Take us to your operation and show us the ins and outs of your season. The winning photo will be featured on the cover of Top Crop Manager’s December print issue.

Insights

Designing canola cultivars with multigenic resistance

Diversified rotations achieve overall results

LOOKING FOR A LITTLE INSPIRATION?

Here are some photo ideas to get you started:

Seeding | Scouting | Harvest | Pests

Diseases | Crops at different growth stages

Picturesque crops or fields

Developing high-yielding wheat and lentil varieties

After several dry years and El Niño producing a warm, dry winter across Canada, Alberta is at risk of severe droughts in 2024, especially in the southern part of the province. To help, 38 of the largest and oldest water licensees in southern Alberta have voluntarily agreed to reduce the water they use if severe drought conditions develop this spring or summer.

CONTEST CLOSES October 1, 2024

by Michelle Bertholet

The last time Top Crop Manager had a redesign was in the fall of 2011. It was the most significant redesign since the magazine’s launch in 1974, when it was introduced as Agri-Book Magazine. To celebrate 50 years in this special issue, we are excited to debut a new logo and design.

If you don’t recognize the headshot or the job title in the top corner, you’re right – I’m not the usual contributor on this page. In the coming months, we’ll welcome a new editor to our team, and they’ll take their rightful place here – but for today, it’s my pleasure. My name is Michelle Bertholet, and as Group Publisher, Agriculture, I manage a group of media brands for Annex Business Media, including Top Crop Manager.

I joined the Top Crop Manager sales team in 2014. Prior to starting, my now-late grandfather gave me a poster showcasing the genealogy of Canada Western Red Spring Wheat that Top Crop Manager shared with readers in 2012. My grandfather enjoyed studying genealogy, so the fact that he liked the poster made sense. Now, as the publisher, it’s rewarding to think about how he kept that resource for two years before sharing it with me. That tangible poster was passed down through generations and still leaves an impact 14 years after publishing. For background, my grandparents farmed and were considered pioneers in agriculture. The original homestead, south of Brandon, Man., is still farmed by my extended family and is currently seven years shy of becoming a Legacy Farm. My grandparents farmed through the evolution of horses and threshing machines to today’s larger equipment and modern electronics. They were the first of their area to grow canola, the first to purchase and set up a grain cleaner, and the first to acquire a four-wheel drive tractor and a self-propelled combine. They were hard-working, progressive, forward-thinking, and future-focused – like many of you that I’ve had the pleasure of connecting with over the years.

Over the past 50 years, farming has, of course, evolved. Decisions are made differently, margins are tighter, seasons are shorter. The options for inputs, technology and data have increased substantially. While change is certain in agriculture, what hasn’t changed is our commitment to sharing trusted third-party crop production insights through well-researched stories, written by top-tier agricultural journalists.

How, when or wherever you choose to read Top Crop Manager – on behalf of our team, our writers, the researchers whose work we share, and our advertising partners, thank you for sharing your time with us, yesterday, today and into the future.

In closing, here’s to you – the bold; the innovative; the early adopters and farming’s lifelong learners.

510-6875 Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager SERINA DINGELDEIN (416) 510-5124 sdingeldein@annexbusinessmedia.com

Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW CEO SCOTT JAMIESON sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

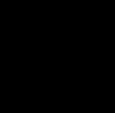

Get ahead of the competition. Weed scouting begins now to plan for fall applications of Avadex, Edge or Fortress MicroActiv.

BY CAROLYN KING

Predicting the future has never been easy, and the unexpected upheavals in our world over the past few years have underlined that fact. Yet we still need to make choices based on our best guesses – and our hopes – about what lies ahead, while also trying to be ready to deal with whatever comes our way.

Top Crop Manager asked five representatives of Canadian crop grower organizations to share their thoughts on what factors and trends are likely to influence crop production over the next decade and how to capture the opportunities and overcome the challenges ahead.

The five representatives see a range of factors playing out over the next decade, including some that open up exciting possibilities and some that could pose serious challenges.

“I don’t think you can talk about factors or trends without talking about global trade and geopolitical factors,” says Tara Sawyer, Alberta Grains chair. “We have seen that with market pricing; we saw the high highs, and now we’re seeing that drop and rising input costs with that. Global trade definitely plays a part in our grain prices, and that is something we will always have to watch out for.”

She adds, “Consumer food demands keep shifting. Maintaining our crop production to be able to meet those changing demands is something we have to think about.”

“The number one factor is that our commodity prices will no doubt always be subject to a commodity cycle, and that we have just out-produced demand in recent years. Commodity prices are showing the effects of that,” notes Jeff Harrison, chair of Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO).

“That, in combination with other factors – very high rates of inflation and the cost of inputs, global trade issues, global events and disruptions around the world –are all leading to production costs on our farms that are escalating at a much higher rate than in the past. We see

governments taking protectionist policies. And currency values and interest rates all have huge impacts on our farms.”

Melvin Rattai, chair of the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers (MPSG), is well aware that market prices will continue to strongly influence production trends. Although he can’t predict those prices, he says, “We know there is demand for soybeans and pulses so the prices hopefully will remain fairly stable or improve.”

Emerging domestic market opportunities could also influence production in some regions.

“Renewable fuels and biofuels are becoming more prominent with markets opening up. And we’re seeing right now new crush plants coming online in Saskatchewan; that change is already in progress and will keep developing,” comments Keith Fournier, chair of the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission (SaskCanola).

“Traditionally, a large portion of our cereal and oilseed production in Atlantic Canada has been for

livestock feed, but our producers have the ability to produce a high-quality product for alternative markets as well,” says Caitlin Congdon, director-at-large with the Atlantic Grains Council (AGC).

“In the last 10 years, we’ve seen a boom in the craft beer industry in the region. As this continues and other niche markets like craft distilleries and value-added food products see the quality and value of grains and oilseeds that can be produced in their own backyard, I think some of our production can shift to fill those demands.”

Sawyer says, “In Alberta, we are seeing more value-added processing, which is a way to open up new market opportunities. We have the commodity here so why not do the processing here to add to our export portfolio versus just selling to have someone in another country process it?”

“I think the top factor relates to our growing conditions here in Alberta and how they have changed. The weather patterns are making it challenging,” notes Sawyer. “Between the lack of moisture, too much moisture, and the stress that puts on the farmers and the crops, that’s definitely affecting our profitability.”

“Some of the buzzwords in agriculture these days include sustainability, regenerative ag, and resilience to climate change. Producers in the Atlantic region are feeling the effects of climate change every day as we deal with unpredictable

SaskCanola chair Keith Fournier; Jeff Harrison, chair of Grain Farmers of Ontario.

weather patterns that wreak havoc on our already short growing season and make conditions for disease and pest development even more prevalent,” says AGC’s Congdon.

“The last several years have really been a test of that resilience, but producers are rising to the occasion by exploring new practices or changing the definition of what makes a ‘successful’ crop or rotation.”

SaskCanola’s Fournier says, “Some factors are always with us, including the weather. Parts of Saskatchewan have had drought for three or four years, and we’ve gone through sessions of wet. Over the next decade, weather is still going to be a factor. The stresses of diseases and insects come and go, and those are also factors that we will be dealing with over the coming years.”

