“Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show showcases innovation & diversity. I try to get to Woodstock to see the latest technologies in motion. There’s no other show like it.”

Murray Froebe

Agassiz Seed Farm Ltd., Homewood MB

TILLAGE EQUIPMENT DEMOS

CANADIAN ENERGY EXPO & BIOGAS DEMO

GENUITY TM TECHNOLOGY EXPO

PRECISION SEEDING DEMO

• Featuring Automatic Row Shut-off

COMPACT AG CONSTRUCTION EXPO & DEMOS

QUALITY BEEF CARCASS COMPETITION & RFID TAG READING DEMOS

SOLAR PUMPING & GRAZING DEMOS

LIVE ROBOTIC MILKING DEMOS • Featuring Lely & DeLaval

GROBER YOUNG ANIMAL DEVELOPMENT CENTRE

• Showcasing Live Research Trials

RESEARCH PRESENTATIONS FROM THE ONTARIO AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE • University of Guelph

43,800 ATTENDEES 700 EXHIBITORS

As

Cereal Focus

The word “cereal” covers a broad spectrum, and in this issue of Top Crop Manager, we do too, with stories that touch on weed, disease, and crop management and markets.

Much of a crop’s performance is dependent on the right nutrient balance, and according to many sources, there are nutrient deficiencies that need to be addressed.

Machinery Manager: Four-Wheel Drive Tractors

“Power to the farmer” takes on new meaning, with our annual update on one of the primary “drivers” on the farm, which includes five manufacturers and seven model lines.

and more, on our interactive website.

August 2010, Vol. 36, No.11

EDITOR

Ralph Pearce • 519.280.0086 rpearce@annexweb.com

FIELD EDITOR

Heather Hager • 888-599-2228 ext. 261 hhager@annexweb.com

CONTRIBUTORS

Blair Andrews

Treena Hein

Carolyn King

WESTERN SALES MANAGER

Kevin Yaworsky • 403.304.9822 kyaworsky@annexweb.com

EASTERN SALES MANAGER

steve McCabe • 519.400.0332 smccabe@annexweb.com

SALES ASSISTANT

Mary Burnie • 519.429.5175 888-599-2228 ext. 234 mburnie@annexweb.com

PRODUCTION ARTIST

Gerry Wiebe

GROUP PUBLISHER

Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT Michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

PuBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

RETuRN uNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN

ADDREssEs TO CIRCuLATION DEPT.

P.O. BOx 530, sIMCOE, ON N3Y 4N5 e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Printed in Canada IssN 1717-452x

CIRCULATION

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 211 Fax: 877.624.1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530, simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West - 8 issuesFebruary, Early March, Late-March, April, June, October, November and December1 Year - $50.00 Cdn.

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issues - February, March, April, August, October , November and December - 1 Year - $50.00 Cdn.

specialty Edition - Potatoes in CanadaFebruary - 1 Year - $9.00 Cdn.

All of the above - 16 issues - $80.00 Cdn.

“The most important part of travel is when you come home, because that’s when you see your country with new eyes.”

I know I have used this before in a web editorial but its veracity never ceases to amaze me, especially when I return home from away.

The line belongs to Lewis Black, American commentator and comedian, countering the stereotypical view of Americans that theirs is the greatest country in the world. Instead, he suggests that travel can be an enlightening and, as I interpret it, humbling experience.

In my time with the agri-food industry, I have been very fortunate to broaden my professional horizons. Granted, it has been “only” within the US and Canada, and no, Des Moines, Iowa and Widener, Arkansas, are not the most exotic of locales (although Arkansas can seem quite tropical in midJuly). Still, I have experienced agriculture in America enough to have built a healthy sense of respect for other perspectives. And each trip serves to whet my appetite for another chance to do it all again in another place.

My most recent travels took me to Memphis, Tennessee, on a privatesector tour billed as “Respect the Rotation” (check www.topcropmanager. com for a web exclusive on that trip and look for a full feature on the subject in an upcoming issue). The tour provided a first-hand look at what growers in parts of Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee are doing to battle glyphosate-resistant Palmer pigweed. They are trying everything, from pre- and post-emerge treatments to residuals and physical removal to deal with this weed. The whole three-day experience helped me (again) to see my home, and Canadian agriculture, with “new eyes.”

Although we may not have the same degree of difficulty with resistant weeds here in Ontario, we do have a “heads-up” on the situation. We know we have resistant weeds of

differing species, but not to the same overwhelming extent as down south, where they are dealing with a worstcase scenario.

This advance warning is giving us some time to reflect, as well as step back and admire our lush and full soybeans and a corn crop that is roughly three weeks ahead of schedule.

Yet there is always a reminder that all is not well across Canada or around the world. Western Canada growers have suffered through wet seeding conditions and crops that are faring poorly compared to those in Ontario. And in Russia, excessively hot and dry conditions are threatening millions of acres of crops.

Actually, that is where the humbling part of travel comes to light: seeing other farms and other impacts, listening to other perspectives, learning of other challenges, and sadly, seeing the plights facing others. It reminds me that a) I am not alone in life; b) I am not suffering the same ills nor enjoying the same successes as others; c) that such suffering or success could be worse or better, and d) that I am thankful for all I have.

This may sound more like an editorial befitting of Thanksgiving, but some lessons in life do not wait for the progression of days on a calendar.

Instead, they present themselves plainly, openly and unassumingly.

Ralph Pearce Editor

by Heather Hager, PhD

Researchers are exploring traditional and novel ways to introduce new disease resistance in winter wheat.

In years when temperature, humidity and the timing of wheat heading conspire to create conditions for severe Fusarium infection, outbreaks can cost the Ontario wheat industry millions of dollars. A number of winter wheat cultivars suitable for southern Ontario are ranked moderately resistant to Fusarium graminearum, the fungus that causes Fusarium head blight (FHB), but at least half are still ranked highly susceptible or susceptible, according to testing done by the Ontario Cereal Crops Committee (www.gocereals.ca). And most of the resistance that has been introduced to date comes from the Chinese source “Sumai 3”. So there is definitely room for improvement in wheat tolerance to Fusarium, something that researchers worldwide continue to pursue.

For the most part, finding new resis-

tance means testing many sources of genetic material to see if any have resistance genes that can be introduced into high-yielding, locally adapted cultivars. Both Dr. Lily Tamburic-Ilincic, a wheat pathologist and geneticist at the University of Guelph-Ridgetown Campus, and Dr. Guihua Bai, a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) plant molecular biologist, are using this approach, but their potential sources of resistance genes are quite different. Tamburic-Ilincic is using modern, European and North American wheat cultivars, whereas Bai is going back to the old landraces that farmers planted year after year from seed that survived under local conditions before the advent of modern plant breeding.

Tamburic-Ilincic and her colleagues at the University of Guelph are involved in multiple collaborations to find addition-

al sources of Fusarium resistance. One of these is a project with researchers from Germany “to evaluate modern material from different parts of North America and Europe,” she says. The Canadians hope to introduce Fusarium resistance from European winter wheat into elite Canadian winter wheat, and the Germans vice versa. Another project they have been participating in since its inception in 1999 is the Northern Uniform Winter Wheat Scab Nursery, part of the USDA-funded US Wheat and Barely Scab Initiative. The nursery program evaluates North American cultivars for Fusarium resistance across 10 locations each year, and the best material is used for future breeding efforts.

“The first step is to test the modern, developed varieties for field performance. Then, the most resistant lines are used for new crosses,”

explains Tamburic-Ilincic. She makes crosses using conventional breeding and uses marker-assisted selection to make sure the genes of interest are present. The goal is to “pyramid” resistance genes from several different sources into single wheat cultivars. “Finally, the most promising lines are tested in both countries for yield, quality, agronomic traits, other diseases, and Fusarium resistance,” she says.

Bai’s task may be more difficult, using ancient, locally adapted wheat landraces to find sources of resistance. “Landraces are the same species, but are not modern wheat and can be very ‘ugly’ looking, lacking the typical characteristics we see in wheat today,” he explains. “It can take several years to get that resistance into modern wheat without affecting its agronomic characteristics, even if molecular markers are available for marker-assisted selection of the genes.”

