TOP CROP MANAGER

Soybean vein necroSiS

Answering questions about this new disease

PG. 5

northern corn Leaf bLight

New varieties to combat a fungal threat

PG. 12 c ano L a Seeking

Su L phur

Addressing suspicions and targeting yields

PG. 22

Answering questions about this new disease

PG. 5

northern corn Leaf bLight

New varieties to combat a fungal threat

PG. 12 c ano L a Seeking

Su L phur

Addressing suspicions and targeting yields

PG. 22

MANA Canada HerbicidesSame active as Phantom™ (Imazethapyr)

Arrow® (Clethodim)

Bison® (Tralkoxydim)

Badge®II (Bromoxynil & mCPA Ester)

Thrasher®II (Bromoxynil & 2,4-D Ester)

m

Bromotril®II (Bromoxynil) Pardner®

Bengal® WB (Fenoxaprop-p-ethyl) Puma® Super

Diurex® (Diuron) Karmex®

MANA Canada Insecticides Same active as Silencer® (Lambda-cyhalothrin)

Pyrinex® (Chlorpyrifos)

Alias® (Imidacloprid) Admire® and Stress Shield® Apollo® (Clofentezine)

MANA Canada FungicidesSame active as Bumper® (Propiconazole) Tilt®

Blanket AP™ (Azoxystrobin & Propiconazole)

Mission® (Propiconazole)

Folpan® (Folpet)

(Iprodione)

At MANA Canada we believe that growers and retailers deserve choice in crop protection products. Our growing portfolio of strategic active ingredients is used in over 20 MANA Canada branded herbicides, fungicides and insecticides manufactured to the highest standards.

For the best return on investment, choose the MANA Canada advantage.

flowers, bees can also deliver effective crop protection products.

Stefanie Croley | aSSoCiate eDitor

All signs are pointing to spring, and, I can’t help but associate this time of year with new growth.

Mother nature seemed to be especially fickle this winter. Just as temperatures began to rise and we prepared to say goodbye to the cold in mid-March, Southern ontario was hit with another blast of cold and even more snow. But there’s hope that the next few months will return to what we can only call normal, just in time for planting season. no doubt ontarians will welcome a sunny respite after a frigidly cold winter, but unfortunately, growth isn’t always positive, especially when dealing with plant diseases.

Spring’s forecast may provide ideal conditions for certain diseases to thrive, making the timing of this edition of Top Crop Manager, focusing on plant diseases, perfect. Farmer’s almanac is predicting that april and May will be slightly warmer and rainier than normal, and this summer will see higher-than-average temperatures.

This could be good news for soybean growers who are concerned about soybean vein necrosis this year. The University of guelph pest Diagnostic Clinic first found soybean vein necrosis virus (SVnV) in Kent and elgin Counties in 2012. It was first identified in Tennessee in 2008 and has been reported in 16 other states, making it the most widespread soybean virus in the United States. This new disease thrives in a hot, dry spring, according to Dr. Ioannis Tzanetakis, a plant virologist at the University of arkansas. His studies, outlined in our cover story on page 5, focus on the transmission of the disease and its effects on soybeans.

Dr. albert Tenuta is monitoring the disease in ontario, and says accurate identification is key for ontario growers. and, although soybean vein necrosis may not pose a serious threat this year, the spring and summer forecast, combined with the right pathological and host factors, may provide the perfect conditions for other diseases to thrive. Turn to page 18 for a roundup of other plant diseases to watch for in 2014, and get familiar with the symptoms so you can catch a potential problem before it’s too far gone.

If there’s a positive side to disease threats, it’s that researchers are continually working to learn more about disease pathogens and mitigate risks to growers. researchers like Barry Saville of Trent University in peterborough, ont., and Tom graefenhan, with the Canadian grain Commission in Winnipeg, are working on next-generation genome sequencing. Their studies are essential to learning more about pathogens that pose a threat to crops – as Tenuta says, understanding the pathogen’s genetic make up will allow for better protection against them. You can read more about the works of Saville and graefenhan on page 16.

We may not be able to control the weather, but we can control other factors that pose a risk to crops. With continuing research and proactive awareness, the threat of crop diseases will eventually become less daunting. Here’s to warm thoughts and ideal conditions for the coming season.

N3Y 4N5 e-mail:

in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES Top Crop Manager West - 9 issues - February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada - 4 issues - Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter 1 Year - $16 CDN plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry-

by Carolyn King

There’s some good news on the disease front for o ntario soybean growers. Based on findings so far, soybean vein necrosis appears to pose a relatively low economic risk in the province at present. But understanding of this recently discovered viral disease is still quite limited. So plant pathologists are seeking answers to important questions about the disease, its management and its longerterm implications.

Soybean vein necrosis is a leaf disease in soybeans. Typically the symptoms start as yellowish patches along the leaf’s main veins. The patches spread along the main veins and sometimes between the veins, and become reddish brown areas of necrotic (dead) tissue. Infected veins may be clear, yellow or dark brown, and vein discoloration may be more noticeable on the underside of the leaf.

Dr. Ioannis Tzanetakis, a plant virologist at the University of arkansas, first identified the disease in 2008. “I was new in arkansas, and I was looking to see what soybean viruses were found in the state. I collected samples of plants with virus-like symptoms, and I was seeing the symptoms [of what is now called

soybean vein necrosis disease]. I tested the samples, but none of those plants were infected by any of the 14 viruses that I was testing for,” says Tzanetakis.

“at almost the same time, Dr. John rupe was visiting Tennessee, and he brought back some samples with exactly the same symptoms. He told me they had tested the samples in Tennessee for 18 viruses and they couldn’t find any that were associated with those symptoms. So I looked at the possibility of a new virus.”

By sequencing its genome, Tzanetakis determined that the virus belongs to group of viruses called tospoviruses. Some viruses in this genus, such as tomato spotted wilt virus, can cause devastating losses in their crop hosts.

Tzanetakis developed a test to detect the new virus. Then he and his lab examined soybean leaf samples with and without the vein necrosis symptoms. They confirmed that the symptoms were always associated with the new virus. He says, “We collected more than 700 isolates of the virus from 11 states, and every single sample that had the soybean vein necrosis symptoms was infected with the virus [and none of the symptomless samples had the virus].”

a s of november 2013, the soybean vein necrosis virus (SV n V) had been detected in soybean crops in 16 U.S. states – in the south, the Midwest and the g reat Lakes states – and in o ntario. Tzanetakis says, “It is now considered the most widespread soybean virus in the United States.”

Since the 2008 discovery, Tzanetakis and his collaborators have been carrying out various studies to learn more about SV n V, its transmission and its impacts on soybeans.

Tospoviruses are vectored (transmitted) by tiny, winged insects called thrips. Knowing which particular thrips species – among the thousands of them – are SV n V vectors could help in managing the disease. Since the virus’s genome has some unusual characteristics compared to the other tospoviruses, Tzanetakis thought it might be vectored by a thrips species that was different from those known to vector other tospoviruses.

So he and his p hD student, Jing Zhou, looked into soybean thrips as a possible SV n V vector because neither soybean

thrips nor any of the other species in the same subfamily of thrips has ever before been proven to be a virus vector. Their study proved their hypothesis: soybean thrips is an SV n V vector.

Soybean thrips are common in soy-

bean fields. The insects acquire SV nV when feeding on an infected plant and then transmit it to other plants by feeding on them. The thrips feed mainly along the veins of the leaves, which is why the initial symptoms appear there.

GET

Stubborn weeds can threaten your corn crop. Fortunately, new DuPont™ Engarde™ corn herbicide delivers both knockdown and residual control of broadleaf weeds and grasses. Best of all, crop application timing is exible. Which means you can apply it all the way up to the two-leaf stage, ensuring those troublesome weeds stay at the no-leaf stage. Speak to your DuPont rep or retailer about new Engarde™ today. Questions? For more information, please contact your retailer, call your local DuPont rep or the DuPont™ FarmCare® Support Centre at 1-800-667-3925 or visit engarde.dupont.ca

Introducing EngardeTM: the early corn herbicide that delivers flexible, residual control of a broad weed spectrum, for the cleanest fields possible.

