TOP CROP MANAGER

Mulchbased weed control

Good biomass is key to this weed control strategy. Pg. 10

t racking soybean pathogens

Pg. 14

Fertilizer o F the F uture Pg. 24

Mulchbased weed control

Good biomass is key to this weed control strategy. Pg. 10

t racking soybean pathogens

Pg. 14

Fertilizer o F the F uture Pg. 24

Amy Petherick

Julienne Isaacs

Carolyn King

SteFanie croley | editor

The consumer conversation around genetic modification is growing, and the audience is changing.

I recently received a press release via email about a 16-year-old high school student from Toronto named rachel parent. parent is the founder of Kids right to Know and, according to the press release, is Canada’s “leading activist for the labelling of genetically engineered food.” parent recently travelled to St. Louis, Miss., to join with members of the group Moms across america to address Hugh grant, the Ceo of Monsanto. parent had two questions for grant. To paraphrase, she asked him why, if he truly believes gM technology is safe, is he hiding it rather than promoting it, and if he will commit to publishing the controlled animal feeding studies Monsanto conducted to determine the safety of gMos and round Up on the Monsanto website. The press release states grant “humbly disagreed” with parent’s views and addressed her passion on the subject.

This email was especially timely as I received it just after returning from Brandon, Man., for the annual Manitoba potato production Days. The keynote speaker this year was Kevin Folta, a professor and chairman of the horticultural sciences department at the University of Florida. Folta’s talk focused on the technology of the future and how producers can effectively communicate with the public about genetics, and made a point to remind the audience that today’s consumers are changing – and so are the sources from which they receive information. as Folta pointed out, the family decision makers are quite often moms (or dads) who care about what they are feeding their families, often overlooking the production and scientific reasons behind the decisions that farmers and companies make. Furthermore, the influencers that consumers turn to for information are changing: celebrities, social media and peer comments have such a large impact on consumers. and rachel parent’s story serves as a good reminder that today’s consumers are smarter, younger and more informed than ever before.

I’m sure we’ve all had discussions about gMos with family, friends, or perhaps even the odd stranger via social media (where articles about gMos can spread like wildfire, regardless of whether they’re balanced and accurate). Quite often, it’s a dialogue some choose to stay out of. But you’re in a unique situation to engage in the conversation and educate the consumer about what you know – what you’ve learned, what you see every day and what you believe.

Folta advised producers in Manitoba to make an effort to get on the consumer’s level and find the common ground. get on social media and share your story. You’ll likely notice there will be shared values between you: as he pointed out, many producers and consumers care about feeding their families, keeping farmers profitable and helping the developing world. personalize your message and talk to consumers about why you do what you do – how you learned to grow a crop, what you feed your family and why you’re comfortable with the decisions you make.

growers are the most credible source of information to consumers. When you identify the shared values and approach the topic from a different standpoint, you may find a new way to educate the audience.

#40065710 Printed in canada ISSN 1717-452X cIrcuLaTION email: rthava@annexbizmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-5170

Mail: 80 Valleybrook Drive, Toronto, ON M3B 2S9

subscrIPTION raTEs

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues February, March, April, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in canada – 2 issues Spring

topcropmanager.com

Tricor® 75DF herbicide is an enhanced formulation of metribuzin - the advanced broadleaf weed control that North American growers have trusted for years. A key addition to your pre-emergent weed control program in soybeans, Tricor DF is also effective in lentils and peas. Tricor DF is proven effective on a wide range of weeds, including ragweed, pigweed, chickweed, nightshade, and other broadleaf weeds. And when used as a tank mix partner, it enhances your weed control spectrum even further. So, when you need to prevent weeds from scoring on your crop, trust Tricor DF. Contact your local distributor, UPI sales representative or visit www.upi-usa.com to learn more.

The first signs of Palmer amaranth are now evident in Ontario.

by amy petherick

There’s some debate about when to sound the alarm on palmer amaranth. Those struggling to help farmers combat the weed in the United States insist the sooner, the better. Folks who know eastern Canada assure farmers it isn’t time to panic. Yet.

palmer amaranth, known more commonly among american farmers as palmer pigweed, has been traveling north through the midwestern states, ohio, pennsylvania and now Michigan. Scattered plants have also been reported in ontario, but Dave Bilyea, a weed science technician at the University of guelph’s ridgetown campus, confirms none of these isolated cases are of any concern so far. However, he does believe farmers in ontario do need to be vigilant moving forward.

“They are very difficult weeds to control in the U.S., so we sure don’t want to see them in any large populations in ontario,” Bilyea says. “people could deal with small pockets of these weeds fairly easily but if they were to be ignored for any length of time, they could be problematic on a farm by farm basis.”

For a root-bound organism, palmer amaranth is demonstrating an excellent ability to travel. as a weed seed, it is exceptional at hitching rides on agricultural equipment, hidden within grain or wrapped up in bales of all kinds. Bilyea says that the plants that have been found in ontario would seem to have travelled here by rail. He notes that a recent study by the University of Missouri has proven that the weed isn’t depending on human traffic alone

however. Both geese and ducks feed on palmer amaranth and water hemp, including in areas where the weed has manifested a resistance to glyphosate, and the seed is still viable after passing through the digestive system.

“That might be one way that resistant species could show up here but, that being said, we haven’t seen that yet. It could happen because we’re on a major flyway here,” Bilyea says. He adds that weeds could start to appear on the shorelines of waterways where these geese and ducks are more likely to land, but this is all just theoretical.

But Jason norsworthy, a leading weed specialist at the University of arkansas, says rail travel is certainly not theoretical and he has a report, conducted by one of his post-doctorate students a few years ago, which shows rail to be one of the major means of transport for resistant weeds and palmer amaranth in particular. The challenge – which has been well documented in the States – he says, is that even when farmers know the weed is in their area, they historically do not notice it until it’s too late.

“generally 20 per cent of a field or population has to succumb to a level of resistance to be noticeable,” he says. “With palmer amaranth, at 20 per cent, the cat’s out of the bag.”

AbOVE: Dave bilyea of the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown Campus says the most striking thing about Palmer amaranth is that it has the very long petioles. The petiole is longer than the leaf itself as it grows.

We rethought every inch of the new Case IH 2000 series Early Riser ® planter with your productivity in mind. We applied Agronomic Design™ principles to make it simpler, faster, more durable and more productive. And we provided you with a bundle of industry firsts — from our rugged new row units that create the only flat-bottom seed trench to our state-of-the-art in-cab closing system — that give you even more control. The result is unmatched accuracy and emergence for a better plant stand and, ultimately, yield. Start rethinking productivity today at caseih.com/newearlyriser

norsworthy says farmers would have to get down on their hands and knees to identify the differences between very young redroot pigweed and palmer amaranth. Misidentifying the two can result in a few hundred thousand more seeds per plant, however.

norsworthy says this weed’s ability to produce seed dominates others so entirely that, if palmer amaranth is found in a field, every weed management decision made will be centered on palmer amaranth.

