad audience, the event highlights practical, impactful work that advances our understanding and development of subsurface reservoirs.

Our 2026 theme, Reservoir Characterization for Energy Security, underscores the essential role geoscientists play in securing a resilient and diverse energy future for Canada. Energy security isn’t just about resources, it’s about innovation, collaboration, and leadership.

This two-day symposium will showcase impactful, practical work from across the energy sector, featuring presentations on both proven and emerging subsurface techniques that are shaping Canada’s energy landscape.

Join us for four technical sessions spotlighting key plays, technologies, and industry topics that demonstrate how geoscientists are driving the future of energy security through reservoir characterization.

This session investigates the cutting-edge technology revolution transforming reservoir characterization, underpinning advancements in traditional oil and gas efficiency, and driving the emergence of low-carbon pathways such as CCUS and geothermal. Explore how these innovative tools and workflows are leveraging data in new and innovative ways, reducing uncertainty, and enhancing decision-making in support of our collective goal for a more sustainable, affordable, and secure energy system. By showcasing strategic innovations

that are improving our geoscientific understanding, this session highlights the tools and techniques that are making Canada’s long-term energy vision a reality.

This session aims to explore the innovative strategies operators are using to unlock the full potential of tight, unconventional reservoirs. Previously overlooked tight formations, such as the Montney, Duvernay and Deep Basin tight sand formations, have become the backbone of oil and gas development in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. Case studies and insights on optimizing production, managing complex reservoir heterogeneity and overcoming operational challenges make this session essential for operators to thrive in this evolving landscape of unconventional resource development. Micro and nano darcy rock is not for the faint of heart!

This session explores the complexities of subsurface injection, where pore space is increasingly relied upon for carbon capture and storage (CCS), saltwater disposal, and

other extraction and injection-related applications. With a focus on the geological controls governing injectivity, containment, and pressure response, this session will highlight insights into induced seismicity, reservoir characterization, and plume migration. Discussions will also touch on the cumulative impacts of concurrent injection activities and the evolving geomechanical and hydrogeological frameworks required to assess long-term pore space performance. The session brings together geoscientists working at the forefront of injection-related challenges to chart a path toward responsible and informed subsurface utilization.

This session will highlight advances in reservoir characterization of heavy oil reservoirs and different approaches being utilized across industry. In-situ oil sands of western Canada have been contributing to Canadian oil production as a key hydrocarbon resource for more than 20 years. Despite more than 20 years of production, with respect to the complexity of fluvial and shallow marine depositional systems, reservoirs of heavy oil remain equivocal in some respects. Reservoir characterization with recently advanced techniques can help to investigate reservoirs in more detail to increase production efficiency.

XRF AND XRD IN GEOLOGY: ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES, DATA

INTERPRETATION AND INTEGRATION & INDUSTRY BEST-PRACTICES Short Course

Wednesday, November 12 - Thursday, November 13, 2025

8:30 AM - 4:30 PM

Instructors: Giovanni Zanoni, Rohmtek & Milly Wright, Rohmtek

Location: CEGA Conference Room

Online registration closes: November 5, 2025

GEOLOGY FOR NON-GEOLOGISTS Short Course

Thursday, November 20, 2025

8:30 AM - 4:30 PM

Instructor: Michael Webb, Michael Webb Geoconsulting

Location: Calgary Petroleum Club

Online registration closes: November 13, 2025

UPDATED CAMBRIAN CORE WORKSHOP Short Course

Wednesday, January 14, 2026

9:00 AM - 4:00 PM

Instructors: David Herbers, Alberta Geological Survey, Tyler Hauck, Alberta Geological Survey & John B

Gordon, Spectrum Geosciences Ltd

Location: AER Core Research Centre

Online registration closes: January 8, 2025

INTRODUCTION TO GEOCHEMISTRY Short Course

Thursday, February 12, 2026

8:30 AM - 4:30 PM

Instructor: Martin Fowler

Location: Calgary Petroleum Club

Online registration closes: February 5, 2026

DRILL CUTTINGS ANALYSIS COURSE & WORKSHOP Short Course

Wednesday, February 25- Thursday, February 26, 2026

8:30 AM - 4:30 PM

Instructor: Andy Hubley, AWH Energy Services Ltd.

Location: Calgary Petroleum Club

Online registration closes: February 18, 2026

In parts 1 and 2, we examined the strategic petroleum targets of both the German and Japanese military during World War II (WWII). In part 3, we examine the logistics of keeping the machines of war fueled. As we have discussed, securing access to petroleum reserves was essential, but if the fuel could not reach the vehicles, the success of military operations would be severely hindered. Both the Allied and Axis powers encountered logistical challenges in maintaining a steady fuel supply for their forces. This need led to the development of extensive infrastructure, including pipelines, naval convoys, and groundbreaking innovation (Yergin, 1991).

