TOP CROP MANAGER

3 | Strip till in soybeans By

Bruce Barker

6 | Harnessing the soybean genome By

Carolyn King

10 | Economic and biological implications of volunteer canola in soybean By

Donna Fleury

12 | Learning from intensive soybean management in Minnesota By

John Dietz

Louise O’Donoughue of CÉROM walks through her soybean plots that are part of the SoyaGen maturity trials across Canada. PHOTO COURTESY OF SOYAGEN.

Small but mighty, soybeans are hard to overlook. Canadian farmers have been planting soybeans for more than 70 years, and their popularity continues to grow: producers in Canada planted 6.3 million acres in 2018, according to Statistics Canada, with Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec and Saskatchewan leading the way as the country’s largest-producing provinces.

New research and development has contributed to this growth, and we’re highlighting some of the latest soybean research in this instalment of our summer digital series. From breeding projects to management tips, Top Crop Manager Focus On: Soybeans highlights initiatives from across North America to provide you with more insight into the potential of this crop.

In our regular print issues, we don’t often get a chance to cover research happening outside of Canada, but we’ve highlighted a couple of different studies happening in the United States in this issue that you’ll no doubt find interesting. On page 3, Bruce Barker breaks down a study on best practices for strip till on soybeans, and results from Minnesota and North Dakota. And on page 12, you’ll read about what growers in Minnesota are doing to achieve record soybean crops. The secret, according to Seth Naeve, is a combination of reducing costs while maintaining yields.

As always, we hope you can implement some of the tactics you read about among these pages to help your crop thrive. Don’t miss our final digital edition, Focus On: Herbicide Resistance (part 2), in September.

Editor: Stefanie Croley

Associate Editor: Stephanie Gordon

Western Field Editor: Bruce Barker

Associate Publisher: Michelle Allison

National Advertising Manager: Danielle Labrie

Group Publisher: Diane Kleer

Media Designer: Jaime Ratcliffe

by Bruce Barker

Strip till offers several benefits to soybean growers on heavy residue stubble. A key benefit on sandy loam soils is leaving residue on the soil surface to protect against soil erosion by the wind – an occurrence in recent years after snow melts on tilled soils.

Reducing the amount of tillage passes to prepare the seedbed can also reduce input costs and save time, but questions arise regarding the impact on soil temperature, crop growth, maturity and yield. Patrick Walther, a graduate student at the University of Manitoba under the supervision of Yvonne Lawley, compared different tillage systems on corn stubble to see if strip till has a fit in Manitoba.

Walther conducted two years of research at the following sites in Manitoba: Winkler and MacGregor in 2015, and Haywood and MacGregor in 2016 on sandy loam soils. He compared double disc, high disturbance vertical tillage (six degree angle on disc), low disturbance vertical tillage (zerodegree angle on disc) and strip till implemented in the spring or fall. Soil temperature was measured at five and 30 centimetres deep, and soybean growth, maturity and yield was observed.

Soybeans were planted on 30-inch row spacing using a planter with disc openers and no trash cleaners.

Soil temperature and emergence

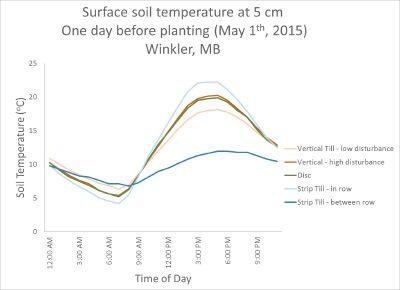

Walther first looked at soil temperatures. An example of the differences between tillage treatments is shown one day before planting on May 1, 2015, in Winkler. High disturbance disc and

vertical tillage treatments followed fairly similar paths as the soil warmed up during the day and cooled off at night.

“Interestingly, strip till had lower night time temperatures and higher day time temperatures,” Walther says.

Walther says there may be several reasons for the difference in strip till temperatures. The first is that strip till pushes trash to the side so that the residue is not acting as an insulator. The bermed soil left by strip till has greater black soil surface area exposed than flat soil, promoting more warming and cooling. The berm is also fluffier than tilled soil, with more air pores that warm up and cool down faster.

