TOP CROP MANAGER

PREDICTING

ASTER YELLOWS OUTBREAKS

Creating a warning system for producers

PG. 6

MANAGING

SMALL AREAS OF CLUBROOT

Help prevent the spread

PG. 10

BLACKLEG STRATEGIES

Scouting is the core of management

PG. 36

Creating a warning system for producers

PG. 6

Help prevent the spread

PG. 10

Scouting is the core of management

PG. 36

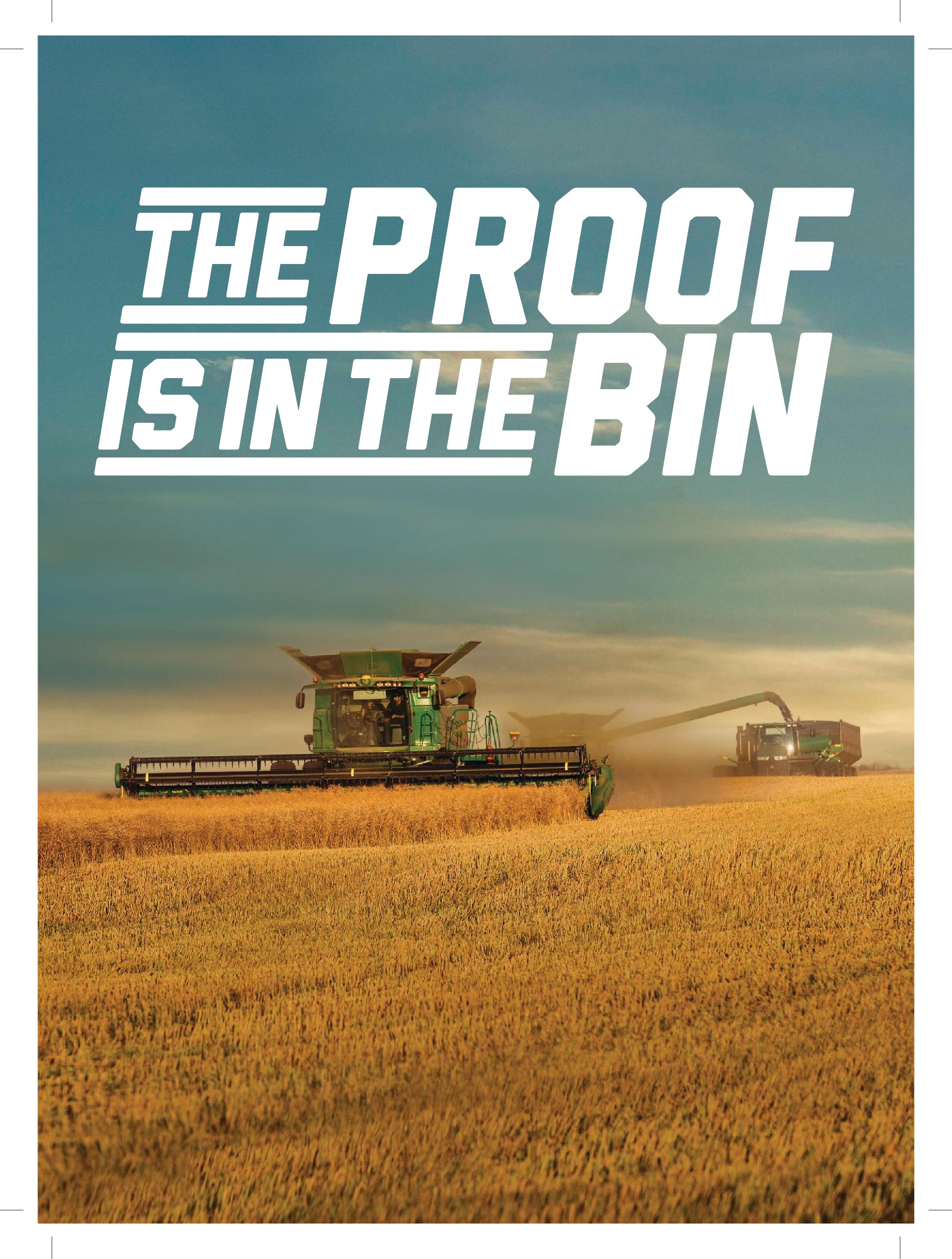

Hybrid Key Features

New InVigor® L345PC offers a significant jump in yield potential over InVigor L233P and features our patented Pod Shatter Reduction technology plus first generation clubroot resistance. This hybrid is suitable for all growing zones.

InVigor L352C offers yield potential that exceeds InVigor L252. It is suitable for all growing zones and is ideal for growers that prefer to swath.

InVigor Choice LR344PC, the first InVigor Choice hybrid, has both the LibertyLink® technology system and TruFlex™ canola with Roundup Ready® Technology. You have the option to use Liberty® herbicide or Roundup WeatherMAX® herbicide on your canola.

InVigor L233P was grown on more acres in Western Canada than any other canola hybrid in 20193. This early-maturing, high-yielding hybrid provides exceptional harvest flexibility for growers looking to straight cut or delay swath. Winner of 2017 and 2018 Canola 100 contest.

With both the patented Pod Shatter Reduction technology and second generation clubroot resistance, InVigor L234PC offers outstanding yield potential and strong standability similar to InVigor L233P. This hybrid is a great fit for growers in known clubroot-affected areas.

InVigor L255PC is a medium-height hybrid that has separated itself from others due to its very impressive standability and performance. It is well suited for growers in mid- to long growing zones.

You can expect strong standability and high yields from this mid-maturing hybrid that’s well suited to all clubroot-affected regions.

InVigor L241C won the 2016 Canola 100 contest with a yield of 81.43 bu/ac.

A consistent top performer, InVigor L252 continues to offer incredible yield performance and strong standability with mid-season maturity. InVigor L252 won the 2018 third-party Canola Performance Trials (CPTs) for the sixth straight year (average of all growing zones in small plot swath trials).

Early-maturing InVigor L230 displays outstanding yield potential with excellent standability. This hybrid is ideal for growers who prefer an early-maturing hybrid that consistently performs.

Yield % of Checks Maturity Agronomic Trait

111.9% of the checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer® 45H29) in 2017/2018 WCC/RRC1 trials

111.4% of InVigor L233P (n=28 trials, 2018)

108.6% of the checks (InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2017/2018 WCC/RRC trials

104% of InVigor L252 (n=28 trials, 2018)

104.1% of the new checks (InVigor L233P and Pioneer 45H33) in 2018 WCC/RRC trials

103.6% of InVigor L233P (n=12 trials, 2018)

One day earlier than InVigor L252

Half-day later than InVigor L252

Patented Pod Shatter Reduction

First generation clubroot resistance2

Rated R - for Blackleg

First generation clubroot resistance2

Rated R - for Blackleg

Patented Pod Shatter Reduction

Over one day earlier than InVigor L252

108.8% of checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2014/2015 WCC/RRC registration trials

104% of the checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2017 WCC/RRC registration trials

109% of checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2016 WCC/RRC registration trials

102% of checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2012/2013 WCC/RRC registration trials

Over three days earlier than the average of checks

Three days earlier than the average of checks

One-and-a-half days later than the average of checks

One day earlier than the average of checks

110% of checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2011/2012 WCC/RRC registration trials

103.9% of checks

(InVigor 5440 and Pioneer 45H29) in 2014/2015 WCC/RRC registration trials

1 Western Canadian Canola/Rapeseed Recommending Committee (WCC/RRC) trials.

One day later than the average of checks

Over three days earlier than the average of checks

First generation clubroot resistance2

Dual herbicide trait system

LibertyLink® technology sy and TruFlex™ canola with Roundup Ready® Technolo

Rated R - for Blackleg

Technology Reduction

Patented Pod Shatter Redu n

Rated R - for Blackleg

Patented Pod Shatter Reducon

Second generation clubroo e2

Rated R - for Blackleg

Patented Pod Shatter Reducon

Patented clubroot resistance

First generation clubroot re 2

Rated R - for Blackleg

First generation clubroot re i 2

Rated R - for Blackleg

Rated R - for Blackleg

Rated R - for Blackleg

2 InVigor L345PC, InVigor L352C, InVigor Choice LR344PC, InVigor L255PC and InVigor L241C all contain the same clubroot resistance pro le. InVigor L234PC c resistance pro le plus second generation clubroot resistance to additional emerging clubroot pathotypes to help combat the evolving clubroot pathotypes.

