POTASH FERTILIZER

Improving crop resilience, yield and disease resistance. PG. 6

FHB IN CEREAL CROPS

Investigating fungicide timing and crop management options. PG. 16

TAMING WILD OATS

Wild oat management in tame oats. PG. 24

Improving crop resilience, yield and disease resistance. PG. 6

Investigating fungicide timing and crop management options. PG. 16

Wild oat management in tame oats. PG. 24

There’s more behind every bag of InVigor® hybrid canola.

• Comprehensive portfolio of high-yielding canola hybrids

• Patented Pod Shatter Reduction technology

• Complete crop protection portfolio, including Cotegra® fungicide

• Support programs to help get your crop off to the right start

Visit agsolutions.ca/InVigor to learn more.

6 | Potash fertilizer use in Prairie dry regions

Improving crop resilience, yield and disease resistance in Brown soil zone

By Donna Fleury

4 Kudos to Canadian wheat growers

16 | Lessening the impact of FHB in cereals

Investigating fungicide timing and other crop management options to address FHB

By Donna Fleury

Investigating weed control in faba bean

Bruce Barker

Enhanced efficiency fertilizers cut nitrous oxide emissions in spring wheat By Bruce Barker

Lentil seeding rate and fungicide interactions

24 | Taming the wild ones

Wild oat management in tame oats. By Bruce Barker

26 Lentil fertility research finds variable responses By Bruce Barker

AAFC FARM INCOME FORECASTS FOR 2023 AND 2024 NOW AVAILABLE

The agriculture sector continued to show very strong overall economic performance in 2023, despite numerous challenges, including droughts in Western Canada and other extreme weather events, Russia’s continuing war on Ukraine and other global conflicts.

DEREK CLOUTHIER EDITOR

Iwas reading a release the other day from Cereals Canada about its annual New Crop Trade and Technical Missions initiative, and what jumped off the page was how well-respected our wheat is around the world.

Quoting what they heard from purchasers of Canadian wheat, the release says customers refer to Canadian Western Red Spring as the “gold standard” of wheat and an anchor in their wheat blends. It also says Canadian Western Amber Durum has been called the “Ferrari” of durum wheat.

This is high praise indeed for Western Canada’s largest crop, of which we export approximately 75 per cent around the world to countries such as China, Japan, Indonesia, Italy and the U.S.

What better way to lead into our latest issue of Top Crop Manager West, which focuses on cereals like Canada’s highly respected wheat crop, than to shine a light on our exemplary wheat growers?

Included in this issue is a feature looking at how to best manage Fusarium head blight to help lessen the impact of the fungal disease on cereal crops, as well as a dive into a widespread weed that impacts the Prairies, costing approximately half a billion dollars in annual losses each year – wild oats. Staying on the Prairies, we also explore the impact of potash fertilizer on crops like durum wheat in drier regions in Brown soil zone areas.

And, always timely with his Agronomy Update, western field editor Bruce Barker addresses how enhanced efficiency fertilizers can cut nitrous oxide emissions in spring wheat, which could help Canada reach its goal of reducing the amount of greenhouse gasses from nitrogen fertilizers by 30 per cent below 2020 levels by 2030.

As is the goal with each issue of Top Crop Manager West, we aim to provide the latest insight and research to help our audience produce the best product they can. And given the kind words from customers of Canadian wheat voiced around the globe, it’s clear growers in Western Canada are stepping up to the plate and hitting a home run.

Challenges will always remain. The latest wheat market outlook indicates that although weekly exports are strong and running eight per cent ahead of last year’s numbers, durum wheat exports are lagging, mostly due to competition from other wheat-producing countries like Turkey filling some of that global need.

But, when you’re selling a product that’s considered “the gold standard,” you won’t be down for long.

Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, May/June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – Canada 1 Yr $49.47; 2 Yr $79.05 (Canadian prices do not include applicable tax) USA 1 Yr $112.20 CDN; Foreign 1 Yr $134.13 CDN Top Crop Manager East – 5 issues Feb/Mar, Apr/May, May/Jun, Sep/Oct, Nov/Dec Canada 1 Yr $49.47; 2 Yr $79.05 (Canadian prices do not include applicable tax) USA 1 Yr $112.20 CDN; Foreign 1 Yr

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office

privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com

topcropmanager.com

They say lightning never strikes the same place twice. Seeing new Authority Strike™ herbicide in action in wheat, peas, flax and mustard shows otherwise. One application delivers a powerful one-pass burnoff now and extended control later – in exactly the same field. With two kinds of Group 14 action, Authority Strike™ herbicide lights up kochia, lamb’s-quarters, pigweed, Russian thistle*, wild buckwheat, waterhemp and more. WHEAT | FIELD PEAS | FLAX | CHICKPEAS | MUSTARD | SOYBEANS

Put a charge, two actually, in your pre-seed weed control. *Suppression

Improving crop resilience, yield and disease resistance in chickpea, mustard and durum in the Brown soil zone.

by Donna Fleury

Crops such as durum wheat, mustard and chickpeas are commonly grown in the Brown soil zone areas. Although potash fertilizer has been shown to improve plant resistance to stresses such as diseases, drought and cold, and help optimize yields for crops such as barley and wheat, little information is available about the potential of potash fertilizer in these drier region crops. Researchers in Saskatchewan have a project underway to learn more.

“We are investigating the response of crops normally grown in the drier region of the Prairies to the addition of starter potassium chloride (KCl) on yield and disease incidence,” says Jeff Schoenau, professor of Soil Science and Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture chair in soil nutrient management, Department of Soil Science at the University of Saskatchewan (USask). “In this project, we are examining the extent to which potash fertilizer applied at seeding may benefit durum wheat, chickpea and mustard yield. We are also exploring how this fertilizer impacts crop health by supplying ample soil K and Cl, which are important in early nutrition, standability, drought tolerance and disease resistance. Along with field trials, we also have controlled environment studies with the same crops.”

Schoenau is leading the project in collaboration with graduate student Tristan Chambers and research associate Ryan Hangs, as well as Michelle Hubbard, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), and Randy Kutcher, professor in the Department of Plant Science at USask.

Field trials were conducted in southern Saskatchewan over two crop seasons in 2022 and 2023. Three crops – durum, mustard and chickpea – were grown in both field trials and under controlled environment conditions on two soils: a sandier soil of Chaplin association and a second slightly heavier silty loam textured Swinton association soil. The project also compared the response to KCl at two landscape positions in farm fields in south-central Saskatchewan: a higher slope (knoll) position and a lower slope (depression). A starter application of potash was applied by side-banding at seeding at a single rate of 40 kg/ha of 0-0-60. In 2024, spring wheat will be seeded across the two field trial sites to evaluate whether there are any residual effects from the potash application.

