afroi Va N

A história de arte urbana, nos bairros periféricos de Maputo, nasce como uma reacção controversa às constantes disputas pelos espaços convencio nais de exibição e valorização da produção artística nacional, neste caso as galerias e os espaços culturais estrangeiros que se encontram con centrados no circuito do bairro central. Estes, por tradição moderna, pra ticam a discriminação que consequentemente desvaloriza a arte de rua classificando-a como um acto de vandalismo. O termo “vandalismo” ficou em uso depois da Revolução Francesa, no final do século XVIII, quando se começou a associar o substantivo “vândalos” à destruição motivada pelas refregas sociais, como sugere o livro de Stephen Kershaw, “Os Ini migos de Roma: A Bárbara Rebelião contra o Império Romano” (2020).

Maputo, como uma pequena urbe de raízes coloniais, logicamente que se ergueu alicerçada em leis de controle, segregação e proibição de uso do espaço público. Por outro lado, ao arrepio dessas normas o facto da única escola artística vocacionada para o ensino das artes visuais (desde 1983 até 2010, quando foi transferida para a periferia da cidade), a Escola Nacional de Artes Visuais se localizar no centro da baixa da cidade de Maputo, acabou por contribuir, de forma indubitável, para a massifi cação de um tipo de cultura que se confinava a espaços fechados, tanto em institucionais (museus e galerias) como nos atelieres dos artistas.

Os primórdios dos anos 2000 marcam o rejuvenescimento de vários interesses no contexto da arte urbana, após a decadência dos murais revolucionários que representaram com vivacidade o cenário pós- inde pendência nacional. É nesse período que surgem múltiplas interven ções multidisciplinares como as de David Bonzo, o desenho gráfico, o vídeo, a poesia e ritmos do hip-hop; que se desenvolve a música ligeira em geral, e emerge a cultura rastafári que também foi muito expres siva na dinamização das acções artísticas, no espaço urbano.

As obras de arte pública comissionadas em espaços nobres da cidade, da assinatura de artistas consagrados como Malangatana, Naguib ou Titos

15

Mabota, entre outros, criaram um impacto positivo e francamente estimula ram a imaginação no seio dos estudantes das artes visuais, os quais, na sua maioria, enfrentavam manifestas dificuldades de sobrevivência económica. Por outro lado, os condicionalismos sociais que sofriam terão impulsionado entre eles o desejo de um espírito de recompensa com garantias imediatas, hipótese que se gorou, e, sentindo-se discriminados, cresceu assim o des carte ou afastamento mais uma vez do espírito voluntário ou do artivismo que norteia a prática da arte pública. Por conseguinte, virá daí que as poucas intervenções públicas existentes na cidade sejam fruto de ocupações vali dadas/comissionadas pelos grupos da elite económica e social da cidade.

A prática de arte pública no contexto urbano de Maputo foi sempre de carácter comissionada por instituições governamentais; mais tarde, par ticularmente, a partir dos anos 2000 ampliou-se o palco para a intervenção dos artistas, com as comissões de arte publicitária, de painéis, ou de murais gigantes. Houve assim lugar para os primeiros contactos da comunidade com murais em espaços públicos por via de comissões, e enquadrados ora por contextos temáticos que visavam a educação, ora por campanhas políticas ou publicitárias, para reclame a produtos de consumo diário. Estes são os murais que mais se multiplicaram depois daqueles da revolução, quando mais empresas privadas apareceram e as demandas de murais ganharam mercado, ainda que com objectivos unicamente comerciais, não contri buindo para um ponto de vista de mudança de comportamento, de sã pro vocação às mentalidades instaladas ou para a representatividade cultural.

A arte urbana em Maputo ganha um novo contorno quando artistas independentes, contrariando as suas grandes dificuldades económicas e o difícil acesso às montras das galerias que poderiam reverter em ganhos económicos o fruto do seu trabalho, galvanizados pela sua paixão pelas artes, começam a pintar nas paredes dos seus próprios bairros. Eu sou um desses artistas que em 2012 começa pintando dentro do Bairro Uni dade 7, onde nasci e cresci, procurando expressar a sensibilidade da comu nidade que me rodeava e a influência da música tradicional que me rodeava (depois da independência, em particular por volta de 1980/90, vindos de Gaza e Inhambane, o grupo de dança de Ngalanga1 -dança tra dicional do sul de Moçambique - com bailarinos, e tocadores de timbilas

1 Ngalanga é uma dança tradicional muito comum no sul Mocambicana acompanhada por uma orques tra de batuques e timbileiros, praticada pelas tribos bantu, como forma de preparação militar, celebração vitoriosa, esta dança revelava um caracter acentuadamente social, constituindo um factor de relevo, para a manutenção da unidade tribal e para afirmação da lealdade comum dos seus membros ao respectivo chefe.

16

instalarou-se neste Bairro, o mesmo grupo que viria a inspirar a criação de grupos de igual género musical nos bairros de Hulene e Polana Caniço).

Na contemporaneidade, a arte urbana, sobretudo no domínio dos murais, tem obtido um crescente reconhecimento social e visibilidade através do tra balho inegável de artistas como Shot-B, Mavec, Villa Terry, Mateus Sithole, Kassiano, Djinafita, e de outros que apareceram na nova vaga, após 2016; sendo hoje claro que a arte de rua independente se foi tornando mais digna de realce à medida que mais murais despontavam nos bairros de Maxa quene, Polana Caniço e Magoanine, e ficava patente a sua riqueza expressiva e invenção, aproximando assim mais as pessoas comuns e os artistas no seio das comunidades, que sentiam coloridos e embelezados os espaços urbanos - mesmo que sem garantia de permanência das obras, uma vez que tantas vezes as paredes são derrubadas, são repintadas para novas paisagens, sendo as assinaturas removidas, para além da erosão e do desgaste ligados aos pró prios elementos da natureza, o sol, a chuva, o vento, que amolecem a pigmen tação das tintas e consequentemente vão destruindo gradualmente os murais.

É neste estado das coisas que se torna fundamental o papel da foto (afinal, uma pioneira arte urbana, que a partir do início do século XIX se torna o grande arquivo de toda a vida moderna) e que, entre nós, se dá o cruzamento da arte urbana com a fotografia, através da lente do Ilde fonso Colaço, artista que também explora muito o espírito de criatividade independente no contexto de arte urbana, dignificando com o seu tra balho o espaço onde vive, registando, criando memória e longevidade à existência não só de murais mas também de muitos mais elemen tos que representam a presença humana na paisagem periférica.

Igualmente, a performance tem ganhado aí novos palcos, quando estu dantes de teatro e cinema se juntam com o mesmo empenho expres sivo e a necessidade de se fazerem reconhecer dentro do espaço onde crescem e estabelecem as rotinas do seu quotidiano.

Pequeno aparte para lembrar que o individualismo é também uma rea lidade emergente no espaço cultural Moçambicano, à semelhança do que se passa no mundo, o que recentemente se tem reflectido na crescente e interessante participação de artistas femininas, que aos poucos também tentam romper a clausura da criação ensimesmada para outras experiências a céu aberto, mais sociais, onde a interacção com os espectadores é mais espontânea; os quais são na sua maioria residentes e outros trânsfugas.

17

Em Maputo, a liberdade de querer intervir na paisagem urbana, de a trans formar, é muito vincada e não é inferior à demanda de querer ver o seu traba lho artístico representado por galerias. Neste sentido, os investimentos pró prios são a primeira manifestação de quem sonha, e hoje com o fortalecimento das redes sociais, multiplicam-se os encontros e as interacções entre criativos formados em escolas técnicas e universidades com os muitos autodidatas que são atentos à necessidade de profissionalizar as suas habilidades e poten cializar-se no contexto de Artes Visuais, garantindo assim a continuação das sua actividade no meio cada vez mais exigente das manifestações culturais.

A presença recente e marcante de arte urbana nos bairros periféri cos de Maputo representa deste modo a materialização dessa liberdade de expressão e a possibilidade de transformação de espaços descarta dos em galerias abertas, com a agregação de valor eminentemente his tórico que advém de uma mais imediata e uma maior sintonia com os diferentes temas que envolvem directamente os residentes em tempo e espaço real; assim como a relação entre o artista e o público não con vencional é mais profunda e extractiva, devido à curiosidade pública de quem assiste à execução da obra “ao vivo”: um dos pontos que acho mais importantes quando se está a fazer arte urbana e que, a meu ver, enriquece os propósitos mais diversos para a criação da obra, sejam os seus objectivos os de simples divertimento, querendo apenas contar histórias, ou os de educar, de divertir ou de influenciar mudanças de com portamento em comunidades sem muito privilégio económico.

Esta publicação que, de entre vários colaboradores, conta com a con tribuição dos créditos fotográficos do Ildefonso Colaço e textos de Titos Pelembe (que também é artista plástico) pretende afirmar-se como salva guarda, registo e testemunho duma fase histórica da arte urbana contem porânea em Maputo, que por uma vez, estabelece modelos e desafios para o uso de espaço urbano, e incita à requalificação visual e cultural da comu nidade urbana, a partir da periferia para os bairros nobres. Que este raro vice-versa se torne trampolim para um maior diálogo é o nosso desejo.

