STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

T8 Multiple-herbicide-resistant waterhemp in Ontario

12 Winter wheat breeding in Quebec

14 Targeting tar spot in Ontario corn fields

16 Shedding light on Ontario cover crop practices

18 The side effects of wet/dry cycles

20 Planting corn and soybeans green into cover crops

22 Insect populations in 2021 and 2022 predictions

26 Results from the Prairie cover crop survey

here’s nothing like a global pandemic, extreme weather events or supply-chain issues to really shake how confident you are in doing your regular work. Had someone told you five years ago that you’d experience all three of those challenges – plus countless others – in a short time period, it might have scared you away from trying.

But here you are, in spite of it all, preparing for another year of not knowing what to expect. You’ve got all the tools in your toolbox to make good decisions, anticipate the challenges and approach them head on. Plus, a good attitude makes all the difference. Easy peasy, right? If only it were that simple.

Nevertheless, as we wrapped up another Top Crop Summit (our seventh event, and second one held virtually), our team reflected on the questions that were asked of the agenda’s presenters, and the comments and suggestions you, the audience, provided. One thing was clear –Canadian farmers are progressive and inquisitive; constantly looking for solutions and steps to battle any challenge they might face. It’s our job at Top Crop Manager to give you some of those answers, and it’s a job we take seriously every year through the various platforms through which we deliver content to you.

If you missed this year’s virtual event, you’re in luck. This special digital edition contains summaries from each presentation, with some important graphs and charts highlighted. At the end of each article, we’ve linked the presentation recordings so you can register and watch them.

We hope you enjoy catching up on this year’s informative presentations, and we look forward to hosting you again next year.

@TopCropMag

/topcropmanager

Stefanie Croley EASTERN

Alex Barnard

Bruce Barker

Quinton Moorehead

Michelle Allison

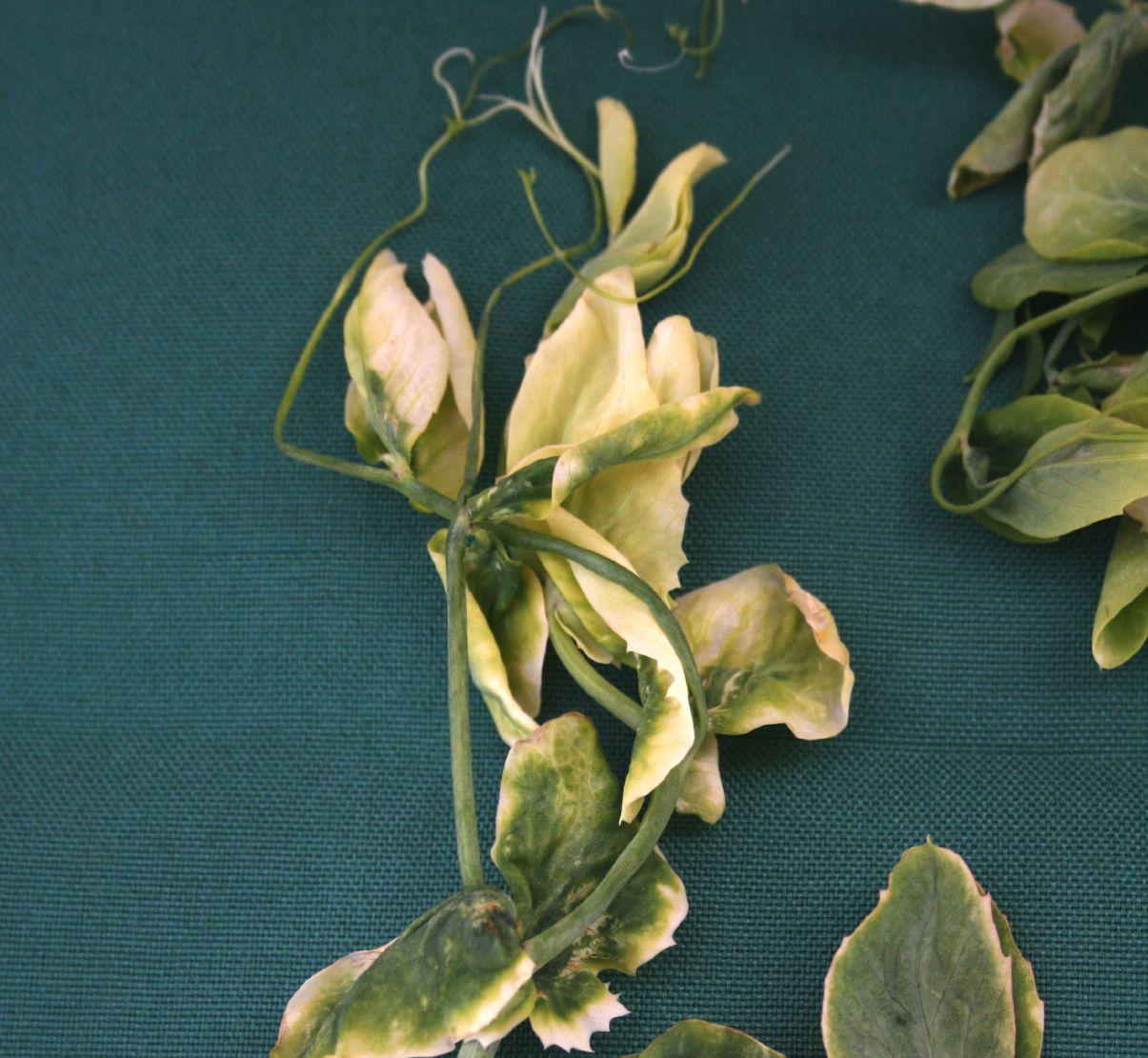

ON THE COVER:

Herbicide carryover can cause damage to crops, as shown in this pea plant.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CLARK BRENZIL.

Examining the potential for herbicide carryover in the

Presented by Clark Brenzil,

While there are several mechanisms that degrade herbicides in the soil, the two major ones are chemical hydrolysis and microbial activity.

With microbial activity in the soil, a variety of bacteria and fungi use herbicides as a food source, and as living organisms, they need moisture to survive. In a drought year, micro-organisms are not active since they require moist soil to survive. Most of these microbes are aerobic, so breakdown is slower in saturated soils where oxygen is limited. Group 3 herbicides can break down without oxygen, but that is the exception to the rule.

Chemical hydrolysis is where water cleaves the herbicide molecule in half to deactivate it. It requires moisture in the soil, as well.

If there is adequate moisture for breakdown – predictable breakdown under normal conditions – the other component is time. There has to be moisture for an adequate period of time at reasonable soil temperatures.

As a general rule, moisture is required between June 1 and Sept. 1, because this is the period during which there are warm soil temperatures for microbes to be active or for chemical hydrolysis to take place.

The rate of breakdown also depends on the herbicide. Some require six inches of moisture in that time period, while others require four inches of rainfall. If there are fewer than four inches, it is safe to say that all herbicides that normally carry over will be further affected by the lack of moisture. With rainfall amounts

greater than six inches, generally there is relatively predictable herbicide breakdown.

The risk of injury from a herbicide depends on the herbicide and the crop that might be affected. On page 89 of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture’s 2022 Guide to Crop Protection, there is a chart of herbicides and their carryover restrictions under normal conditions. These are the herbicides most at risk of carrying over and causing crop damage under low moisture conditions.

Some herbicides have multi-year recropping restrictions as well. If there were environmental conditions like the very dry conditions of 2021, add an extra year on to the recropping restrictions for every year with low rainfall.

For example, if a herbicide with a two-year recropping restriction was applied in 2019 with reasonable breakdown in 2019, but dry conditions occurred in 2020 and 2021, no breakdown may have occurred in those years. Essentially, what was a two-year breakdown window is now a four-year breakdown window.

Also, look at rainfall in that three month period. Rainfall in the shoulder seasons can be deceptive because temperature is very important for breakdown, as well. Rainfall that occurs in the fall, following a summer drought, may not allow for adequate breakdown.

As a general rule, if crops looked reasonably healthy in the previous growing season in the absence of a reserve of subsoil moisture, then there probably won’t be a lot of unexpected carryover going into the next year. But if crops were showing

symptoms of drought, that would be a good indicator that herbicide carryover may be a risk. There are also situations where there is good amount of subsoil moisture that keeps the crop doing well, yet there is insufficient surface moisture to promote breakdown. 2017 is a good example of that kind of year.

The top tip is to be really conservative with your crop choices for 2022. This is not the year to push the envelope for tolerance to herbicide carryover. This is the year to be very, very conservative for the crops being chosen, even within the recommended options. These crops may not be the most lucrative, but will be the ones that can provide a return.

Work with the manufacturer and your agronomist to figure out what to do in 2022. In some cases, that may include growing the same crop as last year. Normally there is the concern of disease buildup, but in areas with insufficient moisture for herbicide breakdown, the disease may not have been very high in 2021, so there may not be much inoculum to carry over to the subsequent crop. This is not ideal, but growing the same crop might help get out of the problem of what to do with herbicide carryover this coming year.

Producers also need to know not only the brand names of herbicides but also the active ingredients in the herbicides they are applying. If they didn’t get a letter in the mail warning of the risk of herbicide carryover from a manufacturer, producers are not necessarily safe. They may have used a generic version of a herbicide, and the generic company may not have the resources to support the product and contact producers.

For example, there are 410 herbicide brands in the Manitoba and Saskatchewan Guides to Crop Protection, but only 74 active ingredients. About 35 to 40 are the most commonly used, and about 20 are residual. If you know your active ingredients and know the risk, then it can be avoided going forward.

There aren’t any testing processes being provided by labs to be able to diagnose these issues, so that’s why producers need to be very conservative going into 2022.

Examining the magnitude, implications and opportunities.

Presented by Brian Beres, (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canad, Lethbridge, Alta.), Patricio Grassini, (University of Nebraska, Lincoln), Romulo Lollato (Kansas State University) and Aiden Sanden (University of Saskatchewan) at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23, 2022.

