FIGHTING

SDS WITH SOIL

A new tool to fight this devastating soybean disease

PG. 5

A LOOMING THREAT

Corn earworm packs a big punch for Ontario crops

PG. 10

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

Advancements in wireworm control

PG. 20

A new tool to fight this devastating soybean disease

PG. 5

Corn earworm packs a big punch for Ontario crops

PG. 10

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

Advancements in wireworm control

PG. 20

And gain ground with New 400 and 600 Series Sprayers.

With a redesigned cab and plenty of comfort-enhancing features, the new 400 and 600 Series Sprayers allow you to cover more acres per day in maximum comfort. Reduce overlaps and gain chemical cost savings with the optional ExactApply™ nozzle-control system, which helps you spray with greater accuracy. Plus, these sprayers come loaded with precision ag tools to help you gain ground in your operation.

See what you have to gain at JohnDeere.ca/Ag.

PESTS AND DISEASESPESTS AND DISEASESPESTS AND DISEASES

5 | Suppressing sudden death syndrome with soil

A new tool to fight this devastating soybean disease.

By Carolyn King

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Lessons learned in a year By

Stefanie Croley

10 | Corn earworm: a looming threat

An early arrival in Ontario plus Bt resistance could be a double whammy. By

Carolyn King

8 Research sheds light on pinto bean darkening

By Julienne Isaacs

2o | Know your enemy Advancements in wireworm control. By

Alex Barnard

PESTS AND DISEASES

13 Prepping for the pollen beetle By Carolyn King

CATCH UP ON THE LATEST EPISODES OF AGANNEX TALKS

A new season of AgAnnex Talks, the podcast produced by the agriculture brands at Annex Business Media, launched March 1. Catch up on the latest episodes, with topics like soil health, precision ag technology and more – available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. AgAnnex.com

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Our April issue is traditionally focused on pests and diseases, and in our April 2020 issue, I wrote about how disease management and prevention is a top-of-mind issue for producers, and one that the ag community has a lot of experience in.

When I first wrote that column in early March, the media was abuzz with talks of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19. Little did we know, last March was just the tip of the iceberg. Here we are a year later still in the midst of the pandemic, and still talking about it. I’m willing to bet it will be a point of conversation for many years to come.

An epidemiologist or plant pathologist I am not, but I see parallels between a disease or virus that affects humans and one that affects plants – namely, the unpredictability. When a new threat emerges, there’s much to be learned about it: how to diagnose it, management, prevention, and the short- and long-term effects. The scientific community works together to find solutions, and for a while it seems there are more questions than answers. Eventually there’s a glimmer of hope at the end of the tunnel in the form of a means of management or prevention. Last spring, we didn’t know a lot about the novel coronavirus, and while we still don’t have all of the answers, we’ve come far in a short period of time.

The same can be said for crop disease management, or even insect pests or troublesome weeds. So much happens behind the scenes, through lab work and fieldwork, to find answers to the unknown – and the work is never done. Over the last several years, we’ve published countless articles on diseases like sudden death syndrome and Fusarium head blight, or pests like wireworm and earworms. As threats grow and change, so too do the methods in the lab and field, and with help from the entire industry, more and more solutions and management options become available.

On both the pandemic and agronomy fronts, we’ve learned a lot in the last year, and sometimes there’s so much information that it’s hard to wade through and determine who to listen to. I’ll leave you with a piece of advice that came from Dr. Don Flaten’s presentation at the Top Crop Summit, held virtually in February. Recently retired from the University of Manitoba where he was a professor in soil fertility, crop nutrition and nutrient management, Flaten shared several anecdotes and lessons learned over his 45-year career as a soil scientist, but this one in particular received rounds of virtual applause from the audience: remember the difference between science and non-science and note that non-science sounds a lot like nonsense.

Best of luck as your season begins.

An intriguing discovery opens the way to developing another tool for fighting this devastating soybean disease.

by Carolyn King

With a dash of serendipity mixed into their scientific studies, researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Harrow, Ont., have made a fascinating discovery: a field with soil that naturally suppresses soybean sudden death syndrome (SDS).

This discovery could be the first step toward adding a new tool to the small toolbox available for managing this yield-limiting disease.

“Sudden death syndrome is caused by Fusarium virguliforme, a soil-borne fungus. It seems to colonize the roots of soybean plants shortly after the seeds germinate and causes root rot. Then, if the environmental conditions are favourable, the pathogen starts to produce toxins,” explains Owen Wally, the crop pathologist who is leading this research.

“The toxins get translocated up the vascular tissue to the leaves. The leaves react to the toxin and start to turn yellow, giving the leaves that characteristic SDS symptom of yellowing between the veins, which we call interveinal chlorosis. As the disease progresses, the chlorosis turns to necrosis and can eventually lead to the death of the entire plant.”

He notes, “You will often see yield losses in excess of 25 per cent due to the disease, and it can cause close to 100 per cent losses when it is very severe.”

According to Wally, SDS is favoured by high moisture conditions throughout the growing season. In addition, it likes cooler temperatures at planting for increased root colonization, but then it needs warmer temperatures for the production of toxins and symptom development.

SDS is a fairly recent invader of Ontario soybean fields. Symptoms of the disease were first noticed in 1993 in Chatham-Kent. The first formal identification was in 1998, based on testing of samples collected in 1996, which confirmed the presence of SDS in Essex, Chatham-Kent and Lambton counties.

Since then, the disease has continued to spread. Wally has been working with Albert Tenuta at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs on SDS surveys in Ontario. Those surveys show the disease is now also in Elgin, Norfolk, Middlesex, Oxford and Perth counties.

