TOP CROP MANAGER

SEEDING STRATEGIES

Is late planting winter wheat a smart move?

PG. 6

QUINOA AND AMARANTH

Newoptionsforeastern Ontariofarmers?

PG. 10

KEEPING TRACK

Graintraceabilityis gainingground

PG. 20

Is late planting winter wheat a smart move?

PG. 6

QUINOA AND AMARANTH

Newoptionsforeastern Ontariofarmers?

PG. 10

KEEPING TRACK

Graintraceabilityis gainingground

PG. 20

Simply take the prices your suppliers and buyers offer, or do you make a strategy to maximize your own profit?

Watch your suppliers enter into business alliances with each other while you continue to face the markets alone?

A farm business alliance to maximize your profitability. It just makes sense.

It’s true that no one farmer even the largest among us can significantly affect the supply chain behind him or the value stream beyond the farm gate. It’s also true that most businesses face similar challenges and have developed strategies to improve their market position and expand their market power.

Farmers of North America is the farm business alliance that is your strategic answer to these challenges. FNA is your supply chain strategy, developing methods, options and entire new businesses to drive competition for your input cost dollar, reducing your expenses and maximizing your profits. FNA is your value stream partner, exploring markets and building opportunities to improve farm revenues and even own a stake in the stream itself.

FNA changes the whole farming system, with a tested team and proven performance. What one farmer cannot do alone, together we can achieve in the FNA farm business alliance.

Together we lowered glyphosate prices from $12 and $16 per litre to under $4 today. We saved growers $60 million in 30 days by driving competition for grassy weed control products. We forced the price of ivermectin from as high as $650 for a 5 litre jug in some areas to under $90 for that same jug today. These are only three examples of achievements that have brought farmers hundreds of millions of dollars in additional profit they would not otherwise have realized. All because they made the strategic decision to join the FNA farm business alliance.

And right now, FNA Members are investing in one of the world’s most advanced fertilizer projects, becoming partners in the FNA Fertilizer Limited Partnership. These farmer-partners are executing a strategy to enter the supply chain rather than merely pay for it. You too can move some of your fertilizer costs from the expense column to the revenue column, and secure your own fertilizer supply by actually owning a part of the new plant.

Check out how much has already been achieved in ProjectN, and follow its progress online at www.projectn.ca. Even better, when you join FNA you can also buy your own Seed Capital Unit and be part of building this impressive initiative.

Together we can move big things in big ways. Join 10,000 other producers in the only farm business alliance dedicated to maximizing farm profitability. For about a toonie per day, we guarantee it will be one of the best investments you ever make in your operation.

By Dr. Robert Mikkelsen

Melanie Epp

STEFANIE CROLEY | ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Autumn has rolled in, which means harvest season is upon us. Crops are gathered outside and family and friends gather inside. Winter is on the horizon, but before the cold weather always comes the bountiful harvest that October brings.

At a time of year that is traditionally reserved for celebrating all that we are grateful for, it’s fitting to acknowledge the things that are so often taken for granted. Here at Top Crop Manager, October brings our annual Traits and Stewardship Guide (you can find it in the middle of the magazine). The guide is meant to provide you with resources to help you make decisions for the coming year. But stewardship means protecting and being responsible for something, and agricultural stewardship extends far beyond planning for next year’s crops. Choosing the best seeds, fertilizers and technologies is smart business, and so too is managing natural resources.

Growing up, we lived in a subdivision that relied on town water, and as a child, I didn’t think much about where water came from. When I turned on the tap, water filled my glass, the sink or the tub. It was only upon moving into a house with a cistern that I learned to really appreciate the value of that precious resource.

In a family of six (with four teenagers), long showers were almost non-existent, the dishwasher ran only when filled up to the brim and laundry day depended on how much rain was in the forecast. Of course, a load of potable water could be purchased and delivered when necessary. But when the water guy is too busy to fill up the cistern until next week, and 30-plus people are coming for Christmas dinner tomorrow night, you really don’t know what you have until it’s gone.

On that fateful day, I pondered, as I often do, what would happen in the coming years if we continued our daily routines without considering the effect our actions have on the environment. Could a permanent water shortage become reality? Perhaps it’s an exaggerated thought, but as this issue of Top Crop Manager came together, the question of our environmental future burned deeper in my mind.

Twenty-one years ago, a group of Ontario farm leaders had similar concerns, and decided to take action to help Ontario farmers adopt more environmentally friendly practices with the launch of the Environmental Farm Plan.

You can read more about the program on page 15. In the story, Andrew Graham, director of operations for the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association, says, “There’s incredible pride of ownership.” Graham’s sentiments nicely sum up the meaning of the word steward. Becoming a true steward of the land is something to be proud of, just as an above-average yield is.

Top Crop Manager’s mandate is to provide insights and information on agronomic and industry-related topics with an eye on what’s to come in the next one to three years. Some of the issues and innovations described in the stories in our pages will have an impact for far longer: something our children will appreciate and respect for years to come. Will your decisions have the same result?

MANAGER

OCTOBER 2013, VOL.39, NO.14 EDITOR

jkanters@annexweb.com

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Stefanie Croley

scroley@annexweb.com

EASTERN SALES MANAGER smccabe@annexweb.com GROUP PUBLISHER dkleer@annexweb.com

ACCOUNT COORDINATOR achen@annexweb.com

MEDIA DESIGNER Katerina Maevska PRESIDENT Michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Printed in Canada

CIRCULATION e-mail:subscribe@topcropmanager.com

www.topcropmanager.com

Are we running out?

by Dr. Robert Mikkelsen

Most of the phosphate rock that is mined from the earth goes towards making fertilizer for crop production. Every cell in plants and animals requires phosphorus (P) to sustain itself and there is no substitute for it in nature.

During the past five years, several well-publicized reports have suggested the world’s phosphate rock supply is rapidly dwindling. In response, there has been widespread concern about whether or not we are reaching our “peak” supply of phosphate rock and about possible fertilizer shortages on the horizon.

Recently updated estimates report that the Earth has at least 300 years of known phosphate rock reserves (recoverable using current technology) and 1,400 years of phosphate rock resources (phosphate rock that may be recovered at some time in the future). These numbers fluctuate somewhat, since companies do not intensively explore resources that will be mined far into the future.

Phosphate fertilizer can be a significant cost for crop production and an important mineral for animals. However, from a global perspective, phosphate is considered as a low-price commodity. One recent publication estimated that each person consumes an equivalent of 67 pounds of phosphate rock each year. This results in an annual consumption of about nine pounds of P per person (or 0.4 ounces daily consumption), which is equivalent to 1.7 cents per day.

Phosphorus atoms do not disappear in a chemical sense, but they can be diluted in soil or water to the point where it is not economical to recover. Annual P losses to the sea by erosion and river discharge roughly balance the quantity of P that is mined. This shows that there is substantial room for improvement in efficiency. Implementing appropriate recovery and recycling of P from animal manure, crop residue, food waste and human excreta would be a major step in this direction.

