TOP CROP MANAGER

Editorial

Associate

Western

National Account Manager: Quinton Moorehead

Publisher: Michelle Allison

Group Publisher: Diane Kleer

Media

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Soybeans have been an important crop to Canadian farmers for decades. In 1980, Statistics Canada reported 689,800 acres of soybeans were seeded in Canada, and each and every one of those acres was planted in Ontario. By comparison, in 2017, Canadian farmers seeded 7,282,000 acres of soybeans in Ontario, Quebec, the Maritimes, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. What once was an Ontarioonly crop has evolved to be one of the most widely grown crops in Canada, with 50 to 70 per cent of production exported annually, according to Statistics Canada in 2018. And while the numbers have trended downward in recent years – partially due to trade uncertainty and poor planting and harvest conditions – Canadian soybeans are still growing strong.

Along with growing acres comes growing research and industry support. This edition – the final digital magazine in our summer Focus On series – features articles about early planting studies, the crop’s response (or lack thereof) to potassium fertilizer, improving pest control and on-farm research. With these projects and so much more happening in labs and fields across the country, Canadian soybeans have a bright future.

Stay tuned to topcropmanager.com/podcasts to catch the latest episodes of Inputs – the podcast by Top Crop Manager You can also catch up on all of the episodes from the Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture podcast series on AgAnnex Talks at agannex.com.

Optimizing the early-season environment and soil temperature for growing soybeans.

by Donna Fleury

The soybean industry in Manitoba has grown rapidly over the last few years, partly due to the introduction of better-adapted varieties. However, even with improved genetics, soybean is still inherently a coldsensitive crop and can be affected by cold temperatures in a number of ways. Finding strategies to address cold early-season soil temperature conditions may be a tool to improve soybean production in short-season areas.

“With the expansion of soybean production, we were interested in determining whether there would be a way to create an early season environment that was better for establishment of soybean crops by adjusting residue management practices,” explains Ramona Mohr, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at the Brandon Research and Development Centre in Manitoba.

“We know that seeding soybeans into cold soils can be prob -

lematic. The literature shows that if soybean seeds absorb cold water (less than 10 C) during the first 24 hours after planting, it can affect cell division and as a result impact germination and emergence. In addition, growing soybeans in short season areas adds the risk of potential spring or fall frosts that can impact the crop.”