Para além disso, a diversidade criativa, a qualidade de outras abor dagens e técnicas, o mapeamento de arte urbana em murais dentro e fora da cidade, justificam a importância deste material de con sulta para estudantes e interessados sobre arte em espaços públicos, com as suas diferenças em aplicação, concepção e prática. Os artis tas que estão nesta e outras disciplinas que difundem várias expressões de arte urbana, seja voluntária como inconscientemente, agradecem.

18

Passado e PreseNte

As manifestações artísticas praticadas e disponíveis no espaço público remotam aos primórdios das antigas civilizações humanas; as pinturas rupestres constituem umas das evi dências. Geralmente o trabalho artístico, nas suas variadas expressões, acompanha o progresso tecnologógico e sócio -político do homem. Razão pela qual, na contemporanei dade, vários estudos se debruçam em torno do advento e dos conceitos de ‘arte urbana’ ou ‘arte pública’. E, particular mente em Moçambique, a prática de arte urbana ou da arte no espaço público tem igualmente as suas origens nas tradi ções mais antigas. Nesta perspectiva, interessa-nos situar a arte urbana a partir de dois contextos bipolares, especificamente no periódo colonial e no pós revolução, desde 1975 até agora.

Alguns trabalhos artísticos produzidos na era colonial, de natu reza muralista ou na estatuária, pretendiam ser marcas distintivas do poder colonial português e foram localizados em determinados espaços edificados de enorme importância social. Assim, algumas dessas criações plásticas enriquecem actualmente a paisagem arquitectónica e urbanística da cidade. Dentre várias obras, des tacam-se: o mural de cerâmica policromada de autoria do artista plástico português Querubim Lapa (1925-2016), instalado na fachada do antigo edifício do Banco de Moçambique (descen dente da Sede do Banco Nacional Ultramarino); o Monumento em Homenagem aos Combatentes Europeus e Africanos da 1ª Grande Guerra Mundial (1931), de autoria do escultor Rui Roque Gameiro (1906-1936), exposto na actual Praça dos Trabalha dores; entre outros trabalhos, refiram-se ainda: dois grandes painéis de esculturas em bronze, da autoria do escultor Antó nio Duartes, e um médio, em mármore, não identificado, execu tados em técnica de alto e baixo relevo, embutidos na fachada do edifício da Rádio Moçambique. Para além, das várias interven ções artísticas de natureza arquitectónica da autoria do célebre arquitecto Pancho Guedes e disponíveis nas fachadas e empenas de alguns dos seus emblemáticos edificios situados ao longo da cidade, ou o painel de António Quadros na filial do Mille nium BIM, na esquina da 24 de Julho com a Salvador Allende.

21

E ao longo dos alvoroçados momentos de revolução pós independência (1975), que culminou com a destituição dos símbolos de poder e da soberania colonial, outros trabalhos sobretudo da estatuária monumental foram destruidos, e alguns retirados dos locais públicos onde estavam implantados. Tal como aconteceu, por exemplo, com a remoção da estátua de Mouzinho de Albuquerque na praça que ostentava o mesmo nome, actual praça da independência, onde se ergue actualmente a imponente estátua do primeiro presidente de Moçambique –independente, Samora Moisés Machel (n.1933-1986).

22

23

o

PaPel

dos Murais No Processo de reVolução cultural

O segundo momento, pós-colonial, vinculado pela celebra ção da independência nacional em 1975, deu-se naturalmente nos anos subsequentes e foi marcado pela ressurgência de acti vidades artísticas de carácter popular, as quais podem ser lidas a partir das lentes conceptuais da arte urbana. Essas manifes tações enquadravam-se nas acções associadas à revolução nacional, tendo em conta a potencialização da ofensiva cultural das classes trabalhadoras que, entre várias questões, instigava a consciência crítica sobre os horrores do colonialismo e por conseguinte cultivava a consolidação dos valores nacionalistas.

Diversas festividades públicas tiveram então lugar ao longo do país; sublinhem-se os seguintes acontecimentos: Exposi ção de Arte Popular (1975), Reunião Nacional da Cultura (1977) e o I° Festival Nacional de Dança Popular (1978), que juntou, “pela primeira vez, danças de todo o país” (Costa, 2013:261). Daí que muitas obras hajam sido executadas preferencialmente em locais públicos, às vezes por iniciativa dos próprios artis tas, outras por meio de comissões institucionais. O grandioso mural da Praça dos Heróis Moçambicanos, pintado em 1979, com assinatura do artista João Craveirinha, sobrinho do reno mado poeta José Craveirinha resultou desta dinâmica. Esta mag nífica obra, para além de retratar os distintos períodos da história recente do país, contribuiu inclusive no processo de dissemina ção do pensamento revolucionário através das artes plásticas.

Várias outras expressões artísticas, como a Escultura, o Dese nho, a Pintura, a Instalação, a Assemblagem e o baixo-relevo, foram palco e continuam sendo exploradas como manifestações da arte ao serviço da revolução; projectando-se a pintura como uma das técnicas artísticas de eleição. Naturalmente que esta conheceu mutações, ao longo do tempo, pelos diferentes protago nistas inter-geracionais que compõem o tecido artístico nacional. A preferência pela pintura em detrimento das restantes disciplinas talvez se deva à longa tradição que a antecede e ao facto de ser uma técnica ligada a materiais mais baratos e de execução simples sobre qualquer género de superfície. Por outro lado, talvez seja motivada pela facilidade de manuseamento, aquisição e adapta ção dos materiais, em comparação com as demais disciplinas.

25

Contudo, os anos 80 e 90 terão sido significativamente mar cados pela presença de manifestações artísticas no espaço urbano, no caso particular dos murais carregadas de forte sim bolismo nacionalista, como vestígios dos sonhos de (re)construir o “homem novo” e a nação moçambicana, conforme se docu menta no livro “Imagens de Uma Revolução” (1984), da autoria do jurista e activista dos direitos humanos sul-africano Albie Sachs.

A cultura foi um dos meios utilizados para fomentar a coesão social; para o efeito, “a direcção Nacional de Cul tura foi o instrumento de execução das políticas então defini das”. A mesma visou “valorizar a cultura moçambicana, criar uma cultura revolucionária e popular que traduzisse as vivên cias do Povo no processo de transformação da sociedade –combatendo a cultura da burguesia…” (Costa, 2013-248).

Ao longo deste período, recrudesceram as acções no âmbito da pintura de murais, da criação de cartazes, de banda dese nhada, de caricaturas e paredes informativas, designadas como jornais-do-povo. Diferentes activistas sociais, artis tas profissionais, principiantes e populares contribuiram na materialização destas acções. Todo este conjunto de inter venientes desempenharam e continuam a jogar um papel de extrema relevância no âmbito da revolução, por conse guinte na formação da nova sociedade moçambicana.

Artistas como Malagantana, Mankew, Noel Langa, e Shikhane intervieram na época de diferentes formas, produzindo murais comissionados e não só ao longo do país, com des taque para os trabalhos realizados nas cidades de Maputo, Beira e Tete. Por exemplo, Malangatana pintou entre 1977 e 1979 o mural intitulado “O Homem e a Natureza”, loca lizado no exterior do Museu de História Natural.

