TOP CROP MANAGER

ACTIVE SOIL MICROBES

Winter soil management can prevent N loss PG. 8

PLANT GROWTH REGULATORS FOR WHEAT

When to consider applying a PGR to your crop

PG. 10

FARMING IN NATURE’S IMAGE

The benefits of working with nature

PG. 26

Winter soil management can prevent N loss PG. 8

When to consider applying a PGR to your crop

PG. 10

The benefits of working with nature

PG. 26

5 | Colour a key quality of export wheat researchers study the effects of mildew on wheat colour.

By Julienne

Isaacs

| New tests measure soil structure Tests are being run in soil labs, for health and structure as well as chemistry. By John Dietz

Soil microbes remain active in winter By Helen Lammers-Helps

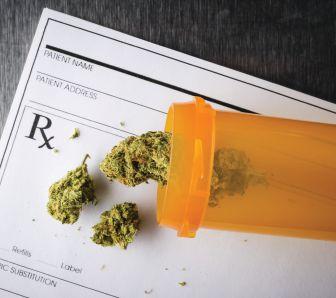

24 | The highs and lows of growing pot Spreading legalization of medical cannabis leads producers to consider growing it.

By Jonathan Hiltz

Barcoding for better weed ID By Amy Petherick 28 Timing for winter wheat herbicides By John Dietz 10 plant growth regulators for wheat By Carolyn King

Wheat class modernization By Julienne Isaacs PESTS AND DISEASES

18 Biofungicide for Fusarium head blight of wheat made in Canada By Trudy Kelly Forsythe

Farming in nature’s image By Amy Petherick

Serial learning

Lianne Appleby, Associate Editor

LIANNE APPLEBY | ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Irecently read an online article, proclaiming that the definition of insanity is one of the most over-used clichés of all time. You know – that one about doing the same thing over and over again but expecting a different result. Some attribute it to einstein, but said article can find no such attribution.

It doesn’t matter anyway.

The point is, somewhere along the line, someone must have said it and we’ve all heard it (funnily enough) over and over. personally, I’m a fence sitter. In perfect conditions, with constant controls, it is rather silly to expect different outcomes from doing the same thing again and again. But, in life, very rarely are conditions controlled to the point where doing something the same way each time results in the same outcome. Farming would literally be a breeze if producers did things the same way each year and actually got the same results. But we have a variety of factors to thank for such not being the case, not least Mother nature.

and again this year, she’s challenged us with environmental conditions leading to a multitude of problems in the field. Slightly cooler than normal July temperatures were ideal for soybean aphid development; wet, rainy weather in most parts of the province made haying a challenge; and particularly wet conditions across many regions created field work challenges such as fungicide application, weed control in soybeans and sidedress nitrogen application in corn.

The best arsenal a producer has at his disposal in order to adjust with volatile conditions is that of continuing education. as technologies change, it’s important to know what’s out there to help keep your bottom line in the black – and as luck would have it, there are plenty of forums for you to stay up to date.

I was impressed with the numbers of farmers I saw out and about this summer –whether at the South West Crop Diagnostic Day, the Farm Smart expo or even at Bayer CropScience’s Dead Weeds Tour. These events – and others like them throughout the year – provide the perfect chance for growers to rub shoulders with on-the-ground researchers and representatives to learn hands-on about diseases, pests, available technologies and products.

The time has never been better for producers to keep abreast of what’s going on. There are countless websites now dedicated to providing field crop information, whether they are government-maintained, media-owned or simply a betterment-of-the-industry site hosted by a corporation. our own agannex.com is dedicated to providing news and research updates and there’s also a handy sign-up area for receiving e-blasts from this publication and those of our sister magazines.

If you’re more mobile savvy, there are hundreds of apps available to help growers make appropriate choices when purchasing equipment, seed, chemicals and even managing finances. The possibilities for learning are literally endless. as one corn grower I chatted with in July said (with a wink), “I may be getting up there in age, but it’s a sad day when I learn not a thing. I like to think of myself as a ‘cereal’ learner.”

and he’s right. Whatever stage of life you’re at, in crop production there’s always more research yielding new or more reliable results. We are lucky to have a transparent system where researchers make their study results readily available and are willing to share their insights. If you’re not taking advantage of these events and learning portals, it’s time to make time.

1717-452X

CIrCuLAtION email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530,

Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, march, April, september, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada - 2 issues - Spring and Summer 1 Year - $16.00 CDN plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industryrelated groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2015 Annex publishing & printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication. topcropmanager.com

by Julienne Isaacs

Canadian Western red Winter (CWrW) wheat and Canadian Western red Spring (CWrS) wheat have traditionally been prized by international customers for their protein content, gluten strength and bright white flour colour. But last year’s Canadian wheat crop saw significant downgrades in number one and two classes for a variety of reasons, including hail damage, excess moisture and disease. But the number one cause of poor grain quality in 2014 was mildew, and international customers noticed.

Mildew is a fungal condition that develops in unthreshed grains in excessively damp weather, and the result is a greying seed coat that, after processing, darkens the colour of the flour. asian markets, which account for a vast portion of Canada’s export wheat sales, prize bright white flour.

according to Dave Hatcher, program manager for analytical services and asian end products at the Canadian grain Commission (CgC), mildew tends to grow on the brushes of wheat and the top portion of the kernel, and then works its way into the kernel itself.

“When you are milling wheat, unless you go with very high quality flour, the whole milling process involves scraping the bran away from the endosperm,” he explains.

“as you do this commercially, there are certain yields you require to be economically viable. once you clear 70 per cent you significantly increase the bran, and with that you bring in the mildew, which causes a discoloration,” he says. “So this impacts the miller because in order to avoid discoloration, they have to mill to a lower extraction which affects the bottom line.”

It’s a question of aesthetics, not safety (darkened flour carries no health risk) but in international cuisine, the way food looks is often as important as how it tastes.

at the Winnipeg-based Canadian International grains Institute (Cigi), a team of researchers is devoted to evaluating Canadian grain quality and assessing potential avenues of improvement. Cigi has

ABOVE: Intermediate flour products produced during the various stages of milling are assessed in Cigi’s pilot mill.

its own test kitchens where flour colour is assessed along with other factors that impact the functionality and consistency of flour in a range of bread products.

“Flour colour is important to customers because it can significantly impact the colour of end-products,” explains Yvonne Supeene, head of baking technology for Cigi. “This is especially true of noodles and steam buns, but it can also impact the internal crumb colour of pan breads, making it less appealing by imparting a duller and grey appearance. For noodles and steam buns, flour colour is the primary and first specification required by manufacturers.”

according to elaine Sopiwnyk, Cigi’s director of science and innovation, and Lisa nemeth, technical specialist for winter wheat, colour is very important in bread production, particularly for customers in asia. “But not as important as protein content and quality – in other words, gluten strength – and water absorption. The extraction rate of the flour can also significantly impact the flour colour and therefore the crumb colour.”

Cigi says CWrW wheat is highly regarded for having a very bright white flour colour, making it desirable for the production of noodles and steamed buns. But currently the quantity of CWrW available is limited due to production challenges from 2014-15.

