HIGH VALUE TEAM-UP

Considerations for relay cropping winter canola and soybean in Ontario

PG. 12

THE ROOTS OF RESISTANCE

Are soybean aphids drawn to more nutritious soybean leaves?

PG. 8

Considerations for relay cropping winter canola and soybean in Ontario

PG. 12

Are soybean aphids drawn to more nutritious soybean leaves?

PG. 8

Developing feed, malt and food varieties for Eastern Canada

PG. 20

So much power. So little effort.

Just one 2-litre jug of highly concentrated Coragen® MaX insecticide gives you extended control of western bean cutworm, not to mention excellent tank-mixability and the ability to apply any time, day or night. The smaller jug means better handling, easier storage, and less plastic to recycle. Coragen® MaX insecticide lightens the load on bees and many important beneficials* too.

This season, leave the heavy lifting to Coragen® MaX insecticide.

8 | Getting to the roots of resistance

Are soybean aphids drawn to more nutritious soybean leaves?

By Julienne Isaacs

12 | Teaming up two high-value oilseed crops

Could winter canola and soybean be a successful pair for relay intercropping?

By Carolyn King

20 | Barley designed for Eastern Canada

Developing feed, malt and food varieties adapted to Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes.

By Carolyn King

By Julienne Isaacs PESTS AND DISEASES 18 Fighting plant disease from the inside By Julienne Isaacs

FCC REPORT SHOWS CANADIAN FARMLAND VALUE HIKE

According to Farm Credit Canada’s annual Farmland Values Report, the average value of cultivated Canadian farmland increased by 12.8 per cent in 2022 – the high est increase recorded since 2014. This increase occurred amid strong farm income, elevated input prices and rising interest rates.

ALEX BARNARD EDITOR

What makes a season successful in your mind?

Is it determined by getting your crops in – or off – the ground before a certain date? Is yield the all-important variable? What about trying a new practice or crop and having it work out?

Would you call something a success if it had no immediate or actionable benefit to your operation?

On page 8, Julienne Isaacs writes about research conducted at AAFC-London on metabolic resistance to soybean aphid feeding in soybean cultivars. The research generated evidence for a revised hypothesis, but not enough to draw definitive conclusions about the effects of improved soybean plant nutrition on soybean aphid resistance. And, because funding was no longer forthcoming for this particular project, the researchers were unable to conduct field tests that would validate (or not) their lab results.

So, with this context, let’s return to my initial question: Was this research project successful?

To my mind, it is. The researchers set out to learn more about soybean aphid resistance and they did. In the article, they discuss how they hope the groundwork they’ve laid will allow soybean breeders to develop more resistant cultivars in the future; the added benefits of this would be reduced need for insecticide applications and greater leeway for beneficial insects to manage the aphids on their own.

But an argument could be made that they weren’t able to answer the question with which they came to the project, nor are they in a position to continue their work and find those answers –largely due to circumstances beyond their control.

Circumstances beyond their control? Well, it’s not like farmers ever have to deal with that, eh?

Answers are hardly ever as simple and black-and-white as we might like, and results-centric thinking disregards a lot of wonderful things that might not be directly applicable. There’s almost always shades of grey, room for interpretation, or subjective biases at play. Though it would certainly be easier if there was a cut-and-dried method for measuring success, it would also be kind of boring. There’s a beauty in the uncertainty – which is handy, since uncertainty is pretty much the only guarantee in agriculture – and life.

As this is our last issue until the fall, I’ll take this opportunity to wish you all a successful 2023 growing season.

While most of you will have already started in some way, with warming temperatures (fingers crossed) comes a large part of the work.

So, may moisture levels and temperatures be within the desired ranges, and may pests and diseases leave your crops alone. Have a great season!

Potal

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

EDITOR

Alex Barnard • 519.429.5179 abarnard@annexbusinessmedia.com

NATIONAL ACCOUNT MANAGER Quinton Moorehead • 204.720.1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

plus tax

Crop Manager East – 4 issues Feb/Mar, Apr/May, Sep/Oct, Nov/Dec – 1 Year - $48.50 Cdn. / US $110.00 plus tax Potatoes in Canada – 1 issue Spring – 1 Year $17.50 Cdn. plus tax

in Canada – 2 issues Spring and Fall – 1 Year $17.50 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374 No part of the editorial content of this publication may be

without the publisher’s written permission © 2022

Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet

topcropmanager.com

With three active ingredients, and a track record of consistent performance, count on the superior, long-lasting protection of Miravis® Neo fungicide.

The lightning’s out of the bottle. Now fire up your sprayer and lay down the kind of disease control that powers crops towards their peak potential on every acre.

Experience the electrifying effect of Miravis® Neo in your fields this season!

To learn more about Miravis® Neo fungicide, visit Syngenta.ca/Miravis, contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or follow @SyngentaCanada on Twitter.

Looking at the feasibility of successfully producing this crop in eastern Ontario.

by Carolyn King

Over the past few years, agronomy studies and producer experiences have been filling some information gaps and fine-tuning best practices for winter canola in Ontario. Much of that effort is focused on southwestern Ontario.

But what about winter canola production in eastern Ontario?

Canola and edible bean specialist Meghan Moran decided to start looking into what it might take to successfully produce winter canola in this region. With funding from the Ontario Canola Growers Association, she launched a two-year study at the Ontario Crops Research Centre - Winchester in eastern Ontario.

Moran, who is with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), is collaborating on this project with Joshua Nasielski, an assistant professor at the University of Guelph. Moran is currently on parental leave, so for now the study is being guided by Nasielski and Ian De Schiffart, the University of Guelph agronomy technician at Winchester.

“The goal of the study is an initial look to see if winter canola will survive in eastern Ontario and what the yields might be,” says Nasielski, who heads the University of Guelph’s Northern and Eastern Ontario Agronomy Research Group.

Some eastern Ontario growers have tried winter canola, but it is not common in the region. “Part of what the Winchester research centre is there to do is to test new ideas and alternatives to see what happens and whether they are worth further exploration,” he says. The study also gives Nasielski and De Schiffart an opportunity to learn more about the ins and outs of winter canola production, a crop that is fairly new to both of them.