Planting is critical, harvest is make-or-break, but for many corn growers, a crop’s rst few weeks bring their fair share of grey hairs. A er all, growers know that early-season weed competition goes a long way to determining a crop’s yield potential.

At one time, growers might have dared to hope that the arrival of herbicide-tolerant corn would make everything easy. It hasn’t quite worked that way. In Ontario, for example, glyphosate resistance has been associated with three weed species: giant ragweed, Canada eabane and common ragweed.

Today, growers want new and better ways to control weeds early in the game, to give their corn the best possible shot at top yields.

at’s why the recent launch of DuPont™ Engarde™ herbicide is such big news. Engarde™, available across Ontario and Quebec in 2014, delivers exible, residual control of a broad spectrum of weeds. e result: a better defense against tough grass and broadleaf weeds and new options to get a cleaner eld.

“Engarde™ brings something genuinely new to the corn herbicide market,” says Dave Kloppenburg, Row Crop Manager with DuPont Crop Protection. “Growers want to eliminate early-season weed competition, but they’re also concerned about weed resistance. Engarde gives you great control, plus e ective resistance management.”

As Kloppenburg explains, Engarde™ contains two modes-of-action, from Groups 2 and 27. ese deliver powerful action on weeds, from pre-emergence up to the 2-leaf stage of corn. It’s ideal for conventional, minimum or no-till corn production.

Engarde™ is particularly strong on broadleaf weeds, including common ragweed, lamb’s-quarters, redroot pigweed (including triazine-resistant

biotypes), velvetleaf and wild mustard. In terms of grassy weeds, Engarde™ is labeled for a wide spectrum of species including barnyard grass, fall panicum, green and yellow foxtail, old witch grass and crabgrass.

“Engarde™ will really shine in terms of controlling panicum grass species, including fall panicum and old witch grass,” says Kloppenburg. “We’re also conducting further trials in 2014 to con rm its e cacy on proso millet, a weed that’s a signi cant problem for many growers.”

In his view, Engarde™ provides twice the protection for your corn. It has two modes-of-action and delivers two kinds of activity, knockdown and residual, along with valuable exibility in timing your early-season weed control program.

What does Engarde™ bring to a corn grower’s early-season weed control toolkit? It’s a question DuPont has studied and tested extensively. Depending on weed spectrum and other factors, Kloppenburg believes you can approach it one of two ways.

Scenario 1. Spray Engarde™ alone as a set-up treatment to remove early-season weed competition. en, follow up later with an in-crop glyphosate application. is works especially well if you have a combination of annual and perennial weeds. In this case, the in-crop glyphosate-based treatment will be better timed to help remove perennials such as sow thistle. You win.

Scenario 2. If you have mainly annual weeds, simply tank-mix Engarde™ with a pre-emergence grass herbicide and apply that, up to the 2-leaf stage, as a one-pass weed control program. is way, you achieve singlepass control with up to four modes-of-action (Groups 2, 5, 15 and 27) working for you. You win again.

Says Kloppenburg: “Early-season weed control is a critical part of growing a high-yielding corn crop. With new Engarde™ herbicide, we’re giving you new and better ways to achieve cleaner elds and maximize the yield potential of your crop.”

It takes some time for the thrips to become infected and transmit the virus to new plants, and time for the visual symptoms to appear on the infected plants. In arkansas the symptoms of the disease start to appear in soybean crops in about early June. By using thrips inoculated with SV n V, the researchers have proven that the virus is definitely causing the disease.

The weather plays a big part in levels of the disease because the thrips population explodes in hot, dry conditions. “a hot, dry spring helps the soybean thrips to populate newly emerging soybean plants, and the newer the plant, the more the damage. When you have a hot, dry spring, the disease is everywhere. When you have a cool, wet spring, the disease is not a big problem,” says Tzanetakis.

disease was not a major problem.”

other SVnV studies are investigating such questions as whether other thrips species also transmit the virus, how soybean planting date relates to the effects of the thrips and the virus on plant growth, and how the virus impacts different soybean cultivars.

Tzanetakis is involved in studies to evaluate if and when it makes economic sense to use insecticides to control thrips as a way to manage SVnV. “Dr. Les Domier, a collaborator in the project, is studying how different cultivars react to the disease; some cultivars are hammered by the disease, while some others are tolerant,” Tzanetakis explains. “and we’re evaluating how economical it is to eliminate the disease by spraying for the thrips, or whether it’s more economical to just let it go and accept that you’ll have a certain loss.”

His research team is also testing various plant species to identify alternative hosts of SVnV. The virus is an obligate parasite, which means it must always have a host, including the times of year when no soybean plants are growing. So controlling SVnV’s weed hosts might help in controlling the virus.

He adds, “I was in a meeting in February 2013 with extension pathologists from all over the U.S. In 2012, it was dry and hot, so there weren’t really major issues with fungal diseases, but I was truly surprised that 12 out of the 14 people in that room mentioned that vein necrosis was the major [soybean] disease in their state. In 2013, the spring was cool and wet, and the

The researchers have already confirmed one weed host – morning glory, a common weed in many soybean-growing regions in the United States. and they will soon be publishing their results for several other weeds frequently found in soybean fields in the south-central U.S.

In another current project, Tzanetakis is exploring what happens when a soybean plant is infected with several viruses including SVnV. previous research on seed-borne viruses, such as soybean mosaic virus, has shown that when a plant is infected with multiple viruses, the whole plant can be killed. “Vein necrosis appears to be localized where the thrips feed. But if you have a second virus infecting that particular plant, it may be that the vein necrosis virus can get outside that restricted area and then potentially it could kill the whole plant,” he notes.

In ontario, soybean vein necrosis was first confirmed in 2012; at that time it was present in much of southwestern ontario.

“We had been seeing these odd symptoms in the field for a few years and had been trying to get an idea of what was causing them through discussions and sampling with colleagues in the U.S. midwest. Then soybean vein necrosis virus was confirmed as the causal agent of the symptoms,” says albert Tenuta, field crop plant pathologist with the ontario Ministry of agriculture and Food (oMaF).

He notes, “With the dry, hot conditions in 2012, the thrips populations in ontario were up. So we had greater spread of the virus from plant to plant. [With the cooler, moister conditions] in 2013, the disease was still present, but it was definitely less – you could find it in most soybean fields, but it was at trace levels.”

In ontario, symptoms of the disease tend to appear later in the growing season when the plants are more mature and better able to withstand the infection. This later onset may be because soybean thrips don’t overwinter in northern soybean-growing areas; they migrate into the area from further south.

“There is a build-up period in each growing season of both the thrips population and the virus within that population, and that takes time. In most cases, the worst-case scenario would be that we would see the symptoms showing up in about July,” explains Tenuta. in Ontario, symptoms of the disease tend to appear later in the growing season when the plants are more mature and better able to withstand the infection.

He adds, “a s well, the injury is often confined to the vein area and maybe some of the surrounding tissue along the veins. So soybean vein necrosis is not like some of the fungal leaf diseases, where the leaves’ photosynthetic capability is decreased so much that the plant’s ability to develop pods and seeds is impacted. and it’s not like some viral diseases, such as soybean mosaic virus or bean pod mottle virus, that impact seed quality and are definitely a concern, especially for food-grade soybean production.”

Compared to these other diseases, Tenuta believes the risk from soybean vein necrosis to o ntario soybean production, and northern soybean production in general, is relatively low at present. “We’re not seeing any significant economic injury from it,” says Tenuta. “The injuries to the leaves do not seem to be affecting soybean yields, seed quality or seed germination.”

g iven the low impact in o ntario, Tenuta does not recommend an insecticide application to control the thrips vector of SV n V.

