ON-FARM research expanding

FOR THOSE WHO CHOOSE THE TRIED AND TRUE

Why more farmers trust InVigor hybrid canola.

Season after season, you count on InVigor® hybrid canola to help you maximize yields.

We appreciate that you’ve made InVigor Canada’s most trusted canola seed, and it’s a responsibility we don’t take lightly. For 2025, we’re proud to add three new early-maturing hybrids to our lineup – all of which give you consistent performance, clubroot resistance, and patented Pod Shatter Reduction technology.

For more information, contact BASF AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) or visit agsolutions.ca/InVigor.

Always read and follow label directions.

Mind your ‘Ps’ and ‘Ns’ and ‘Is’ when it comes to lentil fertility in the Brown, Dark Brown and thin Black soil zones. Phosphorus (P) can be a limiting nutrient in lentil production, but nitrogen (N) and inoculants can also affect lentil yield and profits. A recent Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture ADOPT (Agricultural Demonstration of Practices and Technologies) project looked at these three fertility inputs and how the latter two interact to impact production.

Evaluating trial results from 2023.

Agronomy can take advantage of changes.

Keeping cropping systems resilient.

Improving canola varieties.

Struvite is safer but with lower canola yield.

by Kaitlin Berger

Rolling Up My Sleeves

As a kid, I was obsessed with checking the mail. I’d often volunteer to walk down the long gravel laneway on my parents’ farm to the heavy-duty mailbox our neighbour made from steel pipe – a necessity given how many times it was taken off the post by a snow plough or a gang of thrill-seekers with baseball bats. As long as I can remember, Top Crop Manager would regularly show up with the stack of letters, bills and local flyers. At one point, my dad told me it was a good magazine to start reading if I wanted to write about agriculture one day.

Spoiler alert: I took his advice. I recently joined Annex Business Media as the editor of Top Crop Manager – West. My introduction to agriculture was on a pig and crop farm in southwestern Ontario, where I was surrounded by fields of soybeans, corn and winter wheat. I moved to Alberta a few years ago to take in a different landscape – lots more yellow flowers and even bigger fields.

Having been immersed in agriculture for the first seven years of my career as a copywriter and journalist, I’m endlessly amazed by how much there is to learn in this incredible industry. As I was reading through the articles included in this issue – Bruce Barker’s article on how agronomy could help feed a growing global population on page 8, for example – I was reminded of just that.

The challenge of working in agriculture, whether you’re a farmer or an agronomist or even a writer like me, is that the industry is constantly changing.

The challenge of working in agriculture, whether you’re a farmer or an agronomist or even a writer like me, is that the industry is constantly changing. There’s new technology to implement, new governmental policies to consider and the endless fluctuation of weather conditions and grain prices. A lot of those things are also what make new research – like the story of one researcher’s approach to countering blackleg resistance on page 20 – so exciting. There’s a lot to look forward to as research progresses, and agronomic insight develops.

The good news is we’re in it together. As harvest commences for 2024, I’ll be rolling up my sleeves too. My goal is to continue the Top Crop Manager legacy of providing trusted insight on current agricultural research and innovation. I want to share the stories that matter to you, so please feel free to reach out if you see me at any upcoming events or find my information on the website to send me an email or give me a call.

And don’t forget to check the mail. You never know when the next issue will be waiting for you.

September 2024 | Volume 50 | Number 6

Reader Service Print and digital

inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Administrator Tel: (416) 510-5113 | Fax: (416) 510-6875 Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor KAITLIN BERGER (403) 470-4432 kberger@annexbusinessmedia.com

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager SERINA DINGELDEIN (416) 510-5124 sdingeldein@annexbusinessmedia.com

Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW

CEO SCOTT JAMIESON sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

in Canada ISSN 1717-452X PUBLICATION MAIL

by Acadian Plant Health

The power of biostimulants: A key to climate-smart agriculture

The farming landscape constantly evolves, presenting new challenges each year. Erratic weather conditions especially impact farming and plant health. Growers must explore effective crop management methods to weatherproof crops, enhance production, and meet market demands.

Climate-smart agriculture provides innovative strategies to boost productivity while tackling crop stress and other climate-related challenges. Climate-smart agriculture focuses on three pillars: increasing productivity, enhancing resilience to climate change, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This approach helps create sustainable agricultural systems that adapt to challenges posed by shifting weather patterns.

Acadian Plant Health™ (APH) biostimulants play a role in this plant health strategy by stimulating growth, improving nutrient uptake, enhancing tolerance to abiotic crop stress and boosting soil health.

PURSUING CLIMATE-SMART AGRICULTURE

Acadian Plant Health’s biostimulant research reveals positive effects on plants’ nutrient use and efficiency, root absorptive function, and dissolved macro and micro-nutrient uptake.

“Our studies have shown that applications of our Ascophyllum nodosum biostimulants lead to enhanced root development, increased root mass, and a stronger root system. We’ve seen changes in gene expression that affect nutrient uptake and movement within the plant, so plants

grow better and are more productive under limited nutrition. When treated with Acadian’s biostimulants, plants exhibit increased nitrogen absorption, enhancing growth and productivity even with reduced fertilizer application.” - Dr. Holly Little, Director of Research and Development with APH.

through abiotic stress by…

• Reducing plant cell damage

• Enhancing stress tolerance

• Increasing antioxidant production

• Promoting root growth and branching

• Supporting water retention through heat, drought, or salinity

SUPPORTING HEALTHY SOILS

Climate-proofing crops begins with regenerative agriculture and improving soil health. Acadian’s biostimulants support the microbiome, soil structure, and overall contributions to soil organic carbon. Extensive research shows Acadian’s biostimulants support soil health by…

IMPROVING GROWTH AND RESILIENCY

Environmental stress impacts yield 7-10 times more than diseases and pests. As crops confront greater abiotic stresses, the implementation of Ascophyllum nodosum biostimulants in crop management grows.

“With our unique extraction process, we can liberate numerous bioactive compounds such as mannitol, polysaccharides, and betaines. These compounds improve plant tolerance to stressful growing conditions, including, but not limited to, heat stress and drought.” - Dr. Holly Little

• Increasing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) growth

• Strengthening plant-microbe relationships

• Optimizing nutrient availability

• Improving soil aggregation and structure

• Improving CO2 absorption and carbohydrate production

• Increasing nodulation on the roots and root biomass

BOOSTING SUSTAINABILITY AND PRODUCTIVITY

“Adaptability is crucial for farmers facing unpredictable weather patterns. Ascophyllum nodosum biostimulants are a valuable tool to allow growers to maintain consistent yields despite environmental challenges.” - Dr. Holly Little

Start building a climate-smart strategy and enhancing crop performance with Acadian Plant Health.

APH biostimulants work with plants’ internal systems to help maintain productivity and growth

Find out how at www.acadianplanthealth-na.com

Saskatchewan on-farm research expanding

Evaluating trial results from 2023.

BY DONNA FLEURY

On-farm research led by the Saskatchewan Crop Commissions is continuing to gain momentum. In 2023, Sask Wheat, SaskCanola, SaskBarley and the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers (SPG) all offered on-farm research protocols to producers under their respective programs. Farmers who decided to participate can trial new practices and products on their own farms, using their technology and equipment on a commercial field scale.

In 2023, the commissions, with program support from the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF), launched their full-scale on-farm research programs to work with farmers across different crops and different parts of the province. While the programs operate individually, SaskCanola, SaskBarley, Sask Wheat and SPG are working together to generate results that address challenges, including increasing yield, quality and profits for farm businesses.

“One of the foundations of on-farm research is establishing specific trial protocols and treatments that can be replicated and repeated across many locations in the province. The objective of the field-scale trials is to determine if farmers can see agronomic and economic benefits from the protocols,” explains Christiane Catellier, former IHARF research associate. “The protocols, including the experimental design and treatment decisions, are made ahead of time to try to keep the trial execution simple, while also ensuring the validity of the results.”

For the on-farm research trials to be relevant, the protocols are based on good experimental design including replication, randomization and statistical analysis. Using scientifically valid experimental design ensures that the effects observed were a result of the treatment and not due to chance or natural variability. One of the benefits of collective on-farm research is being able to conduct the same trial at lots of different sites so you can get answers more quickly.

“Farmers who participate in the trials are directly supported by a team of collaborators who help onsite at all steps of the trials, from setting up and

ABOVE Wheat samples ready for further testing from on-farm research trials.

implementing the replicated trials during the growing season to scouting, harvesting, data collection and analysis,” says Catellier. “In 2023, IHARF provided direct support to farmers, along with a team of commission staff, farm agronomists and other research supporters. This team approach makes it easier for farmers, protocols can be customized for individual equipment and field site needs where possible and keeps the time commitment manageable during the

Photo courtesy of Sask Wheat.

busy growing season. Farmers also gain a network of other growers and agronomists interested in field-scale research and sharing on-farm results that benefits everyone.”