Research-based solutions

according to Joanne Buth, chief executive officer at Cigi, the institute conducts an assessment of the quality of wheat grown in Western Canada every year shortly after harvest. “Cigi conducts a thorough analysis of wheat, flour, semolina and end-product quality, including baking, asian noodle, steamed bun and pasta evaluations, as applicable, by obtaining representative commercial composites of relevant wheat classes and grades,” Buth says.

Based on the results, Cigi’s technical staff develops recommendations for millers and end-product processors to assist them in mitigating the effects of any downgrading.

Buth says Cigi’s analysis of the 2014 wheat crop showed a moderate decrease in flour brightness that resulted in slight decreases in the internal crumb colour of pan bread and asian noodles. “The same trend was also evident for semolina colour and the resulting pasta colour,” she says.

“overall, our results showed that although mildew resulted in the downgrading of wheat in 2014, the effects were manageable

and colour was within acceptable limits for the various end-products.”

CgC is the federal authority for quality, with both Western and eastern grain Standards Committees meeting twice a year, and as such is continuously engaged in studies of grading standards.

“CgC is always re-evaluating the current grain standards in all of our grading factors to ensure they reflect the intrinsic value of the grain,” Hatcher says.

We’re trying to do due diligence so that producers and buyers are getting fair value

Currently, CgC is engaged in a project analyzing a large number of samples that were downgraded for mildew damage.

Because mildew damage is a subjective grading factor, meaning there are no percentage limits set for each grade, the “degree of soundness” is used to visually assess the overall damage of samples under consideration.

“We have multiple samples in each category, and we’re milling them to a constant extraction so we can assess

the flour colours relative to each other. We’re making the flours up to a constant extraction rate,” Hatcher says.

“We’re also working with our mycologist and he’s come up with a new way of quantifying, by molecular biology, the nature of the mildew fungi itself, the two different species involved, and whether there’s a species effect,” he says.

In addition, CgC is engaged in a project evaluating potential mycotoxins produced by mildew.

“I want to stress that we’re constantly reevaluating all grading factors to make sure that the science supports them,” Hatcher says. “This year we have to look at the mildew because it’s such a dominant factor and had a big impact. We’re trying to do due diligence so that producers and buyers are getting fair value.”

Hatcher says CgC is beginning its second year of this study, but more work is necessary.

“The environment plays such a dominant role that it is wise to ensure you have at least two to three years of data before you make changes to any system that could have significant economic impact for growers or buyers,” he says.

Changes in management practices needed to prevent loss of nitrogen.

by Helen Lammers-Helps

Research from agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) shows soil microbes remain active at temperatures much lower than previously thought. although biological processes slow down in winter, there is still a significant amount of nitrification and denitrification taking place in the soil, says Martin Chantigny, a researcher with aaFC in Quebec City who has been spearheading research that aims to quantify the amount of nitrogen lost following liquid manure application. nitrification is the key process leading to nitrate leaching into drainage water while denitrification results in greenhouse gas emissions, he explains.

He says researchers were surprised to discover 20 to 70 per cent of total annual nitrogen losses were occurring through leaching and denitrification during the non-growing season. The amount of nitrogen lost varied depending on factors such as temperature and snowfall.

Chantigny says. The challenge is to be able to establish a cover crop following corn and soybeans. However, Chantigny points to a growing number of Quebec producers who have successfully established an inter-row cover crop of rye grass in corn which flourishes once the corn is harvested.

Timing the application of nitrogen more closely to when the growing crop can use it is another approach for reducing nitrogen losses. a spring or in-crop application would result in less nitrogen loss, Chantigny says. as a result of this research, farmers in Quebec may apply no more than a third of the liquid manure to be applied annually in the fall. The remainder must be applied in spring and summer.

...snow cover impacted both the quantity and timing of the release of nitrous oxide

In the past, it was thought that biological processes in the soil were negligible below 5 C, explains Chantigny. However, his research has shown that soil bacteria continue to be active down to soil temperatures as low as -2 C in sandy soils. even more surprising, in clay soils, denitrification didn’t stop until soil temperature dipped to -6 C.

“Microbial processes are slower but it is a long time without a crop growing, five to six months, so there is still time for transformations to occur,” Chantigny says. “This is a problem for the farmer as well as the environment. We want the nitrogen to stay in the soil for the next crop.”

To determine if the effect occurred in other areas of Canada, similar experiments were conducted at several different sites across the country. although the patterns were slightly different, the research showed that overall nitrogen losses were similar regardless of the location.

The next step in the research is to determine management practices that would prevent nitrogen losses. Chantigny is currently studying the effects of manure application timing and nitrification inhibitors. nitrification inhibitors have been used successfully in spring and summer so Chantigny is hopeful they will be effective for fall application but admits it’s too early in his research for him to draw any conclusions.

Cover crops could also be used to capture nitrogen during the non-growing season in annual cropping systems. “If a producer can establish a cover crop, that is probably the best way to collect the residual nitrogen…in the organic matter of the crop,”

Looking to the future, the researchers wanted to determine how climate change would impact the loss of nitrogen during the non-growing season. Climate change models predict there will be less snow cover, which would result in colder soils since snow acts as an insulating blanket, explains Claudia goyer with aaFC in Fredericton, n.B.

goyer set up a trial to compare nitrous oxide emissions under different snow cover conditions. nitrous oxide is a greenhouse gas produced by the denitrifying bacteria in the soil that is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. emissions from the breakdown of manure and fertilizer in the soil are the major sources of nitrous oxide from human activities.

a snow fence was used to capture more snow on one set of plots while snow was removed from the “no snow” plots. natural or “ambient” snowfall made up the third treatment.

as expected, where the researchers removed the snow, the soil was colder. They also found that the amount of snow cover impacted both the quantity and timing of the release of nitrous oxide. In the plots with no snow, there was more nitrous oxide released when soils froze compared to the other plots. There was also another flux of nitrous oxide earlier in the spring compared to the other plots.

These results suggest that in the plots where the snow was removed, the soil was frozen more deeply, which resulted in a release of nutrients from the breaking of soil aggregates, says goyer. This increase in nutrients stimulates the cold-adapted denitrifier bacterial communities, which, in turn, increases nitrous oxide emissions.

This research is continuing to further explore a variety of agricultural practices that could help reduce nutrient losses over the winter.

Dow Seeds may be a new name, but it has the power of Dow AgroSciences firmly behind it. This includes a robust R&D pipeline and leading-edge trait technologies like Herculex, SmartStax and the Enlist Weed Control System. So expect better. Better traits, genetics and performance. We’re behind you all the way.

I work for Dow AgroSciences. I am Dow Seeds. @DowSeedsCA

by Carolyn King

When does it make sense to use a plant growth regulator (pgr) on your wheat crop? Based on what he has learned from his research, wheat expert peter Johnson offers some advice to growers.

“We’ve worked with all the growth regulators [for wheat] that I’m aware of,” says Johnson. as the former provincial cereal specialist with the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra), he conducted several pgr trials over the past four or five years.

Most of his research has been with chlormequat chloride (Manipulator, Cycocel extra), including a four-year winter wheat project with field-scale trials at multiple locations in southwestern ontario. as well, he’s done a small plot trial involving engage agro’s Manipulator on spring wheat.