For now, the key for o ntario growers is accurate identification of the disease to avoid unwarranted control measures. Soybean vein necrosis symptoms may be mistaken for other diseases, such as cercospora leaf blight and bacterial blight, and other problems, like herbicide injury. Fortunately, Tenuta and his american colleagues have produced a new soybean vein necrosis information sheet that includes tips for identifying the disease and differentiating it from other soybean leaf problems.

The only way to definitely confirm any viral infection is through laboratory testing. You can contact the University of

g uelph’s pest Diagnostic Clinic or private diagnostic labs for information on pricing and sampling procedures.

Tenuta and his american colleagues are continuing to monitor the disease and evaluate its risk to soybean production to determine the best course of action for dealing with it. and they’ll keep growers up to date as more is learned about soybean vein necrosis.

Tenuta adds, “and it’s not just soybean vein necrosis virus – one of our goals every year is to get better, more accurate and more up-to-date information on all crop diseases. There are always new diseases coming along, like soybean vein necrosis, and diseases that are already here that are changing, like soybean cyst nematode and northern leaf blight in corn. So it’s a never-ending battle to manage them in an economically and environmentally safe way.”

For more on pests and diseases, visit www.topcropmanager.com

• The AI3070 utilizes a unique, patent-pending design optimized specifically for fungicide application

• The 30° forward tilted spray penetrates dense crop canopies, while 70° backward tilted spray maximizes coverage of the seed head for excellent disease control

• Air induction technology produces larger droplets to reduce drift

“ The AI3070 increased overall deposit amounts and uniformity compared to the industry standard single and twin fan nozzles.”

New varieties being developed to help combat a serious fungal disease.

by Treena Hein

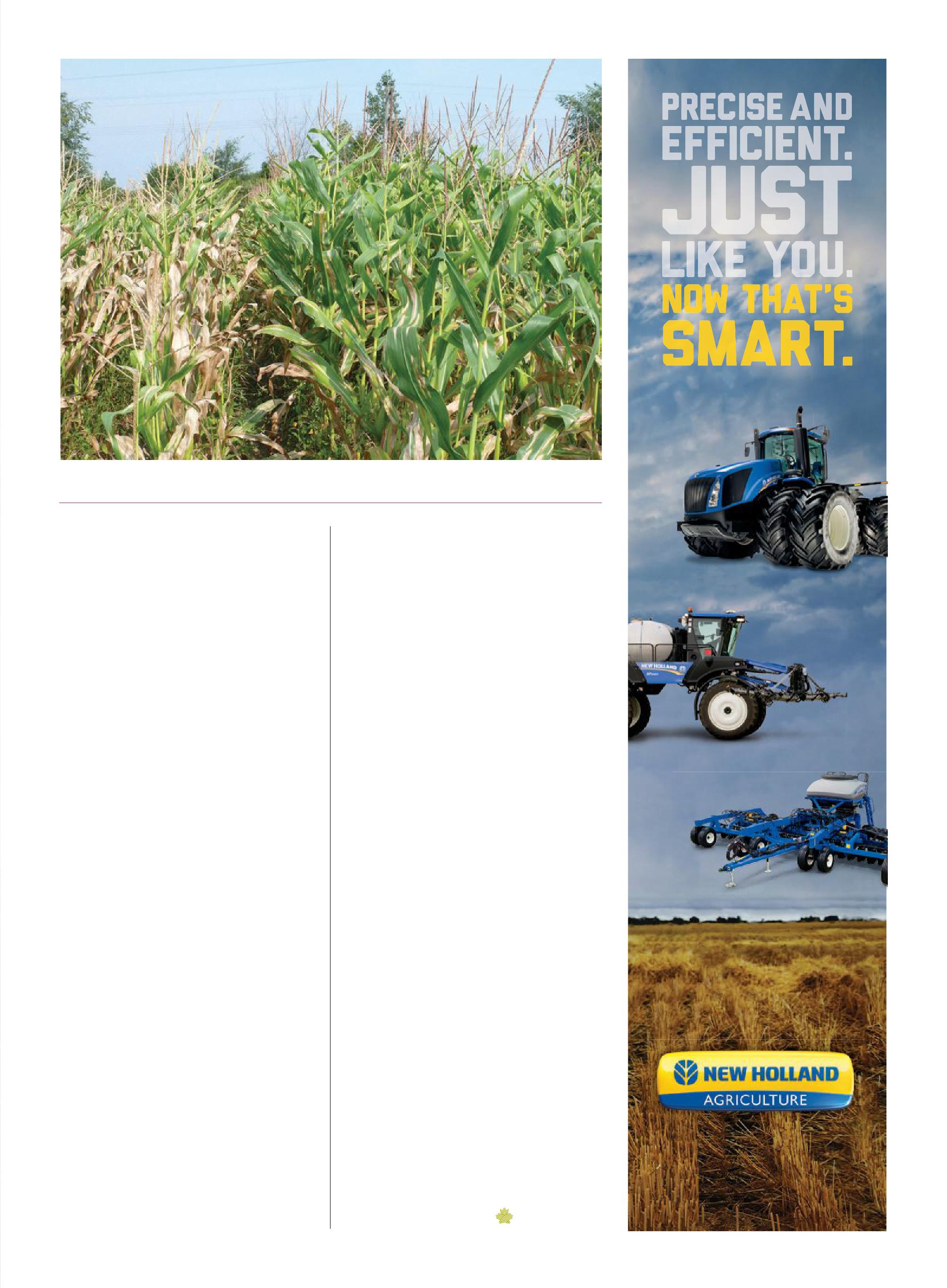

Like growers in other countries, Canadian crop farmers have faced a surge in northern corn leaf blight (nCLB) in the past seven to eight years. This blight is caused by Setosphaeria turcicum, and it’s the most common and economically important fungal leaf disease of corn.

“results of annual pest surveys of grain corn crops in the main corn growing regions of ontario have indicated that nCLB is becoming a serious problem – and yield losses are consistently increasing every year,” says albert Tenuta, field crop plant pathologist at the ontario Ministry of agriculture and Food.

Indeed, during the 2011, 2012 and 2013 crop seasons, the disease was observed in about 95 per cent of surveyed ontario fields. onset of nCLB before silking can cause grain yield losses of more than 50 per cent in very susceptible varieties. all of this means that the disease could continue to pose a significant risk to the grain corn industry for years to come.

The disease appears as long, elliptical, between two and 15 centimetres (one and six inches), greyish-green or tan streaks. Lesions

most often begin on the lower leaves. as the disease develops, individual lesions may join, forming large blighted areas. In some cases, entire leaves may become blighted or “burned” and nCLB is often confused with Stewart’s disease. Losses due to northern corn leaf blight are most severe when the leaves above the ear are infected at or before pollination. The fungus survives in corn residue as either spores or fungal strands (mycelium). The spores of the fungus are spread from the ground residue to the developing corn plant through wind or rain “splashing.” Infection occurs after a period of between six and 18 hours of leaf wetness, and therefore, disease development is favoured during prolonged periods of humidity or heavy dews when temperatures are moderate (18 C to 27 C). plants that become infected act as a secondary source of infection and may spread to other plants or fields.

aBOVE: Greyish-green or tan streaks, between two and 15 centimetres long, are a sign of Northern corn leaf blight.

It’s the biggest news in fungicides since the development of fungicides.

