TOP CROP MANAGER

TO OUR ATTENDEES, PRESENTERS, SPONSORS AND EXHIBITORS

GOLD SPONSORS

SPONSORS

TO OUR ATTENDEES, PRESENTERS, SPONSORS AND EXHIBITORS

GOLD SPONSORS

SPONSORS

4 Evaluating root rot in pulses

Presented by Syama Chatterton

8 Investigating PGRs

Presented by Sheri Strydhorst

12 PGRs on spring wheat

Presented by Amy Mangin

14 New (old?) insect threats and the “old guard” of beneficial insects

Presented by Tyler Wist

18 Fertilization to improve crop quality and health

Presented by Jeff Schoenau

21 Tackling clubroot

Presented by Dan Orchard and Curtis Henkelmann

25 The future of neonics

Presented by John Gavloski

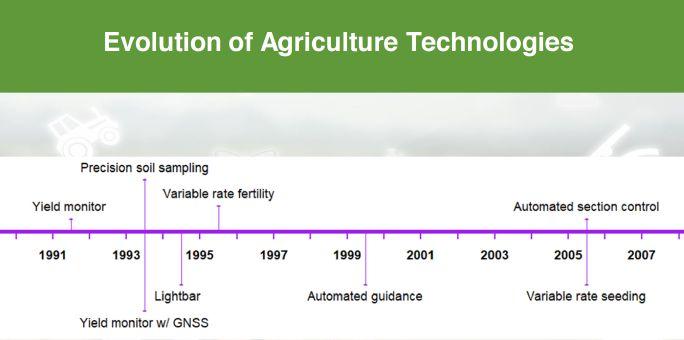

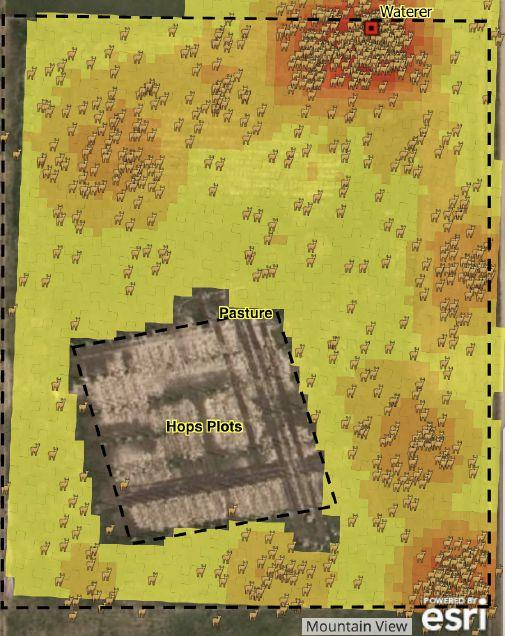

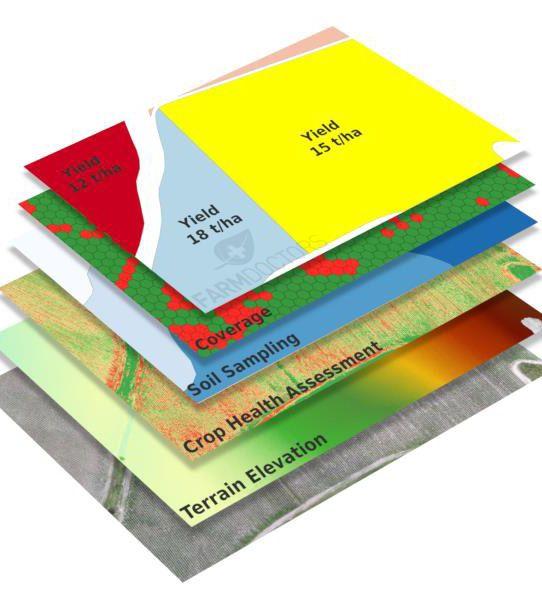

29 Smart farming and glimpses into the future

Presented by Joy Agnew

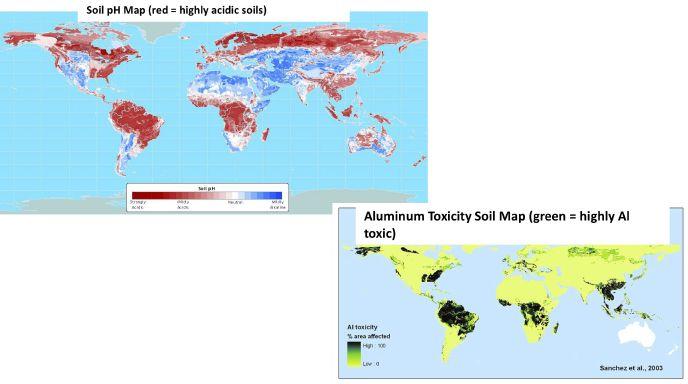

33 Next-generation technologies for tomorrow’s crops

Presented by Leon Kochian

35 Maximizing fungicide use

Presented by Tom Wolf

as part of Top Crop Manager, May 2020, by Annex Publishing & Printing

PO Box 530, 105 Donly Drive South, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 Canada Tel: (519) 429-3966 Fax: (519) 429-3094

Editorial Director, Agriculture: Stefanie Croley

Associate Editor: Alex Barnard

Western Field Editor: Bruce Barker

National Account Manager: Quinton Moorehead

Publisher: Michelle Allison

Group Publisher: Diane Kleer

Media Designer: Curtis Martin

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Welcome to Top Crop Manager Focus On: Plant Health. This is the first of our summer digital series, comprising the presentations and reference materials used at the 2020 Plant Health Summit, hosted this past February in Saskatoon. Our fifth annual research summit brought together nearly 300 producers, agronomists and crop science consultants, scientists and industry representatives over a day-and-a-half of discussions, audience engagement, networking and knowledge sharing. If you were lucky enough to be there, perhaps these proceedings will jog your memory. And, if you missed it, you’ve got the next best thing right here.

