REDUCING THE IMPACT OF FHB

In-crop management strategies for barley PG. 18

TAKE-ALL IN CEREALS

Cases may be low but this disease can still cause problems PG. 10

REVISITING CEREAL SEEDING R ATES

New seeding rates for highyielding varieties PG. 16

In-crop management strategies for barley PG. 18

Cases may be low but this disease can still cause problems PG. 10

New seeding rates for highyielding varieties PG. 16

10 | Take-all in cereals

Cases of take-all may be low, but with the right conditions, this disease can still pose a problem.

By Julienne Isaacs

4 What’s old is new again

By Stefanie Croley

UPDATE 34 Is wider-row spacing in wheat possible?

By Bruce Barker

16 | Revisiting cereal seeding rates

Research is pending on new seeding rates that are more in line with today’s high-yield varieties.

By Bruce Barker

AND NUTRIENTS 6 Managing yield and protein in spring wheat

By Bruce Barker

24 New barley traits for better malt, beer and malt whisky

By Carolyn King

AG RISK MANAGEMENT SURVEY REVEALS OPPORTUNITIES

Based on a recent cross-Canada agricultural risk survey, Farm Credit Canada (FCC) has released a list of key themes and take-aways. Risks include production, marketing, financial, human resources and legal. One major take-away? Canadian farm operations have an impressive track record for identifying and mitigating risks.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility

Manager. We encourage growers to check

labels for complete instructions.

18 | Reducing the impact of FHB in barley

In-crop management strategies for suppression of Fusarium head blight.

By Donna Fleury

PESTS AND DISEASES

30 Upping wheat’s defences against “the big bad”

By Carolyn King

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

There are deadlines aplenty in the world of magazine publishing, so it shouldn’t surprise you that most editors – myself included – are deadline-oriented people.

As it turns out, my deadlines for the Mid-March issue typically fall during the week of our annual Top Crop Summit event (more on that later). Despite how many times I resolve to get my column done before the event, I usually find myself writing my editorial note for the Mid-March issue on my flight home from Saskatoon. After all, sometimes you have to wait until that perfect moment of inspiration strikes, and for me, that moment used to strike while on a plane, feeling freshly inspired after a few days of networking and learning at an event.

My commute home from the Top Crop Summit was several thousand kilometres shorter this year, but while we were putting this issue together, I noticed a link between some of the sentiments shared at the Top Crop Summit and the articles in this, our annual cereals-themed issue. We often talk about how new threats can pop up at any time and we need to combat them with a toolbox approach – there’s no silver bullet. But when constantly focusing on what might happen, it’s easy to get complacent and forget about the “old” threats – diseases or pests that might not be on the radar this year but could make an appearance again and cause problems in your fields.

Take the story on page 10, for example. Despite having several years of involvement in the agriculture world under my belt, I admittedly had never heard of take-all until very recently. As Kelly Turkington, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada based in Lacombe, Alta., shared with writer Julienne Isaacs, the disease was prevalent in the mid-to-late ’90s, but has nearly disappeared from the laundry list of potential threats to cereal growers thanks to good agronomic approaches and management practices. A “good news” story, but with the right conditions, the disease can easily make a comeback and devastate a crop . . . something we’ve all heard before.

At the Top Crop Summit, several speakers reminded the audience about the importance of maximizing all of the tools in the toolbox, but also focused on remembering to keep up with what we know. It’s important to be economical with your time and return on investment, but don’t just write off an agronomic practice, an “old-school” method, or a low-risk disease threat in favour of something new. Sometimes, what’s old is new again.

@TopCropMag /topcropmanager

of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374

Power up your

Power up your savings by mixing Aim® EC with Express® brands and/or Command® 360 ME

Doing your spring burnoff with glyphosate alone might seem effective enough – but watch what happens when you power-up by adding Aim® EC herbicide. The fast-acting Group 14 mode of action stomps the life out of many tough weeds, ixncluding those resistant to other modes of action. You can also keep your gaming choices open. Aim EC herbicide has multiple tank-mix options and can be used prior to all major crops.

For yield and protein, stick with the tried and true.

by Bruce Barker

Over the last decade, spring wheat yield potential has increased, and research has focused on how to maximize this yield and maintain adequate protein content levels. This has led to research on whether late season application of Urea Ammonium Nitrate (UAN; 28-0-0) or dissolved urea (46-0-0) can help maintain or boost protein content.

“When you look at 4R principles of nutrient stewardship – the right rate, time, source and place – there may be an opportunity to apply most of the nitrogen early in the season, and then follow up later with some form of nitrogen to increase protein content,” says Mike Hall, research co-ordinator with Parkland College and the East Central Research Foundation in Yorkton, Sask.

In theory, the relationship between yield and protein is the basis for the late application of nitrogen (N) to increase protein. As N availability increases, yield levels off first, but protein content continues to increase with higher levels of N availability. This can create an opportunity for applying N later in the growing season to increase protein content.

To test this theory, Hall and his colleagues at AgriARM sites

in Indian Head, Melfort, Outlook, Prince Albert, Scott, Redvers, and Swift Current, Sask., looked at the impact of late-season N on wheat yield and protein from 2018 through 2020. The work in 2018 was funded by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture’s ADOPT program, whereas the work in 2019 and 2020 was funded by the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission.

In 2018, the treatments included 70 or 100 pounds of nitrogen (lbs. N) sidebanded at seeding, 70 lbs. N sidebanded plus 30 lbs. N of UAN dribble-banded pre-boot, 70 lbs. N sidebanded plus 30 lbs. N of UAN foliar sprayed at post-anthesis, and 70 lbs. N sidebanded plus 30 lbs. N of UAN dribble banded at post-anthesis.

When the N rate was increased from 70 to 100 lbs. sidebanded, the yield was increased significantly by 3.3 bushels per acre (up to 60 bushels/ac) and protein increased by one per cent up to 14.1 per cent. For the other treatments where 70 lbs. N was sidebanded at seeding and 30 lbs. N was top-dressed later in the season,

ABOVE: Applying all of the nitrogen at seeding was always as good as or better than splitting applications.

It’s time to get serious about the early season health of your cereals, peas and lentils.

Lumivia™ CPL provides outstanding protection from wireworm, cutworm, armyworm and pea leaf weevil. With a unique mode of action and a favourable environmental profile, it is proven to maximize early season seedling stand establishment, increase plant count and manage risk from insects.

Book Lumivia™ CPL today. Contact your crop protection retailer.

lumiviaCPL.corteva.ca

™

Over the two years, there were significant differences between treatments. (Same letters represent statistically similar results.)

protein was increased by an average of 0.8 per cent over the 70 lbs. N sidebanded, with the UAN foliar sprayed post-anthesis as the best of those treatments.

However, Hall says that none of the split applications were any better than putting all the N down as a sideband at seeding. This finding was similar to research by soil scientist Ross McKenzie, who found that, in 26 site-years across the Prairies from 1998 to 2000, putting 67 lbs. N/ac (75 kg N/ha) at seeding was just as effective as a split application of 53 lbs. N (60 kg) at seeding followed by broadcast ammonium nitrate (36-0-0) of 14 lbs. N (15 kg) at tiller, boot or anthesis. The protein increases were also not economic at most sites. McKenzie concluded that in-crop applications were less reliable than applying additional N fertilizer at or before seeding.

In 2018, the same approach was conducted at the AgriARM sites but with a base rate of 100 lbs. N/ac sidebanded, with a split application of an additional 30 lbs. N at the same timing. The main difference in results compared to the base rate of 70 lbs. N was that the protein increase was about 0.6 per cent as compared to 0.8 per cent.

“Basically, there was more N in the system, so you reach a point of diminishing returns for the additional N applied, but the results were pretty much the same,” Hall says.

