STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Herbicide-resistant weeds. Invasive insects. Creative production strategies. Crop inputs and timing. So many important elements to a successful crop; so little time. And yet, each year, these factors become more and more significant, with additional strategies and considerations cropping up to keep you on your toes. It reminds me a bit of parenthood: just when you think you’ve overcome a particularly challenging phase, a new development arises to throw you off again.

But despite how helpful it would be to see into the future and predict what challenges (related to crop production, parenting, or otherwise) may arise in the days and weeks to come, imagine how boring it would be to know exactly what to expect at any given time. It would certainly change the way we do things, but we’d lose all of the lessons learned in the process – and on top of that, we’d have a hard time coming up with the agenda for our annual Top Crop Summit.

The Summit took on a different format this year, but if you attended our first virtual event, you’ll know how valuable the presentations and conversations were. And if you missed it, you’re in luck. This special digital edition contains summaries from each presentation, with some important graphs and charts highlighted. At the end of each article, we’ve linked the presentation recordings so you can register and watch them. And, as a bonus, some of the conversations with Albert Tenuta and Robyne Bowness Davidson were featured in a recent episode of Inputs, the podcast by Top Crop Manager, which you can listen to here.

We hope you enjoy reading some of the insights our esteemed speakers provided at the Summit, and we look forward to hosting you again next year.

@TopCropMag /topcropmanager

Alex

Bruce

Quinton

Michelle

ON THE COVER:

Glyphosate-resistant wild oat is an ongoing weed concern for producers, and was a hot topic at the 2021 Top Crop Summit.

PHOTO BY BRUCE BARKER.

Exploring the impact of Bt-resistant corn rootworm populations and steps to mitigate risks.

Presented by Tracey Baute, with information from Jocelyn Smith, at the 2021 Top Crop Summit.

Bt-resistant corn rootworm is having an impact on Ontario corn. Tracey Baute, field crop entomologist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, discussed the impacts of Bt-resistant corn rootworm populations, and the necessary steps to take to mitigate the risks at the Top Crop Summit, held virtually on Feb. 23 and 24, 2021.

The western corn rootworm and northern corn rootworm can cause significant damage when larvae feed on corn roots during June and July. Research has found that for each node pruned, yield loss can be 15 to 18 per cent. Silage corn losses can be higher because of lodged plants left behind during harvest.

Bt-rootworm hybrids have become the foundation of corn rootworm management, but when corn is grown in continuous rotations, rootworm populations build up in the field. Within these populations are ones with resistance to a Bt-protein, and these can survive and multiply to overcome Bt-rootworm corn hybrids.

The development of Bt-resistance has been documented in the United States over the last two decades. Single traits were marketed first, and then combined in pyramid hybrids where two different Bt-resistant proteins were placed in one hybrid. Solely relying on pyramid hybrids (repeated use) for rootworm management with rotation of these pyramids as the only resistance strategy resulted in cross resistance to multiple Bt-rootworm proteins, and a breakdown in protection.

Four Bt-rootworm proteins are registered in Canada. Three of the four are closely related, and resistance to one protein will result in resistance to the other two. Field failures in Ontario have been observed with three of the four proteins, indicating cross-resistance.

Bt-RW Hybrids Registered in Canada

Agrisure® 3122 mCry3A + Cry34/35Ab1

Agrisure Duracade® 5122 mCry3A + eCry3.1Ab

Agrisure Duracade® 5222 mCry3A + eCry3.1Ab

Optimum® AcreMax® XTreme Cry34/35Ab1 + mCry3A

Qrome Cry34/35Ab1 + mCry3A

SmartStax® Cry3Bb1 + Cry34/35Ab1

SmartStax® Enlist Cry3Bb1 + Cry34/35Ab1

SmartStax® Refuge Advanced Cry3Bb1 + Cry34/35Ab1

One or both proteins may be compromised. At best, some may have only one working protein (single trait hybrid). No new traits coming!

In areas with Bt-resistance, these resistant corn rootworm populations persist in fields. As a result, rotation out of corn for two years will be the main strategy to knock the populations down to lower, less damaging levels. Growers are strongly discourage from planting corn with a different Bt-rootworm pyramid hybrids in 2021, as pyramids are now largely single trait hybrids at best in these failure areas.

For livestock producers who rely on corn for feed and silage, OMAFRA forage and livestock specialists have worked to find the best non-corn feed and silage options. For silage replacement, this includes double cropping of winter cereal and spring seeded

No-to-low risk in first-year corn

Low-to-moderate risk in second-year corn

Moderate-to-high risk in third-year corn

sorghum-sudangrass, while others like Italian or westerwold ryegrass have potential, too. Various cereals can be considered for high moisture corn feed replacement though consultation with livestock nutritionists are advised.

Another option is to grow non-Bt rootworm hybrids; Bt hybrids that only contain above ground Bt proteins for European corn borer or western bean cutworm. Protection against corn rootworm would be achieved with in-furrow application of granular or liquid insecticides. A high-rate neonicotinoid seed treatment could also be used (though require pest assessment reports for use in Ontario) for root protection.

Biocontrol with nematodes has potential as production labs scale up supply over the next several years. The nematodes have shown success in the U.S., and a few Ontario growers have already used them. The nematodes can persist for more than 10 years after one application, and can help drive Bt-resistant rootworm populations down to enable the use of Bt- rootworm hybrids again.

In the long term, sustainable practices to restore the durability of Bt-rootworm hybrids will require a combination of rotating out of corn once every four years, using Bt-rootworm hybrids only in high risk years, and rotation of all rootworm management tools in the other lower risk years.

As part of a long-term strategy, corn growers are encouraged to scout for signs of resistance, such as high adult beetle activity, and goosenecking and lodging of corn plants. If growers think they

For more Bt-resistant rootworm information Field Crop News (fieldcropnews.com) Canadian Corn Pest Coalition (cornpest.ca) Manage Resistance Now (manageresistancenow.ca) Long-Term

Year 1 - Non-Rootworm Bt Hybrid (above-ground Bt traits only). Scout for rootworm beetle activity in August to determine if root protection is needed for Year 2.

Year 2 - Non-Rootworm Bt Hybrid (above-ground Bt traits only) plus additional root protection tools (ie. soil-applied insecticide seed treatment) if Year 1 corn reaches adult threshold in August.

Year 3 - Pyramid Bt Rootworm Hybrid (soil insecticides and high-rate neonicotinoid seed treatment not recommended). Scout and report any unexpected root injury.

