There’s more behind every bag of InVigor® hybrid canola.

• Western Canada’s most trusted lineup of high-yielding canola hybrids

• Patented Pod Shatter Reduction technology

• Complete crop protection portfolio, including Cotegra® fungicide

• InVigor support programs to help get your crop off to a great start

Visit agsolutions.ca/InVigor to learn more.

The race is on, ever since the Canadian Food Inspection Agency announced in May 2023 that gene-edited seeds would be regulated the same as conventionally bred seed varieties, Canadian researchers are investigating how gene editing could be applied to Canadian crops. The first Canadian field trial was conducted in 2024.

Optimizing pea production in Manitoba.

8 Oat protein’s potential

Oat protein and heart health benefits. CEREALS 12 Pest scouting calendar for cereals

Seed at a soil temperature trigger 2–6 C. TILLAGE AND SEEDING 14 Plant spacing in wheat

Narrower is better.

First case in 2021 in Saskatchewan.

Weed suppression possibilities.

ON THE COVER: Long-term field trials to evaluate the performance of rotations that include pea and/or soybean in combination with wheat and canola. Photo courtesy of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

by Kaitlin Berger

We don’t really care what consumers think.

I know that’s a bold statement, but it’s the sentiment Michele Payn, a speaker at this year’s Crossroads Crop Conference gave before diving into her keynote address on the importance of communicating relevancy, clarity and trust to the public – whether we feel like it or not. Her point was that many of us might prefer not to engage with consumers about what we do, preferring to spend our time in the tractor or the combine or the shop. And even if we do care, producing food takes away a lot of free time. We know producers, agronomists and researchers are doing an excellent job, so why should we tell anyone else about it.

People understand stories...so don’t forget to share yours.

Of course, there are countless producers in Canada who are actively engaging in the essential work of educating the public about agriculture. Some are involved with Agriculture in the Classroom (AITC). Others are giving tours of their farms. Some are brave enough to showcase their farm and their life on social media or willing to give the time to participate on the boards of their crop commissions. Reviewing some of the statistics from the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity’s (CCFI) 2024 Public Trust Research report, I tend to agree with Payn that it’s becoming more and more important to engage whether we like it or not. According to the report, only three in ten Canadians believe our food system is on the right track. Not super optimistic, right? Thankfully, there’s good news too. The opportunity is in who respondents rated as the most highly trusted player in the Canadian food system: farmers. Who is honest? Again, they rated farmers the highest. When comparing trust for the agriculture and food industry to other industries such as education, healthcare, oil and gas, automotive and forestry, it also came out the highest. While the report shows that pessimism about our food system is high among consumers, the numbers show opportunity for farmers – and specifically farmers – to be the ones to turn that around. Payn suggested data and factual explanations are not necessarily the way to do this. Some people’s only connection to food is the grocery store, so it’s essential to connect with them in a way they understand and that aligns with their values. For example, sustainability is a core value the average Canadian shares. If you can connect an educational fact to the value of sustainability, it’s more likely to resonate.

And finally, people understand stories. They remember stories. They empathize with stories, so don’t forget to share yours.

Fax: (416) 510-6875 Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor KAITLIN BERGER (403) 470-4432 kberger@annexbusinessmedia.com

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Coordinator LAYLA SAMEL (416) 510-5187 lsamel@annexbusinessmedia.com

Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW

CEO SCOTT JAMIESON sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

We design our solutions to match the passion and expertise of Western Canada’s finest farmers, helping you unlock the full potential of your fields. Together, we’re not just cultivating cereal crops; we’re cultivating success stories that will be passed down for generations to come.

Discover the entire lineup of Syngenta cereal solutions

To learn more, visit Syngenta.ca, speak to your local Syngenta representative or contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682).

Optimizing pea production in Manitoba rotations with wheat and canola.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Crop rotations in Manitoba have changed over the last number of years with a significant increase in soybean acreage in the province and a resurgence in field peas. Canola, wheat and soybeans are currently the top three crops in Manitoba. Researchers and industry are interested in understanding how crop diversity and length of rotation affects productivity and other factors.

“This crop mix of canola, wheat, soybean and pea has made Manitoba unique and sets it apart from much of the rest of Western Canada and elsewhere,” says Ramona Mohr, research scientist at Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC) in Brandon, Man. “There are few places in Canada and elsewhere that are growing this combination of crops in short season conditions. We initiated a long-term study in 2019 to assess various crop rotations and length of rotations to determine not only their agronomic performance, but also economic and environmental influences. The establishment phase of the rotation study and a completion of one full rotation cycle was completed in 2023, and we are now in the second phase

through to 2026 to be able to more fully assess productivity, diseases, soil factors and economics.”

The objective of this study is to evaluate the performance of rotations that include pea and/or soybean in combination with wheat and canola. The study includes three- and four-year rotations with pea, soybean or both crops, and with pea grown two to four years apart. Recommended varieties of glyphosate-tolerant soybean (S), yellow field pea (P), Canadian Western Red Spring (CWRS) wheat (W) and Liberty-tolerant canola (C) were grown.

Although much of the focus of this study is on pea and soybean, data is also being collected for canola and wheat in rotation to assess certain crop sequences or lengths of rotation that might be beneficial as well. Along with yield and quality impacts of the various rotations, other factors such as soil factors, disease incidence and severity for root rot and Fusarium head blight are being assessed. An economic and risk analysis of the various rotations will be completed toward the end of the project.

“The results of the study so far are still very preliminary, but we have seen some trends suggesting a

LEFT Long-term field trials to evaluate the performance of rotations that include pea and/or soybean in combination with wheat and canola.

