Boost the power of glyphosate, and expect more yield from your fields. DuPont™ Galaxy™ herbicide helps maximize yield by giving you strong residual control of troublesome weeds in GT (glyphosate-tolerant) corn.

• Go early, at the 3 to 4 leaf stage, and you'll see the results later - in your bin.

• Recent grower trials show higher average yields - an increase of 11.1 bushels per acre when compared with glyphosate alone used on GT corn†

• With Galaxy™ you might only have to apply once, saving you valuable time, fuel and input costs.

• Two active ingredients help protect against weed shifts and resistance. Take your yields to new heights. DuPont™ Galaxy™ shows you how high.

Questions? visit www.dupontpowerzone.com/galaxy

Corn Focus

From the intricacies of using less fertilizer to the pushing the limits on early planting, Top Crop Manager gathers some timely insight from informed industry perspectives.

Here is a quick look at the latest from the laboratory, soon to be in the fields Truck King Review Truck King editor Howard Elmer is back with his review of farm pick-up trucks.

Photo by Ralph Pearce

February 2009, Vol. 35, No. 1

EDITOR

Ralph Pearce • 519.280.0086 rpearce@annexweb.com

FIELD EDITOR

Heather Hager • 519.428.3471 ext. 261 hhager@annexweb.com

CONTRIBUTORS

Blair Andrews

Treena Hein

WESTERN SALES MANAGER

Kevin Yaworsky • 403.304.9822 kyaworsky@annexweb.com

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Kelly Dundas • 519.280.5534 kdundas@annexweb.com

SALES ASSISTANT

Mary Burnie • 519.429.5175 mburnie@annexweb.com

PRODUCTION ARTIST

Gerry Wiebe gwiebe@annexweb.com

GROUP PUBLISHER

Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT

Michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDREssEs TO CIRCULATION DEPT.

P.O. Box 530, simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

email: mweiler@annexweb.com

Printed in Canada

IssN 1717-452X

CIRCULATION

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 211

Fax: 877.624.1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530, simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West - 7 issuesFebruary, March, Early April, Mid-April, July, November and December - 1 Year - $50.00 Cdn.

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issues - January, February, March, April, August, October and November - 1 Year - $50.00 Cdn.

specialty Edition - Potatoe in CanadaFebruary - 1 Year - $9.00 Cdn.

All of the above - 15 issues - $80.00 Cdn.

From time to time, we at Top Crop Manager make our subscription list available to reputable companies and organizations whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you do not want your name to be made available, contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2009 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. such

As hard as it may be to believe, a great deal of comfort comes out of the month of February. Particularly here in the early days of 2009. Against foreground reports of global recession and failing economies is that stalwart and annual reminder that no matter what, farming always presents a series of constants in our lives. As much as farming is a business, it also represents a sense of tradition, and traditions provide structure and stability and from those, we can derive a great sense of comfort.

Despite plant shutdowns and layoffs within the residential and commercial construction sectors, most primary producers have been busying themselves, making some kind of plans for the spring. The ground may be locked in snow and ice for another eight to 12 weeks, yet the process of seeding, spraying and harvesting is never far from the minds of growers. Contrary to some reports outside of farming, growers in Canada continue to grapple with volatility in the commodity market, and in spite of declines in the price of inputs, planning and preparing, and ‘controlling the controllable’ are as much a part of success as being blessed by the weather.

And although February is often disparagingly referred to as the ‘longest month of the year’, it is rife with meetings and workshops, seminars and conferences, all geared to helping growers improve their farming operations. More important, there is a greater sense of renewal and anticipation in this second month of the year, beyond resolutions made in January yet far enough away from the anxiety that comes with the lingering effects of winter in March and April.

February is an important month for Top Crop Manager: It is our annual Corn Focus issue, featuring stories that address the topics of crop, weed and pest management. In this edition,

we also offer the Truck King Review, as a supplement to the Truck King Challenge, and I extend my thanks to Howard Elmer of Power Sports Media Services for his dedication. Last summer he opted to postpone the 2008 Truck King Challenge, in light of the troubles experienced by the truck manufacturers even then. Although this Truck King Review does not have the full participation of all manufacturers, Howard has pulled together an excellent series of model reviews, and written them in a style that is as insightful as it is unbiased.

That is very similar to our sense of tradition at Top Crop Manager, where our goal is to provide our readers with solid, unbiased stories that deal with agronomics, research, machinery and farm business practices. We want to offer you value, right from the moment you turn the first page or click on the website. Meeting that goal has always been part of our tradition, and always will be, just like thinking about farming in February. Because a sense of tradition, even in these trying times, can be comforting. n

Ontario group heads south for closest look.

“Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer.”

Sun-tzu, Chinese general and military strategist (400 BC)

The familiar adage could be used to describe how Ontario’s soybean industry is meeting the potential challenges of Asian soybean rust. Although this aggressive crop disease was detected in Ontario only once late in the 2007 growing season in plots at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, it is important for Canadian crop advisors, researchers and growers to keep tabs on its development in the United States. Several people from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), University of Guelph, the Ontario Soybean Growers and other crop industry representatives got much closer to soybean rust by attending a training session at the University of Florida’s Quincy Research Station.

Albert Tenuta, OMAFRA field crops pathologist, says it was a chance to see soybean rust at its height in one of the hotter spots for the disease in the US. The group also had the opportunity to view various research plots and management trials. “We’ve had germplasm trials down in Florida for the past two years where we have taken some of our crosses, from Agriculture and AgriFood Canada in Harrow and Ottawa, as well as from the University of Guelph, Ridgetown, and are running them down there under significant disease pressure,” explains Tenuta. “We’ve also had fungicide trials down there where we have taken our registered fungicides for rust and applied them under rust pressure in Florida. So this was a great opportunity to learn about the disease, but at the same time see it up close and personal.”

The people who participated in the training learned first-hand how to scout for and identify rust in field situations. They also were able to look at the disease under a microscope and in various conditions. “The biggest take home is that it was actually an opportunity to see it in the field. You can read about it and you can look at it on websites but there’s nothing like seeing it for real,”

by Blair Andrews

says Crosby Devitt, research manager for Ontario Soybean Growers, who was part of the Canadian contingent.

And while the tour participants still respect that rust can inflict heavy economic damage to the crop, they came home feeling a little more confident about being able to deal with the disease whenever it may strike eastern Canada.

“One of the big things that I took away from it is they see soybean rust every year in the southern US, and it’s a matter of when it affects the crop and how bad it’s going to be, ” says Leanne Freitag, an agronomist with Cargill in Princeton. “It was really good to see how they react to it. They’re not afraid.”

Different perspective than in the past

The fear concerning soybean rust has declined substantially since the disease was first detected in the United States in 2004. Education and research have gone a long way toward easing the anxiety. As the disease was making its way across South America and was heading for the United States, and with no germplasm showing resistance, it became clear to US soybean industry officials that they needed to obtain a better understanding of soybean rust. “We had

to find ways to train our infrastructure. We were looking at a pathogen nobody knew and nobody knew how to identify except for a handful of individuals in the US,” says Dr. David Wright, of the Iowa Soybean Association and director of the North Central Soybean Research Program (NCSRP), which sponsors the rust training in Florida. “We had no management recommendations for it, no genetic resistance for it, so it was really scary. Our infrastructure, our scientists and our crop advisors really needed to get up to speed.”

NCSRP consists of the state soybean checkoff boards in Kansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin. Wright says its partnership with the University of Florida has fostered the development of effective management recommendations for Asian soybean rust. He says they have the tools for early detection and there are also fungicides available to help control it. “We understand it a whole lot better. There’s a whole industry that is well-trained in the possible impact of rust and its biology. And I am certainly less fearful of it today than in November 2004.”

Similar feelings are being expressed four years later by the Canadian visitors after seeing the management techniques for themselves. Devitt says the learning experience will be valuable for Ontario crop specialists in the event that Asian soybean rust crosses the border. “One of the values of having the Canadians down there was that now we have agronomists from Ontario with first hand knowledge in scouting for rust and seeing what it can do. But also we learned about control measures such as fungicides, including timing and how well they work, which I think is going to be important in case we have it in Ontario.”