Efforts to improve P efficiency and build soil P concentrations to appropriate levels, serve to enhance its use. In developed countries with a history of adequate P fertilization, the need for high application rates diminishes over time. This contrasts with the situation in many developing countries where low soil P concentrations still require significant fertilizer inputs to overcome crop deficiencies.

Members of the public are encouraged to engage in debate over

Contrary to reports, P is not predicted to run out anytime soon.

important issues, but there is a danger that oversimplification leads to incorrect conclusions. The case of looming P scarcity is an example where insufficient information led to a wrong conclusion. Somehow the incorrect notion still persists that there is an impending shortage of P and that limited fertilizer availability will soon lead to global food insecurity.

There may be a scarcity of many earth minerals some day, but the P supply will not be a concern for hundreds of years. However, responsible stewardship of rock phosphate resources still requires a close examination of improving efficiency throughout the entire process, including mining, fertilizing crops and implementing strategic waste recovery. Working together to improve P management will allow us to conserve this precious resource for future generations.

Dr. Robert Mikkelsen is Western North America Director, International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI). Reprinted with permission from IPNI Plant Nutrition Today, Fall 2013, No. 3.

by Melanie Epp

The results of this year’s Ontario Winter Wheat Performance Trials were released at the end of August – with perfect timing too, as producers are harvesting soybean crops and preparing the ground for winter wheat. Broken down by class (red and white in both soft and hard categories) and variety (29 in total), the trials reveal results for the past five years – both by individual year and cumulatively.

The performance trials are co-ordinated through the Ontario Cereal Crops Committee (OCCC), an organization that acts as the recommending body for cereal variety registration in Ontario. OCCC has representation from all sectors of the industry, including plant breeders, both public and private, as well as Ontario’s Ministry of Agriculture and Food (OMAF), the Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO) and Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association (OSCIA). Eleven voting members conduct the business of the committee. Trials are run on both public and private research sites in Areas 1, 2, 3 and 5. To view the results of the 2013 Ontario Winter Wheat Performance Trials, visit www.gocereals.ca.

Winter wheat considerations

When looking at the list, it might be tempting to choose the highest-yielding varieties and call it a day. Although one variety may yield quite well, it might not be tolerant to fusarium head blight – a disease that has been increasingly problematic for some growers – for example. Other problems could arise too: the variety also may be prone to lodging or winterkill.

“I don’t think anybody should ever pick a variety based only on yield because that will kick you in the butt every time,” says OMAF cereal specialist Peter Johnson. “But each grower is going to use different information from that particular data set, based on their own situation.”

The task of choosing the right variety doesn’t need to be daunting. In fact, with the help of long-term data, it should be fairly easy. “Without this information you’re sort of at the mercy of just trying to either trust your seed guy or doing your own trials or trying to talk to other growers,” says Johnson. “This is really the only unbiased, broad-based information that growers have.”

Data can be tricky to get through. If you’re having trouble deciphering the data, Ellen Sparry, the trial co-ordinator, suggests using the online webinar

<LEFT: The performance trials are run on both public and private research sites, like this one in Palmerston, Ont.

<LEFT: While one winter wheat variety might yield well, it might not be tolerant to fusarium, says OMAF’s Peter Johnson.

BOTTOM: Peter Johnson says key factors to consider when choosing a variety are yield, fusarium, standability and winter survival.

provided on the website’s main page. Once you’ve read the data, use the “Head to Head” tool to compare varieties. To do so, simply choose your area (see the map provided) and the varieties you want to compare. (Results are similar for both areas 1 and 2, so they can be combined as one.) Then select specific characteristics and compare varieties to see which ones performed best based on those limiting factors. Selections can be made for a number of factors, including but not limited to yield, head weight, protein, height and maturity date. You also can see how varieties fared in terms of both lodging and winter survival, or select for disease pressure, including leaf septoria, stem rust, head blight and powdery mildew.

“The real drivers in the decision-making process are yield and fusarium, standability and winter survival,” says Johnson. “It depends on your soil type, but those are the key ones. If it’s highly susceptible to fusarium, I’m really going to be reluctant to grow that variety. If I’m on heavy clay, I don’t worry about lodging. I worry about winter survival. If I’m on a loam soil, I don’t worry as much about winter survival. I worry about lodging.”

Producers should know that choosing newer varieties based on limited data could be risky. “A good example was last year,” says Johnson. “It was the first year for information on the variety 25R40. If you look at it from a yield perspective, it’s an excellent variety. We did not have information on the fusarium reaction of that variety and so we planted a lot of it. 2013 happened to be a bad year for fusarium, and it happens to be a susceptible variety to fusarium. There were a lot of people pretty disappointed with the quality. Anytime you’re looking at a new variety, you have to understand that there’s limited data. The more data, the better.”

Producers also should pay attention to the thousand-kernel weight because that will give them an idea of how much seed per acre they might need.

“You don’t pick a variety based on thousand-kernel weight,” says Johnson, “but once you decide that CM249 or Branson or Wave is the variety for you, then you need to say, ‘Am I going to need a lot of seed per acre because it’s a very big seed? Or am I going to not need as much seed per acre because it’s a very small seed?’ ”

A lot of growers have adopted management practices that include fungicide applications. New this year, the data now shows performance under both sprayed and unsprayed conditions.

“The fungicides used were not the same across the board. It’s really whatever is

recommended for that particular disease, and there are several options for each,” says Sparry. “Since a lot of growers are spraying now, they might be interested in that table.”

“It’s a huge step forward,” Johnson says of the data. “To me, there are some really remarkable changes, in particular, the rankings of the soft white wheat and the hard red wheat varieties. I really think growers need to pay attention. The best thing is to try and pick a variety that does well both treated and untreated.”

Martin Harry, eastern marketing manager for SeCan and past chair for the Ontario Cereal Council, says there’s no doubt when it comes to the value of performance trials. “It’s neutral data,” he says. “And that’s why the farmers value it and the industry values it, because it’s not one way or the other. And you’re comparing all marketable varieties together on the same field.”

According to Harry, performance trials are a valuable tool not only for producers, but also for seed companies. “If they’re not the top performers, then you don’t put them back in. You move on with life and try the next one,” he says.

