TOP CROP MANAGER

COVER CROP

STRATEGIES

Interseeding has benefits for standing corn PG. 12

ADD VALUE AND IMPROVE SOIL

Double-cropped forage shows promising results PG. 8

A BUFFER ZONE COMPROMISE

Perennial cereals may prove to be productive PG. 10

Interseeding has benefits for standing corn PG. 12

Double-cropped forage shows promising results PG. 8

Perennial cereals may prove to be productive PG. 10

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS FORAGES CROP MANAGEMENT

5 | Bumper crop yields

Cover crops planted alongside digestate yields promising results.

By Julienne Isaacs

10 Perennial cereals: a buffer zone compromise By Madeleine Baerg

18 Malting barley goes east By Carolyn King

THE EDITOR

4 Mergers on the mind By Stefanie Croley

8 | Double-cropped forage

This practice adds value to wheat system and improves soil quality.

By Trudy Kelly Forsythe

CROPS

16 A look at Ontario’s declining flax markets By Julienne Isaacs

CROP MANAGEMENT

20 Diversifying crop rotations By Trudy Kelly Forsythe

PROTECTING SOYBEANS FROM NEMATODE PARASITIC INFESTATION

Researchers at Kansas State University have designed and patented a soybean variety that protects from nematode parasitic infestation. The variety affects nematodes by stopping their reproduction cycles.

12 | Interseeding impacts

Quantifying the effects of interseeding cover crops into standing corn.

By Carolyn King

SEED TOPICS

22 Overcoming poor stand establishment in winter wheat By Julienne Isaacs

PESTS AND DISEASES

24 An unwelcome visitor in soybean fields By Madeleine Baerg

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

CROLEY | EDITOR

Unless you’ve been avoiding the news, you’ve probably heard the word “merger” buzzing around the agricultural community lately, and for good reason: in September, Bayer announced it would acquire Monsanto in an all-cash deal valued at $66 billion U.S., following on the heels of the recent Dow-DuPont merger and ChemChina’s acquisition of Syngenta. The deal is expected to close by the end of 2017.

Pending regulatory approvals, these mergers will leave nearly 60 per cent of the global seed market and 64 per cent of the global pesticide market in the hands of three companies, according to data from ETC Group (an action group on erosion, technology and concentration).

Naturally, this announcement has been met with mixed reactions from different parties, and has led to two separate organizations calling on the federal Competition Bureau to review the possible implications of the deal.

In the days and weeks following the Bayer-Monsanto announcement, my news feed was flooded with articles about the merger, calling it “worrisome” and saying it would “threaten food security.” Commodity groups, consumer groups and everyone in between put forward questions and concerns, many of which are certainly very real. Will the agriculture industry be faced with a monopoly that will increase prices for both farmers and consumers? Will consolidation, resulting in less competition, mean less initiative to pursue research and innovation? Will these mergers negatively impact the livelihoods of smaller farmers? Will the GMO debate be reignited?

A mong the agriculture community, the Canadian Federation of Agriculture (CFA) is concerned about equal control in the marketplace, according to president Ron Bonnett. In an interview with CBC, Bonnett said the CFA is asking the Competition Bureau to “examine what the impact is going to be” and make sure “there’s fair pricing and competition in the marketplace.” As Bonnett pointed out, seed pricing has a direct impact on farmers and the competition aspect of the merger is the federation’s sole concern.

On the consumer side, the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network, a group of 17 organizations with “serious concerns about genetic engineering in food and farming,” also called for a competition review in a separate request. Lucy Sharratt, co-ordinator of the group, told CBC the call for a review is “foremost a concern over the immediate impacts on farmers, but there is a broader impact throughout the food chain globally. If there are fewer seed suppliers and if the seed market is dominated by a few multinational corporations who do have investments in genetic engineering, the question for consumers becomes also, will that mean fewer non-GMO choices in the grocery store?”

W hen discussions like these come up and involve mainstream media, consumers and producers, they often involve misinformation, misunderstanding and miscommunication. These questions will be answered in time, but for now, the onus is on producers and industry more than ever to lobby for their livelihood.

D uring a busy planting, spraying or harvest season, it’s hard to devote time to something other than the task at hand. The work doesn’t end after harvest is complete, but in those rare, quiet moments, consider what you can do to speak out. A producer’s job description continues to change as the industry does, and being an advocate for the industry needs to become a priority.

Manager East – 7 issues February, March, April, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Study shows cover crops planted alongside digestate from municipal waste yield promising results.

by Julienne Isaacs

Buck Ross has had a good year. "We’ve got bin-buster crops,” he says. “Our wheat this year ran over 150 bushels per acre, so much it’s hard to believe it. We had well over 98 or 99 per cent germination in our corn. And our soybeans – I’ve never seen so many bean pods on the plant in my life.”

It’s a surprising result, given that Ross, a farmer based in Arthur, Ont., and owner of the biogas company Ross Enterprises, spent the summer waiting for rain like every other Ontario producer.

But Ross believes there’s a simple explanation: these crops were part of a commercial study he instigated last year, looking at the impact of slurry seeded cover crops on soil health, water retention and the soil microbiome, and crop yield the following year.

Put simply, the cover crops, planted along with digestate sourced from municipal waste, created prime conditions for this year’s crops.

Ross is intrigued by the system for environmental as well as business reasons – or rather, the two are intertwined. Healthy soil creates healthy crops, he says, and agricultural producers play a huge role in carbon capture. “If we improve soil organic matter by 0.4 per cent we will capture over 15 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas,” he says. “Cover cropping is one of the methods of doing this.”

Not only does cover cropping improve the environment, but it also improves the value of the land, and that value stays close to home.

“Every dollar we don’t spend importing fertilizer gives the Canadian economy a lift,” he says. “If you send money out of the country it’s just gone. If you put money in at the bottom it will get to the top.”

It’s a philosophy that has a lot of buy-in from Ross’ community. The project saw investment of seed, time and professional resources (if not financing, which came from Ross himself) from Bio-En Power, Bartels Environmental, Cargill, FS Partners, Grand River Conservation, Pioneer Seeds, Speare Seeds and the Ontario Seed Company. Christine Brown, field crops sustainability specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), helped with the study.

Bio-En Power, Ross’ partner, is responsible for generating most of the power for the city of Elmira, Ont. The company’s biogas plant diverts over 70,000 metric tonnes of organic waste from the landfill sites annually, and uses it to generate electricity. “What’s left is the digestate,” he says.

The digestate is a “well-blended, balanced, nutrient-rich” and pasteurized byproduct of anaerobic digestion, a process that captures the methane from waste for energy. It is also a fertilizer product that can be injected directly into the soil at key points in the season, explains Ross.

Last year’s study involved planting a multi-crop cover crop mix after wheat on three fields (700 acres) of Ross’ operation. Half the strips were treated with digestate, the rest without, and planted at different times depending on wheat harvest.

One overarching goal of the study was to look at opportunities for applying municipal waste during the growing season to extend the application window.

Brown’s interest in the study was twofold: she looked at the differences in root system biomass between the two strips, as well as ammonia losses from digestate with high pH levels.

Her observations of the trial confirmed her assumptions in a few different ways.