These days, SDS is one of the most important soybean diseases in southwestern Ontario.

“We’ve found that sudden death syndrome seems to be getting progressively worse in a lot of locations, particularly in the south. Over about the last 10 years, more and more areas seem to be getting hit with it a little harder each year,” Wally notes.

“In some areas, particularly around western Elgin County, growers have decided not to grow soybeans anymore because they can’t get enough yield from the crop due to the disease.”

The discovery of the SDS-suppressive soil had its beginning two decades ago. “In the late 1990s and early 2000s, my predecessor at Harrow, Terry Anderson, was starting to work on sudden death syndrome. He happened to find a field about a kilometre south of the Harrow research station with high levels of the disease. Because of the high SDS levels and the logistically convenient location, they decided to use the field for screening soybean lines and varieties for response to the disease. As a result, soybeans have been grown continuously in that field for about the past 20 years,” Wally explains.

“However, Terry noticed the SDS levels in the field were getting progressively lower over time. By the time I started with AAFC in 2015, we weren’t seeing a lot of SDS symptoms in the field. But we didn’t have a really good explanation for why the SDS levels were declining.

“It wasn’t until we started to do some indoor testing with the soil from that field that we discovered the soil had the capacity to suppress sudden death syndrome.”

Wally explains that this discovery actually happened by accident. He and his research group were working on a greenhouse SDS study at the time. Their idea was to use field soil containing the pathogen, rather than their regular potting soil, as a way to increase the level of SDS symptoms in their greenhouse plants for their bioassays.

So, in their initial experiment, they used soil samples from that field near Harrow. They autoclaved some of the samples to sterilize the soil, killing all the microbes, and left the rest of the samples unsterilized. Then they inoculated the sterilized and unsterilized samples with Fusarium virguliforme, and planted their soybean varieties in the samples.

They had expected to see more SDS symptoms in the soybeans grown in the unsterilized-plus-inoculated field soil. To their surprise, the opposite was true.

The plants grown in the unsterilized-plus-inoculated field soil had essentially zero SDS, whereas the plants grown in the sterilized-plus-inoculated soil had a lot of SDS symptoms.

Somehow, one or more of the microbial species in that field near Harrow were able to suppress SDS.

To try to understand what was going on, Wally’s research group then conducted the same autoclaved versus non-autoclaved tests on soil samples from other fields in the region. But only the soil from that one field near Harrow produced the surprising result.

Additional tests with that soil confirmed that it had a strong ability to suppress SDS. Wally says, “Using even a small amount of the live, non-autoclaved soil could shut down the formation of sudden death syndrome.”

Answering some key questions

“We figured that this soil’s ability to suppress the pathogen

developed because it has been in continuous monoculture soybean production for so long,” Wally explains.

“Other research has been done on other pathogens in situations where the same crop is grown continually; examples include Rhizoctonia in wheat and cauliflower, take-all in wheat, and soybean cyst nematode in soybean, among others. Those studies show that in crop monocultures, the soil microbial community can naturally evolve to become antagonistic or suppressive to the pathogen.”

You can imagine how that might happen. A pathogen’s population gets higher and higher over time in the ongoing presence of susceptible hosts and favourable environmental conditions. But along with that, the populations of microbes that parasitize or prey on that pathogen may also get higher and higher because they have more and more ‘food’ to eat. And sometimes those microbes may become so effective at attacking the pathogen that it is no longer a threat to the crop.

Wally recognized that the SDS-suppressive soil might offer a path towards developing a new tool for fighting SDS. So he and his research group have set up a field experiment to try to answer some key questions: How did this suppressiveness develop? How long does the suppressiveness last if the soil is rotated out of continuous soybeans? Which particular soil organisms are involved in suppressing SDS? And is there a way to encourage that suppression in other fields to help protect soybeans against SDS?

They have split the SDS-suppressive field into three sections. The centre section is still in continuous soybean production, and the two sections on either side are in a corn-soybean rotation, a common rotation in this region. For comparison, they have also set up the same experiment in two non-SDS-suppressive fields, one in Elgin County and one in Chatham-Kent.

They conducted these field trials in 2019 and 2020 and will be continuing them in 2021. The trials involve measuring key parameters like soybean yields and SDS levels. They also collect soil samples for greenhouse bioassays to see if soybean plants will develop SDS when grown in the soils.

As well, they are sequencing the DNA in the soil samples so they can track how the soil microbial community differs from section to section, field to field, and year to year. Although they haven’t been able to conduct much of the project’s lab work yet due to COVID restrictions, they hope to get back into that in 2021.

For the first two years, the project was funded through AAFC and the Canadian Agricultural Partnership by tacking the work onto some other soybean research. Beginning in April 2021, Grain Farmers of Ontario will provide funding so the project can continue for three more years.

“Within the next three years, we hope to get at least a pretty good indication of what organisms or groups of organisms may be causing the suppressiveness,” Wally says.

“If we find some promising candidate microbes within the next two years, we plan to do some initial chemical or biochemical assays on those organisms to see if we can mimic the SDS suppression in the lab. We hope to apply the microbes as a seed treatment or soil amendment, or perhaps to add some kind of organic amendment or something to the soil that encourages those organisms to become more prevalent.”

Looking ahead, he says, “If we could find a management

practice/biocontrol practice that is good enough at controlling sudden death syndrome, then we could keep the disease down to a certain level. We might be able to combine this practice with soybean varieties that have fairly good tolerance to SDS. That might allow growers to continue to produce soybeans in areas that are very high risk for the disease.