Nasielski notes that canola – whether it’s spring or winter canola

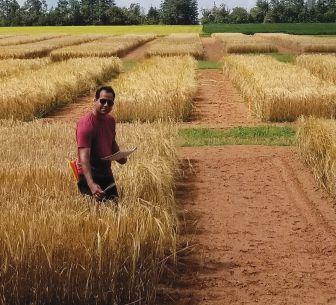

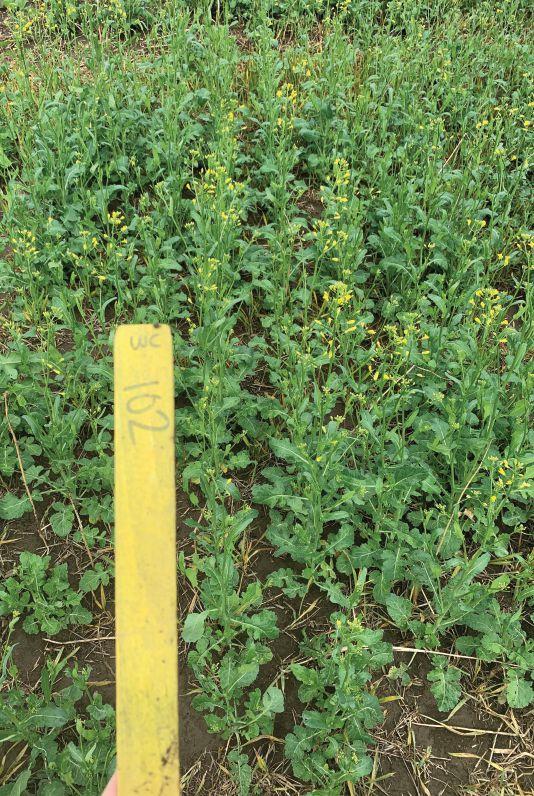

ABOVE: The Winchester plots provided a reminder that winter canola can bounce back from some overwintering stand reductions. In the spring when these photos were taken, plot 102 (planted Aug. 25) looked much better than plot 106 (planted Sept. 1), but their yields turned out to be pretty similar.

– has some potential benefits for eastern Ontario crop rotations.

For instance, growing canola could make winter wheat production more feasible. “Winter wheat is a challenging crop to fit into eastern Ontario rotations because of winterkill. However, it is much easier to get winter wheat planted early enough to survive the winter if you plant it after a spring canola or winter canola crop,” he says.

“Adding canola to a rotation would also have other benefits to the whole cropping system, like adding more diversity to the rotation and being able to change up your herbicides for resistance management.”

“We talk about a growing degree day requirement as a shorthand for how much thermal time – growing time – the crop needs before its growth shuts down for the winter.

Winter canola generally needs more growing time than winter wheat.”

He notes, “Compared to spring canola, the primary advantage of winter canola in eastern Ontario would be higher yields.”

Depending on the situation, winter canola may also have other possible advantages over spring canola. For instance, winter canola may have fewer problems with heat-stress damage to flowers and pods because it matures earlier in the season. It can also be more competitive against winter annual weeds and weeds that emerge in late spring. And it might reduce problems with certain insect pests, such as swede midge, because the plant has passed its vulnerable growth stage by the time the insect is at the right stage to attack.

The biggest risk for winter canola production is winterkill.

“To overwinter, winter canola needs enough time to build out its root system and build up its reserves of carbohydrates and nutrients to survive overwinter,” says Nasielski. For overwintering survival, OMAFRA recommends that a winter canola plant should have at least six leaves and a tap root that is at least the size of a pencil before winter sets in.

Research in southwestern Ontario by Eric Page with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada has shown that winter canola needs to accumulate more than 600 growing degree days (GDD, base zero degrees Celsius) between its planting date and the first killing frost for good winter survival and maximized yield potential.

“We talk about a growing degree day requirement as a shorthand for how much thermal time – growing time – the crop needs before its growth shuts down for the winter. Winter canola generally needs more growing time than winter wheat,” explains Nasielski. OMAFRA recommends planting winter canola about seven to 10 days earlier than winter wheat’s ideal planting date in a region.

He adds, “Farmers who grow winter wheat in eastern Ontario will do things like planting a slightly shorter maturity soybean so they can seed their winter wheat a little sooner. And they are very tactical about field selection, only growing the crop in fields with a history of good winter survival.” Similarly, he suggests that producers avoid planting winter canola in fields where winter wheat survival tends to be poor. OMAFRA recommends well-drained fields with low clay content for winter canola.

The study, which started in fall 2021, is assessing the effects of variety and planting date on winter survival and crop yields.

The fall 2021 planting dates compared in this study were: Aug.

25, Sept. 1 and Sept. 10. The 2022 dates were: Aug. 29, Sept. 6 and Sept. 12.

The winter canola varieties in the study are: Mercedes, a conventional hybrid and the only winter canola variety registered in Ontario; Inspiration, a conventional hybrid; and Plurax CL, a nongenetically modified Clearfield hybrid.

The plots were planted after winter wheat. That is a common rotational choice for Ontario winter canola growers mainly because of winter wheat’s relatively early harvest timing.

Before planting winter canola, the plots were sprayed with glyphosate to kill winter wheat volunteers and then tilled. No-till is not recommended for winter canola because crop residues increase the risk of serious slug damage to the young canola plants in the fall.

“For the first year of this project, we found we needed a planting date that would give the canola at least 700 GDD to have enough winter survival for a reasonable yield potential,” says Nasielski. “But this is just one year of data, so that’s very preliminary.”

In general, the yields were higher for the Aug. 25 plots than the Sept. 1 plots. None of the plots planted on Sept. 10 survived.

The plants in the Aug. 25 plots had five to seven leaves before the first killing frost, while the Sept. 1 plots had three to five leaves.

“Another thing to keep in mind with winter canola is how much of a stand do you need in the spring to actually have a high yield potential? It seems you can get quite a bit of stand loss and still have reasonable yields,” he notes.

“To those of us involved in the trial who didn’t have much experience with winter canola, some of the plots looked horrible after the winter. We’d look at a plot and think, ‘It’s a goner.’ But then it would bounce back and produce fairly good yields.”