26

28

Naguib, “Ode a Samora Machel”, 2006-2007

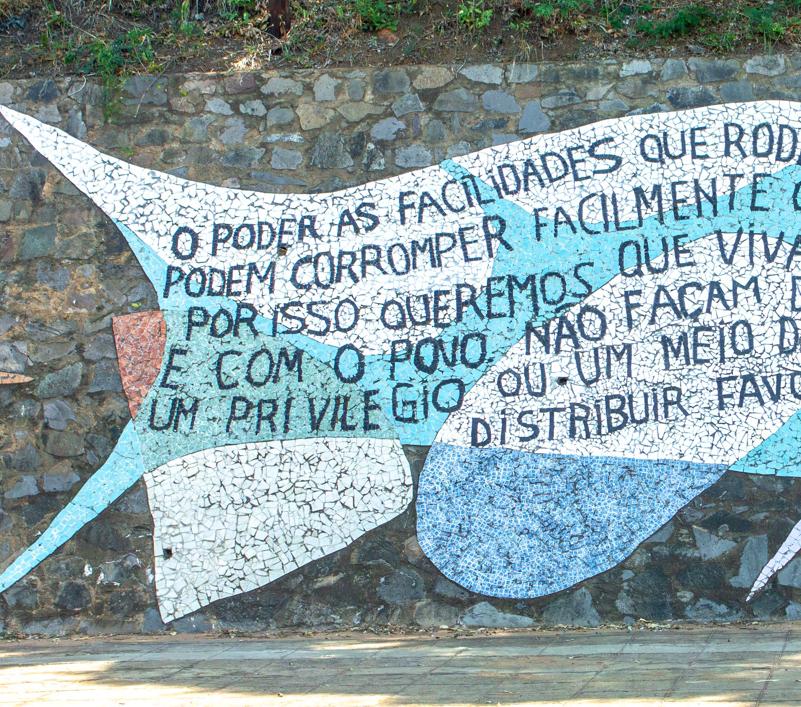

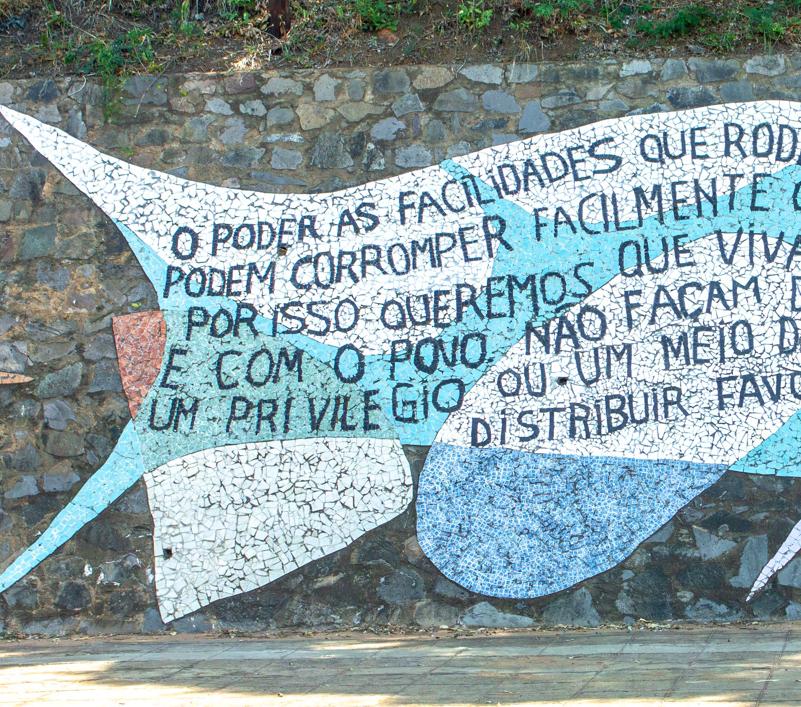

Actualmente, a intervenção do multifacetado Naguib, com a sua consequente prática artística urbana, merece uma aten ção especial, devido à sua inovação na aplicação de suportes e técnicas que localmente são novas, ou patentemente pouco exploradas tais como o mosaico e a combinação de vários materiais. Ligado à geração de 60, Naguib tem vindo a dinami zar a arte urbana desde 2006, através da criação de extensos murais com recurso a mosaico. Os seus trabalhos emblemáticos foram produzidos em diversos locais de destaque nas cidade de Maputo e na Vila de Songo, província de Tete, perto das instalações Centrais da Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa.

Contudo, para além dos acontecimentos e intervenien tes nomeados, surgiram na contemporaneidade novos protagonistas, continuadores da arte urbana, primordial mente por meio do grafite, street art e muralismo. Estes, pelo seu turno, dedicam-se particularmente à revalo rização de áreas marginalizadas, arruinadas, situadas sobretudo na periferia, para além do uso de espaços localizados no centro urbano da cidade de Maputo.

A par destes acontecimentos, compreenda-se que as artes tendem a acompanhar o desenvolvimento social das nações ou simplesmente das comunidades. No caso particular de Moçambique, os anos 90 foram caracterizadas por inten sas actividades artísticas, e citemos: a realização do primeiro workshop internacional de artes plásticas, decorrido em 1991 no Núcleo de Arte sobre organização da artista Fátima Ferna des (Costa, 2013:347), entre outros eventos que posteriormente se seguiram, especificamente: Ujamaa I, II e IV. Por um lado, esta abertura derivou das várias transformações sócio-polí ticas e económicas que marcaram a conjuntura local, regio nal e global. Importa referir que, entretanto, a nível político se assistiu à implementação da nova Constituição da República (1990), fruto das negociações que lograram acabar com a guerra civil entre os partidos: Renamo e Frelimo, em reac ção a este movimento ter assumido o papel de partido único, num regime monopartidário. A guerra fustigou o desenvol vimento do país desde o seu início em 1977, até ao aparente momento de apaziguamento que culminou com a assinatura

29 PreseNte

dos primeiros Acordos Gerais de Paz (Roma-1992); com o fim das hostilidades militares entre os irmãos moçambicanos introduziu-se o multipartidarismo, que pôde manifestar-se na realização das primeiras eleições gerais de 1994. Simulta neamente, a nível regional e global aponte-se, dentre vários acontecimentos, o fim do regime de apharteid na África do Sul.

Corolariamente, nessa altura abriu-se espaço para uma maior circulação dos artistas e houve abertura para a participação de artistas moçambicanos em eventos internacionais tais como: residências, bienais, workshops e exposições. Daí que vários jovens artistas moçambica nos maioritariamente em formação na época, ou recém -formados pela Escola Nacional de Artes Visuais, tiveram

30

2006-2007

Naguib. “Ode a Samora Machel”,

a oportunidade e beneficiaram de workshops e do desfrute de outro tipo de exposições, local e internacionalmente.

Paralelamente, alguns fazedores culturais anónimos, nas cidos nos anos 70 e 80, sucessores da cultura revolucionária do movimento Hip hop moçambicano são apontados como pioneiros da pintura de rua em técnica de grafite e pichagens. Os artistas que estão ainda activos na cena de arte urbana, nomeadamente: Shot B (Bruno Mateus), Afroivan (António Ivan Muhambe) e Bruno Chichava, entre outros de não menor relevo, são alguns actores formados pela Escola Nacional de Artes. Coincidentemente, os artistas urbanos mencionados foram infuenciados, nas suas actuações e criações, de forma

31

significativa pela cultura do Hip hop nacional e internacional e alguns são mesmo figuras do próprio movimento do Hip hop.

Outrossim, junte-se a este grupo de artistas multidisci plinares e grafiteiros mencionados, outros criativos emer gentes notáveis: Kassiano, Djinafita, Sebastião Coana, Mateus Sithole, Barimu, Doglas, Djive Make Studio, Amino e Chaná de Sá que, recentemente, têm desenvolvidos traba lhos consideravéis no contexto de arte urbana das cidades de Maputo e Inhambane. O trabalho destes criativos desen volve-se num espectro amplo, que compreende interven ções de carácter efémero, performativo e permanentes.

32

uM olhar sobre as NarratiVas teMáticas PreseNtes Na arte urbaNa

Urge por isso a necessidade de retratar a realidade actual e his tórica do país e do mundo a partir da visão singular dos artistas urbanos, bem como da construção de uma identidade visual autó noma e distante das agendas partidárias politicamente dominan tes; o desiderato da divulgação do seu trabalho constitui um dos principais desafios que este grupo de profissionais enfrenta.

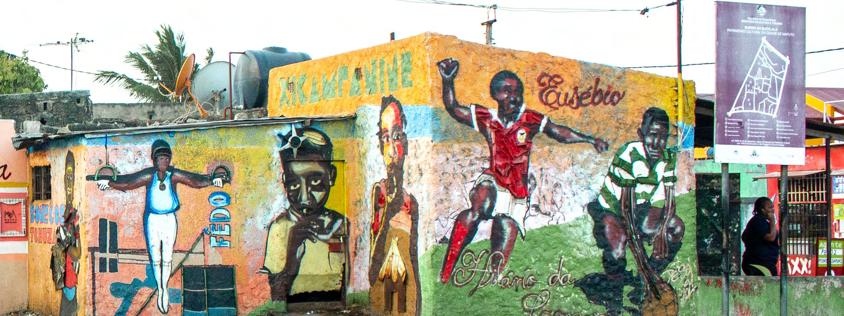

Daí que parte considerável das obras que integram a arte urbana da cidade procure reflectir sobre a realidade actual, como meio de enaltecer os diversos aspectos culturais, sócio -políticos e as figuras nacionais intrinsecamente ligadas ao pro cesso de revolução nacionalista e de desenvolvimento do país.

Os murais dos artistas: Shot B, Francisco Vilankulos, Kassiano, Chaná de Sá e Mateus Sithole, entre outros, recorrentemente revisitam as memórias colectivas do passado e do presente.

Enquanto os trabalhos de Afroivan, Djinafita, Sebas tião Coana, Samuel Djive, geralmente dentro da visão ante rior, propõem uma aventura criativa em torno do imaginário urbano, onde a fantasia, o mito e o retrato social contempo râneo enraizado na identidade africana é evocado constante mente; esta narrativa, re-centrada pelo afrocentrismo, encon tra também espaço nos murais colaborativos produzidos pelos artistas e colectivos internacionais (Jonathan Darby , Andy Leuenberger, Zallicus Alice Zaniboni e Boa Mistura).

Os trabalhos dos consagrados e reconhecidos artistas moçam bicanos (Naguib e Titos Mabota), também não são excepção e cruzam diferentes abordagens. Por exemplo, o extenso mural de mosaico de autoria de Naguib “Ode a Samora Machel” (2007), aborda igualmente as questões temáticas evocadas, bem como objetiva contribuir significativamente no melhoramento da qua lidade visual do espaço urbano em que se insere. E a escultura de Mabota, comissionada pela empresa pública de telefonia móvel, actual TMCEL, por seu turno, enaltece a massificação e o desenvolvimento da rede de telefonia móvel moçambi cana junto das populações, situadas no interior do país. Shot B. “Let my people go”, 2022.

33

a MultidisciPliNaridade e iNforMalidade da arte urbaNa

Quer o conceito de espaço urbano quer o do espaço público aludem a uma mutualidade de interesses e de uso comum, razão pela qual a arte urbana ou pública também con corre para um bem comum, dado funcionar como canal para uma livre fruição artística; para a regeneração de espaços maltratados e melhoramento da qualidade visual do espaço comum; para a educação cultural e muito mais.

