20 / INSTRUMENTAL FACTS Augmented GPS By Ed McDonald

22 / UNUSUAL ATTITUDES Pitts stop in Iceland

26 / VECTORS

27 / RIGHT SEAT

28 / PEP TALK

Peppler

30 / COLE’S NOTES Remember the passenger By W.T. (Tim) Cole

50 / BOOKSHELF

52 / SERVICE CENTRE

54 / FLIGHT BAG

ON THE COVER Harbour Air’s eBeaver was a hit at AirVenture 2024 in July. Photographer Aaron Burton captured the revolutionary aircraft on the move at the Oshkosh seaplane base.

Seventy-four years on, there are still questions without answers. By

Dirk Septer

Six outstanding contributors to Canada’s aviation industry are profiled in this issue. Contributed by Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame

Whether you work in a cockpit or on the apron, hearing protection is vital. By Katie Koebel

Readers of this space will know that I am a critic of the state of the Royal Canadian Air Force — a force with a proud history that goes back a hundred years. That it has evolved from a force that at one time trained much of the world’s fighter and bomber pilots into one that can’t complete the training of its own fighter pilots due to a lack of appropriate aircraft and is looking to others to fill the gap only serves to illustrate the sorry state of today’s RCAF.

It’s easy to blame the current federal governing party for this situation. However, the degradation of the force began years ago and has been continued by governments of both federal parties. One must also recognize that for decades voters hadn’t considered defence a priority, so the federal political parties adjusted accordingly. The attitude that “The Americans will protect us,” wasn’t just present

among politicians — it was prevalent in voters’ minds as well.

As I write this, a week has passed since returning from AirVenture 2024 at Oshkosh, Wisconsin (hence the delay in getting this issue to the press and the resultant delay in getting it to your newsstand or mailbox). Of all the marvelous and awe-inspiring feats of pilot skills on display at the annual aviation extravaganza, my attention was drawn to the performances put on by various air forces.

The U.S. Navy put on a great show with a pair of their Boeing EA-18G Prowlers (a variant of the F/A-18 Super Hornet) performing impressive slow- and highspeed manoeuvres. Then came the U.S. Air Force’s F-22, a 5th-generation fighter so advanced in its capabilities that it hasn’t been sold to foreign powers. Its raw power and incredible manoeuvrability, especially at slow speeds, seem to defy physics.

After that it was the Canadians’ turn, and the show started high above with the CAF Skyhawks parachute team, their chutes replicating Canada’s Maple Leaf Flag. Then the RCAF’s CF-18 took to the sky. What followed was truly astounding — pilot Captain Caleb ‘Tango’ Robert came close to replicating many of the physics-defying low-speed manoeuvres of the vastly superior F-22, and he did it through skill rather than with the aid of brute horsepower.

The Snowbirds finished the Canadian portion of the airshow, and the reception by the mostly American crowd was proof of their enduring popularity — the best exhibition of multi-aircraft formation flying at the greatest airshow on Earth — or anywhere else.

This Canadian left the show proud — of the men and women who serve in today’s Royal Canadian Air Force.

I really appreciate the high-quality coverage provided in Canadian Aviator. I rely on the articles and photography of your offering to keep me updated on newsworthy happenings in Canadian aviation. The honest reporting with no bias is refreshing and I rely on the information you provide to give me a feeling for all aspects, events and changes to flying that are meaningful in our vast airspace. Thank you.

Ken Armstrong Victoria, BC

I worked on the Mid-Canada Line. My job didn’t involve flying, but I managed to snag a few flights. Every day, the helicopters, mainly Sikorsky S-55s, were out, up and down the line. Surely there were a lot of good flying stories created. Are any of those pilots still around? I’d love to hear their stories.

Bruce Jorgenson Gilbert Plains, Man.

So would we, Bruce. – Ed.

I really enjoy reading Canadian Aviator and will look forward to three more years of aviation stories. Thank you for putting out such a great magazine.

Tyrone Butler Powell River, BC

I very much enjoyed Mireille Goyer’s article, “The Perils of Transitioning” (Right Seat, May/ Jun 2024). It provides a great perspective on making the transition to a new aircraft smooth, safe and enjoyable. A far cry from the olden days of “kick the tire, light the fire and go,” the sage advice and practical examples of transition training she provides can benefit pilots at all levels. In particular, I fully concur with Mireille’s note that a humble mindset is essential. The gods of aviation do not look kindly upon brash aviators possessing a baseless self-confidence.

Ted Delanghe, Regina, Sask.

Canadian Aviator welcomes reader letters on topics of concern to Canadian pilots and the aviation industry. Please be brief, to the point and polite in your submissions.

Email the editor steve@canadianaviator.com

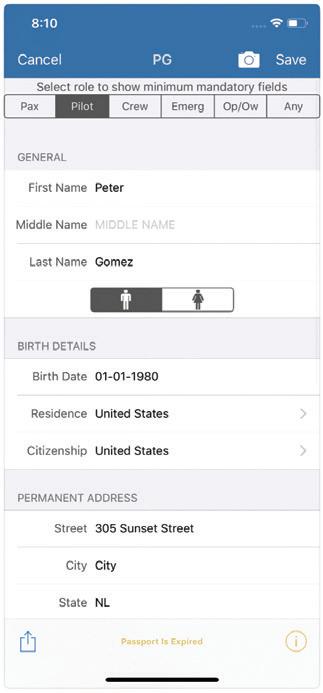

Are you frustrated using the U.S. government’s electronic Advance Passenger Information System (eAPIS) website to register your arrival and departure into that country or to and from Mexico? Finding it inconvenient at times to find a computer to file an eAPIS arrival or departure report? This app might be just the thing you need. FlashPass is a very user-friendly U.S. government approved iPhone/ iPad app that allows reports to be made on the fly, eliminating the need for a computer. Enter pilot and passenger data once and simply click to add to manifests. Ditto for destinations, etc. A free 30-day trial is offered, single-trip manifests are U$9.99 each or five for U$39.99. Annual subscription is U$78.00. (User support is excellent. –Editor) Learn more at flashpass.net. Available on Apple’s App Store.

Have or building an aircraft in the amateur-built category? Need a new radio? Have limited panel space available? July of this year Garmin announced two new slimline COMM radios for the experimental market. Similar to the GTR 205 Comm introduced in early 2024, the U.S.-based avionics manufacturer is now offering the panel-mounted GTR 205x and the remote-mounted GTR 205xR. Both feature a built-in stereo intercom and have Bluetooth capability, even offering a display of the song and artist on the radio’s display. Around U$ 2,200. Learn more at garmin.com. Available from Garminauthorized avionics shops.

Wondering what to get that special aviatrix in your family? It’s true that Mother’s Day has long past, but Christmas is coming up, and watchmaker Abingdon has the perfect gift idea –their White Amelia Ladies E6B Watch. The device is chock full of all the typical E6B functions, dual time zone displays, and it provides Zulu time conversion. The leather watch strap and the watch face are white, the case is stainless steel. Diameter is 40 mm. Other colour combinations are available. About U$377. Learn more at, and available from, mypilotstore.com

Need a simple, light-weight and cost-effective portable antenna for your in-cockpit portable device? Want the added benefit of a larger selection of navigation satellites to enhance position accuracy while minimizing potential signal degradation or interference? Then consider Garmin’s GLO 2 for Aviation. It receives signals from both the American GPS and the Russian GLONASS satellite constellations, adding 24 more satellites than offered by GPS alone. The GLO 2 can pair up via Bluetooth with up to four devices, its battery lasts up to 12 hours, and it can be recharged with either a UPS cable or a cigarette lighter adaptor. It also comes with a free six-month subscription to the Garmin Pilot app. About C$190.

Learn more at, and available from, pilotmall.com

Aconsortium of European countries has agreed to become the launch customer for De Havilland Canada’s DHC-515 Firefighter program. Contracts have been signed with Greece, Portugal and Croatia for 11 DHC515s. A further 11 aircraft are expected to be added to the initial purchase. The amphibious aircraft are currently under production at De Havilland facilities in Canada.

The DHC 515 builds on the success of the CL-415, using new materials and better corrosion protection. A state-of-the-art avionics suite is also included.

As for performance, the aircraft boasts a 12-second scoop time and exceptional takeoff and landing performance. It is also the only aircraft in its category to be certified to operate in wave heights of 2 metres (6.6 feet).

Water tank capacity is 6,137 litres or 1,621 U.S. gallons and foam tank capacity is 680 litres or 180 U.S. gallons.

