TOP CROP MANAGER

Manure: Black gold

Maximizing benefits while minimizing harm

PG. 5

Managing Tough Weeds

Glyphosate resistance poses a special challenge

PG. 26

unlocking soyB ean synergies

Multiple inputs boost yields PG. 7

Maximizing benefits while minimizing harm

PG. 5

Glyphosate resistance poses a special challenge

PG. 26

unlocking soyB ean synergies

Multiple inputs boost yields PG. 7

By Madeleine Baerg

Dr. Rob Mikkelsen

By Treena Hein

Carolyn King

16 | Alternative corn N applications Best practices for side dressing using sprayers into standing corn.

By Treena Hein

Donna Fleury P

Lianne Appleby, Associate Editor

By Blair Andrews WEE

LIANNE APPLEBY | ASSOCIATE EDITOR

As some of you will know, Stefanie Croley is now on maternity leave after welcoming a healthy little boy, Silas allan, in the early hours of September 28. Mom and baby are doing just fine.

Having been asked to “hold the fort” until her return a year from now, I’ll be working with Janet Kanters to continue to bring you the research and technology information you’ve come to expect from this magazine.

one of the first things I did when I found out I would be joining the Top Crop Manager team was to find as many back-issues as I could get my hands on. When I had a spare five or 10 minutes, I’d read articles over a cup of coffee, scan ads and try to wrap my head around relevant industry issues. Let’s face it – every industry has them. What’s important, though, is that those issues are acknowledged and that work is being done to improve what can be improved.

What I realized, in doing my homework, is that our readers must truly embrace change and progress or the magazine simply wouldn’t exist. The fundamental mission of Top Crop Manager is one of continual learning – of innovation, new technology, ideas and growth as an industry.

Take, for example, the fact that as yields increase, crop rotations have become shorter, leading to nutrient deficiencies in soybeans in ontario. This problem has been recognized and not only is research being done, but it is collaborative. Industry and government have come together to figure out what can be done.

The idea of preventative medicine (preventing health problems before they happen instead of curing sickness) isn’t just limited to humans and animals. now, it’s also considered relevant in plant agriculture. Studies are being done to better understand how crop nutrition can be linked to – and prevent – pest problems.

Work doesn’t focus on the plants themselves either. researchers are looking at soil stressors and how taking care of the earth – literally – can help producers to make more informed decisions at the farm level, and ultimately be better stewards.

george Bernard Shaw is probably one of the most quotable men in history, and aside from his thoughts on false knowledge, he is credited with the revelation that “Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.”

I’d have to agree. I look forward to working with and for such innovative thinkers.

Lianne (Lia) appleby will serve as associate editor of Top Crop Manager (eastern edition) while Stefanie Croley is on maternity leave. Lia also currently serves as Digital editor –agannex.

Lia comes to the magazine having served as editor of Top Crop Manager’s sister publication, Canadian Poultry. previous to coming to annex Business Media, Lia worked in public relations for a global animal breeding company. prior to that, she worked for Beef Farmers of ontario, where she served as editor of Ontario Beef magazine. She began her career with Chicken Farmers of ontario.

Lia holds a B.Sc. and M.Sc. in poultry nutrition from the University of guelph. She is looking forward to immersing herself in the world of plant agriculture and learning more about the industry. She lives north of Fergus, ont.

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 RETuRN uNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCuLATION DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIRCuLATION email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SuBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West - 9 issues - February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

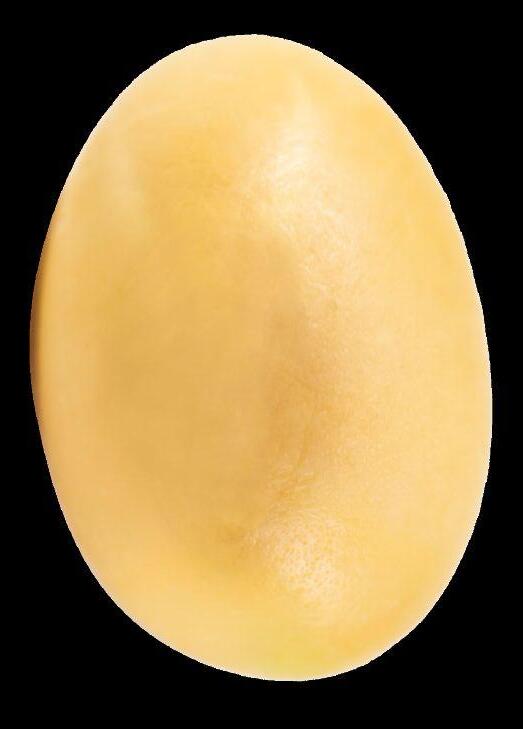

Potatoes in Canada - 4 issues - Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter 1 Year - $16 CDN plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industryrelated groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2014 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication. www.topcropmanager.com

Maximizing benefits while minimizing harm.

by Madeleine Baerg

The T-shirt for sale in a coffee shop near Dr. Shabtai Bittman’s office in agassiz, British Columbia, reads: “Welcome to manure country. You won’t forget our dairy air.” Though the smell associated with using livestock waste on crop fields is less than appealing, there’s a reason farmers who have easy access to swine, chicken and cattle manure consider it “black gold.” That said, maximizing the accessibility of manure’s nutrients to crops while minimizing its environmental downsides is not as simple as spreading it and forgetting it.

enter Bittman and his colleague, Derek Hunt, researchers with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC), whose innovative manure application methods are designed to get the most benefit and least harm from nature’s nutrient recycling.

“everyone recognizes that there are many attributes to manure that are beneficial for crop use. But, at the same time, it is not an easy fit, not a perfect fit. In addition to it being bulky, hard to transport and obviously smelly, there are aspects inherent to manure that make it more difficult to use than commercial fertilizer, both because of the form of the nutrients and their concentration,” explains Bittman.

The biggest challenge with using manure as fertilizer is the fact that the ratio of nutrients is not ideal. Most crops need a nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio of between eight- and 10-to-one.

Typical liquid manure from swine or dairy operations is generally in the range of three- or four-to-one. as such, if one applies this manure in a quantity to get the right amount of nitrogen, the crop will receive far too much phosphorus.

over-applying phosphorus is a very big problem environmentally. When phosphorus enters a water system it can cause a rapid increase in the amount of algae present: a deadly process called eutrophication. When the algae dies and sinks, the bacteria that decompose it use up all the oxygen in the deepest parts of lakes, making these formerly rich habitats unable to support life.

“eutrophication is contamination you can see: the lakes turn greeny-brown and murky; the beaches get covered in slimy, rotting algae,” says Bittman. “The element limiting algae in water is phosphorus, not nitrogen, so added phosphorus can cause a devastating algae bloom.”

“We’re seeing it most prominently in Lake Winnipeg, but it’s also a major issue in the great Lakes, especially in Lake erie, in the Mississippi Delta, most major water bodies that are close to agriculture and close to urban centers, especially ones that still allow people to fertilize with phosphorus-containing fertilizers.”

Two options exist to ensure manure applied to crops does not contain far too much phosphorus. The first is to apply less

manure and add a commercial fertilizer to bulk up the nitrogen: a less than ideal solution when manure is free or cheap.

The second – Bittman and Hunt’s field of study – is to manipulate the nitrogen and phosphorus components of manure. This manipulation is surprisingly easy, since the concentration of nutrients varies widely based on the thickness of the manure itself: left to naturally settle, the more solid portion has a two- or three-to-one ratio of nitrogen to phosphorus, while the liquid portion is in the seven- or eight-to-one range, near ideal for most crops.

after reviewing multiple trials of various manure separating technologies, Bittman and Hunt’s team determined filtration systems, no matter how hightech, are unable to effectively filter tiny phosphorus particles. rather, the best, most cost-effective separating system is ultra-low tech: nothing more than a holding tank or waste lagoon system that allows settling of solids and decanting of liquids.

The liquid portion can be applied directly to the majority of crops, including hay crops where the nitrogen recovery is superior to raw manure. But the thicker, phosphorus rich sludge is certainly not a useless waste product, Bittman and Hunt’s research shows.

a corn crop requires a very high level of phosphorus very early in the growing season. even in phosphorus rich soils, corn farmers typically apply 25 to 30 pounds of commercial, granular phosphorus per acre near the seed at planting because tiny corn seedlings require immediate access to a ready supply of this nutrient.

Top dressing a corn crop with manure is too unwieldy, too wet, and not located close enough to a corn seed to be effective. However, Bittman and Hunt’s research shows that a thicker, sludgier, phosphorus heavy manure injected at corn row spacing solves all of the operational challenges and provides 100 per cent of the phosphorus required by young corn seedlings.

“even though the sludge is thicker than the component you’ve decanted off, it’s still 93 per cent water. What we found is if you inject it with a commercial injector at the same spacing as you’ll plant (2.5 feet or 75 cms), then let it soak in for a couple days so it’s not too sticky, and then plant the corn as close as you can to the manure

band, you’ll get the best response from the corn,” he explains.

