TOP CROP MANAGER

WASP VERSUS WEEVIL

A wasp’s potential to control the cabbage seedpod weevil

PG. 6

UNDERSTANDING PEAOLA

Think of it as a way to improve pea production

PG. 10

CANOLA FLOWER MIDGE UPDATE

Recent research on this new canola insect

PG. 22

A wasp’s potential to control the cabbage seedpod weevil

PG. 6

Think of it as a way to improve pea production

PG. 10

Recent research on this new canola insect

PG. 22

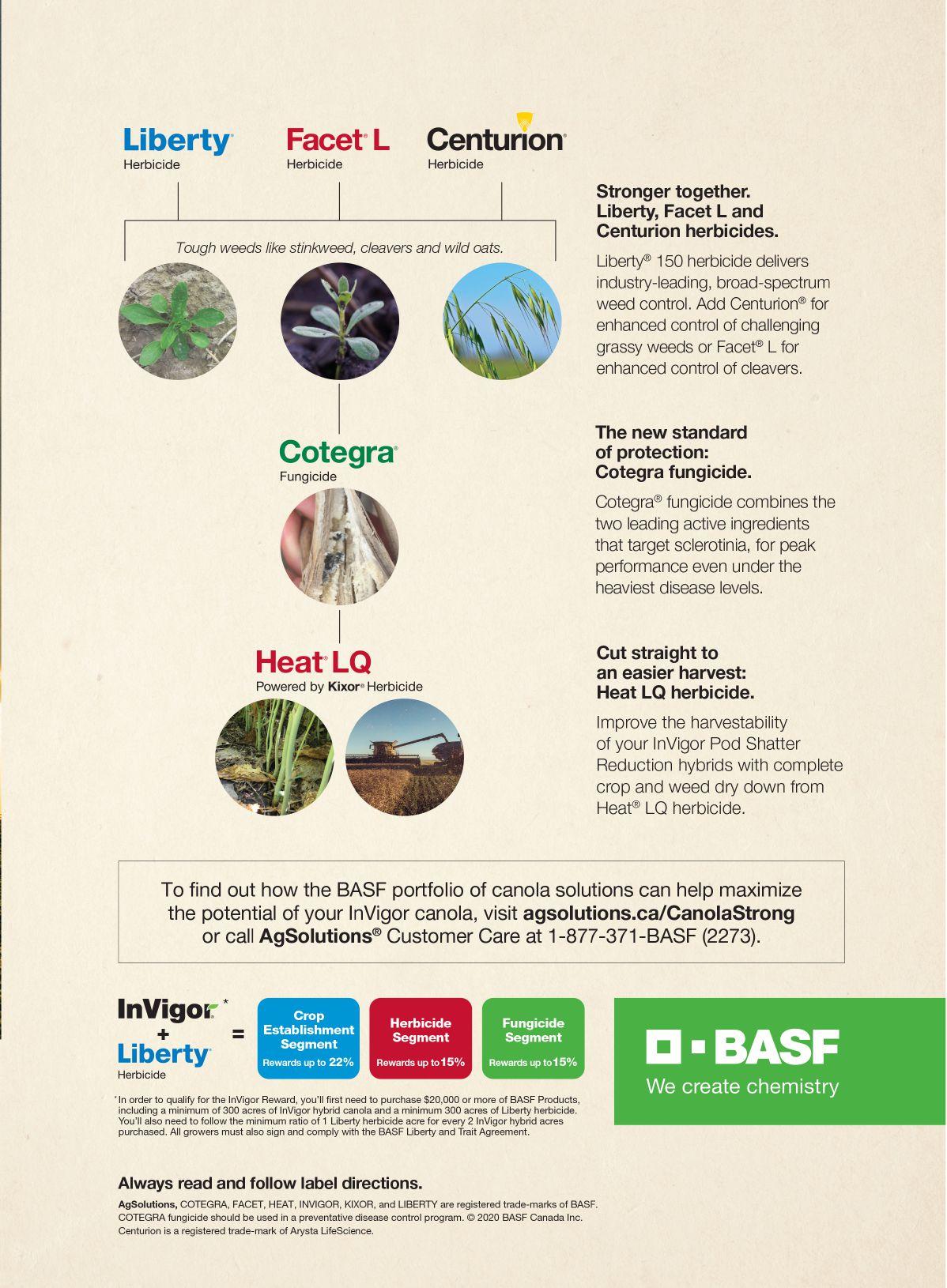

InVigor® hybrid canola growers refuse to settle for second best. At BASF, we share that philosophy. We’re proud to provide some of the most advanced solutions to support the needs of Canadian growers. Count on us to be there with our portfolio of canola innovations from seed to harvest – today and into the future.

A smart start: InVigor hybrid canola. For over 24 years, you’ve trusted InVigor to consistently deliver top yields and innovative solutions to your farm. Our ongoing goal is to continually raise the bar to provide you with better options to suit your individual needs.

PESTS AND DISEASES

6 | Wasp versus weevil

Could a tiny wasp have what it takes to control the cabbage seedpod weevil? by Carolyn King

4 The difference a year makes by Stefanie Croley

34 Blackleg disease yield loss modelled for hybrid canola by Bruce Barker

10 | Understanding peaola

Think of it as a way to improve pea production. by Bruce Barker

14 A new forecasting tool for Sclerotinia risk by Donna Fleury

18 Farming with big data by John Dietz

PESTS AND DISEASES

26 In pursuit of hirsute canola by Carolyn King

POST-HARVEST WEED CONTROL DIGITAL GUIDE

Our annual post-harvest weed control poster has gone digital! Our new, searchable guide allows you to easily select herbicide options for post-harvest weed control. Check it out online and let us know what you think on Twitter @TopCropMag. Visit TopCropManager.com/post-harvest-weed-control

Readers will find numerous references

PESTS AND DISEASES

22 | Canola flower midge: The story continues

Recent research expands our knowledge on this new canola insect. by Jennifer Bogdan

30 Verticillium stripe management in canola by Donna Fleury

32 De-greening the green by Bruce Barker

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

When I look back at news, tweets and notes from last year around this time, the general mood among the ag community was a lot less positive. Harvest was slow moving (to say the least), with Saskatchewan reporting only 69 per cent of the province’s crops in the bin by mid-October. Wet conditions, inconsistent weather and poor crop quality were just a few of the issues plaguing producers last fall during the affectionately named “harvest from hell.”

This year, by contrast, conditions were much more favourable for farmers across Western Canada. Saskatchewan producers enjoyed a long autumn season, with about 90 per cent of crops in the bin by early October, and Alberta and Manitoba farmers reported good harvest progress through late September and early October too. While lots of things about 2020 are different from 2019, this change is welcome – and much needed.

If you’ve been farming for a while, you undoubtedly have several years’ worth of notes, data and memories from your previous seasons. I bet you can recall a bumper crop year, or a mid-summer hailstorm that devastated your fields. Keeping track of this information and comparing trends and changes year-over-year not only makes for interesting shop talk, but it’s also helpful when it comes to making decisions for the future. Perhaps your strategies have stayed the same for several seasons, with weather being the only variable factor from one year to the next, but looking back at how you reacted to the challenges in your way can greatly impact how you move forward. Your barn may be full of equipment and supplies, but your farm data is a valuable tool to keep on hand too.

In this issue, we introduce Shift, a special supplemental section to the magazine with a focus on farm and agronomic technology. The stories in Shift are meant to highlight some of the ways technology – including data – is impacting modern farming, and how the industry is adapting. On page 14, you’ll read about a collaborative effort by Weather INnovations Consulting, the University of Manitoba and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, along with industry partners, to develop a tool to help forecast Sclerotinia risk in Western Canada. And, on page 18, we dive a bit deeper into how farm data is being collected and used in trials, on farms and in the equipment world.

As you shift (pun intended) into the next phase of your year, keep in mind how data and technology can impact what you do next spring. While you’re looking back on previous years, you may find new ways to look forward, too.

Could a tiny wasp have what it takes to control the cabbage seedpod weevil on the Prairies?

By Carolyn King

The cabbage seedpod weevil, an invasive canola pest, is spreading across the southern Prairies. However, a tiny parasitoid wasp has been keeping this weevil at bay in parts of Quebec – eliminating the need for spraying to control the weevil. Could this wasp be a sustainable, effective tool for managing the weevil’s populations in the west? A national project is underway to answer that question.

The cabbage seedpod weevil (CSW, Ceutorhynchus obstrictus) is not native to North America. Its first detection in Canada was in 1931, when it was found in British Columbia. “On the Prairies, the weevil was first detected in southern Alberta almost 25 years ago. From there, it spread mainly eastward and became established in the Swift Current-Maple Creek area. Since then it has crossed Saskatchewan and has recently been reported in Manitoba,” says Héctor Cárcamo, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta.

