NITROGEN

Weeds show up early — and steal yield fast in the spring. That’s why growers rely on fall-applied soil active solutions like Valtera® EZ, Fierce® EZ and Astir®. These proven pre-emergent herbicides deliver broad-spectrum control across cereals and pulses, helping you manage resistance, stay flexible and lead the season instead of chasing it. Less in-season pressure. More flexibility when it counts. You don’t need to overhaul your season. Just upgrade your start.

COMBINES NEED MONITORING

The concept is good, and significant research dollars have gone into the development of auto-adjust combines, but set and forget can mean increased canola harvest losses. That is the finding of a research study conducted by the Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute (PAMI) during harvest 2022. The objectives were to quantify the change in environmental conditions during a typical harvest day and the effect on combine losses of canola, and to measure the performance potential of combines with auto-adjusting settings.

TECHNOLOGY

6 Bird’s-eye view on nitrogen in plants

Drones to measure in-crop nitrogen. CEREALS

8 Pre-harvest sprouting

Genetics to solve pre-harvest sprouting.

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

10 Optimizing nitrogen fertility in winter wheat

4Rs especially apply to winter wheat.

12 Where do enhanced efficiency fertilizers fit EEF nitrogen 101.

SOIL AND WATER

24 Every drop counts

Subsurface drip irrigation.

RESEARCH

28 Teff on the Prairies

Teff could be an option.

SUCCESSION PLANNING

30 Farmer readiness

Readiness impacts resources.

AGRONOMY UPDATE

ON THE COVER: This unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is taking hyperspectral images over a wheat crop near Lethbridge, Alta. Photo courtesy of Keshav Singh. September

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of TopCropManager . We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

by Kaitlin Berger

TALK ABOUT TRANSITION PLANNING

What do you want to do when you grow up?

I remember wrestling with this question, especially around the age of 17 when I was researching potential career options and applying for university. I’d been “working” on the family farm since I was able to walk, but I never considered taking over the farm. I’d always had a propensity towards writing and music, and I didn’t see how that would work with farming. Plus, my older brother seemed like a better option for succession since he was getting a degree in agriculture.

In a sense, we’re all in the 17-year-old mindset asking the same question...

However, when I came home to work on the farm in the summer and on the weekends during university, I started to second guess what I really wanted. My older siblings were around less, and I liked the sense of responsibility and confidence I gained as I managed the barns when my parents were on vacation. Maybe farming was a career I should consider. Long story short, I landed a career in agricultural writing and moved a few provinces away from the family farm. In fact, all of my siblings started off-farm careers and moved away. Now, it looks like my parent’s first-generation farm may remain a single-generation family farm. But who knows for sure? The decision has yet to be made.

Recently, I’ve conducted multiple interviews around transition planning. You can find one of them on Top Crop Manager’s Inputs podcast on our website where I spoke with Sarah Stamp, founder of Sarah Stamp Farm Consulting. She emphasized the importance of soft skills when it comes to transition planning. And for those who are retiring and selling the farm outside the family, she suggested they write down the story of their farm to hold onto the legacy in a tangible way.

You’ll also read about the other interview in this issue – an article that answers the question on why there are so few farms in Alberta with transition plans, a shockingly low number given the average age of farmers across Canada (page 30). I think the article offers a practical perspective on why we delay planning, and the podcast provides practical advice on how to work up the courage to start communicating about it.

That said, I get why farm families are hesitant to make a transition plan. It can feel overwhelming for both the older generation and the younger generation. In a sense, we’re all in the 17-year-old mindset asking the same question: What do we want to do when we grow up?

Editor KAITLIN BERGER (403) 470-4432 kberger@annexbusinessmedia.com

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Coordinator LAYLA SAMEL (416) 510-5187 lsamel@annexbusinessmedia.com

Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW

CEO SCOTT JAMIESON sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

It all starts with the soil. When it’s healthy, everything works better—stronger roots, improved structure, and more efficient use of nutrients. But after years of wear, many soils need support to perform at their best. Black Earth humic solutions help restore soil vitality from the ground up. With high-purity Humalite and consistent quality, our products enhance moisture retention, boost nutrient availability, and improve overall soil health—naturally. Easy to integrate and built for results, Black Earth gives your soil the foundation it needs for long-term productivity.

Scan the QR code or contact us to start elevating your soil today.

sales@blackearth.com www.blackearth.com

Bird’s-eye view on nitrogen in plants

Drones offer a faster, more affordable way to measure in-crop nitrogen.

BY LEEANN MINOGUE

Nitrogen (N) is one of the most expensive inputs for growers, which is why it’s important to optimize N use efficiency. To make that happen though, growers first need to be able to measure it in the field. The current methods include using soil tests to measure N in the soil and tissue tests to measure N in plants during the growing season. However, getting tissue test results takes time and requires pulling plants out of the ground. That’s why researchers are exploring a faster method – one that gives growers a bird’s-eye view.

Keshav Singh, research scientist and adjunct professor with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta., is using drones with smart sensors and the latest artificial intelligence (AI) technology to develop a faster way to measure N in growing plants. In conjunction with this study, Singh’s agronomist colleague, Charles Geddes, a research scientist specializing in weed ecology and cropping systems at AAFC Lethbridge, is using this data to compare the effectiveness of various N application rates and timings.

FINDING NITROGEN WITH A CAMERA

When we look at a field, we see only three spectra of light: Red, green and blue. “We cannot see beyond RGB colour space,” Singh says. A hyperspectral camera “sees” hundreds of spectral bands. “It gives us the subtle information which is hidden in the background,” he adds.

When light – or photons – strikes any material, that material emits a unique signature in electromagnetic spectrum. The signature includes information ranging from material properties to composition. Singh compares this to fingerprints – just as any individual can be identified by their unique fingerprint, any material can be identified by the light signature it emits.

Singh is a certified UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) pilot who operates an advanced drone equipped with a hyperspectral camera. This setup captures high-resolution images and measures light intensity across hundreds of spectral bands. To ensure accurate data,

he carefully calibrates the system and uses a sensor mounted on top of the drone to adjust for variations in light interaction, such as reduced reflectance from a plant on a cloudy day.

PREDICTIONS USING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)

ABOVE This unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is taking hyperspectral images over a wheat crop near Lethbridge, Alta.

With one pixel for each two to three centimetres on the ground, and measurements from hundreds of spectral bands for each pixel, the hyperspectral camera is generating big data. With this large amount of data, researchers need machine learning (AI) tools to generate useful information.

Singh and his team are using predictive models to analyze the data and identify the few spectral bands (of the hundreds measured) that reflect N content in plants. Different plant species reflect N differently, so separate models are needed for wheat and canola. Hyperspectral imaging is expensive and not for

commercial use. Multi-spectral cameras that measure only a few key spectral bands are more affordable. Once Singh and his research team identify the spectral bands that reflect N-content, they can eliminate the unnecessary spectral bands to build a cost-efficient system. Multi-spectral cameras equipped to measure only the key bands can gather data to estimate N content in wheat and canola.

Machine learning tools can develop models of the spectral signature for N in wheat and canola. Once the models are developed and verified, they can be used to estimate plants’ N-uptake in real time. This technology could be used to make prescription maps for precision fertilizer applications. It could also, feasibly, be used to adjust N application in-field using system-mounted multi-spectral cameras to adjust fertilization rates, changing the distribution of liquid N in real time.

MEASURING THE EMISSIONS

Singh and his research team ground-truth their model results with plant tissue tests, soil tests and measurements of N emissions into the atmosphere as nitrous oxide (N2O). “Nitrous oxide is always releasing from the agricultural system, but it’s releasing at a very slow pace. Measuring that small quantity in the air requires a very precise instrument,” says Singh. The team used cylindrical collars with a five-inch radius and 10 inches deep to take these measurements. These LI-COR collars are placed in the field before seeding and left throughout the growing season for continuous measurements.

Compared to carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide has a much higher global warming potential (GWP) and contributes significantly more to global warming. Although nitrous oxide remains in the atmosphere for a shorter time, one molecule of nitrous oxide traps 265 to 300 times more heat in the atmosphere than one molecule of carbon dioxide.

AGRONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL PAYOFFS

Reducing N emissions is positive for the environment and for growers’ wallets. By optimizing N use, growers are maximizing the amount taken up by plants or left in the soil root zone where it can be accessed by future crops.

Growers using zero tillage, planting cover crops and other methods to

increase plant material in the soil are adding to the amount of carbon stored in the soil, which removes the greenhouse gas from the air. Some growers sell carbon credits and receive a financial reward for this carbon sequestration. It’s possible that, one day, growers optimizing N fertilizer applications to reduce nitrous oxide emissions could also be rewarded for reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. That’s why it essential to have science-backed studies to identify the best ways to do this.

Singh and his research team are comparing nitrous oxide emissions from various N application splits at two study locations in Southern Alberta. In their studies, a portion of N is applied with the seed, with the rest applied in-crop. They’re analyzing 10 different application splits, including applying all the N with seed, applying 50 percent with seed as well as applying 50 per cent in-crop. These studies will be compared against control field plots where no N is applied.

Singh and Geddes are getting ready to suggest a best application split with sustainable yield. “This is the third year of a four-year project and predictive models need to be developed further with the new dataset,” Singh says. Studies in other geographic locations with different weather conditions will also be needed.

COMING SOON

It’s still early days for this technology, and validations are underway. This study includes many factors but involves only two locations and two crops. There is more work to be done before these drone-mounted cameras will be flying to collect useful information over most growers’ fields.

“Feasibly, within the next decade or two, the technology could provide farmers with a way to sense N-uptake in real-time and apply variable rate N in-crop based on the conditions experienced during early-season crop growth,” says Geddes. “This could help to reduce N losses to the environment and improve crop uptake efficiency, leading to more sustainable fertilizer use.”

The problem of pre-harvest sprouting

Researchers are looking deep into genetics to solve pre-harvest sprouting.

BY JOEY SABLJIC

The pre-harvest sprouting phenomenon in cereals isn’t anything new, but it’s a complex and costly global problem that’s eluded research efforts dating back nearly three decades.

THE COST(S) OF PRE-HARVEST SPROUTING LOSSES

Pre-harvest sprouting (PHS) happens when grains prematurely germinate while still attached to the mother plant before harvest. It’s thought to be caused by a combination of environmental factors, such as high humidity and moisture, as well as certain genetic traits like a lack of seed dormancy.

When grains germinate, starch content gets broken down and degraded, which reduces the quality of cereal for baking and malting. Growers might also see lower test weights, too. Generally, any wheat or barley with more than four per cent sprouted grains is downgraded at the elevator.

The global costs of pre-harvest sprouting losses are estimated to be around $1 billion. In Canada, that number is around $100 million per season in lost grain yield and quality.

PRE-HARVEST SPROUTING AND GERMINATION ARE NOT ONE AND THE SAME

Until recently, most research efforts have been focused on trying to breed PHS-resistant wheat varieties – but with little to no success. The $1 billion dollar question remains: What else can be done to address a near-unsolvable issue? Jaswinder Singh, plant science professor at McGill University, and his fellow researchers are trying to find an answer.

Their goal is to look at specific molecular markers to identify which mechanisms within the plant will influence whether it will sprout – and then eventually use those findings to aid in efforts to breed PHS-tolerant varieties for Canadian and global markets. “Pre-harvest

sprouting is such a complex problem and it’s one where there’s a combination of environmental conditions and genetics involved,” says Singh. “Plus, it’s unpredictable and you never really know if and when it will occur.”

ABOVE Purnima

Kandpal, a PhD student, demonstrating differences in pre-harvest sprouting (PHS) susceptibility and tolerance among wheat varieties to Jaswinder Singh.

Singh believes that the problem behind many of the breeding efforts to combat PHS is that they’ve been backed by the thinking that germination and PHS are one and the same – just at a different time of the year. “We’ve successfully bred wheat varieties that germinate faster and more uniformly. So, we have wheat where, if there’s the right amount of moisture, the right temperature and environment, it will germinate,” he explains. “The problem is that we’ve been operating under the assumption that when it comes to preventing pre-harvest sprouting, all we need to do is reduce the seed’s ability to germinate.” Rather than address sprouting, this only serves to put a damper on cereal crop productivity and yield.

TACKLING PHS FROM A DIFFERENT ANGLE

Given that sprouting and germination aren’t the same, Singh and his fellow researchers are taking a decidedly different approach than what’s come before. Rather than attempting to solve PHS by looking purely at the genetics that impact germination, they’re looking at the epigenetic mechanisms that might be at play within the wheat plant.

With epigenetics, different genes are turned on or off without altering the plant’s core DNA. For example, at the beginning of the season, the plant can sense –and decide – when conditions are right for it to germinate – or not. “The same epigenetic idea applies to PHS,” explains Singh. “There’s something within the wheat plant that’s activating under certain conditions and telling it to sprout at harvest. So, it’s really a question that goes far beyond straight genetics.”

FINDING MOLECULAR MARKERS THAT CAUSE PRE-HARVEST SPROUTING

According to Singh, the process of identifying molecular markers that influence pre-harvest sprouting has typically been done at harvest with mature plant samples. One method involves taking a non-sprouted wheat or barley plant, then exposing it to the high-moisture and humidity conditions believed to bring about PHS. Another method is known as falling number analysis, where mature wheat and barley samples are ground up and analyzed for high alpha-amylase content – an indicator of sprouting damage.

The main issue with both these methods, says Singh, is timing. “Not only do you have to wait the whole

season, but there are so many other factors at play. For example, there are three wheat genomes that each interact differently with the environment, then there’s the actual environment itself,” he explains.

Instead, Singh, his research team and collaborator Harpinder Randhawa from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Lethbridge research centre, have flipped the script to look for molecular markers that impact PHS resistance at the plant’s four-leaf stage. It’s at this early point in the season where they believe they’ve found the correct marker. “This is something that people have not touched before,” says Singh. “There are certain molecular markers that we can only pick out earlier in the season.”

Singh and the research team have been able to identify a small segment of DNA which, when present, means the variety is PHS-tolerant in more than 85 to 90 per cent of cases.

As for next steps, Singh says his hope is that wheat breeders will be able to use their newly discovered molecular marker as part of their breeding program in a bid to create truly PHS-tolerant varieties. In the meantime, the researchers hope to continue identifying new molecular markers which may give them an even greater chance at targeting PHS across more wheat and barley varieties.

“This molecular marker we’ve identified may only be useful for some wheat varieties,” says Singh, “but the more DNA strands we sequence, the better chance we have of being able to use gene editing technologies like CRISPR to tweak varieties without adding any new or foreign genetic material.”

Got Unwanted Pesticides & Old Livestock/Equine Medications?

Collection events are coming to Peace Region, Northern Alberta and Manitoba in Fall 2025!

Please store unwanted materials until a Cleanfarms collection event is held near you. We accept:

• Unwanted agricultural pesticides including seed treatment

• Commercial pesticides and pest control products

• Livestock/equine medications

Regions Peace Region – Alberta & BC Northern Alberta Manitoba When October 6 to October 10 October 6 to October 10 October 27 to October 31 Check cleanfarms.ca to find the full list of collection events for Peace Region, Northern Alberta and Manitoba from October 6 to October 31, 2025.

Optimizing nitrogen fertility in winter wheat

4Rs especially apply to winter wheat.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Back when ammonium nitrate was still available – before Timothy McVeigh blew up a federal building in Oklahoma City in 1985 killing 168 people – fertilizing winter wheat was fairly straight forward. Apply some starter nitrogen (N) at seeding, and then top dress with ammonium nitrate. Today, though, farmers have a choice of applying N with the right source at the right time at the right rate in the right place.

“Specific to nitrogen, the 4R principles should be top of mind, but also practical realities of each farm can’t be ignored. For example, some would prefer to band all fertilizer at planting whereas others would prefer less handling at planting, so timing of a split and the ratio of that split are important. These priorities may change year-to-year based on weather, nitrogen pricing and market outlooks for wheat,” says Brian Beres, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Lethbridge, Alta. “Our research seems to suggest splitting versus all-banded

creates similar yield outcomes unless the environment supports high to very high yield potential, which benefits from split applications.”

