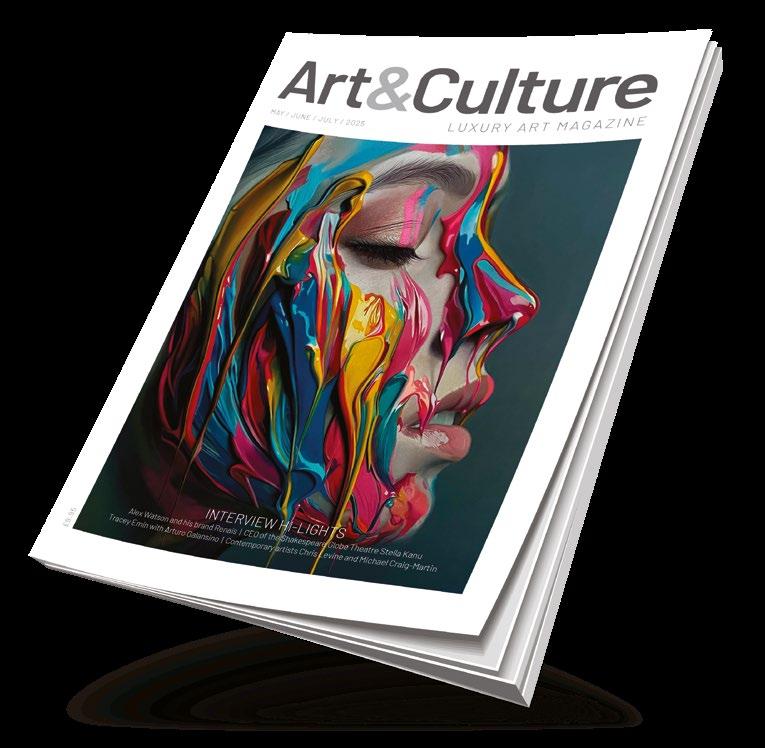

Art&Culture

Our bodies are always shifting and changing, so my work will always serve as a reminder that you are enough.

“The future is often invented with fragments of the past’ .”Hans Ulrich Obrist Tracey Emin

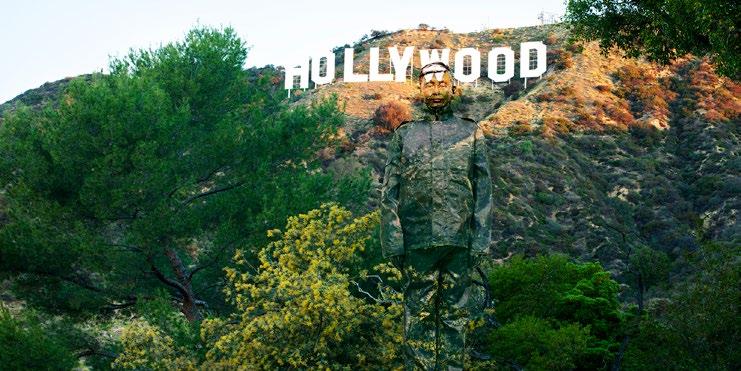

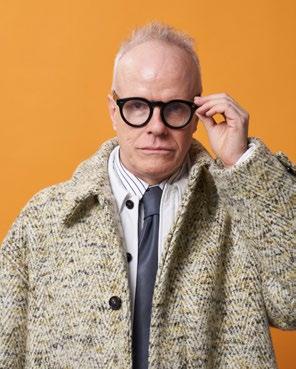

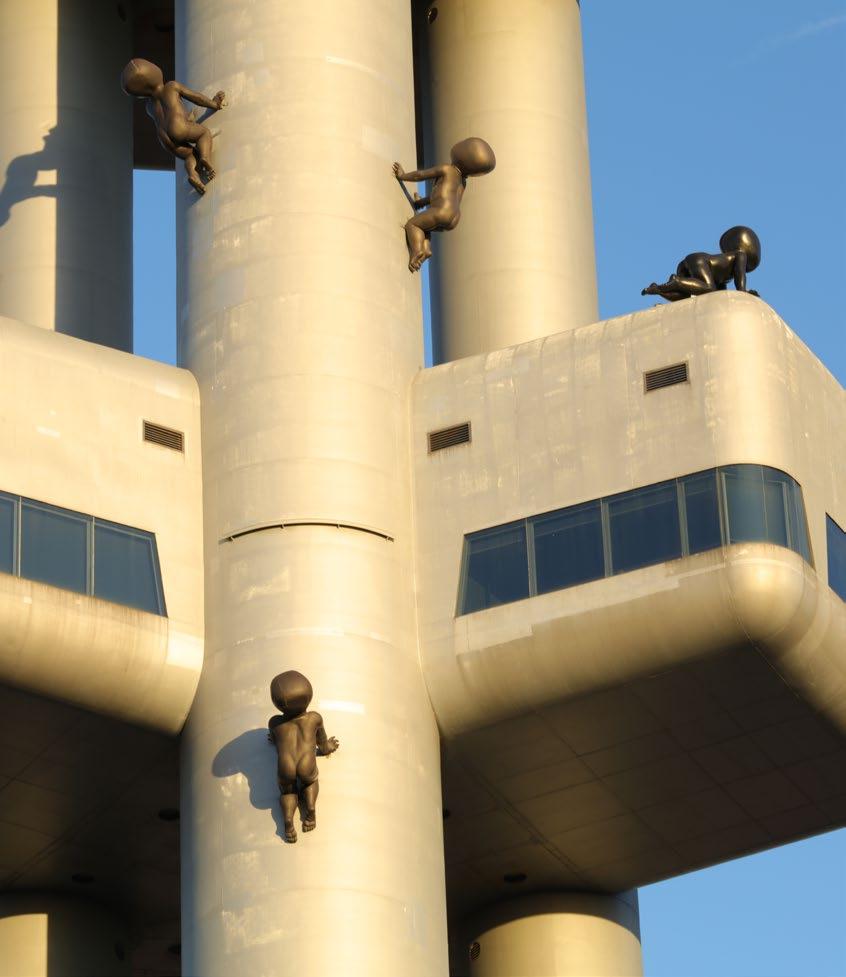

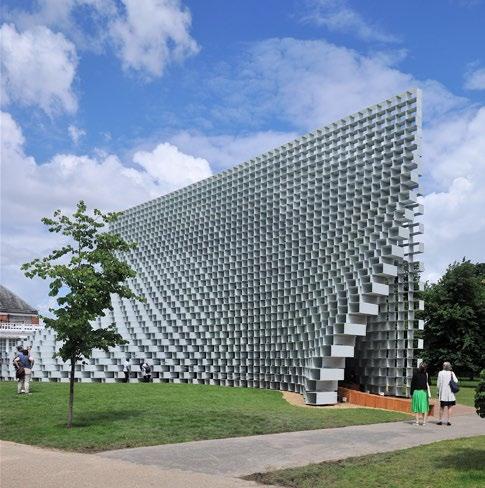

The creation of Issue 6 of the Art & Culture Magazine has been one of my most insightful editions yet. Meeting with some amazing and truly inspirational minds in the cultural sphere always keeps me on my toes and continuously learning and expanding my mind. Whether it’s a statement from the Serpentine’s Artistic Director Hans Ulrich Obrist that really resonates with me, or a wildly unique perspective on art and the world we live in offered by the notorious David Černý, as the magazine continues to grow, so do I on a very personal level.

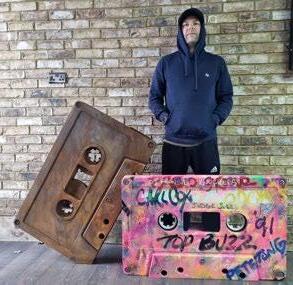

Extending a special thank you to my amazing interviewees who I have had the privilege to speak with and include in Issue 6 of the Art & Culture Magazine; I am delighted to present various exclusive insights from cultural icons who continue to shape the art world today. From the daring and contentious installations of David Černý which greatly pushed political boundaries in the Czech Republic, to Liu

Bolin’s iconic pieces where he seamlessly blends into any given background, labelled as the ‘Invisible Man’. Diving into the importance of breaking down elitist barriers by bringing art into the public realm with Hans Ulrich Obrist has been eye-opening and such a fruitful academically charged experience. Finishing off Issue 6 with a remarkable interview with Sophie Tea and her revolutionary artistic endeavours, this edition is shaped by the most unique cultural perspectives on what art is, and its importance in the world today.

As we traverse a world of cultural literature, Issue 6 of the magazine presents a deep dive into a variety of academic reflections written by our wonderful students from the worldrenowned Courtauld University who specialise in the History of Art. From monumental sculpture work such as the Terracotta Army in China to analyses on the iconography of Star Wars and Studio Ghibli, Issue 6 provides a plethora of topics and thematic concerns for every art and culture lover.

Exploring various movements within the art historical timeline, we notice that ‘the future is often invented with fragments