Echoing Devitt’s comment on fungicides, Freitag is of the opinion that triazoles and strobilurins are effective on rust. Triazoles, found in products like Folicur and Tilt, have better activity on rust, but strobilurins, like Headline and Quadris, are stronger on some of the other leaf diseases that could be present. “There are strengths to both chemistries. The two modes of action combined will control a broader disease spectrum and will help with resistance management, too.”

While Freitag, Devitt and other members of the Canadian contingent are more confident about the industry’s ability to respond to an outbreak, they also stress that the industry should not get complacent. In addition to learning about rust identification and control, Tenuta says the group saw the need to be vigilant about this disease, which is still in its infancy in North America. “Soybean rust is evolving. We still have a lot to learn. It can be managed, but we have to be proactive in managing it,” notes Tenuta. “One of the events that really took people aback was the look at the kudzu plots, the main overwintering host of soybean rust in the US, and how well it is infected. Just the difficulty in scouting and managing it in the early phases was something the participants gained a whole new appreciation for.”

While less fearful of the disease, Wright also notes that there is still much to be learned about rust, stressing that it is a pathogen that causes serious economic loss. “We still don’t understand how severe it may become in our upper soybean producing areas. It is definitely severe in Florida,” says Wright. “But we do have the know-how to monitor its movement throughout the United States. We’re still working on other

tools to help us detect it early.”

As the industry expands its knowledge of the disease, Wright recommends people pay attention to the messages from university extension and crop specialists about soybean rust. Ontario is part of the North American soybean rust early warning sentinel plots system. Through the efforts of Dr. Sarah Hambleton of AAFC in Ottawa and Tenuta with OMAFRA, soybean rust spores are consistently trapped in the province each year from June through September. The appearance of the spores does not mean the disease is present. However, the potential for an outbreak exists, depending on the amount of spores and environmental conditions. “We have a huge infrastruc-

ture now that we’re using to monitor the movement of rust and it’s been very effective. There’s a wonderful working relationship between OMAFRA, Canadian scientists and the Ontario Soybean Growers, working closely with their counterparts in the United States. I think it’s a great model for future activities,” says Wright.

About 25 Canadians joined their industry counterparts from Nebraska, North Carolina, Missouri and South Dakota for the training session that was held September 18-19, 2008. Funding for the trip was provided by a grant from Agricultural Adaptation Council’s CanAdvance program. It was part of a three-year project for soybean rust education and communication. n

by Heather Hager, PhD

Researchers from various regions of the Corn Belt have estimated optimum planting dates for corn by examining how yield changes with planting date. Data from the northern US indicate that the corn yield in this region is greatest for planting dates in mid-April to early or mid-May and then decreases with later planting dates. The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), in its Agronomy Guide for Field Crops, gives optimal dates of “on or before May 7 in southwestern Ontario and May 10 in central and eastern Ontario.” However, there is a fair amount of year-to-year variability in the relationship between yield and planting date. Indeed, knowing the optimal planting date is important, but many other considerations come into play when growers are deciding how early they can begin to plant corn in the spring. “When I talk to growers, the first thing would be the window of time they have to get their corn acres in. If it’s a grower who has eight or 12 days of corn planting, he probably has to look at starting as early as it’s fit to start,” says Fred Sinclair, product development manager for Pride Seeds.

Greg Stewart, corn specialist at OMAFRA, and Mervyn Erb, an independent crop consultant located in Brucefield, Ontario, have similar ideas about taking an early window of opportunity to plant at least some fields in April. “If you have a window of opportunity in April when the soil is in good physical shape from a moisture, friability, and soil–seed contact perspective, then you’re tempted to plant on those days, regardless of whether the soil is still cold. If it starts raining on April 30 and rains for 10 days, you will have missed your opportunity to plant early, and that is probably much more of a yield sting than what you might experience by planting in soils that are cold,” says Stewart.

Erb notes that historically, there are only about 100 hours of opportune planting time in early May, and that is if the weather co-operates. “We might get a

nice week of weather in April, and then it might get nasty and stay wet for a week or 10 days. Then you wake up and it’s May 6 and you wonder where the days went. So you want to take advantage of every good situation you can.” What determines this early window of opportunity is the soil condition, specifically moisture and temperature. If the soil is too wet, explains Dr. Steven King, corn breeder with Pioneer Hi-Bred, the sidewalls of the planting trench will smear, causing problems for root penetration later on. “If you do something like that,” says Sinclair, “It’s going to haunt you for the rest of the season because you’ve done something you can’t fix.”

Determining soil fitness is a somewhat qualitative process. “What we do when we’re deciding whether to plant is to take a ball of soil in our hand and see how easily it crumbles,” says King. “If it stays as a ball, it’s not good enough to plant. If the soil crumbles easily, then it’s fit.”

Corn requires a soil temperature of 10 degrees C (50 degrees F) for good, even germination and emergence. The Agrono-

my Guide for Field Crops states, “If average soil temperatures are at or beyond 10 degrees C (50 degrees F), the soil conditions are favourable, and the weather forecast is predicting average to above-average temperatures, then early planting (i.e., April 15 to 25) of at least a portion of the corn crop is recommended. After April 26 or May 1 in areas receiving less than 2700 CHUs (crop heat units), it is generally advisable to pay less attention to soil temperature and to plant as soil moisture conditions permit.”

The timing of corn planting in the spring has become earlier by 10 to 14 days since the 1970s. The ability to plant earlier is mainly attributed to advances in plant breeding and seed treatments, and perhaps changes in climate. Over the years, plant breeders have selected for hybrids that will tolerate cold, wet soil. “For a farmer to plant early to achieve that higher yield potential, he needs to be careful with the hybrid selection,” says King. “If he’s going to grow three or four different

The first new mode of action in cereals in more than 20 years.

New Infinity® represents a giant leap forward in broadleaf weed control. Infinity belongs to an entirely new group of herbicides (Group 27) that provides superior control of the toughest weeds in cereals – including Group 2-resistant weeds.

It is a simple and flexible broad spectrum solution that gives you infinitely better control in wheat, durum and barley.

Visit www.cerealcentral.ca for our complete line of cereal products, programs and resources.

hybrids, he should plant the one with the highest stress emergence score first, and wait until the soil warms up before planting one that has a lower score.”

Seed treatments for diseases and insects have also improved, say King and Sinclair. So even if the seed is planted in fit conditions and then must sit in the soil for a couple of weeks for whatever reason, it is protected from diseases and from insects that might start to feed on it. “Those improved seed treatments definitely have allowed us to plant earlier,” says King.

In terms of nailing down a date before which it is too early to plant, suggestions vary from April 15 to 24, all with the stipulation that soil conditions are fit. It is all about bet hedging and avoiding undue risk. “You’re taking a pretty big risk by putting a lot of corn in the ground April 15,” says Erb. “I guess if I had a really nice stretch of weather April 14 to 17, I might plant a little bit of corn, but I wouldn’t get too carried away; it is pretty early.”

It is not as simple as a decision to plant on the optimum date, says Stewart. “It has to be factored in against things like the size of the planter, how many acres you

can plant in a day, how many acres you have to plant, and whether you have other operations that interfere with your planting efficiency. Therefore, you keep moving the start date of your planting back to accommodate optimum planting.”

Although breeding and seed treatments have allowed earlier planting, it is still a good idea to consider the weather forecast. “Even if the ground is fit and it’s April, if there’s going to be cold rain or snow three days after planting, then I would really hesitate to plant,” says King. “It seems to be that the most sensitive time for a kernel in the ground is three days after planting. That corresponds to when the radicle, the root, just breaks the seed coat, so the seed is more vulnerable at that time.”

Of course, the debate as to how early is too early would be incomplete without knowing whether crop insurance specifies a “do not plant before” date, suggests Stewart. This was a topic of discussion amongst the Ontario Corn Producers’ Association, OMAFRA, and Agricorp in the early 2000s. Lindsay Barfoot, Agricorp account lead for grain and oilseed crop insurance plans, says that these discussions have impressed upon him that because

of year-to-year and site-to-site variability, “it’s difficult to just choose a date on the calendar and say you can’t plant before that or you’re not eligible for insurance. We do require that producers are required for crop insurance purposes to use sound farm management practices, and honestly, we’ve found that to be a workable policy for us.”

Barfoot states that Agricorp relies on OMAFRA’s recommendations for sound farm management practices. “If our customers are doing anything that is not recommended or is outside of accepted practices, their insurance coverage could be jeopardized.” When a claim is submitted, the adjustors take into consideration what practices were used in planting the crop, including soil fitness.