The Battle of the Atlantic was a crucial struggle to ensure the safe transportation of supplies across the Atlantic Ocean, supporting the Allies. The United States served as the leading supplier of oil to Allied Europe, making Atlantic oil convoys a vital lifeline for the region. Naval convoys escorting oil tankers came under near-constant threat from German U-boats, which sought to sever that lifeline (Blair, 1975).

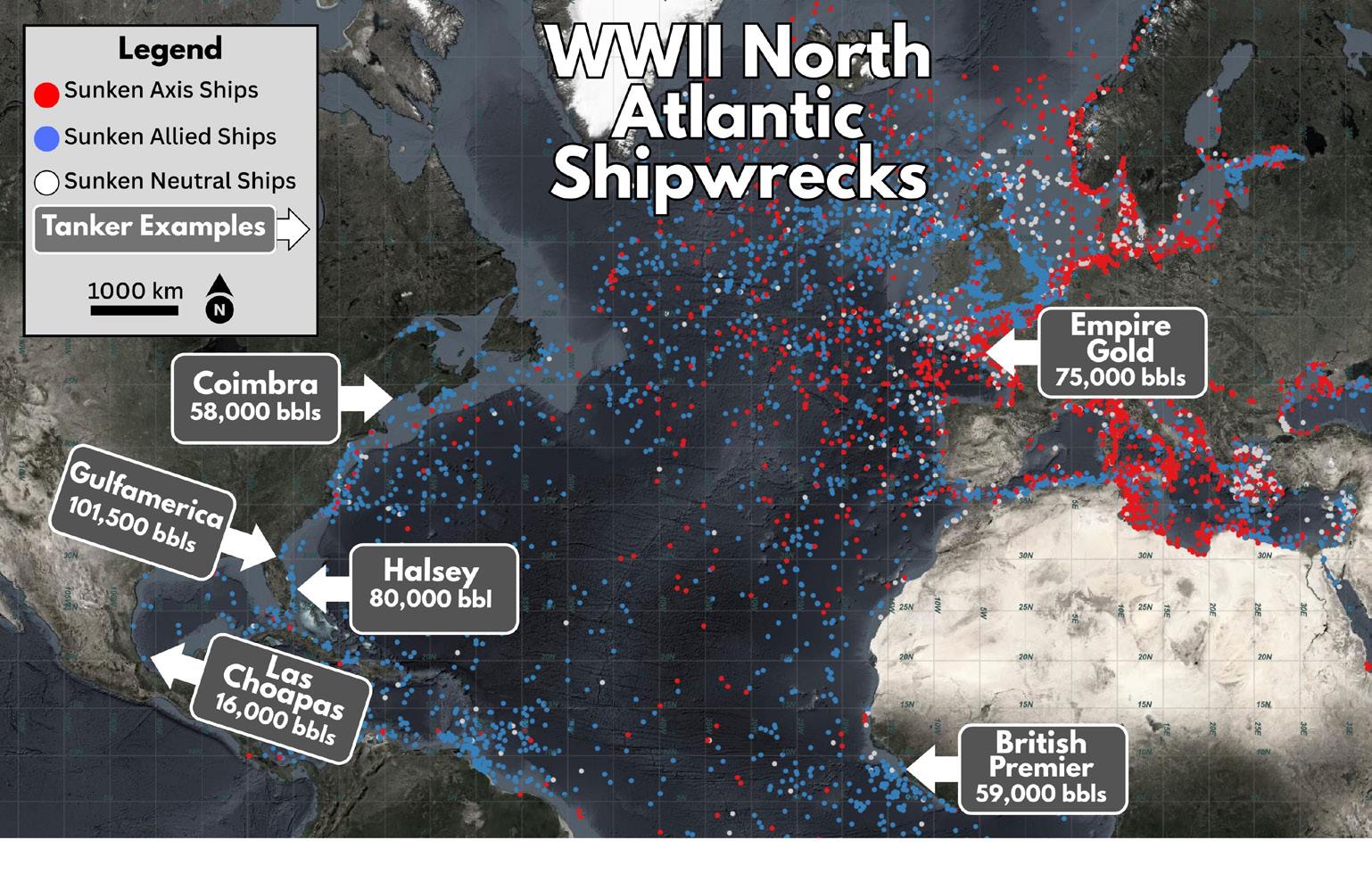

Losses were heavy in the early years of the war. Between December 1941 and June 1942 alone, the Allies lost over 4.5 million gross tons of shipping, including nearly 1.5 million gross tons of tanker capacity (HyperWar, n.d.). These numbers represent ship tonnage, but they also translate directly into oil and fuel being lost at sea from naval sabotage. To illustrate the scale of these losses, here are a few examples of tankers lost to German U-boat attacks, showing how each loss deprived the Allies of critical fuel: Halsey went down carrying about 80,000 barrels of naphtha and heating oil (U-boat. net, 2025a); Gulfamerica was lost with about 101,500 barrels of furnace oil (U-boat.net, 2025b); Empire Gold was torpedoed with