“We might also be able to help maintain soybean yields in some areas that currently have low SDS levels and to slow the spread of the disease further into Ontario.”

Wally concludes, “It’s a pretty exciting opportunity. Our goal is to maintain or increase the economic sustainability and environmental sustainability of soybean production. We hope to get the best of both worlds by being able to modulate the soil microbiome to help control sudden death syndrome.”

A new study has uncovered a gene that contols a slow-darkening trait in pinto beans.

by Julienne Isaacs

Most plant science research chugs along quietly for many years before major discoveries are announced and publicly heralded.

This was the case for Sangeeta Dhaubhadel, a plant molecular biologist/biochemist at Agriculture and AgriFood Canada’s London Research and Development Centre in Ontario. Dhaubhadel recently discovered a gene that controls a slow-darkening trait in pinto beans. The discovery was years in the making and required the efforts of many people in labs around the country.

All pinto beans darken with age, and the older they get, the darker they become; this is called “post-harvest seed coat darkening.” There are two types of pinto beans: slow-darkening pinto beans darken more slowly after harvest, but these are less

popular with producers due to their lack of agronomic traits like high yield and adaptability. Regular-darkening pinto beans have better agronomic traits, but their seed coats darken comparatively quickly post-harvest. It sounds innocuous, but regulardarkening can be a serious problem for producers.

Consumers tend to associate darker beans with longer cooking times, Dhaubhadel explains. But unless they’re stored in ideal conditions, pinto beans can start to darken after only six months post-harvest, she says.

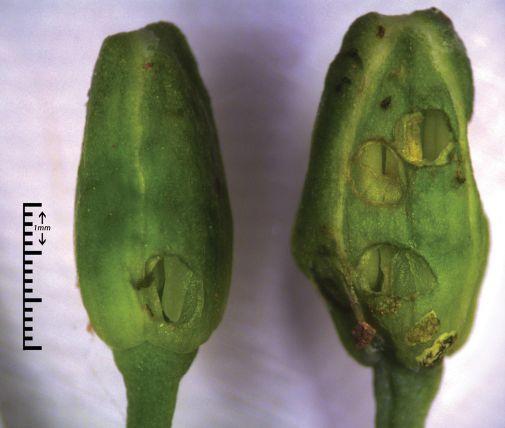

ABOVE: Top row (L-R): aged (showing seed coat darkening) and non-aged slow-darkening pinto beans. Bottom row (L-R): aged and non-aged regular darkening pinto bean.

INSET: Nishat Islam (L) and Sangeeta Dhaubhadel (R) pictured in the lab.

“Older beans take longer to cook. So early darkening in pintos gives the impression of being old to consumers, who tend to avoid these beans,” she says.

Most of Dhaubhadel’s research portfolio focuses on soybean isoflavonoids, natural compounds produced in the plant that have human health benefits and can also be important for plants’ resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses.

She became interested in working with pinto beans when she realized that a different branch of the same molecular pathway that produces soybean isoflavonoids is responsible for pinto bean darkening.

Before Dhaubhadel took on pinto bean research, researchers at the University of Saskatchewan had already discovered that post-harvest seed coat darkening is linked to the fact that these beans produce more of a compound called proanthocyanidin. “They compared the seed coat between slow-darkening and regular-darkening and they found that regular-darkening pintos had more proanthocyanidin,” she says.

Dhaubhadel began working with University of Saskatchewan researcher Kirsten Bett to understand this process. In 2014, the common bean genome sequence was published, which made the work go faster.

A University of Saskatchewan study showed that the gene responsible for the darkening trait lies between two markers. Because the distance between the two markers could be very short or very long, Dhaubhadel and her PhD student Nishat Islam used the bean whole genome sequence to look for the markers, then examined the regions between and around the markers, looking for the gene.

Once they found the gene – called P for “pigment” – they characterized it to ensure it was indeed connected with seed coat darkening. Then, another study was published by another research team, showing how the gene worked in white beans, and this allowed Dhaubhadel and Islam to understand how the P gene influenced the speed of darkening.

“If this gene product is non-functional, then the colour becomes white. If it is fully functional, the seed coat turns brown faster. So the slow-darkening

pintos have this gene, and it is functional, but there is one mismatch in the gene sequence that gives the protein reduced function,” Dhaubhadel explains. Reduced protein activity means less proanthocyanidin is produced in the seed coat.

Now that they’ve discovered the gene, Dhaubhadel and Islam are attempting to learn how it works in pinto beans versus other beans with similar post-harvest seed coat darkening issues

– for example, cranberry beans.

What’s next? Dhaubhadel and Islam’s work identifying gene-specific markers in pinto bean means that breeding pinto beans with desirable agronomic traits and slow-darkening can happen much more quickly.

It was a complicated study, according to Dhaubhadel, which wouldn’t have been successful without her lab’s collaborations – and the work of Islam. Sometimes, it takes a village to find a gene.

No matter how challenging your needs, BKT is always with you, offering a wide range of tires tailored to every need in agriculture: from work in the open field to the orchards and vineyards, from high power tractors to trailers for transport.

Reliable and safe, sturdy and durable, capable of combining traction and reduced soil compaction, comfort and high performance. BKT: always with you, to get the most out of your agricultural equipment.

This pest’s increasingly early arrival in Ontario plus its Bt resistance could be a double whammy for field crop growers.

by Carolyn King

Corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea) has the potential to become a serious pest in Ontario field crops. With milder winters, the moth is migrating earlier into Ontario, increasing its ability to impact field crops like corn and beans. At the same time, control options are limited because the incoming populations already have resistance to some Bt proteins and insecticides.