Participating farmers could work with any of the commissions to choose a protocol they offered, including foliar applied nitrogen (N)-fixing biological products on wheat or canola, or testing seeding rates on red lentils or barley. They will always get first access to the results, including results from their own farm, as well as combined and individual results from other farms. A first look at the results are presented in an early winter meeting and then shared at various commission workshops and meetings to a broader audience. The commissions also published a booklet that included all 2023 trial results and shared it with participants and online.

FOLIAR-APPLIED N-FIXING BIOLOGICAL ON WHEAT OR CANOLA

For 2023, Sask Wheat and SaskCanola had joint protocols to assess the effectiveness of a foliar-applied N-fixing biological on wheat or canola. To simplify the trials and gain more information from replication, one product was selected, Envita, with two trial options. For Option A, farmers could do a simple comparison of Envita applied versus not applied. Option B compared two different applied N rates, a normal rate and a reduced rate of typically 10 per cent, to see if the product would work differently under different N supply rates. Envita was applied either as a tank mix with a herbicide application or in a separate pass. The trial treatments were replicated in each field. For example, for this protocol, Option A was replicated four times for eight passes or strips. Option B was replicated a minimum of four times, requiring at least 12 treatment strips, or more if extra N rates were included.

“The growing conditions in 2023 overall were fairly dry, which could have been a factor,” explains Catellier. “Overall, the combined results showed that yield increased significantly with N supply, but there was no significant yield increase for N-fixing biological treatments compared to untreated. Under these conditions, we weren’t able to measure much of an effect of Envita on wheat or canola.”

TESTING LENTIL SEEDING RATES

SPG’s lentil trials were based on earlier lentil small plot research showing potentially higher yields at higher seeding rates, depending on moisture conditions. A target lentil population of 12 plants/sq ft is generally recommended, but research has shown that populations up to 22 plants/sq ft can provide the highest yield. The 2023 protocol compared three lentil seeding rates, a target of the standard rate of 12 plants/sq ft, a target of 18 plants/ sq foot and a target of 24 plants/sq foot.

Catellier notes that the combined results showed there was a significant decrease in yields at the higher seeding rates, which was not what was expected. However, the results were not consistent, with most sites showing no significant response to seeding rate. Two sites showed a significant positive yield

response and two showed a significant negative yield response. As expected, the visual differences between the treatments showed more even emergence and earlier canopy closure with higher seeding rates. They showed more weed pressure with lower seeding rates. Plants were larger and healthier at lower seeding rates. At higher seeding rates, there was earlier senescence, but it is not clear whether that was related to maturity or disease pressure.

TESTING BARLEY SEEDING RATES

SaskBarley’s barley seeding rate protocol compared three seeding rates of malt barley. The recommended seeding rate for malt barley is 300 seeds/m2, which was compared to a reduced seeding rate of 250 seeds/m2 and a high rate of 350 seeds/m2. Overall, the higher barley seeding rate did not significantly affect plant height, yield, test weight or percent thins in the 2023 trials. However, protein was significantly lower and percent plumps significantly higher in the low seeding rate compared to the standard seeding rate.

While the 2023 trial year was successful overall, there are still some obstacles around data. “One of the challenges that remains is getting the yield data at harvest and we are looking at how to incorporate more digital agronomy data,” says Cattelier. “For the trials, yield was determined for each plot separately by weighing

Be

with a weigh wagon or grain cart with a scale. Additional data may come from yield maps, for example, but ensuring the consistency and quality of the data and confirming calibration methods are still a challenge. The ease of transferring yield data out of onfarm computer programs also remains a challenge. Hopefully with the increasing use of digital agronomy data, it will be easier for both farmers and researchers to get the data consistency and quality they are looking for.”

LOOKING AHEAD TO FUTURE TRIALS

As the trials grow, Catellier expects more farmers will participate. “I’m really pleased with the results of the 2023 program and know that, going forward, the 2024 program will continue with the great collaboration by the commissions and project manager, Kayla Slind, Western Applied Research Corporation (WARC),” says Cattelier.

Each of the commissions’ 2024 on-farm trial programs are underway with various research protocols for the different crops available. The foliar applied N-fixing biological products on wheat or canola is being repeated in 2024, with the option to apply any product participants choose. Depending on the crop selected, various research protocols are being trialed including seeding rate, fertility rates, enhanced efficiency fertilizers, split N application protocols and plant growth regulator protocols.

“Sask Wheat started with four farmers in our inaugural year in 2022 and, in 2024, we have over 20 sites across the province,” says Carmen Prang, agronomy extension specialist with the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission. “The four commissions continue to work closely together, making it easier for farmers to participate in the protocols and crops they are interested in and to share information among the growing network of farmers and agronomists across Saskatchewan.”

In that spirit, Sask Wheat held a large joint field day at Biggar at the end of June 2024, with a great turnout

ABOVE Lentil seeding rate on-farm research trial at seeding.

“Farmers who participate in the trials are directly supported by a team of collaborators who help onsite at all steps of the trials...”

despite unexpected rainfall that kept them out of the fields. Once trials are completed, they plan to host a joint meeting to share the information with the participating farmers and agronomists in January 2025, followed by presentations at other commission winter meetings. “We received great feedback on the 2023 summary report and are already starting to work on the 2024 report that will include all of the results,” says Prang.

Prang notes that they have received great feedback on their Wheat Wise On-Farm Trial program, and participating farmers are seeing great benefits from the opportunity to be part of a larger network and having the resource of the trial information in the program. Along with the field day, Prang and Kaeley Kindrachuk, SaskCanola agronomy extension specialist, visited individual participating farms to learn more about how the trials are going. They investigated challenges participants are facing and suggested improvements going forward. Having the replicated data and the final results at the end of the year helps farmers make better decisions on their farm, providing them with unbiased data and best practices on a commercial farm-scale. Moving forward, there are benefits from having multi-year data to see how the protocols might vary under different weather and environmental conditions. “We look forward to continue to grow the onfarm trials over the next few years, and farmers or agronomists interested in participating can reach out to the individual crop commissions to get involved. Watch for upcoming events and presentations early in 2025 at the various extension events to learn more and consider participating in 2025.”

Photo courtesy of Christiane Catellier.

Meet the next generation of Canadian agri-food leaders

These exceptional students are the winners of the 2024 CABEF Scholarships. We are proud to support each of them with $2,500 for their ag-related post-secondary education. Help us empower more students to pursue diverse careers in agri-food. Strengthen the future of Canadian agriculture and food by investing in the cream of the crop.

Become a Champion of CABEF and directly support a scholarship for a Canadian student.

Emma Pflanz

Vancouver, BC

Brooke-Lynn Finnerty Sturgeon County, AB

Mary Lee McNeil

Alameda, SK

Faryal Yousaf

Brandon, MB

Allison Goodyear

Ottawa, ON

Round Hill, NS

Congratulations to this year’s CABEF scholarship recipients.

Contact CABEF today to learn how you can become a “Champion of CABEF” at info@cabef.org

Emma Bishop

Adapting crop production to changing climate

Agronomy can take advantage of changes.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Numerous research studies have looked at historic climate change over the past 50 to 100 years. These have found increases in growing degree days, corn heat units, the number of frost-free days, as well as the average, maximum and minimum air temperature on the Prairies. Additionally, average annual precipitation and growing season precipitation have increased in Canada, but Western Canada had increases in some regions and decreases in others.

“It has become cliché to say, but the fact is our growing population demands we increase our food production or there will be serious trouble globally in the decades to come,” says Brian Beres, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “To that end, we need to understand what the yield gaps are in our crop production systems to better understand the yield-limiting factors in those cropping systems.”

Beres has looked into how genetics and agronomy could not only compensate for those changes in climate, but also how they could be used to increase yield. He collaborated with the Global Yield Gap Atlas (GYGA) project, which looks at where yield gaps exist, and by how much. It predicts increased food demand by 50 per cent over the next 30 years because of population increase and higher calorie intake largely in developing countries.

To estimate yield gaps, yield potential is evaluated by looking at factors such as genetics, radiation, temperature, carbon dioxide levels, soil type and water availability. The GYGA (www.yieldgap.org) suggests that attaining 70 to 80 per cent of the yield potential is a reasonable target for farmers with access to inputs, markets and extension services. The exploitable yield

gap is the difference between the attainable yield target and average crop yield.

“We estimate that in Western Canada, we are obtaining 60 to 65 per cent of wheat yield potential, so our exploitable yield gap is between 10 and 15 per cent,” says Beres.

ABOVE Brian Beres explains that agronomy can trump changing climate.

That Western Canadian gap compares very favourably to other countries included in the GYGA. The global yield gap for wheat is 52 per cent of its potential, ranging from 34 per cent to 79 per cent across countries. In most regions, non-water related factors such as management are as limiting, if not more, than water supply.