Em anuência com a presente reflexão anterior, pode mos situar melhor, nesta perspectiva, o enquadramento das obras efémeras expostas no espaço público perten centes ao artista Kassiano, as quais de certo modo incor poram a dimensão performativa, que se denota no próprio facto do mesmo percorrer distintos pontos da cidade no final do dia e início da noite para pessoalmente fixar os seus tra balhos em locais previamente escolhidos ou aleatórios.

34

Estes trabalhos integram retratos de várias figuras famosas ou anónimas, colocados sobre papel ou papelão, e são expostos na rua, em vários suportes urbanos tais como: postes de ilumina ção pública, muros de vedação, fachadas de edificios e também nos troncos das árvores. Esta estratégia expositiva é igualmente explorada pelo Afroivan com o aproveitamento do mobiliário urbano do centro da cidade, através das acções de “pincha mento” espontâneo de vários conteúdos sobre estes materiais.

A partir dos conceitos partilhados pelo investigador e professor José Guilherme Abreu (2015), compreende-se que a conceptua lização da arte pública é multidisciplinar, e muito mais abragente do que as simples expressões recorrentes como o muralismo, e que nela se exploram técnicas de grafite, pintura, mosaico, assembleagem, instalações, esculturas, etc. Por exemplo, incor poram-se também, no contexto de arte urbana, os animado res ocasionais de rua que se expressam comumente através da música, dança, teatro e artes performativas no geral. Assim sendo, é comum nas ruas, avenidas, mercados e espaços de lazer da cidade de Maputo presenciar alguns momentos de anima ção de rua protagonizados por diferentes grupos; nomeemos, dentre os mais notavéis, W Tofo Tofo, Robotizzy Shonguile Arte, incluíndo os “madalas” (homens adultos), trovadores anónimos que actuam geralmente no mer cado do povo, de modo ambulante.

Conclui-se também que a arte pública pode assumir qualquer meio, material ou forma de apre sentação, desde que esteja virada para o consumo das massas populares, no cenáculo urbano. Por isso, geralmente os artistas que actuam neste campo acabam desempenhando funções e atitudes de activismo, usando a arte como forma de protesto e contraponto social das comunidades, como por exemplo as acções artísti cas desenvolvidas pelo projecto “Maputo street art, Bring Back Maputo”, entre outras iniciativas.

35

Mateus Sithole. “O sonho Muda o Mundo”, 2020

coNteMPorâNeos

O início do presente século (XXI) conheceu novas realidades no domínio da arte produzida no espaço urbano, face aos inúmeros desafios da nova ordem social, política e económica do país, mas também fruto de novas práticas impulsionadas quer pelo contexto local, bem como regional e internacional, visto que com o fim da guerra civil em 1992 o país abriu-se mais para o resto do mundo. As artes, no geral, não ficaram alheias às novas mudanças, tendo surgido novos protagonistas aspi rantes a artistas, nascidos ao longo dos anos 80, alguns dos quais obtiveram formação artística a partir de 2000 nos distintos cursos e níveis de especialização ministrados pela Escola Nacional de Artes Visuais - ENAV.

Como resultado da coesão e intersecção social dos demais acon tecimentos, o discurso artístico começou a descolar dos espa ços institucionalizados das galerias e museus. Algumas inicia tivas, entre workshops e exposições organizadas pela ENAV em parceria com artistas e organizações internacionais, tive ram lugar especificamente nas ruas de Maputo. “Ocupações Temporárias” foi um dos projectos do início da segunda década do presente século, entre 2011- 2013, sob a produ ção e coordenação da curadora portuguesa Elisa Santos. Shot B e o rapper Azagaias são os dois artistas urbanos moçambicanos que integraram o mesmo projecto.

Localmente, inúmeras obras de carácter público, sobretudo corporativas, vêm sendo desenvolvi das no espaço urbano. Dentre as muitas interven ções de carácter institucional, importa desta car as mais recentes, especificamente a pintura colectiva do mural da EDM (2017); a fachada do edifício do Hospital Central de Maputo, ambas da autoria de professores e alunos da Escola Nacional de Artes Visuais e também a requalificação da “Praça dos Combatentes”, bem como o “Monumento em Homena gem à Organização da Mulher Moçambi cana – OMM , do artista Naguib e a está tua de Filipe Samuel Magaia, só para citar algumas.

36

NoVos desdobraMeNtos

Paralelamente, também várias outras intervenções, propostas pelos próprios artistas, têm tido lugar em diferentes lugares descentralizados da cidade, particularmente em espaços públicos marginalizados, tanto no centro, como nos bairros periféricos, obras que mais adiante apresentaremos. Em parte, este movi mento, cada vez mais importante, é massificado através do projecto Maputo street art, que integra um número significativo de jovens interessados pela arte urbana nomeadamente: Afroivan, Kassiano, Djinafita, Manaven tane, Matheus Sithole, Ildafonso Colasso, Phayra Baloi, Amarildo Rungo e outros mais. Destacamos estes, sem tender de forma alguma ignorar o trabalho de outros artis tas que os precederam nesta iniciativa, mas que actuaram individualmente.

Mas importa relembrar que, muito antes da existência jecto Maputo street art, como tem sido referenciado, nio da arte urbana a cidade de Maputo conheceu uma lenta, instável, marginal mas progressiva da arte fora oficiais das exposições. Novas obras foram executadas planificada, espontânea e híbrida em locais marginalizados ou desactivados da cidade. Foram introduzidas, de novas técnicas e também novos materiais de pintura como da tinta spray em lata com que são pintados os Jovens artistas como Shot B, Mavec, dentre outros, nomes que se destacam a partir dos anos 2000. Shot B, da sua carreira enquanto grafiteiro e rapper nos tem intervindo recorrentemente no espaço urbano formas, tanto a partir de trabalhos concessionados mente, como por exemplo o extenso mural pintado da OUA, entre 2010 e 2012 (infelizmente parte significativa dste trabalho já não existe foi apagado, devido a censura ou repressão social entre outros executados em diferentes pontos entre ria, de onde se destaca o recente mural “Let My People Go” tando no interior do bairro da Mafalala. Shot B também colaborou na produção do emblemático mural situado na parede exterior junto ao Porto de Maputo. Este trabalho resulta de o artista e o Fraime 1. O mural em alusão visa imortalizar figuras que contribuíram para o desenvolvimento das bicanas, nomeadamente: Alberto Chissano, Noémia nha, Malangatana, e Fany Mpfumo.

É de capital importância evidenciar o progresso e a massifica ção gradual de outras técnicas, tais como o alto, o baixo-relevo e o mosaico no panorama do desenvolvimento da arte pública em Moçambique. Esta última técnica ganhou novos contornos no ambiente artístico da capital do país, inspirada nos murais do multifacetado artista Naguib, por volta dos anos 2006. Neste âmbito, dentre as muitas obras, destaca-se a produção do reco nhecido mural “Ode a Samora Machel” (2007), com cerca de 700 metros, executado nas famosas barreiras do museu, no prolonga mento da avenida Marginal em Maputo. Actualmente, a técnica do mosaico tem sido seguida por outros artistas emergentes, nomeadamente por Samuel Arão Djive autor do mural produzido na fachada da embaixada da Tailândia, no prolongamento da ave nida Julius Nyerere e por Marcelino Manhuma, mentor do mural produzido intalações da Federação Nacional de Futebol.

Afroivan + Andy Leuenberger. “Mercadorias Ocultas”, 2022

38

asceNsão dos Murais coMerciais (2000 – 2010)

Certamente o novo ambiente socioeconómico e cultural posterior à rea lização das primeiras eleições multipartidárias (1994), e consequente adesão ao sistema financeiro internacional, ou seja, à chamada “econo mia de mercado”, tornou Moçambique apetecível para o investimento externo privado. A entrada do financiamento internacional (in)directamente pode ter ditado, de igual modo, as novas directrizes do discurso artís tico, fazendo com que a visão anteriormente dominante inerente ao papel das artes ao serviço da revolução desacelerasse progressivamente a favor do advento de novos tipos de murais comerciais que rapidamente inunda ram as ruas, avenidas e os principais espaços públicos atractivos da cidade. A corrida pela ocupação do espaço urbano colocou as grandes empresas multinacionais em competição e, por conseguinte, os poucos murais essen cialmente artísticos que se encontravam em zonas desprotegidas foram gradualmente desaparecendo do ambiente urbano a favor dos murais comerciais. Como prova disso os murais pintados pelo colectivo de artistas membros da Associação Cultura Achufre foram praticamente todos des truídos. Deste modo, a paisagem urbana foi sendo cada vez mais impreg nada por conteúdos comerciais, o que se mantém até aos dias de hoje.

O artista e professor de artes visuais, Tembo Sina nhal (2016), argumenta, em torno desta problemática:

Observa-se um crescente número de painéis e cartazes em paredes e muros, outdoors em Maputo e Matola, assim como pinturas murais que abordam temas comerciais, publicidades de bens e serviços. Estes painéis monopolizam o espaço público e os espaços são usados como campos de batalhas de marketing, promovendo o consumismo, uma das estratégias do capitalismo. (2016:7).

