TOP CROP MANAGER

COVERING YOUR GROUND

Cover crops prove valuable for producers

PG. 5

BOOSTING CORN AND SOYBEAN YIELDS

Add winter wheat and a cover crop in the rotation

PG. 8

LESSONS FROM #PLANT17

Tips to cope when soils are saturated

PG. 18

Cover crops prove valuable for producers

PG. 5

Add winter wheat and a cover crop in the rotation

PG. 8

Tips to cope when soils are saturated

PG. 18

5 | Utilizing winter cover crops

Cover cropping is gaining traction and garnering interest from a new generation of farmers.

By John Dietz

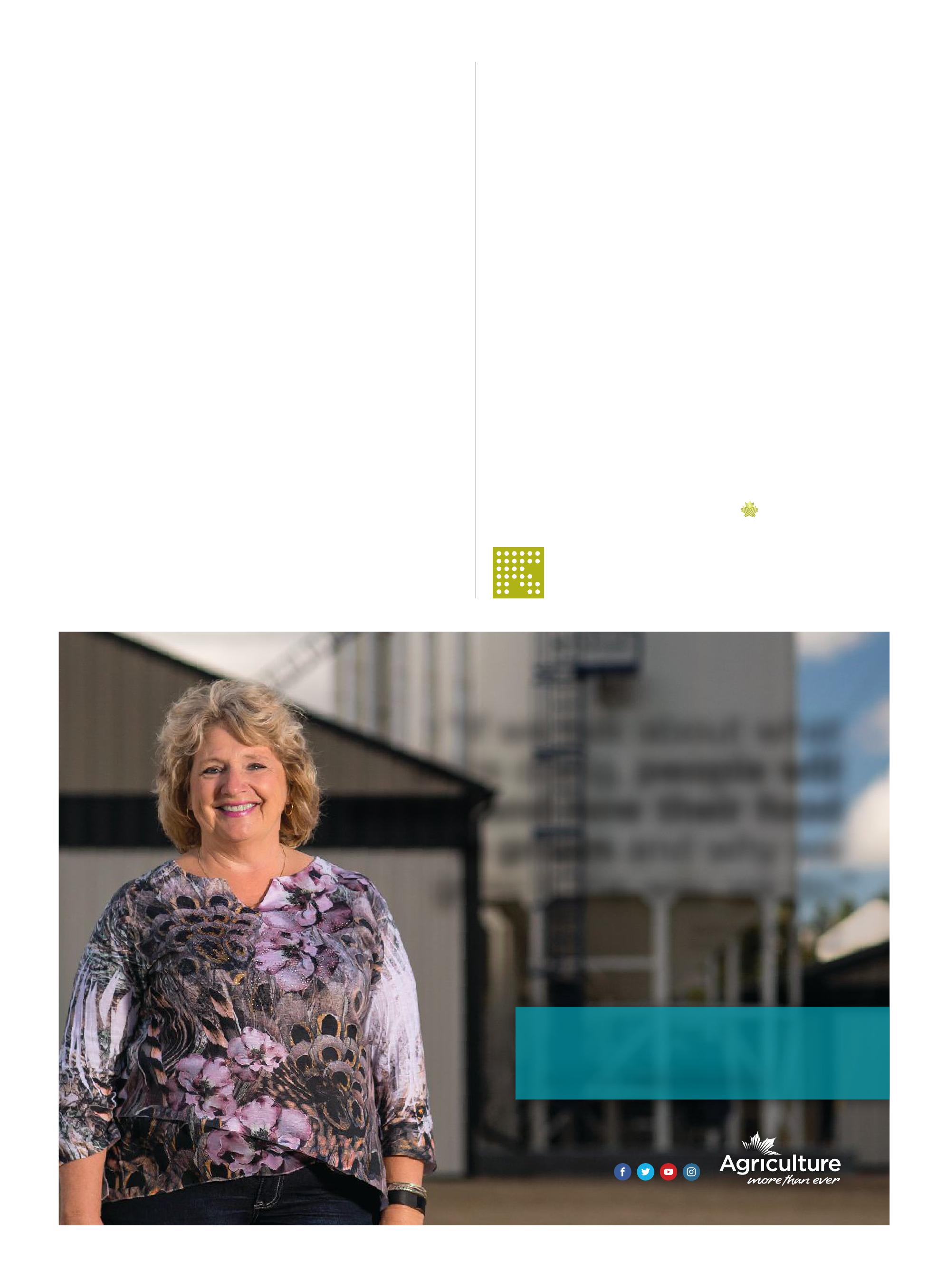

| Get in the groundwork

Improved soil health, yields and bottom lines can all be accomplished with a simple management change.

Rosalie Tennison

10

Mining the soil for data

Long-term research project to study the impact of cropping system on soil health.

By Helen Lammers-Helps

SUCCESSION PLANNING: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Whether you’re at the beginning of the succession planning process, in the midst of transitioning or are about to complete the process, there are different elements to keep in mind. We caught up with Terry Betker, president and chief executive officer of the management consulting firm Backswath Management Inc., for advice at all stages of the process.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility

and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration

and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

BRANDI COWEN | EDITOR

This year’s “Canada 150” celebrations, marking 150 years since Confederation on July 1, 1867, have prompted reflection about the past, present and future of our country. Efforts to tell “the story of Canada” have led mainstream media to re-visit the feats of Canadians whose names usually appear in close proximity to the word “iconic,” including Alexander Graham Bell (inventor of the telephone), Agnes Macphail (the first woman elected to the House of Commons), Lester B. Pearson (the former prime minister who introduced universal health care and established the country’s reputation as a peacekeeping nation), Marc Garneau (the first Canadian in space) and Terry Fox (whose cross-country Marathon of Hope raised funds for cancer research), to name a few.

But then a funny thing happened and stories about lesser-known but no less influential Canadians started circulating – including a fair few from the agriculture sector.

Avid bakers learned they have David Fife to thank for establishing Red Fife wheat in Canada. Fife discovered the variety offered resistance to the rust that was costing many Ontario farmers their crops in the 1840s, plus excellent milling qualities that to this day make it a choice pick in specialty baking. It’s also a genetic relative to many earlier-maturing varieties of the wheat grown today.

Calgary Stampede fans discovered they owe a debt of gratitude to local ranchers Patrick Burns, Alfred E. Cross, George Lane and A.J. McLean for financing the inaugural Stampede in 1912. Today, visitors to the “Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth” spend an estimated $345 million at local hotels, restaurants and other businesses.

Oenophiles with a taste for home-grown vintages were reminded to thank Donald Ziraldo of Inniskillin Wines on Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula and Anthony von Mandl of Mission Hill Family Estate Winery in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley for pioneering the Canadian wine industry. According to the Canadian Vintner’s Association, wine tourism alone accounted for $1.5 billion in economic activity in 2015 (the last year for which this data is available).

The spotlight on Canadian achievements in agriculture may dim somewhat, now that the country’s milestone birthday bash is over. However, with exhibits like “Canola! Seeds of Innovation” now open at the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum in Ottawa and “Canola: A Story of Canadian Innovation,” travelling across the country to share the story of the “made in Canada” crop that now contributes more than $19 billion to the national economy each year, it seems the industry is far from finished celebrating our own iconic Canadians.

And with good reason: There are so many hard-working people in our sector, doing groundbreaking, future-shaping work. Appreciating that work requires that we reflect on the past, present and future of our industry on an ongoing basis.

In that spirit, Top Crop Manager has partnered with our sister publications – Canadian Poultry, Fruit & Vegetable, Manure Manager and Potatoes in Canada – to bring you Ag 150: The Past, Present and Future of Agriculture (ag150.ca). From Sept. 18 to 22, we’ll be delivering a daily e-newsletter straight to your inbox, looking back at some of the milestones that have shaped agriculture in Canada, and giving readers a glimpse of how new technology could shape the future. Sign up for Top Crop Manager’s e-newsletter at topcropmanager.com/subscribe to ensure you don’t miss out on this celebration of Canadian agriculture.