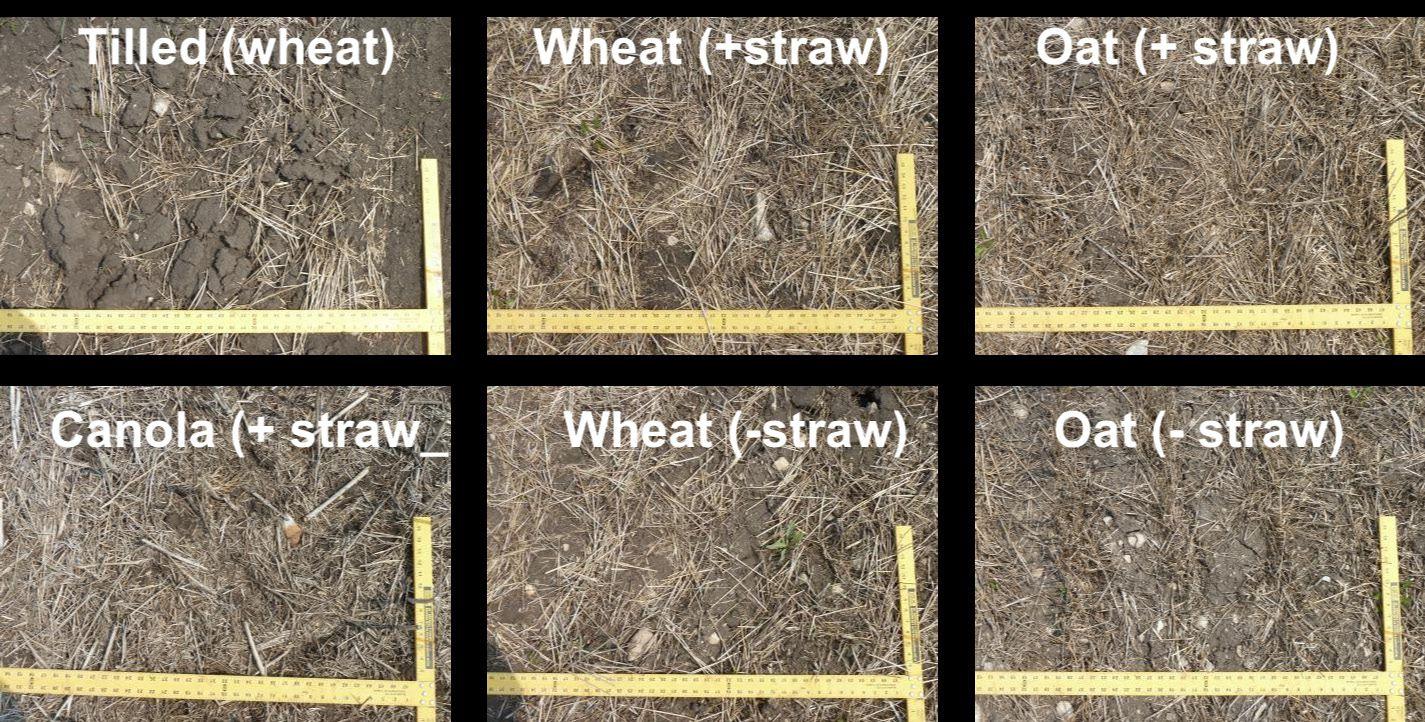

Researchers initiated field studies with co-operators at four sites in Manitoba including Brandon, Carberry, Portage la Prairie and Roblin in 2014. The goal of the project was to determine if different preceding residue management practices would have an impact on soil temperature and moisture at planting, crop emergence, and soybean performance through the growing season to final soybean yield and quality. The study included canola, wheat and oat as preceding crops to soybean, as well as a control

ABOVE: Soybean trials at the Brandon, Man. field location.

treatment of tillage. The canola plots included standing stubble with the chopped residue returned to the field. The wheat and oat plots had two different treatments, either removal of the straw and only standing stubble left, or chopping the straw and returning it to the plots along with the standing stubble.

“Our study results showed that the preceding residue management often did impact soil temperature and moisture at the time of planting,” Mohr says. “The tillage control plots and the cereal plots with straw removed and only stubble left standing tended to result in a warmer and/or drier seedbed at planting in some sites in some years. Where there were differences, tillage increased soil temperature by one to five degrees [Celsius], while removing the straw from the cereal stubble plots increased soil temperature by one to three degrees, compared to no-till treatments where straw had been chopped and returned.”

However, when researchers looked at the impact of preceding residue on soybean emergence and final yield and quality, there were few differences in the trials. Based on visual assessments of the crop, tillage and/or straw removal occasionally reduced the days to emergence by one or two days.

“As well, when we compared the soybean yield at the end of the growing season, we rarely found any differences in the effects of residue management. In two of 12 site years there were some differences, however it wasn’t clear that the differences were associated with soil temperature or moisture. It may be that the temperature differences early on weren’t enough to affect the crop, or the soybean crop was able to compensate for any small differences. Overall, residue management had limited effects on yield and various quality factors measured in the study, including seed weight, test weight, per cent protein and per cent oil of soybean.”

One important factor to note is that for this study researchers followed the recommended management practices for growing soybean in Manitoba, including seeding soybean when aver-

age soil temperature is at least 10 C, with 18 C to 22 C being ideal. In the study, soil temperatures at planting were greater than or equal to 15 C in all treatments, and soybeans were planted during or near the recommended planting window for Manitoba. Therefore, Mohr cautions that although they did not find any significant effects in their study based on current provincial recommendations, under more marginal growing conditions there may have been an effect of preceding residue management practices.