Fournier thinks regulatory/policy considerations could also affect production practices. “Thinking back to last year with the lambda-cy issue [the Pest Management Regulatory Agency’s decision regarding lambda-cyhalothrin], there could be

“We know there is demand for soybeans and pulses so the prices hopefully will remain fairly stable or improve.”

other products we can’t use in the future. Those types of issues will be with us going forward, building on pressures from consumers but also policies of the government, affecting our use of fertilizers or other crop inputs.”

Another issue Sawyer sees is the aging farmer demographic and farm succession. “We’re seeing diverse stories about what succession planning looks like for people. Sometimes it is someone in the next generation of the family or perhaps a nephew or other relative. Or it might be a relationship the family has built with a kid who works for them who didn’t come from an ag background. So, succession planning and what that looks like is going to change a bit.”

The ongoing role of agricultural research and innovation is viewed as a crucial factor by our respondents, particularly in taking advantage of opportunities and dealing with challenges over the next decade. So, those views are presented in the next section.

Our respondents identify a variety of strategies for dealing with our changing world over the next decade.

Several of the representatives see sustainable agriculture practices as a valuable element in facing the

future, from a couple of angles.

“Farming practices are always evolving, but I think we will see that happen at warp speed over the next decade or so. Cereal and oilseed production will have to evolve to meet the demands of the market with regards to environmental as well as economic sustainability,” says Congdon.

“There are several programs currently that will support producers in adopting and learning about new or more sustainable practices, so that’s definitely an opportunity that we need to take advantage of. Being a small region, we don’t always have access to the latest and greatest technologies, whether that’s equipment, genetics, etcetera. So, we have to continue to push to stay current.”

She adds, “Then there’s the public perception aspect of sustainability and regenerative agriculture as well. Producers have the challenge of not only adopting new practices or dialing in existing ones, but also educating consumers about what it all means.”

“As farmers, we’ve got to make sure that we’re using the best management practices and following proper rotations so we don’t end up, for instance, losing blackleg resistance or clubroot resistance because that will then just set us back,” notes Fournier.

“We’ve also got to keep investing in improving public trust. If the public doesn’t trust that we’re growing healthy food and in an environmentally sustainable and safe way, it will be difficult for us to do what we do best.”

Sawyer comments, “We already execute a lot of

sustainable practices like crop rotations, conservation tillage, no-till, integrated pest management that don’t always get the recognition that they should, even though sustainability remains a priority for us.

Canadian farmers pride themselves on being leaders in sustainability, and we’re always looking for ways to improve on what we’re already doing.”

However, she would also like the government to showcase the positive contributions that Canadian farmers are already making on the sustainability front. “Internationally, we are recognized for our high-quality grain and our practices, but I sometimes think that message is not fully translated to our domestic consumers. They just hear the government wanting us to reduce carbon and hit their targets. I think the government needs to talk more about what we are already doing that is sustainable.”

“We need continued investment in developing more resilient crop varieties adapted to western Canadian growing conditions and pest pressures. But we also need more research investment into cropping practices because that is one way that we’re enhancing our productivity. And it is how

we can show some of our sustainability because of how we care for our soil health, how we manage our water, crop nutrition, that is all part of that continuing research investment,” says Sawyer.

“We also need to continue to invest in tools and technologies that will increase our stability, our efficiency, and help Alberta farmers continue to be profitable – that’s key – while being environmentally sustainable.” That includes precision agriculture and other innovations that will help in dealing with the issues faced by everyday farmers right now as well as looking ahead towards long-term opportunities.

Adopting such advances can bring financial challenges. She says, “Yes, we want to improve our efficiencies and the efficiency of our crop inputs, but the costs have to make sense.”

MPSG’s Rattai sees a similar challenge for pulse and soybean producers who are interested in some of the new hightech equipment that could improve yields and increase efficiencies. “As we upgrade our equipment over the next stretch, we have to figure out how the carbon tax rebate will work for purchases of equipment that will reduce our carbon footprint. How to access those rebates is not very clear.”

He is excited about advances through crop breeding. “There are new soybean varieties coming out that are more suited to the different amounts of rainfall and different frost-free days in different parts of Manitoba. On the pulse side, new varieties are coming out that farmers will be able to pick from over the next few years too.”

“I think agricultural research is essential to help producers manage the risks associated with things like initiating new practices or trying new input products. The Atlantic Grains Council has a strong research program that has really been led by what producers in the region want to know and are interested in,” says Congdon.

“This consists of both small plot research conducted by our Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and academic partners as well as field-scale work through our On-Farm Agronomy and Yield Enhancement Network (YEN) programs. Since the YEN was launched in the Maritimes in 2019, we’ve seen an increase in the average provincial yields for winter wheat, and not just for those participating in the program.

“This type of program allows producers to participate in research on their own farms and also feeds into a massive dataset that researchers and agronomists can use to figure out where we need to concentrate research and knowledge transfer efforts. As the YEN expands into soybeans for the 2024 season, I think that we will continue to gain valuable information at the farm level that will continue to help drive production and allow

Tara Sawyer, Alberta Grains chair, farms near Acme, Alta. Alberta Grains (an amalgamation of Alberta Wheat and Alberta Barley) is a farmer-directed organization that represents the interests of and serves as the single voice for the more than 18,000 wheat and barley producers in the province.

Keith Fournier, chair of the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission (SaskCanola), farms near Lone Rock, Sask. SaskCanola is a grower-led organization serving 17,000 Saskatchewan canola producers.

Melvin Rattai, chair of the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers (MPSG), farms near Beausejour, Man. MPSG is directed by producers and represents farmers in Manitoba who grow pulses including edible beans, peas, lentils, chickpeas, faba beans and soybeans.

Jeff Harrison, chair of Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO), farms with his family in Quinte West, Ont. GFO is the province’s largest commodity organization, representing Ontario’s 28,000 barley, corn, oat, soybean and wheat farmers.

Caitlin Congdon, director-atlarge with the Atlantic Grains Council (AGC), is a field crops specialist with Perennia Food and Agriculture. The producerrun AGC represents grain and oilseed producers in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador.

producers to maximize efficiency and sustainability.”

“Research and all the different ways that we collaborate to do research will be an important part of the puzzle in driving yield for farmers, to maintain that yield trajectory that we have started to expect,” says GFO’s Harrison. “Research on hybrids and market development and yield – those are all going to be important. Of course, that always has a catch: the more yield we produce, the more supply we produce, and that can have a negative effect on markets.”

Fournier notes the valuable role of crop-related research at universities and other public research facilities across Saskatchewan as well as life science companies. That research includes developing better crop varieties to help growers keep ahead of the game on things like changing disease and insect problems and developing more efficient practices for managing fertilizers, land and water.

He also highlights the importance of ongoing investment in research by government, private companies and producers themselves through levy dollars.

Sawyer emphasizes the value of continuing to collaborate with other provinces and the need for more funding to help execute these initiatives. She adds, “It would be nice to see more funding available towards national and even international research collaborations within the agriculture industry. While the collaboration is there, any additional funding would be incredibly beneficial. Innovation helps us all

and we have a huge world to feed.”