Soybeans are hit the hardest because atrazine remains effective and is still used widely for corn production, while the winter wheat crop season naturally evades the summer annual. Tillage buries the seed and reduces the likelihood of survival, so no-till systems are at a higher risk of infestation and he says cover crops offer a good physical barrier management option. Still, norsworthy insists growers think hard about spraying glyphosate on any palmer amaranth alone.

“I understand commodity prices are tight and times are hard, but if you want to still be using glyphosate five years from now, you’d better start using some residual herbicides,” he says.

In research studies where several collaborators have worked together to find herbicide management strategies that can control the troublesome weed, norsworthy says they had to move to the new trait technologies in order to achieve 94 per cent control. He said they found that Monsanto’s coming Xtend system and Dow agrosciences’ enlist technologies were comparable to one another, while HppD technologies, if applied in a timely manner, were superior.

If application timing was delayed in the HppD system from three or four weeks to six or seven weeks, however, these fields were far more difficult to salvage. He says his recommendation for keeping control is to burndown with glyphosate and dicamba four or six weeks before planting, then apply a paraquat plus a residual herbicide at planting, then spray a glyphosate tank mix 21 days later. Waiting six weeks is too long for good post-emergence control, he says.

“Yes, we were able to kill a lot of weeds, but we were never able to get back to the level of weed control that we had when we made those timely applications of a residual followed by a subsequent post application at three to four weeks,” norsworthy says. “When we got into a salvage situation, it turned into just that, even with the new technologies.”

Both norsworthy and Bilyea have been actively speaking to farmers about palmer amaranth throughout the winter, trying to raise awareness so farmers are well prepared to identify the weed in the coming growing season.

norsworthy says it’s something he believes farmers in ontario should be at least a little bit afraid of, or else he’s afraid they won’t be motivated enough to protect themselves against it.

no matter what the perceived risk, Bilyea would simply rather see farmers participate in survey initiatives such as the one he has initiated this year. He hopes to use the results in a seminar he’ll be delivering this July as part of the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food, and rural affairs’ annual Southwest Crop Diagnostic Days.

A NEW WORLD DEMANDS NEW HOLLAND.

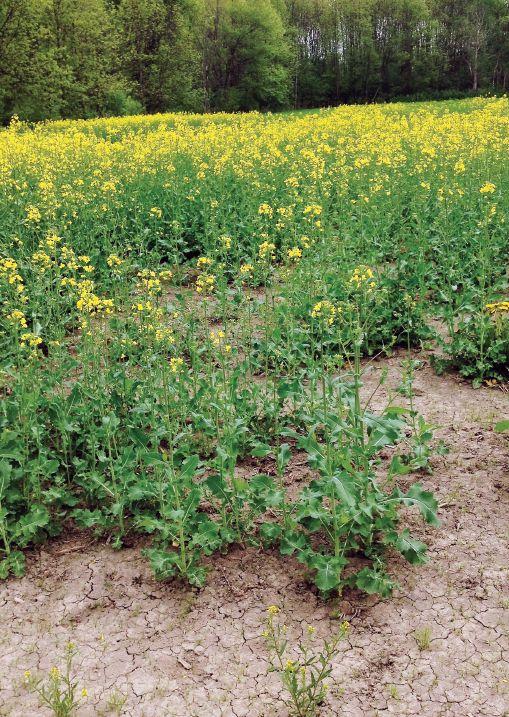

Good biomass is key to this weed control strategy.

by Julienne Isaacs

Nobody is more familiar with the fight against weed pressure than organic farmers, but one weed control strategy that works in organic settings might be just as beneficial for conventional growers, according to a Laval University researcher. The secret is mulch.

Caroline Halde, a professor in the department of plant science at Laval University in Quebec, says cover cropping for weed control is a proven strategy in organic studies. But she’s also had plenty of interest from conventional no-till growers in the use of cover cropping.

“I’ve had no-till farmers come to me who are working with cover crops more and more, and now they are ‘almost organic’ because they use very little inputs in their cropping systems,” she says. “and now they want to make the switch because they’re almost organic but don’t get the premium.”

But mulch-based weed control takes cover cropping one step further. In year one, a cover crop is planted as green manure. In year two, a cash crop is planted directly into the mulch, with the mulch serving as the grower’s only form of weed control.

Halde, working under the supervision of Martin entz, a professor

of plant sciences at the University of Manitoba, completed a study investigating the use of mulches in an organic high-residue reduced tillage system near Carman, Man., in 2013. In the study, barley, hairy vetch, oilseed radish, sunflower and pea were used as cover crops, then planted with wheat.

The best cover crop for weed control and cash crop yield was hairy vetch or a barley-hairy vetch mixture.

“green manure mulches with hairy vetch were effective at reducing weed biomass by 50 per cent to 90 per cent in the no-till spring wheat in 2011 and 2012, compared to other mulches,” Halde concluded.

The method is not a magic bullet. Halde says high cover crop biomass is key to achieving good mulch that will effectively choke out weeds the following year.

“First, you have to have a good establishment of your cover crop – that’s rule number one,” she says. poor or excessively wet weather

AbOVE: Wheat emergence in a no-till hairy vetch/oat mulch in Truro, N.S.

Reach for Wolf Trax Zinc DDP ®, the nutrient tool that is field-proven by corn growers like you.

With our patented EvenCoat™ Technology, Wolf Trax Zinc DDP coats onto your N-P-K fertilizer blend, delivering blanket-like distribution across the field. Plus our innovative PlantActiv™ Formulation ensures the zinc is available early, when corn needs it most.

Have your dealer customize your fertilizer blend with Wolf Trax Zinc DDP, and see how the right zinc can boost your corn crop and the bottom line.

in the spring might hamper cover crop growth. “and another thing is to choose fields that have low weed seed banks, or at least for some particular weeds, particularly wild oats.” In Halde’s study, wild oats and perennial weeds, such as dandelion and Canada thistle, made for challenging conditions.

Halde’s study relied on removing a field from production for one full year each cycle, but she says the payoffs can be rewarding. In Western Canada, the benefits of such a system involve water conservation as well as weed control. In eastern Canada, removing herbicides from a field for a year would also be a major boon for growers nervous about herbicide resistance. “That would be a great advantage, because we see more and more herbicide-resistant weeds in eastern Canada,” she says.

But Halde is currently seeking funding for a study in eastern Canada on the use of fall cover crops used as mulch in the spring and planted with short-season cash crops – a system which would keep fields in production, so growers do not have to lose a year each cycle.

Carolyn Marshall, a phD student at Dalhousie University, is currently studying the impacts of no-till green manure management on soil health in organic grain rotations on two sites – at Carman, Man., under the supervision of Martin entz, and at the Dalhousie agricultural Campus in Truro, n.S., under the supervision of Derek Lynch. The project, which is funded by the organic Science Cluster through agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC), began in 2013 and will conclude this year.

She says cover cropping shows enormous promise for weed control in both organic and conventional systems. “I would love to see more use of cover crops in all systems. I think they can solve all kinds of problems,” she says.