ADAPTING MANAGEMENT

Beres cites two examples of how adapting to changing growing conditions can improve crop production. The first is from his own research on ultra-early seeding of wheat. Traditionally, wheat growers have planted wheat when soil temperatures in the top two inches (5 cm) of soil reach eight to 10 C, or by a specific calendar date like May 9. His research looked at planting wheat into cold soils starting at soil temperature triggers of 0–2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 C. The earliest calendar date triggered at 0 C in his research was February 9, 2022. With a data set of over 50 site-years, Beres has seen the

Photo courtesy of Bruce Barker.

THE LEVEL OF PRECISION YOU’VE COME TO EXPECT FROM US IS NOW AVAILABLE ON YOUR SPRAYER.

Take charge of your spraying accuracy through independent control of rate and pressure with SymphonyNozzle™ and a Gen 3 20|20® monitor. Together they reduce over-application with swath control and level out inconsistent application on turns. Take your sprayer a step further and add ReClaim™, our recirculation system.

WE BELIEVE IN BETTER SPRAYERS WITH BETTER CONTROL.

Over a century of pest surveillance on the Prairies

Continued pest surveillance and monitoring are critical to keeping cropping systems resilient and sustainable over time.

BY DONNA FLEURY

For as long as farmers have been growing crops on the Prairies, managing pests has been a challenge. For over 100 years, pest surveillance activities have been documented on the Canadian Prairies to address the challenges of various insects, weeds and pathogens. Many of the early surveillance and monitoring protocols developed continue to be used today to assess pest populations, track changes and new arrivals, and develop forecasts and management strategies. This long-term continuous surveillance and history of pest populations for crops in Western Canada and the advancements of new tools and resources help farmers be prepared to manage pests in their cropping systems.

INSECTS

“There is a really strong history across all of the disciplines in terms of work done over the past 50 to 100 years,” says Meghan Vankosky, field crop entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon. “Pest monitoring for insects really did originate with grasshoppers in Western Canada, starting in the early 1900s with mail surveys sent out across the Prairies to understand the density, egg-laying activities and damage caused by local grasshopper populations. In the 1920s, the first

transect-based surveillance and monitoring protocols methods were introduced to assess grasshopper abundance. These were among the first and best examples of pest surveys conducted on an annual basis by a small group of very well-trained individuals. We still use this approach today as much as possible to understand pest pressure and provide information for forecasting.”

The first forecasting maps were produced in Saskatchewan in 1931, which were physical hand-colored maps showing the pest pressure for individual municipalities across the Prairies. Over the years, the introduction of technology and mapping tools available for analyzing and visualizing insect monitoring data has evolved. Maps that visualize the distribution and density of important crop pests and other information resources are available online through the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network (PPMN) and have been since 1997.

The PPMN provides growers with insect pest monitoring and risk management information, including weekly in-season updates and maps showing distribution and relative abundance of priority insect pests. The network also uses models to predict when insect pests will be active and to help farmers time their own on-farm scouting during the growing season. For growers and agronomists, developing a strong integrated pest management strategy that includes field pest records and monitoring continues to be valuable

Photo courtesy of Meghan Vankosky, AAFC.

LEFT Meghan Vankosky, AAFC entomologist, with a two-striped grasshopper in the field.

for informed decision-making.

Most insect monitoring and scouting protocols were developed based on available economic thresholds. Using the protocols on the PPMN website can help growers determine if pest abundance is at economic threshold levels and if they should consider chemical control. Just because there are insects visible in a field does not mean the populations have reached the economic threshold requiring control. The PPMN provides information during the growing season to help growers time their monitoring and scouting activities.

“Over the years, there have been shifts in cropping systems. More diversified crop rotations have also resulted in shifts of insect pest populations,” explains Vankosky. “There have also been issues with invasive species throughout history, with a few different species introduced in the last 30 years that have become established pests such as cabbage seedpod weevil and pea leaf weevil. We are also monitoring for swede midge, which is not yet present in Western Canada but is a serious pest in Eastern Canada. We continue to monitor for established invasive species today as it is valuable to know the distribution year to year and what the production risks could be.”

The annual monitoring and other activities, when taken together with historic and current pest monitoring data, will also contribute to expanding and improving pest risk models. Researchers will be able to use different models to assess potential pest populations under different climate and weather scenarios to provide current and future insect pest distribution and forecasts. This will help prepare growers to make informed management decisions and reduce the impacts of insect pests in field crops across the Prairies. Models can be used to anticipate the emergence of insect life stages that are damaging to field crops and predict changes in insect populations and distribution related to climate change. The data collected by insect surveyors is priceless.

Continued annual monitoring programs and scouting activities will facilitate early detection of insecticide resistance or the breakdown of host plant resistance. Vankosky adds that although insecticide resistance is not considered a problem for most insect pests on the Prairies, it’s important to be proactive in assessing whether there are populations of these insect pests that are becoming resistant to pesticides typically used to manage them.

Cleanfarms 2024 Unwanted Pesticides & Old Livestock/Equine Medications Collection

Southern Alberta

BARNWELL

Tuesday, Oct. 22

V2K

QUESNEL Thursday, Oct. 24 Four Rivers Co-operative 1280 Quesnel Hixon Rd., V2J 5Z3

VANDERHOOF Monday, Oct. 21 Four Rivers Co-op 1055 Hwy. 16 W., V0J 3A0

VERNON Tuesday, Oct. 22

Growers Supply Co. 1200 Waddington Dr., V1T 8T3

WILLIAMS LAKE Friday, Oct. 25

153 Mile Fertilizer

#80-5101 Frizzi Rd., V2G 5E4

Independent Crop Inputs Inc. N.W. of 27-9-17 West of Hwy. 4, 94035 Range Rd. 17-3, T0K 0B0

BARONS

Thursday, Oct. 24

South Country Co-op Ltd. 123014 Range Rd. 234, T0L 0G0

BENALTO Friday, Oct. 25

Benalto Agri Services Ltd. 38531 Range Rd. 2-4, T0M 0H0

BROOKS Friday, Oct. 25

South Country Co-op Ltd. 7th St. and Industrial Rd., T1R 1B9

CARSELAND Monday, Oct. 21

Cargill 263026 Township Rd. 221, Corner Hwy. 24 & Agrium Rd., T0J 0M0

DRUMHELLER Monday, Oct. 21

Kneehill Soil Services Ltd.

700 South Railway Ave. W., T0J 0Y0

DUNMORE

Thursday, Oct. 24

AgroPlus Inc. 2269 - 2nd Ave., #22, T1B 0K3

FOREMOST

Wednesday, Oct. 23

AgroPlus Inc.

199 1st Ave. W., T0K 0X0

FORT MACLEOD

Wednesday, Oct. 23

Nutrien Ag Solutions

250 Boyle Ave., T0L 0Z0

HANNA

Wednesday, Oct. 23

Hanna UFA Farm & Ranch

Supply Store

601 1st Ave. W., T0J 1P0 HIGH RIVER

Friday, Oct. 25

Nutrien Ag Solutions 498012 – 122 St. E., T1V 1M3

HUSSAR

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Richardson Pioneer 151 Railway Ave., T0J 1S0

INNISFAIL

Thursday, Oct. 24

Central Alberta Co-op 35435 Range Rd. 282, T4G 1B6

LETHBRIDGE COUNTY

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Parrish & Heimbecker Wilson Siding 75006 Hwy. 845, T1K 8G9

LOMOND

Monday, Oct. 21

South Country Co-op Ltd. 115 Railway Ave., T0L 1G0 OLDS

Wednesday, Oct. 23

Olds UFA Farm & Ranch

Supply Store 4334 46th Ave., T4H 1A2

OYEN

Thursday, Oct. 24

Richardson Pioneer 1 mile East on Hwy. 41, T0J 2J0

THREE HILLS

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Richardson Pioneer 503 - 3rd St. S.W., T0M 2A0

VETERAN Friday, Oct. 25

Richardson Pioneer 400 Waterloo St., T0C 2S0

WARNER

Monday, Oct. 21

Nutrien Ag Solutions

Junction Hwy. 4 & Hwy. 36, ½ mile N. on the Access Rd., T0K 2L0

Northern Saskatchewan

BIGGAR

Tuesday, Oct. 8

Parrish & Heimbecker 12 km West of Biggar on Hwy. 14, S0K 0M0

BRODERICK

Friday, Oct. 11 Rack Petroleum Ltd. Broderick Access and Hwy. 15, S0H 0L0

CARROT RIVER Tuesday, Oct. 8 Richardson Pioneer 265 2nd St., S0E 0L0 HAFFORD Wednesday, Oct. 9

AgriTeam Services Inc. 11 km West of Hafford on Hwy. 340, Turn North on Jackson Rd., S0J 1A0

HUMBOLDT Thursday, Oct. 10

Humboldt Co-op 10564 Crawley Rd., S0K 2A0

IMPERIAL

Friday, Oct. 11

Richardson Pioneer 1 mile North on Hwy. 2, S0G 2J0

KINDERSLEY Wednesday, Oct. 9

Simplot Grower Solutions 907 11th Ave. E., S0L 1S0

MEADOW LAKE Monday, Oct. 7

Meadow Lake Co-op 513 9th St. W., S9X 1Y5

MELFORT

Wednesday, Oct. 9

Nutrien Ag Solutions 810 Saskatchewan Dr. W., S0E 1A0

NEILBURG Friday, Oct. 11

Nutrien Ag Solutions 300 Railway Ave. E., S0M 2C0

NORQUAY

Tuesday,

PESTS AND DISEASES

WEEDS

Weed surveys were recorded on the Prairies as early as the late 1800s, with the first organized Prairie survey from 1930 to 1931. The seven most problematic weeds were perennial sow thistle, Canada thistle, wild oat, stinkweed, couch grass, and poverty weed. Annual weed surveys continue today, building on earlier methodologies.

