TOP CROP MANAGER

WINTER WHEAT SURVIVAL

Don’t rush to make a decision

PG. 10

BARLEY YIELD ROBBERS

On the lookout for new and existing diseases

PG. 6

COW-IMPROVED SOIL BIOLOGY

Custom grazing a win-win for crop and livestock producers

PG. 16

Don’t rush to make a decision

PG. 10

On the lookout for new and existing diseases

PG. 6

Custom grazing a win-win for crop and livestock producers

PG. 16

AAC Viewfield and CDC Landmark VB are two strong standing varieties that bring top-end yields. These short, semi-dwarf varieties have leading sprout tolerance with good colour retention, making for high grain quality.

AAC Viewfield

•Top of class in standability

•Shortest semi-dwarf CWRS

•Good sprouting resistance for high grain quality

•Very high yielding, top of CWRS class across all prairie provinces

CDC Landmark VB

•Semi-dwarf midge tolerant wheat

•Leading standability in a varietal blend

•Good sprout tolerance

•High yielding For more information or to find a local cereal seed expert, visit fpgenetics.ca.

6 | Tracking barley yield robbers

On the lookout for changes in existing disease problems and emergence of new diseases.

by Carolyn King

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Spotlight on influential women by Stefanie Croley

SPECIAL CROPS

14 Does feed barley really require more N than malt? by Bruce Barker

MID-MARCH 2020 • WESTERN EDITION

10 | Use patience to assess winter wheat survival

Don’t rush to make a decision. by Bruce Barker

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

20 Nutrient requirements and Prairie soils by Ross H. McKenzie

PESTS AND DISEASES

26 “Stay vigilant” for wheat stem sawfly: researchers by Julienne Isaacs

STATISTICS CANADA RELEASES SMALL AREA DATA ON FIELD CROPS

The tables show the yield and production data from 2015 to 2019 (where available) for barley, canola, corn for grain, oats, soybeans and all varieties of wheat grown in Canada. Visit TopCropManager.com for the full story.

SOIL AND WATER

16 | Collaborate with cattle for improved soil biology

Custom grazing can be a win-win for crop and livestock producers. by Julienne Isaacs

SOIL AND WATER

28 Perennial weed control in organic rotations by Julienne Isaacs

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

When the teams behind our agriculture brands at Annex Business Media tossed around the idea of a project recognizing women in agriculture, I’ll admit I was hesitant to move forward.

My skepticism wasn’t because I thought women aren’t worthy of recognition, or that we’d have a hard time finding candidates – in fact, it was kind of the opposite. I started working in agriculture in 2013, and since then, I’ve worked alongside a team comprised almost entirely of women (although I’d be remiss not to mention Bruce Barker, our invaluable Western Field Editor, who fits in seamlessly among us). I’ve met, read about and learned from hundreds of women doing great things within the industry. I grew up listening to stories from my grandparents, who were raised on farms in Canada and Italy, and know that the women who came before me played an important role in agriculture too. Traditionally, being a woman in agriculture meant you would take care of the meals, house and family while men worked the fields or tended to livestock. Make no mistake: these tasks were – and still are – important to the success of the farm, but this was a stereotype for many years that wasn’t definitive of every farm wife or daughter. I’m willing to bet my grandmothers and great-grandmothers weren’t the only women helping out in the barn when needed. With time, a woman’s role on the farm has evolved from the traditional interpretation, but the point is that women have been making their mark in this sector for centuries. When is it not considered “new” anymore?

But then I realized this was exactly why we needed to go forward with our initiative. It doesn’t matter that women have been playing an influential role in agriculture for the better part of the last century. What matters is that we have to continue to recognize the importance of women in agriculture. The onus is on us to honour the women who have paved the way for us in the past by spotlighting some of the industry’s brightest lights.

Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture will honour six women from all areas of agriculture – farming, research, consulting, breeding, medicine and everything in between. We know that the work women do on farms and partner farms, in the lab or classroom, or behind the scenes at an office is making a difference to the future of agriculture in Canada, and we intend to highlight their important work and contributions through this program.

Please visit www.agwomen.ca to submit your nomination. Nominees must be 18 years of age or older and must reside in Canada. After the honourees are chosen, we’ll be sharing their stories with you through podcasts and a special digital edition. Stay tuned – you won’t want to miss what’s to come.

1-800-668-2374 Fax: 416.510.6875 or 416.442.2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

SUBSCRIPTION RATES Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept,Oct, Nov and Dec – Canada - $48.50, US - $110 (USD $84.50) Foreign - $131.50 (USD $101) Top Crop Manager East – 6 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Oct, Nov and

Get a more complete and faster burnoff when adding Aim® EC herbicide to your glyphosate. This unique Group 14 chemistry delivers fast-acting control of your toughest weeds. Aim® EC herbicide also provides the ultimate flexibility, allowing you to tank mix with your partner of choice before planting virtually any major crop. Fire up your pre-seed burnoff with Aim® EC herbicide.

Ace Resistant Weeds by mixing Aim® EC with Express® brands and/or Command® 360 ME – receive up to $5.50/ac back.

by Carolyn King

Staying on top of barley disease issues is critical for barley growers, pathologists, breeders and agronomists. “We need to identify emerging and changing disease issues so that we can put in place strategies to mitigate those issues. If we don’t, we could have a potential wreck on our hands, especially if we let the problem get well established rather than managing it at an earlier stage,” says Kelly Turkington, a plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta.

Turkington is leading a Prairie-wide, multi-agency project to provide up-to-date information on barley pathogens. The project involves: surveying barley fields to determine pathogen distribution and prevalence; testing pathogen strains to look for shifts in virulence and other key properties; and tracking emerging concerns like Ramularia leaf spot.

The project runs from 2018 to 2023. Research personnel with AAFC, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (AAF), the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Alberta and the Canadian Grain Commission are collaborating on the project. It is funded under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s Barley Cluster, a joint initiative between AAFC and the Barley Council of Canada. Industry funding is from Alberta Barley, SaskBarley, the Manitoba Wheat and Barley Growers Association, and the Brewing and Malting Barley Research Institute.

“Like any biological entity, barley pathogens will adapt to their environment,” Turkington says. “So the disease spectrum could change quite dramatically depending on the barley varieties that are grown, the cropping practices that are used, and any shifts in the climate that might occur.”

For example, repeatedly growing barley varieties with the same source of genetic resistance, especially in very short rotations, will select for pathogen strains that can infect those varieties. And repeatedly using fungicides with the same mode of action will select for strains that are less sensitive or resistant to that fungicide class. So, once-reliable disease management tools will no longer provide the protection that growers expect.