BELOW Assessing various crop rotations and length of rotations to determine agronomic performance, economic and environmental influences.

benefit of more diverse and longer rotations on pea yield in the short-term,” says Mohr. “As the study progresses, we will have more longer-term results to share. Because effects of rotation on the plant-soil system often build up slowly over time, those rotations that perform well in the short-term are not guaranteed to be the most sustainable in the longer-term. So far, study treatment differences observed were due to the effect of the preceding crop or crops, rather than due to the overall rotation. While preliminary trends suggest that more diverse crop sequences may be beneficial for pea even in the shorter-term, additional years of data are required to confirm the performance of these rotations over time. Manitoba guidelines recommend a minimum four years between pea crops to manage disease. Although the study results so far are not statistically significant, the trend suggests that the two-year pea rotation does not seem to be performing as well as the longer-term rotation.”

Disease assessments for root rot in pea and soybean crops are being conducted by Yong Min Kim, AAFC pathologist in Brandon, Man. The main goal is to understand how different crop sequences impact disease incidence and severity, particularly for root diseases in pea and soybean in combination with wheat and canola. Disease assessments were completed in the field from 2019 to 2023 and root tissues of infected pea and soybean plants analyzed in the lab for root rot pathogens. Preliminary results show that the most common root rot pathogen belongs to Fusarium species.

“Preliminary study results across all of the crop treatments showed no significant differences between

treatments over the five years,” says Kim. “However, the five-year average trend for root rot severity in soybean was slightly higher in the three-year rotation treatments compared to four-year rotations. Using a severity rating scale of zero to nine, the early results show an average severity of 3.43 in the three-year CWS rotation compared to averages of 3.37 for SCWP and 3.28 for SWCP in four-year rotations. Although the differences across all treatments for peas was not significant, the trend showed that the rotation with frequent legumes has higher disease severity. The PCPW rotation had the highest root rot severity at 3.39, while the four-year SCWP had the lowest. In addition, wheat as a preceding crop before pea showed a trend of higher disease severity on pea, while canola as a preceding crop showed lower disease severity on pea.”

Kim adds, although the differences so far are small and not statistically significant, including an additional crop in rotation may help reduce disease severity over time. “Longer rotations especially those involving diverse crops tend to show lower root rot severity compared to shorter rotations, potentially reducing pathogen carryover and host-specific pathogen inoculum buildup. Although soybean, pea and wheat can share some common root rot pathogens such as Fusarium, diversifying rotations by incorporating non-legume crops such as canola may break disease cycles and suppress the buildup of crop-specific pathogens such as Phytophthora root rot in soybean and Aphanomyces root rot in peas. It is too early in the study to draw conclusions, but we look forward to the additional results over the next few years of the project.”

The study will continue through 2026 to better understand long-term effects of rotations. “Once we have more information from the long-term rotations, collaborating AAFC researcher Mohammad Khakbazan will be conducting an economic and risk analysis of the different rotations from the study,” explains Mohr. “We will be combining the data collected from this study along with other rotations studies to develop a rotation calculator. The goal of the calculator is to provide producers with a tool to compare different rotations using a combination of research data and some of their own on-farm information.

“A second aspect is to look at the impact of different rotation sequences on soil factors and to compare the energy balance and environmental footprint of different rotations,” says Mohr. “Bringing all of this information together will provide producers with the agronomics of how different rotations perform in terms of yield, quality and diseases, as well as the performance in terms of profitability and input use efficiency over the longer-term.”

Prairie research indicates oat protein might have heart health benefits and more.

BY CAROLYN KING

You have probably heard about the impressive health-promoting benefits of oat fibre. Now, the results from some recent research led by Dr. Sijo Joseph (Thandapilly) are pointing to the possibility that oat protein might join oat fibre in the nutritional spotlight.

Research studies have linked beta-glucan, a dietary fibre in oats, to several health benefits such as reducing risk factors associated with heart disease and diabetes, like high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure and high post-meal blood glucose levels (or glycemic response). Some of these benefits have sufficiently rigorous scientific proof to be approved health claims by authorities such as Health Canada.

“The cholesterol-lowering ability of beta-glucan is very well documented and supported by various health authorities including Health Canada, the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority,” notes Joseph, a cereal nutrition research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). “Additionally, beta-glucan has been approved in Europe for reducing post-meal blood glucose values and also a digestive function.”

Emerging research suggests that beta-glucan may also help to lower blood pressure, but this is a preliminary finding and not yet substantiated. “Furthermore, compounds called avenanthramides, which are unique to oats, have been shown to improve glycemic response in our studies,” he says. Avenanthramides have other health-related properties too; for example, they are used in certain skincare products because of their anti-inflammatory and anti-itch properties.

But what about oat protein? “Despite oats containing a relatively high protein content of 15 to 20 per cent –which interestingly is gluten-free protein – plus having a good amino acid profile, the nutritional benefits of oat protein had remained underexplored,” notes Joseph,

who is based at the Richardson Centre for Food Technology and Research (RCFTR) in Winnipeg.

“So, given the growing popularity of plant-based proteins, we sought to investigate the health benefits of oat-derived protein,” he says, “how oat protein is digested, and what the health benefits are in humans.”

ABOVE Oat protein extracted from Canadian oats.

Joseph collaborated with two other AAFC research scientists on animal feeding studies for preliminary assessments of the nutritional effects of oat protein. He worked with Dr. Thomas Netticadan at the Canadian Centre for Agri-Food Research in Health and Medicine (CCARM) on conducting the animal feeding experiments and with Dr. Lovemore Malunga at RCFTR on the extraction of pure proteins from Canadian oats.

The research team conducted two studies to look at the effects of an oat protein-based diet in relation to two different types of cardiovascular problems, using two different animal models.

Their first study, led by Joseph, related to heart problems that arise when people eat a high fat, high cholesterol, high sugar diet and develop obesity, which then induces cardiovascular problems. So, the team fed experimental rats a high fat/high sugar diet, like a normal western diet. Due to that diet, the rats became obese and developed associated problems like high cholesterol.

Then, the team fed one group of these obese rats with the high fat/high sugar diet, which had a milk-derived protein called casein as the conventional protein source. For comparison, they fed the other group of obese rats with the same diet except that oat protein was used as the protein source.