According to Brown, every anaerobic digester has a different “recipe” of ingredients that affects the analysis of the digestate, including pH. One key observation from the study was that volatilization of nitrogen into the air as gas happens more quickly when manure or digestate has a high pH. It’s an important finding because of its direct agronomic implications where immediate incorporation is required to

minimize nitrogen losses.

PH is not typically tested for in a manure analysis, but “sometimes farmers talk about their corn crop running out of [nitrogen] N and I wonder if that happens, in some cases, when the pH in the manure is higher than expected,” she explains.

“So if a farmer says they’re going to apply a high pH manure or digestate and incorporate two days later, if you’ve got

a material with a high pH, then you might not have very much left at the end of two days relative to a manure with a lower pH.”

Regarding the practical benefits of using digestate along with cover crops, Brown has a theory that when digestate or any organic amendment is added to the soil, their microbial populations are feeding the soil’s existing microbial populations.

“If they’re at the surface they’re not doing much, but if you plant a cover crop you’ve got a lot more microbial activity at the root system,” she says.

One overarching goal of the study was to look at opportunities for applying municipal waste during the growing season to extend the application window.

There are more agronomic implications from the study. Brown also noticed that when an eight-species mix of cover crops was planted without digestate, all of the root systems demonstrated improved growth – “the diversity made a bigger difference,” she says. But when the eight-species mix was planted with digestate, the grass and radish species in the cover crop mix took over.

“The bottom line is that if you’re applying digestate to a cover crop, don’t waste your money on eight different species, because a couple of those species will dominate. You may as well save

]

your money and stay with the dominant species,” she says.

A small plot research trial initiated this spring near Arthur is evaluating digestate and municipal biosolids application at different opportunities during the growing season, including application with various cover crop mixes.

Results from Ross’ trial last year were not quantified, but the trend showed an increase in plant and root dry matter biomass of about 30 per cent where cover crops had digestate applied. Ross will continue the study “for the next several years” to evaluate its practical impact on his operation.

It’s work he believes is incredibly important, and he’s not alone in that conviction. But without credit where credit is due – and government incentives – farmers are unlikely to adopt similar measures, he says. “Farmers get blamed for a lot of stuff but we get no credit for what we do. This actually makes the world better.”

KNOW. GROW. www.topcropmanager.com

Pre-treat your soybean seed and treat yourself to a better performing crop. Optimize® ST is a dual-action inoculant that combines a specially selected Bradyrhizobium japonicum inoculant with LCO (lipochitooligosaccharide) technology to enhance nitrogen fixation through better nodule formation. Increased nitrogen availability supports root and shoot growth – providing greater yield potential for your crop.

#bottomline Driving the Bottom Line

This practice adds value to wheat system and improves soil quality.

by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

Following a three-year research project at the University of Guelph, researchers now have evidence Ontario farmers can consistently produce high yielding, good quality, double-cropped cereal forages following wheat harvests.

In 2012, to address forage shortages caused by a dry summer, many farmers turned to double-cropped forages following winter wheat, the practice of planting two forage crops in the same season. Overall, the experience was positive but questions remained, according to Bill Deen, an associate professor at the University of Guelph and the lead of the project. So began a research project to look more closely at the agronomics and nutritional aspects of double-cropped forages following a winter wheat harvest.

The project was co-funded by the Beef Farmers of Ontario, the Ontario Forage Council via the Farm Innovation Program, the Agricultural Adaptation Council, the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association and the University of Guelph and

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs partnership. The project was initiated following the 2012 season, when drought caused a shortage of forage.

The trials were planted at the Elora and Woodstock research stations and 12 farm sites throughout southern Ontario in no-till, dry soils in early August during the 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons. Over the three seasons, the researchers collected data on yield, moisture, nutrient (phosphorus and potassium) and nutritional quality and had approximately 400 samples analyzed by using wet chemistry to determine a complete range

TOP: Different cover crops and nitrogen rates were used on plots for a three-year research project at the University of Guelph examining the agronomics and nutritional aspects of doublecropped forages following a winter wheat harvest.

Like any successful crop, timely planting with appropriate management and inputs is essential for producing higheryielding, good quality, double-cropped cereal forages.

of nutritional parameters and nutrient removal rates.

The results indicate oats forage (or an oat-and-pea mixture, if higher protein forage is required) were the best crops for fall-harvested cereal forage. “Good establishment and growth occurred more consistently for oats resulting in higher and less variable forage yields compared to either barley or triticale,” Deen says. “However, from a forage quality perspective, there was little difference between oat, barley and triticale forages.”

The researchers also found double-cropped spring cereal forages harvested in the fall have consistently good nutritional quality. “Total digestible nutrient concentrations were similar for barley, oats and an oat-and-pea mixture forages,” Deen says. He adds, with the 2014 trials that included triticale, total digestible nutrient concentrations for triticale were similar to oats or barley.

Another finding was that including peas as a mixture with a cereal will increase forage crude protein, although adding peas does not significantly affect yield or total digestible nutrient concentration of cereal forages.

“Crude protein concentrations for an oat-and-pea mixture forage averaged 2.7 per cent higher than pure oat forage,” Deen says. “Including peas in a spring cereal forage is of benefit only if a forage with higher crude protein is required.”

In 2012, the trials were planted in early August in no-till, dry soils with rainfall occurring about one week following planting. These trials indicate high fall cereal forage yields are possible even when the spring and early summer are unusually dry.

Timely planting with appropriate management and inputs is essential for successful crop production and Deen says this also applies for producing higher-yielding, good quality, doublecropped cereal forages.

“Plant the cereal forage as soon as possible following wheat harvest,” he says. “Cereal forage yields are increased by additional August growing days, which cannot be made up for by delaying fall harvest dates. Plant even if the soil is dry because the forage crop will get off to an earlier start when the rains finally arrive. Yield is based on timely planting following winter wheat.”

Dean advises planting cereal forages in no-till to preserve soil moisture, and keeping stubble heights low and straw baled

to reduce the amount of straw in the cereal forage. If applying liquid manure, Deen says producers should consider applying the manure, incorporating it into the soil and then planting their cereal forage as soon as possible.

“The moisture provided by the liquid manure, if the cereal forage is planted soon after application, may assist in quick emergence when planted into drier soils,” he says.

As for inputs, the research shows it is best to top dress 50 to 70 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare (kg N/ha) after successful emergence of the cereal crop has occurred. This is because the previous wheat crop depletes the soil nitrogen and additional nitrogen will be needed to ensure high cereal forage yields. Applying 50 to 70 kg N/ha increased oat forage yields, on average, by 70 per cent and crude protein by 0.6 per cent. Even when planted with peas, oats still require additional nitrogen, so Deen recommends applying nitrogen if planting oat and pea mixtures.

“On average, applying nitrogen increased oat and pea forage yields by 30 per cent and crude protein by 1.2 per cent,” he says. “If manure is applied, fertilizer nitrogen rates should be adjusted to account for the available nitrogen provided by the manure.”

Once established and growing, foliar disease, particularly rust, could become an issue so Deen recommends, if possible, planting oat varieties with high resistance to rust. Producers should also scout their crops and consider applying fungicide if they see rust.

If you’re going to sell double-crop forages off farm, you need to consider nutrient removal, since double-crop forage contains one to two cents per pound of nutrients.