Bai is screening about 100 landraces from China and 30 from Japan. He tests these for Fusarium resistance during a three- or four-year period using controlled, greenhouse experiments. So far, he has identified 10 to 15 landraces that have “pretty good resistance,” he says. Work is ongoing to map the locations of the resistance genes and develop pre-breeding material for plant breeders.

Why use landraces from China? “Most US wheat is very susceptible to FHB,” says Bai. But China had several FHB epidemics in the 1950s, so the surviving landraces likely have at least some resistance to Fusarium. He says that although Canadian researchers already screened many of the landrace collections in the 1970s and 1980s, today’s testing methods are much more sensitive and accurate.

Getting resistance into wheat cultivars for the Great Plains area, where Bai works, is of particular urgency, he says. FHB was never much of a problem previously on the Great Plains. However, in the last few years, it has spread south to areas such as Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma, and all of the currently available cultivars are susceptible to the disease. In the short term, breeders are working to move the resistance from Sumai 3 into the region’s cultivars, with newer resistance genes to be added in the long term as they are discovered.

Fusarium ‘vaccination’

Aside from these usual methods of looking for specific resistance genes, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist Dr. Rajagopal Subramaniam is using a novel technique to study another form of disease resistance in wheat. It works in a similar fashion to a vaccination. “Plants have their own immune system to fight diseases, and we’re trying to boost the existing immune system. We do that by vaccinating with a non-pathogenic strain, called a disarmed strain,” he explains. The wheat perceives the disarmed Fusarium strain as the real thing and boosts its general immune response. That protects the plant from infection by subsequent exposure, not only to virulent strains of Fusarium, but to many other microorganisms. The protection is short, however, lasting only 24 to 48 hours.

The end goal is not to inoculate wheat fields every couple of days, says Subramaniam. Rather, it is to figure out just how the general immune response, called basal resistance, is triggered in the plant. “It involves many different genes; that’s what gives the comprehensive resistance,” says Subramaniam. He and postdoctoral researcher Dr. Charles Nasmith are currently identifying the genes involved, which could number into the hundreds. A small fraction of those would be the ones responsible for recognizing the pathogen and turning on

Pre-exposure to a disarmed strain of Fusarium graminearum (left) protects wheat from subsequent infection by the fungus, whereas wheat that received no such treatment (right) becomes infected.

the rest of the genes, and are of particular interest.

“Once we know how basal resistance works, I think we can really start thinking about long-term, durable resistance, not just for this pathogen, but for any pathogen,” says Subramaniam. “In fact, this is the biggest plant research going on across the world, looking for what the components of basal resistance are.”

These investigations have just begun in the past five to 10 years, he says.

Once identified, the genes involved in triggering basal resistance could be used in plant breeding and genetic engineering. For example, plant breeders could use genetic markers and marker-assisted selection to rapidly check that all of the important genes are present in any new cultivars. And it might be possible to modify the receptors that perceive pathogens, making them more sensitive or quicker to respond.

Basal resistance has a couple of additional advantages compared to the usual form of resistance, called resistancegene-dependent plant defence, that is introduced into crops, says Subramaniam. First, it has little to no fitness cost for the plant. “Normally, when a resistance-gene-dependent defence response takes place, it mobilizes a lot of resources from the plant to fight the disease. Essentially, the outcome of that is the yield is very low. Somehow, the basal response doesn’t seem to affect that at all. That’s well documented, not just by us.”

Second, it should work in other crop species. “Basal resistance is an evolutionarily conserved component in every plant. Every plant has it,” explains Subramaniam. This means that the genes that produce the response are the same or similar among plant species. “We think that if you figure out how to trigger it in wheat, you could also trigger it in other crop species.”

n

Markets for this residue are opening up in auto manufacturing, and much more.

Moving into the second decade of the 21st century, one in which private companies and governments alike are extremely keen to develop fuels and other products from renewable sources, the importance of wheat straw will continue to grow. Lightweight, strong, abundant and environmentally “sexy,” it represents a potential boon to everyone in the supply chain, from farmers on up.

Six farmers in southern Ontario are successfully selling wheat straw that, after processing, becomes the star ingredient in the plastic used to make an interior storage bin in the 2010 Ford Flex. This reinforced resin not only demonstrates better dimensional integrity than a nonreinforced plastic, but weighs up to 10 percent less than a plastic reinforced with talc or glass. More than that, using 20 percent wheat straw to make these bins is

estimated to reduce petroleum usage and associated CO2 emissions 30,000 pounds per year.

The new resin is the first productionready application to come out of the Ontario BioCar Initiative, a partnership between the automotive industry and the public sector aimed at accelerating the use of biomass. It is a four-year project (2008 to 2011) funded by the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, and involves researchers from the Ford Motor Company as well as the Universities of Waterloo, Guelph, Windsor and Toronto.

by Treena Hein

clude it being lightweight and strong and in close proximity to assembly plants. However, we needed to look closely at the needs of each tier of the supply chain to ensure there would be benefits for everyone to make this work.”

At the top of the supply chain sit the automakers, in this case, Ford. “A lightweight material certainly benefits an automaker such as Ford in terms of the fuel efficiency it provides,” says Simon. “Wheat straw is also renewable, which is advantageous in a marketing sense, but in addition, this product is especially environmentally friendly because it actually stores CO2 in the product.”

One step below are the “tier one” partmakers. “These companies make plastic auto parts through injection moulding,” explains Simon. “For them, wheat straw is beneficial to use in place of other materials because it requires a lower temperature of processing, which saves money.”

Dr. Leonardo Simon, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Waterloo, is the principal researcher on the wheat-straw bin sub-project. “During the two years we were formulating this and applying for funding, we had to engage the industrial partners and create a supply chain for the materials we intended to create,” he explains. “Certainly wheat straw possesses attributes that make it suitable for use in plastics for the Ontario automotive industry. These in-

The “tier two” company is A. Schulman, which formulates the composite plastic itself and benefits from using

wheat straw because it provides a lighter plastic, with no compromises for highimpact strength and stiffness. At “tier three” is Mississauga-based Omtec Inc., which processes the straw to a certain particle size to be used in the plastic. “They’ve done a lot of work in creating the methodology to process the wheat straw,” notes Simon. “They have also garnered a lot of knowledge about which part of the straw produces the best particles to make the best composite.” About 80 percent of the straw is from two varieties of wheat, Simon notes, and the variety has not been found to make a significant difference in this application.

At “tier four,” there are currently six Ontario farmers supplying Omtec. As demand grows, the company will look to source additional wheat straw based on production requirements. According to Omtec, although it is not possible to estimate total annual demand at this point, the potential demand is significant.

The price is based on whether the straw is purchased on the windrow versus already baled, and large rectangular bales are the best for efficient shipping. Simon says “We want to continue to bring more value to farmers. There is a lot of potential for on-farm pre-processing.”

Although the wheat straw-containing storage bins, which are black in colour, look no different than ones made of conventional material, “we have been investigating the feasibility and the customer opinion of emphasizing the natural look of the material to see some of the wheat straw fibre,” says Dr. Ellen Lee, Ford’s Plastics Research technical expert.

Ford is also considering the use of this bio-based plastic in numerous other interior, exterior and underbody applications in multiple vehicle lines. “An interior storage bin may seem like a small start, but it opens the door,” says Lee. “We see a great deal of potential for other applications, since wheat straw has good mechanical properties, can meet our performance and durability specifications, and can further-reduce our carbon footprint, all without compromise to the customer.”

Already under consideration are centre console bins and trays, interior air register and door-trim panel components, and armrest liners. Ford is also using soy-based polyurethane seat cushions, seatbacks and headliners, as well as postindustrial recycled yarns for seat fabrics, and post-consumer recycled resins for underbody systems, such as the new engine cam cover on the 2010 Ford Escape.

If there is a future requirement for stronger straw for composite plastic applications, “we will be able to address it fairly quickly and efficiently,” says Dr. Duane Falk, associate professor of plant agriculture at the University of Guelph, although he is not associated with the BioCar Initiative at this time. “We’ve been working on increasing straw strength in barley and have had quite good success by increasing the thickness of the straw walls through direct selection for this trait,” he says. Simon is truly amazed at how fast this project has moved from the lab to industry. “It is very exciting,” he says. “The BioCar Initiative has allowed us to accelerate commercialization, which is very important.”