Here’s to the next 150 years of great Canadians and their great achievements.

Cover cropping is gaining traction and garnering interest from a new generation of farmers.

by John Dietz

Crowds, new ideas, research and equipment – something’s going on with cover crops in Ontario.

The number of farms using winter cover crops in Ontario nearly doubled between 2011 and 2016, according to provincial data from Statistics Canada’s latest Census of Agriculture, released earlier this year. Interpreting census numbers is a matter of some debate, but there are other indicators pointing to the growing popularity of cover cropping – such as attendance at agronomy events on the topic and on-the-ground observations.

Peter Johnson, Real Agriculture agronomist and program cochair for the Southwest Agricultural Conference (SWAC), says about 1,400 people attend concurrent sessions over the conference’s two-day program, held in early January each year at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown campus. The conference sessions are held in rooms with capacities ranging from 110 to 600 people. Johnson chooses which talks will be held in which rooms.

“We knew cover crops were ramping up three years ago, but I missed that in my room assignments. Rooms were overflowing and we had to turn people away from the cover crop topics,” Johnson says. “That was an eye-opener for me. The interest was much bigger than I realized.”

For this year’s SWAC conference, he placed the cover crop sessions in some of the largest rooms, with the soil organic matter session in the largest room of all. Once again, the rooms were at capacity.

“It looks like we will continue on that road for 2018. Soil health and cover crops go hand-in-hand. It continues to be a hot topic, and we will continue to meet that demand. Hopefully the interest continues, because it’s something that growers need to focus on,” he says.

The SWAC celebrates its 25th anniversary in 2018 and has welcomed a new generation of attendees since Johnson began his agricultural extension career 33 years ago.

“In my career, this is the third time cover crops have cycled. There is much more interest this cycle, with renewed interest in soil health and organic matter. Growers understand that they have to look after their soils better to achieve significant gains in crop yields,” he says.

In late April, considerable cover crop residue remains on the soil surface in Laura Van Eerd’s long-term cover crop experiments at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown campus.

Soybeans, grain corn and winter wheat are the most popular field crops in Ontario. According to the 2016 Census of Agriculture, about 12,000 farms grew winter wheat on a total of a million acres. About 16,000 had grain corn on 2.1 million acres and nearly 20,000 farms had 2.8 million acres of soybeans.

Ontario farmers have a wide window of opportunity to use cover crops, especially after the winter wheat harvest in mid-summer.

“It used to be that we would struggle to get a third of the [winter] wheat acres seeded with red clover. My guess now would be that at least three-quarters of the wheat acres have cover crops planted after wheat,” Johnson says.

However, it’s a different story for the corn and soybean fields. In the same areas, where up to 90 per cent of the wheat may have a cover crop, probably less than five per cent of corn and soybean ground has a cover crop.

But the uptick in interest has spurred research.

In recent trials, short-term results show corn can gain a nitrogen credit from red clover and other legume cover crops because the timing of nitrogen release from the legume is right when the corn needs it.

“With other [non-legume] cover crops, our research shows more nitrogen is available to the following crop. With corn, the plant sees more, but it’s not enough to lower your nitrogen fertilizer rates. And timing the release of nitrogen from the cover crop to the corn is very important,” says Laura Van Eerd, associate professor in the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown campus.

After a corn or soybean harvest, it’s too late in the season to plant a cover crop (other than cereal rye) and gain a payback in biomass before freeze-up.

But there are still opportunities to plant cover crops with corn, thanks to its wide row spacing and the rise in precision agriculture techniques. University of Guelph researchers David Hooker and Bill Deen, in collaboration with Van Eerd, have evaluated a

precision planter that can interseed three rows of cover crop seed during the V6 stage of corn planted on 30-inch rows.

The main limitation in field corn is lack of sunlight. If red clover can get to a decent level of growth before the corn canopy closes, it tends to go dormant. Later, when the corn leaves are drying down, more sunlight is available and the red clover may come back.

“It works, but it’s not an easy system,” Van Eerd says.

She’s demonstrated that the system works very well with seed corn production, as more light is available after tassels are taken off the plants. Interseeding can also work with silage corn, if the silage is off in early September.

Van Eerd participated in two of the 2017 SWAC cover crop presentations and has conducted long-term research in cover crops, soil health and nitrogen fertility. After 10 years of seeding the same plots with cover crops and comparing yields to adjacent plots without cover crops, one clear trend has emerged.

“We’ve seeded 122 cover crops. In 121 times, our following crop yield has been as good as or better with than without a cover crop. It’s not always statistically better, but only once was it statistically worse,” she says. “That ‘once’ was because we were preparing for tomatoes the following year and we had spring wheat after cereal rye. That’s a bad rotation to begin with.”

In the early years of the long-term trials, the focus was on minimizing nitrogen losses. More recently, Van Eerd has been looking at cover crop influence on soil health.

For instance, where her team has planted oilseed radish and

cereal rye mixture in the fall for 10 years, they measured a real increase in soil organic matter. Plots with cover crops had 3.5 to 3.6 per cent soil organic carbon, but plots without a cover crop had levels of 3.2 per cent.

“The change is slow, but it is doable,” she says. “Crops are responding to the cover crop, and we’re seeing differences in the soil itself.”

Farmers who have been thinking about trying cover crops in recent years will find there have been major increases in the number of resources available since the 2011 Census of Agriculture, says Anne Verhallen, a soil management specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Verhallen maintains a database of cover crop seeds and seed suppliers. She is also an editor of OMAFRA’s best management practice (BMP) for soil health series (omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/facts/cover_crops01/ covercrops.htm).

In response to the increased interest in cover crops, OMAFRA has published four new editions of BMPs for soil health since 2016. The series to date includes: cover crops and manure; interseeding cover crops; preplanned cover crops; and winter cover crops. The booklets are in segments for specific production systems, rather than a single large manual. In addition to new research, they collect older information that has been scattered in the literature and online.

A typical soil management BMP guide could be 60 to 70 pages. But OMAFRA’s booklets range from 10 to 20 pages. They have large pictures and are easy to read, so growers can better understand what’s going on in their soils and in plant roots when they use a cover crop.

Verhallen is also Ontario’s only representative on the 10-yearold Midwest Cover Crop Council (MCCC) executive in the United States. The council is actively producing print and digital resources (including fact sheets, online decision tools, applications, etc.) for those who want to dig deeper. (More information is available at mccc.msu.edu/.) For instance, the MCCC online decision tool allows a grower to select cover crops based on goals and climate and provides additional agronomic information for managing that cover crop.

The MCCC published the second edition of its Cover Crops Field Guide in 2014 with significant content from Ontario.

Cover crop science and reality,” one of the sessions at the 2017 Southwest Agricultural Conference in Ridgetown, Ont., asked a basic question: why plant cover crops?

Farmers at the session had many answers to the question – typical reasons given included the fact that it’s good for the soil, good for microbes, good for erosion control, good for weed control and good for crop nutrition and phosphorus levels. But these were not what a “big data” analysis, conducted by AnaÏs Charles and Anne Vanasse of Université Laval with collaboration by Laura Van Eerd, showed

Land Practices in Ontario as Reported in the Census of Agriculture Ontario Land Practices 2011

Provincial Sum

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 004-0208 - Census of Agriculture, land practices and land features, every five years.

As a land use, growers will find challenges and benefits from cover crops.

“Stats Canada shows some interesting trends,” Verhallen says. “Cover crops can help growers address challenges like soil erosion and declining soil structure, but cover crops do require management and knowledge.”