“Manitoba is not yet seeing large numbers of the weevil; usually it takes a few years for the insect’s population to develop. However, its

presence in Manitoba is a concern because Manitoba provides good habitat for the weevil, given the many acres of canola and the good moisture conditions, both of which seem to favour the pest.”

Interestingly, CSW has had very little northward spread on the Prairies. He says, “Although the weevil has been detected in central Alberta, we have not yet seen damaging populations there. I suspect that the winters are too long and the growing season is too short there for the weevil.”

In Eastern Canada, CSW was first found in Quebec in 2000 and Ontario in 2001. It has become a problem in canola fields in both provinces. “The eastern weevils seem to be from a different source than the ones we have in the west,” Cárcamo notes. “A University of Alberta student looked at the molecular biology and genetics of the two populations and found that they differed considerably from each other.”

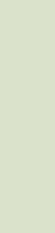

TOP: A national project is investigating the pros and cons of introducing a parasitoid wasp as a biocontrol agent for the cabbage seedpod weevil on the Prairies.

INSET: These little parasitoid wasps lay their eggs in the larvae of cabbage seedpod weevils, eventually killing the weevil larvae.

In southern Alberta, CSW is a chronic insect pest of canola, especially in fields that are planted early.

“The adult weevils arrive in large numbers at the flowering stage of the canola crop and feed on the pollen. The female usually lays one egg per canola pod when the pods are about an inch long. The larva develops inside the pod, eating the seeds. At the end of the larval period, it chews a hole in the pod and falls to the ground. It pupates in the soil. About two weeks later, the adult emerges and feeds on whatever immature pods of canola or other cruciferous plants are still available in the area,” Cárcamo explains.

“Then the adults migrate to overwintering sites like treed areas or field margins, wherever there is a lot of residue cover so they can hide. Usually in those habitats the temperature doesn’t go below -5 C. The weevils can supercool up to around -7 C, so they can survive the winter easily. As the weather warms in the spring, they emerge and feed on the buds and flowers of early-flowering cruciferous weeds. They move into canola fields as the canola plants begin bud

Cárcamo’s CSW research is aimed at developing more sustainable, effective ways to control this pest. At present, insecticides are the main strategy for managing CSW. His research group recently updated the economic threshold for spraying, which is now set at 25 to 40 weevils in 10 sweeps.

His group has also developed a cultural control method that uses a trap crop. “You can either plant two different cultivars at the same time – an early flowering cultivar along the field’s border and a lateflowering one in the rest of the field – or you can plant the border first and then the rest of the field later and harvest at two different times. The weevils concentrate in the early-flowering border, and you spray them with insecticides before they move into the rest of the field,” he explains. “However, we haven’t seen much adoption of that trap crop strategy, I think because growers find it a bit inconvenient. That is why we have turned our attention to biological control of the weevil using Trichomalus perfectus. is one of the most important

From almost any angle, the visionary design in Proven® Seed shines through. Our leading-edge technology offers a whole new perspective on canola, cereals, corn, soybeans and forages. Whether you’re looking for high yields and performance from every seed across all acres, or specific herbicide systems and disease management, we know there’s a Proven Seed that fits your vision of success. Only available at your local Nutrien Ag Solutions™ retail. Learn more at ProvenSeed.ca

natural enemies of the cabbage seedpod weevil,” Cárcamo says. This wasp lays an egg into a weevil larva. The egg hatches and the little wasp larva feeds on the weevil larva, gradually killing the weevil larva.

A few years ago, Cárcamo saw an article in Top Crop Manager about research by entomologist Geneviéve Labrie, who had found Trichomalus perfectus in Quebec in 2009 when she was starting her CSW research in that province. Peter Mason, an AAFC-Ottawa entomologist, found the wasp in Ontario in the same year. This non-native parasitoid had not been intentionally introduced in Canada.

Over the next few years, Labrie observed that Trichomalus perfectus was extending its range. By 2015, the wasp was present at almost 70 per cent of her study sites all around Quebec’s canola-growing areas. In fields with the parasitoid, it was providing such effective CSW control that growers no longer needed to spray for the pest.

These exciting findings made Cárcamo wonder whether the wasp could help control CSW in Western Canada. Since the wasp would likely take a very long time to spread naturally from Ontario’s canola fields to the Prairies, he initiated a five-year project to answer key questions around the pros and cons of deliberately introducing Trichomalus perfectus on the Prairies. “You need to get detailed data to assess the potential risks and benefits of introducing a species because, once you introduce it and if it becomes established, there is no way to recall it.”

For this project, which started in 2018, Cárcamo is leading a team of researchers from various agencies who are conducing field surveys, ecological studies and other analyses in Eastern and Western Canada. One possible concern about introducing the wasp had already been investigated before Cárcamo proposed his project. In the past, scientists had wondered whether the wasp, if introduced here, might also attack certain weevil species that have been introduced into Canada for controlling weeds like Canada thistle and scentless chamomile.

“But a few years ago, a European researcher named Tim Haye did a very extensive study on the host range of Trichomalus perfectus. He demonstrated that, although the parasitoid can attack several kinds of weevils, it will actually only go after weevils on the pods and seeds of plants in the Brassicaceae family, like canola and other crucifers,” Cárcamo says. So weevils that feed on non-Brassica plants like Canada thistle and scentless chamomile should be safe from the wasp.

One of the studies in Cárcamo’s project is a collaborative effort led by Cárcamo and Dan Johnson at the University of Lethbridge (U of L). A U of L graduate student is working on the project, and entomologists in Alberta and Saskatchewan are helping with sample collection.

This study consists of a survey of the different weevil species in Prairie canola crops and the natural enemies of these weevils; and an

examination of the ecology of CSW and its parasitoids on the Prairies.

From 2001 to 2006, entomologist Lloyd Dosdall led surveys of the native parasitoids of CSW in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan. Those surveys found a total of 15 parasitoid species attacking the weevil, including 14 species that parasitized the weevil’s larvae. At that time, only five per cent or less of CSW larvae were parasitized, and total parasitism of CSW was generally less than 15 per cent.

“So far, our student is finding similar results; the level of parasitism by native wasps has not increased very much,” Cárcamo says. “So there is still room to introduce another parasitoid that could perhaps help bring the cabbage seedpod weevil under control.”

Because Trichomalus perfectus is already present in Ontario and Quebec, the collaborating researchers in those provinces are able to investigate the wasp’s actual behaviour in the field. In both provinces, they are collecting the larvae of the different weevil species found in canola and other Brassica plants, and determining which weevil species are being attacked by the wasp. In Quebec, the researchers are also evaluating how effective this parasitoid is in controlling CSW, and they plan to analyze the parasitoid’s economic impact on Quebec canola production. The Quebec researchers are also studying the overwintering biology of CSW and Trichomalus perfectus, which will increase understanding of the two insects and their potential spread in Canada.

According to Cárcamo, one of the challenges so far is that the canola acres in these two provinces have dropped in the last couple of years. As a result, the researchers are finding that the populations of both the weevil and the parasitoid have declined.

Another component of the project involves modelling to predict where the parasitoid wasp might become successfully established.

A few years ago, Tim Haye and several AAFC researchers, including Owen Olfert, Peter Mason and others, used advanced bio-climatic modelling to predict the potential distribution of Trichomalus perfectus if it were introduced in Canada. According to that analysis, some of Canada’s canola-growing regions are potentially suitable for this parasitoid to become established. However, Canadian conditions would not be as good as for the wasp as the conditions in parts of Europe, and the southern Prairies would be less suitable than Eastern Canada.

“Now that we have the parasitoid in more areas in Quebec and Ontario, we can refine and validate that model using the current distribution of the parasitoid in Eastern Canada,” Cárcamo explains.

“That might allow us to see if there are some specific habitats [in the southern Prairies] where the wasp could become established. [For example, perhaps irrigated fields might provide better conditions than the hotter, drier surrounding lands.] And those would be the areas where we would release the parasitoid.”

The project also includes studies in Alberta and Quebec to understand how different landscapes affect CSW, lygus bugs and their natural enemies. The field sampling for these studies involves taking a number of sweeps at a given point in a canola field to determine the insect community at that location, and then collecting habitat data within a two-kilometre radius of the sampling point.

The researchers will analyze the collected information to see how factors like crop rotations and plant species in natural areas relate to the abundance of the pest, the amount of crop damage by the pest, and the abundance and effectiveness of the pest’s natural enemies. “For instance, if a natural area near a crop field has wild flowers where parasitoid wasps can feed on nectar, then these wasps might have more energy to fly and attack the pest in the crop. Or an uncultivated area that is not sprayed with an insecticide might have increasing populations of beneficial predator insects that could move into the crop.”