You spoke. We listened. You want maximum yield potential from every seed: our parallel-link row unit provides accurate seed placement in a range of soil conditions, improved depth control and seed-to-soil contact for even emergence. You need to get more seeding done in a day: quick adjustments, less daily maintenance and higher operating speeds help you cover more ground. You demand versatility: our system takes you from full till to no-till in just a few easy adjustments. Precision Disk™ 500T Single Disk Air Drills from Case IH. Count on us to make every seed count for you. Visit your local dealer or www.caseih.com/500ttcme1013 to learn more.

by Melanie Epp

The Ontario government has been experimenting with growing quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) and amaranth (Amaranths spp.), an ancient grain and a cereal that prefer moderate climates with lower humidity levels. While both “grains” are currently being imported from South America, a dramatic increase in demand, especially at the local level, has some growers considering the new specialty crops as a potential for their farms. Quinoa and amaranth are also both grown in the Canadian Prairies, but are they suitable crops for eastern Ontario farmers? Both a producer and an Ontario new crop specialist think so.

Quinoa, considered to be one of the world’s superfoods, is not only gluten-free, but also high in antioxidants and essential nutrients. As a staple to those on gluten-free diets – a booming market that is projected to grow to $5 billion by 2015 – quinoa is so popular that supply can’t keep up with demand. In fact, on average, the market has grown 40 per cent annually. On top of that, prices for the grain have tripled in the past five to six years. Grain amaranth, although less popular, is sure to see a similar increase in demand, since it is also gluten-free, and high in protein and lysine, the latter of which is an essential amino acid.

In 2011, a partnership made possible by the Sand Plains Community Development Fund allowed the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association, OMAFRA and Campbellvillebased Katan Kitchens an opportunity to do a cultivar assessment of grain amaranth and quinoa. The goal of the assessment was to identify which varieties produced the highest yields under different circumstances. Yield parameters of three cultivars of grain amaranth (A. caudatus, A. cruentus, and A. hypochrondriacus) and five cultivars of quinoa (Brightest Brilliant, Dave#407, Faro, K’coito and Temuco) were evaluated in Norfolk County.

Using a Stanhay Precision Seeding Drill, the grain amaranth field site was planted on June 2, 2011, at a seeding rate of approximately 300,000 seeds per hectare. The quinoa site was planted on June 8, 2011, at a seeding rate of 321,000 seeds per hectare. On both sites, the soil was prepared before hand using 100 kilograms per hectare of nitrogen, but no additional fertilizers were used throughout the growing season.

Between Oct. 7 and Oct. 18, 2011, the quinoa was harvested by hand (plot combines were unavailable). The grain amaranth plots were also harvested by hand on Nov. 3, 2011. Due to weed

Quinoa, one of the world’s superfoods, is gluten-free, and high in antioxidants and essential nutrients.

pressure, and time and labour restraints, only three reps from each trial were analyzed.

The results were mixed for a number of reasons, according to an OMAFRA report provided by new crop specialist Evan Elford. For the cultivars that germinated, mature grain yields were obtained within the growing season, even though planting was delayed due to unfavourable weather conditions. The fact that crops were hand harvested, and the seeds cleaned by hand, likely had a negative impact on yields as well. Weed control was also a

consideration: crops performed well where there was low weed pressure, but yields were lower where weed pressure was higher.

Of the three cultivars of grain amaranth tested, A. cruentus and A. hypochrondriacus both grew upright with a compact panicle seed head. A. caudatus, on the other hand, was not as consistent and its panicle head had long, drooping pedicels. A. hypochrondriacus was the highest-yielding cultivar and the only one that appeared to have a uniform-sized grain. Mean and maximum yields are shown in the table below.

Of the five cultivars of quinoa tested, Dave#407 and K’coito did not germinate. Faro was the first to mature and was harvested on Oct. 7. Brightest Brilliant and Temuco were harvested Oct. 17 and 18. Of the three, Brightest Brilliant and Faro had a larger grain size than Temuco. According to Elford, no statistically significant yield differences were observed, although Brightest Brilliant did obtain a higher yield than the other two cultivars. Elford also observed significant differences in reps, which he attributed to weed pressure, since higher yields were obtained where weed controls had been used on a regular basis beforehand. The table below provides exact numbers for mean and maximum yields of each cultivar.

as well as concerns about processing. While amaranth doesn’t require as much work, quinoa has a natural pesticide on its surface, called saponin, which needs to be washed (or rubbed) off. To make the process more efficient and affordable, they’re looking at the creation of specialized equipment.

One of the biggest challenges they face is developing a market for the grains. “We’re building the value chain right now,” says Draves. “The amaranth is a little tougher, so I’m starting by assessing the competitors and then going from there. There are some big buyers in the U.S. that we’re forming relationships with – those that would prefer to go local.”

Last year, following the 2011 cultivar assessment, the same team chose two of the best varieties of each and ran another set of trials. Set up on five different one-acre sites across the province, each cultivar received randomized treatment with the hopes that statistical data could be collected. The five Ontario sites were located in Campbellville, Peterborough, Staffordville, Matheson and Cobden.

Jamie Draves, producer and owner of Katan Kitchens, is on the Campbellville site. He says that despite extensive weed pressure and drought-like conditions, both grain amaranth and quinoa have done very well on his farm.

“Where some corn crops and some soy crops are getting burnt up, this has still done well,” says Draves. “In future, with the climate extremes we’re seeing, these are crops that may be a little less risky than some of the other crops and more viable that way.”

The partnership is currently working on obtaining more funding so that they can move to the commercial stage as soon as possible. First, though, there are a number of issues that need to be worked on. The problem of weed pressure needs to be addressed,

Quinoa, on the other hand, looks to be a promising market. Internationally, it’s currently grown and exported out of Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru.

“Their capacity to meet demand doesn’t look to be there. Right now, distributors are selling out almost right away,” says Draves. “It makes it very promising as a commercial crop that we’re pretty close to being there and being successful with it. We can probably go commercial and then fine-tune along the way.”

Monsanto is set to launch a new weed control option.

by Donna Fleury

Soybean growers across Canada will soon have access to new soybean technology and new options for weed management. Monsanto recently received full regulatory approval to introduce Genuity Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybeans, a stacked trait with dicamba tolerance. This new trait is part of Monsanto’s Roundup Ready Xtend Crop System, which will combine Genuity Roundup Ready 2 Xtend with glyphosate and dicamba herbicide products.

“The new trait comes with proven yield performance and offers growers a new tool for weed management,” explains Bill Lester, corn and soybean trait marketing lead for Monsanto Canada. “Growers will be able to continue to use glyphosate or any other current soybean product they are finding value in today, but now have the new option to use dicamba where it has a fit to help tackle tough-to-control weeds and also offer some extended residual control.”

Lester says field research data has shown that dicamba can provide residual value under certain conditions, helping to extend the weed control window and protect yield. “This new stacked product will give soybean farmers the option of applying Roundup WeatherMax in conjunction with dicamba, separately or as a tank mix.”

Most corn growers are familiar with dicamba, which provides some early season residual control. However, this new product will be the first opportunity for growers to use this chemistry in soybeans.

“We are introducing a new use pattern for dicamba in a new crop,” notes Lester. “Dicamba provides some short-term residual control but does not hang around in the soil and therefore does not present any cropping restrictions. Growers are very familiar with the weed control expectations that dicamba will be able to bring them.”