As for harvest, cereal forage should be harvested by mid to late October.

“Forage yield gains by delaying harvests much beyond midOctober are small and the drying opportunities needed to make good quality silage or hay diminish quickly after mid-October,” Deen says. “Moisture content of flag to boot stage cereals is about 80 per cent and some in-field dry-down period will be required to reduce moisture content.”

“If you’re going to sell double-crop forages off farm, you need to consider nutrient removal, since double-crop forage contains one to two cents per pound of nutrients,” Deen says.

Double-cropped forages add further value to inclusion of wheat in the rotation – something that really appeals to Deen.

“A lot of farmers think if they grow wheat, they should not bale the straw, but a corn-soybean-wheat rotation with the straw removed is still better for the soil than just a corn-soybean rotation,” he says. “Remove the straw, plant double-cropped forage and farmers can be confident soil quality is being improved.

“If they put in a cover crop and don’t harvest it, it’s good for the soil, but if they do [harvest it], it’s still good. It adds more value to the wheat system.”

Intermediate wheatgrass and perennial rye plant breeders say perennial cereals may limit eutrophication of water bodies while still proving productive for agricultural producers.

by Madeleine Baerg

With increasing frequency and vehemence, fingers are being pointed at farmers over the issue of nutrient runoff into key bodies of water, like Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Until now, the gap between agricultural producers and those who blame those producers for eutrophication has seemed unbridgeable. Farmers argue they have a right to earn a livelihood from their land. Environmentalists – and, increasingly, politicians and laypeople too – argue water quality and the good of all must override farmers’ land use needs. Now, plant breeders are working on developing new perennial cereal crops that may meet the requirements of both sides.

“There are limited options for a cash crop grower who is concerned about nutrient runoff into watersheds. They might think about planting something like grass for a considerable distance around a water body, but that might mean that they give up a considerable amount of revenue,” says Jamie Larsen, a researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alta., and lead plant breeder on a new perennial rye study. “In the future, an option would be to plant

a perennial grain crop that would [be] productive, but also provide significant environmental benefits.”

“Perennial grains require a change in mentality about how cropping is done. They’re different, no doubt about it. But times have changed. Perennial grains offer the potential for economic benefit, while also considering sustainability priorities,” adds Doug Cattani, a researcher at the University of Manitoba who is currently developing a perennial wheatgrass to suit Canadian growing conditions.

Though cereal grains have been treated as annuals for decades, many cereals are willing to function as perennials if given the chance. Rye, for example, is a robust and surprisingly hard to kill plant. Each plant in some varieties of rye can produce productively for three or four years. Other cereals are even longer-lived: Cattani says intermediate wheatgrass can live at least eight to 10 years, and may produce grain productively beyond the four years he has tested them for.

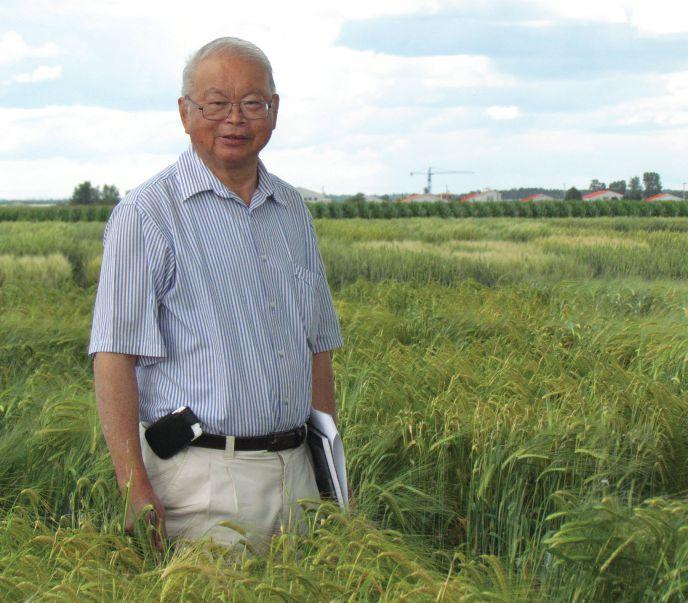

ABOVE: Perennial cereals may provide potentially significant environmental benefits.

In addition to producing a harvestable cereal crop each year, perennial cereals also offer grazeable forage each fall, erosion control and the absence of yearly seedingtime pressure on the producer. Most importantly for those concerned about healthy water systems, perennial cereals have the potential to slow nutrient runoff in a host of ways.

“If you can have something in the ground all year round and actively growing every day of the growing season, you’ll have much less nutrient runoff than if you plant a seed in spring and pull that plant out of the ground 95 or 100 days later,” Cattani says.

First and most obviously, perennial plants capture and remove nutrients from the soil each and every day of their growing season.

In addition to the number of days they are able to capture nutrients each year, perennials also easily surpass annuals regarding the depth of soil from which they can capture nutrients and the total volume of nutrient capture. At between two and three metres in length, perennial cereal roots reach twice as deeply into the soil as do annual cereals. The longer, denser root biomass serves to capture nutrients more efficiently and more deeply in the soil, decreasing nutrient movement through the soil and

limiting the need for additional fertilizer application.

Actively growing perennial cereals also help to use up water that would otherwise sit on the land in early spring, decreasing the likelihood of leaching.

And there’s more: perennial crops’ strong roots, taller plant height and early spring start mean they are more competitive than their annual counterparts. As such, they often require far less weed management. Wheatgrass’ many tillers take competitive advantage a step forward, forming a tight, almost sod-like layer that is highly effective at limiting weeds.

Perennials excel on the disease resistance front too. The fact that they are long-lived typically means they have accrued a superior disease resistance profile that allows them to survive, resulting in fewer fungicide requirements.

Larsen’s perennial rye study has barely begun, but already he is hopeful perennials may have a real place in tomorrow’s agricultural reality.

“The more I work with perennial grains, the more applications I see for them, from the perspective of limiting nutrient runoff to conserving soil, to saving producers input dollars and planting time. This is the next step in cropping efficiency,” he says.

For all of perennial cereals’ benefits,

one fairly serious drawback remains: because a perennial plant must put some energy into its root reserves, it cannot yield as much as its annual cousin. Currently, perennial cereal crop yields are significantly lower than annual cereal crops. Cattani’s intermediate wheatgrass, for example, yields between 10 and 20 bushels per acre.

That said, breeders are already making significant leaps forward in perennials’ yield potential. And, because there is increasing market demand for more sustainable agriculture, farmers might capture better prices for perennial grains compared to conventional annual grains.

“Perennial grains are not going to be as productive as annual cereals. That’s the truth. But it could be a high-value grain that some companies might be willing to pay a little extra for. That’s the potential,” Larsen says.

“There is certainly interest in perennial grains. Quite a number of producers would probably be willing to grow a perennial cereal if we could provide them with a variety that is adapted to their growth area, that offers good yield potential for at least three or four years, and that has a good agronomic package ready when we release the variety,” Cattani says.

Cattani expects perennial cereals are likely still a good number of years from commercialization.

“I’m excited. I see the potential,” he says. “But having said that, I think we’re 10 to 15 years away from releasing an intermediate wheatgrass for our regions. We can’t say ‘plant it’ when we don’t yet know how best to grow it. I think perennial cereals are an area of research you’ll see explored relatively significantly over the next 10 years.