We couldn’t have created a fungicide this advanced without attracting the attention of the industry’s top scienti c minds—growers like you. Priaxor® is a new multiple mode of action product that combines the proven bene ts of Headline® fungicide with Xemium®. This new active ingredient contains unique mobility characteristics, resulting in more consistent and continuous disease control. And since it’s built on the foundation of Headline, you can expect to prosper from the bene ts* of AgCelence®—greener leaves, stronger stalks and stems—all leading to higher yield potential**. Learn more by visiting agsolutions.ca/priaxor or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

*AgCelence bene ts refer to products that contain the active ingredient pyraclostrobin. **All comparisons are to untreated, unless otherwise stated. Always read and follow label directions. AgSolutions, and HEADLINE are registered trade-marks of BASF Corporation; and AgCelence, XEMIUM and

The past and today northern corn leaf blight first appeared repeatedly in different parts of the world in the early 1900s and caused huge losses, until a positive development occurred. In the 1960s, a single dominant gene called Ht1 was discovered and incorporated into hybrids. However, the resistance conferred by this gene didn’t last long, and the disease began its global rise again.

“The recent surge in incidence is thought to perhaps be due to the emergence of new races of the fungus,” Tenuta notes. “Thirteen physiological races of the fungus have been identified thus far, and some are more aggressive than others. However, little information was available on the occurrence and distribution of the races in this province.”

Tenuta and his colleagues (corn breeder Dr. Lana reid and corn pathologist Xiaoyang Zhu, both located at the agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) eastern Cereals and oilseeds research Centre in ottawa), have performed a systematic identification of which nCLB races are present in ontario, a mapping of where they are located, and a study of how the major corn genotypes handle the disease, in terms of more or less resistance. This has enabled them to identify resistant genes against prevalent physiological races for incorporation in breeding programs. “The knowledge we are gaining will also eventually help corn growers to select and grow appropriate resistant hybrids in their specific areas,” Tenuta notes.

Two reports have been presented by the

scientists on the presence of different races of the fungus in ontario. one was based on the variable reaction of hybrids in the ontario Corn Committee performance Trials at different locations, and the presence of resistant and susceptible lesions on the same plants at aaFC’s nCLB resistant breeding nursery in ottawa. The other report outlines the interaction between different genotypes with various Ht resistance genes when exposed to spores collected from diseased leaf samples taken from different corn growing areas of ontario and Quebec.

reid and Zhu have developed a series of inbred lines having different resistance gene combinations against nCLB from isolates collected from around ontario. reid says the next step, pending funding approval, will see these lines tested in a greenhouse setting, as well as more molecular work being conducted to identify resistance genes.

When asked what growers can do to control their risk and manage northern corn leaf blight, Tenuta says hybrid selection is critical. “However, if hybrid response is not as expected, this could indicate shifts in the spread of different races,” he says. “Fungicides are useful, but timing is very important. Scouting is important in noting if disease severity is increasing, and as a follow-up to fungicide application.”

Tenuta has noted variability in fungicide efficacy to the disease could indicate nCLB race tolerance to commercial fungicides, but this will have to be further investigated both in the lab and in the field.

Scientists are expanding their knowledge and working toward serious solutions.

by amy petherick

Researchers have been stumped by pathogens plaguing the agricultural community for years. They know these microbes are out there, see the effects causing farmers distress, and have helped develop products to help manage these effects. But they really haven’t understood what makes these organisms tick. now they’re getting closer.

next-generation genome sequencing has opened a window into the world of the very small, allowing scientists access to unfathomable amounts of information. More than they could process at first. new systems of data management are emerging however, and that’s helping. When Barry Saville, a professor and researcher at Trent University, started working in the field of molecular research, it took months just to discover small segments of D na code and even longer to understand what it meant. But using today’s technology is advancing his knowledge of field crop diseases – such as corn smut and wheat rusts – in an exponential way, which is changing the way he thinks about crop protection.

“Farmers have transgenics that they’re dealing with and they

know how these work,” says Saville. “If a plant can express a bacterial toxin like Bt, why not have it express something that can stop fungal growth?” he asks.

Fungal diseases are very familiar to Saville, who began working with corn smut after learning how easily manipulated the organism’s D na is. Corn smut is also a biotroph, which means it has to get its food from a plant by keeping that plant alive. “These disease-causing fungi produce proteins that go into the plant and reprogram plant cells so that the plant feeds the fungus,” Saville says. a s it happens, Saville believes he may now be able to identify some of the genetic codes that lead to the formation of these proteins. He is learning these codes can look the same in other biotrophs, such as wheat leaf rust and maybe

aBOVE: Dr. Barry saville is a researcher and professor at Trent university studying the genetic make up of field crop pathogens. He hopes to prove RNa interference could one day offer farmers new methods of genetic disease resistance by working with the corn smut pathogen in a greenhouse environment.

even U g 99, which has him excited about developing new kinds of genetic disease resistance.

“There is a system in the cells of humans, plants and fungi that shut down genes that might be viruses or other bad things, called rna interference,” says Saville. “The idea is to use this system in the fungi against the fungi. For example, we could alter plants using a disarmed virus so they produce an rna taken up by the fungus, for example wheat leaf rust, or wheat stem rust, or U g 99, and that rna would stop the growth of the fungus.” Saville goes on to explain that now that researchers know the codes for the fungal proteins that alter the plants, these codes can be the targets of this approach, when these genes are turned on, they will produce a molecule that is like one half of a zipper and the rna introduced will be the other half of the zipper. When the zipper is closed, the resulting molecule is destroyed by the fungus’ own defence systems and the gene is shut down stopping the fungus’s ability to feed on the plant. “The virus is on a suicide mission,” Saville says. “The fungus takes it up and that rna blocks the ability of the fungus to continue infecting.”

Saville has only recently begun toying with the idea of testing the method on corn smut in a greenhouse environment and any practical application is years into the future. But he says the basic research of confirming the identity and function of these vectors is what makes future applications possible.

Tom g raefenhan is a research scientist with the Canadian g rain Commission (C g C) in Winnipeg, Man., who also studies pathogens using next generation technology. But g raefenhan’s interest is potential impact to end-use quality and market access of Canadian grains, not just agronomy applications. Since the C g C provides foreign buyers with letters of assurance guaranteeing shipments are free of potentially harmful microorganisms regulated in their country, g raefenhan has to be well aware of all the fungi, yeasts and bacteria which culture on seed. In cereals, this includes 100,000 to one million colonyforming units representing hundreds of different species per gram of seed.

“every single seed is a microcosm for these organisms; it’s their planet,” he says. “ numbers of colony-forming units depend a lot on the environmental conditions a seed was grown in, and Canada tends to have more microbes compared to an australian climate which is very hot, very dry.”

Without the right tools, finding detrimental species in the microflora of any given wheat, rye or barley sample is very much like trying to find a needle in a haystack. even worse, g raefenhan says traditional monitoring methods required researchers to grow cultures on artificial media for identification and some fungi are so highly adapted to their hosts, they wouldn’t grow in the lab.

“We knew they were there but we couldn’t look at them,” he says. “With these D na methods, you can take the raw grain, wash the microbes off those seeds, and the D na technology gives us the ability to identify single molecules.”

In the same way fingerprints can identify an individual, little pieces of genetic code can tell g raefenhan what species of fungi were living in a seed sample. More importantly however, these codes also can tell him what the fungi was likely doing on that seed and if it would impact end use grain products (such as in sourdough fermentation or barley malting).

“These are things you cannot tell just by looking at the fungus through a microscope,” he says. “It may take us decades to decode the genomes of all these microorganisms, but once we have this information, then we can look for all kinds of characteristics, good and bad.”

albert Tenuta, field crop plant pathologist with the o ntario Ministry of a griculture and Food, says knowing more about pathogens is a necessary step in defending against them in the future, because it’s only getting harder to protect our food sources from them.

“Knowing what is out there can allow us to better target our genetic breeding efforts to anticipate those changes,” says Tenuta. “If we have a good understanding of a pathogen’s genetic make up, that can allow us to test germplasms to best protect against them.” Studies have been published for two decades describing which varieties hold up best against pathogens of all sorts, both in the field and through a variety of food processing methods, but explanations of these observances have been limited, to the dismay of few. a s long as the result was consistent, answering “How?” hasn’t always been a priority. But Tenuta warns that these days may be over as pathogens evolve.

