PRR pathogen beating soybean resistance

PG. 6

POWERHOUSE COVER CROPS

Building soil organic carbon. PG. 12

4R PRACTICES FOR MANURE

Adjusting chemical fertilizer rates for manure-amended soils

PG. 14

HAVE YOU EVER THOUGHT...

“I

PRR pathogen beating soybean resistance

PG. 6

POWERHOUSE COVER CROPS

Building soil organic carbon. PG. 12

Adjusting chemical fertilizer rates for manure-amended soils

PG. 14

HAVE YOU EVER THOUGHT...

“I

JOIN TENS OF THOUSANDS OF FARMERS WHO HAVE THOUGHT THE SAME THING AND GOTTEN BETTER BY ADDING JUST 3 PRODUCTS.

You could buy a new planter or new-to-you planter, but the biggest yields yearover-year have come from focusing on the row unit and starting with automated downforce, electric drives, and high speed, all available through Precision Planting. It’s a shift in thinking, but the 70% savings versus a new(er) planter and the yield bumps have made it an easy decision. So if you want more out of your planter, add vDrive®, DeltaForce®, and SpeedTube® to your row units.

WE BELIEVE IN BETTER PLANTERS WITH BETTER ROW UNITS.

14 | A wake-up call for resistance stewardship

The phytophthora root rot pathogen is overcoming commonly used resistance genes in soybean varieties. by

Carolyn King

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Using tools responsibly by Alex Barnard

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2023 • EASTERN EDITION

12 | Cover crops a powerhouse tool for building carbon

New research examines the benefits of – and barriers to – long-term cover crop adoption.

by Julienne Isaacs

6 | Developing 4R practices for manured cropping systems

Adjusting chemical fertilizer rates for differences in nutrient availability in manure-amended soils.

by Carolyn King

PALMER AMARANTH FOUND IN ONTARIO FIELD

It was only a matter of time before Palmer amaranth was found on a farm in Ontario. Although technically it was found back in 2007 along a rail line outside of Niagara Falls, surveillance of that area in the following years have not detected any plants since the initial finding. In late summer 2023, an individual plant was found on a farm in Wellington County. The most valuable thing that can be done at this point is to know the process to identify any plants you suspect may be Palmer amaranth and destroy any plants before they produce seed.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

ALEX BARNARD EDITOR

You’ve probably heard the saying, “With great power comes great responsibility.” While none of you have likely been bit by a radioactive spider and developed superpowers to fight crime in Brooklyn, farmers do have access to a highly specialized arsenal of tools to combat the plethora of pests and diseases each season.

But how long will those tools remain effective?

At this summer’s Ontario Crop Diagnostic Days at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown Campus, OMAFRA’s Tracey Baute, and the university’s Jocelyn Smith and Yasmine Farhan presented on European corn borer and how it has overcome some of the Bt corn traits that have effectively controlled for more than twenty years.

On page 6, Carolyn King writes about how most growers are using soybean varieties with resistance genes that were no longer effective against the Phytophthora root rot pathogen. These announcements are concerning, as these tools are the result of a lot of research, time and effort, and in many cases, there are no similar tools in the pipeline.

And with the incursion of weeds like waterhemp and Palmer amaranth, keeping as many chemical control options available for as long as possible, especially when these weeds are so adept at developing resistance, will be clutch.

Part of the issue is that pests and diseases are very, very good at overcoming and adapting to resistance – or developing it themselves. Their survival depends on it.

Part of the issue is time and money. There are so many factors to balance in a season, and with rising costs sometimes an additional practice or product for an issue that might be a problem this season gets put on the backburner in favour of an issue that will almost definitely be a problem. There are only so many hours in a day, and only so many passes you can make through a field before you risk other issues, like compaction.

But the fact remains that these tools will only remain available – and viable as control options – if they’re used effectively and responsibly. Crop rotation, growing different hybrids or trait combinations, using different modes of action in subsequent years or using products with multiple modes of action in the same year, growing certain cover crops, knowing which pests or diseases are present or likely to afflict your fields and planning accordingly, properly calibrating sprayers – these are some of the ways to improve your chances of controlling pests and diseases that also reduce the risk of them adapting to the pesticides or used.

Integrated pest management may reduce reliance on chemical pesticides, but in most cases IPM strategies still count on having some form of chemical control available to work in conjunction with the other tools in the toolbox.