“We included two different slope locations to better understand how crops respond at different landscape positions,” explains Schoenau. “The landscape dependency and interaction of soil and environmental conditions on crop response become important when considering site-specific precision fertilizer program recommendations. The

With new OnDeck™ herbicide, you can finally have it both ways. Control kochia with a unique combination of actives, and re-crop without any restrictions. For a high yielding harvest, today and tomorrow, maximize every acre with the proactive power of OnDeck™.

knolls tend to be drier, higher pH and often sandier soils. The lower depressional areas tend to be the wetter part of the landscape, with lower pH, soils that are more highly leached and potentially more susceptible to disease. From past research, we know these can be the most deficient parts of the field where chloride, which is highly mobile in the soil with water, may be leached below the root zone in spring as a result of the accumulation of snowmelt runoff in the low spots.”

During the two field seasons of the study, the conditions in southern Saskatchewan were very dry. Schoenau notes that the precipitation, particularly in June and July, was well below normal.

“The conditions were an extension of three years of drought that really started in 2021. These dry conditions very much muted the treatment responses in the field trials. In terms of yields of the three crops, the results showed no significant response to the addition of the starter potash in either slope position. However, in 2023 there was a trend of a positive response in durum to the potash treatment in the upper slope position. We could visually see the response at mid-season, however, the final grain yield results were not statistically significant. The drier study conditions also meant there was little in the way of either root or foliar diseases. Although root rot incidence was very low in general, one trial did show a small but statistically significant reduction in root rot in chickpea with potash grown on the upper slope or knoll landscape position.”

The uptake of KCl by the crops and yield were also evaluated in the study. The available soil supply of potassium and chloride was quite high in these sites at the start of the project. The results showed that the lower slope sites not only outyielded the drier upslope sites but also had a much greater uptake of potassium and chloride in

the plant materials. Much of the potassium those crops took up and especially the chloride remains behind in the straw. Therefore, if the straw was removed out of those fields along with the grain, the export or removal of potassium and chloride through harvest is much greater. This is something that needs to be taken into consideration in managing potassium and chloride fertility over several years if straw is being removed from the field along with the grain. Also, under typically wet spring conditions with a lot of snowmelt runoff, chloride can potentially be leached out of the soil profile because it is mobile. However, under the dry study conditions, the results did not show any evidence of that.

“Our study also included similar controlled environment trials including all three crops and soils with a range of clay contents from southern Saskatchewan,” explains Schoenau. “For the controlled environment, the objective was to evaluate the early-season response to the starter potash application by measuring the shoot biomass produced after one month of growth. The trials also included applications of potash, monoammonium phosphate and copper sulfate alone and in combination, along with a no-fertilizer check. The results showed there can be an impact of early nutrition, with some trials showing a significant positive yield response in the first month of growth. For mustard grown on the sandy soil, there was a significant positive response to fertilization, with higher early-season biomass yields for the fertilizers alone and in the combinations. This is consistent with what we might expect with a sandier textured soil. Similar to the field trials, there were no significant incidences of either root or leaf diseases in the controlled experiments.”

Schoenau adds, that one interesting observation in the controlled environment experiments was the appearance of the emerging chick-

pea health issue that has been showing up in some chickpea fields in southern Saskatchewan over the past three or four years.

Schoenau is part of a team led by Michelle Hubbard at AAFC to try and determine the cause of the issue, whether it is disease, fertility, herbicide injury or some other factors. Symptoms observed were bleaching and chlorosis extending from the leaf tips and necrosis and wilting, primarily of the mid-toupper branches and leaflets; however, symptoms are variable, and so far, no specific cause has been identified.

“Fertilizer alone won’t solve disease problems; however, a well-nourished crop with good nutrition is generally better able to fend off diseases.”

“In our controlled environment trials, the symptoms occurred across all of the chickpea treatments, including fertilized treatments and the unfertilized control,” says Schoenau. “Therefore, the issue does not seem to be related to a lack of fertility in the nutrients tested, although we still don’t know the cause. Hopefully, the continued research efforts will help solve this puzzle.”

As part of nutrient management planning, a soil assessment is the first good indicator of whether there is the potential for a response to potash. Although not the case in this study, if fields show low supplies of available potassium and low chloride, then a potash application could be considered. Sandier textured soils can also be more prone to lower supplies of nutrients.

It’s also important to be aware of environmental conditions, such as in a spring with a lot of runoff water from snowmelt or rainfall resulting in water leaching through the soil profile. This can result in reduced chloride levels. Because chloride is also a mobile nutrient

element, it is a good strategy to soil test to a 60-cm depth.

“Although our field study was conducted in some very dry conditions over the two years, drier than normal even for southern Saskatchewan, we did learn about crop responses under those conditions,” says Schoenau. “We did see a trend in the one year for a positive early-season response with the durum crop to the potash application in the field on the upper slope position. It will also be interesting to see if there are any residual effects in the following spring wheat crop in 2024. Although the dry study conditions limited the development of root or foliar diseases in the field, good nutrition overall can help a crop be more resilient.

23_011333_Top_Crop_Western_Edition_MAR_CN Mod: December 18, 2023 3:57 PM Print: 01/16/24 page 1 v2.5

“Fertilizer alone won’t solve disease problems; however, a wellnourished crop with good nutrition is generally better able to fend off diseases. Crops such as chickpea, mustard and durum grown in the drier regions of the Prairies could see crop health and yield benefits from a starter potash fertilizer application, depending on soil nutrient availability and environmental conditions.”

Research developed a greater understanding of weed in faba bean.

by Bruce Barker

As faba bean acreage started to expand in Saskatchewan, a better understanding of how weeds can best be managed was a focal point of research at the University of Saskatchewan’s Plant Science Department. From 2016 to 2021, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers funded 13 faba bean weed control research projects at professor Chris Willenborg’s lab.

One of the first studies developed an understanding of the critical period of weed control (CPWC). This is defined as the period in crop growth when weeds must be controlled to prevent yield loss. Research took place at the Kernen Research Farm near Saskatoon, Sask., and the Western Applied Research Corp (WARC) located at Scott, Sask., from 2018 through 2021.

Twelve different weed removal timings were compared as well as a weed-free control and a weed-infested control. CDC Snowdrop was seeded into plots that had been treated with a glyphosate + bromoxynil or carfentrazone pre-seed application.

• The CPWC was found to be from the five to nine-node (three to seven leaf) growth stages. This means that the crop must be

kept weed-free until the seven-leaf stage.

• Additionally, applying a pre-emerge residual herbicide can also reduce early-season weed competition.

Willenborg conducted six studies that investigated tolerance to various pre- and post-emergent herbicides. In one study, he found faba bean tolerance to pyridate, a Group 6 herbicide sold under the tradename Tough 600EC, was unacceptable when applied at the two to three-node stage.

• Pyridate at all rates tested caused significant yield losses of 17 to 36 per cent.

