TOP CROP MANAGER

SWEDE MIDGE

HOST INTERACTIONS

Understanding alternative plant hosts

PG. 6

TACKLING LESSER CLOVER LEAF

WEEVIL

Managing this pest in red clover seed production

PG. 10

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

A new option for wireworm control

PG. 22

Understanding alternative plant hosts

PG. 6

TACKLING LESSER CLOVER LEAF

WEEVIL

Managing this pest in red clover seed production

PG. 10

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

A new option for wireworm control

PG. 22

And gain ground with New 400 and 600 Series Sprayers.

With a redesigned cab and plenty of comfort-enhancing features, the new 400 and 600 Series Sprayers allow you to cover more acres per day in maximum comfort. Reduce overlaps and gain chemical cost savings with the optional ExactApply™ nozzle-control system, which helps you spray with greater accuracy. Plus, these sprayers come loaded with precision ag tools to help you gain ground in your operation.

See what you have to gain at JohnDeere.ca/Ag.

PESTS AND DISEASES

6 | Understanding swede midge host interactions

Alternative plant hosts work for oviposition and larval development. by Donna Fleury

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Lessons learned in a year by Stefanie Croley

AGRONOMY UPDATE

30 Foliar fungicides not recommended for blackleg-resistant canola by Bruce Barker

PESTS AND DISEASES

10 | Tackling the lesser clover leaf weevil Managing this yield-limiting pest in red clover seed production. by Carolyn King

ISSUES AND ENVIRONMENT

14 Protecting bird habitat in agricultural land by Julienne Isaacs

PESTS AND DISEASES

20 Detecting sclerotinia by Mark Halsall

CATCH UP ON THE LATEST EPISODES OF AGANNEX TALKS

PESTS AND DISEASES

22 | Know your enemy Broflanilide may improve wireworm control, but more knowledge of the pest is necessary. by Alex Barnard

PESTS AND DISEASES

26 Where have the weevils gone? by Bruce Barker

A new season of AgAnnex Talks, the podcast produced by the agriculture brands at Annex Business media, launched March 1. Catch up on the latest episodes, with topics like soil health, precision ag technology and more – available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts. AgAnnex.com

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Our April issue is traditionally focused on pests and diseases, and in our April 2020 issue, I wrote about how disease management and prevention is a top-of-mind issue for producers, and one that the ag community has a lot of experience in.

When I first wrote that column in early March, the media was abuzz with talks of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19. Little did we know, last March was just the tip of the iceberg. Here we are a year later still in the midst of the pandemic, and still talking about it. I’m willing to bet it will be a point of conversation for many years to come.

An epidemiologist or plant pathologist I am not, but I see parallels between a disease or virus that affects humans and one that affects plants – namely, the unpredictability. When a new threat emerges, there’s much to be learned about it: how to diagnose it, management, prevention, and the short- and long-term effects. The scientific community works together to find solutions, and for a while it seems there are more questions than answers. Eventually there’s a glimmer of hope at the end of the tunnel in the form of a means of management or prevention. Last spring, we didn’t know a lot about the novel coronavirus, and while we still don’t have all of the answers, we’ve come far in a short period of time.

The same can be said for crop disease management, or even insect pests or troublesome weeds. So much happens behind the scenes, through lab work and fieldwork, to find answers to the unknown – and the work is never done. Over the last several years, we’ve published countless articles on diseases like clubroot and Fusarium head blight, or pests like wireworm and weevils. As threats grow and change, so too do the methods in the lab and field, and with help from the entire industry, more and more solutions and management options become available.

On both the pandemic and agronomy fronts, we’ve learned a lot in the last year, and sometimes there’s so much information that it’s hard to wade through and determine who to listen to. I’ll leave you with a piece of advice that came from Dr. Don Flaten’s presentation at the Top Crop Summit, held virtually in February. Recently retired from the University of Manitoba where he was a professor in soil fertility, crop nutrition and nutrient management, Flaten shared several anecdotes and lessons learned over his 45-year career as a soil scientist, but this one in particular received rounds of virtual applause from the audience: remember the difference between science and non-science and note that nonscience sounds a lot like nonsense.

Best of luck as your season begins.

June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $48.50 Cdn. plus tax Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $48.50 Cdn. plus tax Potatoes in Canada – 1 issue Spring – 1 Year $17.50 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374

This is no time to be sentimental.

Switch to the fastest-growing sclerotinia fungicide.

Canadian canola growers don’t merely expect innovation – they demand it. That’s why more and more are stepping up to Cotegra® fungicide from BASF. Combining the two leading actives that target sclerotinia in a convenient liquid premix, it provides the new standard of protection. So it should come as no surprise that Cotegra is the fastest-growing sclerotinia fungicide. Learn about all the reasons why at agsolutions.ca/cotegra.

see Full Terms and Conditions, visit agsolutions.ca/rewards Earn up to 15% on Cotegra with BASF Ag Rewards.*

Always read and follow label directions.

A wide number of alternative plant hosts seem to be acceptable for oviposition and larval development of swede midge.

by Donna Fleury

Swede midge is a serious crop pest, causing significant damage to canola and other brassicaceous vegetable crops in Eastern Canada. Although swede midge has not yet made its way west to the Prairies, it has the potential if it does to seriously impact canola and other crops like mustard and camelina, as well as weeds species as alternative hosts.

In a four-year study initiated in 2016, researchers at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Saskatoon Research and Development Centre set out to gain a better understanding of the chemical ecology of swede midge and the range of potential hosts on the Prairies. The study examined the host range of swede midge with an emphasis on common brassicaceous weeds found on the prairies and the host plant resistance in these weed species. The

research also investigated the potential biochemical basis of resistance and examined the factors that make plants susceptible to swede midge damage.

“This project was initiated by AAFC researcher Julie Soroka and I took over as project lead when she retired,” explains Boyd Mori, now assistant professor and NSERC Industrial Research Chair in Agricultural Entomology at the University of Alberta. “We were interested in determining if swede midge ever did become established on the Prairies, what plants could potentially be potential hosts, and whether or not any had potential resistance against

ABOVE: A swede midge larva on an infested canola plant, with crumpled leaves that are typical of swede midge damage.

swede midge. We selected 12 different species for the study including crop plants canola, mustard and camelina, as well as several common weed species, such as flixweed, stink weed, ball mustard, pepper grass and others. Since we do not have swede midge on the Prairies, this study was completely lab-based except for weed seeds collected from the field.”

To determine which plants swede midge preferred as hosts, researchers conducted two main experiments using a no-choice and a choice treatment. For the no-choice experiment, swede midge were provided with a single plant to determine if they would accept the plant as a host for oviposition, or egg laying, and larval development. In the choice experiment, swede midge were placed in a cage with the 12 different plant species at the bud growth stage, the stage suitable for oviposition, to determine if they showed a preference for specific plants as a host or not.