Specifications

Maximum Cruise Speed: 187 Kts

Normal Cruise Speed: 180 Kts

Long Range Cruise Speed: 140 Kts

Stall Speed (MLW Landing Configuration): 68 Kts

Average Fuel Consumption (Long Range Cruise Speed): 1,316 pph

Ferry Range with Maximum Fuel: 1,260 nm

Takeoff Distance (ISA, S.L., Land, MTOW): 2,570 ft

Takeoff Distance (ISA, S.L., Water, MTOW): 2,670 ft

Landing Distance (ISA, S.L., Land, MLW): 2,210 ft

Landing Distance (ISA, S.L., Water, MLW): 2,180 ft

Vancouver’s Harbour Air brought two eBeavers to the Experimental Aircraft Association’s AirVenture 2024 in July, one to their booth at the Oshkosh airport and the other to the nearby seaplane base on Lake Winnebago. Both had been disassembled in Vancouver and trucked to the Wisconsin venue for reassembly and display.

The FAA did not allow the eBeaver to take flight, however high-speed taxiing was permitted. With Harbour Air’s vicepresident of maintenance Shawn Braiden at the controls, spectators were treated to a show of the eBeaver’s performance on the water.

The aircraft are equipped with MagniX electric motors, more powerful than the one used for the eBeaver’s inaugural flight in Richmond, British Columbia in December 2019. Back then it used 500-kilowatt magni500 motor derated to 338 kilowatts, while the current versions have magni650 motors, again derated to more closely match the original Beaver’s Wasp radial engine’s performance. The electric motors are water cooled. Everett, Washington-based MagniX aims to have

“This

agreement signifies a major milestone in our journey towards sustainable aviation and demonstrates the growing demand for eco-friendly alternatives in the market.”

its motors certified by 2027, with STCs to follow.

In May, Harbour Air announced the signing of a Letter of Intent with Quebec’s Bel-Air Laurentian Aviation for the conversion of three standard Beavers to eBeavers. Bel-Air offers aerial sight-seeing tours in Eastern Canada and expects to carry four to six passengers on 60- to 75-minute flights.

“We are excited to partner with Bel-Air Aviation to bring the eBeaver into their fleet,” said Erika Holtzir, Harbour Air’s lead engineer on the eBeaver project in a press release. “This agreement signifies a major milestone

in our journey towards sustainable aviation and demonstrates the growing demand for eco-friendly alternatives in the market.” The two companies also announced their intention to collaborate on the certification of a wheel-ski option for the eBeaver.

Contacted by Canadian Aviator after the Oshkosh show, Braiden said, “It was an honour and a privilege to be part of one of the world’s largest aviation celebrations. The support and enthusiasm that we received from everyone at the show was nothing short of amazing.” Braiden then added, “We can’t wait to go back next year.”

Canada’s West Coast city played host to the annual international conference of the Ninety-Nines, also known as the International Organization of Woman Pilots, from July 4 to 7, attracting over 280 delegates from seven countries, with most coming from the United States, where the organization was founded and continues to host its headquarters.

Established in 1929 by 99 female pilots, members of the Ninety-Nines are represented in all areas of aviation. Its first president was famous aviatrix Amelia Earhart, who said she engaged in the pastime “For the fun of it!”

The conference was last held in Canada in 2016 (Ottawa), and this year’s event attracted several high-profile female Canadian leaders in the aviation industry as keynote speakers, including Elevate Aviation’s Kendra Kincaid, MajorGeneral Jamie Speiser-Blanchet, Deputy Commander of the Royal Canadian Air Force and Kathy Fox, outgoing chairwoman of the Transportation Safety Board.

Leading the international Ninety-Nines this past year was Robin Hadfield, the first Canadian and non-U.S. resident to serve in that role. Host and a key organizer of the

Vancouver conference was Cindy Pang, the Ninety-Nines West Canada Section Governor.

Every year the Ninety-Nines presents various awards to honour members who have excelled in four different categories. This year, Cathy Press, CEO of Abbotsford’s Chinook Helicopters and current chairwoman of the British Columbia Aviation Council, was recognized with an Award of Merit. Her citation reads, in part, “As a true leader in the aviation industry, she has been recognized for her outstanding achievements. She was awarded the W.A. ‘Dub’ Blessing Flight Instructor of the Year Award during the HAI Heli Expo. She has won numerous awards, including the Bank of Montreal’s Innovation and Global Growth Award, the Enterprising Woman of the Year Award by Enterprise Magazine, and the Back and Bevington Air Safety Award for the most significant contribution to air safety in British Columbia. She was awarded the DCAM Flight Instructor Safety and, in 2021, awarded an Honorary Doctor of Technology at the University of the Fraser Valley for her longstanding commitment and contribution to the aviation industry.”

Back when I was operating what the locals referred to as the “oneman airline,” I received a phone call from a luxury charter yacht that was based nearby. The radio-telephone message requested that I pick up three passengers at Kelsey Bay, British Columbia and fly them to the yacht, which was anchored in a place called Lagoon Cove on East Cracroft Island. That was a significant charter for my little airline, so I happily proceeded to Kelsey Bay in the Cessna 185. Seaplanes landing at Kelsey do so in the Salmon River, where an ancient dock put there by BC Airlines back in the early 50s was still the only tie-up available. The river presents some challenges for seaplanes as it is subject to tidal effect at the mouth where one is required to land. There is just one spot on the river between bends suitable for landing and takeoff and there is a cable crossing marked with big orange balls that one must take into consideration on the approach and landing. Depending on the tide, the current can also be significant, but intrepid aviators never say never and my landing there that day was dramatic but uneventful as all landing are — at least in my mind.

There were no passengers waiting for me, so I sat in the plane to await their arrival and gave some musings to the history of Kelsey Bay, a logging community on Vancouver Island that was no longer logging and was now attempting a living from the provisions of a rest stop for motorists on the way up-island to Port McNeill and Port Hardy. I thought how typical this situation was all over the coast when vibrant communities were suddenly abandoned by the logging companies that had created them. Such were my musings when a rather old, beaten Chevy Master pulled into the clearing

and three very lovely ladies stepped out, gingerly taking steps down the path to the dock — gingerly being the best word to describe the threesome’s navigation of the grassy pathway and the tilted, slippery planks of the dock, each of them wearing elegant, spiked heels and tight-fitting dresses that did not permit much leg movement.

The rungs of the Cessna 185’s float struts would be a daunting means of boarding the plane, so I suggested to the ladies that they remove their shoes to mount the logger-boot friendly steps. I agreed to hold their high heels while they boarded. One of the ladies, of course, had to slip across the pilot seat into the co-pilot seat and this location was selected by the woman seemingly in charge of the trio, she being more elegantly attired and a few years older than the giggling pair now ensconced

in the back seat. This would be the first time I ever had a co-pilot who wore lace gloves, the kind that allow the fingers to protrude.

As I slipped the rope and slid into my seat, a strong fragrance of what I believed to be Chanel Number 5 hit me, but there was no time to confirm the essence permeating the cockpit as the demands of the takeoff occur immediately you leave the dock on the Salmon River. We were soon skimming the sandbars at the river mouth on course for East Cracroft Island.

It occurred to me during this flight that a trip up the B.C. coast in a floatplane would be an entirely new and unique experience for these ladies, so I thought to play the part of tour guide and pointed out over the nose the dock at Port Neville, where the dog that flew on the pontoon of the

single Otter had started his amazing flight. The ladies enjoyed that story and were dutifully amazed that the dog survived. They were also duly impressed and, I thought, rather sobered by my pointing out the location of what had once been a native village whose occupants had all been moved from their home to a more convenient location for the Department of Northern Affairs during what some describe as the reign of terror of this government department, back when the native potlatches were decreed illegal and the residential schools were a popular idea. The older lady beside me seemed to know more about that situation than I did while those in the back were still giggling.

We took the pass into Boughey Bay, and I pointed out what clearcutting looked like from the air and, as we passed Minstrel Island, I pointed out the old building with the fading word HOTEL on its roof. “Built in 1904,” I said, and they all nodded absently but found it interesting that the name of the island was chosen because the early residents used to put on a minstrel show for the steamships that plied the coast before seaplanes took over.

When we got to East Cracroft I nosed onto the swim grid of the big yacht and the ladies had to remove their high heels once more to get down onto the pontoon. I removed the pilot-side door to allow them to more easily pass as they walked forward under the prop in their silk-stocking feet to gain the swim grid where their three hosts awaited their arrival with somewhat sheepish ardour. I handed back their shoes and got an enthusiastic wave goodbye from them as I faded off behind the yacht and took off, climbing over East Cracroft toward my next stop. The older lady had given me her business card thinking I might run into some prospective clientele. I slipped it under the sun visor feeling something like a New York taxi driver.