Beyond automotive

Wheat straw is also being incorporated into other products, including furniture and packaging. In May 2008,

Canadian Geographic magazine made history when it published a special “wheat sheet” issue on paper made partially from wheat straw. Although the wheat straw pulp used in the paper had been imported from China, it was a first in North America; a result of four years of co-operative effort from project partners Canadian Geographic, the Alberta Research Council, Dollco Printing, NewPage and Canopy (formerly Markets Initiative), a Vancouver-based non-governmental organization that seeks to shift heavy paper-consuming sectors away from lesssustainable sources.

In the Canadian Geographic’s special issue, editor Rick Boychuk wrote, “Canadian farmers annually produce an estimated 21 million tonnes of wheat straw, which could be turned into eight million tonnes of pulp and enough paper for 20 million magazines.” Canopy representatives state that wheat straw yields three tonnes of fibre per hectare.

Canopy is hungry to take the next step; the organization stated in November 2009 that “last year’s successful trial with Canadian Geographic showed there is a future for a diversified paper fibre basket. China and India have known this for years, with more than 20 percent of the paper produced in those countries made from crops like wheat, rice straw and sugar cane bagasse. In North America, more than 300 book publishers, magazines and newspapers have committed to supporting the development and use of papers made from agricultural residues.” To develop this market, they are currently asking publishers to fill out an online survey.

If all this were not enough, in October 2009, the first wheat-straw building panels came off a factory production line in Yangling, China: panels that were designed and patented by scientists at the Alberta Research Council’s facility in Edmonton. ARC is an applied research and development corporation that commercializes technological products and services, many of which have a strong environmental focus. They have been perfecting these “oriented split straw board” construction panels, which are similar to wood-based oriented strand board (OSB) since the mid-1990s. It involved creating a machine to split the straw so that it lies flat for better bonding, and then creating methods to produce the panels themselves.

China’s huge appetite for alternative construction materials is fuelled by its lack of abundant wood. These wheatstraw panels are being produced because China does have lots of straw, which is commonly burned by the rural population for heating and cooking. In addition, ARC states that demand for housing in China has forced the excavation of foodproducing land for clay brick-making, yet buildings that use brick and cement are susceptible to earthquakes. Wheatstraw panels provide a safer alternative, and to highlight this, a Chinese school that collapsed in a 2008 earthquake will be among the first buildings to be constructed with them. n

For more information:

• The Ontario BioCar Initiative: www. bioproductsatguelph.ca

• Canopy “Wheat Sheet” information: http://canopyplanet.org/uploads/MIwheatsheet3-screen.pdf

• Farmers interested in selling straw to Omtec, call 905-614-1504 or visit www. omtecinc.ca

by Blair Andrews

The analysis is anything but straightforward and simple.

Now that prices of key nutrients like phosphorus and potash have come down, the 2010 growing season may be the year that farmers can get their fertilizer plans back on track. In the face of soaring input costs during the last few years, many farmers chose to slash their fertilizer use. Combined with higher crop yields, the decision to curb fertilizer applications has raised the issue of soil nutrient deficiencies.

Although they have their suspicions, provincial crop specialists do not have sufficient data to show that Ontario’s soils are suffering from a lack of nutrients. But Greg Stewart, corn specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), is hearing more about lower test levels in discussions on the subject with farmers and agronomists. “It’s difficult to put a scientific number to it, but when I ask for a show of hands at events, asking who has nutrient levels that are medium or lower, I get some fairly aggressive responses from soil test lab people and professional agronomists who are seeing a fair bit of sagging soil test numbers on potassium,” explains Stewart. He adds that the cash croppers who do not have access to manure also are seeing lower test levels.

With relatively higher corn yields during the last few years, Stewart says it is obvious that potassium and phosphorous levels are being reduced at a faster rate than what Ontario farmers have been accustomed to in the past. Moreover, he notes that soybean-dominated rotations are particularly susceptible to lower potassium scores, as soybeans remove about twice the potash of grain corn. “Add that to relatively high potash prices and there are some fairly noticeable instances of phosphorus and potassium levels that are moderate or slipping.”

Horst Bohner, OMAFRA’s soybean specialist, also has seen lower soil fertility numbers. Echoing Stewart’s comments, he is not yet drawing any specific

As growers cut their inputs, there is a greater tendency to see impacts such as potassium deficiency in soybeans.

conclusions about nutrient deficiencies. “It makes a lot of sense when you think about crop removal and the amount of P and K going on. There’s just deficiency in terms of the amount of nutrients going on versus what’s coming off, and economics are a big driver, of course. I think it’s true, but I sure wouldn’t want to defend a PhD with the data we have so far.”

Pat Lynch, former head agronomist at Cargill AgHorizons, has crunched the numbers to show what he says is a phenomenal change in phosphorus and potassium use/additions in the soils across Ontario. Lynch compared the average corn and soybean yields for 2000 to 2004 with the average yields of the next five years. According to Lynch, the average corn yield has increased 29 bushels per acre and the average soybean yield is up by about seven bushels per acre. “When you take a look at the removal of phosphate and potash in the last five years compared with the previous five years, just due to the increase in yields, we have removed approximately 200,000 tonnes more phosphorus and

potash than the previous five years just due to yield increases over that five-year period. And this was during a period that growers were reducing their normal phosphorus and potassium application rates.”

Lynch says removing nutrients through higher yields and then not replacing them with adequate fertilizer applications is producing an undesirable effect, which he describes as mining the soil. “At some point, you have to put what you take out of the soil back into the bank. You cannot keep depleting the soil forever.”

Aside from potassium and phosphorus, Lynch is seeing more fields showing manganese deficiency. This nutrient is deficient every year in the same fields. But because it must be sprayed on, growers are reluctant to address it. He also notes that some fields may even benefit from nitrogen applications. These are fields that have grown a lot of soybeans. He states that he would not expect yield increases with nitrogen on really good soil where a good rotation is practised. Lynch acknowledges that, given the crop’s ability to fix nitrogen from the air, applying the nutrient to soybeans is a tough sell.

Bohner adds that one has to be cautious when discussing nitrogen recommendations for soybeans. “Nitrogen in soybeans is a no-win situation,” he says. “Hundreds of trials have been conducted around the world, including in Ontario, and there is no economic return to applying nitrogen fertilizer for soybeans. The beans look greener for a short time after application, but do not yield more. I conducted five trials (in 2009) with nitrogen fertilizer and not one showed an economic response.”

In making his case for the nitrogenon-beans recommendation, Lynch says that a nitrogen application can be beneficial during conditions when the crop has a difficult time getting started, notably in cold and wet soils. “We think of soybeans being nitrogen-producing and they don’t need any. But I think that in many years, in many fields, those bacteria are not getting going soon enough to get early nitrogen in those soybean plants,” says Lynch. “So I think we should be taking a look at 10 to 30 pounds of nitrogen with soybeans to get them started.”

Lynch adds that he is not suggesting

Manganese deficiency is also a problem, and it is showing up in the same fields in successive years.

that growers put 100 pounds of nitrogen on every acre. But he encourages farmers to see for themselves if it will pay to put 20 to 30 pounds on five or 10 acres. He also comments that the recent decrease in nitrogen prices means that growers should be using more nitrogen on corn than they did in 2009. Using the nitrogen calculator as a guide these levels are 20 to 30 lbs/ac more in 2010 than what the nitrogen calculator indicated for 2009.

Although fertilizer prices have come down, evaluating the input budget will not be an easy task. Greg Stewart notes that the potential of lower commodity prices could make the decision more difficult, saying that farmers have seen higher corn yields since about 2005 without investing much in fertilizer. For Stewart, the key issue is managing around the medium to low soil test levels. “With corn, there’s a fairly reasonable chance that if your soil tests have slid, you can probably make up that difference with starter fertilizers. It’s a different story for soybeans.”

When talking about boosting soybean yields, Horst Bohner says higher levels of potassium and phosphorus are required for the crop to attain yields in the 60 to 70 bushel per acre range. He explains that in various trials, he has noticed that higher yielding fields have high levels of P and K. “As a gen-

eral statement, when I look at the trials we have completed on other subjects, like seed treatments, there’s definitely a trend that higher testing sites yield more. There’s no doubt in my mind that you need significant levels of P and K, if you are going to aim for those top yields. It’s rare to get 60 to 70 bushels in a low-testing field.”