“For many decades after the widespread adoption of herbicides, weeds were effectively managed in crops,” says Charles Geddes, research scientist specializing in weed ecology and cropping systems with AAFC in Lethbridge. “However, in recent decades we are seeing some of those chemical options unfortunately failing and having to turn to alternative weed management. AAFC researchers have been monitoring weeds for a long time, with the focus on weeds that occur in crops, although we know weeds can also be issues in other adjacent areas such as naturalized areas, pasture lands, roadside ditches, railways and industrial lands. The current methodology for annual Prairie Weed Surveys or weed abundance surveys was launched in the 1970s and continues today.”

Currently led by Julia Leeson, weed monitoring biologist from AAFC Saskatoon, the surveys cover about 4,000 fields across the Prairies over a four-year timeframe to evaluate weed density by species in late July or early August after in-crop management is completed. This consistent standard methodology provides a very good picture of which weeds are increasing or decreasing in abundance or populations that remain unchanged.

“This allows us to compare how weed abundance is shifting over the decades, with the latest Prairie Survey completed in 2023, or round six since the 1970s,” explains Geddes. “The top three most abundant mid-season weed species over the five decades generally include green foxtail, wild oat and wild buckwheat, although there are some shifts depending on the location. The top five weeds that have increased in abundance to the greatest degree since the 1970s/1980s were foxtail barley, annual bluegrass, false cleavers, low cudweed and spiny sowthistle in Alberta; black medick, low cudweed, spiny sowthistle, volunteer lentil and false cleavers in Saskatchewan; and foxtail barley, golden dock, spiny sowthistle, yellow foxtail and green pigweed in Manitoba. Some of these weed shifts may be from changing cropping systems and diversified crop rotations, while herbicide resistance may be the reason weeds such as yellow foxtail are increasing.”

Due to the increase in herbicide resistance issues

ABOVE Wild oat has historically been one of the most problematic weeds on the Prairies and continues to be a problem in many crops including flax.

since the 1980s on the Prairies, surveys for herbicide resistance were started by research scientist Hugh Beckie in the early 2000s. The fourth round of those surveys was completed in 2023, with a subset of about 800 fields surveyed across the Prairies over four years. The field area occupied by herbicide-resistant weeds across the Prairies was 10.8 million acres in the 2001 to 2003 survey, increasing to 24.5 million acres by the 2007 to 2009 round and to 40 million acres in 2014 to 2017. The issue continues to grow at a steady pace, and once the information from this last round of surveys is compiled, a continued increase in this fourth round is expected.

“A recent project funded by RDAR is the development of genetic tests for herbicide resistance,” says Geddes. “Instead of having to collect seeds and do the time-consuming greenhouse testing using whole-plant biomass, we will be able to use a leaf sample, extract the DNA and look for the mechanisms that confer resistance. This will provide a much quicker result than the traditional method. So far, we have developed 14 different tests based on weed biotypes on the Prairies, with each test unique to the species and mode of action. Once we have expanded the number of tests, we plan to license the methodology and tests to diagnostic labs to offer to farmers.”

Similar to the PPMN, the Prairie Weed Monitoring Network is also under development. “The weed abundance data collected from thousands of fields across the Prairies over the years can be combined with different datasets to add value for farmers, such as helping to develop risk models for where certain types of herbicide resistance, for example, may be more likely to develop,” says Geddes. “As weed communities shift due to management or climate, we can harness the data collected in the past and look forward to seeing how things might be changing moving forward.”

DISEASES

Wheat production on the Prairies has a long history from at least the 1880s and continues to be the predominant crop in Western Canada. Cereal diseases such as stem and leaf rust were some of the earliest serious diseases and, by 1920, the first systematic plant disease annual surveillance efforts were initiated. The Canadian Plant Disease Survey (CPDS) today contains surveillance data from 1920 on plant diseases from the AAFC laboratories, provincial organizations, private companies and university researchers. The data is available on the Canadian Phytopathology Society (CPS) website at phytopath.ca/publication/cpds.

“To combat the problems of rust diseases in cereals, the Dominion Rust Research Laboratory was established in 1925 in Winnipeg, bringing

Photo courtesy of Charles Geddes, AAFC.

together wheat breeders, pathologists and quality experts,” says Brent McCallum, plant pathologist with AAFC in Morden, Man. “Stem rust on wheat was devastating crops, with 1927 recorded as one of the worst in history. Genetic resistance was a good tool, but researchers had to understand the pathogen population and what resources to use for developing resistant varieties. This formed the basis of our annual disease surveys that continue today for a range of cereal and other crop diseases, and for genetic resistance advancements. These efforts mean growers have varieties with good resistance for stem rust, leaf rust and, more recently, stripe rust in wheat and barley, as well as crown rust of oat.”

“Continuing our annual disease pest surveillance remains critical today to know what diseases we have in Canada and understand the virulence and population of pathogens coming in, how they evolve and other new introductions,” emphasizes McCallum. “A recent example is a leaf rust race in Mexico that affects durum wheat that we have started monitoring. Although durum crops currently in Canada and U.S. are resistant to the current rust population of leaf rust on durum wheat, we want to monitor to ensure that this race of the pathogen doesn’t move into Canada, and to start breeding for resistance to be prepared in case it does.”

Advancing genetic resistance for Fusarium head blight (FHB) is one of

the priorities for monitoring pathogen evolution, identifying effective resistance and stacking resistance genes together to make a better package. McCallum notes that although introducing new genes for FHB resistance is a priority, breeders still want to keep the resistance developed for other diseases like stem, leaf and stripe rust to ensure one disease isn’t traded off for another in varieties. Growers can use annual provincial seed guides to review disease ratings for various diseases to help select cultivars suited for their area.

Reem Aboukhaddour, cereal pathologist with AAFC in Lethbridge, works largely on stripe rust and leaf spot diseases in cereals, as well as managing the common bunt plant nursery. She took on the challenge of reviewing the annual plant disease surveys through history, trying to standardize descriptions and severity scales to support continuing surveillance efforts. “There has been a lot of work over the years to screen different pathogenic races and genetic resistance, which is critical for breeders for developing disease resistance in varieties. There is a lot of variation in pathogens and the more races there are, the more complex developing genetic resistant varieties can be. Over the years, fungicides have become more available to help control fungal diseases, and growers must continue to combine the use of the various tools including fungicides, genetic resistance, rotations and other best practices to manage diseases in crops.”

“One of my priorities is to understand the diseases and its pathogens, working with isolates obtained from the fields and molecular tools to monitor any changes and evolution in races and new introductions,” says Aboukhaddour. Lethbridge has stripe rust isolate samples from 1982, and more have been added since she started in 2016.

A full screening in the greenhouse and fingerprinting of the isolate collection provides comprehensive information about the change in the stripe rust pathogen over the past 35 years. “We can use this collection further to define markers and monitor for race inclusion in resistance breeding efforts,” says Aboukhaddour. “We can also trace movements of pathogens, such as rust that can move long distances in the atmosphere. Leaf spot diseases in wheat and barley are another priority and may be causing more yield loss than expected. We are trying to optimize easier and faster ways to differentiate the different leaf spot disease

TOP TO BOTTOM West side of Rust Laboratory showing Winnipeg Electric street car terminal, 1926; This picture, taken in February 1953, was evidently related to the production of Selkirk wheat, (left to right) A.B. Campbell, T. Johnson, R.F. Peterson, A.B. Masson.

Photos

pathogens such as septoria, tan or septoria blotch, that all have similar symptoms in the field. We are optimizing molecular tools in the lab to tell them apart in the field and help determine which one may predominate in certain locations and which one is causing the most damage in certain environments.” Combining annual field surveillance with these efforts provides the foundation for plant breeders and genetic resistance.”