3 2019 BPI (Business Planning Information) Data. resistance ms: ystem

Patented resistance resistance contains this

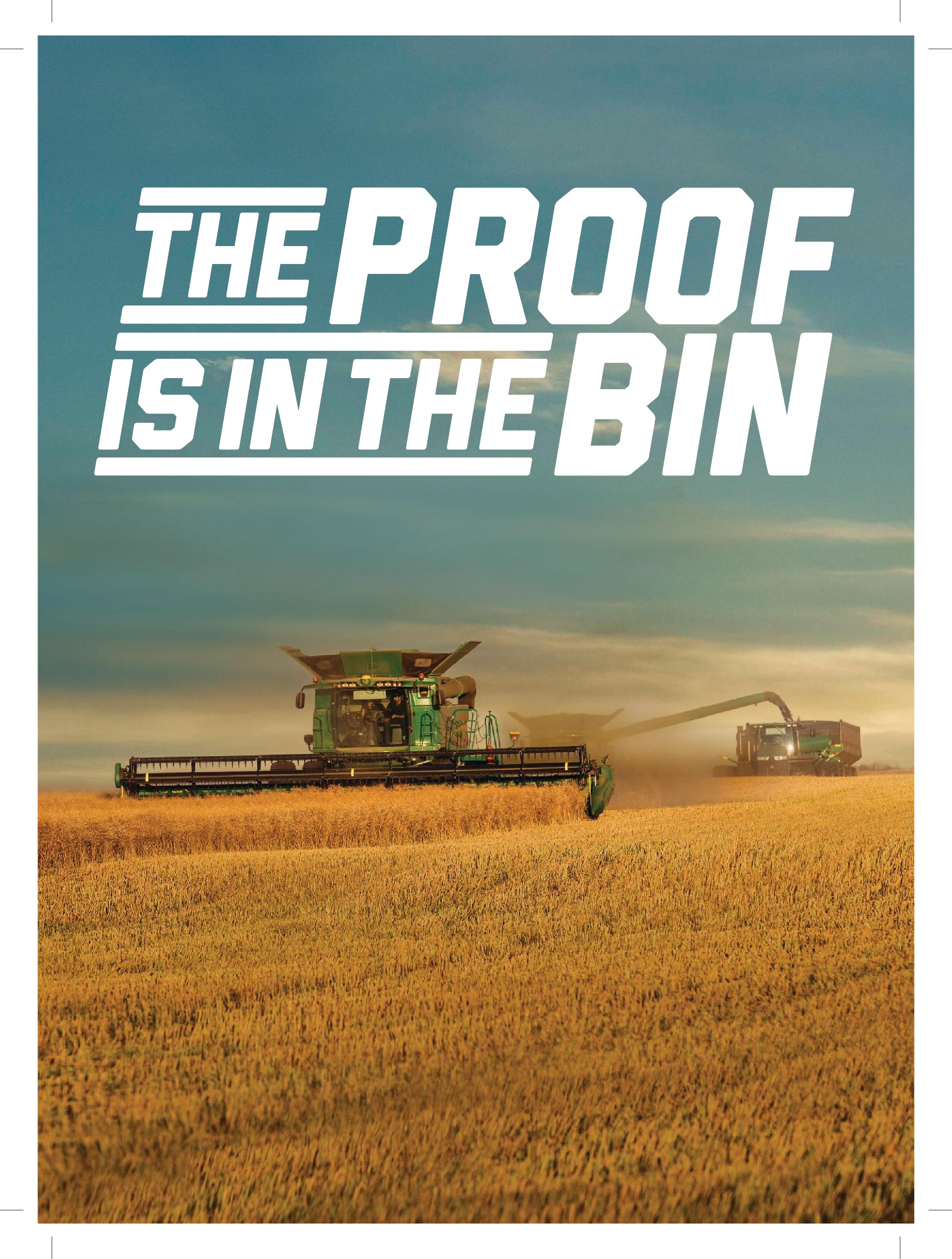

For over 23 years, InVigor hybrid canola has continuously raised the bar. Because in this business success isn’t what you do occasionally, it’s what you do consistently.

See how InVigor hybrids are performing against the competition in your area. 2019 trial results are now available. Visit InVigorResults.ca

To learn more, visit agsolutions.ca/InVigor or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

Always read and follow label directions.

AgSolutions, INVIGOR, LIBERTY, and LIBERTYLINK are registered trade-marks of BASF. © 2019 BASF Canada Inc.

John Deere’s green and yellow color scheme, the leaping deer symbol, and John Deere are trademarks of Deere & Company.

®, TM, SM Trademarks and service marks of DuPont, Pioneer or their respective owners.

© 2019 Corteva. DuPont™ and Lumiderm® are trademarks or registered trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company or affiliates.

Roundup Ready®, Roundup WeatherMAX® and TruFlex are trademarks of Bayer Group, Monsanto Canada ULC licensee. © 2019 Bayer Group. All rights reserved. All other products are trademarks of their respective companies.

PESTS AND DISEASES

6 | Predicting aster yellows outbreaks

Creating an aster yellows warning system for producers.

By Jennifer Bogdan

10 | Managing small areas of clubroot Tips to help prevent the spread. By Bruce Barker

36 | Evolving blackleg management strategies

Scouting is at the core of disease management.

By Bruce Barker

Improving sclerotinia management in canola by Donna Fleury

Better P management for canola production by Donna Fleury

STEPHANIE GORDON | EDITOR

Picture this: on one side of a field is a thriving pea crop, and on the other, a pea crop that is clearly struggling. I recently stumbled upon an image like this shared by Tyler Burns (@windypopfarm) on Twitter. The left side of the pea field was yellowish in colour, recording a yield of 38 bushels per acre (bu/ac), while the right side was green and recorded 80 bu/ac. The left side had grown peas four years prior and the right side – the higher-yielding side – had never grown peas.

Burns, who farms near Kandahar, Sask., attributes the difference in yield to aphanomyces. A relatively new root rot disease, aphanomyces has already made its impact known, paralyzing peas since it was discovered in Saskatchewan in 2012, Alberta in 2013, and more recently, Manitoba in 2016. There are very limited management options available besides rotation, which makes rotation all the more important.

There are many factors that contribute to a crop rotation decision: maintaining a level of diversity, nutrient management, herbicide carryover concerns, disease concerns, weed concerns, herbicide-resistance considerations, and so on. For some of these concerns, rotation makes all the difference. But there are other factors that come into play that defy facts, like history, legacy and attachment to a crop.

In a Financial Post column entitled, “Why it’s so hard for Canadian farmers to quit growing canola – even amid blockages from China,” author Toban Dyck shared another factor that influences crop rotation: memories. His farm hasn’t grown edible beans since a poor crop “left an indelible impression on the farm’s memory.” He doesn’t downplay the role of science, but instead creates space for “stories, anecdotes, experiences and gut feelings” to enter the rotation discussion.

This prompted me to ask Burns if he was turned off from growing peas again after a poor crop. Despite the stark yield contrast present in the fields, Burns says he will continue going peas. “We should be able to do an eight-year rotation; that should help, but we need to be more vigilant about it,” Burns shares.

While it won’t be the case for Burns, there could be many producers out there who will never add a particular crop into the rotation for reasons that go beyond science and agronomy. It’s like refusing to eat a dish that gave you food poisoning in the past: I can live without carbonara when there are more than enough other options – or crops – to work with instead.

Experience is an invaluable asset to have when choosing rotations. I hope as you plan ahead you find the research included in this issue to be helpful. Whether it’s better understanding how blackleg works on the Prairies (page 36) to managing clubroot biosecurity (page 12), these stories shouldn’t dictate how you make decisions, but add to your arsenal of resources.

Creating an aster yellows warning system for producers.

by Jennifer Bogdan

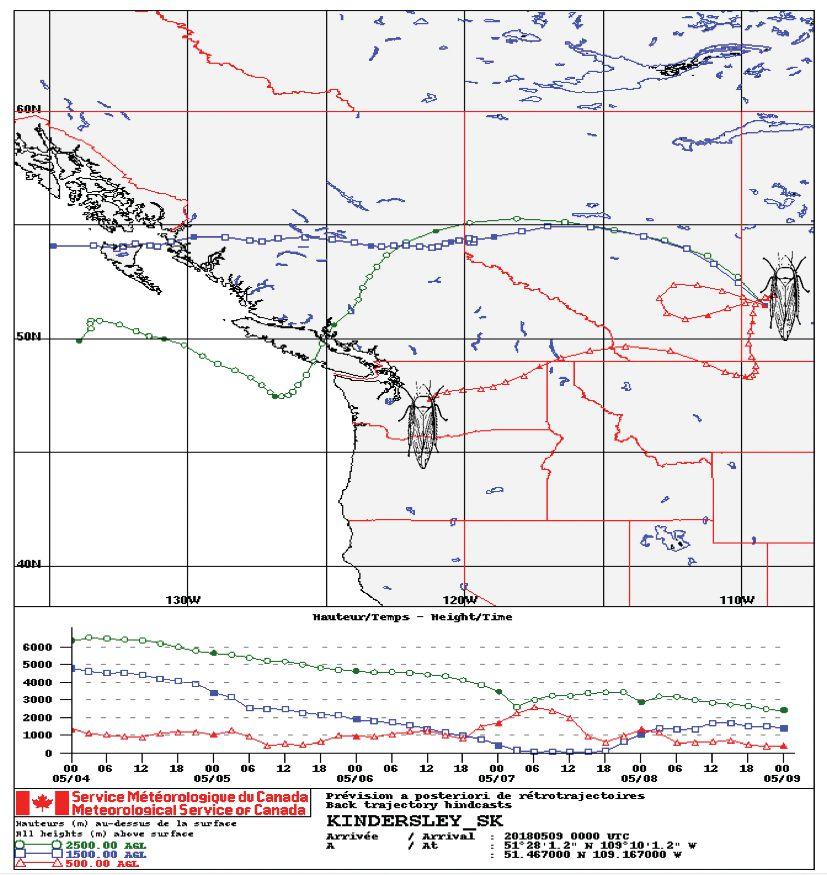

When you hear “aster yellows,” your mind may instantly flash back to 2012, when 77 per cent of the canola fields in Saskatchewan showed symptoms of the disease, and yield loss was estimated at eight per cent. But what if there was a way to get a head’s up on this disease? A team of scientists is working to develop a prediction tool by creating the very first Rapid Aster Yellows (RAY) warning system for Western Canada.

Tyler Wist, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, is leading this project and explains the importance of an early warning system for growers.

“Being able to rapidly determine the percentage of infected aster leafhoppers in the initial leafhopper migration means that growers can assess their own aster yellows risk. Also, if we can determine which growing region of the United States produces large populations of infected leafhoppers each year, we will know that

when the winds originate from those locations, we should be vigilant in our fields.”