Beres has conducted numerous studies on winter wheat fertilization. With urea and liquid urea ammonium nitrate (UAN) being used as a replacement for ammonium nitrate, he has looked at applying these products using the 4R principles. One study looked at urea fertilizer strategies conducted from 2013 through 2018 across the Prairies. Dryland sites were at AAFC Lethbridge, Falher, Edmonton and St. Albert, Alta; as well as Indian Head, Sask. and Brandon, Man. Irrigated sites were at AAFC Lethbridge and Farming Smarter Lethbridge.

In the study, they compared different N sources and timing/placements, including untreated urea, eNtrench treated urea (nitrification inhibitor), SuperU treated urea (urease inhibitor plus nitrification

Where do enhanced efficiency fertilizers fit?

EEF nitrogen 101.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Enhanced efficiency fertilizers (EEF) have been around for several decades with Agrotain and Environmentally Smart Nitrogen (ESN) leading the pack. Since then, many more products have come to market.

“If you go back in history prior to April 1, 2013 – and that’s a not an April Fool’s joke – but as of April 1, 2013, we do not have any more regulation of efficiency for fertilizers in Canada. But prior to that, in order to register an enhanced efficiency product, it had to meet a specific definition,” says Rigas Karamanos, soil scientist in Calgary, Alta. Prior to his retirement,

ABOVE The need for an EEF nitrogen product depends on the 4Rs of fertilizer management.

Karamanos worked for many years at Westco Fertilizers and Koch Fertilizer, the current manufacturer of Agrotain.

The definition of an EEF came from the Association of American Plant Food Control Officials (AAPFCO). It reads: “Enhanced efficiency is a term describing fertilizer products with characteristics that allow increased plant uptake and reduce the potential of nutrient losses to the environment, such as gaseous losses, leaching or runoff, as compared to an appropriate reference product.”

Karamanos says that the current interest in EEFs is

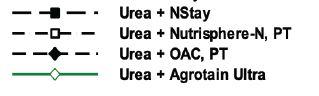

Ammonia loss from soil surfaces after treatment with granular urea or urea treated with various additives

not only related to reducing fertilizer N impact on the environment, but also in growers’ drive to reduce costs by increasing nitrogen use efficiency. “We have heard the expression ‘a pound of N is a pound of N’, which means that a pound of N that found its way into the soil, independently of what form it is at, will behave more or less the same. What influences whether products were ‘created equal’ depends on whether all products, once applied to the soil, provide the same pounds of N. That’s where EEF products have an advantage since they prevent gas emissions and leaching,” says Karamanos. “But a farmer should apply EEFs only when they generate a financial advantage.”

USING UREASE INHIBITORS

For nitrogen products, the three processes of primary concern for nutrient loss are volatilization,

denitrification and leaching. Volatilization occurs when urea N fertilizer (46-0-0) is broadcast on or shallow banded into the soil or when liquid urea ammonium nitrate (28-0-0) is broadcast sprayed to the soil surface. The urease enzyme reacts with urea and water resulting in the production of ammonia gas that is released into the atmosphere (volatilization).

Karamanos says volatilization potential is high when the fertilizers have prolonged exposure on the soil surface with little to no rain, heavy residue conditions and heavy dews followed by warm windy conditions. Research at Oregon State University looked at how much moisture was required to eliminate ammonia volatilization losses on a fine sandy loam soil. With no irrigation applied, 80 per cent of N was lost to volatilization. After applying 0.2 inches of irrigation, N volatilization losses dropped to about 35 per cent, and it took approximately 0.8 inches of irrigation to eliminate volatilization losses.

Treating urea with a urease inhibitor like Agrotain can slow the volatilization process to help reduce ammonium losses. Typically, urease inhibitors contain the active ingredient N-(n-butyl)-thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT).

Karamanos says there has been a lot of research proving the effectiveness of urease inhibitors. Research at North Dakota State University (NDSU) looked at different urease inhibitor products and found that not all products were equal. In one study published in 2011, broadcast urea treated with Agrotain Ultra had about one-half the losses compared to the other products.

The gold standard, though, for reducing volatilization losses is deep banding N fertilizer. Research in the 1970s found that deep banding anhydrous ammonia, a new-at-the-time N fertilizer source for Western Canada, provided higher yields than broadcasting other sources of N. At the time, John Harapiak of Westco Fertilizers, known as the father of deep banding, decided to compare deep banded urea to deep banded anhydrous ammonia. It turns out that deep banding urea also kept volatilization losses low if it was banded at least two and one-half to three inches deep.

Unpublished research by Cindy Grant, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist, also showed that deep banded urea had very low volatilization losses compared to the high losses incurred with untreated broadcast urea.

NITRIFICATION INHIBITORS

When urea or ammonium fertilizers like ammonium sulphate are applied to the soil, ammonium is converted to nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-) through the action

of enzymes found in soil bacteria and microorganisms. This is called nitrification. Nitrate is susceptible to leaching losses when moved downward in the soil or gaseous nitrous oxide (N2O losses) to the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that the federal government would like to reduce losses by 30 per cent.

Nitrification inhibitors act to reduce the enzyme’s oxidation action and prolong the presence of ammonium in the soil. Different active ingredients are used in different products.

Research at the University of Saskatchewan measured the denitrification losses for fall broadcast fertilizer N. Using 15N-labelled fertilizer, the research by one of Don Rennie’s PhD students found that about 35 per cent of fall-applied N was lost via denitrification, and seven to 20 per cent became immobilized by the following spring. Comparing zero tillage to conventional tillage, denitrification rates were much higher in zero tillage, and the population of denitrifiers was up to six times higher than in the conventional tillage fields. Crop residues also doubled gaseous N losses.

“They found out that up to 35 per cent of the nitrogen that was applied in the fall was lost due to denitrification because of the snowmelt in the spring. Isn’t that amazing?” says Karamanos.

Karamanos says that nitrification inhibitors are

“If you go back in history prior to April 1, 2013 – and that’s a not an April Fool’s joke – but as of April 1, 2013, we do not have any more regulation of efficiency for fertilizers in Canada.”

useful when nitrate losses can be expected due to nitrification. These include fall or early spring N fertilizer applications and slow spring snowfall melts. Irrigated fields are also at risk, as well as heavy textured wet soils and continually wet soils.

THE DEAL WITH DUAL INHIBITORS

Dual inhibitors have both urease and nitrification inhibitors. They prevent volatilization, leaching and nitrous oxide emissions. Research shows that dual inhibitors can also effectively reduce N losses. At NDSU, Jay Goos looked at the percentage of N remaining in the ammonium form four weeks after application on a sandy loam soil. Only 15 per cent remained in the ammonium form with bare urea, while 56 per cent remained after Instinct (nitrapyrin) and 71 per cent with SuperU (NBPT + DCD).

Karamanos says that growers should check the active ingredient for the concentration of the DCD denitrification inhibitor. To get maximum protection, the concentration of DCD needs to be around one per cent. He says SuperU is the only product that gets close at 0.85 per cent (8500 ppm).

Karamanos conducted research at eleven sites across the Prairies in 2015 and 2016 and found that fall broadcasting SuperU N fertilizer produced an average 13.5 per cent higher canola yield over untreated urea. The research also found that fall broadcasting SuperU had similar canola yield performance as deep banding untreated urea in the spring.

POLYMER COATED UREA

Polymer coated urea uses a polymer coating to slow the release of N. ESN is an example. Moisture is needed to enter the granule and dissolve the urea so the urea can diffuse through the coating. If not enough moisture is present, the urea is stranded and not available to the crop. For this reason, broadcasting ESN without incorporation is not generally recommended in Western Canada.