To introduce the concept of wheat yield gaps in Canada, Brian Beres explains that as wheat production on the Prairies evolved, it moved from when soils were first plowed to no-till systems that conserve soil health that allowed for increased crop diversity. Today, the complexity of the production system increases in the move to maximum yield. Maximum yield can be expressed by the equation of Genotype x Environment x Management.

A good example of these interactions comes from research in Australia. A low-input system provided a wheat yield of 1.6 tonnes per hectare. But when they added in a better rotation, summer weed control, no-till, early seeding and a new variety, the synergy of the system increased yield to 4.5 t/ha.

The challenge is to constantly weave in new technologies that will flourish in the field under unpredictable conditions of Prairie farmlands.

This challenge was the impetus for an international research partnership for wheat improvement, proposed by Hélène Lucas of France’s INRA in 2011 called the Wheat Initiative. The Wheat Initiative Strategic Research Agenda now has linkage in Canada at a national level with Cereals Canada teaming up with AAFC developing national research priorities, which are also now aligning with Grower Commission priorities at the provincial level.

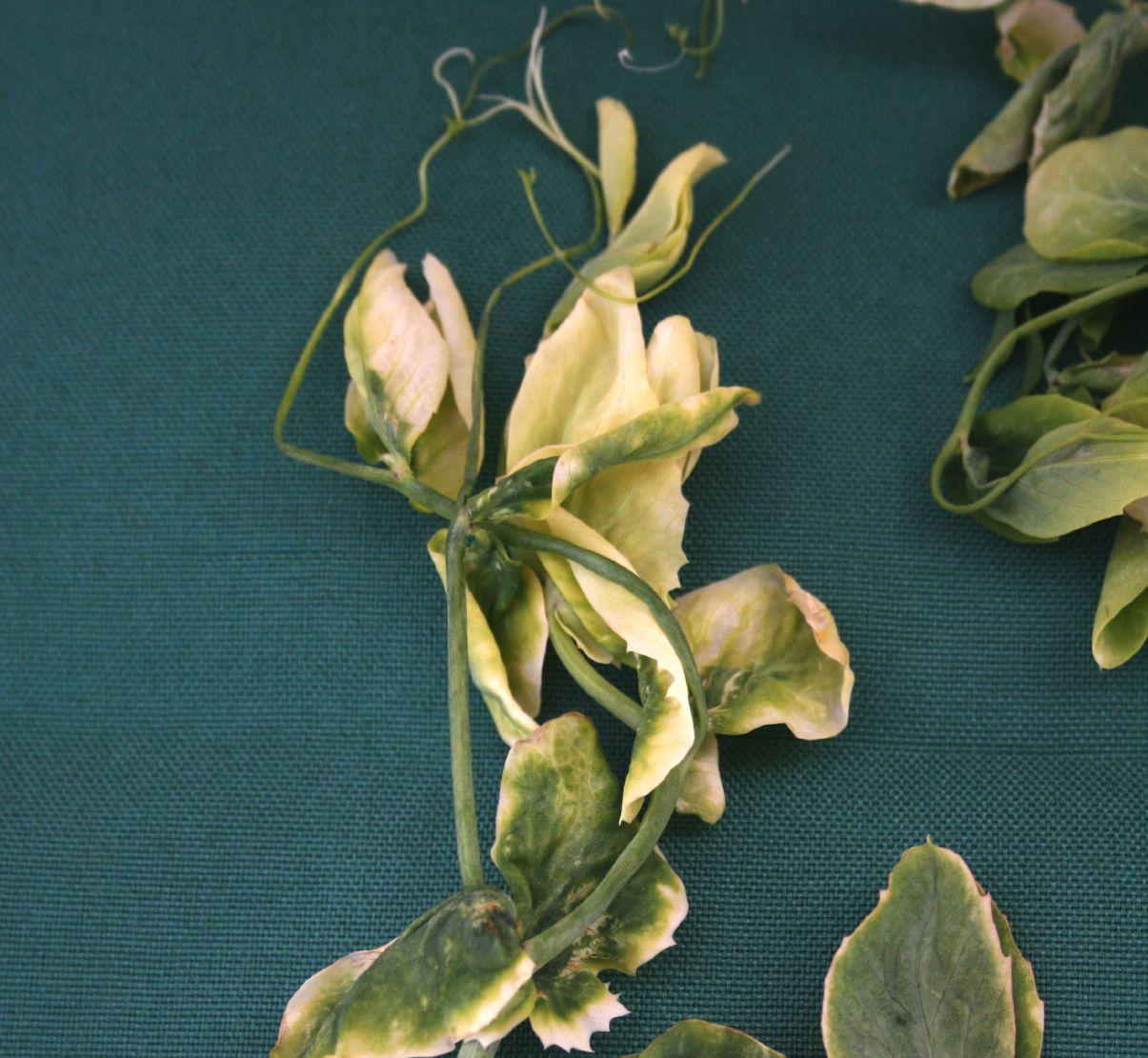

Patricio Grassini outlined the reasons for the Global Yield Gap Atlas project. He says that the increase in food demand (+50 per cent) over the next 30 years due to population increase and higher calorie intake, especially in developing countries, will challenge food production. Current crop yields are not sufficient to meet the extra food demand on existing cropland area. Massive cropland area expansion during the last 20 years (+13

million hectares per year) at the expense of forests, wetlands and other fragile ecosystems is a concern. On top of that, there is growing demand from society to know about the environmental impacts of food production systems.

Meeting the growing food demand must be achieved through sustainable systems so that every single hectare of existing cropland produces near its potential while minimizing environmental impact and preserving the resource base.

In the real world, attaining 80 per cent of yield potential is a reasonable target for farmers with access to inputs, markets and extension services. In the real world, there are hardly any cropping systems that can reach 80 per cent of yield potential. The difference between the 80 per cent potential and the average farm yield is called the “exploitable yield gap.”

About 12 years ago, the Global Yield Gap Atlas project was initiated by the University of Nebraska and the University of Wageningen (Netherlands). It uses a bottom-up approach to estimate yield

gaps, where the yield gaps are estimated regionally, nationally and globally. So far, it covers 70 countries and 90 per cent of rice, 84 per cent of maize, 56 per cent of wheat and 82 per cent of soybean crops grown in the world. The atlas can be accessed at www.yieldgap.org

The protocols used to estimate yield gaps are used globally. They take into consideration climate zones, crop-specific harvested areas, weather station data, soil types and cropping systems. This information is fed into crop model simulations to estimate yields, which are compared to average farm yields to estimate the yield gaps.

In places where social-economic conditions aren’t favourable for wheat production, like rainfed sub-Saharan, Africa and India, the yield gap is 70 to 80 per cent.

Beres says that developing a Yield Gap Atlas for wheat in Canada used those same protocols. An important component in getting started was the distribution of weather stations in wheat-producing areas. Government of Canada weather stations with at least 30 years of daily data, or a suitable alternative, were utilized. There is an art to the science of selecting the right weather station for the right wheatproducing areas to produce “buffer zones.” Twenty-seven buffers were selected that represented about 50 per cent of the national wheat area. The data confirmed that these buffers were unique production areas.

Buffer zones developed for the Canadian Wheat Yield Gap

Red areas (“buffer zones”) represent study areas, from which management information and weather data will be collected. Blue borders indicate that the buffer has irrigated production.

The model developed suggested that the average yield potential ranged from 52 to 89 bushels per acre in the different buffer areas. The yield gap varied quite a bit, and ranged from an average of 15 to 40 per cent on the Prairies. The average yield gap is 33 per cent on rainfed and about 32 for irrigated. These results shows Canada is doing well, but also shows that there is room for improvement. It gives the information to guide research, which may not be the same across the buffer zones.

In the U.S., Romulo Lollato says yields in the northern spring wheat areas are about 60 to 70 per cent of potential yield, and the yield gap is larger into the central and southern winter wheat regions.

The second stage of the U.S. Wheat Yield Gap Atlas project was trying to understand those yield gaps. A project in Kansas surveyed winter wheat growers on their management practices. Information was gathered from 700 fields across three years.

The average wheat yield was about 57 bu/ac but it ranged from five bu/ac to 106 bu/ac. The information provided the data to analyze how yields were influenced by management practices.

For example, in western Kansas, winter wheat yield peaked when planted on Sept. 28, and then lost 3.5 bushels per acre per day (bu/ac/day) for later planting. In south-central Kansas, a warmer region, the peak yield was sown Oct. 14. The yield loss

wasn’t as steep, losing 1.1 bu/ac/day up to the end of October, and then 2.7 bu/ac/day with later planting.

Foliar fungicide was also investigated. In wet seasons, a single application of a foliar fungicide yielded almost 10 bu/ac more, and in dry seasons, there was still a trend to 4.5 bu/ac higher yield.

At the University of Saskatchewan, Aiden Sanden is conducting research on understanding the yield gap with a focus on nitrogen fertilizer. The research question assumed that the goal is to maximize profits and not yield.

A model of wheat production was developed and determined the economically optimal rate for nitrogen. The research compared the average N use levels to the estimated optimal N level to establish if an exploitable yield gap exists.

Data from the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation provided one-quarter section-level yield, management and soil data from 2010 to 2019.

Three different models were run to estimate optimal versus actual N rates applied. The optimal rate was where the ratio of input price to output price was equivalent. Since the research was done, the price of wheat and N fertilizer has risen dramatically.

Model 1 found that the optimal N rate was estimated at 70 lbs/ac (79 kg/ha) while the average observed rate was 55 lbs/ac (62 kg/ha). Model 2 looked at previous crop interaction with N rate, and found that with cereals, the optimal N and observed N applied were very close. If oilseeds were previously grown, the average observed N rate was 18 lbs/ac (19 kg N/ha) less. For pulses, the difference was even greater with a difference of 43 lbs/ac (48 kg N/ha) less for the average N rate applied.