“The results from the no-choice experiments showed that swede midge used all of the plants as acceptable hosts for laying eggs and development, except for flixweed,” Mori notes. “In the choice experiments, the swede midge did show some preferences among the different species, with the cultivated crops canola and mustard being more attractive than the weed species. However, among the other alternatives, the swede midge showed a lower preference for camelina, flixweed and pepper grass as hosts when given a choice, indicating possible plant host resistance. The results showed there is a wide variety of alternative hosts that swede midge would use for oviposition and larval development. We also compared how quickly the swede midge developed across the different hosts to see if they might develop more slowly on some than

others. The results were variable, but overall the swede midge developed at a similar rate on most of the potential hosts. We also investigated some biochemicals such as glucosinolates of selected plants as a basis for resistance, however this did not seem to be a factor on whether or not the swede midge would use the plants.”

Researchers also investigated how plants interact with the swede midge, and plant susceptibility factors to swede midge feeding, by monitoring gene expression in a comparative transcriptome study. A moderately susceptible canola line, B. napus (AC Excel), was grown until the six-leaf stage in the greenhouse, then infested with swede midge larvae. RNA was extracted and sequenced from plants at zero, three and 10 days post swede midge infestation, and an analysis of the transcriptomic data and plant hormones performed.

“Although we are still working through the data analyses, the early results show there are several plant genes of interest, some that the swede midge are essentially co-opting from the host,” Mori explains. “We found that when the swede midge is feeding on the plant, there is an upregulation of genes usually associated with plant growth and changes in morphology, as well as genes associated with the breakdown and growth of plant cell walls. These genes may be involved in swede midge gall formation, which can result in severe plant deformation and yield loss. However, some of these genes may also be required by the plant for their own growth, so further investigation of these genes and their involvement in gall formation is warranted to potentially develop resistance to swede midge.”

An important finding from the plant hormone responses analy-

Our recycling program makes it easier for Canadian farmers to be responsible stewards of their land for present and future generations. By taking empty containers (jugs, drums and totes) to nearby collection sites, farmers proudly contribute to a sustainable community and environment. When recycling jugs, every one counts.

Ask ag-retailers for a collection bag, fill it with rinsed, empty jugs and return to a collection site.

sis showed that several plant hormones increased and others decreased with swede midge feeding. Similar to other insect feeding, the plant hormone jasmonic acid was upregulated by swede midge feeding. However, another plant hormone salicylic acid, usually associated more with a response towards pathogens and diseases, was also upregulated by swede midge feeding. “There can be crosstalk between the two hormones and with swede midge it seems to do both,” Mori adds. “This is reflected in the way the swede midge feeds and uses saliva to manipulate the plant, similar to how pathogens interact with the plant. Swede midge doesn’t actually have chewing mouth parts, rather it uses saliva to modify the plant morphology for its own benefit, by causing the plant to grow more and create the gall structure that larvae use for feeding. We are continuing our investigation to look for potential swede midge resistance.”

Although not planned as part of the project, researchers made a very important discovery when they first initiated the project. The midge that were collected from the Prairies to start the lab colony for the research turned out not to be swede midge (Contarinia nasturtii) as assumed, but were identified as the new to science canola flower midge (Contarinia brassicola). “Up until then we assumed we had swede midge because of the galls on canola,” Mori explains. “However, unlike swede midge that are known to be easy to get established in the lab, we kept having failures in getting the colony established. The canola flower midge turns out to need a very specific plant stage in order to lay eggs on, which swede midge don’t. So although these two small midges both use Brassicas and

are within the same genus, they are not actually that closely related and look quite different. For this project we did use swede midge for all of the lab experiments conducted.”

Mori emphasizes the good news for growers in Western Canada is that the canola flower midge in not an issue, unlike swede midge, should it ever get established on the Prairies. The canola flower midge seems to use only one specific stage when the flower buds are forming to lay eggs and so far populations are low. On the other hand, swede midge uses many different plant parts and can have four or five generations a year, building populations quite quickly causing significant crop damage. Research led by Rebecca Hallett at the University of Guelph has also identified a parasitoid associated with swede midge with high parasitism levels in some fields, and is a promising development for biocontrol.

“Although swede midge has not spread west of Ontario to date, it is vital that monitoring continues across the Prairies because of the serious threat it poses to canola production,” Mori says. Swede midge has recently been identified in Minnesota as well. “The Prairie Pest Monitoring Network (PPMN) continues to monitor for swede midge every year with over 40 pheromone traps located across the Prairies. We have not intercepted any swede midge since we started monitoring, which is good news. In my lab at the University of Alberta, we are helping to continue monitoring for swede midge across the Prairies. We are also continuing the gene work from this study with canola flower midge, and depending on funding my also include some projects with swede midge in the future.”

PRE-SEED

Early Take offer ends soon. Purchase by April 30th, 2021 and SAVE up to 15% with Flex+ Rewards*. Find out more at flexrewards.corteva.ca *Minimum 300 acres per category. How you start

Start strong with Corteva Agriscience, the industry leader in pre-seed crop protection. Visit your retailer today to book your Corteva Agriscience products for 2021.

Looking for more options for managing this yield-limiting pest in red clover seed production.

by Carolyn King

Despite its name, there is nothing ‘lesser’ about the challenges in controlling the lesser clover leaf weevil (LCLW) in red clover seed crops. Now a project has assessed potential additional options for managing this tough-to-control pest so growers will be able to rotate their insecticides.

“The lesser clover leaf weevil is far and away the biggest pest and the biggest obstacle to red clover seed production in Saskatchewan. So it is a major pest of an important forage seed crop for growers here,” says Sean Prager, an assistant professor in plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan, who led this project.

“This weevil is from Europe. It was first noticed as an invasive species in Saskatchewan in 1985 because it was causing problems in red clover seed production.” Red clover is the weevil’s preferred host, and the pest is a much greater concern in red clover grown for seed than for forage. Heavy infestations can lead to seed yield losses of over 50 per cent in red clover crops.

Both the adult weevils and the larvae damage the crop. The adults feed on the leaves and leaf buds at night. They overwinter mainly in the fields where they have been feeding. In the spring, they emerge, mate and lay their eggs within the stipules and stems of the red clover plants. The larvae crawl from their hatching site to the plant’s buds and flowers, feeding on the green parts, buds and flowers. Prager says, “When that happens, the flowers will abort, the buds will fall off, and the shoots will lodge.” And of course, seed yields will decline.

He notes, “The weevil has a few natural enemies, but they are not abundant enough to control it [sufficiently to prevent yield losses in seed crops]. So we need some kind of chemical control. Currently, the only active ingredient registered in Saskatchewan for this use is deltamethrin (Decis or Poleci).” This Group 3 insecticide is registered for suppression of the weevil in red clover seed crops.

Prager and his research group are interested in finding alternatives to Decis for several reasons. “One reason is that we’re hoping to identify something that is a little less harsh to bees [because bee pollination is important for high seed yields in red clover],” he explains.

“Another factor is that Decis is a contact foliar spray, but [the weevil adults] are moving around at night and the larvae are inside the stems, so the product is not necessarily going to come into contact with them.

“And third, we really want another insecticide option because relying on a single active ingredient for controlling the weevil

increases the risk that the pest will develop resistance to that active ingredient.”

The three-year project evaluated the effectiveness of three different insecticides in controlling the LCLW in red clover and assessed the impacts of the insecticides on bee abundance. Dan Malamura, who is one of Prager’s master’s students, carried out the work. Project funding came from the Saskatchewan Ministry

PROTECT YOUR HARD WORK ALL THE WAY UP TO HARVEST.