Turkington has been involved in monitoring barley pathogens since the mid-1990s. “Probably our first experience with quite dramatic shifts in virulence in terms of host resistance occurred with the scald pathogen in the mid-to-late 1990s,” he notes.

“At the time, some barley varieties had excellent resistance to scald, an important leaf disease. However, this was largely based

Ramularia leaf spot has been spreading rapidly to many countries, including Ireland, where this photo was taken. The project team is checking to see if the disease has arrived in Western Canada.

on major single-gene resistance [and pathogens can more easily overcome single-gene resistance than resistance based on multiple genes]. When those varieties were grown continuously, the scald pathogen adapted to the resistance source and the varieties’ reaction to scald changed within two to three years from being highly resistant to being intermediate or, in some cases, quite susceptible.”

In the 2010s, Turkington and his University of Alberta colleagues Stephen Strelkov and Alireza Akhavan saw similar shifts with net blotch, another leaf disease. Likely, continuously growing the same resistant variety or using short rotations resulted in a shift

in the pathogen’s virulence.

As well, Akhavan and colleagues found that the net blotch pathogen was becoming less sensitive to propiconazole, an older triazole fungicide, and to pyraclostrobin (Headline), a strobilurin fungicide.

“Propiconazole was a common fungicide and tended to be a little cheaper, so maybe it was used more frequently and especially in short-rotation barley production. And often it was applied at a herbicide timing, and sometimes at a half rate. Invariably that did not provide sufficient control of net blotch. So, the farmer would need to go back in with another application at flag leaf emergence or head emergence,” Turkington explains.

“The strobilurins tend to be at very high risk of fungicide resistance development. So, you’ll often see a wholesale shift from the pathogen being fully sensitive to being fully insensitive or resistant to that particular active. We’re not seeing that type of dramatic shift with the net blotch pathogen, but we’re seeing indications that we need to be cautious [with applying these products].”

The current project’s primary objective is to assess the prevalence and spectrum of barley diseases that are present in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

For this work, the project team is collecting diseased leaf samples from about 30 to 50 barley fields per province per year. The survey mainly targets commercial barley fields. In addition, Kequan Xi and Krishan Kumar with AAF in Lacombe are monitoring the disease nurseries that AAF’s Field Crop Development Centre uses for evaluating disease response in barley breeding materials.

The project team analyzes the leaf samples in the lab to identify the pathogens, and also conducts detailed testing on some key leaf pathogens. In particular, as part of a PhD project at the University of Alberta, graduate student Dilini Adihetty is evaluating the spot blotch pathogen for variation in virulence, variation in

genetic characteristics at a molecular level, and in fungicide sensitivity. And the project team is assessing the scald pathogen and the net blotch pathogen for changes in virulence on different barley varieties.

Why focus on leaf pathogens? “Traditionally the biggest barley disease issues in terms of yield loss and impacts would be the leaf diseases,” Turkington explains. These diseases can cause yield losses of more than 30 per cent in susceptible barley varieties when conditions favour disease development.

The three major leaf diseases in Western Canadian barley are scald (caused by Rhynchosporium secalis), net blotch (Pyrenophora teres) and spot blotch (Cochliobolus sativus).

“Scald tends to be an issue in cooler, wetter regions. So traditionally we find it in central and northern Alberta up into the Peace Region, and occasionally in northwestern Saskatchewan,” he says.

Net blotch has a net form and a spot form. “As the name implies, the net-form net blotch lesions can have a netted appearance, whereas the spot form tends to produce oval or elliptical brownish lesions.”

During the past few decades, these two forms have switched back and forth in terms of their relative predominance. The netform is more common at present. “There seems to be a background level of intermediate to maybe higher levels of resistance to spotform net blotch [in our current barley varieties],” Turkington notes.

“Spot blotch has traditionally been more of an issue in the central to eastern Prairies. But over the last 10 years or so, we have started to detect it at increasing levels in our central Alberta surveys.”

The spot blotch fungus can infect more than just the leaves. “The fungus can move quite readily from the leaf tissue to the developing barley kernels where it causes kernel smudge. Kernel smudge may have implications for acceptability for malt status or downgrading due to grain discoloration,” Turkington explains. “Also, if you plant that infected seed, the pathogen can be quite aggressive on seed germination, seedling growth and stand establishment. Plus this fungus is a cause of common root rot.”

The project team is also taking a close look at stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis) in barley, which is a potentially emerging issue in the western Prairies.

“In some other major barley-producing areas, stripe rust in barley can be a devastating disease, causing major yield losses in susceptible varieties and where the disease is not adequately controlled with fungicides,” Turkington explains.

There are signs that the disease could become an issue in Alberta. “Over the years, Kequan and Krishan have documented quite significant levels of stripe rust primarily in their disease nurseries and very occasionally in commercial barley fields. Also, they sometimes see pathotypes of the stripe rust pathogen that have dual virulence on wheat and barley. These dual types tend not to be as common as the barley type, which is more adapted to barley, and the wheat type, which is more adapted to wheat.”

Stripe rust requires a living host to survive, so it doesn’t usually overwinter on the Prairies. Typically, the pathogen’s spores are carried by the wind from the U.S. into Canada. “For Alberta, most of the stripe rust inoculum comes from the Pacific Northwest –Washington State, Oregon and northwestern Idaho. If you think about stripe rust moving into the Lethbridge area, a parcel of air going over eastern Washington State can reach Lethbridge in less

than half a day,” he says.

“The central to eastern Prairies can find stripe rust in wheat, but not so much in barley. Most of their inoculum comes from Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska.”

Turkington thinks that a key reason why barley stripe rust is not a serious issue at present in Western Canada is that winter barley is not grown on the Prairies and very little winter barley is grown in the stripe rust source regions in the U.S. However, that could change if, for example, breeding advances result in winter barley varieties that are able to survive the harsh Prairie winters.

According to Turkington, good sources of stripe rust resistance are available in the barley germplasm and in some of the current barley varieties. So, if monitoring efforts show that barley stripe rust is starting to become a concern, then growers and breeders have some options.

The team is also determining the prevalence and distribution of a new disease: Ramularia leaf spot (Ramularia collo-cygni).

could become an issue here.”

Ramularia may already be in Western Canada. He explains, “Over the years, we have seen symptoms that appear to be characteristic of Ramularia, but it is a difficult pathogen to isolate in the lab using traditional agar plating. So Xiben Wang at AAFC-Morden and Sean Walkowiak with the Canadian Grain Commission are using molecular detection techniques to confirm the presence of this pathogen.”