Marshall’s project is focused on determining how green manure

termination method affects soil health in organic grain rotations, with three tillage intensities applied on all plots: no-till, minimum tillage and spring and fall tillage.

at Carman, Marshall’s team is employing a four-year rotation of hairy vetch-wheat-fall rye-soybean plus a red clover-red cloverwheat-soybean rotation. at Truro, the experiment is testing two green manures – pea/oat, and hairy vetch/barley, each followed by a wheat-fall rye-soybean rotation.

In the first round at Truro, Marshall says, “We had really good growth of the green manure. Some plots got up to 10 tonnes per hectare of biomass, and it was really effective at stamping out the weeds.”

When the experiment was repeated in 2014, a dry spring resulted in limited growth and very thin mulch. “The weeds went berserk in the no-till plots,” Marshall says. “Weed control seems to really depend on getting enough biomass to get a thick enough mulch, and that really depends on the weather.”

Termination methods matter, too: when mulches were mowed in the fall at Truro, they decomposed, leaving too little mulch on the soil surface in the spring. When a roller crimper was used instead, the cover crops continued to grow until winterkilled, resulting in heavy mulch cover in the spring.

“researchers in north Dakota, georgia and new england are also finding that if you don’t get enough biomass to suppress the weeds, they’ll take over your cash crop and cause a lot of problems in a very short time,” she says.

It’s early days for this research, but both Halde and Marshall are enthusiastic about the potential for mulch-based weed control in organic and conventional systems alike. “In conventional systems you can use different crops to get more consistent mulch levels, which has a lot of potential to help with long-term control,” says Marshall.

Finding new ways to control soybean diseases.

by Julienne Isaacs

In order to control diseases in the infamous seedling disease complex – including seed rot, root rot, seedling blight and damping off – you have to track the pathogens responsible.

allen Xue, a plant pathologist at the o ttawa research and Development Centre, has been attempting to do just that since he started working as a soybean pathologist at the centre in 2009.

“I did some checking for the diseases in the field that spring, and I got a lot of reports from albert Tenuta, field crop pathologist for the o ntario Ministry of a griculture, Food and rural affairs, saying that lots of farmers had seedling disease problems in the newer areas,” he says.

Xue investigated and found patches of plants that were soft and rotting. He suspected pythium or its close relative, phytophthora, and found that, in one case, the disease was in fact caused by pythium in the early stages. But in dry areas, Fusarium or

rhizoctonia are often responsible for rot.

“We decided we needed to sort out what are the pathogens that are involved,” he said.

In 2014, Xue wrapped up a project identifying sources of resistance to the pathogens that cause some of o ntario’s most devastating diseases in soybean.

“There are some similarities between the diseases, but plant research for different pathogens is quite different, so you have to look at the diseases one by one,” he explains.

“ e ach pathogen is controlled by specific genes. You can’t apply Fusarium research to pythium. The most effective way to control disease is to use genetic controls for resistance. But you have to know where the target is and how to screen for the pathogen.”

The goal of Xue’s research: to identify resistant germplasms

AbOVE: Symptoms of root rot complex in a commercial field.

The study paid off.

Xue and his team identified six different pythium species responsible for seed rot and damping-off, four of which had not previously been reported on soybean in Canada.

It’s an important discovery, but a sobering one. “These species are not new to the rest of the world,” Xue says. “In the past, soybean production was only a rumour in southwestern o ntario, but now that soybean has been growing in short-season areas in prince e dward Island, o ntario and Manitoba – in cold climates – now pythium has become a problem,” he says.

Through analyzing the effects of changing temperatures, the team zeroed in on the changing pathogenicity of pythium. “We discovered for the first time that P. ultimum var. ultimum was the most pathogenic species to soybean in Canada,” Xue says.

But the study’s results were not confined to pythium. Xue also identified 22 races of Phythophthora sojae , the causal agent of p hytophthora root rot—“the most destructive and widespread disease in Canada”—17 of which, Xue claims, had not yet been detected in the country.

“This new information was crucial to appropriately target deployment of resistance genes in new cultivars by soybean breeding programs,” he says.

Finally, the team identified nine Fusarium species responsible for Fusarium root rot in o ntario.

Xue says the results provide improved knowledge of the pathogen complexes, which is essential for developing better controls.

now, breeders can use this information on the predominant races, or races with specific virulence genes, when screening their breeding lines. The goal is cultivars with resistance genes to the most devastating races; they’ll have a longer lifespan, but they’ll also form a foundation for future cultivar development.

e lroy Cober, a research scientist involved in soybean breeding and genetics at the o ttawa research and Development Centre, was Xue’s collaborator in the project.

p lant breeding is a long process, Cober says. o nce the parents are chosen, breeding, start to finish, takes seven to 10 years.

“The first phases of breeding involve making a cross. Then you do inbreeding to get pure lines and then you test the pure lines. right now we’re in the inbreeding phase,” he says.

Cober says that yield is always the priority in soybean breeding programs, but disease is also a major focus. He says the long-term nature of plant breeding is a reality everyone in the industry needs to keep in mind, but there are payoffs in the end. “There’s not an immediate payback, but there is a payback,” he says.

While Xue’s project yielded important results, he emphasizes that the work is not over yet. “There is lots to do in terms of monitoring pathogen dynamics and monitoring techniques and then breeding and studying the inheritance of resistance,” he says.

by Julienne Isaacs

This past year, ontario saw a huge swing away from notill to conventional or minimal tillage, according to Horst Bohner, soybean specialist for ontario Ministry of a griculture, Food and rural a ffairs (oM a Fra). The problem? Maize residues are impacting soybean yields in the following year – or so producers believe.

In 2014, the province had a late fall, followed by a cold hard winter with little thawing, followed by a very dry spring. “That led to a tremendous amount of corn residue in the spring of 2015, and then on top of that, we had a frost on May 23, and if you have a lot of residue on the surface frost does a lot more damage,” Bohner says.

and as of 2015, “every other field is black in perth County,” he says. “In ontario, we’re very frustrated with corn residue and quickly going away from no-till.”

The cultural change has been underway for a number of years. Back in 2008, Bohner, in co-operation with the University of guelph, was already analyzing different tillage and residue removal treatments. He’d observed that many growers were shifting back

to intensive tillage due to the belief that maize residues hindered soybean performance. Bohner’s work interested Michael Vanhie, a masters student under the supervision of Bill Deen, an associate professor at the University of guelph, who decided to focus his research on soybean response to the management of crop residues.

over the course of two growing seasons, Vanhie – now a field development representative for Dupont – set up a field experiment in three commercial fields to test the response of soybeans to maize residue management.

The experiment was set up to analyze three rates of removal: no removal, intermediate removal of residue (some residue, including stalks and leaves, removed), and nearly complete removal of residue (removal of as much residue as possible without disturbing the soil). The study involved 10 tillage systems and stalk chop treatments across all levels of residue removal.

AbOVE: Despite large visual differences in early season soybean growth (no removal on the left, complete removal on the right), where corn residue was removed, it did not lead to significant yield increases.

Nu-Trax P+™ with CropStart™ Technology puts you in charge of delivering the nutrition crops need for a strong start. And a strong start can lead to a better harvest.