In the end, it comes down to a judgment call. “It’s too early to plant when the soil conditions are not right,” says JeanMarc Beneteau, a grower located in Essex county, Ontario, and a director of the Ontario Corn Producers’ Association. He stresses that it is important for a grower to know his own fields. “Farming is not a science, it’s an art. It’s not that you stick a thermometer in the ground or you take a

HiStick® N/T is a new category of soybean inoculant BioStackedTM with multiple biologicals to stimulate greater root growth and nodule development.

Designed for performance in Canadian growing conditions, HiStick® N/T combines specially selected rhizobial strains that fix nitrogen and Bacillus subtilis – the organism behind Nodulating Trigger ® technology – for greater nodule biomass, faster canopy closure and higher yield. It’s the soundest investment you’ll make all season. Ask your local dealer for HiStick® N/T Inoculant for soybeans

shovel of soil and you see that it’s fit, some people would say it’s too dry; some people would say it’s too wet, and some people would say it’s just right. It’s an art.” He says that nasty weather can occur in any month, so if the ground conditions are right, you plant, and if not, you wait.

“It’s hard to figure out when to plant at times,” concedes Beneteau. “That’s just part of being a farmer. When you have to justify it to a third party like crop insurance, that can be tough too. But I think they have excellent adjustors out in the field who understand when the farmer has pushed the limits too far. I think those instances are rare.”

Once the fall harvest has been gathered, it is not too early to start thinking about spring planting. “Maintenance of your planter is critical,” says Sinclair. The best genetics and seed treatments are not going to substitute for planting at appropriate spacing and depth. After all, notes Sinclair, some things can be controlled and some cannot. “Do what you can to prepare beforehand because Mother Nature is usually going to throw something at you that you can’t control.“ n

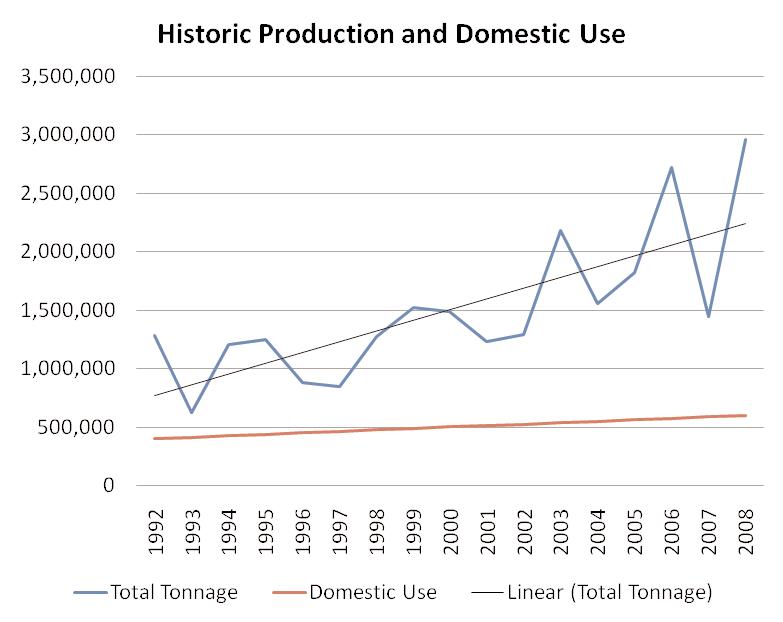

by Tom Jensen*

Most grain and oilseed producers are pleased to realize the recent increase in crop prices after many years of relatively low and at times depressed grain and oilseed prices. There is an overall feeling of optimism in crop production. However, the accompanying increases in fertilizer prices have growers questioning whether or not the changes in crop and fertilizer prices relative to one another justify changes in fertilizer application rates.

A few calculations show that optimum rates of fertilizer have changed very little if at all, while the size of fertilizer expenditure has increased. Associated with the larger fertilizer expenditure is more up-front financing and much more valuable potential crop growing in the field. This combines to create an increased need for careful decision making. Growers can manage this increased need by doing the following.

minimize unwanted losses. Generally this may mean application near the time of planting or in split applications during the growing season for some crops.

Place N fertilizers in the soil in bands to reduce losses compared • to broadcast applications.

Use appropriate starter fertilizer blends precision placed near • or for some crops in the seed-row when planting.

Consider using fertilizer forms or additives that can result in • enhanced efficiency and/or reduced losses of applied nutrients. This may include use of controlled release fertilizers or addition of inhibitors that keep fertilizers in forms less susceptible to losses.

Seek the advice of Certified Crop Advisers (CCAs) and crop • consultants in making fertilizer decisions. Sound advice from an experienced CCA can help a grower determine whether or not there should be changes in fertilizer rates. This is especially important when both grain and fertilizer prices change.

Have soil samples taken and analyzed for nutrient availability

• and adjust fertilizer rates on each individual field. Soil test laboratories are seeing an increase in fields being soil sampled.

CanEast_3.375x4.875 1/11/08 11:39 AM Page 1

Time fertilizer applications to maximize crop utilization and •

An excellent example of a crop planning tool used with farm customers was developed by Keith Mills, a CCA working for a retail grain and crop input company in Western Canada. He works with farm customers growing crops under both irrigated and rain-fed conditions in southern Alberta. His easy-to-use Basic Crop Planner is a spreadsheet program he uses with customers to estimate potential returns per acre for a number of different crops. His customers often use this tool to help them decide which crops to grow if they are considering changes in their crop rotations. The grower can quickly calculate margins per acre by entering realistic crop yields for their farm along with current area prices for crop inputs, including fertilizers, and prices expected for harvested crops.

Keith Mills emphasizes that the yield and input price estimates entered need to be realistic for the area. The Basic Crop Planner is based on variable crop inputs and expected crop yields and current market prices, and does not include fixed costs as this can vary greatly from farm to farm depending on specific land ownership and rental conditions. Mills updates his crop planner each year with average crop prices and input costs for the area where he works. It can be modified by an individual customer especially for expected crop yields depending on specific field conditions, and if an alternate source for crop inputs at different prices is found.

It is interesting to compare information from a number of years for a specific crop and see how changes in crop input prices or operating costs and grain prices affect margin returns considering growers are reducing their rates of fertilizer solely because of increases in fertilizer prices. However, when they saw what the margins were using current fertilizer and crop prices, fertilizer rates have in most cases remained similar to recent years and margins have increased. An example in Table 1 shows estimated returns over the years 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 for irrigated durum wheat.

Operating costs have increased and fertilizer inputs have increased more compared to most other crop inputs, such as herbicides and fuel. The fertilizer costs as a percentage of operating costs are 29 percent, 33 percent, 37 percent and 48 percent, respectively for the years 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008. For example, if the years 2006 and 2008 are compared, fertilizer costs increased

121 percent, but margins increased 202 percent. Between the two years, every extra $1.00 of investment in fertilizer has been offset by $2.49 in increased margin per acre.

Fertilizer rates have remained similar over the past four years even though the portion of the operating costs from fertilizers has increased. Fortunately for growers, the return on fertilizer expenditures remains very positive and optimum economic fertilizer rates have remained similar to rates before the increases in both grain and fertilizer prices. n

*Dr. Jensen is IPNI Northern Great Plains Region Director, located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. Reprinted from Better Crops with Plant Food, with permission of International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI).

Table 1. Estimated margins (total revenue minus operating expenses) for years 2005 through 2008 for irrigated durum wheat, southern Alberta.

Some types of clay are best suited to the crop.

by Blair Andrews

This makes the soil even more clayey than Brookston and it is slightly more

ducted by the Ontario Research Foundation in 1967 showed that early season

ucts for a variety of reasons including food safety, supporting their local farmers and reducing their carbon footprint. Rice is one of the more popular food crops that must travel thousands of kilometres to reach Canada’s major markets. Meanwhile, more rice than ever before is being consumed in Canadian diets. According to Statistics Canada, rice available for consumption set a new record in 2007, reaching 5.2 kg per person.

The combination of local food interest and the increased consumption begs an obvious question: Could rice be grown in southern Ontario? It should be noted that the rice crop being cited here is paddy rice or rough rice, which is grown in rice paddies. Wild rice, which matures in other regions in Ontario, is a different species.

