MAKE WEEDS FEEL THE BURN.

Our homegrown innovation gets the tough ones.

Designed specifically for Western Canadian growers, Smoulder® herbicide helps incinerate tough weeds at pre-seed timing, to give cereal crops a cleaner start. It takes out emerged broadleaf weeds, including biotypes of kochia resistant to Group 2, 4 and 9 chemistries. Smoulder also controls winter annuals and perennials, like narrow-leaved hawk’s beard, dandelion and Canada thistle. And it keeps flushing weeds out with its extended residual activity. Go to agsolutions.ca/Smoulder and get ready to make weeds feel the burn.

directions.

For over 100 years, pest surveillance activities have been documented on the Canadian Prairies. Many of the early surveillance and monitoring protocols continue today and assess pest populations, track changes and new arrivals, and develop forecasts and management strategies. This long-term continuous surveillance and history of pest populations for crops in Western Canada and the advancements of new tools and resources provide strong benefits to farmers.

Preliminary research shows no response.

Rates vary depending on yield potential.

Online platform for weed management.

Genetic testing is part of management.

Choosing the best long-term investment.

by Kaitlin Berger

Autonomous taxis, tractors and beyond

I still remember the initial feeling of horror when I saw an autonomous taxi for the first time. I was walking the streets of San Francisco a few years ago and noticed it pulling up to a stoplight. My friends and I started nudging each other. “Hey, is it just me – or is that car missing a driver?” Once we spotted one of these vehicles, we started seeing them everywhere, but none of us could work up the courage to hop in the back seat.

I recently caught up with Darrell Petras, CEO of the Canadian Agri-Food Automation and Intelligence Network (CAAIN) to record a podcast episode on Inputs by Top Crop Manager. I wanted to hear his thoughts on artificial intelligence (AI) in agriculture – and what that actually looks like right now. I have to say his perspective was a lot more optimistic than my existential dread for autonomous vehicles.

The

While agriculture is facing some considerable challenges right now – from labour issues to lost productivity – Petras is confident these challenges can be at least partially addressed with new applications of AI. A good example is precision agriculture. Machine-learning AI can improve field mapping and ultimately lead to more precise use of inputs. Rather than applying the same rate of fertilizer every year to the entire field, machine-learning AI can determine the exact amount needed.

Machine learning also has the potential to improve quality assurance. For example, a company called Super GeoAI Technology Inc. (SGA) is using AI to count and grade grain based on photos in an expanding database. Automation is another area Petras thinks will bring radical improvements, especially when it comes to solving labour challenges. Autonomous tractors are an obvious example, but he’s also seeing greenhouse operators getting good results with using robotics to harvest – for example – the best berries on a plant.

In the next five years, Petras hopes to see a more defined pathway for testing and adoption of technology that reaches farmers. The good news is CAAIN supports the Pan-Canadian Smart Farm Network, which provides the capacity to test new technology against the industry standard in broad-acre situations in various regions across Canada.

Petras’ optimism is contagious and, if you listen to the podcast, you may come away from the discussion with the feeling that the future is bright for AI in agriculture – and for those bold enough to adopt it.

Editor KAITLIN BERGER (403) 470-4432 kberger@annexbusinessmedia.com

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

(416) 510-5187 lsamel@annexbusinessmedia.com Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW

Potassium and sulfur fertility for lentil

Preliminary research results show no response.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Knowing what you don’t know is the first step in enhancing agricultural production. In the case of Saskatchewan lentils, the unknown was potassium (K) and sulfur (S) fertility. A research project in Saskatchewan ventured into the unknown.

“This is something that was identified as a priority by the SaskPulse Board and research staff in the winter of 2022/23 and it was they who initiated the project,” says Chris Holzapfel, research manager with the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) at Indian Head, Sask. “They wanted to explore the potential for responses to K and S in order to help fill in gaps in some of the fertility research we’d done with peas and lentils recently.”

Holzapfel says that with peas, the focus was on phosphorus (P) and sulfur, while also exploring potential responses to starter and in-crop nitrogen (N) applications. In follow-up work with lentil, it focused more on P and N fertilizer responses while aiming to keep K and S non-limiting. He says that, while expectations were not particularly high for K and S response, the work was conducted to generate some information on this topic, regardless of the outcome, to help develop some broader and more balanced fertility recommendations for lentil.

The overall objectives of this project were to demonstrate, for a range of Saskatchewan environments, the yield and quality response of small red lentils to varying rates and combinations of potassium and sulfur fertilizer. Field trials were conducted at Swift Current, Scott and Indian Head in 2023 and 2024.

The fertility treatments consisted of a combination of three K and S rates plus two control treatments. One of the control treatments was to show the potential impact of no N, P, K and S fertilizer. Since N was not balanced across treatments, the second control was to determine whether responses to ammonium sulphate (AMS) were due to the S or the N that is provided by this product.

For all treatments except the control without any fertilizer, P was applied at 40 lb. P2O5/ac. (45 kg/ha) as mono ammonium phosphate. All fertilizer was side-banded during seeding and all treatments received a label recommended rate of granular rhizobial inoculant.

CDC Proclaim CL lentil was direct seeded into cereal stubble at a target rate of 19 seeds per square foot (190

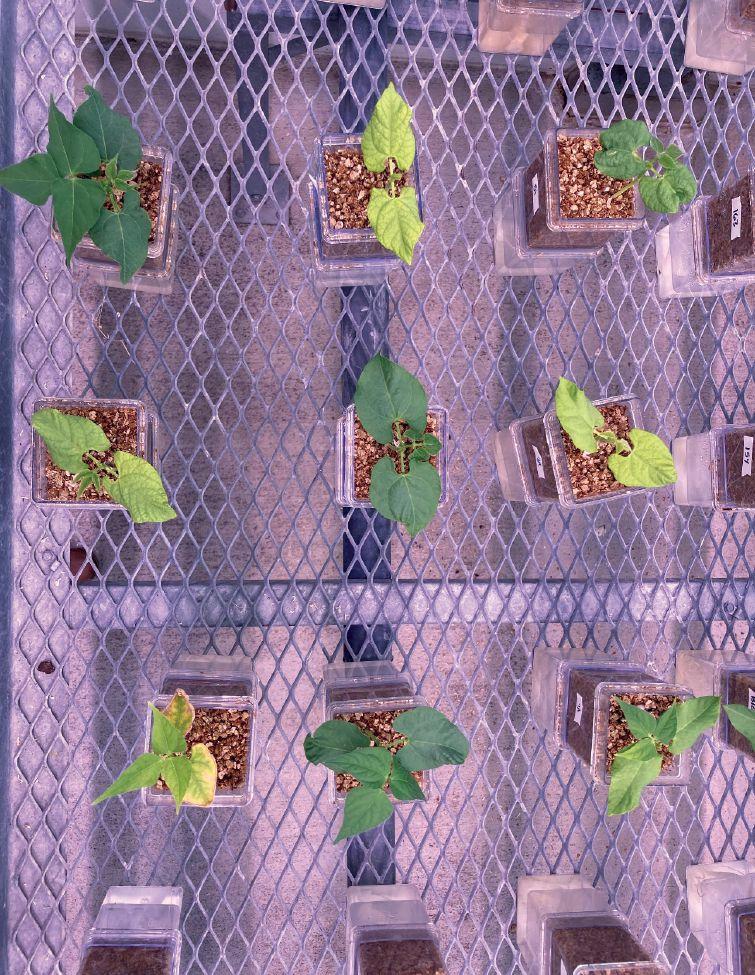

Photo courtesy of Chris Holzapfel.

seeds/m 2). Weeds were controlled with registered pre-emergent and in-crop herbicide applications, and pre-harvest herbicides or desiccants were utilized at the discretion of individual site managers. Insecticides were applied as required.

All three locations experienced varying levels of unfavourable growing conditions with above normal temperatures in 2023. Swift Current was near normal for precipitation but had severe hail damage on July 22, 2023 with an estimated 60 per cent yield loss. However, the Swift Current data was considered acceptable because the damage was uniform across the plots. Scott received 70 per cent of normal precipitation and 49 per cent at Indian Head.

Soil test analyses found K concentrations in the 0 to 15 cm depth at 484 ppm at Indian Head, 205 ppm at Scott and 224 ppm at Swift Current. Sulfur concentrations at the 0 to 15 cm depth were 11.6 lb./ac. (13 kg/ ha) at Indian Head, 16 lb./ac. (18 kg/ha) at Scott and 14.25 lb./ac. (16 kg/ha) at Swift Current.

NO RESPONSE TO K OR S

Data collected included spring plant density, seed yield, test weight, seed weight and seed protein. In 2023, there were no significant differences between treatments for any of these measurements. 2024 data is still being analyzed, but Swift Current suffered another drought and Indian Head had root rot issues with their plots.

With relatively high levels of K in the soil tests, and most Saskatchewan soils having adequate fertility, soil testing is still recommended to determine if K fertilizer is recommended. This is especially important in sandy Black and Gray soils where K deficiencies may occur. Similarly, there is no specific critical level for S in lentil, but deficiencies may occur on sandy soils, and an other consideration is that S fertility can be very vari able across fields.

However, over the longer term, K and S fertility may become an issue, and the strategy of applying small amounts of these nutrients to help maintain fertility could be beneficial.