Although differences in soil temperature were observed on an hourly basis on individual days, the impact of these temperature differences need to be considered over time to understand their impact on an emerging plant says Walther. Hourly temperature above 10 C (base temperature for soybean) was added up for the first ten days after planting. This accumulated temperature effect revealed no significant temperature differences in the seedrow among treatments at any site-year. This explains why there were few differences in emergence for the soybean test crop he says.

While soil temperatures are interesting, emergence, crop growth and yield pay the bills. In three out of four site years, Walther did not find any statistical difference in emergence between the tillage treatments. At the fourth site, strip till lagged behind in emergence but the final plant stand ended up

being the same at 30 days after planting.

“Soybeans are good liars early in the season anyway. What is much more important is plant growth at flowering and pod stages, which is where you make the yield,” Walther says.

Days to flowering and percentage flowering were different between 2015 and 2016. In 2015, days to flowering and percentage flowering were very similar among tillage treatments. In 2016, disc treatments were slower to flower. For example, in MacGregor in 2016, the disc treatment was about 30 per cent flowering at 47 days after planting but strip till was over 75 per cent in flower.

Statistically, strip till soybeans grew the tallest, but only two cm taller, so not agronomically very important. Pod height had highly significant differences, but again, not that agronomically

A comparison of tillage fuel costs.

important. Measured from the bottom tip of the lowest pod to the soil surface, strip till was 60 millimetres (2.4 inches) compared to 65 millimetres (2.6 inches) for double disc and high disturbance vertical till, and 69 millimetres (2.7 inches) for low disturbance vertical till. So, still achievable for floating cutterbars on a combine.

There were no statistically significant differences in pods per plant. As a result, for the four site years of research, no significant differences in grain yield were observed.

The only yield-related difference was with grain moisture. Strip till soybeans had significantly lower grain moisture content of 13.38 per cent compared to double disc at 14.29 per cent.

“The residue management treatments in this experiment were dramatically different and we were expecting large differences in yield, but what ended up happening, with no differences in yield, was unexpected,” Lawley says. “This is good news because it means there are a variety of approaches – including strip till – that will work for farmers to manage corn residue before soybeans.”

Walther also looked at yield monitor data to see if there were differences in yield variability across fields depending on tillage treatments. He found that all tillage treatments had similar yield across the field, indicating all tillage

treatments had similar consistency across field variability.

Strip tillage more economical Walther partnered with Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute (PAMI) to look at tillage costs in the different tillage systems. They identified a major advantage in strip till, which used three times less fuel compared to double disc. Strip till only required one tillage pass, either fall or spring, compared to two passes for the other high disturbance tillage systems. As an example, if you consider an average farm in Manitoba of 1,134 acres, if the whole farm were planted to corn, managing the corn residue with strip till would save a farmer up to 3.7 days compared to double disc.

“Farmers say I don’t care so much about fuel but my time is important. Eliminating one tillage pass was an additional major benefit,” Walther says. Walther says the results of the research show that strip till on sandy soils look promising for soybean growers. A strip till system could bring major time, input and soil conservation benefits. Typically conducted in the fall, a strip till could also include phosphate (P) fertilizer applications that would allow farmers to meet the high P demands of soybeans without having to just rely on soil or starter P.

Research in Minnesota has found similar results for soil temperature, growth and yield when soybeans are grown with strip till systems. University of Minnesota research from 2010 through 2012 compared chisel plowing with spring field cultivation, disc ripping with spring field cultivation, fall strip tillage and two passes with a shallow vertical tillage implement. Yields between the tillage treatments were not statistically different.

In a separate three-year study during 2006 to 2008 in southern Minnesota, researchers compared soybean yields among chisel plowing, strip tillage and no-till for fields previously planted in strip-tilled corn. The type of tillage had no effect on the soybean yields during the three years.