And that, according to Johnson, is why SWAC 2018 will include programming about new cover crop information in order to address the questions growers have about the practice and share what new research has found.

For more on crop management, visit topcropmanager.com.

after reviewing more than 2,400 paired data points.

The analysis drew on published reports from journals, as well as reported field trials collected in Ontario and in places with a similar climate. It compared yields with and without cover crops from the 2,400 data points.

“No one said yield was the main motive for planting the cover crop, but the analysis showed you can get yield boosts with the cover crop,” Van Eerd says.

“Among the 2,400 data points, yields with cover crops were as good or better 70 per cent of the time. Cover crops were

as good as or hurt the yield 30 per cent of the time. This analysis doesn’t explain the reasons, but the bottom line is that we see a positive influence on yield.”

While the analysis showed a yield benefit to cover cropping, she admits the benefit of a cover crop is not always tangible. It costs in seed and time to plant and it doesn’t always give an immediate, direct benefit.

“It is an extra level of management. Without a guaranteed benefit, that’s a barrier. The main time farmers can see a benefit is when there’s a windstorm. Your land isn’t blowing but the neighbour’s is, so you see that benefit.”

Improved soil health, yields and bottom lines can all be accomplished with a simple management change – planting winter wheat and a cover crop.

by Rosalie Tennison

Soil health is the basis of successful crop production. This is why more and more growers are doing the groundwork to preserve and improve this vital part of their operations. Some, however, still avoid it because they perceive it as an economic issue – soil improvement costs money, it doesn’t make money. Not so, say Ontario soil specialists. Crop rotation trials prove if growers take a longer-term view of their operation, there will be economic rewards, yield bumps and an improved crop production environment.

“From the long-term rotation and tillage plots managed by Dave Hooker, on average, between 2010 and 2016 a corn-soybean-winter wheat with underseeded red clover rotation saw an increase of nine bushels per acre in corn,” says Anne Verhallen, a soil management specialist for horticulture crops with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Though she deals primarily with tomatoes and such, Verhallen notes she’s increasingly dealing with field crops as vegetable growers use them as rotation options.

“Over time you have to apply the increase in corn yield to the previous wheat crop. Wheat gives you the option to use red clover, which in turn enhances the yield improvement from rotation,” she adds.

Building better, more resilient soils is a long-term process, but

farmers live in the here and now and many deal with banking partners who have a shorter-term view.

Long-term rotation studies at Elora, Ont., (since 1980) and Ridgetown, Ont., (since 1995) prove the value of using cover crops and adding winter wheat into a rotation. According to Laura Van Eerd, an associate professor with the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown campus, the objectives of the research are to study crop rotation and tillage operations. The research also looks at nitrogen application rates at Ridgetown. But the big takeaway message from all the research, led by Hooker and Bill Deen, an associate professor with the University of Guelph’s department of plant agriculture, has been that using cover crops and adding winter wheat into the rotation pays off in the long run.

“We can see there are measurable benefits with winter wheat in the rotation,” Van Eerd says. “There are benefits in improved organic matter and increased water filtration. Work by Drs. Deen and Hooker shows there are also corn and soybean yield bumps and corn needs less applied nitrogen fertilizer with wheat in the rotation.”

ABOVE: Red clover cover after wheat harvest.

Adding wheat into a rotation does not have to be difficult, Verhallen adds. “Soybeans or edible beans come off early, which allows wheat to be planted in September and then corn follows the next year. Adding that third crop will put money in the bank over the long term.”

“What we’ve seen in our long-term cover crop trials is an increase in soil organic carbon in our sandy loam soils and a slight yield boost,” Van Eerd continues. “We have intuitively known that cover crops improve soil, but we needed the long-term trials to allow us to measure the benefits.”

For many producers, cover crops require extra management. Putting wheat into the rotation means another crop to manage, but the rotation studies show increased profit margins when cover crops are added. Plus, there is the overall benefit to the soil, which will continue to improve and produce payoffs over time.

“I would encourage growers to start with winter wheat and plant a cover crop after harvest,” Van Eerd says. In years where there is production stress, such as dry years, she adds, the benefits of cover crops include minimizing yield loss. “We’ve seen in long-term trials a yield boost in sweet corn and green beans when cover crops have been consistently included in a rotation.”

Verhallen says farming is an intense profession, as growers manage schedules and logistics and deal with weather, pest and disease challenges. But, she adds, the research also supports a workload that’s easier to manage when winter wheat is added to the rotation. “Growers can be planting wheat by no-till as they are harvesting soybeans,” she explains.

“In extreme weather years, protecting the soil is going to make a difference,” Van Eerd adds. By adjusting production practices and adding

a cover crop and/or winter wheat into the rotation, there will be longterm soil health benefits and growers will be able to continue producing the food the world needs.

Verhallen believes good management will save producers in the years when climate extremes could make production difficult, such as very wet years or extremely dry years. “Adding wheat and a cover crop can make the difference over time when faced with less than ideal conditions,” she explains.

The discussion around adding winter wheat and a cover crop into a rotation to build soils and improve the bottom line is supported by concrete evidence, but some growers continue to resist the recommendation. In the University of Guelph trials, the proof was in the numbers. By putting winter wheat into the rotation, there was a five to six per cent yield increase in corn and a 10 to 14 per cent yield improvement in soybeans. Plus, growers have the wheat crop to sell as well, which made a tidy profit for those who grew it in 2016.

Work will continue in the long-term rotation studies, but the value of using wheat in rotation has already been demonstrated. Van Eerd and Kari Dunfield, with the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Sciences, are going to examine the biodiversity of the soil with a view to learning which combinations of crops will offer the most benefits to the soil. In the meantime, Verhallen will continue to sing the praises of cover crops and management concerns to all who will listen. Both are focused on building better soil health and productivity in Ontario soils. But expanding rotations to include winter wheat and cover crops are just one aspect of the equation. Doing the groundwork will improve production, the bottom line and soils.

by Helen Lammers-Helps

While the benefits of cover crops for soil health have long been touted by extension staff, it’s been difficult for researchers to determine how exactly cover crops affect the soil. That is until now. In 2016, an elaborate soil health monitoring system – the first of its kind in North America – was installed at the Elora Research Station, near Guelph, Ont.

Prior to installation, 18 soil columns were outfitted with multiple sensors at multiple depths for sampling soil water, nutrients and greenhouse gases. The measuring devices, called lysimeters, will be used to compare the environmental impact of two different long-term cropping systems. A conventional (non-diverse) corn-soybean rotation will be compared to a diverse rotation where cover crops and intercrops are included in a corn-soybeanwheat rotation.

Lead researcher Claudia Wagner-Riddle, from the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Sciences, says the instrumentation in these soil columns will permit researchers to monitor everything going in and out – something they could not do at the field scale without lysimeters. She notes there have been hypotheses that cover crops improve soil organic carbon levels, soil aggregation and soil structure, resulting in better moisture retention, but without lysimeters these effects have been difficult to quantify.

A 30-year comparison at the Elora Research Station, spearheaded by Bill Deen with the University of Guelph’s department of plant agriculture, ran from 1982 to 2012 and showed improved yields with increasing crop rotation complexity, but overall, there has been a trend towards decreasing crop diversity in Ontario. This lysimeter project will enable researchers to capture detailed data to measure the benefits of cover crops over time, Wagner-Riddle says.

In addition to evaluating how cropping systems impact soil health, the project will also measure the impact of crops on soil ecosystem services. These are the benefits to society, such as increased carbon sequestration, reduced nutrient leaching and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

The first year was used as a baseline to ensure the equipment was operating properly. With almost 500 sensors, Wagner-Riddle says there was quite a learning curve. This year soybeans were planted on the “conventional rotation” lysimeters, and wheat, which will be followed by a cocktail cover crop mix of five or six species, was planted on the other. Over the coming winter, the conventional treatment will be bare, while the other will be in a cover crop.