The right place where ESN can be used is when it is seed-placed during seeding. “That’s the absolutely best

CONTINUED ON PAGE 19 Examples of nitrification inhibitors and active ingredients

ENHANCED EFFICIENCY

BANDIT

(3, 4-dimethylpyrazole

Active Stabilizer Plus Active AgriScience NBPT (N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide) and DMPP (3, 4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate)

Anvol Koch Agronomic Services Duromide + N-(n-butyl)-thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT)

Arm U Active AgriScience N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT)

Arm U Advanced Active AgriScience NBPT (N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide) and DMPP (3, 4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate)

Centuro Koch Agronomic Services Pronitridine

Duo Maxx TIMAC AGRO Nitrogen, soluble potash, NBPT, DCD, Tryptophane, Rhizovit Complex

eNtrench NXTGEN Corteva Agriscience Nitrapyrin

nitrogen, 0.2% soluble potash, 0.8% NBPT, 0.2% DCD, 0.1% Tryptophane, Rhizovit Complex

ESN Nutrien Dry granular urea with a polymer coating 44-0-0

Polymer coated urea granule releases N by diffusion through coating when in contact with water. Release rate controlled by coating thickness, type and soil temperature (controlled release). Dry fertilizer granule

Excellis Maxx TIMAC AGRO NBPT, DCD, Rhizovit Complex 12% NBPT, 3% DCD, Rhizovit Complex Dual Mode Nitrogen Stabilizer Liquid

Humistart TIMAC AGRO Marine calcium carbonate with Calcimer with micronutrents 4-0-0-20Ca - 0.8%Mg - 4%S Soil Ammendment Granular

MicroEssentials SZ The Mosaic Company Monoammonium Phosphate with Ammonium Sulfate, Elemental Sulfur and Zinc 12-40-0 10S 1Zn Slow-release Dry fertilizer granule

MicroEssentials S10 The Mosaic Company Monoammonium Phosphate with Ammonium Sulfate and Elemental Sulfur 12-40-0 10S Slow-release Dry fertilizer granule

MicroEssentials S15 The Mosaic Company Monoammonium Phosphate with Ammonium Sulfate and Elemental Sulfur

Ostara Magnesium ammonium phosphate hexa-hydrate 7-33-0-9Mg 7% available total nitrogen (N), 33% available phosphate (P2O5), and 9% available magnesium (Mg) from magnesium ammonium phosphate hexa-hydrate

fertilizer granule

fertilizer granular

+ N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT) 46-0-0 Urease and nitrification inhibitor

TAPP Three ICL Single superphosphate, triple superphosphate, polyhalite, potassium chloride, magnesium oxide

TAPP Three S ICL Single superphosphate, triple superphosphate, polyhalite, potassium chloride, magnesium oxide

Top-Phos NP 3-28 TIMAC AGRO Complexed mono-calcium phosphate

Top-Phos NP 3-22 TIMAC AGRO Complexed mono-calcium phosphate with micronutrients

Top-Phos NP 15-20 TIMAC AGRO Complexed mono-calcium phosphate with micronutrients

TSN Taurus Agricultural Marketing NBPT (N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide) and DMPP (3, 4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate)

Dry fertilizer granule

Brought to you by:

Information compiled from fertilizer manufacturers. Follow the information on product labels and consult an expert if there are any discrepancies with the information in this table.

FERTILIZER PRODUCTS

RECOMMENDED USES

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN

Recommended for surface, shallow-placed, shallow-banded or shallow-incorporated (less than two inches) application of urea and urea-containing fertilizers.

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN

May be used with anhydrous ammonia, aqua ammonia, urea ammonium nitrate and other liquid ammoniacal or urea nitrogen fertilizers and liquid manure.

Treatment of granular or liquid fertilizers containing phosphorous and/or potassium.

PRODUCT BENEFIT

By minimizing nitrogen loss, it maximizes nutrient availability within the root zone, promoting healthier plant growth.

Controls ammonia volatilization and loss of nitrogen through nitrification from urea and UAN fertilizers.

Featuring dual active ingredients, Duromide and NBPT, Anvol provides long-lasting protection against ammonia volatilization over a wider range of soil conditions.

Allows plants to absorb more nitrogen which otherwise disappears too quickly through conversion to ammonia gas.

Inhibits ammonia volatilization, nitrification and denitrification. Contains polymers that increase the activity of NBPT and DMPP, enabling a lower percentage of active ingredient and a lower use rate while maintaining efficacy.

Delays nitrification of ammoniacal and urea nitrogen fertilizer by inhibiting the oxidation of ammoniacal nitrogen to nitrate nitrogen. Noncorrosive to the metals used in anhydrous ammonia and UAN equipment. Easy to handle.

It enhances nutrient efficiency through a dual-action approach: protecting phosphorus and other nutrients from retrograde tie-up and reducing nitrogen losses via volatilization and leaching while stimulating microbial activity in the rhizosphere to improve nutrient cycling and root uptake.

eNtrench NXTGEN is designed for use with UAN, liquid manure and dry urea. Protects nitrogen by keeping it in the root zone in a positive ammonium form longer so it’s available for plant use.

Any nitrogen fertilizer application.

The unique polymer coating protects and releases nitrogen at a rate controlled by soil temperature. ESN thereby supplies N to the crop at a controlled rate to reduce N loss, increase N-use efficiency and improve grower profit.

Treatment of granular or liquid urea based fertilizers (Urea, UAN, etc.). A nitrogen stabilizer containing the Rhizovit Complex, designed to enhance nutrient efficiency, improve nitrogen uptake, support root development, reduce nutrient loss and stimulate microbial activity for better overall plant growth.

All soil types, pH, replacing other phosphate soils.

Any nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur and/or zinc application.

Any nitrogen, phosphorus and/or sulfur application.

Any nitrogen, phosphorus and/or sulfur application.

Designed for use with anhydrous ammonia, N-Serve must be injected or incorporated in a zone or band in the soil with the fertilizer at a minimum depth of 5 to 10 cm.

Use in place of traditional phosphorus sources. Seed-safe and root-activated, allowing product to be placed directly in row with the seed.

Humistart-PhysioPro is a soil conditioner that improves nutrient uptake, promotes root development, enhances soil structure, increases microbial activity and supports plant growth through its high concentration of labile calcium.

The uniform nutrient distribution provided by MicroEssentials ensures product is delivered evenly across the field, providing crops an adequate chance of taking in key nutrients for season-long nutrition. By reducing the pH around the granule, the unique chemistry of MicroEssentials promotes interactions that improve nutrient uptake of P and S. In addition, MicroEssentials combines two forms of S, sulfate and elemental sulfur, in every granule to ensure S availability throughout the growing season. Sulfate sulfur satisfies seedlings’ needs for early-season growth, while elemental sulfur is available later in the growing season. Note: These products are not available in British Columbia.

Slows the conversion of ammonium nitrogen to nitrate nitrogen, which is more prone to loss from denitrification and leaching. N-Serve ensures that the nitrogen you apply is available when the crop needs it, helping to maximize yield.

P2X is a single-source, root-activated phosphate that delivers phosphorus, nitrogen and magnesium in direct response to root demand. Unlike conventional fertilizers that release with moisture, P2X only releases nutrients when roots exude organic acids—ensuring a steady, efficient nutrient supply throughout the season. Backed by Crystal Green technology, P2X stays in the root zone, resists tie-up, and maximizes uptake when it matters most.

Use in place of traditional potassium, sulfur or calcium/gypsum sources. Comprehensive four-in-one prill fertility supply, providing essential nutrients while enhancing efficiency.

Use in place of traditional potassium, sulfur or calcium/gypsum sources. Gradually releases four nutrients, providing essential nutrients while enhancing the efficiency.

Recommended to use in place of traditional gypsum or in place of traditional sources of plant-available calcium and sulfur.

Any nitrogen fertilizer application.

Provides a slow-release nutrient profile to deliver nutrients to plants throughout the season and deliver exceptional blendability, uniform spreadability and low-dust handling.

Premium fertilizer featuring urease and nitrification inhibitors to guard against all three forms of nitrogen loss.

Seed-safe starter blend fertility option for in the seed row. Just add nitrogen. Five nutrients in one prill offering seed-safe, plant available nutrition that feeds the plant all season.