The end of the season is no time to coast – especially when disease threatens to undo all your hard work.

That’s why cereal growers trust the proven protection of Caramba® and Nexicor® fungicides. Developed by fungicide leaders, BASF, Caramba provides superior fusarium management while Nexicor offers enhanced control of leaf disease. Together, they’ll help you take your cereals across the finish line with added confidence. And returns. Visit agsolutions.ca/cerealfungicides to learn more.

Always read and follow label directions.

AgSolutions, CARAMBA, NEXICOR and XEMIUM are

of Agriculture’s Agriculture Development Fund and the Saskatchewan Forage Seed Development Commission (SFSDC).

Prager and Malamura compared Decis with two insecticides that are not currently registered for LCLW in red clover: Exirel (cyantraniliprole, Group 28), and Voliam Xpress (lambda-cyhalothrin, Group 3; and chlorantraniliprole, Group 28).

“We chose Exirel because it is systemic. Systemics, in theory, could have some advantages [over contact insecticides for controlling the LCLW]. For instance, in some cases systemics are less harmful to non-target organisms because they are absorbed into the plant rather than being sprayed as a foliar. Also with a systemic product, ideally you would get an extended period of protection and therefore you wouldn’t have to worry quite so much about the issue of these weevils moving around nocturnally or the larvae being inside the plant,” Prager explains.

“We chose Voliam Xpress because it is a combination of those two modes of action; it has both a systemic and a contact in it. The idea is that you’d have the best of both worlds in a way.”

The field experiments were carried out in 2018 and 2019 in six commercial fields in the Nipawin area. “We were very lucky to have had a whole series of Saskatchewan seed growers who would help us,” Prager notes. “So we were able to find fields suitable for the project each year. We used second-year red clover fields; typically you worry about the weevil in the second year because that is usually when you get flowering and seed.” All six fields had a history of LCLW damage.

At each site, Malamura set up a replicated block trial with multiple replicates to compare four treatments: Decis; Exirel; Voliam Xpress; and an untreated control where water was sprayed instead of an insecticide.

Malamura used a specialized backpack sprayer that allowed him to adjust the spray rate, pressure and so on to simulate a regular commercial spray application. He used water-sensitive spray cards to confirm that he was achieving the desired spray characteristics.

He applied the insecticides based on rates from the manufacturer and used a nominal threshold of six LCLW larvae per 10 clover shoots to decide when to spray. He rarely had to spray a plot twice.

To estimate the impacts of the treatments on bee populations, Malamura in-

stalled two types of pollinator traps – a blue vane trap and a set of three bee bowls – in each plot. He collected the pollinators from these traps several times over the course of the growing season, both before and after spraying. The bees in the traps were identified and counted.

To estimate the efficacy of the treatments for controlling the LCLW, he used two different methods in each plot. One method involved sampling clover shoots in the field and counting the number of living LCLW larvae. That sampling occurred three times: shortly before spraying, 24 hours after spraying, and 12 days after spraying. For the other method, he collected clover stems shortly before spraying and 24 hours after spraying. He put the stems in a growth medium and kept them in a growth chamber for 10 to 12 days, and then counted the living larvae and adults in each sample.

All three products improved yields “Our most important findings relative to the insecticides were that all three insecticides worked pretty well in bringing down the weevil numbers compared to the untreated control, and all three resulted in greater seed yields compared to the untreated control,” Prager says.

“There were some minor differences in the time to become effective [for example, Decis provided better pest suppression in the first 24 hours after application than Exirel]. But ultimately any of them will control your weevils and reduce yield losses due to the weevils.”

Although the threshold they used for spraying did produce yield benefits, the project’s findings indicate that this threshold could possibly be improved. “Our work suggests the actual threshold might be somewhere between four and six larvae per 10 shoots,” Prager says. “There was visible stem and leaf damage on clover plants at densities below four LCLW larvae per 10 shoots, but it seems red clover can compensate for the damage later in the season.”

Another interesting finding was that there was no difference between the untreated and the treated plots in either the types of bees or the number of bees. Prager emphasizes that this result does not mean these insecticides have no impacts on bees.

He explains that various factors could have influenced how many bees were in the traps. “First of all, we were sampling small

plots in a big field so it could simply be that there were lots of bees in those fields and even if the insecticides did kill some, they didn’t kill enough to change what was in the traps. Also, we applied the products based on the label instructions, which means being quite careful to not apply the insecticide when pollinators would be in the field. For example, we applied Decis towards the evening. So it is quite possible that no bees came into contact with this insecticide [while the residues were still hazardous to bees]. It is also possible that the traps were attracting bees from all over the field and that those bees were just going to the traps and maybe not visiting the insecticide-treated plants.”

Overall, they found that bee densities did not limit seed yields in these trials, but a lack of insecticide treatment resulted in significant seed yield losses when weevil pressure was high.

If funding becomes available, Prager and his research group would like to look into several other LCLW control questions.

“The current threshold for spraying

The lesser clover leaf weevil is far and away the biggest pest and the biggest obstacle to red clover seed production in Saskatchewan.

the weevil has not been really well tested, and our work suggests it could probably be optimized. We need to figure out exactly what the threshold and the timing should be,” he says.

“Also, it is important to pin down the rate for Exirel. Exirel is not well tested in red clover; they are working to get a minoruse registration for it now. In our project, we used rates recommended by the manufacturer [based on other weevils in other legume crops]. Since Exirel is about five or six times more expensive than Decis, it is very important to try to find the minimum appropriate rate, how frequently or infrequently to spray, all those sorts of things, to make it a viable option for growers to include in insecticide rotations.”

Prager is also interested in evaluating some other insecticides that might be good rotation alternatives for Decis.

As well, Prager’s research group had been planning to help the SFSDC to partner with a company specializing in automated sprayers, in an LCLW project in 2020. The project was postponed due to COVID-19, but Prager hopes it will go ahead in the future. “We were going to try using the automated sprayers to spray at night. We think it might be more effective to spray overnight when the weevils are moving around and the pollinators are not in the field.”

Such studies could help put more of the pieces in place for improved management of the lesser clover leaf weevil in red clover seed crops.

Powerful broadleaf weed control combined with trusted Group 1 grass chemistry.

• Cross Spectrum Performance

Unparalleled control of a wide range of broadleaf weeds, including kochia, narrowleaved hawk’s-beard and wild buckwheat, alongside leading Group 1 grass control of wild oats and green foxtail.

• Rotational Freedom

Control Canada thistle, perennial sow thistle and dandelion with the flexibility to rotate to lentils or chickpeas the following year.

• Easy Tank Mixing

Tank mix with MCPA Ester for expanded Group 4 mode of action control. Learn more at Avenza.Corteva.ca.

Take offer ends soon. Purchase by April 30th, 2021 and SAVE up to 15% with Flex+ Rewards.*

by Julienne Isaacs

Birdsong forms the auditory background to farm life, but without an effort to preserve their habitat in non-cropped areas, some Prairie bird populations will continue to rapidly decline or disappear altogether, according to new research.