For naysayers who are pessimistic about the potential for a lower-yield crop to find success in Canada, Cattani says: “Before we had canola as a major human-use oil, a lot of people said it had too many issues. But canola is a good example of what is possible when we apply resources to a potential crop to help solve key issues.

“What makes the concept of perennial cereals interesting is – even as it is now – it is a much more productive option than simply planting a forage grass, and it’s really sustainable. It has the potential to make a lot of people with conflicting priorities happy.”

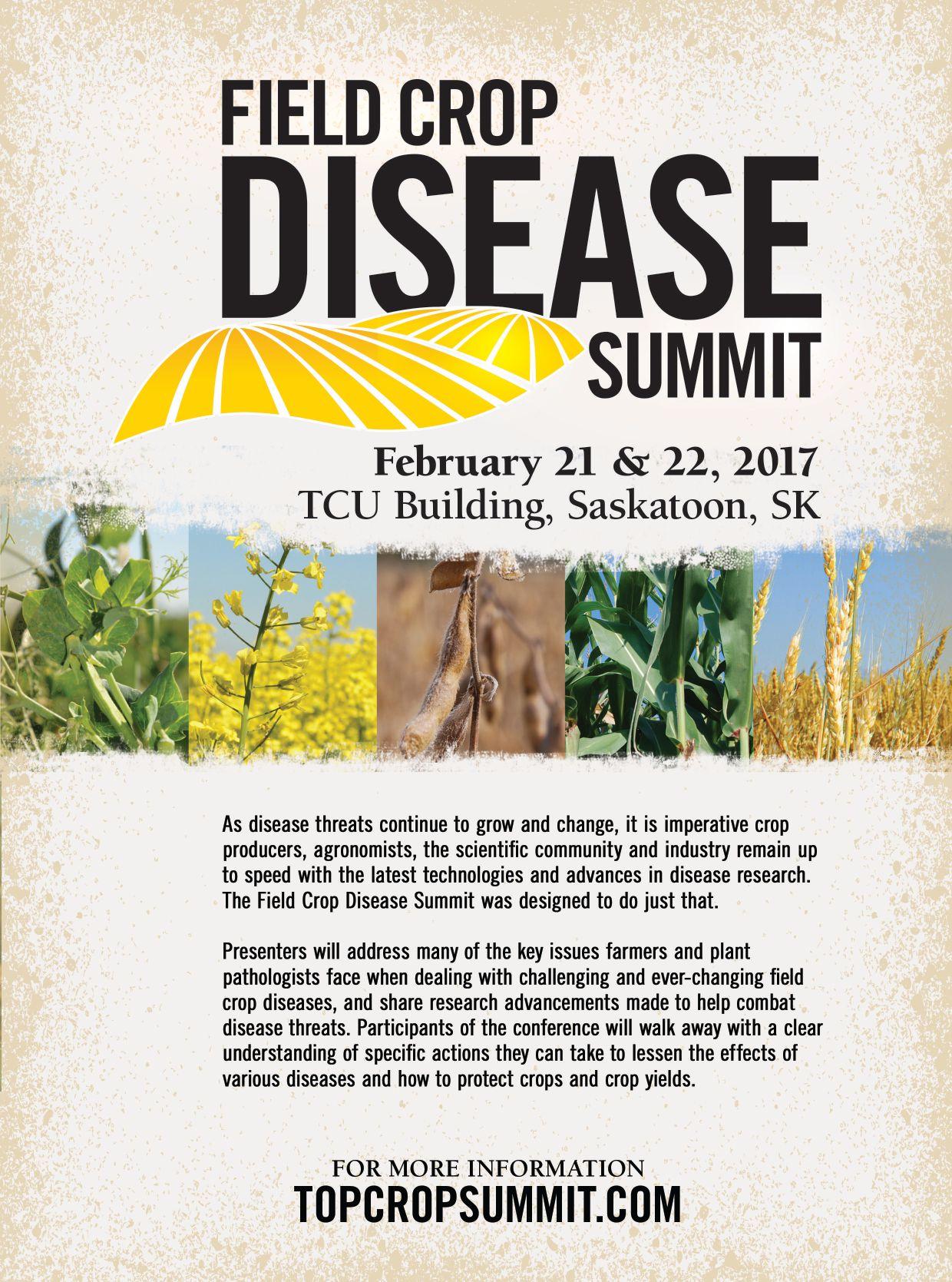

by Carolyn King

In Ontario, interseeding a cover crop into corn is growing in popularity as a way to improve soil quality in a cornsoybean rotation. But just how much cover crop biomass is likely to be produced? How much of an impact will it have on soil quality? And what are the effects on corn and soybean yields? Researchers are putting some numbers to this practice to see how much of a benefit growers might expect.

Mehdi Sharifi at Trent University, Bill Deen at the University of Guelph, and Dave Hooker and Laura Van Eerd at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown campus are conducting this project, with funding support from the Grain Farmers of Ontario. Jaclyn Clark, a master’s student supervised by Deen and Hooker, is also working on the project.

Research about interseeding cover crops into corn is not a new thing. “It’s been studied in various ways for a number of years; Dave Hooker pulled out a study at Ridgetown from the 1980s about interseeding cover crops in corn,” says Deen, an associate professor in plant agriculture.

“Most of the research has been done with silage corn, and there is documented success with interseeding in silage corn. Interseeding in grain corn has also been looked at. The

interest is related to the fact that we and other researchers have documented that a simple corn-soybean rotation has some issues with poorer soil quality [such as lower organic matter levels and poorer soil structure] and lower yield potential, as compared to more complex rotations. So the concept is that incorporating a cover crop into a corn-soybean rotation could perhaps mitigate some of those concerns.”

Cover crops need to attain reasonable biomass levels to provide significant soil benefits. Interseeding into a standing crop gives a cover crop more time to gain biomass, compared to seeding after the corn is harvested. “Our growing season is limited by a long winter; there is not a lot of time for a cover crop to be established after corn. Growers are harvesting corn later and later, and they’re planting soybeans earlier and earlier,” Clark explains.

“We hope with interseeding that we can get the cover crop biomass growing within that niche in the corn-soybean rotation

TOP: In this multi-location project in Ontario, cover crops were seeded into corn at the V5 stage; in most treatments, a Penn State Interseeder was used to drill in the cover crops.

of the project’s treatments – a red clover-annual ryegrass mixture drilled into silage corn – is shown here in late April 2016, just prior to termination and soybean planting. Because silage corn is harvested earlier than grain corn, the cover crop has more time for biomass production.

and produce the amount of biomass needed to make a decent contribution of soil carbon, and with legumes, to contribute nitrogen to the soil. Also, just having some cover on the soil in that little gap in the growing season helps protect the soil from raindrop power and other erosive forces.”

The project is evaluating the effects of red clover and/or annual ryegrass interseeded into corn on cover crop biomass, soil properties, weed biomass, and yields of grain corn, silage corn and soybean.

This two-year project, which started in 2015, is taking place at three research farms in Elora, Ridgetown and Peterborough, Ont. It involves five cover crop treatments: a control with no cover crop; red clover, drilled with an interseeder; annual ryegrass, drilled with an interseeder; a mix of annual ryegrass and red clover, drilled with an interseeder; and a mix of annual ryegrass and red clover, broadcasted.