Aster yellows is caused by a phytoplasma, a specialized bacterium vectored primarily by the aster, or six-spotted, leafhopper (Macrosteles quadrilineatus). In aster yellows-infected canola, flowers are replaced by leaf-like structures, pods are bladder-like and hollow, and any seeds that do form are misshapen and immature.

Aster yellows can also affect cereals, flax, mustard, potato, camelina, coriander, caraway, garlic, and many vegetable crops including carrots, lettuce, and celery.

The spread of aster yellows on the Prairies initially begins from infected migrant aster leafhoppers, particularly those that arrive

ABOVE: Aster yellows in canola.

on southerly winds in May. By collecting and testing these migrant leafhoppers, scientists are trying to determine where they originate from in order to better understand the wind patterns that bring them here in the first place. But pinning down the birthplace of a four-millimetre long insect blown in from a few thousand kilometres away is not an easy task.

A combination of three techniques is being used to determine migrant leafhopper origins: molecular barcoding, stable isotope analysis, and wind trajectories.

Molecular barcoding involves comparing the DNA of the migrant aster leafhoppers collected from the Prairies with aster leafhopper DNA from key leafhopper regions in the United States. However, using the traditional barcoding methods has had its difficulties.

“Barcoding showed promise in initial tests, but when we compared the typical CO1 barcoding target site and one additional site, our migrant aster leafhoppers were too similar at these two DNA regions to aster leafhopper populations all across the U.S. So, unfortunately, we can’t actually tell the locations of the migrant leafhoppers from just these two regions of DNA, as we’ve recently discovered,” Wist explains. “Using differences in the CO1 DNA barcoding region has worked to determine origins of other insects that invade Canada, like diamondback moth and pepper weevil, so it was not a dead-end road to try, except that we hit a dead end with the leafhoppers.”

Instead, a different DNA technique had to be developed for aster leafhoppers. Karolina Pusz-Bochenska, a PhD candidate at the University of Saskatchewan working with Wist on the project, in collaboration with Steve Bogdanowicz of Cornell University, created an aster leafhopper “DNA microsatelliate library” made up of hundreds of potential DNA sites to be used for comparison. Now, Pusz-Bochenska and Wist are collaborating with colleagues across the United States to get aster leafhopper samples sent to them for this comparison work.

The second technique being tested to determine leafhopper origins is stable isotope analysis. Isotopes are different forms of a single element that have a nucleus with the same number of protons but differing numbers of neutrons. “Stable” means the isotope nucleus will not decay, as opposed to an unstable (i.e.

Lower the boom on your most serious weeds and safeguard the yield potential of your LibertyLink® canola with the powerful protection of Liberty® herbicide. The Group 10 chemistry behind Liberty gives you a unique and highly-effective mode of action that tackles weeds, even if they’re resistant to glyphosate or other herbicide groups.

To learn more visit agsolutions.ca or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

Bochenska explains that using this concept for insects like dragonflies is much easier since they already have part of their life cycle in the water, as opposed to a leafhopper that is just ingesting water via plants in the environment.

The third component in determining the origin of the migrant leafhoppers is to study southern wind trajectories. By using wind data generated by Environment Canada, researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada can track winds crossing into the Prairies up to five days before they arrive. Wist’s group hopes to ground-truth these wind trajectories by sampling for leafhoppers before and after the winds blow through.

In the end, the molecular barcoding, stable isotope, and wind trajectory data will all be combined into a single model to pinpoint where the leafhoppers are coming from.

and putting it all together

Once the leafhoppers are detected on the Prairies, either through sweep sampling or on sticky cards placed in fields, they need to be tested to determine if they are carrying the aster yellows phytoplasma. Tim Dumonceaux, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, has developed an improved aster yellows diagnostic test to do just that. The test determines the percentage of leafhoppers infected, and this percentage multiplied by the number of aster leafhoppers gives an “aster yellows index,” which describes the risk of aster yellows disease transmission in that leafhopper migration. Dumonceaux’s new test produces results in one hour, instead of two to four days with the previous PCR test, and can be conducted in the field if necessary. By combining the aster yellows index with spring temperature and moisture data, the amount of aster yellows disease expected to occur will be estimated.

Once the scientists understand where the migrant leafhoppers are coming from, study the winds that brings them here, determine how infective the leafhoppers are, and know what the potential for disease development is, then the RAY warning system can be implemented. Several methods to distribute the aster yellows alerts to growers and agronomists will be explored, but Canola Watch and the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network blog are two established avenues that have been employed so far.

radioactive) isotope that will. For example, hydrogen (H) has three isotopes that occur in nature, two of which are stable (1H and 2H), while the third (3H) will break down after a number of years. PuszBochenska has been analyzing the hydrogen-2, or deuterium, isotope ratios in migrant aster leafhoppers through collaboration with Keith Hobson of Western University in Ontario.

“The hydrogen molecules from water (H2O) get put into the wing and leg cells of the leafhoppers. Because the water consumed by the leafhoppers is in the environment they developed in, we can analyze the hydrogen isotopes of these migrant leafhoppers to determine the latitude of where they came from,” she says.

While using stable isotopes to study animal migration is not entirely new – it has been used for certain insects such as monarch butterflies and dragonflies, as well as songbirds and bats – the isotope ratios for leafhoppers have not yet been correlated. Pusz-

The past two years of data collection have found low percentages of infected leafhoppers, which has correlated well with the low levels of aster yellows in canola crops reported in the annual disease surveys by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture. Wist was able to track one particular leafhopper migration to Saskatchewan that occurred in spring of 2018 originating from Washington around the time that their lettuce harvest was underway. Fortunately, not many of the arriving leafhoppers carried the aster yellows phytoplasma.

“We are still working out 2019’s patterns, but the initial aster leafhoppers that arrived were not very infected again this year and we think that fact will be reflected in low levels of aster yellows disease in canola crops at harvest time this year,” Wist says.

Wist hopes that through this project, the migration patterns of pest insects into Western Canada, such as aster leafhoppers, diamondback moths and aphids, can be better understood and predicted for the benefit of all growers.

by Bruce Barker

When first noticed from the seat of a swather, a little, insidious patch of premature ripening of canola is often the first sign of clubroot disease in a canola field. Growers in Alberta are well acquainted with the disease, which was first discovered there in 2003 and now spread widely across the province. The disease is slowing making its way east – but there’s hope. For growers in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, much can be learned from research conducted in Alberta in the last 15 years.

“For a field where clubroot is first seen in a small patch, there may be a chance to manage the disease in this small area,” says Bruce Gossen, plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon. He emphasizes that agronomists and farmers should be actively looking for clubroot, and aggressively manage it when found in small patches.

Clubroot mainly attacks Brassica species and causes stunting, delayed maturity, yield loss and plant death. The disease spreads

through the movement of resting spores, which are long-lived and number in the millions to billions in severely clubrooted galls. These resting spores can move with blowing dirt or water erosion, but primarily by transport on vehicles, equipment, industrial activity or footwear.

Gossen asked University of Alberta clubroot researcher Victor Manolii for the top 10 locations that clubroot is most likely to be found first. The most obvious was in spreading patches of stunted and dying plants.

The next most obvious place is at the main entrance of a field, where dirt from other fields often falls off equipment or vehicles. Stephen Strelkov, plant pathologist at the University of Alberta, looked at the pattern of clubroot occurrence in clubroot-infested fields in Alberta. At field entrances, clubroot was found 90 per cent of the time. Moving 150 metres out into the field, the left edge had clubroot 39 per cent of the time, the right edge 48 per

ABOVE: Growing resistant canola (right) hybrids will help manage clubroot.

Take advantage of our one-year free trial offer, receive your FieldView Drive™, and start mapping every pass you make in your fields. Uncover valuable insights year-round with tools that help you analyze crop performance at the field level.

cent and the middle around 32 per cent.

“A farmer explained to me that when he moves equipment onto a field, he turns right because the right side of the tractor is where the hydraulics are and he can watch the equipment as it comes down,” Gossen says. “That might explain why clubroot occurrence is higher on the right-hand side of the field entrance.”

The next four locations are other entrances like a yard, highway, bridge, and other secondary field access points. Number seven is temporary streams or drainage where spores can be transported by water. Around field grain bins is another location, along with power lines, pipelines and oil sites. Low areas of the field such as sloughs, where water ponds, can also be a catchment area for spores.

“In Manitoba, clubroot is showing up first in low areas of the field, rather than at field entrances, which is different than in Alberta. The spread of the disease may be happening differently in Manitoba, but I suspect that, over time, field entrances will be an important source of clubroot infestations,” Gossen says.

When looking for clubroot in these locations, Gossen says agronomists and growers need to be proactive and try to confirm the presence of the disease at early stages. Pull up or dig out canola roots and search for signs of galls later in the growing season. Identifying tiny galls on canola roots provides an early warning signal and time to implement some localized management practices. Once gall development becomes larger with higher numbers of spores, preventing the spread of spores is more difficult

Random surveys conducted by government agencies help track the disease, but of 1,500 fields surveyed in Saskatchewan in 2018, only two of 37 confirmed cases of clubroot were identified randomly - the rest were confirmed from farmers and agronomists sending in samples for testing.

While clubroot zoospores require moisture in the soil to swim to a canola root, dry conditions don’t always mean clubroot won’t infect the plant. Gossen says in 2009, rain didn’t fall until July in Alberta, and researchers thought there would be less clubroot. That wasn’t the case. Three weeks after the first rain, infection was identified and at the end of the season, the researchers saw the biggest galls they had ever seen.

Tight canola rotations are one of the reasons clubroot is

spreading. A two to three year break can reduce spore levels in soil by 90 to 99 per cent. However, under heavy spore loads, the remaining spores can still cause high enough disease levels to create 100 per cent yield loss.