In 2018, the survey detected a few potential occurrences of Ramularia infections, and Wang and Walkowiak are now checking those isolates as well as processing plant samples from 2019.

This monitoring initiative is providing crucial information that will help plant pathologists, barley breeders and others in developing effective disease management strategies for growers.

But Turkington emphasizes that disease-monitoring is just as vital at the farm level.

“Growers and their crop consultants need to stay on top of the

Don’t rush to make a decision.

by Bruce Barker

Stay calm and carry on – with spring seeding. That’s the advice of seasoned winter wheat growers when it comes to assessing winter wheat survival in the spring.

“I encourage farmers to leave their winter wheat until they are about half-done seeding their spring cereals before making a final assessment on winter survival. I’ve seen inexperienced farmers wanting to spray out the winter wheat before it has even started to grow,” says Paul Thoroughgood, farmer and Ducks Unlimited agronomist in Moose Jaw, Sask. “You don’t want to make a rash decision.”

In Enchant, Alta., Greg Stamp of Stamp Seeds has winter cereals as a regular part of his rotation, including winter wheat, fall rye, hybrid fall rye and winter barley. He has had a few occasions where winterkill has been an issue. Winterkill is usually a result of snowmelt that freezes on top of seed rows. Most of the time, this type of winterkill is restricted to low spots and isn’t too much of a concern. However, one year a field with flat topography didn’t drain and the majority of the seed rows became iced over, so it had to be reseeded.

“We start looking at the fields right before seeding, but we don’t

The best o ence is a good defense. With Prospect™ herbicide, your canola will have the best start possible. Prospect tank mixed with glyphosate will give you game-changing performance against the toughest broadleaf weeds, including cleavers and hemp-nettle.

Ask your retailer or visit Corteva.ca to learn more.

make any decisions until about halfway through seeding. Winter wheat comes back better than you would think,” Stamp says. “Put a flag in the field so you can go back to the same location each time you go out.”

Stamp says an especially important management tool for winter wheat is to use a fungicide/insecticide seed treatment in the fall to help with winter survival. Research by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada scientist Brian Beres showed the value of the practice. “We have had very good success with the dual seed treatment. There really is something to it,” Stamp says.

Thoroughgood says there are several ways to assess winter wheat survival beyond waiting for the seedlings to grow. The first is to use a bag test early in the spring. Dig up a few winter wheat plants, wash the soil from the roots, and place them in a zip-top bag with a wet paper towel. Leave the bag in a warm, sunny place for seven to 10 days and assess for new growth. Healthy plants will be developing white roots. Black roots may mean the plants are dead and you need to spend more time monitoring the field.

Another way to assess survival is to simply dig up some plants, leaving the soil root ball intact, and let it grow inside in a warm, sunny area. After a week to 10 days, wash the soil from the roots and look for healthy, white roots.

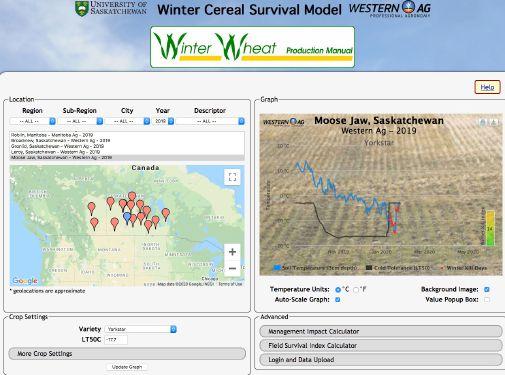

Web-based forecasting tool

Western Ag Professional Agronomy, in collaboration with the University of Saskatchewan, built a web-based “Winter Cereal Survival Model” to help growers track winterkill days. The model is based on winter cereal research by emeritus professor Brian Fowler at the University of Saskatchewan, and is freely available to farmers.

Currently, 15 weather stations generate data for the model with temperature probes placed one inch deep into the soil. Soil temperature is monitored throughout the fall, winter and spring. The cold tolerance of different winter cereal varieties is built into the computer, as measured by LT50 (lethal temperature at which 50 per cent of plants die). Farmers can select a location from the map nearest to their farm, select their variety and see if there have been any winterkill days at that location.

For example, in Moose Jaw during the 2019-20 winter season, Yorkstar, an old variety with poor winter hardiness that is no longer grown in Western Canada, would have had at least 12 winterkill days in late January and early February – showing the odds of winter survival to be poor. Conversely, at the same location with CDC Bueto, rated Very Good for winter survival, no winterkill days had occurred.

Thoroughgood says winter wheat survival is like a boxing match. Rarely does one deep freeze event deliver a knock-out blow to wheat. But as with the example of Yorkstar, many body blows can eventual knock out the plant.

“The model is a tool that farmers can use to help assess their winterkill risk. In a worst-case scenario, like on my farm this year, where I have winter wheat seeded into lentil stubble and no snow, you can go in and see if there have been winterkill events,” Thoroughgood says. “It can take some of the worry out of the cold weather events we have been having.”

With the model, Thoroughgood says that farmers can also look at the different varieties and weather data going back to 2004. This can help them assess the winterkill risk of different varieties at locations near their farm.

The optimum plant stand for winter wheat is over 20 plants per square foot (plants/sq. ft.), depending on where you farm. In Enchant, Stamp likes to see 40 plants/sq. ft. on irrigated land, and he gets concerned when densities fall below 20. On dryland, he likes about 30 plants/sq. ft.

Saskatchewan Crop Insurance will pay out an “establishment benefit” if plant stands are less than five plants/sq. ft. Farmers can choose to take the benefit if the plant stand is between five and seven plants/sq. ft.; above seven plants is considered “established” with no benefit payout. In comparison, the establishment benefit for hard red spring wheat kicks in if there are fewer than 7.8, farmer’s choice at 7.8 to 12.2, and established at more than 12.2 plants/ sq. ft.

“Winter wheat has the ability to tiller much more than spring wheat, so lower winter wheat plant populations can still produce high yields,” Thoroughgood says.

The Western Winter Wheat Grower Guide, produced by the Western Winter Wheat Initiative, indicates that the optimum plant stand is over 20 plants/sq. ft. However, 10 to 15 plants/sq. ft. can still produce a profitable crop.

Thoroughgood says that overall, winter wheat survival in Western Canada is surprisingly just as good as the biggest winter wheatgrowing state in the U.S., Kansas, at around 91 per cent survival.

“Often, the perceived risk of winterkill is much higher than reality,” Thoroughgood says. “Including winter wheat in prairie Canadian crop rotations provides many benefits that farmers should consider.”