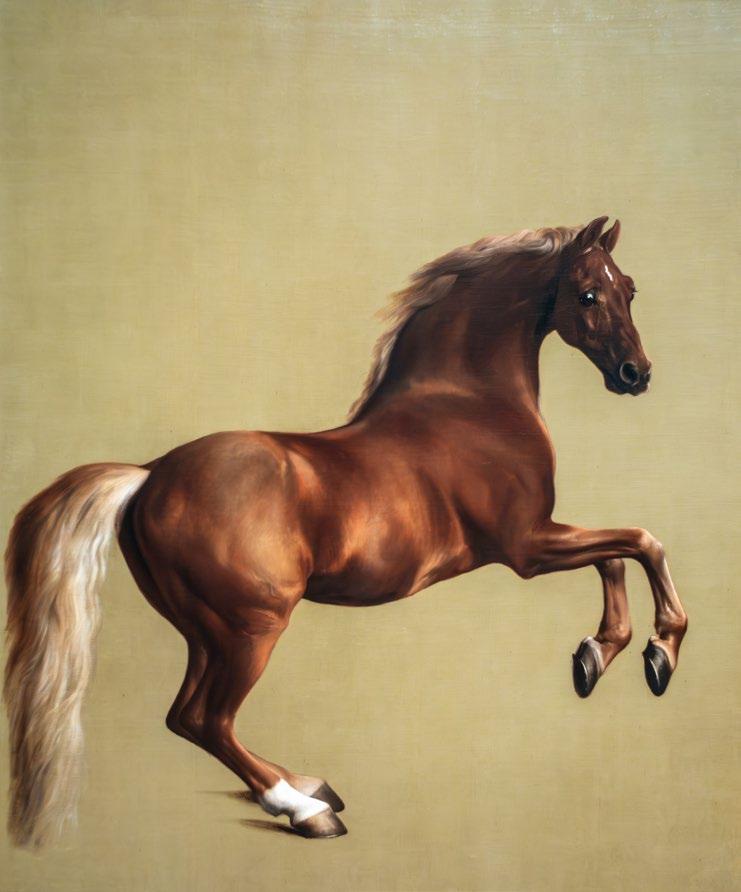

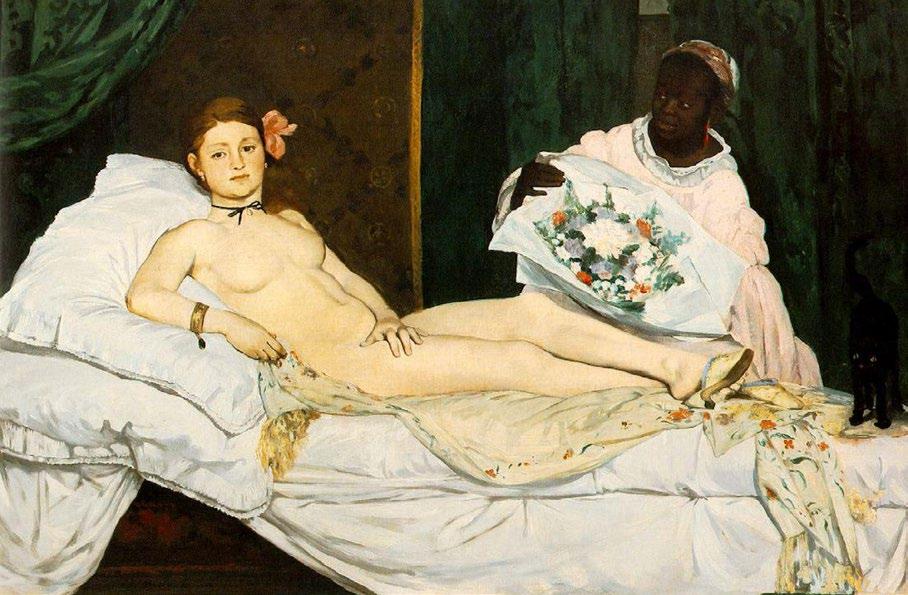

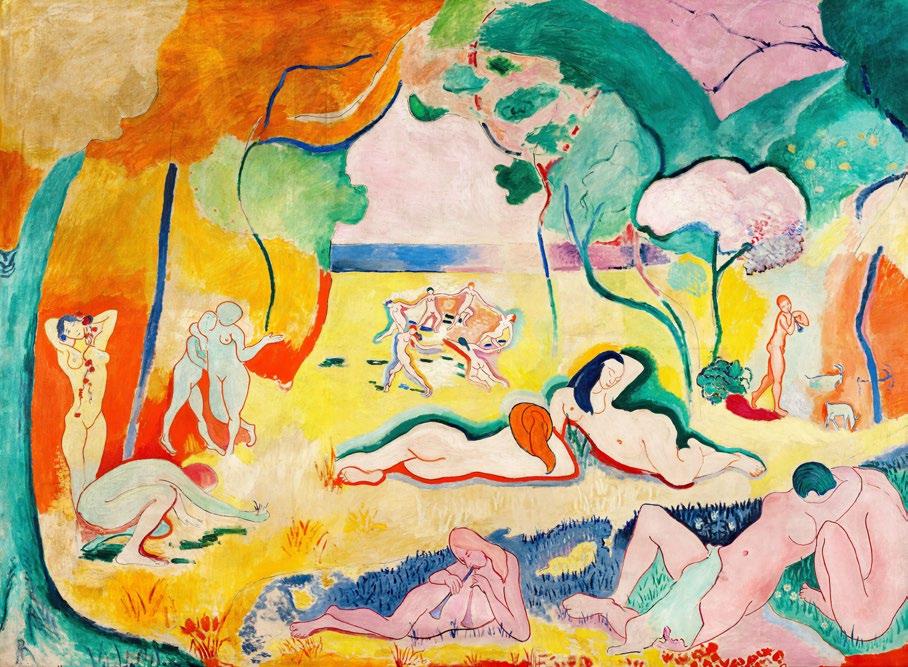

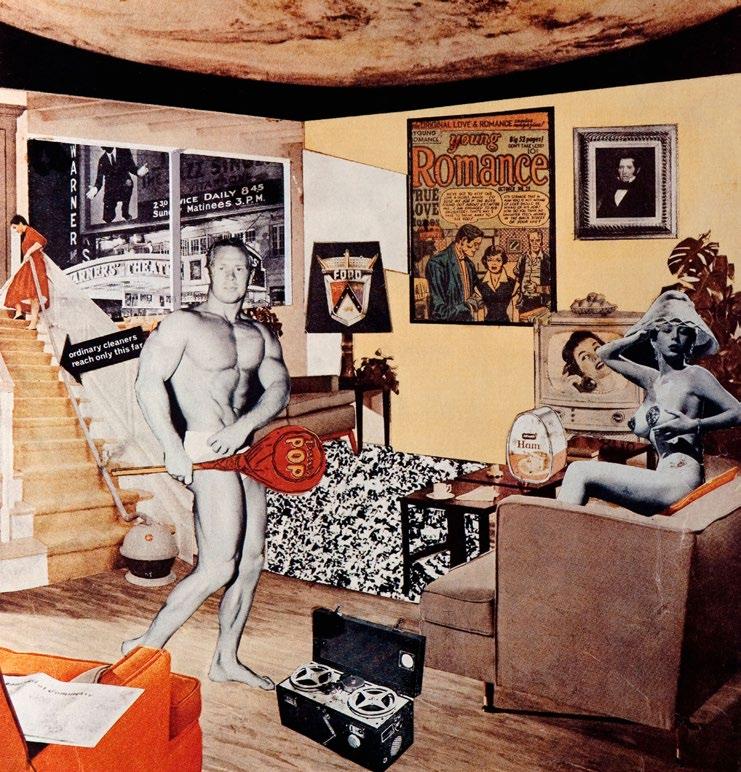

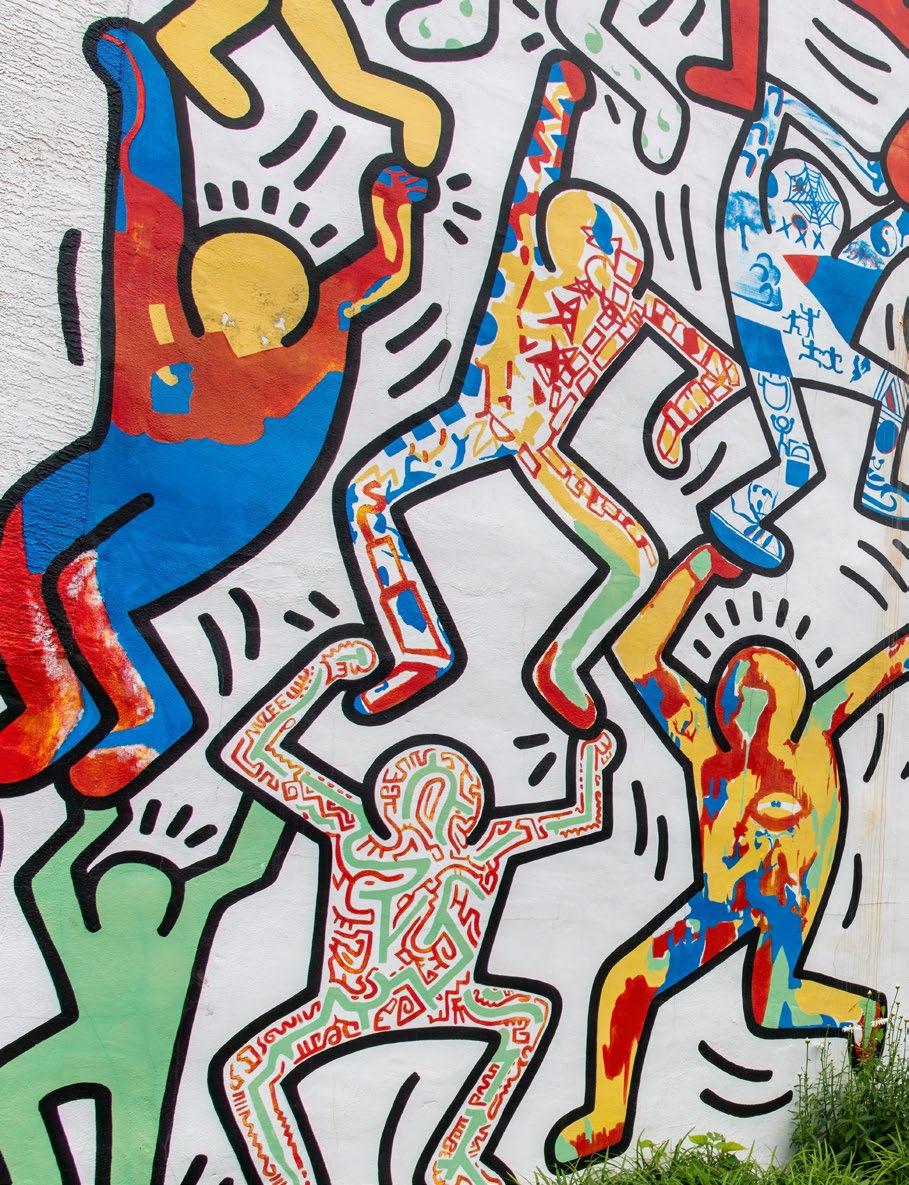

of the past’. Issue 6 spans from the Dutch Golden Age all the way to the Fauvist style. Highlighting key artists who have shaped the art world, we present a variety of articles to include an exploration of Manet’s famous Olympia, Pop Art’s extravagant Richard Hamilton and Keith Haring, and our contemporaries such as Takashi Murakami and Zanele Muholi, whose creative outlook and activism has greatly influenced today’s visual language.

Crafted with the greatest care for all our faithful readers, as you turn each page, we invite you to pause, reflect, and let the work within spark your own imagination. Thank you for joining us on this journey through the ever-evolving world of art and culture.

With love always, (Editor in Chief)

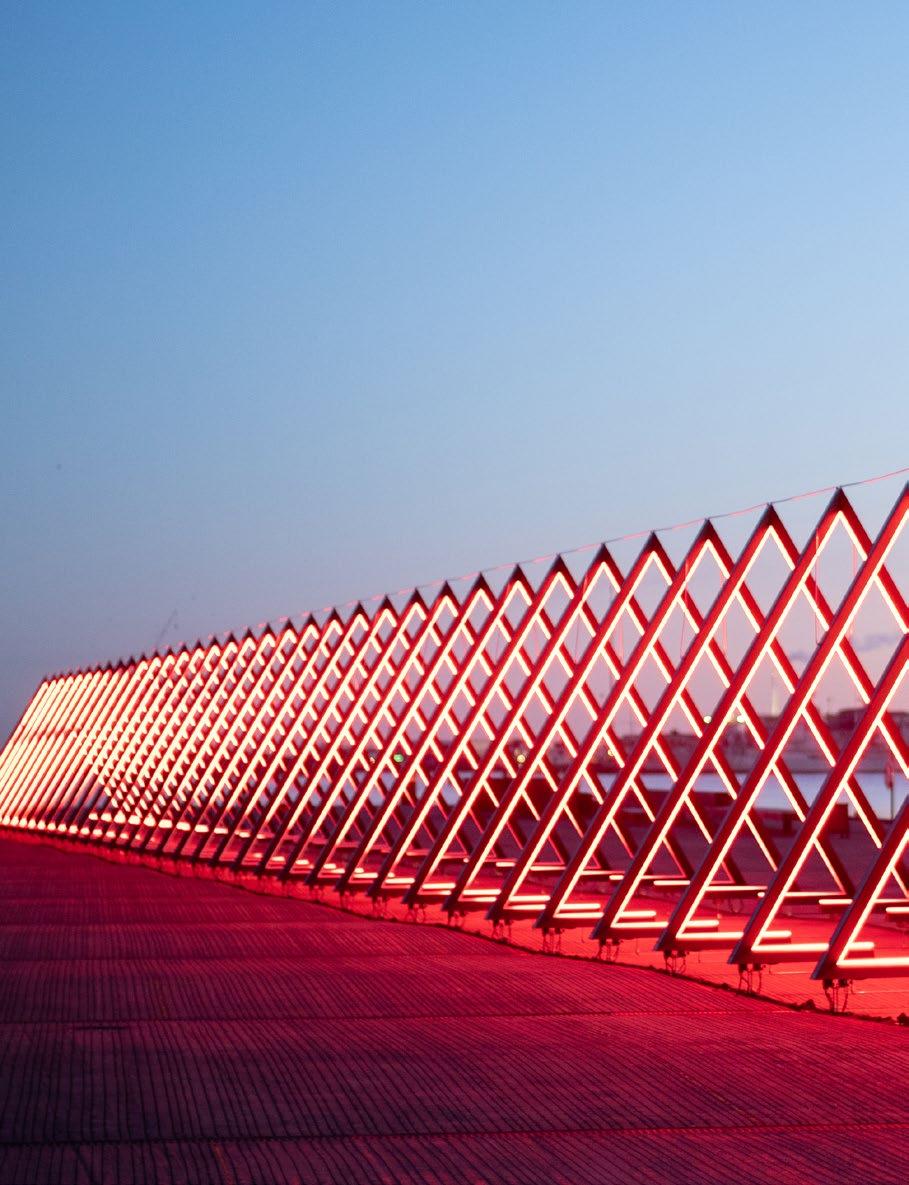

The 3 images within my editorial are taken from my travels.

Editor in Chief

Tamara Bell tamara@outsideinmedia.com

Assistant Editor

Sophie Macdonald sophie@outsideinmedia.com

Magazine Designer

Emma Long Graphic Design emma@outsideinmedia.com emmadesign.co.uk

Contributors

Tamara Bell

Aiden Bell

Francis Devincenzi

Jo Ward

Francesco Scalici

Sophie Macdonald

Anthony Loddo

Elinor Gass

Photography

Sophia Jactel

Malaika Rahimtoola

Evelyn Heis

Vuk Winrow

Kitty Perring

Maya Stoilova

Jessica James

Phoebe Noble

Artist photography supplied by the artists.

Specific photo credits on the article pages.