“We have initiated a follow-up study that is underway to try to determine if there may be more of an effect on soybeans under more marginal conditions compared to during the recommended timing,” she adds. “In this study, we are comparing different residue management, but only with wheat, and using two different seeding dates, early and late. The soybean seeding protocols include an early seeding date of May 10 and a second seeding date two weeks later. There are also a few additional residue management treatments, including tillage, stubble burning, short and tall stubble with either the straw chopped and returned to the stubble or the straw removed completely. We expect to get more detailed information in terms of the potential effect of the different residue management practices under more marginal conditions by the end of the study.”

For successfully growing soybeans in short-season areas, following recommended practices and using management strategies to reduce the risks of cold temperature is important. “Growers will need to take an integrated approach for managing risk of cold temperature damage, including selecting varieties adapted to local growing areas, seeding at the right time and under the right soil conditions,” Mohr says. “These strategies may be even more important under more marginal conditions. Research to identify management strategies to improve the early season environment and soil temperature to help get the soybean crop established and set up for the growing season remains a priority.”

Lack of soybean response to potassium surprising.

by Bruce Barker

Sometimes research creates more questions than answers, and that was certainly the case for Megan Bourns’ research on soybean response to potassium (K) fertilizer. In on-farm and small plot trials on soils testing low in K, a lack of yield response to K fertilizer was puzzling.

“The results led us to question whether it was soybeanrelated or soil-related. Was soybean better at scavenging potassium than we thought, or was the soil releasing more potassium than was estimated?” says Bourns, who conducted the research as part of her master’s thesis in the University of Manitoba’s soil science department.

The research was initiated because of soybean’s high K removal rates of 1.1 to 1.4 pounds (lb.) potassium oxide (K 2O) perbushel of yield. While K fertility hasn’t typically been an issue in most of Manitoba’s soils, Bourns and her supervisor, Don Flaten, a University of Manitoba professor, wanted to get a better understanding of K fertility given the recent increase in K deficiency symptoms in soybeans and the growing soybean acreage in Manitoba.

The research had several components. On-farm field trials were established with the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers On-Farm Network. Over two field seasons in 2017 and 2018, 20 site years were established. Each site was a replicated strip trial with one treatment of either 60 lb. K 2O per acre (K 2O/ac) banded away from the seed, or 120 lb. K 2 O/ac broadcast and incorporated, along with an unfertilized-K control.

Soil test K levels using the standard ammonium acetate extraction method ranged from 52 to 450 parts per million (ppm). Current Manitoba K fertility recommendations indicate that above 100 ppm, no additional K is required for soybean. At 50 to 75 ppm soil test levels, 30 lb. K 2 O/ac is recommended as a broadcast and incorporated application. Below 25 ppm recommendations are for 60 lb. K 2 O/ac.

Out of the 20 site years, two sites showed a statistically significant yield increase: one on a site with soil test levels lower than 100 ppm, but the other much higher than 100 ppm. A third site had a significant yield decrease. Bourns says a higher frequency of response was expected at the sites that were at or below 100 ppm soil test K.

The other puzzling result was that there wasn’t an agronomic or statistically significant relationship between ammonium acetate K soil test levels and yield.

Small plot trials were also conducted in 2017 and 2018, with a total of seven site years. At these sites, soil test K levels ranged from 49 to 117 ppm. Six combinations of K fertilizer rate and placement were compared: 30 or 60 lb. K 2 O/ac side-banded and 30, 60 or 120 lb. K 2O/ac broadcast and incorporated, as well as a control site with no added K.

Bourns saw K-deficiency symptoms in both years at some locations at V2-V3 stage, as well as at seed fill and persisting, in

On-farm trials showed no relationship between background ammonium acetate soil test K levels and the relative yield of unfertilized vs. fertilized treatments for soybeans

“We saw some responses on the micro-plots with increases in tissue K concentration at the R2-R3 stage, but again, we didn’t see a significant relationship between soil test K levels and yield,” Bourns says.