This insect has multiple generations each year in its traditional overwintering range in the southern United States and further to the south. The moths are carried north toward Canada by windy and stormy weather. However, the pest’s overwintering range has been gradually extending closer to Canada.

“Corn earworms used to overwinter just in southern states like Florida and maybe Georgia. But now they are likely overwintering close to Pennsylvania. So they can come to Ontario a lot earlier than they would have in the past,” explains Tracey Baute, field crop entomologist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

“Ten or even 20 years ago, we didn’t see flights of corn earworm moths into Ontario until about August, or sometimes late July if they were early. So they were a late-season pest, and their impact wasn’t as much of a concern in Ontario, especially for field crops,” she notes.

“However, in the last five or maybe even the last 10 years, that migration has been earlier.” In some years, earworms have been caught in Ontario as early as June. “With these earlier arrivals, there is potential for more fields to be attractive to the pest.”

She adds, “Corn earworms are not yet overwintering in Ontario because they are really sensitive to freezing temperatures. That said, climate models indicate that our winters may become more mild, and in about 20 years the pest could overwinter here.”

This pest has a broad host range that includes crops such as tomatoes, peppers, alfalfa and cotton, along with corn and beans. The larvae prefer to feed on the fruit or reproductive parts of the host plants.

“In corn, the moths lay individual eggs directly on the silks. The eggs are the same colour and diameter as the silks, so they are almost impossible to see. [After hatching, the larvae crawl down the silks to the ears, feeding on the silks and then the kernels, beginning at the tips of the ears.] The pest often goes unnoticed until

growers see the larval damage, for instance, when the silks are off the ear or the ear isn’t properly pollinated,” Baute says.

Corn is most attractive to egg-laying earworm moths when the crop is at the fresh silk stage. “In Ontario, earworms tend to go to sweet corn first, partly because of the timing of when the sweet corn tassels and silks come in. But earworms can also impact grain corn,” she says.

“So far, it looks like this pest has less of an association with ear moulds than western bean cutworm. But that may be because of the earworm’s timing at present; earworms may not be spending

as much time in the ears as western bean cutworms do currently.”

Baute notes, “In beans, the earworm tends to go to crops like snap beans, which may be a little later than the typical dry bean or soybean period here. Earworms are similar to western bean cutworms in that they mine into the bean pod and feed on the seeds inside, and their damage provides an entryway for pod diseases.”

If earworm continues coming into Ontario earlier and earlier, it could have greater impacts in field corn, and it might increasingly attack dry bean crops and even late-planted soybean fields.

If the need for managing this pest increases in the coming years, Ontario field crop growers will have to grapple with the limited options available for managing it.

“Down in Georgia, Texas and West Virginia, earworms are a pest in both cotton and corn. Both of those crops have Bt proteins. So that pest has not only been exposed to a lot of foliar insecticides but also to all three of the Bts that are used against it,” Baute explains.

As a result, earworm populations in the U.S. have developed resistance to two of those Bts: Cry1Ab and Cry1A.105+Cry2Ab2. The earworms migrating to Ontario originate from those populations. “Even though we really don’t target our Bt crops for earworm in Ontario, we know the earworms coming here are already able to overcome those same two Bt proteins, based on a few field issues here in 2018.”

Only Vip3A is still effective on corn earworm. “In the United

States, they are monitoring Vip3A to check that it is still working. However, because it is the only remaining Bt for controlling earworm and it is heavily used in both corn and cotton, there is a good chance that the pest will develop resistance to Vip3A too,” she says.

“So if earworm becomes more of a concern in our field crops, we may be looking at the type of control strategies they have to use in sweet corn, which is to spray more often. And that is also a problem because the insect has developed resistance to some of those sprays in the States.”

On the watch for earworm

Baute emphasizes that the threat of corn earworm should not be taken lightly. She points to the example of western bean cutworm, another pest that is now down to a single Bt protein (Vip3A) for its control, and which has quickly developed into a significant problem in Ontario beans and corn since the insect started expanding its range to the province.

“Corn earworm is something that we need to monitor for and really pay attention to. We need to know how early they are coming in, so we can determine if we are going to have to start managing the pest in some of our field crops,” Baute says.

That’s why corn earworm has been added to the Great Lakes and Maritimes Pest Monitoring Network. This network uses pheromone traps to track western bean cutworm, European corn borer, black cutworm, true armyworm and fall armyworm, as well as earworm. Crops currently being monitored by the network include field corn, sweet corn, dry beans and snap beans. The trap results are provided

online, using real-time, interactive maps and dashboards.

This network is a collaboration of provincial and state representatives from Michigan, Ohio, New York, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Baute notes, “The shared trapping with neighbouring jurisdictions helps give us a heads-up to know what’s going on.”

Of course, Baute and her colleagues also respond when growers or crop scouts report unexpected insect damage so they can check for issues like resistance to Bt proteins or insecticides, changing patterns in existing pest threats and emergence of new pests, and to provide management advice for dealing with such problems.

Another Helicoverpa on the way?

Corn earworm’s nasty cousin from the old world, Helicoverpa armigera, has recently come to the Americas. It can damage both the vegetative and reproductive stages of plants, it has a wider host range than corn earworm, it can develop pesticide resistance very quickly, and it can hybridize with corn earworm.

Helicoverpa armigera was first confirmed in Brazil in 2013. It has already spread to several other countries in South and Central America, and it seems to have the potential to spread further north.

“They have had detections of Helicoverpa armigera in Florida, and they are concerned about it in Texas and are monitoring for it. As long as we stay aware of those monitoring activities, that will help us know whether this insect could actually start to migrate this way or not,” Baute says.