Bohner says soil tests will give farmers a good indication if the nutrients in their soil are being depleted and if they’ll get a response from the fertilizer application. If growers have conducted soil tests every two to three years, he suggests that they graph the results across a 10-year period to see if their nutrient levels are on target.

As for his recommendations for the planning process, Pat Lynch encourages more farmers to set aside part of their budgets for fertilizer. He also advises growers to evaluate their budget with the help of a certified crop advisor. “Instead of shopping around for the best fertilizer prices, they should be sitting down to figure how to best spend their fertilizer dollars. And it could be that this farm is going to get 300 pounds of this blend, that farm is going to get 200 and another farm gets nothing or a starter fertilizer,” says Lynch. “We have too many people looking for a one-sizefits-all fertilizer recommendation, and it doesn’t work.” n

by Heather Hager, PhD

Crop breeding can break a trade-off between growth and insect tolerance that persists in nature.

The ultimate crop species would grow quickly, respond well to fertilizer, and resist herbivores and disease. But is this a realistic possibility? Plant defence theory suggests there is a trade-off: plants can either grow fast or have good resistance to insects, but not both. That trade-off could also affect the reliance of plants on predators of insects, also known as biocontrol, to protect them from insect damage. New research indicates that it may be difficult for such a superplant to develop in nature. Whether this result holds for all plants and whether crop breeding can break the trade-off between growth and insect tolerance are debated.

To study the effects of soil nutrients and predators on plant herbivores and plant growth, Dr. Kailen Mooney and his colleagues at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, compared 16 milkweed species that occur naturally throughout North, Central and South America.

“Maybe the best of all worlds would be to take advantage of nutrients in soil efficiently, to grow quickly, to be resistant to herbivores, and to receive a large benefit from predators of herbivores,” says Mooney, who is now an assistant professor at the University of California at Irvine. The milkweeds’ herbivores were aphids, and the predators were ladybug and syrphid fly larvae, which eat aphids. The researchers examined whether there was a consistent trade-off between plant growth and resistance to aphids, and tested the effects of fertilizer and predators on milkweed growth and aphid densities.

The 16 milkweed species, planted in the same field, varied in growth rate. A growth–defence trade-off occurred, with the faster growing milkweed species having lower resistance to aphids (higher aphid densities) and the slower growing milkweed species having higher resistance to aphids. By accounting for the degree of relatedness among the milkweed species, the researchers concluded that the same pairs of traits evolved together multiple times, rather than once in a common plant ancestor. “Even though, from

a plant’s perspective, it would be more advantageous to be fast growing and to have a strong immunity to insects, in looking at these 16 species, we see that they have one or the other, and can’t have both,” explains Mooney.

“These are not crops; they’re a naturally occurring species. But our results suggest that a species that could break that trade-off would do very well,” says Mooney. He points out that this group of plants is likely up to 20 million years old, and in all that time, natural evolutionary processes have not been able to break the trade-off between growth and insect defence. “So maybe plant breeders of agricultural crops can find a way to break the trade-off, but it suggests that it might be a very hard thing to do.”

However, Dr. Istvan Rajcan, a soybean breeder and geneticist at the University of Guelph in Ontario, disagrees with this conclusion. “In plant breeding, we often screen hundreds, if not thousands, of different genotypes of the crop species to find resistance to a pest or disease. Once found, this resistance is transferred to high-yielding cultivars through hybridization, selection, and breeding,” he says.

Although the initial plant material might not be fast growing or high yielding, crop breeders have been able to transfer resistance to more productive plant lines. A yield drag can occur in the new plant line, but Rajcan says he would not call it a common problem. “Perhaps in nature, the resistant genotypes may not be favoured by the environment as much as the fast-growing, susceptible ones, but it is not true that the combination of these traits is not possible,” he says. As an example, he cites the Rag1 gene, which gives soybean plants resistance to soybean aphid biotypes. Rag1 has been bred successfully into high-yielding soybean lines without producing a yield lag.

Biocontrol effects

Because of the trade-off between plant growth and defence, the Cornell researchers thought that the fast-growing, insect-intolerant species should benefit most from biocontrol by aphid predators. They were surprised to find that was not the case. “Some species barely increased their growth when fertilized; they could be fast- or slow-growing species, but they had little response to fertilizer,” explains Mooney. For those species, he says, the presence of aphid predators had little ability to increase plant growth. In contrast, the species that increased growth most when fertilized also benefited most from aphid predators.

Mooney thinks that these results could have implications for crop breeding. In breeding for crops with higher growth or yield by increasing their ability to use fertilizer, breeders might be selecting indirectly for plants that are relatively intolerant of herbivores and more dependent on predators of herbivores to protect their growth. Also, says Mooney, “if selecting for high response to soil fertility is also selecting for low tolerance to herbivores, that evolutionary trade-off might lower the economic threshold (for insect damage) and mean that even low densities of herbivores could be problematic. It suggests that the economic threshold is being pushed down by the traits that we select for unintentionally.”

This idea remains to be tested, but if supported, could alter crop protection strategies. n

Reference: Mooney, K.A., R. Halitschke, A. Kessler, and A.A. Agrawal. 2010. Evolutionary trade-offs in plants mediate the strength of trophic cascades. Science 237:1642-1644.

by Blair Andrews

Restrictions are many, but niche markets exist.

As Canadian agriculture continues to develop new markets, China’s expanding economy and desire to increase its own food production presents a complex mix of challenges and opportunities. While the sheer size of China’s population makes it an attractive market, it appears the key to success for Canada will be the ability to carve out specific markets.

Like many agricultural economists, Dr. Larry Martin, senior research fellow with the George Morris Centre, an independent agri-food think-tank based in Guelph, Ontario, believes that China’s market potential is tied to its growing middle class. That segment of the population is estimated at 300 million, roughly the size of the entire population of the United States. And while North America and other parts of the world have been talking about recession for much of 2009, Martin says China’s economy continued to grow. “I think that the worst quarter was a 6.2 percent annual growth rate and the last quarter was about 10.7 percent. And their incomes are compounding at a huge rate,” remarks Martin. “It’s almost 10 percent over the last 15 years. As a result, their diets are improving and their consumption of food is increasing, which always takes place when people with low incomes become more prosperous.”

Martin says most of the increase in consumption is in animal products. Besides consumption, a second factor is the loss of arable land in China. According to Martin’s figures, the country is losing 1.1 million hectares (2.72 million acres) of farmland each year. “So they have less ability to produce and fewer resources to produce with. The question becomes, do you produce all the feed at home or do you import? Or do you import the animal products?”

Moe Agostino, managing commodity strategist at Farms.com Risk Management, says the short-term answer is to

import the products. “Russia and China want to be self-sufficient in agriculture and they have backed off lately because they don’t have the producers, they don’t have the money and they don’t have the capital or infrastructure to do it,” he says.

He expects China to follow Russia’s lead and open more of its market to North American meat. Despite estimating China’s hog population at a massive 1.06 billion, Agostino does not think it is large enough to satisfy the increasing demand. “They are going to continually find that as their economy grows at eight to 10 percent, they’re not going to be able to meet the needs of that population growth with their own production. I think they are going to look elsewhere.” While China is a large producer of agricultural products, it is one of the world’s biggest importers of oilseeds. In 2008-09, China was Canada’s top canola seed market, importing 2.87 million tonnes valued at $1.3 billion. “It’s a niche where Canada is filling a particular

space,” says Uliana Haras, associate economist with Export Development Canada. “Canada’s number one export to China is canola seed, having recently surpassed pulp and nickel exports to the country.”

Haras says that China requires more oilseeds to supply its expanding crush industry which is growing in response to the increased demand for livestock feed, edible oils and biofuel. Given that scenario, Canada’s canola industry has good reason to be concerned about a recent barrier to trade with China. In November 2009, China imposed an emergency quarantine order to block Canadian and Australian canola imports that test positive for the presence of Leptosphaeria maculans or blackleg. Blackleg is a fungal disease that can reduce canola yields. China allowed for a ‘transition year’ permitting Canada limited access for the 2009 crop. For the 2010 crop, China has indicated that it will accept no canola unless it is deemed free of blackleg.