The principles of 4R nutrient stewardship – right source @ right rate, right time, right place – can, in general, be applied to pest management, as well. When choosing chemical pesticides or seed, use the:

• Right source: a different variety or crop or mode of action from the previous growing season;

• Right rate: Use a high enough concentration of pesticide to provide appropriate coverage for control;

• Right time: Apply chemical pesticides when they will be most effective (both by crop stage and time of day); and

• Right place: Make sure the pesticide is getting where it needs to go, whether that’s on the soil, in the soil, or to the plant itself.

This winter, perhaps consider if there are ways you can more better manage pest and disease pressure on your farm. You may be as responsible as you can reasonably be, or you may find a couple additional strategies to enact. Perhaps the best way you can contribute to responsible resistance stewardship is to talk to other farmers at the local coffee shop and talk about the strategies you employ – you might just inspire someone else to do a little better, too.

Email:

Mail:

Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1 EDITOR Alex Barnard • 519.429.5179 abarnard@annexbusinessmedia.com

NATIONAL ACCOUNT MANAGER Quinton Moorehead • 204.720.1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

$112.00 plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 4 issues Feb/Mar, Apr/May, Sep/Oct, Nov/Dec – 1 Year - $48.50 Cdn. / US $110.00 plus tax

Potatoes in Canada – 1 issue Spring – 1 Year $17.50 Cdn. plus tax

in Canada – 2 issues Spring and Fall – 1 Year $17.50 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374 No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2022 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet

Create a snapshot of your crop nutrition needs now to spring into action

If this year’s weather is any indication – from a summer filled with wildfires and dry conditions to an El Niño winter – the message is clear: Prepare your soil for fluctuating conditions to increase crop yield potential.

Ideally, you have conducted a soil test this autumn and can use those results alongside previous soil findings to create a plan for the upcoming growing season. If you didn’t, mark it on your calendar now for next fall, and gather the information you do have – data, previous results (soil or tissue test, yields), local research and resources, etc.

Harvesting a crop removes from the soil Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P) and Potassium (K), along with other macro- and micronutrients. With all the stress put on soil, it’s time to create an action plan for the spring with support from agronomic experts and your retailer.

No matter the weather outlook, springtime planting conditions can be challenging to get crops off to a great start. Give your crop a boost by providing it with the nutrients needed to support optimal crop yields.

Consider these 5 crop nutrition best practices so you are ready to act when the time – and weather – is right.

1. Revisit your most recent soil test to determine nutrient needs and an appropriate yield goal.

2. Determine crop nutrient removal based on yield goals to ensure fertilizer rates at minimum replace nutrients when soil tests are too maintained. When soil tests are low, multi-year crop rotations may need to be calculated to determine where additional fertilizer can be added beyond crop removal.

3. Plan on a spring fertilizer application to get the most benefit for sandy, coarse soils or soluble forms of nitrogen and sulfur.

4. Use a locally placed/banded phosphorus fertilizer for cool wet, saturated conditions.

5. Monitor mobile nutrients for proper balance, including nitrate nitrogen, sulfate, boron and chloride – which are primarily found 30 to 60 cm into the soil.

Crops need N, P, K and S to reach their full yield potential. Choose a fertilizer you can count on to deliver the essential nutrients at the right time across your fields.

Look for features that ensure your crops are getting the support they need, including:

• A consistent granule size

• Uniform distribution across your field

• Key nutrients in a homogenous granule

• Increased nutrient availability for greater plant uptake

• Provides season-long sulfur

• An Enhanced Efficiency Fertilizer

• A formulation built for your soil conditions

Work with your retailer to get set up for the spring, but know that crop nutrition and success isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it situation. Proactively monitor crop growth and development throughout the year and address needs as they arise, while capturing information for future planning. Incorporate tissue testing samples from throughout your field to monitor crop nutrient status.

Consider a crop nutrition plan a living document that you review annually to maximize return on fertilizer investments. Be ready and confident for next year’s growing success, no matter the weather.

Give your crops the nutrition they need to perform their best. Discover how to supercharge your yields with MicroEssentials® performance fertilizers for advanced crop nutrition.

The phytophthora root rot pathogen is overcoming commonly used resistance genes in soybean varieties.

by Carolyn King

Resistant varieties are a critical tool for managing phytophthora root rot (PRR) in soybean. However, a recent PRR survey in Canadian soybean fields revealed troubling news: 84 per cent of the growers were using soybean varieties with resistance genes that were no longer effective against the PRR variants in their fields.

Fortunately, the new diagnostic method used in this survey is now available to soybean growers, breeders and seed suppliers so they can find out which resistance genes still work. That information can help everyone to more effectively fight this major disease.