It features an ideal blend of phosphorus, zinc and other nutrients essential for early season growth. With patented EvenCoat ™ Technology, Nu-Trax P+ is coated onto your dry fertilizer blends. And with blanket-like distribution across the field, it’s placed close to young plant roots where they can access the nutrients earlier, especially in cold and wet soils.

This spring, take control of your crop’s early season nutrition. Ask your retailer for Nu-Trax P+.

Rethink your phos

The team also examined the effects of various planter types. They used a no-till planter drill in some subplot treatments, and a no-till row unit planter in others.

The results? Shallow fall and/or spring tillage did not result in higher soybean yields compared to no-till alone.

“The no-till system was one of the most competitive systems,” Vanhie says.

But there were other noteworthy results. For example, Vanhie’s team utilized a stalk chopper to try to speed decomposition of residues in one subplot treatment. When soybeans were planted using a drill planter in no-till fields after residues had been stalkchopped, yields decreased.

“It resulted in more residue on the soil surface with a thicker mat. as you went through with the drill to plant, it wasn’t as capable of pushing the residue aside and there was a shallower seeding depth,” says Vanhie. When the row unit planter was used, however, there was no yield hit, as it was capable of manipulating the chopped mat of residue.

Vanhie says that the benefits of zero tillage have been thoroughly documented; no-till results in reduced fossil fuel consumption and erosion. In most cases, he says, research has shown that no-till results in either higher yields or no yield reduction, meaning that growers usually see higher profits by using no-till.

“In our study, no-till yielded numerically better than most systems,” he says. “But there are many, many factors that affect yield – moisture, soil type and genetics, for example, and these can all have an impact on a yield response.”

Vanhie’s study involved medium-textured soils and moderate

weather conditions. “When you see a no-till yield hit it is usually in a wet year where the soil is slow to warm up, and on heavy clay soils where you have poor drainage. That’s where you’d have a benefit to tilling the soil,” he says.

Bohner agrees. “How big of an issue corn residue is going to be is highly dependent on the growing season, and during those years of the project, the corn residue was not as big of an issue as we thought it might be.”

But the biggest influence on producers’ cultural practices is not research at all, but other producers’ opinions about what works.

“You can have all the research in the world to show that no-till works and yields just as much, but if there’s a feeling in the countryside that conventional tillage is more robust and yields better, people will go back to tillage wholesale and they don’t really count research as high on their list as what the neighbour is doing,” Bohner says.

oMaFra’s recommendations are tailored to this reality. These days, oMaFra recommends producers leave at least 30 per cent residues undisturbed on the soil surface to reduce the risk of erosion – in effect, reverting to minimal tillage instead of intensive tillage.

Bohner says residue management will be key in the years to come as corn residue biomass continues to increase. Corn yields are much higher than they were in the past, he says, while bean yields are relatively low. “nobody wants soil erosion, and we all have to work on reducing that. one of the ways is minimal tillage versus plowing.

“You have to get a good crop, so some form of residue management is becoming more important in modern soybean production.”

A Dalhousie scientist assesses integrated disease management options for stem rot and blackleg.

by Carolyn King

Canola production in the Maritimes has good potential – canola grows well in the region’s climate and has a higher value than some of the small grain crops typically grown in the region. But one of the barriers to increasing canola production is disease. So Balakrishnan prithiviraj, an associate professor at Dalhousie University’s agricultural campus in Truro, n.S., is working on two projects to assess integrated management strategies for two important canola diseases.

The diseases are sclerotinia stem rot (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) and blackleg (caused primarily by Leptosphaeria maculans). Both these fungal diseases are found across Canada’s canola-growing regions, and both can have major yield impacts on canola. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum has a very wide host range including many broadleaf crops and weeds. Leptosphaeria maculans affects cruciferous plants like canola and cabbage.

From what prithiviraj has seen, stem rot is a much more serious problem in the Maritimes than blackleg. “This region is the perfect recipe for stem rot because it has exactly what is required for the development of the disease,” he says. Weather conditions in

the Maritimes often favour the stem rot, and other host crops, such as potatoes, are commonly grown in the region.

“The annapolis Valley area, where we’re running our canola trials, is the vegetable belt. They grow a lot of cauliflower and broccoli, as well as soybean, [which are all susceptible to sclerotinia stem rot,] so the area has become a hot spot for this disease,” prithiviraj notes.

He adds, “It was a disastrous year here for stem rot in 2015. The summer weather had been warm for a while, and then it was humid for a long period of time, which is perfect for development of stem rot.”

Rotation and fertilizer effects

one of prithiviraj’s projects is evaluating the effects of crop rotation and nutrient management on the incidence and severity of stem rot and blackleg.

AbOVE: The rotation study involves canola, wheat, corn and soybean in 16 different rotation sequences.

Initially, prithiviraj conducted the project at the university’s research farm at Truro. But for the past two years he has piggybacked his project onto projects of his Dalhousie colleague, Claude Caldwell, being conducted in Canning, in the annapolis Valley region. Caldwell is involved as a co-operator and leads projects that are assessing the effects of nutrient management and crop rotation on canola yields. prithiviraj’s project fits really well with that work, plus the collaboration is lowering prithiviraj’s project costs by almost 60 per cent.

The rotation study involves four crops (canola, wheat, corn and soybean) in 16 different rotation sequences. Canola follows each of the other crops every year in one of the rotations. The rotation study started five years ago, so the rotations have all gone through at least one complete cycle.

although prithiviraj’s project has three more years to go, he’s already getting some interesting preliminary results on the effects of rotation on disease. “Based on the two years of data, we had the least canola disease when corn preceded canola. Second best was when wheat came before canola. When soybean was before canola, we had a little more canola disease, which might be because sclerotinia is an issue in soybean. We had the most disease with the canola-canola rotation.” Corn and wheat are not hosts to stem rot or blackleg.

The rotational effects were easy to see just by looking at the plots. He says, “Where corn preceded canola, we had a beautiful canola crop. We could see a dramatic difference between the plots where corn preceded canola and the other rotation plots in terms of the height of the canola crop and the flowering intensity. However, this dramatic difference in appearance and disease level has not consistently translated into a significantly increased seed yield.”

The continuous canola plots were almost like a textbook illustration of just how bad disease levels can sometimes be in a monocropping system. “In 2015, to our surprise, there was so much dis-

ease in the continuous canola rotation that we couldn’t collect any data from it; it was completely devastated by disease. There was not enough canola remaining by the time plants had reached podset to make any assessment of sclerotinia or harvest any seed. There was stem rot in very early phases, but the main cause of the canola death was clubroot. about 80 per cent of the plants were infected severely in the continuous canola plots.”

The nutrient management project is evaluating the effects of sulphur, boron and nitrogen application rates.

“We’re looking at sulphur because, as we all know, sulphur nutrition is very important for canola,” prithiviraj notes. The researchers are applying this nutrient as ammonium sulphate and comparing four rates (zero, 10, 20 and 40 kilograms per hectare), alone and in combination with different nitrogen rates. Based on the results so far, the sulphur applications aren’t having a big effect on disease levels.

Canola also has a higher need for boron than crops like wheat and barley. The project’s results to date show only a very small difference in disease levels with the different boron rates used in the treatments. “a higher boron level of two kilograms per hectare reduced the disease, but it was not statistically significant,” prithiviraj says.