“We’ve also done a little bit of work with ethrel [ethephon, from Bayer CropScience]. It is the cheapest growth regulator, at about $10 per acre. But because of the potential for crop injury when the weather works against you, most growers probably aren’t going to take the risk,” he notes.

“and we’ve done some work with palisade [trinexapac-ethyl], particularly on spring wheat.” This new Syngenta product is not yet registered in Canada, although it is registered in the United States.

Manipulator is the latest pgr on the Canadian market; it is registered for use on spring and winter wheat starting in 2015. “Manipulator is about $14 per acre,” Johnson notes. “I’m quite excited to have another reasonably priced tool in the toolbox when needed.”

However, he cautions, “right now, Manipulator is not registered in the U.S., so there is some concern around wheat treated with Manipulator being exported to the U.S.” although chlormequat chloride is registered for use in many wheat-growing countries, the U.S. hasn’t yet established a maximum residue limit (MrL) for it, so wheat treated with it cannot be exported to the U.S. at present. growers are advised to check with their grain buyer before applying

ABOVE: A PGR application can cause shorter plants with thicker stems that are better able to resist lodging.

Manipulator, or any other product, to their crop. engage agro is working to get the U.S. MrL established as soon as possible.

The MrL issue also affects wheat treated with Cycocel extra. This BaSF product has been available in Canada for a while, but it seems to be targeted for horticultural uses (which are also on its label).

Johnson explains, “Cycocel is still registered for winter wheat but only for specific varieties - and none of the current wheat varieties are listed on the label. Cycocel is being used for things like shortening plants in the flower industry, and it is priced for the horticultural market, at around $40 an acre, so it is priced out of the cereal market.”

Expected results, surprising results

a pgr application can cause various responses in wheat crops such as shorter plants (internodes), thicker stems, thicker stem cell walls, less lodging and/or higher yields. The response depends on factors like the particular wheat variety, the pgr type, rate and timing, and the weather conditions.

“people think growth regulators really shorten the crop, but that only happens if something went wrong at application, like the weather got too cold. Typically we’re looking for about a twoto three-inch shorter plant,” he says. “growth regulators thicken the cell walls in the stem so the plant has better standability. Sometimes you don’t get any shortening whatsoever, but you can still feel the stiffness in the treated crop when you push the wheat plants with your arm.”

Johnson has noticed that pgrs clearly affect spring wheat more than winter wheat, with more dramatic height reductions in spring wheat. “That may be because with spring wheat we are more likely to be able to hit growth stage 30-31, when we can get maximum impact.”

When lodging occurred in Johnson’s trials, a pgr application significantly reduced lodging, but didn’t necessarily completely eliminate it. “In a really lodging-prone situation with a variety that doesn’t stand very well, that you planted early and too thick, and that you whacked with nitrogen, then one application of a growth regulator is not enough. In our research, we’ve only worked with one application. However, in europe in a situation like that, they would definitely use two applications of a growth regulator. In Canada, we haven’t gone to that extent,” Johnson says.

He notes, “one of the surprises out of some of this research is that even when we go into what we think is a lodging-prone field and we put on more nitrogen than we think we should, often times the wheat will still stand just fine. It really depends on the field and the weather and a whole bunch of other factors.”

Johnson’s trials indicate pgrs tend to boost yields. although the yield increases were usually larger when lodging affected the untreated plots, “even when the untreated plots didn’t lodge, the growth regulator treatments averaged around a two-bushel increase. We didn’t see that yield increase in every field, every time. But averaged across all the trials, there is a small but statistically significant yield increase.”

He attributes the yield increase to a couple of factors.

“If you apply it right at growth stage 30-31 [as stem elongation starts and the first node appears], one of the growth regulator’s impacts, particularly chlormequat chloride, is to temporarily remove the apical dominance of the plant. So a few more tillers establish what might not have established otherwise, and also the tillers even up so there is less difference in maturity between the main stem and the tillers. However, it’s rare that we can hit that timing on winter wheat because most of the winter wheat gets past us before we can apply the growth regulator.”

another factor could be the pgr’s effect on the stomates, which are the pores on leaves that allow carbon dioxide to enter, and oxygen and water vapour to escape. “Studies by other researchers show chlormequat chloride keeps the stomates open longer when the plant is under some stress. That allows the plant to have carbon dioxide exchange for a longer period and to continue to

photosynthesize under a mild stress when otherwise the plant may not have continued to photosynthesize,” Johnson explains.

“That runs some risk if the crop gets into a stress period during grain fill. When you have higher tiller counts or a bigger plant through more photosynthesis and the stomates are staying open longer and the crop goes under severe drought stress when those stomates need to close or you don’t want those extra tillers, then you could actually see a yield depression from the growth regulator. That has been documented in other places in the world.”

He adds, “We have rarely seen a yield depression [in our work], I think because we rarely get into real drought stress in the grain-fill period. But it is a possibility that people need to be aware of.”

as other studies have found, Johnson’s work shows that response to a pgr depends in part on the crop variety. This was demonstrated clearly in a 2014 trial that he conducted with C&M Seeds, Syngenta and agriculture and agri-Food Canada at ottawa to compare Manipulator and palisade on spring wheat varieties.

He outlines the kinds of differences seen in the trial: “When Variety a is sprayed with Manipulator, it becomes a little shorter, the way we would hope, and when it’s sprayed with palisade, it’s 50 per cent shorter, and when it’s sprayed with a tank mix of the two, the plants barely get above your knee.

In Variety B, Manipulator shortens it a lot and palisade doesn’t shorten it as much, and the two together again really beat it up. and Variety C isn’t shortened much at all by either growth regulator. We don’t yet know why one variety reacts one way and another variety reacts a different way.”

Johnson has found Manipulator and palisade to be “pretty safe from a crop injury standpoint,” but when he tried using a tank mix of the two products at full rates he found there could be serious crop injury. regarding tank mixes with herbicides and fungicides, he says, “We’ve done lots of field-scale trials where we have tank mixed the herbicide, the fungicide and the growth regulator. But that is a trade-off scenario. To accurately time the growth regulator to remove that apical dominance and maybe get a few more tillers, you’d want to apply it between optimum weed control timing and optimum fungicide timing.”

He adds, “Under adverse weather conditions, you will see more crop injury with the more things you put in the tank.”

When to consider a PGR

according to Johnson, a pgr can be a useful tool in high-input situations where the wheat crop has high yield potential and a high risk of lodging. Factors that increase the risk of lodging include: early planting; a high seeding rate; a variety with poor standability; high nitrogen rates, especially if all or most of the nitrogen is applied in one application and available during stem elongation; and warm, wet conditions during stem elongation.

“There are lots of ways that a grower can manage lodging without using a growth regulator. You want to employ

If you really want to push a crop, then using a growth regulator has a fit

all those things as well – managing your nitrogen rates and time of application, picking the right variety, and so on. It is a whole management package that you put together,” he notes.

“But at the end of the day, if you really want to push a crop that is on good ground and was planted early and you’re worried

about lodging, then using a growth regulator has a fit.”

Johnson is not doing any pgr trials in 2015 because of the current export issue with chlormequat chloride. These days, his challenge on the growth regulator front is to help growers get better at predicting lodging so they’ll be able to make better decisions about pgr applications.