“For this method of concentrating the phosphorus in manure and then injecting it for corn crops, we are first in the world doing it as far as I know. We’ve had a lot of interest from (researchers in) other

parts of the world,” he says. Injecting manure into the soil also solves a second challenge of manure application. When manure is top–dressed onto crop fields, the ammonium

by Carolyn King

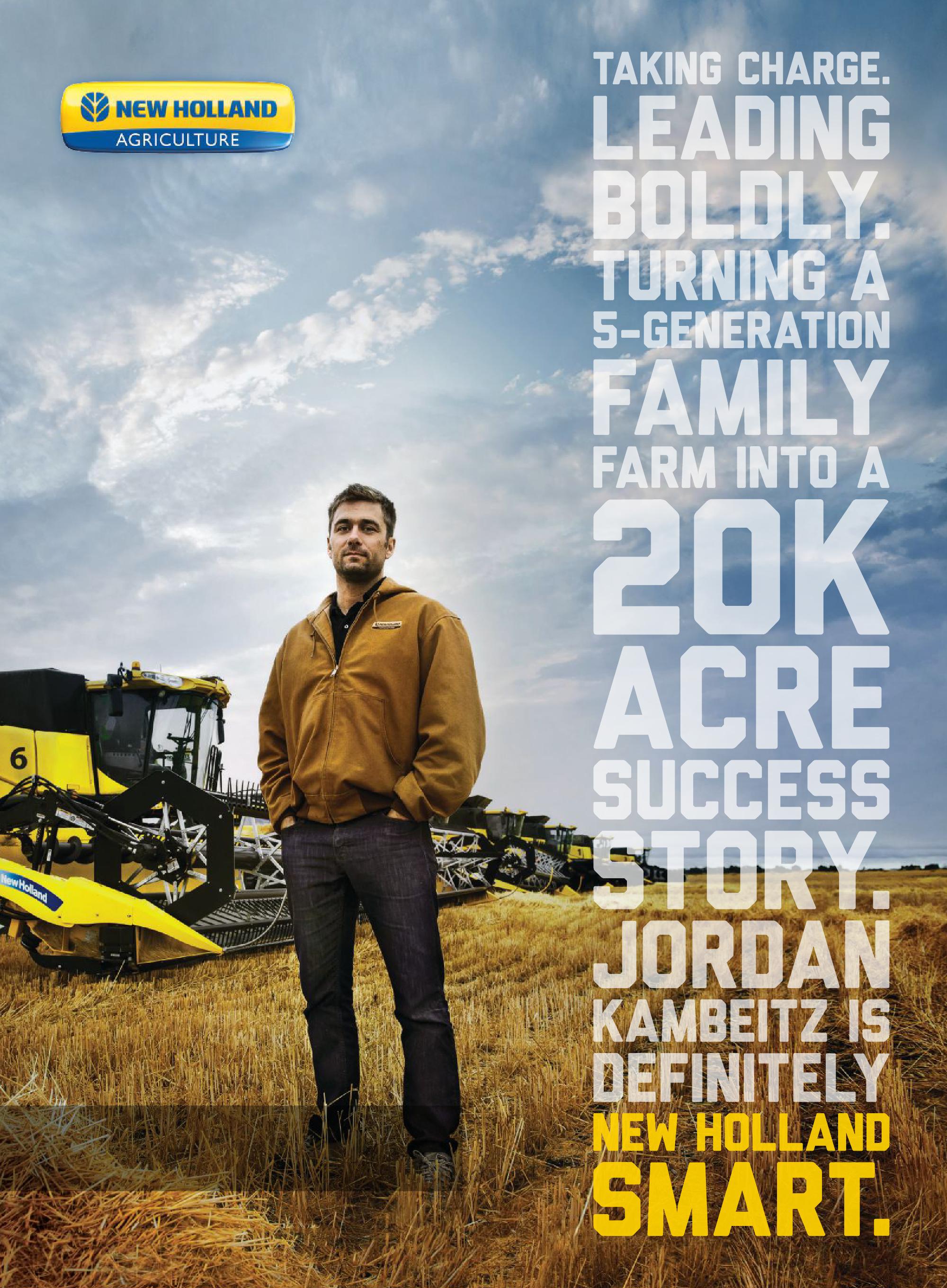

Arecently completed project shows that applying a whole suite of inputs can boost soybean yields consistently. now the challenge is to refine this approach so the economics work.

The project’s aim was to investigate interactions and synergies among popular crop inputs for soybeans. “Individual inputs have been tested for many years to assess when and where it makes sense to apply fertilizer or seed treatments or fungicides or what have you to soybeans. But there hadn’t been an extensive study to try to pull everything together in a management system to see if there would be some synergy from applying multiple inputs,” explains Horst Bohner, soybean specialist with the o ntario Ministry of a griculture, Food and rural affairs ( o M a F ra ).

“So, if you get one or two or even three extra bushels per acre from an individual input, then what does it add up to if you apply all the inputs? In other words, does 1 + 1 = 2, or 3, or 1 in terms of extra bushels per acre?”

Called SM arT2, the project was a follow-up to the earlier

SM arT (Strategic Management adding revenue Today) studies about management of soybeans and wheat. The SM arT 2 soybean project ran from 2011 to 2013 and involved field-scale trials led by Bohner and small plot trials led by Dr. Dave Hooker from the University of g uelph- ridgetown.

The field-scale trials were conducted at 15 locations across o ntario in a wide range of Crop Heat Unit (CHU) zones. at each site, the researchers compared an adapted variety for the area to a long-season variety that required about 200 CHUs more than recommended for the area. For both varieties, they compared untreated soybeans to soybeans treated with the “Kitchen Sink.”

The Kitchen Sink treatment package included: CruiserMaxx seed treatment, HiCoat inoculant, Quilt foliar fungicide, high seeding rate (250,000 seeds/acre), 50 pounds/acre of nitrogen

aBOVE: The “Kitchen sink” treatment (right) boosted yields by about five bu/ac for the adapted varieties and seven bu/ac for the long-season varieties, compared to the untreated soybeans (left).

( e S n and ammonium sulphate) at planting time, three gallons per acre of 2-20-18 liquid fertilizer applied infurrow, six litres per acre of slow-release nitrogen and two litres per acre of 3-1616 foliar fertilizers.

The small plot trials, located at ridgetown and e xeter, compared most input intensities for three inputs –foliar fungicide, nitrogen fertilizer at planting time and foliar fertilizers – at normal versus high seeding rates. all of those treatments were evaluated for four adapted and four long-season varieties at each location.

g rain Farmers of o ntario ( g F o ), the a gricultural adaptation Council ( aaC), Syngenta and the o ntario Seed g rowers a ssociation were the major sponsors of the project, John Deere provided access to tractors and a sprayer and the co-operating producers loaned their time. Kevin robson acquired his MSc degree through the small plot research.

The field-scale results show the Kitchen Sink treatment is an effective way to increase soybean yields, but the yield increase is not sufficient to cover the Kitchen Sink’s total cost of $140/acre.

“In every case, we had higher yields where we threw the Kitchen Sink at soybeans. So soybeans do respond very nicely to a whole suite of inputs. The Kitchen Sink approach gave us about 5 bushels per acre extra in yield; and seven bushels per acre if you include the strategy of growing a longer-season variety. Those are very nice numbers in the soybean world,” says Bohner.

In the field-scale trials, on average, an extra two bushels per acre was achieved simply by growing the long-season variety rather than the adapted one. Since this practice involves no extra cost, Bohner says it’s a good way to increase yields and profits.

He notes, “o n average, choosing a variety that takes advantage of the whole growing season, or as much of it as possible, will provide more yield. But there are more factors to consider than just the maturity whenever you compare varieties. You might choose a longer maturing bean that yields less just because of the genetics… so the longermaturing bean has to be genetically capable of producing more yield.”

TABLE: 1. Soybean yields by management and variety maturity, small plot trials, 2011 to 2013

* Normal management = 165,000 seeds/ac, no fungicide, no fertilizer nitrogen

** Intensive management = 250,000 seeds/ac, foliar fungicide, nitrogen fertilizer at planting

The plot trials produced similar results to the field-scale trials. The intensive package significantly increased yields of both the adapted and long-season varieties, on average (see table 1).

Hooker notes, “growing a long-season variety provided a yield gain of about four bushels per acre compared to the adapted variety. Then, with our intensive package, the long-season variety yielded an additional three to five bushels per acre.”

Interestingly, the plot trials also showed tremendous differences in yield responses among the 16 soybean varieties (see graph 1). “Some varieties had no yield increase in response to the intensive treatment package, whereas others produced up to 10 bushels per acre extra,” says Hooker. “So we know that genetics interacts quite strongly with management.”

He analysed the small plot data to determine the relative importance of the inputs. “We found that 50 pounds per acre of nitrogen applied at planting gave only a 0.1-bushel per acre yield response,

on average, but it cost about $50 per acre. So it wasn’t an important input whatsoever,” he says.

“applying a foliar fungicide gave about one bushel per acre response, which is lower than what we would have expected based on other foliar fungicide experiments.