“With leaf rusts for instance, we often see resistance only last two or three years in the field because the pathogen has adapted to bypass the resistance breeders have developed,” he says. “We’ve done a wonderful job both from a breeding aspect and a management aspect, in reducing our risk over time, but things always change and knowing what is coming in the future is important in terms of planning our defences.”

by Melanie epp

While there’s no way of knowing for sure what the 2014 growing season will bring in terms of plant disease, there are ways to prepare. predictably, some diseases will crop up every year, says albert Tenuta, pathologist field crops program lead at the University of guelph’s ridgetown Campus. others, though, will only surface when conditions are just right – a perfect combination of pathogen, host and environment.

“every year is different environmentally,” says Tenuta. “Warm and dry, hot and wet, or vice versa. Individual field management – more residue, less residue, tillage, no tillage – all of those things are factors that contribute to or decrease the risk of many of these foliar leaf diseases.”

after a long and harsh winter, Tenuta says not to worry as much about the pathogens, like asian soybean rust, that overwinter in the deep south of the United States. Some, though, will thrive in an especially wet and warm spring. Here are seven diseases to watch out for this year – four in corn, and three in soybeans.

anthracnose leaf blight

often the first disease that corn farmers see in their fields, anthracnose can be severe, especially in warm, wet years. anthracnose can be especially severe in tillage systems where infected debris is left on the soil. Before moving its way up the plant, the disease is first noticeable on the plant’s lower leaves. once the plant hits the rapid growth stage, the symptoms often disappear entirely, only to return in the form of anthracnose stalk rot. For this reason, it is important to scout thoroughly and return to the sites where anthracnose is first detected.

The fungus that causes anthracnose overwinters in corn residue, which is why the disease can be especially bad in second-year corn crops. Managing for anthracnose starts with choosing a resistant hybrid. To lower disease risk in conventional tillage fields, it’s a good idea to remove corn residue. In minimum- or no-till situations, crop rotation is key.

“anthracnose is not one that we normally would recommend a fungicide for, particularly because of the timing of the disease,” says Tenuta. “an early application of a fungicide that early on – there’s really no justification. I can’t really see the economic return to the producer on that type of application.”

In recent years, eyespot has been increasing in ontario, particularly in high-residue fields and continuous corn systems. The disease prefers

cool, wet conditions, and does overwinter in corn residue. eyespot produces round or oval tan brown spots; lesions that can kill large portions of leaf tissue. To manage eyespot, choose resistant varieties, rotate crops and clear fields of crop debris.

eyespot is ubiquitous, says Tenuta. “It’s there in most fields and growers will see it. We really wouldn’t recommend a fungicide application strictly for eyespot.

“eyespot is a good example of why it’s important to be out in your fields, scouting, knowing and identifying the diseases,” he continues. “proper management requires proper identification or accurate identification.”

northern corn leaf blight is the most economically important leaf disease in corn in ontario. “In the province, anywhere we go, our surveys find that 95 per cent of the fields have some degree of northern leaf blight – ranging from trace to severe,” says Tenuta. “a lot of this is driven by hybrids, genetics and resistance or tolerance. northern leaf blight is a great example of a disease organism or pathogen that has multiple different races in existence in both ontario and globally.” In ontario, indications are new races are starting to develop, suggesting a decline in tolerance levels.

northern corn leaf blight prefers prolonged periods of humid or rainy weather. The disease appears as greyish-green streaks, which often begin on the plant’s lower leaves. When the leaves above the ear are infected, losses can be severe.

Tillage will reduce inoculum levels in surface residue, as will crop rotation. In reduced tillage systems, be sure to choose resistant hybrids. If the leaves above or below the ear leaf start seeing disease at tassling or earlier, says Tenuta, a fungicide application is probably warranted and in most cases will provide an economic return especially when corn prices are good.

Both destructive and economically important, grey leaf spot – the number one disease in corn in the mid-western United States – has been increasing in the area surrounding the great Lakes in the past 10 years. The disease prefers wet conditions, and is especially prevalent in high residue, continuous corn systems. The good news is many new corn hybrids with good tolerance to grey leaf spot are available. Spores that are produced are dispersed by both rain splash and wind.

“If you see it working its way up the plant or starting to challenge the two leaves below the ear, then that is definitely a concern and a

fungicide would be warranted for that,” says Tenuta.

Soybean cyst nematode is the most economically important disease in soybeans in ontario, says Tenuta, but it can be managed quite effectively. Soybean cyst nematodes are microscopic organisms that damage the plant’s root system, preventing it from taking in water and nutrients. More often than not, by the time symptoms are visible, significant yield has already been lost. In ontario, losses range between five and 100 per cent.

There are several steps farmers can take to reduce economic losses due to soybean cyst nematode. “It requires a commitment on the producer’s part in terms of growing resistant varieties, using crop rotation – corn, wheat, for instance, in the rotation – and also, it’s important to be scouting in terms of knowing your populations and getting a soil test done every four to six years, just to get an idea of what the populations are doing.”

Closely associated with soybean cyst nematode is sudden death syndrome (SDS) of soybean, says Tenuta. SDS likes cool, wet conditions early on in the season. “anything that inhibits root development will allow for the colonization of the roots,” says Tenuta, who suggests that producers plant later if those conditions are present. “one of the problems with sudden death syndrome is that management strategies are choosing more tolerant varieties, but we’re limited to the number of tolerant varieties available to us.” Seed treatments targeting the disease look very promising and hopefully will be available soon.

White mould ( Sclerotinia sclerotiorum ) is probably one of the most frustrating diseases out there because of its incredible sporadic nature, says Tenuta. It thrives in wet conditions, but will suddenly die off if the weather gets hot and dry.

There are some tolerant varieties available to producers, but Tenuta says that none of them offer true genetic resistance. He suggests choosing varieties that are resistant to lodging and have a more vertical architecture to them.

another management technique for white mould is to make the environment less favourable for the disease. “Some of the management practices for high yields are also ones that are increasing the risk of disease as well,” says Tenuta, who suggests planting wider rows, decreasing plant populations, and using longer rotations including wheat and corn.

There are different types of products available – biological, foliar and chemical, for example. application timing is important, says Tenuta. With foliar applications, for instance, fungicides should be applied in and around the r2 stage or even at almost full bloom. “We need to protect those flowers because that’s the infection source. once those flowers are infected, the disease can build from there,” says Tenuta. “If you wait too long, your fungicide is not going to be as affective on the white mould fungus.”

Frogeye leaf spot

Frogeye leaf spot is more prevalent in southwestern ontario, particularly in high-residue fields with shorter rotations. “It can cause significant economic injury if it occurs earlier on a susceptible variety,” says Tenuta. “But the real key with frogeye leaf spot is what we’re seeing in the changing of the pathogen.” It is particularly problematic in the United States, where strobilurin resistance is becoming an issue.

While we often think of these resistance cases as isolated and the result of management techniques, Tenuta says they’re actually the result of natural mutations in the genome of the pathogen. Mutant strains of this pathogen have been found from the gulf states to the mid-western United States.

“It’s an important reminder that these tools that we have available to us, whether it’s fungicides or germplasm, that things change and we always have to use them in the best possible way so we can maintain their longevity as a useful tool in our toolbox,” he concludes.

it’s a three-step process

1. Scout early and scout often.

2. practice management techniques that reduce the risks, including choosing disease-resistant varieties and practicing longer rotations. 3. If warranted, use a fungicide.

• Powerful & innovative disease protection • Best-in-class movement properties • Rapid uptake & flexible under a variety of conditions Diseases: White mould, Northern corn leaf blight & powdery mildew.

DuPontTM Acapela® is a high-performing broad-spectrum fungicide that puts you in control, delivering reliable and powerful protection under a variety of conditions.

Multiplediseasethreats? Acapela® works on many important diseases, including Sclerotinia white mould,* Septoria brown spot, frogeye leaf spot (Cercospera) and Northern corn leaf blight, for healthier crops and higher yield potential.