With changing cropping systems, more diversified crops, and the transition from conventional to conservation tillage through the 70s, 80s and 90s, other problem crop diseases increased. “As a graduate student, I worked on Sclerotinia and blackleg of canola and, depending on the disease, these were primarily managed by crop rotations, fungicide application and/or avoiding blackleg-infected seed,” says Kelly Turkington, plant pathologist with AAFC in Lacombe, Alta. “Most canola varieties in the 80s were susceptible to blackleg, but by the early 90s, the first genetic resistance was available. Other canola diseases such as clubroot [started] showing up in 2003 and, with pathology and breeding efforts of both public and private researchers, the first varieties with resistance were introduced in 2009 and 2010.” Blackleg and clubroot continue to be primarily managed with host resistance. Fungicides are also an important management tool to mitigate risk, but growers need to manage carefully to reduce potential resistance.

One of Turkington’s biggest worries is the tighter cropping rotations today that don’t allow sufficient time for the decomposition of crop residue and disappearance of a source of inoculum. Although many factors influence what producers grow – such as commodity price, established markets and others – for some crops, a minimum of two or three years in rotation is critical to minimize disease risks. “For diseases largely managed by genetic resistance such as blackleg and clubroot, having enough resistance genes in reserve to stay ahead of these diseases is a concern,” says Turkington. “In field peas, the catastrophic development of Aphanomyces root rot in peas requires a six-year rotation in those affected areas to manage the disease. Researchers are working on other tools, but it is a challenging pathogen to manage.”

Pathologists and breeders continue to focus on advancing genetic resistance packages for crops, but staying ahead of pathogen development requires continued surveillance combined with molecular pathotyping and other tools. Turkington highlights some of the broad trends in diseases, such as the increasing prevalence of spot blotch. Once more of a central Saskatchewan to Manitoba concern, it’s now becoming more widespread in the Prairies. Mycoplasma and viral issues may become more of a concern with milder winters, given there may be better overwintering potential for causal agents and their insect vectors. Cereal rusts typically blow in from source areas in the U.S., but milder winters may allow stripe rust to survive on winter wheat resulting in earlier and potentially more damaging epidemics.Growers can watch for regular cereal rust updates on the Prairie Crop Disease Monitoring Netwrok (PCDMN) from mid-

May to early June.

“We launched the PCDMN in 2018, and similar to the PPMN for insects, the network will help farmers, agronomists and researchers stay on top of the disease issues they have or may encounter. This is via forecasting potential plant disease issues, improving awareness of where and when crops may be affected, and improving identification and promotion of key management strategies.”

“Within AAFC, we have started the Prairie Biovigilance Network to bring together various researchers and experts working on diseases, insects and weeds to lead the high level of surveillance and really understand what we are up against,” adds McCallum. “This network of people collaborating on this initiative including farmers who contribute to funding through their grower organizations, grant land access for surveying, and who often identify issues early on are valuable. AAFC has been helping farmers and industry for more than 100 years and the early tools developed are still valid today. There is no substitute for getting out in the field to see what is going on firsthand and sampling pest populations. Continuing the annual surveillance efforts is the only way we can monitor pests, see how they are changing over time, and develop strategies and resources to keep one step ahead of pests in crops.”

THE EARLY BIRD USES

Apply this fall to support a strong start to next season. Don’t wait on your kochia management stategy.

Contact your local Gowan Representative to learn more.

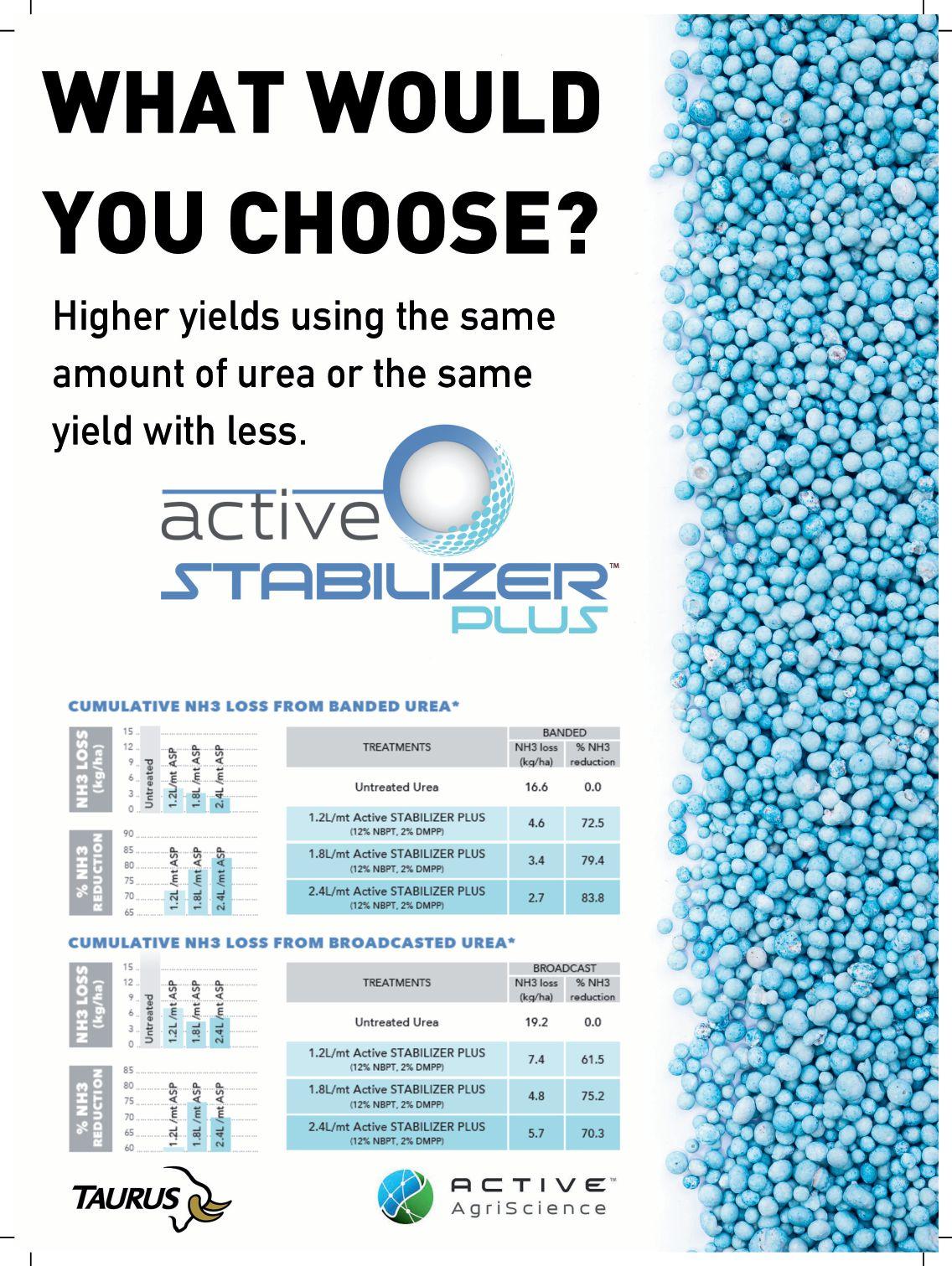

Investigating safer seedplaced phosphorus products

Struvite is safer but with lower canola yield.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Seed-placed phosphorus (P) is a conundrum that many canola growers must address. Canola is a large user of P, but relatively little can be safely placed in the seedrow. Side-banding is an option, but 2021 market research by Stratus Ag Research found that 44 per cent of canola acres have P applied in the seedrow, compared to 31 per cent for side-banding and 13 per cent for mid-row banding.

“It is well documented that high rates of seed-placed P fertilizer can reduce seedling survival and establishment in sensitive crops such as canola,” says Chris Holzapfel, research manager at the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation. “However, many farmers prefer to place at least a portion of their P in the seedrow to ensure it is not limiting early in the season.”

Holzapfel led a Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture ADOPT (Agricultural Demonstration of Practices and Technologies) research project over three years from 2020 through 2022 to look at novel sources of P and how they impact stand establishment and yield. Field trials were conducted at AgriARM sites at Indian Head, Melfort, Outlook, Redvers, Scott, Swift Current and Yorkton, Sask. with project locations varying from year to year resulting in a total of 14 site-years.

The forms included monoammonium phosphate (MAP;11-52-0), MicroEssentials S15 (13-33-0-15), CrystalGreen (struvite; 5-28-0 + 10 per cent Mg), and a 50:50 blend by mass of product of MAP and CrystalGreen, resulting in an analysis of 8-40-0 + 5 per cent Mg. While not always the case, struvite can be precipitated from urban wastewater, potentially allowing for what would otherwise be both a finite resource and an environmental contaminant to be recycled back onto the land. The salt index values are 27 for MAP, 21 for MES15 and 8 for struvite, with increasing seedling safety with lower salt index values.