This year, instead of our typical video interviews with the speakers, we’ve taken a different spin on coverage with a series of podcast episodes featuring exclusive speaker interviews and snippets of their presentations. Your first access to the podcast episodes are at the links below, and you can find all of our previous episodes of Inputs – the Podcast by Top Crop Manager on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. You can also check out a video highlight reel of the event here. Thanks to our esteemed presenters for sharing their knowledge and studies with us.

Happy reading – and listening.

@TopCropMag

/topcropmanager

Did you miss the Plant Health Summit? Our podcast episodes linked below feature exclusive speaker interviews and presentation snippets. Visit agannex.com or tune in below.

Fertilization to improve crop quality with Jeff Schoenau

Smart Ag with Joy Agnew

PGRs with Sheri Strydhorst and Amy Mangin

Beneficial insects and neonics with Tyler Wist and John Gavloski

Stubborn diseases and management strategies with Syama Chatterton, Dan Orchard and Curtis Henkelmann

Getting to the root of global food security with Leon Kochian

Fungicides and spray technologies with Tom Wolf

Exploring Aphanomyces research and the role its accomplices play in driving disease.

Presented by Syama Chatterton, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020.

The root rot problem really exploded in about 2011-2012. Most pathologists were under the assumption that it was Fusarium root rot. But we saw that a lot of things didn’t add up, particularly with the symptomology.

Fusarium root rot tends to cause blackening of the tap root and it doesn’t usually extend into the lateral roots. Instead, in the field, we were seeing roots that were totally decayed, often with complete loss of the lateral roots along with honey-brown and black discolouration.

We were also seeing widespread damage in some fields. Generally, Fusarium root rot doesn’t do this, so we knew that there was something else going on. What we found was an unexpected surprise – the pathogen Aphanomyces euteiches. It causes very distinct symptoms on roots and a honey-brown discolouration. The most telltale symptom is pinching of the epicotyl, and then often what happens is Fusarium comes in afterwards, really making symptoms difficult to diagnose.