Richard Bélanger, a professor at Université Laval in Quebec, led the development of the diagnostic method and the survey. He explains that PRR is a destructive stem and root disease of soybean that results in about $50 million in yield losses per year in Canada. It is caused by Phytophthora sojae, a persistent, soil-borne pathogen called an oomycete. PRR can infect soybeans at any growth stage.

Although some seed treatments can help reduce this disease and practices like field drainage can help alleviate disease damage, genetic resistance is the cornerstone of PRR management.

Crop breeders make use of two types of genetic resistance. One is horizontal resistance, also known as partial resistance or field resistance. It is not specific to the pathogen’s strain or race. It involves multiple minor genes which together give the plant some tolerance

to the disease, but not complete resistance.

The other type is vertical resistance, also known as total resistance or race-specific resistance. This involves single genes that provide complete resistance to specific variants of the pathogen. For PRR, such genes are called ‘Rps’, which stands for ‘Resistance to Phytophthora sojae.’ For instance, in Canadian soybean varieties, commonly used Rps genes include Rps1a, Rps1c and Rps1k.

Beélanger explains that the effectiveness of a particular Rps gene actually depends on the presence of the corresponding avirulence (Avr) gene in the pathogen. This avirulence gene triggers a resistance response in the plant, enabling the plant to fight off the pathogen.

So, if growers use a soybean variety with an Rps gene that matches the Avr variants in their field, they’ll get complete control of the disease – at least, in the short term.

However, repeated use of the same Rps gene in a field selects for Phytophthora sojae variants that have some difference in the corresponding Avr gene which allows the pathogen to evade detection and infect the plant. With ongoing selection pressure, more and more of the pathogen’s population becomes virulent on soybean varieties with that Rps gene.

Over the years, continued selection pressure has resulted in so many

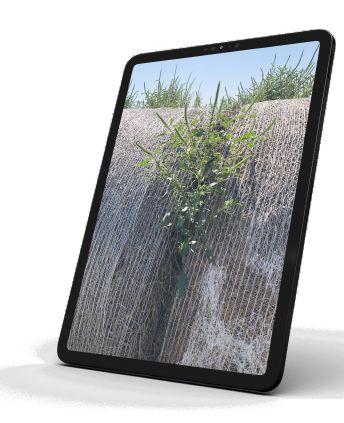

ABOVE: A strip trial comparing the yields of two soybean varieties with and without the correct resistance gene against éPhytophthora sojae.

THE LEVEL OF PRECISION YOU’VE COME TO EXPECT FROM US IS NOW AVAILABLE ON YOUR SPRAYER.

Take charge of your spraying accuracy through independent control of rate and pressure with SymphonyNozzle™ and a Gen 3 20|20® monitor. Together they reduce over-application with swath control and level out inconsistent application on turns. Take your sprayer a step further and add ReClaim™, our recirculation system.

WE BELIEVE IN BETTER SPRAYERS WITH BETTER CONTROL.

RETROFIT YOUR CURRENT SPRAYER AND SAVE ON INPUTS.

Phytophthora sojae races that plant pathologists now name the variants based on the Rps genes that they can overcome. For example, ‘pathotype 1a’ is virulent on Rps1a; ‘pathotype 1a, 1c’ is virulent on both Rps1a and Rps1c; and so on. These days, many variants can defeat more than one Rps gene.

The traditional procedure to identify PRR pathotypes is called the hypocotyl method. Bélanger explains that this method requires culturing the pathogen in the lab and growing a set of different soybean lines that carry the different Rps genes. Then, for each isolate of the pathogen, you inoculate the hypocotyl of every soybean line. Then, you measure the reactions of the different lines and score the response to identify the pathotype.

According to Bélanger, the hypocotyl method can take two to three months, and it is prone to errors like false-positives and falsenegatives. “It is very cumbersome, time-consuming and imprecise,” he says.

“With the advent of new genomic tools, we saw the opportunity to exploit them to get a faster and more accurate diagnosis.”

The researchers have developed a molecular method that is based on identifying Phytophthora sojae’s Avr genes – the first time such an approach has been used for pathotyping a plant pathogen.

They have created genetic markers that distinguish between virulent and avirulent isolates for the most common Avr genes in Canadian soybean fields. These markers are used with a technique

called multiplex PCR, which gives a response for all the different Avr genes simultaneously.

Bélanger says, “Once you set things up, this method takes only two to three hours, so it has significant time savings. And in terms of accuracy, it is unmatched.”