The concept of growing rice in Ontario has been examined well before this era of local food enlightenment. Dr. A. George Caldwell, a retired professor of soil chemistry from Louisiana State University, is a longtime proponent of growing rice in the southern part of the province. He believes the flat, clay soils of Lambton County, in particular, are ideally suited to grow the crop. Caldwell, who grew up in Watford, Ontario, mapped the soils in Lambton County in 1947-48. The key, he says, is that a good part of central Lambton sits on Jeddo clay. “Brookston clay is the major, flat clay soil in Essex, ChathamKent and the southern edge of Lambton County. It’s tile-drained and grows great corn, soybeans and wheat,” says Caldwell. “Jeddo clay has more shale.

In addition to the appropriate soil type, the production of rice requires water. Caldwell says that is something else that Lambton can readily provide. “In Lambton, there’s been a big drainage program to get excess rain water off the land. This actually represents an opportunity to maybe get the water back in. You could use the drains to bring water from the St. Clair River back into Lambton.”

Rice has a history in Ontario Caldwell adds that rice has been grown before in the province. Field trials con-

says the yield was more than 5000 pounds of rough rice per acre. Rough rice is the term that refers to the rice as it comes off the field before processing, where its protective hull is removed. “Rough rice in Houston is 10.5 cents per pound,” notes Caldwell, citing the price in late 2008. “So you’re talking about maybe a $500 to $600 per acre harvest.”

Furthermore, Caldwell says important advancements in rice breeding have occurred since the 1967 research. He suggests that some short-season rice varieties developed for Louisiana

Research in the late 1960s indicated rice could be grown to maturity in southwestern Ontario, and it could grow again, insists Dr. Caldwell.

Raindrops keep fallin’, but I’m not complainin’ ‘cause Roundup Ultra2® herbicide gives me premium preplant performance, every time. And it’s backed by its own unique RiskShieldTM protection package including:

60-Minute Rainfast Guarantee Crop Establishment RiskShareTM Warranty

As always, price dictates whether rice might make it as a commodity in Ontario, and go beyond test plots like these.

would be ideal for Ontario’s climate. Referred to as “90-day” rice, these varieties are planted in March or April in Louisiana for harvest at the end of July. As for Ontario, Caldwell says rice could be planted between the 15th and 24th of May and would likely be combined around the first of September, depending on maturity.

In a more a recent experiment, paddy rice was grown for two years near Holiday Beach in Essex County in the late 1990s. Led by Ducks Unlimited Canada, conservation was a key focus of the project as the flooded fields would produce excellent feeding grounds for waterfowl. Dr. Soon Park, a crop breeder from the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research station at Harrow, Ontario, was one of several people who participated in the study. Now retired, Park, is well known for his work with dry bean crops. But he started his career in 1963 as a rice breeder at a research station in Suwon, Korea, with training stints at an international rice research centre in the Philippines.

The Essex County project used a few varieties of short-grain rice from Cali-

fornia, Japan and Korea. Park says the experimental area yielded a fair amount of rice. “When we harvested, yield was quite good. Actually, I was surprised the second year,” recalls Park, who estimated the yield at five tonnes/ha (about 4460 lbs/ac) with hulls removed.

He adds that a small, experimental combine for edible beans, soybeans and wheat was used to combine the rice.

From an agronomic standpoint, Park agrees with Caldwell’s assertion the rice can be grown in southern Ontario. On the question of it being economically feasible, Park is much less certain. He explains that the yields from the Essex County project were about 30 to 50 percent smaller than those in California. “I’m not sure if our production record will be competitive with California rice. That’s one of the reasons why I have doubts,” he says.

The rice fields also produced broadleaf and grassy weeds, prompting Park to say that more weed science research would be required in future projects.

Justifying the costs

Echoing Park’s comments, Peter Johnson, cereal specialist with the Ontario

Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, says rough rice could be grown in the province but there are several challenges, including a limited amount of potential acreage and high infrastructure costs. “Is it a valuable enough commodity to justify the expenses? Because in most places of the world where they grow rice, the infrastructure already exists in a crop that is really a commodity,” explains Johnson.

Drawing a comparison with horticulture crops, Johnson says the rice scenario would be different than investing in something like Bok Choy production. “The input costs are high but the potential return is huge if you find the market and if you have a good quality crop. I’m not saying horticulture production is easy. It’s still a risk. But at least when you hit it, you can hit it big.”

Conversely, a commodity, says Johnson, does not sell much above the cost of production. As for research, he is not aware of any new studies related to growing rice as an alternative crop. He says many efforts are related to using crops for different applications as well as supplying a bigger portion of our energy needs.

Johnson and Park do not completely rule out the possibility of growing rice in the future. Acknowledging the local food interest, Johnson says there is definitely a transportation advantage to supplying the local market. Park says higher food prices could change the outlook as well. According to the Consumer Price Index, the price of rice increased 2.5 percent from 2006 to 2007. Park has noticed an even higher increase in recent months. “The rice price at the supermarket almost doubled, from $7.99 per eight kilogram bag in 2007 to a cost of $13.50. And sometimes it’s not available. So if the price is still like that it may be a different story for growing rice in Ontario.”

He recommends that an economic analysis would be needed to justify growing rough rice in the province at a commercial scale. More than 40 years later, this recommendation strongly reflects the conclusions of the 1967 research. “It appears that there are commercial possibilities for rice growing in southwestern Ontario. Paddy rice is not an easy crop to grow and whether it develops will depend on cost of product and sale prices that cannot be specified at present,” wrote L.J. Chapman, director of the Department of Physiography of the Ontario Research Foundation n

Seed corn is usually more affected than field corn.

Stewart’s wilt is caused by the bacterium Pantoea stewartii, which is transmitted from plant to plant by the corn flea beetle. Many field corn hybrids have adequate levels of tolerance against the bacterium, so its effects on yields in these hybrids are not usually economically injurious. Seed corn inbreds and sweet corn, however, can be quite susceptible to the disease, and it can be an issue for both the yield of sweet corn and quality of seed corn.

Xiaoyang Zhu, a biologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Ottawa, performs yearly cornfield disease surveys with other biologists from AAFC and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). According to Zhu, Stewart’s wilt occurs mainly in southwestern Ontario and occasionally in eastern Ontario, and has not been found in Quebec since 2000. The disease’s distribution is mainly related to its mode of transmission via the corn flea beetle. Thus, the disease can be tracked by understanding the beetle’s population dynamics.

by Heather Hager, PhD

Corn plants can be infected early as seedlings or later as mature plants, depending on when they are exposed to the bacterium by the corn flea beetle. Other grassy plants and insect species may harbour the bacterium as symptomless reservoirs, but little is known about the extent of their involvement in the disease process.

The ability of the corn flea beetle to overwinter affects the risk of early infection. “The Stewart’s wilt bacterium overwinters in the gut of the corn flea beetle,” says Tracey Baute, field crops entomologist with OMAFRA. “The beetle can then transmit it to the young crop when the crop is just emerging.” Transmission occurs when the beetle takes a bite of the plant and then regurgitates or defecates into the wound. Early infection takes place in spring and often kills the young corn plants.

Baute explains that the disease is less prevalent in eastern Ontario and Quebec than in southwestern Ontario because the harsher winters in the more northerly areas usually kill many of the corn flea beetles. In southwestern Ontario, the beetle’s abundance in spring is relat-

ed to the severity of the preceding winter. Colder winters kill off more beetles, reducing the risk of early infections in corn. Seed treatments may also help to reduce early infections, says Baute. “A lot of seed treatments now do control corn flea beetle, with the exception that the beetle still has to take a bite out of the plant and could transmit the bacterium.” Baute says that the beetles do not have natural predators that specialize on them, but wet weather can be detrimental to them in the spring because it benefits fungi that can kill the beetles.

The surviving beetles eat, potentially transmit the Stewart’s wilt bacterium, lay eggs, and die in late spring. The bacterium is not passed to the eggs, says Albert Tenuta, OMAFRA plant pathologist, so the new adults that emerge in June must acquire the bacterium by feeding on infected plants. They spread Stewart’s wilt to mature plants at around the tasseling stage. This is known as the late phase of infection.