“While responses to potassium and sulfur may be small and less consistent than those we might expect for phosphorous in pea and lentil, deficiencies are still possible and applying low levels of these nutrients might be considered to be relatively inexpensive insurance,” says Holzapfel. “There are far worse places to spend input dollars than balanced nutrient applications, especially if we consider long-term soil productivity and fertility. That being said, if including potassium and sulfur in your blend creates any logistic headaches or other seed-placement concerns, or you simply need to keep costs down, the risks associated with excluding them would be quite low for most Saskatchewan farmers unless there is a specific reason to expect a potential deficiency.”

With the second-year results pending, Holzapfel recommends that farmers use soil tests to help identify any fields that may have a higher potential

in

(K2O) and

demonstrations conducted at Indian Head, Scott and Swift Current in 2023

Drawing the line on chaff lining

Research looks at harvest weed seed control potential.

BY BRUCE BARKER

As an entry level harvest weed seed control (HWSC) program, chaff lining is an affordable, alternative tool to help manage the weed seedbank. Research by Michael Walsh in Australia, where HWSC was pioneered, found that a chaff line can create environments favourable for seed survival while still restricting weed seedling emergence, and that chaff lining is the ideal initial HWSC system for growers to begin adoption. Research in Canada looked into the potential for chaff lining on the Prairies.

“I honestly think some form of harvest weed seed control, or preventing seeds from going into the seedbank, is going to be needed for long-term weed management to be successful. To me, the best option for that is an impact mill. However, I understand that the cost and the need for a larger class combine may restrict the availability of the mills for growers,” says Breanne Tidemann, weed scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta. “Chaff lining is another form of HWSC with a much lower price tag than the mills – about $5,000 to have one fabricated, less if you can do the welding and fabrication work on farm. So, to me it made sense to at least take a look at the potential for this HWSC tactic to be used in western Canada.”

In Australia, HWSC methods include narrow windrow burning, chaff lining/tram lining, chaff collection, bale direct systems and physical impact mill systems. Chaff lining was an initial entry point into HWSC, but impact mills are becoming more widespread.

Tidemann, who has been researching HWSC for over 10 years, ran field trials at Melfort, Sask. and Lacombe and Lethbridge, Alta. in 2021/22 and 2022/23. Chaff lining chutes were designed and manufactured for each combine at the locations. Four field areas were seeded to wheat, canola, peas, barley and/or rye, depending on the location.

One hundred viable seeds of wild oat, cleavers, volunteer canola, kochia (Lethbridge), green foxtail and wild buckwheat seed were placed in pouches surrounded by wire mesh to prevent rodent damage. Eight pouches of each species were placed in each field, four under chaff lines and four beside chaff lines. The pouches were left to overwinter and, just prior to

seeding the next spring, the pouches were shipped to Lacombe and analyzed for germination and seed viability.

In addition, chaff lines were monitored for weed and crop emergence in subsequent crops.

Greenhouse pot studies were also conducted at Olds College, Alta. to assess the effect of wheat, pea, canola, barley and rye chaff volume on wild oat and volunteer canola emergence. Chaff volumes were 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 42 t/ha, which were the ones that were tested in Australia.

“Completely up front, chaff volumes have not been studied in Canada. In Australia, they get approximately 300 kg of chaff from 1,000 kg of wheat yield. You wouldn’t expect the same rate of chaff production from the other crops, but we don’t have those values for the other crops as far as I am aware,” says Tidemann. “So, we used the same values as used in the Australian research.”

Tidemann says there were a couple reasons she did not use higher chaff volumes. First, she tried to collect and measure chaff volume in the lines but couldn’t correlate them to yield. In addition, it was nearly impossible to get that much chaff on a pot or tray for the

ABOVE A fabricated chaff line attachment. All photos courtesy of Breanne Tidemann.

THE LEVEL OF PRECISION YOU’VE COME TO EXPECT FROM US IS NOW AVAILABLE ON YOUR SPRAYER.

Take charge of your spraying accuracy through independent control of rate and pressure with SymphonyNozzle™ and a Gen 3 20|20® monitor. Together they reduce over-application with swath control and level out inconsistent application on turns. Take your sprayer a step further and add ReClaim™, our recirculation system.

WE BELIEVE IN BETTER SPRAYERS WITH BETTER CONTROL.

study. Other variables that affect chaff volume include combine header width and the width of the chaff line, crop and crop variety.

Tidemann is still working through the data, but some preliminary trends are emerging.

WEED SEED VIABILITY INCREASED

In most cases, weed seed viability increased after overwintering in the chaff line. Wild buckwheat viability increased by six per cent under barley chaff, volunteer canola by approximately 25 per cent under barley and pea chaff, cleavers by 13 per cent under all chaff types, green foxtail by 2.5 per cent and wild oat by five per cent. Kochia seed viability decreased by 18 per cent when under pea chaff.

“In most cases, the viability actually increased under the chaff lines rather than decreasing. This happened more frequently in our study than in the studies conducted in Australia,” says Tidemann. “This is likely due to the difference in conditions between weeds in chaff lines over the summer in western Australia compared to overwintering weeds in western Canada. The chaff line in western Canada likely provided some protection from extreme cold weather conditions, allowing the seeds to be protected from those extremes.”

Preliminary results found that weed emergence was not statistically affected by chaff lines, but there was a trend to nearly half the emergence under chaff lines. “While weed emergence was reduced in chaff lines and we successfully collected a number of weeds in the chaff line, crop emergence where crop seeding rows intersected the chaff lines was also reduced,” says Tidemann.

The greenhouse pot studies demonstrated that with enough chaff volume, weed seed emergence could be reduced, particularly for volunteer canola says Tidemann. Wild oat did not show as much response to heavy chaff, likely due to the ability of wild oat to emerge from depth. This indicates that chaff lining, which appears to be primarily a physical mechanism to block emerging weeds, may be most effective on small seeded broadleaves, but less effective on larger seeded weeds such as wild oat which can emerge from depth, she says.

Tidemann looked at what weeds were captured in the chaff lines. Unsurprisingly, there were differences by location, but the primary seeds collected in the chaff were volunteers of the crop that was grown. In addition to those volunteers, at Lethbridge, the most commonly collected weed in the chaff line was kochia. At Lacombe, it was wild oat, sow thistle, cleavers and green foxtail. Melfort collection included cleavers, lamb’s quarters and Canada thistle.

ABOVE Weed emergence was not affected by chaff lines.

“Chaff lining is a cheaper HWSC tool. You can use it to reduce weed emergence, although there will likely also be reductions in crop emergence where crop is seeded through or into the chaff line.”

While disappointing, the results are not necessarily surprising to Tidemann. She says chaff lining has a good fit in Australia because many growers are on controlled traffic farming systems. Here, most of the chaff lines would be disturbed which alone will reduce the impact they can have and, with increased weed seed viability, could actually increase weed pressure around the chaff lines that are disturbed by seeding or tillage rather than undisturbed in controlled traffic farming tramlines. Another difference with Australia is there is more opportunity for weed seeds in chaff lines in Australia to degrade/compost over the summer season, while ours quickly enter a frozen state which inhibits any type of degradation.

Still, the research was valuable in that it shows the potential – or possibly the lack of potential – on the Prairies. Tidemann says she has had lots of questions from farmers in the last year or so who are interested in HWSC but don’t want to jump directly to the mills.

“Chaff lining is a cheaper HWSC tool. You can use it to reduce weed emergence, although there will likely also be reductions in crop emergence where crop is seeded through or into the chaff line,” says Tidemann. “However, it doesn’t provide a long-term solution or kill the weed seeds in the process. If you want to not only reduce the emergence, but also reduce the viability, a solution like an impact mill is a lot more effective.”

“Chaff lines could be used to determine your ability to capture weed seeds in the chaff with your combine or combine settings if there is skepticism that a weed you are hoping to target is targetable with HWSC,” says Tidemann. “In addition, if you can concentrate those weed seeds into a chaff line, maybe you can use targeted herbicide applications to just those lines, rather than having to do a broadcast application.”

New Extinguish™ XL herbicide provides effective control of tough-to-kill broadleaf weeds in wheat and barley in an easy-to-use formulation. Delivering a combination of high performance and value, it’s a powerful solution to all your weed control problems.

Fine tuning wheat seeding rates

Rates vary depending on yield potential.

BY BRUCE BARKER

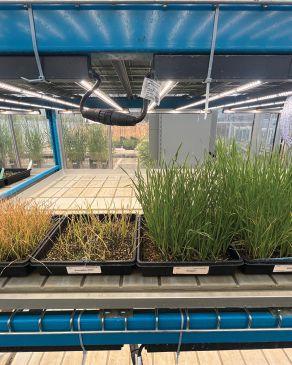

How much spring wheat do you seed per acre? A bushel? A bushel and one-half? Throw that old notion out and think plants per square foot. Current Saskatchewan recommendations are 21 to 27 plants per square foot (215 to 275 plants/m2). But is there an opportunity to fine tune those rates further?

“There is sufficient research to indicate that the optimum seeding rate of wheat may vary depending on environmental conditions,” says Jessica Enns, research manager with the Western Applied Research Corporation at Scott, Sask.

Enns was the principal investigator on a 2023 research project at six Agri-ARM sites in Saskatchewan. The research was conducted at Melfort, Yorkton, Swift Current, Indian Head, Prince Albert and Scott, Sask. The objective of the study was to evaluate the ideal seeding rate for spring wheat under various environmental conditions. The trial included seven seeding rates targeting plant stands starting at 10 plants/ft2(108 seeds/m2) and increasing in increments of 5 plants/ft2 (50 seeds/m2) up to 40 plants/ft2(432 seeds/m2). So, the rates targeted 10,

ABOVE Research refined wheat seeding rates.

15, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 plants/ft2.

A typical hard red spring wheat variety that was common to the area was seeded into canola stubble at most sites, except Swift Current and Yorkton where it was seeded into durum and wheat stubble. Row spacing varied by site and was eight inches at Swift Current, 10 inches at Scott and Prince Albert and 12 inches at Melfort, Indian Head and Yorkton. Fertilizer was applied based on soil test recommendations – and weeds, diseases and insects were controlled as needed.

Plant emergence was measured at two weeks after emergence. Head density was counted when head emergence was complete. Tillering was calculated by dividing the plant density by the head density to provide the number of tillers per plant. Lodging was evaluated at physiological maturity. Head length was also measured. Yields were adjusted to 14.5 per cent moisture content. Protein was collected as an indicator of seed quality. Head size (seeds/head) was calculated based on yield, head density and seed weight.

The mean monthly temperature and cumulative precipitation were recorded at all six sites for the months of May to August. Overall, the above-average growing season temperatures and below average precipitation indicated relatively drought-like conditions for all six sites.

Photo courtesy of Bruce Barker.

You can’t control what happens to your canola, but you can control how it responds. WAVE biostimulant from UPL, your source for INTERLINE® herbicide, improves nutrient uptake for enhanced plant vigor, growth and overall health. This easy-to-use, naturally derived abiotic stress mitigator increases pro t potential by reducing the costly effects of environmental stressors such as excessive moisture, drought and cold. Field trials have also shown a yield increase of almost 2 bu/A.*

TAKE SOME OF THE STRESS OUT OF YOUR SEASON. ASK YOUR RETAILER ABOUT WAVE BIOSTIMULANT TODAY.

Unpacking the Prairie Weed Monitoring Network

Comprehensive online platform for integrated weed management.

BY DONNA FLEURY

The Prairie Weed Monitoring Network (PWMN) was launched to guide weed monitoring and biovigilance strategies for the Prairie region. This new network brings together a coordinated collaboration of federal, provincial and academic weed science experts to provide the agricultural industry with information, resources and tools for weed management in annual cropping systems.

“The PWMN is designed after the successful models of the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network launched in the late 1990s, and the more recent Prairie Crop Disease Monitoring Network in 2018,” says Charles Geddes, weed scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “As co-lead, together with Julia Leeson, weed monitoring biologist at AAFC Saskatoon, we are pleased to lead this third network in collaboration with a whole network of specialists across the Prairies. Funded in 2023 by the AAFC Integrated Crop Agronomy Cluster, the PWMN completes the three pest discipline networks across the Prairies.”

One of the first objectives of the network was to establish the PWMN Prairieweeds.com website, which was developed and hosted by Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF), and launched in spring 2024. The website will serve as the digital home of the PWMN, offering a wealth of resources and up-to-date information on weed abundance, herbicide resistance and integrated weed management specific to the Canadian Prairies.

“The foundation of the network was built on some of the historical weed assessments completed across the Prairies for many years,” explains Geddes. “One of the most important is the weed abundance surveys that have been conducted across the Prairies for decades.

Currently led by Julia Leeson, weed abundance surveys are conducted by species in over 4,000 annual crop fields across this Prairies. This is a large undertaking and one of the most comprehensive activities on weed surveillance at a global level. The survey methodology has remained the same since the 1970s, which enables us to look at how the abundance of weeds and their frequency has changed over time, as well as changes in cropping systems. It’s a very nice resource to have here on the Prairies.”

In the early 2000s, the herbicide resistance surveys were initiated by Hugh Beckie, (retired) weed scientist at AAFC Saskatoon. The same survey methodology continues and, similar to the weed abundance surveys, assesses the distribution and frequency of different types of herbicide resistance and how they have changed over time. This pre-harvest survey captures all uncontrolled weeds in annual crop fields, with the exception of kochia and Russian thistle. A post-harvest weed resistance survey was added in 2010 to focus specifically on kochia and Russian thistle, which both tend to have mature seeds later in the growing season, and collection post-harvest improves resistance diagnostic testing.

Geddes notes that the final reports from all the weed surveys are available on the PWMN website as they are completed. The weed surveys usually cover a different province each year with the exception of Saskatchewan which is completed over two years.

A second priority for the PWMN is to build on all the weed surveys and assessment datasets and provide value-added components for the agricultural community. “This is a fairly novel undertaking and we are just getting started on a longer term vision,” says Geddes. “The goal is to utilize datasets to develop risk assessments and forecasting on how changes in either crop

ABOVE Wild oat seed head in a canola crop.

All photos courtesy of Charles Geddes, AAFC.

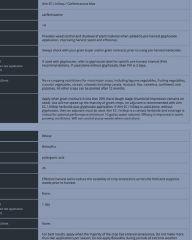

RIGHT Various wild oat populations from Alberta three weeks after a herbicide treatment. Each tray is a different wild oat population collected from the 2023 Alberta survey.

management or climate may affect weed populations in the future.”

The development of a spatial risk assessment for the evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds is the first activity. Researchers are integrating comprehensive data for the spatial distribution of weed abundance with species-specific biology and ecology, level of herbicide resistance selectivity, cropping systems information and herbicide use or sales data. The results can help inform where selection pressure is occurring and the weed density in those regions. Ultimately that comes together as maps showing the spatial risk assessment of herbicide resistance.

“A second activity is to combine weed abundance data with crop management and weather station data to show how weed communities respond to either changes in management or changes in climate,” adds Geddes. “As we look forward to potentially variable weather conditions predicted under a changing climate, this can help us understand how these factors might impact different weed species and their composition under annual crop production and changes that may occur.”

“We are still in the early days of the network, and expect by the end of the project to have additional maps, forecasting information and other resources available on the website. We are also committed to developing factsheets and have just released the first one on herbicide-resistant weeds in the Prairie region. The website also includes access to peer-reviewed articles, research posters and links to other important resources.”

TOP WEEDS TO WATCH AND SCOUTING STRATEGIES

The weed abundance survey results are also very useful to see how weed populations are changing over time. The surveys show that some weeds are increasing in abundance across the Prairies. One of those is foxtail barley, a native plant of the Prairies, that is increasing in weed abundance across the Prairies and especially in Alberta. False cleavers, kochia and some pigweed species, especially in Manitoba, are increasing as well.

“Herbicide resistance is also top of mind, with kochia a main priority,” says Geddes. “In kochia, the fifth herbicide mode of action with herbicide resistance has been identified, as well as stacking of multiple herbicide resistance traits. Group 14 resistance in kochia is the most recent herbicide resistance identified over the past few years and, although it is currently at low abundance, it is at a high risk of spreading. The spread of herbicide

resistance in kochia is extremely quick and of concern. There is also a big risk of some invasive Amaranth weed species and herbicide resistance, particularly in Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan. Herbicide-resistant waterhemp has already established in Manitoba over the past few years and is spreading. Palmer amaranth has been introduced into a few locations in Manitoba, but so far hasn’t spread.”

Farmers and agronomists are also important collaborators in the network. Scouting fields and knowing the different species present in individual fields is very important for matching proper control options and planning good crop rotations. “It is very important to scout fields before you spray to make sure you are using the right product to target the specific species in the fields,” emphasizes Geddes. “Scouting again three to four weeks after spraying is the best time to look for potentially herbicide-resistant species that may not have been controlled by the herbicide application.”

If suspected herbicide-resistant weeds are identified, it’s important to take action and send weed samples to one of the several diagnostic labs across the Prairies. These labs generally provide testing for known types of resistance that occur over broad acres on the Prairies. Geddes adds that research labs, such as the one he leads, focus on novel herbicide resistance that are not known to occur in the region. If farmers or agronomists suspect they have a new type of resistance, they can reach out and the labs will work with them to confirm resistance and develop practices to get it under control.

“The PWMN already has several resources available for a wide range of potential audiences. Researchers looking for the latest information on the status or abundance of weeds or herbicide resistance and other specialists, agronomists and farmers now have access to all available information,” says Geddes. “There are only a few weed-based researchers in the region and we rely on all agronomists and other industry members to help share information generated by the network. The website makes these resources readily available and extends the outreach throughout the network. The current project is funded to 2028, so watch for additional resources, reports and tools to become available and posted to the network going forward.”

The PWMN is funded by Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership – Integrated Crop Agronomy Cluster 2, Alberta Canola Producers Commission, Alberta Grains, Manitoba Canola Growers Association, Manitoba Crop Alliance, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, Prairie Oat Growers Association, Saskatchewan Oilseeds, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission and Western Grains Research Foundation.

Fine tuning wheat seeding rates

PLANT DENSITIES INCREASED

Splitting the sites into low and high moisture groups, plant densities increased for each group as seeding rate increased, but slightly differently. At low moisture sites, there was a significant linear response to seeding rates with plant densities increasing at a rate of 0.69 plants/ft2 for each increase in seeding rate. The lowest seeding rate of 10 seeds/ft2 resulted in a plant density of approximately 10 plants/ft2 rising to about 30 plants/ft2 at the highest seeding rate.

At the high moisture sites, plant densities increased as seeding rates increased but began to plateau at higher seeding rates. The lowest seeding rate had about eight plants/ft2 tapering off to about 28 plants/ft2 at the highest seeding rate.