Managing the data is one of the biggest challenges of the research trial. “We are producing so much data,” Wagner-Riddle says. “We must stay on top of quality control.”

The sensors in the lysimeters automatically take measurements of soil water content, soil matrix potential (how tightly the water is held), temperature, and carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide concentration at five depths: five, 10, 30, 60 and 90 centimetres from the soil surface. The measurements are taken at set time intervals. Water samples can also be taken manually and sent to a lab for analysis.

Two soil types will also be compared in the long-term trial. Half of the soil cores are one metre in diameter by 1.5 metres

deep and contain an undisturbed silt loam from Elora. The others contain a sandy loam that was carefully extracted and transported intact from a research farm near Cambridge, Ont.

By taking a multidisciplinary approach that considers soil microbiology and the underlying mechanisms operating in the soil under different cropping systems, the researchers will be able to get a more complete picture of what is happening in the soil. Some of the questions they hope to be able to answer include: Are diverse cropping systems also beneficial for air and water quality? Are there trade-offs between soil, water and air quality upon implementing a diverse cropping rotation with a focus on carbon and nitrogen cycling?

And by manipulating some of the lysimeters to simulate warmer winters and summer droughts, the plots can also be used to compare the resiliency of ecosystem services to climate change in the conventional versus diverse cropping systems. For example, the researchers hope to be able to estimate how warmer winters would impact nutrient losses.

In addition to the vast quantity of detailed data collected, the project is also unusual in that, from the start, it is intended to run for 10 to 15 years.

Wagner-Riddle says this is important when it comes to measuring changes to soil health. “It’s not something you can see from one year to the next. You want to go through a few cycles of the rotations to see the dynamics and how it changes over time,” she explains.

While this experimental set-up is new to North America, there

“If

are 180 of these lysimeters already in use in Europe. Wagner-Riddle says information is being shared between these projects for maximum benefit.

A Soil Health Interpretive Centre, located near the lysimeter trial at the Elora Research Station, will showcase the study results and other soil health research results. The exhibits will be targeted to specific audiences, such as students or conference participants, Wagner-Riddle explains. She adds that the centre will be open for specific events and not on a drop-in basis.

This research was made possible by the efforts of many funding partners.

The soil research infrastructure is funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science.

Research being conducted at the site is funded by Grain Farmers of Ontario, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) and the University of Guelph, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada strategic research program.

The Soil Health Interpretive Centre is funded by the OMAFRAUniversity of Guelph knowledge translation and transfer program and is a collaboration with the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association and Hoskin Scientific.

A closer look at the grain filling process opens the door to exciting advances.

by Carolyn King

Innovative research is shedding new light on grain filling in oat, including the oft-overlooked occurrence of unfilled kernels. The research has overturned some common assumptions about oat grain filling and is opening the way to faster development of higher yielding and better quality oat varieties.

Art McElroy, research co-ordinator at PhytoGene Resources Inc., is leading this research. He has been interested in improving oat grain fill for a number of years. “I was intrigued by the fact that an oat variety might yield 6,000 kilograms per hectare in one location, but only half that in another environment. What yield parameters were changing? What stresses could be causing these differences? Was there genetic variability for stress resistance?” he says.

“The other big question was whether oat breeding could be much more effective if we had a better understanding of the dynamics of grain fill and the stresses that could be causing differences among lines.”

Highlights of findings so far

Since 2014, McElroy has been conducting a series of studies to

intensively examine oat grain fill using a novel approach: analyzing individual oat panicles.

“The first study involved determining the pattern of grain fill in plants from different genetic backgrounds in our breeding nursery. Each kernel in the panicle was weighed very precisely and its position within the panicle recorded: panicle node, branch from each node, position on that branch, and whether the kernel was primary, second or tertiary,” McElroy explains.

“No study of this sort had ever been reported for oat, and it revealed many surprises.”

One surprise concerned the relationship between the number of kernels and kernel fullness. “The number of kernels set was the most important determinant of yield, but there was no negative correlation between kernel number and average kernel size. Some plants with the most kernels also had the largest kernels,” he notes.

ABOVE: McElroy’s research shows unfilled oat kernels are caused by early-season stress during panicle formation.

“The biggest surprise though was [related to] a phenomenon that has largely been ignored in oat: the presence of unfilled kernels. These are empty hulls with only rudimentary floral or groat development. They are usually dismissed as kernels that the plant could not fill due to stresses during the grain fill. However, we found that unfilled kernels can appear anywhere within the panicle, which flowers and then fills from the top down, so their presence is not related to stress during grain fill,” McElroy says.

“The proportion of unfilled kernels was found to vary from less than five per cent to over 80 per cent, depending on genotype and environment. This is the second most important factor affecting yield – a huge surprise.”

McElroy suspects the important effect of unfilled kernels on grain yield may be related to the structure of the panicle’s plumbing system. It has generally been assumed that there is competition among kernels for carbohydrates, and also compensation: if one kernel is not able to fill, then its neighbours will benefit from the unused carbohydrates. Studies in the 1970s showed that if a primary kernel is removed, the associated secondary kernel will grow somewhat larger than expected. Carbohydrate partitioning among kernels was the obvious explanation.

Mimosa than at the other two sites.

The results confirm early-season heat and/or drought stress can increase the frequency of unfilled kernels. This effect occurs very early in the season when the panicle is being formed, well before heading. McElroy explains that the unfilled kernels can’t recover from this very early damage: “Even if you get good weather later on, they are not going to develop.”

Some of the oat lines were more resistant than others to those early-season stresses, so they had a lower frequency of unfilled kernels. The most resistant ones are now being multiplied for further testing.

“These findings changed our whole approach to oat breeding,” McElroy says. “We knew that the number of kernels set and their potential size are heritable traits and we have been selecting for those traits all along. But the frequency of unfilled kernels – also a heritable trait – is now a major selection criterion.”

McElroy and his team are now automating and mechanizing the panicle analysis process so they will be able to analyze tens of thousands of panicles by next year.

The results confirm early-season heat and/or drought stress can increase the frequency of unfilled kernels.

But this is not the pattern seen with intact panicles, McElroy points out. There was little or no compensation between associated kernels (primary or secondary) if one was unfilled. A literature search, going back to the 1950s, offered some clues. It appears each kernel may have its own pipeline – a vascular bundle – that originates in the stem. So, kernels along a panicle branch do not draw carbohydrates from a shared carbohydrate pipeline, but each has its own independent food supply. Therefore loss of a kernel means loss of carbohydrate transport from the stem to a developing kernel, and a direct loss in yield potential.

This effect occurs very early in the season when the panicle is being formed, well before heading.

In a new project funded by GFO, McElroy is working on an initial evaluation of the potential for using molecular markers to screen for the grain fill parameters. Such markers could really improve the efficiency of screening for the traits.

McElroy and his team then studied grain fill pattern over time, using two oat varieties sampled at three-day intervals from heading to maturity. According to McElroy, “The data fit the ‘one pipeline per kernel’ model to a tee.”

A subsequent experiment assessed herbicide impacts on the frequency of unfilled kernels. Some British research from the 1950s had shown 2,4-D applications could result in more unfilled kernels. So the PhytoGene team evaluated the effects of a broadleaf herbicide (bromoxynil and MCPA ester) applied on 50 oat lines at two growth stages. They found some differences between the treated plots and the check plots, but those differences were genotype-dependent.

The next aspect to investigate was the effect of environment on the frequency of unfilled kernels and the interaction between different lines and environments. This was undertaken in 2016, with support from Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO). The PhytoGene team evaluated kernel fill in 100 oat lines grown at three contrasting locations in the province: Cumberland (near Ottawa), Mimosa (near Guelph), and New Liskeard (Temiskaming Shores). Cumberland and Mimosa encountered record early-season drought. Yields at Cumberland were mediocre at best, while those at Mimosa would make the crop not worth harvesting commercially.