Iused to be part of a team that, in the event of an accident, would deploy to the scene to assist. We were trained on how to discuss bad news with relatives and how to aid survivors in the aftermath. We sat for hours in a boardroom acting out scenarios and the best way to handle each one specifically. But in the aftermath of an accident, every situation is different. Every person and every emotion cannot be summed up on an index card with an explanation and therefore, despite all the best training, you’d never really know what you’re walking into.

I’m not a ‘people person.’ I can interpret the meaning of a wiring diagram, and I can be delicate with expensive components, and I can sit in front of a keyboard and find the right words. But there’s a reason I prefer working with machines: airplanes may weep, but they do not cry. I always assumed this would cause me a disadvantage that, in the event of an emergency, I may distance myself from the emotion involved.

And then an accident happened, and I realized distance is exactly what’s needed. It’s horrifying, sitting in a room eerily silent waiting for an update, staring at the flight tracker, at the spot where the aircraft has gone off radar, and hoping it reappears. But I had a job to do, I had to put aside the fact I knew the pilot and I knew his family. So I laced up my boots and went to work.

For those of us who didn’t report to the scene, one of the first things we did was secure the rest of our fleet to ensure the same thing wouldn’t happen again. Every piece of the aircraft involved is meticulously examined and documented. The qualifications of every person who has worked on or flown the plane are verified. The maintenance team works in reverse, mulling over every detail to ensure nothing was missed. The failure was isolated to the one

aircraft and the investigation concluded nobody was to blame. Our pilot’s incredible expertise allowed him to execute a manoeuvre most pilots don’t even think of attempting, and he walked away from something that could’ve ended in devastation. Although the aircraft was written off, nobody else was injured and, at the end of the day, that was all that mattered.

Through my years in the industry, I have responded to low-speed ground collisions, diversions and emergency landings that were all unrelated to maintenance, but absolutely none of them can compare to the moment you learn your team has made a mistake. My only experience of this was when several cockpit circuit breakers were pulled for maintenance purposes, and one was missed getting pushed back in. The breaker went unnoticed by the flight crew until they were already airborne and experienced a system failure. The situation was easily rectified, but it has weighed heavily on me ever since.

Maintenance mishaps are typically caught immediately: a resistor is broken during installation, holes are drilled in the wrong location, an engine is overtorqued during ground-testing. These may ground the plane and cancel the flight, but it is always better than the alternative.

Accidents are difficult to talk about for everyone involved, and even for people who aren’t. It’s a touchy subject whether it’s human error or an act of God because it’s scary, but the conversations need to be had. I’ve played many roles in aviation — AME, quality assurance auditor, and pilot — and have seen a variety of mistakes and errors in each position.

The summer I got my pilot licence flying a Cessna 172 at a rural Alberta airport practicing touch-and-gos, my flaps became stuck in the 40° position and my aircraft was unable to climb.

In any aviation accident investigation, the paper trail is of paramount importance.

We made an immediate turn back for the runway, requesting special assistance from ATC, and landed safely. It was a scary and unexpected experience that I ultimately learned a lot from, as a pilot and an engineer.

Similarly, when I was an AME apprentice, I learned the importance of tool inventory when I accidentally left an inspection mirror propped in the gear well of an aircraft. I was able to retrieve the mirror before the aircraft left the hangar and I immediately secured a ‘Remove Before Flight’ tag to ensure it was never left behind again.

Some companies are weary of the negative publicity that is caused after an aircraft accident and therefore necessary conversations are avoided. Nobody ever wants to place blame, but doesn’t accepting responsibility go hand-in-hand with that? There are a lot of things we should absolutely be discussing, and we aren’t.

One of the first things I was taught in school was to never sign for something you aren’t 100 percent comfortable with. It seems like an obvious rule, but when

“Through my years in the industry, I have responded to low-speed ground collisions, diversions and emergency landings that were all unrelated to maintenance, but absolutely none of them can compare to the moment you learn your team has made a mistake.”

it comes down to it, it isn’t always black and white. Aviation has a lot of go/nogo limits, for pilots and for maintenance, and when conditions are right on the edge it can be more difficult to make an assertive decision. A senior AME can tell you it’s okay, and a pushy superior can say it’s good enough, and a competent pilot can confirm they’ll take the plane anyway, and all of those can lead to a signature you aren’t certain about. I will never forget the first time I refused to sign for work during a hangar inspection when the flap drive cable

was found to be right on the limit. But it wasn’t “out” and therefore I should’ve signed it. I argued with colleagues, and then my supervisor, because it may take just one flight for that cable to become out of limits, and we won’t be checking it again for another 50. It was a terrifying moment to put my foot down against a group of men with so much more experience than me, but management made the final call, and we replaced the cable. I’ve never hesitated to stand up for what I believe is right again.

My long-term career goal has always

been to assume a position where I have the ability to inflict positive change on the aviation community. Perhaps I’ll be a flight instructor so I can teach new pilots about mistakes I’ve made and help them avoid doing the same thing. Maybe I’ll move into maintenance management and be able to ensure everyone’s opinions and concerns are always heard. I’d like to work in accident investigation to find a silver lining in a dark matter. Not just to find out what went wrong, but to find what everyone did right, and why it wasn’t enough.

As pilot Roy Maxwell applied rudder and eased the Curtiss Seagull’s control column forward, he glanced at maintenance engineer J. P. Romeo Vachon and shook his head. The spinning aircraft continued down from 4,200 feet toward the close-packed Jackpine and spruce. Quebec’s timber terrain made ready to receive visitors on May 4, 1921.

Maxwell flattened above the needlelike tops before the left wing penetrated forest canopy near Lac-a-la-Tortue and slammed into sand-covered granite ground. The three occupants survived amid the collection of wood splinters and engine parts, and swallowed the gasoline splashed from the aircraft’s ruptured rear tank. The first Seagull to carry Canadian registration, G-CADL, arrived in Canada in September 1920 and three more of the elegant flying boats followed. All belonged to operators in “La Belle Province.”

Although records confirm only two actually flew, the mahogany-hulled Seagulls served as what the press of the day called “air patrol wagons”; they rocked aloft for timber reconnaissance and aerial photography along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River.

Mr. J.B.R. Verplanck’s

1,957-pounds empty, cruised 76 mph and landed as slow as 60 mph with pilot, AME and one “sketcher” when inventorying harvestable wood.

The original model flew in 1913 and improved higher powered versions operated in Canada and, as the December 29, 1919 Aerial Age Weekly said, to draw “real fortunes in the air.” Pilots accustomed to larger Curtiss HS2Ls faithfully believed the factory slogan that pilots “…know the confidence-inspiring Seagull always come home.”

“The first Seagull to carry Canadian registration, G-CADL, arrived in Canada in September 1920 and three more of the elegant flying boats followed.”

Powered by a six-cylinder 180-hp inline engine, short-range G-CADL penetrated inland to the St. Maurice Valley under the auspices of Laurentide Air Service. Later, aircraft hauled sport fishermen for Grey Rocks Air Service from SaintJovite, 66 miles northwest of Montreal. The same flying boat also served with Fairchild Aerial Surveys before being dismantled in 1926.

The Curtiss Seagull averaged

During their initial Canadian years, Seagulls functioned as learning platforms for aviators such as Roy W. Maxwell of Laurentide, who became Ontario’s Provincial Air Service director in 1924. After Romeo Vachon’s bruises faded, he attained renown in numerous fields and was awarded the McKee Trophy in 1937. At Lac-à-laTortue, Seagull pilot Hubert Martyn Pasmore became the first in Quebec to carry out year-round aerial photography and surveying, including during the province’s winter months.

Ottawa’s National Aviation Museum historians decided to acquire a Seagull to represent hulled aircraft types

dominating early wilderness flying. Director Kenneth M. Molson discovered a slightly modified Seagull in London, England’s Science Museum. Flown by Alexander H. Rice to map 500,000 square miles of Brazil’s Amazonian Basin between 1924 and 1925, he donated his ‘Eleanor lII’ after the selffunded project terminated.

The British showed little interest in the Seagull since none flew in England or other outposts of the mighty British Empire, except for Quebec’s bush country. Molson learned the museum would accept a Douglas DC-3 nose section in exchange and, consequently, the prize arrived at Rockcliffe on May 19, 1968. The Canada Aviation and Space Museum (CASM) restoration teams completed their artistry by March 1974. (National Aviation Museum namechange to CASM occurred in 2010.)

As CASM’s acquisitions increased, limited space forced management to conduct rigorous collection reviews and, regretfully, they decided to seek homes for several artifacts. A bulletin declared that the “…beautiful one hundred and three-year-old mahogany flying boat, which no longer fits within the scope of the national collection, would be deaccessioned.” The announcement drew interest from the Montreal Aviation Museum (MAM) in SainteAnne-de-Bellevue in the western suburbs of Montreal.