Similarly, head densities tended to increase as seeding rates increased at all locations. However, head densities increased more with increasing seeding rates at the high moisture sites than low moisture sites.

As seeding rates increased, tiller density, head length and head size decreased at all locations, but to a greater degree at high moisture sites than low moisture sites. Lodging also increased with increasing seeding rates at high moisture sites.

YIELD DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SITES

At low moisture sites the yields tended to decrease as seeding rates increased. At Indian Head, yields decreased from 76.1 bu./ac. at 10 seeds/ft2 to 74.7 bu./ac. at 40 seeds/ft2. For the Swift Current and Melfort sites, the yields were unaffected by seeding rate treatments.

“High seeding rates generally result in high plant populations, which compete more strongly for resources. When resources are limited, such as in dry conditions, high plant populations cannot acquire the necessary resources to be productive. Consequently, more plants mean that each individual plant may receive less water. Therefore, plants can become stressed, which negatively affects their growth, root development and productivity,” says Enns.

On the other hand, Enns says that when plant populations are low, limited resources are better utilized by plants, resulting in greater productivity and yields. She says this was the case in this study, as low seeding rates resulted in low plant populations and greater yields with greater utilization of a commonly limited resource such as moisture.

At high moisture sites the yields tended to increase as seeding rates increased. At Scott, yield increased by five bushels per acre from the lowest to highest seeding rate. At Yorkton, there was a 10 bu./ac. difference between the lowest and highest seeding rate. At Prince Albert, the yields increased as seeding rates increased and peaked at 35 seeds/ft2

“There is sufficient research to indicate that the optimum seeding rate of wheat may vary depending on environmental conditions.”

“When moisture is not a limiting factor, higher plant populations are able to acquire the necessary resources for growth and development. Additionally, greater plant populations can result in more potential for yield as the quantity of yield-determining factors also has the potential to increase,” says Enns.

The study found that head density was the most strongly correlated to yield. At high moisture sites, head density increased with increasing seeding rate, resulting in higher yields. Enns says there is often a diminishing return for increasing seeding rate, where high plant populations cannot acquire the amount of resources needed to support higher yields.

“While a quadratic yield response was not significant in this study, the confounding results indicate that optimum yields were most consistently achieved at 30 seeds/ ft2,” she says.

Enns says the results show that the seeding rates to optimize yield vary slightly depending on moisture conditions. Based on the results of this study, seeding rates at 20 seeds/ft2 in low moisture conditions and 30 seeds/ft2 in high moisture conditions can consistently optimize wheat yields.

“It is difficult to predict moisture conditions for the growing season at time of seeding. But a basic understanding of this relationship between plant populations and moisture availability can help producers manage their wheat and mitigate risk,” says Enns. “Additionally, applying this concept to variable rate seeding may help producers optimize their yield and economics for wheat at the field level.”

OTHER AGRONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Higher seeding rates can help plants better tolerate biotic and abiotic stresses, particularly when resources are not limited says Enns. One of the greatest benefits of increased seeding rates is greater crop canopy coverage. This can improve the competitive ability of the crop against weeds for greater weed control without relying as strongly on herbicide control. Additionally, a greater crop canopy provides more coverage of the soil which can reduce soil moisture losses through evaporation.

Enns says that denser crops may be able to better moderate the microclimate within the crop and stabilise temperature effects such as extreme heat. Another benefit of denser plant populations, particularly in wheat, is the reduced number of tillers. This can improve the precision and efficacy of fusarium head blight (FHB) fungicide applications for greater disease management.

“Ultimately, while low seeding rates may be beneficial when moisture is limiting,” says Enns, “higher seeding rates provide many agronomic benefits that low plant populations do not.”

“Burn in heck, weeds. Burn in heck!”

The speed and performance of new Intruvix™ II herbicide is so darn good, folks can hardly contain their excitement. By applying it with glyphosate before planting cereals, they’re saying goodbye and good riddance to narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, volunteer canola, kochia and many other problem weeds. Enjoy cleaner fields, faster, while protecting your future glyphosate use. Cheese and crackers, how easy can you get?

Clean

is good

REWARD OFFERED. GET CASH BACK WHEN YOU BUY INTRUVIX™II HERBICIDE

Soil carbon stock options

Choosing the best long-term investment.

BY JOEY SABLJIC

We’ve heard the agronomic talks about why we need to return crop residues to the soil after grain harvest. Residues protect against erosion. They help build up soil organic carbon, repair nutrient imbalances – and more. These are all valid, agronomically sound points, especially in a dryland cropping system. The question is whether growers are also leaving money out in their fields each harvest by returning residues to their soils. After all, there are plenty of examples where crop residues have been collected and turned into highly profitable bio-products like straw board, cellulosic biofuels, pelleted fuels, fibres and other environmentally conscious materials. Even with this potential, perhaps residues should be left alone for the sake of long-term soil carbon stocks and soil health.

An Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research team is looking to see if growers can go beyond grain and harvest a portion of crop residues without hurting soil health. Leading these efforts is Benjamin Ellert, research scientist and biogeochemist, whose area of expertise is in understanding how elements like phosphorus, nitrogen and carbon move through the environment. “For us to get a true sense of how crop residues impact soil carbon and soil health, we can’t just go back one or three years, we need to look at multiple decades,” says Ellert. “You aren’t going to increase or deplete your soil carbon stocks overnight.”

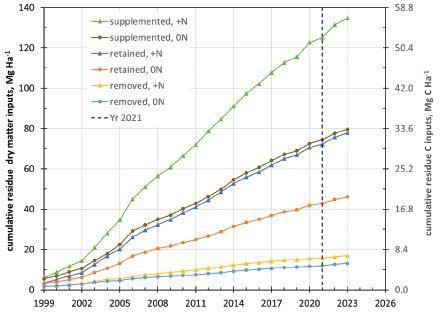

According to Ellert, this crop residue study began back in 1999 at AAFC’s Lethbridge Research Centre, using large plots under dryland spring wheat cropped continuously in a zero-till system. Soil samples were collected periodically, with the most recent set of soil cores collected after the study had been ongoing for over 20 years.

MEASURING RESIDUE TREATMENTS

The main treatment in the study involves three different levels of crop residue: removed, retained or supplemented. In the first ‘residues retained’ treatment, any residues that came out the back of the combine during grain harvest were deposited on the soil. This, says Ellert, is meant to simulate typical dryland cropping practices. In the second ‘residues removed’ treatment, all plant material above cutter bar height was removed from the plot with only standing stubble left behind. Finally, the

third ‘supplemented residues’ involved leaving residues after combining - like the ‘residues retained’ treatment – but then bringing over additional residues pulled from the ‘residues removed’ treatment plot.

Ellert and his team also included a second treatment to look at the impact of nitrogen fertilization on residue and soil carbon levels.

SOIL CARBON STOCKS ARE A LONGER-TERM INVESTMENT

ABOVE Hay inverter used to transfer windrows from ‘residues removed’ to ‘residues supplemented’ treatment.

Despite big differences (five to 52 metric tonnes residue carbon per hectare) in the amounts of crop residue added to the removed, retained and supplemented treatments, they only found small increases in soil organic carbon. In fact, a detailed analysis of soil organic carbon stocks showed that in the ‘residues retained’ treatment without fertilizer, only three percent of all the residues added over 23 years were actually retained in the soil. In the ‘residues supplemented’ treatment, about seven per cent of those residues were retained – and with a much higher residue input.

However, when fertilizer was added, yields and residue inputs increased, and each of the residue treatments told a slightly different story. Ellert says these plots showed the largest increases of soil carbon stocks. For example, with nitrogen fertilizer, soils in the ‘residues returned’ plot retained 17 per cent of the carbon added as residues over 23 years. “Still, across all three residue treatments with fertilizer, we were only seeing about 15

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Ellert, AAFC.

per cent of the carbon from residues being retained in the soil, on average,” explains Ellert. “We suspect that the more sizeable increase was probably due to the nitrogen fertilizer effect, which could’ve helped increase plant root mass.”

In both sets of treatments – nitrogen and no nitrogen

deeper, there was barely any difference, despite the massive amounts of carbon inputs going on the surface.

Another key factor in soil carbon levels, says Ellert, could be natural decomposition of crop residues. “The changes in soil organic carbon stocks, ranging from 43 to 50 metric tonnes of soil organic carbon per hectare in an equivalent soil mass approximately 15 cm thick, are small because those crop residues decompose,” explains Ellert. “So, really, any gains in soil organic carbon stocks or general soil health happen over a very long term – as in, decades.”

In other words, pulling residues out of your field for one season or another isn’t going to cause a sudden, dramatic decline in soil carbon levels. Do it on a continual basis, however, and you could start to see an impact.

EXPORTING RESIDUES COULD COME AT A COST

While there isn’t an easy, straightforward answer as to whether it’s beneficial to extend the harvest of cereal crops to include some portion of the non-grain residues, Ellert says they have provided a baseline to forecast potential changes in soil organic carbon stocks. “In productive areas of the Black soil zone where markets for cereal straw are most likely to develop, exporting those residues is likely going to come at a cost to plant nutrients, like potassium, and decrease soil organic carbon,” he explains.

Jugs, drums & totes need to be rinsed ; bags need to be empty Please prepare them properly so they can be accepted. Keep it up! You are making a difference. Most Alberta & Manitoba jug collections are now at retail; please use QR code

Year a er year, Canadian farmers are keeping more ag plastics out of landfills.