Three side-banded rates of 22.25, 40 and 59 lbs. P2O5/ac (25, 45 and 65 kg P2O5/ha) were compared to a control, where no P was applied. The low seedrow rate would be considered safe under most conditions,

while the middle rate would start to push safety, and the high rate would be considered risky. For example, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture guidelines for canola indicate that the maximum safe rates of seedrow P is 25 lbs. P2O5/ac based on knife openers with a oneinch spread on nine-inch row spacing and good to excellent soil moisture.

ABOVE Struvite was safer than other forms of P when placed in the seedrow.

Nitrogen (N) was adjusted to a consistent rate across treatments at each location, and ammonium sulfate was applied to ensure sulphur (S) was not a limiting factor. Nitrogen and S fertilizers were always side-banded. Drills with narrow hoe openers and row spacing ranging from 8.25 to 11.8 inches (21 to 30 cm) were used to seed the plots. Target seeding depth was 0.8 to one inch (two to 2.5 cm).

Spring plant and post-harvest plant densities were measured, and grain yield was calculated and adjusted for dockage and to 10 per cent seed moisture content. Maturity data was collected but treatment effects were variable, small and inconsistent.

Photo courtesy of Chris Holzapfel.

Register for the 5th annual Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture Summit

Join us online, from anywhere, to hear from today’s most influential female leaders in Canadian agriculture.

This year, the seven IWCA honourees of 2024 will come together with other prominent trailblazers to share their experiences, lessons learned, advice and more during the virtual IWCA Summit.

Join us for an afternoon of interactive conversation as they share their knowledge, offer guidance and discuss their journeys in agriculture.

OCTOBER 22, 2024 VIRTUAL EVENT I 12:00PM ET

ENHANCED EFFICIENCY

Crystal Green Synchro 50 MAX Ostara magnesium ammonium phosphate hexa-hydrate and monoammonium phosphate.

Duo Maxx Timac Agro 15% nitrogen, 0.2% soluble potash, 0.8% NBPT, 0.2% DCD, 0.1% Tryptophane, Rhizovit Complex 15% nitrogen, 0.2% soluble potash, 0.8% NBPT, 0.2% DCD, 0.1% Tryptophane, Rhizovit Complex

5% slowly available total nitrogen (N), 28% slowly available phosphate (P2O5), and 10% slowly available magnesium (Mg) from magnesium ammonium phosphate hexahydrate.

9% slowly available nitrogen, 42% slowly available phosphorus, and 7% slowly available magnesium from magnesium ammonium phosphate hexa-hydrate (struvite)

coated urea granule releases N by diffusion through coating when in contact with water. Release rate controlled by coating thickness, type and soil temperature.

Granular

Brought to you by:

Information compiled from fertilizer manufacturers. Follow the information on product labels and consult an expert if there are any discrepancies with the information in this table.

FERTILIZER PRODUCTS

RECOMMENDED USES

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN.

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN.

Liquid treatment to coat urea or additive to UAN.

May be used with anhydrous ammonia, aqua ammonia, urea ammonium nitrate, and other liquid ammoniacal or urea nitrogen fertilizers and liquid manure. CENTURO can be used for any crop that requires nitrogen fertilization, including row and specialty crops where a nitrification inhibitor is needed.

Use in place of traditional phosphorus sources. Seed-safe and root-activated, allowing product to be placed directly in row with the seed.

Use in place of traditional phosphorus sources. Seed-safe and root-activated, allowing product to be placed directly in row with the seed.

Treatment of dry granular or liquid fertilizers containing phosphate.

eNtrench NXTGEN is designed for use with UAN, liquid manure and dry urea.

Any nitrogen fertilizer application.

Treatment of dry granular urea of liquid UAN.

Any nitrogen, phosphorous, sulfur, and/or zinc application.

Any nitrogen, phosphorus and/or sulfur application.

Any nitrogen, phosphorus and/or sulfur application.

Designed for use with anhydrous ammonia, N-Serve must be injected or incorporated in a zone or band in the soil with the fertilizer at a minimum depth of 5 to 10 cm.

Use in place of traditional potassium, sulfur, or calcium/gypsum sources. Low salt index allows to be placed directly in row with the seed.

Use in place of traditional potassium, sulfur, or calcium/gypsum sources. Low salt index allows to be placed directly in row with the seed.

Any nitrogen fertilizer application.

PRODUCT BENEFIT

ARM U ADVANCED is a two-part nitrogen saving technology that inhibits both ammonia volatilization, nitrification and denitrification. ARM U ADVANCED inhibits ammonia volatilization, nitrification and denitrification by inhibiting the activity of urease enzymes as well as nitrosomonas and nitrobacter bacteria in the soil. The formula contains polymers (spreader molecules) that increase the activity of NBPT and DMPP. This increased activity enables a lower percentage of active ingredient and a lower use rate while maintaining efficacy. ARM U ADVANCED also has a high buffering capacity to keep the solution pH below 7, and to protect and fully utilize the nitrogen present in the NBPT molecule. The liquid formulation is easy to use, has a minimal odour, and also acts as a dust control agent.

Active BANDIT utilizes advanced DMPP technology to combat nitrogen loss by inhibiting both nitrification and denitrification processes. By minimizing nitrogen loss, Active BANDIT maximizes nutrient availability within the root zone, promoting healthier plant growth and optimal yield outcomes.

A liquid fertilizer additive that controls ammonia volatilization and loss of nitrogen through nitrification from urea and UAN fertilizers.

CENTURO is used to delay nitrification of ammoniacal and urea nitrogen fertilizer by inhibiting the oxidation of ammoniacal nitrogen to nitrate nitrogen. CENTURO is noncorrosive to the metals used in anhydrous ammonia and UAN equipment, making it easy to handle and gentle on equipment.

Unlike conventional phosphate fertilizers, which release nutrients upon watering or irrigation, Crystal Green releases nutrients in direct response to root demand – when the plant releases organic acids, Crystal Green releases nutrients. This results in a steady source of phosphorus (along with nitrogen and magnesium) throughout the growing season.

Crystal Green Synchro is the first and only phosphate fertilizer to combine the availability of MAP with controlled release utilizing the root-activated technology of Crystal Green.

Crystal Green Synchro 50 is a fully homogeneous sustainable struvite-based granular fertilizer. There’s no need to blend Crystal Green and MAP. Crystal Green Synchro 50 is like blending a 50:50 ratio of Crystal Green and MAP, but instead of a blended fertilizer, it’s a fully homogenous granular fertilizer.

Duo Maxx is designed to stabilize primary and secondary nutrients by binding and protecting them from loss and (or) retrograde tie-up. Duo Maxx contains a combination of NBPT and DCD designed to slow nitrogen transformation. Includes patented Duo Complex.

eNtrench NXTGEN protects nitrogen by keeping it in a positive ammonium form, in the root zone, longer so it is available for plant use and less likely to be lost to leaching or denitrification. eNtrench NXTGEN inhibits the nitrifying bacteria allowing the nitrogen to be stored at the root zone for optimal plant use.

The unique polymer coating protects and releases nitrogen at a rate controlled by soil temperature. ESN thereby supplies N to the crop at a controlled rate to reduce N loss, increase N-use efficiency, and improve grower profit.

Excelis Maxx contains urease inhibitor (NBPT) to protect nitrogen from volatilization, nitrification inhibitor (DCD) to protect against denitrification and leaching and an LCN Complex. Excelis Maxx is formulated with our Rhizovit Complex, which provides the added benefit of a root stimulating effect.

The uniform nutrient distribution provided by MicroEssentials ensures product is delivered evenly across the field, providing crops an adequate chance of taking in key nutrients for season-long nutrition. By reducing the pH around the granule, the unique chemistry of MicroEssentials promotes interactions that improve nutrient uptake of P and S. In addition, MicroEssentials combines two forms of S, sulfate and elemental sulfur, in every granule to ensure S availability throughout the growing season. Sulfate sulfur satisfies seedlings’ needs for early-season growth, while elemental sulfur is available later in the growing season.

N-Serve nitrogen stabilizer slows the conversion of ammonium nitrogen (NH4+) to nitrate nitrogen (NO3-). Both forms are plant available, however, nitrate nitrogen is much more prone to loss from denitrification and leaching. N-Serve ensures that the nitrogen that you apply is available when the crop needs it, helping to maximize yield.

Polysulphate Premium acts as a comprehensive four-in-one prill fertility supply, providing essential nutrients while improving soil health and enhancing the efficiency of water and nutrient use by plants.

Sul4R-Plus acts as both a nutrient source and a soil conditioner, promoting healthier plant growth and improving soil health.