A new four-year study was implemented in 2015 by North Dakota State University and University of Minnesota. This multi-state effort is in year three of a six-year field study. Four on-farm locations are under a corn-soybean rotation and rotate each year. At each location, the four tillage practices are demonstrated using full-sized equipment in plots of 40 or 66 feet wide by 1,800 feet long in a replicated design. At each site, a chisel plow, vertical tillage, strip till with shank, and strip till with coulter systems are demonstrated The soil types at the four sites included Fargo silty clay, Lakepark clay loam, Barnes-Buse loams, Delamere fine sandy loam, and Wyndmere fine sandy loam. These soils cover over 67 million acres of farmland in the Northern Great Plains regions. During the spring of 2016, soil temperatures and water contents did not tend to differ among tillage practices except for a brief period of approximately seven to 10 days immediately following soil thaw in early March. This was primarily due to the dry spring conditions and relatively low soil water contents. These differences would likely persist for longer periods as spring precipitation increases. Soybean yields in 2015 and 2016 did not significantly differ among tillage treatments.

Improving yield and disease resistance in short-season soybean.

by Carolyn King

Amajor research project called SoyaGen is tapping into the power of genomics to really boost Canadian soybean breeding advances.

According to project co-leader François Belzile, SoyaGen is tackling three key challenges in developing high-yielding soybean varieties for Canadian conditions: adaptation to Canada’s short growing seasons; enhance genetic resistance to three of the top yield robbers (phytophthora root rot; soybean cyst nematode; and sclerotinia stem rot); and addressing the challenge of adoption of soybean as a new crop by producers in Western Canada.

Belzile and Richard Bélanger, both of Université Laval, are leading this four-year project, which started in 2015. The team of researchers that Belzile and Bélanger put together come from Laval, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Centre de recherche sur les grains (CÉROM), University of Guelph, University of Saskatchewan, and Prograin. Belzile and Bélanger have also brought together diverse agencies to fund SoyaGen, including grower organizations in both Eastern and Western Canada, Western Grains Research Foundation, seed industry companies, Genome Canada, Génome Québec and others.

This collaborative initiative is addressing those three challenges through five activities.

The team working on Activity 1 has already created foundational information about the genetic makeup of Canadian soybeans. “The Canadian soybean germplasm is now probably better known than any other country’s soybean germplasm, be it the U.S., Brazil, China, or anywhere else,” Belzile says. “Of course we have a smaller set of soybean materials, but we’ve probably captured a better overall picture of what makes a soybean a Canadian soybean than anywhere else.”

The researchers used two approaches to capture that genetic information. “The most comprehensive examinations were what we call whole-genome sequencing – determining the entire sequence of all the DNA in a specific soybean variety. We did that for 102 different varieties that we felt captured the diversity present in the Canadian soybean crop,” he explains.

<LEFT:The soybean cultivar on the left is highly susceptible and the other is highly resistant to phytophthora root rot, one of the diseases targeted by the project.

BOTTOM:These young soybean plants in a Laval greenhouse will be tested for resistance to Sclerotinia stem rot as part of SoyaGen’s search for new disease resistance genes.

<LEFT: Louise O’Donoughue of CÉROM walks through her soybean plots that are part of the SoyaGen maturity trials across Canada.

“Then in parallel, we developed methods that allowed us to do more of a genome scan. So instead of inspecting every single base in the nucleotides [the building blocks of DNA] – there’s a billion different [base pairs] in there – we wanted to do more of a spot check here and there, which would be a lot less expensive but would still yield a lot of useful information,” Belzile says. “By pulling these two together, we are able to provide breeders and research scientists with a very good idea of how varieties differ from each other, how closely related they are, and those sorts of things.”

This genomic information is invaluable for crucial tasks like the use of DNA markers to rapidly screen breeding materials for traits of interest. Using markers is much more efficient than having to take weeks or months to grow seeds into plants and test them for the traits of interest.