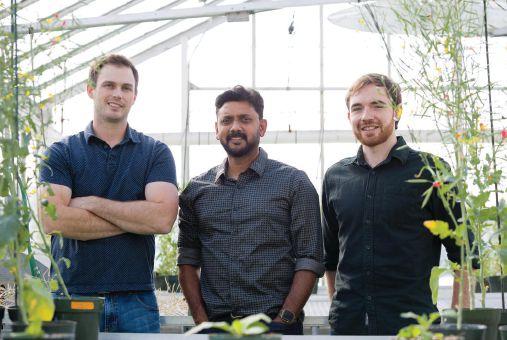

Think of it as a way to improve pea production.

by Bruce Barker

Who wants change for the better? Most people do. But who wants to change? That’s a tougher question, especially as it relates to intercropping a mixture of pea and canola. While some farmers are making that change, the big production barrier is the need to clean peaola production at harvest – a bottleneck that can slow harvest progress.

“The way I look at peaola is that it is a better way to grow peas, while canola is a less important part of the production system. If you’re going to compare peaola to monocrop canola, any time canola prices are strong, canola is going to win on profitability,” says Scott Chalmers, diversification specialist with the Westman Agricultural Diversification Organization (WADO) in Melita, Man.

Chalmers has a large body of peaola research that goes back to 2009 looking at seeding rates, nitrogen and phosphate application, row orientations, fungicide applications, and intercrops of pea with crops other than canola. He is continuing research in 2020 and beyond to further refine peaola production.

The main consideration is whether more money can be made with pea and canola grown together. Chalmers has found that moisture drives the benefits of peaola yield. He says when moisture is adequate to above normal, generally intercrops perform better together than as monocrops. Chalmers has found that intercrops use more water, such as in pea-canola. “Perhaps in 2011, when we had excessive moisture, the intercrops performed better as they were more able to survive heavy rainfalls, whereas the monocrops were more prone to waterlogging.”

He says timing of the moisture is also critical. It must be present for both crops at peak growth periods. If this does not happen, the other crop will “cannibalize” the resources. For example, peas will have the upper hand if the early spring is dry.

Profits also vary more if it is dry because the yield potential is not there, and there is the additional cost of separating the seed.

“If canola markets are in favour of the farmer, then it makes sense to fertilize monocrop canola to its potential rather than working within the small marginal benefits of peaola, or conversely when pea margins are low. However, when pea prices are strong and canola is average to below average, this peaola systems makes more sense,” Chalmers says.

Chris Holzapfel, research manager with the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) in Indian Head, Sask., also researched peaola production from 2010 through 2012 with five site-years of data. Generally, he saw the same interactions of yield

potential and commodity prices on peaola profitability.

“I agree profitability would depend a lot on relative commodity prices and, in general, monocrop canola can be a tough one to compete against when it has decent yields and prices,” Holzapfel says. “I have suggested in the past that perhaps growing a type of pea that is higher value but difficult to grow as monocrops (i.e. Maple peas) might make more sense than using yellows, which are generally lower value and well adapted to monocrop when using modern varieties.”

Over the last decade of research, Chalmers and Holzapfel have

DREAM. GROW. THRIVE.

We’re FCC, the only lender 100% invested in Canadian agriculture and food. That means we’re invested in you, with financing and knowledge to help you achieve your dreams.

seen agronomic advantages and disadvantages of peaola:

1. Mixed rows offer higher yield than alternate rows, and less so paired or triple rows of individual crops – the thought was there would be less competition between the crops in separate rows, or that canola would receive preferential access to N. This wasn’t the case.

2. Applied nitrogen has little effect on overyielding of the system. Adding N fertilizer favoured an increase in canola yield but not pea yield. Nitrogen fertilization also reduced the number of pea nodules and N fixation. Chalmers doesn’t recommend N fertilizer when targeting higher pea yield in the peaola crop.

Bayer CropScience, LP is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Bayer products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Bayer's Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. Trecepta® RIB Complete® Corn has been approved for import into Australia/New Zealand, Colombia, China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Taiwan, United States and all individual biotech traits approved for import into the European Union. Please check biotradestatus.com for trait approvals in other geographies. Any other Bayer commercial biotech products mentioned here have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from these products can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for these products. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® Technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate. Roundup Ready® 2 Technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate. Roundup Ready 2 Xtend® soybeans contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate and dicamba. LibertyLink® Technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glufosinate. Glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Dicamba will kill crops that are not tolerant to dicamba. Glufosinate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glufosinate. Contact your local crop protection dealer or call the technical support line at 1-888-283-6847 for recommended Roundup Ready® Xtend Crop System weed control programs. Insect control technology provided by Vip3A is utilized under license from Syngenta Crop Protection AG.

FOR CORN, EACH ACCELERON® SEED APPLIED SOLUTIONS OFFERING is a combination of separate individually registered products containing the active ingredients: BASIC is a combination of fluoxastrobin, prothioconazole and metalaxyl. STANDARD is a combination of fluoxastrobin, prothioconazole, metalaxyl and clothianidin. STANDARD plus DuPont™ Lumivia® is a combination of fluoxastrobin, prothioconazole, metalaxyl and chlorantraniliprole. COMPLETE plus DuPont™ Lumivia® is a combination of metalaxyl, chlorantraniliprole, and prothioconazole and fluoxastrobin at rates that suppress additional diseases. BioRise™ Corn Offering is the on-seed application of either BioRise™ 360 ST or the separately registered seed applied products Acceleron® B-300 SAT and BioRise™ 360 ST. BioRise™ Corn Offering is included seamlessly across offerings on all class of 2019, 2020 and 2021 STANDARD, STANDARD plus DuPont™ Lumivia®, and COMPLETE plus DuPont™ Lumivia® corn hybrids. FOR SOYBEANS, EACH ACCELERON® SEED APPLIED SOLUTIONS OFFERING is a combination of registered products containing the active ingredients: BASIC is a combination of prothioconazole, penflufen and metalaxyl. STANDARD is a combination of prothioconazole, penflufen, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. STANDARD plus Fortenza® is a combination of prothioconazole, penflufen, metalaxyl and cyantraniliprole. Optimize® ST inoculant is included seamlessly with both BASIC and STANDARD offerings.

Acceleron®, Bayer, Bayer Cross, BioRise™, BUTEO™ RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design™, Roundup Ready 2 Xtend®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb® Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup Xtend®, SmartStax®, Transorb®, Trecepta®, TruFlex™, VaporGrip®, VT Double PRO® and XtendiMax® are trademarks of Bayer Group. Used under license. Lumivia® is a registered trademark of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. JumpStart® and Optimize® are registered trademarks of Novozymes. Used under license. DuPont™ and Lumivia® are trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company or its Affiliates and are used under license by Bayer Group. LibertyLink® is a registered trademark of BASF. Agrisure Viptera®, Fortenza® and Helix Xtra® are registered trademarks of a Syngenta group company. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of BASF. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Respect the Refuge and Design is a registered trademark of the Canadian Seed Trade Association. Used under license. Poncho® and VOTiVO® are registered trademarks of BASF. Used under license. ©2020 Bayer Group. All rights reserved.

3. Applied phosphorous (in deficient soils) provided additional peaola yield benefits, and produced more pea nodules with increasing rates. Yield of both pea and canola were increased, with overall grain production rising from 43 bushels per acre with no added P to a significantly higher yield of 49 bushels per acre with 30 pounds of P2O5 per acre in two years of trials at WADO.

4. Peaola offers significant protection against pea aphid infestations compared to monocrop peas. WADO research found that monocrop pea had about 16 aphids per plant in 2017 compared to about two aphids in peaola stands.

5. In a peaola crop, peas stand taller to allow a higher cutting height. In addition to ease of harvest, the stubble left behind after harvest can catch more snow compared to monocrop pea. Monocrop pea often has little standing stubble left and can be prone to soil erosion and “spring drought.”

6. Peaola can reduce seedborne disease from Ascochyta compared to monocrop peas. In WADO research, monocrop pea had 16.5 per cent Ascochyta diseased seed compared to 2.25 per cent when peaola was sown in single rows.

7. Clearfield canola is grown in peaola crops so that Odyssey herbicide can be used for weed control. The denser peaola stand can mean a more competitive crop and improved weed control than in monocrop pea.

8. Experience has shown that pea is more frost-tolerant than canola in the peaola crop. This can offer “intrinsic” crop insurance against spring frost in peaola stands so that, if the canola is damaged by frost, the pea crop may still continue to grow so that the farmer doesn’t have to reseed their field.

9. WADO research found that broadcasting alfalfa before or after seeding peaola established a satisfactory stand of alfalfa. The addition of alfalfa may provide an advantage on saline, saturated areas where peas or canola do not grow well. Chalmers says these benefits are difficult to measure in small plots but may be realized in field-scale conditions.