Clark notes, “A lot of farmers have been really innovative at developing their own interseeding equipment. We used a Penn

This treatment is a red clover-annual ryegrass mix drilled into grain corn, shown in late April 2016, just prior to termination and soybean planting. Previous research has shown there can be valuable synergies from planting a legume-grass mix in a field.

State Interseeder for our drilled treatments, and then we just hand-broadcast for the broadcast treatment. We included a broadcast treatment to see if it would be an option if you didn’t have interseeding equipment.”

The plots were interseeded at about the V5 growth stage of corn (five leaf collars); in Ontario, around V4 to V6 has been found to be most successful for interseeding red clover and annual ryegrass. “We wanted the seeding time to be late enough that the cover crop wouldn’t out-compete the young corn crop. But we wanted to seed it early enough for a decent amount of cover crop growth before full closure of the corn canopy [completely blocks sunlight to the cover crop],” Clark explains. She outlines some of the reasons for choosing red clover and annual ryegrass. “Red clover is already widely used in Ontario so a lot of farmers are familiar with it. It's a legume so it can fix atmospheric nitrogen, and it has been shown in some situations to provide a nitrogen credit to the soil, which can benefit the following crop. Annual ryegrass has been shown to have good biomass potential in certain situations. We included the red clover-ryegrass mix because there has been shown to be

synergies from planting a legume-grass mix.”

Deen also notes both red clover and annual ryegrass are able to tolerate some shade. As well, both will overwinter, so a grower would have the option of terminating them in the spring, allowing more time for biomass production. However, both cover crops have challenges with spring termination. “Annual ryegrass has to be terminated in a timely manner in the spring. If it starts into stem elongation, it becomes very difficult to control. With red clover in the spring, all the movement in the plant is from below-ground to above-ground tissues [which hampers herbicide translocation to the plant’s below-ground parts],” he explains.

Herbicide options are limited when interseeding into corn because some soil-applied herbicides used in corn can injure the cover crops. Clark notes, “For our weed control, we exclusively used glyphosate and only applied it before the cover crops were in the ground. We didn’t spray at all once we planted the cover crops until we terminated them in the spring.” A glyphosate-only herbicide system might result in some weed issues because of the lack of residual weed control and the possibility of glyphosateresistant weed problems. On the other hand, cover crops could help suppress weed growth. The weed biomass data will show the overall effect of interseeding on weed growth.

The project uses corn hybrids and soybean varieties that are typical of the production region, so they are long-season types. Deen explains, “We had considered going to shorter-season types to provide a greater opportunity for cover crop biomass production. But we thought a farmer probably would not be interested in sacrificing yield for the sake of cover crop establishment, and we wanted to keep the project commercially representative.”

However, the project does include a comparison of silage and grain corn treatments. The silage corn treatment, which is harvested around mid-September, allows more time for cover crop growth compared to grain corn, which comes off about a month later. In the silage corn treatment, all corn residue is removed at harvest. In the grain corn treatment, the cobs are harvested in late fall and the crop residue remains in the field.

The research team is measuring above-ground cover crop biomass at three stages: at corn harvest, at the end of the season, and at termination in the spring.

Deen provides a preliminary overview of some of the results so far. “As expected, biomass yields of the cover crops were greater following silage corn than grain corn in 2015.” In the grain corn treatments in 2015, cover crop biomass levels were low at all three locations, even though it was a very good year for establishing cover crops. “The cover crop stands looked reasonably good in mid-July; I would estimate there were 300 or 400 kilos per hectare of biomass. But in the fall there was not much more biomass.”

Since the biomass levels were low, Deen isn’t surprised the soil analyses so far are not showing any significant changes in soil properties from the 2015 cover crops.

With the dry conditions in 2016, cover crop biomass levels were very low as of early September.

Deen has been studying cover crop effects in various crop rotations for quite a few years. Based on his experiences, an interseeded cover crop in a typical grain corn-soybean rotation in Ontario

doesn’t have a strong opportunity to produce a lot of biomass.

“Our growers like to choose long-season hybrids so they use all of the season. There is little opportunity after grain corn is harvested to have sunlight and warmth available for cover crop growth. As well, the nitrogen availability after grain harvest might be limited.

“Also, a lot of our growers are switching to combine heads that mulch the corn crop, so they would have a mulched layer on top of a cover crop that is already struggling. Even if they don’t have a mulching head, corn produces a lot of residue that can smother the cover crop. And if they have a cover crop that overwinters, there may not be much opportunity for cover crop growth in the spring because a lot of our growers are increasingly planting soybeans early.”

So, Deen says, “If farmers are absolutely committed to a simple corn-soybean rotation, then by all means, try to get a cover crop into that system, but be realistic about the likely benefits.”

Planting green may be one of the ways to provide more benefit from the interseeding or even the post-corn seeding of a cover crop.

However, he advises, “If you're really serious about obtaining benefits from a cover crop, the real opportunity is to add another crop in your rotation, such as wheat. That gives a proper niche so the cover crop can produce a substantial amount of biomass. Plus the third crop in itself, as we have already demonstrated [in previous research], provides rotational benefits and soil quality benefits.”

Still, Deen is excited that farmers are continuing to explore cover crop options. For instance, he is intrigued by the “planting green” approach some growers are using. “Planting green may be one of the ways to provide more benefit from the interseeding or even the post-corn seeding of a cover crop [such as cereal rye]. In a planting green strategy, you allow the cover crop to overwinter and get some reasonable growth in the spring, then you control it on the day before or day of planting, and plant into it green. So you would have more biomass growth and perhaps some weed control benefits, although you might run into increased risks of problems like moisture depletion.”

Clark adds, “Farmers generally know their own land really well. Taking into consideration your specific context – the weather you know you get, the soil you know you have – is going to be key when you’re thinking of trying any sort of cover cropping approach on your land.”

The province offers good growing conditions, but harvesting challenges and economic realities are discouraging producers.

by Julienne Isaacs

It’s been a bad year for flax in Canada.

“Markets are suffering a bit across Canada,” says Brian Johnson, chair and director-at-large of the Flax Council of Canada.

Statistics Canada puts seeded acres for 2016 to 2017 at just over 900,000 acres across the country.

Johnson believes the reason for the drop in acreage is the huge increase in acreage in Eastern Europe over the last seven or eight years. “Flax is volatile – when the prices go up, we over-seed a bit. We have a much bigger carryover this July than last July, because prices were better last year,” Johnson says.

In Western Canada, acreage is down 40 per cent. Johnson says a big reason for the decrease is the explosion in lentil and pulse crops in Western Canada due to the shortfall in pulse production in India. “Lentils and flax are grown in the same area and basically a lot of farmers switched from flax to lentils,” he says.

But the picture in Ontario, where flax is hardly grown at all, is

relatively unchanged from the last few years. Flax acreage in the province is down to fewer than 5,000 acres, though at its peak acreage was up to 75,000 acres, according to Mike Cowbrough, weed management field crops program lead for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Cowbrough is also the organization’s de facto “flax guy” due to the fact that he grew flax on his hobby farm for a decade.