Research can also help in capturing market opportunities. Fournier gives the example of developing canola varieties with increased seed oil content for the biofuel/renewable fuel market. And Rattai is interested in pulse and soybean varieties that can meet the specifications of particular export markets.

In particular, he points to an exciting opportunity for Manitoba growers in identitypreserved (IP) soybeans. “When I went on a trade mission to Thailand and Japan this year, I saw a big demand in those countries for IP soybeans that are good quality. I think in our province, we can grow the quality they are looking for. That’s a market that we have never even really tapped yet. We’ll have to work with our soybean seed suppliers and with the people that market the soybeans to capture that extra value.”

Fournier sees the benefits of having some domestic market options, especially when international trade problems crop up. “The markets opening up here – the biofuels and renewable fuels and the new crush plants – can reduce the impacts of situations like we had a few years ago with China’s market access restrictions for canola seed.”

Harrison emphasizes that predicting opportunities and challenges around policy and trade will be tough. “We have federal, provincial, and municipal elections all happening in the next three years. Our closest neighbor and our biggest

competitor, the United States, have their election in the fall of 2024. Our biggest competitor is operating under an extension of their U.S. Farm Bill,” he says.

“The job of a farmer to utilize a crystal ball is going to be even more difficult going forward to identify trends and be able to predict the path of currency values – as currencies fluctuate, they can make our inputs cost more or less – and the timing of them to be able to inventory when needed as lower price cycles hit.”

Sawyer says, “I was on a trade mission in January and I can tell you it is key that we continue to engage in new crop missions with our export markets. I witnessed firsthand how important it was to have that personal connection with the people who want to buy our grain.”

She adds, “We also need our government to help reduce some of the barriers in the export market to help us grow and develop with those markets. Some really great new markets are coming open where we need to foster relationships.”

Atlantic Canada is in a slightly different situation. “We’re a small region, so individually it’s tough to compete with larger production areas or even make it worthwhile to explore some markets,” notes Congdon. “But I think what makes us unique and can be a strength in Atlantic Canada is working together as a region toward a common goal.”

Although we can’t be sure about what will be coming our way, Canadian farmers’ innovativeness, resilience, and care of the land will help in tackling whatever the future brings.

Long-term acroecosystem “Old Rotation” experiments initiated at AAFC Swift Current in 1967.

For more than 100 years, agroecosystem experiments have provided unique and valuable insights into modern cropping systems.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Long-term agroecosystem experiments (LTAEs) have been in place on the Canadian Prairies for more than a century. Currently, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) manages about 24 ongoing LTAEs across the Prairies, providing invaluable long-term, multi-decadal experimental systems for testing new research questions. The first AAFC LTAEs were designed and inspired by the famous Rothamsted Classical Experiments established in 1843 in England, with the oldest and longest-running experiments started at the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre in 1911. These experiments provide a wealth of information and understanding of agroecosystems and the complex interactions impacting agricultural production on the Canadian Prairies.

“These LTAEs were generally established to help farmers determine the types of crops they could grow in different regions and how to grow them during the early farming expansion on the Prairies,” says Charles Geddes, research scientist with AAFC in Lethbridge, Alta. “At Lethbridge, we have

the oldest and longest-running agroecosystem experiments in Canada that have been ongoing since the native prairie was broken in 1910, and certain data has been collected annually from these plots for more than a century. Across the Prairies, other long-term AAFC experiments continue in Saskatchewan including at Scott, Indian Head and Swift Current. A smaller number of long-term experiments are managed by universities such as the University of Alberta Breton Plots that are over 90 years old, and the University of Manitoba’s Glenlea long-term rotation plots, to name a few. We now have over a century of information collected from these experiments that provides immense value for research purposes and understanding the agroecosystems we operate in.”

The LTAEs in Lethbridge continue today with about 18 different long-term experiments focusing on crop production and agroecosystems. One of the first and longest experiments, known as Rotation ABC and located next to the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre, was part of a larger experiment started in 1911 trying to determine which crops would

grow best and the most optimum and economic crop sequences in southern Alberta. Three of the several dryland rotations continue today and include A (continuous wheat), B (fallow-wheat) and C (fallowwheat-wheat). Rotation ABC has continued to be used as a check or benchmark for various other experiments over the years. Another experiment known as Rotation U, established in 1911, focused on irrigated crops, originally under surface flood irrigation, transitioning to high-pressure sprinkler irrigation in 1973, and in 2024 evolved to a new efficient low-pressure, lateral move irrigation system.

“This long-term history provides a very unique timeline of consistent data collection over a century and a timeline of changes and adoption of new technologies and farming practices,” Geddes says. “The original plots were managed using horse-drawn farm equipment and tillage and have evolved over the years to no-till systems, chemical pest management, and modern cultivars. Over time, the research has shown an improvement in crop productivity, mainly due to the adoption of new practices, technologies, and varieties introduced over the last century. This knowledge is now being used to address emerging issues such as climate change, sustainable cropping systems, carbon sequestration, and nutrient cycling.

“We are also looking at opportunities to integrate the various historical datasets such as yield and quality data, soil samples, weather, and precipitation together in a more systems-based approach,” Geddes says. “We have statistical techniques that didn’t really exist in the past and new modeling approaches to help answer questions. We can look at variables such as changes in

New long-term acroecosystem experiments initiated at AAFC Swift Current in 1987 for comparison with the 1967 “Old Rotation” experiments; The initial breaking of the native prairie at Lethbridge in 1911.

yield stability over time rather than just yields. This can help evaluate how stable yields were over time and how resilient they are under different management scenarios, especially under changing climate. Historical soil samples can help answer questions around changes in microbial communities, for example, with the earliest soil samples that date back even before synthetic fertilizer or pesticides were used in crop production. The continuous and multiple decades of research are even more valuable today as we address big questions around carbon sequestration, climate change, productivity risk, sustainability and long-term economic viability.”

Geddes adds that LTAEs can help address a range of management issues including weeds. For example, weed surveys are showing widespread glyphosate resistance of kochia and, more recently, a new type of resistance to Group 14 herbicides. Some producers are considering strategic tillage to manage herbicideresistant kochia populations. In a recent study, a longterm no-till experiment from the 1960s has been revamped to focus more on strategic tillage, comparing no-till, conventional tillage, and occasional tillage of about one in every four years. This study, now in its 10th year, will help understand if soil health can be maintained even with strategic tillage and includes sampling of both soil health and the weed seedbank. Hopefully, the results will show that using tillage sparingly for weed management might be done without negative impacts on soil health.

“The Lethbridge LTAEs comprise a very precious resource and are really a research platform that can be used to assess various cropping system factors,” says

“The original plots were managed using horse-drawn farm equipment and tillage and have evolved over the years to no-till systems...”

Ben Ellert, AAFC research scientist – biogeochemistry. “The experiments are not museum pieces but rather have evolved as technologies have advanced in equipment, genetics, inputs, and other factors. We no longer use horses or stationary threshing machines or the Noble blade. The experiments continue to test our understanding, whether we are looking at long-term trends or developing computer simulations and predictions that can be tested against the real data. We are able to deploy scientific technologies, such as accelerator mass spectrometry to trace radiocarbon, that those who first established the studies couldn’t even envision. But such advanced tools help us evaluate and understand factors such as nitrogen use efficiency, greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon changes over the century.”