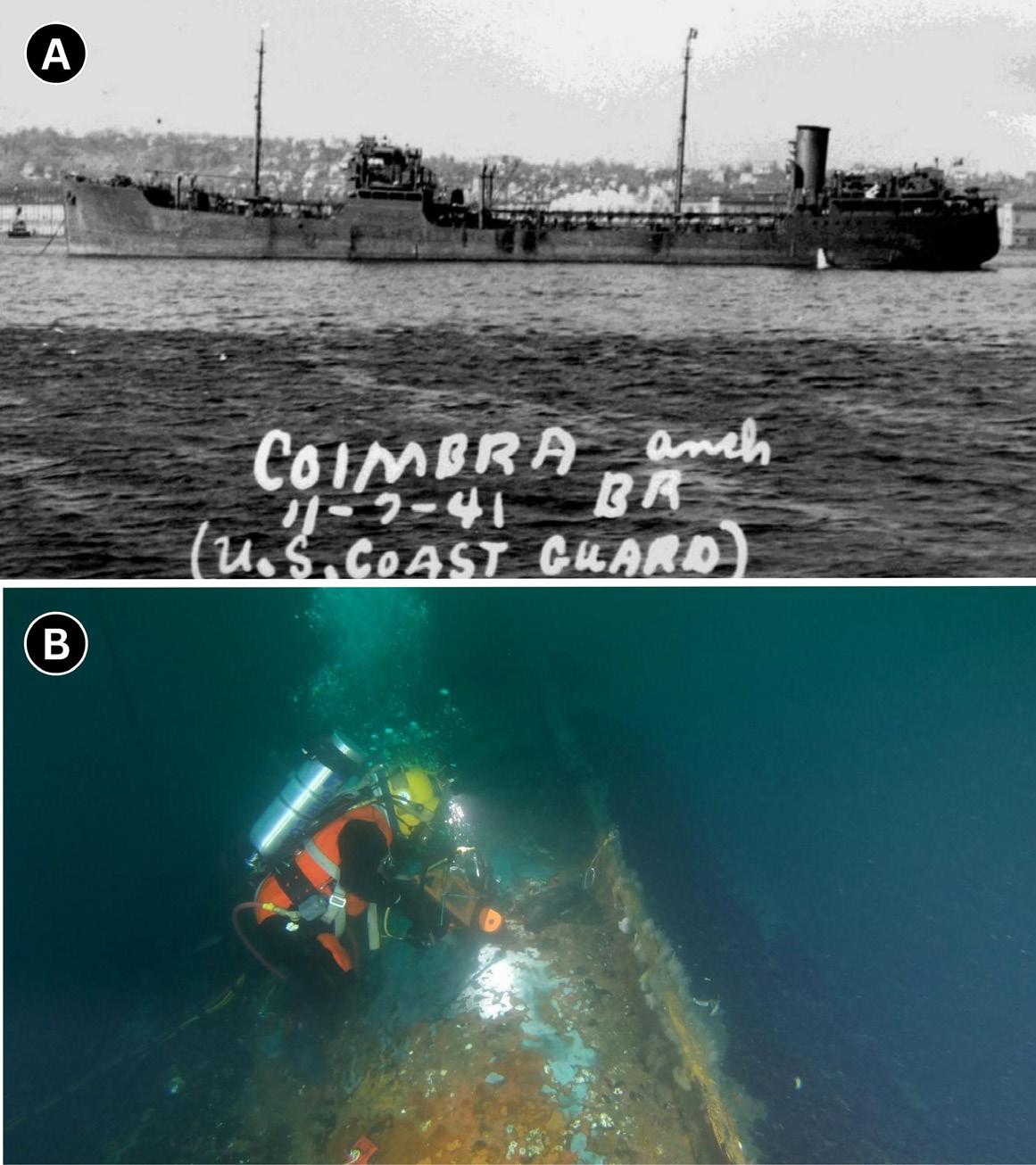

approximately 75,300 barrels of motor spirit (Uboat.net, 2025c); British Premier was sunk carrying about 59,000 barrels of crude oil (U-boat.net, 2025d); Las Choapas was a Mexican tanker that was torpedoed with 16,000 barrels of crude oil (U-boat.net, 2025e); and Coimbra was destroyed off Long Island in January 1942 with roughly 48,000 barrels of fuel oil (Uboat.net, 2025f). Eventually the Allies were able to change their fortunes in the Battle of the Atlantic through technological and tactical improvements, such as enhanced convoy escort forces, air patrols, radar, and cryptography (Blair, 1975; HyperWar, n.d.). This helped secure a more stable flow of oil across the Atlantic.