In addition, the researchers have transferred their genetic characterization methods to the genotyping service already operating at Laval. “Now, if somebody from the private or public sector wants to have their soybean lines characterized using these technologies, this service is available,” Belzile says.

“In Canada, we have a [soybean breeding] system with really big players, the multinationals, and some companies that are more local. Typically these more local companies don’t have the full range of equipment and expertise that the multinationals might have. So for them, being able to outsource some of this high-level genetic analysis evens the playing field so they can be more competitive with the bigger players.”

“Activity 2 is tied into the question of adaptation and maturity,” Belzile says. “We need a good understanding of the genes that regulate and hasten maturity in order to develop soybean varieties that reach maturity within the time frame that exists in the different regions of the country.”

So, some of the work in Activity 2 involves identifying and understanding the genes affecting maturity. Through characterizing the 102 lines in Activity 1, the researchers have been able to group those lines into five different maturity packages – different combinations of genes that control maturity.

The Activity 2 team is now testing those five packages at eight sites across the country to better understand how their genetic characteristics allow them to adapt

to different regions. “At each site, we’re revealing what is the best package for that site. So, if you want a variety that is highly adapted and will yield better in Saskatoon, then you would need to put together this particular package, and if you want a variety for the Montreal area, it might be a different package,” he says.

“So, in terms of information that is of immediate relevance and use to breeders in developing adapted and better adapted varieties, this is very concrete and very useful.”

Activity 3 revolves around the races of soybean cyst nematode and of Phytophthora sojae , which causes phytophthora root rot. Knowing which specific races/ pathotypes/strains of a pathogen occur in an area is important for both breeders and growers. Breeders need that information when using genes that confer resistance to only certain races of the pathogen. And growers need to be able to choose varieties with the right resistance genes for the races in their fields. However, current techniques to determine the races of Phytophthora sojae and soybean cyst nematode have limitations such as being time-consuming, complicated and/ or unreliable.

For Phytophthora sojae , the Activity 3 team has developed a faster, more reliable way to determine the race of an isolate. Belzile says, “With phytophthora, we are right now in the phase of developing a diagnostic kit that we hope will be of interest to some diagnostic labs so they could offer the testing service to farmers in the future. A similar type of kit is also under consideration for soybean cyst nematode although it is more difficult to get to the level of precision needed.”

As well, the researchers hope to collaborate with government or industry to conduct systematic sampling for Phytophthora sojae in Canada’s soybean-growing areas. Then they’ll use the new diagnostic test and produce a map of the distribution of the pathogen’s races for use by growers and breeders. Ideally the map would be updated every few years to keep up with the pathogen’s race dynamics.

Activity 4 is developing new, more effective resistance genes to fight Phytophthora sojae , soybean cyst nematode

and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum , the cause of white mould. For each of these pathogens, the research team is identifying soybean lines with new sources of resistance and developing DNA markers associated with these resistance genes. Breeders will use the markers to bring the new resistance genes into their breeding materials.

In particular, the researchers hope to discover resistance genes that provide non-race-specific resistance. Belzile explains, “That would enable breeders to move away from the race-specific resistance genes that are always going to be subject to being overcome [as the pathogen adapts].”

“In the fifth activity, we’re trying to understand the barriers to soybean adoption in Western Canada,” he says. “For example, is it that farmers feel they don’t have enough information about how to grow the crop? Is it that there is a lack of adapted germplasm that will do well in their region? What are the issues facing farmers in terms marketing their crop, transporting it to crushing plants? These are the types of questions we are trying to answer.”

This socio-economic work will be engaging growers, agronomic consultants, extension specialists and others in the research process, in the design of better extension tools and in the development of an extension strategy to increase the adoption and success of soybean production on the Prairies.

The Canadian soybean genomic information and the genotyping methods developed in Activity 1 provide a powerful springboard for further soybean breeding work. One of the ways the researchers are working toward leveraging this effort is by developing a new method for selecting promising breeding materials.