Multiple modes of action deliver both fast burndown and extended residual.

Just when you thought the best couldn’t get better. New Heat® Complete provides fast burndown and extended residual suppression. Applied pre-seed or pre-emerge, it delivers enhanced weed control and helps maximize the ef cacy of your in-crop herbicide. So why settle for anything but the complete package? Visit agsolutions.ca/HeatComplete to learn more.

Always read and follow label directions. AgSolutions, HEAT, and KIXOR are registered trade-marks

Research shows the most economic rate of N for feed is often not higher than it is for malt.

by Bruce Barker

The general recommendation of applying more nitrogen (N) on feed varieties has not been supported by recent studies. Malt producers are usually more prudent with N because too much may result in excessive protein (above 12.5 per cent) and rejection by maltsters.

“Excessive grain protein in malt barley is not desirable as it results in cloudy beer, and no one wants that,” says research assistant Heather Sorestad with the East Central Research Foundation (ECRF) and Parkland College in Yorkton, Sask.

To compare the N management between feed and malt barley, Sorestad and ECRF/Parkland College research manager Mike Hall partnered with the seven other Agriculture Applied Research Management (AgriARM) foundations across Saskatchewan in Scott, Yorkton, Redvers, Indian Head, Melfort, Prince Albert, Outlook and Swift Current. The research was conducted from 2017 through 2019, with three locations in 2017, seven in 2018 and eight locations in 2019. It was financially supported by Saskatchewan Agriculture’s ADOPT program and SaskBarley Development Commission.

Sorestad says the Saskatchewan Crop Planning Guide reinforces recommendations to apply more N to feed barley. It assumes producers in the Black soil zone apply 99 pounds of nitrogen per acre (lbs.

N/ac) to achieve a 93 bushel per acre (bu/ac) crop of feed barley. In contrast, the guide assumes only 81 lbs. N/ac are applied to achieve 76 bu/ac of malt barley.

In each of the three years of the AgriARM research, the response to N fertilizer of high-yielding CDC Austenson feed barley was compared to a malt barley variety. In 2017, AC Metcalf malt barley was grown at three AgriARM locations, and N rates of 40, 80 and 120 lbs./ac were applied. In 2018, CDC Bow malt barley was grown at seven locations with 50, 75 and 100 lbs. N/ac. In 2019, CDC Austenson was compared to AAC Synergy with soil plus fertilizer N at 80, 120 and 160 lbs./ac.

The Saskatchewan Varieties of Grain Crops 2019 uses AC Metcalf as the check variety for comparative purposes with other malt and feed varieties. CDC Bow malt barley yields 111 per cent of AC Metcalf, while AAC Synergy yields 118 per cent. CDC Austenson feed barley is rated at 118 per cent of AC Metcalf in Areas 1 and 2, and

TOP: High-yielding malt barley varieties can compete with feed barley.

121 per cent in Areas 3 and 4, similar to AAC Synergy malt barley. In total, 18 location years were analyzed, but some trials were nonresponsive to fertilizer N. Yield response curves were developed for each barley variety; malt barley protein content was also assessed. The most economical rate of N for feed and malt barley was calculated at the point where one dollar per acre of N applied will return one dollar of revenue. This calculation assumed N at 50 cents per pound and prices of $3.70 per bushel for feed and $4.68 per bushel for malt.

Overall, the yield response curves to N were similar between feed and malt barley varieties. The most economical rate of N varied by year and variety. Environment played a large role in protein content, with higher protein content in drier locations. For example, in 2018 in Scott, the yield of CDC Bow malt barley was 51 bu/ac at the lowest N rate of 50 lbs./ac, but the protein was already at 12.9 per cent –usually too high to be accepted by maltsters.

Conversely, at sites with high yield, protein content was lower than 12.5 per cent at the most economical N rates. Results from Scott in 2019 found that the most economical soil plus fertilizer N was 155 lbs./ac, with a yield of close to 100 bu/ac and protein content less than 12.5 per cent. The most economical rate for CDC Austenson was 123 lbs. N with a similar yield. In Yorkton in 2019, both CDC Austenson and AAC Synergy achieved very high yields of more than 140 bu/ac at a soil plus fertilizer N rate of at least 160 lbs., while protein content remained below 12 per cent.

Overall, three site-years found the most economical rate of N for malt and barley differed only slightly. Two site-years showed the most economic rate of N was substantially higher for malt than feed barley. However, there was one site-year where the most economical

rate for malt was much lower due to protein issues. In two trials, comparisons were not possible because the yield response was quite steep for both varieties, with the most economic rate of N well beyond the rates investigated in the study.

Hall says there wasn’t a lot of evidence to suggest the most economic rate of N for feed barley is higher than malt, even if the price for malt and feed were the same. It didn’t matter if the comparison was with a high-yielding or low-yielding malt variety because their yield responses to N were both similar to feed. However, he says that the overall economics of the low and high-yielding malt varieties aren’t the same. A low-yielding malt variety like AC Metcalf will generate less income compared to the higher yielding AAC Synergy, assuming both are accepted for malt.

“In fact, since AAC Synergy yields as well as CDC Austenson, there may be less reason to grow a feed variety. I should add that the bushel weight for CDC Austenson averaged 50.4 lbs. per Winchester bushel in our study, which was better than 48.6 lbs. per Winchester bushel for AAC Synergy. The goal is to maintain bushel weights above 48 lbs. per Winchester bushel for feed barley,” Hall says.

Hall cautions that malt barley growers should check with their maltsters to ensure that they are contracting AAC Synergy or other malt barley varieties. “I’m not going to be bold enough to say you should be applying more N to your malt barley. The proper rate is something you’ll have to determine based on your past experiences and anticipated environmental conditions,” Hall says. “However, I will suggest that if your malt barley protein is above 12 per cent, then feed barley in that same field would not have benefited economically from a rate of N higher than what you applied to the malt.”

If you’re still using glyphosate alone for pre-seed burndown, or choosing a Group 2 herbicide as a tank-mix partner, you may not be getting the early weed control you need. Nufarm’s burndown products have multiple modes of action that deliver the power you need to stay ahead of tough weed pressures – giving your canola, cereal, pulse and soybean crops a cleaner start in the spring.

Amplify your pre-seed weed control with Nufarm. Ask

by Julienne Isaacs

With a dry, cold spring, a hot, dry summer and a wet harvest season, 2019 was a disastrous year for Manitoba hay production, says Mary-Jane Orr, general manager at Manitoba Beef and Forage Initiatives. In the face of feed shortages, some farmers were forced to disperse their herds.