The aftermath of the Battle of the Atlantic left a significant environmental challenge, largely due to the large number of sunken oil tankers. Heersink (2022) compiled all known shipwreck datasets and has mapped more than 15,000 WWII shipwrecks worldwide (Figure 1). Of these ships, 474 tankers were sunk during the Battle of the Atlantic, including both Allied and Axis tankers.

Occasionally, the oil in the tankers would burn up during the attacks; however, they could also sink with the petroleum cargo intact within the ship. While the exact percentage is unknown, a surprising number of the sunken vessels still contain stored oil. The oil stranded in these shipwrecks is an ongoing environmental concern as the ships deteriorate and increase the potential for leaks. Environmental organizations, such as Project Tangaroa, have ongoing projects aimed at mitigating these potential environmental disasters and recovering petroleum from these wrecks (Project Tangaroa, n.d.).

The aforementioned SS Coimbra is one example of a tanker that was sunk with its oil cargo largely intact (Figure 2). It was a British oil tanker carrying thousands of barrels of lubricating oil destined for Allied forces in Europe. It was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-123 off the coast of Long Island, New York, on January 15, 1942 (Helgason, 1996), where it sank to approximately 55 meters water depth. In 2019, the U.S. Coast Guard and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration studied the wreckage of the Coimbra to assess the risk of oil leakage. In 2020, specialized crews successfully removed nearly 450,000 gallons of oil from the wreck, preventing further contamination of the Atlantic ecosystem (NOAA, 2020).

Heersink (2022) also mapped a large quantity of shipwrecks in the South Pacific, battles which revolved around crucial resources, such as petroleum. He has mapped 320 sunken oil tankers in the Pacific, with the majority of these sunk in the vicinity of the South Pacific islands, and the oilfields they served. In part 2 of this series (Laycock et al., 2025), we examined how these battles largely revolved around securing petroleum to fuel Japan’s imperialist expansion, underscoring the crucial importance of securing access to oil during WWII.

Figure 1: Map of North Atlantic shipwrecks from WWII (Heersink, 2022), showing distribution of Allied and Axis shipwrecks. Also annotated are some examples of Allied sunken tankers and the volume of petroleum products they were carrying at the time.

Figure 2: A) Image of British tanker Coimbra. It was carrying >2 million gallons of oil when it was torpedoed by a German U-boat off the coast of Long Island, New York on January 15, 1942. Much of the oil survived the explosion and sank with the ship. Public domain image released by U.S. Coast Guard.

B)Diver drills into the hull of Coimbra in May of 2019 in an attempt to safely remove oil that was slowly leaking into the ocean. Public domain image released by U.S. Coast Guard.

With the outbreak of war, German U-boats began targeting Allied shipping, sinking hundreds of oil tankers in an attempt to starve Britain of fuel (Morison, 1947).

Under the Lend-Lease program, the U.S. provided petroleum to the Soviet Union, requiring increased security for transatlantic convoys (Yergin, 1991).

The Allies responded to the U-boat threat by organizing convoys with naval escorts and deploying escort carriers to protect oil tankers (Roskill, 1954).

Advances in anti-submarine warfare, including sonar, air patrols, and codebreaking, significantly reduced U-boat effectiveness. By mid-1943, the Allies had gained the upper hand, ensuring a more stable flow of oil to Europe (Morison, 1947).

In addition to American oil, the Allies also relied heavily on oil sourced from Latin America. In the early 1940s, Venezuela emerged as one of the world’s largest oil producers. Its proximity to Atlantic shipping routes and the massive refineries at Aruba and Curaçao made Venezuelan crude especially convenient and useful. These refineries converted heavy crude into aviation gasoline, a product in high demand for both the European and African campaigns (Yergin, 1991).

Venezuela’s oil production during WWII was both strategically and politically significant. Although the country initially declared neutrality in 1939, President Isaías Medina Angarita (Figure 3) shifted his alliance decisively toward the Allies after Pearl Harbor, freezing Axis assets and granting the U.S. military temporary access to Venezuelan bases (Grisanti, 2015). Venezuelan oil production climbed from 539,000 barrels per day in 1939 to 622,000 barrels per day in 1941 before dropping due to heavy U-boat attacks in 1942 (Grisanti, 2015). Venezuela worked to protect oil infrastructure with improved coastal defenses and naval convoys. By the end of the war, Venezuelan oil production increased to 885,000 barrels per day, providing key resources to the Allies (Grisanti, 2015).