“We want to use information on the genetic makeup of a soybean line to determine whether or not that line is promising or not,” explains Belzile. “Right now, a breeder makes a cross between individual A and individual B. At some point down the road, the breeder looks at the progeny of that cross and how the plants are behaving in the field

and makes selections based on that.” It takes many years, a lot of plots, and a lot of data collection and analysis to assess something like the yield potential of a specific progeny.

“Our alternative method, which we call genomic selection, aims to predict the behaviour of a certain individual plant in the field based only on its genetic makeup. This method examines the genetic makeup of thousands and thousands of individuals and runs that through these models that we develop, and then provides predictions for the behaviour of these individuals if they were to be grown as a variety.”

So a breeder could determine the most promising plants much earlier in the breeding process, saving time and money – and bringing new varieties to growers faster.

“We already use genetic information to select lines that have certain characteristics. For example, you might have a genetic test that will tell you that this line has the right gene to be resistant to soybean cyst nematode. That’s one test for one trait,” he explains.

“But with genomic selection, we’re examining thousands and thousands of DNA markers in all of our lines. And based on that, we are predicting the behaviour of many, many traits – yield, seed protein content, oil content, maturity, height and all these other associated traits that typically a breeder will rely on to make predictions.”

Belzile thinks one area where genomic selection is particularly promising is for complex traits like yield. “Yield depends on probably hundreds if not more different genes. You can’t find one marker for yield; you have to rely on a much, much wider array of markers. Genomic selection can capture all of that genome-wide information.”

The SoyaGen team is making substantial progress, developing practical results for Canadian soybean breeding programs, advancing the development of higher yielding, more disease-resistant, earlymaturing varieties for growers, and providing a foundation for launching future breeding success. For more information on these projects, visit soyagen.ca.

An integrated approach at multiple life stages is necessary to manage herbicide-resistant volunteer canola populations in soybean production.

by Donna Fleury

Soybean production is intensifying across Western Canada, and for producers, managing herbicide-resistant volunteer canola populations can be challenging. Volunteer canola is one of the top abundant weed species in Western Canada and can be very competitive in all soybean crops. However, researchers have identified weaknesses in the volunteer canola life cycle that can be exploited to manage this weed, and have developed management strategies to help producers grow crops in rotation effectively and profitably.

Rob Gulden, associate professor at the University of Manitoba, and graduate students Charles Geddes and Paul Gregoire, conducted a number of different studies over the past few years to address the challenge of managing this herbicide-resistant weed. They studied a range of agronomic management practices

that could be implemented in an integrated weed management (IWM) program at different life stages of volunteer canola to reduce the seedbank numbers and crop impacts.

“In the first study, we examined seedbank management strategies, such as tillage options after canola harvest to minimize seedbank persistence over the first winter,” Gulden says. “Results of earlier surveys from about five years ago showed that producers are still losing a lot of canola seed at harvest, which can greatly add to the weed seedbank. We found that a light and timely tillage pass shortly after canola harvest is a good control point and pretty effective at reducing seedbank numbers for the next spring. Light tillage means a simple harrow pass at the right time to encourage volunteer canola weed seedlings to germinate. Under typical winter conditions, winterkill of seedlings reduced

seedbank persistence of volunteer canola in the spring. However, a really late tillage pass just before freeze-up was not as effective.”

Researchers also looked at cultural and mechanical approaches that could be used in an IWM program to make soybean more competitive with volunteer canola. Cultural practices such as row spacing, seeding rates and soil nitrogen (N) levels were evaluated, as well as mechanical approaches including inter-row tillage and mulches. “We concluded from the study that is it very difficult to make soybean more competitive with volunteer canola,” Gulden says. “The main factors that contributed to increased soybean competitive ability were seeding rate and residual soil N levels. Although higher seeding rates didn’t have a big impact on volunteer canola, it did help retain optimum soybean yields. Surprisingly in this study, the effects of row spacing were minimal, however, we have seen positive results in other studies and are continuing to test this strategy. Planting soybean on fields with limited available soil N, and avoiding N fertilizer application in soybean, may provide a competitive advantage over volunteer canola.”