Saskatchewan

Model 3 took previous crop and soil groups into account. For the majority of soil groupings and previous crops, producers were underapplying N compared to the optimal rate. There is a significant gap following pulse crops. In the poorer soils in Groups 3 and 4, producers may be overapplying N.

Sanden’s research suggests that there is an Exploitable Yield Gap with N fertility in wheat.

Beres says that Sanden’s research is a good example of how research can investigate the Exploitable Yield Gap. Moving forward, Farming Smarter in Lethbridge, Alta., is leading the On-Farm Prairie CWRS Management Survey to help look at factors that may be contributing to wheat yield gaps on the Prairies.

Watch the entire presentation from the

Feb 23, 2022

Recent developments on this invasive species from Ontario.

Presented by Peter Sikkema, professor of field crop weed management, University of Guelph, at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 16, 2022.

Waterhemp is a summer annual weed. What sets it apart from most other weed species is that it is a dioecious species. It has separate male and female plants, usually in a 1:1 ratio. This means there is huge genetic variability, and the possibility of genes that confer resistance to various herbicide modes of action.

Waterhemp germinates and emerges throughout the growing season, and research in southwestern Ontario found that it could emerge from June 1 through to the end of October. This means waterhemp can emerge after the last herbicide burndown in no-till or the last cultivation in conventional tillage before planting.

When waterhemp flowers depending on when it emerges. Plants emerging in May take longer to flower, but plants that emerge in August and September begin to flower earlier. There are up to 10 flowering pulses during the growing season. This means there will be some flowering periods that are favourable for viable seed production.

Pollen is spread by wind and usually moves less than 25 metres (m), but can travel up to 800 m. Seeds reach maturity nine to 14 days after pollination. If a plant emerges Sept. 1, it takes three weeks to switch to reproductive growth, and by the end of September, there could be viable seed returning to the seedbank.

It is an amazing seed producer. One plant in a non-competitive environment could produce 4.8 million seeds per female plant. When it emerges at the same time as soybean, it can produce 300,000 seeds per plant. And if it emerges 50 days after soybean planting, it can still produce 3,000 seeds per plant.

Waterhemp has a short seed longevity in the soil, usually less than five years, but can remain viable up to 20 years. It thrives in warmer, moderate to moist environments, and nitrogen rich soils. It can grow up to 2.5 cm per day and over 3.5 m in height.

Based on studies conducted in Ontario, the average corn yield loss is 19 per cent, but can be as high as 99 per cent. The research is from 62 corn trials conducted in Ontario

In soybean, the average yield loss was 43 per cent, and as high as 93 per cent. The Ontario research is from 36 soybean trials conducted in Ontario.

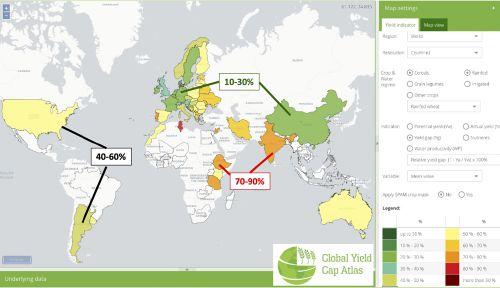

In 2014 in Lambton County, poor waterhemp control was observed, and glyphosate (Group 9) resistant waterhemp was confirmed.

Group 2 + 9 resistance has also been confirmed in Ontario. With the Group 2 resistance, one mechanism of resistance confers resistance to imidazolinones, but a second mechanism also confers resistance to sulfonylureas, imidazolinones, and triazolopyrimidines Group 2 herbicide families.

Group 2 + 5 + 9-resistant waterhemp has also been confirmed in Ontario. In one type of mechanism of resistance, the Group 5

resistant waterhemp was resistant to atrazine, but not metribuzin. But a second mechanism of resistance confers resistance to both atrazine and metribuzin (applied either as pre-emergent or postemergent).

Group 14 resistance has also been confirmed in Ontario. Soilapplied Group 14 herbicides were still effective, but post-emergent application were not effective on Group 14 resistant biotypes. Group 2 + 5 + 9 + 14 resistance has been confirmed.

In 2021, 15 counties had herbicide-resistant waterhemp. Eight of 15 counties had four way resistance to Groups 2 + 5 + 9 + 14, six had three-way resistance, and one had two-way resistance.

Herbicide-resistant waterhemp may be spreading through several mechanisms, including through contaminated combines moving between fields, on tillage equipment, during flooding events (because the seed can float), and by migratory birds.

The financial loss can be high. An average Ontario corn yield of 164 bushels/acre with an average price of $4.83 per bushel (2014 to 2019 averages), produces a gross return of $793 per acre. An average 19 per cent yield loss could result in a loss of $150/ac.

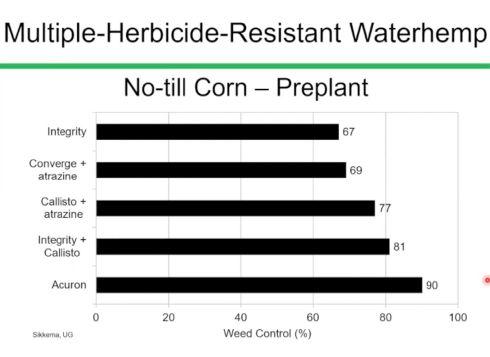

Sikkema’s research looked into controlling multiple-herbicideresistant waterhemp on no-till corn with pre-plant herbicides. Herbicides were applied when waterhemp was up to 10 cm tall, to control emerged waterhemp but also to give full season control. The most efficacious control was with Acuron, at 90 per cent control.

There was a difference in waterhemp control between Acuron Flexi and Acuron as well. Without atrazine in the Acuron Flexi formulation, control dropped to 76 per cent compared to 90 per cent with Acuron.

At pre-emerge timing in corn, four different herbicide/tank-mix combinations provided commercial control of waterhemp. Acuron provided 92 per control of multiple-herbicide-resistant waterhemp, Integrity at 91 per cent, Converge + Atrazine at 89 per cent, and Callisto + Atrazine at 86 per cent.

Sikkema had 36 experiments where Acuron was applied preemergent in corn. In 10 out of the 36 experiments (28 per cent), Acuron provided 100 per cent control. In another 50 per cent of experiments, Acuron provided between 90 and 99 per cent control. But eight per cent provided between 80 and 89 per cent control, six per cent between 70 and 79 per cent control, and in one experiment, it provided 50 per cent control.

This variability can be a result of several factors. Pre-emergent herbicides require rainfall for activation. Soil characteristics such as texture, pH, organic matter and CEC also influence control. Weed resistance profile and weed density also impact control. Late emerging weeds in August are also hard to control with preemergent herbicides.

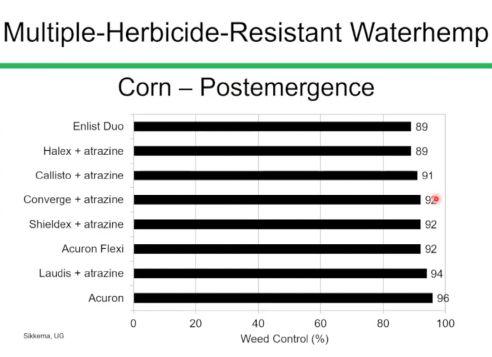

In corn post-emergent herbicide applications, several herbicides gave a high level of control.

In the eight post-emergent herbicides tested, seven have a Group 27 herbicide in them, with Enlist Duo (Group 4 + 9) the only one without. This means there is a heavy reliance on the Group 27 mode of action for waterhemp control.

In soybean, the average Ontario yield was 47 bu/ac with an average price of $12.12/bu to provide a gross return of $563 per acre. With an average yield loss of 43 per cent, the economic loss could be $242/ac.

In OMAFRA’s publication 75, there are 20 herbicides rated at 8 or 9 out of 9 for control of pigweeds and waterhemp. Eleven are soil applied and nine are post-emergent herbicides. In Sikkema’s research

on multiple-herbicide-resistant waterhemp, 19 out of 20 did not provide 80 per control. Only Valtera soil-applied provided 84 per cent control. This dramatically reduces herbicide options in soybean.

But some herbicides provided between 80 and 83 per cent control including Authority Supreme, Bifecta, TriActor and Valtera, while Fierce herbicide provided 90 per cent control.

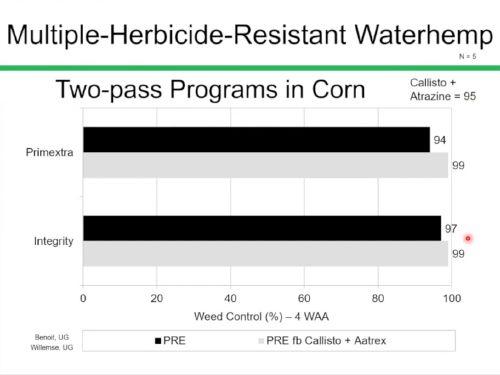

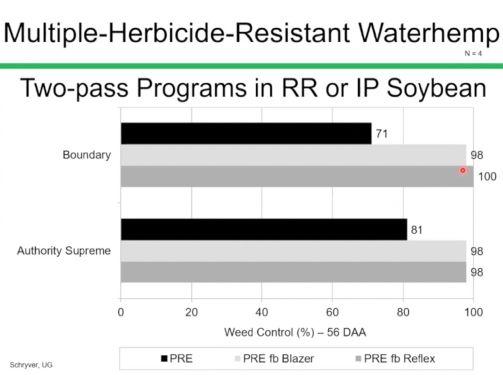

For control of multiple-resistant-waterhemp, Sikkema recommends that growers should be prepared to use a two-pass weed control program. Start with an effective soil-applied herbicide. In corn, the herbicides could be Acuron or Integrity. In soybean, it could be Fierce, Bifecta, TriActor, or Authority Supreme.