After confirming the accuracy of their new method, the researchers used it to analyze almost 300 Phytophthora sojae isolates from soil samples collected in Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba soybean fields. These three provinces together account for over 95 per cent of Canada’s soybean-growing area.

The survey was conducted between 2016 and 2019, and the samples were analyzed for Avr1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1k, 3a, and 6

“We found a clear trend toward pathotypes that were overcoming the main Rps genes used in soybeans,” Bélanger notes.

“For instance, almost all isolates carried the pathotype 1a. Rps1a was the first Rps gene released commercially in Canada, and because it has been used and over-used, it is now completely overcome.

“Rps1c, which came after 1a, is also basically overcome. Currently, Rps1c is by far the most used Rps gene in Canada. This is worrying because this gene is basically obsolete at this stage.”

For the Quebec samples, 96 per cent of the isolates could overcome Rps1a, and 77 per cent could overcome Rps1c. For Ontario, 94 per cent could overcome Rps1a, and 75 per cent could overcome Rps1c. And for Manitoba, 100 per cent could overcome both Rps1a

and Rps1c

“Rps1k, which was the answer to the new pathotypes developing as a result of Rps1c being overcome, is slowly getting overcome as well,” Bélanger says. “The situation in Manitoba is particularly worrying because Manitoba started with Rps1k earlier than Ontario or Quebec did. Selection pressure has been doing its job and Rps1k is being overcome.”

In Manitoba, 67 per cent of the isolates were able to defeat Rps1k, compared to 16 per cent in Quebec and 33 per cent in Ontario.

Fewer isolates were able to defeat newer genes like Rps3a and Rps6. He notes, “The options for Rps genes that are still widely effective are getting extremely limited.”

The survey in Manitoba and Quebec also collected data on the soybean varieties grown in the sampled fields. The researchers’ analysis found that 84 per cent of the fields had varieties with Rps genes that were not resistant against the pathotypes in those fields.

As expected, the survey results showed that pathotype diversity has increased since two earlier Canadian PRR surveys, one conducted in the 1980s and the other from 2010 to 2012. For instance, pathotype 1a is now rare, and more complex pathotypes like pathotype 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1k, 7 are on the rise. “As we grow more soybeans in Canada and we plant more resistance genes, the pathotype diversity increases,” says Bélanger.

He also points out that concerns about the stewardship of Rps genes are not limited to Canadian soybean production. He and his research group were involved in an international study published in

2023, which determined that the decreasing effectiveness of commonly used Rps genes is a global trend.

“Our findings show that we really need to be more aware and have a better strategy to deploy Rps genes in line with the selection pressure on the different Phytophthora sojae isolates,” says Bélanger.

“These Rps genes are very precious. We need to protect them and make them last longer.”

He stresses that breeders need to make greater use of more recent Rps genes like 3a and 6. “From what we saw, about 50 per cent of the [PRR-resistant soybean varieties available in Canada] are based on Rps1c, but we know this gene has been overcome. There is also a large portion of Rps1k varieties, and that gene is being overcome.”

Discovering new Rps genes is also crucial. He notes, “Corteva has reported a new Rps gene called Rps11, and we hope it will be deployed very soon.”

Another option is to stack PRR resistance genes. At present, most Canadian PRR-resistant soybean varieties rely on a single Rps gene. A few varieties have two stacked Rps genes, but often one of the two is Rps1c or Rps1a. Stacking Rps genes with genes for partial PRR resistance also helps provide more durable resistance.

“For growers, good resistance stewardship is being aware of which pathotypes are in your field and then planting soybeans with Rps genes based on that understanding,” says Bélanger. “You can also rotate your Rps genes to reduce the selection pressure on the

pathogen.”

Other practices that can help with on-farm Rps resistance stewardship include diversifying crop rotations, so soybean is grown less often, and using seed treatments.

“You need to know what is in your field so you’ll know which Rps genes will work. That is why we developed our pathotyping technique,” Bélanger says.

“We had an advisory committee of expert scientists and when we reported our results, they recommended making the test commercially available.” So, some of Bélanger’s students involved in the research have created AYOS Technologies, which offers this testing service.

The test can use either soil or plant samples to determine what PRR pathotypes are in your field, even if no soybeans are growing there right now. The test results will tell you which pathotypes are present and which Rps genes are effective against the main pathotypes in your field. Provincial soybean variety performance lists identify the Rps genes in the PRR-resistant varieties.

Bélanger’s team is continually updating and improving the molecular test. “For example, we have already discovered Avr11 for the new gene Rps11 , even before Rps11 has been deployed. We have a bank of over 1,000 isolates, and as new Rps genes come along, we can go into our bank and find the avirulence genes that are needed for the testing,” he explains. “Also, we keep working

to improve the test by developing even better markers and faster tests.”