Seed-safe starter blend fertility option for in the seed row. Just add nitrogen. Five nutrients in one prill offering seed-safe, plant available nutrition that feeds the plant all season.

All soil types, pH, replacing other phosphate soils.

All soil types, pH, replacing other phosphate soils.

All soil types, pH, replacing other phosphate soils.

Protects liquid urea-based fertilizers from ammonia volatilization, leaching and denitrification. It can be used for any crop that requires nitrogen fertilization.

Any nitrogen fertilizer application.

Top-Phos is a proprietary phosphorus fertilizer designed for high solubility, efficient uptake and consistent performance across all soil pH levels. With a low salt index, sustained nutrient release and positive interactions with soil microbes, Top-Phos delivers smarter, longer-lasting phosphorus nutrition.

Proprietary nitrogen-phosphorus fertilizer, combining N-Process and TOP-PHOS technologies, for effective performance across a range of soil pH levels, positive microbial interactions, etc.

Dual active ingredients NBPT, the most research-proven urease-inhibitor technology, and the patented active ingredient Pronitridine, safeguard nutrients from volatilization, leaching and denitrification.

TSN is treated with urease and nitrification inhibitors to reduce volatilization, leaching and denitrification. With NBPT and DMPP working together, TSN improves nitrogen use efficiency and keeps more nitrogen available for your crop.

4-in-1 Polysulphate® consistently delivers seed-safe, gradualrelease potassium, sulfur, magnesium and calcium.

• Improve soil health

• Reduce nutrient loss

• Achieve higher yields

Fertility That Delivers.

Flexibility That Works. Learn

Where do enhanced efficiency fertilizers fit?

fit of polymer coated urea or ESN in our environment. You can add three to four times the safe rate when placing ESN with the seed,” says Karamanos.

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER

EEFs fit into fertility plans when viewed through the 4Rs of fertilizer management: Right place, time, rate and source. Karamanos says that growers don’t need to use an EEF N product if the right combination of the 4Rs are in place.

When it comes to the right place, Karamanos says deep banding (placing at >2.5 inches depth) is the golden standard when placing N fertilizer and urea in particular. This is because of increased resistance to the upward diffusion of ammoniacal N in the liquid and gaseous phases. “Know your fertilizer placement depth. If it’s not deep enough, then stabilize,” says Karamanos. Broadcasting or shallow banding fertilizer require stabilization with a urease inhibitor unless a significant rainfall is expected. When it comes to the right rate, application rate can be reduced by 20 to 30 per cent to receive the same result, says Karamanos. He conducted research comparing spring broadcast, shallow band and deep

banding of urea at 70 and 100 per cent of recommended rate, urea plus Agrotain and urea plus SuperU. He found that an EEF N fertilizer applied at 70 per cent of recommended rate provide the same canola yield as urea at the 100 per cent rate.

“Reduced rates of N should result in the same yields or, if losses are significant, the same rates should result in higher yields. Therefore, this will result in an economic benefit,” he says.

With the increased size of farms, some in tens of thousands of acres, operational efficiencies take priority, and that affects the time (and place) of application. “Moving application to the fall, commonly broadcasting, increases the probability of both volatilization and denitrification losses. EEFs play a very important role in minimizing these losses,” says Karamanos.

When it comes to the right source, it’s important to consider volatilization inhibitors when potential for volatilization is high, as well as nitrification or dual inhibitors when nitrate losses can be expected due to nitrification, typically with fall or early spring applications. “There is no single ‘best’ fertilization system,” says Karamanos. “Every farm, field and year has unique demands, resources and conditions.”

“Enhanced efficiency is a term describing fertilizer products with characteristics that allow increased plant uptake and reduce the potential of nutrient losses to the environment, such as gaseous losses, leaching or runoff, as compared to an appropriate reference product.”

Source: AAPFCO

Optimizing

inhibitor) and Environmentally Smart Nitrogen (ESN; polymer coated urea). Nitrogen timing treatments included 0-N control, all N side-banded at planting, 30 per cent side-banded at planting plus 70 per cent broadcast in-crop in late fall (split-applied late-fall), 30 per cent side-banded at planting plus 70 per cent broadcast in-crop in early spring at approximately the Feekes 4 growth stage (split-applied early-spring).

Nitrogen fertilizer application rates were based on 80 per cent of the recommended soil test rates to optimize detectable responses on the upward slope of the N response curve. These rates ranged from 65 to 187 lb. N/ac. (73 kg N/ha to 210 kg N/ha) for the irrigated sites and from 55 to 157 lb. N/ac. (62 kg N/ha to 176 kg N/ha) for rain-fed sites.

Under irrigation, Beres found that yields were similar for the N timing and placement treatments. SuperU had the highest grain yield that was 3.9 per cent higher than eNtrench, 4.3 per cent higher than untreated urea and 4.7 per cent higher than ESN.

On the dryland sites, no differences in time of application occurred between split-applied early-spring and

ABOVE The fertility trial plot at WADO shows variability.

split-applied late-fall. Yield was statistically highest when all N was side-banded at planting. High stable yields were achieved with all N sources when all the N was side-banded at planting, except for ESN which had elevated yield stability.

The SuperU split-applied early-spring provided the statistically highest grain yield on both irrigated and dryland sites.

LIQUID UAN RESULTS

Another study conducted from 2013 to 2018 at similar sites as the urea research also looked at the 4Rs of winter wheat fertilization. This study looked at six N sources, including untreated granular urea (46-0-0 ), untreated liquid urea ammonium nitrate (UAN; 28-00), Agrotain Ultra treated UAN (urease inhibitor), eNtrench treated UAN (nitrification inhibitor), Agrotain Plus treated UAN (urease inhibitor plus nitrification and ESN; polymer coated urea).

UAN placement/timing treatments were 50 per cent of N side- or midrow-banded at seeding, and 50 per cent applied in-crop in early-spring (Feekes 4). ESN was

100 per cent side-banded at planting, and the untreated urea was applied at full rate broadcast in early spring. Nitrogen rates were again based on 80 per cent of recommended soil test rates, and rates were similar to those used in the urea study.

Under irrigated conditions, the UAN treated with a urease inhibitor (Agrotain Ultra), untreated UAN and the urease plus nitrification inhibitor (Agrotain Plus) had statistically similar yields around 75 bu./ac. (5.06 t/ha). Agrotain Ultra treated UAN was statistically higher than untreated urea by 6.4 per cent, by eight per cent over the nitrification inhibitor (eNtrench) and by 14 per cent over ESN.

Dryland yields with untreated UAN, untreated urea, urease inhibitor-treated UAN and dual treated urease-plus nitrification inhibitor were statistically similar at around 65 bu./ac. (4.36 t/ ha). The statistically lowest yielding treatments were the nitrification inhibitor-treated UAN at 63 bu./ac. (4.25 t/ha) and ESN at 63.8 bu./ac. (4.28 t/ha).

“Enhanced efficiency fertilizers can play a role and often pay for themselves even in modest yield environments. We have also observed improved yield stability with them,” says Beres. “So, the utility or context of whether or not to adopt an EEF might range from insurance against loss or yield instability to significantly higher yield in certain environments.”

NEW STUDY IN MANITOBA

Ducks Unlimited initiated a research study in 2022 that ran for three years at Melita, Roblin, Carberry and Arborg, Man. for a total of 11 site-years. The fertilizer rates applied were 54, 80, 107, 134 and 161 lb./ac. (60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 kg/ha).

These rates were applied 50 per cent in the fall as a 50:50 blend of ESN and urea mid-row banded and the remaining 50 per cent broadcast urea N treated with Agrotain urease inhibitor. An additional treatment was 107 lb./ac. Agrotain-treated urea spring-applied. The treatments were not adjusted for soil test values but, across all of the sites, soil residual N was between 23 to 36 lb. N/ac. at every site.

Wildfire and Vortex varieties were compared for their response to the N treatments. “The uncertainty of the extremely wet or bone-dry springs makes the timing of your N fertility crucial, as

“Enhanced efficiency fertilizers can play a role and often pay for themselves even in modest yield environments.”

we’re so rarely in that Goldilocks zone,” says Alex Griffiths, an agronomist with Ducks Unlimited.