“I’d be very surprised if Helicoverpa armigera could overwinter here. But who knows? Especially if it has a hybrid that has more cold tolerance and a greater ability to overwinter closer to Canada, that could be a game-changer.”

Planting host crops early will help make your fields less attractive

to corn earworms than nearby fields. “Plant as early as possible – without putting your crop at risk of another pest because you planted early. You’ve got to decide what is your primary pest issue and adjust accordingly,” Baute advises.

To watch for earworms in corn crops, it is best to rely on traps rather than trying to scout for the difficult-to-see eggs. “Many sweet corn growers already have their own traps for corn earworm because they time their sprays by those traps,” she notes.

“In field corn, growers will at least need to rely on our monitoring network, and in the future they may want to set up their own traps. They need to pay attention to when the earworm flights occur because that is really the only indication of whether the pest is around and whether it may need to be sprayed.”

If you find earworms (or western bean cutworms) in your Vip3A corn, contact your seed agronomist or Baute so they can confirm if resistance is present.

“When it comes to dry beans, snap beans and even soybeans, growers need to look for feeding injury by this pest and maybe start trapping to monitor for it,” Baute says.

“Earworms leave a hole in the pod as they enter to feed inside it. Because the larvae are less nocturnal than western bean larvae, you may actually find the earworm larvae inside the pod when you open it to investigate what is going on.”

She notes that spray timing can be tricky, especially in crops where only one application is economical. The insecticide needs to be applied before the larvae go into the ears or bean pods, where they are protected from the spray.

Baute concludes, “It will be interesting over the next 10 years to see whether corn earworm becomes more common in Ontario crops. Especially with climate change, the pest will be given more opportunity. Hopefully, we won’t lose the effectiveness of the Vip3A protein against it. If that happens, then we will have to turn to foliar insecticides, and no one wants to have to do that. But our monitoring network should give us a heads-up if we do have to manage earworm in our field crops.”

Proactive research is underway to counteract the threat from further spread of this canola pest.

by Carolyn King

Entomologist Christine Noronha first happened upon a pollen beetle infestation in P.E.I. canola fields in 2012.

“At that time, the growers here didn’t know the pest was in their crops. I was working on some other insects in canola and I found the beetles. So I went to other canola growers and visited their fields. The fields were just teeming with these beetles, but they are so small that nobody noticed them.”

Noronha, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Charlottetown, is leading a project to help ensure that other Canadian canola growers will be ready for this pest’s invasion.

The pollen beetle (Brassicogethes viridescens) is an introduced species from Europe, where it can cause serious yield losses. In Canada, the pest has become established in the Maritimes and Quebec. However, climate models show it could survive and even thrive in other canola-growing regions across the country.

The adult pollen beetle is about two- to 2.5-millimetres long and black with a metallic green tint. The adults emerge in early spring and feed on the pollen of many different plant species.

“Then as soon as canola gets to the stage where the buds are starting to form, the adult beetles move in to lay their eggs,” Noronha notes. The larvae can only survive on Brassicas, which include crops like canola, mustard and broccoli and weeds like stinkweed and shepherd’s purse.

“The adult beetles chew a hole in the newly-forming buds and lay their eggs inside the buds. The larvae have two instars, or growth stages. When the larvae first hatch, they feed on the pollen inside the bud. By the time the bud opens, the larvae are in their second instar. The second instars are a little more mobile and they move around to feed on the pollen in other flowers. The mature larvae fall to the ground and then pupate in the soil.” The adults emerge from the pupae a few weeks later. They feed on the pollen of various plant species and then overwinter in the soil.

Heavy infestations have the potential to severely impact canola yields. “The plant aborts the buds and flowers that have been damaged by the larvae. As a result, the crop has fewer flowers, fewer pods and fewer seeds, so the yield declines,” she explains.

“In the Maritimes, we have quite a few pollen beetles, but not a lot of canola is grown here, so the pest is not a huge issue,” she notes. “Although mustard is grown here, it is mainly a plough-down crop to control wireworms, and for plough-downs, seed yield is not important. Also, when you work the crop under, you’re probably killing the pollen beetle larvae, so you’re not really contributing to the build-up of the beetle’s population either.”

Other regions in Canada grow much more canola than the Maritimes. Based on Statistics Canada data over the past five years, the average area seeded to canola in Quebec is about 33,000 acres, and

in Ontario it is about 45,000 acres. In the Prairie provinces, around 21 million acres are seeded to canola annually.

“The whole premise of our pollen beetle project is to be proactive,” Noronha explains. “We want to create a bank of knowledge that we could use so we can hit the ground running when the beetles get to Western Canada, instead of trying to figure out what to do when they are already there and causing problems.”

This project, which is funded by the Canola Council of Canada, runs from 2018 to 2022. Most of the research is taking place in the Maritimes because the pollen beetles are there.

One of the project’s studies is evaluating the efficacy of various insecticides. “No insecticides are registered in Canada for controlling the pollen beetle, so at the moment growers don’t have a control option if the beetle becomes a serious problem,” Noronha says.

“However, using insecticides to manage the pollen beetle is kind of tricky because the pest is in the crop during flowering, and of course that is when bees are also there. We know that the insecticides that are very toxic to bees would control the beetle, but we don’t want to use them. Instead, we are looking at insecticides that are non-toxic or moderately toxic to bees to see which ones are most effective at controlling the pest.”

For this initial work, Noronha and her research group are conducting the evaluations in the lab. “Once we get a good idea of how all the different insecticides work in the lab, then we’ll try them in the field to see if they give the same kind of efficacy.”