Dicamba is a Group 4 chemistry with a strong track record of being able to control a broad spectrum of weeds. This product provides a new weed management solution to help growers utilize an additional mode of action to control weeds and prevent the development of resistant weeds happening on their farms. It also provides a new tool to address difficult weed problems.

“We have a lot of internal research with Monsanto across Canada with this new trait,” explains Lester. “The University of Guelph has also undertaken some specific trials to assess dicamba performance on some glyphosate-resistant weeds in Eastern Canada. Their trial results to date, coupled with our own Monsanto trials, indicated that dicamba will be a great tool to effectively man-

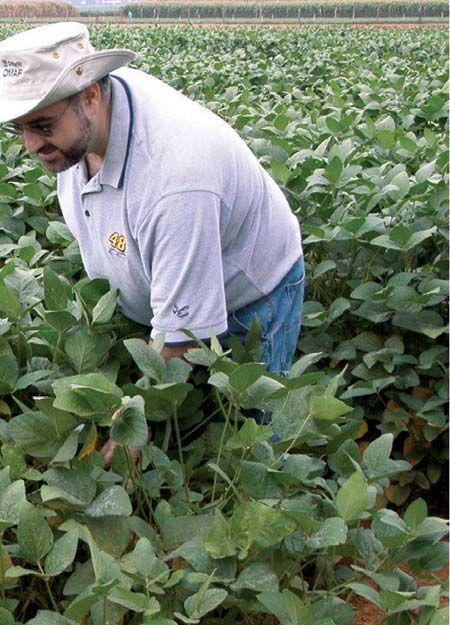

Eastern Canada soybean growers will have the option to use dicamba to help tackle tough-to-control weeds with extended residual control.

age two glyphosate-resistant weeds known in Eastern Canada today, glyphosate-resistant giant ragweed and glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane populations. This is a great new tool for those growers.”

The new dicamba option in soybeans will also offer improved control of other populations of herbicide-resistant weeds, such as those that are resistant to group 2 or group 5 chemistry, which are also known to exist in Canada.

Monsanto expects to have the new Genuity Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybeans commercially available in Canada in 2014, pending key global export market approvals. Lester adds that Monsanto makes a significant effort not to introduce any new trait to the market until those key export markets have provided approvals, so there isn’t any disruption to commodity trading. If all of these approvals come through globally, then Monsanto will be in a position to launch this new trait for the 2014 growing season.

“The first introduction will likely be limited to Eastern Canada, with introduction to Western Canada anticipated as early as 2015,” says Lester. “This is strictly because of the breeding efforts it takes to get this new trait introduced to the earliest maturing varieties more suited to Western Canada.

“We are continuing to introduce soybean genetics with earlier maturity, which helps with the expansion of soybeans in Western Canada,” he adds. “Not only are growers seizing the opportunity to grow a new crop, but the maturity of the newest varieties is starting to be timely enough to allow the crop to expand further west across the Prairies.”

The benefits of strip tillage are easily realized in richer soils, but regular soil testing and machine calibration are very important.

by Treena Hein

Combining the benefits of both conventional and zero tillage, strip tillage involves only tilling strips of about 10 inches in every 30 inches of field. It’s become a popular option for corn and soybean crops in traditional U.S. Midwestern growing areas and is being researched in Western Canada.

The practice opens ready-to-seed strips in fields that are covered with heavy residue, putting the fertilizer into the soil where it’s most needed. It also warms the soil in the strips more than soil that’s not tilled, but the field also remains protected from erosion and moisture loss by the remaining residue.

Jim Patton, the president of the Innovative Farmers Association of Ontario and a cash crop farmer northwest of Alliston, Ont., tried strip tillage in 2000 after hearing that Greg Stewart, a corn specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food, was doing a study on it. Patton had some information from equipment dealers and decided to give it a try. “It became a standard part of our program and we would never change that. It works really well.”

For Patton, strip tillage reduces costs relating to labour, equipment wear and fuel, in addition to bringing up the average corn yield among all his fields, where soil type variance is a factor. “It’s also environmentally sound in my opinion,” he says, “as you’re only working that strip and you’re putting fertilizer exactly where you need it.”

The first year, Patton tried strip tillage in the fall, but he found the berms sank too much and emergence wasn’t good enough as the soil took too long to warm up. “We started doing it in the spring after wheat and before corn. The soil warms up more and you can put down all our nutrient requirements for the season at once.”

Overall, Patton characterizes it as a technique that provides “better efficiency” from a fertilizer program. “It allows us to use 30 per cent less fertilizer to get the same yield opportunity,” he explains. “It’s really the nitrogen that you can use 30 per cent less of to get the same bushels. We do soil tests regularly and tweak the P and K.” Patton has also, over the last few years, gone to a mix that has 25 to 30 per cent slow-release ESN nitrogen, and says it’s given good results. “We also did some reduced-rate test strips one year and again this year, and our yield didn’t vary, so that tells us our fields are in good shape,” he notes.

Patton started out using a Yedder Maverick 2 strip-till implement, but he and family members did quite a bit of work to

customize the mold knife and exhaust pipe, modifications that allowed it to handle 12 rows instead of six. “We also incorporated an air cart to deliver all the fertilizer into the row, not through the planter,” he says. “It’s sped it up tremendously, as you don’t have to stop and refill the planter all the time.” They now use a larger air cart with a John Deere 2510S strip-tillage air seeder, which is also used in the fall for winter wheat planting. “It’s a heavier machine with flexible capabilities for the side hills,” Patton explains. “There are three sections totalling 30 feet, and the flexibility in the frame is great.”

About a decade ago, Stewart did a study in West-Central Ontario looking at the effectiveness of fall strip tillage and fertilizer placement on corn in comparison to conventional and no-till systems. The conventional treatment involved

moldboard plowing to a depth of six inches with two passes of spring secondary tillage, and fall fertilizer broadcast on the soil surface shortly before plowing. The fall strip-tillage treatment involved eight inches on 30-inch centres, at a depth of six to eight inches. Fertilizer was

applied in the fall at a depth of six inches in the centre of the tilled strip. The last treatment was no-till with fall fertilizer broadcast on the soil surface.

On the sites where requirement for K was high, Stewart found that applying P and K fertilizers only in the fall did not maximize corn yields. “We found that placing the fall P and K in a band within the strip-tillage system didn’t remove the requirement for P and K applications through the planter in the spring,” he says, “which is what we’d hoped for.” He thinks the band was maybe too deep and/or the fertilizer application was too central for the plants to be connected to the N supply. “It’s not a great idea to put fertilizer straight down below the corn plant because they don’t go straight down,” he notes. “Using a planter to apply fertilizer would have worked better in these needy soils, which goes two inches down and two inches to the side. It’s not the amount, it’s the timing and placement.”