After 16 weeks of feeding, the team assessed the cardiovascular health of the two groups, through blood analysis, blood pressure measurements and several other tests, including cardiovascular evaluations using echocardiograms, which are ultrasounds that look at the heart’s structure and function.

Their results indicated that oat protein had benefits for cardiovascular health in obese rats. In particular, oat protein reduced bad cholesterol (or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol) and also enhanced the cardiac function of the heart.

When the researchers saw the strong results from the first study, they wondered about the possible beneficial effects of oat protein for another type of problem – high blood pressure, or hypertension, which leads to blood-pressure-related cardiovascular problems. So, their second study, led by Netticadan, involved experimental rats specially bred to develop hypertension. These rats develop hypertension by about five to six weeks of age and, within a few more weeks, they develop cardiovascular complications.

For 16 weeks, the team fed one group of these hypertensive rats with a normal diet with casein as the protein source, and they fed the other group with an oat protein-based diet. They carried out a variety of tests such as blood pressure measurements and echocardiograms. Their findings showed that the rats fed the oat protein-based diet had significantly lowered blood pressure levels as well as beneficial effects for heart structure and function.

The researchers published peer-reviewed papers about these two studies in scientific journals in 2024. “This research is very promising and very novel,” says Joseph.

“The cholesterol-lowering ability of beta-glucan is very well documented and supported by various health authorities including Health Canada...”

“In the first animal model, the obesity-based cardiovascular complications, which include risk factors such as high cholesterol, were reduced with an oat protein diet. And in the second model, blood pressure was reduced and heart function was improved with an oat protein diet,” summarize Joseph and Netticadan.

“These are two independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease in humans, and both were improved by oat protein. Also, using echocardiograms, we found that some of the early indications of abnormalities in heart structure and function were improved with oat protein.”

These studies were supported under AAFC’s Agri-Science Program with funding from AAFC and the Prairie Oat Growers Association (POGA) as the stakeholder partner.

The researchers’ next step is to conduct human feeding trials. “Sometimes the way protein is metabolized in animals may be different in humans. So, we need to conduct a human study to show the same type of effect in a human setting,” explains Netticadan. “We will probably be seeking funding in the near future to develop an oat protein-based food for humans and then also to look at how oat protein is digested and metabolized and what the health benefits are in humans.”

Preparing for these human feeding trials takes time. For instance, the researchers need to come up with practical oat protein-based food products. These products must be palatable so participants will be willing to continue eating the products for the several weeks needed

to complete the trial. The products must also provide adequate levels of oat protein so that any differences due to eating the oat protein can be detected, despite participants having other protein sources such as milk, eggs and meat in their diets.

“I think there is great potential for greater use of oat protein in food products for multiple reasons. One is that oat protein, unlike wheat and barley protein, is gluten-free so it is more widely accepted,” says Joseph.

“Secondly, oat protein has a good amino acid profile and a very good digestibility profile,” he explains. “In many other cereals, one of the essential amino acids, lysine, is a limiting. Lysine is also low in oats but the level is higher than in many other cereals. In addition, oat protein can be digested very well by the body and it can make the amino acids available for the body to be absorbed.”

“And the third reason is that, based on our initial extraction process that we were testing, oat protein has a very neutral taste, unlike other plant-based proteins,” he notes. “So, it could be sold as is, as a protein supplement that you could use in smoothies or shakes, or it could be used as an ingredient in protein bars and many other food products.”

In addition, Malunga and the team are working to explore possible uses for oat starch. That’s because, once oat protein is extracted from oats, the oat starch remains as a major waste component. The researchers are looking for opportunities to transform that waste into valuable byproducts for food processors. Malunga is leading one study to develop oat starch-based noodles and another study to use oat starch to make edible coatings, similar to wax coatings, to extend the shelflife of fresh fruits and vegetables.

POGA’s executive director Shawna Mathieson says this: “People are looking for higher protein and higher fibre foods, especially in plant-based foods. This oat protein research could directly tie both of those benefits back to oats, which are already known to be a high fibre, filling food. In addition, the fact that oats are naturally gluten-free could provide more incentive for those with celiac or gluten sensitivities to increase their protein intake by consuming more oats and oat-derived protein.”

Another exciting possibility is that oat protein might turn out to be eligible for another approved health claim for oats. “Our studies along with other studies from other groups in the past have shown that beta-glucan fibre in oats lowers cholesterol by scavenging or

removing circulating fat or fat-digesting compounds, called bile acids, from our bodies and eliminating them through the feces,” says Joseph. “Interestingly, oat protein appears to work totally differently.”

The research team’s studies with animals indicate that oat protein seems to lower cholesterol by inhibiting an enzyme involved in cholesterol production in the liver. Joseph notes that statins, a group of cholesterol-lowering drugs, work in a similar way by inhibiting that same enzyme, which is an important way of reducing cholesterol levels in people.

“Only roughly 30 per cent of our cholesterol is taken in through our diet. The rest of the cholesterol is synthesized within our body. So, if we can reduce the activity of that enzyme, we can definitely reduce the level of cholesterol production,” he explains. “Since oat fibre and oat protein work through different mechanisms, combining them could have an additional or synergetic effect on lowering cholesterol.”

If more studies, including human studies, provide substantiated scientific evidence that oat protein independently reduces cholesterol using a different mechanism than beta-glucan, that evidence could be submitted to Health Canada for review as a possible additional health claim for oats. According to Joseph, soon after the health claims about cholesterol lowering due to beta-glucan fibre were approved by health authorities, oat consumption increased in Canada and globally.

“Due to the current lifestyle, a lot of people have very high levels of cholesterol which is a risk factor for heart disease. So, people are trying to manage their cholesterol levels through cholesterol-lowering drugs and also through their diet. And oats have a big role to play as a major vehicle for getting an adequate level of beta-glucan in people’s diets,” he says. “Having additional health claims for oats would definitely boost the consumption of oats and oat-derived products, and it will improve the market for Canadian oats, not just in Canada but all around the world.”