As for meeting the future demand of China’s growing middle class, Martin is of the opinion that cash crop producers would benefit indirectly through China’s imports of animal products as opposed to the feed. “If you think through the process, probably the best alternative would be to export the meat because we have the water and they don’t,” explains Martin. “Secondly, it seems to make sense that it probably costs more to export the feed that is required to produce the hogs or the cattle than it does to ship final cuts or carcasses.”

And when dealing with China, cost is a significant factor for the generic commodities. Carl Boivin, commercial manager for Bunge Limited, says that Canada is competing with the rest of the world for the Chinese market. “When we see China coming into the market as a buyer, they come in for big volume, which means you have to be aggressive on your price,” notes Boivin.

For soybeans, South America has a big advantage with record crops and freight rates that are lower than in Canada. Boivin says the Chinese also prefer Brazilian soybeans to North American soybeans because of the higher protein and oil content. Still, Boivin says that China’s market has good potential in the next five years but he adds that Canada will have to be competitive with other countries. “We need to be aggres-

Canada’s soybean growers need to be aggressive in boosting their yields, to take attention away from Brazilian production, which is the current choice of the Chinese.

sive and we need to perform on yields when we harvest,” says Boivin.

Canada’s competitive position is a significant issue for Martin. Next to the rising value of the Canadian dollar and relatively high labour costs, he says government policies may be the largest barriers to improving Canada’s competitiveness. “The single most important problem, in general, facing agriculture in Canada right now, is that it is so difficult to get any product registered that will increase yield or reduce costs or allow us any differentiation in our final products,” says Martin. “We just did a study on the food regulatory side. There are so many wonderful new products that are developed in Canada but can’t get registered in Canada, so they’re registered or commercialized somewhere else and Canadian farmers don’t get to do the differentiation.”

Besides finding ways to improve productivity, Martin says that Canada also needs to sharpen its focus on trade

agreements. “If I was in Western Canada and wanted markets for my livestock, I would want trade agreements that protect me and I’d love to have contractual agreements.”

Haras says investment in China can also play a key role. “Regulatory barriers remain in spite of China’s WTO commitments, yet an increased local presence in the agricultural trading and distribution network could help to increase procurement out of Canada,” says Haras.

Whether the chosen path is securing better market access, improving productivity, developing niche markets or all of the above, Moe Agostino agrees it will be important for Canada to help supply China’s growing demand for food. “We can’t rely on the US anymore. China needs to be part of the vision and strategy,” says Agostino. “We have to work with them because if we don’t, somebody else will, and we’ll just lose that business.” n

The industry’s dream team just got even better. Introducing the TerraGator and RoGator for 2011. TerraGator has the exclusive Continuously Variable Transmission (CVT), so you can cover 279 more acres a day than the competition. CVT is proven transmission technology on over 150,000 self-propelled ag machines worldwide.

RoGator ® and TerraGator® are worldwide brands of AGCO Corporation.

by Carolyn King

Total impact goes below the surface, as well.

In a dark world, a deadly chemical oozes towards an unsuspecting victim. That may be a little melodramatic, but some plants, including rye, do indeed release chemicals into the soil that could suppress other plants. Researchers at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) are exploring rye’s ability to chemically suppress weeds, called allelopathy, with the goal of making rye an even more effective cover crop.

One of rye’s strengths as a cover crop is weed suppression. Along with its allelopathic effect, rye’s vigorous growth outcompetes weeds while the crop grows and results in plenty of crop residue for a physical barrier against weed growth after the crop dies. The USDA’s Drs. John Teasdale and Cliff Rice hope to understand the chemistry behind rye’s allelopathic effect and the importance of allelopathy to rye’s overall effect on weeds.

Their study involves killing a rye cover crop in the spring, then either leaving the crop residues on the soil surface or tilling the residues into the soil. They take weekly soil samples from both treatments, extract the allelopathic compounds from the samples, and test the effects of the compounds on other plants. “We want to determine if the compounds are present in the soil at sufficient concentrations and for sufficient time to be responsible for rye’s allelopathic effects,” says Teasdale, a research leader with the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Beltsville, Maryland.

Just like soil-active herbicides, allelopathic compounds have to remain active in the soil long enough to affect weeds. Teasdale explains, “There are many things that can happen to a chemical when it’s released into the soil. It can go through various types of degradation: degradation by micro-organisms, chemical degradation, photodegradation. It can

be metabolized and changed into other forms. And the rate at which these changes happen is of critical importance.”

To add to this biochemical complexity, rye releases various types of compounds that might have an allelopathic effect. Rice, a chemist with the Agricultural Research Service, initially focused on a group of chemicals called benzoxazinoids. “Over the last 20 years, the benzoxazinoid group have been claimed by many researchers to be responsible for the allelopathic effect of rye,” says Teasdale.

Rice has looked at the many different forms of this group of chemicals and has found that the forms in rye roots are different from those in rye top-growth. However, he has also found that benzoxazinoids probably are not the cause of rye’s allelopathic effect. Teasdale adds, “Basically the results of our research to date indicate that the benzoxazinoids are not in the soil long enough and are not at a high enough concentration in the soil to affect the weeds. When they enter the soil, they seem to be degraded or adsorbed on to the soil quite quickly. Overall, rye residue only seems to release these compounds for a period of a week or two.”

The study’s next step is to test other allelopathic compounds released by rye, including a group of compounds called

phenolics, to look for ones that remain active in the soil for a longer period.

Teasdale notes, “A whole other possibility is that the rye plants simply release enough solutes (dissolved substances) into the soil that there is a pulse of salts, which causes a temporary osmotic effect. So there isn’t any particular compound; it is the net total amount of compounds released, and they cause a change in the electrical conductivity in the salt concentrations in the soil that may affect weeds.”

The study’s results could help point the way to enhancing the weed-control effects of rye. Teasdale gives an example: “Organic agriculture, until recently, has been really dependent on cultivation to control weeds. Cultivation is destructive of soil organic matter, so organic farmers are interested in reducing the amount of tillage. One approach is to use a cover crop like rye. New equipment has been developed to roll a cover crop, so you can roll the rye cover crop, which kills it and leaves the residue flat on the soil surface, and that will physically suppress weeds. From the standpoint of a scientist, it is of interest to know if this weed suppression is because the cover crop just smothers any weeds that try to grow through that physical mat of residue or if the residue also releases chemicals that inhibit growth. If it is just physical suppression, then you’d be looking for rye

and health; inhibit weeds; diseases or insect pests; and/or manage nutrients. Each cover crop type has its own particular strengths and weaknesses in performing these functions.

When choosing a cover crop, a key aspect to consider is how the cover crop type fits with the previous and following crops in a grower’s rotation. Hayes notes, “People should consider what crop is following it and whether there would be disease or insect pest implications from the cover crop. And they need to be sure that any herbicides that were used ahead of the cover crop aren’t going to impact the cover crop.”

Hayes says that some of the more common options for cover crops in Ontario are cereals such as oats, rye or winter

cultivars that produce high amounts of residue. If there is a chemical component to it, then you might develop a breeding program that would try to enhance the production of the particular compounds that are involved.”

does a rye cover crop fit into every crop rotation?

“A cover crop has to be part of the cropping system, so cover crop selection somewhat depends on what the goals are for planting it. Once you know that, then you can zero in on options for which cover crop to use,” says Adam Hayes, soil management specialist for field crops with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Goals for a cover crop might be to reduce soil erosion; improve soil structure

wheat, grasses such as sorghum sudan, pearl millet, or ryegrass; legumes such as hairy vetch, red clover, sweet clover or field pea; and other broadleaves such as buckwheat or oilseed radish. He adds, “There is also some research being done to look at mixtures, like using a broadleaf, a legume, and a grass or a cereal crop together as a mixture. That way, if one does a little better than another in the growing conditions that you have, you would still get pretty good growth overall.”

A rye cover crop has quite a few strengths. “Rye is relatively inexpensive. It will germinate at fairly low temperatures and grow at lower temperatures than some other crops. It provides good ground cover protection; it survives the winter and it is there to help protect the soil from wind or water erosion. Where

people have killed it and planted a crop right into it, it can provide a good mulch, especially on sandy loam or sandy soils, to prevent erosion and help conserve soil moisture,” explains Hayes. “Rye has an extensive fibrous root system, which is really good for helping to build soil structure. You can get a lot of growth from rye and put a reasonable amount of organic matter back into the soil. Research shows it can help to suppress weeds. And it has the potential to be grazed by livestock, if that is part of the equation.”