“Trenton’s National Air Force Museum of Canada’s purview was mostly military and the Atlantic Canada (Museum) in Halifax was too distant,” recalled MAM volunteer Eric Gregory. “We knew all four Seagulls in Canada spent their time in Quebec — perfect for us. Most of what we have was designed or built in this province.”

Fortunately, CASM had gone overboard and recrafted a Michelangelolike example of art. Spruce trusses and ash keels demanded hand-building, and corroded metal wing trailing edges needed refabrication. Esteemed for the glossy plywood mahogany hull, the original Eleanor III’s age-caused deterioration necessitated substitute sheeting but no correct lengths could be located. Consequently, spliced units went onto the structure with every screw hole plugged and tediously drilled. On June 25, 1920, a similar aircraft was marketed for $9,000 — equivalent to $134,405.66 in 2024.

After discussions with CASM, which relinquished the aircraft, a 15-person volunteer MAM team drove to Ottawa, dismantled the Seagull and returned to Montreal the same day. The aircraft promptly underwent reassembly for public viewing in an equally safe environment. Campbell added that CASM staff had done a “fantastic job — a work of art.”

During G-CADL’s brief productive

career, pilot Roy Maxwell’s catastrophic accident almost led to the banning of all Seagulls in Canada. A Court of Inquiry, including inexperienced non-flyers, declared him incompetent and attributed the loss of control to lack of skill. No one seemed to have been informed that Maxwell’s logbook showed 2,780 flying hours in three countries. During the inquiry, rigger J.F. Hyde pointed out that he considered certain Seagull metal fittings to be of low quality. Maxwell’s passenger William Bowden, also a pilot, came forward to testify he had noticed little or no effect on the controls during the near-fatal plunge.

“We ran into a bump which lifted my left wing. To clear this, I applied left rudder and left aileron gently and without warning, the machine lurched over rapidly to the left, falling into a spin,” Maxwell added. “I neutralized rudder and ailerons to correct spin but found nothing happened. I applied full engine to reverse speed but still, no results.”

One witness described G-CADL as “… absolutely smashed to bits.”

On August 5, 1921, a civil aviation controller stunned investigators by stating that, “… Canada’s Federal Air Board had never investigated [the] Seagull design.” Certain airplanes already certified with previous history received automatic licensing. Post-accident requests to the Curtiss

L to R: On April 13, 2010, a 1917 Curtiss MF Seagull sold at auction for U$506,000—far from $6,000 when new. The two-place version had a 100hp V-8 engine and a 49-foot, 9-3/8-inch wingspan; The Montreal Aviation Museum’s Seagull derived 160 hp from an air-cooled Curtiss C-6 engine. Montreal Aviation Museum members added that the hand crank starter can turn the powerplant; Figures claim that a Seagull fuel tank contained 70 U.S. gallons and carried seven U.S. gallons of oil. The copper fuel tank’s location does not appear to be logical in the event of a sudden stop.

Aeroplane and Motor Corporation of Garden City, Long Island, New York demanded more studies of spinning and low-speed characteristics.

“Investigations show that, in many cases, the machine is under strength requirements and further, an appropriate check of the stability confirms pilot’s report that the machine is unstable laterally at low speed,” a December 20, 1921, report concluded. “They do recommend that the type be prohibited for use as a commercial airplane in Canada.”

The Curtiss Corporation submitted reams of data to Ottawa’s Air Board. Although no diagrams of modifications can be found within CASM or MAM files, the Seagull received further authorization to continue in Canadian skies. The last, G-CARF, landed in Quebec on May 23, 1928, for Canadian Airways. Canadian Aviation Historical Society summaries indicate the aircraft did not enter service nor was the registration utilized.

To the relief of flying boat aficionados, an actual Curtiss Seagull stands ready for viewing at the celebrated SainteAnne-de-Bellevue’s Montreal Aviation Museum. Not far from the machine, manufacturers claimed had a 35-mph stalling speed, visitors can contrast the under-restoration Lockheed CF-104 Starfighter’s 1,528 mph cruise with the Seagull’s leisurely 95 mph.

In the world of finance, promises of returns to investors usually contain barely readable disclaimers that “past performance does not guarantee future results.” It’s that industry’s way of saying, “Don’t count on us being as good tomorrow as we were yesterday.” In reality, this is a very honest statement, mostly due to market variables and the state of the global economy being well outside the control of any of us.

In General Aviation (GA), many of us apparently know better, believing with certainty that we will be as good tomorrow as we were yesterday. All we need to do is take to the skies to prove it. To combat this, Designated Flight Test Examiners will often encourage successful candidates to always “continue learning,” which to my way of thinking is very solid advice.

Sadly, more often than not, just the opposite happens and, to some extent at least, we are all guilty of this failing. Once a new licence is granted or a rating earned, the idea of being a better pilot on each trip somehow fades away, replaced with a feeling that with no further effort, we will be as good tomorrow as we were yesterday.

Flight safety experts categorize this type of thinking as an example of “the strength of an idea,” in this case the belief that a positive outcome in the present or future is somehow assured owing to relative success in the past. In reality, what we as pilots did yesterday has little impact on our success tomorrow — unless, of course, we continue to apply the same safe practices that have proven so effective on past flights.

The renowned aviation writer Richard Collins was well known for his remarkable insights in all things GA. Collins took a contrarian point of view to the

thinking prevalent at the time that, where pilot skill was considered, hours in the logbook were everything. He instead suggested that the only flight that really matters is your next one. In his book, The Next Hour: The most important hour in your logbook, Collins implicitly saw experience as a measure of, but by no means an assurance of, flight safety going forward.

Lacking other accurate predictors of pilot competence and, by extension, risk, aviation insurance underwriters have understandably piled on to the idea that experience is an accurate predictor of how safe a pilot will be. But screw up just once, and suddenly they’re looking at your next hours with a new keenness, effectively assigning a premium to them as a sort of financial act of contrition on your part.

Airlines, whose very existence depends on their safety record, apparently demonstrate the same kind of skepticism as to their crews’ abilities going forward. Were it not the case, they would happily abandon the hundreds of millions

they spend each year on recurrent pilot training, relying instead on the idea that a crew’s record is dependable enough to forecast their future abilities. Put another way, if you could ask a once-happy turkey about a week before Thanksgiving how using the past to predict the future worked out for him … well, you get my point.

More seriously, Collin’s point of view takes on a whole new meaning when we reflect on how many ‘good pilots’ we’ve all known over the years who’ve become victims of fatal accidents. It’s easy to believe in the infallibility of the ‘good pilot’ theory until you attend your first memorial service in one’s honour. You might walk away, as I often have, trying to understand how it happened. As was written long ago, flying is not inherently dangerous, but is terribly unforgiving of incompetence or poor decisions. For those unfortunate souls, their next hour also proved to be their last.

How then do we counter this potentially lethal flaw in the human condition,

namely aviation-centric hubris? The answer is simple. Strive to be a better pilot, each and every flight. Here are four practical ideas that will help you move further up the flight safety continuum:

1. Checklists. Use them.

By their very design, checklists ensure that all critical items are covered off, virtually eliminating the threat of critical preflight procedural errors. I’ve imported one into my iPad mini, courtesy of Foreflight, modifying it to include pre-flight items such as ensuring my tow bar has been removed. If you think this concept doesn’t apply to you, then perhaps you know better how the old saying “Checklists are printed in blood” came to be.

2. Threat Assessment.

Before every takeoff and landing, I use a procedure stolen from Air Canada, and earnestly attempt to identify what threats I might face during this flight.

Do this for every takeoff and landing. For me this meant recently declining the IFR option in a Cessna 210 I was helping deliver, solely on the basis of my not being happy with the airplane’s avionics. The most basic threat assessment I conduct starts with me asking, “should I be flying today?” More than once this self-critique has resulted in my turning around at the airport gate and driving home, but not before grabbing a ‘Tim’s double-double’ as a reward for being so clever.

3. Fly a Stable Approach.

A common element in many landing incidents and accidents is that they were preceded by unstable approaches. The mistaken belief that we, as pilots, can somehow pull off a miracle in the flare, or during the roll-out, isn’t supported by statistics. Whatever your type of aircraft, establish what you consider to be acceptable deviations from the ideal in terms of tracking, glide path and

airspeed control, and then hold yourself accountable to your own rules. This type of flight discipline is the hallmark of a true professional.

4. Learn on Every Flight.

A retired Air Canada captain I greatly admire, Colin Bechtel, has an approach applicable to all types of aviation I hope to one day fully emulate. It’s one I encourage you to copy as well. Colin speaks of reflecting on those things that you did well during a flight, and those items you’d do over if given the chance. Do this every flight and you can’t help but become a better aviator.