Year 4 - Plant a non-corn crop to remove rootworm population. Effectively manage any volunteer corn in these fields to ensure proper rotation from host.

have a failure, they should notify their seed supplier and provincial entomologist.

Contact Tracey Baute or Jocelyn Smith if you are interested in learning more about the biocontrol nematodes.

TRACEY BAUTE

Entomologist – Field Crops OMAFRA – Ridgetown 519-360-7817

tracey.baute@ontario.ca

@TraceyBaute

DR. JOCELYN SMITH

Research Scientist

Field Crop Pest Management U of Guelph, Ridgetown Campus 519-674-1500 Ext. 63551 jocelyn.smith@uoguelph.ca @JocelynLSmith

Watch the entire presentation from the

Feb 23-24, 2021

Learning and re-learning the principles and practices of soil fertility.

Presented by Don Flaten at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Don Flaten recently retired from the University of Manitoba after spending 45 years learning and working in agronomy and soil fertility. He completed a B.Sc.Ag (agronomy) from the University of Saskatchewan in the 1970s and a PhD from the University of Manitoba (U of M) in the 1980s. Prior to teaching and conducting research on soil fertility on a full-time basis at the University of Manitoba (19992020), Don was director of the School of Agriculture at the University of Manitoba (1987-1999), provincial soils specialist for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture (1984-1987), and a district agriculturist for Alberta Agriculture (1978-1980).

At this year’s Top Crop Summit, Don reflected on the soil fertility lessons he learned – and some that he forgot – along that education and career path.

Some of the biggest changes to agriculture in the Prairies over those years have been the move to zero-till seeding and the rise of one-pass seeding and fertilizing practices. At the same time, there were large declines in summerfallow acreage, especially in Saskatchewan. This meant increased cropped acreage and less reliance on mineralization of soil organic matter for nutrients.

Cropping systems also became more diversified with the introduction of canary seed, chickpeas, grain corn, lentils, mustard, soybeans, and sunflowers, along with a massive increase in canola acreage. Crop yields have also increased requiring more nutrients for crop growth, and resulting in more nutrients removed from the land in the harvested crop. The average yield of spring wheat in Manitoba has more than doubled since 1970 from around 22 bushels per acre to almost 50 bushels per acre.

In the 1960s and 1970s, nutrient removal often was greater than the amount of fertilizer applied. That may have been the case back then, but it’s not the case today, at least in Manitoba. Since the mid-1990s, the amount of nitrogen (N) fertilizer applied has generally equalled the amount of N removed by the crop. Phosphorus application and removal have followed a similar trend.

In response to the high yield potential of modern spring wheat varieties, research was conducted by Amy Mangin, research agronomist at the U of M, in 2016 and 2017 to see if the nitrogen fertility levels required for optimum economic returns had changed. At seven site-years in Manitoba, the economic optimum range of soil test plus fertilizer N was 1.9 – 2.9 lbs. N/bu, with an average of 2.3 lbs. N/bu to grow an average of 86 bu/acre. The former recommendation was 2.5 to 3 lbs. N/bu, so the amount of N per bushel is a bit smaller. However, with the higher yield potential, the overall N requirements per acre are much larger with today’s wheat varieties.

Nitrogen placement and timing practices have also evolved. In the 1970s, most N fertilizer was applied as broadcast urea (46-00). Research during that period found that anhydrous ammonia (82-0-0) outperformed urea mainly because ammonia was banded and urea was broadcast.

Research by John Harapiak with Westco looked at the N responses for spring versus fall application and broadcast versus banded application of urea in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Relative to spring broadcast urea, fall banded urea produced wheat yield increases that were 42 per cent higher and spring banded yields were 38 per cent higher. Fall broadcast N response was nine per cent less than spring broadcast.

One of the key benefits of band application of N is reduced immobilization by soil microorganisms. Immobilization ties up a larger portion of fertilizer N during decomposition of crop residues, and maximum immobilization occurs when crop residue and fertilizer are incorporated together into the soil. It’s important to remember that fertilizer additives such as nitrification inhibitors are unlikely to reduce immobilization, but band placement will.

Landscape position also affects nitrogen uptake and efficiency. Excess moisture is a very important factor that contributes to N losses . . . and the risk of excess moisture varies across a variety of time and spatial scales . . . including not only the regional differences across a country or a province, but also at the landscape scale within a field.

Research by U of M graduate student Kevin Tiessen in the early 2000s found that banded urea on low landscape positions in the same field was 20 per cent less efficient than spring banded urea when urea was banded early in the fall. However, on higher,

better drained landscape positions, time of application did not have a significant effect on yield response to N. And urea banded in late fall was equivalent to spring banded urea, regardless of landscape position.

In 1975, banding was generally accepted as a better way to apply phosphorus (P). A quote from Don’s old textbook, Soil Fertility and Fertilizers, third edition, by Tisdale and Nelson (1975), indicated that: “Drilling the P with small grain seed requires only half as much to produce a given increase in yield as when the material is broadcast.”

Westco research in the 1980s found this statement was generally true, but may underestimate the benefits of banding P. Wheat yield was higher with banded than broadcast P fertilizer, and 20 kg/ha phosphate banded was as good as 80 kg/ha broadcast. But the Guide to Farm Practice in Saskatchewan (1987) and a more recent Ag Canada study also indicated that yield response to P fertilizer on the same site is highly variable from year to year, depending on moisture and temperature conditions. Part of the variability is due to crop rotation (e.g., whether the crop was first or second year wheat after fallow), but it’s also due to year-to-year variability in P supply from soil vs. P demand by crop.

P response also varies with crop species. For example, greenhouse studies in the 1960s at the U of M showed that soybeans are more efficient than other crops for feeding on soil P in Manitoba soils. That probably explains why recent field studies by U of M graduate student Gustavo Bardella showed that even on sites with low soil test P, soybeans responded infrequently to fertilizer P. Only one of 28 trials showed a seed yield response to P fertilization. This had not changed, as the 1975 Tisdale and Nelson fertility textbook highlighted similar findings.

Research on corn response to starter fertilizer P has produced some contradictory findings. The 1975 textbook recommendation was to sideband starter P to corn, particularly in northern areas. This was supported by U of M masters student Magda Rogalsky in her research (2015-2016) that found side-banded starter P in corn provided substantial benefits, especially if the corn was planted after canola. Starter P resulted in twice as much early season biomass, up to one week earlier maturity, a decrease of grain moisture content by two to three per cent, and a 10 per cent yield increase. But subsequent research by U of M Masters student Dickson Tran (2017-2019) added another perspective. Dickson looked at the effect of starter P on eight different corn hybrids. Although starter P improved the yields, overall, when averaged across all eight hybrids, only one of the hybrids had a substantial yield response and that was the hybrid that Magda Rogalsky had used in her study.