Resistant varieties also help minimize the damage, but in Alberta different pathotypes capable of overwhelming the resistant genes were present in many fields within four years of the introduction of the first resistant variety.

Sanitation has long been promoted when moving equipment and vehicles from field to field. When leaving a field, scrape off lumps and caked soil to help limit the spread of the spores from field to field. High-pressure rinses and sanitation with bleach to kill the spores are also promoted, but are time-consuming.

“Outside of the oil patch, I don’t think anyone is spraying caustic bleach on their equipment. Most just knock off the dirt,” Gossen says. “But if I was in Manitoba and brought in a used combine from Alberta, I would clean and sanitize that combine inside and out.”

Clubroot prefers soil pH below 7.2, and researchers have found that liming soils with hydrated lime to raise pH can help reduce clubroot infection. But at six to seven tonnes per acre at $1,000 per tonne, the cost is prohibitive on a field scale basis. Gossen says that liming may be a good tool for patch management when the disease is first getting established in a field. However, with good moisture and high soil temperatures, clubroot can still develop, so liming is not the complete answer.

Gossen also conducted research into the effect of soil type, organic matter, and compaction on clubroot severity. He found that soil type or organic matter had very little affect on severity, but clubroot was more severe on compacted soils. Field entrances are generally more compacted than the rest of the field, so minimizing compaction may help to minimize the severity of clubroot in those areas.

When clubroot is first identified in a small patch, Gossen recommends farmers mark out at least twice the infected area in every direction and exclude traffic. If possible, canola roots with clubroot galls should be removed from the field and burned to destroy the spores.

The next step Gossen recommends is to incorporate lime to bring pH up to 7.5, and then seed a sod-forming grass to provide a break from canola and to prevent the movement of spores. Once the sod is established, traffic over the grass can resume.

The sod patches can be monitored over the years by soil sampling to monitor spore concentrations. When spore levels fall to a low level, the sod could be broken up and re-cropping with a clubroot-resistant variety resumed on a three-year (or longer) rotation.

Gossen suggests a permanent grass cover be established at the field entrance, because this is where equipment is dropped and clubroot often gets a foothold. He says the Canola Council of Canada builds on that recommendation by recommending a different, grassed exit for infested fields, where equipment can be cleaned off before moving to the next field.

“No single approach will work on its own,” Gossen says. “That’s the take-home message. You just can’t rely on resistant varieties.”

We know that choosing the right product is only part of your success. Richardson Pioneer offers expert agronomic advice and fully integrated service to help you profitably increase your yields.

Book your 2020 seed today.

WITH YOU EVERY STEP OF THE WAY

by Bruce Barker

Don’t flip the page after reading “cultural weed management.” It’s an important part of weed control, even when using herbicides.

“The idea behind cultural weed management is increasing crop competitiveness helps compete with weeds for resources like nutrients, water and sunlight. With fewer resources, weeds will have reduced fitness and have fewer viable seeds to return to the seedbank,” says Charles Geddes, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alta.

Cultural weed management is one of four cornerstones of Integrated Weed Management; the other three consisting of physical or mechanical weed control, bio-control with pathogens, insects or even livestock, and herbicide control. Shifting competitiveness in favour of the crop instead of weeds also helps battle the selection for herbicide resistance. Greater crop competition reduces weed competition, improves herbicide weed control, and reduces weed seed production of weeds that escape herbicide control. “Many cultural tools are already used by growers but they don’t necessarily categorize them as cultural weed

management,” Geddes says.

Establishing a healthy plant stand goes a long way towards increasing the competitiveness of a crop. Bob Blackshaw, an AAFC researcher in Lethbridge, Alta., ranked crops according to their competitive ability: Rye > oat > barley > wheat > canola > field pea > soybean > flax > lentil. The rankings may be different in different areas of the Prairies, and hybrid canola is more competitive than open pollinated varieties. Some varieties within a crop are also more competitive than others.

Seed size can matter as well. Research by Chris Willenborg at the University of Saskatchewan found that large oat seeds tend to produce more competitive, higher-yielding plants than small seeds. In oat plots grown with larger seed, wild oats were smaller and produced fewer panicles compared to oat plots grown with smaller seed.

Seeding rate and row spacing have large impacts on crop com-

ABOVE: Research at AAFC Lacombe by John O’Donovan found that increasing barley and canola seeding rates resulted in improved herbicide effectiveness.

petitiveness. Multiple studies have found that a higher seeding rate at narrower row spacing improves crop competitiveness and herbicide performance. John O’Donovan at AAFC Lacombe found increasing barley and canola seeding rates resulted in improved herbicide effectiveness. In another study, he also found barley yields were higher in the presence of wild oat when higher barley seeding rates were used, and high seeding rates could reduce the need for wild oat control with herbicides.

In another AAFC study led by Bill May, 18 field experiments at six locations in western Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan, oats were seeded at various rates, with target plant densities ranging from 14 to 42 plants per square foot. When no wild oat was present, yields at all seeding rates were around 120 bushels per acre (bu/ac). With wild oat pressure, the 14 plants seeding rate yielded 84 bu/ac, rising to 97 bu/ac at 21 plants, with yield topping out at 100 bushels bu/ac for the remaining higher seeding rates.

Narrower spacing has also been proven to help the crop compete with weeds. In cereals, very narrow row spacing was found to reduce overall weed competitiveness. Row spacing as low as four inches is not practical with today’s no-till equipment, and row spacing of nine to 12 inches is generally used by most farmers. As a result, seeding rate may be more important than row spacing.

Pulling some of these stand establishment practices together, Geddes completed the second year of a multi-year trial in 2018 investigating the interaction of row spacing, seeding density and crop rotation on glyphosate-resistant kochia control. He is look-

ing at a crop rotation of spring wheat-Clearfield lentil-spring wheat-Liberty Link canola and is utilizing typical herbicides for kochia control.

“We want to see if there are benefits in combining multiple tools over a longer period of time. We hypothesize that there should be lower weed seed production with narrower row spacing and higher seeding rates,” Geddes says. “We also hypothesize that the benefits of using these cultural tools consistently will amplify over time.”

Seeding date is also viewed as a cultural management practice. Generally, earlier seeding allows the crop to get established and better compete with weeds. But delayed seeding can allow for management of a greater number of emerged weeds prior to planting, sometimes resulting in lower weed emergence after the crop is planted.

Fertilizer placement to encourage crop growth and competitiveness is another cultural weed management tool. Several studies in Saskatchewan and Alberta have found that, generally, banding nitrogen (N) fertilizer below the soil surface helps crop seedlings get to the nutrients more quickly, increasing crop competitiveness. Additionally, banding N close to the time of seeding also favours crop competitiveness compared to fall banding. In an Alberta study on spring wheat by Blackshaw, applying N fertilizer in spring produced higher wheat yields with lower total weed densities and biomass.

Intercropping research is generating great interest, and

Continued on page 31

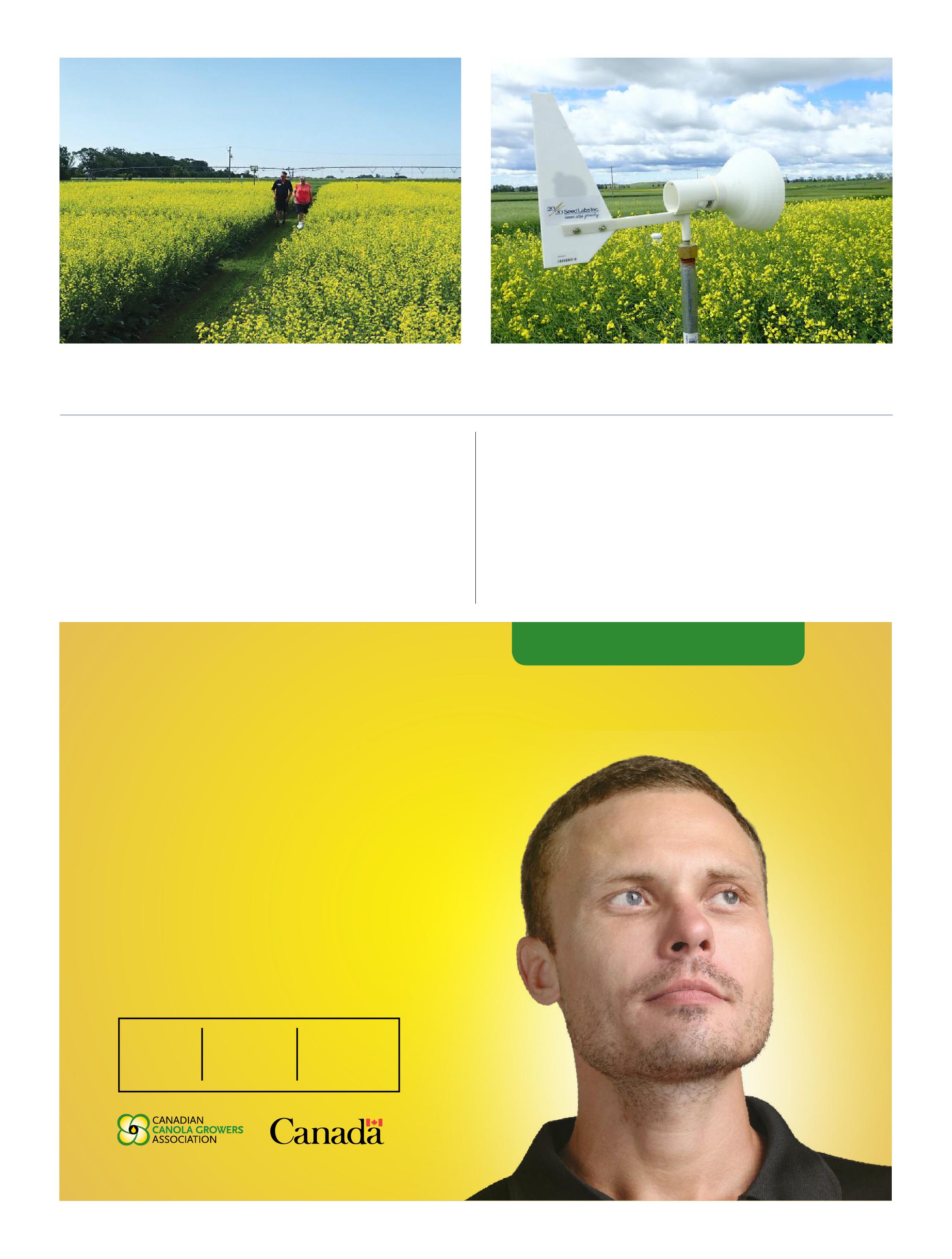

by Julienne Isaacs

For the second year in a row, Manitoba Canola Growers Association’s (MCGA) Pest Surveillance Initiative (PSI) lab is offering Manitoba producers free blackleg race, clubroot and glyphosate-resistant (GR) kochia testing on one field this fall and winter.