“However, the combination of a foliar fungicide and a plant population about 50 per cent higher than recommended gave a significant yield improvement of 3.6 bushels per acre [on average]. So there was a synergistic reaction.”

according to Hooker, the fungicideplant population synergy could be due to a couple of factors. “There’s more disease pressure in a canopy of a higher plant population, so the fungicide is helping to control disease. also, each plant, because it’s in a high plant population, is under a little more stress, and some studies have shown that fungicides may help a plant cope with some moderate stress.”

The synergy didn’t occur on every soybean variety. Hooker explains, Soybean yield (bu/ac)

Our innovations do more than solve everyday problems – they maximize output while saving your operation money. That’s why Case IH continues to innovate with proven, efficient and reliable solutions. Be ready with innovations like the Axial-Flow ® rotor that started the rotary combine revolution; Quadtrac® technology that gives you less compaction and better traction; Advanced Farming Systems – a less complex precision farming solution; and an SCR-only emissions solution that gives you more power with less fuel. To learn more, visit your local dealer or caseih.com.

“It seems to work only on varieties that stand well or are more responsive to high plant populations.” He says high plant populations are not a good practice for tall varieties that lodge easily, which in this study occurred mainly in long-season varieties or where nitrogen fertilizer was applied at planting. a lower than normal population may be better in conditions that tend to produce full canopy closure by full flowering (the r 2 stage of soybean growth). results from the small plot and field-scale trials underlined the fact that lodging can increase the risk for white mould and harvesting problems.

There was no yield response to the foliar fertilizers, which were applied between the r 3 (beginning pod) to r 4 (full pod) soybean stages, the timing recommended by industry.

Hooker and Bohner have some ideas about how to make intensive management of soybeans more economically viable.

For instance, Hooker is currently exploring the timing of foliar fungicide applications and mixing of foliar fertilizers with the foliar fungicide. The timing trials are providing some intriguing results that could help with the economics.

He explains that fungicide companies have recommended applying foliar fungicides between the r 3 to r 4 stages, based on research conducted mainly in the U.S. However, in several recent o ntario trials, Hooker and his collaborators have been finding that r 2 to r 3 timing raises yields by about one to 1.5 bushels per acre compared to the r 3 to r 4 timing.

“That result is very significant because we would only expect about two bushels per acre in response to a foliar fungicide. So if we can get another one to 1.5 bushels, then a fungicide application would be much more economical, which would make fungicides an important piece in the intensive package,” says Hooker.

Similarly, other recent trials have shown yield responses to foliar fertilizers applied between r 2 and r 3. and the timing effect of foliar fungicides plus foliar fertilizers was detected in some 2013 experiments. Hooker is verifying those results in 2014.

g etting a better understanding of varietal differences in response to inputs would be valuable, too. Bohner

GRAPH: 1. Soybean yield responses by variety to management practices, at Ridgetown, 2011 to 2013

Normal = 165,000 plants/ac, no foliar fungicide, no fertilizer N

Intensive = 250,000 plants/ac + foliar fungicide + 50lbs. fertilizer N/ac

* = statistically different @ p=0.05

notes, “When it comes to the approach of throwing everything at soybeans, we do not have at this time a way to predict which varieties will really respond. We’re trying to see if there is a genetic component to that, but I’m not sure we’ll have the answer any time soon.”

Variable-rate input application could also improve the economics of intensive management. “Some parts of a field will respond much more than other parts of the field to inputs. For instance, a part of a field that is very lush in growth with high fertility may respond better to a fungicide. and a poor part of the field that grows short plants and has a hard time in producing a lot of yield will probably respond much better to a higher seeding rate,” explains Bohner. “So using variable-rate application might reduce input costs. If you only apply the inputs on, for example, the 50 per cent of the field that really responds to them, then you are already in an economically viable situation with the package that we have here.”

Hooker adds, “We know [from our research] that a site-specific approach to treatment application works in wheat, and we have similar projects ongoing in corn. I think this type of research needs to be done to move the yield bar ahead

in soybeans.”

Bohner and Hooker hope to get funding for some variable-rate management soybean research in the near future to look into questions like how different soybean varieties vary in their response to various inputs across a field, what are the underlying reasons why certain parts of field have higher yield responses, and how to determine where to apply different inputs.

Bohner is also trying a very different approach to get greater yields. “We’ve shown that making the plant as happy as possible – for instance, applying fungicide if there’s disease, or fertilizer if there’s a nutrient deficiency – will produce more yield very consistently, but the yield increase is not as much as we would like,” he explains. “I’m now pursuing an entirely different strategy with some of my research. I’m trying to figure out how to get the plant to retain more of the flowers and pods that it already sets and to bring those to yield.”

He thinks this approach might work because the soybean plant over-flowers so much. “In a 40-bushel crop, perhaps 50 to 70 per cent of the flowers never mature all the way through to seed.

Resistant and hard-to-control weeds impact the way you farm, your yields, your bottom line. They impact your future.

Introducing Enlist™ — a new weed control system featuring Enlist Duo™ herbicide plus innovative traits that provide tolerance in Enlist corn and soybeans. It’s a highly effective solution to modern weed control challenges.

Only Enlist Duo™ herbicide, featuring Colex-D™ Technology, includes glyphosate and 2,4-D choline for exceptional performance on hard-to-control weeds plus two modes of action for superior resistance management.

It’s protection of what’s important – plus advanced flexibility, convenience and drift control.

To learn more, call the Solutions Centre at 1-800-667-3852. Dowagro.ca

e ither the flowers are aborted or the pods are aborted early on. So the question is, how can we get the plant to retain more of those flowers and pods through to final yield?”

Bohner is trying all sorts of things to trick the plant into responding with greater pod set and retention. “ part of it may be to make the plant happy, but part of it is to stress the plant at the right time, for instance, using different growth hormones, applying herbicides, even some cutting of the plant and multiple passes of different compounds.”

For now

although there is more to learn about ways to increase soybean yields and profits, the SMarT 2 trials and other studies by Bohner and Hooker have confirmed several key practices that would increase yields for many ontario growers.

“We know potassium is lacking in about 20 per cent of ontario soybean fields. So applying potash to increase the soil test to a minimum level for soybean production would significantly increase yields. That is probably the biggest thing. In 2014 many fields had significant lodging issues. one of the reasons for this is insufficient soil potassium levels,” says Bohner.

“proper variety selection for a specific field – matching the genetic capability of a variety and its package of disease and insect resistance or tolerance to the specific field – would be

another big step forward.

“and the third is planting early, within reason, for the specific CHU zone, and marrying that with a longer-maturing soybean.”

Hooker adds, “The crop rotation work we’ve done so far has shown that having wheat in the rotation can increase soybean yields between four and six bushels per acre. That’s with no extra inputs in the soybeans. So crop rotation is even more important than all of these inputs we’ve looked at in SMarT 2.”

For more on crop management, visit www.topcropmanager.com

canada’s Source of crop Production & Technology available online www.AgAnnex.com

CONTiNuEd FROM PaGE 6

(plant available nitrogen) is prone to volatilization–turning into gas–and dissipating into the atmosphere, both reducing the usable nitrogen in the soil and causing an environmental nightmare. Called the n itrogen Cascade, a single molecule of ammonium that vaporizes into ammonia gas will have complex and long-term environmental consequences: it will be directly toxic to plants that it contacts, can attach to fine particles in the air and become an air quality issue, will fall to the ground with rain and cause acidification, can convert to nitrous oxide, and may run off into rivers and streams, contaminating watercourses.

Bittman and Hunt’s trials show that liquid manure injected into soil has a lower likelihood of volatilization because the negatively charged soil ions bonds with the positively charged ammonium ions, effectively “sticking” the nitrogen to the soil.

While this research is promising, he knows more work is necessary.

“With any new technology, you have to be careful that though you might be making one thing better, you’re not also making something else worse,” says Bittman. “ every improvement is incremental. You have to figure out how to minimize issues; to make improvements that are practical and that don’t cause additional problems.

For example, when manure is injected into soil, the narrow band of manure creates an ideal wet, anaerobic condition for nitrous oxide release as well as the leaching of nitrate

into ground water. While his research suggests the problem is minimized by injecting the sludge over injecting whole manure, Bittman continues to look for creative ways to reduce the secondary environmental effects. In Denmark, he says, farmers have begun to apply sulphuric acid to manure in the barns, in storage, and / or in manure applicators to lower the pH of manure, thereby making it less prone to change from (solid) ammonium to (gaseous) ammonia.

“In Denmark, if you have 50 pigs and you want 60 pigs, you cannot increase total emissions, so you have to introduce measures on your farm to reduce average emissions per pig. They are very aggressive about it there, and it’s certainly something for us to keep our eyes on, based on the rate of success they’ve had.”

Bittman hopes research funding is renewed so the team may continue this work beyond 2015. Currently, one farmer has begun on-farm testing of the technique.

“Like anything else, you have to see if it catches on; see if it works on farm as well as it has in our plots. Sometimes, you know right away that people won’t get past certain hurdles, be they cost, equipment, time, etc. But in this case, there are no obvious impediments to doing this on farm. So far, so good.”