Mexico also contributed, supplying petroleum products and lubricants despite the disruptions that followed its 1938 nationalization of the oil industry (Wilkins, 1974). Smaller, but still important, contributions came from Columbia, whose Barrancabermeja refinery supported U.S. bases in the Caribbean and along the Panama Canal, ensuring fuel supply to one of the most strategically important corridors of the war (Randall, 2005).

In 1942, German U-boats were especially effective at interrupting the flow of oil from the Caribbean corridor, sinking dozens of tankers carrying Venezuelan and Mexican oil (see Las Choapas, Figure 1). German submariners referred to this period as the “Second Happy Time,” as they enjoyed unusually successful U-boat operations along the U.S. East Coast and the Caribbean Sea (Blair, 1975). In an effort to improve the safety of these shipments, the U.S. Military strengthened its defense of the area to safeguard the oil lifeline (Blair, 1975).

Figure 3: Photograph of Isaías Medina Angarita, president of Venezuela from May 1941 to October 1945. He was a key figure in aligning with the Allies after Pearl Harbor and providing oil for the Allied war efforts.

Image courtesy the Biblioteca Nacional de Venezuela.

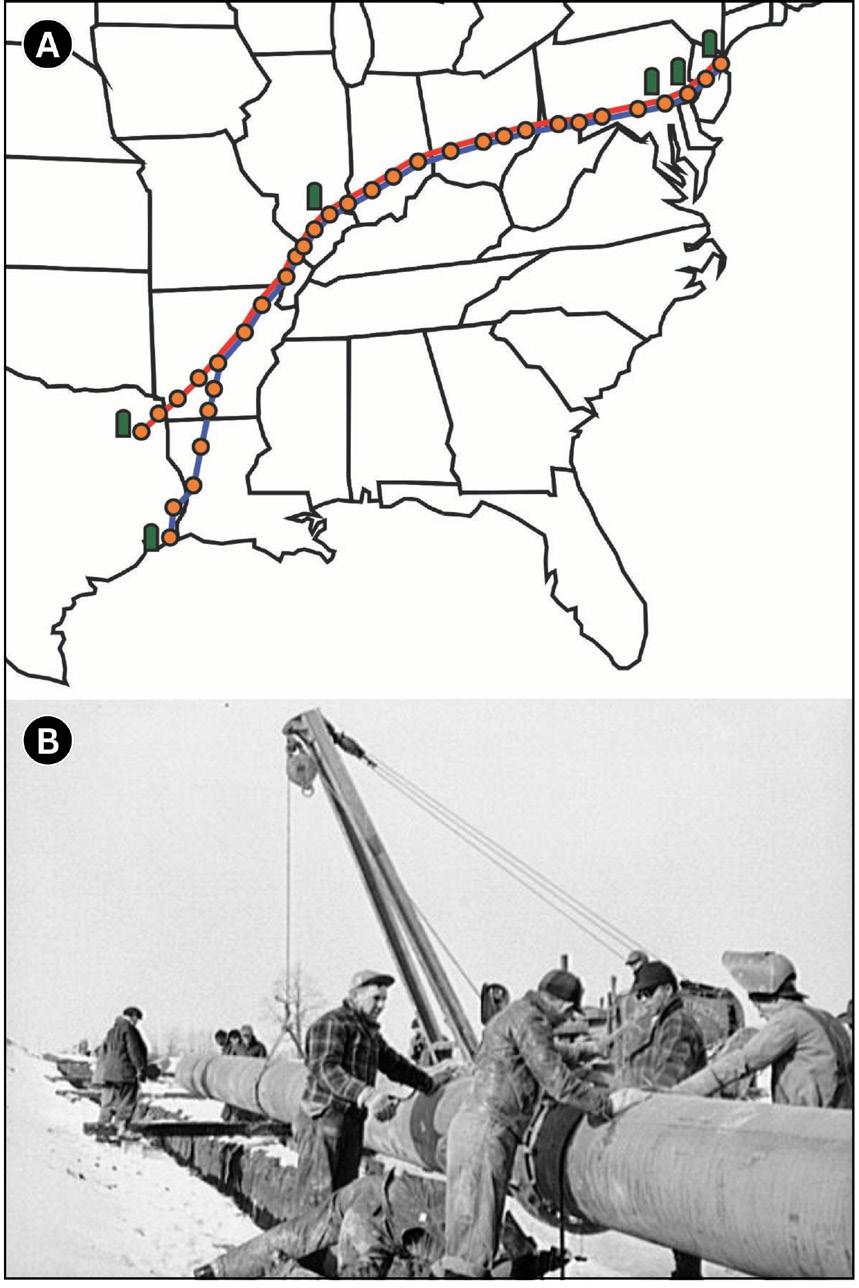

Figure 4: A) Map of the Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines. The red line represents the Big Inch pipeline. The blue line represents the Little Inch pipeline. Orange circles are pumping stations, and the green rectangles are storage tank farms.