Bring your empty and rinsed pesticide and fertilizer jugs, drums and totes for recycling; as well as seed, pesticide and inoculant bags for responsible disposal.

Uncovering clubroot’s complex interactions with canola

A journey toward more durable clubroot resistance in canola.

BY CAROLYN KING

Clubroot-resistant canola varieties are a crucial part of strategies to manage this devastating disease, but the clubroot pathogen excels at defeating current resistance genes, especially if only a single resistance gene is involved.

That’s why Christopher Todd and his colleagues at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) are working to identify many different genes involved in many different ways of combatting the clubroot pathogen.

Their long-term goal is to contribute toward development of stacked clubroot resistance involving multiple modes of action so canola varieties will have much longer-lasting, broad-spectrum clubroot resistance.

Clubroot is caused by a soil-borne microbe called Plasmodiophora brassicae. The pathogen colonizes the roots of canola and other Brassica plants and causes clubs to form on those roots. The clubs prevent water and nutrient uptake, causing the plant to wilt and die. Yield losses can be very severe in susceptible canola varieties in heavily infested fields.

The clubs on one infected canola root can produce

TOP Researchers are searching for ways to provide canola with more durable resistance to clubroot, a major disease.

billions of tiny resting spores, which can survive in the soil for many years. Because the pathogen produces so many spores and is genetically diverse, it is able to quickly adapt and overcome a single resistance gene in a canola cultivar.

EFFECTS OF EFFECTOR PROTEINS

Todd and his USask colleagues, Peta Bonham-Smith and Yangdou Wei, are delving into the complex molecular pathways and processes involved in clubroot infection. Their studies include work with canola as well as Arabidopsis thaliana, a Brassica cousin of canola that has a much smaller genome, a faster life cycle and a smaller plant size, making it very convenient for research.

Their research focuses on clubroot effector proteins. “Effector proteins are small proteins that are made and secreted by a pathogen. They interact with the host plant’s cells in some way that either manipulates or interferes with the normal plant function in a way that facilitates a successful infection by the pathogen,”

Photo courtesy of Canola Council of Canada.

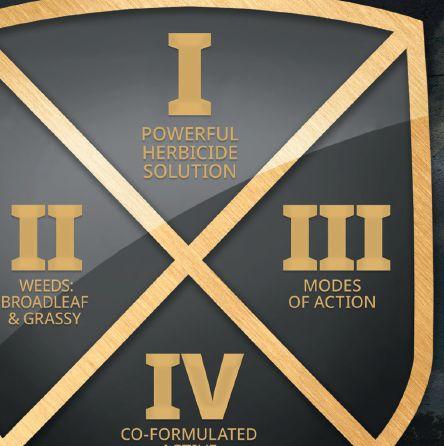

CROSS-SPECTRUM HERBICIDES CHECK EVERY BOX FOR CEREAL GROWERS

With countless herbicide products on the market, it can be daunting for cereal growers to determine the combination that best suits the needs of their crops, weed spectrum and rotation.

Cross-spectrum herbicides have become increasingly popular in Western Canada over the past decade as farmers look for more convenient ways to control weeds that typically affect crops in their soil zone, without having to sift through herbicide guides and product labels.

Checking all the boxes for cereal growers, cross-spectrum herbicides from Corteva Agriscience™ deliver grass and broadleaf weed control in a powerful all-in-one solution. Designed for the widest possible weed spectrum coverage, overlapping control and tested for compatibility, they are packaged at optimum mixing rates for peak convenience and effectiveness.

Four reasons to take a cross-spectrum approach:

1. Worry-free performance – Corteva cross-spectrum herbicides are proven to perform across Western Canada, providing effective control of the toughest grass and broadleaf weeds in wheat and barley.

2. Convenient packaging - Designed with compatibility and convenient packaging top of mind, all-in-one cross-spectrum herbicides save wheat and barley growers valuable time during the busy spray season.

3. Ease-of-use – In addition to combatting problem grass and broadleaf weeds, the all-in-one solution keeps it simple for the spray crew, allowing for quicker refills and reducing the potential for error.

4. Flexibility – Wheat and barley growers who use Corteva cross-spectrum products have the flexibility to customize with their preferred phenoxy partner (MCPA or 2,4-D).

Corteva cross-spectrum herbicides leave no box unchecked. For more convenience and flexibility with overall improved weed control performance, talk to your local crop protection representative today and make the best weed control decision for your wheat and barley.

Grass AND Broadleaf Weed Control in One Product

Rexade™ herbicide is the complete wheat herbicide. A unique all-in-one solution delivering pure performance through convenient grass and broadleaf weed control.

Rezuvant™ XL herbicide with Arylex™ active combines leading Group 1 grass weed control with outstanding broadleaf technology in wheat and barley.

Tridem™ herbicide delivers powerful broadleaf weed control combined with Group 2 grass chemistry in wheat.

explains Todd.

“You can think of effector proteins as almost the first wave of the things that are being sent out by the pathogen to try and manipulate the host so that the pathogen can be successful.” That’s why identifying clubroot effector proteins and analyzing their functions could be very useful in understanding clubroot infection in canola.

The three researchers are currently pursuing several approaches to increase knowledge of clubroot effector proteins and how they interact with canola proteins. Although there is a lot to be learned along the way, the research results could be a springboard for improvements in clubroot resistance in canola.

PREDICTING EFFECTOR PROTEINS

In 2021, the three USask researchers completed a fiveyear study looking at the proteins expressed and secreted by the clubroot pathogen. “The idea was to look at genes that the pathogen would be expressing. Then based on their gene sequences, we tried to predict which of those genes might be encoding a potential effector protein,” explains Todd.

That predictive genomics work identified many such potential, or ‘candidate’, effector proteins that might be important in clubroot infection. He adds, “You can think about it as almost like a shotgun blast in that there will be dozens or hundreds of proteins being secreted by the pathogen.”

“Then the really hard work began, looking at each of those proteins on an individual basis and trying to characterize what they do and what processes in the plant they interfere with. There is no real script for that; it might be different for every single effector protein,” he notes.

According to the study’s summary report, the project team identified and partially characterized 32 candidate effector proteins from Arabidopsis and 52 from canola. They also started on the formidable task of more fully characterizing the functions of the identified proteins in order to find ones that are important in clubroot infection.

In fact, this study was one of the first to characterize clubroot effector proteins, their roles in clubroot infection and their targets in the host plant.

Their work to fully characterize the many effector proteins identified through this study is ongoing. Post-doctoral researcher Musharaf Hossain and PhD student Cresilda Alinapon are working on characterizing a number of these proteins. “We’re really getting at the basic biology of how the pathogen is interacting with the host,” Todd says.

“Effector proteins are small proteins that are made and secreted by a pathogen.

A PROTEOMICS ANGLE ON EFFECTOR PROTEINS

Todd is currently co-leading a project that is investigating clubroot effector proteins from a different angle. “In our earlier five-year study, we were identifying the pathogen’s genes and predicting the potential effectors. In this current project, we are going into the host cells and pulling out proteins and seeing which proteins from the pathogen are actually there,” he explains.

“So, it is a complementary way to address the same question. Hopefully, we’ll identify some different players including perhaps some non-traditional effectors that we might not have identified in that previous screen based on gene sequences.”

The current project uses a proteomics approach, studying the proteins produced by the clubroot pathogen and by the host plant as they interact. Todd, Wei and Bonham-Smith are collaborating with Allyson MacLean at the University of Ottawa, who is the project’s co-principal investigator, and Kris Kalinger, a postdoctoral researcher in the MacLean lab. “Allyson has been successful in taking this approach in other systems to identify interacting partners between plants and either their pathogens or their symbiotic organisms,” notes Todd.

He outlines the methods involved. “We produce an enzyme in the plant that tags proteins locally. Then we use that tag to pull the proteins out and send them for identification using mass spectrometry. We can direct these enzymes to specific parts of the cells or specific cells in the plant root, with the idea of looking at what pathogen proteins we can pull out at different times and in different places.”

Their activities to identify effector proteins secreted by the pathogen and plant proteins expressed in response to the pathogen include looking at the differences in the expressed canola proteins between clubroot-susceptible and clubroot-resistant canola lines.

So far, it looks like using this complementary approach in their effector protein research is indeed useful. “Using this approach, we have found some of the effector proteins that we predicted to be there using our earlier genomics approach,” he notes. So, the proteomics approach is validating the predictive genomics approach, and vice versa.

“We have also found some novel plant pathogen proteins in the plant cells that we might not have predicted to have been secreted. And that is helpful because it validates taking another look at this question using a slightly different angle.”

A TOOL TO FIGURE OUT GENE FUNCTION

Todd is also leading a project to develop a tool to quickly assess the function of canola genes that have been identified as interacting with clubroot effector proteins.This tool involves virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), a technique that can be used to silence genes in plants. It makes use of a natural defence system in plant cells for silencing viruses, and it turns that

system into a way to silence targeted plant genes in the host plant. In crop research, such methods usually involve inoculating a plant with the gene-silencing construct by applying the construct to the plant’s leaves. However, Todd and his research group previously developed a procedure to introduce gene-silencing constructs through a plant’s roots, and they will be using that procedure in this project.

Todd outlines the VIGS tool’s concept in simple terms. “We get the plant to generate a virus and that virus will spread throughout the roots. A small piece of the host plant’s DNA is integrated into the virus, so the plant recognizes [not only the virus but also that piece of plant DNA] as foreign. Then, as the plant is trying to silence the virus, it will actually silence its own gene.”