Mathieson notes that Canada is the world’s largest exporter of oats. An additional health claim could be important for Canadian oat growers and especially Prairie oat growers, who produce about 90 per cent of Canadian oats. “Doctors Joseph, Netticadan and Malunga’s research is very exciting and shows promise for the health benefits of oat protein.”

“If these benefits are confirmed,” she adds, “it could have a similar effect to the work done on fibre/beta-glucan, which included increased oat consumption for people with high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes and obesity, just to name a few. ‘Superfoods’ like oats are great for consumers, producers and the oat industry.”

Do you know an influential and innovative woman in Canadian agriculture? We’re looking for six women making a difference in the industry. This includes women in:

• Farm ownership and operations

• Ag advocacy and policy

• Research and education

• Agronomy

• Business development

• … and more!

BY BRUCE BARKER

Research at the University of Manitoba looked into the Goldilocks moment for wheat row spacing and seeding rate: not too wide, not too narrow, but something just right. The research was led by Robert Gulden, professor of plant science at the University of Manitoba.

“When we did the research, there was a lot of interest by grower groups to revisit plant spatial arrangement to see if the recommendations from years ago still hold,” says Gulden. “Interestingly, no one seems to know where the recommendations for wheat came from. We were doing similar research and had built the first drill capable of doing multiple row spacings without having all openers in the ground, so the tool and the research ideas came together to revisit some of the old recommendations.”

The research looked at the optimum row spacing and seeding density impact on yield for two spring wheat varieties and if seeding into canola or soybean stubble affects this relationship. Current provincial seeding rate recommendations, which are over 25 years old, recommend 25 to 30 plants per square foot (246 to 300 plants/ m2). No recommendations exist for row spacing.

Two popular CWRS wheat varieties, AAC Brandon and Cardale, were used in the trials and seeded into either soybean or canola stubble. Seeding rate treatments were at 20, 30, 40 and 50 seeds/ft2 (200, 300, 400 and

ABOVE Wheat row spacing may need to be rethought.

500 seeds/m2). Row spacing was at 3.75, 7.5 and fifteen inch (9.5, 19 and 38 cm) depending on the year. The sites were no-till seeded.

While nine- to twelve-inch row spacing is common on Prairie farms, Gulden chose those row spacings for several reasons. His drill was capable of row spacings in multiples of 7.5 inches and double seeding got the spacing into the four-inch range.

“I was interested in the narrower spacings because we saw in our bean work that reducing row spacing was more important and consistent at increasing yields than crop density within our usual range,” he says. “Furthermore, from a crop-weed competition perspective, narrower rows make for a more competitive crop and that is key to managing weeds and herbicide resistance. The 3.75-inch spacing where we double seeded was to emulate pre-herbicide plant spatial arrangement where wheat was seeded at rows as narrow as four-inch row spacing. A few of those old drills are still out there parked in the bush.”

This project ran from 2017 to 2021 at Carman, Howden and Portage la Prairie, Man. All site years experienced drought conditions, receiving 43 to 75 per cent of the long-term precipitation average.

Spring wheat emergence, ground cover, plant height, above-ground plant biomass, headcounts, seed yield, thousand seed weight (TSW) and grain protein were collected. Ground cover data was collected with digital image analysis with overhead photos used to estimate percentage ground cover.

Narrow row spacing treatments did result in increased and more rapid ground cover, suggesting improved water, sunlight and nutrient utilization by the wheat plants, and increased competition with weeds.

Seed yields averaged from 35 to 65 bushels per acre (2,351 to 4,336 kg/ha). AAC Brandon outyielded Cardale at all site-years.

The site-years were broken into high, medium and low yield environments. High yield included Carman 2018B and Howden 2020 with an average yield of 60 bu./ac. (4,033 kg/ha). Sites with medium yield included Carman 2017, Carman 2018A, Carman 2020, Howden 2019 and Portage la Prairie 2019 with an average yield of 49 bu./ac. (3,266 kg ha). Low yield sites at Carman 2019 and Howden 2021 yielded 35 bu./ac. (2,358 kg/ ha).

When grouped by environment, the analysis found that row spacing was the most important factor impacting yield – and not seeding density. Narrower row spacing at 3.75 and 7.5 inches consistently had higher wheat yield than when seeded at fifteen inches.

At the low-yielding environments, wheat seeded at 7.5 inches yielded 5.1 per cent more than the 3.7-inch row spacing and 24 per cent more than the fifteen-inch row spacing.

At the medium-yielding sites, yields were similar on canola stubble for the 3.7- and 7.5-inch row spacing and higher than the fifteen-inch row spacing. On soybean stubble, the 7.5-inch row spacing was significantly higher than the other two row spacings.

At the high-yielding environments, yields were similar at the 3.7- and 7.5-inch row spacing and averaged 14.2 per cent higher yield than the fifteen-inch row spacing.

Seeding density, surprisingly, had little effect on wheat yield. In the few instances that it did, higher seeding rates decreased wheat yield. Neither AAC Brandon or Cardale yield differed in their response to increased densities. Full canopy closure was not achieved across the site-years at the fifteen-inch row spacing. Gulden says this result was expected as plants at wider row spacings occupy a smaller portion of the soil surface when compared with plants at narrower row spacings. Occasionally, increased densities resulted in slight reductions in seed protein levels.

Gulden reported that decreasing the seeding rate below 25 plants/ft2 may have negative consequences not evaluated in this study. Lower seeding rates may result in non-uniform stands which may increase tillering and extend the flowering and maturation periods. This may make the timing of fungicide applications and harvest more challenging. In addition, decreased seeding rates may increase weed pressure, weed biomass and weed seed return to the seedbank.

Overall, the research found that seeding at narrower row spacings of 3.75 or 7.5 inches at recommended

LYE: Low-yielding environment; MYE: Mediumyielding environment; HYE: High-yielding environment.

seeding rates will help optimize yield in dry growing seasons in Manitoba or, perhaps, in other areas of the Prairies with a semi-arid growing season.