According to Bélanger, seed suppliers are currently the main Canadian users of the AYOS service because the test results enable the companies to make proper variety recommendations to their customers. As well, AYOS is receiving samples from other countries like the United States and Brazil.

A few Canadian growers have also embraced the value of this test. Bélanger is hopeful that more growers will do so, since choosing a variety with the right Rps genes is a simple decision that can result in big yield benefits.

To demonstrate this, Bélanger’s research group has carried out strip trials with some interested growers. After determining the PRR pathotypes in the grower’s field, they set up a trial with half of the field seeded to the grower’s susceptible soybean variety and the other half seeded to a potentially resistant variety.

“We have shown an increase in soybean yield by as much as 49 per cent just based on a good variety decision. So, I would like to say to the growers: give it a chance.”

Collaborators working with Bélanger on the new molecular method and the PRR survey include researchers from Universiteé Laval, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the University of Alberta. This research was funded by Genome Canada and Ge nome Québec, the Canadian Field Crop Research Alliance, and the Program Prime-Vert #2 #19-002-2.2-C-ULAV of Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation (MAPAQ).

If you’ve ever been one to use data, you’ll know it’s an important tool to maximize your operations. Of course, the sooner you start collecting, the sooner you’ll see opportunities. AgExpert Field and Accounting software is designed for Canadian farmers to help them make more informed decisions, potentially leading to a more profitable business. Here are three ways it can help make that happen.

1. Minimize bookkeeping errors. AgExpert’s premium feature, MyFarmConnect, allows users to integrate with select partners. Automatically download transactions with Plaid , AgExpert Accounting’s newest MyFarmConnect partner and reduce the risk of errors and eliminate manual data entry.

2. Save time on recording and sharing production data. AgExpert’s integration with McCain Foods helps potato growers easily report their sustainability requirements. This intuitive and secure connection helps them save time by linking their production data.

3. Make more informed business decisions. Recording your farm data already has its benefits. But with the integration of MyFarmConnect partners such as FieldView, John Deere Operations Center, and GrainFox , farmers can further streamline daily operations and uncover more opportunities to increase profitability.

Learn more ways how AgExpert and MyFarmConnect can help you make more informed business decisions at AgExpert.ca

New research examines the benefits of – and barriers to – long-term cover crop adoption.

by Julienne Isaacs

Laura Van Eerd might be one of the busiest cover crop researchers in Canada – if not all of North America.

A professor of sustainable soil management at the University of Guelph, Ridgetown Campus, Van Eerd’s work focuses on nitrogen and carbon cycling in agroecosystems. Two recent publications on cover crops look at different aspects of how cover crops can be used to boost agroecosystem services, such as storing carbon, while also improving farm economics – for example, via yield boosts.

Sustainability, for Van Eerd, has to do with both the environment and the farm gate.

One study, a long-term cover crop experiment comparing four different cover crop types to a no-cover crop control that began back in 2007, looks at cover crops grown in a processing vegetable system and in a grain production system. The goal of the study is to assess the ability of the different cover crop treatments to store carbon –and to provide economic returns.

The study is divided into two sites; the study at site A began in 2007, with another site added in 2008.

“We have five treatments – a no-cover crop control, which we keep weed-free in the fall, and then we have oats, rye, radish and a mixture of rye-radish. The rye we’re using is a winter cereal rye,” Van Eerd says.

“If we think back 15 or so years, it was pretty novel to [grow] two cover crops at the same time. Now it’s less so.”

The grain crops used in the study are corn, soy and winter wheat.

Analysis of data collected from the first nine years of the study at each site found that the total amount of plant carbon added to the soil via cover crops did translate into greater soil organic carbon content, Van Eerd and her co-authors write. In vegetable crops, greater yields and reduced yield variability did suggest the long-term potential of cover crops in boosting agroecosystem resilience.

However, in grain crops, the authors found that profit margins were likely to decrease with the use of cover crops – a finding partially explained by the inclusion of wheat in the study when wheat prices were low, and by the necessity of using a herbicide to terminate cereal rye before planting.

What this means, the authors conclude, is that more research is needed to identify the cover crops that are most likely to boost

profits in grain systems – and that a carbon-capture compensation program could provide incentive for adoption of cover crops.

Another of Van Eerd’s recent publications on cover crops uses a different zoom scale.