“If we had a cold winter, we would observe few early season effects of Stewart’s wilt, unless it was an extremely susceptible variety,” says Tenuta. “We may see the disease later on in the

E v e r y c o r n a c r e y o u f a r m d e m a n d s b e t t e r c a r e . A n d b e t t e r c a r e s t a r t s w i t h t r e a t i n g e a c h a c r e w i t h

P r i m e x t r a® I I M a g n u m® , e a r l y, a t t h e p r e - e m e r g e n t s t a g e. W e c a l l t h i s p r a c t i c e F o u n d a t i o n A c r eTM . O n c e a p p l i e d t o e v e r y c o r n a c r e, w i t h N o F i e l d L e f t B e h i n d TM , y o u r c r o p w i l l f u l f i l l i t s y i e l d p o t e n t i a l A n d i n t u r n, y o u ’ l l s e e n o t h i n g b u t h i g h e r r

season because both the corn flea beetles and the bacterium would have time to build up.” The late phase of infection may also be supplied by the movement of corn flea beetles from the Midwest Corn Belt on wind currents, says Tenuta. “The later they arrive, the less time there is to infect the plants, and therefore, the effect on the crop is less. But over the past number of years, we’ve been seeing Stewart’s wilt relatively early, which would indicate that we have a base level of infected corn flea beetles that has overwintered from year to year.”

OMAFRA has been evaluating several models that predict the risk of corn flea beetle survival over winter. Generally, these models use December to February temperatures, although Baute says that the extent of snow cover can also be a factor by providing the beetles with some insulation from extreme cold. Predictions of high risk in spring should prompt producers to monitor and manage corn flea beetle populations. “By managing the vector, particularly early in the season, you can reduce the potential impact of the flea beetle and limit its feeding so you have less transmission of the bacterium,” says Tenuta. However, he says that genetic resistance is probably the best management tool to reduce the spread of Stewart’s wilt. “We see the effectiveness of genetic resistance in our commercial corn hybrids, where we have good tolerance to Stewart’s wilt. We’re seeing more in the in-breds as well, but we still have in-breds that are very susceptible to the disease.” This means that seed corn producers need to continue to watch out for the disease.

Export implications

Whereas infection in the young plant can cause it to wilt and die, infection in the mature plant causes leaf lesions, which can contribute to other problems such as stalk rot. In seed corn, mild infections usually remain in the leaf tissue, but severe infections can lead to systemic disease and some infection of the seed. “What we see is that if the plants have more than 75 percent of the leaves infected, some of the seeds may contain the bacterium,” says Zhu.

This is a concern for seed producers because Stewart’s wilt is a quarantine pest for certain countries that import corn seed. The conditions that must be met to export seed to these countries differ depending on the country’s spe-

cific import requirements, says Lois McLean, Ontario network plant protection specialist with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. “Usually for Stewart’s wilt, phytosanitary certification is based on the condition that the seed is grown in an area free from the pathogen, a field inspection during the growing season, or laboratory testing of the seed,” she explains.

In field inspections, leaf tissue is sampled. The presence of the bacterium in the leaf does not necessarily mean that it is present in the seed, so most exporters prefer to test the seed. Samples are tested using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect the Stewart’s wilt bacterium. In the ELISA, a specific antibody that recognizes only the Stewart’s wilt bacterium changes colour if the bacterium is present. “If

we find it and it’s being shipped to a country that has it on their regulated list, we can’t issue a phytosanitary certificate,” says McLean. “In that case, the producer could ship it to a country that doesn’t regulate for Stewart’s wilt or sell it domestically.”

Glen Hellerman, plant manager with Syngenta Seeds Canada, says that seed companies rarely treat for the corn flea beetle unless there is a severe infestation because it is not economically advantageous to do so. “Typically, the results of the seed tests do come back favourable, so even though Stewart’s wilt does exist in the seed corn production area, it doesn’t usually show up in the seed itself,” says Hellerman. “It does exist, but it really has not been a hindrance for Canadian seed companies to do business with other geographical areas.” n

•

• Two GPS+GLONASS receivers built right in, so no need to buy more hardware.

• It works with both manual guidance and automated steering so it’s easy to hook up to your existing steering system.

Tweaking the efficiency of nitrogen applications might pay off in multiple ways.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a potent greenhouse gas that reportedly contributes to climate change. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2007 synthesis report, the current increase in global atmospheric N2O concentration has been caused primarily by agricultural activities such as soil management and nitrogen fertilization. The good news is that farmers can decrease N2O emissions through changes in management practices. At the same time, they may eventually be able to obtain carbon credits, or offsets, for these emissions reductions and sell them in the carbon market for additional revenue.

“N2O is produced in soils as a natural part of the nitrogen cycle,” explains Dr. Philippe Rochette of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Quebec City. A small amount is produced during nitrification, which is the conversion of ammonium (NH4) to nitrate (NO3) by microbes and requires oxygen. Most N2O, however, is produced during denitrification, which occurs when oxygen is not available to microbes, for example, in wet soils. In denitrification, soil microbes use nitrate for respiration, converting it to nitrite (N2O), then to nitrogen oxide (NO), N2O, and finally nitrogen gas (N2). “Since N2O is a free intermediate, it is released in the soil environment and some of it can escape,” says Rochette.

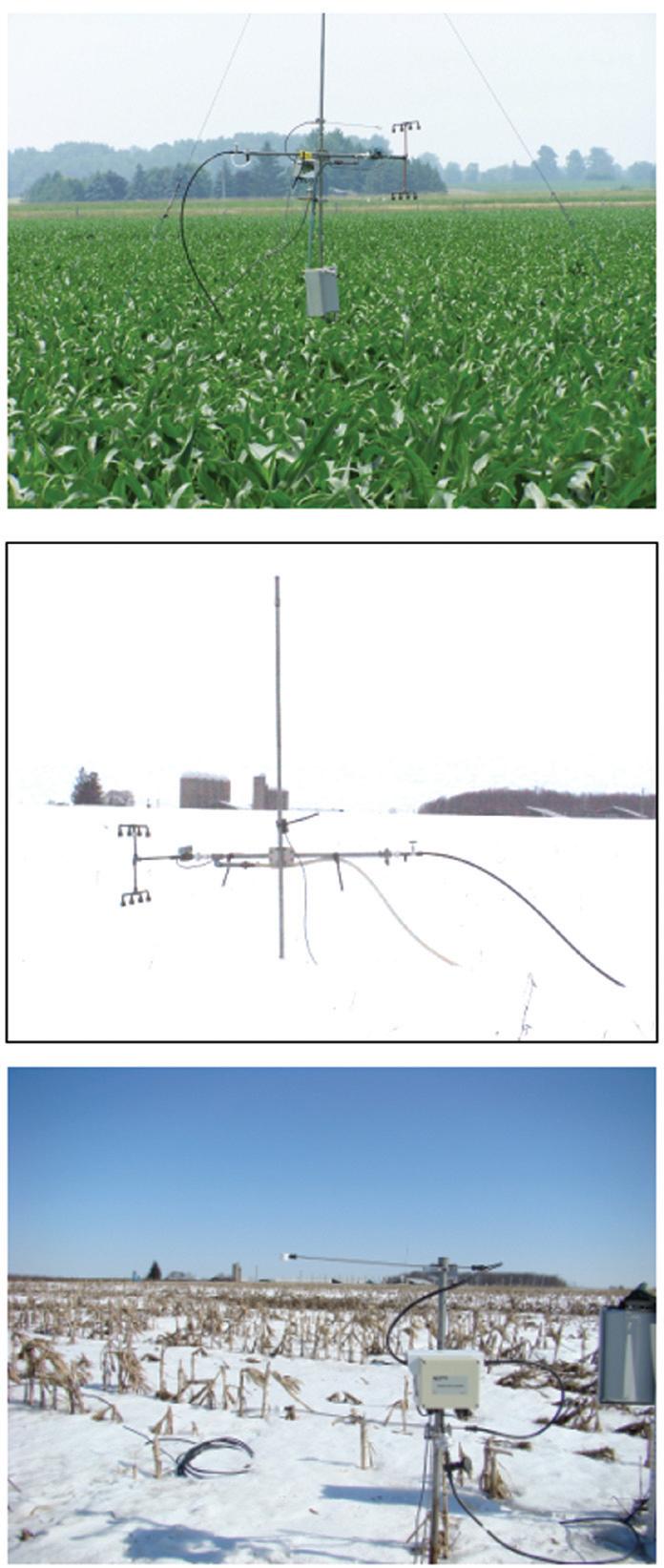

For denitrification to occur, there must be a nitrate source, wet soil conditions in which very little oxygen enters the soil, and a carbon source for the microbes, says Dr. Craig Drury, soil scientist with AAFC at Harrow, Ontario. Although denitrification occurs in all natural ecosystems, specific agricultural practices that affect the soil nitrate, moisture, and carbon contents can enhance denitrification and therefore N2O emissions. Scientists such as Rochette and Drury of AAFC and Dr. Claudia Wagner-Riddle of the University of Guelph are trying to tease apart the complexities of practices that affect N2O emissions. Their data are used to improve annual estimates of emissions and emissions reductions.