39

”

“

Em concordância com os argumentos do Sinanhal, a reali dade descrita está patente na área das duas cidades (Maputo e Matola), pese embora por um lado este fenómeno também ter conhecido uma redução significativa nos últimos anos, devido a factores diversos. A evolução das plataformas tecnológicas de comunicação e consequente digitalização de serviços pode ser apontada como uma das razões por detrás desta mudança; mas também a tomada de consciência por parte da sociedade e, sobretudo, de alguns artistas que passaram a encarar o espaço público como suporte expandido, democrático para melhor fruição e descentralização das actividades artística do centro da cidade para o espaço periférico. Este facto pode ser consi derado como um dos aspectos relevantes na contemporanei dade a ter em conta para justificar o reaparecimento massivo, pela primeira vez na história nacional, de murais meramente artísticos votados ao serviço da arte pela arte, onde os temas predominantemente retratados abordam questões criativas e problemáticas sociais que reflectem directamente as vozes dos artistas, sem nenhum condicionalismo de carácter político -partidário, como acontecia outrora com os murais e os restantes monumentos produzidas no contexto colonial e pós-colonial.

Há quem associe esta feliz reviravolta da massificação da arte urbana através do muralismo (grafitis, pichagens, mosaicos e pin turas) a uma continuidade da revolução cultural que em tempos foi vivenciada pelas gerações anteriores à indepência a partir do bairro de Mafalala, bem como no exterior, tendo como refe rência ideológica os Estados Unidos da América onde decorreu o notável 'Renascimento da Cultura Negra' em Harlem nos primór dios do século XX (Fohlen.1973:40). Actualmente, o (re)surgimento de vários movimentos e espaços culturais de interesse urbano, tais como “Eu Sou do Gueto”, “Maputo street art”, “Museu e Projecto Utopia Mafalala”, “Restaurante e Galeria Piriquita's”, “Hodi Maputo Swing e Polana Creative Space”, estes últimos sediados no bairro da Polana Caniço, entre outros, constituem uma prova de resiliên cia cultural face aos desafios sócio-culturais e económicos presen tes. É neste universo de acontecimentos que o actual cenário de florescimento da arte urbana na cidade capital tem as suas raízes.

40

o Percurso da arte urbaNa No ceNtro e Nas Periferias de MaPuto

Parte significativa das obras que constitui o presente mapeamento da arte urbana encontram-se dispersos essencialmente em três distritos munici pais dos sete que compõem a cidade, especificamente: (1) no distrito urbano de KaMpfumo que compreende às seguintes áreas: Baixa da cidade, Central; Polana Cimento, Alto Maé, Sommerschield “I”, Malhangalene e Coop. (2) dis trito urbano de Nlhamankulu, integra os bairros de Aeroporto, Chamaculo, Malanga, Mikadjuine, Munhuana, Unidade 7 e Xipamanine. (3) Por último, o distrito urbano de KaMaxaquene composto pelos bairros de Sommerschield “II”, Mafalala, Polana Caniço, Maxaquene e Urbanização.

Outros Distritos

3-distrito urbano de kamaxaquene 2-Distrito urbano de Nlhamankulu 1-Distrito urbano de KaMpfumo

41

”

No contexto da cidade, Mavec aponta o caso do surgimento de vários núcleos sonantes (in)formais ligados ao Hip hop1 no seio do bairro central, Malhanga lene, Coop, Maxaquene e Polana Caniço, entre outros, num intervalo temporal que compreende os anos 80 a 2000.

O artista avança ainda que “os fazedores do Hip hop encontram na arte do grafiti um meio de comunicação visual nas ruas e avenidas”, e que através das mesmas foi possível expandir, democratizar, impor os seus ideais e con ceitos identitários. (Mavec, 2022). Os artistas de rua, como Shot B, Afroivan, Bruno Chichava e outros mais jovens ainda, como o caso recente do Djinafita, são resultado da história e práticas artísticas forjadas entre a música e as artes visuais, que atravessam distintas gerações e períodos. Na perspectiva do pen samento do Mavec (2020) o “Hip hop surge no contexto da periferia, enquanto identidade subalterna, razão pela qual a sua aceitação sempre foi problemática no seio das classes dominantes até então” (comunicação pessoal).

1 Tais como: TBB, Dabomber, Monarquia Negra, Rappers Unite, Tropas do Futuro.

153

diMeNsão PerforMatiVa da arte urbaNa

Visto que a arte urbana não constitui nenhum estilo material ou estético, ela transcende as terminologias ou conceptualizações que caracterizam, por exemplo: os movimentos artísticos euro peus como o cubismo, fauvismo e muito mais. A informalidade que caracteriza a arte urbana contemporânea constitui-se como um dos principais princípios democráticos e liberdade artística. No entanto, a arte urbana pode ocorrer em diferentes âmbitos que abrangem as seguintes dimensões: estatuária celebrativa; arranjo urbanístico; entretenimento; panfleto/ grafiti; modo crítico e poético, de acordo com a curadora Gabriela Vaz Pinheiro (2018).

Porém, cruzando as diferentes modalidades da actuação da arte urbana em analogia com as obras dominantes no con texto da cidade de Maputo em revista, compreende-se que ela abarca os diversos âmbitos propostos pela curadora supracitada. À luz deste pensamento importa reforçar a existência da arte urbana na componente performativa, visto que este género é cada vez menos visível nas ruas, avenidas e espaços públicos de lazer. De modo geral, a arte performativa urbana integra-se no domínio do entretenimento, neste campo projectam-se na vida artística da cidade a existência de grupos e movimentos que se dedicam às actuações de rua, por meio da música, dança, cenas lúdicas e performativas, nomeadamente: W – Tofo, Robotizzy Shonguile Art entre outros grupos. Incluam-se também, nesta área, os trova dores informais ou ambulantes, animadores dos mercados munici pais da cidade, com destaque particular para o mercado do Povo.

155

Kassiano. “Rostos de Maxaquene”, 2022

Kassiano. “Rostos de Maxaquene”, 2022

artistas iNterNaciNais Na diNaMização da arte urbaNa

Maputo enquanto cidade criativa e cosmopolítica tem acolhido diversos artistas urbanos e colectivos internacionais. Em 2016 o consagrado artista espanhol Fidel Añaños (Mister), orien tou um foro de arte urbana que contou a participação de 15 artistas plásticos moçambicanos. Este intercâmbio resultou na execução de um mural no Feira de Artesanato, Flores e Gas tronomia de Maputo - FEIMA. Jonathan Darby é um dos artis tas de renome de origem inglesa, que durante a sua visita ao país em 2017, deixou ficar a sua marca criativa na cidade, através do mural pintado na avenida da Malhangalene.

Dentre vários acontecimentos, importa destacar o contri buto e participação de artistas multidisciplinares baseados em Zurique-Suiça, nomeadamente Taina e AemKa,os quais em 2019 participaram juntamente com artistas moçam bicanos na pintura do mural colectivo integrado no pro jecto Viva Con Água Moçambique, localizado na FEIMA.

Em 2021, outros artistas associados ao colectivo de arte urbana – Boa Mistura, baseado em Espanha - Madrid intervie ram na cidade. Estes também ofereceram à cidade das acá cias um notável mural situado ao longo da majestosa avenida Eduardo Mondlane, junto ao edifício da Cooperação Espanhol.

Mais artistas multidisciplinares, activistas e voluntários internacionais têm demonstrado cada vez maior interesse em desenvolver trabalhos e intercâmbios artísticos, em prol do desenvolvimento da arte urbana em Moçambique, a partir da experiência da cidade de Maputo. Andy Leuenberger é um dos artistas e activistas alemães que ao longo deste ano (2022), pintou uma obra em parceria com o muralista moçambicano Afroivan, fundador do Maputo street art. A par disso, e presente mente, a ilustradora italiana Zallicus Alice Zaniboni, além de ter pintado alguns murais em colaboração com os artistas Afroivan e Kassiano, também tem prestado a sua assistência na realiza ção de outros murais no interior do bairro de Chamanculo.

158

É inegável o interesse e reconhecimento crescentes da arte urbana, dada a sua importância na vida das comunidades, no que concerne à educação artística, bem como o seu poten cial no processo de activação espacial dos espaços marginaliza dos. Não obstante, nota-se a ausência participativa de artistas mulheres nesta área, embora como é evidente, este género de criação, no panorama nacional das artes visuais, ainda seja prática de um número bastante reduzido de artistas, quer de emergentes como de consagrados. Primeiro, é um exercí cio relativamente recente e que, nos moldes actuais, se centra mais no artivismo do que necessariamente numa prática essen cialmente comercial, como é inerente à venda de obras de arte moderna e contemporâneas materialmente transportáveis nas galerias e museus. Por outro lado, o seu carácter cívico-ape lativo e à priori menos comercial toma um aspecto desafiador para quem deseja desenvolver a carreira artística neste domí nio. Talvez por isso ainda não tenha atraído muitos praticantes.

A arte urbana requer outro tipo de financiamento muito mais estruturado, e, infelizmente, o contexto nacional actual ainda está muito longe de poder satisfazer as expectativas.

Embora iniciativas do género sejam sempre relevantes porque permitem criar novos públicos e atrair a sensibilidade dos mais diversos públicos que modulam o tecido social e os mecanis mos de recepção das artes, desde curadores, coleccionadores, patrocinadores e sociedade civil; sem descurarmos a possibili dade de poderem atrair mais investimentos para o sector e uma consequente valorização ulterior, tão necessária. Desta forma, poderá ser possível, num curto espaço de tempo, posicionar a cidade de Maputo no circuito internacional de arte urbana.