The soil-applied herbicide could be followed up with a postemergent herbicide, if needed. Scout the field regularly, because as already discussed, Acuron provided 100 per cent control of waterhemp in 28 per cent of experiments.

In corn, Sikkema’s research shows that post-emerge Acuron, Shieldex, Converge, Callisto, Enlist and dicamba were effective. In IP and Roundup Ready soybean, Reflex, Blazer and Hurricane herbicides were effective post-emergent herbicides. In Enlist soybean, Enlist Duo would be a good post-emergent herbicide. And in Xtend soybean, Engenia, Tavium and Extendimax are good choices.

An example of a two-pass herbicide program in corn would be Primextra or Integrity pre-emerge followed by Callisto + Atrazine post-emergent. This provided 99 per cent control.

A similar program in corn would be Converge or Acuron soil-applied followed up by Liberty post-emerge. This provided 97 to 99 per cent control. In Roundup Ready or IP soybean, a two-pass system of Boundary or Authority Supreme, followed by Reflex or Blazer, control was 98 to 100 per cent.

In Enlist soybean, a similar approach could be soil-applied Boundary, Authority Supreme or Fierce, and followed by postemergent Enlist Duo, which provided 99 per cent control. A two-pass program in Liberty Link soybean could use Authority Supreme, Boundary or Fierce, followed by Liberty post-emergent, control was 97 to 99 per cent.

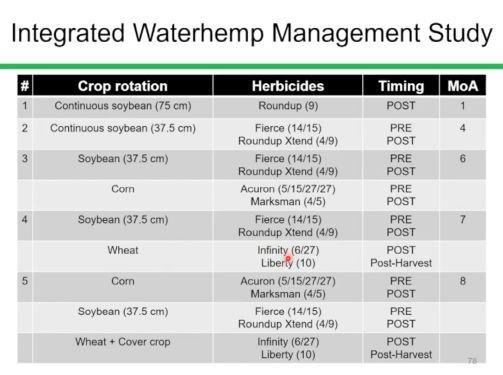

Herbicide stewardship will require cropping system diversity for resistance management. At the University of Illinois, Pat Tranel found that grower management practices was the number one factor that influenced the selection for glyphosate-resistant waterhemp on individual farms. For good herbicide stewardship, farmers should plan a long-term diverse crop rotation, use tillage at strategic points in the rotation, plant in narrow rows when possible, plant cover crops after winter wheat, consider harvest weed seed control, and use multiple herbicide modes-of-action. To demonstrate this type of diversity, Sikkema set up a nine-year integrated waterhemp management study on two commercial farms with corn, winter wheat and soybean in rotation. The goal was to deplete the waterhemp seedbank by 95 per cent using practices that could be implemented on Ontario farms. The study started in 2017 and will run until 2025.

When the study was initiated, the Cottam farm had 165 millions waterhemp seeds/ac, and at the Walpole Island farm, there were 16 million seeds/ac. Five crop rotations are included: continuous soybean, corn/soybean, soybean/wheat, corn/soybean/winter wheat, and corn/soybean/winter wheat + cover crop. Soybean row widths of 37.5 or 75 cm are compared. Up to eight herbicide modes of action are used.

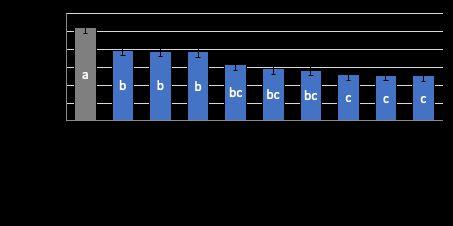

The results of the first three-year cycle at the Cottam farm found a larger decrease in the waterhemp seedbank as the cropping and

herbicide diversity increased. The largest decrease was with rotation #5 at an 82 per cent decrease, followed by rotation #4 at 79 per cent, and rotation #3 at 78 per cent. The number of seeds in the seedbank with the best rotation was reduced from 165 million seeds to 30 million seeds per acre.

To quote Andrew Kniss at the University of Wyoming: “At some point we need to stop looking to herbicides as the solution to a problem created by herbicides.”

Presented by Michel

McElroy,

CÉROM, as an on-demand session for the 2022 Top Crop Summit, Feb 16, 2022.

There are three main attributes that are looked at in CÉROM’s hard red winter wheat breeding program. The first one is yield – but that becomes complicated, especially with winter wheat in Quebec. One of the major limitations for winter wheat production in Quebec is overwinter survival.

Selection does focus on how much yield we can get per hectare, but we also have to focus on how well the wheat can survive, even in very adverse conditions. When it gets very cold, or when there are oscillating conditions from very warm to very cold, winter survival is very important.

The second big factor is disease resistance. The primary concern is Fusarium head blight, a devasting disease across Canada, but particularly Eastern Canada. It can reduce yield and also produce mycotoxins that can be toxic to both humans and livestock.

We have some very good germplasm that is resistant to Fusarium that we obtained from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. We are taking that material and trying to integrate better traits into it, so it can be Fusarium-resistant but also agronomically superior, as well.

We use molecular markers, and also test in a Fusarium nursery that is inoculated and irrigated. This way we can see how the varieties react under the worst of conditions.

Finally, we have to meet quality parameters. Hard red winter wheat is used to produce bread, so we have to produce the right quality, particularly with gluten.

There are a number of millers in Quebec that are interested in getting specific quality for their products, like baguettes and crusty breads, and other products that have been traditionally made with winter wheat. So we like to work closely with those millers to make sure we are developing the kind of varieties that they will use.

Millers’ interest is in the quality because that is their business. But they are very aware that the varieties we develop have to work for producers, for millers, and for the end consumers. We really try to include everyone we can in the whole value chain. There is a good co-operative spirit between all our collaborators to try to get the best varieties out for everyone.

We are constantly putting out new lines. There are a few coming up for possible registration. In terms of changes to the actual program, we have been trying to integrate new technologies to move the selection process along faster than traditional types of breeding. Everything in plant breeding is speed and efficiency: how much genetic gain can you get in every cycle, how fast can you advance varieties.

One of the ways to move that forward is through the use of genomics. This is an area we are trying to integrate into our program. We have taken set lines and tested them in different environments and for a number of different parameters, and then genotyped them. We have information for them across the entire genome, which we use to develop models that we can use to predict not only what the lines can do, but also theoretical lines that we haven’t tested yet. So if we cross lines that we haven’t tested yet, before we even put them in the field, we can genotype them again and see which ones have the greatest potential for new varieties.

It is an exciting time because the cost of genotyping is decreasing and the speed at which we can do it is increasing all the time. We can advance how fast we can go and respond more quickly to the needs of producers. It is important to have a program that is responsive and flexible, especially in these times when climate is changing and markets are changing so quickly.

It is good to have a combination of both, because nothing can replace testing in the field. But when you start with literally thousands of lines, you can’t test them all. Either you pick what you know based on the pedigree of the line and what you know about it, or take the genome and concentrate on those with the highest potential, and then go out and confirm in the field.

We do keep MRLs [maximum residue limits] in mind, which is important with climate change and the changes we have to make to our agricultural production systems to keep in line with lower carbon footprint. We want to provide producers with the best tools, which is breeding for disease resistance. It is the best way to prevent these kinds of problems in the field, and reduce the amount of inputs that have to be used.

For example, if you have a variety that is sensitive to Fusarium head blight, you have to compensate for that lack of disease resistance and spray, sometimes multiple times. If you have that strong genetic resistance, you can reduce the amount of interventions you have to do, and reduce the amount of inputs that have to be put on and the amount of time spent applying fungicides. And the fuel cost isn’t inconsequential, either.

In terms of fertilizer inputs, we try to test in conditions that most producers are using. We try to make sure the level of N is the same as producers are using. At the same time, we like to try to take some of the lines that we are testing and test them under low-input conditions. Whether that is for the organic market, or in a general sense to see how they will act. Because if there are certain genotypes that are showing up that do okay under conventional, but are also relatively stable under low inputs, that is important to know. But others might really need the N to perform well, as without N they fall flat.

By keeping these lines in the pipeline, we know we have that genetic variability should we need it. As trends change and if low input becomes a more important system in the market, we know that we have that type of genetics in the toolbox that we can use.

I would like to thank our major funders, the Quebec grain producers, SeCan, the Consortium de recherche et innovations en bioprocédés industriels au Québec (CRIBIQ), and the Quebec Ministry of Agriculture.

Watch the entire presentation from the Feb 16, 2022

ABOVE: Breeding projects at CÉROM are examining winter wheat quality, milling needs and genomics.

Insights on the disease from the U.S., and an eye on the developing issue in Ontario.

Presented by Albert Tenuta, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and Damon Smith, University of Wisconsin-Madison, at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 16, 2022.

Indiana and Illinois were the first States to report tar spot in 2016, and it was just recently found in Ontario. What should growers, consultants be looking for?

Tar spot is one of the easiest diseases to identify. The causal agent is Phyllachora maydis . The disease is identified by small, raised black lesions (stroma) on corn leaves. They can be round or irregular in shape. It has a sandpaper feel when the leaf is rubbed. It usually shows up in early July.

The other symptom can be a fisheye lesion (tan halo), although it is less common.

What has been seen in the Midwest U.S. is a bottom-up trend in the disease cycle. When tar spot first appeared in the U.S., the top leaves were the first leaves infected, indicating long distance wind spread of the pathogen. Now that the disease is established, the bottom leaves are infected from corn residue on the ground, and it spreads upwards on the corn plant. The disease is polycyclic, and can have several cycles per season.

A lot of the management strategies are to try to slow down the fungus enough to let the crop make grain. Eventually all the management strategies will succumb to the disease, and it is really a race to the finish.

The disease has become endemic in the Midwest in Indiana and Illinois since 2016, and is spreading to Wisconsin, Iowa and Michigan. As it has become more established, it wasn’t surprising to see it expand east/west and north/south. In 2020, it was seen in five southern Ontario counties at low levels. What was surprising in 2021 was that it expanded into

a larger area of Ontario than expected.