SUPERU is a premium fertilizer featuring urease and nitrification inhibitors to guard against all three forms of nitrogen loss — volatilization, leaching and denitrification.

Seed-safe starter blend fertility option for in the seed row. Just add nitrogen. Five nutrients in one prill offering seed-safe, immediately plant available nutrition that feeds the plant all season.

Highly available orthophosphate in all pH and temperatures.

TRIBUNE is designed to protect liquid urea-based fertilizers from ammonia volatilization, leaching and denitrification. TRIBUNE can be used for any crop that requires nitrogen fertilization, including row and specialty crops where a nitrification inhibitor is needed.

Top-Phos is an orthophosphate which makes it more available in low temperatures. It contains a complexing agent to protect phosphate against tie-up in all pH. Top-Phos has a low salt index (9), and is seedrow safe with an added root stimulating benefit.

Dual active ingredients NBPT, the most research-proven urease-inhibitor technology, and the patented active ingredient Pronitridine, safeguard nutrients from volatilization, leaching and denitrification.

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

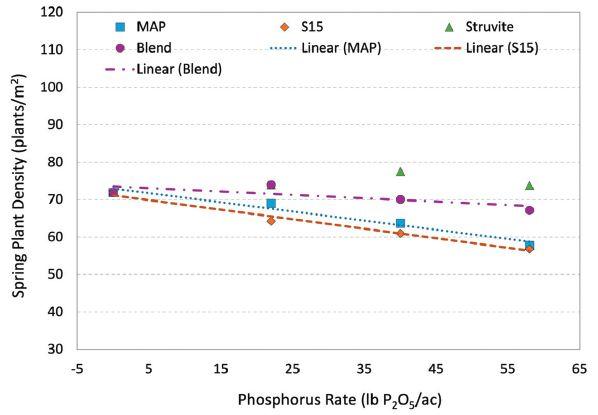

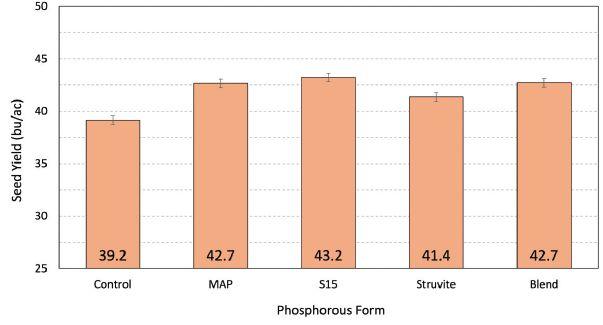

Investigating safer seed-placed phosphorus products | CONTINUED FROM PAGE 18

RESPONSE DIFFERED BY ENVIRONMENT

Indian Head and Melfort, both in the Black soil zone, had few significant differences between form and rate. “At those sites, we got away with some very risky practices, just with the finer textured soils and higher organic matter. We really didn’t have any impact of P form or rate on canola establishment in those environments.”

Seven of the 14 site-years showed a response to form, rate or their interaction. Looking at form, Holzapfel says that struvite always stood out as having the highest spring plant densities (7.5 plants/ft2), most often significantly higher than MAP (6.4 plants/ft2) or S15 (5.9 – 6.1 plants/ft2), and often higher than the blend (7.0 plants/ft2). The blend also most often had significantly higher densities than MAP or S15. MAP and S15 were often similar for plant densities.

“Notably, none of these averaged populations were low enough to be expected to limit canola yields or result in agronomic issues. However, the relative rankings of plant populations with each formulation were as expected and all differences between forms were statistically significant,” says Holzapfel.

The interaction of P form by rate followed similar trends for spring densities. As rates increased, MAP and S15 had declining stand establishment, while the blend had a slight decrease in densities, and struvite was unaffected by rate.

YIELD RESPONSE TO P

In terms of yield, results did vary by site and, in most cases, all forms yielded fairly well at responsive sites. However, averaged over all 14 sites, the pure struvite yielded significantly lower than the other forms. “That is likely because that form isn’t very soluble and maybe not quite as available early in the season, which is why I think the blend makes more sense,” says Holzapfel.

Averaged across the 14 site-years, canola fertilized with P yielded 15 per cent higher averaging 42.5 bu/ac (2,387 kg/ha) compared to the untreated control at 39 bu/ac (2,200 kg/ha). Yields were statistically similar with MAP, S15 and the MAP:struvite blend ranging from 42.6 bu/ac to 43.2 bu/ac (2,397-2,429 kg/ha), but pure struvite yielded slightly yet significantly lower at 41.2 bu/ac (2,324 kg/ha). Notably, the lower yields with pure struvite did not occur at all responsive sites but did show up in isolated cases and on average.

An economic analysis was conducted based on February 3, 2022 fertilizer prices, taking into account the value of N and S in the products. The cost of 1 lbs. of P 2 O 5 was $1 ($2.13) for MAP, $1.39 ($3.06) for S15, $2.38 ($5.23) for struvite and $1.47 ($3.24) for the blend. Gross revenue was calculated using a canola

ABOVE Seed-placed P form x rate effects on canola emergence (14 site average)

price of $20.45/bu ($900/Mt).

Marginal profits were similar for MAP, S15 and the blend, but were lower for struvite because of its higher cost and slightly lower yield. Across formulations, marginal profits were similar for rates of 22.25 and 40 lbs. P 2 O5, but slightly lower for the highest rate due to diminishing yield gains and higher P cost.

Combining form plus rate, the most profitable rate was 40 lbs. P2O5/ac for MAP and S15, 22.5 lbs. for 100% struvite and 59 lbs. P2O5/ac for the MAP:CG blend.

Overall, Holzapfel says the research found that the observed stand reductions were relatively minor but frequent and unpredictable enough to justify caution when seed-placing higher than recommended rates of P fertilizer. This is especially the case if seed-placing other fertilizer products such as ammonium sulfate or potash, which can also contribute to fertilizer burn. It is important to acknowledge that side-banding is also a safe and effective placement option for P fertilizer. For growers who insist on seed-placing high rates of P, the blend of struvite will reduce the risks of it; however, recommending pure struvite is difficult primarily due to the high cost.

BELOW Seed-placed phosphorus form effects on canola seed yield (14 site averages)

A new approach to countering blackleg resistance

Improving canola varieties by removing genes susceptible to blackleg.

BY LEEANN MINOGUE

Blackleg, caused by the fungus Leptosphaeria maculans, is nothing new to Western Canadian canola growers, and blackleg-resistant canola varieties have become a key part of integrated disease management plans. Single-gene resistance can break down over time though. New research suggests looking at the problem from a different perspective – the susceptible genes.

“Fifteen years ago, we were in a bit of a panic, with the thought that the disease would affect us badly, because most of our varieties lacked effective resistance genes,” says Gary Peng, a research scientist at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Saskatoon Research and Development Centre. The last decade and a half changed that, bringing impressive advances in blackleg-resistant varieties that farmers have been quick to adopt for general use.

Researchers have developed these resistant varieties in two ways, including the quantitative multiple-genic approach, which results in plants with general blackleg resistance. The second method is the qualitative single-gene approach, where a single gene that is resistant (R) to the blackleg pathogen can be added to the general resistance genetic background to develop a new variety.

The single-gene approach can be highly effective if it matches an

avirulence gene already prevalent in the pathogen population in a field. However, for every R gene we know, there is at least one virulent pathogen race in Western Canada. This can cause single-gene resistance to break down over time as the in-field blackleg population shifts. That’s why staying ahead in the resistance race requires farmers to switch to varieties with different R genes. The challenge is that most of the R genes researchers have identified to date have already been overcome by a pathogen population somewhere in the world.

A three-year study, funded by the Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF), Alberta Canola, Manitoba Canola Growers and SaskCanola, seeks a workaround for this problem. Peng is leading the project; some of his colleagues include Dr. Dilantha Fernando, professor of plant pathology at the University of Manitoba, Dr. Shuanglong Huang, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Manitoba and Dr. Raju Datla at the Global Institute for Food Security in Saskatoon.

The research project is taking a completely different approach to developing resistance. Instead of adding blackleg-resistant genes to canola plants, Peng and his team are looking for genes that make canola

ABOVE Gary Peng (centre right) is leading a research project that seeks to counter blackleg resistance.

Photo courtesy of Gary Peng.

susceptible (S) to blackleg with hopes of removing S genes from a new variety, a task that’s significantly more complicated. “It’s like finding a needle in a haystack,” says Peng.

IN SEARCH OF SUSCEPTIBLE GENES

What helped Peng face the seemingly insurmountable task of looking through the “haystack” was another group of researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC), led by Dr. George Haughn. They used the chemical EMS to mutate the DNA of the canola line DH12075 (known as chemical mutagenesis) and developed more than 3,000 lines of mutated canola.