1.70NSB 2.100NSB

$/AC (+ PROTEIN PREMIUM – COST OF N – COST OF APPLICATION) (ALL SITES)

3.70NSB+30N(15.7%UANdribble@boot)

4.70NSB+30N(28%UANdribble@boot)

5.70NSB+30N(14%UANdribble@Post-anthesis)

6.70NSB+30N(28%UANdribble@Post-anthesis)

7.70NSB+25N(15.7%UreaSol'ndribble@Post-anthesis)

8.70NSB+30N(14%UANfoliar@Post-anthesis)

9.70NSB+25N(15.7%UreaSol'nfoliar@Post-anthesis)

When economic return for the 16 site-years was analyzed, none of the split applications were shown to generate as much income as putting 100 lbs. N down at seeding.

In 2019 and 2020, the AgriARM sites conducted a similar trial but included dissolved urea (melted).

The base rates were 70 and 100 lbs. N/ ac. UAN was additionally dribble-banded to the 70 lbs. N rate at the boot or postanthesis stages, at either full strength (28 per cent N) or cut in half with water (15.7 per cent N), with both rates delivering 30

lbs. N/ac. UAN (15.7 per cent N) was also broadcast at post-anthesis at 30 lbs. N. A fourteen per cent urea solution, delivering 25 lbs. N/ac, was also dribble-banded or broadcast-applied at post-anthesis. The intent had been to compare melted urea at a rate of 30 lbs. N/ac, but a calculation error resulted in only 25 lbs. N being applied at all sites in both years.

“Despite the calculation error, there are a lot of good insights with the results

“. . . Split applications of N to raise grain protein should be viewed as a rescue treatment for an under-fertilized crop, rather than a planned practice.”

from this study, and I think the findings are still very relevant,” Hall says.

Over the two years, there were significant differences between treatments. Simply adding an additional 30 lbs. of N sidebanded at seeding to the 70 lbs. N base rate significantly increased yield by 3.2 bu/ ac and grain protein content by 0.5 per cent. This yield was significantly higher than all other treatments except the UAN (both concentrations) applied as a dribble band at the boot stage, which tended to increase protein a little bit but also tended to result in a little less yield, Hall says.

All of the post-anthesis treatments except for one (28 per cent UAN dribble) resulted in statistically higher grain protein, but all of them also resulted in statistically

lower yield. For example, dribble banding straight UAN (28 per cent N) postanthesis significantly increased grain protein by 0.32 per cent but resulted in a significantly lower yield – 4.8 bu/ac less –compared to the side-banded check of 100 lbs. N/ac.

Leaf damage was significantly lower for the boot stage applications compared to the remaining post-anthesis timings. Among the post-anthesis timings, broadcast spraying UAN caused the most damage, but Hall cautions that the lower rate of N with dissolved urea might have played a role.

The 16 site-years were analyzed for economic return. The gross returns minus the variable cost of added nitrogen

minus the additional cost of applying a split application was calculated. A base price of $5.84 per bushel for 12.5 per cent protein wheat was assumed, along with a protein premium or discount of $0.60 per one per cent per bu (/%/bu) and an N cost of $0.50/lbs. regardless of product used. In addition, an extra cost of $5/ac was added for all split applications.

When all the sites were combined, none of the split applications of N generated as much income as putting 100 lbs. N down at seeding. Hall also divided the 16 sites into the top eight and bottom eight yielding sites to see if there was a difference in yield, protein or economic response. He found the trends similar to the combined 16 site-years.

“Overall, I still hold the opinion that split applications of N to raise grain protein should be viewed as a rescue treatment for an under-fertilized crop, rather than a planned practice,” Hall says.

Our recycling program makes it easier for Canadian farmers to be responsible stewards of their land for present and future generations. By taking empty containers (jugs, drums and totes) to nearby collection sites, farmers proudly contribute to a sustainable community and environment. When recycling jugs, every one counts.

Ask ag-retailers for a collection bag, fill it with rinsed, empty jugs and return to a collection site. Find a collection location near you at cleanfarms.ca

Cases of take-all may be low, but with the right conditions, this disease can still pose a problem.

by Julienne Isaacs

In the mid-to-late 1990s, when Kelly Turkington was new to the job as a pathologist for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, he remembers getting called out to fields with Bill Chapman, a specialist for Alberta Agriculture.

“We would encounter large patches in fields where something was wrong – the plants were shorter and prematurely ripened, and in many cases, there was very little root tissue left,” Turkington says.

The culprit was a disease of cereals caused by the fungal pathogen Gaeumannomyces graminis called take-all, so named for its devastating impact on the root system and stem base, which then affects the entire plant via reduced access to water and nutrients. When it’s a problem in a field, take-all can have a significant impact on yield –much greater than, say, common root rot, Turkington says.

If take-all is severe, plants will be stunted with charcoal-black stem and root system discolouration and disintegrated roots, such that plants can easily be pulled from the ground.

These days, Turkington doesn’t often get calls about take-all.

It’s typically a problem in fields with continuous cereals or where wheat has been planted into grassland, he says. In a sense, take-all’s apparent disappearance from most producers’ radar is a good news story for the industry. The disease can be prevented via agronomic approaches that have become industry-standard.

But take-all hasn’t disappeared, and as there are no resistant varieties, it can still crop up for western Canadian producers if conditions are right. Here’s what to look for, and key management strategies to prevent take-all from gaining a foothold.

The take-all pathogen survives in hyphae in infected crop residues; plants become infected when healthy root systems contact infected

TOP: Take-all infection can cause near-complete destruction of the root system and blackish discolouration.

INSET: Take-all can be identified by finding prematurely ripened plants.

This isn’t a business for pretenders.

When your entire season is on the line, you know the right call is going with a pro. For over 24 years, Liberty® 150 herbicide has been the choice of InVigor® hybrid canola growers. In addition to a trusted formulation and consistent, industry-leading performance, it’s backed by exceptional agronomic support and service. Because like you, Liberty has earned its reputation in more ways than one. Visit agsolutions.ca/Liberty to learn more.

Save $1/acre* on Liberty by qualifying for the InVigor Reward.

*To see Full Terms and Conditions, visit agsolutions.ca/rewards

Always read and follow label directions.

residue during plant growth. Once infected, there may also be rootto-root spread via growth of runner hyphae of the take-all pathogen.

“The worst-case scenario is favourable conditions early, at the timing of seedling growth and early plant development, so the pathogen becomes established and progresses up through the root tissue and into the crown tissue and into the stem base,” Turkington says.

Once the disease destroys the root tissue, water and nutrient deficiencies cause premature ripening and stunting of the rest of the plant.

“Any healthy root tissue left cannot keep up with water and nutrient demands from the plant, especially if conditions become drier towards and during grain filling. So they’re stunted and very easy to see in the field, as small to large patches of plants may be affected,” Turkington says.

He adds that these types of symptoms and the appearance of affected patches of plants tend to occur during summers that are wet or in systems that rely on irrigation. Infection is typically limited in dry summers. “Most of the crop is fine, with the odd plant here and there that may be completely prematurely ripened,” he explains.

Turkington believes a combination of factors may be limiting take-all in western Canadian fields.

Diversifying crop rotations is the biggest factor, and the addition of canola to cereal rotations effectively breaks up the disease cycle. “Fields with canola see limited take-all,” Turkington says. If take-all is found in a field, a two-year gap in host plants is recommended, but even a single year of canola will go a long way to reducing take-all risk, he adds.

Pulses are also a good rotation choice, but even oats and rye present fewer potential problems with take-all than wheat or barley. Oat

is affected by a different type of take-all pathogen, which doesn’t affect wheat and other small grain cereals, Turkington explains.

“The other critical thing is to look at whether you’re controlling your volunteer wheat, which will carry the pathogen over between growing seasons,” he says.