“For farmers that use wider row spacing, the research means that they may not be reaching their yield potential in some or many years. It also means that at wider row spacings, herbicides are working harder than they should and that the selection pressure for herbicide resistance is greater in those systems than in those where the crop is able to help out more with weed control,” says Gulden.

“It also means that when purchasing a seeder, row spacing should be an important consideration, because it’s been shown that in a number of crops, we can do better with narrower row spacing than is the current norm.”

Equipment constraints, though, hinder the adoption of row spacings narrower of 7.5 inches or less for that ‘just right’ Goldilocks moment. “Maybe we need to rethink seeder design so that we can get the residue clearance while seeding at more narrow rows,” says Gulden.

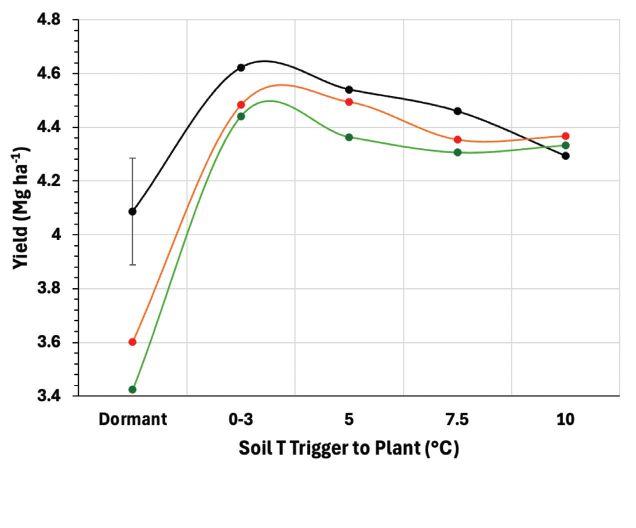

Seed at a soil temperature trigger between 2–6 C.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Some durum farmers seed by calendar date. Others when pussy willows come out. Or when aspen grooves are in full leaf. Or by the crop insurance cut-off date. Or when soil temperatures get above 10 C, as suggested by some agricultural departments. But there’s a paradigm shift happening with research from Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC): seeding durum ultra-early – even before robins have migrated back to the Prairies in the spring.

“Seeding ultra-early is a strategy to help deal with changing climate and increased average growing season temperatures,” says Brian Beres, research scientist with AAFC Lethbridge, Alta. “We’ve got over 50 site years of research showing that seeding hard red spring wheat at a soil temperature of 0–3 C in the top two inches of soil is the sweet spot for yield and yield stability.”

In Beres’ research on Canada Western Red Spring (CWRS) wheat, seeding at a soil temperature trigger of 10 C produced the lowest yield at 68 bu./ac. (4.57 tonnes/ha) with the highest yield of 74 bu./ac. (4.95 tonnes/ha) occurring when spring wheat was sown at 0–2.5 C. He attributes the difference to shifting the critical growth period – the onset of stem joint through 10 days after flowering – one month earlier when high temperatures can partially be avoided.

Based on the success of CWRS wheat, Beres turned his research attention to durum wheat with a threeyear research program funded by the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission running from 2022 through 2024. Two experiments were conducted at Lethbridge, Alta. and Saskatoon, Indian Head and Swift Current, Sask.

The first experiment compared trigger temperatures at a two-inch depth (5 cm) at intervals of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 C. The earliest seeding date was at Lethbridge on February 9, 2022 for the 0 C trigger planting. That treatment had 69 days below 0 C after seeding with the lowest temperature recorded at –29 C. The five durum varieties compared were AAC Donlow, CDC Defy, CDC Desire, AAC Stronghold and AC Transcend.

ABOVE Ultra-early seeded durum had higher yield and yield stability.

The second experiment compared CDC Defy, AAC Stronghold and AC Transcend seeded at one or three inches deep. Triggers were dormant seeded in late fall/ early winter when soil temperatures fell to less than 0–2 C. Spring temperature triggers were 0 to 3, 5, 7.5 and 10 C.

PRELIMINARY RESULTS FAVOUR ULTRA-EARLY SEEDING

While the full analysis is still underway, preliminary results for the first experiment show that ultra-early durum yield and stability mirrors the results for CWRS

RIGHT Durum seed quality was high with ultra-early seeding.

research. No yield difference was observed among AAC Donlow, CDC Defy and AAC Stronghold, but CDC Desire trended lower and AC Transcend had significantly lower yield.

Beres says the downward yield trend observed with later plantings is likely attributed to sensitivity to abiotic stress such as heat and drought stress, as crop growth and development are not completed before the onset of heat or drought in semi-arid Prairie locations. There was a trend to higher grain protein with warmer trigger temperatures, but the preliminary results showed it was not linearly or quadratically significant. The first two years of data showed the 0 C trigger had the lowest protein content at 14.4 per cent and the 10 C planting had 14.7 per cent grain protein.

The second preliminary experiment results showed that fall dormant seeding had the lowest yield by a large margin. Similar to the first experiment, the earliest spring soil trigger of 0–3 C yielded the highest with a linear decrease in yield as soil trigger temperatures increased. There was a trend for CDC Defy to have higher yield than AAC Stronghold and AC Transcend. The one-inch seeding depth favoured higher yields across all seeding temperatures in the spring. However, the three-inch seeding depth had higher yields when durum was dormant planted in the fall. This may have been the result of shallow, dormant-planted

durum germinating when temperatures fluctuated over the fall/winter months. Yield stability for dormant-planted durum was also highly variable.

“Dormant planting in fall tended to produce binary results – either the crop establishment was acceptable and produced okay yield or it was a train wreck. For example, the dormant treatment produced acceptable grain yield at the Lethbridge dryland site in the 2022 season, while it was entirely unsuccessful in the 2023 season,” says Beres.