B)Photograph of workers constructing the Big Inch pipeline.

Image by John Vachon - Image courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Transporting oil over large distances is most effectively and efficiently done through pipelines. During WWII, the Allies undertook several major pipeline projects to ensure that battlefronts remained well-supplied with oil. In the continental U.S., the Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines were constructed to deliver oil from Texas to the Atlantic coast, where it was loaded into oil tankers.

The 1,254 mile long, 24-inch diameter “Big Inch Pipeline,” constructed between 1942 and 1943, transported crude oil from northeast Texas production fields to refineries in the Northeast (Figure 4). It was one of the largest pipeline projects of its time (Steiner, 1946). The smaller 20-inch diameter companion “Little Inch Pipeline” was built from 1943 to 1944 (Figure 4) to supplement oil delivery to the Atlantic coast from production fields in southeast Texas.

Leading up to D-Day in Europe, engineers needed to innovate ways to supply the troops with oil as they advanced into Europe. One of the most significant and innovative was the “Pipeline Under the Ocean”, or PLUTO. British engineers designed and constructed enormous barrel-shaped spools of flexible pipeline and deployed them on the ships that laid the pipeline across the English Channel. The PLUTO system consisted of a series of pump stations designed to transport fuel over 100 miles along the seafloor from the British mainland to Allied forces in continental Europe. Construction began in 1943 and was operational by June 1944. The success of PLUTO reduced reliance on vulnerable supply ships and was instrumental in supplying soldiers with a steady stream of fuel for their vehicles and machinery as they advanced deeper into occupied territories following the D-Day landings (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Images from the PLUTO project.

A)Image shows a “Conundrums” that was fully coiled with pipe. These were used to coil and unload the pipe into the ocean. This photograph comes from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

B)Image shows one of the Conundrums being towed and the pipeline being unspooled into the ocean. This photograph comes from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

C)Map showing the location of the PLUTO pipeline projects.