by Heather Hager, PhD

to barley at the AAFC Harlaka research farm near Quebec City. “In the two soils that we studied, no-till had no effect on N2O emissions on the sandy loam because even if it increased the bulk density and water content a bit, it didn’t really decrease the aeration to a point where denitrification was really enhanced. But on the clay soil, which was already more dense, wetter, and less aerated, the practice of no-till decreased aeration below a threshold where denitrification was enhanced and N2O was produced,” says Rochette Rochette has also examined 25 published studies that directly compared emissions from no-till and tilled soils. His results suggest that N2O emissions increase under no till in poorly aerated soils, but not in well-aerated soils. “So if you practise no-till, for example, in eastern Canada on a clay soil where the climate is wet, what I am proposing is that this is likely to increase N2O emissions. If you adopt no-till in the prairies where the climate is dry and the soil is well aerated, there will be little effect of no-till on N2O,” says Rochette.

High N applications a factor

Many soil factors affect denitrification and N2O emissions

No-till can be a beneficial practice because it improves soil water conservation and may promote carbon sequestration. However, do increases in soil moisture cancel out the emissions reductions achieved via carbon sequestration because of increases in N2O emissions? In a September 2008 publication in the Soil Science Society of America Journal, Rochette and his colleagues studied the effects of no-till on N2O emissions on a heavy clay soil and a well-aerated sandy loam soil planted

Likely the major factor affecting N2O emissions in agricultural systems is the application of nitrogen fertilizer far beyond the levels available in natural ecosystems. “Agroecosystems are a significant source of N2O, and that has to do with this addition of nitrogen,” says Wagner-Riddle. “Almost every study shows a significant effect of fertilizer additions on N2O emissions.” At a research site at Elora, Ontario, she and her colleagues compared a conventional plowing and nitrogen fertilizer regime with a best management practice of no-till plus reduced nitrogen fertilizer on a corn-soybean-wheat rotation. To reduce the amount of nitrogen applied, they gave nitrogen to young corn seedlings as a sidedress according to soil tests taken during planting. They also gave a nitrogen credit to the legume rotation and reduced the subsequent amount of nitrogen applied, and added a red clover cover crop in the rotation after winter wheat. This reduced the amount of nitrogen applied from 150 to 50–60 kg/ha (134 to 45–54 lbs/ac) for corn and from 90 to 60 kg/ha (80 to 54 lbs/ac) for wheat. “The combination of all

• Highest quality liquid starter fertilizers

• Quality, precision placement, seed safe

• Low impurities

• Low salt

• True solution N-P-K

• Orthophosphate (available phosphorus)

• Highly soluble

ALPINE liquid starters have a neutral pH and are low in both salt index and impurities. These features of our liquid starters enable the product to be placed directly with the seed at planting time. Placement with the seed enables the available phosphorus to be taken up at the critical early stages of growth to maximize yield potential.

ALPINE liquid starters contain a minimum 80% of their phosphates in the available orthophosphate form.

Orthophosphate is immediately available to the plant during the critical early stages of growth. Plant can only take up phosphorus in the orthophosphate form.

of those practices told us that the emissions can be reduced significantly,” says Wagner-Riddle. “Averaged over the five years of the study, the mean annual N2O emissions decreased by 0.79 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare, or 35 percent,” by using the best management practice. “This corresponds to 1.2 kilograms of N2O per hectare or 366 kilograms of CO2equivalents per hectare.”

Interestingly, only 20 percent of the emissions reduction occurred during the growing season, and only for corn. “The majority of the reduction (30–90 percent) was associated with the spring thaw effect,” says Wagner-Riddle. “It’s a beneficial sideeffect of no-till that we hadn’t predicted when we started the experiment.” She explains that with conventional tillage, the soil lacks the insulating blanket of residues and trapped snow that moderates soil temperatures, so soil freezing is more intense. This freezing releases carbon that can be used by the microbes and causes the soil to be wetter during thaw, resulting in greater N2O emissions. So the moderating effect of no-till can depend on the coldness of the winter and the amount of residues.

To further complicate matters, different combinations of the various factors that affect N2O emissions can have different effects. Drury and colleagues looked at the interaction between three types of tillage and two depths of nitrogen placement in the soil (160 kg/ha, or 143 lbs/ac) for the corn phase of a corn-soybean-wheat rotation at Woodslee, Ontario, during the growing season. When nitrogen was applied shallowly, at two centimetres (less than one inch) depth, there was no difference in growing season N2O emissions among tillage types. However, when nitrogen was applied at 10 centimetres (four inches) depth, zone till had the lowest growing season N2O emissions. “Over that three-year study period, N2O emissions from zonetill were 20 percent lower than from no-till and 38 percent lower than from conventional mouldboard plow tillage,” says Drury. This was unexpected because one might think that the emissions from zone-till would be intermediate to those from no-till and conventional-till. This is where the effect of the carbon source becomes noticeable. Drury explains that zone till has the advantages of both no-till and conventional-till: the soil is more aerated than with no-till, but compared to conventional-till, “the carbon residue is still on the surface, not where the most of the nitrate is located.” Both of these factors contribute to minimize N2O emissions.

These and other factors that affect N2O emissions allow for many ways that growers might tweak their management practices to reduce emissions. “It is complex, but it also gives you the opportunity to reduce emissions by placing nitrogen shallower in the soil, using zone-till or no-till, or using crop rotation,” says Drury. “All of these management practices can help you reduce the amount of N2O that’s being lost from the soil. And hopefully, more of that nitrogen would then go into the crop to enhance growth and yield, which is where you really want it.”

Because of its lifespan and effects in the atmosphere, the estimated global warming potential of one tonne of N2O is 296 times that of one tonne of carbon dioxide emitted. A carbon offset is standardized as a reduction in one tonne (1000 kilograms) of carbon dioxide emitted, which is equivalent to 3.38 kilograms of N2O emitted. Theoretically, a grower could adopt specific nutrient management practices that would reduce N2O emissions and

Nitrous oxide emissions were reduced by using specific best management practices to reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer applied to cropland (BMP) compared to conventional practices (CONV). Source: Claudia Wagner-Riddle and colleagues, University of Guelph; research funding provided by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

then voluntarily obtain and sell the resultant carbon credits, if an emissions trading system were in place that allowed regulated industries to purchase carbon offsets, and if nutrient management were an approved emissions reduction practice.

Alberta is currently the only province or territory that has mandatory emissions reductions, an emissions trading system, and carbon offsets as a compliance option. Growers in Alberta have already participated voluntarily in this system under an approved protocol for reduced-tillage practices. To date, more than 1.9 million tonnes of offsets have been created in the Alberta market, and half are from reduced-tillage projects. Currently, there is no accepted protocol for nitrogen fertilization reduction in Alberta.

However, according to Karen Haugen-Kozyra of Climate Change Central, the Canadian Fertilizer Institute is sponsoring the development of such a protocol based on the application of the right form of nitrogen fertilizer with appropriate placement, timing, and rate. Average N2O reductions will be determined for various levels of nitrogen management. A technical seed document based on scientific investigations such as those described here is currently in development as the second step in an 11-step process to seek provincial government approval for the protocol.

In Ontario, the Ministry of the Environment is developing a cap-and-trade program that could be in place as early as January 2010, says Heather Pearson, manager of the Air Policy Instruments program. This development is part of the Provincial–Territorial Cap and Trade Initiative memorandum of understanding signed by Ontario and Quebec in June 2008. One challenge to implementing a cap-and-trade system at this time may be the number of different organizations that are undertaking the same task, but in a slightly different manner. For example, the Canadian federal government, the Western Climate Initiative, the Midwestern Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord, and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative all count Ontario as a member or observer. “It is a very fluid time with respect to cap-and-trade programs, both within Canada and on a broader level across North America, so we need to be very flexible in terms of what we do and propose,” says Pearson. “Our interest is to make sure that we have a program in place that will provide very broad access to Ontario industry in terms of

linking to other systems.”