This tool would allow the researchers to see what happens in the canola plant when the targeted gene is turned off, enabling them to determine that protein’s role in the clubroot infection process. The idea is to use this tool to evaluate the many canola proteins that interact with clubroot effector proteins to find the ones that, when silenced, will cause changes in the plant

that either hamper clubroot development or that make the plant more susceptible to the disease. The team could then study more closely those canola proteins with a high potential for disrupting the clubroot infection process. Down the road, the researchers would like to use this VIGS tool to determine the role of different clubroot proteins in clubroot infection.

TOWARDS MULTIPLE MODES OF DEFENCE

These studies are helping Todd and his collaborators to learn more about how the clubroot pathogen interacts with canola plants. “And we’re using that to look at the pathways and processes in the host plant that might be important in clubroot infection, whether the pathogen is turning something on or off,” says Todd. The resulting knowledge has the potential to be useful in identifying which canola genes to target in more traditional breeding efforts and in gene editing approaches to creating clubroot-resistant canola varieties.

“In the long term, we’re looking for as many different angles as possible for protecting canola from clubroot,” he notes. “The ideal would be to stack multiple, independent, unrelated sources of resistance together so it becomes increasingly difficult for the pathogen to adapt.”

The proteomics project was funded under the Canola Agronomic Research Program (CARP), with funds from the Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF) and Canola Council of Canada/SaskOilseeds. The gene-silencing tool project was funded by WGRF and SaskOilseeds.

UNCERTAIN ABOUT WHICH NOZZLES WORK BEST FOR PULSE WIDTH MODULATION CONTROL SYSTEMS?

Genetic testing for herbicide resistance

Measuring is the first step for managing herbicide resistance.

BY BRUCE BARKER

If you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it. That’s a well-known business adage that certainly fits for managing herbicide resistance. What should growers do if they suspect herbicide-resistant weeds in a field? One of the first actions is to confirm the resistance so that they can implement appropriate weed control strategies.

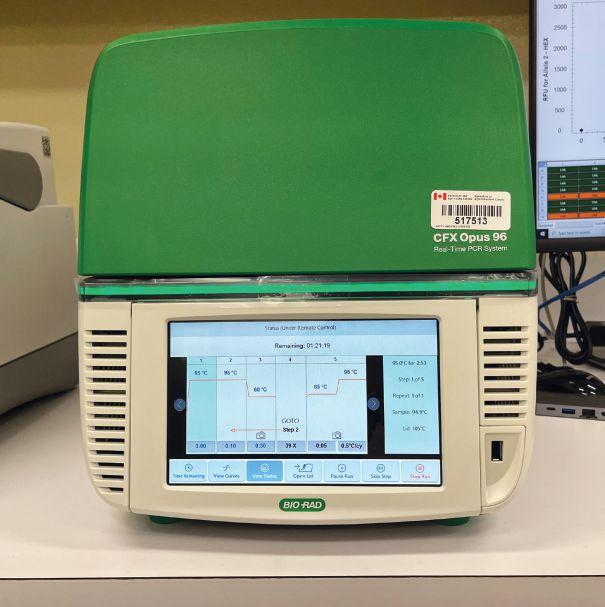

Weed scientist, Charles Geddes with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), is part of a group at the Prairie Resistance Research Lab at Lethbridge, Alta. who are developing new genetic tests that can provide in-season confirmation of herbicide resistance.

“The big benefit of genetic testing is that it only takes one to two weeks to get the results after collecting a leaf sample, so it offers growers the opportunity to take action in the same growing season,” says Geddes.

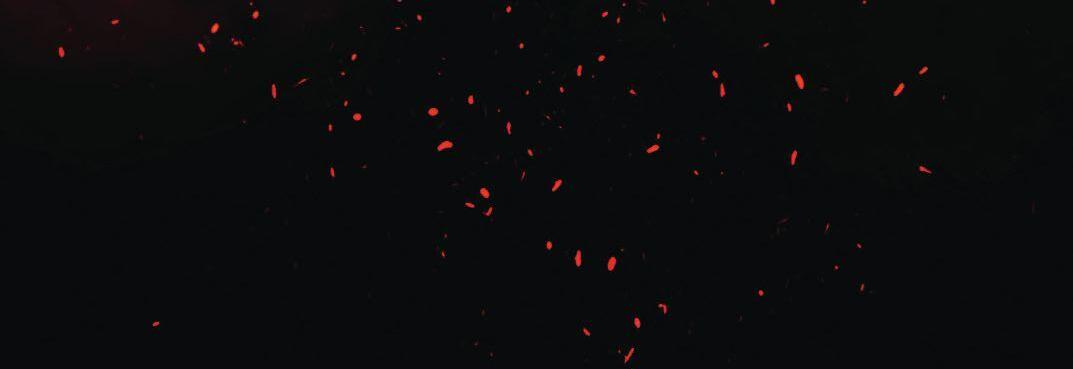

The traditional method of confirming herbicide resistance uses a whole plant bioassay. A grower or agronomist would collect about 2,000 mature seeds at

ABOVE A plant bioassay herbicide-resistant test.

harvest from 10 to 20 plants that have survived herbicide application. The seeds are air dried and then shipped to the lab of choice. There, the seeds are planted into pots or trays in a greenhouse and sprayed with the herbicide suspected of having resistance. The results can provide a general grouping of whether the weed is susceptible or has low, moderate or high levels of resistance, and also a resistance incidence – the percentage of plants having the resistant trait.

Whole plant bioassays can detect herbicide resistance for the two main groups of mechanisms of herbicide resistance – target-site resistance and non-targetsite resistance. Non-target-site resistance is based on a weed’s ability to prevent the active ingredient from reaching its enzyme target site either through reduced absorption, reduced translocation or enhanced metabolism. For example, a metabolic non-target-site resistance is like a hot dog eating contest. Some of us can only eat a couple hot dogs in five minutes, but the rare

All photos courtesy of Charles Geddes.

individual can down 15 hot dogs. That rare weed that can chow down the active ingredient quickly has metabolic herbicide resistance. Whole plant bioassays remain the standard for non-target-site resistance testing.

Each herbicide has a target site that the active ingredient binds to in order to control the weed. Target site resistance occurs when a mutation changes the target site so the active ingredient can no longer bind to the site. It can also occur when the gene encoding the target site is duplicated, thereby increasing the number of target sites and the amount of herbicide required for adequate control. Target site resistance can be identified with both genetic testing or a whole plant bioassay.

Geddes says the genetic tests that they are developing were adapted from work done by molecular biologist Martin Laforest with AAFC at Saint-Jean-surRichelieu, Que. He started working on genetic testing for herbicide resistance in 2015 for weeds of interest in eastern Canada.

The western AAFC lab now has 14 different genetic tests for herbicide resistance. These include Group 1 resistance in foxtail barley, green foxtail and yellow foxtail; Group 2 resistance in chickweed, cleavers,

“The big benefit of genetic testing is that it only takes one to two weeks to get the results after collecting a leaf sample.”

kochia, Japanese brome, narrow-leaf hawksbeard, pale smartweed, redroot pigweed, Russian thistle and stinkweed; and Group 9 resistance in downy brome and kochia.

Notably, an efficient genetic test for wild oat resistance is yet to come. “Wild oat has multiple target-site mutations that confer resistance, but also metabolic resistance. Developing a genetic test for wild oat resistance is a big challenge,” says Geddes.

In 2024, Geddes says their research focused on validating the genetic tests they have developed so far. They have screened about 300 plants for various modes of action. “Overall, the validation went quite well. Our funding runs up to the end of March [2025], and we have a research proposal in to extend the funding for another four years,” says Geddes.

The procedure for genetic sampling is quite straightforward. A weed species that is suspected of having resistance is sampled by collecting leaf tissue from live weeds, ideally from at least five different places in a field. The samples are placed in individual plastic bags that contain beads to help preserve the tissue and shipped to a lab.

24_014610_Top_Crop_Western_MAR1_CN Mod: December 27, 2024 2:01 PM Print: 01/06/25 page 1 v2.5

The results of genetic testing are expressed as known

resistance mechanism detected or not detected. The advantage is, with a turnaround of one to two weeks, the results can inform additional in-season weed control. This compares to a whole plant bioassay that takes four to six months and informs herbicide decisions the following year. The disadvantage of genetic testing is, currently, it only works on target-site mechanisms, and the mechanism of resistance must be known.

While the whole-plant bioassay doesn’t provide immediate herbicide resistance results, it has several advantages over genetic testing. The mechanism of resistance does not need to be known, and it works for both target and non-target mechanisms of resistance.

The end goal of the AAFC Lethbridge lab’s genetic testing research is to license it out to other diagnostic labs. The ultimate goal is to develop genetic testing for each type of target site mechanism of resistance for each resistant weed biotype in the region.

ZEROING IN ON RESISTANCE

Geddes says resistant testing offers farmers the ability to know which herbicides remain effective in their field. Different target site mutations or other resistance mechanisms are associated with different patterns of cross resistance to the herbicides within each mode of action (Group). For example, there are several different mutations that confer Group 1 resistance in wild oat, and this means you can have wild oat with resistance to different combinations of the FOPs, DIMs or DENs (the different chemical subfamilies within Group 1).