Noronha’s group had to pause the lab trials in 2020 due to COVID restrictions, but they plan to test additional insecticides in 2021-22.

“We have already tested a few products. Most of them are giving good control in the lab,” she says. “I’ve got a number of other products in mind for testing, such as insecticides with a shorter half-life that would be less of a problem for bees. We also want to look at factors like application timing; we would like to apply the insecticide before the flowers open to minimize bee exposure.”

The project also includes a field study to determine economic thresholds for controlling the pollen beetle in canola. The study’s preliminary results suggest that a density of nine beetles per plant re-

sults in significant decreases in seed weight and the number of pods.

Noronha and her research group are continuing this threshold study in 2021-22. “Once we know what the threshold is above which you are going to have a reduction in your yield, canola growers can use this as a decision-making tool.”

Another component of the project involves developing a pollen beetle lab colony that Noronha can use for things like testing control measures. Since the eggs, larvae and beetles are all quite small, they are somewhat difficult to work with, but the main challenge is to stop the adults from remaining in a dormant, overwintering phase for many months.

To start the colony, Noronha and her group have brought the beetles into the lab and put them in cages with canola plants from the greenhouse. The researchers have had no trouble getting the beetle’s life cycle to go from egg-laying adults, to eggs, larvae, pupae and new adults. But they have determined that the new adults have an obligatory diapause – they must go into an overwintering phase from the fall until the spring.

“A lab colony is more useful if the insects just keep going from generation to generation. That way you constantly have a supply of insects for your trials. But in this case, we only have the insects in the growing season because after the summer they go into diapause.” She is hoping to find a way to break the beetle’s diapause cycle in the lab.

The project also includes a search for parasitic wasps native to the Maritimes that have adapted to attack pollen beetles. These tiny wasps lay their eggs inside the eggs or larvae of other insects. As the wasp larva grows, it feeds on the host insect’s larva, gradually killing it.

“These parasitoids are really neat because they can find their host’s eggs or larvae even when hidden inside a plant,” Noronha notes. These natural enemies could be very useful for attacking pollen beetle eggs or larvae inside the canola buds.

Looking for such parasitoids is fairly straightforward. “We take the pollen beetle larvae in from the field and keep them in the lab. When the larva becomes a pupa we look to see if a parasitoid emerges,” she explains.

Noronha and her group haven’t found any parasitoids in pollen beetle larvae so far. If they do find such a species, they can then look for a way to boost the parasitoid’s population so it could provide greater control of the pest.

A key component of the project is to monitor for the spread of the pollen beetle. “Detecting the pest early will allow us to take action faster to control it,” Noronha explains.

Her colleagues in Western Canada are conducting annual surveys for the pest in Prairie canola fields. John Gavloski, who is with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, is leading the Manitoba surveys. Tyler Wist at AAFC-Saskatoon leads the Saskatchewan surveys. And AAFC-Lethbridge’s Héctor Cárcamo leads the Alberta surveys.

Noronha says, “So far, we have not found pollen beetles in Western Canada, which is very good news.”

Although entomologists have looked for the pollen beetle in Ontario in recent years, the insect has not yet been reported in

the province. “Last year, my plan was to go to Ontario to survey for the beetle, but then COVID came along and stopped my plans,” Noronha notes. “I am still hoping to do that sometime in the future. This summer, I hope to be able to collaborate with some people in Ontario who could conduct sweeps in different Brassica crops to see if the pest is there.”

If funding is available for pollen beetle research after 2022, Noronha has several ideas for further studies. For example, she would like to conduct field trials with the more promising insecticides identified through her lab trials.

And perhaps the trial data might spark the interest of some insecticide companies in pursuing registration of their products for pollen beetle control in Canada.

Noronha would also like to experiment with some integrated pest management options. For instance, she would like to try using an early-planted trap strip of a Brassica crop to attract the beetles to that strip first. That strip could be sprayed to control the pest, rather than spraying the entire field.

She also would like to continue surveying for the beetle in Ontario and Western Canada to provide an early warning system for growers. And she would like to continue watching for pollen beetle parasitoids in the Maritimes and also in Quebec. A study conducted several years ago didn’t find any parasitoids in Quebec, but she thinks it’s time for another look. “I am sure that some insect species will adapt to become a natural enemy of the pollen beetle at some point.”

To improve her pollen beetle colony, Noronha wants to figure out a way to trick the beetle into coming out of diapause early or perhaps avoiding it completely. “For some insect species, you can break the diapause by exposing the insect to different temperature regimes or light cycles. But other species must overwinter for a set period of time. We want to play around a little more with trying to break the pollen beetle’s diapause; we’d be able to do many more trials if we could rear the colony year-round.”

Noronha concludes, “This beetle is a fairly new pest for Canada and we’re really just starting the research, but I think we’re on the right track to developing results that will benefit the growers.”

All bugs are bad? Not when you get to know them. Western bean cutworms, for example, cause major quality and yield damage in corn. Ladybird beetles feed on cutworm eggs and larvae. Because Coragen insecticide knows the difference, it protects your corn from Wester n bean cutworm at all life stages and leaves helpful beneficials alone. Group 28 Coragen insecticide has excellent tank-mixability, can be applied any time during the day and gives you 7 to 21 days of extended control. Think of it as nature and science working together.

Production

New technologies offer a way forward.

by Julienne Isaacs

We believe that the agriculture industry in North America will take the first steps towards a dramatic change of direction during the next decade.”

So write University of Guelph Plant Agriculture professor Mary Ruth McDonald and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist Bruce Gossen in a new publication.