Traditionally, potassium (K) fertilization looked straightforward. Large K responses occur consistently on sandy soils with low concentrations of exchangeable soil test K, especially on responsive crops like barley.

Megan Bourns, in her U of M Masters research project in 2018 and 2019, looked at K fertilization of soybeans on K deficient soils. Potassium deficiency symptoms were observed throughout the growing season. However, she found no yield response to any K treatment at any site. But barley planted on the same sites showed a 20 per cent increase in yield where soybean showed none. This indicates that the current recommendations based on soil test K work well for barley but not soybean.

Megan

Another trend that Don and others have observed since the 1980s has been the increasing risk of sulphur (S) deficiencies, even on black soils with high soil organic matter. As a result, sulphur fertilization has become standard practice for canola production on almost all types of soils in Western Canada.

From Don’s perspective, climate will continue to challenge us, with increasingly variable weather, from one place to another and from one week, month, or year to the next. Public concerns about environmental issues will continue to grow, resulting in mixed impacts of government policies and consumer pressure on agricultural practices. This means that principles of soil fertility and crop nutrition will continue to apply, and that new agronomic technology should continue to be built on sound agronomic techniques.

As a final thought, what would Old Professor Don advise Young Student Don? First, science can be helpful –learn it and use it. Second, all of us can learn something from someone else. And finally, enjoy not only the journey, but also the wonderful people you’ll meet and work with along the way.

Watch the entire presentation from the

Feb 23-24, 2021

Optimizing crop rotation practices for the best results.

Presented by Steve Larocque at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Steve Larocque, agronomist with Beyond Agronomy in Three Hills, Alta., discussed how crop rotation provides other benefits in addition to crop yields at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

One strategy is to use crop rotation to improve harvestability. Traditionally, wheat is grown on pea stubble but I grow field peas on wheat stubble. Anyone who grows peas knows that picking peas up off the ground is time consuming and has a tremendous additional expense. We harvest wheat stubble taller – eight to 10 to 12 inches tall – and then seed peas just beside the wheat rows the next spring. The peas will eventually trellis up the wheat stubble and remain standing. As a result, harvesting is much easier and faster.

Crop rotation can also be used to build soil fertility. I grow malt barley on pulse stubble, which is another unconventional practice because people are concerned about protein content. But growing malt barley on pulse stubble is not as risky as one would think. The ultimate goal is to keep protein content under 13.5 per cent or less depending on the malting company. What happens is that the malt barley crop uses the extra subsoil moisture left behind by the pulse crop to build yield and not necessarily protein. For example, I’ve grown AC Metcalf barley on faba bean stubble with a 116-bushel yield and an average protein content of 12.2 per cent.

ABOVE: Crop rotation can improve harvestability, build soil fertility and help improve crop emergence.

Rotation can also be used to build fertility. The fertility blend typically applied to a malt barley crop is 80-45-15-5, and that would work out to 276 pounds of product applied per acre. We want to build phosphorus fertility, but don’t want to slow down the seeding operation with extra product. So I cut back nitrogen by 20 pounds, which I can do because malt barley is on pulse stubble, and then increase phosphorus by 20 pounds per acre and another 15 pounds of potassium. The blend is 60-65-25-5 and the total volume applied would be equivalent at 278 pounds per acre. So I’m building phosphorus fertility

through the use of crop rotation.

Rotation can also be used to help improve crop emergence. Tight wheat rotations leave a lot of wheat residue that is high in the C:N ratio at around 90:1. So it takes a lot of nitrogen to break it down, and the residue hangs around a lot longer. You start to build a really thick thatch layer on the soil surface. As a result, I try to leave the wheat stubble tall at harvest, and then balance the crop rotation with peas with a C:N ratio of 15:1, barley at about 45:1 and canola at 30:1. When you use a crop rotation to balance C:N ratios, you don’t end up with fields with big, heavy mats of crop residue that can impede stand establishment.

ABOVE: Crop rotation can balance C:N ratios, which prevents heavy mats of crop residue in fields.

Rotation can also be used to build resiliency. When you look at the weather cycles of too much rain and not enough rain, you can use rotations to build resiliency in your farming operation. Yields can continue to perform by building good subsoil moisture in dryland areas.

I have a soil moisture sensor mounted on my sprayer to map subsoil moisture. Lentil stubble usually has an extra one-and-ahalf to two inches more soil moisture compared to canola stubble at harvest. Canola is a water hog, and so is wheat. So adding a pulse into the rotation helps to build resiliency because you have that extra soil moisture. When you look at the high yields we’ve been getting in central Alberta over the last five years – 90 to 100 bushels per acre of wheat – and sometimes it doesn’t rain for 30 or 40 days after seeding – the yield is coming from stored soil moisture.

All of these strategies bring benefits in addition to the crop rotation benefits of managing weeds, disease and insect pests.

INVESTED IN RESEARCH SINCE 1981

20

550 MORE THAN PROJECTS LISTED AT WGRF.CA $200M

171 CURRENT RESEARCH PROJECTS & ACTIVITIES

INVESTMENT AT MORE THAN DIFFERENT RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS

130 OVER FARMERS HAVE SERVED ON THE WGRF BOARD

A long-term Ontario study breaks down the effects of crop rotation on yield, soil health and environment.

Presented by Dr. Craig Drury at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Research scientist Dr. Craig Drury with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada discussed the results of longterm crop rotation studies in Ontario at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

One of the longest crop rotation studies at the Harrow Research and Development Centre in Ontario was established in 1959. It consisted of continuous corn, with or without fertilizer, compared to corn in rotation with oats and two years of alfalfa, with or without fertilizer. The five-year average yield (2016-2020) for fertilized continuous corn was only 112 bushels per acre whereas the fertilized rotation corn was 68 per cent greater at 188 bushels per acre. In contrast, the yields

for unfertilized continuous corn was not sustainable at only 17 bushels per acre because the nutrients were depleted in the soil.

Another study was set up in 2001 to look at the long-term effects of crop rotations on yield, soil health and environment. Seventeen crop rotations were established including continuous corn, continuous soybean, continuous winter wheat, winter wheat underseeded to red clover as well as various two-, three- and four-year rotations with those crops.