For more on fertility and nutrients, visit www.topcropmanager.com

Field

View detailed coverage maps as they are completed in the field.

Rainfall

Use virtual rain gauges for each field and create a map of rainfall.

Irrigation

Monitor and control water, fertigation, and effluent applications.

Fleet

Track fleet locations and alerts while viewing reports on productivity.

View crop health imagery to assist scouting efforts.

Soil

Understand how water and other inputs move through your soil.

Deficiency of a single nutrient can impair healthy plant growth.

by Dr. rob Mikkelsen

We are familiar with the concept of preventative medicine, where health problems are avoided by good practices instead of curing sickness after they occur. This same concept applies to damage caused to crops by plant diseases and pests when adequate and balanced nutrition is lacking.

each nutrient in plants has unique and specific functions that operate in an intricate balance of physiological reactions. a deficiency of a single nutrient will result in stress that impairs healthy plant growth. Until the symptoms of deficiency stress become visible, the hidden roles of proper nutrition in maintaining plant health are too frequently overlooked.

new scientific studies are again confirming what farmers have known for many years about the link between plant health and nutrition –that healthy plants can generally withstand stress and attack better than plants that are already in poor condition. For example, recent work with corn has demonstrated the link between an adequate potassium (K) supply and increased leaf thickness, stronger epidermal cells, and decreased leaf concentrations of sugars and amino acids. all of these factors lower the attractiveness of plants for pests, such a spider mites.

The link between adequate K and soybean aphids has also been recently reconfirmed. research shows that K-deficient soybeans tend to transport more nitrogen-rich amino acids in the phloem, making them a favoured target of stem-sucking aphids.

The link between plant nutrition and disease control generally falls into one of these categories where proper fertilization can: Reduce pathogen activity: proper mineral nutrition can slow or inhibit the germination and growth of a variety of plant pathogens in soil and in plant cells.

Modify the soil environment: The

selection of a nitrogen (n) source can temporarily modify the rhizosphere pH during critical periods between germination and seedling establishment. Likewise, the addition of elemental sulphur (S) is a common practice to acidify the root zone of some crops for disease control.

Increase plant resistance: Healthy plant tissues are less susceptible to infection. proper nutrition can stimulate the production of physical and chemical defenses to cope with pathogens.

Increase tolerance to disease: adequate nutrition can help plants compensate for disease damage and to sustain a high level of natural compounds that inhibit pathogen growth within plant tissue.

Facilitate disease escape: plants that are adequately fertilized with boron (B) and zinc (Zn) have been shown to have fewer fungal spores that break dormancy on the roots, compared to deficient plants. a healthy photosynthetic capacity also allows for a quick growth response to a pathogen invasion.

Compensate for disease damage: an adequate supply of plant nutrients is closely linked with vigorous root growth and photosynthetic activity. These healthy plants can better tolerate increased disease burdens than plants stressed by nutrient deficiency. nutritional and environmental stresses often trigger greater pest and disease damage to crops. While proper fertilization does not eliminate the risk of pests and diseases, it provides an important degree of protection from many yield-robbing factors.

effective disease and pest management through proper plant nutrition improves crop quality and contributes to provide a safe, abundant, and nutritious food supply.

Dr. Rob Mikkelsen is Director, Western North America, International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI). Reprinted with permission from IPNI plant nutrition Today.

by Treena Hein

In o ntario, over 80 per cent of nitrogen ( n ) is still applied to fields as urea through spinner spreaders and is incorporated with tillage equipment. However, o ntario Ministry of a griculture, Food and rural affairs ( o M a F ra ) applied research coordinator, Ian McDonald, and others would like to see more n applied as a side dress in June.

“In the latter strategy, management decisions are made based on weather, crop performance, expected yield and so on,” he explains, “and the n application rate is targeted based on these conditions. When all the nitrogen is applied ‘up front,’ there is no way of making adjustments based on yield potential relative to current conditions.” Indeed, a later n rate decision can be very different than the n rate decision made before the crop has even been planted.

Many producers are reluctant to side dress, however. The reasons are many, including time and speed restraints, weather, herbicide application timing and a desire to avoid tramping emerged corn. “The reality is that side dressing, for those who are used to it, fits nicely in their system, lets them

adjust n rates and doesn’t tramp much crop,” notes McDonald. “We wanted to do a study to demonstrate that later applications of n could fit into farmers’ operations and give a number of important advantages.” For instance, Uan (urea mixed with ammonium nitrate) can be applied to emerged corn with largecapacity boom sprayers, which cover a lot of ground quickly and accurately without much crop damage.

In their study, McDonald and his colleague g reg Stewart ( o M a F ra field crop corn specialist) also wanted to examine how much surface-applied Uan is susceptible to nitrogen loss through ammonia volatilization, compared to a more “protected” soil injection system. They also wished to see how

aBOVE: uaN nitrogen corn leaf burn 4-7 days after streamer nozzle application of 30 us gal/ac to 12 leaf stage corn. at this stage of growth uaN applied leaf burn can be severe and symptoms remain visible for a long period of time, although new leaves continue to emerge from the whorl. yield impacts from such late applications have been variable and are not recommended.

surface applications of n in standing corn might cause leaf burn, which could in turn lead to yield loss. g rain Farmers of o ntario ( g F o ) provided support for the project, and technical assistance was provided by K. Janovicek, B. rosser, W. Featherston, and J. Welch at the University of g uelph.

To investigate ammonia and yield loss potential of surface Uan application, the team compared the use of three-hole streamer nozzles (with or without a grotain urease inhibitor) to Uan applied through injection below the soil surface with an a g Systems coulter knife injector. There were two trials during the 2013 study seasons, one shortly after planting and another at conventional side-dress timing (V6 stage). nitrogen was applied at 100 lb n /ac so that yields would be responsive to n loss. McDonald and Stewart measured ammonia loss by dosimeter tube traps and final yields by weigh wagon. There were four trial locations each year.

Since ammonia volatilization is associated with surface applications of Uan, nozzles that concentrate Uan in a single stream are recommended. In this study, the team compared dribble band, flat fan, and three-hole streamer nozzles, using ammonia dosimeter tube traps on bare soil to measure volatilization. e ach nozzle type was also applied with or without a grotain urease inhibitor, with each treatment replicated four times within each application timing. To investigate the impact of precipitation on ammonia volatilization, one set of dosimeter traps was moved to “fresh” ground within plots following every rainfall while another set was not moved.

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. Commercialized products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from this product can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for this product. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® crops contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for canola contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, and thiamethoxam. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin and ipconazole. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn with Poncho®/VoTivo™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-5821. Acceleron®, Acceleron and Design®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity®, RIB Complete and Design®, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup®, SmartStax and Design®, SmartStax®, Transorb®, VT Double PRO® and VT Triple PRO® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and Votivo™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

application of uaN nitrogen to 8 leaf stage corn using a conventional spray boom configuration. Note the disk blades ahead of the sprayer used to apply injected side dress nitrogen as comparison to the streamer applied N for crop injury, trampling impacts and ultimately crop yield.

There were three locations where yield impact of leaf burn from post-emergent Uan applications was investigated. There were also three treatments including untreated, streamer nozzle applying n over the emerged corn and a directed application that delivered n under the corn canopy to the soil surface. all application treatments were conducted at the four, eight and 10 leaf stages and replicated three times for each timing at each location.

Yield and ammonia loss were assessed. Some of the yields from corn that received surface applications of Uan were no different than those that received it by soil injection, but some had significantly less yield. “The lower yields came from using streamer only (no a grotain) at two locations in preplant application, and one sidedress location,” Stewart notes. “o n the average, there was a yield loss of six bu/ac across all locations and timings with later n applications.” Streamer + a grotain treatments were only significantly lower-yielding than injection at one side-dress location. across all locations and application timings, ammonia readings were always highest for the streamer treatments and were followed by slight declines for the streamer + a grotain treatments.

In the nozzle trials, the team found no clear difference in ammonia loss between application among the three nozzle types (fan, streamer, dribble). “This supports results from previous years, and suggests that using one nozzle over another doesn’t help mitigate ammonia volatilization,” McDonald notes. “However, when a grotain was included with Uan, ammonia volatilization was consistently reduced across all nozzle types and most dates.”

a s one would guess, precipitation decreases ammonia volatilization by washing the surface applied n into the soil.

“However, it was very evident that when soil surfaces were dry, the risk of ammonia volatilization from surfaceapplied Uan was much lower than when the Uan was applied to wet soil surfaces prior to receiving sufficient precipitation to ‘wash’ the Uan into the soil and thus stop volatilization losses,” adds Stewart. applications up to the six leaf stage did not show yield-impacting levels of leaf burn, but those beyond the 10-leaf stage did show yield losses compared to injected side-dress or pre-plant n applications. McDonald says that between the six and 10-leaf stage, application impacts on corn yield are quite variable and thus should be avoided. However, they do offer a wider window with minimal yield loss expectations, should the weather cause an application delay. He says once the corn gets to the eight leaf stage, farmers should consider using drop pipes, Y drops, high boy injection systems and so on to get good placement of n for availability to the corn crop.