10. Pea and canola have complimentary rooting depths. Pea is shallow-rooted

while canola’s taproot reaches much deeper into the soil profile. This allows peaola to more thoroughly access soil moisture deeper in the soil profile than pea alone, and may offer a way to reduce salinity and grow more crop during excessive moisture conditions.

1. Extra work seeding and separating crops, leading to extra labour or time.

2. Bottlenecks during harvest at the separator.

3. Somewhat more wasteful on inoculant inputs (compared to monocrops) if a granular type is used.

4. Fewer weed control options, since LibertyLink and Roundup Ready varieties cannot be grown, unless Edge is used for pre-emergent weed control. The Clearfield canola option is challenged by Group 2 resistance found in kochia, cleavers, barnyard grass, chickweed, cow cockle, yellow foxtail, hemp-nettle, lamb’s-quarters, ball mustard and wild mustard.

5. Canola rotations are already very tight in Western Canada, and adding canola to a pea crop means the rotations are tightened further. This can result in an increased risk of diseases like blackleg and clubroot in canola, or Aphanomyces in pea.

A possible solution to the cleaning bot-

tleneck at harvest is to store peaola until after harvest and then separate the crops. For example, if both crops are dry – canola at nine per cent and pea at 15 per cent – PAMI suggests the crops could be safely stored until they can be separated. They have done some theoretical calculations on peaola based on the equilibrium moisture content relationships of each grain type; if both monocrops are considered dry and cool (less than 15 C) when stored, then the risk of moisture migration between the two crop types should be low.

“We have just proposed a research project to a funder to answer this exact question for peaola storage and other intercrop combinations as well,” says Charley Sprenger, project leader with Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute (PAMI) in Portage la Prairie, Man.

Overall, peaola is working for some farmers, but it isn’t for everyone. “Don’t compare peaola to monocrop canola, because canola is such a monster crop. Peaola is really about the pea crop and growing [it] as an intercrop can help improve pea profitability when pea prices are strong,” Chalmers says.

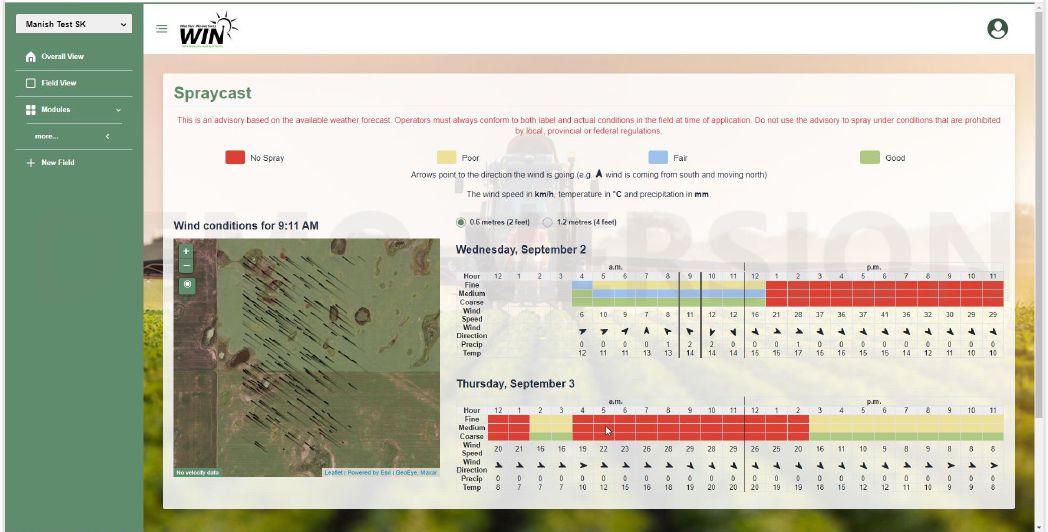

A new web-based tool provides growers with decision support for forecasting canola growth stage and Sclerotinia risk in Western Canada.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Sclerotinia stem rot is a highly unpredictable and weatherdependent disease. It’s an ongoing concern in all canolagrowing areas of Canada. Although foliar fungicides remain the main control strategy at flowering, the variability in disease occurrence and severity, and narrow window for fungicide application, add to the complexity of managing risk.

A collaborative research project led by Weather INnovations Consulting (WIN) was initiated to develop reliable Sclerotinia stem rot risk and canola growth stage forecasting models. Along with risk assessment, the models would also provide an estimated date when the canola would reach 14 different growth stages. Once developed, these models will provide canola growers with decision support to apply or forgo fungicide application.

The five-year project included both small-scale experimental trials and large-scale field trials at multiple locations across

three Prairie provinces during 2013 to 2017 to collect site-specific disease, agronomic and weather data. The project was led by Rishi Burlakoti and Neal Evans from WIN in collaboration with researchers from the University of Manitoba and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Saskatoon. The field trials also included industry partners Bayer Crop Science and Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF), with funding from the Canola Council of Canada.

“The replicated small plot trials included three canola varieties representing short-, mid- and long-season cultivar groups, while the field-scale trials had one cultivar,” explains Burlakoti, a research scientist currently with AAFC in Agassiz, B.C. “We installed time-lapse cameras at all sites to record pictures of canola growth stages each day, along with manual observations once a week. Weather data from each field was also recorded. Sclerotinia disease was monitored periodically after flowering stage until swathing was completed. We also

included sclerotia depots developed by AAFC researcher Lone Buchwald and counted sclerotia germination of apothecia at one location in Manitoba.”

The model development was based on the data collected from the field trials and also considered the principles and factors used by Sclerotinia models developed in other areas, such as in France, Sweden, Western Canada and the USA. The model also considered agronomic factors, such as previous crop history, disease history, plant density, varietal resistance and weather factors, such as temperature, number and frequency of rainfall and daily wetness hours. Accumulated growing degree days, physiological days and crop heat unit (CHU) models were compared for 14 selected crop stages from emergence (BBCH 9) to ripe (BBCH 89).

“We selected physiological days as the best model for predicting the phenology or growth stages for short-, mid-, and long-season varieties,” says Manish Patel, president of WIN. “Our model is unique in that it includes an integrated forecasting model to predict critical growth stages during flowering (BBCH 60 and BBCH 65), which is the most critical stage for the pathogen to infect the crop.

“The model uses weather data during flowering stage (-2 to +2 weeks of BBCH 65), combined with the various agronomic factors, to calculate the infection risk of Sclerotinia stem rot. The weather data is refreshed on an hourly basis using our own WIN networks and freely available data from other services like Environment Canada. We rely on about 3,600 weather stations across the Prairies and in Ontario on a grid of about four by four kilometres, which are integrated with a GIS system to provide field-specific information.”

Patel adds, “We are partnering with IBM on weather forecasting, as they have the computing power and resources to run weather forecasting on an hourly basis, as compared to other traditional resources that typically only run every six or 12 hours.”

Canola growers can register for free on the website and get sitespecific forecasting of Sclerotinia infection risk. Basic information, such as planting date, cultivar, soil type and number of years canola was planted over the past six years in rotation with other crops is required. This platform, developed by WIN, will compile field-specific observed weather data and forecasted weather data, which is then fed into the model. Based on the information supplied by the end-user and both historic and forecasted weather, the model determines the

risk base for the end-user, showing as a colour risk dial of green, yellow or red, depending on risk level.

The Sclerotinia model is integrated with the growth stage model, and these models will help canola growers make fungicide spray decisions in managing Sclerotinia stem rot. The model will also reduce the number of unnecessary sprays if weather conditions are not suitable for disease development, which will ultimately help to reduce the environmental impact.

“Growers can register their fields as soon as the field is planted or later – as long as it is before flowering and the correct planting date is provided,” Patel explains. “The system monitors and integrates the observed weather for the specific site and provides the phenology of the crop. Growers can actually monitor their crop from planting date through to harvest with the platform. The model will forecast when the crop will begin flowering around BBCH 59-60, which is when growers should also start scouting their crop in the field to see how it is progressing.

“The system provides information at different stages of the crop – from the start of flowering, through different per cent levels of flowering to the end, and the risk of infection every day. If growers start scouting their field and see that the model doesn’t quite match, such as it shows the crop is just starting to flower but the field is more advanced, growers can go into the website and change the information, which will reset the model. The grower could then use this information towards the decision-making process for the field in terms of

We installed time-lapse cameras at all sites to record pictures of canola growth stages each day, along with manual observations once a week.

spraying. WIN also provides supplemental tools, such as SPRAYcast, that could be used to determine the ideal conditions for spraying as well.”