Under extreme weather conditions, innovative approaches are required for livestock producers to feed their animals, Orr says.

One collaborative approach has benefits for cattle and grain farmers alike: custom grazing fall cover crops. For livestock producers, such an arrangement can be part of a diversified strategy for maintaining herd size. For grain farms, adding livestock can improve land use efficiency and soil biology.

Jillian Bainard, a forage research scientist for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Swift Current, says that as regenerative agriculture principles hit the mainstream, interest has grown in custom grazing in Western Canada. During a webinar for the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) last March, Bainard asked

participants whether they’d have interest in partnering with another producer to utilize cover crops for feed.

Thirty-two per cent of respondents selected “Yes – I would like to work with another farmer to offset some of the operational needs of either the cropping or animal needs.” (Sixty-eight per cent responded that they would rather use their own resources.)

Bainard is the lead on a new integrated crop-livestock study that aims to analyze how grazing annual forage cover crops compares to a typical annual crop rotation without cattle. The study, which is funded by AAFC, BCRC and Manitoba Beef Producers, will look at how these diverse systems impact soil health (for example, nutrients, microbial communities and soil aggregation) as well as weed communities and general productivity. Bainard’s collaborators will also consider economic outcomes – whether or not crop-livestock integration can improve a farmer’s bottom line.

Hard-to-kill grassy weeds are no match for EVEREST® 3.0. An advanced, easier-to-use formulation delivers superior Flush after flush™ control of wild oats and green foxtail. In addition, EVEREST 3.0 is now registered for use on yellow foxtail*, barnyard grass*, Japanese brome and key broadleaf weeds that can invade your wheat and rob your yields. You’ll still get best-in-class crop safety and unmatched application flexibility. Talk to your retailer or visit everest3-0.ca to learn more.

*Suppression alone; Control with tank-mix of INFERNO® WDG Herbicide.

Always read and follow label directions. UPL, Flush after flush, EVEREST and INFERNO are trademarks of a UPL Corporation Limited Group Company. ©2020

“With growing trends in regenerative agriculture or conservation agriculture, we’re really recognizing just how much we can improve our soil through sound cropping practices and keeping cover or relay crops growing as long as possible,” Orr says. “There are a lot of good reasons to keep plants growing longer. But then what do you do with that cover crop, if it’s in addition to your cash crop? Do you spray it, do you till it back in?

“That’s where livestock integration has a huge window of opportunity to increase your return on investment if you’re seeding cover crops.”

Derek Axten runs a diversified grain operation in southern Saskatchewan. For a few years, Axten has been working with neighbours Ryan and Leanne Thompson, who run a beef operation called Living Sky Beef, to get cows on his land through the fall and winter.

Axten supplies fencing materials that the Thompsons install and maintain; the Thompsons pay Axten in cents per animal unit.

Orr says the biggest limiting factor for many producers interested in custom grazing is the capital investment in fencing and clean water infrastructure – every pasture has to have either a dugout or a pump and trough – but Axten says much of the infrastructure already existed on his land due to the number of mixed farms in the area.

The Axtens’ farm was originally mixed, and they were already

used to fall-grazing their land, he says, so it wasn’t a big leap.

That’s not to say it isn’t a complex arrangement, and Axten cautions that for partnerships like theirs to work there has to be good communication from the outset.

“I think where these things go wrong is that there’s no real clear communication,” he says. “Everybody likes to assume.”

The Thompsons plan their year’s grazing in the spring, so if Axten needs to make changes to the arrangement he lets them know then.

The extra administrative work is worth it from Axten’s perspective.

“If we can have livestock on our land it’s definitely better,” he says. “They’re cycling nutrients and cleaning up messes, weeds around the outside of fields and around rock piles. They’re making use of things we wouldn’t make use of. And if the combine has made a pile, the cows level that out too.

“If we seed a fall-seeded cover crop and graze it, we typically get our seeding and seed costs back. As long as we manage the amount of time the cows are out, I think it’s a win.”

Don Flaten, a professor in the department of soil sciences at the University of Manitoba, says that from a nutrient cycling standpoint, crop-livestock integration makes a lot of sense.

Cattle only remove a small portion of the nutrients they eat from the field. In research Flaten’s team has done, they’ve found

that cows remove less than five pounds of phosphorus per acre, even with an intensively managed herd of background steers.

“At least 90 per cent of the nutrients that go in the front end come out the back,” he says. “This is one of the benefits of a grazing system, that you leave a lot of nutrients on that field and remove relatively small amounts of nutrients compared to the complete harvest of a crop in the form of hay or grain.”

But crop-livestock integration doesn’t just have to be custom grazing. Flaten has seen crop and livestock producers swap land for short-term periods, so the livestock producer can grow perennial forages and apply manure on the crop producer’s land, and the crop producer can later use that land, which now has an improved fertility base, for canola and wheat.

A dairy farm near Rosser, Man., that Flaten has worked with has swapped land with grain and oilseed neighbours. More typically, many grain farmers incorporate liquid manure from local livestock operations onto annual cropland.

How do grain farmers find livestock farmers to partner with?

Flaten says in Western Canada that often depends on community relationships and the level of trust between neighbours. But for neighbours who don’t know each other well, a formal contract can be a helpful starting place in negotiating the terms of the agreement.

Further afield, South Dakota has a system called the South Dakota Grazing Exchange, which shows a map overlay with fields available for grazing, as well as livestock producers looking for grazing sites. No such tool is currently available in Western Canada but Orr says that, given enough interest, it may eventually become a reality.

For now, Orr recommends that grain farmers without immediate livestock neighbours who are interested in working with a livestock operation should get in touch with regional directors of the provincial beef associations or with provincial agriculture ministry representatives. For general information on these systems, researchers like Bainard are a good resource.

Axten says farmers might be surprised by how profitable custom grazing can be for their operations. “The biological benefits aside, it can add up to a lot.”

As a grower, you face many challenges throughout the growing season. Protecting your seed’s potential from the start means your crops can emerge healthier and stronger. That’s why more growers trust Raxil ® PRO, the #1 selling cereal seed treatment brand ten years running1. When your seeds emerge stronger, so do you.

EmergeStronger.ca 1 888-283-6847

#AskBayerCrop

@Bayer4CropsCA

12019 BPI Report – Cereal Seed Treatments Always read and follow label directions. Bayer, Bayer Cross, BayerValue™ and Raxil® are trademarks of the Bayer Group. Bayer CropScience Inc. is a member of CropLife Canada. © 2020 Bayer Group. All rights reserved.