He says, “For example, 2015 is not going to be a lodging year in ontario. The wheat is incredibly short because of the dry conditions [in May] and somewhat because of some cold injury from the winter. also, during the stem elongation phase, we had cool night temperatures, almost always around 10 C or lower. When you get those cool nights, the wheat plant doesn’t respire as much, so it doesn’t burn up the photosynthate made during the day and it has more carbohydrate to make strong stems.

as a result in 2015, most ontario wheat growers probably don’t need a growth regulator to help the crop stand and facilitate harvest. That’s not to say that there won’t be some lodging out there, but it’s not a lodging year.”

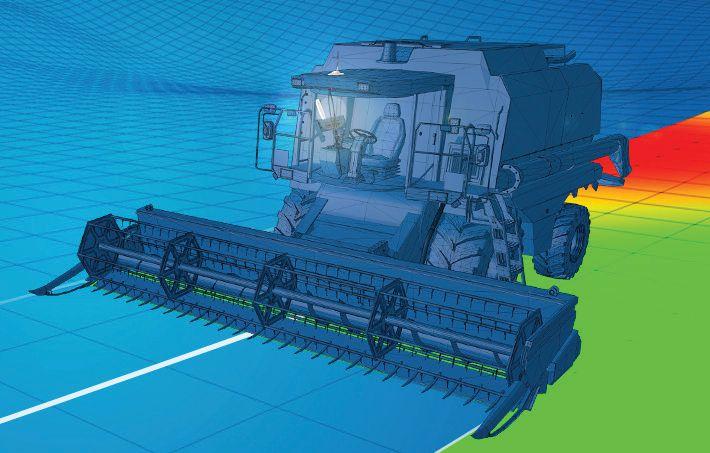

DISCOVER COMFORT, PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY FROM THE WORLD’S MOST POWERFUL COMBINE.

COMFORT. All-new Harvest Suite™ Ultra cab with 68 ft2 glass and acres of space for unsurpassed visibility and operating ergonomy. Smooth ride SmartTrax™ system with Terraglide™ suspension. PRODUCTIVITY. Largest ever 410 bu. grain tank, 4 bu./sec unloading speed, 34 ft. pivoting auger for greater unloading flexibility.

QUALITY. Unique Twin Rotor™ threshing system, 10% higher capacity with Twin Pitch technology, crop accelerating Dynamic Feed Roll™ for even higher throughput. POWER. Mighty Cursor 16 ECOBlue™ HI-eSCR engines for Tier 4B compliance and 10% fuel savings. Up to 653 hp on the new CR10.90, the world’s most powerful combine.

www.newcr.newholland.com

New

tests are being run in soil labs, for soil health and structure as well as chemistry.

by John Dietz

Remember the names Cornell, Haney, Solvita and the year 2015. If soil testing is foundational to modern farm management practices, it’s time to rethink what we know.

“The concept of testing and using that as a guide for making agronomic decisions with respect to managing soil nutrients goes back to the mid1950s,” says Christoph Kessel, ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra), nutrition program lead for horticulture.

at its simplest, soil testing provides an idea of how much nutrient could be available to a crop during the growing season. From a soil sample, it uses standardized methods to extract nutrients and combinations of nutrients.

achieving that predictable accuracy has taken analysis of thousands of soil test results and yield results over many years. In practice, however, agronomists and farmers know that more than available nutrients are involved in crop performance.

Today, Kessel says, new options for soil testing are available – but not yet accredited by oMaFra. They are a departure from measuring soil chemistry. Basically, they measure soil health and structure, the major and long-neglected components of soil.

“The standard soil tests really haven’t changed much since they were adopted. You could ask a lab to do any new test you want; the challenge is, how to interpret the results,” Kessel says.

ontario’s largest soils lab, a&L Canada Inc., has been distributing the Solvita soil health test since 2012. This spring, it began offering the Haney soil health test. now, a third new test is available. It was developed by Cornell University in new York and is known as the Cornell soil health assessment.

The Solvita test

The USDa now lists the Solvita as a national soil-quality test. Worldwide, 35 labs offer the Solvita. The Solvita measures total microbial respiration in a soil sample. Microbes that are active produce carbon dioxide. The more Co2 that’s emitted, the healthier the soil is seen to be.

“We [have been] a distributor for the Solvita test for about three years now,” says george Lazarovits, research director at a&L Canada. He adds, “perhaps you should

<LEFT: Sampling a Collamer silt loam after many years of intensive cultivation leaves the surface crusted and slaked.

<LEFT: After air drying the Collamer silt loam sample, the crumbs are examined to see the effects of years of intense cultivation.

look at this Solvita number as an indicator that something is going in a certain direction. The test measures potential mineralizable nutrients that are stored by the microorganisms. as a single test, it may not be immediately useful, but over the long run it will indicate if these microbial reserves are increasing or decreasing and that is an indicator of soil health.”

There’s a lot of interest in it, he explains. More often, every year he’s hearing stories about the fertility package “going backwards” after a farmer has relied on standard soil test recommendations for decades. apparently, the soils are suddenly non-responsive to applying more n-p-K (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) fertilizers.

When taken over a certain time period, the Solvita respiration number reveals that soil health is changing. a low respiration rate probably will be improved if products like manure, green manure, compost or other organic matter can be added.

The Haney test is an integrated approach using fertility and biological soil test data, including the Solvita one-day Co2 test. It was developed at the USDa-arS grassland soil and water research laboratory in Temple, Texas by soil scientist rick Haney.

Several measures of biological and nutrient properties come together in the Haney test to produce a soil health number that can vary from one to more than 50. They represent the Solvita 1-day Co2, the water-extractable organic carbon and nitrogen, and carbonnitrogen ratio.

“We started introducing the Haney test from Texas about three months ago [april 2015],” says Lazarovits. “There is now a kind of movement to this test by people who are thinking it will change the way they should measure nutrients available to plants.”

There’s a lot of interest in the Haney test, but whether it’s suited to Central and eastern Canada is an open question for Laura Van eerd, associate professor at the University of guelph, ridgetown Campus.

“We need to evaluate its potential. The Haney test was developed on pastureland in Texas. We are testing its ability to make fertilizer recommendations in ontario, and we’re skeptical at this point,” Van eerd says. “My gut inclination is that, if it can’t pick out differences in n-p-K fertilizer recommendations, then it will be difficult to justify taking it to farm fields.”

However, she adds, the soil health component of the Haney test holds “quite a bit of potential as a useful tool in ontario.”

grain Farmers of ontario is also interested. This spring, they began funding her research with the Haney test. The project will take a minimum of two years.

“We are starting to evaluate corn, soybeans and various grain crop rotations with and without mouldboard plow using long term trials with David Hooker and Bill Deen. We’re very excited about this research and looking forward to the results,” Van eerd says.

The Cornell nutrient analysis Laboratory in Ithaca n.Y. independently developed a soil health assessment over the past six to eight years. It is now available directly from that lab for about $100, and has some proven history in ontario testing by the University of guelph.