At the start of the study, the soybean yields were all similar, but after two years, continuous soybean yields declined and were always significantly lower than soybeans in rotations. Five-year soybean yield averages (2016-2020) showed that continuous soybean had a yield of about 42 bushels per acre. Moving to a two-year rotation resulted in higher soybean yields, but the highest yielding rotation was with a three-year rotation of soybean-winter wheat-corn with an average yield of about 63 bushels per acre, which was 50 per cent greater than continuous soybean.

A similar yield trend occurred with corn. Continuous corn was yielding only 118 bushels per acre. A corn-soybean rotation raised yields up to around 154 bushels per acre, and the highest yields were with a three-year rotation with winter wheat underseeded to red clover followed by corn and soybean at 169 bushels per acre, which was 43 per cent greater than continuous corn. The red clover cover crop in the winter

wheat increased corn yields by five bushels per acre compared to the winter wheat-corn-soybean rotation.

The research looked at soil health benefits as well. Dr. Ike Agomoh, a postdoctoral fellow working with the soil team at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada compared the effects of long-term crop rotation on many of the soil health indicators. Potentially mineralizable nitrogen (N), was found to be one of the most responsive indicators with over three times higher values for the more diverse crop rotations than continuous soybean. For soybeans, the potentially mineralizable N data followed the same pattern as yields.

The same trend was seen when looking at particulate organic matter carbon with the lowest levels in continuous soybean and almost double the amount in the soybean-winter wheat-corn rotation.

After 17 years of the rotation study, total soil organic carbon was also increasing. Continuous soybean had just under two per cent soil organic carbon while the soybean-winter wheat-corn had just over 2.25 per cent soil organic carbon –an increase of 16 per cent. Although changes in soil organic carbon can take time to be detected, some of the soil health indicators such as potentially mineralizeable N or particulate organic matter responded to changes in soil management practices more quickly.

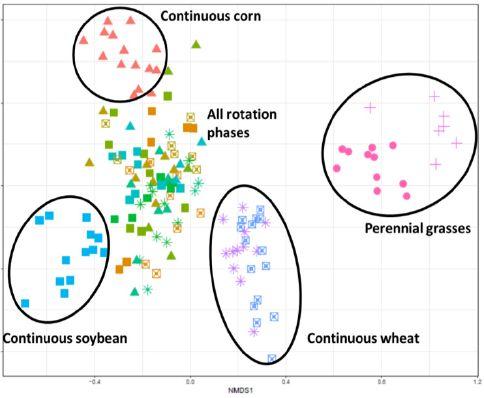

Research was conducted by Dr. Lori Phillips to see how crop rotation alters the soil microbiomes. After 15 years of crop rotations, samples were taken in the spring and fall over several cropping years. Different fungal communities developed in different crops under continuous rotations. Fungal communities in continuous soybean were different than those under continuous wheat or continuous corn, and also different than those under perennial grasses. Some potentially pathogenic fungi, such as Volutella spp., were up to 16 times more abundant in continuous soybean than rotation soybean. However, potentially beneficial fungi such as Fusidium spp., which might be involved in the development of disease suppressive soils also similarly increased. Overall, with two or three crops in rotation, there was a greater diversity of fungal communities in the soil.

Data from our long-term Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada study in Woodslee, Ont., as well as Dr. Bill Dean’s long-term crop rotation study at the University of Guelph, was utilized in the 11 site North America study, which examined the effects of crop rotation diversification on agricultural resilience to adverse growing conditions. The probability of having an increased risk of crop failure was higher for simple crop rotations compared to a more complex crop rotation. When there was an increased opportunity for a bumper crop, complex rotations had a higher chance of producing high yields compared to simple rotations. On average over all growing conditions, corn grain yields were 28 per cent greater with the more diverse rotations compared to simple crop rotations.

All of these studies show the value of long-term crop rotation research on soil health and crop yields.

Presented

Rby Megan Bourns at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

andomize. Replicate. Stats first, agronomic interpretation second. Economics follow. Megan Bourns, On-Farm Network agronomist with the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers (MPSG), discussed how to get the most out of on-farm trials at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

MPSG has been running on-farm trials since 2012 and the On-Farm Network (OFN) was officially created in 2014. To date, more than 350 trials have been conducted, and MPSG continues to co-ordinate them because of the value it provides farmers.

There are many different approaches to investigate various agronomic practices on-farm. These approaches can include splitting fields, running a test strip, doing demo plots, and formal, replicated and randomized trials. Field splits, test strips and demo plots are not useful because they do not provide reliable data. An on-farm trial is research conducted scientifically and statistically soundly by a farmer or his agronomist, with his own equipment, agronomic management and growing season conditions.

The MPSG OFN trials are large field-scale strip trials, but on-farm trials can also take the form of smaller scale plots interspersed in difference management zones using variable rate technology. What it comes down to is that the scale of your onfarm trial or the scale of the question should reflect the scale at which your management decisions are made.

So why is investing time and effort into on-farm trials a valuable thing to do? The very core of the ‘value’ discussion for on-farm research is the fact that it’s conducted under very ‘real’ conditions. On-farm trials investigate the agronomic recommendations or principles coming out of small plot trials, which are conducted under uniform conditions and maybe a different package of management decisions compared to what applies to the farm. On-farm trials allow you to evaluate how they perform in your fields, under your growing season conditions and management decisions. They allow you to make future farm decisions with confidence.

There are several steps for setting up for success. First, identify an appropriate question that is specific and can be answered with two or three treatments. This could be: “Can I reduce my soybean seeding rate without lowering yield?”

Set realistic treatments for your farm that are different enough from each other to potentially lead to different agronomic outcomes. Comparison treatments could be a normal seeding rate versus 30,000 seeds per acre lower rate. Consider including a third treatment as well. i.e. 120,000 vs. 150,000 vs. 180,000 seeds/ac.

Determine the trial location, design and layout. Select an appropriate, representative part of the field, and then randomize and replicate so that statistics can be run with confidence. Replication builds statistical power. Randomization makes sure the difference is really from the treatment

Plan in-season data collection that is relevant to the trial question. If seeding rate is being investigated, collect or at least observe things like early and late season plant stand as well as yield.

Accurate yield results are very important. Before harvest, plan out how the replicates will be harvested, ideally with a weigh wagon or grain cart with a scale.

Statistics tells us if the differences are real or random. They show if the treatment actually made a difference. Statistics should be done first, agronomic interpretation next, and economics to follow.

How to run statistics? The MPSG has resources in the OFN research section that has information on understanding statistics. The Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) has a guide to statistics and a useful statistics spreadsheet that helps to run simple statistics for on-farm research projects.