One other long-term experiment of note is at Onefour Research Station, originally established in 1927 as a Dominion Range Experiment Station in the southeast corner of Alberta. In 1930, a range productivity monitoring study was established in the northwestern portion of the experimental station. The SmoliakWillms site, as it is locally known, had comparatively poor soils that were representative of large areas of native rangeland in that region. The site was, and still is today, valued for its intact native grasslands, rare plants and animals, diversity of soil and rangeland types and unspoiled wildlife habitat.

“The amount of forage dry matter produced in annually re-positioned cages to prevent loss to grazing has been monitored since 1930,” explains Ellert. “The trend in long-term precipitation changes was small; however, starting in about 1990, there was a clear increasing trend in forage production per cm precipitation. There were no changes to grazing intensity or cattle distribution or anything else, but forage yields were increasing. It appears that the increases are related to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations that measured 360 ppm in the 1990s but have increased to 420 ppm today. The early rangeland ecologists who established the study in 1930

would not have anticipated that we would be contemplating the possible influence of atmospheric CO2 on productivity.”

Now that almost 100 years of data have accumulated for this native rangeland at Onefour, researchers are able to ask new questions of the data and test their understanding of how such systems respond to climatic and other challenges, now and likely to be encountered in the future. The site is now run as a rangeland research ranch by the Province of Alberta in conjunction with the University of Alberta and local ranchers after being divested by the Government of Canada to the province in 2015.

BELOW A historical aerial photo of Rotation ABC which now borders the Lethbridge city limits.

The LTAE in Indian Head has been in place since 1958 to address the decreasing soil organic matter content and wind erosion concerns, and continues today. “We have always maintained the traditional continuous wheat, fallow-wheat, fallow-wheat-wheat and comparisons of unfertilized and fertilized plots from the beginning,” explains Bill May, crop management agronomist with AAFC in Indian Head. “There have also been various experiments conducted to analyze the productivity of wheat crops when they are treated with variables such as fertilizers, green manure legumes and reduced fallow frequencies. Some other rotations have included fallow-wheat-wheat with about 30 per cent of the straw baled off the field and a fallow-wheat-wheat followed by three years of alfalfa. In 1990, the experiments were converted from conventional to no-till cropping systems. Most recently we added modern rotations to compare to the LTAE including wheat-canola-soybean and wheat-canolaoat-soybean, adding an agronomy focus to the more soil health focused experiments.”

May adds that although the traditional LTAE experiments have been maintained, when new agronomic practices are incorporated by farmers in the region, those inputs are incorporated in the LTAE cropping systems as well.

“We want to try to model what is actually happening on the farm as opposed to a static system based on 1958 production practices, such as trends towards increasing fertilizer rates. When comparing the long-term unfertilized to fertilized experiments and the move to no-till, the first impacts to the unfertilized plots tended to be stability of production; however, over time, we are seeing yields increase. Soil organic carbon has increased from the increasing fertilizer rates and the transition to no-till. The long-term plots that included three years of hay in rotation had the greatest amounts of soil carbon. In a recent study, we also compared the soil organic carbon and nitrogen content between these crops thirty, forty and fifty years into the study, and concluded that straw removal had no significant effect on the soil or grain yields. Over the years, the results show that the appropriate application of fertilizers, the inclusion of green manure and forage crops, reducing tillage, and converting to no-till farming practices all increased grain productivity and enhanced soil organic matter content.”

The long-term experiments at Indian Head will continue, along with the collection of crop production data, weather and precipitation and soil samples. May notes that they regularly publish papers on various aspects of the LTAE to make the data and information more accessible. The papers usually include trends since the beginning of the experiments, rather than just a short five or 10-year snapshot. This provides the opportunity to evaluate how the last 10 years, for example, is adding on to the whole rotation or contributing to changes as a whole. By incorporating new practices and advancements that could be adopted by farmers in the region, the experiments provide unique and valuable insights into modern cropping systems.

At Swift Current, there are three LTAEs, including the first ‘Old Rotation’ established in 1966, the ‘0MC’ or zero-minimum tillage study in 1981 and the ‘New Rotation’ established in 1987. “Although the experiments have evolved, some systems that were in place at the inception are still currently ongoing,” explains Mervin St. Luce, research scientist with AAFC. “In some rotations, fallow was replaced by pulses and more diversified cropping systems including

Keep your farm prosperous with advanced protection.

If you’ve ever wished your cereals could make a bigger impact on your farm’s bottom line, this is the fungicide for you. Sphaerex® delivers stronger, longer-lasting efficacy on leaf disease and outstanding control of FHB. It also helps preserve your grain’s grade with its best-in-class DON reduction. This exceptional level of protection leads to increased quality, yields and profits. Now just imagine where all that might take you. Visit agsolutions.ca/sphaerex to learn more.

pulses, canola, and polycultures were added. In these continuous wheat experiments, nutrient cycling, uptake and efficiency, water use efficiency and sustainability (e.g., carbon footprint) comparisons continue. There are also sub-plots within the main experiments that are comparing unfertilized to N and P fertilization as well as investigating legacy P and P cycling. This component is led by AAFC research scientist Barbara Cade-Menun.”

The 0MC experiments compared wheat-fallow base systems under conventional, minimum-till and no-till cropping systems. Along with wheat-fallow and continuous wheat experiments, rotations including lentil, chickpea, and green manure were included. In 1997, wheat-pulse systems were established on plots that had been wheat-fallow under conventional and no-tillage, respectively. “Retired AAFC researcher Brian

Noble blade in the Lethbridge LTAE, a wide-blade cultivator designed to maintain surface coverage of crop residues to protect soils against wind erosion; In the early days of the Lethbridge LTAE, a stationary threshing machine was used for harvesting crops.

McConkey also led a project from 1996 to 2018 to monitor soil organic carbon across commercial farm fields in Saskatchewan,” notes St. Luce. “The Prairie Soil Carbon Balance project monitored soil organic carbon after the conversion from fallow and conventional tillage to no-till and continuous cropping from 1996, with 136 benchmark fields that were resampled four times, the final sampling in 2018 where 90 fields were sampled. We are finalizing a study comparing the on-farm results to the soil organic carbon change in the small LTAE plots. Early indications are that the results were trending in the same direction for soil carbon; however, total N was the reverse with more losses in the small plots as compared to the farm fields. We speculate that this was due to higher fertilizer rates on the farm and the higher frequency of canola in rotation. The soil organic carbon rate of change was 0.28 Mg/ha/yr in commercial fields and 0.16 Mg/ha/yr in the LTAE plots.”

The ‘New Rotation’ was established in 1987 as a comparison to the ‘Old Rotation’ under conservation tillage. The rotations have evolved, with durum wheat replacing spring wheat in a diversified rotation with canola and lentil, the inclusion of green manure, and a crested wheatgrassmeadow brome perennial system.