600 AC. OF RAXIL PRO SAVES YOU 5%!

Maximize your savings on Raxil PRO, and everything else you need for a breakthrough season. See how the rewards add up at GrowerPrograms.ca

Phosphorus, potassium and sulphur management for cereal crops.

by Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P.Ag.

Cereal crops require careful attention to nutrient requirements to develop a sound, balanced fertilization program and achieve optimum yields. Nutrient uptake and removal vary with environmental conditions, soil nutrient availability, crop type and cultivar.

Phosphorus (P)

About 80 per cent of Prairie soils are marginal or deficient in plantavailable soil phosphorus (P) for cereal crop production. Phosphorus is one of the most limiting soil nutrient in cereal production, second only to nitrogen (N).

Adequate P results in rapid crop growth, earlier maturity and higher yield. An adequate supply of available P in soil is associated with increased root growth, which means roots can explore more soil for nutrients and moisture. By the time a cereal crop has attained about 25 per cent of its total dry weight, up to 75 per cent of the total P requirement has been taken up. A good supply of P is important during the early growth stages of cereals.

Cereal crop response to applied P fertilizer depends on the level of plant-available P already in the soil, as well as soil moisture and temperature conditions early in the growing season.

The level of plant-available P in soil, as measured by a soil test, varies with the extraction solution method used by the laboratory. The modified Kelowna soil test is typically used in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Alberta research identified this as the best method for predicting P crop response and is the only recommended method in Alberta. The Olson method, also referred to as the sodium bicarbonate method, is the recommended method for Manitoba. The Bray method used to determine soil P has not been calibrated to soils in Western Canada, and is not an endorsed method for making fertilizer recommendations.

Soil P levels have gradually increased in some fields over the years because of repeated annual P fertilization or manure application. As a result, crops grown on these soils are less responsive or

ply the ppm value by two to convert to lb. P/ac.

Approximate nutrient uptake of a 60 bu/ac wheat crop or 80 bu/ ac barley crop. Uptake varies depending on crop type, cultivar and environmental conditions during the growing season.

(SOURCE: R.H. MCKENZIE)

not responsive to P fertilizer application.

In recent years, many Prairie farmers have not been applying enough P fertilizer to replace crop removal, resulting in a decline in soil test P levels in fields for many farmers. It is important to test soil for plant-available P and apply sufficient P fertilizer to replace amounts removed in harvested crops to maintain good soil P levels.

When environmental soil conditions after planting are cool and wet, cereals tend to be more responsive to P fertilizer versus when soil conditions are warmer or dry. Fields that are direct-seeded in early spring tend to be cooler and wetter, so soil P tends to be less available, resulting in greater crop response to P fertilizer.

Alberta research suggests that placement of P with the seed is often slightly better than banded P, and both methods are superior to broadcast-incorporation of P fertilizer when soil test P level is low.

Table 2 provides general phosphate (P2O5) fertilizer recommendations for wheat using the modified Kelowna method. Table 3 provides the probability of a greater than two and five bushel per acre (bu/ac) yield response when following the recommended P2O5 from Table 2 (See Alberta Agriculture Agdex 542-3 for barley recommendations). Soil test P levels in Table 2 are in pounds per acre (lb./ac). When a soil test for P is reported in parts per million (ppm) for a zero- to six-inch (zero- to 15-centimetre) soil sample depth, multi-

When soil test P levels are medium to high, and significant P fertilizer has been applied in the past 10 to 20 years, an annual maintenance application of phosphate fertilizer can be used to meet crop requirements and replenish soil P that is removed.

Up to 50 lb P2O5/ac (55 kg P2O5/ha) can be safely seed-placed with wheat or barley if seedbed utilization (SBU) is 10 per cent and no other fertilizer is seed-placed. To obtain best P fertilizer efficiency, adequate rates of N and other required nutrients must also be available to the crop, preferably in a side or mid-row band away from the seed.

Cereal crops take up nearly as much potassium (K) as N and therefore have a high K requirement. However, only about 20 per cent of the K taken up is contained in the seed, while the remaining K in crop residue is normally returned to the soil. Potassium in the plant residue remains in inorganic form and is fairly quickly returned to plant-available form in the soil.

About 75 per cent of Prairie cultivated soils have extractable soil K levels in the range of 300 to more than 800 lb. K/ac (330 to 900 kg/ha) in the top zero- to six-inch (zero- to 15-cm) depth, which is more than adequate to achieve optimum cereal crop production. About 25 per cent of Prairie soils are marginal to deficient in soil K.

Cereals usually do not respond to K fertilizer when soil test levels are greater than 250 lb K/ac (280 kg K/ha) in the zero- to six-inch (zero- to 15-cm) depth. On fields that test less than 250 lb K/ac, or on sandy soils or intensively cropped fields, K fertilizer may be necessary. General potassium fertilizer recommendations for wheat are summarized in Table 4.

Potassium fertilizers are more efficient when seed-placed or banded. However, if phosphate and K fertilizer are both placed with the seed, germination and emergence can be affected. If K fertilizer is required, rates up to 25 lb. K20/ac using potassium chloride (0-0-60) can be placed with the seed, but no more than 30 lb. P2O5/ac should Table 1.

* Seed-bed soil moisture conditions at seeding D = 25%; M = 50%; W = 75% of field capacity.

Phosphorus fertilizer recommendations for wheat at various soil test levels and soil zones based on the modified Kelowna P test method. All soil P calibrations are based on a zero- to six-inch (zero- to 15-cm) depth. Recommendations are given for three soil moisture levels.

Three different powerful herbicide Groups have been combined to make one simple solution for cereal growers.

Infinity® FX swiftly takes down over 27 different broadleaf weeds, including kochia (up to 15 cm) and cleavers (up to 9 whorls). And if you’re worried about resistance, consider this: you’re not messing with one wolf, you’re messing with the whole pack.

Approximate probability of a greater-than 2 bu/ac and 5 bu/ac wheat response to phosphate fertilizer when following recommendations from Table 2.

SOURCE: MCKENZIE AND MIDDLETON. 2013. ALBERTA AGRICULTURE AGDEX 542-3, PHOSPHORUS FERTILIZER

be seed-placed with the K fertilizer when using a 10 per cent SBU. If higher amounts of K are needed, the K should be side- or mid-row-banded at seeding or banded before planting to avoid seedling injury.

Cereal crops have a moderate requirement for sulphate-sulphur (SO4-S). Unlike N and P, which are both readily translocated within plants, sulphate-S is immobile. Consequently, cereals require a constant supply of available sulphate-S throughout the growing season. Sulphur is an important constituent of seed protein.