Interestingly, it was the number of kernels set and the level of unfilled kernels – an average of 81 per cent at Mimosa – that were most closely related to the yield differences among sites. In fact, the thousand kernel weight of filled kernels was slightly higher at

He is collaborating on this project with the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre (CDC). The CDC has evaluated 70 advanced oat lines for an array of 6,000 markers. This array identifies common variants in the oat DNA and their locations on the genome.

McElroy and his team are growing the 70 lines in replicated trials at Cumberland. They will analyze panicle samples to determine the grain fill parameters for each line and then attempt to find associations between marker presence and specific grain fill characteristics.

This technique is a fast way to get a first look at which markers could be associated with the grain fill parameters.

The alternative technique would be, for example, to find several closely related families that are breeding true for a high or low number of filled kernels and then do a detailed genetic analysis of those groups of families. McElroy and his team are collaborating with Céréla, a breeding company in Quebec, on this technique for marker development.

McElroy’s novel approach to investigating grain fill – examining the characteristics of individual panicles – is really paying off. His studies are increasing scientific understanding of oat grain fill and the stresses that influence it, as well as creating a more effective oat breeding strategy for PhytoGene. He adds, “Identification of molecular markers associated with enhanced grain fill would be icing on the cake.”

For oat growers, McElroy’s research could make a big difference. “This research should accelerate the development of higher yielding oat varieties, with more yield stability and much better test weight.”

GLOBAL EFFORTS TO PREVENT HERBICIDE RESISTANCE

Mark Peterson • Herbicide Resistance Action Committee

HERBICIDE USE IN CANADA: RESULTS FROM TOP CROP MANAGER’S INAUGURAL SURVEY

Gerald Bramm • Bramm Research

Sponsored by

MANAGING RESISTANCE WITH SPRAYER APPLICATION TECHNOLOGY

Tom Wolf • Agrimetrix Research & Training

NON-CHEMICAL WEED CONTROL METHODS

Steve Shirtliffe • University of Saskatchewan

CONTROLLING GLYPHOSATE-RESISTANT WEEDS: AN ONTARIO PERSPECTIVE

Peter Sikkema • University of Guelph - Ridgetown

To stay viable and competitive in the face of steadily increasing input costs, farmers need to optimize every input. In the future, most farmers will likely use variable rate input application as one of the key tools to achieve that optimization. However, those farmers interested in being early adopters of variable rate seeding (VRS) should understand the technology is not as simple as applying it and immediately reaping the rewards.

BY Madeleine Baerg

Precision mapping technology is increasingly user-friendly. In fact, Aaron Breimer, general manager of precision agriculture consulting firm Veritas Farm Business Management, says some precision map-writing software is so simple a producer can segment zones or draw a boundary around a field with little more than the click of a mouse. The challenge is that the maps are only as accurate as the information used to create them.

“I taught my eight-year-old nephew how to draw prescription maps in about five minutes. The mechanics are so easy. But, if you used his maps, they obviously wouldn’t be right because he’d just be guessing,” Breimer says.

The basis of a successful variable rate seeding program is quality, accurate and detailed spatial information in order to exploit the differences in a landscape.

Developing a prescription map requires layering multiple pieces of data to differentiate areas requiring different management. The most common starting place is to layer multiple historical yield maps, preferably from the same crop type. To refine the picture, one can then layer on satellite photos, drone imagery, pH and salinity maps, soil sampling results and/or other data.

However, the reality of mapping is not quite as simple as it might sound. Few farmers have multiple years of historical yield data, especially from the same crop. Breimer suggests working with available data – even from just a single year – to avoid a significant lag in technology adaptation (so long as it is high quality and from a year that is average to slightly dry).

“The right year will give you pretty good zones and additional data information, such as soil tests, can help you understand how those zones should be managed or what the limiting factors are,” he says.

An even bigger issue than the amount of historical data available is the quality of that data.

“One of the bigger challenges we’ve found is that growers incorrectly think they have good historical yield data,” says Ian McDonald, a crop innovations specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) who is currently collaborating on a four-year precision agriculture advancement research project. “What has shocked both us and them is that what farmers often think is good, high-quality data really isn’t.”

Creating stable, reliable management zones requires patience and due diligence; McDonald advises collecting as much data as possible, focusing on quality and accuracy and, ideally, starting long before one actually intends to begin implementing precision agriculture on their fields.

In addition, Breimer says growers who are successful in variable rate seeding tend to work closely with both their seed dealer and an equipment expert to ensure seeding rates and plant population counts are correct.

The second challenge to building reliable prescription maps is that many of the data layers don’t line up as neatly as one might expect, explains Nicole Rabe, a land resource specialist with OMAFRA’s environmental management branch. Rabe is working with McDonald on the precision agriculture research project.

“Everyone talks about collecting all these layers of data, throwing them together and just like that, you create perfect management zones that can stand the test of time. That’s not how it works, unfortunately,” she explains. “Sure, we can build you a map. But is it right? What we’ve been endeavouring to answer with our research project is: ‘What are the best base layers of information you can use to develop management zone maps?’ ”

At issue is the fact that different crops respond differently to various treatments. For example, it’s possible to combine corn and cereal yield data for the purposes of prescription mapping, but you can’t necessarily add soybean data because it has the potential to skew the data for corn and cereals. And various inputs react differently with varying soil conditions,

BY

1. Start with high-quality historical data. Prescription maps are only as accurate as the information used to create them.

weather realities, plant biology and other factors.

“Management zone lines might actually be very different for seed versus fertilizer versus some other treatment, which makes it very difficult from a management standpoint,” McDonald says. “Nature doesn’t respect hard, neat map lines the way human beings might want it to.”

In order to work with these challenges and still get value from precision agriculture, farmers need to respect and rely on their own knowledge and accumulated experience. “I can’t stress enough that the very most important data layer when building a prescription map is the one between a farmer’s ears,” Breimer says. “A farmer can look at a map that we create using various other data layers and will know instantly which parts ring true and which parts might not feel right. It’s very important to trust and incorporate that knowledge.”

Another common challenge is that farmers lack defined goals or may have difficulty measuring whether goals are being met.

“We realized quickly that prescriptions were being applied but growers were not doing any follow up to determine whether the prescriptions were right,” Rabe says. “One of the big things our project is trying to figure out is how do you validate that the prescriptions you’ve used are the right ones? Without validation or proof, there’s no way of knowing whether it’s paying off consistently.”

While maximizing yield or optimizing inputs are important achievements, a successful precision agriculture program should work towards achieving measureable return on investment. Most commonly, that return should be measured in dollars and cents, though improved environmental impact or other priorities may take precedence.

“So far the industry has not pushed itself to measure value,” Breimer says. “A lot of precision ag is about selling stuff. If you are a seed company, you want to sell more of your seed. If you’re an equipment dealer, you want to sell more equipment. There hasn’t been a focus on selling solutions for the sake of a solution. That said, I’d say north of 75 per cent of farmers could make money – a minimum of a three to one payback – from variable rate seeding, done right.”

But analyzing return on investment remains challenging.

“The vast majority of people say they understand the mechanics of precision agriculture. It makes sense to put more seeds there, more water here. But does it make dollars?” Breimer says. “You’re getting into pretty advanced statistical analysis tools to figure out if it makes money. Usually, we’d evaluate one strip by comparing it to a control strip right beside. With variable rate, the whole point is to get maximum variability. As soon as you have maximum variability, it’s nearly impossible to do a return on investment calculation.”