“The New Rotation is managed as no-till, and all of the rotations are fertilized based on soil tests for each rotation,” explains St. Luce. “This gives us the ability to look at nitrogen use efficiency, carbon footprint, and system productivity for each rotation. Almost all of the rotations are fully phased, with each phase of the rotation present each year so that each crop experiences the same conditions. Every year we collect soil samples in spring and fall for nutrient

analysis and measure grain yield, grain protein, and N and P in grain and straw. The soil organic carbon levels are significantly higher in the perennial grass as compared to the annual cropping systems. In 2022, the New Rotation became fully no-till as we transitioned from termination of the green manure through shallow tillage to herbicide kill.”

St. Luce emphasizes the value of the LTAEs that provide information to better understand and address climate change, carbon sequestration, greenhouse gas emissions, NUE and crop selection, especially for the Brown soil zone where moisture is the most limiting factor. “Like other LTAEs in Canada and internationally, we have archived soil and plant samples and detailed information going back to the 1960s. We are working on developing the first soil spectral library for the Prairies using the samples and information from the various LTAEs across the Canadian Prairies. Our LTAEs are also getting national and international attention, such as the inclusion of Swift Current, Indian Head, Lethbridge and One-Four in the recent North American Project to Evaluate Soil Health Measurements (NAPESHM) project, which includes 120 long-term agricultural research sites spanning from north-central Canada to southern Mexico. More than 20 indicators were used to evaluate effective measurements for soil health and to contribute to calibrating and validating models such as carbon change models. Unlike short three- to five-year funded projects, the LTAEs and continuous experiments on the same fields undergoing so many environmental conditions over time result in a solid data set to reach conclusions and make recommendations for a wide range of areas from agronomy, economics, soils, nutrient cycling, water management to climate change, resiliency and sustainability.”

“To ensure we continue the legacy of this unique and valuable long-term agroecosystem resource that AAFC has invested in over the years, we are collectively working to integrate the resources into a more accessible database system for our researchers,” says Geddes.

“We know this resource has already been very useful over the years and going forward has relevance for new work, such as new molecular technologies focused on the soil microbiome and other new technologies. This multi-decadal experimental system will remain a precious tool for testing novel research hypotheses, developing and verifying

ecosystem models, providing a deeper view of agricultural sustainability and determining whether old or new production systems truly stand the ‘test of time’. This long-term agroecosystem resource will continue to be valuable for addressing other research questions into the future, some we likely haven’t even thought of yet.”

It’s a fact — you’re an expert. Whether it’s knowledge passed down through generations or just pure hard work, your instincts help you day after day. So does your data.

It’s not a hunch when it’s backed by facts.

When you collect, reflect and project with software for field and finance, you upgrade what you know. And you know that smart decisions are driven by data. For a fact.

Designing canola cultivars with multigenic durable resistance to blackleg disease.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Canola growers rely on cultivars with genetic resistance as the best practice for managing blackleg disease, as fungicides have little effect in controlling blackleg. However, recently, the risk of blackleg incidence and severity is increasing, with the breakdown of the current resistance observed in some cultivars caused by the emergence of new virulent isolates.

Repeated use of the same resistance gene leads to the selection of virulent isolates of the blackleg pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans. Tighter rotations shorter than two or three years between canola crops in areas of high infection can also increase the risk. Continuing to develop cultivars with more durable resistance is a priority for researchers and canola breeders.

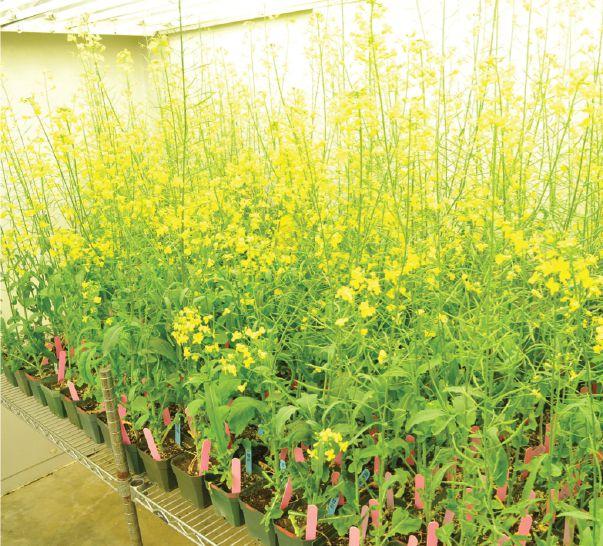

“We recently completed a five-year project focused on quantitative resistance (QR), also called adult plant resistance (APR), to control L. maculans in canola,” says Hossein Borhan, research scientist, molecular plant pathology with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon. “Two types of resistance, qualitative resistance conferred by race-specific R genes, and quantitative resistance (QR) conferred by non-race-specific genes (QTL), can be used to manage this disease in commercial cultivars. APR is the most favourable form of genetic resistance because it is multigenic and provides resistance that is effective against many pathogen isolates, making the resistance more durable. However, APR is more difficult to work with for researchers and plant breeders because, unlike race-specific disease evaluation that is conducted indoors, APR tests are carried out in the field under unpredictable and less controlled conditions. Typically, QR gene identification is conducted in field trials, which requires several years of testing before having

reliable results. It is also more challenging to identify and introduce APR into a breeding program.”

ABOVE Growth chamber based screening for adult plant resistance against blackleg disease.

Borhan set out to address those challenges in his lab to optimize a standard screening protocol for identifying APR to blackleg disease under controlled conditions and to validate the result under field conditions. A rapid screening method would provide the canola industry with a valuable tool for developing new APR varieties. Other objectives were to map major QTL genes, identify the causative genes and develop markers specific to those QTL genes.

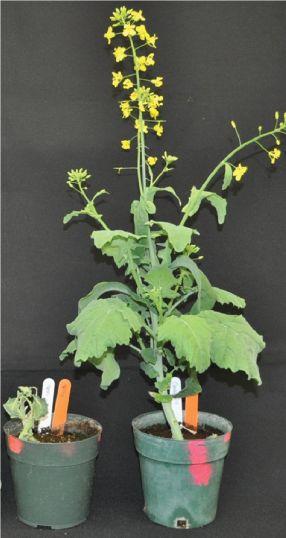

“We developed a growth chamber-based screening test for an APR assay, mimicking the natural infection cycle that occurs in the field,” Borhan explains. “The canola seedlings were inoculated with highly virulent L. maculans isolates, which is what occurs naturally in the field. The pathogen was allowed to grow into the stem similar to field infection. Blackleg disease was evaluated by measuring the size of the stem canker formed at the base of the stem at eight to 12 weeks after the initial infection. This whole indoor process takes about two-and-a-half to three months, and we can typically complete three or four rounds of screening and have reliable results within one year. In comparison, field screening requires four or five years of testing, which may or may not work because of environmental or other factors that could compromise a field experiment.”

In the second part of the project, using a well-defined and field-tested Brassica napus population, researchers combined mapping and gene expression data to

identify several candidate QTLs with a high probability of controlling the APR response.