The results of inter-row tillage as an approach showed that although it was not a perfect solution, inter-row tillage did work reasonably well, particularly in wider row spacing.

studies led by Chris Willenborg at the University of Saskatchewan, and separate trials with Xtend and Enlist soybean varieties. Overall, the results showed there are a number of herbicides with various modes of action that are effective for in-crop management of volunteer canola in soybean. Herbicides with faster acting modes of action were more effective at preventing soybean yield loss, particularly when volunteer canola was developing quickly at the beginning of the critical period of weed control in soybean. Xtend and Enlist soybean varieties required an in-crop herbicide effective on volunteer canola to maximize volunteer canola control and soybean yield. In both systems, the best herbicide choices were not always consistent among and locations and years and appeared to be influenced by the developmental rates of volunteer canola and soybean.

The results of inter-row tillage as an approach showed that although it was not a perfect solution, inter-row tillage did work reasonably well, particularly in wider row spacing. An assessment of living and terminated mulches, both spring wheat and winter cereal rye, were effective at reducing volunteer seed production in soybean without affecting soybean yield relative to without the mulch controls. Unlike rye, living spring wheat mulch developed into an intercrop and produced additional wheat yield at soybean harvest. Overall, IWM techniques were more effective at locations with high densities of volunteer canola seedling emergence.

One of the big questions addressed was the economic impact of volunteer canola in soybean and the action thresholds. “One of our objectives was to determine the effects of increasing densities of volunteer canola in soybean planted at narrow (7.5-inch) and wide (30-inch) row-spacing on soybean yield, growth and development,” Gulden says. “The resulting yield loss was used to determine action thresholds at five per cent soybean yield loss to assist producers when planning to apply an additional herbicide to control volunteer canola in soybean. Volunteer canola is very competitive, and the action thresholds for volunteer canola in soybean are low at three to five plants per square metre. When differences between narrow- (7.5-inch) and wide-row (30-inch) soybean production systems were observed, narrow-row soybean were more competitive and had higher action thresholds before a five per cent yield loss was observed.”

Researchers also used digital image analysis to see if they could find a relationship between early season total ground cover with increasing volunteer canola densities and soybean yield loss in narrow- or wide-row soybean. The study showed that digital image capture early in the season was effective at predicting soybean yield loss. However, various factors such as soybean row spacing, crop and weed developmental stages at the time of image capture and others suggest that a single, universal yield loss model applicable to all situations may be challenging to develop using early season ground cover data only.

Gulden notes the project also considered herbicide options for managing volunteer canola in soybean, including collaborating on

“Overall, results from the various study components confirm that volunteer canola can be a highly competitive weed in soybean production and is relatively insensitive to many weed management tactics, especially at lower plant densities,” Gulden says. “Implementing an integrated approach to weed management at multiple life stages is therefore necessary to manage herbicide resistant volunteer canola populations as soybean production intensifies in Western Canada. Management practices that reduce seedbank numbers remain a top priority. Our study also indicated that reduced soil N, elevated seeding rates, and inter-row tillage in wide-row production systems may be the best integrated weed management options for managing volunteer canola in soybean at this time, but may need to be used in combination with herbicides to target this weed.”

True efficiency is best measured in yield-per-input and acre-based management.

by John Dietz

Extreme yields in soybean production grab headlines, but growers would probably benefit more from a different management approach, says Seth Naeve, associate professor and extension soybean agronomist at the University of Minnesota in St Paul.

According to Naeve, a shift in industry thinking has occurred in the past 10 years. The old paradigm was about producing the highest yields. The new paradigm is managing for efficiency.

“Eight years ago, yields drove the ship. Anybody with higher yields was viewed to be more profitable. Frankly, today, it’s more about reducing input costs while maintaining yields. That’s the way to be more profitable today,” Naeve says.

Back in 2006, the world record soybean yield of 139 bushels per acre (bu/ac) was set by grower Kip Cullers in Purdy, Miss. Soon after, soybean prices were soaring.