With a process called TILLING (Targeting Induced Local Lesions in Genomes), they were able to identity 432 unique mutations of 26 different genes within these 3,000 lines, places where “point mutations” had occurred, altering one base pair of the plant’s DNA.

These mutant lines were sent to Dr. Datla’s GIFS lab in Saskatoon, where staff grew them out for further research before being transferred to Peng and his team. Now they are growing out 10 to 20 plants from each of the 400 or so mutated lines, using greenhouses at AAFC Saskatoon and at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

Peng’s team is inoculating each growing plant with a highly virulent isolate of the blackleg pathogen at four different sites on two cotyledons per plant. Then they compare these infected plants with a susceptible canola line (DH12075), looking for mutated plants that are substantially less susceptible to blackleg.

Peng hopes studying these less susceptible plants will allow researchers to identify susceptibility-related (S) genes and remove S genes from canola plants to develop a new resistant variety.

PROGRESS TO DATE

As of the end of June, Peng and his team had tested 200 lines and identified two lines with strong resistance to blackleg. Two of 200 might sound like poor odds, but Peng is very pleased with the results.

The research team is growing these two lines out for further research. They hope to find that the plants’ S genes are homozygous, genes resulting when a plant inherits identical versions of a gene from both its female and male parents, because it will be simpler to isolate the S gene.

With more lines to assess, Peng hopes to find more resistant mutants. “If we have three or four stable mutants to study, that would be remarkable,” he says. They’re also screening these mutants for clubroot resistance. “A couple of lines have shown promise,” Peng says. The mutants resistant to blackleg and clubroot are different plants, implying that different S genes are involved with blackleg and clubroot.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT

Even with promising leads, a new commercial variety is far in the future. The team needs to do more work to understand the

molecular and biochemical function of the mutation. If S genes can be identified, gene editing is the next step. “Once we identify where the mutations are, genome editing may be used to knock out certain genes from our current variety and make them less susceptible to diseases.”

Knocking out genes related to pathogenicity could result in varieties with general blackleg resistance. Theoretically, this should result in resistance that is not eroded quickly by changes in the in-field pathogen population. But Peng cautions, “We’re still in the early stages.”

THE FUTURE IS HERE

This project is possible due to gene editing tools like CRISPR/ Cas9. “We can be more efficient in many ways by using the molecular tools more effectively,” Peng says. For example, UBC researchers quickly determined which of their 3,000 mutagenic lines carry true genetic mutations, narrowing the population required for Peng’s study.

No matter how efficiently researchers can work in labs and greenhouses, the final step will always be outside in a field. “There will always be some growing process involved,” Peng says. “When we’re working with agriculture, we can’t isolate ourselves from real growing conditions. That’s the ultimate test of whatever product you have.”

Capturing faba bean’s fabulous potential

A genomics springboard to help this minor crop become a major player in the Canadian cropping sector.

BY CAROLYN KING

As a high-protein, nitrogen-fixing crop with strong rotational benefits, faba bean has a lot going for it. Genomics research led by Dr. Nicholas Larkan aims to help unlock this pulse crop’s full potential for Western Canada.

“We are interested in helping to develop faba bean from what is quite a small crop by Canadian Prairie standards into a much larger and more important crop for producers,” says Larkan, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon, Sask.

He outlines the main reasons why faba bean is a priority for his pulse crop genomics program, which he started in 2020. “I think it is important to have options for producers for pulse rotations. Faba bean has a huge potential not only because of its high protein content and its use in the protein fractionation industry, but it is also the best nitrogen fixer among the pulses,” he explains.

“Faba bean produces 100 per cent of its own nitrogen required for its growing, plus it leaves a significant amount of residual nitrogen for the following crop. So, when we’re talking about climate-friendly crops, faba has potentially a really big role to play in reducing agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and requirements for nitrogen inputs, and also economic benefits for the farmer with the reduction in the required nitrogen.”

FIRST STEPS

Because genotyping – sequencing the DNA of an individual organism – is fundamental to genomics work, his research group’s first project was to evaluate different genotyping technologies and methodologies, even developing a couple themselves.

“We looked at how effective, cost-efficient and flexible the different technologies were so that we could come up with methodologies for use in our lab for the type of genetics we wanted to do going forward,” he says. His group assessed these methodologies with pea, lentil and faba bean, and also did a little work with dry bean.

They determined that their best option is a genotyping method called single primer enrichment technology (SPET) for faba bean. An international group of researchers released this faba SPET system as part of their 2023 publication of the first high-quality, fully sequenced genome, or ‘reference genome’, for faba bean.

“In our hands, the faba SPET system has been really effective,” notes Larkan. His group has already used this system for genotyping their faba lines, and the method also looks very promising for use with pea.

ABOVE Larkan (left) and his research assistant Kun Lou check faba lines at the AAFC Saskatoon Research Farm.

Photo courtesy of Trista Cormier.

DEVELOPING A FABA DIVERSITY SET

As soon as Larkan initiated his pulse crop genomics program, he also started gathering faba bean germplasm. “Initially, we tried to cast as wide a net as possible and accept as much germplasm as we could handle. We ended up with what amounts to the entire faba bean genebank collections of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Plant Gene Resources of Canada,” he says.

“However, one of the challenges of working with faba bean is that it has quite a high rate of outcrossing, so the material we get from genebanks tends to be heterogeneous.” In other words, a faba genebank accession (seed sample) often includes a mixture of genotypes. “So, we spent nearly three years producing single-seed descent lines from the material from the genebanks,” he explains.

With their stabilized genetics, these single-seed descent lines provide reproducible material for use in phenotyping work to assess traits of interest in the different lines through field trials over multiple years across multiple locations.

Larkan and his group began with about 650 genebank accessions from 55 countries and now have about

PARTNERS IN YOUR FIELD

Getting the most from your acres comes down to the smallest details, and we’re ready to prove we’re up to the challenge – even on your toughest acres. Whether it’s developing, researching, testing or getting to work in the field, PRIDE Seeds is there with you every step of the way.

600 single-seed descent lines. They have already genotyped these 600 lines using SPET. That work has generated an enormous dataset containing partial information on nearly every gene in the faba genome for every line.

They have used the genotype data to narrow the set of 600 lines down to just 300 lines that span about 99.7 per cent of the genetic diversity within the entire collection. Now, the group is using these 300 lines in Larkan’s current project, which is aiming to identify genes that influence some key traits in faba beans.

An essential step in this project is to collect phenotype data on the 300 lines. “In the last two years of the project, we’ll be doing replicated field trials at two different sites in two different years,” Larkan says. “The sites are at Lakeland College in Alberta and at AAFC Morden in Manitoba. We’ll be evaluating basic agronomic traits like yield, height, maturity, standability, and seed quality traits including shape, colour, protein content and starch content.”

Then they will bring together their genotype and phenotype data for the 300 lines to conduct what is known as a genome-wide association study (GWAS). GWAS is a way to find which gene variants, or alleles, are associated with specific traits of interest. That information can help breeders to bring these traits into their breeding lines.

Previous studies by other researchers have already identified some of the genes that influence certain faba traits, so Larkan’s group is looking at those traits with known genes in the context of the alleles in their set of 600 lines.

Larkan has collaborators on this project at AAFC in Saskatoon, Sask. and Morden, Man., the National Research Council at Saskatoon and Lakeland College. Project funding is under the Pulse Cluster of the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership, with government funding through AAFC and industry funding coordinated through Pulse Canada.

ASSESSING APHANOMYCES RESISTANCE

The field trials of the 300 lines in the current project will include plots in the Aphanomyces disease nursery at Morden. “Faba generally is considered to be resistant to Aphanomyces root rot, which is a huge advantage over crops like peas at the moment. We’re assessing our material for its resistance to Aphanomyces so that we can understand the genetics that control resistance in faba and maintain them going forward through the breeding processes,” explains Larkan.

“Plus, my lab also has parallel projects where we investigate the genomics of the Aphanomyces pathogen. We are looking at the potential interaction of different genotypes of the pathogen with the different pulse crops. It’s quite a big puzzle that we’re trying to process.”

A FAVOURABLE TIME FOR FABA GENOMICS

“The development of pulse genomics has been very rapid over the last few years; it is moving at leaps and bounds at present,” he notes.

Ongoing advances in sequencing technologies are making it more and more practical to sequence large genomes like the faba bean genome. The 2023 release of a faba reference genome is a valuable step forward for faba research. For example, the reference genome provides a standard for comparison with the sequences of other individual faba plants and makes it easier to assemble the sequences of those individuals. It helps in mapping the locations of genes that influence traits of interest.

Larkan and his group are leveraging their faba genomics data from the 600 lines with some other projects. For instance, they will be contributing material towards PanFaba, an international consortium to assemble a faba bean pangenome. A pangenome is the entire set of genes from many individuals in a species;

Larkan’s faba bean diversity set lines growing in a greenhouse at AAFC Saskatoon.