Barley responded where soybean didn’t

Bourns added a barley and soybean response trial adjacent to the small plot trials in 2018 to see if barley would respond to K fertilizer when soybean didn’t. In those trials, K fertilizer produced a 20 per cent yield increase in barley, but none in soybean. Bourns cautions that the barley trials were only at three sites and for one year, but it shows that something different is going on with soybeans’ response to soil test and fertilizer K.

Soybean and barley response to K fertilizer at three sites in 2018

some cases, to leaf drop.

“This indicated that the sites were low in potassium, but we still didn’t see a significant yield response to potassium fertilizer,” Bourns says. “The lack of yield response was surprising, especially given the low background soil test K levels at these sites and the presence of deficiency symptoms.”

Again, there was no agronomic or statistical relationship between background ammonium acetate soil test K and relative yield regardless of placement and rate, or on a moist or dry soil test extraction basis.

Anticipating that the amount of K in the soil and the response to K fertilizer would vary within the on-farm field trial sites, Bourns established eight pairs of micro-plots within the on-farm field trials in 2017 and in 2018. These micro-plots provided her with more data points to try to understand the relationship between soil test K levels, application rates and yield.

In looking back at the research, Bourns says several factors could have impacted the lack of yield responses to K. Both the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons were very dry, and the impact was noticeable on the sandy soils where the small plots were established. She says that if moisture hadn’t been so limiting, a seed yield response to K fertilizer may have been observed.

Potassium variability across the small plots also presented challenges. The differences in soil test K from one plot to another within the same site were much greater than anticipated and could have masked the ability to measure a yield response to K fertilizer.

The final challenge, and surprise, was that the ammonium acetate test threshold of 100 ppm did not accurately predict soybean response to K fertilizer.

“The world of potassium isn’t simple. Soybean fertilization is a challenge to work with. The same lack of response in soybeans has been seen with phosphorus fertility,” Bourns explains.

Flaten had hoped that the research would help inform soil scientists on how to update K recommendations for soybeans in Manitoba.

“It can be frustrating to work with a crop like soybean that doesn’t respond to fertilizer and soil tests in the ways that we’re used to. However, the barley test that Megan ran in 2018 was very valuable, because it identified that our conventional soil test could predict potassium response with barley and not soybean, so we know something different is going on with soybean,” Flaten says. “I can’t recall seeing any other study that reported on potassium response in soybean compared to other crops, although other studies have shown somewhat similar results for K responses in canola being much less than in barley.”

For now, Flaten says farmers and agronomists should rely on current K fertilizer recommendations, but advises to monitor K soil test levels to ensure that they do not draw soil fertility down too low.

“There’s no compelling reason for farmers to add potassium if soil test levels are above 100 ppm for soybeans, but soybeans are such a pig for uptake and removal of potassium that we need to watch fertility levels over the longer term,” Flaten says. “The results show that we’re not quite ready to provide new potassium recommendations in soybeans.”

by Julienne Isaacs

Anew study from the University of Manitoba suggests producers can help control soybean aphid populations by including cereals in soybean rotations and increasing landscape diversity.

The study, which was led by department of entomology professor Alejandro Constamagna, and conducted by his graduate student, Ishan Samaranayake, ran between 2014 and 2016. The study looked at soybean fields in landscapes with varying levels of complexity – from areas with little diversity to areas with diverse vegetation, wooded areas and riparian areas.

Costamagna’s team studied the movement of natural predators of soybean aphid, including hoverflies, minute pirate bugs, lady beetles and green lacewings, between these neighbouring habitats and soybean fields, and between neighbouring crops and soybean fields, and correlated this movement with soybean aphid suppression.

Their findings were unexpected. “We thought we’d find a good correlation between the amount of natural vegetation and soybean aphid suppression,” Costamagna explains. “Instead, we found that the amount of wheat and other cereals in the landscape was one of the factors that was associated with high pest control in soybean.”

But the finding makes sense, Costamagna continues, because of the “temporal component” of these systems.