Overall, Beres says that both experiments indicate that ultra-early planting of durum has no detrimental effect on Canada Western Amber Durum (CWAD) grain yield in western Canadian growing environments. Planting durum wheat as early as when the top twoinch soil temperatures are between 2 and 6 C

“Dormant planting in fall tended to produce binary results – either the crop establishment was acceptable and produced okay yield or it was a train wreck.”

consistently resulted in high and often stable grain yield, regardless of variety.

“This isn’t to say you will improve yield with ultra-early planting every year, but you will almost definitely protect it while enjoying a lot of intangible benefits. It’s obviously easier for us in Lethbridge to plant at 2 C every year compared to say Indian Head, and that’s reflected in the variability of the yield data, but I think we’ve all been surprised at how most areas in Alberta and Saskatchewan have been able to go much earlier than what was considered feasible and free of risk,” says Beres.

In conducting an economic analysis of these two experiments for the first two years, and based on 2023 prices, ultra-early planted durum produced higher net returns. Averaged across all locations, cultivars and sowing depths, an increase of $45/ac. ($112/ha) occurred when planting at 0–3 C soil trigger temperature compared to delayed plantings when the soil temperature was 10 C. The increased returns were even higher for CDC Defy with a net return increase of $59/ac. ($146/ha).

For farmers wanting to try ultra-early seeding, Beres recommends seeding shallow, consider a fungicide/

insecticide seed treatment and laying down a fall-applied soil residual herbicide to replace a spring pre-seed burnoff.

“What ultra-early seeding programs capture is some of the benefits of a winter wheat system. By shifting the critical growth period into June, it helps to avoid flower abortions from higher summer temperatures, resulting in increased yield and yield stability. This was best exemplified in 2024 when we harvested the ultra-early rainfed durum in Lethbridge on August 1, which I’ve never experienced unless the crop was a train wreck, and that treatment was the top dog at 72

There’s FAST FAST FAST and There’s when it comes to pre-seed burndown

First case identified in 2021 in Saskatchewan.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Cracks in the foundation of herbicide-resistant kochia control are starting to show. Group 14 herbicide-resistant kochia was confirmed in 2021 from a Saskatchewan sample submitted to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Prairie Resistance Research Lab at Lethbridge, Alta. If Group 14 resistance becomes common on the Prairies, like Group 9 glyphosate resistance has, that foundation will crumble.

“The big concern with Group 14 resistance is that it puts more selection pressure on the remaining Group 6 and 27 modes of action that are applied pre-plant and are still effective on herbicide-resistant kochia,” says Charles Geddes, research scientist at AAFC Lethbridge. “The options going forward will become quite limited.”

The Saskatchewan confirmation was followed up by the confirmation of Group 14-resistant kochia in North Dakota in 2022.

Geddes conducted whole plant bioassay resistance testing on the Saskatchewan sample. Foliar-applied Group 14 saflufenacil at label rates had unacceptable control when measured at 21 days after

GROUP 14 CHEMICAL FAMILIES AND ACTIVE INGREDIENTS

CHEMICAL FAMILY ACTIVE INGREDIENTS FOUND IN

Group 14

Aryl triazone

carfentrazone

Inhibits an enzyme of chlorophyll and heme biosynthesis.

Aim, Authority Strike, Command Charge, Co-op Convex, Co-op Octagon, Emphasis, Conquer, Foremost, Inferno Trio, Instep, Intruvix ll, IPCO Convex, IPCO C-Zone, IPCO Octagon, Maxunitech, Carfentrazone-ethyl 240 EC, Intruvix, Prospect, Revenge, Revenge A, Revenge AE, Revenge B, Revenge Pro, Revenge S, VIKING, Carfentrazone

sulfentrazone Authority, Authority Strike, Authority Supreme, Revenge S

Dicarboximide flumioxazin

Chateau, Fierce, Valtera

Pyrazole pyraflufen-ethyl Blackhawk, Blackhawk EVO, Goldwing, ThunderHawk

Pyrimidinedione saflufenacil

Diphenyl ethers acifluorfen

TOP The Group 14-resistant kochia population exhibited 57- to 87-fold resistance to saflufenacil and 97- to 121-fold resistance to carfentrazone.

Heat, Smoulder, Voraxor, Zidua SC

Hurricane, Ultra Blazer

application. The dose response curve found that the 3X rate still did not provide control and, even at the 10X rate, there was still some kochia biomass present. The resistant population exhibited 57- to 87-fold resistance to saflufenacil and 97- to 121-fold resistance to carfentrazone compared with two susceptible populations.

The Group 14 mode of action includes five different families. Geddes proceeded to test the Saskatchewan sample for cross resistance to these different families. The kochia sample was also resistant to foliar-applied carfentrazone (same chemical family as sulfentrazone). He also found resistance to active ingredients in the dicarboximide (flumioxazin), pyrazole (pyraflufen-ethyl) and pyrimidinedione (saflufenacil) families. The only Group 14 family where cross resistance didn’t occur was with the diphenyl ether chemical family with the active ingredient of acifluorfen.

Defend your wheat fields against the toughest grass and broadleaf weeds and declare victory this season. A single pass of BATALIUM® herbicide combines four active ingredients across three modes of action in one simple, co-formulated product. This versatile herbicide also has a wide application window, so it works when and where you need it, across all soil zones. Put an end to yield losses from grass and broadleaf weeds. Contact your UPL retailer today.

Research points to weed suppression possibilities with winter cereals.

BY JULIENNE ISAACS

Flax is notoriously uncompetitive. It has a slower growth habit, a shorter stature and less branching than other crops, and thus has a tougher time competing with weeds, particularly wild oats and cleavers, says Dilshan Benaragama, an assistant professor and the crop protection chair at University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences.

Producers currently have limited in-crop herbicide options. Group 1, Group 4 and Group 6 herbicides are widely used in Canada to control weeds in flax, says Benaragama, but herbicide resistance is on the rise for Group 1 and Group 2 herbicides.“Herbicide resistance is a challenge for many crops, but this can be greater for a less competitive crop like flax,” he adds.