161 desPedida

Abreu, José Guilherme. (2015). "Arte Pública Como Meio de Interação Social: Da Participação Cívica ao Envolvimento Comunitário" in Almeida, Bernardo. Rosendo, Catarina. Margarida, Alves. (eds (2015), Arte pública: lugar, contexto, participação. Câmara Municipal de Santo Tirso: Instituto de História da Arte, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (IHA – FCSH/UNL), pp. 171-174.

Almeida, Bernardo. Rosendo, Catarina. Margarida, Alves. (eds.) (2015). Arte Pública: Lugar, Contexto, Participação, Câmara Municipal de Santo Tirso: Instituto de História da Arte, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Huma nas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (IHA – FCSH/UNL).

Campbell, Brígida. (2015). Arte Para Uma Cidade Sensível. São Paulo: Radi cal Livros.

Cossa, Emílio (2019). Ritmo, Alma e Poesia: A história e as Estórias do Hip hop em Moçambique. Maputo: Editora.

Costa, Alda (2013). Arte em Moçambique – Entre a construção da nação e o mundo sem fronteiras: 1932 – 2004. Lisboa: Verbo.

______ . (2019). Arte e Artistas em Moçambique Diferentes Gerações e Modernidades / Art and Artists in Mozambique: different generations and variants of modernity. Maputo: Marimbique.

Harvey, David. [2012] (2014). Cidades Rebeldes: Do Direito à Cidade à Revolução Urbana. (Trad. Jeferson Camargo). São Paulo: Martins Fontes –Selo Martins.

162 bibliografia

Instituto Nacional de Estatística. (2019). Recenseamento Geral da Popu lação e Habitação. (IV CENSO 2017). Disponível em: http://www.ine.gov.mz

Ngoenha, Severino Elias. (2016). “A (im)possibilidade do momento moçam bicano - Notas Estéticas”. Maputo: Alcance Editores.

Onwezor, Okwui e Oguibe, Olu. (Ed.). (1999). Reading the contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Marketplace. Kirkman House, London: Institute of International Visual Arts

Sachs, albie. (1984). Imagens de Uma Revolução. Minerva Central: Maputo

Sinanhal, Tembo João. (2016). Arte Pública em Moçambique – Maputo Intervenções nos espaços públicos a partir da prática artística do Mural. Disponível em: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/84636 (data da última consulta:11/08/2022. 15:09).

Victor, Correia. (2013). Arte Pública-Seu Significado e Função. 1ªedição. Lisboa: Editora Fonte da Palavra.

Pinheiro, Gabriela Vaz (2018). Memória e Representação, Cidadania e Poder. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YfDDfM454SA

163

This book has been possible thanks to the collective effort of many people but, first, we would like to thank the artists who are mentio ned in these pages, in one way or another, for embellishing the walls of our city, Maputo. Each and every artist mentioned herein deser ves special acknowledgment. We would have liked for more women to have been included in this book and we, at the Spanish Cooperation, are working towards including more young women in this art form.

The Spanish Cooperation strives to build bridges between Mozambican artists and the international public, so their efforts may be recognized across the globe. This Project proposes to introduce both the Mozambican public and the international community beyond our borders to the current art scene, and simultaneously offer a historical perspective of Urban Art in Maputo.

Up until now, Maputo and its walls have been a well-kept secret from the world. The Spanish Cooperation would like to reveal this secret to the world by offering this humble guide, which will allow sightseers to get to know the city through its walls.

We would like to thank Ethale Publishing for participating in this edi tion. We would also like to thank all of the people who joined forces to make this project a reality and, above all, we would like to thank all the artists, both Mozambican and foreign, who have made it possible for public spaces to become more welcoming. We hope that the beauty these artists create will allow us to keep on improving, as people.

Cerezo Sobrino Ambassador of Spain in Mozambique

Maputo, November 2022 .

166 Preface

Alberto

The purpose of this book is to focus on urban art within the context of the city of Maputo. One of its objectives is to document the works and the respective journeys of the artists working in this area.

The mapping process resulting from this publication will allow us to understand the plu rality of recent interventions throughout the city, divided between the urbanised centre and the periphery.

Given the indispensable value of this form of art in the growth of the city’s cultural life and landscape, the intention is to contribute to the appreciation for and involvement in this art form. Throughout historical periods and in different contexts, urban art has long been one of the artistic vehicles of social communication. In contemporary times, it is increasingly presenting itself with recourse to new materials, new aesthetic forms, themes and dynamics of expression.

Although the focus of this book is on contemporary urban art, it does not altogether ignore the contribution of relevant works produced in the colonial period, some of which are still accessible for the public’s pleasure.

Urban art is currently (re)emerging with increased exuberance in suburban settings as a way to connect and unify the two totally contrasting areas of the cement city “Xilun guíne” (Lobato, 1970), namely the properly urbanised space and the “tin city, ghetto” shanty town, initially characterised by insufficient basic sanitation and improvised hou sing built with makeshift materials.

The massification of urban art in the peripheral area seeks to restore the social status of these areas, historically “ghettoised” by ideological barriers, achieving greater social equality and artistic democratisation.

167 iNtroductory Note

Titos Pelembe, 2022

the city aNd its architecture: suPPort for a MuseuM artistic iNterVeNtioN iN Public sPaces as aN actioN for sociocultural aNd ecoNoMic stiMulus

Ricardo Suárez Acosta

Did you know that urban artists can boast that their works are more visited than large institutional exhibitions? For this and other reasons, don't you think that street art, artistic intervention in public spaces, urban art, has the right to figure in the history of recent art? The die is cast. And did you also know that graffiti is the only artwork prosecuted by law? Let's reflect on that.

A few decades ago, cities around the world were competing for the greatest and most spectacular buildings by accredited and world-famous architects, in a race from which none emerged the winner. Many of these properties were styled in innovative and sophis ticated museum-like and cultural designs that symbolised the wealth or importance of these cities, replacing the magnificent cathedrals or unique buildings in yet another example of how culture trumps religion and aesthetic politics as the most obvious sign of success. In that clash of megalomaniac proportions between the official and the public, in what was a sui generis fashion (not yet completely extinct), we can see the corrupt cadavers and skinned skeletons – alluding directly to the properties that lie vacant or have questionable or limited use – in a “Disneyfied” and “Instagram-able” world, where cultural aspects have become trivialised and what now makes sense is simply “having been in that place”. We live with this stigma that will surely be the subject of in-depth studies in the near future by sociologists and anthropologists, who will determine that in this world way of life we lived an easy, fun-filled life, even though everything remained the same, drained and monotonous.

Today, cities are intended to be sustainable and creative, where uniformity - with marked (in some cases) and inadequate (in so many others) exceptions - is set as an essential premise, leaving behind projects that are pretentious and fatuous, even if spec tacularly innovative. The economy of a past era, which seemed to support everything, is no longer the same as the one in which the world currently operates, and there needs to be a lot of balancing and juggling acts in play to perpetuate that anachronistic sno bbery (now transferred to the ostentatious and immodest countries of the Middle East).

Even so, and with the commitment of urban planners, designers and architects, in today's cities, inherited from an evolution which goes from organic to functional and back to neo-organic - with periods of debate and coexistence between functionalists and organicists -, passing through rationalism, the “international style”, and drifting into post-modernism and contemporary procedures, and in difficult coexistence with history and the past, the same problems persist: the delineation of housing areas, logical circu lation, orientation and free habitability. All this is transferred, in turn, to the development of the city; the attention to human beings as a collective implies a greater complexity

168

CEMFAC Management (La Ciudad en el Museo, Foro de Arte Contemporáneo)

of structures, but at the bottom of everything is the absolute need to reconcile problems of sensitivity, which, in the end, only have an aesthetic solution, in the deepest operative sense of the word.

When we speak of this aesthetic solution, we mean eurythmy. But, at this point, where can we find the use of gesture and of colour? Our cities are the environment or the arena for life, an extension of our habitats, our domiciles, they are our homes. If cities have a certain prison-like, monochrome or greyish appearance, it is not only because of the construction materials used, but also due to wear and tear, to their own obso lescence, to atmospheric conditions and aggressive and corrosive pollution. The impor tance of colour is greatly undervalued, as has been shown by the physiological and psy chological changes and reactions human beings experience when exposed to different colours. However, in the history of art, colour has always found its point of connection with the human soul.

It is the residents of the city, in the broadest sense, first and foremost, and the visi tors, secondly, who deserve the vital scenario in which they live to become more affa ble and habitable. Hence the importance of our key subject, urban art, because artis tic intervention in civil space, supported by public administration, together with street art and some manifestations of graffiti, in almost all cases operate within the boundaries of and comply with the conditions that help regenerate these places: they are a catalyst for artistic expression, rescuing the “grey” spaces and strengthening the community. The economic, social, physical and aesthetic benefits brought together by public art are tangible and are always exportable experiences: artistic interventions improve the visual quality of public spaces and promote new social interactions in the environment. Activi ties and increased traffic allow safer and more interesting places for informal encounters that attract new visitors to the place, strengthening and increasing citizens’ participation. There is an improvement in the quality of the urban space experience, with encoun ters becoming more participatory and creativity being stimulated. The place acquires a new meaning and identity in the urban imagery, with different ties and landmarks being generated. The community is strengthened, new use of space is promoted and opportu nities for local commerce are born.