Cereals harbor aphid populations early in the season before soybeans can support them, and aphid predators follow them into these crops, increasing their populations. Once wheat and other cereals start to senesce, these predators move into soybeans and help control soybean aphid populations.

“The positive correlation between the proportion of cereals in the landscape and the movement of green lacewings further suggests that cereals can act as sources of beneficial insects for soybean,” the authors note.

This finding is part of a broader conclusion to Costamagna’s study – namely, that it’s crucial to understand patterns of natural enemy movement so biological control of insect pests can be facilitated in cropland.

Most studies look at soybean aphid populations while ignoring nearby habitats, he says. But soybean aphid predators don’t reproduce in soybeans, which means they must have habitats in nearby landscapes in order to perform pest control services in soybean.

“The big picture idea is to figure out the sources of beneficial insects in the landscape. These are generalist predators, in that they feed mostly on aphids, but they’re not habitat specialists, but can move across different habitats,” Costamagna explains. “What we hope to show is some combination of crops and natural habitats that maintain high populations of these generalist predators in wheat, canola, alfalfa and soybean.”

In the study, Costamagna’s team used interception traps at field borders to capture insects flying between soybean fields and neighbouring cropland or natural vegetation.

As long as they have a cell signal in the field, soybean producers can find spraying decision support in their own back pockets. Aphid Advisor (aphidapp.com) is a pest management decision-making tool that helps producers determine whether spraying is necessary. Producers input aphid counts as well as natural enemy numbers and the app makes a recommendation – to spray or not to spray – based on expected population increases and the presence of natural predators.

Using the traps, they noted, for example, that predators, especially green lacewings and hover flies, move from wooded areas into soybeans more than from soybeans to wooded areas. Some

aphid predators have adapted to feed on tree aphids early in the season, Costamagna says.

“Later, when the crops senesce, the natural vegetation is all that’s left and again there’s another increase in aphids on trees during the fall. There they can feed before overwintering.”

A key lesson from the study is that landscape diversity is key so beneficial insects have multiple habitats within the farm and neighbouring landscape and can be supported during the entire growing season by moving from habitat to habitat.

Costamagna says producers should take natural predators into account when making spraying decisions.

This recommendation is echoed by John Gavloski, Manitoba’s provincial entomologist.

“We recommend scouting and proper use of thresholds, first and foremost,” Gavloski says. “The problem is, if you don’t have an economic population of crop-feeding insects, you can do more harm than good by taking out the predators, parasitoids and pollinators.”

The soybean aphid action threshold is an impressive 250 aphids per plant with the population continuing to increase, he says. But the economic injury level, at which the cost of yield losses is equivalent to the cost of treatment, is much higher – 670 aphids per plant. It is

It’s crucial to understand patterns of natural enemy movement so biological control of insect pests can be facilitated

in cropland.

because aphid populations can potentially increase rapidly that the action threshold has been set so much lower than the economic injury level.

But just because thresholds are nearing 250 aphids per plant does not mean aphid populations will continue to increase, Gavloski says.

“One of the myths about aphids is that they keep on increasing. Sometimes it works that way, but we have seen situations where agronomists were keeping an eye on fields that were getting close to 250 aphids per plant, and the natural enemies were able to stabilize or decrease the aphid population.”

This means it’s crucial for producers to scout at least twice before spraying.

The critical window for spraying an insecticide falls between the first bloom and the R5 stage when seeds are filling, Gavloski adds. This is the time when aphids can cause most damage. After this window, research has not shown a reliable yield gain from an insecticide application.

Soybean aphid populations vary by the year. In 2014 and 2015, there were moderate levels and low levels in 2016, but 2017 was a very bad year for soybean aphids, he says, and it was necessary for many producers to spray. Levels were low again in 2018 and 2019 and no insecticide applications were needed.

But spraying doesn’t necessarily mean beneficial insects have to take the hit along with soybean aphids. Gavloski says selective insecticides are available that specifically target aphids and do not kill beneficial insects, such as predators and parasitoids of aphids.