Another study looked at tolerance to pre-seed herbicides from 2016 and 2017 at Kernen and at Goodale Research Farm and Kernen in 2018 through 2020. Products were applied at 1x and 2x rates, and

ABOVE: Thirteen research studies looked at expanding faba bean weed control options.

included pyroxasulfone (Zidua), sulfentrazone (Authority), pyroxasulfone plus carfentrazone (Focus), pyroxasulfone plus sulfentrazone (Authority Supreme), pyroxasulfone plus saflufenacil (Zidua + Heat), flumioxazin (Valtera), pyroxasulfone plus flumioxazin (Fierce) and saflufenacil (Heat).

Overall, most of the herbicides did not impact crop establishment, development or yield, but there were some exceptions. In 2018, there was some initial injury from the application of Zidua + Heat, Valtera (2X rate) and Zidua + Valtera when applied pre-emergence on the sandier soils at Goodale, but no injury was observed for any products in 2019.

In 2020 at both Goodale and Kernen, Focus caused greater than 10 per cent injury for faba bean at 1x and 2x alone or when tank mixed with Valtera at pre-plant or pre-emergence. At the 2x rate, pre-plant Focus significantly reduced faba bean seed yield by 11 per cent at Kernen and by 13 per cent at Goodale compared to the handweeded untreated check.

• These results suggest that Focus may not be a good fit as a preemerge herbicide for faba bean production, particularly under low organic matter, sandy soils.

Nine post-emergent herbicides were evaluated at Kernen in 2016 and 2017 and were applied at the four-leaf stage at 1x and 2x rates. Products screened included topramezone (Armezon), bentazon (Basagran), fomesafen (Reflex), Armezon + Basagran, cloransulammethyl, cloransulam-methyl plus bentazon, Reflex + Basagran, fluthicacet-methyl (Cadet) and fluthiacet-methyl plus Basagran. Basagran is the only registered post-emergent product on faba bean.

• Based on the overall results of this trial, none of the unregistered products would be considered new options for post-emergent weed control in faba bean.

A tolerance screening trial to layering pre- and post-emerge herbicides was conducted in 2017 and 2018 at Scott, Kernen and the Northeast Agriculture Research Foundation at Melfort.

Six pre-emergent herbicide treatments, including pyroxasulfone (Zidua), ethafluralin (Edge), saflufenacil (Heat), flumioxazin (Valtera), pyroxasulfone + sulfentrazone (Authority Supreme) and pyroxasulfone + saflufenacil (Zidua and Heat) were applied on their own. In addition, these pre-emergent herbicides were also applied in a layered combination with imazamox/bentazon (Viper) and imazamox/imazethapyr/sethoxydim (Odyssey). Viper and Odyssey were also each applied with no pre-emergent application.

• Pre-emergent application provided significant reductions in broadleaf weed densities before the post-emergent application.

• Depending on the weed spectrum, the combined pre- plus post-emerge application did not always result in higher yields than post-emerge herbicides applied alone.

“We believe that growers have to consider the long-term economic benefits of this layering strategy in terms of delaying herbicide resistance rather than just short-term economic returns,” says Willenborg.

Willenborg also ran three recropping trials looking at the impacts of residual herbicide carryover on faba bean production. In the first trial, clopyralid (Lontrel), quinclorac (Accord), flucarbazone-sodium (Everest), pyrasulfotole + bromoxynil (Infinity), dicamba (Banvel II) and metsulfuron-methyl (Ally) were applied at different rates to spring wheat the previous year in 2016 at Kernen and Scott. Post-harvest 2,4,D was also applied as a treatment following wheat harvest. The trial was repeated in 2017 at Melfort, Scott and Kernen.

Across the three years, faba bean injury from herbicide residues was inconsistent. Most herbicides caused some herbicide injury initially under the right environmental conditions.

• Accord and Lontrel residues at higher rates are more likely to cause damage to faba bean and to reduce yield, especially under dry, low pH and low soil organic matter soil conditions.

• Growers should avoid growing faba bean on fields where these two Group 4 products have been applied the previous year.

A second recropping study looked at variety tolerance to residual herbicides. Lontrel (300 g ai/ha), Accord (200 g ai/ha), Everest (40 g ai/ha) and Ally (9 g ai/ha) were fall-applied at 2x rate to chemfallow in 2016 and 2017 at Kernen. Three low tannin varieties, CDC Snowdrop, Snowbird, and Tabasco and three tannin varieties, CDC SSNS-1, Malik and Taboar were grown on the herbicide-treated land the following spring in 2017 and 2018.

• There were no differences between faba bean varieties in crop establishment, biomass or yield for the herbicides assessed.

• Lontrel produced high crop injury and yield loss.

• Everest residues resulted in higher levels of crop injury than both Accord and Infinity.

A third residue study looked at faba bean tolerance to Group 2 and Group 4 herbicide residue in comparison to field pea tolerance was conducted at Kernen in 2017. The intent was to see if field pea recropping restrictions could also be applied to faba bean. CDC

Snowdrop faba bean and CDC Meadow field pea were grown on plots that had increasing rates of Lontrel and Everest applied the previous year.

• Injury to both crops was much greater from Lontrel than Everest.

• The response of field pea and faba bean to Everest was similar.

• Faba bean was more sensitive to Lontrel residues than was field pea.

“...growers have to consider the long-term economic benefits of this layering strategy in terms of delaying herbicide resistance...”

Field studies were conducted at the Kernen in 2017, 2018 and 2019 and Melfort in 2019. The study was done to see if higher seeding rates along with pre-emerge herbicides could reduce the need for a postemerge herbicide application.

Seeding rate was 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5 and 15 seeds per square foot (25, 50, 75, 100, 125 and 150 seeds/m2). Herbicide applications compared were glyphosate alone pre-seed, glyphosate with Authority Supreme (PRE), and glyphosate with Authority Supreme followed by Viper ADV post-emergent (PRE+POST).

• Layering glyphosate with Authority Supreme followed by Viper ADV post-emergent generally provided the best weed control and yield at all seeding rates.

• A seeding rate of five seeds/ft2 is recommended based on this study, but if glyphosate was the only burn-down herbicide applied, a seeding rate of 12.5 seeds/ft2 was needed to optimize yield.

Another integrated weed management study investigated seeding date, seeding rate, row spacing, and mechanical weed control combined with pre-emerge herbicides with differing lengths of residual control. The study was conducted at Kernen from 2017 through 2019.

Three levels of IWM were compared. The low IWM level was late seeding (May 30 to June 7), wide row spacing of 23 inches (60 cm), regular seeding rate of 4.5 plants/ft2 (45 seeds/m2), and no mechanical rotary hoeing weed control. Medium IWM included an average seeding date (May 18–24), 12-inch (30 cm) row spacing, regular seeding rate of 4.5 plants/ft2 (45 seeds/m2) and no rotary hoeing. High IWM included early seeding (May 5–10), 12-inch row spacing, high seeding rate of 9.5 plant/ft2 (95 seeds/m2) and mechanical rotary hoeing.