Rabe says the industry can expect improvements in statistical analysis over time. “It’s an evolving process, an evolutionary thing,” she notes. “As time goes on, we’ll be able to stamp out patterns and all of this will become more easily manageable. But growers need to understand that right now, it’s not a one-stop shop and you won’t get a silver bullet answer in one year.”

For now, all but the most statistics-savvy producers should work with precision agriculture experts to ensure their efforts are rewarded with real returns.

“Guys debating whether they want to jump into variable rate seeding and other precision ag technologies need to remember: you don’t have to use this technology,” Breimer says. “But you’ll be competing against people who are using it. If they do a better job or they can be more efficient because of precision agriculture, they’ll have the competitive advantage.”

2. Establish what you hope to accomplish with your variable rate seeding program. Set clear goals and decide how you will define and measure success.

3. Consult with seed dealers and equipment professionals to ensure you're using the correct seeding rates and plant populations in your fields.

4. Ask the experts to help you interpret and evaluate your results. Determining whether the payoff from a variable rate planting program is worth the time and money invested can involve complex statistical analysis.

5. Trust your own knowledge and experience. Prescription maps don't always tell the whole story, so it's important to review them regularly and make note of any oddities that don't jibe with past observations and experiences on your land.

There are ideal years for crop production… and then there are years like this one. This spring’s cool, wet weather across much of southern Ontario forced a late, slow start in many agricultural fields. While some management techniques can help mitigate crop health challenges and yield losses caused by less than perfect growing conditions, this year is proof once again that Mother Nature ultimately calls the majority of agriculture’s shots.

BY Madeleine Baerg

Across most of south-central and southeastern Ontario, there’s been 50 to 100 per cent more rain than normal,” says Scott Banks, a cropping systems specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). “It’s certainly been a challenging year. There isn’t really a silver lining to all this rain: no crops like being so wet. But growers have experienced tough years before. Outside of controlling the weather, there isn’t a whole lot they can do other than trying to minimize the issues and crossing their fingers for a warm, open fall.”

Once farmers gained access to fields this spring, many struggled with what to plant into the still over-wet ground. Few crops fare well in a muddy, smeared seedbed. However, some crops can tolerate moderately wet feet better than others – corn can manage slightly more moisture stress than soybeans and oats tend to suffer less than barley.

Because moisture is conducive to disease development, in wet years producers should choose varieties that offer strong resistance genetics to the diseases most common in their fields or area.

“Variety selection continues to be the most important tool available to producers from a disease management perspective,” says Albert Tenuta, OMAFRA field crop pathologist at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown campus. “Often producers choose the highest yielding variety or hybrid but they also need to be looking at disease resistance. Disease resistance genetics are critical to maximizing yield and returns.”

To complement strong genetics, producers should also make agronomic choices that minimize disease, including applying fungicidal seed treatments, planting at proper timing to support quick emergence, being ready with subsequent fungicide applications where necessary and utilizing cultural practices such as good rotation and drainage.

Genetic resistance is not yet available for some of the most problematic soil-borne diseases, including Pythium, Fusarium and Rhizoctonia in corn. Producers who have battled these diseases in the past might opt to plant an alternate crop in a cool, wet year.

After producers decided what to plant in their fields, they faced a whole different problem: research shows 80 per cent of soil compaction occurs on the first pass when growers move equipment through fields that are just dry enough to begin working. Soil compaction causes a whole host of issues, from impeded root growth to decreased water, nutrient and air flow through soil. While patience is the very best option, dual wheels, low pressure tires and large flotation tires can reduce compaction somewhat.

To remediate compacted soils and improve drainage for future years, growers should consider incorporating cover and forage crops. A deep rooting forage like alfalfa creates channels that help water percolate down deep into the soil, while grass forages and certain other cover crops have fibrous root structures that mellow the topsoil. In addition, cover crops reduce erosion, limit nutrient runoff and can disrupt pest outbreaks – all major benefits in wet years. They can also help minimize the soil crusting that’s common when waterlogged soils dry, which will otherwise decrease water and air penetration and obstruct seedling emergence.

Those farmers tempted to plant the most immediately lucrative rotation – a straight soybean or cornsoybean rotation – should first analyze the long-term benefits of incorporating forages. Forages’ positive effect on the soil’s physical, biological and chemical attributes, particularly in wet years, can result in higher yielding

subsequent crops, evening out the financial equation. While improvement is slow – good soil structure can take years to develop – the benefits are equally long term.

Sometimes even the most well structured soil simply can’t manage the volume of water that flows onto it in a wet spring. In saturated soils, adequate drainage can make or break a crop. Though installing drainage is a daunting upfront cost, Banks says the investment virtually always pays dividends in heavy soils prone to excess moisture.

“Like the old saying goes: you’ll pay for drainage one way or the other. You’ll either pay to put it in or you’ll pay in lost yield. In terms of getting a crop established and thriving, those with better drained fields were many steps ahead this year.”

Luckily, not all moisture management priorities require costly financial investments: scouting requires only the investment of time. In cool, wet years, disease pressure tends to be high, both because the conditions suit disease proliferation and because weather-stressed plants are less able to fight off disease. This year stripe rust and corn rust both blew in and took hold early, and at press time, Fusarium was expected to be an issue due to moisture.

Unfortunately, increased disease pressure this year will translate to higher disease risk in subsequent years.

“As you build up disease levels in fields, your risk increases. Pathogen populations can build to the point that they become chronic,” Tenuta says.

Growers thinking they can breathe a sigh of relief on the insect front are mistaken. While wet years tend to support disease and dry years usually support insects, pests don’t always follow the rules.

Despite the excessive moisture, pockets of southern Ontario are facing significant potato leaf hopper pressure. Although they are typically found in new seedling alfalfa, leaf hoppers are actually

chomping their way through established alfalfa stands this year, suppressing growth in mature plants.

“You’ve absolutely got to keep scouting your fields, even if you wouldn’t expect to see specific pests,” Banks says. “Pests can come up from the U.S. on currents of warm air even when conditions might not seem ideal here. And the beneficial insects that would normally control them might be delayed due to our weather conditions, so they might not be able to suppress them as they typically could.”

Farming is risky; farming in a cool, wet year that does not support strong crop growth is especially risky. As such, Tenuta has one other piece of early season advice for growers to keep in mind as they start planning for 2018: “One of the very most important management tools is to have a backup plan. You need to be prepared for the worst: what is your plan if you lose part of a field? What is your trigger for replanting? At what point should you decide to start all over again?”

But, he continues, even the worst-case scenario is not all bad.

“Everything you learn from this year –every piece of information you gain every year – is valuable. The more information you have and keep, the better you will be prepared for next year.”

LOOKING BACK AT #PLANT17

@OntarioFarms on March 20, 2017

Today marks the #firstdayofspring and the start of a fresh new year on many Ontario farms #plant17 #ontag

@MayMayhaven on April 24, 2017

Preparing a cozy seed bed for grain and hay seeds today in Southern Ontario. Anyone else on the land? #plant17 #OntAg #cdnag #farm365

@MatthewPot on May 1, 2017

Not sure when the clay regions in Ontario will be able to go in. Down in Niagara region it is pretty wet... No #plant17 anytime soon.

@_rjthompson94 on May 3, 2017

Significant snow in the U. S. mid-west, flooding rains in Ontario. Will it be a June #plant17?

@vantaygefarms on May 12, 2017 #plant17 getting rolling in southwestern Ontario.

@LeveilleDominic on May 20, 2017

75% in the ground here in northern Ontario, it’s a pretty average #plant17 year

@dfergusonGGF on June 11, 2017

It’s finally over, I don’t think I’m ever going to forget this one. #plant17 is in the books #ontag

by Carolyn King

One of the toughest challenges for young farmers is the uncertainty around what the plan is for the family farm in the future and how they fit into that plan.

Farm transition planning brings certainty.