In the end, these practices have one goal: making you a better and therefore safer pilot. Time in a logbook tells your story in aviation, and in many cases can be a relatively accurate predictor of future performance. But always remember, the only hour that really matters is the next one. The rest is up to you.

CANADIAN AVIATION CONFERENCE AND TRADESHOW 2024

A major Industry Networking Event not to be missed!

ATAC’s Canadian Aviation Conference and Tradeshow is the premier national gathering offering Canada’s best networking, learning, and sales opportunity for operators, suppliers, and government stakeholders involved in commercial aviation and flight training in Canada.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 5 TO THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 7 WESTIN BAYSHORE HOTEL, VANCOUVER, BC

For more information contact: tradeshow@atac.ca www.atac.ca

LIVING THE DREAM WITH CHRIS WEICHT

Ihad been flying with Futura Aviation at Vancouver since October 6, 1975, and worked my way up from nightly return bag runs in Aero Commander 680s to Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta, to more sophisticated turboprop 690Bs and Swearingen Merlins, flying charter flights.

Then, in February 1977, I was on holiday at Maui, Hawaii lying on the beach when someone yelled, “Is there a Chris Weicht here?” I responded and a man answered saying that there was a phone call for me on a pay phone in the lobby. “What the hell,” I thought. I didn’t know anyone here but on answering it was Mark Brady, my boss at Futura Aviation in Vancouver, wanting me to come

back right away to start training on the Jet Commander 1121, CF-FBC, that they just acquired to operate for charter and mostly on a contract with entrepreneur Peter Pocklington of Edmonton. I likely stuttered out a reply something like, “I would love to start flying the corporate jet but my family of four have just arrived here in Maui.” Brady understood and said they would be couriering the aircraft’s training manuals to me and that I should be prepared to write the exam and start flight training as soon as I got back. Well, studying was not exactly what I had in mind for the holiday but for me this was the chance to do exactly what I had been working toward since I started flying.

On returning home I finished my training on FBC and later passed the Transport Canada flight test as co-pilot and later co-captain. Then I began operational flying with the aircraft.

On one flight for “Peter Puck” to Los Vegas, Nevada, Pocklington told us on arrival, “Go have yourselves a good time, boys, we will be here for several days.” Well, we took Pocklington at his word and went out on the town and got somewhat inebriated, and staggered into bed likely about 1:00 am. At 3:30 am the phone rang, and it was Pocklington who announced he wanted to go to Cozumel, Mexico, right away. We told him that we could not arrange the international flight until about 10:30 am,

which was partially true.

We were able to get the flight plans filed, weather checked, and customs arranged for Cozumel, and had the appropriate commissary on board for an 11:00 am departure. On our arrival over the Mexican city, the area was covered in a layer of marine fog, which necessitated our making a non-precision VOR instrument approach to the airport.

We had descended to 2,000 feet as published in our Jeppesen chart and had been cleared for the approach for the airport. We were outbound from the VOR on the 237-degree radial, descending to 1,500 feet and preparing to make a procedure turn to our left. We had been assured by our Mexican controller that we were alone in the area, so we were astonished when suddenly a Douglas DC-4, a four-engine aircraft, appeared really close on our left side, right where we would have been if we had started our procedure turn seconds earlier. We were screaming at the Mexican Centre controllers about the old airliner, but they came back with, “Señor, there no other aircraft there.”

Obviously, the DC-4 wasn’t talking to anyone and was flying well below where he could be seen on radar. Well, I guess we all have a pretty good idea of what he was carrying. Once we got our heads squared away, we turned inbound and landed on Runway 05. Then, we all checked into the Cozumel Caribe, an upscale hotel, where we stayed for a few days enjoying the sun and first-class meals.

Pocklington advised us that he wanted to go to Havana, Cuba next. However, we were denied landing rights by the communist military authorities, even though we had previously been told there would be no trouble. Pocklington then decided that we would instead proceed to Kingston, Jamaica where we landed and spent the night.

When after dinner we pilots went for a walk near the Holiday Inn, we were met by a mob of angry black men who came up the street yelling obscenities and started throwing empty bottles at us. So we decided to retrace our steps to the hotel. Jamaica is not my favou-

rite place in the Caribbean, and I have never returned.

The following day, Pocklington requested us to flight-plan to Port-auPrince, Haiti where he and other business entrepreneurs had been invited to the Palace of Dictator Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier. I was not privy to the purpose of this meeting, but on landing we were met by an entourage of Mercedes Benz limousines, complete with their Tonton Macoute (Haitian secret police) drivers, who were all armed with Israeli Uzi machine pistols.

As we taxied the Jet Commander to the Port-au-Prince airport terminal building, we passed a North American B-25 Mitchell bomber with Royal Canadian Air Force in bold lettering down the side of the aircraft. All visible parts of the aircraft were riddled with machine-gun holes. As I have no knowledge of Canada going to war with Haiti, I can only surmise that the aircraft was acquired from Canada’s Crown Assets in the post-war period and had been used to attack the dictator. What happened to the B-25’s crew was unknown.

After we arranged for a guard for our aircraft, the limo assigned to the Jet Commander crew took us at high speed through slums of Port-au Prince, with little regard for its inhabitants, to our accommodation — a villa complete with iron gates and a 20-foot-high stone wall set on the top of a small hill near the city. We were the only occupants of the villa save for a compliment of servants and cooks. There were two swimming pools, one of which had an underwater grotto with a black barman ready to serve us any drink we might desire. We were also able to request almost anything we desired from the cook. I thought that this was certainly the way corporate pilots should be looked after by their employers.

On the last night of our stay, Baby Doc ordered a command performance of voodoo for his guests at the palace, which was to include the pilots. I was not keen on attending, but one does not refuse Haitian dictators’ demands without repercussions.

Pocklington and his party were seated with the dictator and his hangers-on, which included his wives, concubines and their security guards.

The show consisted of several naked teenaged girls who were lined up doing some sort of primitive dance, while a man who I assume was a witch doctor, went to each girl in turn, took a swig of some substance out of a decanter and then blew the contents into each girl’s face. As soon as he did this, the girls started trembling uncontrollably and their eyes were rolling. One girl fell into the fire that was in front of the performance. No one seemed interested and just left her there. However, she seemed to be unhurt by the event.

After a series of sexually explicit acts the show ended and a feast of sorts followed, after which we went to our villa. I have no idea what the Pocklington group did. The next morning, we prepared for a flight to Nassau in the Bahamas and, on departure, Pocklington asked if we could fly low over the old castle of Cap-Haïtien on the other side of the island, where a group with whom they were with at the palace had gone earlier in the day. Pocklington seemed quite eager that we buzz the castle, so why not? We came down quite low I am sure, making a hell of a racket.

Our flight continued to Nassau and then to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. While waiting at the hotel for Pocklington to complete his business, I was sitting on the lawn behind the hotel enjoying the sunshine and reading a magazine when my attention was caught by a movement in front of me. I glanced up and here was a large crocodile that had climbed out of the canal and was looking for lunch — me? Needless to say, I grabbed my magazine and beat a hasty retreat for the safety of the hotel.

In retrospect, I recalled that I had escaped being rammed by a clandestine airliner in Cozumel, Mexico, avoided an angry mob at Kingston, Jamaica, survived the vicious Tonton Macoute as well as Baby Doc’s Voodoo rites, and now I was almost devoured by some hungry croc in civilized Florida.

In the previous article, unaided GPS or raw GPS approaches were reviewed. This included the LNAV approach, with and without a calculated glideslope, and an approach style using GPS for lateral navigation and barometric altimetry for vertical navigation (LNAV/ VNAV). This article examines augmented GPS and how it provides a capability identical, and arguably superior to the venerable Instrument Landing System (ILS).

Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) improves all the necessary qualities of navigation (accuracy, integrity, availability and continuity) to be an ILS replacement. When it was first conceived 20 years ago, the hope was to provide a non-precision capability (250-foot approach limits). Over time, with improvements and increasing confidence in it, WAAS has evolved to provide a precision approach capability with approach limits identical to the ILS (200 feet).

The ILS infrastructure has built-in capabilities to monitor its performance continually; the WAAS monitoring stations throughout North America perform the same role in monitoring the health of the underlying GPS satellite network. In addition, a WAAS receiver has a similar capability located on board the aircraft, not on the ground. A WAAS receiver continually monitors its lateral and vertical position; if it goes outside certain bounds, an alert is provided to the pilot and an instrument approach using WAAS is not possible.

An ILS has a fixed position of the localizer and glideslope antennae and the aircraft position with respect to the localizer and glidepath is

determined by the radio signals from these transmitters. WAAS approaches, however, are entirely mathematical creations starting with the runway threshold position then mathematically computing positions of the localizer and glideslope. This allows for varying the lateral and vertical approach angles, providing flexibility to an approach designer to accommodate local terrain and obstacles.