Inconsistentstaging? Acapela® features best-in-class movement properties for superior coverage. It travels across, into and around the leaf with strong preventative and residual activity.

Weatherthreatening? Spray away and count on Acapela® for excellent rainfastness if you need it.

DuPontTM Acapela® fungicide. It fits the way you farm.

Questions? Ask your retailer, call 1- 800-667-3925 or visit acapela.dupont.ca

A new

by amy petherick

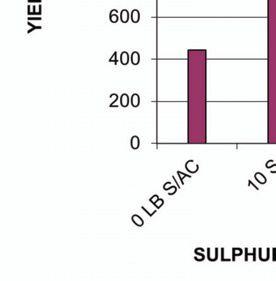

When the pocketbook wants what the pocketbook wants, sometimes the soil has to just give, give, give. Harmonizing the farm’s agronomy needs and finances may be an old game farmers play but in canola, sulphur keeps changing the rules.

Canola loves sulphur, and many ontario growers have been including sulphur as part of their standard fertilizer blends for years. Matched only by alfalfa in uptake, a canola crop can demand anywhere from 25 to 28 pounds per acre of sulphur annually. Interestingly enough, for years, a significant portion of sulphur was provided environmentally. Brian Hall, the edible bean and canola specialist for the ontario Ministry of agriculture and Food (oMaF), says less acid rain has been good for the environment in general and human health, but perhaps not so good for canola and growers.

“Back in the early ’90s, we were getting upwards of 20 pounds of sulphur deposited per acre annually, and now we’re below 10 pounds,” Hall explains. “over the last number of years, we find growers who have increasing sulphur deficiency in canola on sandy soils, dry areas and side slopes of fields.”

Though he isn’t exactly sure the changes in acid rain explain everything, Hall has worked with a number of co-operators, including Bonnie Ball, a soil fertility specialist with oMaF and Mra, and Jeff Holmes of Holmes agro, to respond to the emerging issue. results from a threeyear study, conducted by growers on their own farms in field-length replicated strips, were released last fall. The results demonstrated significant responses to sulphur application across most sites.

Last year, Hall’s team began to work on defining application rates of sulphur. He says in Western Canada, the recommended range lies between 15 and 20 pounds per acre. In ontario, however, some growers have insisted the rate needs to be closer to 40 pounds. While excessive most years, the growers’ perspective was that the money spent unnecessarily most years made up for the extra cost in highrisk years because the ability to correct a post-symptomatic sulphur deficiency is extremely limited – at least, until the cost of sulphur increased so much.

aBOVE: Canola has responded significantly to sulphur application on most sites in Brian Hall’s trials.

“We used to get very competitive sulphur, whereas now it just seems to get gobbled up so quickly . . . and they know now there’s a demand for it now,” notes Holmes, adding that arcelorMittal Dofasco, a steel company based in Hamilton, ont., used to sell ammonium sulphate as a byproduct. But that changed when anything tied to nitrogen started shooting up in value and the demand for sulphur in the phosphate fertilizer business increased too. The agronomist has been promoting a nitrogen:sulphur ratio program, according to soil type and test results, on high-end nitrogen-use crops because he’s found growers can save up to 10 per cent of their nitrogen with the right application of sulphur. Holmes thinks using different sulphur sources also helps, and he’s finding these economical contributions really come into play more than they used to.

“The concern I had was that [growers] were putting a pile of nitrogen on, and I think we’ve been wasting a lot of it,” he says. “all nitrogen is probably being applied more properly than it ever has been, making sure we get the best bang for it.”

Like nitrogen, sulphur is very mobile in the soil. It has a very weak holding capacity, maybe even worse than nitrogen, Holmes suggests. Ball, the field crops soil fertility specialist, explains this as a result of both being easily mineralized by organic matter; and in the same manner that nitrate testing can be tricky, soil testing for sulphur is as well.

“If the test is super high, it’s easy to know that there’s enough there, but when it gets down into the range where it may or may not respond, it takes a bit of interpretation,” says Ball. “It can depend on temperature, when you took the sample, and how deep you sampled.”

Currently, a sample depth of one foot is widely recommended, but Ball says going deeper by an extra foot offers additional information. In the spring, however, under the right circumstances, perhaps six inches would be deep enough. With inconsistency like this, both Ball and Hall are working towards alternative predictive tests for sulphur. Hall says he only has one year’s data so far, and he never puts much stock in results until they’ve tested true over multiple years. But, he notes, one alternative showing promise was plant tissue testing.

“Traditionally, the time for tissue testing was at early flower, [but] at that stage it’s not useful as a predictive tool for helping growers correct an issue,” Hall says.

July 9th , 2010

as of July 9, 2010, field trials were already demonstrating the combined effect of sulphur and nitrogen in canola. The left side of the field shown here only received 120 pounds of nitrogen with sulphur, while the right received 160 pounds of nitrogen without sulphur.

“Collecting whole plant samples at the rosette stage, we saw a pretty good indicator that perhaps plant tissue testing might be useful for predicting the need for sulphur.”

Ball says she also found this in established alfalfa crops where she took tissue samples at the late bud to early bloom stage, testing

the top six inches of at least 20 plants over the area in question. adding elemental sulphur in the fall not only increases crop sulphur content the following year, but also improves yields. She agrees with Hall that more testing is necessary to confirm some of their initial findings.

WHAT MATTERS MOST?

Family. When we’re all done we hope to work for our boys, so we’re putting resources into place for them now. Our Syngenta Rep is always there for us and treats our sons well. That trust and respect make all the difference. We know when our boys take over they’ll be in good hands.

Hugh Dietrich, 2nd generation farmer and owner, Hugh J Dietrich Farms Limited, Lucan, ON

While pollinating flowers, bees can also deliver effective crop protection products.

by Carolyn King

We all know that bees are great at carrying pollen from flower to flower. It turns out they are also great at carrying, or vectoring, microbial products from plant to plant to control crop diseases and insect pests. Based on years of innovative research and testing, bee-vectoring technology shows promise not only for Canadian greenhouse crops and fruit crops, but also for field crops like sunflowers and canola.

“With bee vectoring, there is a double benefit. Better pollination gives a crop yield boost. and then, with bees carrying biological control agents to the flowers, there is protection of the crop from fungal diseases or insect pests or both,” says Dr. peter Kevan from the University of guelph.

Kevan has been working on bee vectoring studies for more than 20 years, in collaboration with colleagues like Dr. John Sutton at the University of guelph and Dr. Les Shipp with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) at Harrow, ont., and

through partnering with beekeepers, crop growers, and various public and private sector agencies. Their research has received funding from the natural Sciences and engineering research Council of Canada, aaFC, the ontario Ministry of agriculture and Food, grower organizations, private companies, Seeds of Diversity and enviroquest Ltd.

over the years, the researchers have developed, tested and refined bee-vectoring systems for bumblebees and honeybees, including effective, bee-safe formulations of several different beneficial microbes and practical dispenser trays for the

TOP: as part of a bee vectoring trial, a four-pack of bumblebee boxes is placed on a pallet at the edge of a sunflower field in full bloom.

iNsET: inside the four-pack, each bumblebee box has its own tray of a powdered formulation of beneficial, bee-safe microbes. as they leave their home, the bees walk through the formulation and the powder sticks to their bodies.

formulations. and they have tested these systems in various crops against a number of important diseases and insect pests.

Kevan and Sutton first teamed up to work on bee vectoring in the early 1990s. “Initially we worked on strawberries and were successful in protecting strawberries against grey mould, and then protecting raspberries against grey mould, first using honeybees and then bumblebees as the vectors,” says Kevan.

grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) is a very common fungus on fruit. These early trials showed the microbial agent Clonostachys rosea worked as well as or better than a chemical fungicide application, and the berries had a longer shelf life. plus, the beevectored crops had the benefit of better pollination, resulting in bigger berries and higher yields. More recent field-scale trials in strawberries have shown the same microbial agent also effectively controls several other berry diseases.