In terms of final recommendations to farmers, McDonald says based on the results of this study, farmers should surface-apply Uan or urea to dry soil, and should remember that precipitation of at least 15-20 mm is needed to incorporate surface-applied n into the soil to stop volatilization losses.

“In addition, consider that applications of n to emerged corn that is not washed into the soil may also cause reduced yields beyond straight leaf burn caused by leaf interception during application,” McDonald notes. “ regardless of the timing of n fertilizer to emerged corn, sufficient rainfall is needed to move the nutrient into the root zone to ensure it is available for plant uptake.”

McDonald says that since the study began, many farmers have been asking questions about n application into standing emerged corn. “Interest is growing, and it’s likely because of a few difficult spring planting seasons,” he explains. “Farmers recognize the importance of planting date on achieving optimal yield potential and are looking for ways to speed up the planting progress and address nutrient application and other management choices after planting.” McDonald and Stewart are writing up the final results of this project, and the complete final report will be avail-

able on www.gocorn.net

“We continue to look at this as part of other projects including a significant g F o and industry collaboration on increasing the understanding and adoption of precision agriculture in o ntario, with management zone development and variable rate applications of nutrients and plant population,” says McDonald.

For more on fertility and nutrients, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Cost of production (COP) calculations provide a road map that helps to frame a plan for the following year and determine what’s best for the operation. It also ensures that finances are not overstretched by equipment purchases, inputs or land rental.

While some calculate COP on their operation as a whole, it’s important to break it down by enterprise such as corn, soy and beef.

“Over time, this allows farmers to identify winners and losers based on which areas contribute most to the profitability of the farm,” says John Molenhuis, business analysis and cost of production program lead with the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs.

“But there are tripping points that must be avoided to ensure the accuracy of the COP,” he cautions. They include:

Using cash vs accrual records. This is the error most often made when trying to determine COP. Accrual records ensure the accuracy of the numbers when tying revenue to production and earnings.

Allocating expenses across enterprises. Farm operators typically know where direct costs fit within each enterprise i.e. corn seed and nitrogen for the corn enterprise, soybean seed to the soy enterprise, feed for the livestock enterprise. But when inputs or resources such as staff time is shared across products, it is important to split and allocate the cost accordingly.

Ignoring non-cash costs. It can be tempting not to include non-cash costs like depreciation when calculating COP. However, this can result in a bias against one or more enterprises in the business. Recognize that equipment and buildings depreciate and the costs needs to be factored in. It will help when trying to determine when to replace these items.

To get a quick start on calculating your cost of production, take a new approach . Here are three tips from John Molenhuis:

Start somewhere! If you don’t have time to do a full COP calculation, get a handle on direct costs for each enterprise in your operation. Alternately, do a full COP for just one or two of your key enterprises. This will help you realize the value of the information and the need to expand it across the entire farm business.

Do it at data entry. A lot of farm accounting software has the ability to allocate COP to different enterprises so when you enter farm data on a daily or weekly basis, a good deal of your COP calculation will be done along with it. This makes it easier to track and input COP year over year.

Think beyond cash records. The more inventories and non-cash information you gather, the better you’ll be with making good farm decisions.

Soil “fingerprinting” project will support better management decisions at the farm level.

by Treena Hein

Soil is constantly changing, and during the last several decades, it is increasingly subjected to stressors, from the effects of climate change to newly implemented management practices. While soil description systems already exist, enhanced ways of tracking properties of the surface layer of the soil – also called topsoil, or on a more technical level, the soil a horizon – requires a methodology or framework that includes information not only on the various soil properties, but also the environmental and land use setting.

Dr. Catherine Fox, a soil scientist at agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) in Harrow, ont., along with other researchers at aaFC (Charles Tarnocai and David Kroetsch at the eastern Cereals and oilseeds research Centre in ottawa and elizabeth Kenney at the pacific agri-Food research Centre in agassiz, B.C.) and in collaboration with scientists in germany (Dr. gabriele Broll at University of osnabrück and Dr. Monika Joschko at ZaLF-Müncheberg) have developed an enhanced a Horizon Framework to facilitate such detailed recording.

The Framework, together with its electronic Field Form, allows for recording of field data using a system that – for each soil sample at the time of collection – generates a unique combination of symbols and coding known as a “soil fingerprint.” The generation of multiple soil fingerprints for one or more soils provides a database to help enable farmers, scientists and land-use decision-makers identify what is happening over time at both the field and landscape scale. Such information is invaluable for assessing the effectiveness of best management and remediation practices, and determining the impact of various environmental and urban-industrial related stressors.

The creation of the Framework required the developing of enhanced descriptors for soil properties known to be related to soil quality, designed to be applicable both nationally and internationally. The roster of traditional a horizon soil descriptors was expanded to link together information on soil processes and properties with environment and land use data. This involved collaboration between soil researchers from both Canada and germany.

The researchers identified key properties that affect the quality of soil and are subject to dynamic change. These include soil structure (e.g. occurrence of the kinds and sizes of soil aggregates which affect the extent of infiltration and movement of water), bulk density (extent of compaction), organic matter content (required for maintaining nutrient availability), pH (measure of acidity and alkalinity) and

electrical conductivity (measure of salinity). The Framework also included descriptors for soil texture (clay, silts and so on), landscape slope characteristics, and current land use and soil surface conditions.

The descriptors are then amalgamated into a combination of symbols that form the soil fingerprint – a snapshot of the state of the soil at the time of observation. “Because the soil fingerprint is written as a single line of text, when it’s matched with fingerprints at other points in time during the growing season or from successive years, or obtained at different locations in the field or landscape, it’s easy to identify where change has taken place,” Fox notes. “Changes and trends are easily flagged and can then be acted on.” Soil fingerprints can also be created from past soil surveys using the Framework to provide a baseline of information for comparison with current conditions.

The electronic Field Form was developed to provide a way to easily manage the data, since there can be a large amount of information involved if all Framework options and levels are included when describing the soil surface layer. The Field Form is interactive so

When it comes to trait technology, you’re looking for leadership and innovation. Hyland™ is powered by Dow AgroSciences outstanding research and development. Balance that with exemplary customer service and you have a combination of performance and profitability that is worthy of an encore.