Soil testing for micro and macronutrients is also key in preventing take-all; soils with copper, manganese, zinc, nitrogen, phosphorus, or potassium deficiencies are more vulnerable to infection. However, nutrient deficiencies may also result in poorer root growth, whereby balanced fertilization helps to promote root development, which may allow the plant to compensate even though it is affected by take-all, Turkington says. Nutrient deficiencies in the soil tend to work like a “dimmer switch” rather than an “on-off switch,” and soils that are deficient in one or more of these nutrients will be more vulnerable to take-all.

Turkington adds that lime, which is often added to soils as part of a clubroot management strategy, can increase the risk of take-all, which becomes more severe in neutral or alkaline soils.

Seed treatments can limit early season infections, but benefits have tended to be limited and variable with suppression at best, Turkington says. This may be related to shifts in the fungicides available as older, more effective products such as those containing triadimenol are no longer on the market. Another issue is that, for some fungicide actives, there may be more movement into seedling leaf and shoot tissues versus root tissue, which limits their efficacy.

He believes the move toward conservation tillage and the adoption of direct seeding may have helped deter take-all, creating a more biodynamic soil environment that speeds up infected residue decomposition and creates a more vibrant soil microbial environment that helps to limit the take-all pathogen.

Producers can find scouting and disease risk information from the Prairie Crop Disease Monitoring Network (PCDMN) in-season. Find them on twitter at @pcdmn. Scouting tips can be found on the PCDMN blog at https://prairiecropdisease.blogspot.com.

Steady as she goes.

by Bruce Barker

Are wheat, oat and barley seeding rates still valid with today’s high-yield varieties? That’s what Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development set out to find with research in 2017 and 2018. Two years of trials found that current seeding rates are OK, but more research is pending.

“This research was conducted because previous seeding rate recommendations were made when varieties had lower yield potential. We wanted to know if those recommendations were still valid with higher yielding cultivars,” says Anne Kirk, cereal crop specialist with the Crop Industry Development Branch of Manitoba Agriculture.

Currently, Manitoba Agriculture recommends target plant stands of 23 to 28 plants per square foot (plants/ft2) for spring wheat, 18 to 23 plants/ft2 for oat, and 22 to 25 plants/ft2 for barley.

Kirk says that previous research in North Dakota found that optimum plant populations can differ by both crop type and variety, and that optimum seeding rates for spring wheat ranged from 14 to 46 plants/ft2 depending on the characteristics of the variety. With this in mind, Kirk set out to see if the current seeding rates were still valid in Manitoba.

The research was conducted in 2017 and 2018 in Arborg, Carberry, Melita and Roblin, Man. Two varieties of spring wheat, oat and barley were planted at five seeding rates. Target plant populations were 15, 21, 27, 33, and 39 plants/ft2. Varieties tested were the ones popular with farmers, and also included different wheat and barley classes, Kirk says.

In wheat, AAC Brandon (CWRS) and Prosper (CNHR) varieties were tested. In barley, the malt variety AAC Synergy was

Wheat yield (bu/acre) at five target plant densities at Carberry and Melita. Statistically significant differences are shown by letters below the line. Treatments within the same site with the same letter are not significantly different (P<0.05).

tested, along with a two-row feed barley CDC Austenson. The white milling oat varieties CS Camden and Summit were tested in the trial.

Stand establishment increased as seeding rate increased at most site years, but there was also no significant difference in plant stand between seeding rate treatments at some locations where stand establishment was very high at all seeding rates.

The research also looked at heads per square foot (heads/ft2) to see if there were differences in the amount of tillering that occurred in order to compensate for lower plant populations. Kirk found that there was no significant difference in heads/ft2 between seeding rates at two of four wheat sites, four of five barley sites,

ABOVE: AAC Synergy barley planted at target plant stands of 15, 27, and 39 plants/ft2 at Carberry 2017.

Barley yield (bu/acre) at five target plant densities at Arborg, Melita and Roblin. Statistically significant differences are shown by letters below the line. Treatments within the same site with the same letter are not significantly different (P<0.05).

and two of five oat sites, which she says demonstrates the ability of cereal crops to compensate for reduced plant populations by increasing tillering.

Current seeding rates seem adequate

Kirk says the results from this study suggest that the current recommended target plant populations for wheat, barley, and oat are sufficient for optimum yield. At the wheat sites, there was a general trend of higher yields with increased plant stand. However, there were no significant differences in yields between target plant stands of 21 to 39 plants/ft2 at three of the four sites. At the fourth site, the target plant stand of 33 plants/ft2 yielded significantly higher than 21 plants/ft2, but there were no significant differences

Oat yield (bu/acre) at five target plant densities at Carberry, Melita and Roblin. There were no statistically significant yield differences (P>0.05) between plant densities.

in yield between the highest three target plant stands.

At the majority of sites, both wheat varieties tested had similar responses to each target plant stand, indicating that similar seeding rate recommendations could be made for both varieties of each crop type studied.

The oat and barley sites showed similar yields across a range of plant stands, with one exception at the Roblin 2017 barley site, where the highest seeding rate had a significantly lower yield.

“It’s good that farmers likely haven’t been missing out on potential yield by using too low of a seeding rate,” Kirk says. “The research is going to be conducted again in 2021 with lower seeding rates to get a better handle on yield potential when farmers are left with an unintentionally thin stand.”

In-crop management strategies for suppression of Fusarium head blight.

by Donna Fleury

Not just a disease of concern for wheat growers, Fusarium head blight (FHB) – caused by Fusarium graminearum – is also recognized as a barley production issue across the Prairies, for both malt and feed production. Current management tools do not completely mitigate risk. Therefore, researchers are investigating potential crop management strategies for FHB suppression in barley.

“Although FHB wasn’t initially thought to be a concern for barley growers, by the mid- to late 1990s it became apparent that barley was as affected by F. graminearum as wheat,” explains Kelly Turkington, plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta. “FHB and deoxynivalenol (DON) contamination influence malt barley yield and end-use quality, and have caused a westward shift in the malt selection areas for Canada and the US. Maltsters have a low tolerance and will not accept barley with DON levels nearing one ppm or higher, and similar limits affect the feed grain market for hogs.”

In 2018, a five-year Barley Cluster project led by Turkington was initiated to investigate in-crop management strategies to re -

duce the impact of FHB in barley. The objective of the Test 92 project is to determine if water volumes, seeding rates and fungicide timing and their potential interactions affect FHB development, leaf disease, DON content in harvested grain, crop productivity and kernel and malting quality. The AAC Synergy two-row malt barley variety, with intermediate resistance to FHB, was used at most sites. There are eight study sites across Canada, including: Lacombe and Lethbridge, Alta.; Scott, Melfort and Indian Head, Sask.; Brandon, Man.; Normandin, Que.; and Charlottetown. Turkington is also leading a similar project investigating cropping strategies for FHB in wheat.

For the study, water volumes of 20, 40 or 60 L/ac are being compared to see if higher water volumes might provide better coverage and better efficacy of fungicide applications in suppressing FHB and DON. Based on recommendations from Tom Wolf, of AgriMetrix Research and Training, a dual nozzle setup for fungicide application is being used. Seeding rates of 200 versus 400 seeds/m2

ABOVE: Symptoms of FHB in barley, 2019.

looking for six women making a difference to Canada’s agriculture industry. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services to farm operations, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving the future of Canadian agriculture.

Symptoms of Fusarium head blight in barley aren’t as distinct as they are in wheat, thus often leading to an incorrect diagnosis. Infected crops show discolouration, which can be confused with hail damage, bacterial infections or net blotch diseases.

are being compared to determine if a higher seeding rate might provide a more uniform stand and improve fungicide application. For the fungicide timing experiments, four treatments using Prosaro XTR are being compared: no fungicide, the ideal timing of fungicide applied one to two days following full head emergence, fungicide applied seven to 10 days following one to two days after full head emergence and a dual fungicide application at one to two days following full head emergence and again at seven to 10 days after full head emergence. Of note, for the four different timing treatments included in the research trials, the later stage may be outside the normal window and dual applications are not yet approved on the label, plus there are still pre-harvest interval considerations.