It’s a review of the impact of cover crops on the Earth’s biosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere across North America, and explores barriers to the adoption of cover crops in agroecosystems.

Cover crop termination techniques, added cost from cover crop integration, uncertainty around economic returns with cover crops

and designing crop rotations to fit cover crops were some of the major barriers limiting the adoption of cover crops in production systems, they write. But cover crops offered a wealth of benefits.

“Overall, the review results suggest that cover crops increased subsequent crop yield, increased soil organic carbon storage, increased weed suppression, mitigated N2O emissions, reduced wind and water erosion, suppressed plant pathogens, and increased soil microbial activity and wildlife biodiversity,” the authors conclude. “However, the magnitude of benefits observed with cover crops varied with cover crop type, location, and the duration of cover cropping.”

It’s a lot to parse. But what Van Eerd thinks farmers can learn from this research is that the interactions between crops and cover crops is extremely complex.

“Cover crops are promoted for many different beneficial things. Right now, we think of cover crops as this one thing, but it’s not just one thing,” she says. “There are lots of different types of cover crops. There is a list of 30 different cover crops that will work very well in Eastern Canada. Each species has a different function or thing that they’re good at.”

For example, some cover crops grow very quickly and cover the soil quickly; these quickgrowing species can help boost yields. Other cover crops suppress pathogens. The challenge, says Van Eerd, is in identifying which cover crops can be grown after you harvest your crop and still have time to do what you want them to do.

It sounds overwhelming, but there are many tools to help with decision making. One such tool is the Cover Crop Decision Tool, hosted online by the Northeast Cover Crops Council. Producers can select cover crops based on their desired effects. The tool was built using local data and information sourced from researchers, extension workers and growers.

Van Eerd is currently conducting research with scientists in New Liskeard looking at cover crop biodiversity, asking whether it matters whether you’re planting one or many species of cover crops together, and evaluating the efficacy of using cover crop biostrips in corn.

Another study, conducted at the longterm cover crop site, will look at the yield response of corn to multiple years of cover crops or one year of cover crops versus no cover crops.

“The work is ongoing, [but] we are see -

ing some difference in terms of corn response, where the corn is yielding higher with the long-term [cover crops] than the no-cover crop, [with] the one year of cover crop use in between,” she says.

As Van Eerd and her collaborators continue to gather data, their results and recommendations will become more nuanced commensurate with the complexity of the experiments. But one thing is very clear.

“Plant any cover crop and you will see benefits,” she says. “Choose the one that fits best with your other needs.”

It’s a fact — you’re an expert. Whether it’s knowledge passed down through generations or just pure hard work, your instincts help you day after day. So does your data.

not a hunch when it’s backed by facts.

When you collect, reflect and project with software for field and finance, you upgrade what you know. And you know that smart decisions are driven by data. For a fact.

Adjusting chemical fertilizer rates for differences in nutrient availability in manure-amended soils.

by Carolyn King

The 4R nutrient management system – using the right nutrient source at the right rate, right time, and right place to meet the crop’s needs – is well known as a system to help increase farm profitability, reduce the risk of environmental impacts, and improve sustainability.

However, Ontario’s 4R recommendations were developed for cropping systems in which only chemical fertilizers are used. What about 4R practices for fertilizers applied to manured cropping systems?

Tiequan Zhang is leading a five-year project to fill that important information gap.

A look at the issues

“There were several reasons why we were thinking about the need to develop 4R for chemical fertilizer applications for manure-amended cropping systems,” says Zhang, a senior research scientist focusing on soil fertility and environmental quality with Agriculture and Agri-

Food Canada (AAFC) in Harrow, Ont.

“We have had two long-term manure field studies that have been conducted for 14 or 18 years, respectively, in southwestern Ontario. The results of these two studies have shown that soil organic carbon or organic matter builds up with time in various ways depending on the manure type, form and rate applied.”

The findings also indicated that this organic matter build-up from manure could have important effects on the availability of both nitrogen and phosphorus to crops.

He explains that the breakdown, or mineralization, of organic nitrogen from manure organic matter makes nitrogen available to crops. However, not all of the organic nitrogen is released during the year of manure application. As the remaining nitrogen is released over the

years following application, it can have a legacy effect of increased nitrogen availability.

Zhang says, “This released nitrogen can either be used by crops or lost to the environment, such as into the air as greenhouse gases or into the water [which can harm water quality].”

Regarding phosphorus, he explains that manure not only adds phosphorus to the soil but also changes the soil chemistry in a way that reduces the capacity of the soil to fix phosphorus. Both of those factors increase phosphorus availability, which means phosphorus can build up very quickly in manured soils.