This summer, 24 Ontario corn producers participated in a pilot project with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs to evaluate aspects of the nitrogen fertilizer reduction protocol. The pilot project “is about making sure that that protocol works the way that it’s supposed to, that the recordkeeping is adequate to substantiate the reductions,” says Pearson. The analysis should be completed in early 2009, and the results “should be helpful in informing the development of an offset program.”

The pilot project did not involve the creation of carbon offsets. “I would be cautious with respect to raising expectations,” says Pearson. “We can’t presume what the mandatory cap-andtrade program will look like at this point in time.” However, even in the non-mandatory market, administrated by the Chicago Climate Exchange, nitrogen fertilization reduction is not yet a method by which producers may receive carbon credits.

Until such protocols are developed and approved, producers may be consoled by the fact that with the high costs of fertilizer, any switch to a management practice that reduces the amount of nitrogen required while maintaining yield will still result in financial savings. These are early days yet for carbon credits. n

For further information on the current science underlying nitrogen fertilizer management and nitrous oxide emissions, see: Snyder, C.S., T.W. Bruulsema, and T.L. Jensen. 2007. Greenhouse gas emissions from cropping systems and the influence of fertilizer management – a literature review. International Plant Nutrition Institute, Norcross, Georgia, USA. Available online at: http://www.ipni.net/ghgreview

by Treena Hein

Learning what weeds are invading fields is much easier with online tools.

Weed identification skills are something that can, and should, be constantly improved. Efficient identification of weeds, especially young weeds, helps growers choose the right herbicide sooner and achieve better overall weed control.

To help farmers do just that, a team of experts has created several online tools available at www.ontarioweeds.com

Headed by Mike Cowbrough, weed management field crop program lead with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, the team includes other OMAFRA specialists, as well as experts from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Wilfrid Laurier University and the University of Guelph.

Visitors to the site are first presented with the “Search” function. “This allows producers to input some key words that will help them narrow down the weed they are trying to identify,” says Cowbrough. “Key words might be related to aspects such as the colour of flower, smell of the weed, or the shape of the stem. The more key words you input, the narrower the given results will be.” Once the search results are presented, users can click on the weed species for more information, such as photos and diagrams.

Those who are a little more certain of what they have can go straight to the “Weed Index” option, which presents an alphabetical list of weeds, but the list can be narrowed according to whether a

grower would like to see grasses and/or broadleaf weeds listed, perennial or non-perennial or noxious/not-noxious. “The glossary helps users learn the official terms for parts of the weed, its plant morphology,” says Cowbrough.

If growers are really stumped, they can click on “Weed ID Services” and send in pictures. The site experts will respond to a query as quickly as they can. “There are certain things that are most helpful to us in terms of pictures,” says Cowbrough. We explain on this page of the site that in all or most of your pictures, you should include a reference object (for example, a coin) so that the approximate size of the plant part can be identified. Also, along with a whole plant picture, take pictures of every distinguishable feature of the plant (e.g., leaf, stem, flower, etc.). It is always better to have too many photographs versus not enough.”

Cowbrough adds that the vast majority of the few weeds that have not been identified by sent-in pictures have been due to several reasons, including poor quality photos and/ or no reference object provided to show the size of the object in the picture. Sometimes, Cowbrough adds, “No additional information is provided, like leaf orientation and other morphological clues, or the information is contradictory to what the photo shows, thus adding confusion.”

However, before photos are sent in, Cowbrough suggests users try the “Search” and also click on “Weed Identifier” on the top right of the “Weed ID Services” page, to see pictures of weeds sent in by stumped farmers. “Over 80 species have been identified,” he says, “and you may find the one you are looking at.” n Weed ManageMent

For growers, using the weed identification tool is as easy as e-mailing a digital photo.

Which one is glyphosate-tolerant?

They both are. You’ve known one for over nine years. Now let us introduce you to the other. Discover a new choice in GT (glyphosate-tolerant) corn from NK.® Get the results you need plus the protection you want against pests with more traits like Corn Borer, LibertyLink,® Rootworm, and Triple and Quad stacks. For more information contact your NK dealer, call 1-800-756-SEED or visit nkcanada.com today. The results you need. The freedom to choose.TM

by Treena Hein

Smart producers are using the tools available on GoCorn.net.

Choosing a hybrid for the upcoming season is an important winter research project for corn producers. The information and software comparison tools made available by the Ontario Corn Committee (OCC) at GoCorn.net, in addition to hybrid performance information from industry, provide a great deal of help in this decision-making.

Included on the site are “Hybrid Corn Performance Trials,” which feature data collected during the 2006, 2007 and 2008 growing seasons. These are identical to what is mailed out to producers, says Greg Stewart, corn industry program lead with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and GoCorn.net contributor.

Under the “Tools and References” section, GoCorn.net also features the ‘1987-2007 Corn Hybrid Selector’ software tool. “This database contains information on yield, moisture and broken stalks,” says Stewart, “allowing farmers to see multi-site and multi-year averages on the hybrids they are interested in. It means farmers can go beyond just looking at a piece of paper with that year’s performance data on a certain hybrid. With this, you can look at how up to four hybrids went head-to-head under OCC trials over up to four years of testing.”

Stewart adds “This software program has been received very positively by the industry.”

Dr. Steven King, senior research manager at Pioneer HiBred, observes that the Selector “simplifies hybrid comparisons.” He says traditional published tables can be cumbersome to interpret, even for analytical types of people, because of the huge amount of data they present.

At the same time, King cautions, “Something that the OCC doesn’t really highlight is hybrid agronomic and disease tolerance characteristics. It’s not just about yield and moisture. You can have all the low-moisture and high yield performance in the world, but if the hybrid has a fatal flaw in one of its characteristics, then those other performance factors don’t matter.” He says some of the key measures Ontario producers should be looking at are stalk and root lodging resistance, stress emergence and Gibberella mould tolerance.

King therefore advises using industry trial databases, some of which are available online, in addition to the OCC data. “If I was a customer, I would want to look at all data out there and know the disadvantages and advantages of each. GoCorn. net is an effective way of presenting independent public trial data. While industry trial databases are not independent, they are much more extensive and include not only small plot performance but also on-farm strip testing and side-byside comparisons, so there are much larger plots and more of them. They also include comparisons with key competitors in the marketplace, in terms of disease factors, yield, drying and much more.”

Under the “1987-2007 Corn Hybrid Selector” tool, producers will also find the “Economic Return Calculator.” This tool

allows farmers to play out profit trade-off scenarios for hybrids of interest in terms of yield, harvest moisture, drying costs and seed cost. King says, “A tool like the Calculator is helpful. Farmers can use that data to make some guesses based on some scenarios to maximize profit per acre, which is the ultimate performance measure.”

Stewart observes “Some of the decisions about hybrids are huge. For example, do you want to spend a lot on a new hybrid with high yield that has a more expensive seed cost, or go with a less expensive seed with lower yield? When things like yield range versus seed costs are presented to the growers, they are quite surprised.” Stewart adds “It’s hard for producers to get a handle on how much difference seed cost and yield alone will make, and this tool allows them to factor in moisture content and drying costs as well.”

The cost of drying has continued to increase during the past decade, says Stewart, and this fall it is the highest it has ever been. “It is an interesting process for growers to evaluate yield versus drying costs,” he says. “Our analysis to date is that planting a shorter season hybrid in order to cut drying costs has often resulted in lower economic returns than what you could get with a full season hybrid,” Stewart adds. The calculator allows growers to input their own drying costs, yields and moistures to explore the options.

New updates were to be added as usual, to www.GoCorn. net in the fall of 2008. Those include drying costs, for example. Stewart notes “These costs are considerably higher than the last time the program was updated.”

Stewart and his colleagues also have plans for improvements and additions to the site, which will be presented as they are prepared. n

Option® Liquid is the only post-emergent sulfonylurea herbicide available in a liquid formulation. That means it’s easier to measure – especially when your fields don’t come in exact 20-acre increments.

Option® Liquid is the only post-emergent sulfonylurea herbicide available in a liquid formulation. That means it’s easier to measure – especially when your fields don’t come in exact 20-acre increments.