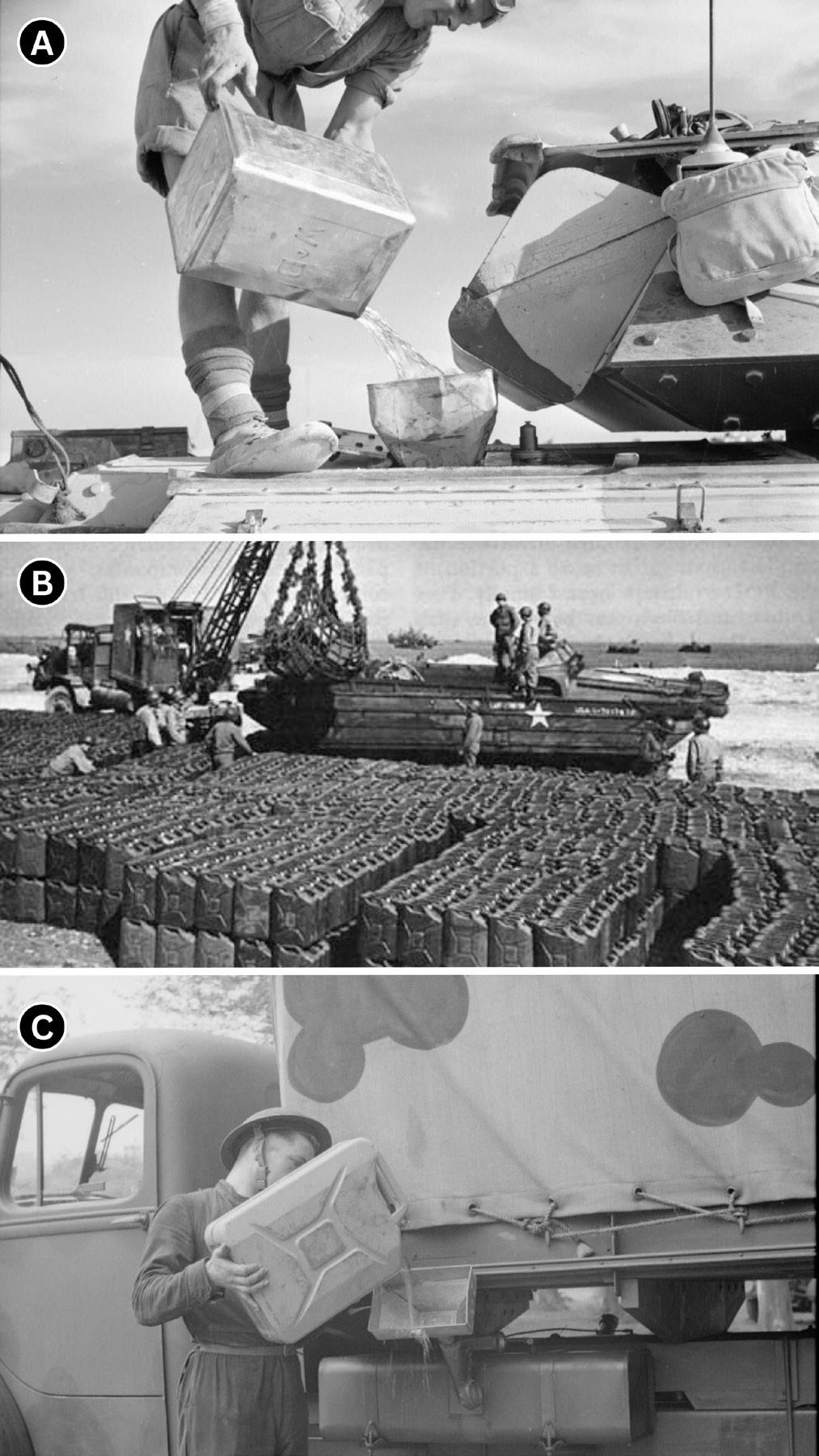

When considering the logistics of moving oil and fuel around during WWII, not to be overlooked are the smaller-scale aspects of transporting and actually filling the vehicles. One of the most critical examples of this is the humble fuel can. Early British and American forces relied on so-called “tombstone cans,” which were square, prone to leaking, and difficult to stack (Figure 6). In North Africa, as much as 50 percent of the overall fuel supply was lost to evaporation or spillage due to the use of these inadequate containers (Yergin, 1991; Overy, 1995).

The Germans, by contrast, had developed the now-famous “jerrycan” (derived from the British slang term “Jerry” for Germans), officially known as the Wehrmacht-Einheitskanister (literally, “armed forces standard canister”). It was designed in 1937 by engineer Vinzenz Grünvogel and featured several innovations that significantly enhanced its effectiveness. It was airtight, stackable, had an internal air chamber that allowed for heat expansion, and its wide mouth and built-in breather pipe enabled rapid pouring. It also featured a distinctive threehandle design, which allowed it to be carried by one or multiple soldiers, made pouring easier, and allowed a chain of men to pass them efficiently along a line (Shirer, 1960; Beckett, 2008).

The Allies first encountered jerrycans during the 1940 Norwegian campaign and recognized the superior design. American engineer Paul Pleiss had even brought a sample out of Germany before the war, but the initial U.S. Army bureaucracy resisted adopting the foreign design. By 1942, Allied production lines began mass-producing jerrycans (Beckett, 2008). By 1944, the U.S. alone had produced tens of millions of jerrycans for fuel and water, making them almost as indispensable as the jeeps and trucks they supplied. More than just a container, the jerrycan became a symbol of efficient frontline logistics, one whose design remains globally influential to this day (Beckett, 2008).

WWII was a conflict that centred around political ideologies and aggressive expansion. However, oil played a central role in the conflict, as a significant part of the military strategy involved the fight to fuel the armed forces. WWII was more mechanized than previous wars and did not rely on coal, literal horsepower, and manpower in the same ways that World War I and other global conflicts of the past had. WWII required nations to secure multiple supplies of petroleum to sustain their military operations. From the rolling tanks of the German Wehrmacht to the aircraft carriers of the U.S. Navy, oil was the key enabler of warfare in the 20th century (Yergin, 1991). Even some of the American propaganda from the era echoed this reality, with U.S. posters showing support for the oil industry (Figure 7).

Ultimately, oil was not just a commodity; it was a strategic weapon. The ability to ensure a continuous supply of petroleum and transporting it safely to military forces played a critical role in the success of military campaigns. For the Axis powers, the scarcity of petroleum significantly weakened them as the war progressed. Understanding the role of oil in WWII offers a deeper appreciation for the complex interplay of geopolitics, finite energy resources, logistics, and military strategy that shaped the course of history, and continues to this day.

Figure 6: A) British soldier in North Africa in 1942 using a four-gallon tin to fill a Crusader Tank. These were soon replaced with copies of the German’s fuel can, as seen in the next panels. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

B)This image shows preparations for D-Day in 1944, in Slapton Sands, Devon, England. Hundreds of Jerrycans are stacked on the beach.