And with all these values emanating from an avionics database, the integrity of the database is crucial. When WAAS approaches are created, a Cyclical Redundancy Check (CRC) is used to verify that the numerical values used by the avionics are identical to the numerical values used in the procedure design. When this approach is selected by the pilot, the CRC check is performed to ensure that the mathematical description of the procedures is correctly unpacked by the avionics. A pilot gets a small insight to this with the WAAS channel found on the approach plate and when drawing the procedure from the database when loading the approach into the receiver. This is the WAAS channel shown on the approach plate. Flying a WAAS approach is almost identical to flying an ILS. Like an ILS, where one confirms that a valid ILS signal is being received (no flags, identification of the frequency, etc.), in the case of a WAAS/LPV approach the pilot must ensure that LPV annunciation appears on the navigation display meaning that all the navigation requirements of the receiver are satisfied.

as scalloping of the glideslope, vehicle or aircraft interference of the localizer, or other issues. The ride on an LPV approach is perfectly smooth and uniform.

“Since the WAAS signal is space-based, it is not subject to the challenges of the groundbased navigation such as scalloping of the glideslope, vehicle or aircraft interference of the localizer, or other issues.”

Older ILS installations provided a back-course approach to the opposite end of the runway; modern ILS installations no longer offer this. And like the localizer-only approach of yesteryear, WAAS does offer a similar approach known as LP (Lateral Procedure Only). This type of approach is used in unique situations where a vertically guided LPV is not possible. This could be when the final approach course exceeds a three-degree offset from the runway axis, the vertical path is too steep or other rare situations, typically found in the mountains. In this case, the approach is a more accurate two-dimensional approach and is flown identically to the LNAV approach described earlier.

A common question is why are some WAAS/LPV approaches to 250-foot approach limits and others to 200foot limits? In general, this is due to the runway classification — a nonprecision runway allows approaches to as low as 250 feet while a precision runway (often associated with an ILS to the same runway) allows for 200foot minimums. The obstacle clearance, protected area and approach lighting requirements of the precision runway are more rigorous than the nonprecision runway; for most community airports the incremental cost to achieve a precision runway standard is not worth the incremental 50-foot gain in approach limits.

Since the WAAS signal is spacebased, it is not subject to the challenges of the ground-based navigation such

In the next article we will discuss the Required Navigation Performance (RNP) style of instrument approach.

AN ICELANDIC SAGA

AEROBATICS WITH LUKE PENNER

Picture this: you’re circling high above Reykjavik in a holding pattern, waiting for clearance to perform your airshow routine, and below you, a volcano is erupting. On a remote island where nature’s fickleness and the cost of geographical isolation seem to defy the logic of aviation, here’s the story of how I’ve been drawn back to fly in Iceland every year for the past decade.

During the summer of 2012, I set my sights on flying to the United Kingdom to witness the London Olympics firsthand. While scouring for airline tickets online, an intriguing advertisement caught my eye: a stopover in Iceland. My knowledge of Iceland was limited to its nickname, the “land of fire and ice,” its remote location in the North Atlantic, and its reputation for stunning, rugged nature and friendly locals.

That initial trip was transformative. Road-tripping around volcanic beaches, active volcanoes, geysers and fjords, I fell in love with the landscapes, the endless summer daylight and the warm, humorous culture of the 300,000

inhabitants. Since then, I have returned to Iceland 10 more times. This article recounts my latest adventure there during the spring of 2024, exploring new facets of this incredible country.

So why do I keep returning to Iceland? My passion for this unique Nordic country only grew when I managed to combine it with my love for aviation. This fusion happened in the winter of 2017 when I came across a post on a Pitts pilots’ Facebook page. The post mentioned a group of pilots in Reykjavik who had recently imported a Pitts S-2E (the experimental version of the S-2A) and were seeking an instructor to train them in aerobatics and emergency manoeuvring.

With my deep affection for Iceland and extensive experience flying (and instructing) on Pitts aircraft, I felt destined to join this group. I spent time writing a compelling letter explaining why I was the ideal candidate. When I received the thumbs up from the group, known as Flugsveitin (which means The Air Force in Icelandic), I could not have imagined how my life would change. Over the years, this group of Nordic

“Over the years, this group of Nordic aviators has welcomed me as one of their own, profoundly enriching my connection to Iceland.”

aviators has welcomed me as one of their own, profoundly enriching my connection to Iceland.

We all know that general aviation is not an inexpensive hobby, but in Iceland the costs can be double or even triple the norm. For example, a litre of avgas currently costs around C$4.60 and obtaining a private pilot licence is quite costly. To lower these barriers, pilots in Iceland often form large clubs where members pay an initial buy-in fee, a monthly fee and then a reasonable rental rate for an airplane.

I primarily instruct on two aircraft: a Pitts, with 16 club members, and a Yak-52, with over 30 members. Since 2017, my focus has been on providing Pitts-specific tailwheel training, upset

prevention and recovery training, and aerobatic training to a dynamically changing roster of club members on TFACE, a yellow Pitts S-2E imported from the U.S.A.

A high percentage of these club members are airline pilots working for Icelandair, or the new low-cost carrier, Play. This connection allows me the luxury of being “picked up” in Toronto and given VIP treatment on the way to Iceland. On my most recent trip in June, I flew from Hamilton, Ontario to Keflavik (BIKF) on Play Airlines. The captain and first officer, both good friends of mine, ensured I had a wonderful experience on the A320neo. Landing in Iceland at 03:30 with the sun already up, I was ready for a nap and the adventures of the next 10 days.

Over the years I relied on a temporary validation of my Canadian

ATPL for solo flying in Iceland. After reaching the maximum number of validations last year, my main objective this year was to complete a full EASA PPL conversion. This was also necessary for my continued local airshow participation. The process involved obtaining a medical certificate, passing theory exams, an English test, and a practical flight test. The flight school Geirfugl at Reykjavik’s downtown airport, along with my instructors Valdimar Bergsson and Gunnar Láruson, provided invaluable support during this process.

With my fresh EASA licence endorsed with an aerobatics rating, I was able to (once again) perform in the Reykjavik Airshow, a major highlight of my year. Circling high above the airport in the holding pattern, waiting

for Reykjavik tower to clear me into the display box, I could not help but take in the 360º view around me. I could easily see an active volcanic eruption that had started on the Reykjanes Peninsula the same day I arrived in the country. Volcanic eruptions and earthquakes are commonplace in Iceland, but seeing an eruption from the air never gets old.

Once the tower cleared me for my performance, I had a wonderful time displaying the capabilities of the nimble four-cylinder Pitts. My routine included flat spins, tumbles, double

“It takes a remarkable level of dedication and passion to commit to aircraft ownership, especially a purposebuilt aerobatic plane, in a place where it does not make much practical or financial sense.”

hammerheads and inverted passes down the runway.

I feel extremely honoured that the Icelandic flying community has welcomed me with open arms all these years, and I am dedicated to uplifting that community by enhancing aviation safety through aerobatic and upset training.

In all my trips to Iceland, I believe this most recent one had the worst flying weather. Low ceilings, high winds, rain and severe turbulence off the mountains were constant barriers to regular flying. Despite this, I stayed in a state of constant readiness to allow for a couple dozen training flights between the Pitts and the Yak-52.

The main objective this year was to get already qualified pilots re-current so that they would feel comfortable flying solo and taking passengers. Re-exploring the various spin modes of the Pitts was an excellent way to shake off the winter rust and become reacquainted with its idiosyncrasies. Since Reykjavik airport is closed to circuit work on weekends, we relocated

to the nearby town of Selfoss, which has two wide grass strips and is one of the few places where a pilot can obtain 100LL fuel.

Earlier I mentioned the captain who flew me to Iceland. Several days later I had the privilege of re-clearing him for solo flight in the Pitts. As I watched him take off alone in an airplane that demands full attention during every phase of flight, I was filled with immense pride.

It takes a remarkable level of dedication and passion to commit to aircraft ownership, especially a purpose-built aerobatic plane, in a place where it does not make much practical or financial sense. Despite all the barriers, I have witnessed incredible growth within this fine group of pilots in one of the most challenging places in the world to own and fly a Pitts.

Many years from now, when I look back on my flying career, my involvement with aviation in Iceland will be among the things I am most proud of.

Takk fyrir, and until next year.

THIS WAY OR THAT WAY?

Altitude is a vast subject. Whether IFR or VFR, there is a lot to talk about on the issue. Everything from efficient cruising to local operations, and what’s appropriate and where.

In the enroute air traffic control world, controllers have direction regarding issuance of clearances for altitudes. At the basic level, when a clearance is issued to an aircraft, among the first things considered is whether a pilot’s requested altitude is appropriate for direction of flight.