by Blair andrews

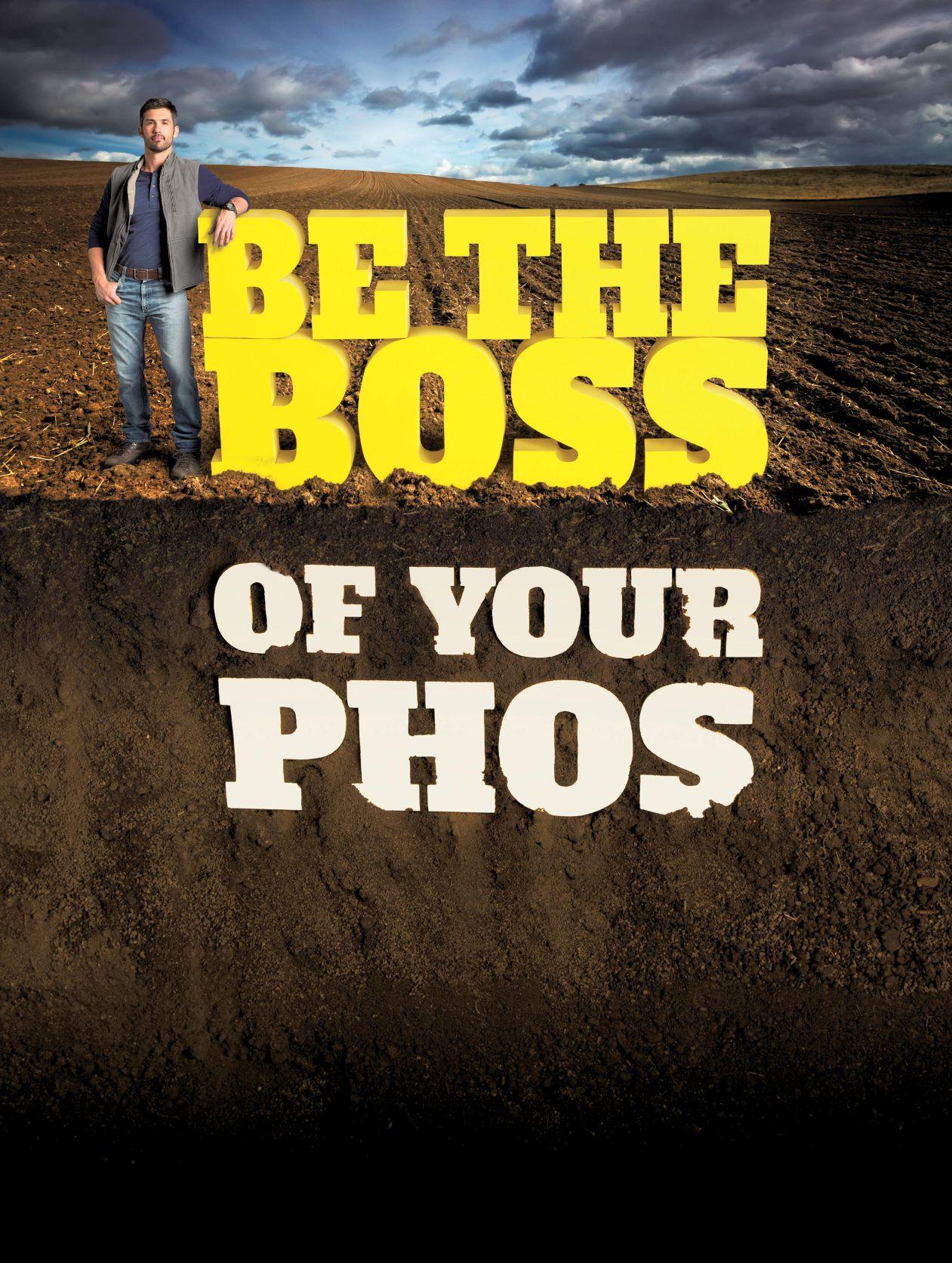

As crop rotations have become shorter and soybean yields have been increasing, more soybeans in ontario are showing symptoms of nutrient deficiency.

“Soybeans are huge feeders and we think 20 per cent or even more of ontario’s soybeans are deficient in potassium, so we need to apply more potash,” says Horst Bohner, soybean specialist with the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra).

For the most part, farmers in ontario have been able to grow soybeans without having to add fertilizer unless soil tests are low. nitrogen (n) is provided by the fixation in the nodules of soybean roots. as for the other key nutrients, the general rule has been to let the soybean crop scavenge the phosphorus (p) and potassium (K) from the previous corn crop.

To help determine whether adding fertilizer can boost soybean yields, a project was designed to assess a variety of blends and placements.

“There has always been this question: Does broadcasting really work compared to a two-by-two band or some form of getting it to the root zone in the spring?” says Bohner of the blends and how they’re applied.

The project, which was supported by the agricultural adaptation Council, the grain Farmers of ontario, and the ontario Soil and Crop Improvement association, also evaluated what soil types would have the greatest responses based on existing soil test levels.

Five field-scale trials were held in 2012 at sites in Lucan, Varna, Kenilworth, orangeville and Canfield. Two were planted using conventional tillage methods, while the other three were planted in no-till conditions.

In 2013, five more sites were added at goderich, Lucan, Woodstock, Strathroy and Caledonia. of these, three were no-till.

eight treatments were applied and replicated three times in 2012. all fertilizer treatments were applied by the planter at the time of planting. The treatments were:

1. an untreated check of no fertilizer

2. Twenty-five pounds of p and 40 pounds of K broadcast and incorporated

3. Twenty-five pounds of p and 40 pounds of K in a two-by-two band

4. Twenty-five pounds of p (Map granular) applied in-furrow

5. Twenty-five pounds of p (Map granular) in-furrow with five pounds of manganese

6. Three gallons of 2-20-18 (alpine liquid fertilizer) applied in row with seed

For the most part, farmers in Ontario have been able to grow soybeans without having to add fertilizer unless soil tests are low.

7. Three gallons of 2-20-18 with inoculant (same as above with optimize liquid inoculant mixed in fertilizer tank)

8. Fifty pounds of n plus 28 pounds of sulphur broadcast and incorporated (blend of ammonium sulphate and eSn)Treatments 6 and 8 were not included in the 2013 trials.

While Bohner notes the 2012 growing season produced fantastic soybean yields, many areas also experienced a prolonged period without moisture. Differences between fertilizer treatments were visible in the early season, and Bohner says there was no statistically

Don’t be fooled by imitators. AGROTAIN® nitrogen stabilizer is the original, most research-proven urease inhibitor technology on the market. With 20 years of trials and real-world results on millions of acres worldwide, it’s the one growers trust to protect their nitrogen investment and yield potential every time. Ask your retailer for AGROTAIN® stabilizer, or visit agrotain.com to learn more.

significant yield response to any of the treatments when the yields were averaged.

In 2013, the growing season was more typical as considerable moisture was available in the spring and fall.

The study concluded that applying fertilizer when soil tests are low can produce a good yield advantage of about five bushels per acre. However, the results don’t support the use of starter fertilizer for soybean production when the soil tests are adequate.

“When the soil test was low for p and K, we had a response to any form of fertilizer in any way we put it on,” says Bohner. “When the soil test was more reasonable, we had a very hard time getting a response.” although yield responses were only evident when the soil test was low, a broadcast application of p and K provided as much yield as any of the other methods of application. The broadcast application produced an average yield increase of 4.2 bushels per acre, while applying the p and K in a two-by-two band produced an increase of 4.5 bushels per acre. at very low testing sites, banding had a slight advantage. Fifty pounds per acre of Map applied in-furrow (in 15-inch rows) provided similar yield gains to fertilizer blends with both p and K.

For Bohner, the results show that it’s important to have enough nutrients in the soil for the soybean crop, whether it is left over from the corn crop or added during soybean planting.

“The real take-home message is do your soil test, know where your levels are at and feed the crop if you want reasonable yields,” he says. “When the potassium is low, there are very few nodules compared to where the K is high, so you’ve also got a nitrogen deficiency as well as a potassium deficiency if the soil test is low enough.”

as a next step in studying fertility for soybeans, Bohner is evaluating the economics of the “sufficiency approach” against the “build and maintain” method.

In the sufficiency approach, which is the basis of the recommendations from oMaF and Mra, just enough p and K are fed to the crop during the growing season.

“So as yields go up, is that approach adequate or do you need to build the soil test to a high level? High-yield guys would say the sufficiency approach is not adequate for high yields,” says Bohner.

So far, the science in ontario has shown the sufficiency approach is the most reasonable method for economic returns.

“If you buy into the ‘build and maintain,’ what level do you have to go? We don’t have the answers for that yet,” adds Bohner.

The method will be given the opportunity to prove itself as the study will be conducted over a period of six to 10 years.

CONTiNuEd FROM PaGE 20

that whoever is doing a soil assessment in the field is able to enter data directly.

There are other benefits to using the Field Form. For example, Fox explains that as the data for the soil properties, such as soil structure types or pH, are being recorded in the Field Form, the soil descriptor values and codes for these soil properties will be automatically written into the soil fingerprint. The electronic form is also flexible, allowing users the choice to select the level of description and options that are most suitable for their study. For example, different soil properties may be required to be able to monitor how different management practices have affected soil in an area, or to compare how different landscape features have affected the upper soil layer.

The Framework was also designed to be able to include additional codes to focus on particular areas of interest, such as water flow, root distribution or soil organism populations. and having the Framework data in digital format also means the stored values can be easily transferred into other software programs to analyze trends in soil change, or to build models that aid in decision-making.

Further work to refine the Framework and Field Form is now occurring in collaboration with soil specialists with the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs (oMaFra), researchers from the ridgetown campus of the University of guelph and the aforementioned institutions in germany. This new work is part of the knowledge and technology transfer (KTT) stage of this research, co-led by natalie Feisthauer, a land resource scientist at the aaFC ontario KTT office in

guelph and David Kroetsch, from aaFC in ottawa.

The goal of this phase of the project is to facilitate the transfer of the Framework and Field Form to the agricultural community, both to specialist and non-soil specialists. “We will be gathering input on how the Framework works under different applications, field conditions, farming systems and management conditions as well as how the Field Form can be enhanced,” says Feisthauer, “including expanding and further validating the descriptors.”

When the Framework is finalized, training workshops will be planned for researchers, extension staff and farmers, and other members of the agricultural community who may wish to use the Framework on their own or in conjunction with a consultant or researcher. Feisthauer says those who conduct environmental site assessments will also be invited to learn about the Framework. an integral part of this phase of the project is to develop additional resource and guidance materials, both in electronic and written form, with a focus on users not familiar with the underlying soil science concepts and terminology involved. “This guidance will include not only how to correctly collect and input the data, but also how to properly interpret the identified soil fingerprint changes,” Feisthauer says.

This is an exciting advancement for those who study and manage our soil, as soil quality is obviously of paramount importance for crop cultivation success, minimizing and mitigating erosion, and so much more. “If we don’t have detailed information about our soil to be able to identify the kind of changes happening over time, it’s much more difficult to know if the soil is at its optimum quality to sustain growing crops and supporting livestock and animal production,” says Fox.

There’s a lot of potential in these seeds.

Help realize it with the number one inoculant.

There’s a reason HiStick® N/T is the best-selling soybean inoculant in Canada. It’s the only one that’s Biostacked®. Unlike other offerings, a Biostacked inoculant delivers multiple bene cial biologicals to enhance the performance of soybeans. These help increase root biomass, create more nodules and improve nitrogen xation. Of course at the end of the day, all you have to know is what it does for your bottom line. HiStick N/T out-yields non-Biostacked inoculants by 4-6%. So why settle for less? Visit agsolutions.ca/histicknt or contact AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) for more information.