When a treatment is statistically significant – or different – from another treatment, it means that the difference was due to the treatment and not a random effect. When statistics are presented, there may be letters to indicate significant differences. Letters that are different mean the differences are significant.

After conducting statistics, determine the agronomic and economic impacts of the trial and whether the outcomes favour a management change. Also assess the whole package of information you have from your trial, such as plant stand, nodulation ratings or other observations.

And, when you get a “no result” with no significant differences, that is still a result with agronomic implications.

The MPSG OFN allows you to share results and learn from others who are doing the same on-farm trials. The OFN website organizes single site research reports into a searchable database, providing detailed information at the farm level, packaged in an easy-to-read short document. Use this information to compare how on-farm trials in similar geographic areas turned out.

Following these steps will ensure your trial deserves a Gold Star, and you can make future farm decisions with confidence.

Exploring the history of herbicide resistance in Ontario and recent developments for solutions.

Presented by François Tardif at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Herbicide resistance is evolving in Ontario. François Tardif, professor of plant agriculture at the University of Guelph, discussed how herbicide resistance develops and best practices to manage it at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

Herbicide resistance is a form of adaptation. Herbicide resistance happens at the population level. Individual plants are not changing. Rather, the type of individuals in a population are changing. Herbicide application selects for individual weeds that are resistant to that herbicide. Over years of repeated herbicide application, the weeds that are resistant to the herbicide survive and multiply to become the dominant population.

The first documented resistant weed in Ontario was wild carrot that was resistant to 2,4-D found in 1957. In 1973, lamb’squarters resistant to atrazine herbicide was identified. The first glyphosate-resistant weed, giant ragweed, was confirmed in 2008. In 2017, four-way resistant waterhemp was confirmed. There are now 38 herbicide-resistant weed biotypes, in 21 weed

species and resistance to seven different herbicide groups. Multiple-resistant biotypes have become common.

In Canada, 119 resistant biotypes have been identified in 38 weed species and to 10 different herbicide groups.

The way weeds reproduce has a big impact on how fast multiple resistance develops. While the majority of weeds are self-pollinating, cross-pollinating weeds develop multiple resistance faster. Cross-pollinating populations are more variable and they shuffle genes each generation. This means that crosspollinating weeds like waterhemp develop resistance much faster than self-pollinating weeds.

The challenge for farmers is to find an increasing diversity of weed control methods while addressing the need for soil conservation, time management and profitability. When applying herbicides, the use of effective mixtures with different modes of action is necessary – but make sure you aren’t overrelying on herbicides.

Research by Willemse et al., published in 2021, looked at

herbicide mixtures to control waterhemp that was resistant to Groups 2 + 5 + 9. Several herbicide mixtures were able to achieve greater than 95 per cent control through the use of effective modes of action.

Diversification of cropping systems will also be required to manage herbicide resistance. This diversity may include the use of cover crops, the manipulation of row width and density to improve crop competition, and cultivation for weed control.

Research has found that the use of a rye cover crop can reduce Canada fleabane density. And the rye cover crop was even more effective in reducing Canada fleabane with the introduc-

tion of tillage.

Research also showed that a rye cover crop improved the effectiveness of a herbicide application on Canada fleabane. Four weeks after applying saflufenacil, the combination achieved almost complete control, and was significantly better than herbicide application without a rye cover crop.

In conclusion, the rise of cross-pollinated multiple herbicide resistance will make weed control more difficult. And we can’t count on many new modes of action to be registered to help control herbicide-resistant weeds. Introducing more diverse weed management is the only way out.

Watch the entire presentation from the

There are many unknowns, but being aware of the disease is more important than fearing it.

Presented by Albert Tenuta as an on-demand session for the 2021 Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Tar spot in corn is an emerging disease issue in Ontario. Albert Tenuta, field crop extension plant pathologist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) at Ridgetown, Ont., provided an update on the disease at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

Tar spot has been on the radar in the United States for decades because of its impact on yield loss. The yield losses can be minor, but can average 10 to 50 per cent in grain and silage corn.

Hybrid susceptibility is an important factor in tar spot development. All hybrids are either susceptible or have a partial tolerance.

Another important factor is environment. Favourable conditions for development include temperatures between 17 and 25 C, 75 per cent humidity, and leaf wetness of seven hours.

What has happened in the U.S. is causing a concern in Ontario. There has been an increase in the disease in the U.S. in 2018 and 2019. In the past year the spores have move up into Ontario. The pathogen overwinters in crop residue, so it will be

in southwest Ontario in 2021.

The disease is easy to identify. It produces tar-like spots on the leaves. Rub the leaves and if it feels like sandpaper, it is probably tar spot.

Whether tar spot develops in Ontario in 2021 depends on the disease triangle: a susceptible hybrid, the right environmental conditions, and the presence of the pathogen – which is in Ontario.

Tar spot can develop quite rapidly and symptoms can appear two weeks after infection. The concern is that there can be more than one life cycle in one growing season. If infection happens early in the growing season, the disease can cycle several times resulting in a lot of infected tissue and early senescence. This causes grain yield loss and reduction in silage quality.

The disease was found in five counties in southwest Ontario in September 2020: Wellington, Essex, Lambton, Elgin and Middlesex. In some cases the disease was minor but some fields

ABOVE: Tar spot produces tar-like spots on corn leaves that feel like sandpaper.

had 10 to 15 per cent leaf damage.

The biggest risk for Ontario in the next several years is what happens in the U.S., because the spores can blow in on the wind. A question is whether management practices will have to be adjusted. Field scouting will be important. If growers have been seeing white mould in their beans, that’s the same environmental conditions that favour tar spot.

There is a lack of understanding on hybrid susceptibility. Research is in the works to look at that. Ask your seed company if they have any information on tar spot resistance in their hybrids.

Fungicide application is another question, as well. OMAFRA is part of a Tar Spot Working Group in the U.S. and Ontario. Research is looking at the efficacy of foliar fungicides and application timing. Foliar application with multiple modes of action – two to three – is showing the best control, and also provides a larger window of protection as well.

Fungicide timing is also important. Generally timing targets the tasseling to silking stage. But in 2018 in the U.S., when the disease established early, a vegetative application was warranted. In 2020, the disease didn’t get started until R4 to R5 stages, and at those reproductive stages, there is very little impact from the disease.

Crop rotation may not provide a big advantage because the spores are airborne. Rotation might help to keep the spore load in a field lower.