Moisture and extend periods of leaf wetness are very important for the tar spot pathogen. In Michigan there is a lot of irrigated corn, and tar spot has been a perennial problem. Leaf wetness really drives the disease, especially overnight wetness. Temperature is important, but short-lived high temperatures are not lethal.

Warm days, cool nights and high humidity, are important. When you can go out to a corn field at mid-morning and still get wet, that is tar spot weather.

The disease levels in southern Ontario in 2021 correlated to June to August precipitation, where rainfall amounts were quite high. Tenuta says that in Ontario, the disease developed rapidly at 17 C to 23 C, seven hours of leaf wetness at night, high relative humidity greater than 75 per cent, foggy days, and about six inches of monthly rain during the growing season.

Hot conditions in the U.S. in 2021 didn’t shut down the fungus. The pathogen survives on the leaf, and when it cools off at night, it starts to grow again. Pay attention to temperatures at night, and leaf wetness.

Early July is the time to be out scouting for tar spot. At the University of Wisconsin, Smith developed a scouting tool, called the Tarspotter app (https://ipcm.wisc.edu/apps/tarspotter/) to help with scouting. It takes leaf wetness, rainfall, and temperature parameters into account to predict disease development. It helps to predict when to get out and scout, and can be used to help schedule fungicide applications. It can also help to track the spread of the disease on a regional basis.

Tarspotter is also included in the Field Prophet app (https://www.fieldprophet.com/app/), along with Sporecaster and other apps. Field Prophet is a University of Wisconsin project, and includes a seven-day history and seven-day forecast, which Tarspotter and Sporecaster don’t have.

Smith’s experience is that tar spot can overwinter on corn residue. Seven field trials in 2020 and 2021 looked at low and high residue impact on disease severity to see if tillage could help manage the disease. There was a small reduction in severity in the following year with low residue, but not enough to suggest that tillage would help to control the disease. But there would also have to be widespread tillage to reduce airborne transfer to make it effective.

Data from hybrid trials in Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, and Indiana in 2018 provided information on the yield loss relationship with tar spot severity. On early maturing hybrids,

ABOVE: Black lesions typical of tar spot.

Disease resistance in corn hybrids is a key management strategy. Research in Ontario looked at screening of 64 different hybrids for resistance, and some had better resistance than others, but none were fully resistant. This was similar to results in the U.S. as well.

Seed companies are starting to put tar spot disease ratings in their seed catalogues. It has taken time to accumulate the research data to provide reliable ratings.

Plant breeders have found some sources of resistance germplasm in tropical corn hybrids, but it will take time to get these genetics into hybrids.

Integrated disease management will be key. Hybrid selection is one tool. Foliar fungicide is another tool.

In 2021 Ontario joined on-going research conducted out of the University of Wisconsin looking at fungicide evaluation for tar spot control. Common fungicides with one-, two- or threeway modes of action were compared. All fungicides gave some level of control. The 2021 trials were conducted in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ontario.

Uniform fungicide trial on tar spot – Disease severity 2021

cide application. Six locations in 2019 found that the best timing was VT to R2, and the optimum window may be VT to R3. Earlier applications, like V6 run out of protection. Save money on the earlier applications and target VT to R3 for tar spot and other disease at those timings.

Research from the U.S. also found that earlier application at V10 can help control the disease – not as well as VT, but if access to aerial applicators is a problem later in the season, an application at V10 with a ground sprayer can help reduced disease and preserve yield.

For silage, R1 application is performing well. Chopping a little earlier is advised, if the moisture content is ready. Tar spot dries down the crop quickly, so chopping before the disease progresses too far is recommended.

Another consideration for 2022 is to scout for lodging potential and harvest those at-risk fields first. Lodging was an issue in some fields in Ontario in 2021, so selection for a hybrid with better lodging resistance is important.

Heading into 2022, Smith is seeing corn growers changing their philosophy on hybrid selection. Previously, growers were targeting high yields, but those hybrids take a lot of inputs and take longer to mature, making them more susceptible to tar spot. Growers are rethinking, and looking at partially resistant hybrids with maybe lower yields that don’t take so many inputs, and might save a fungicide application.

A key resource for corn growers and agronomists: www.CropProtectionNetwork.org.

Results of the Ontario Cover Crop survey conducted by Callum Morrison and Yvonne Lawley.

Presented by Callum Morrison as an on-demand session for the 2022 Top Crop Summit, Feb. 16, 2022.

The Ontario Cover Crop Strategy was doing research on cover crops, and the Ontario Cover Crop Steering Committee, part of that group, wanted to do a similar survey as we had done in 2019 on cover crops on the Prairies. So we adapted our Prairie survey for an Ontario audience.

The Ontario Cover Crop Strategy is supported by many different Ontario farm organizations, and provided input into the survey, and also provided the opportunity to get the survey out to farmers. Facebook and Twitter were also used to build networks with farmers to get the survey out.

Dr. Yvonne Lawley and I designed, conducted and wrote the survey results. A smaller committee consisting of Anne Verhallen from OMAFRA, Marty Vermey with the Grain Farmers of Ontario, and Laura Van Eerd with the University of Guelph, provided advice on the project design to customize it to Ontario.

We heard from 731 farmers, from every county in Ontario. Of those, 520 grew a cover crop in 2020. Those 520 farmers grew 107,900 acres of cover crops.

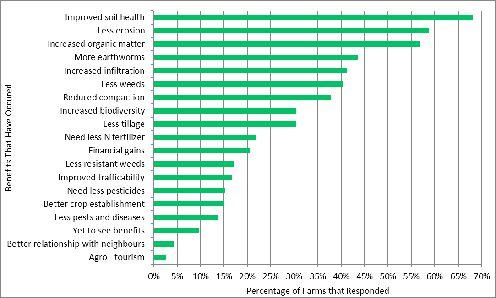

Ninety-one per cent of farmers who grew cover crops in 2020 saw at least one benefit from growing cover crops. The most common was that 68 per cent of farms saw an improvement in soil health. Another 59 per cent were seeing less erosion, and 57 per cent were seeing increased soil organic matter.

An important question to ask was, “How soon did they see those benefits?” Over three-quarters (77 per cent) of farmers said they saw benefits within the first three years. Some benefits can be seen immediately, such as erosion that is reduced when a cover crop is grown. Others, like building soil organic matter, take more time, but it was interesting to see how quickly farmers said they saw the benefits.

ABOVE: Benefits that have occurred from growing cover crops.

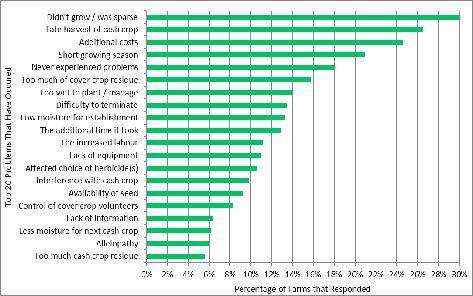

We wanted to identify challenges of growing cover crops so they could be targeted for research and extension in the future.

The most commonly observed issue was poor establishment at 30 per cent. The next most common was late harvest of a cash crop that prevented the planting of a cover crop at 27 per cent of respondents. The third most common challenge was the additional costs of growing a cover crop (25 per cent).

What was also important to hear the reasons why farmers didn’t grow cover crops. These farmers said that they would be incentivized to grow cover crops through financial compensation. Fifty-three per cent said they would grow cover crops if they were provided tax credits, were paid for storing carbon (43 per cent), or received payments from conservation or watershed

ABOVE: The Ontario Cover Crop survey shed light on cover cropping practices on Ontario farms.

groups (36 per cent).

There are other ways of encouraging cover cropping, such as through providing technical assistance, providing access to information on cover crop agronomy, more access to research specific to their local area, and even local farm tours and creation of a local network of famers growing cover crops. Some are more difficult to do, while others could happen more quickly.

It is really important to get that engagement with scientists and policy makers and researchers and farmers. This is why research is done, to help farmers, and by extension, everyone. We all eat food. We want soils to be healthy. We want our waters and rivers to be healthy.

We asked farmers if their old system, before they adopted

cover crops, worked better. Only one farm out of 520 farms who grew cover crops in 2020 agreed with that statement. This is a very strong indication that farmers believe that cover crops have a place on their farm in the long term.

Access the full survey report here: https://gfo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/OntarioReport-V12-Dec-1st-For-PDFconversion-for-publishing.pdf.

Presented

by Marla

Riekman,

soil management specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, at the Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23, 2022.

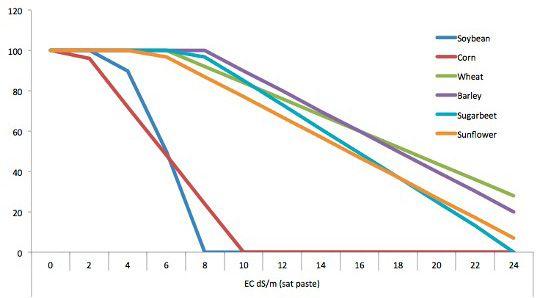

Salinity problems always follow wet dry cycles. It isn’t like salinity is here and then gone – it ebbs and flows. Salinity isn’t a salt problem. It is a water problem. If trying to manage salinity, water flow in the soil needs to be managed, and that is impacted by the level of the water table.

Several conditions are required to create a soil salinity problem. The first is a high water table that carries soluble salts into the root zone by capillary action. For this to occur, the water table needs to be less than six feet from the surface. Capillary rise can easily occur in clay soils, and less in sandy soils. The second is that evaporation exceeds infiltration for significant periods of time.

Pulses, vegetables and oilseeds are more susceptible to soil salinity. Crops like soybean and corn are very susceptible to salinity.

Salinity can occur in a variety of ways. Bathtub ring salinity is common in pothole country. Water in a slough moves downward in the soil, picking up salts that are moved upwards around the edges of the slough. This results in salinity in a circular pattern around the slough. Roadside salinity is similar where water in the ditch moves salts into the rooting zone along the headlands.