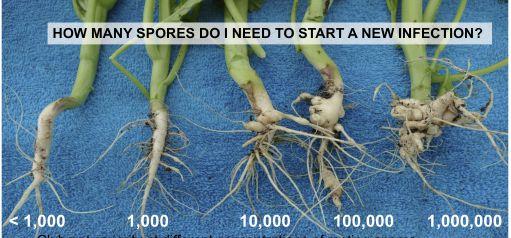

Aphanomyces was reported for the first time in Saskatchewan in 2012 and in Alberta in 2013. Large-scale surveys across Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba were conducted to look at the prevalence of Aphanomyces root rot, and to also look at what other pathogens were involved. The surveys from 2014 to 2017 found that Aphanomyces was widespread across the Prairies. The hypothesis is that it is a native pathogen; it’s in the soil. After extensive production of pea and lentils – fields with a history of 20 to 25 years, even with a pea or lentil once every five years – the inoculum increases above threshold causing these pulse crops to get the disease.

In Alberta over the past five years, prevalence of Aphanomyces was between 40 to 50 per cent of the fields surveyed. The survey period had really wet years and really dry years, and for the most part, prevalence and incidence went up and down with moisture. In Alberta over the last few dry years, about 30 to 40 per cent of fields were positive. Unfortunately in Saskatchewan, there were peaks in 2015 and 2016 around 65 to 70 per cent

Aphanomyces prevalence, down a little bit in 2017 and 2018 at about 40 per cent prevalence, and then, for some reason, in 2019 it was the worst that we have seen yet with about 90 per cent of fields showing positive symptoms. Precipitation in 2019 was a weird year. The average precipitation wasn’t really reflective of what happened in the season, because it was dry in the spring, and plants were stressed. Then with rain later in the spring, it got so wet that Aphanomyces was able to infect in July. Because the plants were already stressed, the disease really took off.

Root rot is a complex. Aphanomyces is our A-list pathogen, but there are some other pathogens that are also contributing to the problem. There are Pythium species and Rhizoctonia species, and many different Fusarium species. For Alberta, between 10 and 90 per cent of the fields are positive for these pathogens. Saskatchewan and Manitoba are virtually the same story.

The other issue is that Fusarium is also a problem on its own. Some fields only have Fusarium root rot, some fields have Aphanomyces plus Fusarium root rot, and a few fields have only Aphanomyces. In Alberta, Aphanomyces is almost always occurring with Fusarium. In Saskatchewan there is more of a balance of 50/50 Fusarium and Aphanomyces.

We tested pea and lentil in the greenhouse and found they are equally susceptible to Aphanomyces. The symptoms on lentils are virtually the same as they are on peas. But in the field, particularly in dry years, lentils seem to be less impacted.

My lab research is conducted in the context of current management recommendations. A big portion of my research that I started four or five years ago is trying to come up with a risk quantification system so we can build some sort of decision support system based on soil testing.

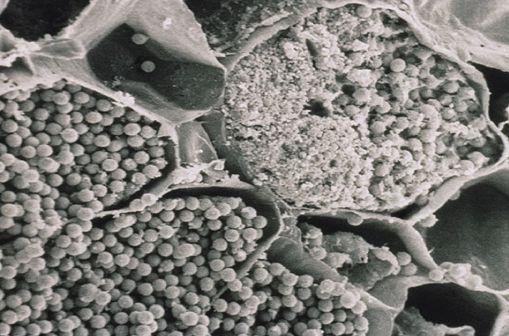

The amount of inoculum that is required to cause disease is the foundation of any sort of risk quantification system. In order to do that, we are trying to measure the oospores in soil, which are the thick-walled resting spores. This is where we’ve run into some challenges. The thick cell walls means they don’t like to be cracked open so that we can test how much DNA is present.

In our research, we looked at the number of oospores per gram (oospores/g) of soil. At low levels, the pea plants were pretty healthy, but at 100 the plants looked very diseased. One hundred oospores isn’t good news because that’s a very low threshold level.