The program is also open to agronomists submitting samples on behalf of growers. Combined, the tests ring in at roughly $450 for non-members.

“We are definitely still in the awareness-building phase of offering this service. We had a few dozen growers take advantage of the service last year, but that number is growing,” says Delaney Ross Burtnack, executive director of Manitoba Canola Growers.

PSI is the MCGA-led molecular detection lab that identifies, quantifies and tracks risks to successful crop production – including soilborne pathogens like clubroot, and airborne pathogens like blackleg, sclerotinia, cereal rusts and Fusarium, as well as weed threats such as GR kochia.

Last year, in collaboration with Manitoba Agriculture, PSI surveyed townships across the province and collected more than 700

soil and plant samples to aid in provincial clubroot, blackleg and GR kochia monitoring. This year, PSI hopes to increase that number.

In the case of blackleg and clubroot, PSI is the newest link in the province-wide effort to understand, monitor and prevent diseases that represent a serious economic threat to Manitoba producers.

“It all started when the first detection of clubroot happened in Manitoba in 2013. Although the universities analyze samples and Manitoba Agriculture’s Crop Diagnostic Centre does gross plant analysis and traditional culturing, we had no in-province capacity to determine how big of a problem clubroot was,” says Lee Anne Murphy, CEO of PSI.

The Canola Growers immediately instigated an effort to set up a lab, which, in collaboration with Manitoba Agriculture and other partners, opened just a year later in the fall of 2014.

“There’s no other grower-funded lab like it in the Prairies,” Burtnack says.

ABOVE: With Genome360, PSI is developing a “mobile lab” that can be deployed to rapidly identify disease and weed species in the field.

Enhance cleavers control by tank mixing new Facet L with Liberty herbicide.

For years, you’ve trusted Liberty® herbicide to manage tough weeds in your InVigor® hybrid canola, including glyphosateresistant biotypes. But when you’re also facing increasing pressure from cleavers, now you can call for backup. That’s where new Facet® L herbicide comes in. When tank mixed with Liberty at 160 ac/case, it enhances cleavers control to protect the quality and yield potential of your InVigor canola. Visit agsolutions.ca/canola/weedmanagement to learn more.

Murphy says the lab started with a focus on understanding and benchmarking clubroot incidence in the province, but its efforts quickly expanded.

“Ideally you grow canola one in four years, but what happens in the intervening years can impact your crop. We asked, ‘How can we leverage existing DNA capacity to keep on top of emerging issues and identify them through surveillance?’” she says. “That led us to look at other pathogens.”

For example, PSI’s samples helped validate AAFC-developed markers to identify races of blackleg, Murphy says. Now, PSI offers race identification as a service to producers.

Blackleg is caused by a complex of two species of fungus: Leptosphaeria maculans and Leptosphaeria biglobosa. The former is a virulent species responsible for most blackleg damage. Lab testing helps determine which of these species is present in the field, and the frequency of blackleg races across the samples. Race identification is a crucial step for producers hoping to mitigate the impacts of blackleg when a given variety’s resistance starts to break down in the field, because major genes within canola varieties must match avirulence genes in the pathogen in order to work.

S oil testing is used to detect the clubroot pathogen, Plasmodiophora brassicae, in canola fields, but in order to reduce the chance of false negatives, it’s important to sample correctly. Manitoba Canola Growers Association’s (MCGA) Pest Surveillance Initiative (PSI) lab offers tips for producers to take a representative soil sample.

Collect samples in the fall while clubroot galls are degrading or in the spring after a canola crop is seeded.

Focus sampling on high risk areas of the field (field entrances, low spots, low

When resistance breaks down, producers need to get their fields tested to establish the blackleg races that are present so they can choose varieties with resistance to match.

Testing happens in two parts: first, the lab confirms whether or not the sample is blackleg. If blackleg is confirmed, PSI identifies the races present in the field where the sample was taken, including genotype and estimated phenotype - which the producer uses to make variety choices. If the sample isn’t blackleg, half of the test fee is refunded to the producer.

“Every producer who submits a sample gets a report on what’s in that sample. Our first focus is on getting that information to the grower,” Murphy says. “We don’t just provide the results, but go to the next step and say, ‘Based on the race structure, these are the genes you should be looking for on the seed bag.’”

The lab also archives its samples, Murphy says. Currently, PSI hosts more than 1,500 soil samples; because spore DNA is relatively stable in these samples, when PSI receives new clubroot race assays they can go back and cross-reference the new assays against archived samples.

pH areas, natural water runs and other high-traffic areas).

Sampling should be completed separately from fertility testing, as they follow

different protocols and soil depths.

Follow biosecurity protocols to minimize contamination (e.g. sanitize tools and equipment between samples within a field, or from field-to-field).

Ensure soil samples are allowed to dry if they are collected under damp conditions. Avoid cross-contamination between samples while drying.

Further, more detailed sampling guidelines for producers, including blackleg sampling protocols, can be found on the PSI website atwww.mbpestlab.ca/fieldtesting/.

PSI doesn’t operate alone. It pools its data with Manitoba Agriculture’s provincial disease survey data to “grow out the database” for the broader surveillance effort. It’s also part of a project called Genome360, a collaboration between Genome Prairie and partners that aims to offer access to state-of-the-art equipment to Manitoba’s genomics community.

The device is placed between the tractor power unit and the hitch of the air drill, and consists of a load cell, data logger and battery.

With Genome360, PSI is developing a “mobile lab” that can be deployed to rapidly identify disease and weed species in the field. PSI is currently testing a Bento Lab unit, a mobile mini DNA analysis tool that might be a good fit for the lab.

“Especially with fresh material, you want a high-quality sample. We want the time between when you pick the leaf to when you extract the DNA to be as short as possible,” Murphy says.

Murphy says that once the technology develops the lab could be deployed to help with clubroot and blackleg identification in the field, but the industry isn’t there yet. “Right now, we see the mo -

bile lab working more on herbicide resistant kochia and, eventually, GR resistant waterhemp, than on disease identification, because at this point it’s easier to extract DNA from actively growing plants,” Murphy says.

Burnack sits on the Canola Council of Canada’s Blackleg and Clubroot Steering Groups. She says the industry is working together at every step to understand how to tackle these diseases across the Prairies.

But PSI’s efforts are focused on Manitoba producers first and foremost. “We want to make sure growers have opportunities to get something tangible from the checkoff dollars they put into the Canola Growers,” she says.

Our new canola hybrids bring TruFlex™ performance in a Proven package, giving you a choice in Roundup Read y ® technology. Choose PV 780 TC for clubroot resistance and consistently high yields. Go with PV 760 TM if you need the option to straight cut your canola. Either way, you’re getting disease management, wider spray windows and application rate flexibility, plus the ability to grow in all maturity zones. Find the perfect fit for your farm with a Proven® Seed TruFlex™ canola hybrid. Only available at Nutrien Ag Solutions™. Learn more at ProvenSeed.c a

Canola seed purchasing decisions are typically made before the end of the year to ensure the availability of preferred hybrids and varieties. This means growers need to think about what type of early season pests they expect to be a problem, and whether foundation seed treatments will be adequate or enhanced options would be recommended.

For canola growers, flea beetles and cutworms are the two most economically damaging early season pests, both which can cause significant crop damage if not controlled. Commercial canola seed comes pre-treated with insecticide for controlling flea beetles, in combination with fungicides for controlling seedborne and seedling diseases. Additional insec-

ticide components for cutworm management and enhanced flea beetle control can be added if desired. Proper seed treatment sets up the crop for good stand establishment, uniform crop development and optimizing yield potential.

“Flea beetles are a chronic and potentially serious pest issue for canola growers, and canola seed is sold treated with an insecticide for early flea beetle control,” says John Gavloski, entomologist with Manitoba Agriculture. “Last year, the flea beetle situation was quite high in many areas, so along with seed treatments, some additional foliar insecticide applications and reseeding were required. One of the big challenges with flea beetles is getting the crop through the susceptible stages before the seed treatment wears

ABOVE: Redbacked cutworms overwinter in the egg stage, so damage may not show up until later in the spring.

out. If spring growing conditions are good and provide quick germination and quick early growth, then a seed treatment may be all that is needed. But if conditions are not as good and populations are very high, an additional foliar insecticide application may be required. Soil moisture is also an important factor, which can vary from year to year. In dry years, growers may want to seed deeper to moisture, which may delay germination and early growth as well.”