“One of the challenges with barley is the FHB symptoms are not as distinct as in wheat and can often be confused with other conditions,” Turkington says. “There isn’t the same kernel shriveling, and although infected crops show discolouration, it can often be confused with hail damage, spot blotch and net blotch diseases or bacterial infections. Growers also need to be scouting for emerging leaf disease problems and, if there is a significant leaf disease problem at the flag leaf emergence or just before the emergence of the second leaf from the head, then a fungicide should be applied at that stage. The timing for leaf disease management will depend on when the symptoms begin to show in the field and weather conditions. Flowering or anthesis starts just before head

emergence, continues during heading, and lasts approximately 14 days. Depending on the risk, delaying a leaf disease application until anthesis or longer could compromise the level of leaf disease management, allowing the fungus to move up from the lower and middle canopy onto the emerging head. However, a later application may provide better suppression of FHB and DON reductions.”

Another challenge specific to barley is the potential persistence of DON through the malting process. Turkington explains that malt barley may meet all the specifications and have desired characteristics for malting quality, but not testing for DON could cause problems. DON is water-soluble, and when barley is brought into the malting process to the steep tanks, the process of steeping in water can initially show a decline in DON. However, when moved to the next stage of germination, the temperature range can encourage it to grow and there can be in increase in DON. At the final kiln stage, the heat may kill the fungus, but DON persists and can be a factor in the brewing process. Therefore, for achieving malting barley status in relation to FHB, DON is the primary driver.

Preliminary results for Test 92 from 2018 and 2019 have been completed, but due to COVID-19 delays some of the 2019 DON data and analysis is still being completed. Grain samples for grain and malting quality assessments have been sent to the Canadian

Grain Commission, with evaluations currently underway. The study was originally intended for the growing seasons of 2018, 2019 and 2020. However, due to issues with COVID-19, the 2020 growing season experiments were cancelled and are now scheduled for 2021, which is still within the timeframe of the current Barley Cluster that runs from April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2023.

“Generally, for the study sites in 2018 and some sites in 2019, conditions were fairly dry, with limited leaf disease, FHB and DON development,” Turkington says. “In 2018, there was some indication that higher water volumes might have helped improve leaf disease control and perhaps lead to a bit better reduction in DON levels. However, we didn’t see that same pattern in 2019 for leaf disease, even with the high levels of disease at sites such as Lacombe. We are still waiting on the DON data to see if there were any effects of water volume and other treatments on DON levels. “

“A later [leaf disease] application may provide better suppression of FHB and DON reductions.”

For fungicide timing, the preliminary results show that the optimal timing varied depending on the site and seasonal leaf disease development, with the greatest treatment responses at sites where there were higher levels of leaf disease. Early indications are that early and dual applications tended to do a bit better, and had significantly lower disease compared to the check treatment at some sites. Delaying fungicide application to later stages may compromise leaf disease management and crop productivity when leaf disease risk increases as the barley crop progresses from flag leaf emergence to heading. However, applying an early application at 70 per cent head emergence still leaves 30 per cent of the heads without any

Early Take offer ends soon. Book by March 15th, 2021 and SAVE up to 18% with Flex+ Rewards.*

The best offence is a good defense. With Prospect™ herbicide, your canola will have the best start possible. Prospect tank mixed with glyphosate will give you gamechanging performance against the toughest broadleaf weeds, including cleavers and hemp-nettle.

for 2021!

fungicide contact or protection. The weather conditions prior to and after head emergence, and its impact on spore load at the time of application and infection conditions, will be a deciding factor in the timing of application for FHB and DON management. For leaf diseases, producers can follow disease progression earlier in the season and then, along with weather conditions, gauge the risk of leaf disease and fungicide need around the flag leaf stage through to head emergence.

Turkington notes that, overall, the preliminary results show the interaction of water volume, seeding rate and fungicide timing did not significantly affect leaf disease development and had limited impact on grain yield and kernel characteristics. Treatment effects, especially in terms of fungicide timing, generally reflected the amount of leaf disease present at each of the sites. “However, once

we have DON data and analysis completed for all years, this will provide additional information about the effects of dual and later fungicide applications for FHB and DON management. By the end of the project in 2022, we expect to have more information for growers, which may indicate the need for potential label changes for the addition of a dual application or later application,” Turkington says. “Factors such as economics and pre-harvest intervals will also need to be considered. Addressing both FDK [Fusariumdamaged kernels] and DON management in cereals may require a change in mindset, regulations, or chemistries.”

“Addressing both FDK and DON management may require a change in mindset, regulations or chemistries.”

Growers should continue to use an integrated approach for managing FHB and DON, as well as leaf diseases in barley. Select the best resistance package for the variety being grown, use recommended crop rotations and agronomics for a establishing a competitive and uniform crop, and include fungicide applications. Scout for leaf diseases and monitor conditions for risk of FHB disease. When applying fungicides, consult and follow the advice of spray technology experts and consider increasing water volume, which may help to improve management of leaf disease, Fusarium-damaged kernels (FDK), and DON. Using an integrated approach of fungicides and in-crop management strategies can reduce the impact of FHB in barley.

When it comes to controlling broadleaf weeds, we are always up to the challenge. With three powerful herbicide Groups, In nity® FX herbicide is the best way to take out over 27 different broadleaf weeds, including kochia and cleavers. Use In nity FX to manage resistance and get back to farming. GET

Keeping pace with the rapidly changing needs of the malt beverage value chain.

by Carolyn King

Along with ongoing advances in agronomic traits, the malting barley varieties released by the Field Crop Development Centre (FCDC) at Olds College in Alberta are meeting the increasingly diverse needs of the malt beverage industry. A key aspect of the centre’s malting breeding program is the addition of new market-driven specialty traits into its varieties.

“We get requests for new traits every day,” says FCDC barley breeder Dr. Flavio Capettini. “The malting, brewing and distilling industry is changing very quickly. For instance, as the domestic malting and brewing industry expands to include many small craft brewers and distillers, Canada has a very wide array of beer types that we didn’t have just a few years ago. And the international markets are changing too. Canada is a big exporter of malting barley and of malt processed in our country. We need improved barley varieties that meet the changing demands of these markets while also covering the needs of our farmers.”

With the centre’s move from Alberta Agriculture and Forestry to Olds College in January 2021, Capettini has become the new head of the FCDC’s malting barley breeding program. He emphasizes, “Dr. Pat Juskiw, who has been leading the malting barley program, is the one who has been on top of these new traits and guided the development of the varieties.”

The breeding program stays up to date on the latest traits by communicating and working with the industry.

Capettini summarizes, “We discuss our upcoming varieties with the seed companies. We communicate with the malting companies about new traits demanded by the market so we can start working on those traits. We have always worked closely with the large brewing companies, and now we are also working with the craft brewers to meet their needs. And they test our varieties so we can get feedback and know where to focus next.” He also notes that the move to Olds College has opened the door to collaborating with the college’s Brewmaster program on the testing of the FCDC’s advanced malting lines and varieties.

The FCDC is able to tap into top-notch genetic resources for new traits. “We have one of the most diverse barley breeding programs in Canada. We have a large base of germplasm with a wide range of genetic characteristics, and we also have a germplasm bank where we can seek traits in barley from around the world,” Capettini says.

ABOVE: The FCDC’s TR14617 is the first Canadian malting barley variety that is non-glycosidic nitrile (non-GN), a trait in high demand by the malt beverage industry.

“Although breeding takes time, we try to add these new traits to our breeding lines as quickly and efficiently as possible because it is fundamental to keep up with market needs.”