Electrical Conductivity (EC) is a measure of soluble salts in the soil. As the concentration of soluble salts increases, the EC of the soil extract increases. EC is expressed in dS/m, mS/cm, or mmho/cm, and these units are all equal.

There are several methods to diagnose the severity of soil salinity. Soil samples from zero- to six-inch and six- to 24-inch depths can be used for analysis. But there are two types of analysis used in the lab. Research and soil survey labs use the saturated paste method with a 1:2 soil:water ratio. Commercial soil test labs use a 1:1 soil:water ratio because it is faster and cheaper. As a result, to compare research results to commercial results, multiply the 1:1 commercial results by

two to get the same approximate EC values from research and soil survey results, or divide research results by two to get the equivalent commercial lab result. Soils can also be mapped using EM 38 or Veris Soil EC 3100. These are electromagnetic induction (EMI) devices that create a magnetic field to measure salinity. For both, calibration with soil tests is critical, as EC can change with clay and moisture content.

We deal with and manage salinity, but we can’t fix it. Use yield maps to determine where the poor growing saline areas are in a field – and then, stop wasting money on them. Invest in the saline spots by soil sampling to see how bad the salinity is, and look at putting some crop on them to manage the water. Plant a saline-tolerant crop that can lower the water table, or possibly use tile drainage. Keep the soil covered and reduce tillage to reduce evaporation that exceeds moisture infiltration.

Make strategic choices to manage water. Use high water use crops in non-saline areas, and use weeds to your advantage in saline areas. Plant a buffer crop to take up water along headlands or to intercept water around sloughs. For example, plant willows around sloughs to use water before it moves salts into the rooting zone, or plant alfalfa along the headlands to intercept water with roadside salinity. A longer-term solution can be the installation of tile drainage. This has potential but it is a slow process. Research in Manitoba found that it took about 10 years to reduce EC by one point.

Another approach may be to keep soils covered by placing mulch or manure or straw over the saline patches to decrease evaporation. But this may only be feasible on small areas and may not be the most effective solution. If you do nothing else, then do nothing at all. Resist the urge to till saline soils. Tillage encourages evaporation from the soil surface and brings more salts up via capillary rise.

For more severely saline soils, forages may be the only option. There are some very tolerant varieties, and AC Saltlander green wheatgrass is one of the better options showing good tolerance to highly saline soils.

The important thing to remember is that you should be skeptical of “quick fixes.” Ignore chemicals, commercial soil conditioners and other quick fixes. Remember, it’s not a salt problem but a water problem. The long term benefit of managing for salinity can pay off in the future, but patience is needed.

ABOVE: There are no quick fixes to salinity.

Whatever crop you grow or level of disease pressure you’re facing, Bayer has the right fungicide to help put you in control and ensure that each acre gets the exact protection it needs.

New Proline® GOLD fungicide delivers next-level, dual mode of action protection against sclerotinia.

New Prosaro® PRO is the first foliar fungicide in Canada to deliver ergot, fusarium head blight and leaf disease protection in wheat, barley, oats and triticale.

New TilMOR™ fungicide is your flex timing specialist that can be sprayed from flag leaf to heading in your wheat, barley and oats.

Ontario experiences and cover crop research.

Presented by Jake Munroe, soil management specialist with Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 16, 2022.

Cover crops bring several benefits to corn and soybean growers in Ontario. The first is that cover crops can be used as a weed management tool. An example is from a field where a rye cover crop wasn’t seeded in a small part of a field. Where the cover crop wasn’t established, Canada fleabane escapes were common, while the rest of the soybean field was clean.

Cover crops can also help protect fields from water erosion. They can also improve soil organic matter content, aggregate stability and water quality. Public perception can also be enhanced when cover crops are grown because they are seen as favourable to the environment.

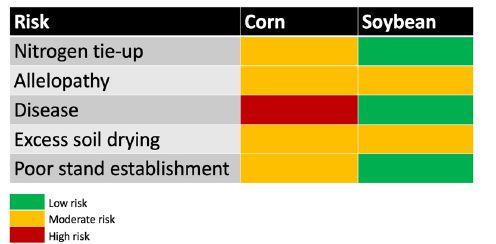

Cover crops also bring some risk to corn and soybean production. These include nitrogen tie-up, allelopathy, disease, excess soil drying and poor stand establishment.

Risk of planting green by crop (cereal rye)

Nitrogen tie-up due to immobilization of nitrate from a rye cover crop may result in lack of N fertility early in the growing season for corn. A solution to this immobilization could be to include a legume like hairy vetch in the overwintering cover crop mix. Another would be to include 30 pounds N per acre or more with the planter, and follow up with the balance of N later in the growing season. Seeding a thinner stand of rye could also reduce the risk, but some

of the benefit of weed suppression would be lost.

Allelopathy isn’t considered a major factor for large-seed plants like corn and soybean. Cereal rye, winter wheat and triticale are allelopathic, and these allelopathic chemicals can negatively impact the growth of other plants.

Disease is a concern for corn grown after cereal cover crops. This is the biggest risk factor. A cereal cover crop can act as a “green bridge” for disease to carry over from the fall into the spring for cereal crops. Disease is not a concern when moving from a cereal cover crop to a broadleaf crop like soybeans.

Research at Iowa State University looked at the impact of a rye cover crop on corn yield and radicle rot severity. Yield was significantly higher and disease severity lower when no cover crop was grown prior to corn. The timing of termination also impacted disease and yield. Termination at 18 days before planting, and progressing to 12 days after planting led to higher disease and lower yield when termination was delayed.

A potential solution to allelopathy and disease is growing the cover crop in wider spaces. Research at the University of Guelph by Olivia Noorenberghe (advisor: François Tardif) compared a rye cover crop on 7.5-inch row spacing to strip planting with alternating two rows on 7.5 inches with a 22.5-inch space between the paired rows. This strip planting left space for the corn to be planted between the cereal rye cover crop. At all rye termination timings from two weeks before to one week after planting, the yield loss from having a cover crop was cut by one-half or more with strip planting. For example, when the rye cover crop was terminated one week before planting, corn grown on the narrow row cover crop yielded 19 bushels per acre less than the no cover crop treatment, but the strip planting yield was 11 bu/ac less than the no cover crop treatment.

Research at the University of Guelph led by Drs. Josh Nasielski and Laura Van Eerd with graduate student Farzana Yasmin is looking at bio-strips to minimize allelopathy and disease issues. This involves planting a winterkill species like oilseed radish in the

ABOVE: Strip-till with no cover crop (right) on June 17, 2021, compared to a corn field planted into a rye cover crop.

seedrow, with rye or rye/vetch between the rows. Bio-strips help with weed suppression as well. In one trial at Ridgetown in 2021, the no-till corn without cover crop yielded 197 bu/ac, while the bio-strip-till yielded 175 bu/ac, a strip-till treatment with solid seeded rye cover crop yielded 173 bu/ac, and corn seeded into a solid seeded rye cover crop with no-till yielded 163 bu/ac. Cover crop termination was sprayed out around planting.

This trend was evident at other sites, but there still needs to be some tweaks to the system to try to get the cover crop yields higher.

Cover crops can keep the soil cooler and wetter in the spring, but rapid cover crop growth, especially rye, in May can dry the soil profile out quickly. An on-farm trial in 2021 highlight that risk with a side-by-side comparison of a cover crop to no cover crop. Heavy cover crop growth by mid-May resulted in excess soil drying. In the heavy clay soil, the seedbed was dry in the cover crop, resulting in poor seedrow closure and poor germination. The fall-sprayed cover crop strips had good crop emergence compared to the plant-green cover crop strips. At the end of the year, there was about a 20 bushel yield loss with the cover crop.

This example highlights the risk, but the field was also on a challenging heavy clay soil. A more loamy soil might be more forgiving. Timely termination is important if conditions turn dry.

The last risk in stand establishment is a cover crop acting as a ‘green bridge’ for insect pests, especially in corn. If cover crops are left growing until planting, insects can move from the cover crop to the emerging corn crop to continue feeding. This would include black cutworm and armyworm. Corn is more sensitive to stand losses. Soybeans aren’t invincible, but there haven’t been significant issues with stand loss due to insects.

Best practices for stand establishment when planting into

cover crops include using a seeder with sharp openers, adequate down pressure, and with the ability to close the slot. Don’t skimp on seed, and use at least 160,000 seeds per acre for soybean depending on your fields and location in Ontario. Also, leave the crop row clear of residue and scout for insect pests.

For soybean, research has found little yield difference in termination timing compared to a no-rye cover crop control. Planting green into a cover crop with termination after planting yielded similar to early termination before planting and the nocover crop control. Planting green is achievable in soybeans, and fairly low risk practice, especially if the rye stand isn’t too thick or termination isn’t delayed too long after planting.

Successful growers have found some keys to success for planting corn and soybeans into green cover crops. The first is to have patience. Green cover crops keep the soil cooler and may delay seeding. In terms of cover crop species and stand thickness, less is more. When planting, ensure adequate seeding depth for good seed-to-soil contact.

Plant either brown or green. Avoid planting into dying cover crops, as this can cause issues with the planter. Be flexible; every year is different.

In summary, planting green provides benefits and risk. It is easier with soybeans than corn. Know your risk tolerance, and why you want to plant green. Learn from an experienced grower, and start with winter-killed cover crops and early spring termination.

Recapping some of the most problematic insect pests in 2021, and looking ahead to the coming season.

Presented by James Tansey, provincial specialist insect/pest management, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23, 2022.

The first insect to talk about is grasshoppers. There was heavy localized pressure across the Prairies with many accounts of spraying and shortage of some control products. There are different species with different host preferences, and their presence in the crop may not necessarily mean trouble, and understanding the differences is important.