“He (Cullers) became an evangelist around high-input systems and driving high yields through inputs, or what I’d call ‘buying your way’ into higher yields. Then we started to see prices run up, and

that’s when people got really excited about this bandwagon,” Naeve says.

Product promoters soon jumped on board, saying they had a product that would give two more bushels in the yield. “‘It’ll only cost $14 an acre and you’re stupid not to buy in,’ was the typical sales message,” he says.

“It’s the same game we’ve had in agronomy forever, but it just got much, much more intense during that upswing through 2014. I think it’s just a confluence of cultural events and the fact that farmers hadn’t been doing a lot with soybeans. A lot of U.S. farmers had a lot of experience with really highly managed corn, and treated soybeans as a secondary crop.”

Responding to that pressure, Naeve and other researchers in several states began investigating the new claims.

These days, Naeve says, the average yield in an Iowa soybean crop is about five bushels ahead of Minnesota. Both northern Minnesota and southern Manitoba yields have been close to 40 bu/ac. Individual fields in Minnesota get into the high 40 bu/ac fairly often, and

A new 3 year survey has captured data on fertilizer use from 3,292 Canadian growers who have completed the online survey detailing fertilizer use practices on 8.3 million acres of cropland.

AVERAGE FERTILIZER RATES FOR FIELD CROPS IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC

sources of nitrogen fertilizer for corn

GROWERS MORE FAMILIAR WITH THE 4Rs ARE MORE LIKELY TO ADOPT 4R BMPs

58% of farmers report ag retailers and 41% cite Certified Crop Advisors (CCA) as sources for 4R information.

Let’s break down the corn nitrogen and phosphorus application and consider timing and placement

FOR CORN IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC

In 2016, over 60% of P fertilizer applied for corn in ON and QC was placed in subsurface bands, and only 9% was broadcast without incorporation.

This is just a snapshot. More information can be unearthed in the full survey results. Visit www.fieldprint.ca to view the survey summary or request the full report.

Thanks to our supporters for making this work possible: Canadian Canola Growers Association, CropLife Canada, Fertilizer Canada, Grain Farmers of Ontario, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, and Pulse Canada.

This initiative has been made possible through Growing Forward 2 a federal-provincial-territorial initiative.

60-plus bu/ac yields do occur as exceptions.

It may be tempting to push for 60 or more bu/ac, but the research doesn’t support the effort, he says. For several years, colleagues at universities in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, Arkansas, Kansas, Michigan and Wisconsin joined with Minnesota to investigate products that might improve yields.

“Invariably, we’d find a lower return on investment (ROI) or a lower yield than claimed by whatever company was producing the product. The companies [suggested] the idea that multiple products would provide synergistic results. So, in this national study, we threw everything at the wall together. We had a bunch of individual treatments, and then we put everything together to see if there really was any synergy.”

In the northern states, there were “significant yield increases” in 15 of the 21 siteyears. Trials were conducted from 2012 to 2014.

The core package was a replicated and systematic set of optimized, yield-enhancing applications. Sites had a fungicide seed treatment (ST), a fungicide ST plus an insecticide ST plus a nematicide and biological ST plus a LCO (Lipo-chitooligosaccharide) seed treatment. Other trials had added nitrogen in various forms, a defoliant (Cobra), a foliar fertilizer, foliar fungicide and insecticide and an antioxidant (BioForge).

The applications were all compared to yields from an untreated control and were analyzed for ROI.

At the northern sites, the average plot yield was 61.2 bu/ac. Ten of the 15 siteyears had treatments that gave a statistically significant yield increase, ranging from a yield of 63.6 to a maximum of 68.5 bu/ac.

The additional cost per acre for these treatments ranged from $8.75 for a fungicide seed treatment to $171 per acre for a combination of all yield-promoting products.

The additional cost was weighed against three yield returns and soybean prices. At a price of US$8.90 per bushel, only one of all the treatments showed a potential break-even with a 45-bushel yield, a foliar insecticide treatment. According to Naeve, if the yield went up to 60 bu/ac, the foliar fungicide plus insecticide application also would probably break-even.