Why the lack of flax in Ontario? Conditions in the province for growing flax are good, particularly in cooler regions such as Grey and Bruce County in central Ontario, and Verner and New Liskeard in the northeast.

Cowbrough believes there are two main reasons keeping producers from planting more acres. The first is economics. “If you look at the gross revenue potential in flax and compare it to other field

ABOVE: Flax acreage in Ontario is down to fewer than 5,000 acres.

crop staples, there’s anywhere from a 100 to 400 per cent difference in gross margin.

“The other potential knock against flax is that it’s never been an easy crop to harvest and the straw is a bit of an issue,” Cowbrough says. “It’s tough, it doesn’t break down, it’s difficult to spread out. It’s beautiful to grow and wonderful to look at but a pain to combine.”

From a production standpoint, the crop performs well in terms of disease and weed concerns, Cowbrough says. The main problems Ontario producers have with flax are price stability and harvesting ease.

“It’s a great crop in Ontario for harvesting earlier than soybean, and wonderful to have in a rotation with winter wheat,” he says. “If we grew more flax, our winter wheat yields would benefit from that. But it’s agribusiness, and the economics aren’t there for flax.”

Troy Snobelen, owner of Snobelen Farms, a private grain producing, processing and trading company in Lucknow, Ont., says the company hasn’t processed flax in over a decade.

“We got out of it because we didn’t have the volumes,” he says. “We used to bring in quite a bit of it from Western Canada, but it was hard to take a western product and add value and try to ship it to a U.S. market. It was inefficient.”

This sentiment is echoed by Steve Murray, a manager at Parrish and Heimbecker – but Murray still deals in flax, primarily for Ontario’s feed market.

“Most of our flax comes from the west, although in Ontario in the last couple of years the amount has increased,” he says. “Right now, our flax is probably 95 per cent Western Canadian, five per cent Ontario. Those numbers might change but they won’t change substantially. I can’t envision a 50-50 or anything like that.”

But there are positive indications for growth in local flax production. Formerly, producers couldn’t get crop insurance on flax, so they avoided the risk, but as of a few years ago, crop insurance is available on flax across the province. Murray believes this might make a difference.

John Gleeson, a private grain processor and trader near Moorefield, Ont., says increased local production would be of

major benefit to his business. “We have big problems getting flax out west,” he says. “The railway is a joke. You can’t get rail cars for love nor money. We send our own trucks out to get flax, and we’re loading those new B-trains.”

Cowbrough says new research out of the University of Saskatchewan, funded by the Western Grains Research Foundation, will have little application in an eastern context and is unlikely to stimulate flax production in Ontario.

But the Flax Council of Canada is heavily invested in research to improve flax for food, feed and other markets – and to promote its excellent nutritional profile to stakeholders across the country.

“There’s getting to be a better and better understanding of the health benefits of flax. That information is getting out there and that part of the industry is growing,” Johnson says. “There’s a lot of work to be done, but flax has a lot of potential.”

Identifying and developing varieties suited to Eastern Canada.

by Carolyn King

Malting barley is a higher-value cereal crop that could be a good option for Eastern Canadian growers. A key factor in the successful adoption of this crop is the availability of varieties suited to the region’s growing conditions. Now a project is underway to identify which of the existing malting lines would be best for the east and to develop improved germplasm for further breeding work.

Thin-Meiw (Alek) Choo, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Ottawa, is leading the project. He notes, “Before we started this research project, we had already identified two good malting barley varieties for Eastern Canada: Cerveza and AAC Synergy. Cerveza is on the list of recommended varieties for Quebec and the Maritimes. AAC Synergy is now being tested in the registration and recommendation tests in Quebec and the Maritimes. These two varieties have performed well in Quebec, the Maritimes and New York State. They were developed by Bill Legge at AAFC’s

Brandon Research and Development Centre [in Manitoba].”

Now Choo’s project is helping to identify more and better malting varieties for Eastern Canada. Called the Eastern Canada Malting Barley Test, it runs from April 2013 to March 2018. It involves screening hundreds of advanced breeding lines and varieties from other regions to find ones with three essential traits: resistance to Fusarium head blight, resistance to lodging, and high yields under Eastern Canadian conditions.

“Resistance to Fusarium head blight is a must for successful malting barley production in Eastern Canada,” Choo says. The region’s warm, humid growing conditions favour this serious fungal disease. Fusarium head blight reduces grain yield, but more importantly it can produce mycotoxins on the grain. He notes, “The maltsters and brewers do not accept any barley

TOP: The first stage of the evaluation process is to see how hundreds of different malting barley lines perform at this Charlottetown site.

grain contaminated with mycotoxins.”

The often rainy and stormy conditions in Eastern Canada increase the risk of lodging, which can result in lower yields and poorer grain and malting quality. So Choo is looking for malting lines with shorter and stronger straw that are better able to resist lodging.

And, of course, yield is a top consideration. “Any malting barley varieties must yield well in Eastern Canada. Otherwise, producers will not grow them,” he says.

Choo’s project team is testing malting barley lines from the Prairies, where most of Canada’s malting barley is grown, and some cultivars from other countries.

“Every year, we have evaluated 23 lines from the Field Crop Development Centre of Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, 38 lines from the University of Saskatchewan, and 36 lines from the Brandon Research and Development Centre. We have also tested seven barley varieties from Argentina, seven varieties from Australia, and 21 varieties from Brazil,” he says.

The evaluation process involves several steps. “[First] we plant these barley lines at Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, and compare them with our standard varieties such as Leader

[a recommended feed barley variety] and AAC Synergy. Last year, we identified 26 of these lines as high yielding. Therefore, in 2016, we have planted these 26 lines at three locations across Eastern Canada: Charlottetown, Normandin, [Que.] and Ottawa.” This fall, they will be analyzing the results from the 2016 growing season, and they’ll continue the testing work in 2017. In the years ahead, very promising lines that have not yet been registered in Canada could be entered into the variety registration tests for Eastern Canada.

The project is only testing two-row barley lines. Choo explains, “Six-row barley is more susceptible to Fusarium head blight than two-row barley. Therefore, we do not encourage our producers to grow six-row barley for malting in Eastern Canada.”

Choo is collaborating on this research with Bill Legge, Aaron Beattie at the University of Saskatchewan, Patricia Juskiw at the Field Crop Development Centre, Denis Pageau at AAFC’s Normandin Research Farm, and Marta Izydorczyk at the Canadian Grain Commission. The project is funded by AAFC, the Alberta Barley Commission and the Atlantic Grains Council.

The project’s results will give eastern

growers more varietal choices for malting barley production. As well, Choo will be using the superior lines identified through the testing work as parents for crossing in his barley breeding program. Promising malting barley lines from his program will be sent to the Canadian Grain Commission for malting quality analysis. Eastern growers can look forward to possible further improvements in malting varieties down the road.

If growers can achieve malting quality with barley produced in Eastern Canada, it could potentially be a very good opportunity. “Malting barley typically has a higher value than barley grown for livestock, for example. So it would be a value-added proposition for growers,” says Neil Campbell, general manager of the PEI Grain Elevators Corporation.

“I’m not sure what the potential is for malting barley production in Atlantic Canada, but it could be quite substantial because the [craft malt and brewery] business has exploded here in the Maritimes in the last three or four years. Nova Scotia alone has 40 different local breweries that use malting barley and other grains,” Campbell says.