The Cornell test has 17 parameters that measure, for example, soil texture, wet aggregate stability, water holding capacity and hardness, plus standard fertility, soil respiration, organic matter, active carbon and soil protein to give one score of soil health; where higher numbers indicate higher soil health.

The University of guelph already has study results on the Cornell test from four long-term sites in ontario, Van eerd says. “We found that the higher scores in the Cornell assessment agreed with our expectations of higher soil health on no-till versus annual plowing with secondary tillage, and for higher soil health with alfalfa and winter wheat in the rotation.

“now, we hope to compare the Haney soil health test with what we know from the Cornell test. They definitely serve the same purpose, but use very different parameters,” Van eerd adds.

Kessel says, “The Cornell soil health test will give you the fertility package, but it also will tie in biological health and the physical properties of the soil because all three components go together to make it healthy.”

physical components say something about how strong the structure is, whether it holds together under stress. It may be too loose, or too tight, or too hard, for instance. “If the structure is really poor, the roots may not function properly so that they have limited or reduced uptake of nutrients,” Kessel says. “If the physical conditions are poor, so that you have poor root development, it doesn’t matter how many nutrients you provide. The plants just won’t pick those up, even though according to the traditional soil nutrient test, there’s an adequate amount.”

In general, Kessel adds, these new tests should interest the organic sector as well as conventional farms that are trying to monitor and manage soil health. “Both in organic and conventional farming, producers today are trying to monitor and manage biological aspects of their soils, using crop rotations to manage and maximize their soil nutrients.”

Speaking directly for the Cornell team that developed the test, extension associate robert Schindelbeck says, “Coming up with a strategy for what works on your farm is up to you.” The Cornell assessment provides information on whether soil is functioning well or poorly, for the characteristics of soil physical structure (tilth), soil biological activity or soil nutrient levels.

“But rather than recommend soil management practices, we provide linkages to management solutions that are known to positively affect soils with these issues,” Schindelbeck says.

Designation of 2015 as International Year of the Soil was picked up by the USDa’s national resources Conservation Ser-

vice (nrCS) as an opportunity to promote adoption of soil health testing. It has had a big impact on the three tests. Schindelbeck says, “We’re swamped. It’s our biggest year ever. We had a thousand samples before the end of June. For our university-based lab, that’s huge.”

He adds, “I can’t say enough about soil health. really, it’s soil ecology. Folks are now recognizing that soil is more than just a repository for the standard n-p-K nutrients. Soil is a living, functioning organism that stores water and where many transformations of life occur to make nutrients available through recycling, thereby feeding life-promoting substances to the plants and organisms nearby. as one life form is dying, another organism niche opens to take the nourishment.

“a wide suite of soil analyses in a soil health test helps guide us to the real goal of the testing – to understand how the soil is functioning under current management so that we can adjust toward improved management.”

With decades of soil testing experience, Lazarovits says this is an exciting time but more will come.

In the long run, he says, the new tests will need linkage to specific crops and specific recommendations. plants need, like people, specific diets to thrive, to be healthy and reproductive.

“We should be doing almost crop-specific testing. We do that now at a&L by giving you low, medium and high response categories for the crop you plan to grow. I think that’s going to have to be an important component of all these new tests,” he says.

The other changing aspect of soil testing is instrumentation. It’s becoming better, smaller and more accurate.

“It may be possible in less than 10 years to do your own soil testing with an instrument you carry in a shirt pocket,” says the a&L research director.

To gain a better understanding of herbicide resistance issues across Canada and around the world.

Our goal is to ensure participants walk away with a clear understanding on specific actions they can take to help minimize the devastating impact of herbicide resistance on agricultural productivity in Canada.

Some topics that will be discusSed are:

• A global overview of herbicide resistance

• State of weed resistance in Western Canada and future outlook

• Managing herbicide resistant wild oat on the Prairies

• Distribution and control of glyphosate-resistant weeds in Ontario

• The role of pre-emergent herbicides, and tank-mixes and integrated weed management

• Implementing harvest weed seed control (HWSC) methods in Canada

A strain of C. rosea isolated from a pea plant in 1994 may soon help small grain cereal producers fight Fusarium head blight.

by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

When allen Xue from agriculture and agri-Food Canada’s eastern Cereal and oilseed research Centre (aaFC-eCorC) in ottawa isolated the fungal strain Clonostachys rosea from a pea plant in 1994, he began the process of developing the first biofungicide for controlling Fusarium head blight.

reducing grain yield and quality, as well as posing a risk to animal health and the safety of human food (since infected kernels are contaminated with a toxic substance called deoxynivalenol), Fusarium head blight (FHB) has become an increasing problem for small grain cereal producers. It is particularly epidemic in e astern and Western Canada during years when wet weather coincides with wheat during its flowering stage, and is estimated to cost Canada’s agriculture sector over $100 million annually.

Crop rotation and tillage to reduce the risk have had limited success. The use of chemical fungicides is the most effective solution to date, but is costly and has environmental concerns attached to it. Creating genetically resistant cultivars is one of the most practical and environmentally safe measures to control FHB, but while considerable research has been done in this field, complete resistance has proven elusive.

as a result, researchers began to look for a more environmentally acceptable alternative to the use of chemical treatments, namely the biological control of plant pathogens by microorganisms. It was during such research to test a range of potential biocontrol agents to see their impact on soil- and seed-borne pathogens of cereal crops, including FHB, that Xue identified the C. rosea strain aCM941.

“It showed activity as a foliar spray,” Xue says. “But its activity in suppressing G. zeae in crop residues really caught our attention because of how this might be exploited against Fusarium head blight.”

From 2005 to 2012, Xue led two collaborative projects. These included a series of greenhouse experiments and field trials on CLo -1, an experimental wettable powder formulation of aCM941.

To use CLo -1 in diverse environments in Canada, Xue collaborated with Jeannie gilbert from aaFC’s Cereal research Centre in Winnipeg, Yves Dion and Sylvie roux from the Centre de re -

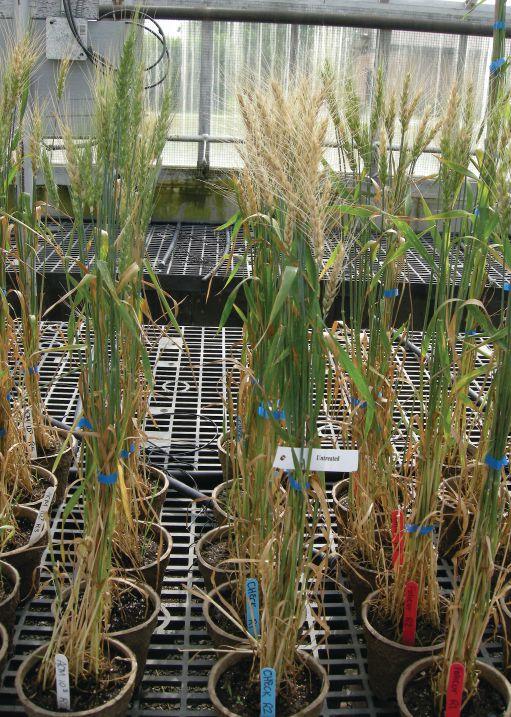

The effect of concentrations on the efficacy of CL0-1, a wettable powder formulation of ACM941 (C.rosea) in controlling Fusarium head blight. Plants here are shown 14 days after inoculation and treatments, in greenhouse trials in 2009.

cherche sur les grains in Quebec, and Harvey Voldeng, george Fedak and Marc Savard from aaFC-eCorC.