Griffiths says that it is crucial that N is plant available by the fifth leaf stage in the spring. He says this is when seed heads are starting to develop, and that N applied later will go towards protein or vegetative growth, not yield. “I usually recommend about 40 to 50 per cent of your nitrogen down in the fall [...] to help manage your risk,” says Griffiths.

Averaged across the 11 site-years, the split 150 treatment was consistently the highest yielding at 88 bu./ac., but was statistically the same as the split 180 or either of the split or spring 120 treatments. There were differences in N response at the different sites and years.

In 2022, there were dramatic differences at Melita and Roblin, when heavy spring snow and rain produced the highest yield at the 100 per cent spring applied N. “We definitely suspect that there was nitrogen leaching from the fall applications with the late winter, early spring, heavy precipitation, especially on a sandier site like Melita,” Griffiths says.

2023 was a much drier year and, at three sites, there was no yield differences for the N treatments. At Melita, the 120-split had the highest numerical yield at 76 bu./ac., but was similar to the split 90, split 150 and split 180 treatments. The spring N treatment was lower yielding, and Griffiths says that the application timing on May 11 was probably too late to benefit the yield response.

Griffiths says that 2024 was an average year weather wise, with all sites producing similar trends. The

120-, 150-, 180-split and 120-spring all yielded statistically similar in the 85 to 90 bu./ac. range.

An economic analysis was conducted on the 11 siteyears of data using $8/bu. winter wheat price and 80 cents/lb. of added nitrogen. The split 120 treatment had the highest return on investment of $70.93. This was followed by spring 120 at $64.31/ac., split 150 at $62.42/ac., split 60 at $56.62 and split 90 at $54.00/ ac. The split-180 treatment had the lowest return at $28.43/ac.

“This again confirms that once you’ve applied that 120, you’ve not only reached your max yield or close to it, but you’ve also reached your highest return on investment as well,” says Griffiths. “And one thing that I didn’t include when doing this calculation, but should be noted, is that oftentimes your fall-applied nitrogen is actually a fair bit cheaper than spring prices so you can potentially save some additional dollars there while guaranteeing availability and beating the spring rush at the same time.”

Overall, the research studies show that there isn’t any ‘one size fits all’ farms. The success of a N fertility program depends on multiple environmental and soil factors. “To a large extent, water and temperature combined with soil type, texture and organic matter drive N mineralization rates. Strategies should be tailored to an environment with this in mind and also the precipitation accumulation to date,” says Beres. “Yield potential should dictate the timing and placement strategy, and the potential for loss should dictate the N source.”

If you want a free hat, we have those too. We work with you to secure the right seed for your operation’s success, supported by personalized agronomic solutions at every stage of the season.

Every drop counts

Researchers explore subsurface drip irrigation for broadacre crops.

BY JOEY SABLJIC

Water efficiency is a game of inches. Growers in irrigation districts are allotted a certain amount of water – usually around 18 inches – to get their crops through the season. However, in drought years, that allotment might be as low as eight or 10 inches, bringing even greater pressure to irrigate as efficiently as possible.

Researchers from Lethbridge Polytechnic – led by Willemijn Appels, Mueller applied research chair in irrigation science, are going in-depth on subsurface drip irrigation (SDI) systems to understand whether they can deliver greater water use efficiency over industry-standard pivot boom systems.

“The severe drought conditions we’ve seen over the past five to seven years really have people wondering what are the possibilities,” says Appels. “I think it’s timely that we look into these things now so we can ensure not only that we’re using water as efficiently as possible, but irrigated agriculture is sustainable well into the future.”

TO STAY ABOVE OR GO BELOW

Appels points out that subsurface drip irrigation is not a new concept – being commonly used on smaller-acre specialty vegetable crops. However, SDI is a new idea for broadacre crops like wheat and canola.

The biggest hurdle, historically, has been the upfront work and cost involved in burying irrigation equipment beneath the soil surface, as opposed to building an overhead pivot. There’s also the fear that those buried irrigation lines might accidentally get hit during tillage. According to Appels, RTK guidance and minimum till systems all but eliminate the risk.

WHY CONSIDER SUBSURFACE IRRIGATION?

The question remains: Why would broadacre growers want to trade in their centre pivot for a subsurface system? After all, centre pivot is an industry-standard,

ABOVE Subsurface drip irrigation system in field peas.

proven technology.

The biggest issue, says Appels, is that pivots don’t allow growers to fully fine-tune water delivery to plants. “If you think of getting to the ‘next level’ of reducing water losses from the irrigation system, there’s not so much left to do,” she explains. “You can finetune some nozzles, but if you have high wind and sunshine, any water that gets trapped in the crop canopy will evaporate and not reach the ground.”

The working assumption is that centre pivot systems are about 85 per cent efficient at reaching the soil. While this may seem reasonable, that extra 15 per cent does matter. “If you’re in an especially dry and warm season where you don’t get much rain, that extra 15 percent is like gold,” says Appels. “So, then you start thinking not only about how to use your water best, but where to apply it.”

In a centre pivot system, growers should ensure water is applied into the crop canopy and on the soil surface. It then eventually moves into the soil and

COMBINE PRIME TIME.

Reap next year’s rewards and get 2026 John Deere Harvesting Equipment at the best possible price with the Early Order Program at Brandt!

More Savings

Order early for the largest discounts and no financing payments until the machine is delivered to you. *

More Productivity

‘26 models feature predictive ground speed automation, a 3-piece CAM reel Draper for better crop feeding.

Reserve your 2026 John Deere Harvesting equipment today! Visit your local Brandt Agriculture dealer or go online:

Superior Support

With 24/7/365 support, more parts, local experts, and personalized deals, we work for your best interest.

slowly makes its way down to the root system. With SDI, water is injected almost directly into the root system 10 to 12 inches beneath the soil surface, and evaporation and potential runoff are minimized.

Appels and her team suspect that this would boost the plants’ ability to survive heavy drought conditions and find whatever moisture might be buried deep. “Where you put your water, and how you do that during crop establishment determines later in the season how the plant will be able to tap into moisture,” says Appels.

The researchers will be exploring how much crop they were able to produce per drop of pivot and SDI-irrigated water. They’re also measuring evapotranspiration, or the amount of water that turns into vapour from the plant and soil surfaces.

MANAGING THE POTENTIAL PITFALLS

One thing to keep in mind when looking at SDI is the direction that water travels. Normally, a grower would try to germinate a crop with small applications, such as a quarter inch on the soil surface every three or four days. In an SDI system, however, you’re trying to make water travel upwards to the soil surface – and adding a quarter inch won’t cut it.

Because most of the action is taking place underground, it can also be difficult for growers to see an immediate, obvious impact after irrigation.

“If you can’t see what you’re doing, you can mismanage water. If you put in too much water in one go or over time, and your soil was quite wet to begin with, you run the risk of creating a downward pipeline, and leaching,” Appels explains.

IMPLEMENTING SDI

A potential benefit for subsurface irrigation comes down to geography – or, rather, the shape of land. “There have always been oddly shaped parcels of land where the circular pivot just doesn’t hit and can’t irrigate,” she says. “So, our thinking is that those areas could be a much better fit for SDI, if growers wanted to try out the technology on limited acres.”

Appels also observes that SDI systems – like centre pivots – allow canals to be transformed into water pipelines that help trap and recirculate water, as well as prevent leaching, seepage and evaporation.

She sees opportunities for SDI to be implemented as growers continue to expand and convert their dryland acres to irrigation. “There is plenty of water to go around at this point - but not everywhere and not all of the time,” says Appels. “I think a lot of our work with SDI is about being prepared for when we might see bigger water restrictions in the future and need to be as targeted and efficient as possible.”

MICROWAVE RADIOMETRY TECHNOLOGY CREATES “WATER MAPS” OF SOIL

Alongside their water efficiency work, Appels and her team are also looking at the use of microwave radiometry technology to create “water maps” of soil. The idea is to take much of the guesswork out of irrigation and show growers where the biggest pockets of available moisture are throughout their fields.