Among the three hybrids, Mercedes had the highest average yields for both planting dates. For example, the average yields in pounds per acre for the Aug. 25 plots were: 2,988 for Mercedes; 2,863 for Inspiration; and 2,545 for Plurax CL. As a comparison, yield reports received by OMAFRA for Ontario winter canola harvested in summer 2022 were between 2,800 and 3,500 pounds per acre.

Once the results from the study’s second year are in, the findings should help to give a better idea of the feasibility of growing winter canola in eastern Ontario and help to provide better planting date information for the region.

by Julienne Isaacs

Soybean aphid is a perennial problem in Ontario fields. The pest can reach economic threshold levels in dry years, when already stressed soybean plants are vulnerable to insect pest pressure. 2021 was one such year.

The weather is not in producers’ control. But the genetics they choose can make a big difference.

Some cultivars are more resistant than others, and two Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researchers aim to know why.

Sangeeta Dhaubhadel and Ian Scott, both research scientists at AAFC’s London Research and Development Centre, co-led a study looking at metabolic resistance to soybean aphid feeding in soybean cultivars that was published in the journal Insects last year.

Dhaubhadel’s research in part looks at identifying factors that supply resistance against pests and pathogens; Scott, an entomologist, focuses on insect-plant interactions and host plant resistance.

In this study, they set out to look at the concentrations of isoflavonoids and other metabolites in the leaves of the soybean plants – resistant and susceptible – in order to help breeders zero in on particular cultivars that could be used to breed soybeans with improved resistance.

“Leaf metabolites are natural chemical compounds present in a plant, in the leaves,” explains Dhaubhadel. “Isoflavonoids are natural compounds with many biological roles, including protecting plants from pathogens. The type and amount of these varies, depending on genetic and environmental factors and the stresses [plants are] exposed to.”

Isoflavonoids can have a negative effect on insects – they act as a feeding deterrent.

Chinese research has found that isoflavonoids do supply resistance against aphids to soybean plants, she adds. But the research had to be confirmed with Canadian cultivars.

As a first step, Dhaubhadel and Scott did a survey of 18 commonly grown cultivars in Ontario. They then measured isoflavonoid levels in each of the 18 lines, at the V1 and V3 growth stages. The cultivars were classified as having high, moderate and low levels of isoflavonoids.

But the results did not show a straightforward link between high levels of isoflavonoids and improved resistance.

“What we observed when we compared the isoflavonoid leaf levels with resistance to aphids across those 18 soybean varieties was

Researchers looked at isoflavonoids concentrations in soybean plant leaves to see if cultivars could be bred with improved resistance.

that the isoflavonoids that we measured weren’t really providing us with a good biomarker for the aphid resistance. They weren’t explaining why certain varieties were more or less susceptible,” says Scott. “It wasn’t always a strong relationship.”

So, the researchers looked for relationships between other metabolites in the leaves and resistance to soybean aphid. They found a difference between levels of free amino acids in the leaves of the different cultivars, and there were lower levels of free amino acids in some of the most resistant varieties.

“This provided evidence that the nutrition of the plants was leading to the difference in aphid numbers. Higher leaf levels of specific free amino acids has been shown to lead to improved nutrition for aphids, which allowed for increased growth of the aphids and higher numbers,” explains Scott.

Does this mean that aphids are drawn to feed on plants that have an improved nutritional profile? Scott says that’s a hard question to answer – and to prove. But, he says, “Other researchers have found that there are links between the nutritional quality of the plants and the success of the insects on those plants in terms of their growth and survival.”

Aphids were hand-placed on the plants studied in the lab, so it’s difficult to make conclusive statements about how aphids would act in a field setting.

The experiment was done in a lab, and aphids were hand-placed on the plants that Scott and Dhaubhadel studied. That means it’s difficult to make conclusive statements about whether aphids would choose to feed on the same cultivars in a field setting.

More testing is needed, says Scott.

But two frontrunners did emerge from the group of 18 cultivars in terms of their resistance to soybean aphid: Harosoy 63 and OAC Avatar. Conversely, the cultivar Maple Arrow fared the worst of the group in terms of susceptibility. Pagoda and Conrad both showed more tolerance to aphid feeding damage.

Harosoy 63 is used mainly in lab settings as a control, says Dhaubhadel – it isn’t commonly planted. But OAC Avatar, a relatively new variety developed by University of Guelph research scientist Istvan Rajcan, is a top-yielding variety that is still grown in Ontario.

Dhaubhadel and Scott don’t currently have funding to continue the experiment with field tests. But their hope is that their groundwork can be used by soybean breeders to develop new cultivars with improved resistance. Improved genetics could mean a reduced need for insecticide applications and an improved environment for beneficial insects, like lady beetles, to control the pest naturally.

Great job recycling empty pesticide and fertilizer containers (jugs, drums and totes). Every one you recycle counts toward a more sustainable environment in your agricultural community. Thank you.

REMEMBER! You can also return empty seed, pesticide and inoculant bags* for environmentally safe management. Details at cleanfarms.ca

*In PEI, add empty fertilizer bags.

Tree-based intercropping offers Ontario and Quebec producers plenty of economic and ecological benefits.

by Julienne Isaacs

Tree-based intercropping is the practice of growing trees in rows between agricultural crops. It’s often called “alley cropping.” And though it isn’t common in Eastern Canada, one researcher believes it’s the way of the future.

“Tree-based intercropping systems are one of the most efficient and manageable nature-based solutions that farmers can do to meet climate goals, and there is high potential for every farm to integrate trees onto their farms,” says Raju Soolanayakanahally, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Trees are Soolanayakanahally’s specialty. His projects focus on aspects of agroforestry, including breeding climate-adaptive trees for carbon sequestration, riparian planting to intercept nutrient runoff, and shelterbelts.

He says trees that are integrated into agricultural land offer more than a few benefits for the whole ecosystem.

“When it comes to ecological benefits, they help with reducing soil erosion and wind speed on agricultural land. They develop a microclimate between rows that helps to improve soil fertility and serve as a host for natural pest predators and other beneficial insects. They also minimise nutrient leaching and stabilise riparian zones,” says Soolanayakanahally.