The paper, which was published in the Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology , looks at how new technologies could enhance natural control of insect pests and disease management and reduce reliance on synthetic pesticides.

It argues that a shift to larger farms and bigger equipment has led to a reduction in genetic diversity in the field and contributed to reduced efficacy of pesticides and the “erosion” of cultivar resistance to diseases.

But technological advances in both equipment and plant breeding will help the agriculture industry return to a model that allows for greater biological diversity and thus improved

natural pest and disease control in the field, McDonald says.

As fields get bigger, bigger equipment is required, and human labour becomes more expensive, McDonald notes. “But if you have solar-powered, autonomous equipment and robotics, they can work day and night and the efficiencies are totally different – you’re not trying to make the human labour as efficient as possible,” she explains.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that, with the adoption of robotics, farms will become smaller.

“In an ideal situation, you could still manage a 10,000-acre farm with a swarm of robots, small seeders, sprayers or harvesters. They’d [perform tasks] at the optimal soil moisture for seeding, the optimal maturity for harvest,” she says. “The big

ABOVE: Technological advances have changed the way pests and diseases are controlled in fields, with less reliance on human labour.

thing is being able to seed and harvest different crops in the same field. You get back to more of the biodiversity and all of those advantages of intercropping or strip cropping and crop rotation.”

Robotics in agriculture can perform a range of services, from pest identification and management to weeding, aerating and harvesting; these products will first become common in high-value cash crops, vineyards and fruit production, before they become widely used in field crop production, McDonald says. For instance, drones can be used to spot-spray fungicides in vineyards on hillsides where it is difficult to use groundbased sprayers.

Autonomous farm equipment is not just a fantasy: at least one company already sells machinery like this in Canada, while most major farm implement manufacturers, including John Deere, Case IH and New Holland, have developed autonomous tractors in the U.S.

The shift to smaller, modular equipment will be driven by economics, McDonald and Gossen write in the paper. Autonomous equipment can work night and day and require input from the producer only if problems arise.

“Small, interchangeable pieces of equipment have the (as yet untapped) potential to be more cost effective and environmentally friendly than today’s juggernauts,” they write.

McDonald believes such advances will naturally fine-tune the way land is managed. For example, today’s massive sprayers have difficulty avoiding low spots, which smaller equipment has no problem navigating around.

Precision farming is already changing for the better with advancements in yield monitor technology: yield monitors can tell farmers which parts of a field are not productive enough to bother seeding, and these areas can either be reverted to a natural state or put to other uses.

“I remember at a fruit and vegetable conference a couple of years ago, a young farmer was saying he was working with a precision farming company and doing grid soil testing and realized that a 10-acre plot of land wasn’t going to be productive for vegetables or standard grain crops, but they figured out it would be good for fruit trees,” she says.

“He’s been proactive at making sure he can farm ecologically while still making a living.”

Plant breeding and the way forward

Advances in new technology are not confined to equipment.

In the paper, McDonald and Gossen point to developments in disease detection, weather forecasting and modeling, and plant breeding.

The latter has become immeasurably more efficient with

the introduction of genetic marker-assisted selection, which has also made trait stacking possible. Gene editing using CRISPR technology and RNA interference (gene silencing) are two technologies that have been deployed in recent years to help combat specific pest pressures. And DNA sequencing can help identify pest pressures to better fight them.

None of these technologies is a “silver bullet,” and resistance to them can still develop in pest populations. But they can help plant breeders bake greater levels of complexity into their breeding programs.

The main thrust of McDonald’s research over the years has been integrated pest management (IPM). Over the past 20 years, she says pesticides have become less toxic and more specific, which is better for the environment, but means it’s easier for pests and diseases to become resistant to their modes of action.

“Then we get onto this pesticide treadmill, where we have a really effective material that’s pretty safe to use but five years later it’s not effective anymore because our target pests have developed resistance. So that’s where we come back to the need for the original approaches to pest management,” she says. “If we don’t reduce the use of these products they just won’t work anymore. The industry is very good at coming out with new materials but they can’t keep up.”

The industry will need to rely on a combination of approaches, including improved genetics and targeted chemistries, while always leaning toward increasing genetic diversity in the field.

The point of this research, she says, is not to lecture farmers, many of whom are implementing new technologies as soon as they become available. Rather, it’s to give a sense of the directions farming is headed over the coming decades.

“It doesn’t have to go in the direction of ‘bigger is better,’” McDonald says. “The technology is out there and we’re starting to ask how self-driving technology can be used to address other questions: What part of the farm should be farmed? Can I diversify the crops in the field?

“I have huge respect for farmers because they’re balancing so many things with their decisions every day and every year. They’re the ones who are trying to integrate all this information in terms of what it means. And they’re at the mercy of the weather,” she says.

Broflanilide is set to provide improved wireworm control, but a greater understanding of the pest is still necessary.

by Alex Barnard

Wireworms are a particularly pesky pest on the Prairies. While there are chemical control options that prevent wireworms from feeding on a crop or paralyze them, there hasn’t been a pesticide capable of killing them since the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) cancelled registration of lindane in late 2004.

With the PMRA’s registration in November 2020 of broflanilide, the first Group 30 insecticide on the market, that’s set to change.

“What’s been missing for a number of years in crop protection is a registered pesticide that will kill wireworms,” says Haley Catton, research scientist and entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “In recent years, the ones that have been registered in cereals, pulses and even potatoes have been effective at protecting crops through paralyzing the wireworms or repelling them – pushing them away in the soil. But they haven’t been reducing wireworm populations enough to provide multi-year control.