Although the Sclerotinia model is currently only available for canola, there will be future opportunities to expand to other crops, such as soybeans and dry beans, in which Sclerotinia stem rot is a significant concern. Growers will find the growth stage tools useful for other agronomic operations, such as spraying herbicides, identifying key growth stages for pest damage and swathing. WIN also has a BINcast model that helps monitor crops after harvest in bin storage, providing current ECM conditions as well as a forecast for the next five days.

“One of the things that sets this model apart is that the information and data is regularly updated and the models are retrained,” Burlakoti says. “Weather conditions and observations can be variable, and Sclerotinia is highly variable with lots of microclimate differences, so

it is important to retrain the model based on additional research information. As new cultivars are registered, they are added to the model. Regular updating of new data and research information from researchers and agronomists helps to keep the model highly accurate.”

“We are also working closely with Lone Buchwald at AAFC to explore funding opportunities to create a dedicated app for both Android and Apple for this tool,” Patel adds. “At WIN we believe in keeping our tools free for agriculture end-users, so farmers have free access to the range of tools available. We work on B2B relationships in terms of sponsorship for the tools with various industry partners.

“Growers can access this new Sclerotinia web-based risk tool for free at www.canoladst.ca or at WIN’s www.decisionfarm.ca, where additional free tools are also available for growers to plot various crop fields and receive field and crop-specific advisories for various factors, such as pests, diseases, growth stage, optimal storage conditions and other risks.”

A teacher, farmer and software engineer discuss the future of managing streams of digital data on farms.

BY JOHN DIETZ

Easy-button” farming with big data may seem like science fiction, but it’s not far away.

Many farms and ranches already use technology that creates an abundance of digital data on multiple platforms. However, a lack of program-to-program compatibility and (corporate intellectual property rights?) make it complicated to combine this data in a usable way.

What do an Alberta college, a farmer from Moosomin, Sask., and a software engineer have in common? They’re all determined to be ahead of the curve when it comes to smart agriculture. Whether designing, testing or using the latest big data ag solutions, they are committed to making operational decisions with the assistance of smart ag technology.

The Smart Farm was started by Olds College in Olds, Alta., in 2010. Its mandate is to use leading-edge technology to demonstrate how to grow crops and manage livestock better. Giving students the opportunity to work with experimental agtech, it offers a post-diploma certificate in agriculture technology integration and a diploma in precision agriculture “techgronomy.”

“We can demonstrate almost any kind of leading-edge technology you can think of right now,” says Alex Melnitchouck, chief technology officer of the Smart Farm. “One of our goals is to bring in the best technologies from around the world, implement them and use them for applied research.”

The farm’s newest machine technology is the DOT Power Platform. Researchers and students are evaluating the autonomous equipment platform for its technical, economic and environmental footprint using multiple technological metrics.

“DOT is fully integrated into the Smart Farm operations. One field where we have many layers of data was seeded by DOT and sprayed by DOT in 2020,” Melnitchouck says.

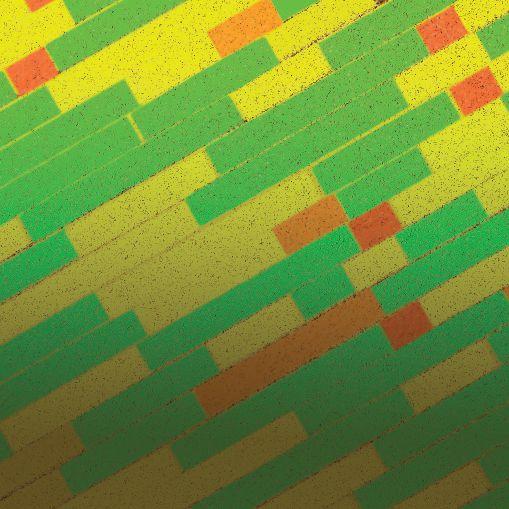

The Smart Farm recently began working with hyperspectral and thermal imagery. Compared to the traditional red-green-blue or near-infrared imagery, the hyperspectral analysis includes between 12 and 500 spectral bands that allow for a much more detailed analysis of crop conditions. Thermal imaging allows for instant and accurate stress detection in field crops.

The Smart Farm collects these growing season images with a drone, and also accesses images from the Teledyne DESIS sensor on the International Space Station.

“We’re trying to figure out applications of spectral analysis for applied farming – like detecting nutrient deficiency or water content. Otherwise, it will be a custom-based tool and way too expensive,” Melnitchouck says. “Application to farming is a bit of a grey area. Eventually, you want to bring benefits to real farming on the Prairies.”

Even perennial problems, like establishing an appropriate fertilizer rate mid-season to achieve high yields, are addressed by researchers working with big data. The Smart Farm has several sensors measuring real-time air and in-ground temperature and moisture levels. In 2020, a highly experimental sensor from Teralytic was added to the Smart Farm’s toolbox. It is supposed to provide real-time data on nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) in the soil.

“This year, we started with one field and collected a highdensity soil grid by sampling every acre,” Melnitchouck explains. “The data includes over 20 different soil characteristics: organic matter, pH, N/P/K, calcium, magnesium, micronutrients and base saturation. We also did soil electro-conductivity mapping and collected several hyperspectral images. Combining all those layers, we can address many questions.”

However, software compatibility remains an issue. “To do pretty much anything on the Smart Farm, I still have to use more than 10 programs and they’re completely different. I hear about integrating

Because ads don’t deliver yield. For that, you need the latest technology, locally tested. The Brevant™ canola lineup is designed to be flexible, giving you the right agronomic and marketing options for your business. So, get to your local Brevant™ retailer and get the seed you need, without the fluff.

We work hard to make your choice easy.

Visit your retailer or learn more at brevant.ca

yield information with weather data, but how? The two types of information are used for completely different purposes.”

The Smart Farm isn’t equipped to develop new data-integrating software, but it tries to be objective and explain concepts for integrating data streams. “In everything, we try to make sure that anything we do could be replicated anywhere on any farm,” Melnitchouck adds, noting a program starting this fall is a combination of high-tech and practical applications.

“We want [students] to be empowered by knowledge and expertise to choose what exactly works for their farm. We’re trying to explain the most complicated things in agriculture in very simple words or terms.”

Around 2010, Kristjan Hebert returned to his family’s 4,500-acre farm at Moosomin, Sask., ready to farm after a short career in accounting. Now, he’s a managing partner of Hebert Grain Ventures, a 22,000-acre operation with malt barley, hard red spring wheat, canola, yellow peas and fall rye, and co-founder of Maverick Ag, an agricultural financial business risk management and consulting company in Saskatoon that uses diverse data in their operations.

“Big data might get you headed in the right direction, but until you start collecting that data locally and on your own farm, it’s really hard to use it to affect a decision – and decisions are what make us money,” Hebert says.

There are four types of data for farming purposes: financial, machinery, agronomic and market-related. Each type has specific variables, and quite often, the variables don’t talk to each other and the types don’t connect at all. To make his decision-making easier, Hebert wants an approach that synchronizes data between platforms.

“My yield data from my combine automatically pulls into [the combine’s platform]. For that to automatically pull over to my accounting platform, it has to have an API (application program interface). It doesn’t go automatically from place to place, so you have to manually do it. When you try, you end up double-typing and having a lot of overlap,” he says.

Hebert’s ideal set-up would involve three screens from which he can run his whole operation. “One screen has your live agronomytype data, like soil moisture, growth stage, heat units, the yield trend and it recommends decisions for today. The middle screen has all your people and equipment data. You quickly look there and see you’ve got two sprayers free and two operators free. If you check the ‘Yes’ box, work orders go out automatically to the sprayers and the operators. Your third screen is financial. It automatically pulls in the costs to run the sprayers and the costs for the fertilizer. It also increases the expected revenue on your pro forma based on the results of that action. To me, that’s how it flows across. That’s how this customer wants it to work.”

Eric Smith is the engineering manager of precision agriculture at the Winnipeg headquarters of JCA Electronics. As an original equipment manufacturer supplier to implement and machinery makers, JCA Electronics is often contracted to develop application systems.

We’re trying to figure out applications of spectral analysis for applied farming – like detecting nutrient deficiency or water content.

“Typical projects are in the autonomy area, and we do everything from developing control software to ISOBUS-compatible systems, to mobile apps and cloud systems,” Smith says. “We manage data from sensors on equipment all the way up to the cloud.

“Everybody wants to use data and a ton of data is available, but the challenge is to get the data off the machine and from different machine manufacturers. Most of it talks to other stuff from the same company and nobody else. Quite often you can’t get the data off your machine and into the cloud [but] that’s starting to change. These companies are starting to talk together and working on technologies that allow cloud systems to talk to one another and allow farmers to get their data into the cloud.”