There are two main flea beetle species that can cause serious damage in canola crops in Western Canada: crucifer (Phyl-

lotreta cruciferae) and striped (P. striolata ). The crucifer flea beetle is abundant across all canola-growing regions, while the striped flea beetle has been expanding its range into the Black and Dark Brown soils zones. Adults overwinter and emerge early in the spring and cause damage to canola by feeding on stems, cotyledons, and young true leaves. Adult crucifer flea beetles are small, black, elliptical or oval-shaped, and less than 2.5 millimetres (mm) long. The striped flea beetles are two to three mm long, oval-shaped with two cream-coloured or yellow wavy stripes on their backs.

“Although the dominant species [in many areas of the Prairies] has typically been the crucifer flea beetle, the striped flea beetle, which had a traditional range mostly in northern areas, has been moving south throughout the Prairies,” explains Gregory Sekulic, agronomy specialist with the Canola Council of Canada. “Now it is difficult to find fields without striped flea beetles. There are some biological differences in the two species and they are managed somewhat differently. The striped flea beetles tend to emerge a little earlier in the spring and eat a little more before they are controlled by some older-generation neonicotinoid products. Although there has been lots of research dedicated to flea beetles, it remains extremely difficult to predict whether or not flea beetle populations will exceed economic thresholds or what regions could be at risk the following year. Therefore, most canola seed comes treated with a base treatment for flea beetles, and some newer, advanced products are capable of stronger management of striped flea beetles.”

Cutworms are another serious canola pest and some areas of Manitoba, for example, have seen high populations in recent years, including 2019. Newly germinated seedlings and small plants are most at risk, as cutworms can cut off and kill the entire plant. Cutworms tend to be most active later into the evening, when conditions are cooler and relative humidity is higher. One of the challenges in scouting cutworms is different species have different feeding habits, including aboveground, soil surface and belowground feeders. The prominent species

It’s difficult to predict the risk and impact flea beetles may have on a crop, so most canola seed comes treated with a base treatment, and new products are capable of stronger management.

that attack crops on the Canadian Prairies include army cutworm, pale western cutworm and redbacked cutworm.

“Thresholds for cutworms tend to be a little more difficult to trigger, as typically cutworms tend to be patchy and do severe damage in some areas, but not others,” Sekulic explains. “Cutworms are

a very difficult pest both to scout for and control, and substantial portions of crop can be lost before damage is widespread in the spring. New-generation seed treatments or top-ups do a good job of managing them before a foliar treatment would be required.”

Cutworm moths like to lay eggs in bare

areas of a field that have been dried out or drowned out, Sekulic continues. “In those higher-risk fields, growers may want to consider a top-up seed treatment for cutworm management the following year, along with addressing striped flea beetle populations.”

Gavloski adds most canola seed comes with a base seed treatment of the neonicotinoid group, which is just registered for flea beetles. “Adding an additional insecticide component, such as those in Group 28, to the base seed treatment is needed for good activity on cutworms.”

There is a tradeoff, he notes: “An enhanced package that addresses both flea beetles and cutworms will cost more than a base treatment for flea beetles only. But, if the seed treatment saves a foliar spray down the road, or there is lots of cutworm damage, then the enhanced care will pay for itself.”

Cutworms can be challenging, Gavloski adds. If, for example, the dominant species is redbacked cutworm, which overwinters in the egg stage, the hatch may have just begun at seeding and damage may not show up until later in May, impacting yield and profitability if not controlled. “The difficulty is the decision will have to be made the previous fall regarding which commercial seed package to purchase. So farmers will have to make decisions for controlling cutworms based on what they saw last year.”

For 2020, canola growers will have a new enhanced commercial seed treatment available for protecting against both striped and crucifer flea beetles, as well as cutworms. “Feeding by flea beetles and cutworms can result in uneven emergence, thin plant stands, delayed crop development, and uneven maturity, leading to lower yield potential. Feeding sites can also act as entry points for disease-causing pathogens, further threatening canola yields,” says Karen Ullman, seedcare product lead for Syngenta Canada. “We have tried to make seed treatments simpler for growers in 2020 by offering two key options, either a base treatment like Helix Vibrance, or the base plus an enhanced treatment in Fortenza Advanced.”

Fortenza Advanced, which combines two seed-applied insecticides in one product, sulfoxaflor (Group 4C) and cyantraniliprole (Group 28), will always be paired with a base seed treatment,

such as Helix Vibrance. Ullman says the product offers protection from both striped and crucifer flea beetles, as well as cutworms, in addition to four fungicides for control of seedborne Alternaria , blackleg, and seedling disease complex caused by Pythium, Fusarium , and Rhizoctonia spp

“Fortenza Advanced builds upon the foundation of a base treatment to protect canola seed from aggressive pests, in particular striped flea beetles that are continuing to move through the Western Prairies, and cutworms,” Ullman says. “Fortenza Advanced also extends the timeline of the seed treatment, from 28 days with a base seed treatment to an assurance policy of 35 days after planting with Fortenza Advanced. The only time growers may have to go in with an additional foliar application is if there is a really high pressure from pests.”

“Flea beetles and cutworms were a problem for many growers in our area in Alberta in 2019, so selecting enhanced seed treatment packages when

purchasing canola seed this fall should be considered,” adds Debbie Michielsen, owner of Meadowland Ag Chem Ltd. in Castor, Alta. “Some growers didn’t realize they had cutworms, or thought the problem was gophers or drought patches before realizing the damage. Protecting that small seed going into the ground, improving seedling vigour and making sure it is protected against flea beetles and cutworms is important. We generally sell most of our canola seed by the end of November, so growers have to decide early if they want the base or advanced seed treatment packages.”

Michielsen adds growers sometimes forget how frustrated they were with early season pest infestations, and reminds them it is important to remember that canola seed is not cheap and seed treatment is like insurance. “Sometimes they made good decisions but never went back to scout fields and verify the results, so they don’t realize the benefits they gained.”

Michielsen notes seed treatments provide early protection specifically for the target, meaning a foliar spray may not be necessary. “Waiting for foliar applications means you likely already have damage,” she says, noting the time and financial costs of another field operation, rather than addressing the problem at the seed treatment stage.

“Whether growers are working with an independent agronomist or a retailer, check in with [your advisor] to find out what they are seeing in fields in your area. They can also help guide which seed treatments might be recommended depending on pest populations, moisture and other conditions,” Ullman adds.

“Place canola seed orders early, particularly for the enhanced products, to make sure of availability. By adding enhanced seed treatment you are protecting your seed investment early and contributing to your success. This gives the canola crop the greatest chance to have good stand establishment, uniform crop and really giving yourself the best yield potential for the coming year.”

A long-term approach is required to address unique needs.

by Bruce Barker

Flax isn’t just another crop. It has unique phosphorus (P) nutritional needs that include a greater dependence on soil P and mycorrhizae fungi. As a result, P management in flax requires a long-term approach.

“ Flax requires some extra attention when it comes to phosphorus management,” says Ramona Mohr, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Brandon, Man. “Phosphorus plays some key roles in plant growth including early root and shoot growth, earlier maturity, and improved efficiency of other nutrients such as nitrogen.”

Flax requires moderate amounts of P in an uptake range of 18 to 22 pounds P2O5 per acre, and removal of 14 to 17 pounds P2O5 per acre in the seed. Flax removes 0.65 pounds of P2O5 per bushel, which is similar to that of pea (0.69 lbs. P2O5), slightly more than

wheat (0.59 lbs. P2O5) but less than soybean (0.84 lbs. P2O5) or canola (1.04 lbs. P2O5).

A key difference for flax compared to other crops is that P uptake in flax is greater from soil P than fertilizer P. Research showed that while rapeseed derived similar amounts of P from soil and fertilizer P, flax derived up to three times more P from the soil than from fertilizer P.

“Flax relies more on the bulk soil for P uptake than the fertilizer band,” Mohr says. This is reflected by research that shows flax roots do not proliferate into a high P fertilizer band reaction zone. Again, this is different from other crops, like rapeseed, where root proliferation in the fertilizer band is much higher than in the rest of the soil.

F lax is also sensitive to seed-placed P fertilizer. Guidelines have been established in Manitoba not to exceed 20 lbs. P2O5 per acre as seed-placed monoammonium phosphate based on disc or knife openers with a one inch spread and six to seven-inch row spacing and good to excellent soil moisture. Saskatchewan’s guidelines are based on knife openers with a one-inch spread, nine-inch row spacing and good to excellent moisture conditions, and the actual amount of P2O5 should not exceed 15 pounds per acre.

As alternatives to seed placement of P, broadcast and side-band

placements were investigated by several research projects in the 1980s by AAFC researchers Lorraine Bailey and J. Sadler. In separate studies, they found that P uptake from side-band placement was superior to broadcast or seed-placed.

“Based on the research, banding fertilizer P near the seed-row is a good management option,” Mohr says. “Banding avoids seedling damage from seed-placed P, but is still near the developing roots early in the growing season.”

Arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi (AMF) are naturally occurring soil fungi that can colonize on the roots of many agricultural crops including flax. By producing hyphae, mycorrhizae can extend the active root surface beyond the area explored by the crop root alone. For flax, mycorrhizae helps increase the availability of an immobile nutrient such as P, and can also increase the availability of soil water to the flax root.

A 2016 study by Minghu Li at the University of Saskatchewan found high levels of mycorrhizae fungi colonizing flax roots in most of the 18 commercial flax fields surveyed. The fungi were also affected by factors including field management and soil characteristics.

SOURCE: KALRA AND SOPER, 1968.