We are working with the U.S. to develop a predictive model for tar spot development, similar to the white mould app, called the Tar Spotter app. The app will help increase awareness of the development of the disease, and help guide the decision for fungicide application.

There are still a lot of unknowns about the disease, but it is here and will likely continue to spread. Scout for the disease, pay attention to the weather, and manage accordingly. Be aware of the disease but don’t fear it.

TAR SPOT MONITORING AT IPMPIPECORN: https://corn.ipmpipe.org/tarspot/

CROP PROTECTION NETWORK: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/

OMAFRA FIELD CROP NEWS: https://fieldcropnews.com/

No matter how challenging your needs, BKT is always with you, offering a wide range of tires tailored to every need in agriculture: from work in the open field to the orchards and vineyards, from high power tractors to trailers for transport.

Reliable and safe, sturdy and durable, capable of combining traction and reduced soil compaction, comfort and high performance.

BKT: always with you, to get the most out of your agricultural equipment.

Addressing common weed-control questions.

Presented by Breanne Tidemann at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Weeds. They’re everywhere. Breanne Tidemann, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, fielded agronomist and farmer questions at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

Which weeds will cause western Canadian farmers the most grief five years from now, in 2026?

Kochia and wild oat. These two weeds have been a problem for a long time. Wild oats have been in the top five weeds in weed surveys since the 1970s and kochia is an up and coming problem, although in some areas it’s a very established problem.

But there are two other weed species that aren’t established here in Western Canada that, if they do become established, will be very scary weeds to deal with. The first is Palmer amaranth. It is a very difficult weed to control in the U.S., and it recently became the first broadleaf weed species to become resistance to glufosinate (Liberty) in the world.

The other one is waterhemp. It is a problem in Ontario, and glyphosate-resistant waterhemp has been found in Manitoba.

What are the best practices if a farmer has Group 1 + Group 2resistant wild oats?

The first answer is that you should be using all the same practices that you should have been using before you developed

resistant wild oats. Use alternative modes of action. Look at layering of alternative modes of action. Use good crop rotations. Increase seeding rates for a more competitive crop. Incorporate mechanical control like silaging if possible. Use patch management.

Test the wild oats to determine what resistance you have, or at the very least keep good notes and scout. Cross-resistance in Group 1 and Group 2 herbicides is hard to determine, so you have to test to see what herbicides are still effective in those Groups, if any.

What about field horsetail?

If you have it in your field, you know that it is hard to control. There aren’t any really good recommendations for control. It reproduces by rhizomes and spores. The green growth that herbicides are applied on is only vegetative growth, so it isn’t controlling the reproduction structures. I don’t believe there have been any studies looking at controlling the reproductive structures. It’s an area that needs work but is tough to work on as the impact can be quite localized.

ABOVE: Wild oat will continue to cause weed control problems.

If you could receive unlimited funding, what would you research?

There are so many, but two in particular right now would be interesting to look at. The first is looking at integrated weed management of wild oat, and how the initial wild oat density would affect the wild oat control. This has huge implications on how well integrated practices might work under high wild oat pressures.

The other is something I’ve noticed over the last few years, and that is broadleaf weeds with three cotyledons – tricots. I’ve seen it in cleavers, lamb’s-quarters and shepherd’s purse. We don’t know what it means, how frequent it is, relationship to seed production, or resistance development. It’s a big question mark, which makes me want to dig in and learn more.

What weed control practices have been successful?

There is a better understanding of integrated weed management practices because of the work of some of AAFC’s former weed scientists like Neil Harker, Bob Blackshaw, and Hugh Beckie. As far as weeds go, the problem for individual weed species can be cyclical. They disappear for a few years and then come back to be a problem. And that is likely related to weather patterns.

What weed issue has been the most surprising in your career?

For me, I think it has been how much weed issues change over the years. One year we had a really wet season, and one weed that had never been observed was all over a field – marsh cudweed. Neil Harker had seen that field for 30-plus years and had never seen the weed there before.

Has there been any gene sequencing to compare wild oat populations between countries?

Wild oat is a very complex genome so gene sequencing is very difficult and expensive. I’m not aware of any sequencing that has been done on the whole genome. There’s been some sequencing of herbicide resistance markers, but not the whole genome. There were studies in the ’80s and ’90s in the U.S. that looked at wild oat populations from the U.S. and Canada. They found there were different biotypes that emerged at different time, shattered differently, and varied in seed production. But they didn’t look at product performance.

What are your thoughts on not applying herbicides in years with low wild oat population?

It depends on what other practices you are using if you aren’t applying a herbicide. Can you prevent them from setting seed? Are

you harvesting early to prevent seeds from maturing, or are you harvesting and spreading seed around the field? Using multiple tactics will be beneficial. Economics come into play as well.

What can be done to slow the development of glyphosateresistant wild oats?

First, add another herbicide that is effective on wild oats when using glyphosate in a pre-seed burndown. Use all the integrated strategies that can help keep wild oats under control.

Is there a threshold for a percentage of the population to have herbicide resistance when you should stop applying that herbicide?

The first answer is if you have alternatives, then stop using that herbicide even if the percentage of the population with resistance is low. By continuing to apply the same herbicide you will only select for those weeds that are resistant.

If you think there aren’t alternatives, make sure this is the case. Maybe there are soil-applied herbicides that you don’t want to use but would be effective. If no other options, try to reduce the numbers that are being selected with the herbicide. Look at using alternative management strategies to try to keep the herbicide resistant population down. Seeding rates, crop rotation, layering, and physical management with patch management.

What one weed management tactic that more producers should know about?

I think it is more about “what do I wish producers knew about weed science.” What I want to emphasize is that we aren’t researching solutions. There will never be a tactic that will complete solve or eradicate a weed management problem in my opinion. Every tactic that you apply to a weed adds selection pressure. Mother Nature always wins. We are researching tools to better manage weeds but we need to stop expecting a silver bullet solution to solve the problem.

Watch the entire presentation from the

Feb 23-24, 2021

Checking in on pulse crops in Western Canada.

Presented by Robyne Bowness Davidson as an on-demand session for the 2021 Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Pulse crops are an important part of western Canadian crop production. Robyne Davidson, pulse research scientist with Lakeland College, gave a pulse crop update with key production tips at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

Overall, pulse crop acreages have been fairly stable over the last five years. Saskatchewan has the majority of the acreage around 6.7 to seven million acres with Alberta and Manitoba around 1.8 to two million acres each.