Stock photography by Alamy, Shutterstock, Unsplash & Pexels.

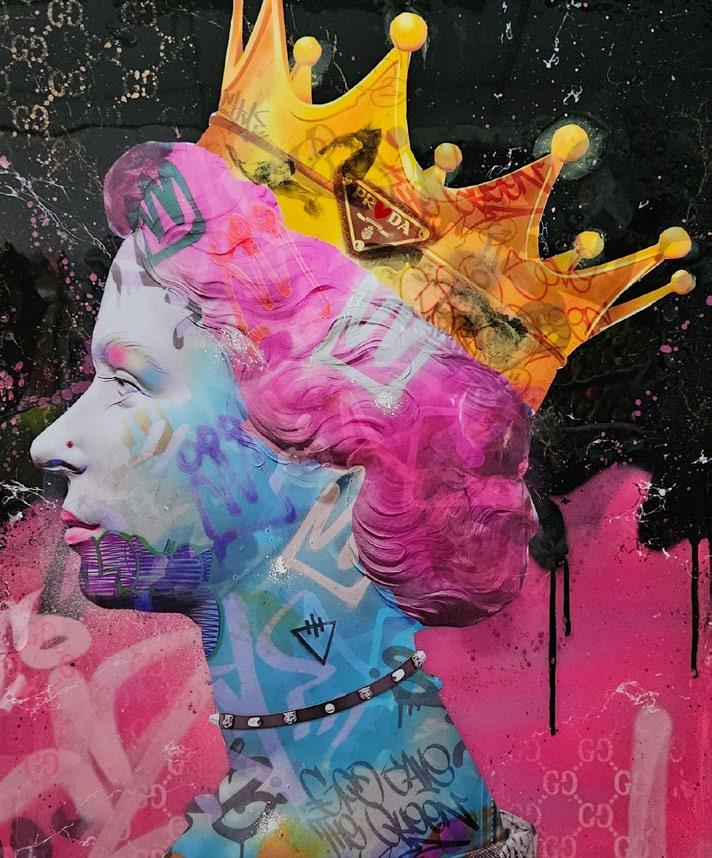

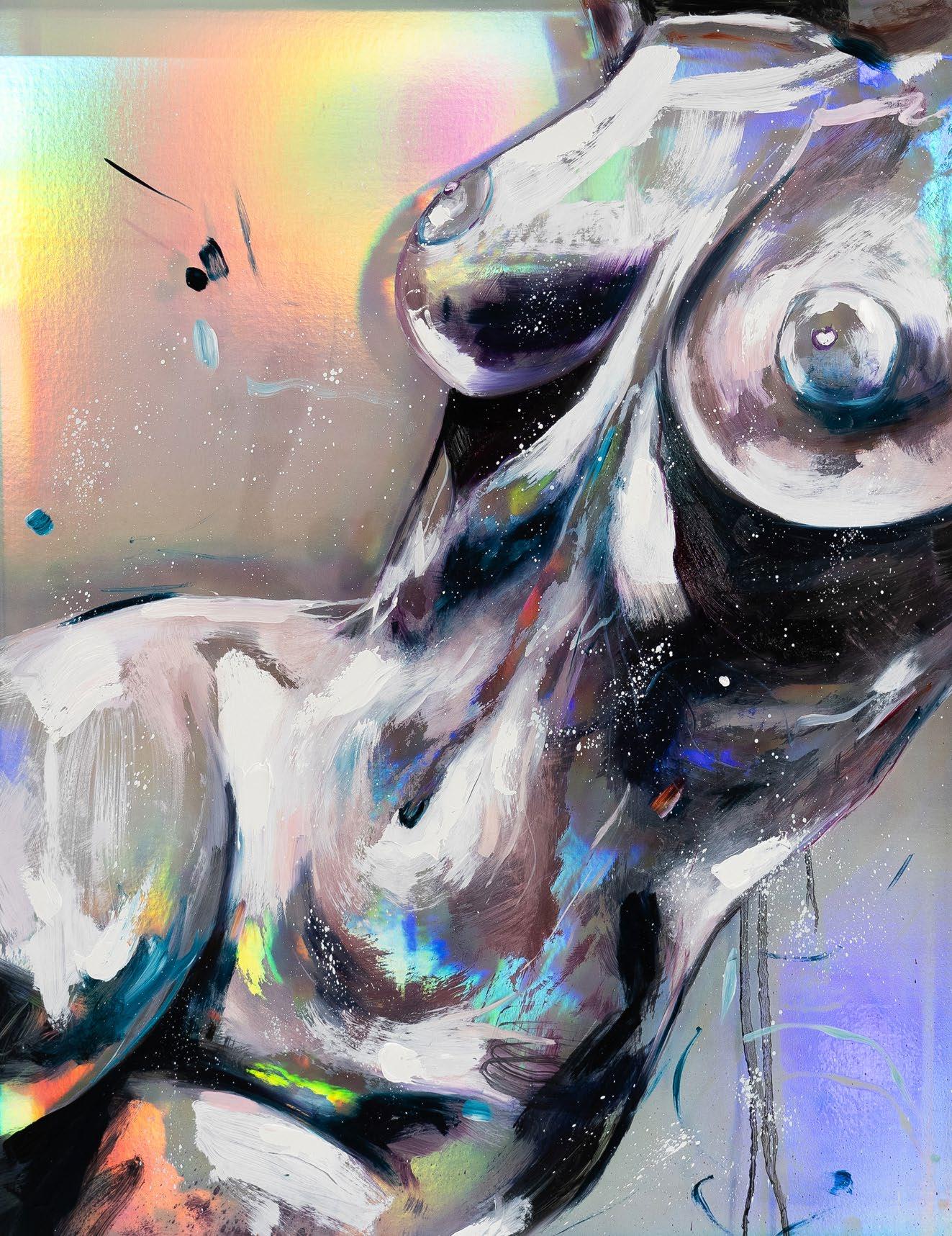

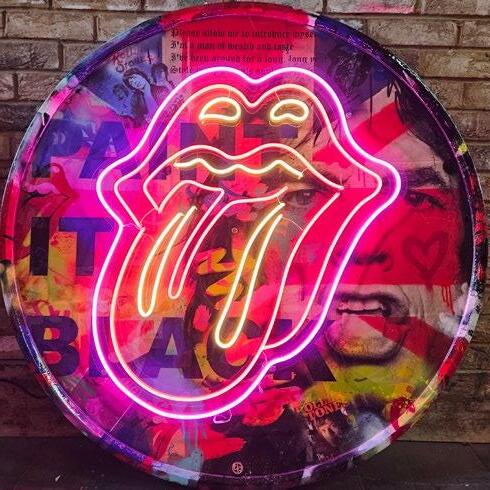

Cover image

Artwork by Dan Pearce.

Art&Culture Magazine

Published by Outside In Media Limited 7 Bell Yard London WC2A 2JR

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

The name Art & Culture Magazine is a mark of Outside in Media, used under exclusive licence. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher.

Art & Culture Magazine places great importance on the accuracy of the information contained within this publication but cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Views expressed by contributors and/or correspondents do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher. Neither Art & Culture Magazine nor Outside in Media is responsible for any claims made, or material(s) used in advertisements.

For permission to copy cuttings for internal or client use, please contact a&c@outsideinmedia.com

As early as 1500 BC a civilisation wrapped in deep and rich culture emerged in parts of Southern and Central America that we know today as Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador. Remnants of the Maya culture can be seen reflected in our modern day, despite evidence of their existence dating back as far as 3,500 years ago.

Similar to other civilisations, the Maya people worshipped a distinctive and intricate pantheon of gods and goddesses associated with various elements of divinity, life and the cosmos. Ix Chel, for instance, was revered as the goddess of health, medicine, childbirth and fertility. In stark contrast, Ah Puch was one God of death, being closely linked with the underworld. At the centre of their belief system stood the supreme creator deity, Itzamna, who was believed to be the omnipotent, almighty being that brought the world, humanity and the renowned Maya calendar into existence.

Maya people are known to have utilised art to not only worship their great deities, but as a profound means of expression and communication, relating to their daily lives, historical events and conveying early astrological knowledge.

They showcased ritualistic offerings manifested in both creative art and at times blood sacrifices, to their gods, kings and citizens of political importance. By melting down metals like gold and silver and carving out precious and regular stones, clay and ceramics indigenous to the region, sculptors would have formed pottery, figurines, masks, jewellery and other vessels to depict mythical scenes. Revelling in deep lore and stories of their culture they would have used bright paints derived from coals, minerals and plants mixed with thick tree sap, natural resins or animal fats to blend the substances

and adhere them to certain tricky surfaces like bark, stucco walls, smooth pottery and paper books.

Brushes made from wood and animal hair would have been used to apply these paints imbued with symbolic meaning, of contrasting colours. Frequently used in Maya art is yellow and red, which represented life and blood. These were made from clay-like minerals such as haematite for red tones

and limonite for citric and yellow tones. Also seen often is black, derived from crushed charcoal or soot and was used to depict dark and eerie scenes of the underworld. White was made from burning limestone, representing the zenith and broader cosmological beliefs, educating in the current stance of understanding and navigating the night sky. Greens and blues were more complex, combined from the anil plant and a distinctive type of clay called ‘palygorskite’ in order to cultivate a highly durable new turquoise colour, even in modern standards, for which is famously named ‘Maya blue’. This turquoise colour was used to represent divine entities and celestial phenomena, often associated with harvest, rain and the sky. This colour has stood through thousands of years of weathering and chemical degradation, allowing it to be seen even more vibrant today.

These brightly decorated artifacts, or even adorned animals and human sacrifices would be offered in payment for relief and protection from the pressing hardships of the current era, such as drought, famine and war. This same symbolic style of art was used to create shrines or worship and sacrifice, murals dedicated to specific geological, political and religious areas, sculptures of their kings and gods, or even on the grand walls of religious Maya structures and palaces, renowned for their layered pyramid shapes. Inscriptions, symbols and drawings of individuals with high status during the

period were discovered etched across the interiors of these monumental buildings, similar to that of the great pyramids of Ancient Egypt, telling us their great ancient stories. The figures painted can be seen adorned in the traditional attire, feasting, surrounded by servants or playing games, donning large meticulously detailed headpieces made from animal heads, beads and feathers. Inscribed even on gold and silver coins were not words of any particular language, but markings of glyphs, insects, faces and miniature scenes which had certain meanings. Through these records, the Maya preserved a legacy that would have otherwise been lost to the decay of the ages.

Echoes of this culture resonate in the present day in many forms of artistic expression. Influences of traditional weaving techniques, intricate embroidery and vibrant colours celebrate the indigenous Maya heritage in current fashion on global runways. Their style of wrapped skirts and rustic bohemian handbags and accessories made from sustainable materials and dyes, add a touch of artistic flare to the industry, reminding us to value human culture, craftsmanship and longevity over fast trends and meaningless media influences.

Contemporary artists often draw inspiration from ancient cultures such as the Maya and use their symbolic depictions, animals

and geometric patterns to convey a philosophical or spiritual meaning. Street artists, particularly in Latin America, continue to inspire others by challenging the mainstream narrative, incorporating Maya art and fusing it with modern styles. This empowers and reclaims their identity. They incite conversations with their art about their history and marry the identity of the past with the present.

By Aiden Bell

“Maya people are known to have utilised art to not only worship their great deities, but as a profound means of expression and communication.”

There are countless wondrous aspects about our world and the vast cultures inhabiting it. Perhaps the most astonishing of all are the gigantic monoliths and structures carrying secrets within, shrouded in mysteries, lurking beneath the soil for thousands of years waiting to be uncovered.

From the city of Pompeii preserving its architecture in ash for nearly two thousand years, or the pyramids raised by a long-lost race of ancient beings. These remnants of the past continue to captivate the imagination of those seeking answers to the what, why and how of the world and our species.

In March 1974 a group of Chinese farmers unearthed something that would change our view of ancient China and add yet another addition to the repertoire of Human-kind’s unbelievable marvellous feats. Yang Zhifa,

an ordinary farmer by trade, along with his family began to find simple fragments of pottery when digging a well for their village in Xiang, a region renowned for its underground rivers and springs. The deeper they found themselves digging for water, the more they found fragments of the Ancient Qin Metropolis, a tomb to house the remains of the first Qin Dynasty Emperor. Tiles, clay pots, chunks of millennia-old masonry came first which furthermore urged the archaeological community of China to investigate.