“We screened about 200 B. napus lines and confirmed 40 lines with major QTL resistance, which had already been previously identified in the field,” Borhan notes. “We tested the QTL resistance genes in those 40 lines using markers that had been developed, and the results correlated very well with the assay screening. We then shared these QTLs with colleagues in Alberta to test in the field. The trial results showed that many of those QTLs were effective when infected with a mixture of L. maculans pathogen isolates and showed a good level of blackleg resistance in the field. A major QTL based on the growth chamber test was identified, which was the same as a major QTL identified in the field, proving the reliability of the indoor APR test to quickly provide growers with effective and durable QTL resistance to blackleg disease.”

The QTL screening and field testing also identified for the first time one of the significant causative QTL resistance genes. This new QTL gene discovery is an important first step in understanding the molecular mechanism of QTL resistance. QTL gene-specific markers will allow breeders to accurately introduce quantitative resistance against blackleg into commercial varieties. Additional research is currently underway to further test this gene in transgenic susceptible backgrounds to understand how these genes behave in different susceptible genotypes.

Other next steps are to determine how common the major QTL resistance genes identified in this project are in other QTL germplasms and how effective they are in conferring resistance against multiple races of the blackleg pathogen in different locations.

“As a result of the project, we were successful in optimizing and proving the reliability of the indoor QTL screening assay and its correlation with the field QTLs,” Borhan says. “This high-throughput screening will enable breeders to identify canola varieties with quantitative resistance to blackleg disease and incorporate QR genes into breeding programs faster and more accurately. The QTL resistance genes can also be combined with major single-race resistance genes to provide a more durable and effective type of resistance for farmers.”

Borhan adds that going forward, his lab and other researchers will continue to investigate how to successfully apply the outcome of this research in designing canola cultivars with durable resistance to blackleg.

“Blackleg research has significantly advanced in the past two decades. We have provided the canola industry with 12 race-specific resistance

RIGHT An indoor test of a susceptible (S) canola (Brassica napus) line and a line with quantitative (QTL) resistance against the blackleg pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans. Seedlings were inoculated with a virulent isolate of L. maculans. Plants were kept in a growth chamber and assessed at 12 weeks postinoculation.

“This high-throughput screening will enable breeders to identify canola varieties with quantitative resistance to blackleg disease and incorporate QR genes into breeding programs faster and more accurately.”

genes against blackleg and molecular markers for rapid determination of blackleg races in the field. Our understanding of quantitative resistance against blackleg has also advanced considerably; however, further research is needed to identify major QTL genes that are commonly present in various germplasms.”

“The good news for farmers is they should be able to continue to effectively control blackleg with genetic resistant varieties and by determining the race structure of blackleg in their field to use the best resistance genes against the most prevalent races in their field. Blackleg research achievements are one of the best examples of how the support farmers have provided through their grower association funding has paid back. The blackleg research efforts by AAFC researchers and canola breeders, together with collaborating industry partners, are a great example of how research investments really help farmers successfully address significant disease issues in their cropping systems.”

Diversified rotations, including pulse crops, achieve overall positive results.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Well-designed cropping systems can achieve multiple goals simultaneously, helping growers optimize crop productivity at the same time as improving whole-farm sustainability and resiliency. Understanding the complex interactions between crops and the trade-offs and synergies among different cropping systems will be key to helping growers identify productive, sustainable and resilient cropping systems and adapt to climate change.

“We have a multi-disciplinary team of researchers across the Prairies involved in a project comparing different cropping systems for agronomics, productivity, economics and their capacity for sustainability and resiliency,” says Kui Liu, research scientist and project lead with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, in Swift Current, Sask. “The goal is to provide a good strategy for maximizing overall cropping system performance, sustainability and resilience at the same time minimizing negative environmental impacts in major Canadian ecozones. Using multiple indicators and criteria to assess the complicated interactions between crops and the trade-offs and synergies among different systems indicators will help to identify the more productive, sustainable and resilient cropping systems for each of the ecozones.”

The study includes six carefully designed cropping systems that are being evaluated at seven ecosites across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba using a four-year crop rotation cycle repeated over the project. Cropping systems include conventional, intensified, diversified, market driven, high risk-high reward and a soil health-focused system. Researchers will be collecting and assessing a lot of data throughout the project that will help to understand the tradeoffs and synergies among the different system indicators. Through the project, multiple indicators

such as crop yield, soil health, pest levels, economic returns, carbon footprints and nitrogen-use efficiency are being used to assess cropping systems.

The first phase of the project was initiated in 2018, and the 2023 cropping season is currently in year two of the four-year crop rotation cycle. Researchers have submitted funding applications for an additional five years.

Liu explains that using a systems approach in this project will help to better understand the complex intensively managed agro-ecosystems on the Prairies, which are very complicated, dynamic and change a lot over the years.

“Specific cropping systems and rotations interact with the surrounding environments, soil, climate and weather, which together all affect the cropping system performance,” says Liu. “Using a systems approach also helps to understand biotic and abiotic interactions in a cropping system at the same time identify key drivers affecting the cropping system. In order to evaluate true cropping systems effects, a longer term study over several years is necessary in order to make recommendations for the best cropping systems. In crop rotation studies, researchers normally count the first four to five years as a transition period because results may be confounded by previous cropping systems.”

Although it is too early to be able to share any final outcomes of the project, there are two preliminary findings that stand out. Diverse cropping systems including three or more crops and pulses in a fouryear rotation generally have better overall results. When rotations are diversified with pulse crops, there are obvious benefits even in a short period of time. The other main preliminary finding is that precipitation is the most important factor affecting the performance of cropping systems. Since precipitation is so different among sites, there is no single cropping system that fits all regions. Therefore, producers will need to develop site-specific cropping systems by selecting crops that best suit their local conditions.

“Including pulses does bring benefits to cropping systems,” adds Liu. “Along with cropping system diversity benefits, including pulses also reduces requirements for nitrogen (N) inputs. In addition, pulse stubbles could result in producing higher yields for the following crops. Our early findings show the diversified rotation had a much higher nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), although not always the highest yields. However, considering the current pressure to

mitigate climate change or reduce environmental impact and reduce N inputs, the diversified rotation including pulses fits that goal very well. The diversified rotation produced decent economic returns but with much less N fertilizer inputs, making it a good alternative.

“The market-driven system in a short period of time did produce the highest economic returns, because there is a high frequency of canola in rotation. However, there were disease problems beginning to show up in these rotations, which will get worse if the frequency continues into the second four-year-rotation cycle. It is also important to realize that the high economic returns for a market driven system come with high N inputs. The N-driven economic returns have a low NUE and also a higher carbon footprint. The tradeoff is higher yield and return but lower NUE and a more negative environmental impact.”

For growers, setting clear goals when they plan rotations is key, whether that is to improve yields, yield stability or soil health, to control pests, increase NUE or gain economic returns. Liu explains that different crops have different functions and at the end of the day, growers need to strike a balance between all parameters. It is important when planning rotations to keep maximizing economic system services in mind. Try to use nature to provide free services and maximize those services. A key strategy for long-term sustainability is to incorporate ecological principles/functions into cropping systems. Being innovative and using diverse rotations can achieve multiple goals. One strategy can be to try alternative crops or practices on a small scale to see if it works, and then scale up. Liu emphasizes that growers know their land better than anyone else and can balance their goals and optimize different cropping systems over time.