Strip till has its place in soils that are rich, Stewart says. “If your strip till could be spring-based and included all P and K you need for your crop, and you put it in six hours ahead of corn planter, it would work,” he notes. “It would be operationally savvy to do that ahead and planting goes much faster as well.” Some attention would need to be paid to fertilizer burn, but Stewart thinks that could be resolved. Patton has a neighbour who strip tills in the fall, but he prefers to strip till in spring. “It depends on your soil for the most part,” he says. “We have mainly Brookston clay loam to Harriston loam with a bit of tioga sand and Tecumseth clay. The strip tillage works well for us in the spring because it warms the ground more quickly. We get a good gain in maturity and drydown on land that doesn’t do as well as other land.”

He advises anyone who wants to start strip tillage to start small, on land where you want to bring up your average corn yield. “The cost is reasonable with a six-row implement,” Patton says. “It’s one of many things you do to improve things on poor land, but it definitely takes more management. We spend a lot of time calibrating equipment. It’s not get in and go.”

by Amy Petherick

Before they had even outlined what it was, farm leaders sought to have Environmental Farm Plans (EFPs) implemented on roughly 40,000 Ontario farms within the program’s first decade. Although that target clearly missed the mark, farmers have still felt the program’s impact.

Statistics indicate the EFP program has had a good run so far. The program was launched in Ontario in 1992 and can claim more than 70 per cent of Ontario’s farmers as participants since inception. Between April 2005 and March 2013 alone, approximately 14,000 farm businesses had action plans completed and peer reviewed. Participation in the EFP led to 23,000 on-farm environmental projects being completed over the same time period through associated cost-share programs. Total project investment topped $325 million and it’s estimated that farmers themselves invested approximately two-thirds of all final implementation costs.

Andrew Graham, director of operations for the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association (OSCIA), has been involved with the program since its early days. He believes farmers have

demonstrated a sincere commitment to environmental protection through OSCIA’s program because it is voluntary, confidential and practical.

“There’s no argument that regulation is one of the tools that can be used to influence behaviour,” says Graham, “but the whole premise behind the EFP was not to encourage farmers to just meet regulatory standards, it was to go above and beyond.”

Success seems to be in the eye of the beholder where this program is concerned. Graham says that in the 30 years that he’s been doing soil and water conservation work, he’s never seen another government supported program with the numbers EFP is boasting. But Max Kaiser, a cash crop and poultry farmer in Napanee, Ont., and a recent past president of the OSCIA, is more reserved. He’ll never forget how one American lobbyist declared similar commendations about the program to be dismal results,

ABOVE: Road signs have become an iconic part of Ontario’s rural landscape and an indication of farmers’ fierce sense of pride as land stewards.

given the program’s working time frame.

“He was really critical, but he was right,” says Kaiser. “By now, there should be nobody in Ontario who doesn’t know about EFP and I’m sure there still are people who don’t know about it.”

Kaiser doesn’t think it was ever realistic to think the program would be able to change the practices of every farmer in the province. He and his father Eric were always optimistic about the change it could help bring about, so their farm has always readily adopted evolving editions. With the funding they received following the third edition, the farm improved their manure handling facilities. Kaiser, however, believes the empowerment he got from the program was far more valuable than any costshare opportunities.

“Chicken manure smells and I know better than anyone else I’m stinking up the neighbourhood,” says Kaiser. “I need to not only try to do a good job of managing it, but I also need the neighbours to know that I’m trying to do a good job of managing it.”

Kaiser says the greatest difference the EFP has made for the farming community is to provide a tool to measure their own awareness of weaknesses, and to help farmers be confident in their own analysis of problems and do a better job of managing them. Gordon Green, a cash crop and dairy farmer in Oxford County, Ont., couldn’t agree more. Green was initially skeptical about the program but after hearing positive feedback about the program from other farmers, he became a participant, then director on the local OSCIA branch, and also sat on the peer review committee for a number of years. Based on his experience, Green doesn’t believe farmers in Ontario were very conscious of poten-

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. This product has been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from this product can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for this product. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS.

Roundup Ready® crops contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for canola is a combination of two separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, thiamethoxam, and bacillus subtilis. Acceleron and Design®, Acceleron®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity Icons, Genuity®, RIB Complete and Design®, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup®, SmartStax and Design®, SmartStax®, Transorb®, VT Double PRO®, YieldGard VT Rootworm/RR2®, YieldGard Corn Borer and Design and YieldGard VT Triple® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Respect the Refuge and Design is a registered trademark of the Canadian Seed Trade Association. Used under license. ©2013 Monsanto Canada Inc.

tial environmental hazards on the farm before the program was established, and feels the program did a lot of good in his area.

“People became aware of the weak areas on the farm and where they were vulnerable,” says Green. “Even if they didn’t do something right away, when an opportunity came along down the road, they knew they could work it in and then it got done.”

But he sees how the program hasn’t been perfect too. Initial adoption might have been too slow to quell the skeptics and he’s questioned, at times, if funding has always been put toward the greater good the way the program initially intended. Green believes it’s fair for taxpayers to share some costs but only where society benefits as a whole from implemented practices. “If we’re protecting water and streams, society as a whole benefits so it is only right that there be cost share to help the farmer because everybody is sharing in the benefit,” says Green. He didn’t personally feel that assisting farmers with the purchase of GPS equipment, for example, was as much to the benefit of society as it was to the farmer.

“At its heart [the program] is still deeply rooted in the farm community and there’s incredible pride of ownership.”

But both Green and Kaiser are examples of program participants who were motivated very little by available funding. On Green’s farm for instance, the money he received helped to build an anaerobic digester on the farm and even though every little bit helped, the contribution from the EFP had little impact on such a major expense. Graham notes it’s important to remember the program was never meant to be about the money. Cost-share opportunities attracted many farmers to the EFP, but the ability to recognize themselves as a true land steward has become a badge of honour to many.

“Even though we’ve seen the program change with the various funding structures, at its heart it is still deeply rooted in the farm community and there’s incredible pride of ownership,” says Graham. “Sometimes I think we forget just where this program came from.”

After all, he says, it was a few visionary farm leaders who developed the original document that led to the EFP and started the farmer-helping-farmer approach it’s now known for. He believes they laid a critical foundation not only by deciding to write their own environmental destiny for Ontario agriculture but also by inviting governments of the day to join them in endorsing it. Regardless of the EFP’s triumphs and failings, it is notable that a group of provincial, federal and industrial representatives were able to form a stalwart partnership and even more extraordinary that they never waned in their commitment.

Ontario is keeping a watchful eye on this disease.

by Melanie Epp

With incidents of Asian soybean rust on the rise lately in the southern United States, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food (OMAF), along with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) and the Grain Farmers of Ontario, will be watching closely to see if spores make their way across the border.