I n Li’s study, no-till commercial flax fields had a greater abundance and species richness in AMF communities than conventional tilled fields. Tillage can disturb the fungal networks, reduce spore density, and alter the AMF species left from the previous crop. In another Manitoba trial from the early 2000s by AAFC researcher Marcia Monreal, tillage had no effect on AMF colonization of flax, but early colonization of flax was higher after wheat than canola.

An important implication of crop rotation on mycorrhizae colonization on flax is that canola is not a host for mycorrhizae fungi. The importance of mycorrhizae can be seen in research in Manitoba by AAFC researcher Cynthia Grant in the early 2000s. Flax following wheat had increased early-season P uptake at all

six site-years compare to canola stubble, and higher flax yield occurred on wheat stubble than canola stubble. Net revenue was also consistently higher for flax after wheat than canola.

More recent research by Chris Holzapfel at the Indian Head Applied Research Foundation found modest yield responses to moderate rates of side-banded P. The research looked at four nitrogen (N) rates and four P fertilizer rates over three years at eight locations in Western Canada starting in 2016. Phosphorus rate did not have a noticeable effect on flax maturity. Flax yields were increased with both N and P fertilizer.

Averaged across sites, Holzapfel found that yields continued to increase right up to the highest rate of 60 kg P2O5 /ha, but only with an average yield increase of seven per cent at the 60 kg P2O5 /ha rate. Despite the linear response to P, the researchers felt that more modest rates of 20 to 40 kg P2O5 /ha would likely be enough

to prevent significant yield loss but still maintain soil fertility.

Mohr says that based on the research conducted over the years, a number of conclusions can help guide P management in flax. Given that early season P availability is critical to optimize yield, management practices should aim to supply adequate P early in the growing season. This can be accomplished in a number of ways.

Band fertilizer P close to the seedrow to ensure early access to the roots, and to minimize P tie-up in the soil. Flax is also more reliant on soil P than some other crops, so soils with a higher soil test P level are better suited to flax production. And since flax benefits from mycorrhizal fungi, flax should be grown after crops that support mycorrhizal crops – not canola – and under reduced tillage systems.

Visit www.topcropmanager.com for more on soil fertility and flax production.

At Prove n® Seed, we have a different perspective on corn. Every hybrid is designed with a purpose, whether you need early maturity, fast dry down or defensive trait protection. Each one is a high-yielding work of art, and there’s a hybrid that’s perfect for your field conditions. Proven Seed corn is only available at your local Nutrien Ag Solution s ™ retail. Learn more at ProvenSeed.c a

Better risk management tools and fungicide treatments are coming to improve disease assessment, control and economics.

by Donna Fleury

One of the biggest challenges of a disease like sclerotinia in canola is a grower needs to make the decision to spray fungicides well before they see any symptoms in the field. Sclerotinia stem rot is known as a major disease of canola that can cause significant crop yield and revenue losses. Early infections also cause more yield loss than later infections, and the economic benefit of a fungicide application is generally higher with early applications. With new advancements in molecular biology and DNA diagnostic techniques today, combined with new disease sampling tools and quick lab tests, researchers hope to be able to develop diagnostic and decision tools to improve the ability to assess risk and control sclerotinia disease with fungicides.

“Sclerotinia stem rot research and management has been a long-time priority and passion of mine since my start as a summer student in the early 1980s,” says Kelly Turkington, plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta., who also completed his MSc and PhD degrees at the University of Saskatchewan based on sclerotinia research.

“Over the years there has been quite a bit of research, building on the foundation from those early years and work of previous colleagues. Although we have made many advancements in understanding the disease cycle, fungicide treatments and development of assessment tools such as petal testing, being able to get timely information to make timely decisions remains challenging. Petal testing for example took five to seven days to get results and technologies for measuring inoculum loads weren’t available or were quite time consuming. However, recent advancements in new technologies and availability of DNA and other testing techniques is very exciting and we launched a new project in 2019 to develop more accurate monitoring and risk assessment tools and techniques to allow for more timely disease management and control using fungicides.”

In this new three-year project funded via the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s Canola AgriScience Cluster, Turkington and other research partners across Western Canada are looking at developing new management tools and evaluating various fungicide treatments and timings for better management of sclerotinia stem rot in canola. The project is being conducted at nine locations across Western Canada plus one site at Normandin, Que. In addition, University of Alberta master’s student, Eleanor McBain, is involved in the project and also looking at evaluating potential risk

Sclerotinia fungicide timing experiment at Beaverlodge Research Farm, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Alberta, August 2019. In the foreground the rotorod sampler with a solar panel (left) and the Spornado (right), and in the background is the radiation shield housing for the external RH and temperature sensors.

assessment tools in commercial fields in the Edmonton area.

“One of the main components of the project is to look at the impact of different fungicide timings and treatments to improve disease control and economics,” Turkington explains. “We are test-

Sclerotinia experiment trials at the Canada-Saskatchewan Irrigation Diversification Centre/Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, in Outlook, Sask., July 2019.

ing a relatively new approach around fungicide timing developed over the past several years in the U.K. to see if there is an opportunity to implement the approach here in Western Canada. Their approach is to begin fungicide treatments and timing at the yellow bud stage, which is usually when the canola petals are just starting to get ready to emerge and the buds take on more of a yellowish tinge. This is the stage just before the start of flowering where there might be a few plants in the field with an odd petal here and there. A second application could then be made as the crop progresses to

Sclerotinia experiment with the Spornado and rotorod samplers in trials at Lacombe Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Alberta, August 2019.

the full or late bloom stages if warranted.”

To test the approach in Western Canada, the study compared a total of nine fungicide treatments, with single or split applications of Proline (prothioconazole) at different timings, including a control treatment with no fungicides. With the single application trials, the treatments are made at the yellow bud stage, or yellow bud stage plus one, two, three or four weeks. For the dual application trials, the treatments are made at the yellow bud stage, or yellow bud stage plus again at two, three or four weeks. With dual applica-

Put it at ease with an Advance Payments

CCGA Cash

Get the farm cash flow you need and the control you want to sell at the best time and the

Our experienced team makes it easy to apply. Call 1-866-745-2256 or visit ccga.ca/cash

Jeff Schoenau | Professor of Soil Fertility/Professional Agrologist

University of Saskatchewan

Investigating PGRs

Sheri Strydhorst | Agronomy Research Scientist

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Amy Mangin | PhD Student

University of Manitoba

Insect threats and beneficials

Tyler Wist | Research Scientist, Field Crop Entomology

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Saskatoon Research and Development Centre

Evaluating root rot and other pulse diseases

Syama Chatterton | Plant Pathologist

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Lethbridge Research and Development Centre

The future of neonics

John Gavloski | Entomologist

Manitoba Agriculture

Smart farming and a glimpse into the future

Joy Agnew | Director of Applied Research

Olds College Centre for Innovation

Maximizing fungicide use

Tom Wolf | Spray Application Specialist

Agrimetrix Research and Training

Tackling clubroot: disease updates, reducing risk and practical management

Dan Orchard | Agronomy Specialist

Canola Council of Canada

Curtis Henkelmann | Farmer

Alberta

tions, the chemicals are normally expected to be effective for two weeks or longer, therefore the yellow bud plus one week wasn’t included. For the project, researchers used only one fungicide product for the various treatments to remove any confounding factors in the research study with different active ingredients. However, Turkington emphasizes that growers should try to use different chemistries and options, particularly if making dual

With brand new varieties that redefine strong soybean performance across all zones, you’ll be creating your own soybean masterpiece before you know it. So when you’re selecting your soybean variety – go with Proven® Seed. No matter how you look at it, there’s a Proven Seed soybean that fits your farm. Only available at Nutrien Ag Solutions™. Learn more at ProvenSeed.ca

applications, and avoid using the same product multiple times, which could potentially increase the risk of fungicide resistance. For the fungicide component, researchers will be assessing disease at the end of the season for all of the different fungicide timings, as well as measuring yields, seed weights and other factors to help determine the impact of fungicide application and timing. Researchers also want to know whether single versus dual treatments and which timings are more effective. Layered on top of the fungicide treatments is another project component focused on the assessment of pathogen inoculum loads throughout the season. Providing information about the spore load present in a field at various timings will help determine the risk of infection and the best timing of fungicide application.

“We are utilizing two different spore traps in the field, including a rotorod sampler and the Spornado technology from 20/20 Seed Labs,” Turkington says. The rotorod sampler provides a quantitative method of collecting spores and calculating nanograms of sclerotinia DNA per unit of volume of air per unit of time. This is paired with the Spornado spore trap, a very easy to use and relatively inexpensive passive technology that provides qualitative information. By pairing the rotorod sampler measurements with the Spornado spore trap at each site, we hope to be able to come up with some rules of thumb for DNA results from the Spornado that would equate to a low or moderate or high risk of infection. Growers and consultants would be able to use a Spornado spore trap in their fields to assess risk, and by applying these ‘rules of thumb’ potentially assist with decisions regarding fungicide timing and frequency. We are also using two quantitative PCR DNA tests to develop a quantitative estimate of spore loads directly from collected petals, one from Discovery Seed Labs and another from Quantum Genetix, both located in Saskatoon. These provide another potential option to assess stem rot inoculum load.”

A third component of the project is environmental monitoring at each site, collecting weather, precipitation, temperature and relative humidity within and above crop canopy. This information will be combined with the inoculum load in the air as the crop is coming into flower and throughout flowering to help

to better understand changes in disease risk and subsequent crop response to fungicide timing and frequency.