Smith says it is to everyone’s advantage to push for compatible communication standards like ISOBUS, which is a standard from the 1990s for farm electronics.

“It will help everybody and allow farmers to choose the best product instead of sticking with a single colour,” he says.

Getting the streams of big data to merge into the format that Hebert would like to see on three screens isn’t far-fetched anymore, Smith says. Some of the technology Smith has worked on goes even further beyond Hebert’s dream.

“A couple of years ago we investigated augmented reality and came up with an interesting application using Microsoft HoloLens so you could visualize your application data,” he says.

HoloLens 2 was introduced commercially in February 2019. It is a ‘mixed reality’ operating system using the Windows 10 platform and a head-mounted display, or smart glasses.

“The HoloLens is like a big set of glasses that you put on your head. You still can see reality behind it, but things can be drawn and added to what you see. For this proof of concept, we created an artificial field and created a tractor to drive a path on that field back and forth,” Smith says. “Then we generated data as if you were driving a path on the field and overlaid that data on top of the field. Then we took it a couple of steps further.”

The HoloLens empowers the use of voice commands to talk to and control the data simulation. When the API is further developed, in theory a person could operate several DOTs sitting at one desk, knowing exactly what each is doing. The machine app could be augmented with real-time agronomy and weather data.

Smith believes that with accurate geotags, various streams of data can be collected and visualized for operators to have a greater understanding of what’s happening on a farm.

“I think AR (augmented reality) for farming will be here soon. It’s just a matter of time.”

What’s behind boldness? Confidence. And with a powerful new active ingredient, new Miravis® Bold fungicide is built for long-lasting Sclerotinia protection so you can grow canola that stands up to disease—and clearly stands out.

Recent research expands our knowledge on this new canola insect.

by Jennifer Bogdan

When a new insect species is discovered, the questions are many and the answers are few.

Galls on flowers created by midge larvae found in canola fields in northeast Saskatchewan since 2012 were first thought to be caused by swede midge (Contarinia nasturtii). It wasn’t until 2016 when Boyd Mori, now assistant professor at the University of Alberta, confirmed that this midge was actually a new species. The new midge species, now known formally as Contarinia brassicola and informally as “canola flower midge”, was officially described in 2019 by Mori and colleagues.

“There is still much to learn about canola flower midge. We have yet to see many fields with economic damage but we don’t know what conditions could lead to more large-scale damage, and this is concerning. We need to learn more about the midge

overall to determine if it may become a larger issue, and how we could manage it in the field,” Mori says.

Research on the distribution and biology of canola flower midge has been completed in a project co-led by Mori and Meghan Vankosky, research scientist with Agriculture and AgriFood Canada in Saskatoon. The objectives of this project were to determine the distribution of the midge across the Prairies, investigate its life history and population genetics, and to identify any natural enemies of the midge.

Canola flower midge occurs across the Prairies

“When we started this project, we really wanted to know where canola flower midge is on the Prairies so we could get some kind

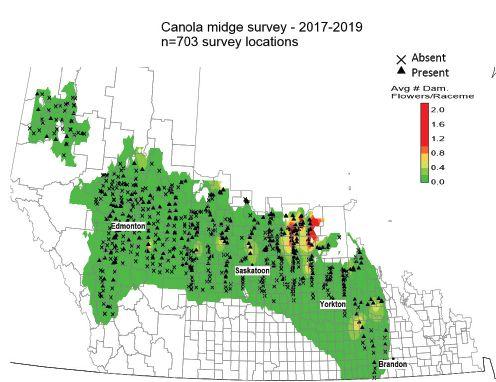

of idea of risk for canola growers,” Vankosky says. The survey was carried out from 2017 to 2019. Canola flower midge was detected across the Prairies, from the Peace River region in Alberta to Brandon, Man., but appeared in very low densities across the vast majority of its range (Figure 1). The highest canola flower midge populations were found in northeast Saskatchewan, where the insect was first discovered. Canola flower midge also seems to have a greater presence in the prominent canola-growing areas typical of the Gray, Dark Gray, Black and Dark Brown soil zones. There were no swede midge detected in pheromone traps and no swede midge symptoms found in the fields throughout all years of the study. These observations further confirm that swede midge does not occur in the Prairie provinces.

Two generations of midge produced during the growing season

Emergence cages were set up early in the growing season on current year canola fields and previous year canola fields (canola

We think of seed design as both a science and an art. Proven ® Seed offers a full range of leading-edge LibertyLink ® , TruFlex™ Roundup Ready and Clearfield canola hybrids that are all designed for disease management, high yields and consistent performance. No matter what you’re looking for, there’s a Proven Seed canola hybrid for your farm. Only available at Nutrien Ag Solutions™ retail. Visit ProvenSeed.ca/canola to learn more.

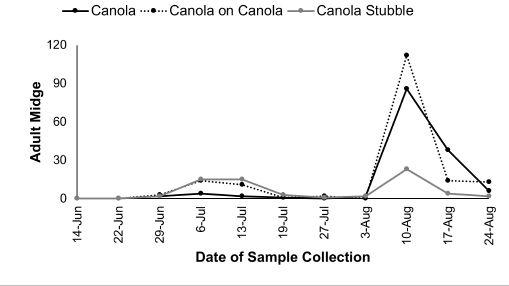

Figure 2: Adult canola flower midge activity in 2018. The number of adult midges reported are the cumulative total collected from all emergence cages during each week (not an average total per cage).

3: Galled canola flowers concentrated at the top of the raceme are the result of damage from the secondgeneration of canola flower midge larvae. Damage at this later crop stage is not nearly as economical as earlier first-generation damage, since later flowers do not always translate into harvestable pods for a variety of reasons, as evident by the small pods surrounding the galled flowers on this raceme.

stubble). Adult midge were recorded and two peaks of flight activity were observed in all three years of the project, suggesting that canola flower midge undergoes two generations per year on the Prairies (Figure 2).

“The first peak occurs around mid-to-late June, when adults emerge from their overwintering cocoons in the soil. These adults mate and lay their eggs on or near canola buds, or tucked

inside opening canola flowers. Larvae were only found inside the developing canola flowers and their feeding results in galled flowers that do not produce pods. These larvae drop to the soil to pupate. Then a second peak of adult activity occurs in late July to early August, when a second generation of adults emerges,” Vankosky explains.

In studying the biology of canola flower midge, Mori and Vankosky also attempted to estimate the impact of the midge on canola yield. This proved difficult to do in field conditions because midge populations have patchy distributions, both in and between fields. The vast majority of fields surveyed between 2017 and 2019 had no more than one galled flower per raceme, so the risk of economic yield loss was generally low. However, some fields were observed with much higher levels of damage, where yield loss might have occurred. “We still don’t know how the midge is distributed within fields, such as at the edges versus the middle of the field,” Vankosky says.

According to Vankosky, “It is the first generation of midge that will have the greatest impact on yield because their larvae are damaging flowers during the early flower stage of the crop. By the time the second generation of midge is present, the crop is nearing the end of flowering so the larvae are likely damaging flowers that would otherwise perhaps produce smaller pods or pods that would still be immature when the crop is harvested.”

Population genetic analyses of multiple canola flower midge specimens collected during the survey revealed a high genetic diversity among the midge populations across the Prairies. In total, there were 17 different haplotypes (unique DNA sequences) identified from 16 sampling locations, with Saskatchewan and Alberta having the most diversity, followed by Manitoba. This genetic diversity could provide some evidence that the canola flower midge is a native species, since invasive species typically have low genetic diversity in their invaded range compared to their native range.

“Maybe the canola flower midge is native or maybe it’s invasive and we just haven’t noticed it here at these low levels for such a long time. There is definitely more research needed to determine whether it is a native species or not,” Mori explains.

Two parasitoid species, Inostemma spp. and Gastrancistrus spp., have previously been identified attacking canola flower midge larvae in Saskatchewan. Out of the three years of the study, the greatest levels of parasitism occurred in 2017 and ranged from zero to 33 per cent. Vankosky says that the parasitoids are in the queue to be identified to the species level, by expert taxonomists.

A lot of previously unknown information has been gathered about canola flower midge since its confirmation as a new species. Mori concludes, “This research makes farmers aware that canola flower midge is present throughout the Prairies, but so far [it] has not been a big issue with canola production other than in a few fields over the past 10 years. At least, it’s on our radar. The more we learn about canola flower midge now, the more information we’ll have to help us figure out how to manage it later if it does start causing more damage.”

• STATE OF THE ART DIGITAL PROGRAM

• CROP PLANNING AND SAMPLING

• FIELD SCOUTING AND RECORD KEEPING

• SATELLITE IMAGERY

• INTEGRATES WITH MULTIPLE PLATFORMS

AVAILABLE AT

By Carolyn King

Hairy canola, a tool for managing one of the worst insect pests of canola, could finally be coming into its own.