I suspect most pilots are aware of what that phrase means. The cruising altitude for IFR should be odd thousands if the aircraft’s track is eastbound (between north, or 360° and 179° inclusive) and even thousands if the aircraft’s track is westbound (from 180° to 359° inclusive).

For VFR flight above 3,000 AGL, the altitudes are the same as above, except 500 feet is added to provide a buffer between IFR and VFR aircraft.

Of course, the whole point is to try to separate opposite direction traffic where the closure rate compromises a pilot’s time to “see and be seen”, much like lanes on a two-way street.

It’s worth noting that it’s not a perfect system. One aircraft flying southwestward would be flying appropriately at 6,500 and it would also be appropriate for direction of flight for a northwest-bound aircraft to be at 6,500. Taking it to the extreme, an aircraft flying 359° and another flying at 180° would be almost exactly opposite direction but be at the same altitude because of the rule.

It does, however, work pretty well in practice, when observed — until life finds its way into things.

As a controller, I’ve seen many occasions where a pilot simply forgot and selected an altitude inappropriate

for direction of flight.

As a pilot, I’ve done it myself.

Since it’s based on track in cruise flight, it’s easy to see 355° on the heading and say, “I should be at 4,500,” when the track is actually 005° and the aircraft should be at 5,500.

established and published at both, not every pilot is aware of them. A training area with a ceiling of 6,000 feet may see an aircraft cruising through at 5,500.

Weather also comes into play. One day, I accepted two westbound VFR flights, one planned at 8,500, the other planned at 6,500. The first encountered cloud he estimated was at 7,500 and asked me if he could fly at 7,000 instead. The second encountered cloud estimated at 6,000 and asked if he could cruise at 5,500.

The airspace was Class E, so as a controller I had no authority over either of these aircraft. I can neither assign them an altitude nor can I direct them to fly at other altitudes. The most I could do is remind them of the rules.

Consider these two altitude choices for a moment.

Both are inappropriate under the law. In one case, the VFR wanting to fly at 7,000, was at least talking to ATC who should be aware of any IFR traffic that may be operating at the eastbound IFR cruising altitude.

The second stated he wanted to operate at 5,500, which is an appropriate altitude for an aircraft flying in the opposite direction under VFR. Remembering that ATC cannot see an aircraft without a transponder in large portions of airspace across Canada, it increases the risks, even if the pilot is with ATC for flight following.

Beyond cruising, altitude selection has other implications. Two of the airports in my region are high-volume training airports. While training areas are

While that pilot should, during flight planning or cruise flight, be reviewing data about charted airspace to see what lies ahead, unexpected weather can still come into play. For example, clouds may force that aircraft down from the planned 7,500 feet to 5,500 feet.

Around airports, especially with high volume training, altitude selection can be critical. Where instrument approach procedures exist, IFR aircraft generally want to fly an instrument approach procedure, even under visual conditions, which includes prescribed paths and altitudes.

IFR aircraft must adhere to clearances and procedures to ensure separation from other IFR flights. While IFR establishes no priority or right of way over VFR aircraft, VFR pilots should consider this aspect since they have more flexibility regarding their flight paths. It’s a good practice to remain clear of approach paths for safety’s sake, or to at least be extra vigilant for IFR traffic, which could be faster and in a heavier wake turbulence category.

There is, of course, much more to the topic of altitude selection, but this is just touching on the subject, and only from an air traffic controller’s point of view. The subject of IFR vs VFR is a very important issue across the country, and the more we, as pilots, can do to keep ourselves and each other safe, the better.

Mesmerizing is the best word I can find to describe the videos that emerged shortly after a Harbour Air de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver collided with a small pleasure boat in Vancouver’s busy Coal Harbour on a spectacularly clear-weather day in early June. From the video vantage point, the two craft were obviously on a collision path. How could both captains go straight at each other full throttle without making any attempt to avoid the collision?

A video shot by French tourists in Stanley Park appears to show the boat stop seconds before impact. Could it be that the racket of the Beaver’s labouring radial engine finally caught the attention of the boat driver? The seaplane also appears to pull back hard right just before the crash. Did a right-side passenger scream “boat!” at the last minute? Regardless, it was clear that neither saw the other until it was too late.

While the question of rules and priority privileges is worth reviewing, let us not forget that “see” comes before “avoid” in the “see and avoid” concept. Physiologically, our peripheral vision can detect danger as long as it moves. The problem is that an object moving towards us on a collision course appears motionless, in space and size, until it blossoms into its full size when it is too late. This effect explains why the pilot of the Piper Cherokee that collided with Aeromexico’s DC-9 over Los Angeles back in 1986 died from a heart attack, not the collision.

Basically, the straighter the conflicting paths, the less likely we are to visually detect the collision danger. During takeoffs and landings, straight is good. This, our low operating speeds and high workload make us particularly vulnerable to collision hazards during these flight phases. That is why we have priority over other craft except for another craft facing an emergency at that stage.

Seeing also requires that nothing stands

in the way. On that day, the harbour was bustling with a wide range of watercraft drivers trying to take advantage of a rare warm sunny weekend day in the area. The Beaver did receive an advisory from ATC about a boat in the vicinity as it initiated the takeoff sequence. It is not hard to imagine that the boat was obscured by other boats when the pilot scanned for the traffic before launching off. Then, as we all know, spotting anything located lower on the right side from a left seat is already a challenge in level flight. It becomes virtually impossible with a nose-high attitude. That is why banking right and left and lowering the nose momentarily to visually clear the area during climbs is a smart habit. Incidentally, doing so also makes it easier for others to detect our presence with their peripheral vision.

Once seeing is possible, avoiding is next. The first applicable rule is based on manoeuvrability. The most manoeuvrable craft gives way, regardless of relative location. It is common sense. The vehicle that can remove itself from the collision path more easily and promptly should do just that. For example, helicopters are more manoeuvrable than airplanes and thus should give way. Likewise, light aircraft are more manoeuvrable than airliners and should give way. In general, things with an engine are more manoeuvrable than things without one. So, powered airplanes must give way to gliders and balloons, again, regardless of relative positions. Most of it makes sense and so does the rule that gives priority to an aircraft in distress over anything else.

Right after the collision, the boat turned 90 degrees “on a dime” to assist the seaplane passengers. An airplane cannot do that unless you push down on the tail. That is not recommended on the ground as the tail is not designed to take repeated downward loads and is not possible in flight. In this case, the more

manoeuvrable vehicle was the small boat. Moreover, there is a five-knot speed limit for boats travelling across the Coal Harbour aircraft operation zone marked with flashing lights on the north side and a buoy at the southwest boundary, and boaters are asked to be prepared to move out of the way on short notice.

When two craft are in the same manoeuvrability category, the right-ofway rules come into play most of the time. Basically, the craft on the right has priority. Look for the red light at night. To give way to the priority aircraft, the other aircraft must deviate to the right, in other words, pass behind. Common sense again. Keep that in mind when choosing a path to get out of harm’s way. The natural tendency of ship captains is to offset to the right when they see something, whether they have priority or not.

Right-of-way rules do not apply everywhere. Take for example an aircraft trying to enter a left-hand circuit. The joining aircraft may not use the right-of-way rule to cut off an aircraft already established on the downwind leg. In that case, the aircraft entering the circuit must give way to the aircraft on its left already in the circuit.

Advances in technology have greatly improved engine reliability, fuel management and navigation. When it comes to collision avoidance, the assistance is still limited and most effective in highly controlled flight environments. When operating in uncontrolled space, especially in high-density, mixed-craft zones, technology can become more of a distraction than a help.

Today, the old-fashioned head-on-pivot, eyes-out technique remains the most reliable method, even with its built-in flaws. Look out and use common sense. As one of my aviation mentors told me, “Dead men cannot argue.” Don’t expect everyone to respect the rules, willingly or unwillingly. Stay alert, look and avoid.

The atmosphere in which pilots conduct their flying activities is constantly on the move. Its state of flux introduces a conveyor belt of variables, each of many morphing at any time into myriad more. Pilots perform in this environment and must cope with its eccentricities to safely fulfill the purposes of their aerial venture.

The atmosphere is aviation’s playing field. The weather is its turf, the conditions from which make a flight either benign and of no consequence, or brooding and hostile, and disobliging of an aircraft’s presence. Weather affects everything that is important to aviators: planning, routing, timing, and safety. Understanding the relationship between weather and flying is, therefore, critically important to pilots.