Field peas represent the majority of the acreage on the Prairies with around 2.2 million acres in Saskatchewan and 1.7 million acres in Alberta. The fractionation plants in Manitoba are having a big impact on the acreage there, rising from 76,000 acres of field peas in 2017 to 176,000 acres in 2020.

Lentil acreage has been pretty constant in Saskatchewan around four million acres over the last five years. Lentils exploded in Alberta in 2016 going up to 565,000 acres from 140,000 acres in 2010. Acreages in Alberta leveled off around 450,000 acres, mostly red lentils, and have a strong hold here.

Faba bean acreage moved up in the mid 2010s with 110,000 acres in Alberta and 60,000 acres in Saskatchewan in 2015.

Lack of markets and several dry years has impacted that acreage with about 40,000 acres in Alberta and 86,000 acres in Saskatchewan in 2020.

Chickpea acreage is fairly stable with most of the crop grown in Saskatchewan at 250,000 acres. Alberta acreage varies between 10,000 to 60,000 acres.

Manitoba grows the bulk of the dry beans averaging around 135,000 acres over the last five years, and about 55,000 acres in Alberta.

There has been a tremendous amount of interest in soybeans over the last five years. Alberta tried to grow them reaching 25,000 acres in 2018 before we realized that they are currently not economical here. Saskatchewan keeps trying with acreage as high as 850,000 acres in 2017 but that has dropped down to 127,000 acres in 2020. Manitoba is where soybeans have taken hold and flourished with about 1.6 million acres recently.

ABOVE: Chickpea acreage has remained fairly stable in Saskatchewan.

One new crop to keep an eye on is lupin. It is a very popular crop in Australia and Europe because it is super high in protein. Some processing companies in western Canada are interested in lupin, so we are conducting research looking at agronomics. They don’t seem too difficult to grow.

For practical agronomic tips, the number one tip is to look at field selection. Start with clean fields because pulses don’t compete with weeds very well, and for some broadleaf and perennial weeds, there aren’t many herbicide options. Lentils, peas and chickpeas do well on lighter soils, and faba beans and soybean do better on heavier soils.

Seed pulses early. They have good frost tolerance and can be seeded before other crops. Although seed size is different for the pulse crops, seeding depth is fairly similar. Make sure they go into moisture.

Every pulse crop has a different inoculant, so make sure you use the proper inoculant for the crop that you are growing. A big benefit of pulse crops in nitrogen fixation, so you want to make sure you are capturing that benefit.

Ensure good stand establishment because you don’t want to start with a poor plant stand that can’t compete. Use clean seed and a fungicide seed treatment for root rots. Ensure your seeding rates are accurate.

Rolling after seeding is important so that harvest is easier and you can catch the low hanging pods. Rolling is important for most of the pulse crops except faba bean that grows taller. But don’t roll when conditions are wet because that can encourage leaf disease.

Keep on top of weed issues – that starts with field selection. Check any recropping restrictions that might impact the crop.

When desiccating, hit the correct timing. Desiccating lentils too late can result in shattering losses. I highly recommend Reglone as a desiccant for a fast drydown. Glyphosate can be used but it isn’t a true desiccant because it has a slower drydown and is used more for perennial weed control in preharvest applications.

Scout your fields, based on what issues you’ve seen in the past. Aphanomyces root rot is likely to be a problem in pea and lentil, but it isn’t an issue in faba beans. Mycosphaerella and ascochyta leaf diseases will likely show up in field pea. Sclerotinia in lentils. Know the stages and symptoms for when to scout and what the control options are.

For foliar diseases, scout on a regular basis and use the thresholds and risk assessment tools to decide if you spray a foliar fungicide. In some years it may not pay to spray, and part of it comes down to your own risk tolerance.

Overall, it is important to know what is going on in your fields. Scout and keep on top of any developing issues. Pulse crops are a little more intensive to grow, but there are lots of resources available for pulse growers.

Practical management approaches and tracking resistance trends are the name of the game.

Presented by Hugh Beckie as an on-demand session for the 2021 Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Canada and Australia rank third and second globally when it comes to herbicide resistant weed cases.

Hugh Beckie, director of the Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative (AHRI) and professor of weed science at the University of Western Australia, discussed the similarities and differences in herbicide resistance between the two countries at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021. He previously spent 26 years as a weed scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon.

The Grains Research and Development Corporation, a federal Australian organization that funds research into crop and weed science, including herbicide resistance, established AHRI in 1998. AHRI is hosted at the University of Western Australia and has a 20-person multi-disciplinary team renowned for world-class research, development and extension in herbicide resistance.

Research conducted at AHRI ranges from the fundamental to the practical. One aspect of fundamental research, for example, is identifying genes that are responsible for herbicide resistance. Practical approaches focus on mitigating resistant weeds and providing solutions to growers to manage existing problems or avoid future problems.

In Western Australia, the most economically damaging herbicide-resistant weed is annual ryegrass, causing losses up to $100 million annually. Wild radish is the most important resistant broadleaf weed. It is very competitive, and is related to wild mustard in Canada. Both annual ryegrass and wild radish have widespread resistance to multiple modes of action.

In 2020, a herbicide resistance survey was conducted across Australia to provide an update on the status of the issue. The last survey was conducted five years ago.

An emerging issue for Australian farmers is the incidence of glyphosate resistance in weed populations. It is very low in the largest grain producing state of Western Australia, found in less than 10 per cent of fields. However, glyphosate resistance is becoming a problem in eastern Australia, particularly in New South Wales and Queensland, in annual sow thistle – a weed also commonly found in Canada.

Glyphosate-resistant wild oat has been confirmed in New South Wales and Queensland. Western Canadian growers

ABOVE: Canadian growers should be concerned about glyphosate-resistant wild oat.

should remain aware of the possibility of glyphosate resistant wild oat populations developing in their fields. They should look for signs of decreasing wild oat tolerance to glyphosate.

In Australia, public and private partnerships have made a concerted effort to raise awareness of herbicide resistance and its management with consistent messaging. The partnership is called WeedSmart and is headquartered at AHRI and the University of Western Australia.

WeedSmart has six core messages for growers.

1. Rotate crops and pastures. Include crop diversity and forages when possible to change weed selection pressure and increase the range of weed control options in a field.

2. Double knock to preserve glyphosate burndown. Typically a glyphosate burndown is conducted before seeding. Ten to 14 days later, an alternative herbicide is applied to control weed escapes prior to seeding. The second herbicide is usually paraquat, which is available in Canada but not frequently used.

3. Mix and rotate herbicides. This is the same message used globally.

4. Stop weed seed set. Crop topping is the term commonly used to describe a method to stop weed seed set before harvest. In Australia, paraquat is often applied to pulse crops. In Canada, glyphosate is often used in a pre-harvest application.