Early monitoring is key, and Ontario has been part of the North American early warning system from Day 1, says Albert Tenuta, field crop pathologist at OMAF. “The whole system consists of real-time assessments and detections of soybean rust in the field, starting from overwintering potential to early spring conditions,” he says, which will help predict the risk of the disease to Ontario producers.

What is Asian soybean rust?

There are two fungal species that cause Asian soybean rust: Phakopsora pachyrhizi and P. meibomiae. The more aggressive of the two is P. pachyrhizi, or Asian soybean rust. First reported in Japan in 1903, the fungus was confined to the Eastern Hemisphere until it was reported in Hawaii in 1994. In November 2004, it made its first appearance on continental North America.

According to the North Central Integrated Pest Management Centre (NCIPMC) in the United States, Asian soybean rust spreads through spores, which are released into the air if exposed plants are disturbed. Winds can carry spores great distances, a problem especially during hurricane season. P. pachyrhizi is capable of infecting over 90 species of legumes. Kudzu, which is widespread throughout North America, is one of those hosts, serving as a reservoir for the fungal pathogen.

Once infected, the lower leaves of the plant begin to show small lesions, which gradually increase in size as the fungus progresses. The lesions change in colour from grey to tan or reddish brown, and appear on the underside of the leaves. While they appear most commonly on leaves, lesions can also occur on petioles, stems and pods. Once pod set begins, infection can spread rapidly to the middle and upper leaves.

Soybean rust’s presence is strongly determined by environmental conditions. Milder temperatures and rainfall provide the right environment for the fungal pathogen to reproduce. The fungal pathogen prefers prolonged periods of moisture, particularly leaf moisture, and temperatures between 15 C and 30 C. The spores require humidity levels of 75 to 80 per cent for germination and

infection. Under the right conditions, pustules will form within five to 10 days, and spores are produced within 10 to 21 days.

Early on in the season, the focus is on the southern United States, where risks are assessed throughout soybean production areas. As of mid-August, 2013, soybean rust has been scouted for and confirmed in several states, including Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Kudzu, in particular, is monitored throughout the Gulf States from Texas to Florida and as far north as Ontario. The warmer the temperatures,

the more the greening of the kudzu thrives and survives. Rust infection can survive on the leaves throughout the winter.

“Kudzu is the overwintering host in North America where soybean rust has established itself,” says Tenuta. “It does overwinter in the U.S. Gulf States from year to year, so it is a yearly issue.

“If you have a cold snap where temperatures go below -2 C for a few days or so, which causes the kudzu to defoliate or lose their leaves, then that substantially helps us in terms of reducing our risk because the rust has to re-infect the new developing leaves and the new growth, so it takes a bit more time to build up inoculant.”

Fortunately, in recent years there have been cold enough winters that have resulted in just that. “This past winter is probably a good example of what potentially could result in more overwintering of the kudzu in the southern United States,” says Tenuta. “And what we’re starting to see into late July and the beginning of August is considerable movement of soybeans, as well as kudzu, from Florida up into Arkansas and Georgia and those areas. Potentially, we may see that move into maybe Tennessee, Kentucky and beyond.”

Ontario has been proactive when it comes to preparing for Asian soybean rust, though. As part of the network, soybean plants are assessed on a weekly basis, not just for soybean rust, but for other diseases as well.

“We also, in conjunction with Ag Canada in Ottawa and the Grain Farmers of Ontario, continue to collect rainfall that can be assessed for soybean rust spores,” says Tenuta. “More than likely what we’ll see with the buildup in July is that spores will migrate and make their way into the province. The good thing, though, is just because spores make it into the province, as we’ve seen for

most years, it doesn’t necessarily mean that that infection will occur. You still have to have the right environmental conditions, and you have to have enough of the spores coming up to be of concern.”

With the assistance of the public breeding programs, in particular those at the University of Guelph and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, breeding efforts have been put into place, incorporating soybean rust resistance and tolerance into commercial soybean varieties. A number of promising lines have been tested under significant soybean rust pressure in Florida in co-operation with the North Central Soybean Research Program and the Soybean Rust Coalition here in Ontario. Researchers have been able to identify some lines that could assist in incorporating soybean rust resistance and tolerance into commercially available soybean lines, which are in development now. Private companies have been doing the same, but as breeding takes time, it could be a few years before those lines are commercially available.

“Progress has been made,” says Tenuta. “Resistance and tolerance, in conjunction with fungicides that are available, as well as scouting and detection, put us in a very good position to manage anything that comes up, from a soybean rust standpoint.”

Grain traceability is gaining ground.

by Treena Hein

As Bruce Saunders, the chair and president of OnTrace Agri-Food Traceability Inc. (the organization that spearheaded traceability in Ontario up until 2012), stated in the November 2012 issue of Top Crop Manager, traceability is not yet mandatory in Canada, but the benefits to the agricultural industry as a whole are many. Whether it involves bread, ready-to-cook seasoned poultry pieces, tomatoes or grain, it’s all about safeguarding our health in times when food safety incidents occur – and presenting an image of Canada’s ag industry as responsible and responsive.

As you may have learned by now, traceability of any food product is a matter of keeping track of three key pieces of information.

“Product Identification” is one – identifying animals or food products or components of food products as individuals, lots or batches.

“Premises Identification” involves a record of where each component of the food product or the animal originated, and “Movement Recording” involves tracking identified products as they move between identified premises.

Crop farmers who grow Identity-Preserved (IP) soybeans for export are highly familiar with all three of these aspects of traceability. They have always been required to maintain chainof-custody information for each shipment. However, getting an idea of IP soybean tonnage in Canada, the number of farmers involved and whether traceability requirements have changed for IP soybean farmers in the last few years is hard to do.

New-Life Mills became involved in traceability more than six years ago as participants in FeedAssure, a feed safety management and certification program.

ABOVE: For a feed mill, traceability involves managing such information as lot numbers and customer lists, according to Ryan Kreager, manager of corporate risk and compliance at New-Life Mills in Hanover, Ont.

Dave Buttenham, secretary manager at the Canadian Soybean Exporters’ Association (CSEA), reports that this data “is not tracked by CSEA, and in many cases, may be treated as proprietary market information by CSEA members.”

The grain industry already tracks batches of grain to some extent. When these batches are mixed with other grains to make livestock feed or for export to international destinations, a new lot or batch number is given to the new mixture. Although feed manufacturers do not directly supply products to consumers, they aren’t yet under strong pressure to have full traceability in place. “But it is coming,” says Ryan Kreager, manager, corporate risk and compliance, at New-Life Mills in Hanover, Ont.

Kreager has had that title for more than six years, since the company started tackling traceability as part of its participation in FeedAssure, a comprehensive feed safety management and certification program developed by the Animal Nutrition Association of Canada for the country’s feed industry. In addition to FeedAssure, he also handles Canadian Food Inspection Agency program compliance, employee health and safety, and is the point person for traceability emergencies.