The nitrogen response trial treatments are having the greatest effects on disease levels in canola. “Higher nitrogen always leads to more disease,” he notes. Higher nitrogen rates result in denser crop canopies, which can trap moisture, favouring stem rot and blackleg.

This project will continue for the next three years.

prithiviraj’s other project is focusing mainly on the use of seaweed bioproducts to manage stem rot and blackleg. “another area of research in my laboratory is using marine bioproducts to improve plant health, for example the use of seaweed extracts – chemicals

derived from seaweeds – to see if they can reduce the incidence and severity of disease. I’ve been working on this for 10 years, since I arrived in nova Scotia. We have lots of seaweed here, and I work with a seaweed extract company here; it is one of the largest seaweed bioproduct companies in the world,” prithiviraj explains.

In the stem rot and blackleg project, prithiviraj’s lab is examining the possibility of reducing the use of fungicides by using them in combination with seaweed bioproducts. For the past two years, the researchers have been comparing the effects of various combinations of these products in greenhouse trials.

The results are very promising. “We’ve found that using a fungicide at around 10 per cent of the recommended dose along with the seaweed extract gives almost the same effect as using 100 per cent of the fungicide’s recommended dose. That could be a huge benefit, not only for farmers in terms of the cost but also for environmental stewardship,” he says.

As part of an integrated disease management project, Prithiviraj is studying how crop rotation affects disease levels in canola at a site in the Annapolis Valley.

the fungicide. also the seaweed extract by itself works almost like a vaccine, inducing an immune response in the plant.”

“We are still studying how exactly [the seaweed extract] works, but our initial results show that it’s partly a surfactant effect, because the seaweed has very good surfactant properties. So when we use it in combination with fungicides, it improves the activity of

He adds, “We’ve done this work in other crops also, and we’ve found similar effects, for example in potatoes. So my major focus at the moment is to see if we can fine-tune the technology so growers can adopt it.

“although seaweed extract is not widely used in Canada, it is being used in other areas, like California and other parts of the west-

ern United States, especially on high-value crops like grapes, apples and vegetables. The company that I work with exports its products to 70 countries around the globe. Seaweed extract is mainly used, not for disease management, but especially for alleviating abiotic stresses in crops.”

This year, prithiviraj’s lab will be starting field experiments with the seaweed/fungicide work in canola. They’ll be testing the most promising combinations from their greenhouse trials to see how those combinations affect disease management and abiotic stress response in canola.

prithiviraj notes, “There are two more years left in this project, but we’d like to do three years of field trials. at the end of the third year, we hope we’ll be able to identify one or two combinations that growers could adopt.”

benefits for growers according to prithiviraj, the results from his projects will help eastern Canadian canola growers by providing information on rotation and fertilizer practices for managing stem rot and could introduce some fungicide/seaweed bioproduct combinations that reduce the disease.

He adds, “Some of the results might benefit canola producers in both eastern and Western Canada, especially the fungicide combinations. Canola is extremely prone to heat stress during the flowering and seed setting stages, which is the same time we have an increase in stem rot. So applying these seaweed/fungicide combinations might be helpful not only for reducing the use of fungicides and reducing the disease, but also for alleviating heat stress effects on the crop. That’s our long-term goal, but there is a lot of work that still needs to be done.”

Both of prithiviraj’s projects are part of a series of canola and soybean projects being conducted under the eastern Canada oilseeds Development alliance. researchers in ontario, Quebec, new Brunswick, prince edward Island and nova Scotia are involved in this initiative. The projects are co-funded by the growing Forward 2 program of agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) and industry. In the case of prithiviraj’s projects, funding is from aaFC and TrT-eTgo, a major canola crushing facility at Becancour, Que. (The Canola Council of Canada is the industry leader for the growing Forward 2 canola rotation study being conducted by Caldwell, where prithiviraj is collecting disease data.)

Nightshade and other problem weeds are no match for Fierce ® herbicide. Its two modes of action provide the broadest spectrum and residual control that lasts up to eight weeks. The result is a soybean crop that sees both a yield increase and helps make grade with clean beans at harvest.

Ask your local retailer for more information.

Nanotechnology ensures fertilizer is released only when crop needs it.

by Helen Lammers-Helps

While nitrogen is key to high yields, between 50 and 70 per cent of the nitrogen applied in fertilizer is lost to the environment. This is costly for farmers and leads to environmental contamination.

now researchers are using nanotechnology to ensure that nitrogen is released from the fertilizer only as the crop needs it. This smart fertilizer will save farmers money while reducing water pollution and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. nanotechnology has been touted as the next big thing for decades, with a growing number of applications ranging from computing to textiles to medical advances. Carlos Monreal, a researcher with agriculture and agri-Food Canada and an adjunct professor at Carleton University in ottawa, has turned his attention to nanotechnology applications that will benefit agriculture.

First coined in the early 1980s, nanotechnology refers to the ability to control individual atoms and molecules. The nanoscale is less than 100 nanometres, and one nanometre is a billionth of a metre (to demonstrate the scale involved, a sheet of newspaper is about 100,000 nanometres thick). advances in laboratory equipment have made it possible for scientists to manipulate matter at the molecular level, which is much too small to be seen by ordinary microscopes.

Monreal, who first began working on the project in 2007, explains the rationale behind this nanotechnology breakthrough in simple terms. Soil microbes oxidize nitrogen found in proteins and nucleic acids in the soil organic matter into ammonium and nitrate, forming what the plant uses for growth and to make grain and foliage. When the nitrogen concentration in the soil water around the plant roots dips to a level where it becomes limiting to plant growth, the plant releases chemicals that signal the soil microbes to make more nitrogen available in a form the plants can use. In return, the microbes receive carbon substrates from the plant roots.

By identifying the molecular composition of these chemical signals that are produced by the plant roots and found in the soil solution, it is possible to wrap urea fertilizer in a polymer film with a biosensor that only releases the nitrogen in response to these chemical signals.

Monreal is confident his research will be successful but says it takes time to get the product to the commercial stage. His first step was to identify the molecular composition of the chemical

signals produced by wheat and canola when they needed more nitrogen in the lab.

Then Maria Derosa, another researcher at Carleton University, was able to develop a biosensor that binds to the chemical signal being emitted by the plant roots. When this biosensor, which is a piece of Dna known as an aptamer, is housed in a polymer film around the urea, it distorts the film and enhances the exit of the urea thereby making its nitrogen available to the crop.

By 2012, Monreal had an early working prototype. working on an advanced prototype. “I am focusing on developing the polymer material that would be functional in soil,” he says. He hopes to soon be able to test the prototype in the greenhouse with wheat and canola crops.

This nanofertilizer is a win-win solution with no drawbacks, says Monreal. The nanofertilizer prevents nitrogen from being lost through leaching of water-soluble forms, emission of gaseous ammonia and nitrous oxide or by being tied up as mineral nitro gen in the soil organic matter by microbes. “and the biosensor and polymer are completely biodegradable,” he continues.