“our research demonstrated that at concentrations above 106 cfu mL-1, the bio-fungicide provided consistent and significant effects, with disease suppression generally equivalent to that achieved with the fungicide terbuconazole when applied as a fo -

liar spray,” Xue says. “effects were most pronounced in combination with moderately resistant cultivars.”

He adds that when applied to crop residues, CLo -1 was more effective than the fungicide at reducing the production of perithecia, the pathogen fruiting bodies that form in crop residues and produce ascospores. These are the initial source of disease inoculum and responsible for generating the epidemics of FHB.

“The impact was achieved whether it was applied before or after the substrate was infected with Fusarium head blight, and in field trials applied in either autumn or spring,” Xue says. He explains that when it was applied to wheat residues in the field in spring, it delayed the appearance of perithecia by seven to 10 days and reduced quantities of ascospores.

Having patented aCM941 in 1999, aaFC signed a 10-year licensing agreement with the Canadian bio-pesticide company, adjuvants plus Inc., in august 2014, to develop the technology and gain regulatory approval. With a provisional two-year window to bring it to market, adjuvants plus developed Donguard, which is

expected to be commercially available in Canada in 2016. It is exciting news because CL o -1 will provide an extra tool for producers to use in an integrated FHB management strategy that will reduce initial inoculum load and the risks of epidemics. It should also work in tandem with the most resistant wheat cultivars currently available, reducing the need for fungicide applications against FHB for both conventional and organic producers.

representing a major breakthrough in FHB management in Canada and in the world, this is hopefully just the first bio-fungicide for controlling FHB. Xue has already worked collaboratively with Cornell University’s bio-fungicide expert, gary Harman, to develop and evaluate new and improved commercial formulations of aCM941.

researchers also continue to look into more effective and efficient ways to apply the bio-fungicide as well as its potential with other economically important diseases of field, horticultural and vegetable crops.

today means carefully considering every input – including advice. Our agriculture banking specialists know the challenges and rewards of working the land.

to one of our agriculture banking specialists today.

by amy petherick

If research and development stays on track, farmers could experience barcoding when it comes to spraying for weeds. researchers at the University of guelph have been working hard for the last 12 years to generate “Barcodes of Life” and recently, they’ve turned their attention to weed species. It’s called the Weed Barcode of Life project (Weed-BoL) and Steven newmaster is one of the lead researchers working on the project.

“My expertise is plant taxonomy and weeds are one of the toughest groups,” he explains. “We built a Dna sequence library for all the weeds in ontario so we can have all the genetic variability, and we are very confident that if you have some unknown material, then match it to our library, you’ll get a good answer.”

The original idea for developing Dna barcoding systems was initially proposed by newmaster’s colleague, paul Hebert, back in 2003. His work was originally based on finding a short gene sequence at one standard location in the genome to identify different species but unfortunately that method doesn’t work on land plants. newmaster’s research revealed that the chance of finding another equally accurate gene sequence at one location in the relatively more complicated genomes of plants would be slim. So his team worked to develop a system that relies on one standard gene sequence location combined with a secondary region to produce a barcode for plants. In his research paper, newmaster writes that traditional taxonomic practices are no longer capable of meeting growing needs for accurate and accessible information with millions of species still unknown and unnamed by the Linnaean system.

Closer to home, Mike Cowbrough, ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra) weed specialist, supports newmaster’s assessment with his own example of how this impacts the agriculture industry.

“everyone’s on the lookout for palmer amaranth and there’s been a lot of false positives,” he says. The genetic library, now maintained at the university, makes it possible to analyze suspicious plants conclusively using a quick Dna test, but Cowbrough thinks it would be great to have it right in the field for these cases someday.

newmaster says what Cowbrough is envisioning is actually very attainable. although they’ve had difficulty securing the funding to develop these tools, he says the machine they’re currently using to test samples could be made into a jet printer-sized version, costing perhaps $10,000, which could be centrally located for farmers to use at experimental farms or grain facilities. He says it could be built in the next five years, and a sample run

on the machine would cost farmers maybe a dollar rather than the $30 it costs to submit samples to the university right now. newmaster says the next step after that would be to design probes that worked as a cellphone attachment or even directly on field equipment, but that might be 10 years in the making. probe development will also depend on the adoption and popularity of current ID services. If they find hay producers make the most use of sampling to provide quality assurance to customers or test

Updated checks and new wheat class intended to provide long-term benefits to producers.

by Julienne Isaacs

In February of this year, the Canadian grain Commission (CgC) issued a proposal to modernize Canada’s wheat class system, which aims to revise the parameters of both the Canadian Western red Spring (CWrS) and Canadian prairie Spring red (CpSr) classes.

The proposal came on the heels of 2014’s downgraded wheat and complaints from Canada’s international customers regarding gluten strength and quality. It sets out to revise the parameters of both the CWrS and CpSr classes “to protect…quality and consistency and ensure new varieties meet requirements for milling performance, dough strength, protein quantity, and end product quality.”

In addition, it proposed developing a new Western Canada milling wheat class to address changing customer requirements.

Following the proposal’s release, the prairie recommending Committee for Wheat, rye and Triticale (prCWrT) changed the check varieties for CWrS and CpSr classes. For CWrS, the committee proposed glenn as the upper limit for gluten strength and Carberry as the lower limit check varieties for the Central and Western trials. For CpSr, the committee proposed glenn as the upper limit for gluten strength and pT772 as the lower limit check varieties for the parkland trials.

“The changes are all resulting from feedback from overseas customers, particularly with regard to wheat gluten strength –that it was too low,” says Daryl Beswitherick, program manager for Quality assurance Standards and reinspection at CgC. “So we’re trying to meet our end-use customers’ needs and strengthen the CWrS and CpSr classes by changing the checks that are used by the prairie recommending Committee for Wheat, rye and Triticale.”

prior to the proposed changes, a large percentile of western Canadian producers’ wheat fields were seeded to Harvest, Lillian and Unity, Beswitherick says. “These three varieties have lower gluten

strength, and when you get that much of your wheat below the level that our end-use customers want, it really begins to impact their end-use functionality,” he explains. “We have lost market share.”

If the proposed changes take effect, Harvest, Lillian and Unity will enter the new milling wheat class, and command a slightly lower price globally. These three varieties have proven attractive to growers for their good protein levels and agronomic performance, and Lillian and Unity are sawfly resistant varieties.

But Beswitherick says growers are already shifting away from these varieties. “In 2012, Harvest, Lilian and Unity made up 33 per cent of Western Canada’s wheat acres. In 2013, that figure went down to 27 per cent, and in 2014 it was 22 per cent,” he says.

This august, an interim wheat class was initiated as a stopgap measure while CgC determines whether the proposed new milling wheat class will be necessary.

During February’s variety registration meetings, three varietiesFaller, prosper and elgin-nD - received interim registration.