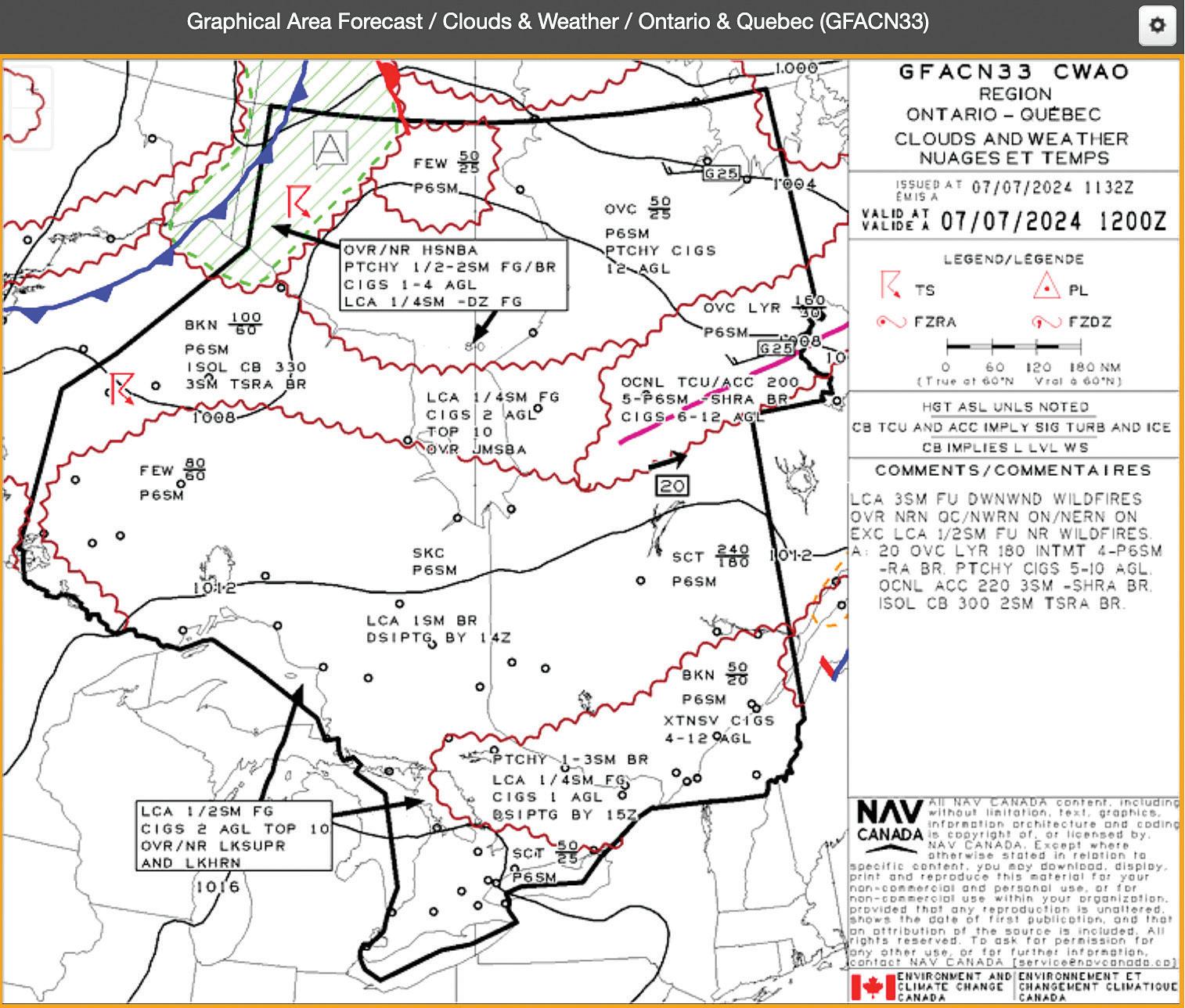

In the spring of 2024, the weather applications team at Nav Canada launched a website to help professionals in the aviation sector to better understand weather phenomena and how they impact the industry. The site is called the Aviation Meteorology Reference. Its content is the result of input from experts across the aviation spectrum, including pilots, flight instructors, commercial carriers, air traffic service providers, airport authorities and, of course, meteorologists.

The website’s structure is aligned with a full breadth of meteorological terms that are pre-eminent in the lexicon of weather reporting. It’s set up with every letter of the alphabet present as a ‘hot button.’ Click on a given letter and a subset of terms appears, starting with that letter. For example, a click on the letter ‘S’ results in the terms ‘Synoptic Scale,’ ‘Snow Squall,’ ‘Snow,’ ‘Squall Line,’ ‘SIGMET’ and ‘Shortwave Trough’ all appearing. These terms all

have their own links to separate pages bestowed with details that describe the nature of each.

The explanations of the terms teach the science behind their presence as weather phenomena. They also tie the terms to real-world forecasts and weather observations to better enhance user learning. In so doing, the Aviation Meteorology Reference connects meteorological information with how it should be used operationally by every relevant stakeholder in the aviation community.

A further example is under the letter ‘A’, where the term ‘Atmospheric Instability’ appears. Click on this term and the page opens up with two tabs from which you can then choose your path for further information. A ‘Meteorology’ tab provides the

definition of the phenomenon (in this case, ‘Atmospheric Instability’), and an ‘Aviation’ tab describes how that phenomenon is relevant to service providers as well as to users of the aviation system.

From within the ‘Meteorology’ tab, users are provided with the METAR code as well as the weather symbol (both if applicable) for the weather phenomenon being probed. Thereafter, hazards associated to the weather phenomenon are listed. (For instance, under ‘Atmospheric Instability,’ clouds and precipitation, thunderstorm development, and turbulence are identified as hazards.) Further down the page, an ‘About’ section defines the weather term and lists associated phenomena all of which are hyperlinked to their

own respective windows. A section entitled ‘Visualization’ cuts into the belly of every listed phenomenon: their science is explained (using text, charts, and graphics), how they appear in forecasts is shown (using recent archived data including GFA and TAF), and how they are identified in observations (via satellite imagery, Radar, SIGMET/AIRMET, and METARs) are thoroughly demonstrated.

Shifting to the ‘Aviation’ tab, ‘Main Concerns’ describes how a queried weather phenomenon may be generally hazardous to aviation activities. Thereafter, a section for ‘Service Providers’ explains how weather phenomena impact airports and enroute activities. These two subtopics are further broken down to show how phenomena may (a) in the case of airports, impact towers, flight service stations (FSS), airport authorities, and area control centres (ACC), and (b) in the case of enroute activities, have an impact on air traffic control (terminal, low-level and highlevel ATC). How weather phenomena relate to ‘Users’ such as commercial flight dispatchers and general aviation pilots is fully and finely disseminated under the ‘Aviation’ tab.

The Aviation Meteorology Reference is new, impressively thorough, and ripe for further informative development. Its purpose is to enhance user understanding of weather terminology, to foster better decision-making, and to improve weather-related risk management. It’s an excellent learning tool. What it is not intended to do, however, is to provide actual weather forecasting for flight planning. That remains the stronghold of flight service specialists towards whom pilots should always be pivoting for weather briefings prior to every flight. Nevertheless, anyone can do well to visit avmet.navcanada.ca to check out the new website. You’re guaranteed to learn a bit more than a thing or two and, thereafter, to better understand everything your briefer wants you to know before you head out for a flight.

Passengers ... I’m not talking about those folks (now often referred to as guests) who are travelling in large aircraft with flight attendants, but rather those passengers who are flying in airplanes and helicopters with less than 19 seats. Having spent a lifetime of flying passengers almost entirely in these aircraft (except for the Douglas DC-3, which didn’t require a flight attendant), I have many memories of those folks who had a more intimate relationship with the pilot(s). When I use the term “intimate,” I’m not referring to the couple who joined the “mile-high club” in the back of my Twin Otter on a late winter evening’s commuter flight between Montreal and Ottawa; I am talking about those passengers who get a cabin safety briefing from the cockpit crew and, in single-pilot aircraft, often get to sit in the right front seat.

The gamut of passengers is wide and ranges from the young to old and first-timers to seasoned veteran flyers. Looking back on flying ‘pax’ mostly, in the likes of Piper Cubs, a variety of Cessnas, Beavers, Otters, Twin Otters, Grumman Gooses, Beechcraft King Airs, and DC-3s, equipped with wheels, floats or skis, the memories abound.

I do remember the commuters, in Twin Otters, between Ottawa and Montreal and between Vancouver and Vancouver Island, but more memorable were the host of individuals on commercial charter flights, on government aircraft and, later in retirement, on private aircraft. Forestry personnel, firefighters, fishermen, hunters, prospectors, geologists, diamond drillers, scientists, indigenous families, medevac patients, game wardens, police officers, civil servants, coast guard personnel, captains of industry and the rich and famous are but a few of the types of

passengers in my memory bank.