Early on, when trees are young, they can compete for nutrients with annual crops, but once they’ve matured (past five years or so) they can harvest water and nutrients from levels much deeper than crops. If deciduous trees are grown in the system, they add carbon and organic matter with leaf drop.

Fewer than 2,000 acres are currently used for tree-based inter-

cropping in Ontario and Quebec, he says. Only small landowners growing specialty or high-value crops like vegetables, garlic and ginseng are trying this land-use system. But there’s a lot of interest in the practice, says Soolanayakanahally: thousands of farmers have asked for more information.

And physically speaking, there’s plenty of room for far more tree-based intercropping in Eastern Canada.

A recent research paper – whose authorship includes other AAFC researchers, all of them specialists in a wide range of natural climate solutions (NCS) – looks at the potential for tree-based intercropping and other agroforestry practices on existing agricultural land across Canada. Soolanayakanahally, a co-author on the study, says the goal was to build models for 24 NCS to find ways for Canada to meet or even exceed its climate goals.

The researchers found that NCS, such as avoiding conversion of grassland, avoiding peatland disturbance, use of cover crops, and improved forest management, offer the largest greenhouse gas mitigation opportunities for Canada.

One of the NCS they examined was tree-based intercropping. In Ontario and Quebec alone, they found roughly 797,000 hectares (nearly 2 million acres) of class-three soils that could be used for tree-based intercropping systems. “In Ontario alone, there is potential for 2.16 Tg CO2e/year (teragrams of carbon dioxide equivalent per year) annual mitigation potential and in Quebec there’s

potential for 1.76 Tg CO2e/year ,” says Soolanayakanahally, a coauthor on the study.

Class-three soils have limited potential for high-value crop production but high potential for sequestering carbon above and belowground, he adds.

During the course of their research, the authors of this study came up with a list of tree species that perform best in terms of carbon sequestration and other criteria. Unsurprisingly, hybrid poplar tops the list: it’s fast-growing, sequesters carbon at a high rate and can be harvested by age 18, or up to age 25, in a treebased intercropping system.

“Then there’s red oak, a common native species for Ontario and Quebec,” says Soolanayakanahally. “Oak trees are slow-growing and can go up to 50 years, and they produce very high-value timber. When you integrate the trees at a rate of 111 trees per hectare, some of the trees supplant crops, but when you sell the timber at year 40, you’ll recoup that value, a net positive for the farmer.

“Then we have black walnut and Norway spruce. As far as economics goes, there’s no immediate return, but as the trees mature, there’s an economic benefit,” Soolanayakanahally says.

Forestry tree nurseries have the capacity to offer these tree species to farmers in the two provinces, he adds. Forest nurseries can source climate-resilient cuttings (hybrid poplar), acorns (red oak) and seed (black walnut and Norway spruce) from a large pool of trees to minimise negative impacts from diseases or pests.

Previously, Soolanayakanahally collaborated with Naresh Thevathasan at the University of Guelph on long-term tree-based intercropping research plots. Three years ago, the trees were cut down to make room for commercial development. But Soolanayakanahally thinks the data speaks for itself, and it won’t be long before producers catch on.

He adds, “This should be a research priority.”

With ADAMA’s full suite of fungicide innovations, you’ve always got the right tool for the job.

From cereals to canola and everything between, we provide Canadian growers with the ability to protect over 22 different crops from over 27 different diseases.

Could winter canola and soybean be a successful pair for relay intercropping?

by Carolyn King

Relay intercropping systems offer the possibility of multiple soil health and economic benefits – as well as multiple challenges in figuring out to optimize production of both crops. Some growers are trying winter cereal-soybean relay intercrops in southwestern Ontario. Now, a project is underway to see if winter canola-soybean relays could work in this region.

“Relay intercropping with winter canola has never been studied in Ontario before. So, in this project, we are starting with the basic agronomics to try and see what would make it successful,” explains Marinda DeGier, a University of Guelph master’s student who is conducting this project.

One of DeGier’s co-advisors is Eric Page, who is the project’s principal investigator and an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist at the Harrow Research and Development Centre. Her other co-advisor is Fran<6>ois Tardif, a professor in the University of Guelph’s department of plant agriculture.

Page’s research interests include winter canola as well as alternative cropping systems, like double cropping and relay intercropping. In double cropping, a winter annual crop is harvested, and then a summer crop is immediately planted for harvesting in that same growing season. In relay intercropping, the second crop of the relay is planted into the living first crop. The two crops grow alongside each other until the first crop is harvested. Then the second crop grows to maturity and is harvested.

“Growers are interested in growing winter canola [because it is a high-value crop with a high yield potential]. But they might be struggling with how to make it work in their rotations. Relay intercropping with soybeans might be a way to do that,” says DeGier.

“Down south [in places like Essex County], some growers might be double-cropping soybeans after winter canola. However, double cropping isn’t always possible in areas like Elora and Woodstock because of the shorter growing season. This project is working towards figuring out if relay intercropping would be possible in such areas.”

Relay pros and cons

Both relay intercropping and double cropping are strategies aimed at harvesting two crops in the same year, adding diversity into a crop rotation and providing a living soil cover during the fall, winter and early spring.

In terms of soil health, relay intercropping might be even more beneficial than double cropping. “A relay intercrop system provides year-round cover with continual living roots. Not many systems outside of a perennial crop can accomplish this,” notes Page.

He explains that the continual presence of living roots means continuity for the soil microbiome. It also contributes to greater scavenging of excess nutrients in the shoulder seasons and winter, which lowers the risk of nutrient leaching. As well, it reduces soil erosion risk.

Compared to single-crop systems, relay intercropping could enhance per acre productivity. Page explains, “It is assumed that neither crop in the relay will be as productive as the same species grown in a single-crop system. Rather, the potential for increased profitability lies in the ability to harvest two crops in one calendar year.”

Relay intercropping can also be a way to hedge your bets compared to a single-crop system. He says, “If one crop is less productive, the other can potentially make up for it.”

DeGier adds, “Water- and nutrient-uptake patterns for the two species in the intercrop will peak at different points during the growing season. This may be a pro or con depending on the season, but it spreads the risk.” Also, differences in root architecture between the two crops may mean that they take up nutrients and moisture from different parts of the soil profile.