The Migratory grasshopper prefers forbs, grasses, wheat, barley and other crops, but during outbreaks, will eat almost anything, including the bark of small trees. In outbreaks, at high densities they have ‘gregarious’ behavior, similar to locust behavior, and migrate in large groups. The nymphs are capable of moving up to 16 kilometers per day, and 1000 km swarms have been reported from South Dakota to Saskatchewan.

The next one is Packard’s grasshopper. Less of an issue in 2021, but can outbreak and cause local damage. They prefer open habitat, and prefer legumes, but will also feed on vegetables and small grains.

The Two-Striped grasshopper was prevalent in most of Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and into Alberta as well. It prefers lush foliage and heavier textured soils, and will feed on weed species in sloughs and ditches. It is a pest of alfalfa, but will also feed on other crops including cereals.

The Clear-winged grasshopper is primarily a grass feeder. In 2021, there were very heavy populations in southeast Saskatchewan on pasture. There was a neighbouring lentil field across from the field with no damage, but a neighbouring wheat field was being converted to sticks. There was similar experience in Manitoba where there was no damage to canola across from a heavily infested pasture. So these grasshoppers are more host-specific.

In most crops, the threshold for large nymphs and adult grasshoppers is 10 to 12 per square metre. Lentil and flax in boll are more sensitive and the threshold is two/m2

The 2021 Grasshopper survey for Prairies provides some predictive power for 2022. There were some large populations, in some areas, but infestations could have been a lot worse.

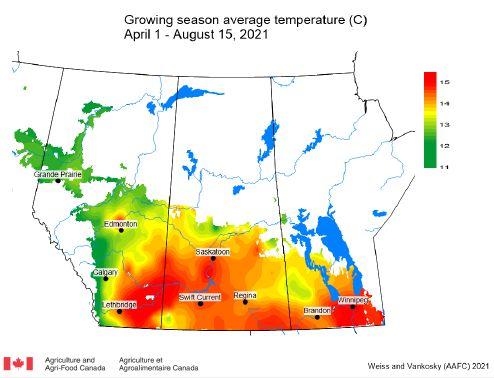

Spring temperature is also important for grasshopper development. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada monitors the accumulation of temperature, and the longer the grasshoppers have to develop, the more time they have to lay eggs for next year’s population. The maps are posted on the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network website at www.PrairiePest.ca. By Aug. 15, 2021, the maps showed that there was a lot of heat accumulation that would allow grasshopper development and egg laying.

Some grasshopper species like hot temperatures. Clearwing has maximum egg production at 32 to 37 C, and adults appear earlier than other species. Migratory grasshoppers have an upper temperature threshold for feeding around 45 C. The two-striped

grasshopper will bask in the sun to maintain a body temperature between 32 C and 38 C throughout the day.

For 2022, the potential for outbreak is dependent on the infestations from 2021. Conditions in 2021 were favourable for egg laying. In the spring of 2022, an earlier hatch with warmer, dryer conditions will allow more rapid development of grasshoppers. There needs to be some spring moisture to green-up foliage so juveniles have something to feed on early in the season.

The presence of natural enemies like blister beetles and field crickets can also impact grasshopper development. Many sites that had high grasshopper populations also had high populations of natural enemies.

There are also non-pest grasshoppers. There are 85 species of grasshoppers on the Prairies, and four to five are typically pests. If a grasshopper has wings before late June, it is not one of these species. An example seen throughout southern Saskatchewan in 2021 is the Speckle-winged rangeland grasshopper. Another conspicuous grasshopper that is active in late summer as adults but rarely causes issues is the Carolina grasshopper.

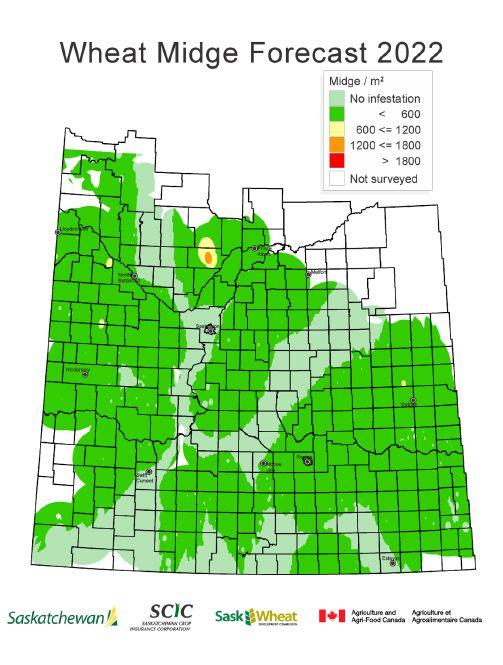

Wheat midge populations were relatively low across the Prairies in 2021, very likely because of low rainfall. The 2022 forecast for Saskatchewan shows a big decrease from 2021. They overwinter as larvae, typically in the soil. They need more than 25 mm of rain prior to the end of May to complete development to adults.

Insecticide products registered for control are Group 1B active ingredients dimethoate(Lagon/Cygon) and chlorpyrifos (Lorsban). Use of chlorypyrifos products will no longer be allowed at the end

of 2023. Varietal blends of wheat are a very good way to control the wheat midge.

Macroglenes penetrans is an important parasitoid and can have an impact on populations as well.

Scouting occurs at sunset when the wheat is between heading and flowering. Inspect daily from the time heads become visible as the boot splits until mid-flowering. Yield threshold is one midge per four to five heads. Grade threshold is one midge per eight to 10 heads.

There were several reports of barley thrips in barley and occasionally durum in late June and early July in the south and east part of Saskatchewan in the Regina, Weyburn and Tisdale regions. Some required control with dimethoate insecticide. The threshold for barley is seven to eight per stem, and scouting should happen relatively early as the stem elongates. Economic effects can occur in other grass crops but are less consistent.

These were monitored across the Prairies with pheromone traps. Isolated spraying occurred in central regions of Alberta and the outbreak in the Peace appears to be in decline. In Saskatchewan, there were very low levels and no reports of spraying. In Manitoba, there were no reports of spraying.

Bertha armyworm have cyclical outbreaks of approximately six to eight years, with population reductions primarily driven by baculoviruses and entomopathogenic fungi pathogens. There was a minor outbreak in 2015-2016, so there could be an outbreak, at least regionally, coming soon.

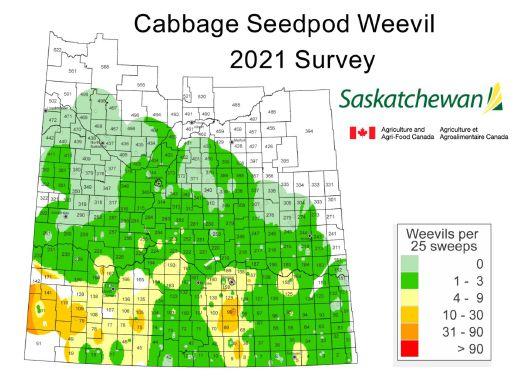

This insect is invasive, and has found its way across the Prairies. The cabbage seedpod weevil range continues to expand north and east from Alberta, and is now found in Manitoba in very low numbers.

Diamondback moth is monitored with pheromone bait lures. Low numbers were captured in Alberta and Saskatchewan with no reports of spraying. In Manitoba, numbers were relatively low, but some insecticide applications in the Eastern, Central and Interlake regions occurred.

They move up from southern latitudes, and once diamondback moth arrive, temperature is very important for development. It is possible for five generations to develop, but four generations is more typical.

Cutworms caused relatively widespread problems throughout the Prairies. Redbacked cutworms were found in central Alberta, and the Pale Western cutworm in the MD of Smoky River, with some reports of serious damage in canola late May to mid-June in central Alberta.

Sporadic reports of redbacked cutworms in central regions of Saskatchewan occurred in canola, with some reports of damage to faba bean and lentil.

In Manitoba, insecticide application and some reseeding were reported in canola in the northwest. Some cutworm damage was also reported in oats in the southwest.

Pale western and redbacked like dry conditions. Uncultivated fields with broadleaf weeds in August and September can attract egg-laying females.

Flea beetle were a large issue on the Prairies in 2021. Striped flea beetles are dominant in northern regions and populations are apparently moving south. Crucifer flea beetles are still predominant in the south but there is an apparent shift in prevalence of these species occurring. Regional prevalence and some of the factors that contribute to this is being researched in Western Canada.

Flea beetles were a major concern in canola throughout Alberta, and some control measures were used at late pod stage in the Peace. In Saskatchewan, there was widespread, serious damage in the northeast, and a lot of spraying and reseeding in 2021. Fall populations of the crucifer flea beetle were high in Swift Current, Regina and Outlook areas. Manitoba had several reports of multiple foliar insecticide applications for flea beetles. Ten to 15 per cent of canola acres in eastern Manitoba were reseeded.

Lygus bug was another big problem in a number of crops across the Prairies. In Alberta, it was a major pest in canola. In Saskatchewan, there were some reports of spraying, and they were a problem, primarily in flax in Saskatchewan, and some in canola. There were some reports of spraying in the northwest and eastern regions of Manitoba.

Lygus is a complex of several species, with over 300 host plants, including canola and faba beans. They are piercing, sucking feeders.

Adults emerge from plant litter after snow melt. After mating, females seek budding alfalfa or canola. The first nymphs appear the end of May. Lygus bug likes hot temperatures, with greatest egg production above 30 C. High relative humidity favours their development, but rainfall can be hard on the young nymphs and wash them off the plants. Parasitoids in the genusPeristenus are natural enemies.

The current nominal threshold in canola is two to three lygus bugs per sweep at late flower to early pod stages.

In faba bean, flowering to mid-pod stage is the most vulnerable. Lygus bug feeding can cause discolouration of the seed coat, hull perforations or seed pitting. No threshold has been established but the suggested recommendation is no action required at two per sweep. The best time to control is likely at early pod.