The official excavations have taken decades, the process of which is still ongoing over fifty years later with new discoveries still happening today. The contents of this underground metropolis housed over two thousand soldiers decorated in accurately represented armour and uniforms of the Qin Dynasty standing guard for their noble emperor resting in his tomb.

Although the figures were mostly military, there were some alternatives found, such as acrobats, musicians and government officials to keep him company. No two figures are alike, all of which with unique facial expressions, clothing, weapons, hairstyles and postures, some of which can still be seen with traces of colours, and although most of the pigment has faded to the ages, scientists have been able to recreate what those colours may have looked like with small processed samples of the remains using modern technology.

This extreme attention to detail is not only a testament to the craftsmanship and ambition of the government labourers and artisans who were instigated to construct this army of soldiers, but also to the grandiose importance of the emperor Qui Shi Huang himself, whose life after death not only required such protection, but to the scale and detail the likes of which has never been seen before. Although being only

13 years of age, most decisions regarding the structure of the tomb, as well as the construction and placement of the soldiers therein were made by the emperor’s advisors and officials.

To create an army of this scale, one can only imagine the toil and labour it took to achieve this feat. To sculpt the human figures alone would have taken a very long time, so it is thought that approximately three quarters of a million labourers were brought in from distant corners of the empire to work on the soldiers, including potentially conscripted workers, lending itself to the individuality of each sculpture, cultivated from the vast expanse of cultures across the whole of China.

Accompanying the Terracotta Army and the remains of the emperor Qui Shi Huang within his tomb were figurines of horses, cranes, swans and geese, to encompass his vision of the afterlife, ensuring an abundance and variety of life. Even remains from once living animals were excavated from the burial site revealing the highest number of species used for ritualistic purposes after death in the whole of the country despite this being a common practice during these times.

The craftsmen used highly developed tools for the era, utilising kilns to convert clay, made from compacted materials into hard and stable stone. The body parts for the soldiers were shaped and moulded separately before being joined together as

one and personalised with carving knives, detailing the hair, facial features and armour, whereas general template moulds would have been used to mass produce the body parts to maintain consistent proportions and uniformity.

The firing process would follow in the kiln which required a sophisticated air flow filtration system to achieve the desired result, hardening the soft clay. This demonstrates the in-depth knowledge of metallurgic and ceramic skills they

possessed. Once complete, the soldiers and their accompanying species of animals would have been beautifully painted by hand in bright colours, reflecting the afterlife that was meant for the young emperor.

Could this just be the beginning of the excavations of the Terracotta Army and if so, what other mysteries await our discovery of them, deep within the earth?

By Aiden Bell

“These remnants of the past continue to captivate the imagination of those seeking answers to the what, why and how of the world and our species.”

I began researching this article with a simple curiosity: how did sixteenth and seventeenthcentury portraits speak through objects, particularly through jewellery? I found myself returning again and again to the question of ownership and authorship within the paintings. Were these necklaces, brooches, and hairpieces drawn from the sitter’s own wardrobe items recorded in family inventories or dowries, or were they the artist’s inventions, imagined or borrowed from studio props?

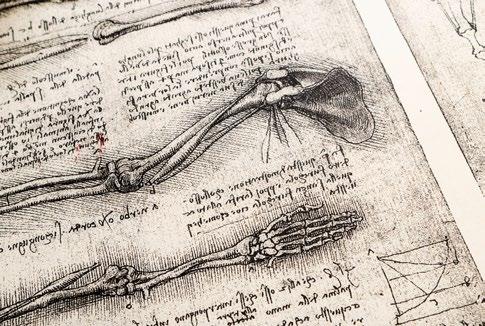

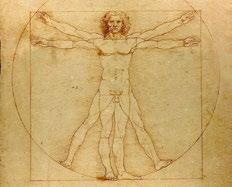

In the process of researching these questions, I encountered an unexpected image: the Zodiac Man. By the early sixteenth century, the Zodiac Man had become a hallmark of medical astrology, widely reproduced, appearing in almanacs, calendars, and printed manuals. It dates back to the eleventh century but gained popularity in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as a visual guide linking zodiac signs to body parts; Aries ruled the head, Virgo the abdomen, Pisces the feet. The body was seen cosmologically, as an interconnected system.

Though its scientific authority waned in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, replaced by observational anatomical illustrations, the Zodiac Man remained culturally influential. You may be wondering why a discussion of jewellery begins with such a figure. But there is, as they say, method in the madness. If we approach portraiture using the logic of the Zodiac Man, treating the body as a symbolic map, we open up a new way of reading adornment. What if the decorated body in portraiture is

not simply a display of fashion or status but a sequence of meaning, from head to waist, where each zone carries its own emotional, iconography and dynastic weight?

The Zodiac framework offers, in turn, a compelling structure for analysing how jewellery operates in portraiture, not as mere embellishment but as iconography and symbolism. If we begin with the logic of the Zodiac Man, where Aries governs the head, the seat of reason and identity, then it makes sense to start here. In Renaissance portraiture, the head was never neutral. It was charged with symbolism: the noblest part of the body and often the most adorned. Hair and headdresses acted as visual codes. Veiling for example signalled modesty, braiding - domestic virtue.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, neck and shoulder jewellery was more than decoration. It served as coded statements of power and communicated status, belief, identity, and marriage. Loose chains or multiple strands signalled grandeur, while religious or mythological pendants worn near

the heart expressed devotion or political meaning. Women displayed a broader range of styles than men, from close-fitting en esclavage necklaces adorned with delicate cameos and carved reliefs, to long strands of flat, geometric gold links. Lavinia Fontana’s Portrait of a Noblewoman offers a striking glimpse into Bolognese fashion. Her brush, as precise as a paparazzo’s lens, meticulously captures every gold stitch, lace flourish, and delicate jewel. Painted shortly after the sitter’s marriage, recent research into account books and family records suggests this attire closely mirrors a noble bride’s trousseau.

The portrait layers visual opulence: a brocaded gown woven with shimmering metallic threads, strands of pearls coiling elegantly across the bodice, and a heavy gold-linked necklace featuring a darkstoned cross likely garnet or jet resting close to the heart. Crosses were often part of a jewelled carcanet, and were a powerful symbol of religious devotion, dynastic ties, and wealth. Worn not only by women but also men and children, these crosses, positioned prominently on the chest, served as both spiritual and social emblems.

“The Zodiac framework offers, in turn, a compelling structure for analysing how jewellery operates in portraiture, not as mere embellishment but as iconography and symbolism.“

PORTRAIT OF ELEONORA DI TOLEDO WITH HER SON GIOVANNI

Another popular accessory of the time appears in Bronzino’s Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo with her Son Giovanni. She wears two pearl strands: a shorter one with a diamond pendant nestled at her throat and a longer ceremonial necklace of large Venetian pearls. Recorded in Medici inventories, this 50-pearl strand was likely a wedding gift from Cosimo de’ Medici, purchased by Eleonora’s mother-in-law, Maria Salviati, along with a diamond ring.

Fontana, too, uses pearls; she developed a unique way of painting their luminous surfaces to animate her sitters. Waistbelts marked wealth and status in portraiture, drawing attention to the waist as a symbolic boundary between the upper and lower body; the higher and baser instincts of humanity. Following the Zodiac Man’s logic, the waist is a transition zone, linking sovereignty and communication.

As fashion favoured a narrow waist, belts became prized accessories. Noblewomen’s trousseaux often included belts of gold thread, enamel, and precious stones. At the extremity of the body, the hands linked to the astrological signs Gemini and Virgo; symbols of intellect, dexterity, and communication. Hands also held rich expressive potential, called ‘the instrument of all instruments’, they communicate as clearly as words. Recurring gestures like offering a ring or touching fabric

form a shared visual vocabulary, a grammar of status, piety, and selfhood coded in both gesture and adornment.

In Fontana’s Marriage Portrait for example, the sitter’s hands gently touch a lapdog and a jewelled zibellino, symbols of fidelity, while rings and embroidery further narrate marital identity, class, and virtue. I began with a simple question: how did jewellery speak in sixteenth and seventeenth-century portraits?

I end with the recognition that decoration goes beyond adornment. It serves as a coded language that reveals identity, history, power and more. Whether real or imagined by the artist, these adornments bring portraits to life and add depth to our understanding and to the meaning communicated in these important objects.

By Kitty Perring

In the study of art history, the focus is often on the artists themselves, with a deep dive into visual analysis that leaves the viewer responsible for deciphering what makes a painting, sculpture, or other artwork unique. However, the success of the famous artists we recognise today can largely be credited to those who worked behind the scenes to endorse them and often risked harsh criticism for the works they chose to collect or exhibit.

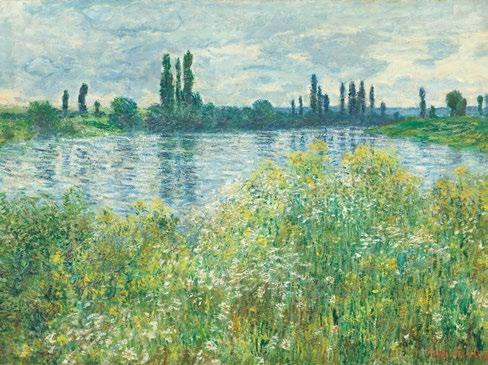

The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists represent a group of artists from radically different financial backgrounds, and their long-lasting legacy — despite initial public rejection — offers a series of examples of how collectors and gallerists propelled their careers. For example, painters Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Vincent van Gogh relied heavily on the financial and emotional support of collectors Gustave Caillebotte, Paul Durand-Ruel, and Johanna van GoghBonger, respectively.

Claude Monet struggled financially for many years, often relying on regular cash instalments from Gustave Caillebotte, whose upper-middle-class lifestyle made him happy to comply. Caillebotte would purchase artists’ work for two or three times the asking price, keeping Monet and Pissarro afloat during much of their careers. Despite Monet’s eventual acceptance by the public and subsequent wealth, he would not have been able to continue making his work

without the few supporters who bought his paintings at inflated prices, introduced his work to other wealthy patrons, and helped establish his place in the art historical canon. Emotional support was just as significant as financial support in many cases. Caillebotte frequently attended his friend’s auctions, displaying a conspicuous interest in Monet’s work in front of other connoisseurs. His intended bequest of 67 artworks to the French state after his death in 1894 paved the way for multiple Impressionists, resulting in the first state-run Impressionist exhibition and giving collector Ambroise Vollard the courage to host Paul Cézanne’s first solo show. Even throughout the 20th century, modern and contemporary artists would continue to celebrate the Impressionist works in this bequest through reproductions and reinterpretations.

Impressionist Alfred Sisley also relied heavily on external support. While he was initially able to paint for pleasure, his father’s business failed during the Franco-Prussian War, forcing Sisley to depend solely on the sale of his paintings for income. Paul DurandRuel loyally supported Sisley’s work from 1872 onward, continuing to buy and sell the artist’s paintings despite his own financial difficulties. At times, Durand-Ruel requested specific styles, subjects, and sizes of works from Sisley to appeal to the market he was selling to. Sisley’s continued struggle to sell his paintings led to an agreement with

Durand-Ruel in 1880, in which Sisley sold at least 357 works to the collector between 1872 and 1886. During this time, Durand-Ruel faced his own financial challenges and was unable to sell Sisley’s paintings, leading to a fallingout between the two men that lasted for the rest of their lives. Nonetheless, DurandRuel’s unwavering support ensured Sisley’s posthumous success, contributed to the evolution of his technique, and secured the long-term conservation of his artwork.

Another artist whose legacy relied heavily on the support of others was Vincent van Gogh. While his brother Theo provided financial assistance during Vincent’s lifetime, it was Theo’s wife, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who played a pivotal role in the distribution and recognition of his artwork after both Vincent’s and Theo’s deaths in 1890 and 1891. She collected and catalogued his work, sending paintings to various exhibitions, though initially with little success. Nevertheless, she dedicated the rest of her life to showing the world the beauty of Vincent’s work, including publishing a collection of his letters. These letters, along with the paintings she exhibited, shaped the perception of Van Gogh as a tortured artist plagued by misfortune, yet able to create profound beauty. While this perspective may oversimplify Van Gogh’s life, it illustrates the extent of Johanna’s influence in crafting his legacy.

While art history often centres on the genius of individual artists, the enduring legacies of now-famous artists such as Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Vincent van Gogh reveal a far more complex ecosystem. The efforts of Gustave Caillebotte, Paul Durand-Ruel, and Johanna van Gogh-Bonger were not merely acts of patronage but also acts of belief— investments in talent that had yet to be fully recognised. These supporters took financial and reputational risks that ultimately shaped the trajectory of modern art. Their contributions remind us that the success of many celebrated artists depended just as much on those who believed in them behind the scenes as on their own creative brilliance. Reconsidering the role of collectors and promoters challenges us to expand our understanding of artistic legacy beyond the canvas itself.