“So many birds have been experiencing dramatic population declines in recent years, particularly because of habitat loss,” says Fardausi Akhter, a research scientist in agro-ecosystems with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Akhter is the lead on a comprehensive study of field boundary habitats in agro-ecosystems that looks at how agricultural productivity is boosted by the presence of non-cropped areas such as field boundaries, roadways, shelterbelts and wetlands.

The project, which began in 2017, was initially funded by AAFC and is now funded by Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Agriculture through the Agricultural Development Fund, and is now in its second phase; Akhter hopes it’ll conclude by 2025.

A recent report published by Environment and Climate Change Canada on bird population trends between 1970 and 2016 found that waterfowl and birds of prey have increased by 150 per cent and 110 per cent, respectively, thanks in part to the work of wetland habitat conservation organizations like Ducks Unlimited. But the tale is far more sobering when it comes to grassland species and other bird populations linked to agriculture.

Birds that rely on grassland for wintering and breeding, Akhter

Insights to help position your farm for success

Annex Business Media’s agricultural publications are hosting four free, live webinars with industry experts discussing key topics in farm financial management.

Part 1: Business Risk Management – A fact-based review and analysis

March 25 - 1pm MT/3pm ET

Part 2: Transitioning Your Farm - Opening the door to your transition

April 15 - 1pm MT/3pm ET

Part 3: Using Data in Ag for financial management

May 19 - 1pm MT/3pm ET

Part 4: Utilizing Benchmark Information to Focus Your Farm Operation

June 10 - 1pm MT/3pm ET

SCAN QR CODE with phone camera or visit link below to register today for the series! A reminder email will be sent to you for each webinar.

The pre-seeding season is a great time for cereal growers to re ect on their weed management strategies and make sure they’re heading into the season prepared for whatever weed challenges may arise. Troy Basaraba, Market Development Representative at Bayer, has provided four key focus areas for weed management that both optimize product application and supports overall yield goals.

It is important to have a clear understanding of the application guidelines for your chosen cereal herbicide.

“Growers need to be familiar with all product factors, such as what the recommended application time is, what conditions that product performs well in, and what conditions can impact its ef cacy. This way they can ensure that the product selected is truly the best t for their needs, or if they need to look for alternatives,” says Basaraba.

According to Basaraba, tank-mixing errors likely occur more often than we realize, but understanding label guidelines on cereal herbicides will help mitigate the issue. It is important to understand what registered or supported tank mixes best suit your needs, and how to mix them correctly. It is also vital to understand which pesticides mix well and do not cause weed control antagonism or adverse crop response.

Keeping an eye on eld conditions, weed staging, and weather can help signal when the ideal window for a herbicide application is coming up or when it is best to wait.

Temperature, moisture, and humidity all impact product performance, so these factors must be monitored as the application window approaches to ensure ef cacy of application timing. “If you don’t understand the situation your area is facing, you can’t plan for success and identify your best application window,” says Basaraba. “Generally, all herbicides will work better when targeted on younger and smaller weeds. This not only helps you get better control of weeds but also supports a weed-free critical growth period for your cereal crop to setup better yield production. I think a lot of us would agree that even a poor application done at the right time on young weeds will serve you better than doing a good application when weeds are out of stage.”

Growers should also be aware of weed spectrum differences across their farm. “Some growers assume that one herbicide will work across all their acres, but that’s not always the case” he says. “For example, a Group 1 herbicide won’t work well in a eld where you have identi ed Group 1 resistant wild oats. Spraying one product across all your cereal crops to avoid the extra work required to apply a different herbicide will compromise that eld’s yield and weed control. You need to rst understand each eld’s needs, and then change up groups, modes of action, or other control measures under an integrated pest management strategy if necessary.”

Proper water volumes, appropriate nozzle and droplet size selection, and correct sprayer speed all in uence the achievement of good coverage and are crucial for product ef cacy.

“Whether the product is a contact or systemic herbicide will impact the droplet size a grower wants to use. Generally, contact products need smaller droplets for better coverage, while systemic products can rely more on coarser, less drift prone droplets,” says Basaraba.

[Credit:

Basaraba generally advises falling within the 250–400 micron level for droplet size for in-crop contact and systemic herbicides (medium to coarse droplet size). Fine droplet sizes (generally below 200 microns) can provide great coverage but come with a huge risk of wind drift. On the other end, very coarse droplet sizes (generally above 400 microns) can lead to declines in product performance due to not obtaining suf cient coverage.

“By adopting a droplet size between 250–400 microns and spraying at a reasonable speed with suitable water volume, growers can set themselves up for success with contact and systemic products,” says Basaraba. “This setup can also potentially compensate for other imperfect factors in your application process, such as weather conditions.”

Adopting more ef cient spraying practices is also important for avoiding the most common herbicide application mistake: rushing the process. Rather than driving faster down a eld to speed up the application, Basaraba recommends increasing sprayer capacity and/or minimizing load times. “If a grower sets up a tender delivery system to reduce load times, they’ll save more time than going 5 miles per hour faster down the eld. It will also help to facilitate better coverage and herbicide performance and allow an operator to do a more diligent spray job.”

While it is tempting to seed as much as you can in a day, this can set you up for a time crunch later in the season. Consider staggering your seeding to lower acreages per day if weather allows. Doing so means that you won’t be forced to rush through your in-crop herbicide applications, since your elds will have different maturities and will not all be hitting their spray window simultaneously.

For more information about Bayer’s cereal herbicide lineup and application practices, visit GetBackToWhatYouLove.ca or speak to your local Bayer rep.

says, have decreased by up to a whopping 87 per cent. “Our grassland birds are under huge threat now,” she says. “Even other species that can tolerate agricultural landscapes have declined by 39 per cent. That speaks to the importance of leaving some habitat for birds before we lose them entirely.”

The plight of a few Prairie species, she says, deserves highlighting. In Saskatchewan and Alberta, Sage grouse is endangered

and McCown’s longspur is threatened. In Manitoba, the grassland species Sprague’s Pipit is threatened and Baird sparrow are listed as endangered; the reason for their population decline is habitat loss. Burrowing owl, Red-headed woodpecker and Chestnut-collared longspur are all either endangered or threatened.

Akhter’s team and other research groups in Canada and around the world are still

Akhter is the lead on another project looking at intercropping annual crops with high-value hazelnut and berry shrubs (such as haskap, buffaloberry and sea buckthorn), which can perform a range of ecosystem services and provide a value-added processing benefit to producers. Such a system could best be adapted for marginal lands, increasing income on a per-acre basis for producers, she says. It could also increase habitat for many species, including grassland birds.

attempting to come up with specific best management practices for bird conservation, but a rule of thumb is to try to preserve non-cropped areas totaling roughly 10 per cent of a farming operation for habitat.

In the study’s first phase, Akhter’s team did bird surveying in person. Bill Bristol, an avian biologist, walked each of the study’s fields early in the morning twice a year between May and June. Two 350-metre walking transects were used at 50 metres and 350 metres from the field boundary to record any bird they saw or heard. One problem with this approach is the fact that some birds naturally fall silent when humans are near.