Rye is also able to temporarily hold nitrogen, which is important in some production systems. Hayes provides an example: “If someone is applying manure after a winter wheat crop and working it into the soil, some of the nitrogen in that manure has the potential to be lost if it’s in the soil from that time until the next spring, when a crop might start to use it. So depending on the cover crop that is grown, it can help to take up some of that nitrogen and essentially tie it up over the winter and then release it in the following year for a crop that would require nitrogen.”

However, rye does not fit in every production system. For instance, if a rye cover crop is grown between two cereal crops, it might harbour disease or insect pests that could affect the next crop. Another issue can be rye’s vigorous topgrowth. Hayes says, “If there’s a lot of rye growth and depending on how it is managed in the following spring, there could be a lot of residue on the surface, which in some years could cause slug problems.”

For growers who decide that a rye cover crop fits with their cropping system, Hayes has a few recommendations. “The seeding rates for rye are typically 90 to 110 lbs/ac, although some growers will seed it as low as about 60 lbs/ac. It can be broadcast on the soil and worked in. Probably the best method for establishment would be using a drill, and obviously if there’s a lot of residue using a no-till drill. Typically, rye is planted in August to October, but the timing often depends on when you have the opportunity to plant it.”

He also reminds growers who are new to using rye as a cover crop to keep an eye on it in the spring to make sure the rye does not get too high. “If you have a warm, wet spring, rye can grow quite rapidly. It can go from six inches to a foot in a pretty short time under the right conditions.” n

by Treena Hein

Getting a handle on Group 2-resistant and multiple-herbicide-resistant weeds.

Although the number of weed species resistant to Group 2 herbicides has not increased appreciably in Ontario recently, says Dr. Peter Sikkema, it is probable that the number of fields with Group 2-resistant weeds is increasing. “For the individual farmer that has Group 2-resistant weeds, it’s a big concern,” notes Sikkema, who is professor of field crop weed management at the University of GuelphRidgetown Campus.

Dr. Francois Tardif, associate professor in plant science at the University of Guelph, says the increasing number of fields featuring Group 2-resistant and multiple herbicide-resistant weeds may be due to more growers engaging in conventional soybean cultivation in 2009.

“Identity Preserved (IP) premiums were strong, so IP acreage was way up,” agrees Regina Rieckenberg, sales and marketing manager for Valent Canada, Crop and Professional Products.

Some of this IP acreage likely was on rented land, says Tardif, on which growers had previously raised Roundup Ready soybeans. This, along with custom combining, could have contributed to the presence of more Group 2-resistant weeds, he notes. “The bigger the farm, the harder resistance is to manage.”

Mike Bakker, BASF’s corn and bean market manager, observes that producers who have not grown IP soybeans in some time may need to relearn how to manage weeds in this context. One of the two main keys is using herbicides with multiple modes of action. “Growers also have to select the correct weed chemistry pre-emergence and post-emergence,” notes Bakker. “That means identifying weeds correctly when they’re small.”

He adds that he observed a larger than expected number of growers in 2009 who waited too long to control post-emergent weeds.

Mike Cowbrough, field crop weed management lead for

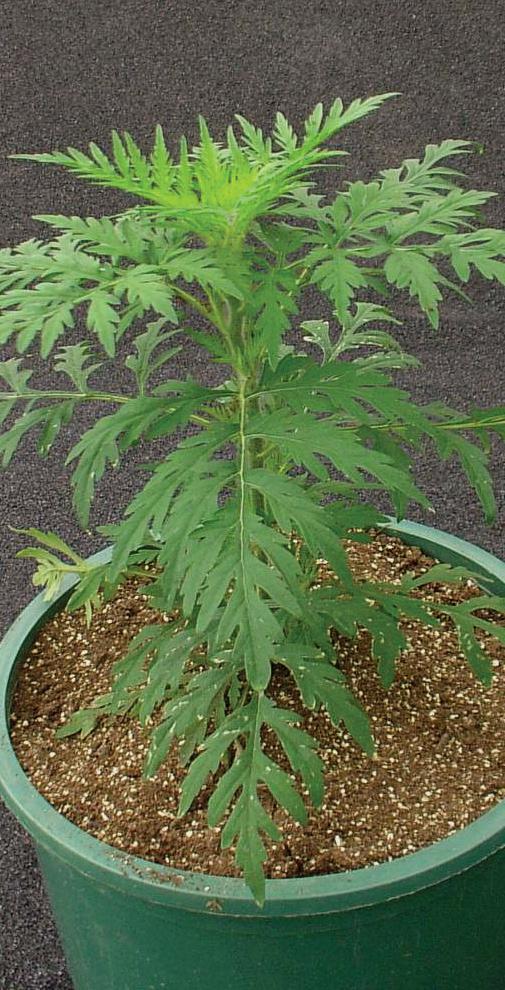

As resistance in various weed species continues to challenge growers, the need is greater to be able to identify the difference between common ragweed (in its seedling stage (top left) and at its mature stage (right)), and giant ragweed (at seedling (middle left) and as a mature plant (bottom left)). all Photos courtesy of miKe cowBrouGh, omafra

the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, believes the use of pre-emergent herbicides is a must. “Growers should definitely use a pre-emergent program because if it fails to some extent (due to the presence of herbicide-resistant

Lamb’s-quarters as a seedling (left) and with toothed margins on its leaves (right) has one of the longer-standing histories of resistance, dating back to 1973 with resistance to atrazine.

programs with multiple modes of action, funded by the Grain Farmers of Ontario and the University of Guelph. However, Cowbrough stresses that before they look at the trial results, growers should first determine what is in their fields. “There are currently 11 weed species resistant to Group 2 herbicides in Ontario since they first appeared in 1996-1997,” he notes, “but a few of these species are closely related.”

For example, waterhemp is a “cousin” to red and green pigweed, while green and giant foxtail are also very similar. Growers in North America should therefore focus on identifying and controlling eight weed species, says Cowbrough. These “obnoxious eight” have been observed as high risk for multiple resistance here in Ontario, and also identified as such on www. weedscience.org, a website that features up-to-date survey results on the global evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds.

Also important to consider alongside the trial results is cost, says Cowbrough. “There are some programs that control the eight with multiple modes of action, but there is a range of prices,” he says. “The trials do not take costs into account, so keep in mind that if one herbicide has four modes of action, but is $50 an acre more than a program that provides two modes of action, it might not be worth it.”

The trial results provide a ranking of the top weed management programs for non-GMO soybeans based on overall weed efficacy and yield (see table).

In terms of other trial results, the following is a listing of herbicides that provide less than 80 per cent control for some specific weeds:

• Barnyard grass: Pursuit (PRE – high rate)

• Lamb’s-quarters (triazine resistant): Boundary (PRE – low rate)

• Pigweed species (group 2 resistant): Pursuit (PRE – high rate)

• Ragweed: Boundary (low rate), Conquest, Pursuit, Pursuit + Valtera.

In terms of tufted vetch, Conquest + Valtera was the only program found to provide reasonable suppression. n

For more information:

• www.plant.uoguelph.ca/resistant-weeds/assets/Resistant_ weeds_ON_2009.pdf

• www.weedinfo.ca

by Carolyn King

Essentially, the crop’s resilience is on the rise.

In the spring of 2009, the prospects for Ontario’s winter wheat crop looked dismal. Yet yields in most areas turned out to be quite good. Looking back, it is easy to see how a combination of better practices, better genetics, and a late season smile from Mother Nature helped growers realize good yields despite weather challenges.

downs and ups from Mother Nature

The 2009 crop certainly faced some tough conditions. Although fall seeding was a little late, the main problem was that immediately after most of the crop was seeded, the weather turned cold and wet.

“The wheat crop went into the winter in very poor shape because of the very cold fall temperatures and wet conditions. Wheat really does not like wet feet until it has emerged. Once it’s emerged and has leaves up, it can transport oxygen from the air down to its roots. But if it’s all underground, it has no opportunity to do that,” says Peter Johnson, cereals specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

Another challenge came in mid-winter. Johnson explains, “In some parts of the province, all the snow melted in February, and then we got extremely cold temperatures around -26 degrees C. I was concerned the cold temperatures with no snow cover might kill wheat. That is extremely rare in Ontario; in fact it only happened once in all of the 20th century. The LT50, the lethal temperature where half of the wheat plants would die, is -22 degrees at the crown, so the -25 to -28-degree air temperatures were very concerning.”