By Elinor Gass

“Their contributions remind us that the success of many celebrated artists depended just as much on those who believed in them behind the scenes as on their own creative brilliance.”

In the landscape of public commemoration, monuments traditionally serve as permanent markers of collective memory, towering declarations of what a society chooses to remember and how it wishes to be remembered. Yet in 1986, artists Jochen Gertz and Esther Shalev-Gertz challenged this fundamental assumption with their revolutionary Monument Against Fascism, a work that questioned whether true remembrance might require forgetting the monument itself.

The concept of the counter-monument emerged from a profound dissatisfaction with traditional approaches to public memory. Conventional monuments impose a singular narrative, telling viewers not just what to remember but how to remember it. They create what might be called ‘official memory — sanitised, unified, and often disconnected from the messy complexity of individual experience.

Gertz and Shalev-Gertz recognised that this approach was particularly problematic when dealing with the Holocaust and fascism. How could any single monument adequately represent such incomprehensible horror? How could static bronze or marble capture the ongoing process of memory, with its contradictions, gaps, and personal variations? Their solution was radical: create a monument that would gradually erase itself, forcing visitors to engage actively with memory rather than passively consuming it.

The Monument Against Fascism began as a 12-metre-high lead-clad column installed in Hamburg-Harburg in 1986. Rather than presenting a finished statement about history, the artists created what was essentially a collaborative canvas. They invited citizens and visitors to add their names alongside those of the artists, transforming the monument from a closed artistic statement into an open democratic process.

The response was extraordinary and troubling in equal measure. Over the course of seven years, the monument accumulated 70,000 names, entries, and pieces of graffiti. This outpouring of public engagement demonstrated the hunger for alternative forms of memorialisation. Yet the responses revealed the complexity of memory itself: alongside respectful commemorations appeared swastikas, hateful messages, and even traces of gunshots in the lead coating.

“The responses revealed the complexity of memory itself: alongside respectful commemorations appeared swastikas, hateful messages, and even traces of gunshots in the lead coating.”

This vandalism was not a failure of the project but its most profound success. By creating space for authentic public response rather than prescribed reverence, the artists revealed the ongoing presence of fascist sentiment in contemporary society. The monument became a diagnostic tool, exposing the reality that the fight against fascism remains unfinished.

The most radical aspect of the work was its planned obsolescence. As each section of the column filled with inscriptions, it was gradually lowered into the ground until, by 1993, the monument had disappeared entirely. This process challenged every assumption about how public art should function. Rather than growing more prominent over time, accumulating symbolic power through permanence, this monument deliberately made itself invisible.

The sinking process created an urgent temporality. Visitors knew their opportunity to engage was limited, that the monument would soon be gone forever. This scarcity transformed the act of inscription from casual interaction into meaningful participation. Each signature became a conscious decision to be part of this disappearing record.

The disappearance of the monument forced a crucial recognition: memory is not a thing but a process. Traditional monuments suggest that memory can be fixed, preserved, and transmitted unchanged across generations. The counter-monument revealed this as an illusion. Memory lives in active engagement, in the ongoing work of remembering, not in passive encounter with permanent objects.

By removing the physical monument, Gertz and Shalev-Gertz transferred the responsibility for memory back to the community. The work could no longer serve as an alibi for remembrance—citizens could not point to the monument and claim they had fulfilled their obligation to remember. Instead, they had to carry the memory within themselves, making it part of their active consciousness rather than delegating it to public sculpture.

The project embodied a radically democratic approach to historical memory. Rather than accepting the authority of experts, institutions, or artists to determine appropriate forms of remembrance, it insisted that memory belongs to everyone who participates in it. The 70,000 contributions created a collective portrait of a community grappling with its past, complete with contradictions, conflicts, and complexities that no official narrative could capture.

This democratic approach acknowledged that memory is always contested terrain. Different groups remember differently, and any honest engagement with the past must account for these differences rather than smoothing them away. The graffiti and vandalism became part of the monument’s meaning, documenting not just good intentions but the ongoing struggle over historical interpretation.

In our current moment of widespread monument removal and contestation, the counter-monument offers a prescient model for thinking beyond traditional approaches to public memory. As communities across the world grapple with colonial statues, Confederate monuments, and other problematic commemorations, the Hamburg project suggests that the solution might not be replacement but process.

Rather than substituting one fixed narrative for another, the counter-monument points toward forms of memorialisation that remain open, participatory, and alive to contradiction. It suggests that the healthiest societies might be those that can hold memory lightly, as an ongoing conversation rather than a settled conclusion.

The ultimate success of the Monument Against Fascism lies in its planned failure to endure. By disappearing, it achieved something that no permanent monument

could: it made itself unforgettable precisely by becoming invisible. Visitors who engaged with the work during its seven-year existence carry memories that no conventional monument could have created.

This paradox reveals the profound insight at the heart of the counter-monument movement: sometimes the most powerful way to remember is to forget the monument and remember the process of remembering itself. In an age of monumental excess and memorial fatigue, Gertz and Shalev-Gertz offered a different path—one that trusts communities to carry memory forward through active engagement rather than passive consumption.

Their disappearing monument ultimately asks whether we need monuments at all, or whether we might find more authentic and democratic ways to engage with the past. In making itself absent, it made memory present in ways that permanent sculptures never could.

By Jessica James

Scan here to see the Monument AgainstFacism

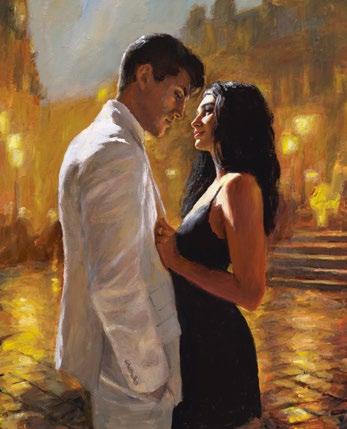

Kiss by

artist Francesco Hayez.

So, what is considered provocative, for me is not.

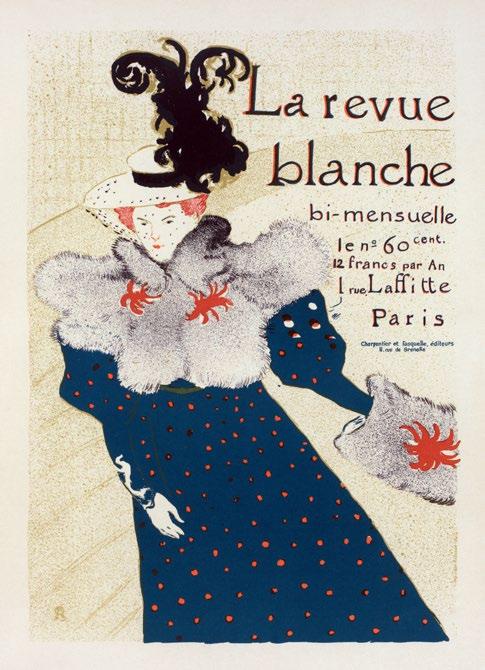

During the Belle Époque, posters and products travelled across regional, cultural, and hierarchical borders. Posters could be easily moved, copied, and reproduced, which distinguished them from other arts of the time. In Paris, the overwhelming quantity and diversity of the posters was specifically shocking, contributing to the role of posters as objects of cultural exchange and instruments of shaping national identity.

One major shift that contributed to the popularity of posters was the rise of imagebased advertising. Unlike traditional textheavy ads, which were accessible only to the literate and those fluent in the language, visual posters could reach a far broader audience, drawing people in with their bright, eye-catching colours and dynamic compositions. This democratisation of advertising sparked controversy. Wealthy men saw the widespread reach of these images as a threat to their exclusive role as the gatekeepers of information within their families and communities. Some voiced fears that women — and even children — exposed to these posters might begin to make their own choices as consumers and active participants in an increasingly informed society. Even if the product advertised was financially out of reach for the viewer, the poster still communicated a message of aspiration and inclusion — one shared across class, gender, and background.

Some poster artists of the time, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, embraced the public’s growing preference for image-based design to experiment with compositions and stylistic elements from abroad. At the end of the 19th century, following Japan’s forced opening to the West by American Commodore Perry, European markets were suddenly flooded with Japanese

goods, most notably ukiyo-e woodblock prints. These prints captivated European artists with their use of diagonal lines, flattened perspectives, bold colour blocks, and strong black outlines. Lautrec and other poster artists incorporated many of these features into their own poster designs, creating the stylistic designs of Art Nouveau.

Another reason these posters were so powerful in Paris was the newly passed Press Law of 1881, which allowed advertisements and posters to be freely posted without prior government authorisation. This ushered in what art historians refer to as ‘affichomania’, a term derived from the French word for poster, ‘affiche’. Suddenly, posters covered every blank wall and were plastered from top to bottom on Morris columns — cylindrical structures originally introduced in 1868 to regulate street advertising. But by 1881, with few restrictions remaining, posters proliferated throughout the city. While many embraced this explosion of visual culture, others were outraged by what they saw as a vulgar intrusion into daily life, lamenting the loss of the traditional beauty of Parisian streets.

The ‘New Woman’

The third reason these posters provoked societal tension was the emergence of the new woman. This archetype embodied independence, as the new woman asserted herself through her choices as both a consumer and an active participant in public life beyond the domestic sphere. Posters of the time did more than advertise products or experiences — they sold lifestyles and aspirations. Women in posters were often portrayed as autonomous, sexually liberated figures who welcomed the public gaze.

“Belle Époque posters redefined public spaces into a visual marketplace and changed the role of advertising forever.”

These women symbolised a bold departure from traditional female roles. They were independent consumers, navigating public space on their own terms. Seduction was a common technique in Belle Époque advertising, with female sexuality repeatedly used as a tool of persuasion, artists depicting women scantily clad and posed seductively to shock passers by into attention.

The rise of the new woman typically represented in these posters challenged traditional expectations of female modesty and domesticity, disrupting long-held Victorian ideals of femininity. While the early 19th century emphasised modesty, restraint, and domestic virtue, the Belle Époque celebrated a more liberated and visible woman. Advertisements capitalised on both fascination and anxiety surrounding these changes, portraying women as symbols of modernity and independence while simultaneously catering to the male gaze.

Posters didn’t just democratise public space — they also transformed the act of collecting art. Traditionally, collecting was reserved for wealthy men with access to oil paintings and sculpture. But with the rise of lithographic posters, art became more accessible. The ‘affichomania’ helped propel poster exhibitions and collecting into the

mainstream, inviting a much broader public to engage with visual culture. The practice of collecting expanded significantly with the rise of printed material, challenging and broadening traditional notions of what it meant to be a collector. Poster collectors were often labelled amateur art enthusiasts with a deep passion for visual culture, though not always regarded with the same seriousness as collectors of fine art. In response to this growing audience, some artists began producing limited edition prints specifically intended for private display rather than public advertising. These posters were printed on high quality paper and collected by dealers like Edmond Sagot,

whose gallery catered to a more affluent clientele that preferred their art unlinked from overt commercialism.

The explosion of poster art in Paris during the Belle Époque represented more than just an artistic trend; it provided visual documentation of a rapidly evolving society. Belle Époque posters redefined public spaces into a visual marketplace and changed the role of advertising forever, prompting reflection on how the world would look without image-based advertisements posted in public spaces today.

By Elinor Gass

The Blue Rider movement emerged as a fundamental force in modern art development during the early 20th century. Munich artists established a new group by abandoning conventional art techniques to explore abstract spiritual painting methods. Blue Rider artists delivered strong spiritual and emotional messages through their use of bright colour palettes and enigmatic subject matter.

Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc founded the Blue Rider movement in 1911 which then became an integral part of European avantgarde art during the early twentieth century. The movement drew creative inspiration from Vincent van Gogh’s expressive use of colour and symbolism’s mystical themes through Post-Impressionist techniques. Marc and Kandinsky’s artistic collaboration developed through multi-sensory expressions which synaesthesia allowed. The integration of Russian folklore and German Romanticism principles led to the development of a pioneering abstract art style in the movement.