This is only one application of nanotechnology for fertil izers, says Monreal. There are three ways that nanofertilizers may deliver nutrients. The nutrient may be encapsulated in side nanomaterials or nanoporous materials, coated with a thin protective polymer film, or delivered as particles or emulsions of nanoscale dimensions. “o wing to the high surface area to volume ratio, the effectiveness of nanofertilizers may surpass the most innovative polymer-coated conventional (non-nano technology) fertilizers, which have seen little improvement in recent years,” Monreal says.

There are other applications for nanotechnology in agricul ture. nanotechnology will make it possible to more fully under stand the complex system of soil and roots at the molecular level, says Monreal. He is working on a project to identify which of the bacteria in the rhizosphere (the soil and water zone around the plant roots) are important for nitrogen mineralization during crop growth. He also hopes to be able to use advances in chemistry and molecular biology to get a better understanding of how soil organic matter stabilizes soil.

This research is funded by alberta Innovates Bio Solutions, a research agency funded by the government of alberta that helps industry solve challenges with solutions that deliver economic, environmental and social benefits.

Winter survival remains a serious barrier.

by Carolyn King

One of the key challenges for winter canola production is very basic: crop survival into the spring. So a project with multiple sites in e astern Canada has been evaluating the overwintering success of today’s winter canola cultivars, as well as testing several factors that might improve the crop’s survival and yield.

“I knew researchers had worked on winter canola in the past and found that it could work but didn’t work often enough. I wanted to see if there had been improvement enough in the genotypes that we might be looking at a better situation now,” says Don Smith, a professor in the plant science department at Mcgill University, who is leading the study.

The project started in 2013 and ran through two winters at five sites, for a total of 10 site years. all analyses and reporting are now nearly completed. The project is part of the canola and soybean research being conducted under the eastern Canada oilseeds Development alliance (eCoDa), jointly funded by agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) and industry. Smith is the scientific director of eCoDa’s research network, involving more than 20 research agencies across eastern Canada. His winter canola project was funded through aaFC’s growing Forward 1 and growing Forward 2 programs.

“a number of things came together in terms of increased interest in spring and winter canola in eastern Canada,” Smith says. “The cash value of some of the small grain cereals that producers grow sometimes has been pretty low, so they were looking for cash crops that might pay better and they were interested in canola. also, a few years ago a major oilseed crushing plant opened at Becancour, Que., providing easier access of oilseeds produced in Quebec and the Maritimes to crushing facilities; before that, the nearest crushing facilities were in southern ontario. also the St. Lawrence river at Becancour doesn’t freeze so you can bring in oilseeds by boat year-round, which is much less expensive. So that changed the economic landscape for oilseed production around here.”

eCoDa focuses mainly on spring canola, with only a small amount of research on winter canola. “Winter canola is always a higher risk, with Canadian winters being what they are,” Smith explains.

although winter canola is not as winter-hardy as crops like

Smith’s project showed that winter survival remains a challenge for today’s winter canola varieties.

winter wheat, it does have some potential benefits for growers. “When winter canola survives the winter, it can yield quite well. also, it provides ground cover through fall, winter and spring, protecting the soil from erosion,” Smith notes. “and winter canola starts to grow much earlier in the season [than spring-seeded canola].” earlier growth means earlier maturity, which can be an advantage, for example, if fall frosts come very early or if the summer turns hot. He says, “Canola is a temperate zone crop so when

temperatures get above about 25 C, the crop starts to get into problems caused by heat stress, such as floral abortion.”

one component of Smith’s winter canola project compared four varieties to see which ones performed best at each site. The five sites included one in ontario (ottawa), two in Quebec (west end of Montreal Island and south-east of Montreal), one in prince edward Island (Charlottetown) and one in nova Scotia (Truro). researchers in the eCoDa initiative managed the sites.

There were small differences in variety performance from site to site, but no variety was dramatically better than another. “We found that we don’t yet have the genotypes that can survive our winters very well. We had survival in about one year in three or four, which is just not enough,” Smith says.

“We only had good winter survival when there was enough snow cover. a good snow cover will insulate the plant against the more extreme weather conditions in the atmosphere. So you could have plunging air temperatures of -25 C or -30 C, and –although it depends [on the snow pack’s characteristics] – the temperature might only be a few degrees below 0 C at the soil surface under a thick covering of snow. Without a snow cover, it can be much colder for the plant and that can be a challenge.”

He adds, “Winter survival can be tough, but spring survival can also be difficult. With the transition from winter to spring, you get transitions back and forth across 0 C. So you get melting snow and pooling of water in low spots because the water can’t trickle down into the frozen soil, and then the puddles freeze into ice. That is very hard on the plants.”

The project’s sites included a range of conditions, so overwintering success varied from site to site and from year to year. The site at Mcgill’s agronomy research Centre near Montreal had some of the best winter survival. Smith explains, “at the Mcgill site, the winter canola plots were in a small field ringed by fairly tall trees so the snow catch was generally good. The message that comes out of this is that it’s about snow catch.”

ments for these two nutrients than many other commonly grown field crops. However, none of the fertilizer treatments produced clear differences in winter canola performance. another component of the project assessed the suitability of winter-seeded spring canola. Smith explains, “You can seed spring canola just before freeze-up in the fall or just before spring melt so the seeds don’t germinate immediately because the weather is too cold. When the snow melts in the spring, they’ll germinate right away. So the crop starts growing much earlier than spring-seeded canola.” So, like winter canola, winter-seeded spring canola would have potential advantages over spring-seeded canola due to earlier maturity.

“However, in our trials, very late seeded or very early seeded (onto frozen soil in both cases) spring canola had reasonable survival one year of the two when it was evaluated, which is not really good enough,” he says. Canola’s growing point is at or above the soil surface as the plant emerges, which makes it very vulnerable to early spring frost damage if the plant starts to grow

all of the five sites used conventional tillage systems. So a possible next step in this research would be to try no-till canola because the standing stubble from the previous crop has the potential to increase snow trapping.

The project’s results also confirmed that winter survival is affected by seeding date. Seeding has to be early enough for the plants to become sufficiently established before the first killing frost. The recommendation from ontario’s agriculture department is that winter canola plants should have about four to six leaves and a root system large enough to withstand some frost heaving and drying winds. If you seed too late, then the plant might be too small to make it through the winter. However, if you seed too early, the plant might bolt in the fall and would not survive the winter.

For the study sites in Smith’s project, seeding dates in the first 10 or 15 days of September were usually the best. He notes, “That can vary, of course, from year to year. In 2015, warm weather persisted and persisted, so in a year like that you might be able to plant into the first week of october and it would still be okay.”

The project also compared several fertilizer treatments, including different rates and timings for sulphur and different rates for boron. Smith explains that canola has higher require -

during a warm spell and then gets hit by a cold snap. Cereals like wheat and barley protect their growing points by keeping them below the soil surface during their early growth stages.