Relay systems also allow planting of the second crop at about the same time as that crop would be planted in a single-crop system. That has advantages compared to the later planting date typically needed in a double-crop system.

For instance, in a relay intercrop where soybean is the second crop, the grower could use a longer season, higher yield-potential variety. DeGier gives another example: “In the spring, we typically have adequate moisture for seeding relay soybeans, whereas in mid-summer the top inch or two of the soil may be depleted of moisture, causing issues with the germination of double-crop soybeans.”

However, if the growing season is long enough to allow double cropping, then double cropping may be preferable to relay intercropping, notes Page. Although double cropping has to take into account some overlapping requirements of the two crops, such as herbicide sensitivities, it avoids the complications of managing the two crops simultaneously.

Those complications include the potential for mechanical damage to one crop or the

other during planting and harvesting operations, and the need to consider both crops at once regarding things like row spacing, herbicide sensitivities and fertility.

“Striking the balance between the needs of both crops in an intercrop is a challenge,” says Page. “It requires time, patience and experimentation by the farmer. Equipment availability and the capacity for spacing modification and control of seeding rates can limit implementation.”

According to Page, turning relay intercropping’s presumed benefits into actual benefits requires a long-term vision and commitment to the practice by the farmer.

DeGier’s project has two parts: a forward relay, and a reverse relay.

In the forward relay, winter canola is planted in late August/early September, and then soybeans are planted between the winter canola rows the following spring. The canola is harvested in July, and the soybeans are harvested in September/October.

In the reverse relay, the soybeans are planted in May. Then the winter canola is planted into the soybeans in late August/early September. The soybeans come off in late September/October, and then the winter canola is harvested in July of the following year.

DeGier points out that both relays have living crops in the field for longer than 12 months. Depending on the weather and the location, the forward relay’s complete cycle is around 13 months and the reverse relay’s is around 14 months.

The forward relay study is looking at two factors. One is winter canola seeding rates, with treatments comparing two-thirds of the recommended rate versus one-third. The other is spring nitrogen fertilizer rates for winter canola, with treatments comparing 50 per cent of the recommended rate versus no spring nitrogen fertilizer.

“By reducing the seeding rate and the nitrogen rate, we’re trying to manipulate the winter canola canopy to also allow for the success of the soybeans. If we had applied the standard seeding rate and the full amount of nitrogen, then the canola would likely choke out the soybeans,” explains DeGier. “We’re trying to find a balance in the relay intercrop system.”

The reverse relay study is comparing an early, middle and late planting date for winter canola. Within each of those planting dates is a comparison of drilling versus broadcasting of the canola seed.

The fieldwork, which started in September 2021, is taking place at four sites: Woodstock and Elora, managed by DeGier; and Harrow and Woodslee, managed by AAFC-Harrow staff.

The winter canola variety at all sites is a conventional hybrid called Mercedes – the only winter canola variety that is commercially available in Ontario at present. The soybean variety at each site is a herbicide-tolerant type with the appropriate maturity group (MG) for the growing area. Harrow and Woodslee are in the MG 3 zone, Woodstock is in the MG 1 zone, and Elora is in MG 0 zone.

Both winter canola and soybeans are planted on 30-inch row spacings, with the soybean rows and canola rows 15 inches from each other.

In the reverse relay, the soybeans are planted into tilled soil. In the forward relay, the winter canola is planted into tilled strips. “The benefit of strip tilling is that you have crop residue coverage between the canola rows, while being able to plant the canola into worked ground,” DeGier explains. It is important to plant winter

canola into tilled soil because the presence of crop residues can increase the risk of slug damage to canola seedlings.

According to DeGier, the project team has put a lot of thought into ensuring that equipment operations for one relay crop do not damage the other relay crop. For instance, at the Elora and Woodstock locations, in the forward relay, they have retrofitted a seed drill so they can plant the soybeans on 30-inch centres without running over the canola rosettes. And they use narrow-wheeled tires to move between the rows in both relay systems.

The team is monitoring two complete cycles of each relay system. They are collecting data on parameters like crop yields, stand counts, plant height and the amount of light that gets through the first crop’s canopy and down to the second crop, as well as watching for disease and weed problems. They will also be determining the production costs of the two relays, as compared to single-crop soybean production.

This project is a first step in seeing if winter canola-soybean relay intercrops could be a way to improve the sustainability and profitability of Ontario cropping systems.

“How do you know if something will be successful until you try it? That’s what I want to do in this project – to look at intercropping winter canola and soybeans and see if it is possible,” says DeGier.

The project is funded by the Ontario Canola Growers Association, Grain Farmers of Ontario, and Rubisco Seeds. People helping with this project include: Meghan Moran, Mike Cowbrough and Horst Bohner with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA); Josh Nasielski and Peter Smith with the University of Guelph; and Sydney Meloche and Alyssa Thibodeau with AAFC-Harrow.

by Julienne Isaacs

Move over, soybeans: there’s a new pulse in town.

Sweet white lupin is a highly nutritious, edible pulse crop more commonly grown in Europe that, thanks to new investment and research, may soon find a place in eastern Canadian rotations.

At Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Charlottetown Research and Development Centre, research scientist Aaron Mills is testing new varieties of Lupinus angustifolius (narrow-leafed sweet blue lupin), which is used for feed, and Lupinus albus (sweet white lupin), a food crop.

“At this point, we’re doing a variety evaluation and we’re using commercial field varieties as a benchmark,” says Mills. “We usually have half a dozen or maybe eight sweet white lupins and about six narrowleaf lupins that we’re [testing].”

Mills and his colleagues at the research centre had done some work with lupins six or seven years ago, trying to establish some basic agronomy and assessing whether lupins could be a good fit on the coast.

“We’re always looking for crops that could potentially fit here,” he says.

Last year, Mills was approached by Lupin Platform, an Albertabased company that is developing a closed-loop, vertically integrated lupin value chain in Western Canada, to conduct more targeted evaluations of improved varieties.

The Charlottetown trials are part of a three-year research project Lupin Platform is running across the country; similar trials are under-

way in B.C., Alberta and Ontario.