“Thus, Group 1-resistant wild oat does not necessarily mean that all Group 1s no longer work on the population. Some of them may still work depending on the resistance mechanism. Without testing, a farmer would not have the information on which of these herbicides might still work on their population,” says Geddes. “In addition, some species, like wild oat, are highly selfing. This means that there can be clear differences between wild oat populations in a relatively small geography – even patches within a field. The type of resistance that one farmer has may be completely different from their neighbour, for example. While I use wild oat as an example here, similar patterns of cross resistance are present in other herbicide groups and species as well.”

Agriculture Canada isn’t the only organization developing genetic testing for herbicide resistance. In eastern Canada, Harvest Genomics Inc. offers genetic testing for 12 different weed species to six different herbicide groups for a fee. In Manitoba, the Pest Surveillance Initiative, a project of the Manitoba Canola Growers Association, offers a genetic glyphosate-resistant kochia test for $125.

Several other labs on the Prairies offer whole plant bioassay herbicide resistance testing. Saskatchewan Agriculture’s Crop Protection Lab in Regina, Sask. offers standardized tests for Group 1, 2 and 8 herbicide-resistant wild oats, and Group 1 and 3 green foxtail resistance. Other herbicide resistance testing is available on request. Tests are available for a fee.

TOP Genetic testing provides diagnostics for in-season management decisions.

Ag-Quest in Minto, Man. also offers whole plant bioassay testing for a fee. Herbicide-resistant testing covers major annual weeds, including wild oats, green foxtail, cleavers, kochia, lamb’s-quarters, redroot pigweed, shepherd’s-purse, smartweed, stinkweed and wild mustard, with most post-emergent herbicides and some soil-applied herbicides. New tests are being developed as the need arises.

At the Prairie Resistance Research Lab at Lethbridge, whole plant bioassay tests are only being conducted for systematic surveys of the region or on novel herbicide resistance cases where resistance has not been previously confirmed. This lab conducts the research behind novel cases of resistance to serve as a mechanism for discovering new issues early and generating the knowledge required to manage them and for other labs to routinely test for them.

Overall, genetic testing and whole plant bioassays have their own advantages and disadvantages. What works best on each farm depends on each farm’s end goal in managing herbicide resistance. And the first step is to measure, so that it can be managed.

Waterhemp: Learning from Ontario’s experience

Waterhemp can cause over 90 per cent yield loss in corn and soybean.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Be afraid. Be very afraid. Waterhemp has wreaked havoc in Ontario and the U.S. corn belt. With the noxious weed now found in 27 Manitoba municipalities, Manitoba farmers and agronomists would be wise to heed the experiences from Ontario.

“You need to have an appreciation of how competitive and invasive this weed species is,” says Peter Sikkema, a University of Guelph weed scientist (retired), who has spent many years investigating ways to control waterhemp.

Waterhemp is a dioecious, summer annual and has separate male and female plants. It has large genetic variability allowing it to adapt to wide environmental conditions and has the propensity to evolve resistance to multiple herbicide groups. It can produce 300,000 seeds per plant when it emerges at the same time as soybean, but that drops to around 3,000 seeds if it emerges 50 days after soybean emergence in Ontario. Seed longevity can be up to 20 years, but most seeds germinate or degrade in less than five years.

Waterhemp thrives in warmer temperatures and moderate to moist environments. It likes high light intensity (think wide row corn and soybeans) and nitrogen-rich soils. Waterhemp can grow up to one inch (2.5 cm) per day and reach over 11 feet (3.5 m) in height.

The spread of waterhemp is likely due to a few sources such as combines, tillage equipment, flooding and migratory birds that could possibly move the seed up to 3,000 km.

Based on research in Ontario, yield loss in corn averages 19 per cent but up to 99 per cent in the most competitive environments. In soybean, average yield loss is 43 per cent but up to 93 per cent.

ABOVE Waterhemp can quickly take over a field.

DEVELOPMENT OF HERBICIDE-RESISTANT WATERHEMP

A major issue for Ontario growers is the development of herbicide-resistant waterhemp. Glyphosate resistance was first identified in 2014 in Lambton County in southwestern Ontario. Waterhemp seed was collected from a field in Lambton County and sprayed with glyphosate (Group 9).

“There was no control when sprayed with glyphosate; we had found the first case of glyphosate-resistant waterhemp in the province,” says Sikkema. Subsequently, Group 2 resistance to Pursuit (imazethapyr) was confirmed. This was followed by Group 5 resistance to atrazine (Aatrex).

For Group 5 resistance, two mechanisms confer resistance: enhanced metabolism and altered target site. This is important, says Sikkema, because enhanced metabolism confers a high level of resistance to atrazine, but Group 5 metribuzin (Sencor) is still effective. However, both atrazine and metribuzin are not effective on

Photo courtesy of Ingrid Kristjanson.

Defend your wheat fields against the toughest grass and broadleaf weeds and declare victory this season. A single pass of BATALIUM® herbicide combines four active ingredients across three modes of action in one simple, co-formulated product. This versatile herbicide also has a wide application window, so it works when and where you need it, across all soil zones. Put an end to yield losses from grass and broadleaf weeds. Contact your UPL retailer today.

waterhemp biotypes with altered target-site resistance.

Group 14-resistant waterhemp to Blazer and Reflex has also been confirmed in Ontario, in addition to Group 27 resistance. “For Group 27, this is an oversimplification. Really interesting, if you have a Group 27-resistant waterhemp plant on your farm, it confers resistance to Group 27 resistance herbicides applied post-emergence (Armezon, Callisto, Laudis, Shieldex] but, amazingly, the Group 27 herbicide applied pre-emergence including Callisto + atrazine, Converge + atrazine and Acuron still work,” says Sikkema.

To make matters even worse, multiple herbicide-resistant waterhemp has developed as well. This includes Group 2 + 9, Group 2 + 14, Group 2 + 9+ 14, Group 2 + 5 + 9 + 14 and Group 2 + 5 + 9 + 14 + 27. “If you have five-way resistance and you are growing corn and soybean in rotation, 80 per cent of our currently registered herbicides are not going to control this population of waterhemp,” says Sikkema.

CONTROL STRATEGIES FOR MULTIPLE HERBICIDE-RESISTANT

WATERHEMP

Sikkema has spent years researching multiple herbicide-resistant waterhemp control. He has looked at pre-emergence only and post-emergence only approaches. While they achieved moderate to good control in many cases, with such high levels of seed production, the level of control needed to be better to minimize weed seed return to the seed bank and to reduce weed management challenges in the future.

In corn, Sikkema found that controlling multiple herbicide-resistant waterhemp required a two-pass weed control program with a soil-applied herbicide followed by a post-emergence herbicide. He found two programs that provided a high level of control approaching 100 per cent.

The first was using a soil-applied Group 27 herbicide

TOP Eradicate waterhemp before it becomes a problem.

BELOW Identify and control waterhemp.

such as Acuron (best control), Converge + atrazine or Callisto + atrazine followed by Liberty post-emergence. The second was soil-applied Integrity (best control) or Primextra followed by a Group 27 post-emergence herbicide such as Acuron, Laudis, Shieldex or Callisto.

“I think Acuron is the best starting point for management of multiple herbicide-resistant waterhemp in corn but weed control can be variable from field to field and year to year, so you need to follow up with a post-emergence herbicide. But if you are an unlucky farmer with Group 27 herbicide resistance, none of those Group 27 post-emergent herbicides will work,” says Sikkema.

Sikkema found a similar two-pass approach worked best in soybean. Soil-applied herbicides Fierce (worked best), Valtera, TriActor, Bifecta or Authority Supreme were followed by one of three programs, depending on the type of soybean. In IP and RR soybean, the post-emergence herbicide options were Reflex, Blazer or Hurricane. In E3 soybean, Enlist 1, Enlist Duo or Liberty can be used to control waterhemp escapes. In ExtendFlex soybean, Engenia, XtendiMax or Liberty were options.

INTEGRATED CONTROL IS KEY

Andrew Kniss, a weed scientist from the University of Wyoming, has made this statement: “At some point we need to stop looking to herbicides as the solution to a problem created by herbicides.” That was the philosophy echoed by many weed scientists and the motivation

Photos courtesy of (top) Tammy Jones; (bottom left) Richard Anderson.

See what happens when you power up your spring burnoff with Aim® EC herbicide. When mixed with glyphosate or used alone with a surfactant, this fast-acting Group 14 herbicide tackles tough weeds like kochia and cleavers, even those resistant to other herbicides. Plus, Aim® EC herbicide offers flexibility—it has multiple tank-mix options and can be used prior to all major crops.

Power Up Your Savings with a $4.00/ACRE REBATE

Get $4 per acre back when you purchase matching acres of Aim® EC herbicide (30 mL/ac rate) or PrecisionPac® CF herbicides1 with Authority® 480 herbicide (43 acre/jug rate), PrecisionPac® SZ herbicide2, Express® brand herbicides3 and/or PrecisionPac® burnoff blends4.

RECOGNIZEGREATNESS

Do you know an influential and innovative woman in Canadian agriculture? We’re looking for six women making a difference in the industry. This includes women in:

• Farm ownership and operations

• Ag advocacy and policy

• Research and education

• Agronomy

• Business development

• … and more!

behind an integrated waterhemp management study that Sikkema ran from 2017 through 2020.