In the second phase, autonomous recording devices will be placed in the field instead, says Akhter. Software has advanced to the extent that individual bird sounds can be captured and identified. Using available software, the team will validate the results from the first phase of the study and hopefully fine-tune their results.

The study’s initial results, however, are closely aligned with researchers’ expectations. Natural vegetation increased bird abundance and diversity compared with shelterbelts and open fields, Akhter says.

“What we found was that natural vegetation sites near native hedgerows and road allowances had on average four times more birds than open field sites,” she says. Shelterbelts had on average two-and-a-half more birds than open field sites; this is perhaps due to the fact that shelterbelts tend to be limited to a few species and are sometimes heavily groomed below tree-level to mitigate the risk of weed seeds entering the seedbank.

Some birds listed as being of special con-

cern for conservation efforts by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and COSEWIC (The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada), such as the Grasshopper sparrow, were actually spotted in the field, Akhter says. But one threatened species, the Barn swallow, was only spotted four times in three years, always in hedgerows.

The importance of natural vegetation for habitat cannot be overstated for birds on the Prairies.

Akhter says she often thinks of a story told by Benjamin Franklin, considered by some to be the United States’ first environmentalist, in a 1749 letter. Writing about blackbirds, Franklin said the bird had been considered a pest of corn in New England. A bounty was set up for the blackbird, until the species was finally eliminated in the region. Only after was it discovered the blackbird was keeping a worm pest of corn in check, and without its natural predator, the worm increased to the extent that the farmers wanted to re-introduce the blackbird.

“Sometimes we’re too shortsighted to comment on the benefits and costs of certain species. We probably only see one factor,” Akhter says.

Birds perform a large number of services for agriculture. They feed on a wide range of insect crop pests; by reducing the number of adults in the field, birds also reduce the number of eggs laid on leaves, and thus insect larvae, which are also damaging to crops.

Beyond habitat loss, part of what’s threatening bird species is a reduction in insect species due to insecticides. Insectivores feed their young with what they catch in the field. The upshot, Akhter says, is that producers need to be aware of when – and how much – they are spraying in the spring to try to mitigate impacts on bird populations.

Nuthatches and woodpeckers feed on tent caterpillars, to name one example; the former species are declining while the latter is increasing, and Akhter says that without natural controls insects like tent caterpillars can “multiply enormously,” perpetuating a cycle of reliance on synthetic controls.

“It’s not sustainable. I’m not going to say that we should not spray pesticides and insecticides at all, but we need a balance and proper management practices so that we can keep our croplands more eco-friendly,” Akhter says. “We need to keep watching when we’re applying pesticides or insecti-

cides and we should not apply at a time when insects and birds and beneficials are most active because by killing the insects and pests we’re killing the beneficials too.”

Producers can act at a baseline level, she says, by leaving any remaining natural areas untouched, and ideally by converting marginal areas to permanent or semipermanent cover, planting and maintaining shelterbelts, and conserving wetlands. These will be useful not just in maintaining bird populations, but other wildlife species as well.

Akhter admits researchers still need more data on the economic import of bird conservation. This data is being collected, she says, but in general there is a knowledge gap for birds, while pollinators and bees have gained more attention.

“I think it’s important that our producers learn about the impact their farming operations can have on birds that are important in an area,” Akhter says. “If we do not act right now to save some habitat for them, they are not going to survive.”

No matter how challenging your needs, BKT is always with you, offering a wide range of tires tailored to every need in agriculture: from work in the open field to the orchards and vineyards, from high power tractors to trailers for transport.

Reliable and safe, sturdy and durable, capable of combining traction and reduced soil compaction, comfort and high performance.

BKT: always with you, to get the most out of your agricultural equipment.

Researchers in Alberta are relying on nanotechnology to come up with a new solution for warding off Sclerotinia stem rot, one of the most destructive diseases of canola.

by Mark Halsall

Anew tool on the horizon for fighting Sclerotinia stem rot in canola is continuing to show promise.

InnoTech Alberta, a subsidiary of Alberta Innovates and the province’s largest research and innovation agency, is currently looking for a commercialization partner for the tool which utilizes nanotechnology to detect Sclerotinia spores that threaten canola crops.

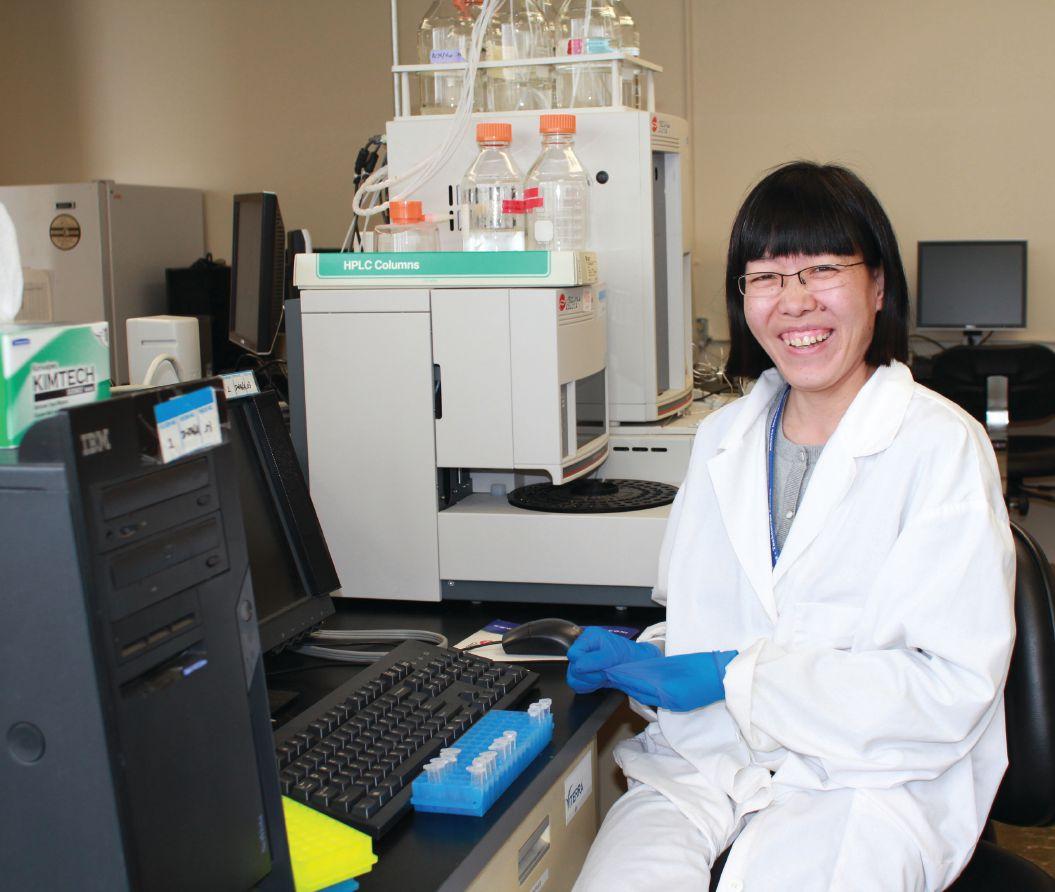

It was developed by Susie Li, an InnoTech Alberta researcher who believed there had to be a better way to help western Canadian producers deal with one of the most damaging diseases of canola.