If the extra phosphorus is not used by crops, it can be lost to nearby water bodies through surface runoff and/or tile drainage, degrading water quality. Zhang notes that phosphorus loads from agricultural land in southwestern Ontario are a major cause of excessive phosphorus levels in Lake Erie, which can result in toxic algae blooms.

“Because the current Ontario fertilizer recommendations were developed based on chemical fertilizer application only, those recommendations do not consider the legacy aspect of nitrogen from manures and the enhanced availability of phosphorus, which are unique to manured soils.”

This consequently enhances the availability of both soil nitrogen and phosphorus to crops.”

“Because the current Ontario fertilizer recommendations were developed based on chemical fertilizer application only, those recommendations do not consider the legacy aspect of nitrogen from manures and the enhanced availability of phosphorus, which are unique to manured soils,” Zhang explains.

“With manure applications, you are improving soil health, soil aggregate stability, aeration, water-holding capacity and temperature.

As a result of these different factors, using the current 4R recommendations when applying chemical fertilizers to manure-amended soils could lead to applications in excess of the crop’s needs. And that would be a waste of costly chemical fertilizer inputs, increase the risk of nutrient losses to the environment, and reduce farm profitability.

In addition, Zhang explains that the current Ontario fertilizer recommendations do not consider the effects of soil texture on manure nitrogen availability, which could affect whether the crop’s nitrogen

The Canadian Potato Summit aims to advance potato production by providing insights from industry experts and stakeholders. Join fellow growers online for annual updates in agronomic practices and market updates.

supply is too low, just right, or too high.

“Soil texture influences factors like soil moisture content, heat, aeration and microbial activities, which all affect the breakdown of organic matter compounds, nitrogen availability, and the risk of nitrogen losses to the environment.” For instance, sandy soils may have more nitrogen released from organic matter breakdown, but also more nitrogen lost from the soil due to leaching. Clay soils may lose more nitrogen to the air through denitrification.

Zhang notes, “These organic matter and soil texture effects on the availability of nitrogen and phosphorus have not been investigated very much in the past in Ontario fields.”

The overall goal of Zhang’s project is to develop 4R-based recommendations and identify optimum chemical fertilizer application rates in manure-amended cropping systems in Ontario. The project uses an ecosystem approach that considers the effects on cropping productivity and the environment.

To achieve that goal, Zhang and his research team are working on several objectives that will enable them to flesh out the detailed specifics of nitrogen and phosphorus availability in these manured cropping systems.

One objective is to determine manure nitrogen availability from various manure types and

forms in the year of manure application and in the years after application, in soils with different textures. The second objective is to determine phosphorus availability from various manure types and forms in the application year and over the longer term. And the third objective is to investigate the interactions between manure and chemical fertilizers to see how those interactions relate to crop uptake, nutrient-use efficiency and yields, and to soil health.

“In our project, we are using a corn-soybean rotation as the cropping system. This crop combination is very typical not only in southwestern Ontario but also province-wide. We are using both greenhouse studies and field studies,” he says.

“For the greenhouse studies, we use soils collected from farmers’

“Soil texture influences factors like soil moisture content, heat, aeration and microbial activities, which all affect the breakdown of organic matter compounds, nitrogen availability, and the risk of nitrogen losses to the environment.”

Nov. 20 | 11:00 a.m. ET

Tactics to prevent soil erosion over winter

Nov. 23 | 1:30 p.m. ET

Soil sampling and fall fertilizer application

Speakers

fields which have been manured or non-manured on a long-term basis, and also soils with different textures.”

The field sites are long-term corn-soybean plots with a range of nutrient application histories. They are located in southwestern Ontario and have different soil textures.

The greenhouse studies and especially the field studies include a broad range of treatments. “We have different types of manure – cattle and pig – and different forms of manure – liquid and solid. And we have combinations of chemical fertilizers with manures in various ratios.”

Across the different treatments, they are analyzing data on many different factors, such as crop yield, nutrient uptake and removal, and nutrient-use efficiency. They are also tracking changes in such soil properties as soil organic carbon, soil mineral nitrogen and soil test phosphorus. And they are monitoring nitrogen and phosphorus losses to water so they can evaluate the impact on water quality.

Based on the results of these studies, they’ll develop optimal chemical fertilizer 4R recommendations that take into account the manure type, form and rate, the soil texture, and the ratio of manure to chemical fertilizer.

Interesting preliminary observations

Zhang’s project started in 2022 and runs until 2027, so it is still in its early stages. However, he notes, “Since we are using long-term sites that means we can use some data collected from the previous years or from last year to tell some preliminary stories.”