For these and other reasons, artistic intervention in public space, from the perspective of an urban strategy, cannot be reduced to being merely aesthetic in value (thinking of the decorative or ornamental). It is not just about beautifying the city's official arte ries; contemporary art, as a process, reconciles us with the street, with the public scene, with our natural (metropolitan) habitat; it brings us closer to our particular culture and idiosyncrasies and makes our everyday experiences more memorable. This is what improves the relationship between the city and its inhabitants, bringing positive changes not only to its image, but also to the quality of life of its neighbours. This is why we believe that these actions, in which the artist is the creator and mediator, generate not only more beautiful and visually ergonomic cities, but also communities that are more prosperous, deeper-rooted and dynamic.

La Ciudad en el Museo, Foro de Arte Contemporáneo (CEMFAC) [The City in the Museum. Contemporary Art Forum] is a case in point. From the moment it was conceived in 19992000, it was designed as a public art project which proposed to transform the daily tra ffic of passers-by, whether citizens or visitors, through the streets of a city, in this case Los Llanos de Aridane, on the island of La Palma (Canary Islands – Spain), bringing current

169

painting closer to the widest possible public; taking it out from the traditional white-cube museum and placing it in the street.

By integrating the interpretations of a visual artist in the chosen spaces and selec ting what appeared to be “black spots” in urbanistic development (division, perimeter and closing walls and façades) for this purpose, the order of the historical identity of an urban centre is shattered and this landmark is given a new meaning, albeit in a positive and respectful way which is in balance with the environment in which it is located. Based on a creative contradiction, right from the start, CEMFAC proposes a rupture and an inte gration of the space between artistic displays so distant in time and design, that cultural inertia is overcome, thereby encouraging passers-by to go beyond a static contempla tion and to rethink their experience of the city itself. Just like any initiative seeking public relevance, this museum was created with the intention of achieving a series of objectives that would improve the quality of the area in question. One of the goals of this innova tive concept for a contemporary painting museum was to achieve high visual and social return and, in turn, to become an alternative to the lack of a sense of culture and leisure underpinning the very origin of museums, often faded due to more importance given to the brick-and-mortar structure of the museum itself than to its content. For some scholars, this situation transforms museums into mere cultural shows, with an occasional attraction for the works of art that, due to the same inertia, are transformed into myths.

The museum itinerary offered by Los Llanos de Aridane opens new possibilities to reco ver that lost or absent sense of culture. A stay in the city is, in itself, a visit to a museum lived in daily, providing a more relaxed reflection on contemporary art by naturally invol ving spectators who enter the space (as if in another dimension) on their daily meanders through the different scenarios that are its fabric, into the urban landscape. Pavements, squares, parks, cafés, bookstores, commerce in general, and everyday life are an essential part of this unusual museum of landscapes where the paintings and murals are visible and surprise passers-by who simply have to look up, separate the details and put them together again to perform their own analysis.

The implementation and management of the project intended, from the outset, to follow a path that would develop and unite culture with social and economic aspects, focu sing on tourism, an undeniably important sector in the Canary Islands, which the island of La Palma only began to exploit fairly recently. Paradoxically, the delayed exploita tion has been advantageous for the region, allowing its progress to mark it as a quality destination in every sense of the word. The tourism on offer is diversified and includes an element of cultural tourism, which is recording an impressive upswing. This tourism encourages the exploitation of natural and cultural resources as an important driver for balanced economic development.

The fact of living in a museum, of being constantly inside it, makes everything that sur rounds us reveal a meaning that perhaps existed once, but that has faded with the course of everyday life. Moreover, by becoming a hub of attraction for new audiences, it unques tionably favours a much broader development. Having a cup of coffee, an aperitif, lunch, or even shopping without ever losing sight of the artwork is an experience where con templation and life intermingle, while simultaneously being a source of income for local businesses.

La Ciudad en el Museo - Foro de Arte Contemporáneo, has been the stage for numerous fairs, seminars, congresses, debates, conferences and expert panels since its inception,

170

and it is currently involved in a special unique project of cultural connectivity spanning three continents (Africa, America and Europe). Examples of these internationalisation actions include those carried out in: Maputo (Mozambique), with the creation by the Boa Mistura collective of a large-scale mural on the side façade of the Spanish Techni cal Cooperation Office building, titled “Mulher Capulana” [Capulana Woman] (July, 2021), which aims to show the strength and importance, the empowerment, of women on the African continent; in Fort de France (Martinique-France), with the creation of a large -scale mural by the French artist 3TTMan, titled “Black slaves sweating (cutting cane for the rich)” (June, 2022), which reflects the past reality of the island and its histori cal consequences (initiative linked to the Thousand Murs Festival); and Quito (Ecuador), with the creation of a unique fresco mural by the urban artist Okuda San Miguel, titled “Metaverse Embroiderers” (May 2022), in which his particular vision represents one of the traditional crafts of this Ecuadorian city, embroidery, which has been declared a cul tural heritage (the embroiderers of the Commune of Llano Grande, Calderón Parish). This mural was painted as part of the ambitious urban art project, CaminoArte. The work done in Senegal (Dakar), for the Biennale (2018), in the refugee camps of Tindouf (Algeria) (2019), in Martinique (Fort de France) and the façade mural by Sara Fratini (May 2022) are also worthy of mention.

It is worth highlighting the previously mentioned action carried out in Maputo, in July 2021, which led to the creation of a large mural on the dividing wall of the Spanish Cooperation Technical Office building (Avenida Eduardo Mondlane, 677), commemora ting the 40th Anniversary of the positive collaboration between Spain and Mozambi que. The Boa Mistura collective was in charge of creating this great piece, which clearly reflects the multiculturalism on the African continent, and uses the image of a Mozam bican woman and her capulana as an undeniable echo of the state of empowerment of a nation, of the women of this country, in a vast region wishing to assert and position itself in the world. The image we see today on that big wall resulted from discussions held through workshops with businesswomen involved in cultural and social life and, obviou sly, those who live off the creation and sale of this representative artwork. The women all felt that this piece has allowed them to be “seen”, since they participated in the crea tive process along with the group of Spanish visual artists. The resulting image is of a woman, as if a capulana drawing, supported by different elements, powerful symbols that give strength to the discourse outlined in the workshops: a clenched fist, with a nail painted in pink, symbolising resistance, pride and solidarity; birds, symbolising true love, fidelity and respect; the moon, symbolising femininity, fertility and their cyclical nature; roots, symbolising anchorage, sustenance and birth; and branches of a tree, symbolising decisions and paths taken. Of course, the range of colours used in this piece was also agreed upon by the artists and workshop participants, revealing the importance of colour in the culture and in the art of the past and of the present in Mozambique.

This action was accompanied by training provided to the staff of Maputo City Hall’s cultural division, as well as to the Ministry of Culture, by CEMFAC technical staff. The pur pose of the training was to create awareness among these officers in relation to artistic interventions in public spaces and to explain how to correctly set up an urban art festival, or establish a public art museum, using the dividing walls of buildings, blind façades, peri meter walls and well-defined areas of this important Southern Africa capital of appre ciable urban value; and to do it in a possible ordered labyrinth or museum itinerary with these characteristics, whenever the project aims for temporary permanence.

171

It based on and through this cooperation, or so-called “appearances” that the multicul tural reality of the Canary Islands, and in the CEMFAC of the island of La Palma, in parti cular, is understood, showing that it is possible to have dialogue and a fusion of cultures through art. The city of Los Llanos de Aridane has become a tricontinental interlacing of African, European and American proposals connecting and interrelating the realities and uniqueness of urban culture or interventions within the public spaces of those places.

Thus, art represents an ideal path for human understanding. No matter which of its multiple expressions one is dealing with, it is designed as a language in which we can all communicate and establish firm bonds. After all, creations are ways of looking at exis tence that can only find their own raison d’être when shared. Artists seek to awaken the consciousness of their audiences and communicate their concerns through their work.

It must also be explained that, similarly to what happened to these prestigious works of architecture, currently – and for approximately fifteen years now – government admi nistrations of towns and cities are in favour of and even manage artistic interventions in public spaces, implementing public arts projects and holding urban art festivals. The aim of this is to beautify these places and to give them a social, cultural and econo mic boost. Once again, we are faced with a trend, although much more accessible than the one previously mentioned, but with an impact that is, on the whole, comparable. We hope that this trend does not fade and die, leaving artistic carcasses in its wake, since this type of work has an ephemeral component to it that needs to be taken into conside ration, and its degradation must be expected; these artworks must be subjected to res toration operations by their creators or replaced by other pieces. It is the responsibility of those who endorse these actions to ensure the promotion, didactics, teachings, enjoy ment, reflection and knowledge exchange inherent to these initiatives, as well as the preservation of something that becomes, through its creation, a legacy of that territory.