“Farm transition planning – also called succession planning –ensures farm business continuity: it is the only process that links one generation to future generations involved in the farm business and addresses how the vision, goals and dreams of the farm will carry on,” says Heather Watson, executive director of Farm Management Canada (FMC).

“According to the data just released for the 2016 Census of Agriculture, less than 10 per cent of Canada’s farmers have a succession plan, while we expect three out of four of Canada’s farms will change hands over the next 10 years. Agriculture will experience what farm family coach Elaine Froese calls ‘the tsunami of agriculture,’ whereby today’s farmers will transition not only their assets, but their managerial and leadership skills to the next generation.”

Froese, who has been working with farm families for almost 39 years, easily identifies many challenges that can crop up for young farmers in the farm transition process. She highlights a few examples.

“A lot of young people are very frustrated that they spend five, six, 11 years on the farm and nothing has been planned or put into an agreement. They feel like they are in what William Bridges [an authority on change and transition] called the ‘neutral zone.’ The neutral zone is the pain of not knowing. It’s a place of high anxiety and stress because you don’t know what the plan is or what the future holds.”

A serious problem in some families is that the senior generation doesn’t respect the skills of the next generation. For instance,

ABOVE: As part of the successor development program, Hannah Konschuh (in black) attended events about farm management and transition planning, including this Agricultural Excellence Conference.

DO YOU RECYCLE YOUR PESTICIDE CONTAINERS? DO YOU RECYCLE YOUR PESTICIDE CONTAINERS?

There’s too much plastic waste making its way into our landfills, and the only way to address the problem is to go back to the basics: reduce, reuse, and recycle

Plastic is a key material in the world economy that can be found in virtually everything these days. Worldwide, 322 million metric tons of plastic were produced in 2015, and by 2050, that number could be four times higher.

Canada’s agricultural community uses a great deal of plastic. It can be found in bale wrap, greenhouse film, tubing and pipes, pesticide containers, grain bags, silage bags, twine, nursery containers and more. While plastic has become an essential part of modern agriculture, what to do with the material when it’s no longer useful is an ongoing challenge.

Historically, discarded agricultural waste has ended up in landfills or been burned or buried, sometimes on farm property. Landfills are difficult to site and expensive to manage and plastic buried in a landfill does not decompose, thus filling up valuable space. Burn barrels and other backyard incineration methods are also problematic because they can release harmful emissions in addition to wasting valuable resources.

Alternatively, recycled plastic can be reused to produce new products using fewer natural resources in the manufacturing process, eliminating emissions and saving landfills.

To help growers better manage their farm waste, CleanFARMS has partnered with agri-retailers and municipalities across the country. We work with more than 1,000 collection sites to make our programs accessible to growers in every region. The strong demand for CleanFARMS programs demonstrates the commitment of the entire agricultural industry to protecting our environment and preserving our resources for future generations.

Last year alone, more than 5.2 million empty pesticide and fertilizer containers were collected through a CleanFARMS program, and nearly 300,000 empty seed and pesticide bags returned. New technologies in a processing facility put all this plastic waste to good use after it was sorted, shredded and melted into useful materials like farm drainage tile.

CleanFARMS is now also developing a program to collect grain bags in Saskatchewan, along with bale wrap, silage bags and twine in several locations in Manitoba. We’re working with our partners to expand these programs to other provinces.

One in three Canadian farmers don’t return their pesticide containers for recycling. Are you one of them?

See how to rinse and recycle your pesticide containers the right way at cleanfarms.ca

While CleanFARMS plays in important role in protecting the environment by keeping recyclable materials out of landfills and burn piles, the work that we do is possible because of the support of our members and partners who share our vision and long-standing commitment to Canadian farmers.

For more information on how to better manage plastic farm waste, or to find a collection site near you, visit cleanfarms.ca

Barry Friesen, General Manager,

CleanFARMS

Froese knows talented, knowledgeable young farm women whose fathers won’t recognize their abilities, so they end up leaving the family farm. “Patriarchy is alive and well in agriculture,” she says.

“Another challenge is when the younger generation is not getting compensated enough to allow them to build up a pool of disposable income that they can allocate toward debt servicing because obviously they can’t be gifted everything. And therein lies another tension: how much is gifted and how much is purchased through debt?”

deal with the conflict, then you can actually make amazing decisions because everybody is feeling trusted and respected and heard.”

Work on filling any gaps in your knowledge and skills, and explore new areas that could lead to new opportunities for the farm.

Differing views on work-life balance can also create tensions that cloud the transition process. Froese gives an example: “I had a young farmer who would go in to read bedtime stories to his son and put him to bed. Even though he’d go back out, his father would get very angry with him for that. For young farmer men who are caught between pleasing their parents and trying to stay married, that is a huge challenge.”

Sibling conflicts can also tangle up transition planning. “[For instance,] with the huge value of land and assets in farming and the balance sheets having extra zeros on them, the greed factor rears its head. So you’ll have a farming child who wants to work with the business going forward, and then he or she discovers that the non-farming brothers and sisters feel like they need to get a quarter of the farm.”

And sometimes a young farmer’s biggest challenge is Grandpa. Froese says, “I have a family where the kids are leaving the farm because Grandpa is still holding on to the majority of the equity and wealth, and Dad at 56 still doesn’t even have it. These kids don’t see a hope of having the opportunity to grow in the future because Grandpa won’t transition the wealth.”

These types of issues need to be dealt with through honest, open and transparent communication. “People have to recognize the emotional factors affecting planning,” Froese notes. “Once you have everybody calm and talking and able to have adult conversations and

If you’re a young farmer tired of being in the neutral zone, it may be time to start taking action to move forward on transition planning. Working through the transition planning process provides many ways to help create certainty. Froese explains, “You can create certainty with talking. You can create certainty with putting steps and timelines into place. You can create certainty with agreements – operating agreements, partnership agreements, shareholder agreements – there are all kinds of agreements at your disposal to help you create certainty and also give you a solid income.”

Even if your family isn’t ready to talk about transition planning, you can begin learning about it yourself. A great place to begin is FMC’s website, which has webinars, articles, videos, podcasts and many other resources about succession planning.

Learning about transition planning could help you begin conversations with other family members and to champion transition planning in your family.

Most successful people are focused on continuous improvement and striving for excellence. You may already have many of the skills you need to eventually take over the farm, but there is always more you could learn. Work on filling any gaps in your knowledge and skills, and explore new areas that could lead to new opportunities for the farm.

This extra learning could give you more confidence in your own abilities and help you start the conversation on transition planning. And it could help your family see that you are committed to the successful management of the farm.

If your family is ready to think about transition planning, then one way to begin the process is to participate in FMC’s Step Up

From Heather Watson:

Do not assume that one day it will all be yours. Make sure there’s a formal farm transition plan in place. Be proactive. If your parents are reluctant to start the conversation, start developing your own plans. It may be your parents do not know where to start, or do not know you are ready for the conversation. Developing and sharing your plan might open the conversation and demonstrate your readiness to engage in the planning, as well as your leadership and entrepreneurial qualities. Take time to think about what role you would like

to see your parents (and potentially other family members) playing post-transition. Some parents fear life after transition. Mark down a date to confirm whether you are ‘in’ or ‘out’ as successor of the farm, and share this with your parents. This will help you and your parents set timelines for when things need to happen, including key conversations.

From Kyle Norquay:

Start the conversation. You may find that other family members are ready to start the conversation too. Tap into the wide range of resources

available to learn more about farm transition planning.

From Hannah Konschuh:

Learn and practice the skills you need to have farm transition conversations, such as how to conduct an effective meeting, how to get your point across, how to listen, and how to make sure everybody feels heard.

Access outside expertise where you need it – a succession specialist, a financial or a tax planner, or whoever you need – because a smooth transition is worth the investment.

to Succession program. It can help your family start laying foundations for a smooth transition of farm knowledge, skills and assets.