Li’s solution is a futuristic device that relies on tiny nano-biosensors to detect minute traces of Sclerotinia and can alert growers on their smartphones when spore levels reach a point where they should spray for the disease.

Li says current control methods, which involve predictive instruments such as checklists and risk assessments that inform farmers when conditions are favourable for Sclerotinia stem rot

development, are imprecise and can be unreliable due to unpredictable weather conditions.

“This device works in real time in the field and it’s more accurate,” Li says. “If there are no spores present, whatever the condition is in the field, you won’t have the disease and there’s no need to spray.”

Li maintains the device eliminates the need for canola producers to scout their fields for signs of Sclerotinia stem rot, and that by speeding up and simplifying Sclerotinia detection, it helps growers make quicker disease control decisions.

“Right now, if you want to find out if Sclerotinia is there or not, you need to go into the field, collect tissue samples and then send them to the lab,” she says. “It usually takes at least a week to get your results back, and by then it’s probably already too late to spray.”

Li says there have been a number of hurdles to overcome since the project started five years ago.

One was coming up with a system for collecting and counting Sclerotinia spores, which Li says was accomplished by developing antibodies specific to Sclerotinia and incorporating them in the biosensors.

“The sensor chip is coated with these specific antibodies, so it will recognize Sclerotinia spores only,” Li says.

The next step was improving the sensitivity and lowering the detection limit of the biosensors to make them more precise. Li says this was achieved new microfluid technology that enables fluids to be processed at an extremely small scale.

“When we started this project, we had to have around 1,000 spores to cause the signal to change to a level that was detectable,” Li says. “We solved that problem by using the micro fluid technology. Now we can detect a single spore going to the chip and sensitivity is no longer an issue.”

A delivery process then had to be developed for relying the biosensor readings to devices like a computer tablet or a smartphone, so that remote users know when Sclerotinia spore levels have reached a point where they’re a problem.

This was accomplished with the help of researchers at the University of Alberta, who designed a signal transmission system for the biosensors using Bluetooth technology. Li says the U of A researchers are currently devising a new system that enables the signals to be sent via Wi-Fi.

The first working prototype of Li’s Sclerotinia detection system

had its initial in-field test last summer at InnoTech Alberta’s experimental farm in Vegreville, Alta. The testing revealed a design flaw in the biosensors, which Li and her team are currently addressing.

“The air samples we took were dirty and blocked the very thin tube that goes form the sample reservoir to the biosensor chip,” Li says. “We need to add a really tiny screen that can screen out whatever material we don’t want to go through the tubing.”

Li hopes to have a fix ready for another test of the prototype this summer, but she points out progress has been constrained by the pandemic.

“We are moving forward, but really slowly at the moment” she says.

Li says one of the objectives of the testing is to determine how many nano-biosensors are required on a per-field basis for the system to operate effectively.

Li and her team are also investigating ways to make the system less expensive so that it’s more attractive as a cost-effective solution for farmers. She says while the cost for one biosensor is currently around $30, a search is underway for a manufacturer that could possibly bring the price down to $10 per biosensor.

A new, early-warning system like this for warding off Sclerotinia stem rot is obviously something that would benefit canola producers on the prairies right now, but Li anticipates it’ll be a few years yet before a commercial version is ready to be unveiled.

“I’ve gone to several agronomic conferences and had people come up to me say, ‘Whenever this is ready, I would like to have it to test my crop,’” she says. “So, yes, I’d say the growers are really excited about it.”

Broflanilide is set to provide improved wireworm control, but a greater understanding of the pest is still necessary.

by Alex Barnard

Wireworms are a particularly pesky pest on the Prairies. While there are chemical control options that prevent wireworms from feeding on a crop or paralyze them, there hasn’t been a pesticide capable of killing them since the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) cancelled registration of lindane in late 2004.

With the PMRA’s registration in November 2020 of broflanilide, the first Group 30 insecticide on the market, that’s set to change.

“What’s been missing for a number of years in crop protection is a registered pesticide that will kill wireworms,” says Haley Catton, research scientist and entomologist with Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “In recent years, the ones that have been registered in cereals, pulses and even potatoes have been effective at protecting crops through paralyzing the wireworms or repelling them – pushing them away in the soil. But they haven’t been reducing wireworm populations enough to provide multi-year control.

“So that means those same wireworms, because they live for multiple years, are there in your soil just waiting for next year’s crop. That would mean a producer would require consistent applications every year, even while the wireworm populations build up and build up because there’s nothing killing them.”

Applying pesticide for use in this manner isn’t uncommon, but it is costly, especially if the return on that investment is small. But Catton notes that, through conversations with colleagues who have yet unpublished research on broflanilide’s effects, it has huge potential for within season and multi-year wireworm control.

“There’s only one published study on broflanilide and wireworms so far, because it’s a pretty new chemical. That study described field trials in B.C. and showed that [broflanilide] protected wheat stand similarly to other chemicals, but also reduced wireworm populations, which was unique among the registered chemicals tested,” she explains. The current market formulation of the other recent new formulation registered for wireworm, a diamide, was not included in that study. “So, if a chemical can reduce your wireworm populations, that means maybe you don’t need to apply it next year as well – you’re knocking back the number of wireworms.”

While it’s early days yet, broflanilide shows promise as a replacement for lindane.

“The published study showed that [broflanilide] was killing 70 per cent of the wireworms in the treated plots. That was a seed treatment on wheat, but 70 per cent is a really nice knock-back

Adult and larval stages of the main pest wireworm species on the Prairies. From left to right: Hypnoidus bicolor (no common name), Selatosomus aeripennis destructor (Prairie grain wireworm), and Aeolus mellillus (flat wireworm).

number, and that’s very similar to what we would see with lindane back when it was still registered,” Catton says.

“What’s really interesting about broflanilide too, is that – at least in cereals – you could apply it as a seed treatment and it has enough residual to kill the new hatchlings that would hatch from eggs several months after seeding. By seed-treating in the spring, you’ve killed last year’s wireworms, but you’re also killing this year’s because new hatchlings are going to be killed by the chemical, too.”

A serious problem in wireworm control is the lack of research and information on the pest.

“There are multiple species [of wireworm] in on the Prairies: hundreds of non-pest species, and four or five main pest species,” Catton says. “[However] there are no surveys done at all for wireworms. The damage is really hard to pin on [them].

“We don’t really have a good way of monitoring wireworms

When it comes to controlling broadleaf weeds,

are always up to the challenge. With three powerful herbicide Groups, In nity® FX herbicide is the best way to take out over 27 different broadleaf weeds, including kochia and cleavers. Use In nity FX to manage resistance and get back to farming.

new species – those tools weren’t available before.”

Catton and her colleagues have created a new wireworm field guide for the Prairies, which will be available later this year. She notes that the complexity of wireworms as a pest means more research is necessary. While some fields may be devastated by wireworms, other growers might not have ever experienced any damage and believe the threat wireworms pose is overblown.

“In terms of the research, it needs to keep going because [wireworm is] a patchy pest that’s made up of multiple species,” she says. “That makes it very different from a pest like wheat midge or wheat stem sawfly or something that’s just one species. We’re talking about multiple species with different life cycles, different behaviours, different feeding behaviours; some of them need to mate, some of them don’t.”