“We want to know in detail how much water is available to the plant and how much water that plant is using throughout different growth stages,” says Appels. “So, we’re always looking for the best tools to help us do that.” She adds that microwaves are thought to penetrate deeper into the soil profile and provide data that is more related to soil moisture, compared to other remote sensing bandwidths.

Typical moisture sensors, on the other hand, can’t be easily moved around and they only provide one data point, when soil moisture can be highly variable from one part of the field to the next.

With microwave radiometry technology, a sensor would be mounted directly on a centre pivot boom to scan the field to create a moisture map. This, says Appels, could allow growers to implement variable-rate irrigation so that they’re not over-applying in areas with plenty of available water.

20, 2025

Grande Prairie, AB

For the first time, Top Crop Summit is expanding beyond Saskatoon with a NEW second event in Alberta’s Peace Region. Designed for growers, agronomists and crop advisors, the summit delivers expert agronomy research, insights, and production strategies tailored to the Peace Region—helping you make informed decisions and boost productivity next season.

Rate:

Growing teff on the Prairies

Teff could be an option as both a cereal and a high protein forage crop.

BY ADELINE PANAMAROFF

Teff, a cereal grain originating from northeast Africa, has many desirable qualities: high protein content, great carbon fixing in soil, the ability to withstand dryer conditions and the ability to self-pollinate. It also performs well in soils with low fertility. Beginning in 2020 and 2022, multiple research projects are trying to determine the feasibility of growing teff on the Canadian Prairies.

Used as a flour in Ethiopia and Eritrea since 4000 BCE, teff has a growing habit similar to millet with slender stocks and a smaller seed head. In the United States, it’s been a regular component in cover crops, and the hay is commonly grown for the equestrian market in the U.S. - and to a small extent in Canada. However, James Frey, applied research specialist at Parkland Crop Diversification Foundation (PCDF) near Roblin, Man. was first introduced to teff as part of a forage mix.

CROP DIVERSIFICATION TESTING IN MANITOBA

Starting research on teff in 2020, focusing on its value as a forage crop, Frey accidentally discovered that the harvested plants had developed grain. “It was getting towards the end of September and I rubbed it out in my hands and realized, oh, wow, there’s actually grain in here,” Frey says.

He thought the seed might have been too immature to be viable, but his team combined the crop, just to be thorough. In 2022, they began tests to determine its

TOP A close-up of teff grain. ABOVE Teff varieties in a field.

value as a cereal crop. “We jumped in initially just thinking this would be a good forage option and assumed that it was too much of a long season crop to grow for grain,” Frey says. Now working with 13 different varieties, obtained from a variety of sources including the Saskatoon Research and Development Centre, PCDF is continuing its testing to look at seed yield.

CULTIVATION CHALLENGES

Frey has discovered that seeding teff can be a challenge since it needs to be seeded or broadcast no deeper than a quarter inch to germinate quickly, at the rate of five pounds of seed per acre. “Farmers would be familiar with how to get a small amount of seed onto their

fields,” says Frey, “but it’s just important that it is at the right depth.”

Harvest also presents some challenges. While teff has similarities to millet, its seed size is much smaller.

“It’s very, very easy to lose seed out the back of the combine,” says Frey. Appropriate combine settings are comparable to settings for Timothy seed, which has a similar size and density. One pro to harvesting teff is that it’s not prone to shattering.

The small size of the grain could be an issue for weed management, too. With similar sized seeds of common weeds like redroot pigweed, mixing could be an issue.

“Effective weed management will play a pivotal role in determining the successful cultivation of teff in Alberta,” says Shabeg Briar, research scientist at the Olds College Centre for Innovation (OCCI).

The herbicides that are available are limited to broadleaf weeds, but can take similar treatments to oats, adds Frey.

ALBERTA TESTING AT OLDS COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY

Bira Biro Import & Export Enterprise Ltd., based in Edmonton, has been collaborating with Olds College of Agriculture & Technology since 2022 to conduct its own research project on the feasibility of growing teff on the Canadian Prairies. Led by Briar and funded through the National Research Council of Canada Industrial Research Assistance Program (NRC IRAP), Prairies National Research Council Canada and the Government of Canada, this project is in its third year of growing teff in small trial plots, testing growth of the grain and analysing its value as forage.

Briar first conducted a potted greenhouse study with three unregistered teff cultivars, provided by Bira Biro in 2022. “Building on the outcomes of [this] preliminary research […], the subsequent exploratory field study in 2023 aimed at the evaluation of two of the

most promising cultivars,” Briar says. The trial plots were arranged in randomized complete block designs, in four recreated sets, to see if the results could constantly be replicated.

During the 2024 growing season, Bira Biro supplied four more teff cultivars, with another being provided by Union Forage, to do larger trials to measure grain yields and forage yield and quality. The results of that season’s study concluded that teff was a viable grain for Central Alberta. “This is an imperative attribute to facilitate commercial-scale production in Alberta, hopefully in the near future,” Briar says.

For forage, teff looked to be a great producer, doing well in the dry conditions that could be persistent in the region. The lab results came back showing that teff has adequate levels of calcium, potassium and magnesium, supporting skeletal health, metabolism and overall livestock health, Briar concluded.

In his discussions with them, Frey has seen interest in teff production from local farmers in Manitoba. His contacts have tried growing the grain on approximately 20 to 100 acres. The key to gaining interest is to let the producers know that teff is a niche crop – and will remain niche for many years to come. This means that the market requires direct contact between the producer and the seller.

MARKET OPPORTUNITIES FOR TEFF

The market shows promise in two areas. There continues to be a growing population of new Canadians from northern Africa who want to continue to consume teff as either a whole grain or as flour here in Canada. While teff is currently being imported from African markets, local production of teff would find a foothold within this demographic. There is also opportunity to export teff internationally, especially to the United States, Europe and Africa. As a gluten-free grain, teff could be an option for speciality food markets, where consumers of gluten-free options would benefit from another choice on grocery shelves.

While there’s still plenty to learn about the growth habit of the plant, teff could be a promising alternative as both a cereal and a high protein forage crop for producers. Given its ability to grow in hot weather and withstand dry conditions, it’s another option in the face of ongoing climate challenges. For entrepreneurial minded farmers with direct marketing connections, it could be yet another value-added stream. All in all, the potential for teff is only beginning to be realized in Canada.

Alberta farmers are mixed in readiness for succession planning

Succession readiness impacts which resources are effective.

BY KAITLIN BERGER

Succession planning seems like a good idea, especially given the average age of farmers in 2021 was 56 years old, according to Statistics Canada. It’s safe to assume this could mean seeing one of the biggest transfers of farmland ownership and farm leadership in the next ten or fifteen years in Canada. This begs the question: Why did only 12 per cent of farms have a succession plan in 2021?

While there are extensive tools and resources available to help farmers with succession planning, relatively few people are using them. Rebecca Purc-Stephenson, professor of psychology at the University of Alberta and lead researcher and founder of agwellAB, recognized there are stages of readiness for people who are adopting change. “We’ve all probably wanted to start exercising, right? But if you’re not even interested in that, you’re not going to start a program,” she says. “But if you’ve been thinking about it and you’re motivated [...] you’ll be more successful.” Identifying individual readiness for succession planning ensures that people are being directed to the right resources.

This led Purc-Stephenson to conduct research on Alberta farmers’ readiness for developing a succession plan – the barriers and facilitators. The research included interviews with 35 participants from 16 farm families.

ABOVE Next generation harvester.