The company is in the seed multiplication stage for several highyielding European varieties and has already secured export markets for feed lupin, according to its website.

Mills says the crop isn’t grown at all yet in Eastern Canada. “We’re really in the developmental phase of this crop,” he says. “There was some work done in the 1980s, [but] there were issues with the crop reaching maturity. The climate has changed significantly since the 1980s, and the varieties have improved significantly, so we’re trying it again.”

So far, Mills says lupin appears to be a good fit for coastal conditions. The plants like cool weather and have performed well in welldrained soils.

Rotation-wise, sweet white lupin matures later than peas but before soybeans, meaning farmers have time to take it off. Lupin also comes off early enough for farmers to be able to seed a cover crop, and leaves residual nitrogen that the cover crop can use.

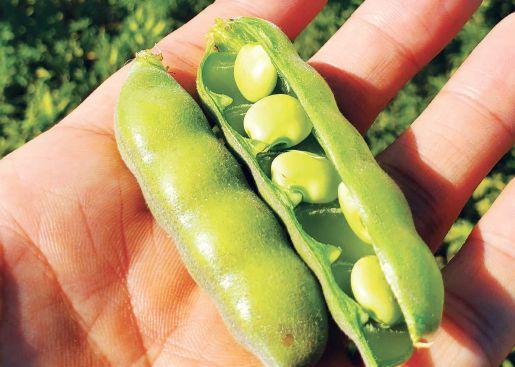

Sweet white lupin is cultivated across the Mediterranean region, as well as in eastern Europe, Africa and South America. Out of their pods, lupin seeds are large and creamy yellow in colour. In Greece, lupin seeds are eaten raw; in Egypt, they’re brined. In some places, they’re ground into flour and used as an additive to wheat flour.

Lupin could be considered a superfood due to its high protein and dietary fibre and low starch content, according to Lupin Platform, which also says the seeds contain three times more plant protein than quinoa, three times more fibre than oats and three times more iron than kale.

From an agronomic standpoint, the crop doesn’t present any unusual challenges. Mills says disease resistance has been an issue in the trials, but no more so than is typical under high moisture and high

humidity. Just as with any other crop on the East Coast, an aggressive fungicide regime will be necessary, he says.

“The ultimate challenge with any crop is finding a market, but it sounds like there are market opportunities for this as a plant-based protein source,” adds Mills. “Market access is a challenge with every crop, but I think there is potential. With soybeans, the oil content tends to be too high so they’re not as desirable as a protein source, but peas and lupin have lower oil content.”

Producers are interested in the crop, he says. “I’ve gotten calls from people who previously grew them and they told me what the issues were, and I reached out to some people who I knew had tried lupin from the 1980s, and they said maturity was the biggest problem they had with the crop. [But] I think we’ve got that sorted.

“If the company is able to provide seed and forward-contract what’s produced, I think it bodes well for the industry.”

Meet fungal endophytes – the newest biological control agent on the block.

by Julienne Isaacs

An endophyte is an organism – typically bacteria or fungi – that lives inside a plant for part of its life cycle. Every plant has microbial endophytes.

“The interactions between micro-organisms and host plants can be neutral, harmful or have beneficial effects on both organisms,” says Shawkat Ali, a research scientist based at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Kentville Research and Development Centre in Nova Scotia.

“Fungal endophytes… [don’t cause] any damage or disease symptoms in their host organism most of the time,” says Ali. In fact, he says, they’re often beneficial.

But what, exactly, do they do for plants?

In a recent review paper, Ali and his co-authors show that fungal endophytes can directly protect plants against pathogens. They can also help them indirectly, by making plants more resilient to pest damage, improving water and nutrient availability and remediating abiotic stresses, including drought, salinity, flooding and toxic chemicals in the environment.

“These endophytic micro-organisms provide protection against pests, insects, pathogens and predators through different mechanisms,” he says.

Ali’s research group is interested in how endophytes in healthy

plants can be harnessed to control harmful pathogens in lieu of chemical fungicides.

It’s an increasingly important avenue of investigation, he argues, in light of recent restrictions on chemical inputs in Canada and around the world.

In fact, some bacterial and fungal endophytes have been commercialized for use against crop pests in countries around the world, including the United States and Australia.

Last year, Corteva Agriscience announced an agreement with the microbiological company Symborg to distribute the latter’s endophytic bacterium Methylobacterium symbioticum product, which helps plants capture nitrogen from the atmosphere.

Trichoderma harzianum strain T-22, the active ingredient in Trianum WG biological fungicide and Trianum G biological fungicide, has been registered by Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) for the suppression of soil-borne pathogens that

ABOVE: Currently, Ali’s group is working on a couple of projects identifying and characterizing endophytes for deployment against plant pathogens – for example, in apple trees.

cause root diseases on greenhouse crops, field crops, greenhouse ornamentals and turf, says Ali.

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain F727 has also been registered by the PMRA for use in a variety of crops, including canola, sunflower and potatoes, to control or suppress various diseases. Another company, Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies, commercialized an endophytic fungi product called BioEnsure in 2017.

But endophytic products like these are not yet in common use in Canada.

How do “plant-friendly” endophytes work?

“Plant-friendly endophytes produce and secrete secondary metabolites/biochemicals that suppress/reduce the negative effects from plant pathogens, including volatile compounds that are able to suppress pathogen growth,” writes Ali in the publication.

Other endophytes protect the host plant by triggering plant defense mechanisms, he says, or by secreting antifungal or antibacterial compounds. Some even eat other fungi.

“Endophytes also directly compete with the host pathogens for space and nutrients,” Ali points out. Several endophytes also have plant growth-promoting properties that help the host plant get stronger.

Ali says endophytes can be added to “carrier materials,” such as vermiculite, expanded clay, sand and peat, used as a seed treatment, or even applied in-field as a spray.

“Endophytes that colonize the roots can be applied as spores for-

mulated in powder,” Ali adds. “They can also be applied as lyophilized [freeze-dried] spores or in liquid formulation, as seed covers or by dipping the seedling plant roots in an endophyte suspension before planting,” he says.

Ali’s idea is that endophytes could be applied in groups versus singly, so as to combine beneficial properties in one application.