“This is a very exciting time with the advancement in new tools and technologies that can quickly assess disease potential and help with management options and timing,” Turkington adds. “We are fortunate in Western Canada to have a range of commercial labs with the capacity to do DNA testing for a range of issues such as seed testing for Fusarium head blight, root tissue for clubroot or blackleg diseases and now for sclerotinia from aerial samples or petal tissues. Many of these DNA approaches allow a farmer or consultant to take a petal tissue or spore trap sample one day and have results back within 24 hours, which greatly improves their ability to make timely decisions regarding stem rot risk and fungicide use. It is really about bringing the newer DNA technologies together with the study of plant disease epidemiology. I’m passionate about this and the need to provide practical and timely decision-making tools to help farmers and crop consultants approach sclerotinia management and improve their ability to assess risk and control the disease with fungicides.”

The project will continue for another two years, and by the end researchers plan to have better tools and risk assessment strategies for more timely decision-making and timing of fungicide application. “Based on the potential yellow bud timing approach, inoculum load assessments and the impact of different fungicide timings and treatments, we look forward to being able to improve risk assessment, disease control and the economics of managing sclerotinia stem rot in canola.”

Continued from page 15 involves growing more than one crop in the same field at the same time. In a field experiment in Manitoba, wheat, canola and pea were grown as sole crops and in intercrops including a three-way intercrop. Weed biomass was generally lower in the intercrops. Wheat-canola and canola-pea gave the best weed suppression.

“The idea with an intercrop is that the crop is better adapted to environmental conditions and will utilize more of the niche space that would have been available to weeds,” Geddes says.

Cover crops are also a cultural weed management tool. Cover crops can be used to suppress weeds and prevent erosion as a fallow substitute. Fall rye seeded after harvest has also been used to provide weed suppression and erosion protection in longer growing season areas.

Implementing these cultural weed management practices can take an investment in time and input cost. However, Geddes says that the practices can eventually pay off.

“In order to wrap our heads around it, we have to look at the longer term. If we implement the practices consistently, we will see benefits down the road with lower weed pressure and reduced selection pressure on herbicide-resistant biotypes,” Geddes says.

Higher rates of P fertilizer should be side-banded to minimize seed damage and maximize yields.

by Donna Fleury

Phosphorus (P) fertilizer management is important for all crops including canola, to ensure high productivity in the crop year and to maintain productivity of soils over the long-term. However, in Saskatchewan, most soils are deficient in available phosphate (P2O5) as removal rates are often higher than replacement rates. Strategies that allow growers to economically apply as much or more P than is removed, are crucial for sustainable crop production throughout Saskatchewan.

“As newer canola hybrids allow for higher yields to be reached, higher rates of P are required to achieve maximum yields; however, the safe rates for seed-row placement are typically insufficient for yield optimization,” says Jessica Pratchler, research manager with the Northeast Agriculture Research Foundation (NARF) in Melfort, Sask. “Growers are often required to apply P at rates that exceed the maximum recommended safe rates for seed-row P to satisfy canola’s P requirements in the year of application and to maintain soil fertility. If high rates of seed-placed P fertilizer are applied, seed damage can occur resulting in delayed emergence, reduced plant stand, seed yield, seed quality and increased weed competition. Furthermore, safe rates of seed-row placed P are not always sufficient to offset crop removal, further depleting soil P reserves. Therefore, producers question how to best apply these high rates and seek out what the best recommendations are for high yielding canola production.”

A three-year project was initiated in 2016 in Saskatchewan to help determine how to best apply high P rates for high yielding canola production, and to provide the basis for updating the fertilizer P rate and placement recommendations for canola production. The project was carried out at three locations across the province, including Scott, Indian Head and Melfort. The objective of the study was to evaluate the impact of rate and placement of fertilizer phosphate, either alone or in combination with fertilizer sulphur (S), on canola P-uptake and yield across a range of soil and climatic conditions in Saskatchewan.

In the study, five fertilizer P2O5 rates were compared including 0, 20, 40, 60, and 80 kg/ha using monoammonium phosphate (11-52-0 [MAP]) and various placement methods, including sideband, seed-placed, and seed-placed with fertilizer S as ammonium sulphate (21-0-0-24; 15AS), for a total of 15 individual treatments at each location. All plots were established on cereal stubble and seeded with L140P (Liberty Link tolerant) canola and under typical agronomic management practices.

“Our study results showed that responses to high rates of sidebanded P were always equal to or greater than seed-placed,” Pratchler says. “As well, no rate of seed-placed P was found to be safe, as damage occurred at very low rates. It was also very difficult to predict the degree of damage from seed-placed P fertilizer due to soil characteristics and spring moisture, which can change across the landscape. Overall, side-banding P is the best method for applying higher rates and has less potential for seedling damage. Sidebanding is a great option for trying to increase P levels above the minimum of 15 ppm standard rate for soil available P. However, we recognize that logistics will always trump agronomy, so sidebanding may not always be an option.”

Yields were also affected by P rates, with canola yields generally increasing as P fertilizer rates increased. Optimal yields were reached between 70 and 80 kg/ha of fertilizer P. However, plant populations declined significantly as P rates increased with both

InVigor® hybrid canola and Liberty® herbicide are now part of the BASF Ag Rewards Program—and the rewards are bigger than they’ve ever been. We’re talking earnings as high as 22%.1

To learn more, contact your BASF AgSolutions® Representative, call AgSolutions Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273). You can also visit agsolutions.ca/rewards.

seed-placed and SP + 15AS treatments, but not with the side-band placement. The results showed that applying even a small amount of ammonium sulphate to the seed-row is detrimental to crop establishment and can have a negative additive effect to seed-placed P. Overall, there was a high degree of risk associated with seed-placed fertilizer when soil and climatic conditions are conducive to high levels of fertilizer damage. Therefore, if high rates of phosphorus are required, fertilizer P should be side-banded to minimize seed damage and maximize yields, as it was the most consistent and beneficial application method.

“Although the study only looked at the canola phase in rotation, it is important to consider P management and the implications to the whole cropping system and how to manage across all crops in the rotation,” Pratchler says. “Finding ways to replenish and build P reserves to offset removal rates will continue to be more important as growers try to optimize yields across all crops. Crops such as wheat don’t remove as much P as crops like canola or pulses, so there may be an opportunity to build P level reserves in the wheat year of rotation, and have higher levels available for the subsequent canola crop. Or side-banding higher rates of P in the canola crop may be enough for the subsequent pulse crop, and then to replace higher P levels in the following wheat crop.”

Pratchler adds, this study provides a good base to realize that we can push P rates as a management tool for increasing yields and soil P levels, however, there are several different logistical factors that need to be considered as well. “Although we didn’t include mid-row banding treatments in this study, there may also be an opportunity to seed-place safe rates of P and apply the rest in a mid-row band as another alternative. Overall P levels are fairly low in Saskatchewan soils, so to take full advantage of the yield potential of new canola varieties and other higher yielding crops that utilize more P, higher rates will need to be planned for.

Overall, the study demonstrates that optimal phosphorus management practices have changed for growing canola in Saskatchewan, and the current phosphorus fertilizer recommendations should be reconsidered for the high yielding cultivars currently used.”

by Bruce Barker

Blackleg just doesn’t go away. With many different and evolving pathotypes, researchers and plant breeders are trying to stay one step ahead of the disease. Research scientist Gary Peng with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon has been working on blackleg as one of his disease priorities for many years.

“Even after 10 years there are still questions that we are working on,” says Peng, who summarized what researchers know about the disease at the Manitoba Agronomist Update conference last winter.

Peng says that blackleg behaves differently on the Prairies than other parts of the world. In Canada, our growing season is around 100 days, compared to 200 in Australia and 300 in Europe. As a result, early infection of a canola plant, especially on cotyledons, by the pathogen is critical for disease development, and this early infection has management implications.

In the 1990s before blackleg resistant varieties were developed, blackleg had become a major disease problem in Western Canada with incidence in the 50 to 60 per cent range. After resistance

varieties were developed in the early 1990s and with longer crop rotations than today, blackleg incidence dropped to very low levels. But Peng says that starting around 2010, incidence has trended upward and is currently sitting at around 10 to 15 per cent, depending on the year and area.

“The big question is ‘what is causing it to creep up?’ We don’t really know for certain, but we know of some of the possible explanations,” Peng says.

One possible reason that the reported incidence has trended upward recently is that there is more scouting and formal surveys being conducted, led by the each of the Prairie provinces’ agriculture ministries. Essentially, if you look for something, you’re more likely to find it. But Peng says increased scouting for blackleg is a good thing, as it helps farmers, agronomists and researchers keep track of the disease.

ABOVE: Blackleg causes premature ripening in canola.

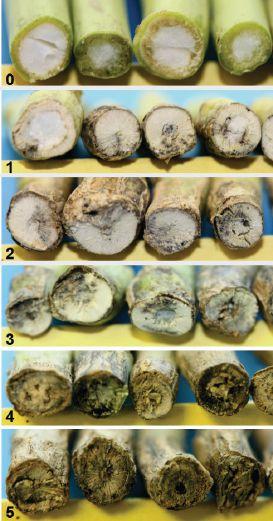

0 No diseased tissue visible in the cross section.

1 Diseased tissue occupies 25% or less of cross section.

2 Diseased tissue occupies 26% to 50% of cross section.

3 Diseased tissue occupies 51% to 75% of cross section.

4 Diseased tissue occupies 7% or more of cross section.

5 Diseased tissue occupies 100% of cross section, with significant constriction of affected tissues; tissues dry and brittle; plant dead.

“Of all the management strategies that can be done on the farm, scouting is the most important, because it helps to guide other management strategies,” Peng says. “On the Prairies, we’re still dealing with relatively low incidence, so scouting can help keep track of the disease on individual fields.”