The four PRE residual herbicide treatments consisted of glyphosate alone or tank-mixed with a short residual herbicide, Heat (saflufenacil), moderate residual, Valtera herbicide (flumioxazin) and season-long residual Authority Supreme (sulfentrazone + pyroxasulfone).

• The results of this study showed that all three of the soil residual herbicides improved weed control.

• Additionally, by increasing from low to medium intensities of IWM, significant improvements to both weed control and crop yields were observed.

A trial conducted at Kernen and Melfort from 2017 through 2020 assessed whether a residual pre-emerge application allows for a broader application timing window for post-emerge herbicide application. Pre-emerge herbicide treatments included a glyphosate tank-mix

with either Aim (carfentrazone), Heat or Valtera. Aim has no residual, while Heat and Valtera provide some residual control of some broadleaf weeds. Post-emergent applications included Odyssey or Viper at either the two or six-leaf stage (four and eight node stages).

• Heat and Valtera applications had lower weed biomass than Aim.

• There was no difference in weed biomass between the two and six-leaf stages.

• Layering pre- and post-emerge herbicides increased crop biomass but not yield.

Research was conducted to determine the best timing and herbicide treatments on dry down and faba bean yield. The study was carried out at Kernen in 2018 and 2019 and Scott from 2018 through 2020. Herbicide applications included glyphosate, Heat (saflufenacil) and glyphosate + Heat at application timings of 60, 50, 40, 30 and 20 per cent seed moisture content. Visual ratings were conducted at seven, 14 and 21 days after treatment.

• All three herbicide treatments were found to have similar drydown rates.

• Application of harvest aid herbicides at 20 per cent moisture level had a 17 per cent greater dry-down rate compared with the application at the 60 per cent moisture level.

• There was no herbicide effect on green and black seed percentage.

• If perennial weeds are present, an application with glyphosate is recommended.

Additional research was conducted to see if there were variety interactions with desiccants between low-tannin and tannin cultivars. Three low-tannin varieties (CDC Snowdrop, Snowbird and Tabasco) and three tannin varieties were compared (CDC SSNS-1, Malik and Taboar). Malik, CDC Snowdrop and Snowbird are considered early maturing (104 days) and CDC SSNS-1, Tabasco and Taboar as late maturing (105–107 days).

Five different herbicide treatments compared were untreated, glyphosate, Heat, Reglone (diquat) and Liberty (glufosinate), and were applied when bottom pods were black at approximately 30 per cent seed moisture. Liberty is not registered for preharvest application.

• Dry-down herbicides produced no significant differences in crop yield, thousand seed weight, plant counts, black pod percentage or straw moisture content compared to the untreated check.

Reglone and Liberty consistently provided better crop dry-down than the untreated check in the late-maturing cultivars.

When tried is no longer true… it’s time for something new.

It’s time for Talinor ™ . A unique active ingredient lets you take back control from resistant broadleaf weeds in your cereal fields. The powerful, fast-acting performance you get from Talinor will have you seeing results just days after spraying; giving you the confidence to look forward to what’s next. It’s not just about weed control, it’s about the future of your farm.

To learn more about Talinor, visit Syngenta.ca, speak to your local Syngenta representative or contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682).

Always read and follow label directions. Talinor™, the Alliance Frame, the Purpose Icon and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. © 2024 Syngenta.

Investigating fungicide timing and other crop management options to address FHB.

By Donna Fleury

In many areas across the Prairies, Fusarium head blight (FHB), caused by Fusarium graminearum, has resulted in widespread outbreaks in some years, resulting in yield and grade losses and deoxynivalenol (DON) contamination. Growers have some management strategies available; however, current solutions related to resistance, rotation and fungicides provide suppression at best. Researchers continue to investigate potential crop management strategies to lessen the impact of FHB in cereals.

“We initiated two companion studies in 2018 to investigate cropping strategies that could reduce the amount of inoculum and reduce the extent of host infection in both wheat and barley,” explains Kelly Turkington, plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and project lead. “For FHB management, the recommendation for producers over the last several years has been to use an integrated approach of applying fungicides, selecting varieties with resistance and following good rotations. However, even producers using those three strategies, particularly in northeastern

“We studied barley and wheat in separate studies, and although we thought there might be some differences in FHB management, we observed similar results in both crops.”

Saskatchewan in high FHB years such as 2010, 2012 or 2016, were still significantly impacted by FHB. For many fields, the levels of Fusarium damaged kernels (FDK) lowered grades from CW#1 to #2 or #3 for wheat, and DON levels were often above the desirable level of about one ppm, depending on the wheat and barley end-use markets. Therefore, we wanted to investigate whether there were options to tweak fungicide application timing and other strategies that might help growers reduce FHB infection and crop losses.”

The objectives of the studies were to determine if row spacing (wheat only), water volumes (barley only), seeding rates and fungicide timing and their potential interactions affect FHB development, leaf disease and crop productivity in wheat and barley.

For both the wheat and barley studies, trials were conducted at seven sites across Canada, including Lacombe (barley only) and Lethbridge, Alta.; Scott, Indian Head and Melfort, Sask.; Brandon, Man.; Normandin, Que.; and Charlottetown, P.E.I. Barley trials were conducted in 2018, 2019 and 2021, and wheat trials were extended into 2022. No trials were conducted in 2020 due to COVID-19 impacts.

Water volumes included 20, 40 and 60 L/ac., and seeding rates of 200 and 400 seeds/m2 were compared. The fungicide trials compared Prosaro XTR fungicide applied singly just after head emergence at approximately one to two (barley) or three to four (wheat) days following full head emergence, or seven to 10 days later, or on both dates, plus a control with no fungicide application. Growers should note that these are research trials only, and some fungicide applications included are not currently registered on the label for commercial application. Producers must always follow currently registered products

and label recommendations.

“We selected sites across Canada to be able to compare results from sites with higher levels of FHB and those such as Lacombe, where FHB is typically not a big problem,” says Turkington. “At many sites, the drought and weather conditions were not favourable for disease development, and although there wasn’t much FHB or DON at some of the sites, there was a lot of leaf disease. At all of the sites, we assessed FHB development as well as leaf disease, yield, thousand kernel weights and malting quality for barley. FHB is a very difficult disease to manage, with infection, FDK and DON levels all reflected by the disease triangle that requires three factors: the interaction of a susceptible host, a virulent pathogen and an environment favourable for disease development. These factors impact the main risk period for the crops.”