Producers running their own trials can keep a few tips in mind to make the most of on-farm research.

by Julienne Isaacs

Interest in on-farm research trials is growing in Western Canada due to momentum added by commodity and industry groups and independent contractors invested in facilitating it, according to Megan Bourns, who heads the On-Farm Network for Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers Association (MPSG).

“We’re doing research with between 60 and 70 producers each year in Manitoba. If you look at the total number of farmers in the province it’s a small proportion of the total population, but the number is growing,” she says.

Producers tackle a huge number of research questions on the farm – anywhere from trialing new products to assessing seeding rates or fertilizer treatments, rates, sources and timing. They also use on-farm trials to assess different management systems, such as strip tillage compared to conventional tillage.

Lana Shaw is manager of Saskatchewan’s South East Research Farm. Shaw just began a three-year intercropping trial and is in regular communication with producers doing their own on-farm intercrop experiments. She says some farmers begin their own on-farm research trials to investigate practices, like intercropping, that aren’t seen as mainstream enough for funders. “So the farmers start saying, ‘If they’re not doing the research, then we need to do it,’” she says.

“The on-farm data leads to an increase in adoption of acres, which leads to commodity groups saying, ‘This is worth investing time and money in.’ Until we had crop insurance data on intercropping acres, it was easy to ignore it because we didn’t know how much there was in the province.”

In the case of intercropping in Saskatchewan, farmers led the way in identifying the practice as a research priority. Farmers have been doing their own on-farm intercrop trials since 2010, Shaw says, but 2019 was the first year multiple funders stepped forward to power a multi-year study across Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan Crop Insurance data noted 72,400 intercrop acres in the province in 2019.

On-farm research is empowering, Shaw says, because farmers can take the reins on investigating practices that have a direct impact on farm management and their bottom line.

Bourns says trial design and analysis is generally taken care of for producers hosting industry group trials on the farm, but producers running their own trials can keep a few tips in mind to make the most of on-farm research.

an appropriate research question

According to Bourns, the very first step producers should take before setting up an on-farm trial is to identify a trial question they want to answer on the farm.

“You need to determine what you’re looking to get out of the trial. That will have cascading effects. The question needs to be specific and applicable to normal practices on the farm,” she says. “The question shouldn’t lead you to selecting treatments you’d normally never apply.”

At press time, one farmer Bourns works with intended to set up a tillage trial in the fall to investigate fertility practices in strip-tilled versus conventionally tilled systems.

“On-farm research trials are flexible – you’re generating sound data that will be directly applicable on the farm.”

Bourns says farmers should select treatments that reflect real-world decision-making on the farm.

For example, many farmers choose to investigate N rate applications in wheat or corn. In a formal small plot trial, typically researchers would include a zero-N check, but this doesn’t make sense in a farm

setting, Bourns says.

“Zero-N is not a normal practice, so why would we include that treatment? The check in an on-farm trial will be the farmer’s normal fertility practice so they can modify or validate that practice,” she says.

Once the research question and treatments are selected, trial design and layout will make or break the utility of data coming out of it, Bourns argues.

Design ideally should include randomized and replicated treatments to account for field variability and remove bias from trial data.

“We like to see between four and six replicates. If it’s a two-treatment trial, we’d have those two treatments replicated four to six times across the field in eight to 12 field strips running the whole length of the field minus the headlands,” Bourns recommends.

When it comes to randomizing the treatments within the trial, producers should avoid areas that will induce a major yield difference –for example, if a field drain runs the length of a field, they should avoid

placing a treatment strip along that stretch.

Based on the results producers are hoping to collect from the trial, they might want to consider collecting data mid-season, Bourns says.

In a soybean inoculant trial, for example, mid-season evaluation of the trial plots can help producers assess crop performance if there’s no yield difference at the end of the season.

Shaw adds that collecting mid-season data can help trials pay off for producers if they don’t have time to separate trial plots during a tough harvest.