172

of ParadigMs

iN urbaN art iN MaPuto

AfroIvan

The history of urban art in the peripheral neighbourhoods of Maputo emerged as a con troversial reaction to the constant disputes over the conventional spaces for displaying and appreciation of national artistic output, in this case the galleries and foreign cultural spaces that are concentrated in the central neighbourhood’s circuit. Following modern tradition, these tend to be discriminatory and thus fail to give value to street art, clas sifying it as an act of vandalism. The term "vandalism" came into use after the French Revolution, at the end of the 18th century, when the noun "vandals" began to be associa ted with destruction motivated by social strife, as suggested in Stephen Kershaw's book, The Enemies of Rome: The Barbarian Rebellion against the Roman Empire (2020).

Maputo, as a small city with colonial roots, was naturally founded on laws of control, segregation and prohibition of the use of public spaces. Contrary to these rules, however, is the fact that the only art school devoted to teaching visual arts, the National School of Visual Arts, was located in the centre of downtown Maputo (from 1983 until 2010, when it was transferred to the outskirts of the city), which undoubtedly contributed to the massification of a type of culture that was confined to closed spaces, both in institutions (museums and galleries) and in artists' studios.

The early 2000s mark the reawakening of various interests in the context of urban art, after the decline in the revolution-related murals that vividly represented the natio nal post-independence scenario. It was during this period that multiple multidisciplinary interventions such as those of David Bonzo, graphic design, video, poetry and hip-hop rhythms emerged. It was also the time when light music, or easy listening music, in gene ral, developed; when the Rastafari culture emerged, which was also very significant in inspiring artistic actions in urban spaces.

The artworks commissioned for prime public spaces in the city by renowned artists such as Malangatana, Naguib and Titos Mabota, among others, had a positive impact and, quite frankly, stirred the imagination of visual arts students who, for the most part, were facing undeniable difficulties in terms of their economic survival. On the other hand, the social constraints suffered by these artists may have ignited in them a craving for guaranteed immediate rewards, a desire that was dashed and, feeling discriminated against, resulted once again in an increased rejection of or distancing from the voluntary spirit, or artivism, that guides the practice of public art. For this reason, the few artworks occupying public spaces in the city are the result of pieces validated/commissioned by groups of the city's economic and social elite.

Public art in the urban context of Maputo had always been commissioned by gover nment institutions. Later on, particularly from the 2000s onwards, there was an expan sion of the platform for artists' intervention, with commissions for advertising art, bill boards or giant murals. Thus, these commissioned works, often educational in nature or sometimes aimed at political campaigns or advertising for everyday products, pro vided an opportunity for the communities’ first contact with murals in public spaces. When more private enterprises entered the market and the demand for murals gained

173

( des ) coNstructioN

a market share, it was this type of mural that multiplied the most, outdone only by the revolution-related murals. Since these murals were mostly only for commercial purposes, they failed to contribute to a perception of behavioural change, and to provide a healthy challenge to the fixed mindset or cultural representativeness at the time.

Urban art in Maputo took on new life when independent artists, rebelling against their significant economic difficulties and the difficulty in accessing galleries that could result in the fruit of their work leading to monetary gain, and galvanised by their passion for the arts, began to paint on the walls of their own neighbourhoods. I, myself, am one of these artists. In 2012, I started painting inside Bairro Unidade 7, where I was born and grew up, in an attempt to express the sensitivity of the community and the influence of the traditio nal music that surrounded me (post- independence, particularly around 1980/90, when a Ngalanga (a traditional dance from the south of Mozambique) ensemble of dancers and timbila players from Gaza and Inhambane settled in this neighbourhood. This is the same ensemble that would later inspire other musicians to form bands with the same music genre in the neighbourhoods of Hulene and Polana Caniço).

The irrefutable work of artists such as Shot-B, Mavec, Villa Terry, Mateus Sithole, Kas siano, Djinafita, and others who were part of the new wave of artists who appeared after 2016 provided urban art, especially murals, with increasing social recognition and visibi lity in recent times. Independent street art has now clearly become more significant, with a growing number of murals appearing in the Maxaquene, Polana Caniço and Magoanine neighbourhoods. The richness of their expression and creation was reflected in the works, resulting in a closeness being created between artists and ordinary community mem bers, who saw their urban spaces being transformed into colourful and embellished areas – although with no guarantee of the works lasting for long since walls are often kno cked down, or repainted for new landscapes and signatures are removed. Also, erosion and ageing from exposure to the elements (sun, rain, wind) softens the paint pigments and the murals are gradually destroyed.

This is where photographs play such an important role (photography is, after all, a pio neering urban art which, since the beginning of the 19th century, has become an exten sive archive for all modern life) and it is here, through the lens of Ildefonso Colaço, that the intersection of urban art and photography takes place. This is an artist who also explores the independent creativity of urban art, gracing the space where he lives with his work; recording and building memory and bringing longevity not only to the murals, but also to many other aspects representing human presence in the peripheral landscape.

The performing arts have also discovered a new stage here, with students from theatre and cinema coming together with the same need for expression and recognition within the spaces where they grew up and live their daily lives.

It is also worth mentioning that, similarly to what has been happening in other parts of the world, individualism is also an emerging reality within the Mozambican cultural space. This has been reflected more recently in the growing and interesting participation of female artists, who are also slowly trying to break away from the confines of enclo sed spaces to other more social open-air experiences, where the interaction with their audiences, mainly residents and other newcomers, is more spontaneous.

In Maputo, the freedom to want to intervene in the urban landscape, to transform it, is very marked and is on par with the demand to see one's artistic work displayed

174

in galleries. In this sense, an artist’s own investments are the first indicators of one who dreams. Nowadays, the strengthening of social networks has provided a platform for a multiplication of meetings and interactions between the creatives who trained in technical schools and universities, and the many self-taught creatives who are aware of the need to professionalise their skills and empower themselves in the Visual Arts, thereby ensuring their continued activity within an increasingly demanding environment of cultural manifestations.

Thus, the recent and striking pervasiveness of urban art in the peripheral nei ghbourhoods of Maputo represents the embodiment of freedom of expression and of the possibility to transform neglected and abandoned spaces into open-air galleries, with the added intrinsic historical value that comes from a greater and more immediate harmony with the different themes directly involving residents in real time and space. The relationship between the artist and an unconventional audience is deeper and more expressive, because of the open curiosity of those watching the artists performing their work “live”. This is one of the points I find most important when producing urban art and which, in my opinion, gives richness to the multitude of purposes for creating this type of art, from simple entertainment to storytelling, educating or even influencing beha vioural change in economically underprivileged communities.

This publication, which includes from among its different contributors, photogra phic contributions by IIdefonso Colaço and textual contributions by Titos Pelembe (who is also a visual artist), intends to safeguard, record and be a testament to an historical era of contemporary urban art in the city of Maputo, simultaneously establishing models and challenges for the use of urban space, and stirring a visual and cultural regene ration of the urban community, from the peripheral neighbourhoods to the upmarket neighbourhoods of Maputo. Our desire is for this rare reversal to become a springboard for further dialogue.

Furthermore, the creative diversity along with the quality of other approaches and techniques and the mapping of urban art on murals both within and outside the city, validate the importance of this book, with its different applications, design and practi ces, as reference material for students and aficionados of street art. The artists involved in this type and in other expressions of urban art, whether voluntarily or unconsciously, are deeply grateful.

175

street art: backgrouNd, challeNges aNd New PersPectiVes

Titos Pelembe

Past aNd PreseNt

Artistic expression in public spaces dates back to the beginning of human civilizations as is evidenced through cave paintings. Generally speaking, the various expressions of artwork keep pace with the technological, social and political progression of mankind. For this reason, several contemporary studies focus on the rise and concepts of “urban art” or “public art”. In Mozambique, in particular, urban art or creating art in public spaces also originates from older traditions. From this perspective, our interest is to situate urban art based on two bipolar contexts, more specifically the colonial period and the post-revolutionary period, from 1975 to the present.

Some artwork from the colonial era, namely murals or statues, were intended as dis tinctive symbols of Portuguese colonial power and were situated in specific built-up areas of enormous social importance. To this day, some of this visual art still enriches the city's architectural and urban landscape. Included among some of the visual art that stands out we have: the polychrome ceramic panel by the Portuguese artist Querubim Lapa (1925-2016), on the façade of old Bank of Mozambique building (former Headquar ters of the Banco Nacional Ultramarino) and the Monument to the Dead of World War I (European and African Combatants) (1931), by the sculptor Rui Roque Gameiro (19061936), on display at the Praça dos Trabalhadores [Workers' Square]. Included among other works are two large bronze sculpted panels, by the sculptor António Duartes, and an uni dentified medium-sized one in marble, sculpted using basso-relievo and alto-relievo [low and high relief] sculpture techniques, embedded in the façade of the Rádio Moçambique building. There are also several architectural works of art by the famous architect Pancho Guedes, that can be seen on the façades and gables of some of his emblematic buildings throughout the city, as well as the panel by the artist António Quadros at the branch of the Millennium BIM bank, on the corner of Av. 24 de Julho and Av. Salvador Allende.

During the turbulent times of the post-independence revolution (1975), some of the artwork symbolising colonial power and sovereignty were removed from their public places of display, while others, particularly monumental sculptures, were destroyed. This was the case of the statue of Mouzinho de Albuquerque, which was removed from the square, now called Praça da Independência [Independence Square], and replaced with an imposing statue of the first president of independent Mozambique, Samora Moisés Machel (b.1933-1986).

176