“A broader approach can involve microbiome transplantation or the use of soil amendments and root exudates to attract and maintain beneficial microbiomes,” he says.

Currently, Ali’s group is working on a couple of projects identifying and characterizing endophytes for deployment against plant pathogens.

In one project, the team isolated more than 100 fungal endophytes from the roots of healthy apple trees. Then, they completed in vitro competition assays to assess the endophytes’ antifungal capability against apple replant disease-causing pathogens. The next step is to carry that work into a greenhouse setting, says Ali.

Plant microbiota are incredibly complex, and researchers have barely scratched the surface. Much more research is needed to understand the ways in which fungal endophytes might play a role in the field, and the impacts on plant and soil microbiota of endophyte application.

The paper concludes, “The future of agriculture will involve the increasing consideration and integration of the plant microbiome in pest and disease management strategies and, as crucial members of the plant microbiome, fungal endophytes will play a leading role.”

by Carolyn King

Barley breeding has gone high tech – and high speed.

“These days, in the Ottawa barley-breeding program, we are using cutting-edge technologies such as speed breeding and genomic selection to develop new barley varieties for eastern Canadian growers,” says Raja Khanal, the research scientist who leads this Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) breeding program.

The program is releasing a stream of high-yielding barley varieties suited to eastern growing conditions and a range of end-uses, from livestock feed to specialty markets.

Speed breeding is a way to shorten the time needed to grow successive generations of plants. Just after Khanal started with AAFC in 2017, he saw an article in Nature about this technique. He was intrigued by its exciting potential and decided to try it in his breeding program.

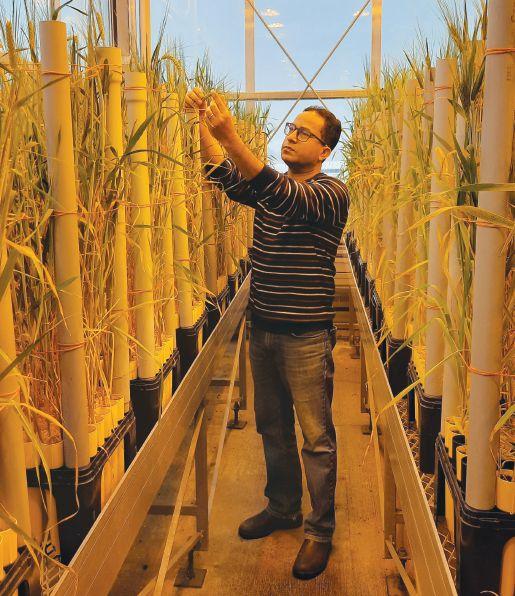

“Speed breeding uses an artificial environment with higher temperatures and enhanced light duration to create a longer day length to speed up the crop’s breeding cycle. The technique involves growing plants under near-continuous light – for example, 22 hours of light and only 2 hours of dark. That allows the plants to photosynthesize for a longer time, resulting in faster growth,” he explains. “With this technique, we’ll produce almost four generations of barley plants in the greenhouse in one year, instead of one generation per year in the field.

That will help us to reduce the breeding cycle, making our program almost two to three years faster than a conventional breeding program.”

In a conventional program, developing a new variety can take 10 or more years. With speed breeding, it might take seven or eight years. This faster approach, especially when coupled with advanced breeding tools like genomic selection, could make a big difference to growers and end-users on the lookout for improvements in key barley traits.

Khanal’s team uses speed breeding for the early generation increases in the greenhouse. “Then, after five generations, the lines go to the single-row field nursery at Ottawa; normally, I have 10,000 single-row plots. Then I make my preliminary selections out of that.”

Those selections are grown in mini-plots at Ottawa. Then, the more promising lines go to preliminary yield trials at Ottawa and Charlottetown. From there, the best-performing lines go to advanced yield trials at multiple sites in Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Ontario, as well as one site in Manitoba.

The program develops varieties suited to the different growing regions within Eastern Canada, and is the only barley breeding program to develop varieties specifically for the Maritimes. Most of the barley varieties grown in the Maritimes are from the Ottawa program.

“It is really important to have a diversity of environments in the breeding program. It leverages geography to figure out how the plant behaves in these diverse environments,” notes Aaron Mills, a research

ABOVE: Khanal takes field notes on his barley lines.

scientist in agronomy with AAFC-Charlottetown. “Here in the Maritimes, our growing conditions are more similar to Quebec than Ontario. But, especially with barley, we have a really high propensity for pre-harvest sprouting in our high-moisture environment.”

The Ottawa program works on a broad range of spring barley types, including feed, malting and food, 2-row and 6-row, and hulled (covered) and hulless types.

“Around 80 per cent of my breeding program focuses on feed barley; 2-row feed barley is almost 60 per cent of my program and 6-row is about 20 per cent. Then, 18 per cent is focused on malting barley. Although only two per cent is focused on hulless barley, that includes both food and feed types and 2-row and 6-row types,” says Khanal. “We emphasize feed barley because of the high demand from our growers.”

Fewer growers tackle malt barley production because the moist conditions common in the east tend to increase the risk of issues with disease and pre-harvest sprouting. As a result, reliably achieving malt quality can be challenging and usually involves more intensive management than feed barley production. Nevertheless, the breeding program develops some malting and hulless varieties because of the possible niche market opportunities in local craft malting and brewing industries or specialty feed or food businesses.

Improving yield is Khanal’s number one breeding priority because growers are paid by the amount they produce. Agronomic top priorities include improving lodging resistance and early maturity. In terms of disease resistance, Fusarium head blight (FHB) is a major focus. Khanal and his team tap into diverse germplasm from international

sources for FHB resistance genes, and screen their breeding materials in the FHB nursery at Ottawa. In addition, the breeding lines are screened for various leaf diseases and stem rust in Western Canada.

Khanal’s breeding program receives funding through the National Barley Cluster – a collaboration between AAFC and the Barley Council of Canada – under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership AgriScience Program. Other funders include the Saskatchewan Barley Development Commission, Alberta Barley Commission, Western Grains Research Foundation, Brewing and Malting Barley Research Institute, Grain Farmers of Ontario, Producteurs de grains du Québec, SeCan, Manitoba Crop Alliance, and Atlantic Grains Council.