“If it all ends up in the combine, even if you don’t get good yield data you might be able to get some other data points,” she says.

Producers can easily get out in the trial strips in August before harvest to do plant counts and check establishment rates and evaluate plant height, for example. “Those are things you can do before things get hectic. If there’s time during harvest you can get the yield data, and if something goes wrong you’ve still got something.”

Shaw encourages producers to do this when they’re evaluating flax seeding rates in a chickpea-flax intercrop. “It’s not technically hard to go out and count chickpea pods, and if you have twice as many pods on one strip compared to another strip that will tell you something important.”

5. Consider using a weigh wagon

Yield difference is typically a key factor for producers and the number one reason they conduct on-farm trials, so collecting yield data properly is important.

Shaw says using in-cab yield monitors alone might not provide precise enough data unless the monitors are properly calibrated.

“If you can calibrate your monitor, that gives you more confidence, but changes in moisture content of your grain, for example, can greatly affect your yields, so you need to be looking at yields adjusted to a common moisture content,” she says. “That’s something we do on smallplot trials — we adjust them down to a standard moisture percentage.”

Yield monitor data typically contains “white noise” that needs to be cleaned up before the data can be used, so producers are probably better off using a weigh wagon or grain cart with a scale than pulling yield data from monitors, she says.

“They’re making multi-thousand dollar decisions.”

6. Find your research community

One of the benefits of working with an industry group on a trial is that farmers don’t have to do their own statistical analysis of trial data.

But just because producers are working on their own doesn’t mean the data can’t be useful to other farmers.

If producers are not working with an industry group on a trial, it can be helpful for them to identify a group of other farmers in their area with an interest in conducting similar research.

Shaw says the farmers doing the most successful research in her area typically tap into a peer group or producer club or other agreedupon network of producers for support with their trials and even assistance with analysis. This is particularly helpful when producers don’t have replication for each treatment in a trial. If other producers in a region are doing similar experiments, they can pool their data to gather some rough statistical results.

But Shaw says producers shouldn’t obsess over the statistics; lots of farm decisions are provisional, and as farmers adjust their practices they can learn from each other.

“You don’t necessarily need a lot of data to say, ‘This and this practice made me more money, and that’s why I’m increasing acres.’ That says a lot,” she argues.

“As long as they’re seeing that what they’re doing is better than what they were doing before, there’s a path forward. Each year you need to be out there observing and learning and tweaking,” she says. “Then in the winter we get together and talk about what worked and what didn’t.”

7. Invest the time now for the payoff later

Bourns says the number one investment farmers make in on-farm research trials is time during the two busiest times of the year: seeding and harvest.

“There’s a cost, but if they’re looking at investigating a new management practice, when it comes to penciling out the economics, it can be better to take the time now to do a trial on one part of the farm rather than doing it on the whole farm,” she says.

Especially during harvests like 2019, taking the time to do on-farm research can be a hard sell, she says. But in Bourns’ experience, most producers who invest in on-farm research see the value of the data and are willing to go through the process again. Christian Autsema is the assistant manager for Oak Ridge Holdings, a 5,000-acre farm west of Carman, Man. Over the last seven years his farm hosted at least five research studies run by Manitoba Agriculture, University of Manitoba and MPSG to investigate fertility treatments on the farm’s “rather challenging” sandy soils.

“We have learned lots about the fertility of our soils and why more N, P or K may give a cosmetic result but no return on investment,” Autsema says. “On our soils, applying more K than the crop needs to grow is a waste since excessive K is being tied up due to the high amount of free carbonates.

“Another saving we have seen is that we confidently put very little P with soybeans on a field we know we won’t rent the next year. The crop will yield normally anyway, despite the fact that we fertilize below its requirements. Without the test plot we would have never dared to do such a thing,” he says.

Working with the research community has been extremely positive for Oak Ridge, but the best payoff has come from the data itself, which is tailored to the farm.

“We’ve gained lots of knowledge which we could apply on a larger scale,” Autsema says.