During this research, it was important to interview more than one member of the family because each family member could be at a different stage of readiness. It also gave the researchers critical information about the communication dynamics around the topic of succession planning – and often a lack of communication. “From the farm successor perspective, they often didn’t talk to their parent about taking over the property or the farm, but would do things to prove their worth to them in hopes that they would be identified as the successor one day,” says Purc-Stephenson. Even among farm owners, especially when it was a husband/wife partnership, there was disagreement on how farm succession should proceed. One participant, a successor from family J, was quoted in Purc-Stephenson’s research paper Understanding Farmers’ Readiness to Develop a Succession Plan: Barriers, Motivators, and Preliminary Recommendations: “I think it varies between my mom and my dad. My mom’s priority is that me and my sister stay on good terms, and everything is split

SMARTER SOLUTIONS FOR MAXIMUM YIELDS

Enhance nutrient use, improve plant health, and increase yields with biological solutions from FMC. Our advanced microbial technologies and nitrogen-fixing bacteria work together, helping crops thrive, no matter the soil conditions. Each solution is specifically designed to bring out the best in your crops.

fairly. My dad’s priority is keeping the farm intact so it’s viable for the next generation.”

SEVEN BARRIERS AND MOTIVATORS FOR SUCCESSION PLANNING

Naturally, family dynamics was one of seven barriers and motivators the research identified. Purc-Stephenson suggests the family dynamics around succession planning would be improved if everyone remembers that “fairly doesn’t mean equal” - not to mention the importance of setting boundaries between family events and farm discussions. “The farmers that were doing really well in succession planning, they would set aside meetings where they would talk about the farm and they would keep that completely separate from their own family issues,” she adds.

Legacy and identity were also included among the seven barriers and motivators. More than other occupations, farming can be tied to personal identity. Purc-Stephenson reminisces on an interview with a 90-year-old farmer who was still actively involved in farming and was in discussion about passing the farm to his grandson. He was hesitant to proceed with succession planning, because he felt his role on the farm would be eliminated. He associated it with moving to town and watching his health decline. “Those who have passed the farm on made space to talk about how they can have a role at the farm, maybe doing the things that they really like to do,” says Purc-Stephenson.

Declining physical health also played a key role in being motivated to make a succession plan. “[My dad] had farming in his blood and he worked right up until he just physically couldn’t anymore,” says one successor from Family K. Some interviewees expressed they didn’t feel a need to have a succession plan when they’re still able to farm themselves.

Many families want to wait to see what will change with government policies surrounding capital gains tax, inheritance tax and land transfer rules. “This belief that they are shifting or government’s going to take money really was a barrier for many farmers to start the process. So, they wanted to wait to see what was going to happen,” says Purc-Stephenson. That’s why having professional guidance was another important motivator, to clarify government policies and meet the demands of the more complex landscape of modern agriculture.

Farm culture norms, especially the expectations for retirement age, also have a significant impact on making a succession plan. “The same metrics that we use in other industries for retirement age being 65 doesn’t often apply to farmers,” says Purc-Stephenson.

Farm growth was also a strong motivation. “If there were plans to expand the farm or to grow, and we see this often with grain farms or crop farms, there can be at stake, a lot of risk, so they would try to ensure that their kids were set up or they were protected. A succession plan was one way to do that.” If it was a smaller operation, there was less motivation for a succession plan because there was doubt about its viability to support multiple generations.

FOUR READINESS LEVELS

After identifying these seven motivators and barriers, Purc-Stephenson narrowed down two overarching variables for starting succession planning. Perceived risk for either creating or not creating a plan and comfort levels surrounding having a conversation about it.

She then separated these variables into four quadrants. Active Planners included farmers who believed there was more risk without a plan and they were comfortable starting the conversation about it. “Those were the fewest, but those were folks who, maybe they had a large operation, they wanted to expand, they had good family relations, they had a team, they understood the policies, and they were actively engaged with a plan in place,” says Purc-Stephenson.

The two largest groups were Succession Avoiders and Back Burners. The avoiders knew there was risk without a plan, but they didn’t want to have conversations about it. “Many stated ‘I’m going to keep farming until I can’t anymore.’ Most had a will and assumed their kids would ‘figure it out’ when they passed,” says Purc-Stephenson. Back Burners often had good family relationships and didn’t want to rock the boat.

End-of-the-Line Farmers didn’t think there was much risk from not having a succession plan and didn’t want to initiate conversations either. These were often individuals with smaller farms who assumed their children wouldn’t take over the farm.

When Purc-Stephenson started this project, her goal was to come out of it with not only data, but also

tangible applications. There are plenty of resources already out there to help farm families with succession planning, but the results from the study highlighted why people often aren’t using them. “I think that there was an assumption that, just give people the information and they’ll do it,” says Purc-Stephenson, “but we know from psychology that our attitudes about something doesn’t always translate into behavior. We need to meet people where they’re at.”

The next step is to expand the research nationally –and gather more information. In the meantime, however, Purc-Stephenson is ensuring farm advisors know how to recognize the readiness levels in succession planning so they can give the appropriate recommendations. She also says succession planning needs to be regularly included in extension programs, and that government and industry should consider reducing the cost barriers.

“Succession planning needs to be discussed more often and it’s something that farmers can actively work towards,” says Purc-Stephenson, “again knowing that it’s not a one-and-done process, but it’s this ongoing process, and people need practice to know how to talk about it.”

“Those who have passed the farm on made space to talk about how they can have a role at the farm, maybe doing the things that they really like to do.”

25_007004_Top_Crop_Western_Edition_SEP_CN Mod: June 11, 2025 4:01 PM Print: 06/30/25 page 1 v2.5

by Bruce Barker, P.Ag | CanadianAgronomist.ca

Manage canola harvest to optimize winter wheat production

With the shift to straight cutting of later maturing canola hybrids, there was a need to update winter wheat management practices in a canola-winter wheat rotation.

The objectives of this study, led by Brian Beres, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), were to investigate how early- and late-maturing hybrid canola and harvest timing impact the subsequent winter wheat crop. Additionally, the research also tested winter wheat herbicide applications while simultaneously windrowing canola.

Field experiments were conducted near Lethbridge and Lacombe, Alta., Indian Head and Saskatoon, Sask., and Brandon, Man. from 2018 to 2022 for a total of 16 site-years. Two canola hybrids with pod-shattering reduction traits were compared: InVigor L233P (early-maturing) and InVigor L255PC (late-maturing). AAC Wildfire was the winter wheat variety used in the study at all locations.

The three harvest timings included early windrowing performed at 40 per cent seed colour change (early timing), conventional windrowing performed at 60 per cent seed colour change (conventional timing) and straight cutting at 10 per cent seed moisture (straight cutting).

The weed management treatments included pre-harvest herbicide in canola (pre-harvest), pre-plant herbicide for winter wheat (pre-plant) and pre-harvest plus pre-plant herbicides (pre-harvest plus pre-plant).

The pre-harvest herbicide was a tank mix of Heat LQ herbicide (saflufenacil) plus glyphosate applied during the windrowing operation using an on-board sprayer. For the straight-cutting treatment, the pre-harvest herbicide was applied at 60 per cent seed colour change. The pre-plant herbicide was Focus (pyroxasulfone) applied as a pre-seed burn-off treatment prior to winter wheat seeding.

In this research, straight-cut canola yielded similar to windrowed canola. However, it reduced the subsequent winter wheat crop yield by 4.9 per cent compared to the early-windrow treatment and by 4.3 per cent for the conventional windrow timing. The research suggests this may be attributed to lower soil moisture availability following straight-cut operations. Early and conventional windrow timing had similar winter wheat yields in the subsequent crop.

Winter wheat yield was 2.2 per cent higher when a pre-harvest herbicide application was conducted compared to a pre-plant only fall application. A combined pre-harvest plus pre-plant residual herbicide application resulted in a 3.8 per cent winter wheat yield increase compared to a pre-plant only application.

The application of a pre-harvest herbicide was effective in controlling broadleaf weeds in the fall. The combined pre-harvest plus pre-plant residual herbicide controlled grassy weeds in the fall and broadleaf weeds in the spring. This was consistent for both the early- and later-maturing varieties.

On the other hand, a pre-plant herbicide only application with either conventional windrowing or straight cutting slightly reduced the succeeding winter wheat grain yield. This highlights the importance of a pre-harvest herbicide application in the canola crop preceding winter wheat, which – if performed simultaneously with canola windrowing – eliminates an operational pre-seed step from the winter wheat system.