After many years and numerous challenges, the latest hairy canola lines being developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) have characteristics that could spark the interest of canola breeding companies.

AAFC’s research shows these non-genetically modified (nonGM) lines deter flea beetle feeding and might also help manage other tough-to-control canola pests. So, hairy canola could become a valuable addition to pest management toolboxes, especially if insecticide options become more limited due to regulatory changes or to development of insecticide-resistant canola pests.

“This research actually began decades ago with the work of two AAFC Agriculture Canada scientists, Bob Bodnaryk and Bob Lamb, in Winnipeg. They were looking at wild Bbrassicas, the wild relatives of canola, to find plants that were resistant or less susceptible to flea beetles. They found a fair number of Bbrassicas that had noxious chemicals that discourage insect feeding, such as the glucosinolates that we have bred out of canola. But they also found some Bbrassicas with hairs – the scientific term is trichomes – that seemed to deter flea beetles,” explains Dwayne Hegedus, the AAFC research scientist who is currently leading the hairy canola breeding work.

“Julie Soroka, who had been working with these two scientists, decided to further pursue this research when she transferred to AAFC’s Saskatoon centre in the 1990s. In some really interesting studies, she determined that for a flea beetle to begin feeding on a plant, it has to go through a series of steps involving landing, then tapping on the plant with its appendages, and then various types of probing and tasting. But if you disrupt a flea beetle at any stage in this ingrained process, it has to go back to step one. Hairs on a plant prevent the beetle from engaging in this process. So, rather than starve, the beetle eventually leaves the hairy plant.”

Margaret Gruber, a plant molecular biologist at AAFCSaskatoon, began working with Soroka to see which genes were missing in canola that prevented it from forming trichomes. “Margie forged a collaboration with a scientist at Texas A&M University who had discovered a gene called GL3 that is responsible for hair production in Arabidopsis thaliana, a European Brassica weed,” Hegedus notes. “Margie put GL3 into canola, and the resulting genetically modified lines had lots of hair [all over the plants]. However, these lines were also very small and had poor growth habits.”

To overcome that problem, Gruber made another genetic modification. “She changed the expression of a gene called TTG1 so that

the ratio of GL3 to TTG1 was closer to natural.”

The combination of these two modifications resulted in a hairy canola line that performed as well as Westar, the check canola variety, in terms of agronomics and oil quality. Plus, these hairy canola plants withstood flea beetles as effectively as Westar plants that had received an insecticide seed treatment.

“Margie then engaged in a very long exercise to try to get different breeding companies interested in this. And over the years it has been asked many times: why is hairy canola not yet in farmers’ fields?” Hegedus says.

He outlines some key factors: “First of all, the hairy canola that

Margie and Julie developed requires not one but two different transgenic events, which is quite complicated from a regulatory perspective. As well, if the ratio of GL3 and TTG1 is off a bit you can have problems with plant development, and at times this ratio is not very stable. That is not what breeders want in their breeding programs.

“Another factor is there is a patent on GL3 at Texas A&M, so breeding companies would have to deal with that. Also, there is the issue of the registration/regulatory costs for GMOs. In addition, most of our major breeding companies are also chemical companies. If they had invested in this way of naturally reducing the impact of flea beetles, that would have been in conflict with their chemical business unit.”

However, Hegedus points out that thinking on this last issue is changing, especially since neonicotinoids – the main chemical control option for flea beetles – have come under environmental review in several jurisdictions. In Canada, some bans or restrictions on neonicotinoid use are already in place, and Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) is currently reviewing neonicotinoid uses.

Given the GM-related hurdles, Gruber and Soroka decided to see if they could develop non-GM hairy canola lines. They embarked on a very ambitious program to screen more than 1,000 Brassica lines from Plant Gene Resources of Canada to look for naturally hairy plants. According to Hegedus, the researchers found a handful of hairy lines in three species: Brassica napus (canola is a type of Brassica napus that has been bred for certain crucial quality characteristics); Brassica rapa (Polish canola was developed from this species); and Brassica villosa (a wild Brassica).

He notes, “Brassica villosa is closely related to Brassica oleracea,

which is the species of most cruciferous vegetables, like cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, kale and so on. But Brassica oleracea is also very closely related to canola. In fact, if you cross Brassica oleracea with Brassica rapa, you generate Brassica napus. So they are all part of a triangle of very closely related species, and the traits in one can be transferred to another.”

Over the next few years, Gruber and Soroka conducted various studies towards developing non-GM hairy canola lines. Hegedus, who came to AAFC-Saskatoon in 1997, worked with them on these studies. Gruber and Soroka have since retired, and Hegedus has taken up the reins of this research. His current hairy canola project runs from 2018 to 2023 and is funded by AAFC and the Canola Council of Canada under the Canola Cluster research program. In this project, the researchers are continuing to develop non-GM hairy canola lines through work with the naturally hairy Brassica napus, Brassica rapa and Brassica villosa lines. Hegedus says these lines have some differences in their hair characteristics. Brassica villosa has abundant hairs that blanket all of the plant’s surfaces in a soft, velvety covering. The hairs on the B. rapa and B. napus lines are prickly, erect, less abundant, and occur only on the leaves.

Hegedus and his project team are identifying the genes that control hairiness in these different lines, and they are mapping and moving those genes into a Brassica napus background that commercial breeders could use for crossbreeding to move the trait into their elite canola lines. The team is also developing genetic markers to make it easier to track the presence of these genes in the progeny of different crosses and backcrosses.

The project also includes greenhouse and field trials to see how effectively the lines from the different crosses repel flea beetles.

“Chrystel Olivier, who is providing entomology expertise on this project, has discovered some of our early lines from some of our crosses show fairly significant deterrence to flea beetles,” Hegedus notes. “But in the lines where only the leaves have hairs, the beetles just go to the stems and begin feeding there. So we now know that we need trichomes over the entire surface of Brassica napus, like Brassica villosa has.”

As a result, the team is mapping the genes that govern trichome formation as well as the genes that regulate trichome abundance and distribution, with the goal of combining both characteristics in a single background. “We’re in a position now where I think we could begin providing some of our very early material to breeders. We have had some discussions with private sector breeders about this. They have told me that they would actually prefer the early material because then they can begin doing their own crosses,” Hegedus explains. “Even if they want to develop the markers themselves so they can do things on proprietary basis, our work on the initial crosses is very useful to them. It helps establish just how complicated hairiness might be; for instance, if it is one gene or two genes or three genes.”

By early 2020, Hegedus and his project team were feeling very enthusiastic about their progress on hairy canola. Then COVID-19 restrictions halted their work, resulting in the loss of a field season. Hegedus is hopeful to be in the greenhouse during the winter. “We were able to collect seed from some of our plants and populations, but all that has to be restarted.”

In a related project, Olivier and her research group are conducting lab and field experiments with hairy Brassica napus and Brassica villosa to assess feeding and egg-laying behaviour of striped flea beetles, diamondback moths and aster leafhoppers.

“These three insects are major canola pests, and all three of them are difficult to control,” Olivier says. “At present, there are no canola varieties that are resistant to any of these three insects. So far, no models have been developed for any of them that can predict their populations from one year to the next. With grasshoppers, you can look at the number of eggs and predict how large the population will be in the following year, but we can’t do that for these three insects.”

Plus, each of these pests has its own particular control challenges. For flea beetles, a neonicotinoid seed treatment is used to help manage the pest during the seedling stage when the plants are most vulnerable. “This seed treatment provided better results when crucifer flea beetles were the main species of concern, but we have had a shift toward striped flea beetles in many regions of the Prairies,” she notes. “Striped beetles emerge earlier and are less susceptible to the neonics. Especially where this species shift has occurred, a seed treatment may not be sufficient to control the pest and you may need to also spray the crop.” As well, the findings from the current Canadian review of neonicotinoids might impact the use of neonicotinoid seed treatments in Prairie canola crops.

“For the diamondback moth, a lot of its populations are starting to be resistant to insecticide products. Also, these insects have several generations per year, which means you need to monitor and spray your crop to control the population,” Olivier says.

“Aster leafhoppers spread the aster yellows disease. Some of the bioassays that we conducted a few years ago showed that this insect can transmit the disease to a plant in less than 10 hours. So the window to spray is extremely short.”

Olivier’s project is funded by the Canola Agronomic Research Program in partnership with Alberta Canola and SaskCanola. This project started in 2018 and goes to 2021. So far, she and her group have mainly been working on lab bioassays with flea beetles and diamondback moths.