Then, in March, many areas suffered frequent freeze-thaw cycles. “We had a tremendous amount of frost heave particularly in fields where growers didn’t get the wheat planted deep enough or the wheat didn’t have a chance to make any root system to anchor itself,” notes Johnson. “So by April 15th, we had the poorest looking wheat crop that I’ve seen since the spring of 1993.”

There was a brief window of opportunity to apply nitrogen in mid-April.

“When you have a poor wheat crop, early nitrogen really does boost the crop. Some growers put nitrogen on, even though the wheat fields looked awful on April 15th, and many of those fields caught hold of the nitrogen. They got some moisture to help them re-root through late April. And by the middle of May, they looked pretty respectable,” says Johnson.

“Other growers put off making a decision on nitrogen application because they weren’t sure whether they would keep the crop. But around April 22nd, it started to pour rain, and in some parts of the province it really didn’t dry out enough to be able to drive over the field

until May 10th or even May 20th. So growers who chose not to put nitrogen on their wheat crop in mid-April, most of those wheat crops were ‘Roundup ready’ by the time the growers could get back into the field.”

As a result, Johnson was predicting overall poor winter wheat yields for the province. “By May 15th, I was saying, ‘If we break 70 bu/ac we should be pretty thankful, and at very optimistic, maybe we’ll hit 72.’ But then we got into this wonderful weather for the wheat crop with a long, cool grain-fill period, and ample moisture for grain-fill, not everywhere, but in much of the province. So we ended up with a provincial average of 75.2 bu/ac.”

Just as agronomists and growers have been improving how winter wheat is grown, breeders have been improving the wheat that is grown. New varieties have combinations of strengths that allow the crop to perform well even when the weather does not co-operate.

Disease resistance is an important part of those improvements. Dr. Duane Falk, a plant geneticist at the University of Guelph, says, “We’re getting material with better packages of disease resistance, primarily Fusarium resistance, although it’s nowhere near where we’d like it to be, and that is being combined with resistance to diseases like powdery mildew and leaf rust. In the past, it seemed like the varieties that were better for Fusarium were worse for the other diseases and vice versa. Now, we have varieties with good combinations of disease resistance, so they perform closer to their potential even in years when weather conditions are better for the diseases. And that leads to stable, high performance.”

Peter Johnson, cereal specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), emphasizes that improved disease resistance is “a moving target,” with an ongoing need for better varieties. “If we bring out a variety with great powdery mildew tolerance, then that variety becomes a significant player in the marketplace. That puts selection pressure on the powdery mildew disease organism, so it evolves and overcomes the tolerance of that wheat variety.”

Yields and grain quality are also getting better. “The test weights seem to be a little higher and more stable. And the kernel weights seem to be a little higher, which may be a reflection of their improved disease resistance,” says Falk. Johnson also notes that improved standability has contributed to better yields. And Barry Gordon, sales and marketing manager with C&M Seeds, agrees; “We now have varieties that will stand when we put on extra nitrogen. Some of the older, taller varieties tended to lodge with higher nitrogen rates. We brought out a new hard red wheat last year with much shorter straw and it has done very well with standability, and I don’t think we’re alone with these sorts of improvements.”

New varieties developed specifically for Ontario with combinations of important strengths have improved crop performance.

He adds, “I talked to so many growers in 2009 who said they really didn’t know whether they should have kept the crop or not. I walked those fields, and in some cases crop insurance wrote them off and said they’re not worth keeping. But because the weather turned wet, growers ended up keeping them. And a lot of those fields yielded in that 70 bu/ac range, with the really poor ones yielding 70 bu/ac when 50 bu/ac would have been more what we would have expected.”

Falk adds, “If you look back historically, a lot of the winterhardy varieties were quite tall. By emphasizing winter hardiness, we wound up inadvertently with quite a few tall varieties. Now, we are getting better winter hardiness combined with shorter straw.”

Marty Vermey, product manager at Hyland Seeds, points out yet another important consideration. “If we go back probably 20 years, wheat yields were pretty stagnant, with only a few varieties available. Variety development was mainly left to the public sector, which only had one or two breeders, so development was slower. Now variety development is occurring at a much faster rate and therefore crop improvement is a lot quicker and higher. For instance, two or three years ago, we had some tremendous wheat yields, breaking 100 bu/ac in some areas of Southwestern Ontario, which was unheard of 20 years ago.”

Vermey adds, “Our breeders are testing hundreds of thousands of lines every year in the crosses they make to find the best genetics and test them for multiple years. Also, we look for products that can respond in the fertility regime and the disease pressure here in Ontario. You really can’t take a variety from Britain, for instance, that grows in a different climate, different fertility, different fungicide program, and try to develop that product here, because it wasn’t developed and selected for our conditions. We’re breeding and selecting here in Ontario, with Ontario conditions and management practices, and that’s critical for variety development.”

Gordon notes one caveat: “New genetic developments have always been driven by the purchase of certified seed. However, an awful lot of growers want to cut their costs in the short term by not purchasing certified seed. As the purchasing of certified seed declines, the money for research and development declines. That really hurts our industry when we don’t have as many new varieties coming on to the market.”

Falk reminds growers to visit the Go Cereals website (www.gocereals.ca) for information on varieties to fit their own situation.

Johnson says the quality of the 2009 winter wheat crop varied with the local weather conditions at harvest. “In general, across the entire province, we were pleasantly surprised with the quality. We were pretty concerned that we might see fairly high Fusarium levels, but we did not see that. Our falling numbers were acceptable. Our test weights were good. The crop as a whole was sound.”

He notes, “But there were definite pockets and also classes of wheat where there were significant problems.” For example, the Brantford to Simcoe area and the Peterborough to Lindsay area had wet weather at harvest time resulting in tremendous trouble with sprouting, low falling number and mildew. He adds, “Across the province we had big trouble with sprouting in the soft white winter wheat crop because soft white does not have good sprout tolerance.”

Fine-tuning field practices for better yields

The 2009 winter wheat crop is not the only one in recent years for which overall yields were better than expected, despite difficult conditions. OMAFRA tracks provincial wheat yields every year, and those data show a trend of overall increasing yields. Johnson says, “Twenty years ago, average wheat yields were 60 bu/ac. For 2010, our trend line yield is 80.1 bu/ac.”

That upward trend in yield results from a combination of stronger varieties and better practices, helping the crop to perform well even in years like 2008-09 when conditions were not optimal.

Johnson identifies some key improvements in practices. “Starter fertilizer with the seed helps the wheat plant get off to a better start. Using fungicides appropriately at the right time and with the right nozzles, proper nitrogen amounts, effective weed control, the entire management program contributes to better performance. Even simple things like planting depth can make a difference. And we continue to improve in this.”

Marty Vermey, product manager at Hyland Seeds, gives a few examples of practices that helped growers for the 2009 winter wheat crop, such as applying nitrogen in the spring to thin stands and seeding the crop at the right depth for good root development and resistance to frost heave.

Vermey adds, “I remember as a teenager, growers were trying to aerial broadcast seed for winter wheat on their soy-

bean crop. The resulting wheat stands were weak and thin, and in some years the wheat just got heaved out. Nobody really had a great wheat yield. “But nowadays, we try for good management on all our crops: uniform seed depth, uniform emergence, good root system development. We always think about our topgrowth and control disease and insect pressure, but we also have to think about

our roots. A lot of our yield comes from how we take care of our roots, like tillage practices and making sure we’re not compacting our soil. Allow your roots to grow and thrive, having a healthy soil so the root system can spread out and get all the nutrients possible. That helps build the plant and maximize grain development. Getting the plant stand uniform, so that every plant is going to give you 110

percent; that’s where you get your extra yield.”

Barry Gordon, sales and marketing manager with C&M Seeds, identifies four key management categories for a profitable winter wheat crop: fall management, spring management, summer management, and marketing management. “If you just did one of them well, it wasn’t good enough for the 2009 crop because it was challenging. Growers who perfected all four categories were pretty successful.”