Always read and follow label directions.

, and BIOSTACKED

by Carolyn King

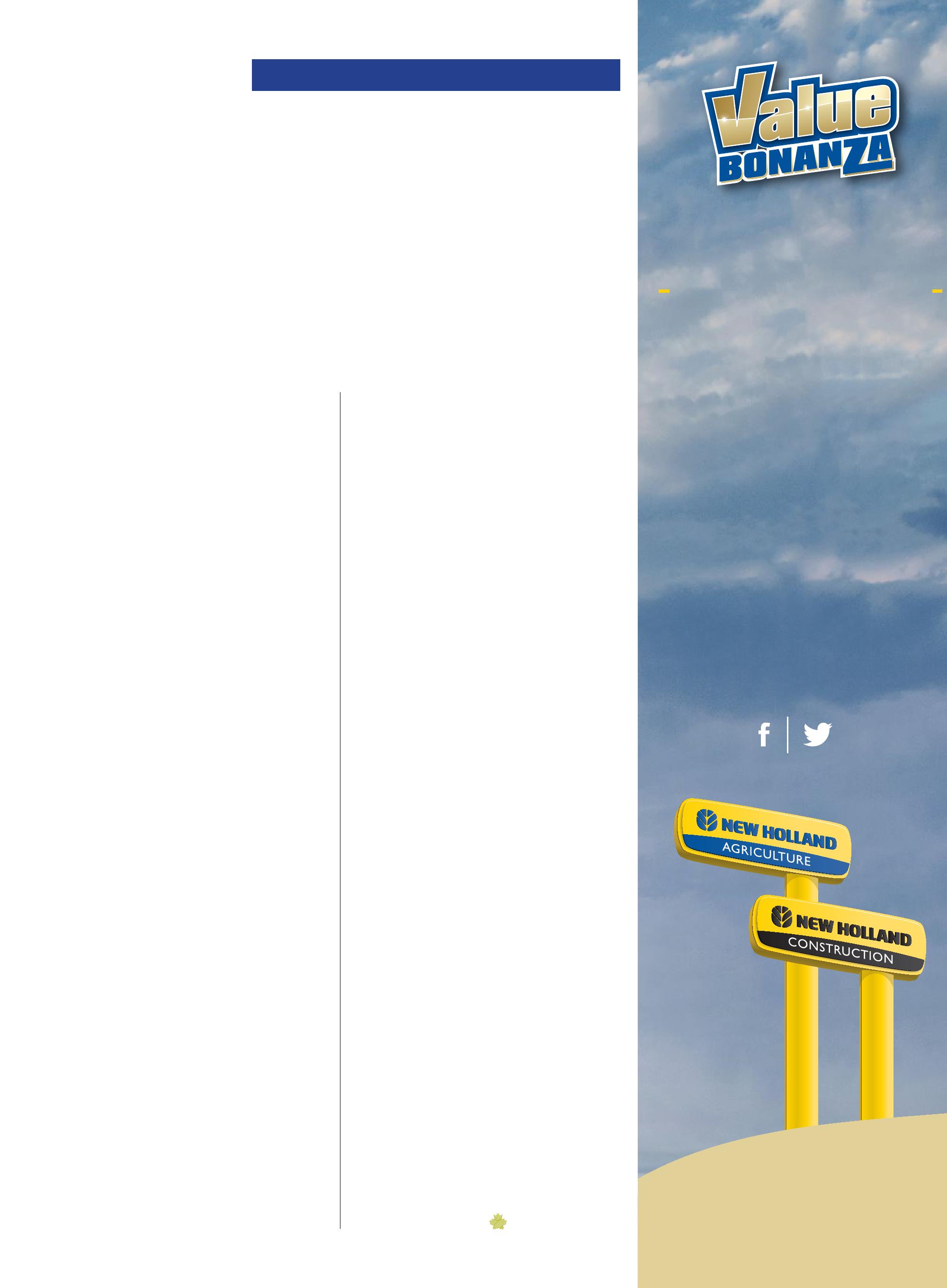

Ontario has several weed species with herbicide resistance, but the ones with glyphosate resistance (gr) are a special challenge because of glyphosate’s pivotal role in the production systems on many farms. as well, some gr weeds have developed resistance to other herbicides, making the control challenge even tougher. For farmers, managing gr weeds could mean higher weed control costs and, in some cases, a loss of effective herbicide options in specific crops. So, ontario researchers are evaluating the latest herbicide options as well as nonherbicide alternatives for managing gr weeds.

Currently in ontario, three weed species have been confirmed as having gr populations – biotypes that can survive and reproduce after exposure to what used to be a lethal dose of this herbicide. They are giant ragweed Ambrosia trifida, Canada fleabane Conyza Canadensis and common ragweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia

Dr. peter Sikkema of the University of guelph-ridgetown leads an annual survey of gr weeds in ontario. The survey shows gr

weeds are an increasing problem. gr giant ragweed biotypes were first confirmed in 2008 and have now been found in seven counties. gr Canada fleabane, first found in 2010, is now in 12 counties. and gr common ragweed biotypes were first confirmed in essex County in 2011, but so far none have been found beyond that county. Some gr biotypes of these three weeds are also resistant to Firstrate, a group 2 herbicide.

Herbicides are grouped are based on their mode of action – the way their active ingredients attack the plant. For example, group 2 herbicides block the normal function of an enzyme referred to as aLS/aHaS. group 2 includes a large number of active ingredients in several chemical families, such as the imidazolinones and

TOP: For GR Canada fleabane control in soybean, the researchers have found some good options, but the range in control can be very wide from field to field.

iNsET: a two-pass approach worked best for controlling GR common ragweed, as in this plot with Roundup + integrity applied before soybean emergence, followed by Roundup + Reflex post-emergence.

sulfonylureas. group 9 includes only one active ingredient – glyphosate. It inhibits the epSpS enzyme.

When you apply a herbicide to control a weed species, you select for the few individual plants within the population that happen to be able to resist the herbicide’s mode of action. If that resistance is heritable, then those surviving plants can produce offspring with that resistance. If you use herbicides with the same mode of action year after year, then eventually the only weeds remaining in the field will be those that are resistant to that mode of action.

Sikkema’s surveys show the scope of ontario’s gr weed problem, but they don’t necessarily catch every single gr weed in the province. So it’s very important for growers to scout for possible herbicideresistant weeds in their fields so they can deal with the problem before it explodes. at the University of guelph, Dr. François Tardif’s lab does testing to determine if suspect weed samples are indeed herbicide-resistant.

Sikkema’s research group is evaluating a wide range of herbicide options for each of the three gr weeds, with funding from grain Farmers of ontario, Canadvance, and the herbicide manufacturers.

Sikkema outlines some highlights from his group’s recent studies in corn, soybeans and winter wheat.

For gr giant ragweed control in corn, they are testing preplant and postemergence herbicide options in tank mixes with roundup. “In the preplant programs in corn, the most effective treatments are Marksman and Callisto + atrazine,” he says.

“Similarly, for post-emergence herbicides in corn, the ones that contain dicamba have been most effective: Banvel, Distinct and Marksman. pardner + atrazine has looked interesting as well.”

In winter wheat, most of the herbicides they’ve tested have given good control of gr giant ragweed, including 2,4-D ester, Target, estaprop, Lontrel and Trophy.

For gr giant ragweed control in soybean, the researchers’ latest studies have involved roundup ready 2 Xtend soybean, which has tolerance to both glyphosate and dicamba; it is expected to be available to growers in the near future. Their experiments are showing very good control of gr giant ragweed – and also gr Canada

fleabane – with tank mixes of dicamba and glyphosate applied preplant or in-crop. Sikkema’s group has a large program on gr Canada fleabane control. He notes, “We can get quite good control in corn and wheat, but it’s a huge challenge in soybean.”

In corn, they are testing preplant and post-emergence options tank mixed with roundup. In the preplant treatments, the dicamba-based herbicides Banvel, Marksman and Battalion gave greater than 90 per cent control. Callisto + atrazine and Integrity provided 80 to 90 per cent control.

Likewise, for post-emergence treatments in corn, the dicamba-based herbicides all gave greater than 90 per cent control. For pardner + atrazine, control was between 80 and 90 per cent.

For gr Canada fleabane control in winter wheat, Infinity, Lontrel, Target, Dyvel, Banvel and 2,4-D ester were the most effective. However, Sikkema cautions, “although Banvel, Dyvel and Target are very effective on gr Canada fleabane – and also on gr giant ragweed – I am reluctant to recommend them because I think the margin of crop safety in winter wheat is too narrow; you can incur yield losses due to crop injury.”

In soybean, the researchers have looked at a wide range of herbicides, but are finding it very hard to get consistent control

of gr Canada fleabane. For example, in their enhanced burndown experiments, “The tank mixes of roundup plus eragon, Integrity, 2,4-D, Liberty, gramoxone, Firstrate and Classic all have activity, but the range in control can be very wide from field to field,” says Sikkema.