He also points out that, in addition to Choo’s work, other malting barley research is underway in the Maritimes. For example, Aaron Mills at AAFC in Charlottetown is developing recommendations for malting barley agronomic practices and is testing modern and heritage malting varieties in Eastern Canadian conditions.

Campbell also notes the combined sales of Canadian malting barley and malt are worth about $1 billion per year. “So if the Atlantic provinces could even get one per cent of that, it’s a nice little number!”

by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

In recent years, Ontario farms have increasingly become two-crop operations, alternating corn and soybean with the occasional rotation of winter wheat. However, research shows the corn-soybean rotation has a number of downfalls, including the lowest soil organic matter, less success with no-till practices, a need for more inputs, increased greenhouse gas emission and less opportunity to incorporate cover crops. It is also associated with reduced yield, input use efficiency and system resiliency.

“Farmers feel corn and soybean is the most profitable rotation,” says Bill Deen, an associate professor at the University of Guelph. “We need to convince them that winter wheat is worth keeping in the rotation and that there are benefits associated with more diversity.”

To help convince them, Deen is leading a research project evaluating the effects rotation complexity has on yield stability under moisture extremes. The project is co-funded by the Grain Farmers of Ontario, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Loblaw Operating Fund.

The researchers are using data collected from long-term trials initiated in 1980 in Ridgetown, Ont., and Elora, Ont., which involved rotations with single to three crops plus a cover crop with tillage and no-till. Those studies show crop diversity increases the probability of a high yield and reduces the probability of a low yield.

“If you use a more diverse rotation, corn yield goes up five to six per cent in Ridgetown and Elora,” Deen says. “If you add wheat into the corn-soybean rotation, the bigger effect is on soybean yield. It goes up 13 or 14 per cent. That’s the benefit of wheat.”

Deen and his team were specifically interested in how rotation complexity in tillage and no-till systems alters the amount of soil water available to plants, the corn and soybean’s abilities to use water resources and the effect all of this has on yields under

ABOVE: Corn plots with drought treatments during a University of Guelph study looking at diverse rotations for improved resiliency in drought conditions.

imposed drought stress. Using the data from the long-term rotation/tillage trial established in 1980 at the Elora research station, they discovered that although rotation diversity provides benefits in years with above-average rainfall, the benefit is much greater in dry years.

“We’ve proved that with good rotations you get more stable yields and improved resiliency in drought conditions, particularly after forage,” Deen says. “There is a

direct relationship between grain yield and transpiration: higher yield requires more water. Diverse rotations reduce the likelihood of drought stress particularly when yield potential is high.”

Climate change could accentuate drought effects in the future. “Climate change, higher yields, biomass removal could all accentuate the problem of drought stress,” Deen says. “We need crop rotation to minimize that stress.”

The researchers are confident this research will do just that by helping to identify management practices instrumental to adapting Ontario’s most abundant cropping system to changes in climate, as well as to improve productivity and water-use efficiencies under an increasingly challenging environment.

“Good soil health is difficult to achieve when you’re using a simple corn-soybean rotation,” Deen says. “If you’re serious about soil health and increased yields, it is important to consider increasing rotation diversity.”

For the past year and a half, Deen and his team have been working towards determining what mechanisms enable complex rotations to have more drought tolerance.

“Why do diverse crop rotations have better resiliency?” Deen asks. “Is it because the soil retains a higher percentage of rainfall? Or is it greater water holding capacity due to improved soil health? Or maybe it is due to crops under diverse rotations have better rooting ability.”

Deen’s team has completed the first year of work imposing drought, irrigated and ambient conditions to specific rotations to look at soil properties and various aspects of plant growth such as water content, water holding capacity, plant transpiration and root morphology. They are now putting the data together to see if future study is needed, and expect results over the next year.

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. These products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from these products can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for these products. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, an active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup Ready 2 Xtend™ soybeans contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate and dicamba. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate, and those containing dicamba will kill crops that are not tolerant to dicamba. Contact your Monsanto dealer or call the Monsanto technical support line at 1-800-667-4944 for recommended Roundup Ready ® Xtend Crop System weed control programs. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for canola contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil and thiamethoxam. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for canola plus Vibrance ® is a combination of two separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, thiamethoxam, and sedaxane. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individuallyregistered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin and ipconazole. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn with Poncho ®/VoTivo™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-1582. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Acceleron®, Cell-Tech™, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity ® JumpStart ®, Optimize ®, RIB Complete ®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design®, Roundup Ready 2 Xtend™, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready ®, Roundup Transorb ®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup Xtend™, Roundup ®, SmartStax®, TagTeam®, Transorb ®, VaporGrip ®, VT Double PRO ® VT Triple PRO ® and XtendiMax ® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. Fortenza® and Vibrance ® are registered trademarks of a Syngenta

Lowering seeding rate when planting at a later seeding date can improve stand establishment – even in bad years.

by Julienne Isaacs

According to Joanna Follings, cereals specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) based in Stratford, Ont., stand establishment problems in winter wheat tend to happen depending on the year.

In 2015, Ontario producers saw excellent fall conditions for planting, and most got their crop in early, so plants were well established going into the winter.

In 2014, producers weren’t so lucky: a wet fall meant delayed planting, and to make matters worse it was followed by a cold winter. Many producers experienced problems with winter survival.

“It can be a challenge for growers to get out in to the field in a timely manner,” Follings says.

Peter Johnson, an agronomist with Real Agriculture, is currently working on studies examining the impact of soil type, seeding rates and seeding dates on stand establishment.

“Typically here in Ontario we get about 70 per cent stand establishment,” Johnson says. “We get higher levels if we seed earlier into excellent conditions. Last year we were getting fields with 85 per cent stand establishment, but typically we seed under less than ideal conditions.”

There’s a growing body of research pointing to agronomic methods that can improve stand establishment in winter wheat even in bad years, Johnson says. This year, he and technician Shane McClure wrapped up a three-year “seeding rate by seeding date” interaction study, and the data should be available soon.

But Johnson says it’s clear that the earlier producers seed, the lower their seeding rate can be. The later they seed, the higher the seeding rate should be in order to maximize sunlight interception.

“We seed ultra early, two weeks prior to the recommended date, and at that stage we recommend decreasing seeding rate by 25 per cent,” Johnson says. “Our normal target is about 1.5 million seeds per acre, and when we seed two weeks ahead of optimum date, we can drop that to 1.2 million seeds quite easily, with no impact on yield.” On heavy clay soils, he recommends starting at 1.8 million seeds per acre and adjusting seeding rates according to date from there.

“Once you’ve moved past optimum seeding date, my standard recommendation is to increase seeding populations 100,000 plants

Optimum winter wheat planting dates vary by region, ranging from mid-September to early October, according to OMAFRA cereals specialist Joanna Follings.

per acre for every five days past that optimum date.”

In areas prone to heavy snow loads, snow mould infestations are much more severe with early seeding dates and high seeding rates.

“Lodging concerns increase when growers seed heavy seeding rates early,” Johnson says. “But with highest wheat yields coming from early seeding dates, seeding early at lower seeding rates just makes sense.”