The program has two components: succession and transition planning workshops for farm families, and the successor development program for young farmers. FMC is working with Froese and business management consultant Cedric MacLeod on Step Up to Succession.

Watson says, “During the workshops, parents and children come together for help with farm transition. It’s a safe space where they can talk about issues and learn how to start and continue the conversation using many of the great resources and tools out there.” She explains that the Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture originated the concept for these workshops, and now with their blessing, FMC has incorporated the workshops into Step Up to Succession.

“The feedback from the workshops has been phenomenal,” notes Watson. For instance, participant Jim Pallister called the workshop “life-changing.”

Young farmers from across Canada have applied to the Successor Development Program, an exciting learning and networking opportunity. The successful applicants are sponsored to attend a series of industry events focused on farm business management and they and their families attend a transition planning workshop.

“The participants learn valuable skills and information to take back to the family farm. And the parents, through participation in the transition planning workshops, are receptive to positive conversations and actions towards securing the future of farming in Canada,” Watson explains. “These young farmers are building a strong peer network that will continue as a mechanism to share insights and best practices for years to come. The bonds we have seen develop between workshop participants and between these young farmers are truly spectacular.”

Hannah Konschuh and Kyle Norquay, who were among the 10 successful applicants in the inaugural successor development program, both emphasize the great learning opportunities and amazing peer network they have gained through the program.

In addition to Step Up to Succession, every year FMC hosts a Bridging the Gap Forum at its annual Agricultural Excellence Conference. Watson says, “The forum’s goal is to provide a place for different generations of farmers and industry stakeholders to focus on what needs to happen within the agricultural industry to ensure a bright future for Canada’s future farmers.” The next conference runs Nov. 21 to 23 in Ottawa.

A farm family coach can help your family with the sometimes difficult conversations around farm transition. Froese says, “You really need to get good communication happening first. That is what most families come to me for: untangling – figuring out what everybody wants and why and when.”

A coach can help get clarity on the goals, visions, values and timelines of each family member. These discussions will help the family work out how and when the transfer of ownership, management and responsibilities will occur.

Input from other advisors, like a financial planner, an accountant and a lawyer, can help you finalize your plan.

If you’re interested in hiring an advisor to help with your farm transition process, one place to look is the Canadian Association of Farm Advisors’ website, which lists many types of farm advisors, such

as farm family coaches, accountants, lawyers, agrologists and more.

For Kyle Norquay, one of the great outcomes from FMC’s successor development program is that he is now able to have farm transition conversations with his father-in-law.

Norquay is part of a mixed grain farming operation near East Selkirk, Man., about 45 minutes northeast of Winnipeg. “We primarily grow canola, soybeans and wheat, and some timothy,” he says. “It’s a true family farm – pretty much everybody is involved in the farm in some capacity, whether it’s making meals or driving tractors or whatever. My father-in-law, his brothers, his wife and his mom are all part of the show, and then me. My wife also helps out on the farm, but her studies keep her pretty busy – she is just finishing her degree in physiotherapy.”

After getting his degree in agriculture a few years ago, Norquay worked as an agronomist, but he is now working full-time on the farm. “I teach jiu-jitsu and do some custom field work, but my primary job is the farm.”

One of the reasons Norquay decided to apply to the program was to learn more about farm management. Although he understands how to grow crops, he knew very little about farm management. “I didn’t grow up on a farm, and I had no farm experience until I started dating my now wife.”

The first event that he and the other program participants attended was the Agricultural Excellence Conference in November 2016, which focused on farm business management and intergenerational communication. In December, they went to Canada’s Outstanding

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. These products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from these products can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for these products. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready 2 Xtend® soybeans contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate and dicamba. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate, and those containing dicamba will kill crops that are not tolerant to dicamba. Contact your Monsanto dealer or call the Monsanto technical support line at 1-800-667-4944 for recommended Roundup Ready® Xtend Crop System weed control programs. Roundup Ready® technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, an active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate.

Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individuallyregistered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole and fluoxystrobin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxystrobin, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn plus Poncho®/VOTiVO™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxystrobin, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-1582. Acceleron® Seed Applied Solutions for corn plus DuPont™ Lumivia® Seed Treatment (fungicides plus an insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxastrobin and chlorantraniliprole. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Visivio™ contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, thiamethoxam, sedaxane and sulfoxaflor. Acceleron®, CellTech®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity®, JumpStart®, Monsanto BioAg and Design®, Optimize®, QuickRoots® Real Farm Rewards™, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Xtend®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup Xtend®, Roundup®, SmartStax®, TagTeam®, Transorb®, VaporGrip® VT Double PRO®, VT Triple PRO® and XtendiMax® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. BlackHawk®, Conquer® and GoldWing® are registered trademarks of Nufarm Agriculture Inc. Valtera™ is a trademark of Valent U.S.A. Corporation. Fortenza® and Visivio™ are trademarks of a Syngenta group company. DuPont™ and Lumivia® are trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and VOTiVO™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license.

Young Farmers’ national event. He says, “That event recognizes young farmers from all across Canada who are at the top of their field and doing unique things and really moving agriculture forward. So that was more about inspiration to do great things with your farm.”

In February, Norquay and his father-in-law attended FMC’s transition planning workshop in Manitoba. In late February, the program participants went to the Canadian Young Farmers’ Forum in Ottawa, which was a mix of inspiration and business management. The program’s final event was the International Farm Management Congress this past July in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The program has been very rewarding for Norquay. “Although every conference I’ve gone to has been packed with awesome information, I would say the peer network [of the 10 program participants] is top of mind for good things to come from the program. Every time we go to one of these conferences, we get together and talk about our farms, the challenges we’re facing and how we’re working through them, and different things we have learned, whether it is business management, succession planning, crop production.”

And the program has been key to starting transition conversations between Norquay and his father-in-law. “I have been helping on the farm for five or six years, and then I started working on the farm full-time a year and a half ago. But my father-in-law and I hadn’t really talked much about it. It was, ‘Well, okay, Kyle is coming back to work on the farm, and that obviously means something,’ but the conversations were always very vague,” he says.

“The transition workshop was the biggest thing to start some solid conversations between us. But going to the events about farm business management helped me feel a little bit more qualified to have some of the conversations. The program has given us the tools to get where we want to go.”

Norquay has a simple but essential piece of advice on transition planning for other young farmers: start the conversation.

“As soon as my father-in-law and I started talking about it, the reaction was, ‘It’s great that you’re showing interest.’ And it took off from there. So it was very unnecessary stress for me to be humming and hawing about what should I do, what should I say, is this too early, am I going to come off as an entitled little jerk?” His other suggestion is to tap the resources available to learn about farm transition planning.

When Hannah Konschuh first heard about the Successor Development Program, she was immediately interested. “The program looked like it was designed specifically for a young farmer like me at this stage of the game,” she says. “The program’s focus on farm management and the succession planning process are key interests for me. My family and I had been talking about needing to access succession planning resources and it seemed like a perfect opportunity. Of course, another key aspect was that all expenses to attend the events were paid; for a young farmer that’s a major thing!”

Konschuh has a master’s degree and is an agrologist in training. About a year ago, she made the commitment to dedicate herself to the farm so she let go of her off-farm job with the Alberta Wheat Commission. She farms with her husband and her parents. The farm, which was started by her parents, is a dryland grain operation growing cereals, oilseeds and pulses, and is located about an hour and a half east of Calgary.

For Konschuh, the successor development program’s most important benefit is her new peer network of 10 keen young farmers. “They threw the 10 of us together at the first event, and we were an instant bunch of friends. Being able to meet other young farmers from across Canada was great. I think we’ll continue to be connected and resources for each other after the program is over.”