Option Liquid can be used from the oneto eight-leaf stage of corn. And it comes with a long list of broadleaf tank-mix partners for one-pass weed control.

So you’re not doing laps out there.

Option Liquid can be used from the oneto eight-leaf stage of corn. And it comes with a long list of broadleaf tank-mix partners for one-pass weed control. So you’re not doing laps out there.

Almost all of the spring wheat crop in Ontario consists of hard red. Flour mills in eastern Canada that use hard white spring wheat have been sourcing it from western Canada, a proposition that becomes more costly every day due to rising fuel costs.

If, however, tests in Ontario during the next couple of years show hard white spring wheat to be feasible for both producers and millers, this crop could be grown in Ontario on a small scale.

Peter Johnson, the cereals specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, says hard white spring wheat is similar to hard red in most respects, but gives an increased yield of flour, a plus for milling companies. “You don’t need to mill off anything past the

by Treena Hein

bran because the colour of the bran is not an issue,” says Johnson. “The white bran also means it works well for whole wheat products as the bran won’t discolour the flour. In addition, the taste of white bran is less bitter.”

Besides being better suited for whole grain food products, which become more popular by the day, hard white spring wheat is also well-suited to the production of Asian-style noodles and other similar “ethnic” foods.

Performance trials

Parrish & Heinbecker (P&H) coordinated a small program with SeCan during the 2008 season to see if hard white spring wheat and some other new varieties can be grown in eastern Canada and whether they have the desired characteristics for milling. “Western wheat is getting pricey,” says Harvey Wernham, manager of P&H Brand Seeds.

Four different farmers grew three hundred acres of AC Snowstar in different areas of Ontario. A hard white spring wheat variety, AC Snowstar was developed at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada-Winnipeg by Dr. Gavin Humphreys and released to SeCan in early 2006. Phil Bailey, SeCan’s eastern territory manager, says hard white spring wheat varieties have been introduced in the past but were never able to compete agronomically.

Bailey considers AC Snowstar, however, a “very competitive” variety, with a demonstrated yield index of 103 percent in Area 2 (southwestern and central Ontario) in 2007 performance trials (see www. gocereals.ca). “This is quite interesting,” he says, “because in the past any hard white spring wheats introduced in the east usually yielded significantly lower than other hard red spring wheat varieties.”

Analysis of the 2008 trials has reflected

this year’s unusually wet weather, says Wernham, with some high DON levels and some acceptable levels as well. Bailey says. “AC Snowstar is certainly still susceptible, but would be considered one of the better varieties when it comes to fusarium tolerance for a white wheat.”

Johnson adds “Every variety is different, but one of the concerns is that in general, white wheats as a class have higher DON concentrations than reds. The reds have phenols that give the red colouration and provide some fungicidal activity, which results in a lower concentration of toxin in the grain than the whites.” He says that because of this, the maximum amount of fusarium in red wheats in eastern Canada is 1.5 percent, but it is one percent for whites, to maintain the grain below 2 ppm of DON concentration for both types of grain.

Next season – and beyond Mill run testing to determine how this variety can be used, as a whole grain or whole grain blend, will be complete by early 2009. “Plans for next year hinge on the mill tests,” says Wernham, “and we have to determine from a grower perspective if agronomically it makes sense to grow it in comparison to other spring seeded crops.” He adds “We want to examine data over a two- to three-year period. If it’s feasible at that point for the grower and acceptable to the milling industry, we would contract growers, and give them recommendations for plant population, fertilizer and fungicide.”

Johnson says that, in terms of the longterm future for hard white spring wheat, “I see that the focus on health consciousness is going to continue to increase, especially with the aging population, and whole grains are certainly one of the things that health professionals point to as having increased health benefits. The desire for exotic foods such as Asian noodles is also growing, and I think the willingness of consumers to pay a little bit more for these products will also grow.”

“Will that mean the hard white market in Ontario will develop?” Johnson asks. “That’s an interesting question. I hope it does, as it offers some great opportunities for Ontario wheat growers, millers and food processors. If companies want to develop something unique and focus on the premium food market in Asian noodles and whole grain foods, there’s growing demand there. Overall, there’s some real potential, but it’s far from being a done deal.” n

Coming to Canada, it works for broadleaf and grass weed control in all types of soybean cultivation.

Herbicide resistance is a constant and pressing problem for soybean farmers, which is why the development and testing of new herbicides is an ongoing endeavour. “One of the key components to herbicide resistance prevention and management programs is the availability of a wide array of herbicides with different modes of action,” says Dr. Francois Tardif, associate professor in Plant Science at University of Guelph. “In Ontario since 1996, resistance to acetolactate synthase inhibitors (Group 2) has developed at a steady rate in many species. In addition, resistance to photosystem II inhibitors (Group 5) is still quite widespread.”

Flumioxazin, says Tardif, is a member of the protox inhibitor type of herbicides (Group 14) that offers new weed management options. “However, contrary to other Group 14 herbicides registered for soybeans in Canada,” he says, “flumioxazin is a soil-active pre-emergent herbicide, which means it provides both enhanced burndown and residual control.” The family of chemicals to which flumioxazin belongs works by inhibiting production of an enzyme important in the synthesis of chlorophyll.

Tardif observes that the availability to Ontario soybean growers of a herbicide containing flumioxazin would provide another weed management option and contribute to resistance prevention. Valent Canada Inc. based in Guelph, Ontario, has recently applied for registration of a flumioxazin-containing herbicide, which the company is hoping will be available for the 2009 season. Valent claims that Valtera promises control of “even the toughest broadleaf weeds” while also suppressing annual grasses in Roundup Ready and Glyphosate Tolerant soybeans as well as non-GMO and identity preserved (IP) beans.

Valent company studies have found Flumioxazin Technical, as it is referred to on registration forms, is practically non-toxic to bees and avian species. It is slightly to moderately toxic to fresh-

by Treena Hein

water fish and moderately to highly toxic to aquatic invertebrates. It does not present a genetic hazard.

Valtera should be applied as a preplant or early pre-emergent herbicide, from 30 days prior to planting up to

three days after planting (before emergence). In burndown situations, it can be used as a foundation herbicide partner with glyphosate in Roundup Ready or glyphosate tolerant soybeans. In research, flumioxazin has been shown to

A great deal of the yield potential of your corn or soybeans is decided very early during the growing season. The best way to enhance yield is to keep your crops clean during this make-or-break period. We call this weed control window the POWER ZONE –the Critical Weed-Free Period (CWFP).

Take corn, for example. Corn’s CWFP extends from the 3-leaf to the 8-leaf stage of growth. A good deal of the crop’s yield potential is decided during this time. When you keep your crop clean, you maximize yields. The same principle holds true for soybeans. In soybeans, the Critical Weed-Free Period runs from the 1st to the 3rd trifoliate stage. You need effective weed control during this period to achieve maximum yields.

Some herbicides, such as glyphosate, only control weeds that have emerged and come directly in contact with the application. Or strictly pre-emergent herbicides that require lots of moisture for activation and may not work well in a lumpy soil, which could be a problem in 2009. For control throughout the CWFP and protection of your crops' yields, you need residual control.

For 2009, DuPont brings you POWER ZONE products for corn and soybeans – proven performance and flexible strategies to achieve residual weed control during the Critical Weed-Free Period.

Galaxy™ performs better than glyphosate alone

It can be applied from emergence to the 6-leaf stage on glyphosate- tolerant corn adapted to greater than 2500 CHU.

Guardian™ provides sharp control and saves time and money

DuPont™ Guardian™ Herbicide can be applied two ways –both of which help keep your soybean crop clean during the Critical Weed-Free Period.

Used as a pre-plant burndown, before either conventional or glyphosate-tolerant soybeans, Guardian™ allows your crop to get established quickly, with less weed competition. Or, applied in-crop from the 1st trifoliate to the 3rd trifoliate in glyphosate-tolerant soybeans, Guardian™ allows you to focus on planting first and spraying later.

Either way, Guardian™ delivers one-pass contact and residual control, including control of tough weeds like dandelion, yellow nutsedge and annual sow thistle. It reduces the need for extra passes over the field, which saves you time and money. With two modes of action, Guardian™ is also an effective resistance-management tool for glyphosate-tolerant soybeans – as well as guarding against weed shifts.