Molecular markers are one of the tools the FCDC uses for more efficient breeding. Markers allow breeding programs to quickly screen the DNA of breeding materials for specific traits, rather than having to grow the plants to see if the traits are expressed.

Take control. Start clean and eliminate weed competition with the power of the Nufarm pre-seed burndown portfolio in canola, cereals, pulses and soybeans.

• PERFORMANCE – Manage those toughest weeds early including kochia, cleavers, narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, volunteer canola and more.

• CONVENIENCE – All-in-one formulations make load times quicker. Tank-mix with glyphosate. No additional surfactants required.

• RESISTANCE MANAGEMENT – Built-in with multiple modes of action to help manage Group 2-, 4- and glyphosate-resistant biotypes.

Amplify your glyphosate pre-seed burndown with BlackHawk®, CONQUER® II, GoldWing® and ThunderHawk™. It’s pre-seed power without the complexity.

“We are always keeping our eyes open for new genes and markers for new traits that may become important to barley producers or end-users,” notes Dr. Jennifer Zantinge, the molecular geneticist who leads FCDC’s biotechnology group.

The FCDC’s TR14617 is the first Canadian malting barley variety that is non-glycosidic nitrile (non-GN), a trait in high demand by the malt beverage industry these days.

Glycosidic nitrile can be produced by germinating barley seeds during the malting process. Zantinge explains that GN is an issue because it is a precursor to ethyl carbamate, a carcinogen. It is particularly a concern in malt whisky production. Malt with GN present will produce low levels of ethyl carbamate during fermentation, and if that is followed with distilling, the ethyl carbamate levels will be driven even higher.

“Alcoholic beverages may contain variable levels of ethyl carbamate. Out of concern for public safety, the ethyl carbamate level in alcoholic beverages is regulated in various countries and jurisdictions around the world, including Canada,” Zantinge says.

“With the increasing diversification of the North American malt beverage industry, ethyl carbamate has become an important issue here, especially for malts intended for the production of single malt whisky.”

Some countries with long histories of producing these types of beverages already have non-GN barley varieties.

She notes, “In the UK, ethyl carbamate in single malt Scotch whisky has been effectively controlled by using non-GN barley varieties. Current European varieties that are non-GN were developed by introducing a naturally occurring genetic variation. This non-GN gene variant was first discovered in the late 1990s, in European varieties registered in the late 1960s.”

The FCDC’s interest in the non-GN trait was sparked about five years ago. “At the time, Canada Malting Co. (GrainCorp) was already testing for GN. And Dr. Richard Joy, Canada Malting’s director of malting and technical services for North America, asked us if we had non-GN barley varieties,” Capettini says. “So we started looking for the trait in our germplasm.”

As it turned out, the centre already had some non-GN barley lines.

“After reviewing FCDC barley pedigrees, we found that FCDC breeders had already incorporated varieties with the non-GN genotype as parents. Our biotechnology lab then identified advanced barley lines with a parent carrying that non-GN gene variant. Then we used genetic sequence information to design and apply molecular markers to screen those lines for the variant. Once we had identified

the lines with that variant, we did a chemistry test to confirm that GN was not produced in the germinating seeds,” Zantinge explains.

“We found several of the FCDC’s advanced barley lines that are non-GN and that have good malt quality and the potential to serve as new dual brewing and distilling non-GN varieties.”

One of those lines is TR14617, a two-row, hulled malting barley. TR14617 has many good traits and was approved for registration even before it was known to be non-GN.

“TR14617 is early maturing. It has higher yields similar to CDC Copeland. It has good straw strength, so it has good lodging resistance. It has intermediate resistance to Fusarium head blight and good resistance to smuts and the spot form of net blotch,” Zantinge says. Plus, TR14617 has a set of good malting quality characteristics that are similar to those in CDC Copeland and AC Metcalfe.

“Now, with the discovery of this non-GN trait, we are increasing seed for TR14617 for a commercial malt house plant-scale testing in collaboration with the industry. We expect to have that line offered for commercialization soon,” Capettini notes.

“The whole industry is interested in this trait.”

Zantinge agrees. “Worldwide, the direction for breeding for malt varieties is turning away from GN-producing varieties. In the UK, no more GN varieties are being approved for malt.”

The FCDC’s breeding pipeline has several other advanced nonGN malting lines, so enhanced varieties with the non-GN trait could be on the way after TR14617.

Another example of a new trait in the FCDC’s pipeline is the lowLOX or LOX-less trait. LOX is short for lipoxygenase, an enzyme naturally present in barley. LOX can contribute to beer going stale.

“One of the challenges a brewery must deal with is maintaining the freshness of beer flavour. After beer is bottled and stored, there is a risk over time that it will develop off-flavours caused by oxidation,” Zantinge explains. LOX is thought to be important in the generation of off-flavours described as ‘papery’ or ‘wet cardboard’ –

not a taste that beer drinkers are looking for.

Therefore, malting barley breeders want to knock out or knock down the gene responsible for producing LOX.

However, the FCDC didn’t have any low-LOX or LOX-less lines in its barley germplasm resources. So it decided to collaborate with InnoTech Alberta to use mutation breeding to develop these variants; the FCDC already had a mutation program with InnoTech to develop agronomic traits.

Mutation breeding involves exposing seeds to a treatment that results in spontaneous mutations. Mutated plants with traits of interest can then be crossed into elite breeding lines.

The mutation program produced new genetic lines with LOXless and low-LOX variants. “Pat Juskiw screened these lines and found one line that had pretty good yields. We then used this lowLOX line to cross into our elite malt lines,” Zantinge notes.

Zantinge’s group has sequenced the LOX gene and is able to screen germplasm to look for variations in the sequence. They are in the process of developing markers and chemistry tests to identify lines carrying the low-LOX variant, so they will be able to follow the trait through the lines that Capettini is breeding.

“It is really important for barley producers to have high quality malting varieties that can compete internationally,” Zantinge concludes.

“The FCDC has a strong breeding program with good malting quality combined with good disease resistance packages. Adding speciality traits such as non-GN or LOX-less will provide premium malt for high quality beverages.”

“Our advances in other traits are also continuing. For example, we are working closely with industry to develop barley varieties that have better flavour for specific types of beer or malt whisky,” Capettini notes.

“More than ever, we have to be very integrated in the malting barley value chain. We are ready to respond to the industry’s needs for other new traits, and we expect to continue developing great malting barley varieties.”