For fall management, Gordon says that growers who used starter fertilizers, certified seed and proper seeding depth in 2008 were in a much better position to deal with weather challenges. “We have seen on average five to nine bu/ ac increases with starter fertilizer; it gets the plant off to a better start so it has a better root system going into the winter. And growers who planted certified seed had more uniform stands going into winter. Growers using their own seed didn’t have proper treatments on that seed, so when they had challenges in the fall, at lot of that seed grew unevenly.”

Gordon provides a tip for proper seeding depth, another important factor in fall management. “With a lot of the drills, growers have to put extra pressure behind the tractor wheels when conditions

are less than ideal to get the wheat seed covered behind the tire tracks. If they leave the same pressure across the entire drill, they get extra deep planting in the areas where there are no wheel tracks, which results in uneven depth of planting. And when it is cold and wet, that really shows up with uneven emergence. So growers need to fine-tune seeding depth with their equipment.”

Like Johnson and Vermey, Gordon says an early spring nitrogen application on plants that were very small going into the winter was crucial for good yields in 2009. He also suggests that growers consider using nitrate-nitrogen fertilizer (28 percent UAN applied with streamer nozzles), rather than urea, when soils are cold and wet, so the nitrogen will be readily available.

Summer management is much easier if fall and spring management are performed properly, notes Gordon. “If some part of spring and fall management was less than stellar, then growers had an uneven flowering crop when it came to the summer.” Uneven flowering makes it very difficult to get the correct timing for fungicide applications.

Finally, in terms of marketing, Gordon says 2009 showed the importance of thinking through decisions on which wheat classes to grow. “Many growers

grow soft red wheat, and this happened in 2009, strictly because it takes slightly less nitrogen than the hard red wheat. Hard red wheat (in 2009) was virtually a niche market, so those who grew hard red wheat were very well rewarded. If there isn’t enough supply of a specific class of wheat that the mills want, then it’s going to demand a much higher price.” He adds, “One stellar rule is, if the price is good, sell some!”

Dr. Duane Falk a plant geneticist at the University of Guelph, emphasizes that growers need to know their own situation: which varieties are best, which inputs are required at what rates and at what timing for their own conditions.

However, he cautions, “We don’t know enough yet about everything, unfortunately. It’s really hard to come up with a recipe that will work every year, partly because we can’t predict what’s going to happen down the line. A lot of the inputs need to go on before the problem shows up. And judging that and doing it in such a way that it pays off is still a bit of a risk. Like agriculture in general!”

On the positive side, he says there are more advanced decision-making tools available to help growers make better and earlier judgment calls.

And of course, it never hurts to have a bit of luck with the weather. n

In past decades, tractors have grown, not just in the size of their motors or their sophistication, but in terms of how reliant farm producers are on their performance and efficiency.

In this issue of Top Crop Manager we use our Machinery Manager feature to revisit the topic of four-wheel drive tractors, with seven lines from five manufacturers, including write-ups and spec tables.

As always, we advise you to check with the equipment manufacturers, dealers and other agronomy professionals, for the most up-to-date resources and helpful advice that pertains to your farming operation.

Ralph Pearce editor, Top crop manager

Five Models of Case IH Steiger and exclusive Quadtrac Series 4WD tractors deliver proven wheeled or track performance in challenging conditions. Case IH 4WD tractors feature three frame sizes and an industry-leading long wheelbase and drawbar design for superior conversion of horsepower to pulling power, while delivering superior comfort, convenience and reliability.

The 335 is offered as a standard wheel model or heavy-duty wheel, while the larger 385, 435, 485 and 535 models come as either a standard wheel, heavy-duty wheel or in the Quadtrac design.

In addition, the AFS AccuGuide automated guidance ready system is standard equipment on Steiger and Quadtrac tractors for hands-free operation and improved farming efficiency. A complete factory installed AFS Auto Guidance Ready System is available as optional equipment. Steiger tractors come standard with a Diesel Saver feature that simplifies tractor operation as the engine throttle handle becomes the ground speed selector, a feature that maximizes fuel efficiency.

With these models, there are 22 various configurations, and the 535 also comes as a 535 Pro, with hydraulic power boost and up to 610-hp rating.

Configurations wheeled; heavy-duty wheeled, Accusteer wheeled; heavy-duty wheeled; Quadtrac wheeled; heavyduty wheeled; Quadtrac wheeled; heavy-duty wheeled; Quadtrac heavy-duty wheeled; Quadtrac

Transmission

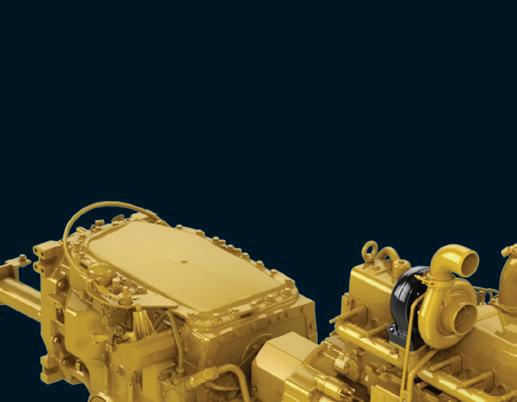

The Challenger MT900C series are the highest horsepower tractors commercially available tractors in the industry and offer four models with gross engine horsepower ranging from 440 to 585 hp. The MT965C and MT975C are powered by a Cat C18 ACERT Tier III diesel engine while the MT945C and MT955C are powered by a Cat C15 ACERT Tier III diesel engine. Transmission: This industry-leading horsepower is transferred to the ground by the robust Cat 16F/4R PowerShift transmission.

Power Management: Allows the engine to communicate with the transmission to increase efficiency and maximize fuel economy.

Hydraulics: Standard hydraulic pump flow rate is 43.5 gpm, while an optional high flow pump offers 59 gpm.

Axles: The MT900C series sets the bar with the industry’s largest standard axles at 5.7 inches (145 millimetres) as well as the largest diameter driveline (rated at 13,720 ft-lbs of torque) to ensure that the horsepower is delivered to the ground.

Tractor Management Center (TMC): The MT900C series features full ISOBUS compliance, which gives the operator complete control of any ISOBUScompatible implements and major tractor functions through the easy-to-use Tractor Management Center (TMC) display. Operators also will appreciate having up to six in-line fingertip hydraulic valve controls and the One-Touch headland management system.

Engine Cat C15 ACERT Tier III Cat C18 ACERT Tier III

Rated speed 2100 RPM

Transmission Cat Powershift 16F/4R

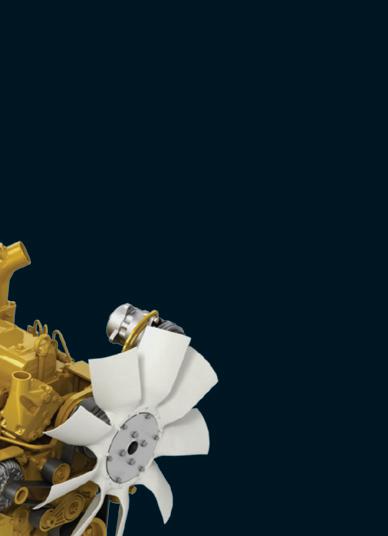

The Challenger MT700C and MT800C series track tractors are equipped with the CAT ACERT Tier III diesel engines. These series of tractors offer 301 to 585 gross engine horsepower and 245 to 425 PTO horsepower.

Transmission: Industry-leading horsepower is transferred to the ground by the robust Cat 16F/4R PowerShift transmission.

Power Management: Allows the engine to communicate with the transmission to increase efficiency and maximize fuel economy.

Suspension: MT700C and MT800C series tractors come standard with the Challenger-exclusive Mobil-Trac undercarriage system and Opti-Ride suspension. Challenger’s Mobil-Trac system maximizes traction and flotation while minimizing compaction. Infinitely variable gauge settings plus multiple belt options adapt the tractor to fit a range of row widths and crop applications.

Hydraulics: Standard hydraulic pump flow rate is 43.5 gpm, while an optional high-flow pump offers 59 gpm. The hydraulic system is equipped with interchangeable one-half-inch and three-quarter-inch remote valve couplers, up to six in-line fingertip hydraulic valve controls, and electronic adjustable rate flow control from the cab, allowing for precise flow rates to meet your different demands.