The Blue Rider movement established modern art by developing foundational abstract and expressionist principles. New artistic standards created by the Blue Rider movement during its existence paved the way for Abstract Expressionism and influenced artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. The Blue Rider artists established a lasting legacy of spiritual elements which future generations used to create new emotional bonds between artworks and viewers. The movement of modern art developed its uniqueness by rejecting societal norms to pursue individual spiritual discovery.

The central artistic principle of Blue Rider artists focused on symbolic expression. Kandinsky and his artistic colleagues used colour and form selections to channel spiritual forces into their works and foment deep emotional connections with their audiences. The colour blue became a symbol for spiritual concepts and deeper meditation practices.

Kandinsky earned his reputation as the father of abstract art through his Russian painting which incorporated profound spiritual concepts. He understood that visual elements like colour and form could trigger deep emotional reactions in a similar way to music. Composition VII (1913) stands as Kandinsky’s major creation before World War I through its vibrant explosion of colours that moves with a dynamic swirl. This artwork demonstrates his belief that art functions as music while creating spiritual harmony.

Through his animal portrayals Marc expressed purity and natural order to embody his vision of an ideal society. In his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art Kandinsky developed the

movement’s philosophical foundation by examining how various colours and shapes evoke emotions.

The Blue Rider movement included several prominent artists who joined alongside its founders Kandinsky and Marc. August Macke established the movement’s visual identity by using dynamic shapes together with vibrant colours.

As a German painter who partnered with Kandinsky for many years Gabriele Münter made key contributions to the Blue Rider group. Her artwork exhibited bold lines and flattened perspectives which demonstrated her dedication to folk art while rejecting academic norms.

“The Blue Rider artists established a lasting legacy of spiritual elements which future generations used to create new emotional bonds between artworks and viewers.“

more....

ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN I. (1912) Auguste Macke

The Blue Rider artists gathered at Münter’s house in Murnau which she maintained as their meeting place until the group dissolved and she preserved their artwork. Recent decades have seen a growing recognition for her dual contributions to art and archival preservation.

Paul Klee maintained only a loose affiliation with the Blue Rider group, yet he embraced their central principles especially through his symbolic imagery and abstract techniques. Klee’s Swiss origins led to artistic creations that challenge classification while being inspired by musical compositions and dream imagery. Klee’s paintings represent a playful yet deep spiritual vision through their whimsical yet mysterious forms. Senecio (1922) emerged from the remnants of Blue Rider but continues to embody the group’s spiritual and symbolic nature.

Upon its 1912 release the Blue Rider Almanac (Der Blaue Reiter Almanach) emerged as a vital publication for the artistic movement. The ground-breaking publication featured art theory essays with modern and non-Western art reproductions and critical perspectives from artists and composers under the editing of Kandinsky and Marc.

Through the Blue Rider Almanac the group expressed their belief in art as a universal language. The publication showcased a diverse collection of Bavarian glass paintings and African masks as well as Arnold Schoenberg’s musical compositions which displayed the group’s dedication to transcending cultural and artistic barriers.

Expressionism and the Blue Rider movement both focus on emotional expression rather than depicting Realism. Expressionism developed its unique style through strong colour schemes and distorted shapes that communicated profound emotional content. Blue Rider artists used their personal artistic vision and spiritual themes as tools for Expressionists to explore human psychology and the subconscious. The Blue Rider movement established Expressionism through its focus on emotional authenticity rather than realistic representation.

By Jo Ward

“Expressionism developed its unique style through strong colour schemes and distorted shapes that communicated profound emotional content.”

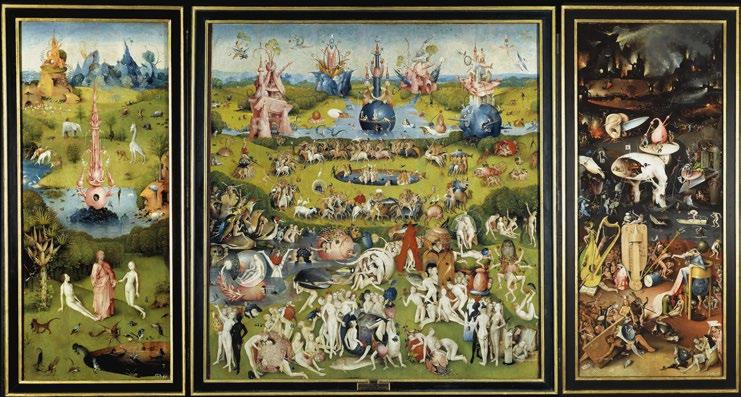

How can the one who knows nothing reveal everything? The figure of the fool – clown, jester, trickster, misfit – permeated artistic spaces from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries. Yet his existence wasn’t just for amusement and ridicule. This character, with his mismatched garb and outlandish actions, was a truth-teller: under his veil of hysteria was an entire subversive language, a social and moral commentary on the pitfalls of the human condition.

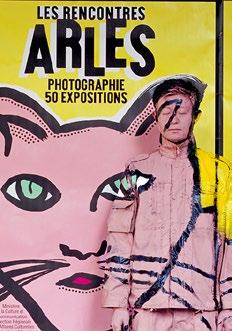

The fool was everywhere, interjecting classical tales, prancing around in disguise, and appearing as a comedic and moral disruptor in visual stories both sacred and profane. In the Louvre’s Figures of the Fool exhibition (2024-25) which closed earlier this year, the curators set out to demonstrate how this perplexing foolish figure was much more than a walking visual trope.

Over three hundred Northern European works brought together from ninety institutions populated the winding rooms of the newly renovated Hall Napoléon, offering visitors a chronological journey through the fool’s art historical lifetime. The physical experience of the exhibition mirrored the fool’s character: walls in rich jewel tones, framed life-sized sculptures and grand tapestries; carved ivory boxes sat in dramatically lit cases; illuminated manuscripts invited close scrutiny; tarot cards and tiny prints revealed the fool’s presence at the smallest scale. In one room, works were even arranged like a tiled floor, leading towards a rotunda display with paintings in arched niches. It was as if architecture itself was a foolish antic, cheekily leading you from one room to the next in anticipation of what might be around the corner.

In art, the fool was at once elusive and ubiquitous. The show opened with tiny illustrations in the margins of illuminated medieval manuscripts, showing fantastical creatures and foolish figures creeping around the edges of text. Immediately, the viewer was summoned to sharpen their vision and look closer. From there, fools emerged across mediums and in varying scale, appearing in household objects, tarot cards, ivory chests, and even stained glass. It seemed that any medium was a match for the fool, whose shapeshifting capabilities let him slither into visual tales both grand and quotidian.

“In life, and in art, he persists — emerging in unexpected corners to remind us, ‘it’s not that serious’. It turns out even those somber medievalists had a sense of humour.

A particularly poignant section explored the fool’s relationship with death. An entire gallery was devoted to ‘danse macabre’ imagery, where death appeared as a jester or a skeleton. In a watercolour copy of Basel’s famous 1439 Dance of Death, death cajoles and charms his mortal partners, gingerly grabbing their arms, interlocking hands, and luring them with theatrical flair into his choreography. The skeleton’s nimble and colourful sleights of hand are a visually striking marriage of the comic and the tragic. As the obliviousness of the mortal figures intermingles with the reverie and frivolous deceit of the dancing skeletons, one is reminded of the extremities of life both wildly absurd and dangerously fragile.

Throughout the show, visual exuberance abounded–whether in the rich textures of costume, the chaotic compositions of satirical etchings, or the grimaces in portraiture. Hieronymous Bosch’s The Ship of Fools (ca.1500-10) stood as a centrepiece: a chaotic tableau of gluttony with a group of revellers feasting and merrymaking on a small boat. In this scene of moral folly, however, the fool isn’t embroiled in the trouble. Rather, he crouches on the makeshift stern of the boat, his back turned to the partiers

as if to let them indict themselves, and thus prompting the viewer to wonder – are we the real fools? The exhibition poster captured this inversion perfectly. A fool in a donkeyeared cap peers through his splayed fingers, flashing a toothy smile at the viewer. In his mask of mockery, he reverses the narrative. Leading with his taunting grin, the fool turns his ‘costume’ to his advantage, reclaiming agency and becoming the one who delivers the punchline. Through satire and mockery, the fool was holding up a mirror to society’s flaws–its moral failings, hypocrisies, and sheer disorder. Writing about this exhibition thus adds a layer of meta-critique to the entire exercise, in analysing a figure whose very purpose was to judge. The fool’s witty antics, exposing human transgressions, were foils to idealised and constructed images in early modern art.

The exhibition also traced the fool’s disappearance during the Enlightenment — an era that sought to suppress irrationality — and his resurgence in the late 18th and 19th centuries, when romanticism and realism revived the figure as a symbol of individual truth and moral complexity. One of the final pieces, a strikingly unique self-portrait by Gustave Courbet, depicts the artist lunging towards the viewer in jester’s clothes. Here, the fool becomes the artist’s alter ego, a figure grappling with inner morality, torment and self-doubt. It was a dramatic and confrontational conclusion to a stimulating exhibition which forced us to turn inward, recognising the foolishness in us all.

Through art, the fool was licensed to dissent. Behind his salacious gestures and frivolousness, the fool exposed the disorder of the world, told new truths, chastised human weaknesses, and said what everyone around him could not. The deeply human themes underscoring this extensive and remarkable exhibition have far outlived the iconography of the fool himself. And yet, the fool still exists today as that traditionally comical, mischievous character we love to look for. He allows us to laugh at the serious, and to confront the serious through laughter. In life, and in art, he persists — emerging in unexpected corners to remind us, ‘it’s not that serious’. It turns out even those somber medievalists had a sense of humour.

By Sophia Jactel

Never miss out on the latest edition of Art & Culture Magazine. Scan the QR code now and fill out the online form to get FREE digital magazines sent to your email in-box!

Art & Culture Magazine are excited to be working on a print subscription service. The paid subscription will be launching soon, and we’ll notify you by email as soon as it’s available.

Scan here to never miss out on the latest edition of Art & Culture Magazine

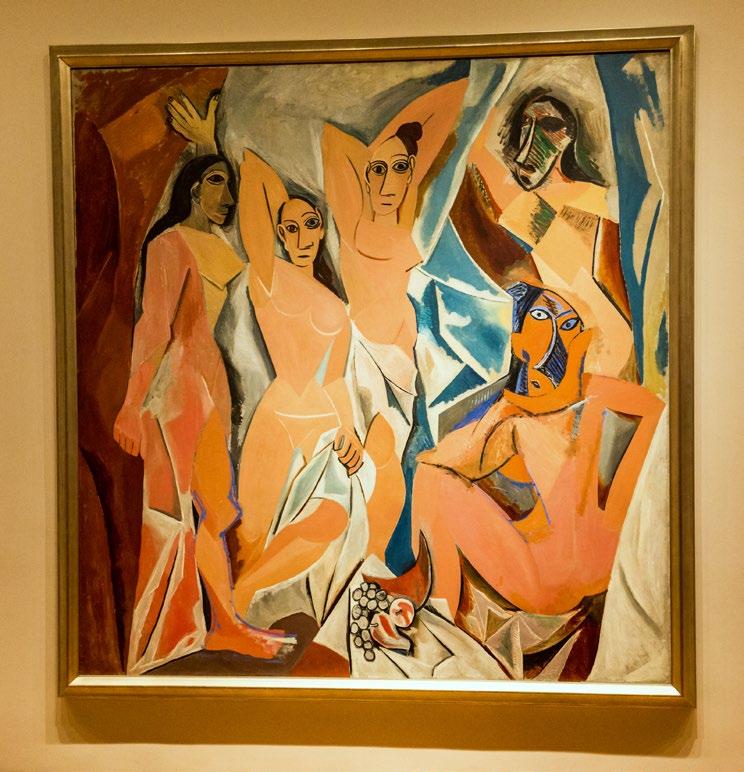

The myth of what constitutes as modernity and ‘modern’ within art, history and various cultural fields can be considered a topic of contention, fluctuating from every era to the next. The field of Art History follows a primarily Western trajectory, often tracing a linear narrative proceeding from the Renaissance to Impressionists on to Abstract Expressionists. Hence, ‘modern’ within art history appears often considered a stop within this linear trajectory.

Within an art history textbook, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon often defines the following quintessentially modern moment. In contrast, modernity remains a term associated with further abstraction. However, with the context of unprecedented socio-cultural and political change, historians tend to deem nineteenth century as a period of modernity.