Top soil and subsurface soil sulphate-S levels affect crop growth. The zero- to six-

Table 4.

inch and the combined zero- to 24-inch depths must both be considered to determine if S deficiency is a potential concern. Soil sulphate-S must be adequate in both the zero- to six-inch and zero- to 24-inch depths. It is possible to have adequate S in the combined zero- to 24-inch depths but still be deficient in the zero to six-inch depth.

The general S fertilizer recommendation for cereal production is 10 to 25 lb. S/ ac (11 to 27 kg/ha actual S), using a sulphate fertilizer source such as ammonium sulphate (21-0-0-24), when soils are low in S. Sulphate fertilizer effectively corrects S deficiency. Often, soils in the Brown and Dark Brown soil zones have adequate sulphate-S

Potassium fertilizer recommendations for wheat in Alberta. All soil K calibrations are based on a zero to six-inch (zero to 15-cm) soil depth.

SOURCE:

in subsoil for cereal crop production. But, if soil test sulphate-S is low (<15 lb. S/ac) in the zero- to six-inch depth, it is wise to add 10 lb. SO4-S/ac to ensure S deficiency does not occur in early stages of growth.

Ammonium sulphate fertilizer is rapidly available and can be applied in various ways. When sulphate-S is side-banded near the seed or seed-placed, uptake efficiency tends to be best. Banded S fertilizer may favour crop growth versus weed growth, since banding places the fertilizer close to crop roots. Ammonium sulphate fertilizer has a relatively high salt index. Only small amounts can be safely seed-placed. If higher rates of P fertilizer are seed-placed, then placement of ammonium sulphate in a side- or mid-band is best.

If detected early enough, S deficiency in cereals can be corrected by in-crop broadcasting of ammonium sulphate. The greatest risk from using soluble sulphate fertilizers occurs on sandy soils subjected to heavy rainfall, which may cause sulphate-S to leach below the rooting zone.

Elemental sulphur (S°) fertilizer can also be used, but must be used correctly to be effective. Elemental S° has advantages because of lower cost, high analysis and lower transportation costs. The disadvantage of this fertilizer is that elemental S° fertilizer must be oxidized by soil microbes to convert to sulphate. The rate of conversion from S° to plant-available sulphate depends on the particle size, as well as the method of application. Often it may take several months for S° to become plant-available, or even years if particle size is large.

For best management, an S° product should have a small particle size (<75 microns) and should be surface broadcast without incorporation, ideally in the fall the year before benefits are needed. Elemental S° with a small particle size, broadcast on the soil surface, will easily disperse on the soil surface due to rainfall and freeze/thaw action. Then it can be incorporated into the soil, allowing soil microbes to oxidize and convert to sulphate. Banding or broadcasting followed by immediate incorporation is an inefficient method of applying S° and is not recommended, because application prevents S° granules from dispersing. Liquid suspension S° products are being developed for spray application, with very small micron size. Producers must use care in deciding whether to use ammonium sulphate fertilizer versus elemental S°, and should seek advice from an experienced agronomist. Table 3.

Climate will be more favourable to sawfly in as little as 10 years.

by Julienne Isaacs

Anew publication suggests future climate conditions in Western Canada will be very favourable to wheat stem sawfly.

The study, which was authored by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist Owen Olfert, appeared in the journal Canadian Entomologist last year.

Cephus cinctus is native to North America and, according to 2011 AAFC figures, the pest is responsible for cumulative yield losses of greater than 30 per cent and economic losses of $350 million annually.

According to Haley Catton, an AAFC cereal crop entomologist who co-authored the study, it’s a top pest of cereals in southern Alberta, southern Saskatchewan and parts of Manitoba.

Wheat stem sawfly is cyclical, with outbreak occurrences largely dependent on weather conditions. Over the last several years, it hasn’t been as much of an issue, but the pest is again on the rise, says Scott Meers, insect management specialist for Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development.

“Currently we’re seeing sawfly as an increasing problem in Alberta. Last year’s survey showed that we have some areas of pretty significant sawfly cutting,” he says.

Damage is usually noticed shortly before harvest as the crop dries down, when sawfly larvae cut the stem. But the adult sawfly is present in the field earlier in the growing season, laying eggs in late June and early July. Once hatched, the larvae feed inside wheat stems through July and August, cutting stems in the fall once moisture content has dropped below 50 per cent.

By far the best biological control agent of wheat stem sawfly is a parasitic wasp, Bracon cephi. In typical years, B. cephi sees two full generations in the field, with two opportunities for controlling wheat stem sawfly. But in dry years, when wheat is harvested early, sawfly larvae are already in stubs below the soil surface when the second generation emerges, out of the parasitoid’s range. As a result, the second generation of B. cephi is unsuccessful, its survival drops and the sawfly population increases.

Climate is the number one determinant for an insect’s distribution and abundance. For example, all pests have requirements for the number of growing season days needed to complete their lifecycles. In the case of wheat stem sawfly, it’s weather that determines the survival of the pest’s chief predator, Catton says.

“Usually insects expand right to the edge of their limits – they’ll take up as much space as they can,” Catton says. “Small changes in climate can remove a bottleneck for them and allow them to increase their range.”

Climate predictions

Olfert’s study used a bioclimatic modelling software tool called Climex, which helps describe the climatic suitability of a landscape for an insect species’ survival and reproduction, which then

gives researchers a sense of population abundance.

Once the team had a map of wheat stem sawfly’s current distribution in Western Canada, they changed the climate parameters, raising and lowering temperature by one and two degrees Celsius and increasing and decreasing precipitation by 40 per cent.

Their results showed that a temperature increase of one degree Celsius warmer than normal resulted in a doubling of the pest’s range. A two degree increase in temperature resulted in “favourable to very favourable conditions across most of the Prairies and Boreal Plains ecozones, with 79.4 per cent of the area categorised as very favourable,” the authors note.

Then, they assessed the response of wheat stem sawfly to two future climate scenarios – 2030 and 2070. Projections for 2030 showed that most of the Prairies and Boreal Plains would be categorized as very favourable for the pest. By 2070, according to the models, favourability for the pest would spread to the Peace Lowland ecoregion.

“The predictions from the general circulation models suggest that Canadian wheat production will be challenged by more frequent, more widespread, and more intense C. cinctus attacks in the future,” the authors conclude.

Catton says it’s important to understand that the predictions don’t explain what will necessarily happen.

“They explain favourability of environment for insects. That doesn’t account for management,” she says. “The environment is going to be more favourable for sawfly in as little as 10 years. So,

we interpret this to mean that sawfly is a pest that we really need to keep paying attention to.”