“For a feed mill,” Kreager says, “traceability involves managing standard information like customer lists and lot numbers.” He explains that while the organization that now handles premises identification in the province (Originally OnTrace, but now Angus GeoSolutions Inc. or AGSI) already has the locations of many agricultural operations and information on each one’s type: “with our information, in an emergency, we can confirm locations and the type of farm by what we deliver where.”

Kreager notes that at this point, it would be tough to trace grains all the way back to the field, because of commingling at terminals and elevators, but he’s not sure it’s necessary anyway. “There are multiple tests of grain quality at all steps in the process at elevators and before grain is processed into flour or feed, so it’s a question of how far back you’d have to go in a specific situation to access test results if there was a problem,” he notes. “It would be a huge amount of time and effort to trace grain back to the field and I’m not sure you’d ever need to go that far back with all the testing at each stage.”

Warburton’s, Britain’s most popular baked goods manufacturer and distributor, and the largest grocery brand in the country, does indeed trace all grain back to each and every farm it buys from. Every day, more than 5,000 Warburton’s employees make and distribute more than two million bakery products to 14 bakeries and 15 distribution depots – using more than 900 delivery vehicles to eventually deliver products to thousands of retail outlets in England, Scotland and Wales. The company clearly views traceability as one part of a much larger business strategy – a way to guarantee food safety and quality. It has traceability in place from the “primary sector” (raw materials/farm level) to the “secondary sector” (operations such as flour mills and the Warburton’s Research & Development department, that manufacture, refine or test goods made from the raw materials) into the “tertiary sector” (transportation, distribution and retail). Farmers who supply the company must keep the annual 400,000 tons of Warburton’s wheat separate from other wheat and grains so supply can be traced back to each farm. Warburton’s wheat is also milled separately by flour millers.

The company also ties traceability into reducing its environmental impact. To decrease its “carbon footprint,” the company

uses software to track delivery routes to ensure that they are as efficient as possible. Drivers also make deliveries at different times of the day to avoid traffic congestion and save a substantial amount of fuel.

In March 2012, Angus GeoSolutions Inc. (AGSI) based in Halton Hills, Ont., was chosen by the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture (OMAF) to develop, implement, operate and expand the new Provincial Premises Registry (PPR). To register your premises, you are asked to provide your Assessment Roll Number (your tax assessment number from the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation) and if you cannot provide this, you will need to provide GPS co-ordinates, a municipal address or a Legal Land Description (Lot, Concession Number and Township).

Crop farmers who grow Identity-Preserved soybeans for export have always been required to maintain chain-of-custody information for each shipment.

Chris Cameron, the president and CEO of AGSI, says that there has been good response this year from operations within different commodity groups as well as from independent business owners. “We’ve had a 40 per cent increase in registrations over the previous total since we took over,” he says. “That’s partly a result of commodity organizations encouraging their members to get it done.”

Cameron says his company provides a very secure system, so farmers can be reassured that farm location and other information kept in the PPR is safe from hacking. “We handle information for credit card companies, Elections Ontario, insurance companies and so on,” he says. Cameron adds that his company will pursue being part of the expansion of traceability in Ontario into product ID and movement tracking.

To move forward on that front, OMAF has introduced the Traceability Foundations Initiative (TFI), a three-year joint federal-provincial funding program that may provide up to 75 per cent cost-share funding to sector organizations to support voluntary, industry-led information-sharing networks that will enhance agri-food traceability. Approved projects may be eligible for up to a maximum of $5 million in funding. Projects selected for funding through “Intake 2” (this year’s round) of the TFI “will support the design and implementation of Information Sharing Networks across sector organizations and value chains within agriculture, agri-food and agri-based businesses, leading to effective information sharing systems that include premises identification, animal/product identification and movement recording.” Projects will develop or enhance information sharing that meets identified business objectives and achieves measurable outcomes that align with TFI program objectives.

For more on traceability, visit the business and policy section of www.topcropmanager.com.

Four key management strategies using cover crops.

by Melanie Epp

Ahigh-moisture year – like this year, in many parts of Ontario – can cause producers a multitude of problems, including a proliferation of weeds, increased soil erosion, potential nutrient loss, and compaction issues. But there is one management solution that can help alleviate all four: the use of cover crops. Anne Verhallen, soil management specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food, shares her knowledge on using the right cover crop for the right job.

Some cover crops have the ability to suppress weeds, likely due to shading, competition, and allelopathy, which occurs when one plant produces organic compounds that have negative effects on other plants.

“Any cover crop is going to do a decent job of suppressing weeds,” says Verhallen. “But if you’re really targeting weeds, some of the best crops are in the Brassica family.”

Members of the Brassica family, including oilseed radish, turnip

and kale, are very competitive. They’re also high nitrogen feeders, so they will reduce the amount of nitrate in the soil, making it difficult for weeds to grow. Brassicas also put out massive amounts of leaf tissue, which is good for providing shade to reduce germination.

Buckwheat has traditionally been a good solution for weeds as well, says Verhallen. It’s a great choice because it has large leaves and grows rapidly. “But there are some cautions that come with buckwheat,” she says. “Because it’s a very short-season, warmseason type of cover crop, it’s not going to take a frost,” she says. “It will also flower very quickly, and once it flowers, it’s already

TOP: Oilseed radish, a member of the Brassica family, is a highnitrogen feeder that reduces the amount of nitrates, making it difficult for weeds to grow.

INSET: Buckwheat is a good cover crop to manage weeds, due to its rapid growth and large leaves. But as it’s a warm-season type of cover crop, it won’t take a frost, according to OMAF’s Anne Verhallen.

setting seed. It’s not very tolerant of herbicide carryover either.”

According to the Midwest Cover Crops Field Guide, the classic use of cover crops has been to cover soil, protecting it from both wind and water erosion. Having live roots in the soil helps to hold it in place, thereby reducing erosion. Depending on what you’re looking for – fast cover or lasting residue – there are a number of ways to approach cover crop usage when managing for soil erosion.

“Our target for erosion control, at least in the spring, is to have at least 30 per cent ground cover through cover crop residue or previous crop residue after planting,” says Verhallen. “That 30 per cent is related to what it takes to reduce water erosion, and in particular, raindrop impact.”

For minimizing soil erosion, just about any cover crop will do. “It’s a matter of getting the ground covered,” says Verhallen. “You’ll want to choose a crop that gives you a lot of top growth, like oats, winter wheat, winter rye, and winter triticale. These crops will give you cover over the winter, as well as lasting cover come spring.”

Both soil structure and aggregate stability play an important role in soil erosion as well. “If you’re looking for stable aggregates at the soil’s surface,” says Verhallen, “you’re still looking at a fibrous

root system.” Choosing grasses like oats, barley, winter wheat, winter rye and triticale will help build both soil structure and resistant soil aggregates.