“One of our project goals is to transfer the knowledge and findings we generate through the research to growers and industry,” explains Liu. “With the cropping systems approach and using multiple indicators, we have developed multiple factsheets that provide valuable insights and information on different system indicators. This allows growers to selectively choose the information that aligns with their goals, whether that is maximizing yield, stability, NUE or economics. The information can help them assess the rotations and indicators to optimize their cropping system.

“As the project progresses into additional rotation cycles, collecting much more data over more years and environmental conditions will make the rotation information much more valuable. We will also be developing a sustainability index, which will incorporate all of the different indicators into a single indicator. Our plan for the next phase of the project is to expand the soil health component to include soil carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas measures, assess resilience of cropping systems, use a model to predict cropping system performance and develop a sustainability index. These additional measures aim to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the performance of cropping systems and to help balance long term sustainability and economic returns.”

This project is funded through the AgriScience Program as part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a federal, provincial, territorial initiative. Other funders include: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Integrated Crop Agronomy Cluster, Western Grains Research Foundation, Alberta Wheat Commission, Alberta Pulse Growers, Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission, SaskCanola and Manitoba Crop Alliance.

BY CAROLYN KING

Recently, when University of Saskatchewan researchers Kirstin Bett and Curtis Pozniak were chatting over coffee, they came to a realization that is both off-the-wall and obvious – and has important implications for sustainability.

“We were talking about the concept that producers follow crop rotations to manage diseases, weeds, and nutrients, but breeders breed their crop on its own, without really thinking about the consequences for the next crop in the rotation,” says Bett, a professor of pulse crop genomics and dry bean breeding at USask’s Crop Development Centre (CDC).

“We realized we need to be breeding varieties for a rotational production system – as well as breeding to maximize yield and productivity of the individual crops,” says Pozniak, a professor of wheat genetics and breeding, and CDC director.

So, the pair have initiated an innovative research project to work on this idea. The project involves selecting lentil and durum lines for synergistic interactions in rotation, focusing on combinations that enhance nitrogen-use efficiencies in the rotation.

As Bett explains, “We want to see if it is possible to come up with a realistic way of making selections for lentils that are not only great lentils but are also going to be especially good for the subsequent durum wheat crop, and selecting durum lines that are great durum wheats and are also really good at taking advantage of being grown after a lentil crop.”

MULTI-SPECIES GENOMIC BREEDING

The team built on an approach used in a small proofof-concept trial conducted about 15 years ago by other CDC pulse and cereal breeders. That trial compared about a dozen lines of a pulse crop followed by about a dozen lines of a cereal.

Those results showed the yield response of the cereal lines did indeed depend on which particular pulse line was grown before the cereal line.

ABOVE As part of this project, greenhouse experiments will be tracking the nitrogen fixed by the lentil plants to see how much is taken up by the durum plants.

That original trial was fairly small because this type of experiment is not easy to do. Now, Bett and Pozniak are taking a deeper look at this concept with a much bigger trial.

“We have thousands of plots in our breeding programs, and nobody in their right mind is going to run all those lines one on top of the other, year after year, to identify which lines work well together in rotation. Even 100 lines of lentils and 100 lines of wheat would be an incredible amount of work,” notes Bett.

“In our project, every lentil line will get 10 different wheat lines, and every wheat line will be grown on 10 different lentil lines, meaning that the yield plots are 100 x 10. With a bit of fancy math and a lot of inference and layering understanding of the genotypes, we can make predictions as to what would have happened if we had done all 100 x 100 combinations.”

Pozniak outlines their strategy: “We will be looking for positive interactions between pairs of lines, for instance, where a particular durum line would outyield the check cultivars if a specific lentil variety was grown in the prior year. Then we want to identify DNA fingerprints that could predict the positive interactions in breeding programs. That way we could use a DNA test

to select lines that would perform well in the context of a rotation.”

Bett adds, “If this approach works, then we can retreat back to our old ways of just breeding lentils and just breeding wheat and select for the regions of the genome that are enhancing the subsequent crop or taking advantage of the previous crop.”

Grain yield will be the crucial measurement in this big field experiment. In addition, the project team will be sampling the soil microbiome across the plots to see how differences in the microbial community relate to differences in crop performance in the rotation. Sean Walkowiak, a microbiologist at the Canadian Grain Commission, will be collaborating on this microbiome work.

Bett and Pozniak chose a lentil-durum rotation for this project in part because they have the genomic resources for both crops to enable the necessary analysis – the lines in the trial are straight from the CDC breeding programs. Saskatchewan producers often grow lentils and durum in rotation to break up disease, insect pest and weed cycles, and to take advantage of nitrogen (N) fixation by lentils to reduce fertilizer needs.

If this project’s genomic breeding approach works, then researchers could investigate other crop combinations in the future. “Everybody asks us, ‘Why didn’t you put canola in the rotation too?’ It’s already a nightmare to do two crops,” laughs Bett.

She adds, “It’s very expensive to do this field experiment, but we think it is really important to look into this issue. We always recommend that you rotate your crops for many good reasons, so if we show that you are getting a yield bump, or you are saving money because you’re not having to spray as often, or you have nitrogen left over for your crop next year, that supports producer decisions to choose crop rotation. We hope this project will add even more support for crop rotation.”

This four-year project is very new, with the field experiment scheduled to start this spring, but Pozniak and Bett have already begun some indoor studies related to N cycling and N-use efficiencies.

Pozniak is working on a novel way to develop wheat lines that reduce N losses to the atmosphere so that more N will remain in the soil for crop growth. “Nitrogen fertilizer can be converted into nitrates by the soil microbiome through a process called nitrification and this form of nitrogen can be lost to the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas. Interestingly, a few years back, scientists from Japan and Mexico identified a wild relative of wheat that sends out exudates from its roots that inhibit this biological nitrification process,” he explains. 24_002895_Top_Crop_Western_MAY_JUN_CN Mod: April 3, 2024 10:04 AM Print: 04/12/24 page 1 v2.5

Those researchers have transferred the DNA segment for nitrification inhibition from the wild grass into wheat. And, they have shown that, with the presence of this DNA segment, there was reduced biological nitrification.

The CDC is working with the wheat lines containing this DNA segment. “We have already sequenced the genome of a few of these lines, and through comparative analysis, we can see what DNA was transferred from the wild relative,” says Pozniak.

“We will be intensively studying that DNA segment to see what genes are there, how they work and how exactly they are interacting with other genes in the wheat genome to inhibit the loss of nitrogen from wheat production systems.”

Pozniak and his team have already initiated crosses of the material into Canadian durum wheat germplasm. “By knowing the DNA sequence and having an understanding of the genes that are there, we can perform that crossing and introgression in a much more precise and efficient way.”

He notes, “By the end of the four-year project, we’ll have breeding material in adapted Canadian wheat germplasm that is carrying this particular DNA segment and expressing the trait in a Canadian background. Of course, we’ll need to confirm the effect of that introgression on nitrification in the context of Canadian wheat production systems.”