Integrated pest management can go a long way toward managing the pest, she says, starting with solid-stemmed wheat varieties.

“I think these results can be framed as ‘stay vigilant’ – let’s not get complacent with sawfly,” she says. “We have solid-stemmed varieties, which can be effective, but they aren’t perfect, and we don’t know how they will perform up in the Peace.”

But the results could also be read as conservative in light of the fact that the models assume the insect won’t change. In reality, insects are constantly changing, and a native pest like wheat stem sawfly could become better at adapting over time, Catton says. “It’s our best guess based on what we know about sawfly now. But it’s trending in the wrong direction.”

Meers says that because the driving force behind sawfly population control is B. cephi, producers should try to boost its survival by leaving as much stubble as possible so the wasp can successfully overwinter. Because insecticides aren’t effective against sawfly anyway, hold off on spraying unless absolutely necessary to protect the parasitoid.

But producers’ best control measure is solid-stemmed varieties. Meers says there are good varieties for the Canadian northern class and some durum. Few options exist for the hard red spring wheat class, but there are some solid-stemmed varieties in the pipeline. Producers should refer to provincial seed guides when selecting varieties resistant to sawfly.

Licence to spray.

This season, elite growers are being briefed on a new secret weapon for barley in the fight against the prairie’s toughest weeds.

• Cross Spectrum Performance

Get leading Group 1 grass control plus unparalleled broadleaf control of cleavers, hemp-nettle, wild buckwheat, kochia and many more.

• Total Flexibility

With Arylex™ active fl exibility, you can apply on your own terms. Early, late, big or small.

• Easy Tank Mixing

Tank mixed with MCPA, count on 3 chemical families in the Group 4 mode of action for e ective resistance management.

Get briefed at OperationRezuvant.Corteva.ca

Soil quality improves with reduced tillage, but there are trade-offs.

by Julienne Isaacs

Anew study out of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Swift Current Research and Development Centre (SCRDC) will help shed more light on tillage and weed management in organic production.

The six-year study, which ran from 2010 to 2015, was designed in collaboration with organic producers from the Advisory Committee on Organic Research (ACOR), which helps direct organic research priorities at Swift Current, and was published in Agronomy Journal last year.

“We decided that a cropping sequence and tillage study would be of most benefit to organic production. [Studies on] cropping sequence and tillage intensity and timing were, and still are, considered of great relevance to organic grain producers,” says AAFC research scientist Myriam Fernandez, who led the study and is head of the Organic Research Program at SCRDC.

Weed and nutrient management are key issues for organic producers. Without the use of chemical inputs, most producers typically rely on legume green manure for nutrient and pest management, explain the authors of the publication.

Conservation tillage (or zero-till) lowers the environmental impact of crop production and helps build soil organic matter and soil carbon, but for organic producers, it comes with trade-offs in weed and pest control.

Fernandez says producers are really interested in diversifying organic production beyond relying on green manure for nitrogen (N) input, and reducing tillage operations.

“The goals of this multi-year study were to determine if diversified crop rotations and reduced tillage under organic management could keep weed populations at low levels, maintain soil fertility and quality at adequate levels, and foster healthy annual crops for sustainable and profitable production,” Fernandez says. “We gratefully acknowledge funding by the Western Grains Research Foundation and the Agri-Innovation Program of Agriculture and AgriFood Canada’s Growing Forward 2 through the Organic Science Cluster II, initiated by the Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada in

collaboration with the Organic Federation of Canada.”

The study evaluated two tillage intensities, high and low, on two rotation sequences – a simplified rotation of wheat and forage pea green manure, and a diversified rotation (wheat-forage pea green manure-oilseed-pulse). The oilseed crop alternated between flax and yellow mustard; the pulse crop alternated between field pea and lentil.

High tillage treatments were based on current practices, while in the low tillage plots, tillage was performed only as needed to prepare seedbeds and control weeds. Tillage increased even in the low tillage plots toward the end of the study due to an increase of perennial thistle populations.

All crops and treatments were selected in collaboration with the ACOR producers to reflect current practices, Fernandez says.

Soil samples were taken in the spring and fall and analyzed for soil moisture, nutrients, aggregate distribution and soil carbon.

Precipitation over the study period was substantially greater than the long-term average, the authors of the study wrote, with the highest precipitation in the 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 crop years, but there was also a year with a very dry spring and early summer – 2015.

“Drier conditions, more typical of our region, would not likely have resulted in such high levels of Canada thistles as we encountered in the last few years of the study,” Fernandez notes. Lower levels of the weed would have allowed the researchers to continue with the study’s original design for minimum tillage.

Soil moisture and N content were highest in the simplified rotation under high tillage, resulting in higher wheat yields. Wheat in the

diversified rotation under low tillage had the lowest yields, Fernandez says, but boasted the best soil quality with higher soil organic carbon, more water-stable aggregates and fewer erodible particles.

“Because this increased the soil’s resistance to wind and water erosion and contributed to the environmental sustainability of organic production under reduced tillage, a different strategy for increasing soil N and grain yields would be needed without compromising the aforementioned key soil quality factors,” Fernandez says.

She adds that one of the study’s most surprising results was the observation that wheat yield variation had more to do with precipitation and soil N levels than weed infestations.

“The prevailing general belief is that weeds are the main reason for lower grain yields usually observed under organic production,” she says.

“The observation that protein concentration in organic wheat tended to be higher than in a conventional zero-till trial nearby, and than in commercial wheat grown in the same area, suggests that the former was more efficient at producing higher protein grain.”

The researchers didn’t observe a negative relationship between grain yield and protein concentration during the years of the study, which might be explained by the release of mineralized N from the previous legume green manure or pulse crop, she adds.

Based on the wet years of the study, Fernandez says the low tillage treatment did not appear to be viable for more than a few years. Producers might have better results from using reduced tillage as a basic strategy and employing occasional intensive tillage when needed to help deal with perennial weeds.

“In organically-managed fields, occasional tillage would be an effective means of weed control with minimal negative impact,” she concludes.

Wild oats can make your fields stand out for the wrong reason. Varro®, a Group 2 herbicide, provides control of wild oats and other tough grass weeds while helping manage resistance on your farm.

Varro – for wheat fields worth looking at.

We cut the fluff to deliver on what matters—your bottom line. The Brevant™ canola lineup is designed to be flexible, giving you the right agronomic and marketing options for your business. So, when you pull into your local Brevant™ retailer, you get the seed you need, and you can get back to work.

We work hard to make your job easy.

Visit your retailer or learn more at brevant.ca