“We’re continuing to do research on this. We’ve done over 20 experiments and haven’t yet found out what the contributing factors are causing this variability in control.”

In their burndown plus residual treatments in soybean, the most consistent control of gr Canada fleabane was with roundup + Sencor applied at the highest label rate registered in ontario. “However, at that rate you get crop injury on lighttextured soils, you could have sensitive cultivars that contribute to crop injury, and it’s simply too expensive,” notes Sikkema. Tank mixes of roundup plus Firstrate or Broadstrike rC are also effective, but, in some fields, there are multiple resistant Canada fleabane and these tank mixes will not control those biotypes.

In the post-emergence treatments in soybean, the best results were with roundup + Firstrate. But Sikkema cautions, “From our work, we know that 12 per cent of the fleabane in ontario is resistant to both glyphosate and Firstrate. We had from 20 to 90 per cent control with Firstrate, and I

Optimum® AQUAmax® products deliver, rain or shine. No matter what the weather may be, Pioneer® brand Optimum® AQUAmax® corn products are designed to deliver. Their superior genetics use water more efficiently from root to tassel. So you’ll enjoy top-end yield potential under ideal conditions and harvest more bushels per drop under drought stress. Talk to your local Pioneer sales rep about the right Optimum® AQUAmax® corn products for your acres.

think that is a function of whether it’s gr Canada fleabane or if it’s multiple-resistant Canada fleabane.”

He adds, “We have no effective post-emergence options in soybean for multiple-resistant Canada fleabane.”

one of Sikkema’s graduate students, annemarie Van Wely, has just finished a study of gr common ragweed that included herbicide treatments in soybean.

“In her enhanced burndown experiment, she looked at every possible tank mix that is registered [in ontario]. She found that roundup + eragon was the most effective, but the control was only 72 per cent,” notes Sikkema.

“In her burndown plus residual treatments [using tank mixes with roundup], Lorox and Sencor gave greater than 80 per cent control. Integrity and optill provided between 70 and 80 per cent control. However, the Lorox and Sencor treatments were applied at the highest label rate registered in the province. I think farmers will be reluctant to use them at those rates because they are expensive, they can cause injury on light-textured soils, and there could be cultivars sensitive to Sencor.”

In Van Wely’s post-emergence treatments, roundup + reflex gave the best results with between 70 and 80 per cent control of gr common ragweed.

Based on these results, it appeared that a two-pass approach would likely be needed for effective gr common ragweed control. So Van Wely applied tank mixes of roundup with one of Integrity, Lorox or Sencor, prior to soybean emergence, and then applied roundup + reflex post-emergence. That combination gave between 85 and 95 per cent control of gr common ragweed.

non-chemical weed control options can be important for dealing with gr weeds, especially if they have resistance to multiple herbicides.

a number of ontario studies are underway on such options. For example, Tardif is leading a project with ontario Ministry of agriculture and Food and Ministry of rural affairs weed specialist Mike Cowbrough to assess crop management approaches to reduce weed seed production in situations where weeds aren’t effectively controlled by a herbicide. “The weeds may be herbicide resistant, or the herbicide may not have lasting power in the soil to stop the weed seeds from germinating, or the weed’s biology may allow it to germinate later on,” explains Cowbrough.

The project, established in 2014, involves four cropping rotations. It is assessing the effects of crop type, seeding rate, fertility and cover crop practices on weed seed production and crop yields in corn and soybeans.

Cowbrough says, “We’ve coined the project ‘To Fight the Light’ because our goal with each cropping system is to cover the soil almost 100 per cent of the time so light isn’t touching the soil and stimulating new weed seed germination.”

He suspects it will take several years before the effects of the different treatments on weed seed production become clear. “It is something that really struck me recently when I spoke to three australian producers [who were dealing with serious herbicideresistant weed issues]. no matter what non-chemical strategy they used, they all said it took about five to six years before they saw meaningful differences in weed populations because there had been such high weed seed deposition in previous years.”

With such a long lag time until results appear, the researchers

want to be sure the practices are cost-neutral. Cowbrough says, “For instance, let’s say I could demonstrate that a 10 per cent increase in your seeding rate in corn would dramatically reduce the amount of weed seeds and that the increased corn seed cost would be paid back in higher yields, but it will take five years to see a weed control benefit. There’s a higher probability of people adopting that practice than if you have to spend $35 per acre on a practice and you won’t see a weed control benefit from it for five years.”

according to Cowbrough, Dr. eric page with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) at Harrow will be joining the To Fight the Light project in the future. page is working on similar research on giant ragweed, including gr giant ragweed.

In another project, page and aaFC’s Dr. rob nurse are testing a prototype of the Harrington Seed Destructor that aaFC has purchased. This machine was developed by ray Harrington, a crop producer in australia, as a tool for managing weeds with resistance to several herbicides (see ‘Australia’s fight against herbicide resistance’ on page 32). The Destructor crushes weed seeds that come out of the combine with the chaff. The researchers want to see how well it works in ontario’s crops with ontario’s weed spectrum.

Sikkema emphasizes that preventing glyphosate resistance is quite straightforward. “We have to apply glyphosate less frequently. It is as simple as that.”

To reduce reliance on glyphosate, he recommends adding diversity into your weed management programs. “Include multiple crops in your rotation, including some that are not roundup ready, so that you won’t be applying glyphosate post-emergence in the crop. You still could put it on preplant as your burndown or as a pre-harvest or post-harvest application,” says Sikkema.

“If you are growing roundup ready crops, then I suggest a two-pass weed control system. In the first pass apply a broadspectrum, soil-applied herbicide that has activity on the primary grass and broadleaf weeds on your farm. Then watch the field and decide whether or not you need a post-emergence application of glyphosate.”

Sikkema also suggests using tillage to control weeds at strategic points in your crop production system, although it’s important to avoid excessive tillage which can lead to soil erosion, breakdown of soil structure and other problems. and he recommends, “Use excellent crop husbandry, whether that’s using well adapted cultivars or hybrids that emerge quickly and outcompete the weeds, using the right seeding rates, possibly reducing soybean row widths so the canopy closes earlier, controlling insects and diseases, using proper fertility – anything you can do to make the crop more competitive with weeds.”

Cowbrough has two pieces of advice for reducing the risk of herbicide resistance. First, focus on the most prominent weed species on your farm. “The bigger the weed’s population, the more likely it is that you will select for a resistant biotype if you apply that selection pressure. and if it’s a species that is more prone to being selected for herbicide resistance and its seed is mobile, then the risk will be higher.”

and second, use more than one strategy to attack those prominent species. “That could mean the addition of two or more herbicide modes of action, using some cover crops, doing some tillage, and so on.”

Ask the new 7R Series to do anything and you’ll fnd that there’s not much it can’t do. In transport, it’s agile and responsive. In the feld, it has the horsepower (210 to 290 engine hp*) to pull a large implement through tough conditions. Effcient? You can check that box too because the 7R employs the latest Final Tier 4 engines and the new e23™ PowerShift Transmission with Effciency Manager™ , which matches the gear with the activity, improving effciency and fuid economy. Technology? It’s loaded. Activate AutoTrac™ and JDLink™** and you can enjoy the benefts of precision technology and John Deere FarmSight™ . We could go on, but the new 7R is best appreciated when you can experience it for yourself. Visit your John Deere dealer today and take the new John Deere 7R Series Tractors for a run. Nothing Runs Like A Deere. ™

Alternative non-chemical weed control strategies making a difference.

by Donna Fleury

In australia, the development of multiple herbicide resistance in some of the most serious annual weeds has been the catalyst for the introduction of new agronomic practices. g rowers and researchers have worked together to introduce new non-chemical weed control techniques focused on weed seed capture and destruction during commercial grain crop harvest.

“Herbicide resistance in problematic weeds is extensive across the australian crop production zone,” explains Dr. Michael Walsh, research associate professor at the University of Western australia. “It is particularly severe across the western australian wheat production region (10 million hectares) where 98 per cent of annual ryegrass populations are resistant to at least one mode of action herbicide.” The majority of populations are now multi-resistant (i.e. have multiple resistance mechanisms), with the resistance problem consistently severe across all cropping systems and crop types.

The biggest problem weeds infesting australian cropping

fields are annual ryegrass, wild radish, wild oats and brome grass.

Walsh explains that these annual species all have high genetic diversity, boast prolific seed production, can establish high population densities and have relatively short-lived seed banks. They also retain a significant portion of their seeds at maturity, meaning that many seeds remain attached to the upright plant and are collected during the grain crop harvest. Walsh and his colleagues have developed alternative weed control strategies or harvest weed seed control (HWSC) systems used during commercial grain harvest operations to minimize fresh seed inputs to the seedbank and lower overall weed populations.

“The clear message now emerging from our research is that all feasible and practical means need to be used to drive weed populations to the lowest possible levels in crop production fields,” explains Walsh. “Very low weed populations are not just about avoiding or managing herbicide resistance, but more

aBOVE: a chaff cart system in action in the field.