“When John and I were pioneering bee vectoring in Canada, other people were doing similar work in other parts of the world. But the idea amongst many commercial people was that biological control didn’t work, which was a load of codswallop – there are lots of examples where biological control did work,” notes Kevan.

“But gradually things have changed, especially in the greenhouse industry. There is a lot of biological control that is commercially available to the greenhouse industry. So, when I started working with Les Shipp [in 2001], we moved very much into greenhouse uses of bee vectoring. We did some work on particularly tomatoes and peppers, and showed its efficacy against fungal diseases and insect pests.”

In greenhouses, bumblebees are generally used to pollinate tomatoes and often peppers, so it’s an easy step forward to also use the bees in suppressing diseases like grey mould and insect pests such as tarnished plant bug (lygus bug), western flower thrips, aphids and whitefly.

Kevan adds, “We are now on the verge of being commercial in the greenhouse industry. It’s not research grants supporting bee vectoring; we have forward-thinking clients who are buying the service from the commercial side.”

With this growing success in the greenhouse sector under their belts, Kevan and his colleagues are turning increasing attention to testing and refining bee vectoring for field crops in Canada, europe and the tropics.

Bee vectoring systems use trays with powdered formulations of one or more microbial agents. a tray is attached to a managed honeybee hive or bumblebee box at the place where the bees exit. The bees walk through the formulation each time they exit and the powder sticks to their bodies in the same way that pollen sticks them. as the bees move from plant to plant, they drop particles of the product onto flowers and leaves. When the bees return to their hive or box, they enter by a different route so they don’t bring the product into the hive.

either honeybee or bumblebee colonies can be used for bee vectoring, but bumblebees are easier. Kevan explains, “It’s mechanically a lot easier to work with bumblebees because the colonies are smaller, they have defined circular entrances and exits, and so on, rather than with a honeybee colony with 30,000 to 60,000 bees in it and a wide exit and entry space.”

So far in their bee vectoring systems, Kevan and his colleagues have been working with three common beneficial microbes:

The bees exit and, while pollinating the flowers, the bees deliver the formulation to control the crop’s diseases and/or insect pests.

Clonostachys rosea, Beauveria bassiana and Bacillus thuringiensis

“Clonostachys rosea is a ubiquitous soil fungus; it occurs everywhere you go in the world,” says Kevan. This fungus can control a number of important crop fungal diseases.

Beauveria bassiana, another common soil-borne fungus, is a parasite of many types of insects. “Beauveria bassiana is registered in many parts of the world for control of insect pests. all we’re doing is delivering it on the bodies of bees, rather than as a spray formulation,” notes Kevan.

“We have recently started to work with Bacillus thuringiensis, which is also registered in many parts of the world. Years ago, some bee vectoring tests in north Dakota used Bt against banded sunflower moths. Those tests were successful, but it never became a commercial use.” Bacillus thuringiensis, or Bt, is a naturally occurring bacterium; corn growers will recognize Bt as an insect control option in corn hybrids.

The economics of bee vectoring depend on such factors as the crop, the problem to be controlled, the grower’s practices, the location, and the costs for the bees and the microbial product.

When Kevan and his colleagues talk to farmers at bee vectoring workshops, they find a lot of interest in the technology, especially among organic farmers. “Bee vectoring isn’t per se designed as an organic farming technology, but everything we’re using can be certified organic,” he explains.

He adds, “It’s simple enough to fit into a conventional farming system as long as the farmer is aware not to spray when the crop is blooming. Insecticides should not be used at the same time as bees are around being used to vector the biocontrol agent [the bees will likely be harmed or killed], and use of chemical fungicides should be avoided because the biological control agents are living fungi.”

The researchers have conducted a number of field experiments in sunflowers and canola. For example, in 2011 and 2012 in ontario, they used bumblebees to deliver two microbial agents in sunflowers. Clonostachys rosea was used for control of

by M.

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, a very common crop pathogen, which causes sunflower head rot. and Beauveria bassiana was used simultaneously to control banded sunflower moth.

Those trials were very successful. Sclerotinia severity was reduced by 70 to 100 per cent in the bee-vectored fields. as well, other fungal diseases, such as Botrytis, Fusarium and Penicillium were also greatly reduced. Banded sunflower moth populations were below economic loss levels in treated fields. as well, the

bees’ pollination services were also very valuable – Kevan points out that, even though modern sunflower varieties can be self-pollinated, the seeds from crosspollinated plants are bigger and weigh more, have a higher oil content, and have much higher germination rates.

The combination of crop protection and better pollination in the bee-vectored sunflower fields resulted in an average yield boost of more than 20 per cent. The bee vectoring system also provided a four-fold return relative to the costs of

the bumblebee colonies and trays of the microbial powder.

In 2014, the researchers are hoping to do more sunflower trials in ontario and to start some in Manitoba.

In canola, their first field experiments were conducted back in 2002 and 2003. Dr. Mohammad al-Mazra’awi, a Jordanian national who was then a phD student at the University of guelph, used honeybees as vectors for Beauveria bassiana to control lygus bugs. He found that lygus bug mortality was about 50 per cent with bee vectoring compared to about 10 per cent without bee vectoring. But at about that time, the researchers started focusing more and more on the greenhouse industry, so their canola studies were put on hold.

now, the researchers are getting back into canola. In fact, they had a big field trial established in 2013, but a major hailstorm destroyed the crops and the hives, so they weren’t able to obtain any data.

“We would very much like to get co-operators who would like to test our technology with sclerotinia on canola; it is such an important canola disease,” notes Kevan.

He emphasizes that field-scale trials are crucial. “We have to show to the growers that, first of all, bee vectoring works at the field scale, and then, of course, it has to be shown to be economically feasible.”

even without the bee vectoring benefits, bee pollination could potentially boost canola yields. “Small experiments have been done all over the world – in Quebec, ontario, recently in southern Brazil, in europe, etc. – and they all have shown that, if honeybees are placed on canola fields, yield boosts are between 15 and 30 per cent,” notes Kevan.

another possible use of bee vectoring in canola would be in the production of hybrid canola seed. Hybrid seed production relies heavily on bees for pollen transfer between the parent plants, so bee vectoring would be an easy fit.

along with their plans for further work on sunflowers and canola, the researchers have a number of other bee vectoring projects in the works such as a pilot project with coffee crops in Brazil, greenhouse studies for controlling cabbage looper, a pilot project to manage fire blight on apples and pears in nova Scotia, and a study to quantify the increased shelf life and shipping life benefits for fruit.

A micronutrient study confirms importance of potassium in starter fertilizers.

by Blair andrews

Field research on starter fertilizers for corn in ontario continues to show that potassium deserves more respect as a crop nutrient.

greg Stewart, corn specialist with the ontario Ministry of agriculture and Food (oMaF), has led studies that have looked at a range of options for starter fertilizers, including products, placements and rates. Building on previous research that began in 2008, the most recent study evaluated corn yield response and economic returns to the application of sulphur and zinc to starter fertilizer blends.

“We were at a point where we tried to add something different to the study in the last two years,” says Stewart of the move to add the micronutrients to the starter fertilizer research in 2012 and 2013.

In the previous three years, the researchers discovered an intriguing situation on sites with soil that tested low for potassium. according to Stewart, the lack of potassium became a dominant factor in the study because the only starters that

showed positive yield responses were the ones that included K.

“It’s not unusual to find levels that have slipped down to this point where you would say nothing else really matters until you get that K corrected.”

The scenario played out again during the study in which sulphur and zinc were added. Stewart says it’s important to note they didn’t deliberately look for areas that were low in sulphur or zinc.

Starters were applied on six farmer sites where the core starter fertilizer blends were tested to investigate the relative importance of phosphorus, sulphur, zinc and potassium nutrition in dry starter fertilizer.