“We know that Faller and prosper are widely grown in Western Canada already as unregistered varieties, so the reason we need an interim class is so that those varieties will have a place in the market. If producers are delivering into a primary elevator they can then buy it accordingly as a registered variety, not an unregistered variety,” Beswitherick explains.

The CgC’s proposed new milling class has generally been met with approval from industry representatives, but some questions need to be addressed. according to Joanne Buth, chief executive officer at the Canadian International grains Institute (Cigi), while CgC’s proposal for a new milling class would enable reg-

ABOVE: In February of this year, the Canadian Grain Commission (CGC) issued a proposal to modernize Canada’s wheat class system.

istration of varieties that don’t fit into the other existing milling wheat classes, some of these varieties already fall under the Canada Western general purpose (CWgp) class. “Cigi is unsure who the proposed end-use customers of this wheat class are, and has suggested that other options for these wheat varieties be considered such as specialty contracts,” Buth says. “The changes need to be in the best interests of both end-use customers and growers.

But Buth says that overall, the measures are necessary for the long-term health of Canada’s grain industry.

“one of the drivers behind the CgC proposal is comments from customers regarding declining gluten strength and lower overall baking performance in CWrS over the past few years,” she says. “Tightening the quality requirements would help ensure varieties registered into the CWrS class meet the customer quality expectations of this class.”

Ultimately, Buth and Beswitherick agree the impact on farmers will be positive, because a reliable, high-quality product is key to strong exports.

“It will ensure the CWrS quality customers find so appealing is protected, branded and marketed accordingly,” Buth says. “This should result in our ability to maintain markets and potentially higher prices and more shipping opportunities for CWrS.

“Farmers are proud of the product they produce and they want customers to be happy with it as well. They will welcome the opportunity to produce a high yielding wheat, assuming there is a good market and reasonable price,” she adds.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 20

for fillers in uncertified seed purchases or ensure a pasture is free of noxious weeds, they’ll focus on developing technologies for these purposes. But if farmers start testing the wheat seed they’re overwintering or elevators want to check how clean canola samples really are, then they’ll focus on these markets instead. newmaster says they’ve already assumed farmers will want quantitative estimates from these samples, not just the current listing of Dna material found. Cowbrough says developing accurate procedures for this is a process in itself.

The other technology Cowbrough thinks farmers will also be interested in is identifying resistant weeds. Thanks to work by Francois Tardif, he says they now know how to identify the genetic mutation that lends weeds resistance to group 2 herbicides but glyphosate resistance hasn’t been linked to any amino acid sequences yet. Cowbrough says it shouldn’t be long before they know how to develop probe technology to identify this too. newmaster says he’s also working on this area with a group of researchers based in australia who are very interested in Dna barcoding technology.

“as we capture the data and start to identify glyphosate resistance in species, we also want to be able to map it and have that data available for farmers to see,” he says. “I’m hoping there will be a desire to share data that way, so we can alert farmers.”

Gauge yield across the eld to make better management decisions with our time tested yield monitoring tools. Your bottom-line will thank you.

Spreading legalization of medical cannabis leads producers to consider growing it.

by Jonathan Hiltz

With the legalization of medical cannabis in 23 states in the U.S. and across Canada as well as recreational sales of the drug in Colorado and Washington, many believe that the time is now to get into the pot business, namely cultivation and sales.

In Canada, there are currently 25 authorized licensed producers of medical marijuana (recreational forms of the drug are not yet a reality). Health Canada has made it challenging but not impossible to get involved, but the amount of profit one can make varies and that information can be found by looking up the licensed producers who are publicly traded.

The amount of marijuana that one is allowed to produce depends on the level of security that is set up at the facility. There are various security levels based on how much medical marijuana is going to be stored. although there is no limit to the amount of plant numbers, Health Canada measures the correct amounts based on a monetary value of $10,000 per kilogram.

There are already producers in the business who (for a fee) are willing to help others become licensed. But, before spending the money, it may be beneficial to check out Health Canada’s website on the subject to see if you can (or want to) do it yourself. after that, if it still seems better to leave it to the ones who have already been successful at it there are a number of companies that will help. one of them is greenleaf Medical Clinic and medicalmarijuana.ca, a company based in British Columbia that is committed to helping others get into the industry.

“We have an application into Health Canada to become a licensed producer. as well, medicalmarijuana.ca does consulting for companies looking to get into the medical marijuana space. We help potential producers with their applications into Health Canada,” says Ceo Fonda Betts.

Betts is quite familiar with the current application to become a licensed producer. “They really look at security and quality assurance reports, so the applicant needs to have a very qualified quality assurance person who would have a minimum of five years’ experience in good manufacturing practices as well as a university degree in a science background.” For set-up costs that live up to Health Canada standards, one can expect to pay anywhere from $150 - $175 per square foot as long as there is already a building in place. also important to note, the Health Canada application is a lengthy process. Betts recommends that potential producers should allow two to three years to be fully licensed from the initial

Health Canada has made it challenging but not impossible to become a licensed marijuana cultivator and seller.

submission of the application.

all challenges aside, the number of applicants is constantly going up as it is clear that prohibition of this substance is slowly on the outs. If a Liberal or nDp government comes out on top after the next federal election, then things will no doubt open further due to their mandate of regulating marijuana for recreational purposes as well as medical.

We are clearly on the road to a mammoth industry with the potential for growth in almost every sector, so if there was ever a time to get involved and take advantage, it would be now.

American agronomist urges adoption of soil saving practices.

by amy petherick

Hard economics and one man’s experience may be influencing a number of farmers to reconsider their farming practices this growing season, for the benefit of their soils.

ray archuleta, a conservation agronomist with the United States Department of agriculture, is working to convince progressive farmers to adopt some very old philosophies. For those unfamiliar with him, archuleta’s biggest complaint with modern agriculture is that too much focus is put into working against nature and not enough on working with it. So, he’s travelling the continent, asking audiences to name peers or mentors who taught them how to farm “in nature’s image” and even among organic farmers, he says silence is far too common. “When industrial agriculture kicked in, we lost the art and science of how to work with the natural ecosystem,” he laments. The most critical of these ecosystems, he says, is the soil itself.

Soil is alive and too many people in the industry have forgotten that, according to archuleta. “There are textbooks that teach the soil is just a medium - and that’s ridiculous,” he says. “To me,

the most important component of soils is the living part.” arthropods, mesofauna, springtails, and earthworms, these organisms make the dynamic properties of soil ecosystems. protecting their habitat and feeding them will improve soils in just two to five years, when managed correctly he says. any farmer unsure of that can take a shovel to the nearest woodlot, dig up a soil sample, and compare it to another sample from any field. “Your woodlot is going to look magnificent,” he says.

archuleta takes his own demonstrations further by dropping soil samples in a clear container full of water. “Soil that’s been tilled will explode in the water and that means the biotic glues and cementing agents have been oxidized off,” he explains. “good healthy soils should hold together as water rushes in to fill pore spaces.”

reducing tillage, along with diversifying crop rotations, growing diverse cover crop mixes, graze like the Bison, and adding organic components (manure, compost, residue), are five ways

ABOVE: Ray Archuleta challenges producers to work with nature, not against it.

Table 1. are you dirt poor or soil rich?