When seeding into ideal fall conditions, Peter Johnson says Ontario winter wheat growers should see about 70 per cent stand establishment.

This year, Kelly Turkington, a pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Lacombe Research and Development Centre in Lacombe, Alta., and Brian Beres, an agronomist with AAFC’s Lethbridge Research and Development Centre in Lethbridge, Alta., published new research pointing to the effectiveness of seed treatments used in tandem with appropriate sowing density to overcome poor stand

establishment in winter wheat.

In one study, Beres and Turkington argue seed treatments are best used to offset weak, low-yielding systems.

If producers are starting with high quality seed with good germination rates, good vigour and low levels of pathogen infection, and they’re putting seed into a system with good seed-to-soil contact and using appropriate seeding rates, Turkington says the impact of seed treatments will be limited.

Joanna Follings, cereals specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), says there are five rules of thumb for producers looking to improve stand establishment in winter wheat.

Variety selection: Producers should plant varieties that are suitable for the region. The Ontario Cereal Crop Committee publishes an annual report (http://www.gocereals.ca/2015_ WW_Public_Sept13v1.pdf) with data from its winter wheat performance trials that includes information on the highest yielding varieties in each region over a five-year period.

Seed quality and seed treatments: “Plant seeds that have good germination and vigour,” Follings says. “Don’t plant seeds that are damaged. Fungicidal seed treatments provide protection to vulnerable seedlings.”

“Where we’ve seen seed treatments are a real benefit is when seed-borne disease, diseases that will impact germination, seedling growth or stand establishment, or diseases like smuts, are present in a field,” he says.

Turkington’s work was all done in Western Canada, but Johnson says similar results have been seen in Eastern Canada.

“If you’re seeding into ideal conditions from a stand establishment point of view with no disease pressure, you may not see the benefit of seed treatments,” he echoes. “But if you get bunt in your wheat crop, that’s 100 per cent crop loss. For $3 per acre of seed treatment, or even $5 per acre, whatever that premium is, we can’t afford to take that risk.”

Johnson recommends every producer use a good fungicide seed treatment. Insecticide on the seed isn’t needed everywhere, but is more regionally isolated according to soil type and insect pressure. But he feels fungicide seed treatments are essential, even though they don’t always increase yield. “If I get dwarf bunt or common bunt in the crop, the grain comes out of the field smelling like rotten fish. The industry simply won’t accept it. That risk is simply too high,” he says.

“In terms of stand establishment, we see a benefit in stand establishment if you apply a fungicidal seed treatment under adverse conditions.”

For more seeding strategies, visit topcropmanager.com.

Rate: The general rule is 1.5 million seeds per acre, but look up the recommended rate for each variety.

Depth: Seeds should be planted at a uniform depth of 2.5 centimetres, or one inch, to encourage early emergence and development of a secondary root system. “This doesn’t vary by area,” Follings says. “What varies in terms of depth is that moisture trumps the one inch rule – you need to plant into moisture.”

Timing: “It’s a 1.1 bushel per acre per day decrease in yield for each day that cereal planting is delayed beyond optimum timing,” Follings says. Optimum planting dates vary by region, ranging from mid-September to early October.

Seed corn maggots struck some south-central Ontario soybean acres hard this year.

by Madeleine Baerg

Seed corn maggots took a costly bite out of many southcentral Ontario soybean fields this spring. In Wellington County, some fields were decimated to the point of needing complete replanting. While seed corn maggots are not a new problem, their unpredictable occurrence, limited control options and sometimes devastating consequences make them a major and costly headache for producers.

“Are seed corn maggots the kind of pest that wipes out 50 per cent of Ontario’s soybean acreage? No. The overall per cent is relatively small. But, if you are a grower that gets hit with maggots, it’s very significant and very costly for you,” says Horst Bohner, soybean specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Seed corn maggots are small, light yellow maggots that feed on germinating soybean and corn seeds. Because adult flies will only lay eggs in moist, rotting vegetation and larvae need time to do maximum feeding, seed corn maggots are most damaging in cool, wet, slow springs.

Most outbreaks tend to be fairly regional. That said, predicting an outbreak remains extremely difficult.

“The biggest problem with predicting when seed corn maggots will be a problem is that we don’t have a handle on when there will be large numbers of adults. We understand that if seed comes out of ground slowly there is more time for larvae to feed. But why there were a large number of females at one time in a specific region this year, I don’t think anyone knows that. So many of these insects just cycle,” Bohner says.

Once seed corn maggots hit a crop, there is not much a farmer can do but wait to assess damage. Seed corn maggots are difficult to counter because it is virtually impossible to scout for adult flies, and there are no post-seeding pesticide treatment options.

While seed treatments tend to be effective against the larvae, gaining approval for their use can prove to be a chicken or egg scenario: to be approved, one must prove damage has caused a loss of 30 per cent or more of the stand. However, once need is identified it is much too late to counter the maggots and the benefits of a neonicotinoid treatment can only be seen in a replant.

One maggot countermeasure every producer should follow is prioritizing speedy germination and seedling emergence, Bohner says.

“Think about proper planting depth, good seeding timing, adequate nutrition and disease management, good residue control. You want to do everything you can to get that seed out of the ground as fast as possible.”

Like many flies, adult seed corn flies are attracted to the odour of decay. Seed corn flies lay their eggs in freshly tilled

soil, decaying crop residues, and manured fields. As such, farmers concerned about seed corn maggot infestation may want to consider no-till management. At the very least, farmers should seriously consider opting not to till under cover crops or manure within three weeks prior to seeding.

Farmers who suspect seed corn maggot infestation in their fields should look for widespread and fairly consistent damage across the field, rather than patchy or localized damage. Then, dig up seed to look for obvious physical damage and/or the telltale yellow maggots.

Because the seed corn maggot’s entire lifecycle can occur in as little as three weeks, be aware that a new generation of maggots may be primed and waiting for a second planting of seeds. If seed corn maggots are verified in a field and damage warrants a replanting, consider planting insecticide-treated seed.

It is very difficult to estimate the cost of damage inflicted by seed corn maggots on Ontario fields.

“What typically happens in Ontario is that we have considerable acreage that needs to be reseeded each year, but it’s hard to always know why it needs reseeding. It could be soil borne diseases, insects, cold stress, soil crusting. More often than not, it’s a combination of factors. Seed corn maggots are just part of the overall picture. Replanting costs money and reduces yield potential, but calculating exactly how much of that is due to seed corn maggot is almost impossible,” Bohner says.

“But, I’ll tell you this,” he adds. “Seed corn maggots are frustrating and they are costly. I’ve been doing soybean trials for 15 years. This year, we had a large experiment completely wiped out because of seed corn maggots. So I do know exactly what the farmer goes through when he sees his hard work destroyed by a hard-tomanage pest like seed corn maggot.”

YOU’VE

For 20 years, we’ve left the competition with some pretty big tracks to fill. But in the rush to keep up, there are a few things the copies have missed. Like our exclusive five-axle design. It gives our Steiger ® Quadtrac,® Steiger Rowtrac™ and Magnum™ Rowtrac tractors a smoother ride and more power to the ground with less berming and compaction. Which is one of the advantages of paying your dues, instead of paying homage. Learn more at caseih.com/tracks