The next “best” for economic efficiency was the seed treatment with fungicide, insecticide and Bio-Forge, at a 50 per cent

probability of a return on investment with a 60-bushel yield. Following that was the single fungicide seed treatment for a probable positive ROI.

“The biggest thing farmers have to recognize is that these products that are sold as yield enhancers, in my view, are very rarely able to produce the yields expected. The farmer’s primary job is to protect the yield potential that’s in that seed.” Naeve says.

But, the soybean scientist also admits, there are or may be exceptions. For instance, he says, “We may not know all of the actual pests. Fungicides do have activity in soybeans, and do increase yields in some environments. Even though a pathologist may not see a disease, it’s my belief that the fungicide is affecting something. It may be protecting the plant from disease at a low level, and thus affecting yield – but it’s not some magical yield enhancement.”

Naeve provides two examples: The research showed a little more yield response when premium seed treatment included an insecticide. It was a very marginal response but it fit with other research. It only had a positive ROI however, at yields of 75 bushels per acre, with soybeans at $8.95 per bushel.

Second, among foliar treatments, research would sometimes show a benefit to pairing an insecticide.

“That was only because we had aphids in those fields occasionally. The populations were below the integrated pest management thresholds, but there was an ROI benefit because the insecticides are really cheap. Foliar insecticides tend to work well because they’re super, super cheap and highly effective on insect pests,” he says.

Two other exceptions in Manitoba and northern Minnesota may be manageable. One is a seed treatment.

“It seems like fungicide seed treatments have good activity for a couple weeks, and there is a kind of sweet spot for benefits. If it’s cool when you plant and get a little shot of rain, and the soybeans emerge after 10 to 14 days, then we can pick out a little yield benefit,” Naeve says. “In really good conditions, we don’t see any benefit. If emergence is really delayed, we don’t see a benefit. There is something in the middle, but it’s really hard to predict. Your best option is to order treatment for only part of the seed, then utilize it as you need it, depending on conditions and the forecast.”

The other exception is at the start of podding. “You have a better chance of

getting a positive ROI from foliar fungicides where you get good canopy closure, tall beans, and really good growing conditions at the beginning of podding. Then, if you think you have very good yield potential, that’s the time to protect that yield with a fungicide. Don’t blindly buy fungicide in the fall with a plan to apply it to every field.”

The Minnesota soybean specialist suggests growers consider two approaches to crop management: the “input-based” and the “acre-based” or “intensive” management.

“Input-based production is illustrated by the farmer who goes to his local co-op in late fall or early winter and orders all of his product for the next year – the seed treatment, fungicide, insecticide, and maybe some other product – then puts those on a schedule for applications in the next season,” Naeve explains.

“Acre-based production is issue-oriented: I have a disease or issue in my field, therefore I need to control it. I see an issue while I’m out scouting, and I fight it with a certain product. Those choices tend to have a higher probability of return.”

Naeve adds that active management requires visual scouting, soil sampling and perhaps remote sensing. It counters the trend to one-size fits all on large farms.

“The big trend in agriculture is to move towards larger farms, with fewer people managing them. Farmers are managing more distant fields with less time and bigger machines. They tend to do a lot of rubber stamping and make one system work on everything. That approach is efficient for a number of acres, but it isn’t efficient in terms of the dollars invested in the products,” he says.

As well, it may be leading into new problems. “Insecticide seed treatments give us a little yield benefit, but they have an environmental cost. We’ve seen a lot of resistance build up in insects. In northwest Minnesota, we now have pyrethroid-resistant aphids. Repeated use of these insecticides will break down the effectiveness and cause huge problems,” he adds.

So, what’s the “novel” part of what he’s learned from the field research and applications in Minnesota? Naeve says, “The novel part is in being a good manager, going back to basics and scouting and working for those soybean yields instead of trying to just buy yourself higher yields. I call it proactive management.”