For FHB infection, the growth stage of the host is critical. Infection of the cereal head can occur anytime from head emer-

gence to the start of senescence. Fungicide applications must be applied directly to the head tissue for protection. Therefore, if the fungicide application is made too early before all of the heads have emerged from the boot, some heads can be missed and become infected because the fungicide did not protect them. This makes managing FHB much more difficult and is why the level of control or efficacy when using a fungicide for FHB may not be as high compared to the expected efficacy for leaf disease fungicide applications.

“We studied barley and wheat in separate studies, and although we thought there might be some differences in FHB management, we observed similar results in both crops,” notes Turkington. “The results suggest that later single applications of fungicide and perhaps even dual post-head emergence applications may need to be considered to provide a more consistent and effective reduction in FDK and DON levels when FHB risk in cereals is higher. The dual timing tended to more consistently reduce DON and FHB levels in harvested grain. Ultimately, the weather conditions and spore load in the environment will dictate the ideal fungicide application timing, whether it is earlier timing or delaying and going a bit later.

“The dual and late application also showed trends of increased thousand kernel weights. This may result from maintaining the level of fungicide in that head tissue for a longer period of time, which leads to prolonged protection, better grain

filling and higher thousand kernel weights. The later or dual applications may also potentially address fields with variable crop emergence. For example, if the FHB risk is high, one option may be to make one fungicide application when 75 per cent of the cereal heads have emerged, then go in and spray maybe a week or 10 days later to top up FHB suppression. Unfortunately, the current label indicates that fungicides for FHB can be applied up to when 50 per cent of the heads are in flower, which is likely about three days after full head emergence. In contrast, the late fungicide and dual timings in the current study would be outside of the current recommended label window for application.”

Turkington adds that some other research in the U.S. starting in 2013, and recent work at the University of Saskatchewan, supports the findings. For example, the U.S. studies trialled fungicide applications at two, four and six days after head emergence. The results showed that generally the later days didn’t compromise the level of FHB suppression, and depending on the location and year, the data suggests that six days after anthesis may be the better timing for fungicide application. The University of Saskatchewan trials in durum wheat also found that later-than-label recommendations can have potential.

“The results from the seeding rate trials showed higher seeding rates generally did increase emergence and often hastened maturity,” says Turkington. “Any practices that can help promote more uniform crop development and uniform head development help to present a more uniform target for the fungicide application. We also compared row spacings in the wheat trials and potential disease impacts of using either a narrow row spacing of seven to nine inches or a wider row spacing of 12 to 14 inches. Although research in the U.S. suggested there could be an impact, we did

not see any impact in terms of disease development. Generally, grain yield was not affected by row spacing or seeding rate. The results of the water volume trials for barley did not show any real differences, although I would like to see the trials repeated when the FHB risk was much higher than we saw in our trials. We also monitored leaf diseases in the trials. The results show that if FHB risk is a concern and there are significant issues of leaf diseases earlier in the season, then two applications will be required, an early flag-leaf stage application for leaf disease and a second posthead emergence application for suppression of FHB and DON.

“This research and results from other projects in Western Canada and the U.S. have demonstrated the need for a label change for fungicide timing for FHB. The research shows that a fungicide application at the early start of the application window compromises the suppression of FHB symptoms. In a highly susceptible crop and environment where FHB risk is moderate to high, then later or dual applications would provide suppression of FHB and DON. However, these strategies are something that requires further research and potential changes in regulation and the fungicide product label in the future.”

Turkington is continuing this research and is collaborating with AAFC colleagues Hiroshi Kubota and Kui Liu at Swift Current on feed and malting barley projects to investigate PGR timing and fungicide timing. This work will provide the opportunity to further tweak strategies to manage FHB and DON through fungicide application.

At the same time, wheat and barley breeders are working hard to develop more resistant varieties and other tools potentially to mitigate the FHB disease risks. Finding crop management options to lessen the impact of FHB in cereals remains a priority.

MARCH 19, 2024 | 9AM MST / 10AM CST

Join a panel of farmers from across Western Canada as they discuss herbicide resistance and weed management options with three members of the Bayer Market Development Agronomy team. CEU credits available

Amanda Fedorchuk Market Development Representative

Kate Hadley Market Development Agronomist

REGISTER FOR FREE SPONSORED BY

Sam Clemis Market Development Agronomist

by Bruce Barker

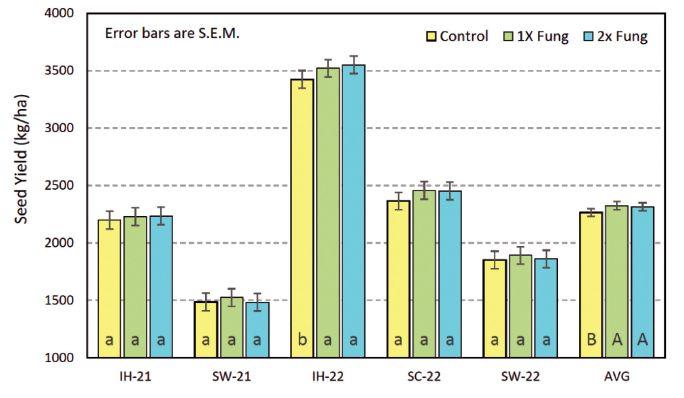

The theory is that denser plant stands resulting from higher seeding rates can create a more ideal environment for lentil diseases such as ascochyta blight and anthracnose. Conversely, higher seeding rates can lead to better stand establishment and potentially higher yields under favourable growing conditions. To explore the interaction between seeding rate, plant stand, disease development and fungicide application, a research project was conducted in 2021 and 2022 at three locations in Saskatchewan.

“Although previous work also included a weed control component, for this project, we chose to focus on seeding rates and fungicides to simplify field trial management and data collection,” says principal investigator Chris Holzapfel, research manager with the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation at Indian Head, Sask.

The research was conducted at IHARF and two other Agri-Arm sites: the Western Applied Research Corporation at Scott and the Wheatland Conservation Area Inc. at Swift Current. It was funded by the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers.

The objective was to demonstrate the effects of lentil seeding rates and subsequent plant densities on competition with weeds, disease, yield and grain quality, in addition to the agronomic response to foliar fungicide applications. A second objective was to

demonstrate the most profitable combinations of seeding rates and foliar fungicide application strategies for lentils under a range of Saskatchewan growing conditions.

This project was initiated as a follow-up to a recently concluded ADF/SPG/WGRF research project led by Jessica Enns (Weber) in collaboration with multiple Agri-ARM sites and the University of Saskatchewan. That study found that using a pre-seed residual herbicide reduced early-season annual weed populations by 66 per cent compared to the traditional pre-seed burn-off using only glyphosate. It also found that the seeding rate with the highest yield and net returns was 19 seeds per square foot (190 seeds/ m2) compared to rates of 13 or 26 seeds/ft2 (130 or 260 seeds/m2). Weed density was also highest at the lowest seeding rate. Disease severity also increased with increasing seeding rates, and a fungicide application was more likely required when lentils were seeded with a higher seeding rate.