“The bioassays involve using an environmentally controlled growth chamber. We put cages with the insects and the plants in the chamber, and we monitor the insects’ feeding behaviour, feeding damage, the number of eggs, how they fly, and how they move from one plant to the other,” she explains. “The bioassay can be a choice experiment or a no-choice experiment. A choice experiment is when we put, for example, a flea beetle in the cage with a hairy canola plant and a glabrous (non-hairy) canola plant. And we see what the flea beetles do – do they go on one plant or the other, do they prefer to feed on one and not the other, do they prefer to lay eggs on one and not the other, do they prefer to feed on some part of the plant and not the other, and so on. In a no-choice experiment, we use only one type of plant, and we see what the insects do.”

These experiments are also evaluating the effect of plant growth stage, temperature and soil moisture on insect behaviour.

“We started with the striped flea beetle bioassays because that species is the main concern for many growers. We found that the striped flea beetles tend to avoid the hairy part of the plant. So when we put a hairy canola and a glabrous canola in the cage, the beetles usually don’t want to stay on the hairy one, and they go on the glabrous one, which is very good,” Olivier says.

“When we put only hairy canola in the cage, the flea beetles don’t like the hairy parts. They don’t even particularly like the cotyledons, which is weird because the cotyledons do not have hairs. The beetles go from the cotyledons and hairy leaves to the glabrous stem. And they clip the stem, killing the stem, which is not good.”

These findings are why Hegedus’s team is now working to develop hairy canola lines that have hairs all over, not just on the leaves. Olivier notes that the Brassica villosa plants, which are hairy all over, had very little to no flea beetle feeding.

The diamondback moth bioassays are also generating valuable results. Olivier says, “We found that the female diamondback moths absolutely love laying eggs on the hairy canola; they lay a lot more eggs on the hairy canola compared to the glabrous canola. But the

good news is that the larvae have a lot of trouble walking, mining and feeding on the hairy plants. In particular, the first instar larvae, the tiniest larvae which usually mine the foliage, have a lot of trouble mining.” Those little larvae tend to die before they get much bigger.

“And when we put the bigger diamondback larvae on the hairy leaves, the larvae don’t want to have anything to do with those leaves. They prefer feeding on the glabrous leaves. So that is also good news.”

COVID-19 restrictions have limited the project’s progress this year, affecting such activities as the aster leafhopper bioassays and some field experiments.

Olivier has applied for funding for a new project to do hairy/ glabrous canola bioassays with both striped and crucifer flea beetles. “These two species are both found in Prairie canola. Some crops have a lot more striped and some have a lot more crucifer. I would really like to know what happens when you put both species in the same cage. The more tools we have to control these pests, the better. Hairy canola might be one of the tools that the growers could use,” Olivier says.

Hegedus notes, “Almost every single acre of canola grown in Canada has its seed treated with neonicotinoid insecticides because the flea beetle pressure is so high that it is virtually impossible to grow canola unless you do something to control this pest. If farmers in Western Canada lose this very important tool for flea beetle control, it would severely impact canola acreage.”

He points out that growers could lose the use of neonicotinoids depending on the results of the current review, but they might also lose the effective use of these products due to development of neonicotinoid-resistant insect populations.

“When you apply a chemical every year to control a crop disease or insect pest, you continually select for the individuals in the population that are more resistant to that chemical. So neonicotinoids are going to have a limited life, and they will have to be replaced by something else,” Hegedus says.

“I think it is far less likely that flea beetles will develop some sort of mechanism where they could begin feeding on hairy canola. Looking at natural mechanisms like this is really something we need to be doing.”

by Donna Fleury

Verticillium stripe (VS), a soil-borne disease caused by the pathogen Verticillium longisporum , is a serious disease of canola in Europe. In Canada, VS was first identified in one canola field in Manitoba in 2014.

A follow-up survey conducted by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in 2015 found that the disease was detected in six provinces in Canada, with Manitoba and the Prairies having the most fields test positive to the disease, along with a few fields in B.C., Ontario and Quebec. Researchers at the University of Alberta are leading a project to determine the potential for yield losses and the effects of critical host-pathogen interactions.

“Most of our information about this disease comes from Europe, where it is a problem in both spring and winter B. napus , causing significant yield losses.” explains Sheau-Fang Hwang, professor of applied plant pathology at the University of Alberta. “Now that VS has been confirmed in canola in Canada, there is significant potential to negatively impact the canola industry, not only by causing yield loss but also by restricting market access. The disease seems to be more prevalent in Manitoba, and we need more information and better tools for assessing severity and risk of yield loss for canola growers.”

Hwang adds, “We don’t want this soilborne disease to become like clubroot, so in collaboration with Stephen Strelkov’s lab at the university, our team is proactively looking at practical applied plant pathology research that will help growers and industry in the field. Currently, there are no effective chemical controls available and also no information on the resistance to the pathogen in recommended cultivars. Therefore, we are trying to answer some of those questions, with funding from SaskCanola and Canola Council of Canada. In addition, other researchers in Manitoba and Saskatchewan are focusing on molecular studies and genetics of the disease.”

The focus of this four-year study is on developing protocols of inoculation and a yield loss model for VS, similar to the blackleg yield loss model Hwang and her team recently developed. The objective of the VS study is to provide a way to estimate yield loss based on disease severity found in the field. “We also want to evaluate commercial cultivars to determine if there are differences in cultivars that may be susceptible, tolerant or resistant to V. longisporum , and to be able to distinguish them from Verticillium wilt caused by a related pathogen V. dahlia ,” Hwang says. “We also have two master’s student projects studying how this disease affects the plants by determining the effect of growth stage at the

time of infection and of inoculation techniques on the severity of this infection. This will help to better understand the disease and to determine how field conditions affect disease severity. This information will also help plant breeders screen for potential resistance by determining the growth stages that are most vulnerable to infection, different inoculation techniques and spore concentrations that are required for effective screening.”

The first trials were initiated in the greenhouse and in outdoor microplots in 2019 to assess the effects of inoculum density on disease severity. Canola cultivars inoculated with various densities of a virulent isolate of Verticillium were assessed for

VS symptoms, rated for disease severity and yield losses were measured. This information will be used to help develop the model to estimate yield loss resulting per unit increase of disease severity. The canola cultivars are also being evaluated for levels of resistance to VS.

“We were able to start our field trials near Edmonton in 2020, along with continuing the greenhouse trials despite COVID-19 impacts,” Hwang adds. “However, it was a very unusual year in parts of Alberta, with very wet conditions in May, June and July around Edmonton. Some fields were flooded, and the amount of rain in May and June was almost equal to normal precipitation for a whole growing season. At the end of August 2020, the field trials were still green, but we hopefully will be able to complete harvest this fall and collect results. The field and greenhouse trials will continue for another two years.”

The VS disease occurs during the growing season, with symptoms of leaf chlorosis and leaf loss. Closer to harvest, infected plants will show early ripening and plants can be stunted, symptoms that can be confused with other diseases like blackleg, Sclerotinia, grey stem or root rots. “Just before harvest, the lower stem will be white or grey in color, the stem tissue starts shredding and peeling, and small black needle pin points or microsclerotia will begin to appear,” Hwang explains. “The symptoms can easily be confused with blackleg, but the VS small black dots or microsclerotia are significantly smaller than blackleg pycnidia and tend to lump together. We calculate that the tiny black microsclerotia of VS are four or five times smaller than

Continued from page 8

“In any integrated pest management program, we don’t want to eradicate the pest – even if we wanted to do that, it is impossible. The goal is to prevent the pest’s population from reaching the economic threshold for spraying,” Cárcamo explains.

“If Trichomalus perfectus took even as little as 20 or 30 per cent of the cabbage seedpod weevils, that might be enough to prevent most canola fields from needing an insecticide application to control this weevil.

“That would obviously be quite beneficial in terms of saving money for growers. It would also be highly beneficial in terms of protecting honey bees, bumblebees and other pollinators that are part of the native biodiversity.

“Also, by not spraying insecticides, you could enhance populations of the weevil’s other natural enemies. For example, we think ground beetles, spiders and/or other predators are likely eating the cabbage seedpod weevil – we have a student doing a study on that right now. So adding Trichomalus perfectus could result in a stronger community of natural enemies and an even greater impact on the weevil’s population.”

This project is funded under the Canola Science Cluster, with AAFC and the Canola Council of Canada as the main funders.

the small black pycnidia of blackleg. Both blackleg and VS have been found on the same plants, so it takes expertise to be able to distinguish between the two diseases.”

At the swathing and harvest stage, the microsclerotia can remain in the stubble and also fall to the soil, where they can survive for many years. The microsclerotia can move on harvesting and planting equipment from field to field, through wind or water dispersal and seed contamination. Similar to other soil-borne diseases like clubroot, it is important to use good stewardship practices to reduce the inoculum load, including limiting the spread from field to field and off-farm and extending rotations to a minimum of two years between canola crops.