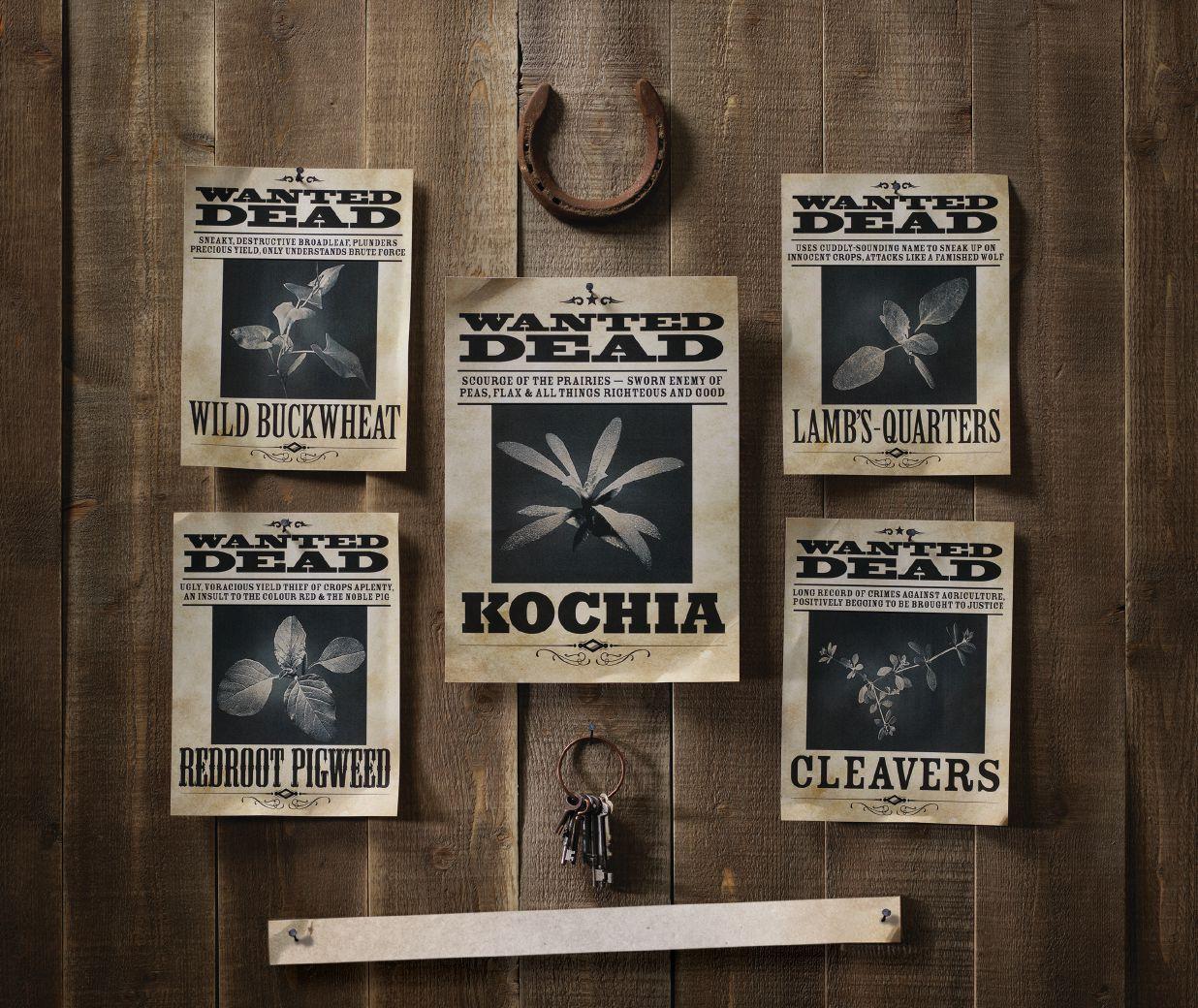

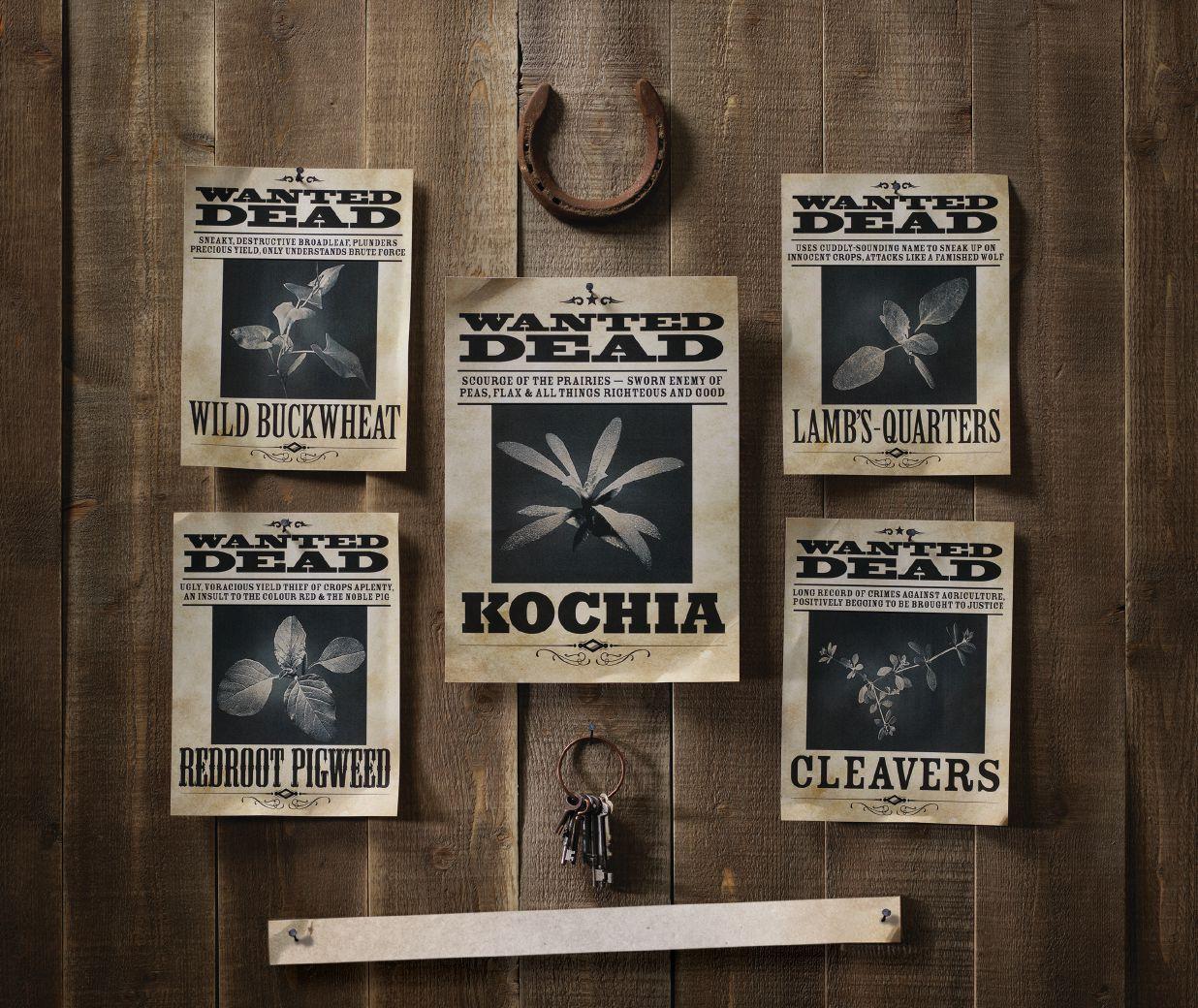

When you apply pre-emergent Authority® 480 herbicide, you’re after kochia and you mean business. But it’s not like the other weeds can jump out of the way. Yes: Authority 480 herbicide controls kochia with powerful, extended Group 14 activity in wheat, peas, flax and more. It also targets redroot pigweed, lamb’s-quarters, cleavers* and wild buckwheat. Authority 480 herbicide. Gets more than kochia. But man, does it get kochia.

WHEAT | FIELD PEAS | FLAX | CHICKPEAS | SOYBEANS | SUNFLOWERS

REWARD OFFERED. GET CASH BACK WHEN YOU BUY AUTHORITY 480 HERBICIDE

Putting together multiple traits to fight the wheat midge.

by Carolyn King

Prairie researchers have teamed up to give spring wheat varieties multi-pronged defences against wheat midge attacks.

“I call the wheat midge one of the ‘big bads’ in wheat in Western Canada,” says Tyler Wist, a field crop entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon.

“Wheat midge populations have the potential to get really big, really fast under the right conditions. The larvae damage the wheat kernels, causing downgrading and yield losses. Very badly infested fields can have 90 per cent yield loss. If not controlled, the wheat midge could cause millions of dollars in losses each year for Prairie wheat production.”

At present, wheat midge-tolerant varieties are the main tool for controlling this potentially devastating pest. But these varieties all rely on a single gene, called Sm1, so there is an ongoing concern that the midge will evolve to defeat this gene.

“The wheat midge’s official common name is the orange wheat blossom midge. The adult is a small orange fly, about the size of a small mosquito. The females lay their eggs on wheat heads. The larvae hatch about five days later. They crawl down to the developing kernel and start feeding on everything that is coming into the kernel,” Wist explains.