C)Image from June 1943, a British soldier fills his truck using a jerrycan.

Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

Barnett, C. (1983). The desert war: The North African campaign, 1940–1943. Cassell. Barnhart, M. A. (1987). Japan prepares for total war: The search for economic security, 1919–1941. Cornell University Press.

Beckett, I. F. W. (2008). The British Army and the First World War. Cambridge University Press.

Bellamy, C. (2007). Absolute war: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. Knopf. Blair, C. (1975). Hitler’s U-boat war: The hunters, 1939–1942. Random House. Dallek, R. (1995). Franklin D. Roosevelt and American foreign policy, 1932–1945. Oxford University Press.

D’Olier, F., Ball, R. F., & Galbraith, J. K. (1947). The United States Strategic Bombing Survey: Oil Division final report. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Erickson, J. (1975). The road to Stalingrad. Cassell.

Ferrier, R. W. (1982). The history of the British Petroleum Company: Volume 1, The developing years, 1901–1932. Cambridge University Press.

Glantz, D. M. (1998). Stumbling colossus: The Red Army on the eve of World War II. University Press of Kansas.

Glantz, D. M., & House, J. M. (1995). When titans clashed: How the Red Army stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas.

Grisanti, L. X. (2015, November 1). Venezuela’s oil: Crucial in World War II. AAPG Explorer. American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://www.aapg.org/news-and-media/details/explorer/articleid/23615/venezuelasoil-crucial-in-world-war-ii#:~:text=Venezuela%20had%20been%20increasing%20 its,of%20622%2C000%20barrels%20per%20day

Heersink, P. (2022). Sunken ships of the Second World War [Dashboard]. ArcGIS. https:// www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/fe88b5e18c6443c7afaf6e32f8432687

Helgason, G. (1996). SS Coimbra. Uboat.net. Retrieved from https://uboat.net/allies/ merchants/ship/1298.html

Hinsley, F. H. (1993). British intelligence in the Second World War, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press.

Iriye, A. (1987). The origins of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific. Longman. Jackson, A. (2004). The British Empire and the Second World War. Hambledon Continuum.

Kelly, S. (2011). The oil kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia changed the balance of power in the Middle East. Simon & Schuster.

Matloff, M. (1959). Strategic planning for coalition warfare, 1943–1944. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Mawdsley, E. (2005). Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941–1945. Bloomsbury. Miller, D. (2014). The strategic bombing of Germany, 1940–1945. Pen & Sword Books. Miller, K. (2014). Big Inch and Little Big Inch: The battle to build the World War II fuel pipelines. Texas A&M University Press.

Morison, S. E. (1947). History of United States naval operations in World War II: The battle of the Atlantic. Little, Brown and Company.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2019). Assessment of the Coimbra shipwreck and oil spill risk. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://response.restoration. noaa.gov

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2020). Final report on oil recovery from the SS Coimbra wreck site. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://response. restoration.noaa.gov

Figure 7: Two examples of American propaganda posters showing support for the oil industry.

Both Images courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Nunn, P. D. (2005). Geology and geomorphology of Pacific islands: Plate tectonics, sea-level change and geomorphic response. Earth-Science Reviews, 70(3–4), 157–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.07.006

Overy, R. (1995). Why the Allies won. W. W. Norton & Company.

Pack, M. (1971). Operation Compass, 1940. Ian Allan Publishing.

Penrose, E. (1970). The large international firm in developing countries: The international petroleum industry. George Allen & Unwin.

Playfair, I. S. O. (1956). The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume II: The Germans come to the help of their ally. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Project Tangaroa. (n.d.). Project Tangaroa. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https:// www.project-tangaroa.org

Randall, S. J. (2005). United States foreign oil policy since World War I: For profits and security. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Roskill, S. W. (1954). The war at sea, 1939–1945, Volume II. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Saunders, H. (1954). The secret war: The story of the PLUTO pipeline. Brassey’s. Shirer, W. L. (1960). The rise and fall of the Third Reich: A history of Nazi Germany. Simon & Schuster.

Spector, R. H. (1985). Eagle against the sun: The American war with Japan. Free Press. Steiner, H. (1946). Pipelines to victory. Harper & Brothers. Stinnett, R. B. (2000). Day of deceit: The truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor. Free Press. Tatsumi, Y. (2006). Geochemical and petrological constraints on the origin of arc magmas in Japan. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 151(1–3), 57–70. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.07.037

Tooze, A. (2006). The wages of destruction: The making and breaking of the Nazi economy. Penguin Books.