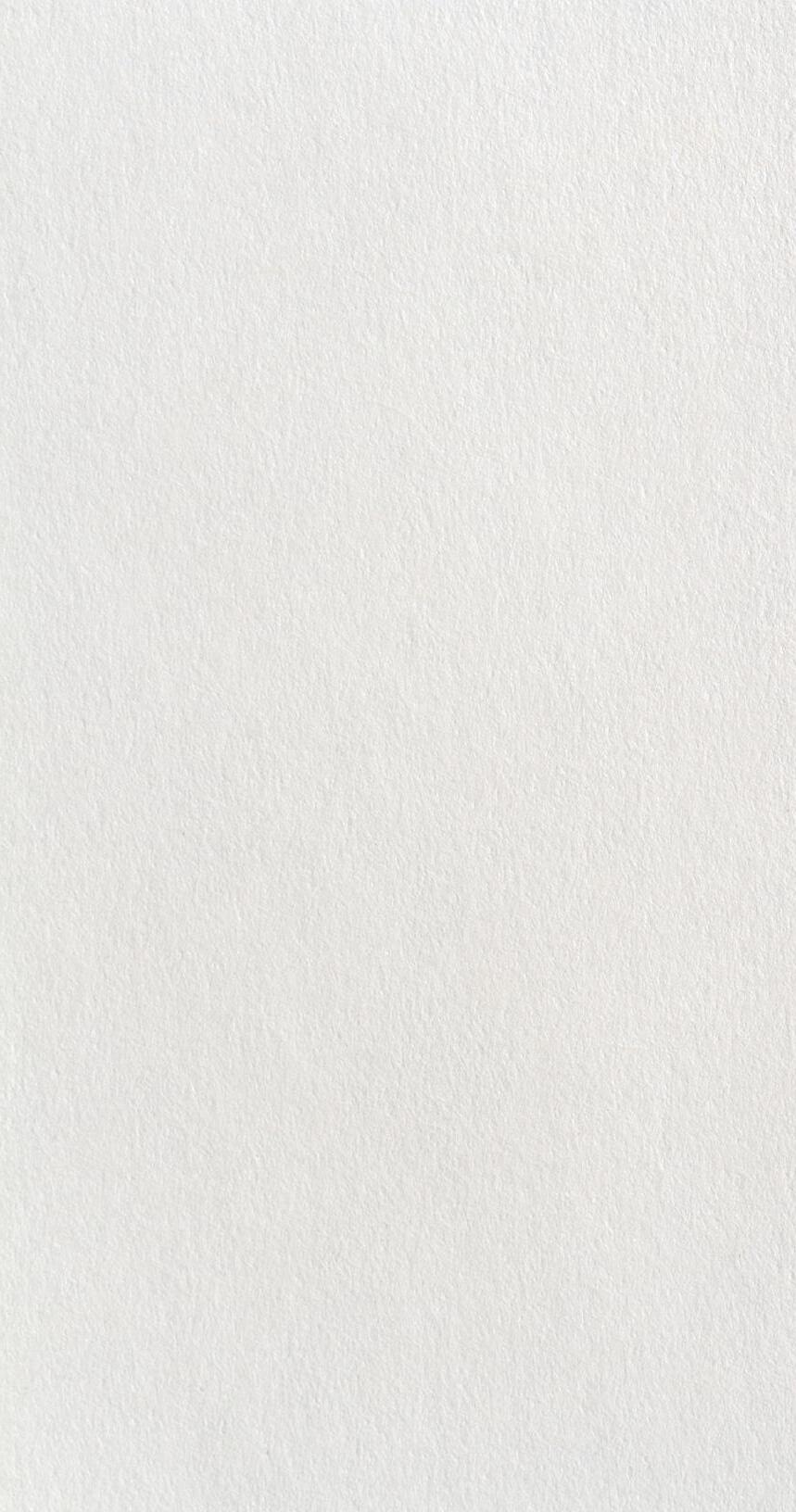

The study’s goal was to deplete the number of waterhemp seeds in the seed bank by using weed management practices that could be implemented on Ontario farms. Two locations on commercial farms were selected with 165 million seeds per acre on the Cottam farm and 16 million seeds per acre at the Walpole Island farm at the start of the trial.

The study looked at five rotations, including a continuous soybean, corn/ soybean, soybean/wheat, corn/soybean/winter wheat and corn/soybean/ winter wheat/cover crop. Two soybean row widths of 37.5 or 75 cm were compared. Sikkema also looked at using multiple modes of action for herbicide control.

After three years, Sikkema looked at waterhemp ground cover on the first of September. Where continuous soybean was grown with only glyphosate applied, ground cover was 79 per cent. For the other rotations, it was negligible.

Looking at waterhemp seed in the seedbank, continuous soybean actually had an increase of 31 per cent. But more diverse rotations with a greater number of modes-of-action had reductions of up to 66 per cent.

The study’s goal was to deplete the number of waterhemp seeds in the seed bank by using weed management practices that could be implemented on Ontario farms.

“This actually worked out better than I thought it would when we initiated that research. I think if Ontario farmers planned their crop and weed management programs, this is a manageable problem on Ontario farms,” says Sikkema.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR THE PRAIRIES?

The first thing that Manitoba farmers should recognize is that waterhemp is classified as a Tier 1 weed under Manitoba’s Noxious Weed Act. Manitoba Agriculture advises that “Tier 1 weeds must be eradicated without conditions. Proper identification is important and control measures will depend on the species. Control of Tier 1 weeds is the landowner’s responsibility (e.g., farmer, company or government, including Manitoba Highways).”

Recognizing that the best defence is a good offence, eradication is the first step in waterhemp control. Manage any plants/patches by not letting them go to seed, and don’t spread the seed by putting them through the combine.

“The point I want to leave you with is that waterhemp is a manageable problem. Farmers need to be aware of it and need to adjust their weed management programs accordingly,” says Sikkema.

In Manitoba, populations of waterhemp have been found that are resistant to several herbicide groups, including combinations of Group 2, 9 and 14.

Looking back and moving ahead on microbial inoculants: Part Two

Biofertilizers for crop nutrition.

BY CAROLYN KING

Editor’s note: To read part one of this article, visit the website at www.topcropmanager.com/looking-back-and-moving-ahead-on-microbial-inoculants/ or refer to the February issue.

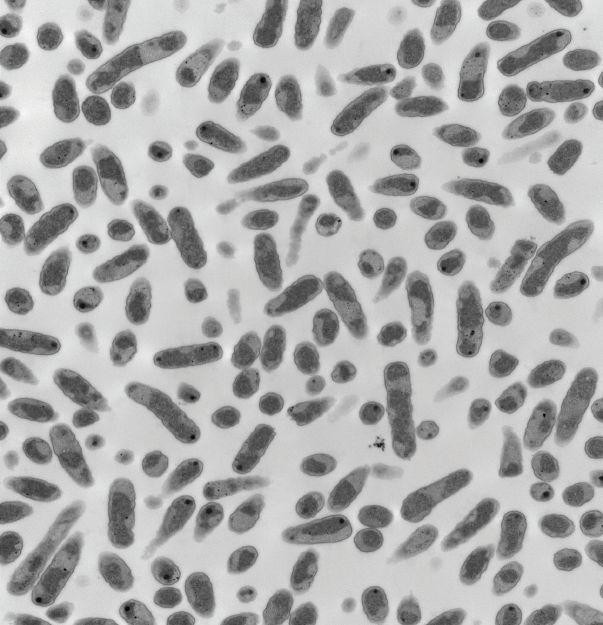

Many studies are currently delving into the complex questions around biofertilizers. One example is a major project that aims to identify and develop inoculant strains by considering the microbes and their microbiomes, the plants and the soil, as well as commercial inoculant production requirements and the economics of inoculant production and use.

“We want to increase the plant’s nutrient-use efficiency through microbial inoculants so crop growers could cut back on the amount of chemical fertilizer they apply and still get the same yield,” says Ivan Oresnik, University of Manitoba microbiologist. He is co-leading this project with George diCenzo, an assistant professor of systems biology at Queen’s University.

The project is primarily targeting inoculants to reduce nitrogen fertilizer inputs. That would help reduce farm input costs, decrease greenhouse gas emissions and improve the sustainability of Canadian cropping systems. At the same time, the researchers are keeping in mind that some microbes can help plants to access other nutrients and tolerate poor growing conditions.

To tackle the project’s broad scope, diCenzo and Oresnik have brought together a team of researchers from six universities: University of Manitoba, Queen’s University, McMaster University, University of Ottawa, University of Toronto–Scarborough and University of Saskatchewan. Genome Canada (with coordination from Genome Prairie and Ontario Genomics) is the project’s primary funder. Co-funders include Manitoba Crop Alliance, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, Western Grains Research Foundation, Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission, Ontario Bean

ABOVE A transmission electron micrograph of cells of a rhizobium that forms nodules on alfalfa.

Growers, Ontario Research Fund, Manitoba Agriculture, University of Manitoba and Queen’s University.

The first step in the project is to collect soil microbes associated with legumes, cereals and brassicas at many locations in several provinces. Then the team will isolate the microbial strains and sequence the DNA to help decide which strains out of the very large initial collection to move to the next step in the process to find the most promising microbes.

This next step involves putting this large subset of strains through two different pipelines at the same time. One pipeline will screen the microbes for their

All photos courtesy of George diCenzo, Queen’s University.

EXPLORE COMPARE OPTIMIZE

ability to provide benefits to plants. The other pipeline will screen the microbes for properties needed in commercial inoculant production.