Canola flower midge has been found in Alberta and Saskatchewan within canola pods. There was no survey in 2021 because of Covid restrictions, but some fields were scouted in northeast Saskatchewan during the cabbage seedpod weevil survey, and populations were found to be low as in the past. It was noted in northwest Manitoba as well.

In Saskatchewan, the “red bug” – P

official common name yet) – has been reported. It is a piercing, sucking feeder, and the name of the family is the dirt-coloured seed bugs. They are very active and juveniles feed on seedlings of several crops. Adults can feed on canola (and other crop) seed underground and there is some evidence for a preference of adults for lentil seed.

Some damage was seen, particularly in flax, where there were literally large bare patches in the field. Sometimes their damage is mistaken for cutworm issues.

Surveys are conducted across most of Saskatchewan. The range continues to expand, and is now in low numbers Manitoba. Numbers were low in 2021, but an increase in the northeast of Saskatchewan was seen. Foliar insecticides are not recommended as results have been mixed in past tests.

Pea aphid is a pest in pea, faba bean and lentil. There were relatively low populations across the Prairies in 2021 with few reports of spraying. Populations blow up from the United States.

Scout peas when 50 to 75 per cent of the plants are in flower. The threshold is when there are two to three aphids per eight-inch plant tip, or nine to 12 aphids per sweep, at flowering. Apply an insecticide when 50 per cent of plants have some young pods.

The threshold for lentils is 30 to 40 pea aphids per sweep. In faba bean, economic thresholds look like 103 to 164 aphids per main branch.

Pea aphid does not like hot weather. Research shows that at 27 C, there is nine per cent survival of juveniles.

Watch the entire presentation from the

Feb 23, 2022

Exploring cover cropping trends on the Canadian Prairies.

Presented by Yvonne Lawley, assistant professor of agronomy and cropping systems, University of Manitoba, and Callum Morrison, graduate student, University of Manitoba, at the Western Top Crop Summit, Feb. 23, 2022.

To start the voluntary survey, social media was the initial method to contact farmers, and in the end, a good part of the survey came from farmers through social media contacts like Facebook. We also connected to agricultural organizations across the Prairies, and were in more than 80 media publications promoting the survey.

We heard from 281 farmers who grew cover crops in 2020, and from 247 farmers who didn’t grow cover crops.

One of the things that had to be decided at the start was how to define what cover crops are. There is a lot of innovation with forages, intercropping, and integrated crop and livestock systems. For the purposes of the survey, we defined it as any non-cash crops that were grown, and did include cover crops that were going to be grazed, green manures, and full season annual forages.

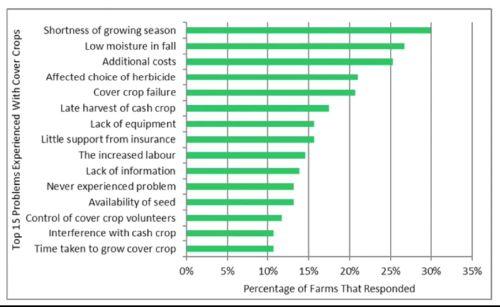

The shortness of the growing season is one of the driving factors in how farmers are doing things differently here. Another part of the challenge on the Prairies for cover crops is the environment, with periods of dryness in the fall making establishment difficult.

The survey results show the diversity of approaches from the early adopters of cover cropping, and some clear trends. The number of farmers responding was roughly one-third in each Province. Farmers were growing cover crops throughout most of the Prairies from Grande Prairie to the Red River Valley. This is an important message for agronomists and farmers to hear – that cover crops are grown in many different areas.

In the survey, of the 281 farmers that grew cover crops, 81 per cent grew a full season cover crop and 47 per cent grew a shoulder season cover crop. This covered 102,500 acres, with 55 per cent of the acres in shoulder season cover crops and 45 per cent were full season cover crops.

The percentage of farmers in each Province growing a full season

cover crop was similar, but Manitoba farmers grew a higher percentage of shoulder season cover crops. This was probably due to better moisture and a longer growing season in Manitoba.

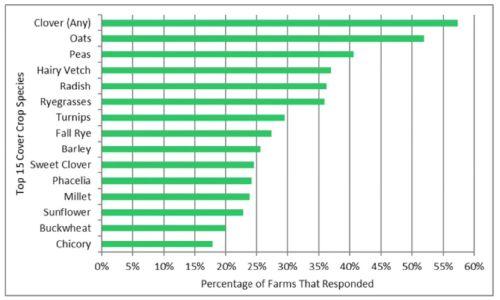

The most common cover crops grown were clover, grown by 57 per cent of respondents, and oats (52 per cent). Other popular cover crop species were peas (41 per cent), hairy vetch (37 per cent), and radish (36 per cent). Most were cold season cover crops. The cover crops grown were diverse with annual grasses, legumes and brassicas. These crops are very familiar, and for farmers getting started, they can look to crops they are familiar with.

Top 15 cover crop species grown by farms that responded

ABOVE: A cover crop of oats, canaryseed and flax in Rosenfeld, Man. Improved soil health was seen as the most frequent benefit by 54 per cent of farmers.

Smart Nutrition™ MAP+MST® granular fertilizer supplies your soil with all the sulfur and phosphate it needs, when your crop needs it. Using patented Micronized Sulfur Technology (MST), sulfur oxidizes faster allowing for earlier crop uptake — making the nutrients available to your crops when it’s needed most.

Learn how Smart Nutrition MAP+MST can boost your soil’s performance and maximize your ROI at SmartNutritionMST.com

In terms of diversity, some are growing 10 or more species, but the majority are growing two or three species. If getting started, try two or three species because that helps to spread the risk of getting something established. There are also seed costs to consider when growing cover crops.

Over a number of years, most farmers increased the number of species grown in a cover crop, with less than five per cent decreasing the number of species. Forty-five per cent of farms increased the number of species of cover crops over time, and 27 per cent did not change the number of species of cover crops.

One of the interesting findings was the importance of intercropping for Prairies farmers growing cover crops. A large proportion of farms are establishing their cover crops as an intercrop either at the same time as their cash crop (37 per cent) or by broadcasting their cover crop into their cash crop at some point during the growing season before harvest (14 per cent). It appears that some farmers are using intercropping as a way to get around the short growing season or dryness after harvest.

For termination, farmers are using species that will winter kill (37 per cent). Grazing to terminate cover crops (46 per cent) was also popular. As farmers get more experience, there may more overwintering cover crops that require termination with tillage or herbicides.

Ninety-one per cent of farmers said they saw at least one benefit from cover crops. The most common was improved soil health. They also said they saw increased biodiversity and organic matter, and less erosion. Some of these benefits increase over time, and others might be seen relatively quickly.

One surprising finding was how quickly farmers said they saw a benefit to cover crops. Over 35 per cent saw benefits from growing cover crops within one year. Roughly three-quarters of farmers saw benefits within the first three years of growing cover crops. The benefits they valued also probably change over time.

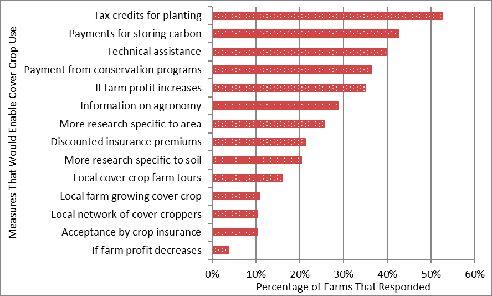

Along with these benefits are real challenges. It is important for farmers to know those challenges, and also for policy makers to understand those as well. The most common challenge was the shortness of the growing season, experienced by 30 per cent of farmers.

Low moisture in the fall was also a challenge for 27 per cent of farmers. The additional costs of growing cover crops (25 per cent) and the impact of cover crop on herbicide choice (21 per cent) were also common problems identified by respondents. It appears these challenges are not insurmountable, and by identifying them, farmers can proactively innovate their way out of those challenges. But it also allows researchers and extension the opportunity to see where research needs to be targeted.

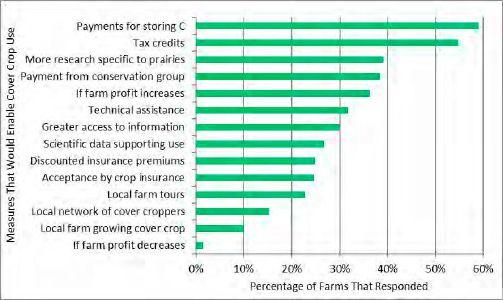

Cover crops are at a very early stage of adoption, and there are a few things that would encourage it. The survey found that top two practices to encourage farmers to grow cover crops were payments for storing carbon (59 per cent) and tax credits for planting cover crops (55 per cent). The implementation of these practices will be complex, but that is where farmers are looking to help cover some of the additional costs of cover crops.

Other things that can be down to encourage the adoption is investing in research in local regions. Having information that is local would really help farmers. Also, providing technical assistance, access to information and extension, and economic and scientific data to support adoption were also measures mentioned to enable cover crop use.

The future of cover crops will be driven by farmers and their connections with each other. Ideas for innovation, how to adapt practices, and how to make it practical for Prairie farmers will help move the adoption of cover crops from the initial stages of early innovation to more wide-spread adoption.

Access the full survey report here: https://umanitoba.ca/agricultural-food-sciences/ sites/agricultural-food-sciences/ files/2021-10/2020-prairie-cover-crop-survey-report.pdf

Morrison, C.L., and Y. Lawley. 2021. 2020 Prairie Cover Crop Survey Report. Department of Plant Science, University of Manitoba. https:// umanitoba.ca/agriculturalfood-sciences/make/make-agfood-resources#crops

Your partner in growing success.

Working together, we can ensure a bright future for Canadian agriculture. Investing in innovation is one way that we’re striving to be a strong partner to you. Between 2021 and 2022 alone, we dramatically expanded our portfolio to include 10 new crop protection solutions and new InVigor® canola hybrids. And we thank you for all you do to help ensure the continued success of farming today and into the future. Visit agsolutions.ca to learn more.

Always read and follow label directions.