The other four sites were intensive sites, which investigated the contributions of the core starter blends as well as some other

aBOVE: a research planter is equipped with liquid and dry starter systems for accurate treatment and rate comparisons in OMaF’s recent study of starter fertilizers in corn.

Boundary herbicide’s reputation has always been solid. Now it’s liquid. You run a pristine operation and produce the highest-quality soybeans. You know residual annual grass and nightshade control is key to a great yield. And you know that time is money. So get the control and efficiency you want with easy-to-use emulsifiable concentrate Boundary ® LQD herbicide. It’s liquid at last.

dry/liquid fertilizers and alternative placement options towards increasing corn productivity.

across the intensive sites, significant starter fertilizer impacts were observed only at e lora, which had the lowest soil test levels for p and K.

at e lora, potash additions were the most important, but once K needs were looked after significant yield increases could be obtained from phosphorus, sulphur and zinc.

“The most exciting news at e lora (soil test p :9 and soil test K:46) is that you could move yields from 68 to 186 bu/ acre if you looked after all the fertilizer needs,” notes Stewart.

When the yields were averaged across all farmer sites, significant increases in corn yields were observed for all starter fertilizers.

The study notes that adding sulphur and zinc did not appear to produce yield responses greater than that of Map alone.

There was also a trend across these sites to have the starters with K be the highest yielding but it was not statistically significant.

o n farmer sites, the control averaged 157 bushels per acre. Map alone, produced an average of 172, similar to

yields with Map with sulphur and zinc. M ap, plus sulphur, zinc and potash produced 174 bushels per acre.

While the numbers are still being finalized for 2013, Stewart says there were solid results for applying a starter with nitrogen and phosphorus, particularly on the sites where the potassium was corrected.

There were few signs of a response from the micronutrients.

“I don’t know how to accurately identify those because we’re still struggling to come up with a solid soil test that would allow you to definitively say this is a site where I should add sulphur and zinc.”

o verall, he suggests the results appear to support the idea of addressing proper phosphorus and potassium nutrition in corn, particularly with low soil tests.

“We’re sort of left with some unexciting news that if you have a significant potash deficiency, that is absolutely the hammer that you must deal with before dealing with other starter fertilizer options, even if something as basic as n and p makes much sense to you,” adds Stewart.

While the results may appear to be lacklustre, Stewart believes they point to an intriguing idea for managing phosphorus and potassium. Instead

of using the traditional approach of broadcasting the nutrients together, he suggests there are good economical and environmental reasons to ask farmers to manage p and K separately.

“We’d really like to have producers try to focus on banding the p into the soil, close to the plant. and on potash, go in the other direction and broadcast it where you need it,” says Stewart, noting the potash is essentially benign to the environment. “So if you are going to try to do one blend of p and K for all of your operation and broadcast it all and cultivate it in or broadcast in the fall, it really becomes difficult to manage p and K in the best way for each element.”

While appreciating that broadcasting simplifies the process for most farmers who are already facing a number of management demands in their operations, Stewart says there also needs to be a balance of improving profitability and keeping an eye on the environment.

He says years of research have shown that the response from broadcasting phosphorus is quite poor while the numbers for broadcasting potash are solid when it is applied where it is required.

a s a starting point, he invites growers to seriously consider variable rates for potash.

“There is low hanging fruit in the site-specific world to apply potash where it needs it most,” says Stewart. “and I think the response to that will be much higher than trying to apply variable-rate phosphorus.”

Senior exeCUtive finanCial ConSUltant inveStorS GroUP finanCial ServiCeS inC. | PaUl r. vaillanCoUrt, CfP, ClU, CHS and CPCa

As an entrepreneur, operating your day-to-day farming business and planning for the future can consume a lot of your time. paying less tax, although important, may not always be top of mind.

There’s no time like the present to ensure you are taking full advantage of all the tax minimization strategies available to you. as you review these key tips, consider how you may be able to apply one or more to you and your business.

Whether you carry on your business personally or through a corporation, you should consider paying a salary to your spouse and/or children. Canada’s progressive tax system, which assesses higher income earners at higher tax rates, provides an incentive to split income with family members in a lower tax bracket. paying a salary to a spouse and/or child who pays tax at a lower rate than you can create net tax savings. But, you must ensure that the salary is reasonable for the services they perform for the business.

If your business produces more profit than you need to satisfy your personal cash flow needs, then incorporation could produce a sizeable tax deferral benefit, however, is only available if the profits are left in the company. The longer the profits are left in the company, the larger the tax advantage. It is important to note that investment income earned on prior deferrals and rental income do not receive this lower rate.

The tax deferral achieved through incorporation can create a permanent tax saving if the shares of the business are eventually sold and are eligible for the lifetime capital gains exemption. However, if you are incurring losses, this will not be the best option.

other potential advantages of incorporation include having family members own shares to have access to multiple capital gains exemptions, or paying out dividends to family members who are taxed at a lower rate. Your financial advisor can help determine which strategies work with your situation.

Since the biggest bang for your tax buck is accomplished by leaving profits in the company, the question becomes what to do with those profits. If paying down debt or reinvesting in the business operations are not options, then a smart investment plan is your best alternative. This strategy is most effective for active business income subject to the small business deduction. Your financial advisor can help you build the right investment portfolio for your business.

In order to make the maximum allowable registered retirement Savings plan (rrSp) contribution next year, you’ll need to create the contribution room this year by maximizing reported earned income. If incorporated, you will want to review the best dividend/ salary mix for your situation. as part of your overall plan, you may also want to make a contribution to your Tax-Free Savings account (TFSa). Talk to your financial advisor about achieving balance in your personal investment plan given all the variables and how it will fit with this year’s maximum contribution limits for business owners.

The tax deferral achieved through incorporation can create a permanent tax saving if the shares of the business are eventually sold.

Don’t forget to think about rrSp contribution room when setting and reporting remuneration for services provided by family members who also work in the business.

a corporation with taxable income over the small business limit may want to explore the use of an individual pension plan (Ipp). an Ipp is ideally suited to business owners in their midforties or older who have a past history of earning employment income from their company in excess of $100,000 per year. an Ipp will allow you to shelter even more earnings from tax than your rrSp while still offering some protection from creditors.

It’s never too early to plan your business exit strategy. If you’re planning on selling all or part of your business at some point, confirm with your accountant whether you’re eligible for the lifetime capital gain exemption and what steps need to be taken.

Unfortunately we can’t eliminate taxes. But we can use wise business practices to minimize or defer income taxes that would otherwise be payable. These are only a few of the tax-planning opportunities available to you as a business owner. Talk to your financial advisor about a complete tax check-up to help identify all the tax planning strategies available to you. after all, the tactics you employ today will help you reap rewards at tax time next year.

Trademarks, including Investors Group, are owned by IGM Financial Inc. and licensed to its subsidiary corporations. Written and published by Investors Group as a general source of information only. It is not intended as a solicitation to buy or sell specific investments, or to provide tax, legal or investment advice. Seek advice on your specific circumstances from an Investors Group Consultant.

Using legendary Quadrac® technology, the Case IH Steiger ® Rowtrac™ series tractors are agronomically designed to deliver maximum yield. Featuring four, independent oscillating tracks on an articulated frame, these tractors increase flotation while reducing compaction and ground pressure. The result is an optimized seedbed for ideal growing conditions and the ability to cover more ground in row crop applications.

Learn more about the power and productivity of Steiger Rowtrac tractors by visiting your dealer, or go to caseih.com/rowtrac

Because not everyone has one of these, there’s Quilt fungicide.

Quilt® puts added yield within reach. Applied with a conventional sprayer at the 5 to 8 leaf stage of corn, Quilt boosts yield without the need to wait for tassel. Field-scale trials in 2012 show a six bushel per acre yield benefit when Quilt is applied on corn early versus untreated. Two modes of action provide better resistance management and you can tank-mix with your in-crop herbicide application. With Quilt, the only thing that takes off is your corn.