First of all, he sees a number of interesting patterns in the phosphorus data. One is that the availability of soil test phosphorus (an index to indicate the amount of soil phosphorus available to crops) in manured soils can be up to three or four times higher than in soils with only chemical fertilizer applications, depending on the manure type and form and the application approach (nitrogen-based or phosphorus-based).

Specifically, soil phosphorus looks to be more available in soils amended with pig manure than with cattle manure, and in soils amended with solid manure than with liquid manure. Also, phosphorus seems to be more available in soils amended using the traditional nitrogen-based manure application approach than using the newly recommended phosphorus-based application approach.

“Secondly, building on the results from last year’s field study, it seems that the application of animal manure alone or in combination with chemical fertilizer phosphorus enhances soil phosphorus availability for crop production. This is a preliminary confirmation of our hypothesis that organic matter from animal manures changes the soil phosphorus chemistry and may improve the availability to the crops,” he says.

“So that tells us that we do need to improve or develop the 4R

fertilizer management practices for crop production systems that previously or currently receive manures.”

Zhang explains that the results from this study could help Ontario farmers to make optimal use of both chemical fertilizers and manure resources, resulting in significant economic and ecological benefits.

In particular, the 4R recommendations for chemical fertilizer use in manure-amended cropping systems could help farmers to reduce their fertilizer inputs, better match their nutrient applications to the crop’s needs, and maintain or even improve crop yields.

The recommendations would also help farmers avoid overapplication of fertilizers and manures, thereby reducing the risk of nutrient losses to the environment. In particular, the recommendations could help farmers decrease phosphorus loads to water bodies such as Lake Erie, which are a serious environmental concern.

“With this project, we should be able to develop knowledge and technology that enable us to minimize phosphorus loads by optimizing the nutrient supply with improved use efficiency not only from manures but also from chemical fertilizers and the nutrients from the soils themselves,” he says.

The data from the project could also be used by policymakers to make science/evidence-based regulations for nutrient management and could help agronomists in developing science-based guidelines and decision tools for nutrient management so farmers can make better use of both manure and fertilizer resources.

The 4R manure-related recommendations might also encourage more crop growers to make use of local manure resources rather than relying solely on chemical fertilizers. This addition of manure organic matter to their cropping systems would improve their soil’s physical, chemical and biological health while decreasing their need for chemical fertilizer inputs.

Overall, Zhang thinks the project’s results have the potential to improve farm profitability, enhance environmental health, and increase the sustainability of agricultural production in Ontario. And that could increase the competitiveness of Ontario farm production in the long term.

“In our project, we are using a cornsoybean rotation as the cropping system. This crop combination is very typical not only in southwestern Ontario but also province-wide.”

“I’m really proud of this project, and I really appreciate the support of the industries who have recognized the importance of research on this topic,” he says. The project is funded by Grain Farmers of Ontario, Ontario Pork, A&L Canada Laboratories Limited, and AAFC.

These exceptional students are the winners of the 2023 CABEF Scholarships. We are proud to support each of them with $2,500 for their ag-related post-secondary education.

Help us empower more students to pursue diverse careers in agri-food. Strengthen the future of Canadian agriculture and food by investing in the cream of the crop.

Become a Champion of CABEF and directly support a scholarship for a Canadian student.

Sarah MacDonald Vanderhoof, BC Erin Hughes Longview, AB Wyatt Pavloff Perdue, SK

Milan Lukes Winnipeg, MB

Kyla Lewis Dorchester, ON Matthew Bishop Round Hill, NS

Congratulations to this year’s CABEF scholarship recipients.

Contact CABEF today to learn how you can become a “Champion of CABEF” at info@cabef.org

HOW EASY IT IS TO

TAKE THE REVEAL CHALLENGE AND SEE HOW EASY IT IS TO INSTALL AND USE.

Have you heard of ttingretrofi or upgrading your planter but you’re just not sure it’s worth it? Join thousands of other farmers who have added Reveal and experience what it’s like to move your row cleaners off of the row unit, improve your row unit ride, and keep your row cleaners engaged without bouncing. The easiest way for you to try Precision Planting this year is by purchasing one row of Reveal. WE CHALLENGE YOU TO PUT ONE ROW OF REVEAL® ON YOUR PLANTER THIS YEAR. WE BELIEVE IN BETTER PLANTERS WITH BETTER ROW CLEANERS.

Hint: Rotate this ad to reveal one of the best places to start.