5. Crop competition. Australian growers use several components to improve crop competition with weeds. Adopting a narrow row spacing, as narrow as six inches (15 cm) using hoe or disc drills, is easily done with existing Australian seeding equipment. Seeding east/west gives crops more sunlight and shades the furrows to reduce sunlight for weeds. Increasing seeding rate and using a competitive variety also improves weed competition.

6. Harvest Weed Seed Control (HWSC). Australian

growers have used HWSC methods for many years. It is designed to prevent weed seeds from entering the seed bank. Techniques developed include chaff lining, chaff carts, narrow windrow burning and integrated weed seed destructors that mechanically destroy the seed.

The main differences between Australia and Canada are that Australian growers use double knock burndown applications, narrow row spacing, east/west seeding and a high adoption of HWSC. Australian growers also rely more heavily on preemergent soil residual herbicides because many post-emergent herbicides are ineffective due to widespread herbicide resistance.

Australian growers have been successful in managing herbicide resistant weed populations, and have been able to do it while still making money. They are generally optimistic because of the current and future introduction of new modes of action, which remains the most important weed control tool. The value of HWSC has been proven, even though it isn’t effective on all weeds.

The continuous improvement of crop varieties in terms of yield and weed competition is also reason for optimism. In 2025, wheat breeders in Australia will be introducing weed competitive genotypes bred to outcompete weeds.

Canadian growers, in particular western Canadian growers, should be optimistic that they can also profitably manage herbicide-resistant weeds. There is a need for public/private partnerships for research, development and extension. Consistent extension messaging from all stakeholders is important. Communicating grower experiences (testimonials) has been very impactful, whether it is one-on-one discussions, keynote presentations, or on social media.

Watch the entire presentation from the

Feb 23-24, 2021

Exploring the Canola Council of Canada’s goals and strategic plans for success.

Presented by Curtis Rempel as an on-demand session for the 2021 Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23-24, 2021.

Canola Council of Canada’s strategic plan calls for 52 bushels per acre sustainable canola production by 2025. Curtis Rempel, vice-president of crop production and innovation with the Canola Council of Canada, discussed how Canadian farmers can get there in his update at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

The Canola Council of Canada’s strategic plan was based on the global demand for canola’s high-quality oil with its healthy profile. When the plan was developed in 2014, yields were around 33 to 35 bushels and have grown, but in the last five years, they seem to have plateaued around 40 to 41 bushels per acre.

Genetics x environment x management are the factors that drive yield.

Environment is out of our control so we have to use Management – agronomy – to try to climate-proof our canola crops. Over the last few years the weather has been very variable with wet, delayed harvests, unseasonably high temperatures during canola flowering, and some extremely windy events.

The life sciences companies and plant breeders have done a tremendous job in developing hybrid canola varieties with the genetics to hit 52 bushels per acre. For growers, choosing genetics carefully and then applying good agronomic practices is how we will reach 52 bushels per acre.

The Canola Council has four pillars of agronomy to help reach that target. The first is stand establishment. It is really critical to get the crop off to a good start. Select genetics for each field rather than one hybrid for the entire farm. Know what is in the field for crop disease so that you can seed a hybrid with resistance if one is available. Ensure good seed and fertilizer separation

The optimum target plant stand is five to eight plants per square foot. Understand how Thousand Kernel Weight can impact seeding rates. The Canola Council has seed rate calculator tools to help determine the appropriate seeding rates based on germination rate and expected seedling mortality.

The fertility pillar uses the 4Rs of right rate, product, timing and placement. I’ll make a controversial statement, based on a lot of research, that I think canola is under-fertilized on the Prairies. Canola is high in oil and protein content, and both need nitrogen in a balanced program with phosphate, potash and sulfur.

The third pillar is integrated pest management covering insect pests and diseases. Scouting is extremely important. Find out what is in the fields, even after harvest you can scout and find evidence of blackleg, Verticillium wilt and sclerotinia.

I think farmers and agronomists have done a great job of using

economic thresholds to guide insecticide and fungicide applications. They don’t get enough credit for using economic thresholds.

Harvest management is the fourth pillar. Understand what your harvest losses are. Typically this takes time to measure, but ask what is the level of loss that you are willing to put up with. Harvest losses change throughout the day with changing temperature and relative humidity, so one setting for the entire day won’t minimize the losses. If losses are exceeding one or two bushels per acre, ask if it is worth stopping to check losses and make adjustments.

What the life science companies have achieved is unbelievable. They’ve developed genetics to deal with diseases like blackleg, clubroot pathogen variability, and the threat from Verticillium wilt. The breeders have developed pod shatter resistant hybrids. And with all these traits, they have kept the quality attributes as well. For growers, the next step is to have a more nuanced approach selecting hybrids for each field. Overall, we are getting the genetics to hit our strategic target.

The biggest challenge heading into 2021 and beyond will be how to manage in the warmer/drier cycle we seem to be in. Strategies could be to grow shorter season hybrids to try to beat the heat during flowering. Farmers should monitor soil temperature and moisture and make planting timing decisions to achieve targeted plant stands in order to optimize yield and minimize risk. The whole disease continuum from seeding to harvest will have to be monitored and managed.

There will be some new market opportunities in the coming years. The Canola Council is working with provincial and federal governments to see how canola production and biofuels fit into renewable energy initiatives.

The global movement to more plant-based protein will also benefit the canola industry. Pulse proteins are wonderful as well, but there is an opportunity to blend pulse and canola proteins to get a really favourable nutritional profile.

Canola protein will also continue to play an important role in animal protein. There is a saying that it takes good protein to make good protein, and canola has a good fit for monogastric animals, in dairy and in aquaculture.

My final message is to scout, scout and scout. Know what is happening in your fields and manage accordingly.

Watch the entire presentation from the Feb 23-24, 2021

Discover simply powerful disease protection for a wide range of crops

Explore the Miravis® difference at Syngenta.ca/Miravis

Always read and follow label directions. Miravis®, the Alliance Frame, the Purpose Icon and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. © 2021 Syngenta.

japonicum* *LALFIX® Spherical for Soybean is a high quality, two-strain in-furrow spherical inoculant with 1 x 108 viable Bradyrhizobium japonicum cells per gram. **LALFIX® Spherical for Pea & Lentil is a high quality, two-strain in-furrow spherical inoculant with 1 x 108 viable Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae cells per gram.

lallemandplantcare.com