Smith also experimented with applying microbial compounds to winter canola to see whether these compounds would help the plants survive winter stresses. In previous research, Smith found that these compounds promote growth in several other crop species; in particular, the compounds can help plants withstand various stress conditions. But with winter canola, the benefits weren’t as strong. Smith says, “across years, when the plants were treated with these compounds, survival was numerically higher most of the time but not statistically higher most of the time.”

overall, Smith concludes, “We’ve learned that winter survival of winter canola is not there yet. But I think sooner or later breeders will develop winter canola varieties that have the right stuff and we’ll get there.”

For more on canola, visit www.topcropmanger.com

Those of us who work in agriculture – who live and love it every day – have the responsibility to make sure our industry is better understood. Because if we don’t, someone else will. And, we might not like what they have to say.

Social media offers many opportunities to tell ag’s story. Here are some ways you can start leveraging social media today.

Share and like

Find and follow people from different sectors or areas of the country who you think are helping tell the real, positive story of our industry. You can help spread their great work by hitting the share button or re-tweeting their content.

Find common ground

Think about what someone outside of ag might want to know – walk a mile in their shoes. Speak to issues that matter to them using terms and information that are accessible and responsible.

Use hashtags

Want to share your perspective on #GMO? Or curious about what people are saying about how we care for farm animals? Follow or search relevant hashtags. Look for conversations that you can contribute to. Share your perspective, photos and experiences. Speak from the heart and remember that it isn’t about picking a fight – it’s about sharing a conversation.

A picture (or video) is worth a thousand words

Share images or videos of your farm or your role in agriculture online to help others see “behind the barn doors.”

Keep calm, and agvocate on!

Online and off, it can be frustrating to hear misperceptions about the industry we love or to deal with people who misrepresent who we are and what we do. It’s important for us to stay calm, keep our cool and focus on answering questions, sharing our stories and experiences, as well as the facts and resources that can paint a more accurate picture of our industry.

Be it on a social media feed or the comment section of your favourite blog or site, the Internet has become the great equalizer, where anyone can share their point of view. And while most people are looking to engage in respectful conversation, even if they have differing points of view, there are people known as “trolls” who are only looking to disrupt and criticize. Bolstered by the relative anonymity of hiding behind a keyboard, these trolls’ main objective is to disrupt conversation with often hurtful and off-topic content. They can be a frustrating part of any online conversation, but it’s a little easier when you have a strategy to deal with them.

Don’t engage Trolls are looking for attention. They crave it. Don’t give it to them.

Stick to the facts

It’s not always clear that someone is a troll at first. If you suspect someone you’re engaging with is a troll, keep your comments to a minimum and stick to stating your case. Usually trolls will reveal themselves in their response, then you can simply move on.

Don’t take it personally

Trolls want a negative reaction and to do it, they will resort to some very hurtful tactics. Take it for what it is and don’t let it get to you.

Look to the moderator

When all else fails, most sites will have some sort of channel to report offensive comments or users.

Unfortunately trolls are a reality of having an open dialogue. But if you remain positive and patient, you can keep the trolls under the bridge where they belong.

Here are just a few:

Webinar: How to use social media to tell ag’s story

Social media guru Megan Madden will tell you everything you need to know to join the ag and food conversation online. She’ll help you decide which tools are best for you – and show you how you can get in on the ag and food conversations happening online today.

Webinar: How to get in on the tough ag and food conversations

Andrew Campbell talks about the importance of using social media to foster a positive perception of the industry – and shows some real-life success stories. He also covers how to deal with some of the not-so-positive dialogue out there. It’s not always easy, but it’s important – and everyone can do it.

Video: The power of social media in Canadian agriculture

Lyndon Carlson, a driving force behind Ag More Than Ever, recently sat down to chat about the power of social media in an agricultural context with our partners at the Canadian Association of Agri-Retailers (CAAR). In this podcast, Lyndon outlines how we as an industry can leverage the power of social media to tell our story.

by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

Every 15 minutes, 685 kilometres out in space, the national aeronautics and Space administration (naSa) satellite known as SM ap (Soil Moisture active passive) records the earth’s soil moisture and temperature. naSa then uses that data to produce the most accurate maps of global soil moisture, temperature and freeze-thaw states ever created with data from space. agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aa FC), environment Canada and university scientists are assisting naSa in validating SM ap soil maps. aa FC is also producing higher resolution soil moisture maps from the Canadian ra DarSaT-2 satellite.

The maps from SMap and raDarSaT-2 are valuable tools that help improve people’s understanding of the processes affecting weather and climate. This, in turn, can help agricultural production.

“Soil moisture is an important variable in the development of extreme events,” says Heather Mcnairn, the aaFC team lead and a research scientist for geomatics and remote sensing in ottawa. “If we don’t have enough water in the soil, drought can develop; if we have extended periods of wet soils, it puts us at risk of flooding.”

This is where the information from SMap and raDarSaT-2 comes in. It reveals how much moisture is in the soil so scientists – and producers – can understand the risks for drought or flooding.

“Knowing how much water is available in the soil can help us understand drought risk, where drought might be developing and how severe the drought might be,” Mcnairn says. “If we can measure how much water is in the soil, we can determine if the soils have enough reserve space to absorb spring snow melt and rainfall. If the soils are saturated, they are unable to accommodate additional water and this tells us the risk of flooding is high.”

From an agricultural perspective, monitoring soil moisture will enable the sector to better mitigate agricultural risks regionally and nationally. It will also help Canadian producers make informed decisions for their farm operations based on changing weather, water and climate conditions. For example, producers could use the data to determine their variable rate irrigation needs.

environment Canada will use data from SMap for improved weather forecasting since the amount of water in the soil significantly affects temperature and rainfall forecasts. “We don’t currently have good data on soil moisture across Canada,” Mcnairn says.

The data will also help researchers outside of Canada, such as in Chile where agronomists are looking at variable rate irrigation. “producers don’t know how to variably apply water because they don’t know where the moisture is in their fields,” Mcnairn says. She is assisting researchers in Chile to integrate soil moisture maps from SMap and raDarSaT-2 into their variable rate irrigation practices.

While naSa launched SMap in January 2015, aaFC began working with the space agency three years earlier. That’s when an aaFC team from ottawa and Winnipeg took part in SMapVeX12, a six-week field-testing campaign that involved government and university scientists collecting soil and plant measurements in southern Manitoba while naSa flew two aircraft equipped with the same sensors as the SMap satellite. The measurements from that mission were then used to calibrate and validate the processing models naSa was planning to use with SMap

During the SMap mission, which is expected to run at least three years, aaFC will provide naSa with data from its network of 12 soil monitoring stations in Manitoba and five in ontario, all installed at private farm sites. The SMap team will use this data to assess the accuracy of SMap’s soil moisture products.

The 2012 SMapVeX experiment used data from naSa aircraft to simulate what soil moisture maps from SMap would look like. now that SMap is launched, naSa is returning to Manitoba this year for a second experiment. SMapVeX16 will validate actual data from the satellite, and naSa will use what is learned during SMapVeX16 to improve its models and SMap’s global soil moisture maps.

Canada also collects data from its own satellite, raDarSaT-2, to produce soil moisture maps at resolutions higher than those produced by SMap. These methods will be carried forward and used with Canada’s next generation of satellites, the raDarSaT-Constellation scheduled to launch in 2018. With this Constellation, data for use in soil moisture mapping would be available from three satellites.