In systems that use manure or where vegetables are harvested early (sweet corn, for example), or in situations where crops don’t survive due to heavy rain, attention to nutrient management will be necessary. “You’re looking for nutrient cycling, something that will scavenge the nutrients and prevent leaching,” says Verhallen. “Generally, you’re looking for something that’s going to be a heavy feeder on nitrogen.”

Brassicas are heavy nitrogen feeders, especially radish and oats (in the fall), and rye and winter wheat come spring. “Our challenge with some of these other cover crops, like oats and radish, is that they die over winter,” says Verhallen. “They’ll die very late, and they will hold nutrients for quite a while. But they’re dying around Christmas time or early January, and we won’t have a corn plant there for months to be able to pick up those nutrients. So we can’t give them a really great credit towards the next crop. And that’s a very unsatisfying answer for a lot of people.”

Another concern for producers is phosphorus, particularly soluble phosphorus that gets into the Great Lakes and contributes to algae blooms. “While cover crops

are pretty good at nitrogen uptake, where they really shine is with the phosphorus – keeping soil intact and taking up some soluble phosphorus before it gets leached away,” says Verhallen.

When it comes to compaction, cover crops can be used to provide channels through subsoil or to loosen topsoil. They also provide additional food for soil fauna such as earthworms. Any cover crop will add some improvement to the soil structure in the top six inches. To really punch holes in the compacted areas, though, you ideally need a more established root, something like sweet clover or alfalfa.

“If you’re trying to go below that,” says Verhallen, “then you’re looking at something with a taproot system. Alfalfa and sweet clover have the best tap roots for that.”

For a short-term cover crop, try something in the radish or Brassica family, says Verhallen. “They do have a taproot, and it will get its way through as long as you’ve got some soil moisture. But it’s not going to necessarily break up a true tillage pan, just because it’s not growing long enough.”

Cover crops are a great solution for many problems that farmers face, but there are challenges to consider as well. Sourcing (and establishing) seed can sometimes prove difficult, especially in years where seed may be in short supply. Choosing the right cover crop and fitting it into your rotation system can also be challenging. There is also the potential for pests, and weeds and herbicide programs to consider. Finally, the additional cost can be a burden to some.

Perhaps most importantly, Verhallen says, producers should have a termination plan in place before adding a cover crop to their rotation. “Sometimes farmers get a surprise if they haven’t grown a lot of these cover crops before,” she says. “They’ll find that they had a wide open fall, lots of moisture, and suddenly they’ve got three feet of radish and oats everywhere. It’s just one of those things where you want to make sure you’re thinking ahead and have a plan in place.”

At the end of the day, says Verhallen, you have to make sure you have the right cover crop for the right job at the right time of year. “My goal is for producers to have success in cover crops and build up some confidence and experience in using them.”

SENIOR EXECUTIVE FINANCIAL CONSULTANT INVESTORS GROUP FINANCIAL SERVICES INC.

| PAUL R. VAILLANCOURT, CFP, CLU, CHS and CPCA

You’ve worked hard to make your farming operations a success. There may have been times when you gambled on a business strategy and won – but, for the most part, you stuck to your plan. Now, it’s time for a new plan.

What would happen to your farm business if you were taken away from it, even temporarily? Would it survive? If you’re like most small farming operations, the odds are that your years of careful nurturing and building could come tumbling down without your energetic hands on the reins – because you are your business.

Where will the money come from to pay for your employees, business loans and other operating expenses to keep the farm going and to protect your investment if you get hit with a sudden, extended illness?

If your farming operation is structured as a partnership or corporation, would you wish to buy your partner’s interest or shares in the event of his or her death, disability or critical illness? You may have a partnership or a shareholders’ agreement in place, which is an excellent start. However does the agreement contemplate death or long-term disability of a co-owner and would you have the necessary funding available to actually purchase their interest, or do you prefer to have your partner’s spouse or child as your new partner?

There’s no need to gamble with your future financial health when you can take some essential steps right now to protect what you’ve built. It’s called business continuation planning and it’s the process of identifying issues that could put your business at risk and adopting strategies to help mitigate or eliminate those risks.

As a farm owner, you understand the need to protect against risks to your capital assets: that’s why you have fire, theft and other forms of insurance. But one of the major, yet often overlooked, risks faced by nearly every business is the temporary loss of vital human capital: the loss of a business owner due to a disability as the result of an accident, an extended illness, or even a life-threatening critical illness.

The risk is more likely than you think. Ninety per cent of Canadians have at least one risk factor for heart disease or stroke, according to the Heart and Stroke Foundation. The disability rate increases steadily with age beginning around age 25. Adults aged 45 to 54 have a disability rate of 15.1 per cent, according to a 2006 participation and activity limitation survey by Statistics Canada. And, on average, 500 Canadians will be diagnosed with cancer every day, according to the Canadian Cancer Society.

With the right business continuation plan, you’ll protect your business and your income in a number of ways:

• supporting continued business performance, profitability and productivity

• assuring that business debts can be serviced

• retaining employees who will continue to view the business as viable

• maintaining good supplier relationships

• preserving your customer/client base

The risks posed by the temporary loss of a primary farm owner can be economically managed with critical illness and disability insurance, the cornerstones of an effective business continuation plan.

Disability insurance allows an owner to fund the payment of ongoing essential business expenses such as salaries of employees, utilities and property taxes (Business Overhead Expense Disability Insurance) and replacement of personal income to pay family expenses during the period of the disability with tax-free dollars (Personal Disability Insurance).

Critical illness insurance pays a one-time lump sum to help cover losses created by the owner’s absence. When the insured person is diagnosed with a critical illness or condition as defined in the policy, the benefit is paid; how it is used is totally up to the recipient. It can be used to provide a vital injection of cash to pay recurring business expenses or to make payments on loans or to suppliers.

Personal protection is key to every business continuation plan. Here are some other plan elements to consider:

• Key person life insurance ensures there will be a timely injection of tax-free capital should your business suffer the loss of a top producer or other essential employee.

• Buy-sell life insurance can fund your purchase of a deceased partner or shareholder’s financial interest in the business.

• Disability and/or critical illness buy-out insurance provides a lump-sum tax-free payment to fund your purchase of a deceased partner or shareholder’s financial interest in the business.

• Potential creditor protection by use of personally owned segregated investment funds.

You have spent a lot of time developing and growing your successful farm business. It wasn’t easy and it continues to evolve in response to the market demand and customer needs. Your business continuation plan is a vital component of your operations. Protect what you’ve built with a business continuation plan tailored to your business: it’s vital to your continued success, come what may.

This is a general source of information only. It is not intended to provide personalized tax, legal or investment advice, and is not intended as a solicitation to purchase securities. Paul Vaillancourt is solely responsible for its content. For more information on this topic or any other financial matter, please contact an Investors Group Consultant.