Benaragama and his co-authors write in a new research study that looks at diverse flax-based rotations to improve weed control that restrict weed emergence, reduce weed growth and reproduction and reduce the build-up of weed seedbanks. Benaragama completed the research as a postdoctoral researcher with Christian Willenborg, department head and associate professor in the University of Saskatchewan’s Department of Plant Sciences, who served as principal investigator on the project.

It’s important to combine short-term and long-term weed management strategies, the study’s authors continue. Short-term strategies can include the use of more competitive varieties, narrower row spacing and increasing crop density. Long-term strategies can involve diversifying herbicide modes of action to slow the development of resistance and increasing rotational crop diversity to put stress on weed populations.One global meta-analysis found that moving away from simple rotations and increasing rotational diversity reduced weed density by 49 per cent, the research study notes.

The Flax Council of Canada currently recommends a one-in-four rotation for oilseed flax to minimize disease risk. Common rotation crops for flax in Manitoba include cereals, pulses, peas and canola.

When they set out to design the study, Benaragama and his colleagues were not simply interested in adding more crop diversity to flax rotations. They wanted to find a way to capture the functional benefits of certain cropping choices to better manage weeds. “When I say diversity, we want to look at the functional diversity – not just rotating crops like flax with cereal/pulse crops. We wanted to understand how functional differences, such as time of seeding, time of harvesting and different types of harvesting methods can help manage weeds,” he says.

Benaragama’s (and others’) previous research has shown one of the best methods for reducing weed pressure in many field crops is introducing a three-year alfalfa rotation. “This works particularly well to manage wild oats,” he says. But not many farmers are likely to go for it.

“Not all farmers would want to have this long of a rotation if they’re grain farmers. Alfalfa cut for silage is useful for livestock farmers, but may not be attractive for grain farmers,” he says.

As a workaround for this problem, Benaragama and Willenborg decided to ask whether they could capture the functional benefit of alfalfa in the rotation with different crop species but with similar functionality for

managing weeds.

“The functionality of alfalfa is that it’s in the soil all year and is already established in the spring to outcompete weeds,” says Benaragama. “That’s one functionality. It can also control weeds when we cut for forage or do the mowing. So, what you’re going to do is to bring that functionality, cutting for forage, via different crops.” This is critical in controlling weed seed banks, particularly if herbicide resistance has developed.

The researchers set up an experiment with 17 different cropping combinations with flax, including a variety of field crops, winter cereals and forages, including alfalfa, winter wheat, winter triticale, forage oat, barley, peas and canola. Eight rotations were under a standard herbicide system, with in-crop herbicides applied in all phases but the first-year flax phase. The same eight combinations were also included in a reduced herbicide system for comparison. The final combination was flax followed by three years of alfalfa – the most functionally diverse system.

It’s been previously shown that alfalfa works really well to control wild oats, says Benaragama; when it’s cut for forage, wild oat heads bearing seeds are also cut, which reduces the weed seed returning to the seed bank.

In this study, the researchers found the same benefit applied to cleavers. That said, an effective alternative to alfalfa with similar functional diversity was a bit of a surprise: Flax followed by two consecutive years of winter cereals had a similar effect on weeds.

The reason it’s effective? Winter cereals in rotation with summer crops break the lifecycle of summer annual weeds by adding diverse planting and harvesting dates to the rotation. But, in this study, just one year of a winter cereal didn’t improve control of wild oats or cleavers. In the study’s Carman, Man. site, where the researchers saw good overwintering, two consecutive years “did show a lot of promise.”

Benaragama says he’d be “very cautious” in recommending this approach to producers. “Growing winter cereals back-to-back is tricky, but depending on the situation, if they are dealing with weed issues [and] if they don’t want to go with three years of alfalfa, two consecutive years of winter wheat could be helpful,” he says.

Bringing functional diversity to flax-based rotations can be challenging, he adds. It means bringing in different types of crops that require different management strategies.It also takes time to show results. It takes time to notice the benefits of an overall reduction in weed populations – more than a single growing season and depending on the producer’s cocktail of shortterm and long-term weed control approaches, perhaps several years.

24_014611_Top_Crop_Western_MAR2_CN Mod: December 27, 2024 2:01 PM Print: 01/06/25 page 1 v2.5

Having a good flax crop with good stand density, remains the first priority for battling weeds. “These two things have to go hand-in-hand,” Benaragama says, “a good rotation, but also a good crop within the rotation.”

The looming issue of Group 14 kochia resistance | CONTINUED FROM PAGE 20

Soil-applied pre-plant

(Group 3)

Triallate/Trifluralina (Group 15/3)

Trifluralin + metribuzina (Group 3 + 5)

Pyroxasulfone (Group 15)

Bromoxynilc (Group 6)

Bromoxynil + topramezone (Group 6 + 27)

Bromoxynil + pyrasulfotolec (Group 6 + 27)

(Group 6)

(Group 6)

(Group 6)

(Group 10)

Topramezone (Group 27)

Bromoxynil + tolpyralate (Group 6 + 27) C

Bromoxynil + pyrasulfotole (Group 6 + 27)

(Group 15)

(Group 27)

(Group 27)

CHART KEY

a: Pre-plant incorporated.

b: Yellow mustard only.

c: Mixed with glyphosate only.

d: Glufosinateresistant varieties only.

e: Applied with tank-mix partner.

C = Control

S = Suppression

“The diphenyl ether chemical family is not used to a large degree on the Prairies, and is only registered on soybean,” says Geddes.

Geddes subsequently went back into his kochia samples collected in weed surveys across the Prairies between 2018 and 2021. Of the 882 kochia samples tested, none had Group 14 resistance. “Those findings show that the first Group 14-resistant kochia from Saskatchewan was found early and it isn’t widespread,” says Geddes.