*based on $11/acre soybeans and $60 bu/acre yield

archuleta says farmers can get soil in the field that’s more like the one found in woodlots. In other words, mimic nature. nature does not till, it is diverse, covered 24/7 with green living plants or armor and nature does not farm without animals. This is “biomimcry” or “ecomimcry” (mimicking biology and ecology).

“I’m a huge advocate of no-till,” he says. “once you understand how elegant and complex soils are, you don’t want to till.”

although he admits the climate and temperature found in ontario is more forgiving than in hotter, drier regions, he insists the disorder caused by even some tillage will stress the natural ecosystem found in the soil. archuleta doesn’t even recommend tillage for incorporating compost or manure into the soil, even though adding organic material is one of his five recommended practices. You must limit surface disturbance. Injection is fine, but disking in manure is destructive to the soil.

“I don’t want manure incorporated into my soil,” he says. “When you incorporate the manure in, you wake up r-strategists – opportunistic bacteria that break up aggregates and release nitrates – you bring weeds to the top, and you think you saved your nitrogen, but you just made it worse.” He advises farmers to let the system take care of itself and work to eliminate things that stress the natural system like tillage, insecticides, herbicides, fungicides and chemical based nitrogen. Trying to farm using “ancient sunlight” (petroleum based inputs – diesel, chemical fertilizer, and pesticides) will make a farmer go broke, archuleta says, but trying to farm only using “new sunlight” can save a lot of money.

“no tillers cut their energy costs by 70 per cent in the first year,” he says. “nobody talks about that.”

But anne Verhallen, soil management specialist with the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra) and her colleague, adam Hayes, actually have been talking to farmers about the cost of tillage (see Table 1). “I think the hard economics of soil health are really important to our growers,” Verhallen says. “Soil health goes beyond the warm and fuzzy.”

Verhallen adds the cost of not having good soil health is something many farmers don’t figure in, but can calculate for themselves. “If you’re having to split your tile because your soil structure has degraded and you’re not getting good internal drainage of water, there’s a cost to that,” she offers as an example. even though the data is pretty clear, Verhallen says archuleta is far more severe in tillage discussions than she and her co-workers are, but she believes archuleta pushes the bar a little higher. “He might take it a little further than we do but he’s still saying the

same things,” she says. The ultimate point is that results are what matter, not excuses. For instance, Verhallen says one common excuse for refusing to adopt no-till is increased slug pressure, a concern for most ontario soil types. “The guys who are trying [no-till] acknowledge there are slugs and feeding, but not enough to knock out the population.” In her opinion, it’s just one of those things farmers need more experience with, but that’s something archuleta can share.

“ray’s got such fervour, such enthusiasm for his topic but he’s also got some really good observations,” Verhallen says. “We brought ray [to ontario] to challenge producers to think outside the box, to think about their soil in a different way.”

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. Commercialized products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from this product can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for this product. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® crops contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for canola contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil and thiamethoxam. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for canola plus Vibrance® is a combination of two separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, thiamethoxam, and sedaxane. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin and ipconazole. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn with Poncho®/VoTivo™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-1582. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Acceleron and Design®, Acceleron®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity®, JumpStart®, RIB Complete and Design®, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb® Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup®, SmartStax and Design®, SmartStax®, Transorb®, VT Double PRO®, and VT Triple PRO® are registered trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC, Used under license. Vibrance® and Fortenza® are registered trademarks of a Syngenta group company. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and Votivo™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

by John Dietz

When it comes to spraying, agronomists say it’s all about timing. a corn-soybean-winter wheat rotation has demonstrated benefit for corn and soybean yields. Winter wheat in the rotation leads to less pressure from weeds, insects and diseases. according to peter Sikkema, University of guelph professor of weed management, a good stand of winter wheat can be extremely competitive. “In many cases, the wheat crop outcompetes the weeds.”

In over eight years of study at ridgetown, researchers discovered what would happen if they didn’t control weeds in plots of corn, soybeans, dry beans, spring cereals and winter wheat. Yield losses were an average of 59 per cent in dry beans, 51 per cent in corn and 37 per cent in soybeans. In spring cereals the loss was 12 per cent. In winter wheat, on average, they documented a yield loss of only three per cent due to weed interference.

a comprehensive timing study was conducted in 2009 and 2010 at the University of guelph. Sikkema and his colleague, Francois Tardif, were advisors to the project. Melody robinson did the field research, using the Zadoks scale for timing of herbicide and fungicide applications, with help from Mike Cowbrough, a weed specialist with the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra).

The team did studies at four locations (elora, exeter, ridgetown and Woodstock) with three herbicides and four fungicides. The mixes were applied early, in cold conditions and late. The herbicides tested were dichlorprop/2,4-D (estaprop), bromoxynil/ MCpa (Buctril M) and pyrasulfotole/bromoxynil (Infinity). The fungicides tested were pyraclostrobin (Headline), tebuconazole (Folicur), trifloxystrobin/propiconazole (Stratego) and azoxystrobin/propiconazole (Quilt).

For the timing study, late applications were applied at Zadoks stages 37 to 39 (flag leaf emergence). early application timing was based on weather conditions, but ranged from Zadoks 14 to 21. as a general rule, injury was visible shortly after application but it did not reduce winter wheat yields. Late-applied tank mixes were more likely to cause injury than early applications. Dichlorprop/2,4-D plus tebuconazole was consistently the most injurious tank mix. It caused dark brown to black foliar flecking where the spray droplets contacted the leaf surface.

according to robinson, using the Zadoks scale “lets you pinpoint the growth stage a lot better. When we get close to heading, Zadoks stages become really important for proper fungicide timing.”

The general recommendation for weed management with

Wheat crops can outcompete weeds and reduce pressure from pests and diseases, according to Peter Sikkema at the University of Guelph. A corn-soybean-winter wheat rotation therefore has demonstrated benefit for corn and soybean yields.

winter wheat still holds true, according to Sikkema. “If you have weeds at such numbers that they are going to cause yield loss, you are much better to spray in late april or early May than to delay the application until weeds are bigger – that just results in greater yield loss. early application is recommended for two reasons: your margin of crop safety is greater. Yield loss due to weed interference is reduced, as it is with any crop.

“The important thing is to get the herbicides on before stem elongation,” he adds. “That gives you a pretty good margin for crop safety. If you have flag emergence, your potential for crop injury increases.”

Nu-Trax™ P+ fertilizer puts you in charge of delivering the nutrition your crops need for a strong start. It features the right blend of phosphorus, zinc and other nutrients essential for early season growth. And because Nu-Trax P+ coats onto your dry fertilizer you are placing, these nutrients close to the rooting zone where young plants can easily access them, when they are needed most.

Take control of your crop’s early season nutrition with Nu-Trax P+ and visit .

Rethink your phos

It’s always flattering when others try to imitate your success. But with nearly 20 years of track leadership under our belts, we’ve picked up a few things the copies missed. Like our exclusive five-axle design. It gives our Steiger ® Quadtrac,® Steiger Rowtrac™ and Magnum™ Rowtrac tractors a smoother ride and more power to the ground with less berming and compaction. Which is one of the advantages of paying your dues, instead of paying homage. Learn more at caseih.com/tracks

BE READY.