The traditional trajectory of art history and the modern can be considered centred on primarily Western development, reinforcing the structure whereby the West is the centre and any geography outside the following can be considered a periphery. Through positioning Picasso and his European contemporaries as the peak of artistic innovation, a plethora of global artistic histories appear derivative. Within this, there may be apparent spheres of contradiction where artists such as Gauguin draw inspiration from indigenous forms in varying global centres, however this form of cultural observation refuses to play global artists on par with Western civilisation.

Picasso-Manque

Global artists appear trapped in a double bind pertaining to the category of modern art. Partha Mitter, in reference to twentieth century South Asian artists, describes the ‘Picasso-Manque’ syndrome, where nonWestern artists either appear imitators or failed modernists. If a South Asian artist

utilised modern Western style, an artist was viewed as inherently unoriginal. If an artist expressed independent technique rooted in local tradition, their work was dismissed as lacking skill. Hence, colonial institutions exercised control over the definition of modern art and who may be deemed an innovator or artist.

The following framework negates the complexity and richness of modern artists outside of Europe and North America. Artists working across the globe, from South Asia to Latin America, functioned as more than mere imitators of Western models but rather engaged with modern art and modernity in their own ways, shaped by local histories, politics, and cultural shifts. Within the following context, art symbolised negotiation, resistance, and invention in contexts shaped by colonialism and global exchange.

In order to grapple with the modern as a distinct style, it is necessary to examine a previous colonial era. Within the context of South Asia, academic naturalism appears to be the artistic style primarily associated with colonialism. Partha Mitter describes this as a part of a larger institutional phenomena in the mid-nineteenth century, as part of an ostensible civilisation mission, including the establishment of colonial art schools. At colonial art schools, scientific and objective methods were promoted, prompting a focus

on measurement and precision. Drawing objects from real life or copying Old Master prints accounted for techniques expected to improve artistic tastes.

Raja Ravi Varma can be considered a key artist working within the following colonial framework. Although not a modern artist, Varma works within the environment of modernity, grappling with socio-cultural transformation within society, including the development of steam and print. Colonial art institutions hailed Varma as an artistic master, with him receiving numerous accolades and exhibiting overseas frequently.

Varma can be considered as an expert in terms of European academic realism; however, he utilised the following to depict South Asian mythological scenes. Varma’s usage of oil painting and realism coincides with a colonial framework; however, he displays agency through his adaptation of these tools to local narratives. Varma can also be considered in context of the emergence of a singular artist. His work, disseminated through chromolithographs, reached a large segment of society, cementing his status as an established art figure. However, with the emergence of cultural nationalist currents, Varma’s esteem did not stand the test of time. A new generation of artists within the Bengal

School vehemently criticised Varma’s work for being too Western or imitative, in spite of the integration of local tradition within a colonial framework. The Bengal School tends to be hailed as early modern Indian art, rooted in reflection, revival and anti-colonial imagination. The movement turned towards an indigenous style, as a means to resist colonial dominance. Their aim extended beyond returning to the past, aiming to reimagine tradition contributing to a future national cultural identity.

Homi K Bhabha, famed post-colonial theorist, offers a framework of a ‘third space’ to further analyse cultural interaction in terms of unequal power dynamics. Within this space, meaning continues to be constructed by individuals. In the third space, colonial subjects cannot be negated to simply absorb dominant forms. Local agents shape, reinterpret and transform interactions, which are termed as ‘hybrid’. A hybrid approach aims to provide nuance and further dissect the term modernity. Both terms, modernity and modern, engage with varying constructed

experiences related to history, culture and power, as opposed to being deemed a singular Western export. These terms are malleable chronologically, allowing for a multifaceted interpretation. Through this layered approach, modern art may be both local and global, resistant and transformed. Thus, modernism and modernity, diverge from a singular path, acting rather as a part of a network of entangled, situated and contesting, global processes.

By Malaika Rahimtoola

At first glance, the 1922 Bauhaus exhibition in Calcutta appears at a disjuncture in terms of geography. The monumental exhibition, organised by the Indian Society of Oriental Art, featured works by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, and Johannes Itten. The exhibition acted as one of the first major international showings of the European avant-garde outside the physical realm of Europe.

The exhibition arrived in India shortly after Bengal School founder Rabindranath Tagore’s visit to Germany in 1921, where he garnered the attention of the German intellectual elite. A reciprocal cultural action prompted the two-hundred and fifty Bauhaus works to travel to Calcutta, reflecting a growing affinity between German and Indian modernist circles. This inherently cosmopolitan encounter between two disparate geographies prompts reconsideration of the circulation, interpretation and reshaping of modernism in a non-Western context.

While the transcultural exchange surrounding the 1922 Bauhaus exhibition invites extensive discussion, there remains a scarcity of surviving material evidence to re-imagine the following exhibition in the contemporary. The building that housed the exhibition was demolished in the 1940s, as

noted by Regina Bittner, and the only known exhibition catalogue is preserved in Lahore. No photographs of the exhibition appear to have survived. Crucially, Stella Kramrisch’s detailed article in the Society’s journal Rupam remains a vital primary source, framing the exhibition within the broader context of Indian artists’ search for a cultural identity as they distance themselves from a colonial ideology.

The transcultural encounter reveals deeper ideological overlaps, in a turn toward abstraction, spiritual expression, and primitivism through a shared critique of industrial modernity. The Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar Germany, acted as a bastion of European modernity. Situating this moment within the colonial art environment of India is critical in viewing the intersection between the Bauhaus and Indian artistic circles. The exhibition’s visual

language of abstraction provided a platform for confronting industrial crises of the modern age, as Indians turned away from a rigid colonial art outlook. An intermediary within this transcultural dialogue was Calcutta-based Austrian art historian and professor Stella Kramrisch, who resided at the University of Calcutta. Kramrisch served as a bridge between European modernist circles and Indian intellectuals and artists.

The arrival of the Bauhaus exhibition in Calcutta should be considered as more than a singular cultural event, acting as an emblem of a broader intellectual convergence. In the early twentieth century, Calcutta lost its status as the capital of British India (to Delhi). However, Calcutta remained a vital cultural, artistic, and intellectual hub. The city’s geographical and industrial position allowed for artistic transcultural exchanges. Transculturality remains evident in the work of Bengal School artists Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore, who blended Japanese wash techniques, Mughal miniature styles, and Western artistic perspectives. Calcutta’s status as a cosmopolitan city rife with avant-garde experimentation allowed for the development of hybrid modernisms that sought to define an Indian identity beyond a rigid colonial construct.

“Calcutta’s status as a cosmopolitan city rife with avant-garde experimentation allowed for the development of hybrid modernisms that sought to define an Indian identity beyond a rigid colonial construct.” more....

This moment of convergence reflected a shared ideological opposition to academic naturalism, which acted as a tool of colonial aesthetics. As Partha Mitter argues, both the Bengal School and the European avantgarde perceived themselves as marginalised within their respective political contexts. The aftermath of the First World War and the humiliation relating to Treaty of Versailles left many German artists disillusioned, aligning their critiques with Indian anti-colonial sentiments. The Tagore family, particularly Rabindranath Tagore, emphasised the perceived cultural distance between Germany and Britain as they aimed to turn away from the Empire. German modernism hence resonated with Indian aspirations for a progressive cultural identity untethered to the British. Hence, stylistic rebellion in relation to colonial art techniques and political consequences both acted as factors in prompting increased engagement

with the Bauhaus’ critique of illusionism and embrace of abstraction.

Bauhaus thinkers and Indian aesthetic theorists share a profound philosophical interest in accessing and expressing an inner self. Kandinsky and Klee’s spiritual abstraction, which aimed to convey inner emotional states, paralleled the Indian aesthetic theory of ‘rasa’, which prioritised emotional essence over naturalistic representation. The critique of industrial life and subsequent alienation resonated with early Indian nationalist movements, such as ‘swadeshi’ (self-sufficiency), and Gandhi’s emphasis on village-based craft production as a form of resistance to colonial capitalism.

Calcutta’s role in this transcultural exchange invites a reconsideration of modernism’s geography. While a dominant narrative regarding modernism anchors itself on

centres such as Paris, New York, and London, equally significant networks that include Calcutta, Tehran, and Mexico City. The notion of modernism as an ideology bestowed by the West onto the East should be challenged, as modernism can be considered through the framework of global dialogue, shaped by actors across multiple centres of innovation. Indian artists, intellectuals, and institutions all possess power as local agents, as opposed to passive recipients of European ideas, critically interpreting, engaging and transforming Bauhaus works. This brief intersection of the Bauhaus in Bengal reflects a broader narrative of shared modernities where spiritual abstraction, anti-industrial aesthetics, and design reform unexpectedly converge across continents.

By Malaika Rahimtoola

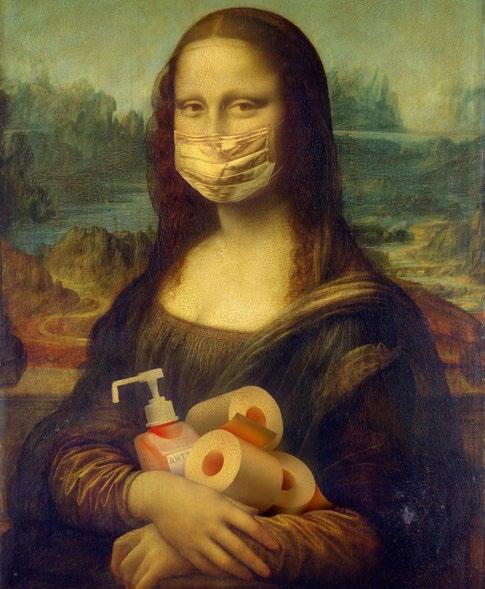

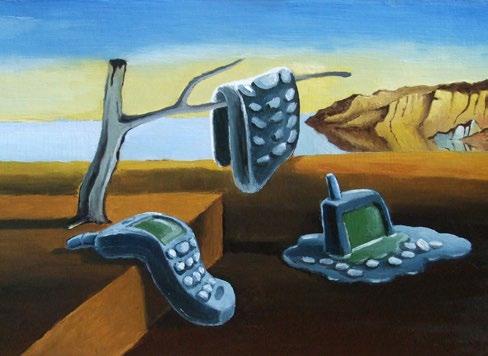

Parody, in its simplest form is mimicry but with a twist. It’s usually an intentional copy of a particular style and reimagines it in a way that’s humorous. Inherently subjective, that’s what makes it all part of the experience.

What might provoke hysterical stomach clenching laughter, may also provoke a bombastic side-eye in another. In this context, these interpretations I feel are supposed to highlight a deeper look into the artist’s wit, charm, intelligence, talent and overall playful mischief. It almost serves as an invitation to re-evaluate the classics with a new pair of eyes.

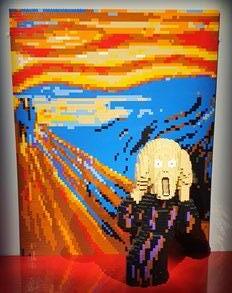

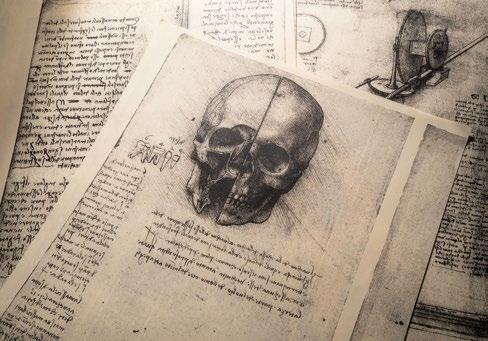

To date, Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has been defaced with a moustache and a goatee, Edward Munch’s The Scream has featured characters from the SpongeBob Square Pants franchise, and Van Gogh’s self-portrait inspired Bert from Sesame Street so much, he even took a painting class himself and gave it his best shot. I was not disappointed; I’d have that framed in my house! If you are ready for a few giggles or ready to give me your best eye-roll, let’s take a look at some of the most parodied artworks of all time.

Kicking off with the main lady herself, the beloved Mona Lisa has been possibly the biggest target for spoofed artworks. Possibly because it’s one of the most recognisable paintings to have ever existed! Her character and her facial expression are shrouded by centuries of mystery, and perhaps the simple composition of the piece makes it easier to alter. Titled Mona Moi, muppet diva Miss Piggy couldn’t resist getting in on the action and is seen holding the same pose and giving that neutral expression from Miss Piggy’s Treasury of Art Masterpieces from the ‘Kermitage Collection’ by Michael K. Frith.