June 18 – 20 | Regina, SK

Bett is collaborating on some greenhouse experiments with USask colleague Kate Congreves, who has expertise in nitrogen cycling and greenhouse gas dynamics. These experiments involve using the 15N isotope of nitrogen, or “labelled nitrogen,” which allows the researchers to track where the N fixed by the lentil plants goes and how much of this N is taken up by the following durum plants.

They aim to identify lentil lines that fix enough N to meet the lentil plant’s own needs while also leaving a good amount of N for the subsequent durum plant to use, and to identify durum lines that more efficiently use N from the lentil crop or applied N.

They also hope to gain a deeper understanding of the N dynamics in this crop rotation system, including whether the amount of N left over from the lentil crop is enough to make a practical difference in the fertilizer needs or yields of the following durum wheat.

Cropping systems with better N-use efficiency help a grower’s bottom line by reducing fertilizer needs or increasing yields. But such systems are also good for the environment because they reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“The production of nitrogen fertilizer is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Also, nitrous oxide, an important greenhouse gas, is lost from agricultural soils,” explains Pozniak. “We want to develop varieties that producers will incorporate into what we are calling climate-smart rotations –rotations that maximize productivity while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

USask economist Nicholas Tyack is working on this part of the project. For instance, he will be looking at the potential for adoption of climate-smart breeding by breeders. And he’ll assess the potential for climate-smart rotations to be profitable for producers, or whether producer adoption would need to be incentivized and how that might be done.

Tyack will also be asking consumers whether they would be willing to pay extra for climate-smart crops, just like some people pay extra for organic.

“By the end of the project, we’re hoping to have a better handle on how to breed for crop rotations,” concludes Bett. “Ultimately, we want to be able to deliver varieties that offer the best bang for your buck. So not only are the varieties really great in the year you grow them but they are also contributing to the next crop in the rotation.”

This project is funded by Genome Canada, Western Grains Research Foundation, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission, Manitoba Crop Alliance, Results Driven Agriculture Research and Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund.

by Bruce Barker, P.Ag | CanadianAgronomist.ca

Ameta-analysis of research assessed climate change trends across Canada, focusing on the Prairie provinces from 1900 to 2021. The review was led by Emmanuel Mapfumo from the Department of Biological and Environmental Science at Concordia University of Edmonton. It included refereed journal articles, books, government documents and credible website documents. Winters are becoming warmer with reduced snow cover and variable growing season precipitation.

Between 1948 and 2012, Canada’s average annual air temperature rose by 1.7 C (range 1.1 to 2.3 C), compared to a global average air temperature increase of 0.8 C between 1900 and 2020. Since the 1970s, a steady increase has been observed in Canada, with northern British Columbia and Alberta experiencing the most significant rise in average winter air temperatures of 4 C to 6 C between 1948 and 2012. Other research indicates that from 1920 to 2019, Canada’s average air temperature increased by 0.9 C, ranging from 2.1 to 3 C.

In eastern British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and western Manitoba, the average annual air temperature saw significant increases in all seasons, ranging from 2 C to 4 C during the winter.

Daily maximum and minimum temperatures also show warming trends. Over the 1948 to 2016 timeframe, daily maximum temperatures across Canada during the summer increased by 0.9 C, and daily minimum temperatures increased by 1.3 C. Winter temperatures increased more, with daily maximum temperatures rising by 1.4 C and daily minimum temperatures by 2.1 C.

On the Prairies, warming has occurred since 1951, with the annual average daily maximum temperature increasing by 0.2 C per decade from 1951 to 2004, totalling a 1.2 C increase. Average minimum temperatures during the same period rose by 0.3 C per decade, amounting to a 1.4 C increase. Overall, both maximum and minimum air temperatures have risen in the Prairies, with a more pronounced increase in winter and spring compared to summer and fall.

The number of growing degree days (GDD) increased by an average of 178 GDD across Canada

from 1948 to 2016. The frost-free period in Canada also extended by 22.4 days from 1895 to 2007. These changes have led to a longer growing season, increasing by three to 12 days in the Prairies region from 1920 to 2020, allowing for the cultivation of new crops such as corn and soybeans.

From 1948 to 2012, Canada’s average total annual precipitation increased by 19 per cent, ranging from 15 to 22 per cent. However, changes in annual precipitation varied across the country, with decreases observed in southwest British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Growing season precipitation trends on the Prairies showed an increase in rainfall from 1956 to 1995, averaging 0.98 mm per year during the May to August period.

Snow water equivalent (SWE) has decreased in Western Canada, with an average maximum SWE decrease of approximately two to 10 mm per decade at high elevations over the period from 1950 to 2010.

The analysis also examined yield trends over the past century. From 1904 to the 1930s, wheat yields generally decreased, with significant drops in the 1920s and mid-1930s due to drought and disease. Better growing conditions in the late 1930s and the release of the new stem rust-resistant variety Thatcher led to increasing yields. From 1958 to 1978, wheat yields increased rapidly across the Prairies.

In southern Alberta, central/southern/eastern Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba, there was an observed increase in maximum wheat yield potential of 5.3 to eight lbs/ac/year (six to nine kg/ha/year) over the period from 1947 to 1992.

From 1972 to 1990, CWRS (Canada Western Red Spring) wheat yield gains were 0.35 per cent per year across Western Canada, but this rose to 0.67 per cent for the period from 1993 to 2012.

Comparing the periods 1971 to 1980 and 1991 to 1996, barley yields increased by over 25 per cent across the Prairies.

Canola yields steadily rose during the 1960s and 1970s when cultivars were still rapeseed, with yields reaching 18 bu/ac (1.01 tonnes/ha) and rising to 23 bu/ac (1.29 tonnes/ha) in the late 1970s and 1980s. More recently, from 2000 to 2013, canola yields increased by 48 lbs/ac/year (54 kg/ha/year), primarily due to the introduction of herbicide-tolerant/ hybrid varieties.

In summary, studies focusing on the Prairie provinces in Canada have shown accelerated changes in several climate parameters over time, affecting cropping areas and crop yields. However, uncertainties remain regarding the relationship between crop yield and long-term climate changes.

Bruce Barker divides his time between CanadianAgronomist.ca and as Western Field Editor for Top Crop Manager. CanadianAgronomist.ca translates research into agronomic knowledge that agronomists and farmers can use to grow better crops. Read the full Research Insight at CanadianAgronomist.ca.

Brought to you by DOES THE FUTURE OF AGRICULTURE SEEM GREY TO YOU?

Agriculture in the Classroom is cultivating curiosity by providing hands- on, immersive learning experiences to educate and engage students. The next generation of farmers, policy-makers, and innovators is in the classroom today. Together, we can inspire young people to drive our industry forward.

Change the future at aitc- canada.ca

To our valued readers, contributors and advertisers,

As we celebrate our golden anniversary of sharing trustworthy, research-focused crop production and agronomy insights and trends with Canada’s farmers, we extend our gratitude for your support and partnership throughout the decades.

Your trust in us has been our greatest reward, inspiring us to continually strive for excellence and relevance.

Thank you for being an integral part of our story,