“One larva can cause a wheat kernel to shrivel. Three to four larvae, which is pretty typical, will completely destroy a kernel.”

With August rain showers, the mature larvae drop to the ground. They snuggle into the moist soil and form overwintering cocoons. In the spring, once the soil receives about 25 millimetres of rain, the larvae crawl up to the surface, turn into pupae, and in a few days emerge as adults. There is only one generation per year.

“In our region, the midge is really well synchronized to the susceptible stages in our spring wheat, which are Zadoks stages 50 to 59. When spring wheat starts to head out, the adult midges are usually ready to emerge and lay eggs on the heads.”

The plant’s susceptibility to the midge drops off significantly once flowering (anthesis) starts. “In the anthesis and post-anthesis stages, the levels of a couple of acids in the seeds go up. The larvae don’t like those acids and they don’t feed very well on those seeds,” he explains.

“That is actually how the Sm1 gene works. It causes the plant to react to larval feeding by increasing the levels of those same two acids earlier than usual. So the larva stops feeding earlier and starves to death before it has a chance to do much damage.” This

ABOVE:

type of resistance to a pest is called antibiosis, meaning that the plant harms or kills the pest.

Current control options

“The Alberta and Saskatchewan agriculture ministries conduct wheat midge surveys every fall to forecast the risk for the coming year,” Wist notes. “If you are in a high-risk area, consider planting midge-tolerant wheat.”

Over 35 wheat midge-tolerant varieties are available at present, including most western Canadian spring wheat classes and durum, although the trait doesn’t work quite as well in durum.

As a way to slow the development of “virulent” wheat midge

you do best.

back to farming.

When you’ve got three modes of action (Groups 2, 6 and 27), taking on 32 of the toughest weeds is easy. Velocity m3 herbicide is an all-inone product that gives you effective resistance management against Group 1-resistant wild oats and foxtail, and Group 2- and Group 9-resistant broadleaf weeds. Do

populations that have defeated Sm1, the Sm1 varieties are sold as blends, where 90 per cent of the seed in a bag is a midge-tolerant variety and 10 per cent is a midge-susceptible variety.

“Although there are no surveys looking for virulent wheat midges, I think we would know pretty quickly if a field of Sm1 wheat suffered serious midge damage,” Wist notes.

If the midges do eventually defeat Sm1, that would leave insecticides, crop rotation and a native parasitic wasp as the only tools for managing the pest. At present, dimethoate, an organophosphate, is the only available insecticide registered for wheat midge control, with chlorpyrifos on the way out.

Scouting to see if your crop is at the economic threshold for spraying and ensuring proper timing of spraying can both be a challenge. “The adult midges are only active around dawn and dusk. So, shortly before dusk each day when your crop is at Zadoks 50 to 59, you need to go to a few different spots in your field and count the number of these tiny flies flying around at canopy height,” Wist explains.

“The yield threshold is about one midge per five heads, and the grade threshold is about one midge per 10 heads. If you reach those thresholds, you have to take action pretty quickly because you can get a lot of crop damage in just a couple of nights, and the adults only live for about five days. Also, if you wait a little too long, your insecticide application will kill the parasitoid wasp that helps control the midge.”

Wist is one of a group of Prairie researchers involved in two projects to develop more traits for fighting the wheat midge. Their goal is to pyramid these traits – stack them together with Sm1– in wheat varieties. This type of multi-layered defence would be much tougher for the midge to defeat, and all the individual traits to deter the midge would retain their effectiveness much longer.

Alejandro Costamagna, an entomologist at the University of Manitoba, is leading one of these projects, which is about oviposition deterrence (OD, egg-laying deterrence). This five-year Wheat Cluster project is funded by multiple agencies through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership.

Costamagna and Curt McCartney, a wheat geneticist and breeder now at the University of Manitoba, have been working on OD for a number of years. In some of their OD wheat lines, wheat midge egg-laying is reduced by over 60 per cent compared to susceptible plants.

Previous research showed that this deterrence is due to the plant’s odour – the chemical compounds that it releases into the air. The current project is investigating these compounds to better understand how the deterrence mechanism works in the plant and how the compounds affect the insect.

Wist, who is one of the collaborators on the project, says some of their preliminary findings suggest the OD wheat lines smell similar to post-anthesis wheat. “Since post-anthesis wheat is not very good for wheat midge larvae, our working hypothesis is that the female smells the oviposition-deterrent wheat, thinks it would not be good for her offspring, and decides not to lay eggs on it.”

As part of the project, McCartney is determining where the OD trait is located on the wheat genome and developing DNA markers for the trait. These markers will allow breeders to quickly screen the DNA of different wheat lines for the trait, rather than going through labour-intensive laboratory measurements to

see what odour compounds the lines emit.

Wist is leading the other project, which is looking at three other possible traits: awns, hairy glumes, and egg antibiosis. The Alberta Wheat Commission, Sask Wheat, Manitoba Crop Alliance, and Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund are funding the project.

“Awns and hairy glumes are possible mechanical deterrents to the midge. Awns are common on wheat, but hairy glumes are not. There is some evidence that awns might be a mechanical barrier to the midge landing on the wheat head. And some research shows that awns make it hard for aphids to land on wheat, which is another potential bonus. So we decided to include awns in our project. But our main focus is on hairy glumes,” he notes.

A glume is the covering around a spikelet on a wheat head. “The wheat midge female lands on the glumes and usually lays her eggs on them. To decide if it’s a good place to lay her eggs, she’ll probe the glume to pick up chemical cues. Our working hypothesis is that a hairy glume will interfere with her decision-making process and maybe even discourage landing on the plant, so perhaps she will not lay eggs on this hairy wheat.”

The hairy glume possibility came from Rob Graf, the AAFC winter wheat breeder at Lethbridge. A few years ago, he showed Wist a winter wheat line from a century ago that has really hairy glumes. Both Graf and Wist thought those hairs might deter wheat midges.

At that time, Graf had already crossed the hairy glume trait into spring wheat. For Wist’s project, Graf has bred a series of spring wheat lines: some lines have the awn trait, some have the hairy glume trait, some have Sm1, some have two of the traits, and some have all three. Graf is also continuing to cross the trait into other wheats.

“Rob and spring wheat breeder Harpinder Randhawa at AAFCLethbridge came up with an acronym for these lines: SMART wheat,” Wist notes. “The SM stands for Sitodiplosis mosellana, the scientific name for the midge, A is for Alternative, R for Resistance, and T for Triticum, the wheat genus.”

As well, Pierre Hucl, the wheat breeder at the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre, has a hairy spring

wheat line that he is providing for evaluation in the project. Wist says, “Pierre has near-isogenic lines of CDC Teal, which means they differ in just this one trait, so one near-isogenic line has hairy glumes and the other near-isogenic line does not.”

Wist learned about his project’s third trait from McCartney. AAFC researchers had discovered this trait a few years ago in a winter wheat breeding line. Preliminary tests on wheat plants with this trait suggested the female midge continued to lay her eggs on the heads but those eggs died before they hatched.

Wist is really intrigued by this trait because it might be better than Sm1 for preventing kernel damage. “The action of Sm1 kicks in when the wheat midge larva feeds on the grain. So even if the larva dies, that kernel sustains a little bit of damage. But with this other trait, which I’m calling egg antibiosis, the researchers found no larvae in those earlier experiments.”

McCartney has crossed the egg antibiosis trait into spring wheat lines, including some lines that have both egg antibiosis and Sm1 He is in the process of selection and crossing to improve the agronomic characteristics of the lines. And he is mapping the genes associated with egg antibiosis to create markers for the trait.

Wist’s project team is conducting field and lab work, although COVID restrictions halted the lab work in 2020.