Homer Simpson has had his very own daughter Lisa appear as her in multiple episodes and other promotional images. Finally, who could forget the coronavirus era, where Canada based photo artist Genevieve Blais took to Instagram and made an account called Plague History which saw her recreate famous artworks and characters rocking a face mask in the age of the pandemic. In an interview she stated: ‘we could all use a smile in lieu of recent events, so I decided to update art history for 2020’.

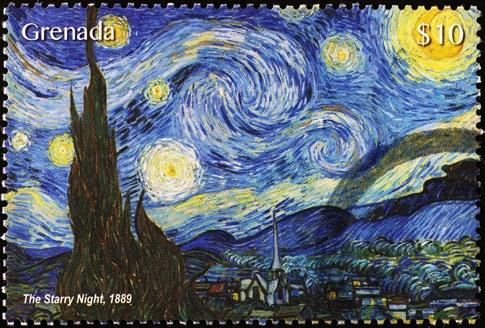

Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night is a beautiful and whimsical piece with both an incredibly heart-breaking and extraordinary background. During a time when his mental health was deteriorating, he found solace and inspiration from the view of his window in the Saint-Paul–de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Remy, southern France. It has since moved and evolved beyond its time. With its swirling skies and magical touch, it’s no surprise that it has been another popular option to reinvent. But, that paints a different question, is it wrong to spoof a painting when it came from a bittersweet struggle? Or do we accept the fun-loving and engaging artwork to keep Van Gogh’s legacy alive and with us, in hopes of keeping him relevant for a new generation of aspiring creatives?

Karen Letchtenberg, as an example has altered the piece ever so slightly by respecting the same brushstroke techniques and colour palette, except, we are graced with a Starry Night at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. I bet she’s a Hufflepuff! KAMonkey has also added more to the original version from a pop culture lens by fusing the iconic sky with the Tardis from Doctor Who. These examples demonstrate how

Grant Wood’s American Gothic is another highly referenced painting that has sparked creativity. Fun fact, the two characters portraying the farmer and his daughter, were posed by Grant’s daughter and his dentist. A bit of an odd family dynamic there, but perhaps that is a reason to poke a little fun at these plain-looking country folk. Was he celebrating them, or satirising them? What was he really trying to say about life in the post-war Depression of the 1930s? A question that has no answers from the artist himself, but a great starting point for artists and their parodies.

Out Magazine updated the original image by replacing the duo with two men who are assumed to reflect the queer community. With the headline stating ‘Love American Style’ in the centre of the cover, this could have been more than just a parody, but instead, a powerful juxtaposition which highlights the contrast between cultural norms and values, and the struggles faced by the LGBTQ+ community.

Political statements aside, the farmer and his daughter have been replaced by cats and minions from the Despicable Me films, and others have seen the gardening fork that’s held in the original image, be replaced with light-sabres, musical instruments, kitchen utensils and all other sorts of apparatus! The Donald Trump ones are also quite wonderful!

In the end, art endures and parody lives on. Why? Because we all like to poke fun and we all have a little sass in our souls. Art parody is not focused on ridicule, but more involvement. These reinventions give them a second life, it can spark how profoundly art can connect across time, culture and identity. So, the next time you see The Last Supper with Ronald MacDonald as the host for a table filled with burgers and fries, or The Creation of Adam featuring Deadpool and Wolverine nearly touching fingers, embrace the sacred becoming the silly. Parody is where the party’s at!

By Anthony Loddo

“Art parody is not focused on ridicule, but more involvement. These reinventions give them a second life, it can spark how profoundly art can connect across time, culture and identity.”

We often think of art as something self-contained. A painting in a frame, a sculpture on a stand, a short film projected on screen and turned off when it’s over. But, the truth is more dynamic: the experience of viewing carries just as much importance as the artwork itself.

The entirety of our encounters with art, from entering the exhibition space to the inevitable ambush of the gift shop, impact how we understand it. Increasingly, museums and curators are attuned to the fact that exhibitions are much more than containers for travelling objects. They build context, becoming active players in shaping public perception of art.

Some exhibitions make this clear in exhilarating ways. Take Keith Haring’s: Art is forEverybody, which ran at The Broad in Los Angeles in 2023. His bold, vibrant, and public-

minded artistic output always had a pulsing energy, and the Broad’s show leaned into it. Neon-coloured walls at the entrance set the stage for the show’s clamorous personality. Inside, chunky black cartoon lines covered entire murals, archival videos played in siderooms, and spaces flowed organically rather than in strict chronological order. Some walls featured windows graffitied with Haring illustrations, allowing glimpses into adjacent galleries. Even the architecture evoked the transparency, collectivity, and imagination so central to Haring’s work, and doubled the message that Haring’s art belongs to everyone, everywhere.

A similar vitality shaped Brasil, Brasil, an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London earlier this year. Celebrating Brazilian art and culture, the show’s masterful use of space created an atmosphere as lively as the works themselves. The rainbow of colours in the modernist paintings extended onto the exhibition walls, painted in warm yellows, pastel pinks, and sage greens. Some works were displayed on backlit panels, making the canvases glow. On the wall texts, giant black serif letters demanded attention and counterbalanced the smaller scale of the surrounding paintings. The viewer’s eye became a zoom camera, broadening the

brightly painted benches in the centres of the rooms continued the visual language of the works. It was a show that embodied the idea of an ‘immersive’ museum experience without the typical technological flair.

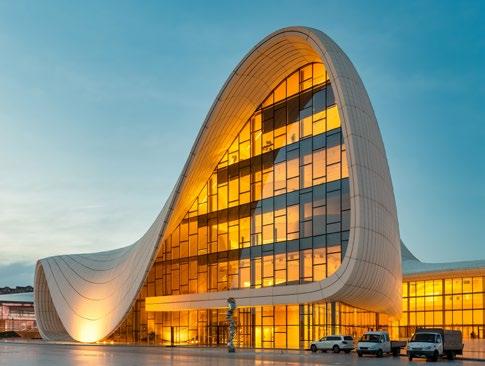

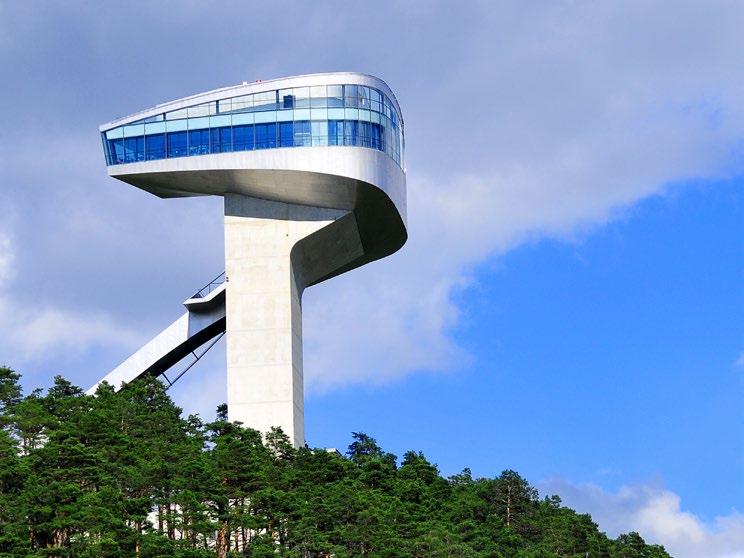

Architecture plays a central role in shaping how we move through art. Nowhere is this more evident than at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, the building’s famous spiral ramp invites continuous movement. Visitors ascend or descend the curve at their own pace. As they move, they see works not in isolation but in dialogue with one another across the rotunda. In that space, bodies constantly pass one another. Some pausing, others moving fluidly. The buzz of human movement echoes through the tower, lending an ever-changing soundtrack to the art on display. It’s a visual flow unlike any other museum. Wright’s voice pierces through the concrete walls, insisting to us that viewing is never static.

Further up north at Dia:Beacon, a converted factory in upstate New York, the experience is entirely different. The museum’s vast industrial spaces are perfectly suited to large-scale contemporary works. Richard Serra’s monumental steel sculptures, for example, inhabit the building like coiled giants. Walking alongside them through a space that echoes their materiality transforms viewing from a latent to an active encounter. Larger than life art like Serra’s is imposing and monolithic. It activates senses beyond sight as it forces you to feel its

weight, its curves, its textures, and listen to its stillness. Across the ocean at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, Monet’s Water Lilies hug the concave walls, illuminated by skylights filtering in natural rays that shift throughout the day. The viewer is subsumed in the watery depths of the Impressionist scenes. In this instance, architecture is designed to fit the art, not the other way around.

When works of art are moved into new architectural spaces, they can reveal fresh meanings. When the Frick collection temporarily moved from its Gilded Age mansion on Fifth Avenue into the brutalist Whitney building on Madison (it has since reopened in its original location), the works entered a whole new dialogue. Opulent Rococo canvases and Old Master paintings clashed with the stark, streamlined interior. Biblical scenes were displayed next to trap-

ezoidal windows. It challenged assumptions about the ‘timelessness’ of art: an El Greco looked surprisingly contemporary in this unexpected setting.

Our sensitivity to experience is especially poignant when we remember that exhibitions are ephemeral. When they’re gone, they’re gone. The momentary constellation of space, viewer, and art disintegrates. In the end, no matter how we walk through an exhibition, we engage in a physical, emotional, and psychological experience. That’s why the act of seeing matters so deeply. Whether we dizzy ourselves in the Guggenheim spiral, have sensory overload in a loud Haring show, feel dwarfed by a Serra sculpture, or lose ourselves in Monet’s Water Lilies, our experiences with art are far from passive.

By Sophia Jactel

The decolonisation of art institutions has often been interpreted as an act of decontextualisation. Tristram Hunt, the director of the V&A, claimed that alongside colonial violence, empire also presented an exchange between cultures and a story of cosmopolitanism – he expressed concern that the history of empire is buried within the V&A’s collections.

However, in his scepticism, he underscores the very point of decolonisation: to include the multitude of narratives that arose during empire in descriptions of pieces and introductions to exhibitions, to give voice to all perspectives. Decolonisation should simply constitute freeing an institution from the cultural effects of colonisation, but also acknowledge colonial pasts in a way that will provide a critical understanding of its implications to the institution’s visitors. Decolonisation is rooted in a dual focus: of acceding the past and righting the future. By accepting responsibility for past wrongs, being aware of complicity in ongoing structures and its contemporary duties to facilitate contact with cultural heritage, institutions have the power to become spaces of transitional justice – where the voices of victims of colonisation are perceived as important and integral to the presentation of art and artefacts.

Carsten Stahn proposes the revision of semantics in the decolonising mission of art institutions. He notes that museum terminology often relies on linguistic concepts that rely on colonial experiences. For example, Native American objects from Africa or Latin America remain labelled as ‘tribal’ artefacts and reproduce developmental myths and cultural inequalities. In this vein, The Belgian Ethical Principles specifically state that labelling practices should be tackled with ‘deepened provenance’ and ‘self-reflexive approaches to the histories of colonialism and racism’. Provenance is deemed essential in the

decolonisation of labels – context is placed at the centre, rather than being taken out of the picture. Historically, the funding and maintenance of art collections have been closely tied to colonial endeavours. Thus, despite growing calls for reform, it must be questioned whether art institutions are truly committed to meaningful decolonisation, even if it means departing from their normative operation.

The British Museum is a notable instance where, despite acknowledging their entanglement with colonialism, there has been hesitancy to repatriate illustrious artefacts, like the Elgin Marbles. While John Keats’s poem On Seeing the Elgin Marbles

expresses a profound connection between the artefact and his ‘spirit (being) too weak – mortality/Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep’ as a commentary on human finitude, the Elgin Marbles now challenge the morality of art collectors in ‘morality (‘s) ’ ethical sense. There have been some positive developments on this front: in 2018 a reported commissioned by the French President Emmanuel Macron recommended the permanent return of looted African art, an effort echoes by the Dutch government in 2022. This led to the return of twenty-six artefacts to Benin. This is, however, but a fraction of the thousands of objects taken from Africa, and more certainly needs to be done.

The interrogation of perspectives and narratives is key in the decolonisation of art institutions, and art curation. For centuries, Western art institutions have shaped frameworks about global art and museums have typically displayed nonWestern art through an ethnographic lens, in a way that presents them as ‘primitive’. For example, the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, which houses thousands of African and Indigenous artefacts, was originally designed to exhibit non-Western objects as part of France’s colonial legacy, rather than as an independent, artistic tradition in themselves. In 2020, the museum revised this and introduced new exhibitions, curated by African artists to reframe African and Indigenous pieces as fine art, as opposed to relics of colonised cultures.