In Holzapfel’s research, small red lentils were seeded at three rates of 13, 19 and 25 seeds/ft2. Foliar fungicide treatments included no foliar fungicide, a single fungicide application of Dyax ap -

ABOVE: A foliar fungicide application decision should be made independent of plant stand and based on an assessment of disease potential.

Seeding rate effects on lentil plant densities at Indian Head (2021 and 2022), Scott (2022), Swift Current (2021 and 2022) and averaged across all five sites

plied at early bloom at a rate of 160 ml per acre (395 ml/ha), and a dual fungicide application of Dyax at early bloom followed by Lance WDG applied approximately 14 days later at 170 g per acre (420 g/ha).

Data collection included plant densities, disease ratings, weediness ratings, seed yield, test weight and seed size. Data from Scott in 2021 were not included in the final analyses due to extreme variability caused by drought.

As expected, plant stand establishment increased linearly with increasing seeding rate.

A pre-seed burn-down and in-crop herbicides were applied, but no residual herbicides were used. While a detailed analysis of weed counts and biomass was not part of the research, a visual assessment rating found that higher weed pressure occurred at lower seeding rates. Overall, the plots were relatively clean, and the overall weediness rating was 1.7/10 at 13 seeds/ ft2and 1.4/10 for the 19 and 25 seeds/ft2 seeding rates.

The first disease rating was taken at the start of flowering, just before the first fungicide application. At that time, disease pressure was negligible at all sites, ranging from 0.1 to 1.2 per cent of stem and leaf area infected. Indian Head-22 had the highest disease pressure, and Swift Current-21 had the lowest – consistent with the wetter environmental conditions at Indian Head.

“Based specifically on these observations along with the weather and environmental conditions in late June and early July, it would have been difficult to recommend a fungicide application at all sites except IH-22, where disease pressure was low but symptoms were present and the weather/soil conditions were wetter than normal,” says Holzapfel.

Final disease ratings were conducted about seven days after the second fungicide treatment was applied. Except for Swift Current-21, where the disease rating decreased to negligible, the disease rating at the other four sites increased, although

disease pressure was still very low. At Indian Head-22, overall disease pressure remained quite low even though wet weather would have favoured disease development. Here, the disease ratings averaged 2.3 per cent at 13 seeds/ft2, 3.5 per cent at 19 seeds/ft2 and 4.2 per cent at 25 seeds/ft2 Holzapfel says that averaged across seeding rates, fungicide, not unexpectedly, did not appear to have much impact on disease at the sites with the lowest pressure.

Yields were highest at Indian Head-22 at 3,113 lbs./ac. (3,498 kg/ha), followed by Scott-22 at 2,158 lbs./ac. (2,425 kg/ha), Indian Head-21 at 1,979 lbs./ac. (2,221 kg/ha), Swift Current-22 at 1,662 lbs./ ac. (1,868 kg/ha) and Swift Current-21 at 1,333 lbs./ac. (1,498 kg/ha). At Indian Head-21, the yield was marginally higher with a higher seeding rate. In the remaining cases, yield was unaffected by seeding rate at two sites and declined with a higher seeding rate at two sites.

At Indian Head-21, the 25 seeds/ft2 seeding rate was most profitable, netting $35.22 per acre more ($87/ha) than at 13 seeds/ft2. At the other sites, the increased cost of higher seeding rates meant that relative marginal profits were neutral or lower with higher seeding rates.

Fungicide application did not result in a significant increase in yield, except at Indian Head-22, where a single or dual application yielded statistically higher at

Fungicide treatment effects lentil seed yield at Indian Head (2021 and 2022), Scott (2022), Swift Current (2021 and 2022), and averaged across all five sites

three to four per cent more than the control. Additionally, the interaction of seeding rate and fungicide did not generally affect

yield. This suggested that the response to fungicide, or lack thereof, was consistent within individual sites regardless of seeding rate.

Because of the low disease pressure and lack of yield response, the relative profit margin was lower at all sites with a fungicide application. Even at Indian Head-22, where yield was higher with a single fungicide application, the single fungicide application had the same marginal profit as the control when product and application costs were accounted for. The dual fungicide application resulted in a net loss in marginal profit of $21.05/ac. ($52/ha) compared to the control.

At the other sites, marginal profits with a single application were negative at $0.40 to $18.62/ac. ($1/ha to $46/ha) less than the control, and from $31.58 to $58.70/ac. ($78 to $145/ha) less with the dual application.

“While we know that lentils can be quite susceptible to disease and the impacts can be severe if they are not managed, these results reinforce the need to base fungicide applications on actual disease pressure and probability of response as much as possible to maximize profits,” says Holzapfel.

Overall, Holzapfel says the research indicates that seeding rates of 13 to 19 seeds/ft2 could be considered low risk and optimal from an economic point of view. If high seedling mortality is expected, a higher rate could be beneficial. The research also found that disease should be assessed outside of plant populations and that a fungicide application should be based on an assessment of disease potential, using a fungicide decision support checklist that was developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and can be found on Saskatchewan Pulse Growers’ website.

We’re guessing you didn’t get into farming for the thrill of controlling weeds. That’s where Bayer cereal herbicides come in. With a wide roster of solutions, you can be sure there’s one that’s right for your operation, no matter what cereal you’re growing.

By Bruce Barker

Like death and taxes, wild oats can’t be avoided. The weed is widespread across the Prairies, highly competitive and causes approximately $500 million in annual losses. For tame oat growers, they are especially problematic since no herbicide options exist for the control of wild oats in a tame oat crop.

“The inability of oat growers to use in-crop herbicides means growers face challenges when it comes to managing wild oats,” says Brianna Senetza, who conducted her M.Sc. research at the University of Saskatchewan’s Plant Science Department under the supervision of professor Chris Willenborg and in collaboration with research scientist Bill May with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at Indian Head.

Senetza investigated two alternative methods for controlling wild oats in a tame oat crop. The objective was to determine the potential of utilizing inter-row spraying and weed wicking of non-selective herbicides for wild oat management. Funding was provided by the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund and Western Grains Research Foundation.

Inter-row spraying uses shielded spray nozzles to apply herbicides between the crop rows. Senetza says the shields are shaped like canoes and help push the crop aside and out of the way so the spray is precisely applied to the weeds between the crop rows.

Weed wicking works to control weeds that are taller than the crop. A herbicide is brushed onto the taller weeds, leaving the crop untouched.

“We were able to use weed wicking as a strategy because wild oats typically grow taller than tame oats,” says Senetza.

The research was carried out over two years at U of S Kernen and Goodale research farms and AAFC Melfort, Sask. Camden oats were seeded at 30 plants per square foot (300 plants/m2), and the plots were supplemented with wild oats.