“So that means those same wireworms, because they live for multiple years, are there in your soil just waiting for next year’s crop. That would mean a producer would require consistent applications every year, even while the wireworm populations build up and build up because there’s nothing killing them.”

Applying pesticide for use in this manner isn’t uncommon, but it is costly, especially if the return on that investment is small. But Catton notes that, through conversations with colleagues who have yet unpublished research on broflanilide’s effects, it has huge potential for within season and multi-year wireworm control.

“There’s only one published study on broflanilide and wireworms so far, because it’s a pretty new chemical. That study described field trials in B.C. and showed that [broflanilide] protected wheat stand similarly to other chemicals, but also reduced wireworm populations, which was unique among the registered chemicals tested,” she explains. The current market formulation of the other new formulation recently registered for wireworm, a diamide, was not included in that study. “So, if a chemical can reduce your wireworm populations, that means maybe you don’t need to apply it next year as well – you’re knocking back the number of wireworms.”

While it’s early days yet, broflanilide shows promise as a replacement for lindane.

“The published study showed that [broflanilide] was killing 70 per cent of the wireworms in the treated plots. That was a seed treatment on wheat, but 70 per cent is a really nice knock-back number. That’s very similar to what we would see with lindane back when it

was still registered,” Catton says.

“The potential is huge. Wireworm has been such a huge problem in different regions of the country. Eastern Canada – P.E.I., Nova Scotia, New Brunswick –have had such a huge, huge problem with wireworms; a tool that could knock back populations and protect crops could be a game-changer.”

Big picture problems

A big problem in wireworm control is a lack of research and information on the pest.

“On the Prairies, the species of pest wireworms are all native species,” Catton says. “But in the Maritime provinces and B.C., they have European invasive wire-

worm species; totally different genuses from the ones on the Prairies. In some ways that’s good, because they can benefit from European research that’s been going on. But, in other ways, invasive species are hard to manage.”

“We don’t really have a good way of monitoring wireworms reliably and we also don’t have economic thresholds. It’s a very complicated problem to try to solve,” she adds.

“The only really reliable control we have for crop protection are chemicals at the moment, but we’re hoping as research goes forward to have new tools available.”

Catton notes that there is a great deal of research and work being done on wire-

worms in Canada at the moment. She was part of a team analyzing the pheromones produced by females of certain species of the beetle stage of wireworms, which attract male beetles for mating.

“One thing people have done for European wireworm species is synthesize those pheromones so we can put them in traps and have a bunch of beetles come to those traps – so you can easily monitor what species are around and how many,” Catton explains. “There’s been major advancements in that on the Prairies; I’m part of a team where we isolated new pheromones for two new species – those tools weren’t available before.”

She notes that the complexity of wireworms as a pest means more research is necessary. While some fields may be devastated by wireworms, other growers might not have ever experienced any damage and believe the threat wireworms pose is overblown.

“In terms of the research, it needs to

keep going because [wireworm is] a patchy pest that’s made up of multiple species,” she says. “That makes it very different from a pest like wheat midge or wheat stem sawfly or something that’s just one species. We’re talking about multiple species with different life cycles, different behaviours, different feeding behaviours; some of them need to mate, some of them don’t.”

“There’s no black and white with wireworms, unfortunately,” Catton says. “The whole thing is complex.”

On the topic of pesticides more broadly, Catton hopes to shift perceptions of when to use them.

“One way to think about chemicals is insurance,” she says. “You could say, ‘I’m not sure what’s going to happen, so I will invest in this treatment to prevent it from happening.’ But there are hidden costs with that: not only the cost of the chemi-

cal in the application, but also any of the non-target effects to beneficial insects that might be controlling some other pests you have in your field.”

“An insurance salesperson might say, ‘Better safe than sorry,’ but as entomologists we’re trying to shift that perception: yes, there is something to lose by applying when you don’t need to.”

Catton likens entomological research on pest insects to laparoscopic surgery. “I think a more historic mentality would have been, ‘Let’s sterilize this field, let’s kill everything in that field.’ But we know from research how important those other insects in the agro-ecosystem are. They eat weed seeds, they eat pests – they eat and they poop, so they’re cycling nutrients,” she says.

“We want to be surgical – how can we get in there and reduce the populations of the ones we don’t want, and leave everything else we do want. That’s the future for insect pest control.”

Insights to help position your farm for success

Annex Business Media’s agricultural publications are hosting four free, live webinars with industry experts discussing key topics in farm financial management.

Part 1: Business Risk Management

P a r t 1 : B u s i n e s s R i s k M a n a ge m e n t

– A fact- based review and analysi s

March 25 - 1pm MT/ 3pm ET

Part 2: Transitioning Your Farm

P a r t 2 : T ra n s i t i o n i n g Yo u r Fa r m

- Opening the door to your transitio n

April 15 - 1pm MT/ 3pm ET

Part 3: Using Data in Ag

P a r t 3 : Us i n g D a t a i n A g for f inancial mana gemen t

May 19 - 1pm MT/3pm E T

P a r t 4 : U t i l i z i n g B e n c h m a rk I n for to Focus Your Farm Op eration

Part 4: Utilizing Benchmark Information

June 10 - 1pm MT/ 3pm ET

SCAN QR CODE with phone camera or visit link below to register today for the series! A reminder email will be sent to you for each webinar.

Most people seek help when they need it.

shouldn’t be any different

It’s time to start changing the way we talk about farmers and farming. To recognize that just like anyone else, sometimes we might need a little help dealing with issues like stress, anxiety, and depression. That’s why the Do More Agriculture Foundation is here, ready to provide access to mental health resources like counselling, training and education, tailored specifically to the needs of Canadian farmers and their families.