Since 2018, the Ottawa breeding program has released six barley varieties, including four 2-row feed varieties: AAC Ling (2018), AAC Bell (2018), AAC Madawaska (2019), and AAC Sorel (2021). Khanal says, “Both AAC Ling and AAC Bell are licensed by SeCan. They are both high-yielding with very good lodging resistance, and AAC Bell also has a high test weight. Both are well adapted to Quebec and the Maritimes. AAC Ling received a gold award for the top barley yield of 2.49 tonnes per acre in the Yield Enhancement Network competition in the Maritimes in 2021.” AAC Ling also has fair malting quality.

“AAC Madawaska is licensed by Eastern Grains Inc. It has a high test weight and yield. It is adapted to Quebec and the Maritimes,” he notes. “AAC Sorel is licensed to SeCan. It has a very high yield, high test weight, high 1,000-kernel weight, very good lodging resistance and moderate susceptibility to FHB. It is suited to production in Quebec and the Maritimes.”

The program has also released one 6-row feed barley, AAC Cranbrook. “It has a high yield and good lodging resistance and is adapted to Ontario. SeCan licensed it in 2021.”

Khanal has a new 6-row hulless variety called OB2705n-11, which is still in the process of registration. “It has a high yield and good lodging resistance, and is adapted to production areas in Eastern Canada.”

Hulless pros and cons

Hulless barley is not actually hulless – the hull is loosely attached to the seed and is removed during combining. Khanal notes the acres seeded to hulless barley in Eastern Canada are currently very low. “Perhaps if we have more awareness about the benefits of hulless barley, some niche markets will develop and the acres will increase.”

He points to a number of positives about hulless barley. For example, the swine industry is interested in hulless barley’s higher digestible energy and higher protein content. Hulless barley also has a lower risk of contamination by Fusarium toxins because hull removal during harvest eliminates most of those toxins, if present.

“Hulless barley is a more nutritionally packed package compared to hulled barley; it definitely has a higher feed value,” notes Mills. “And hulless barley may have advantages for brewing if it can meet some of the brewing specs.”

In addition, the high levels of beta-glucan in some hulless varieties are important for food uses; beta-glucan is a type of dietary fibre with proven human health benefits. Khanal adds, “I got support for registration of a hulless food barley variety that has a really high betaglucan level – over 10 per cent – along with a high protein content. I’m still looking for a commercial licence for that one.”

One key issue for growers is that hulless barley is usually lower yielding than covered barley. Khanal sees a few reasons for that. “The main factor is that the hull attached to covered barley makes up about 15 per cent of the grain’s total weight,” he says. So hulled barleys automatically have a weight advantage over hulless barleys.

“Another factor is that we have lots of investment in breeding covered barleys in terms of bringing together genetically diverse materials for making selections and crosses. With hulless barley, we have a much smaller pool of breeding material, so making ge -

Khanal examines speed breeding work at the Ottawa Research and Development Centre greenhouse.

netic gains is not easy.”

Mills agrees, “Much more money and work have gone into breeding hulled barley varieties than hulless. As a result, we have more hulled varieties that are more suited to more environments.”

As well, even though hulless barley has a higher nutrient value per unit weight, Khanal notes buyers currently pay the same price for hulless as for covered barley grain.

As part of his breeding program, Khanal travels to different barleygrowing areas in Eastern Canada and talks with growers about their research needs.

“I found that in northern Ontario, such as the New Liskeard area, as well as some parts of Quebec, growers are really interested in hulless barley for feeding, especially in the swine industry,” he says. “Based on that, I looked through the literature to find production recommendations for hulless barley. I didn’t find any seeding rates specifically for hulless barley in Eastern Canada.”

Khanal suspected hulless barley would need higher seeding rates than covered barley to achieve its maximum yield potential. “Since the embryo is more exposed in hulless barley, it is more at risk of mechanical damage during harvesting, cleaning and seeding. As a result, it may have lower germination and establishment.”

To fill this information gap, Khanal launched a project on seeding rates for hulless and covered barley in Eastern Canada in collaboration with Mills. The two-year project took place in New Liskeard, Ottawa, Normandin, Que., and Charlottetown in 2018, and all sites except New Liskeard in 2019.

It compared three hulless varieties – AAC Azimuth (6-row), AAC Starbuck (2-row) and CDC Ascent (2-row) – and three covered varieties – AAC Bloomfield (6-row), AAC Ling (2-row), and CH2720-1 (2-row). All the AAC varieties and the advanced line CH2720-1 were developed by the Ottawa breeding program. CDC Ascent is a high betaglucan food barley adapted to Western Canada, bred by the University of Saskatchewan.

The project team compared six seeding rates: 250, 350, 450, 550, 650, and 750 seeds per square metre. In Eastern Canada, the barley seeding rates used in performance trials and recommendation tests are the same no matter whether covered or hulless varieties are being grown. These rates are: 250 to 350 seeds per square metre in Ontario; 350 to 400 in Quebec; and 350 in Atlantic Canada. In areas such as Alberta and Virginia that have rates specifically for hulless types, the recommendations are at least 400 seeds per square metre.

“In our study, we found that the optimum seeding rate differed between covered and hulless barley,” says Khanal. “For covered barley, the optimum rate was 250 to 350 seeds per square metre. For hulless barley, the optimum rate was 450 to 550 seeds per square metre.”

Mills adds, “We definitely need to increase the seeding rates for hulless barley above what we would normally use for hulled barley. Also, I think our seeding rates are a little low on barley in general on the East Coast; we don’t carry a lot of yield on our tillers, so increasing the seeding rate is a good approach for us.”

Khanal thinks that if growers use a good quality hulless variety and good management practices – including seeding rates around 500 seeds per square metre – then hulless yields will improve.

CABEF awards seven $2,500 scholarships annually to Canadian students who are entering or currently pursuing an agricultural related program full-time at a Canadian college, university or apprenticeship (trade) institution.

Every once in a while, science makes magic. Viatude™ fungicide with Onmira™ active delivers powerful white mould protection that you need to see to believe. With multi-mode-of-action control, your healthy, high-yielding soybean crop is finally free to flourish.