Thirteen herbicide treatments were applied with four replications. Wicking treatments were done using glyphosate at 0.45 litres per acre

SOURCE: SENETZA, 2023.

(600 g ai/ha). Inter-row spraying used glufosinate at 1.62 l/ac. (600 g ai/ha) plus clethodim at 76 ml/ac. (45 g ai/ha).

Application timing for both methods was at the four-, six- and flagleaf stages, four-leaf + flag-leaf, six-leaf + flag-leaf and four- + six-leaf stages. These treatments were applied as inter-row alone, wicking alone or dual inter-row and wicking treatments.

Plant counts were done two to three weeks after emergence, and phytotoxicity ratings for the crop and wild oats were done at seven to 10 days and 21 to 24 days after treatment. Yield, wild oat percentage, thousand kernel weight, test weight and percentage of plump grains were measured. Analysis of the treatments found there were no significant differences in oat yield, thousand kernel weight and test weight. Conversely, the percentage of wild oats and wild oat biomass weight were significantly lower, and plump kernels were significantly higher for some treatments.

“When I look at yield, although we expected to see differences with better wild oat control, the proportion of wild oats in the plots was really high at 34 per cent in some cases and could explain the reason for no differences in yield,” says Senetza. “But you can look at it another way and see that there was no spray damage to the crop that affected yield, so that is a positive finding.”

The poorest wild oat control occurred with the four-leaf wick and flag-leaf wick treatments. The best wild oat control occurred when dual inter-row and wick treatments were conducted at the four- + sixleaf stages and the six- + flag-leaf stages.

The treatments with the best wild oat control, along with the six-leaf

inter-row plus wick treatment, also had the highest percentage of plump seed – which can mean a premium for better grain quality.

Senetza says the research helped to narrow down application methods and treatment timing. The four-leaf wick simply didn’t work because the wild oats were the same height as the tame oats so they couldn’t be wicked.

“Overall, the combination of inter-row spray plus wicking worked better together to control wild oats. The inter-row controlled wild oats between the seed rows while the wick followed up and controlled wild oats that emerged and grew in the seed rows,” says Senetza. “Both show promise and could potentially be used for wild oat control in tame oat.”

Modest response to phosphorus but variable to nitrogen and inoculants.

by Bruce Barker

Mind your ‘Ps’ and ‘Ns’ and ‘Is’ when it comes to lentil fertility in the Brown, Dark Brown and thin Black soil zones. Phosphorus (P) can be a limiting nutrient in lentil production, but nitrogen (N) and inoculants can also affect lentil yield and profits. A recent Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture ADOPT (Agricultural Demonstration of Practices and Technologies) project looked at these three fertility inputs and how the latter two interact to impact production.

“This project was initiated to demonstrate some of the expected responses to rhizobial inoculation, starter N applications and P fertilization for a range of soil climatic zones in Saskatchewan while also exploring the potential merits of deferred N applications for increasing lentil yields and grain protein concentrations,” says principal investigator Chris Holzapfel, research manager with the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation at Indian Head, Sask.

Typically, N fertility is supplied through N fixation with the application of a rhizobial inoculant applied with the seed. Phosphorus can be a limiting factor on low testing soils, while potassium (K) and sulfur (S) are less likely to impact yields on the southern Prairies. The

objective of this project, therefore, was to demonstrate the response of lentil to a wide range of fertility management treatments that focus on P rate, rhizobial inoculation and N fertilization.

The project was conducted in the thin Black soil zone at IHARF, the Western Applied Research Corporation (WARC) at Scott, Sask., in the Dark Brown soil zone, and the Wheatland Conservation Area (WCA) at Swift Current, Sask., in the Brown soil zone in 2021 and 2022. However, drought impacted results at Scott and Swift Current in 2021, and these locations were dropped, leaving four site-years for data analysis. Small red lentil was grown at each site and managed with typical agronomic practices.

Twelve fertility treatments were applied with varying levels of P, N and granular inoculant. These ranged from zero to 60 pounds P2O5 per acre (zero to 67 kg P2O5/ha), with and without N at 49 lb. N/ ac. (55 kg N/ha) at sideband or in-season broadcast at the bud formation stage and with and without granular inoculant. Treatments

ABOVE: Phosphorus was the main driver of increased yield in this ADOPT project.

“Jiminy Crickets, what a dingdonger of a burnoff!”

The speed and performance of new Intruvix™ II herbicide is so darn good, folks can hardly contain their excitement. By applying it with glyphosate before planting cereals, they’re saying goodbye and good riddance to narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, volunteer canola, kochia and many other problem weeds. Enjoy cleaner fields, faster, while protecting your future glyphosate use. Cheese and crackers, how easy can you get?

Clean is good

without supplemental N were balanced to supply nine lb. N/ac. (10 kg/ha) across the monoammonium phosphate (MAP; 1152-0) application rates. Similarly, when N was applied, it was balanced to take into account the amount of N applied with MAP application rates. All fertilizer treatments were side-banded, or in the case of some N treatments, broadcast.

Soil tests found that Swift Current had marginal levels of 15 ppm Olsen-P, while the other sites were quite low in P ranging from two to eight ppm. Nitrate-N soil test levels ranged from 19 to 45 lb. N/ac. (21 to 50 kg/ha).

All sites targeted a seeding rate of 19 seeds per square foot (190 seeds/m2), and emergence, as expected, varied across sites due to environmental conditions. The highest stand establishment was at Indian Head, followed by Scott and Swift Current. At Swift Current in 2022, emergence was about 10 plants/ft2 (100 plants/m2), which Holzapfel says was still a reasonable stand.

“Since all fertilizer was either sidebanded or broadcast during the season, we didn’t expect the treatments to impact emergence, and this was the case,” says Holzapfel.

Yield varied widely by site-year, as expected, with Indian Head-22 yielding the highest at around 55 bushels per ac. (3,700 kg/ha) while Swift Current-22 yielded the lowest at around 28 bu./ac. (1,883 kg/ha). Holzapfel says there were highly significant differences between some treatments.

“Mostly what we saw with the treatments was that yield increased with P fertility. That was the main trend that was evident with yield increases ranging from nine to 14 per cent at responsive sites,” he says.

Swift Current did not show a response to P treatments. Relatively high residual P combined with low yields were the likely reasons.

Holzapfel says the highest and most consistent yield response was at Indian Head, with yield increasing linearly in both years. For example, in 2022, yield increased from 52 bu./ac. (3,509 kg/ha) with zero P plus inoculation to 57 bu./ac. (3,832 kg/ha) with 60 lbs. P2O5 plus inoculation.

At Scott, the P response significantly increased yield up to 20 lbs. P2O5 and then leveled off.

Fertilizer and

treatments evaluated in lentil fertility demonstrations conducted at Indian Head, Scott and Swift Current in 2021 and 2022.