Geddes says, though, that farmers and agronomists shouldn’t be complacent. He cites the example of how quickly Group 9 glyphosate resistance expanded across the Prairies. In Alberta, that biotype expanded from four per cent to 78 per cent of surveyed samples in 10 years. “I don’t have any reason to believe Group 14 resistance won’t spread at the same rate,” he says. “Time will tell.”

The other ‘good’ news is that while the Group 14 sample was also resistant to Group 2 and 9, it wasn’t resistant to the Group 4 synthetic auxins that include

dicamba and fluroxypyr. Still, if Group 2, 4, 9 + 14 resistance developed, few herbicide options would be left. Another concern regarding Group 14 herbicide-resistant kochia is the impact on pre-seed weed control. Should the Group 14 biotype become widespread, with few herbicide options, farmers may have to resort to pre-seed tillage. This is compounded by the widespread glyphosate-resistant kochia across the Prairies, with glyphosate being relied on for so many years to replace pre-seed tillage. “My big concern is what may happen to no-till. There could be a shift in tillage systems in the absence of new alternatives for pre-plant weed control,” says Geddes.

As much as integrated weed management (IWM) is an often-used term and, perhaps seldom utilized, IWM is important to kochia weed control. These practices include early weed control when kochia seedlings are small, a diverse crop rotation with competitive crops and alternative weed control practices to control patches and escapes such as mowing, hand-pulling or tillage to remove plants before they set seed.

by Bruce Barker, P.Ag | CanadianAgronomist.ca

Fusarium head blight (FHB) is one of the most damaging diseases on hard red spring wheat on the Prairies. A research study led by the University of Manitoba looked into how weather, variety, fungicide application at anthesis to control FHB, as well as pre-harvest glyphosate application affected wheat grain quality.

Research plots were established at four locations at Lethbridge, Alta., Indian Head, Sask. and Carberry and St. Adolphe, Man. in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Carberry 2015 and St. Adolphe 2016 were not harvested due to production issues, leaving 10 site-years of data. Target seeding rate was 30 seeds/ft2 (300 seeds/m2).

Glenn (I), Carberry (MR), Cardale (MR), CDC Stanley (MS), Stettler (S) and Harvest (S) were the Canadian Western Red Spring (CWRS) wheat varieties grown at each site. Fusarium resistance ratings for these varieties are moderately resistant (MR), intermediate (I), moderately susceptible (MS) and susceptible (S). Note that the classification for Harvest was revised by the Canadian Grain Commission to Canada Northern Hard Red (CNHR) after the study had been conducted.

In addition to a control with no pesticide application, there were three pesticide treatments that were applied to each wheat variety: Prosaro (prothioconazole/tebuconazole) fungicide applied at anthesis; Roundup WeatherMax with Transorb (glyphosate) herbicide applied at pre-harvest; and a treatment with both fungicide and herbicide.

The fungicide was applied according to label directions when at least 75 per cent of the wheat heads on the main stem were fully emerged up to when 50 per cent of the heads on the main stem were in flower. Glyphosate was applied when wheat grain moisture content was ≤30 per cent at about seven to 14 days before harvest.

The grading factors analysed included test weight (TW), damage caused by ergot, sawfly midge, sprouting, as well as Fusarium damaged kernels (FDK). Grain protein and thousand kernel weight (TKW) were also calculated. For the CWRS Fusarium grading factor, No. 1 CWRS is allowed 0.3 per cent FDK, No. 2 is 0.8 per cent, No. 3 at 1.5 per cent and CW Feed at 4.0 per cent.

Over the three years, diverse weather variations provided a wide range of weather conditions across the sites, and the most variable factors were precipitation

and water deficit/surplus. The 2016 growing season generally had higher rainfall.

For the warmer and drier years in 2015 and 2017, wheat had higher grades, test weight, TFK and grain protein content but lower FDK. In 2016, the wetter conditions resulted in higher FDK with lower wheat grades compared to 2015 and 2017. For example, Indian Head 2016 had 1.73 per cent FDK, which would have graded CW Feed, compared to Indian Head 2017 at 0.001 per cent FDK (No. 1 CWRS grade).

Weather was the major factor affecting grain quality, contributing 39 per cent to 77 per cent of total variance in grading and quality factors. Rainfall variation was the main weather factor affecting quality and was greater than the effect of air temperature. Generally, FHB is influenced by higher levels of rainfall, warm and humid weather during flowering and optimal temperatures of 25 to 28 C.

Variety had a significant impact on grain quality, as would be expected, and contributed one to 20 per cent of total variance in FDK levels. The FDK levels generally lined up with the FHB resistant ratings. Stettler and Harvest, both susceptible varieties, were the most affected by FHB. Stettler had significantly similar FDK levels as Harvest and Carberry, but higher than Cardale, Glenn and CDC Stanley, when averaged across site-years and pesticide treatments.

Fungicide application significantly reduced FDK level in the four of five site-years that were conducive to FHB. At the other five site-years where FHB pressure was low, there was no impact from fungicide application on FDK. Pre-harvest glyphosate application did not affect FDK content.

Overall, the study found that rainfall variation was the main factor that contributed to variation in FHB, as indicated by FDK levels. Glyphosate had no adverse effect on grain quality. Fungicide application in accordance with label directions can significantly reduce FDK percentage when weather conditions – high rainfall, humidity and temperature – are conducive to disease development.

Bruce Barker divides his time between CanadianAgronomist.ca and as Western Field Editor for TopCropManager. CanadianAgronomist.ca translates research into agronomic knowledge that agronomists and farmers can use to grow better crops. Read the full research insight at CanadianAgronomist.ca.

“Stronger and faster? Shut the front door!”

The speed and performance of new Intruvix™ II herbicide is so darn good, folks can hardly contain their excitement. By applying it with glyphosate before planting cereals, they’re saying goodbye and good riddance to narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, volunteer canola, kochia and many other problem weeds. Enjoy cleaner fields, faster, while protecting your future glyphosate use. Cheese and crackers, how easy can you get?

Clean is good