“There’s no black and white with wireworms, unfortunately,” Catton says. “The whole thing is complex.”

On the topic of pesticides more broadly, Catton hopes to shift perceptions of when to use them.

“One way to think about chemicals is insurance,” she says. “You could say, ‘I’m not sure what’s going to happen, so I will invest in this treatment to prevent it from happening.’ But there are hidden costs with that: not only the cost of the chemical in the application, but also any of the non-target effects to beneficial insects that might be controlling some other pests you have in your field.”

“An insurance salesperson might say, ‘Better safe than sorry,’ but as entomologists we’re trying to shift that perception: yes, there is something to lose by applying when you don’t need to.”

reliably and we also don’t have economic thresholds. Keep in mind we’re talking about multiple different species with different behaviours, so it’s a very complicated problem to try to solve,” she adds.

“The only really reliable control we have for crop protection are chemicals at the moment, but we’re hoping as research goes forward to have new tools available.”

Catton notes that there is a great deal of research and work being done on wireworms in Canada at the moment. Pending funding, she plans to work on a project on wireworm thresholds on the Prairies this

spring. She was also part of a team analyzing the pheromones produced by females of certain species of the beetle stage of wireworms, which attract male beetles for mating.

“One thing people have done for European wireworm species is synthesize those pheromones so we can put them in traps and have a bunch of beetles come to those traps – so you can easily monitor what species are around and how many,” Catton explains. “There’s been major advancements in that on the Prairies; I’m part of a team where we isolated new pheromones for two

Catton likens entomological research on pest insects to laparoscopic surgery. “I think a more historic mentality would have been, ‘Let’s sterilize this field, let’s kill everything in that field.’ But we know from research how important those other insects in the agro-ecosystem are. They eat weed seeds, they eat pests – they eat and they poop, so they’re cycling nutrients,” she says.

“We want to be surgical – how can we get in there and reduce the populations of the ones we don’t want, and leave everything else we do want. That’s the future for insect pest control.”

Just GO. Choose solutions with Arylex™ active for performance and application flexibility, whether you’re dealing with small or large weeds, in early or late crop staging and even in cool or dry conditions. Visit your retailer today to purchase your Corteva Agriscience products for 2021! Early Take offer ends soon. Purchase by April 30th, 2021 and SAVE up to 15% with Flex+ Rewards*. Find out more at flexrewards.corteva.ca *Minimum 300 acres per category.

Cold winter weather is good for something.

by Bruce Barker

Pea leaf weevil and cabbage seedpod weevil were missing in action in 2019 and 2020 on some parts of the Prairies. One reason was likely cold winter weather. Does that bode well for 2021?

“In our modelling, winter soil temperatures seem to have a tight relationship with overwinter survival, and cold temperatures can drive the populations down,” says James Tansey, provincial insect/pest management specialist with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture in Regina. Both weevils overwinter as adults and their survival depends on how cold it gets under litter and debris in treed areas, ditches, field margins, and perennial legume crops. Winters with low snow cover and a deep freeze can result in the death of adult weevils.

Super-cooling temperature is a measure of cold hardiness. This is the temperature at which ice crystals form inside an organism. The super -cooling temperature of an insect can be lower than the 0 C freezing point of water. Through various mechanisms involving alcohols or antifreeze proteins, the insect’s freezing point can be lowered.

For cabbage seedpod weevil, research by Hector Cárcamo with

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada found that the super-cooling temperature is -7 C. He also found that its survival over eight weeks decreased significantly at -5 C relative to 5 C.

Asha Wijerathna, a graduate student of the Cárcamo and Maya Evenden labs at the University of Alberta has also established the supercooling temperature for pea leaf weevil at -12 C.

Tansey says that the lack of snow and cold winter temperatures of 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 likely contributed to a decline in both weevil populations in Saskatchewan during the 2019 and 2020 growing seasons. He uses Environment Canada weather station data, and models the daily mean, minimum and maximum daily temperatures under the snow in January and February, based on a model developed by Katri Rankinen at the Finnish Environment Institute in Helsinki, Finland.

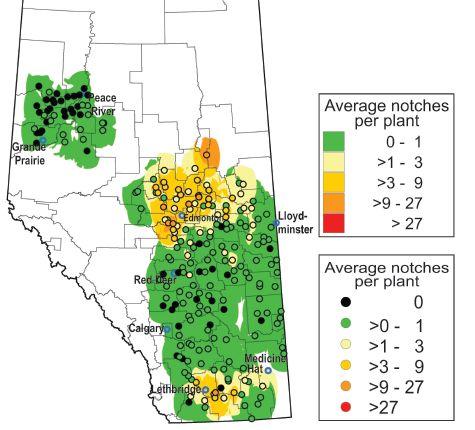

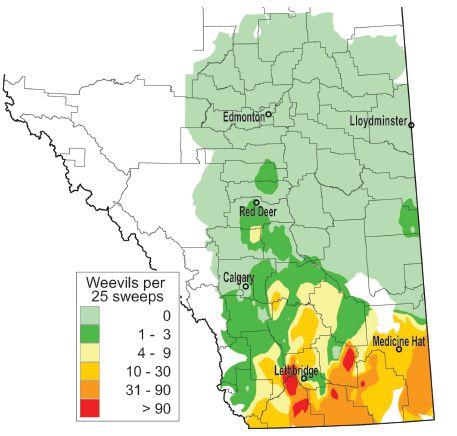

TOP: Cabbage seedpod weevil and pea leaf weevil populations have declined in some areas.

INSET: Bronzed blossom pollen beetle (Brassicogethes viridescens) are an insect of concern for Eastern Canada.

“We use modeling to estimate the temperature under the snow because soil temperature isn’t broadly measured by Environment Canada. We have had good success in correlating the modeled temperatures with overwinter survival of the weevils,” Tansey says.

The pea leaf weevil first showed up in southern Alberta in 1997, and Saskatchewan in 2007. It had been moving east and north in both provinces, and as recently as 2017 there were some fairly heavy infestations across southern Alberta and southern Saskatchewan as well as central Alberta. But in 2019 and 2020, pea leaf weevil populations had dropped dramatically. In Alberta, areas around Edmonton and Lethbridge still had relatively high numbers, but the rest of the province saw a decline in populations.

southern part of the two provinces, the numbers are lower but with typical hot spots in southern Alberta around Lethbridge. In Saskatchewan, Tansey says the 2020 survey map has not been completed, but that a preliminary look at the data shows that the population seems to be diminishing in much of the province, but with a few heavier infestations in southwest Saskatchewan.

Looking forward to the 2021 growing season, Tansey isn’t sure how the February 2021 cold snap will affect the populations. With some snow on the ground insulating the weevils, the populations may not have hit their super-cooling temperatures.

“There may have been some insulating value from the snow, so we’ll have to see how the populations fared this winter,” Tansey says.

For pea and faba bean growers concerned with pea leaf weevil, the most effective control option is the use of an insecticidal seed treatment for pea and faba bean seed.