“SMap and raDarSaT-2 can work together to provide a range of soil moisture products,” Mcnairn says. The SMap sensor provides very coarse resolution images covering approximately 1,000 kilometres, which are very good for large scale forecasting of weather and floods, but not detailed enough for field scale mapping. This is where higher resolution data from raDarSaT-2 can help.

Scientists are validating the maps from SMap and also tackling how to downscale SMap data to improve the resolution of soil moisture maps from this naSa satellite. Downscaled SMap soil moisture products would provide producers with better data for use in variable rate irrigation and determining the disease risk at the field level. For example, “the risk of some crop diseases increases if the soil is wet for many days,” she explains. “The temporal persistence of wetness tells about risks and if we can determine this risk, this information will help producers make decisions in managing this risk.”

For now, it’s exciting that naSa is providing soil moisture maps for the whole world every three days, Mcnairn says. “We couldn’t do that without satellites.”

Fungicide application tips to ensure high-quality grain.

by Treena Hein

As farmers in o ntario well know, gibberella ear rot, or gib, is an important fungal disease in corn. The same organism, Fusarium graminearum , affects wheat as well, resulting in Fusarium head blight/scab.

T he pathogen overwinters in corn and wheat debris and the spores infect corn plants during silking. Indeed, humidity and rain during silking is a huge factor in infection rates, and also temperature (the fungus likes 28 C best). o ne thing farmers can do to control gibberella ear rot is avoid corn-corn or wheat-corn rotational patterns. But there are other things farmers should do, says a rt Schaafsma, who has been studying the diseases since he arrived at the University of guelph in 1987.

“a fter 1986, when there was a huge outbreak, we tried fungicides and we also noticed big differences in the hybrids,” recalls Schaafsma, a professor in the department of plant agriculture at the University of guelph’s r idgetown Campus.

“no hybrid has complete resistance and never will, but genetics are important. The turnover in hybrids was high then and it’s still high and we find this to some extent in wheat too. There’s a

push and pull between breeding for yield and breeding for resistance. There are certainly corn hybrids highly susceptible to gib that should not be grown.”

gibberella ear rot was back with a vengeance in o ntario in 2006, and Schaafsma says it was because the high-yielding hybrids planted at that time had little resistance to the pathogen.

“a good year for yield is a good year for gib, especially in o ntario,” he notes. “If you needed to locate a bullseye for the disease on a map of north a merica, it’s southwestern o ntario.

In 2006, the problem spilled over into Indiana and other states and the seed companies took notice. They re-examined genetics and weeded out families of hybrids with high susceptibility.”

The window of infection at silking is very narrow, with

AbOVE: Western bean cutworm is more prominent in Ontario, and in 2014, large amounts of Gibberella infection were seen through Western bean cutworm damage, as shown here.

individual ears susceptible for only about 24 hours. However, Schaafsma notes that with silking happening at different times in different plants in the stand, the total infection time can be a week – and the weather during that week obviously matters. The more days with heavy rain or thunderstorms at the silking stage, the worse the infection risk.

Silking aside, corn can also be infected through wounds in the ear from insect damage (or hail), and earlier damage is worse. european corn borer used to be a big factor in boosting gibberella incidence in o ntario, but Bt corn hybrids virtually wiped that pest out. However, Western bean cutworm has risen to prominence in its stead and 2014 saw large amounts of gibberella infection through damage from that pest.

“That year was a huge surprise in the amount of gib and resulting D on mycotoxin,” Schaafsma says. “Most of the infection was not from the pathogen moving down the silk, but through damaged ears.”

He notes that Syngenta Viptera hybrids have been effective in controlling Western bean cutworm but now resistance to the Herculex gene is becoming apparent. Insecticides are also important in its management, with Coragen and Matador 120e C providing good control with precisely timed foliar application.

Jocelyn Smith, a phD student in Schaafsma’s department, has been studying the roles of hybrids, insecticides and fungicides in gibberella control. “ r ate timing and testing different

products is important,” Schaafsma says. “Smith’s work will give us a wealth of information about that, and it’s also becoming apparent from her work how little damage from insects results in the toxin.”

a t this point, Schaafsma and his colleagues advise producers to use a tank mix of Coragen and fungicide. “With fungicide alone, we can only get a 15 per cent reduction in toxin. But with hybrids that have more resistance, combined with fungicide and insecticide, you can expect 70 to 80 per cent reduction of what you would have had through applying nothing.”

r esearch results show fungicides p roline and Caramba to be equally effective. Schaafsma also notes that strobilurin fungicides are to be avoided in both wheat and corn for gibberella control, even when mixed, as their application may result in more toxin than if you didn’t spray. Both p roline and Caramba also control corn leaf diseases such as rust, northern corn leaf blight, grey leaf spot and eyespot.

However, in Schaafsma’s view it’s critical that these fungicides are applied only just after tasseling time – if corn prices are low. “The best timing is when the silks first start to brown,” he explains. “gib is a weak pathogen and cannot colonize a healthy silk, and doesn’t do well on dead silk, but as the silk is dying, it can infect. So you want to spray on the silks just as they’re turning brown and exposed, two to three days after tassel. Better to apply a little earlier rather than later, so watch the weather.”

He notes that many farmers think the corn is too tall to spray after tasseling, but says, “I’ve done it with my own corn and it’s fine. It didn’t affect yield.” He adds that it’s easier to do it by air at that point, but more expensive, and spraying with a ground rig does a better job anyway.

In terms of overall gib control plans, Schaafsma advises picking a hybrid with highest yield potential but that also has some resistance to Fusarium, managing Western bean cutworm with insecticide and saving your fungicide for silking time.

Corn can also be infected through wounds in the ear from insect damage (or hail), and earlier damage is worse.

“In southwestern o ntario, you cannot afford to neglect D on, as you’ll get dinged when you sell your corn,” he concludes. “a lot of people worry about leaf diseases and forget about the D on. The ethanol plant is not a dumping ground for poor-quality grain and we learned that the hard way in 2006.”

growers may also want to do an earlier spray for leaf diseases, but that depends on the price of corn.

“The more money you get with your corn, the more you can spend to get the extra few bushels,” Schaafsma notes, “but you can only afford to spray fungicide once a year with low corn prices, and if you spray early, you’ll have a false sense of security.

“The rain during silking can happen, so reserve your fungicide for after tassel. You will still get a lot of leaf diseases but you’ll have less D on in your grain.”

Weeds can be a detriment to your soybean crop. Fortunately, DuPontTM CanopyTM PRO pre-emergence herbicide contains two modes-of-action to help manage herbicide resistance and control troublesome weeds. In addition, CanopyTM PRO delivers broad-spectrum residual activity on tough weeds like velvetleaf, dandelion and annual sow thistle. Even more good news for 2016. CanopyTM PRO is now registered for control of Canada fleabane including glyphosate resistant biotypes. Give your crops the protection they need with CanopyTM PRO.

Ask your retailer about Canopy™ PRO today. For more information call the DuPontTM FarmCare® Support Centre at 1-800-667-3925 or visit canopypro.dupont.ca