The field trials ran in 2019 and 2020 and will continue in 2021. The project team is evaluating the SMART lines, the CDC Teal lines and the egg antibiosis lines – hundreds of different lines in total – for things like agronomic performance, yield and wheat midge damage. The field evaluations are taking place at multiple sites: Hucl has four field sites in the Saskatoon area, Wist has one site at AAFC-Saskatoon, Graf has a site at Lethbridge, and McCartney has two Manitoba sites: one at Morden and one at Brandon in collaboration with AAFC wheat breeder Santosh Kumar. The grain samples from the plots are currently being analyzed in the lab to determine the degree of kernel damage from the pest.

“We’ve got some good wheat lines. For example, some of the SMART lines are beating the check by 6 to 8 per cent in yield. Interestingly, when we compared the different groups of the SMART lines, one thing that really stuck out was that the yield was highest when the plants had both awns and hairy glumes, whether or not the plants also had Sm1. So the high yields weren’t a function of Sm1; they were a function of having awns and hairy glumes,” Wist notes.

“That finding is very preliminary, but we might be onto something. Some research has shown that awns can increase photosynthesis, and perhaps the hairs on the glumes also do that. So perhaps the awns and hairs are helping to increase yield on their own, beyond the yield benefits from deterring the midge. But I’m totally speculating here.”

He adds, “To allow us to take a more in-depth look at the hairy glume trait, we are classifying the lines as: 0 – not hairy at all; 1 – moderately hairy; and 2 – really hairy. Our next task is to put them under a microscope and figure out what makes one plant hairier than another. Are the hairs longer? Are there more of them? Can we quantify that?”

So far, the results from the egg antibiosis lines suggest this trait is more effective when coupled with Sm1. Wist says, “We

had about a dozen lines with both those traits at Brandon in 2019 with no wheat midge damage at all, whereas all the check lines did have damage.”

The project also involves lab bioassays in which the researchers can manage and closely observe the midge-plant interactions in a controlled environment. After being postponed in 2020, the bioassays are now underway, being conducted by Wist’s student Kristy Vavra and Costamagna’s student Bridget White. They are using the wheat midge colonies at AAFC-Saskatoon and the University of Manitoba to conduct the experiments.

These bioassays are critical for providing a more detailed understanding of the different defence mechanisms. For example, the team will be able to confirm whether or not the wheat midge eggs actually hatch on the egg antibiosis lines and to see how the female adults behave when they encounter hairy glumes or awns.

Wist emphasizes that the two wheat midge projects are only possible because wheat geneticists, wheat breeders and entomologists are all working together to find solutions to the “wheat midge scourge.” He is hopeful that this research will help advance the development of Prairie wheat varieties with multiple traits for repelling or killing the midge.

“Imagine if we get all these traits pyramided into a wheat plant. The oviposition deterrent trait makes the plant smell like something the midges don’t want to land on. Then if they do try to land on it, we’ve got awns and hairy glumes to get in their way, and maybe make them choose not to land or not to lay eggs. And if they do lay eggs, those eggs won’t hatch because of egg antibiosis. And we’ve got Sm1 in case any eggs hatch and the larvae start feeding.”

BRUCE BARKER, P.AG CANADIANAGRONOMIST.CA

Wider row spacing can lead to reduced capital costs by eliminating shanks and reduced operating costs with lower draft requirements. But it is a balance with many different factors, including potential issues of seedling fertilizer burn, increased weed pressure and yield and quality impacts.

A four-year study was conducted from 2013 through 2016 at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Research Farm in Indian Head, Sask., to determine the effects of row spacing and rate of nitrogen (N) fertilizer on the establishment, crop development, yield, N uptake, and quality of spring wheat.

The treatments were four row spacings of 10, 12, 14 and 16 inches (25, 30, 35 and 40 centimetres). Five fertilizer nitrogen (N) rates were applied at 18, 36, 71, 107 and 142 pounds of nitrogen per acre (lbs. N/ac), or 20, 40, 80, 120 and 160 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare (kg N/ha) of urea.

A fertilizer blend with an analysis of 14-20-10-10 was sidebanded across all treatments at a rate of 127 lbs. N/ac (143 kg/ ha). The quantity of urea used for the five different N rates was adjusted to accommodate the N present in the 14-20-10-10 fertilizer blend.

The residual N and P prior to seeding ranged from 21 to 42 lbs. N/ac (24 to 48 kg N/ha). The target seeding density of Goodeve wheat was 25 plants/ft² (250 plants/m2), and was seeded into canola stubble with a no-till drill with shank openers. The fertilizer band was located 1.5 inches to the side and 0.75 inches below the seed

Seeding depth was approximately 0.75 inches (19 mm) under the soil surface at the bottom of a 1 to 1.3 inch (25 to 33 mm) groove cut into the soil by the no-till shank opener.

In 2013 and 2015, increasing row spacing decreased plant density. In both of these years, precipitation was below normal, especially in May. There was a linear decrease in plant density from 26 to 20 plants/ft2 as row spacing widened in 2013. In 2015, there was a curvilinear decrease in plant density from 21 to 16 plants/ ft2 as row spacing increased, with the greatest decrease occurring between the 10- and 12-inch row spacings.

Plant density was not affected by N rate. This indicates that as N rate increased, the separation of seed and fertilizer was maintained. Additionally, there was not an interaction between N and

row spacing. This indicates that the reduced plant density observed as the row spacing increased two out of four times (213 and 2015) is due to factors other than N fertilizer rate. The researchers thought that interplant competition, especially under stressful environmental conditions in the seed row, could be the reason.

Row spacing alone did not impact the number of tillers per plant. There was a small linear increase in the number of tillers with increasing N rate, rising from 1.2 tillers per plant at 18 lbs. N to 1.6 tillers per plant at 142 lbs. N. The researchers indicated that this showed that the yield potential was not maximized by just the plant density, and the crop was continuing to respond to increasing rates of N through increased tillering. Increases in tillering were seen in drier years when the crop was compensating for lower plant densities.

In each test year, there was a curvilinear increase in grain yield as the N rate increased. The largest increase occurred in 2014 when grain yield climbed from 38 to 64 bu/ac (2,569.8 to 4,273.3 kg/ha), while the smaller increase occurred in 2016, when grain yield increased from 41 to 52 bu/ac (2,781.3 to 3,518.5 kg/ha). Overall, grain yield increased by the greatest proportion each year when the N rate increased from 37 to 71 lbs. N/ac (40 to 80 kg N/ha).

Row spacing did not significantly affect yield except in the dry year of 2013, when yield decreased as row spacing increased from 10 to 16 inches, with the largest decrease occurring between 12 and 14 inches, when grain yield dropped from 70 to 58 bu/ac (4,705.8 to 3,900.0 kg/ha). This indicates that as row space increased in this drier-than-normal year, other yield components such as increased tillering could not compensate for the lower plant densities that occurred in 2013.

There was no interaction between row spacing and N rate on yield.

These results show that, while there is potential for wider row spacing, there was a 25 per cent probability of lower yield with wider row spacing, which occurred in an abnormally dry year. The limitations of just four site-years of data also create uncertainty about the benefit of moving to a wider row spacing beyond 10 to 12 inches. Producers need to weigh the risk of a potential yield decrease against the cost savings derived by increasing the row spacing.

The growing season comes with unexpected challenges, and if you knew the outcome, making decisions would be easy. We understand you need to optimize productivity and are committed to ensuring your success with best-in-class products and services. The best option for your farm operations begins with Richardson Pioneer.

WITH YOU EVERY STEP OF THE WAY richardson.ca

Because ads don’t deliver yield. For that, you need the latest technology, locally tested. The Brevant™ canola lineup is designed to be flexible, giving you the right agronomic and marketing options for your business. So, get to your local Brevant™ retailer and get the seed you need, without the fluff.

We work hard to make your choice easy.

Visit your retailer or learn more at brevant.ca