Canola growers should scout for the cabbage seedpod weevil as the canola crop begins to flower. The action threshold for applying insecticides is 25 to 40 weevils in 10 sweeps during canola flowering, varying depending on canola price and cost of control. Insecticide application targets adults when crops are in 10 to 20 per cent flower (when 70 per cent of plants have at least three to 10 open flowers) to avoid eggs being laid in newly formed pods.

Tansey says agronomists and growers should keep an eye out for a couple new insect pest threats. The spotted winged Drosophila is a fruit fly that was widespread in Saskatchewan in 2019, and low levels were found in southern Manitoba in 2020. The fly attacks many fruit crops and can be quite damaging.

“In 2020, we didn’t have see an occurrence of the fly in Saskatchewan, so we are watching to see if it is endemic here, or if it is introduced on contaminated fruit from other areas,” says Tansey.

Cabbage seedpod weevil followed a similar trend. This insect pest has typically been a major problem in southern Alberta, and had spread into much of southern Saskatchewan. However, surveys in 2018 and 2019 show that while the distribution is still widespread across the

The other insect pests of concern are the pollen beetles (Brassicogethes aeneus and B. viridescens), which attack canola and oilseed mustard. They are not known to be established in Western Canada, but are present in Nova Scotia, PEI and Quebec. Adult females lay clusters of two to three eggs in developing buds and can lay up to 250 eggs in one summer. Once the eggs hatch, larva enter developing flower buds to feed. This feeding can reduce seed production by up to 70 per cent.

Most people seek help when they need it.

shouldn’t be any different

It’s time to start changing the way we talk about farmers and farming. To recognize that just like anyone else, sometimes we might need a little help dealing with issues like stress, anxiety, and depression. That’s why the Do More Agriculture Foundation is here, ready to provide access to mental health resources like counselling, training and education, tailored specifically to the needs of Canadian farmers and their families.

BRUCE BARKER, P.AG CANADIANAGRONOMIST.CA

With increased blackleg (Leptosphaeria maculans) incidence and shorter crop rotations in many parts of the Canadian Prairies, there was a growing interest in foliar fungicide treatment to reduced disease risk and impact on yield. This interest was also fuelled by a shift in blackleg races, which meant that the original resistant cultivars were no longer as effective in minimizing the impact of blackleg.

With funding from the Canola Agronomic Research Program, research led by Gary Peng at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada investigated the impact of foliar fungicides on blackleg disease incidence, severity and yield at early versus late application, and one versus two applications at different growth stages on the susceptible canola cultivar, Westar. This was to represent the worst-case scenario of cultivar resistance erosion.

The research was carried out at Vegreville, Alta., Melfort and Scott, Sask., and Carman and Brandon, Man. The plots at each trial site were seeded adjacent to a previous field of the blackleg susceptible Westar. Four fungicide products were selected for in-season application: pyraclostrobin (Headline), azoxystrobin (Quadris), propiconazole (Tilt), and azoxystrobin + propiconazole (Quilt).

Each fungicide was applied at the two to four leaf stage of Westar to target early infection of cotyledons and the lower true leaves of canola. To compare efficacy between early and late treatments, Headline was also applied at early bolting. Two-fungicide treatments were also sequentially applied to Westar; Headline or Tilt at the two to four leaf stage, followed by Tilt (to Headlinetreated plots) or Headline (to Tilt-treated plots) at early bolting, to compare with the early treatments.

Headline was also applied to the resistant cultivars 43E01 (MR) and 45H29 (R) at the two- to four-leaf stage to assess the impact of cultivar resistance on fungicide efficacy. These resistant cultivars both carry the specific R genes Rlm1/LepR3 and Rlm3.

Disease severity was assessed at growth stage 5.3 to 5.4, when canola seed in the lower pods started turning from mottled greenbrown to brown. Mean Disease Severity (MDI) and Disease Severity Index (DSI) ratings were used for the assessment.

Blackleg levels varied substantially on nontreated Westar with MDI ranging from 28 per cent to 96 per cent (average 67.9 per cent) and DSI from eight per cent to 69 per cent (average 31.8 per cent).

Applying Headline, Quadris or Quilt at the two- to four-leaf

stage, or Headline and Tilt (or vice versa) at the two- to four-leaf and early bolting stages to Westar reduced the disease incidence and severity significantly compared to the nontreated control. However, the two-application treatments applied at the two to four leaf and bolting stages was no better than the early application of Headline alone.

On the moderately resistant cultivar, 43E01, the disease incidence was high at 65 per cent with moderate severity at 32.9 per cent on the untreated control. The application of Headline reduced the incidence to 48.6 per cent and severity to 19 per cent, respectively.

For the resistant cultivar 45H29, the disease incidence was still fairly high at 53.9 per cent but severity lower at 21.2 per cent. The application of Headline significantly reduced the incidence to 42.3 per cent and severity to 13.7 per cent.

The treatments that reduced MDI and DSI on Westar also limited the yield loss caused by blackleg in a range of 16.5 to 26.9 per cent, relative to the untreated control. Untreated Westar yielded 26 bu/ac (1,441 kg/ha), while the treatments that reduced blackleg showed higher yield in the 31 to 33 bu/ac (1,720 to 1,829 kg/ha) range.

On the moderately resistant and resistant cultivars, however, even though the application of Headline at the two- to four-leaf stage reduced MDI and DSI significantly, there was no yield benefit.

The results of the research clearly show that in-season fungicide treatment will provide little benefit when disease pressure is low (MDI <30 per cent) in Western Canada, especially on resistant canola cultivars.

Growers and agronomists are encouraged to scout for blackleg at swathing to assess if a cultivar is starting to show higher blackleg incidence and severity – a sign that the blackleg race may have shifted in the field. They can also submit samples to several labs in western Canada to determine the blackleg race present in the field. This information can help guide cultivar selection based on resistant gene labeling of cultivars. The Canola Council of Canada has a list of labs that conduct blackleg race identification at blackleg.ca.

However, growers shouldn’t just rely on cultivar resistance to manage blackleg. For every resistant gene available to plant breeders, there is a virulent race that can overcome it on the Prairies. Other management practices such as extending crop rotations, the use of Certified seed, and controlling Brassica weeds and volunteer canola are additional ways to reduced the amount of blackleg inoculum in the field.

Bruce Barker divides his time between CanadianAgronomist.ca and as Western Field Editor for Top Crop Manager. CanadianAgronomist.ca translates research into agronomic knowledge that agronomists and farmers can use to grow better crops. Read the full Research Insight at CanadianAgronomist.ca.

When you’ve

three modes of action (Groups 2, 6 and 27), taking on 32 of the toughest weeds is easy. Velocity m3 herbicide is an all-inone product that gives you effective resistance management against Group 1-resistant wild oats and foxtail, and Group 2- and Group 9-resistant broadleaf weeds. Do

We’ve worked with farmers to simplify their spray decision by offering cross-spectrum herbicides that control both grass and broadleaf weeds in their cereal crops. Cross-spectrum herbicides from Corteva Agriscience deliver more convenience, flexibility and overall improved weed control performance.

Early Take offer ends soon. Purchase by April 30th, 2021 and SAVE up to 15% with Flex+ Rewards*.