Nitrogen and granular inoculant responses varied

Surprisingly, granular inoculant treatments did not affect yield regardless of field history or whether supplemental N was applied. This held true whether the data was averaged across site years and for individual sites.

“I would take this with a grain of salt,” says Holzapfel. “While we did not specifically assess nodulation, this result suggests that background levels of Rhizobiumleguminosarum in the soil were sufficient to colonize the roots and facilitate N fixation, regardless of whether an inoculant was applied.”

Holzapfel further explains that all sites had a long history of including peas and/or lentils in the rotations. The most recent pea, lentil or faba bean crop for each site ranged from two years at Swift Current, to four years at Scott and Indian Head. This would have contributed to adequate background levels of rhizobia in the soil.

“However, I can’t look at anyone with a straight face and say don’t use an inoculant,” says Holzapfel.

Lentil yield response to N treatments occasionally occurred, especially to sidebanded N, but was inconsistent and not easy to predict. At Indian Head-22, extra N increased yield when no inoculant was applied, as expected. But at Swift Current-22, it was unexpected that the N plus inoculant would

provide a yield response. The discrepancy in the N response at Swift Current was likely largely due to random variability. Holzapfel says that across the sites, the response was small but at least marginally significant.

Lentil seed protein content was also an important factor that was measured because of the increasing demand for plant-based protein sources. Protein concentrations varied with location, averaging 26.6 per cent at Indian Head in both years, 24.2 per cent at Swift Current 2022 and 23.8 per cent at Scott 2022. Holzapfel says this could have been more to do with variety genetics than environment as there were no treatment effects of P, N or inoculants on protein content. CDC Proclaim Cl lentil variety was grown at Indian Head, while CDC Impulse CL was grown at Scott and Swift Current.

“Perhaps this result would have differed if we had observed stronger responses to either inoculant or N fertilizer,” says Holzapfel. “However, we must conclude that lentil protein concentrations are more likely to be impacted by the environment, or potentially genetics, than fertility management.”

Holzapfel is currently working on two more lentil research projects. The first is the relative performance of red versus green lentils in soils with high residual N levels. The second is lentil yield response to applications of potash and sulfur fertilizer.

looking for six women making a difference in Canadian agriculture. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving Canada’s agriculture industry.

BRUCE BARKER, P.AG CANADIANAGRONOMIST.CA

Environment and Climate Change Canada has set a goal to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen (N) fertilizer by 30 per cent below 2020 levels by 2030. Reducing nitrous oxide N2O emissions will be a key strategy in meeting this goal while maintaining or increasing crop yields.

A cross-Canadian Prairie research study examined the effect of fall and spring application timings of urea and anhydrous ammonia treated with enhanced efficiency fertilizers (EEFs) on spring wheat performance and N2O emissions. Mario Tenuta, senior industrial research chair in 4R nutrient management and professor of soil ecology at the University of Manitoba, summarized the Manitoba research that evaluated the impact of using multiple EEF sources compared to conventional urea, and fall and spring application timings, on spring wheat yield and protein content over three years, along with the impact on N2O emissions.

Research was carried out in southern Manitoba at Warren and Glenlea in 2015, Carman and La Salle in 2016 and Kelburn and Ridge in 2017. All sites had residual nitrate-N soil test levels less than 89 pounds per acre (100 kg/ha) and were on soybean stubble.

Nitrogen fertilizer sources compared were an unfertilized control, untreated urea and four EEFs including urea plus a urease inhibitor (Limus); polymer-coated urea (environmentally smart nitrogen [ESN]); urea plus a nitrification inhibitor (eNtrench); and urea plus nitrification and urease inhibitors (SuperU). Application timing included late fall banding at one to two inches (2.5 to 5 cm) depth and spring banding at seeding in a one-pass operation at one to two inches, both treatments done in a mid-row band placement.

Fertilizer rates were based on provincial soil test recommendations. All plots were seeded to AAC Brandon and were managed with standard agronomic practices.

At five of six site years, wheat yield and protein content were not affected by N fertilizer source. The only site where N source impacted yield and protein content was Kelburn-17. At this site, the controlled-release product ESN produced significantly higher yield than urea and urea + Limus. It also produced grain protein content significantly higher than urea, SuperU and urea + Limus.

The impact of application timing on wheat yield and protein content was variable. Three of six site-years had lower yield with fall application compared to spring application, while one site had

higher yield with fall application and the other two sites had similar yields with fall and spring applications. Four of six sites had similar protein content for both spring and fall application, while fall application had lower protein content at the other two sites.

Urea + Limus did not significantly reduce N 2O emissions compared to untreated urea. ESN also did not significantly reduce emissions.

However, products containing a nitrification inhibitor significantly and consistently reduced N2O emissions. Urea + eNtrench reduced cumulative N2O emissions by 47 per cent to 64 per cent at four of six site-years irrespective of application timing. SuperU also reduced N2O emissions by 37 per cent to 57 per cent at three of six site-years. ESN significantly reduced emissions at Warren-15 by 44 per cent compared to untreated urea, but reductions were variable at other site-years.

Application timing also impacted N 2O emissions. Overall, fall application produced 33 per cent to 67 per cent higher N2O emissions at three of six site-years compared to a spring application. This was mainly due to emissions during the spring thaw. There wasn’t any interaction between source and timing at five of six site-years.

Overall, compared to untreated urea across all site-years, the products containing nitrification inhibitors significantly reduced cumulative N2O emissions by 38 per cent for urea + eNtrench, and 43 per cent for Super U, irrespective of application time. The effectiveness of these nitrification inhibitor products was attributed to the slower conversion of NH4+ to NO3-, reducing nitrification and subsequent N2O emissions.

The research provides guidance to policymakers on developing cost-share programs to encourage the use of EEFs to reduce N2O emissions. Currently, under the On Farm Climate Action Fund program, dual-inhibitor products are eligible for incentives, but single nitrification inhibitor products have not qualified to date. The results of this study show that single nitrification inhibitors are as effective as dual inhibitors for urea fertilizers.

The study also advances the understanding of 4R nutrient management as it relates to N management practices and how EEF fertilizers can play a role in helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, since few yield or protein content benefits were found in the research, other policy mechanisms to encourage the use of EEFs need to be investigated.

Bruce Barker divides his time between CanadianAgronomist.ca and as Western Field Editor for Top Crop Manager. CanadianAgronomist.ca translates research into agronomic knowledge that agronomists and farmers can use to grow better crops. Read the full Research Insight at CanadianAgronomist.ca.

Every day new challenges, obstacles, roadblocks and uncertainties threaten your farm’s progress. That’s why you need solutions that work. You need agronomists that know the industry. You need answers. Because regardless of the unknowns, you always have to make a decision. Make the most with what you’ve been given by tapping into the nutrient enhancing technologies from Koch Agronomic Services proven to create a positive impact in your fertility program.