We also found different threshold levels for different soil types. Clay loam had the highest threshold level at 275 +/– 36.5 oospores/g, which is not what we were expecting, because we often see that disease is worse in these heavy clay fields. I think it has something to do with the water-holding capacity of the clay: it holds more water, so even though the threshold dose is higher, it tends to stay wetter for longer. Loam (98.8 +/– 42.9), Sandy Loam (81.3 +/– 76.7) and Silty Loam (44.3 +/– 38.3) had lower threshold levels.

The other research we are working on is using DNA tests to quantify the pathogen level and determine what the risk is. We compared measured oospores using DNA testing versus actual oospores/g of soil. The correlation was pretty good for sandy loam soils, less so for silty loam, but not very good for clay loam soils. For example, for clay loam, the DNA test is telling us there are about 10 oospores but the actual number of oospores is 100. This makes it difficult to test soils that are just at or below that threshold.

We took this comparison to the field and compared the same soils in the greenhouse with DNA testing. In the field soils, we find an average percent incidence of Aphanomyces of about 80 per cent. Our average disease severity is 4.2, and estimated about 1,000 oospores per gram of soil. In the greenhouse, we had very similar results.

But when we look at two different types of DNA testing methods, the DNA measurements were only detecting about 50 per cent of soils positive for Aphanomyces. The two DNA methods estimated 281 to 313 oospores/g of soil, but there was a huge range from 7.6 to 2,300 oospores/g. It’s the number of false negatives that are coming back from the DNA tests that is a challenge, and we’re working really hard on trying to improve that.

The other problem is that we’re underestimating the amount of Aphanomyces with DNA testing because of those multiple pathogens that are interacting together. So, we are also working on trying to make a multiple pathogen detection system, both for Aphanomyces and Fusarium, and that gets a little bit complicated, although I think we’re making progress.

We’re doing field trials to assess our current recommendations to growers. The first is to consider using a seed treatment that targets

the root rot complex. It wasn’t really clear which ones would be effective against Aphanomyces or whether there are any that are effective.

We tried a number of different seed treatments – some of them confidential – so I can’t the share the trade names. We also tried trifluralin pre-seed because there had been some reports of literature in the early ’90s that it had some effect on Aphanomyces root rot. The problem is that we couldn’t incorporate trifluralin in no-till fields so we were just applying it to a heavy crop residue. We also tried Phostrol as a foliar spray to the seedlings. There had been some previous research out of Washington that had shown this might be effective. Long story short, there was no effect of most treatments over four years at four locations.

The other recommendation we are looking at is whether a six-toeight-year rotation away from peas and lentils is necessary because it is a bit of a guess based on what is in the literature. We wanted to see if that recommendation was different under Prairie conditions. And, are there other pulses that you can grow in these infested fields without increasing your risk?

We looked at infected fields to see how long the rotation has to be out of peas before they can be rotated back into the field. One of those fields was at Red Deer in the Black soil zone. The last time peas were grown on this field was in 2011. In 2015 and 2016, there were still fairly high disease severities of around 6 on a scale of 0 to 7. Disease severity starts to come down in 2017, and then was quite low in 2018 at just above 2. By 2017 and 2018 there were some fantastic yields at this site around 95 bushels per acre (6,408 kg/ha). As disease severity was going down, yield was coming up. This indicates that maybe the six to eight year rotation recommendation is correct.

Contrast that to a site in southern Alberta at Taber. The last pea crop was in 2014, but over the past five years there hasn’t been a reduction in the disease severity – still between 4 and 6. The last three years have been very dry, but we haven’t seen the disease severity go down. The yields are much lower than what we saw up at that Red Deer site, as well.

The other thing that we looked at in Taber is how the pathogen composition is changing over time. Particularly we wanted to see what was happening with Aphanomyces and Fusarium. We took root samples in June, and the Aphanomyces levels were quite high on the roots, but the Fusarium levels were quite low. In July, the Aphanomyces levels on the roots were quite low, and the Fusarium levels went up. This shows part of the issue with surveying is that a lot of surveys

are done around flowering in mid-July and we’re missing Aphanomyces. I think that’s another reason why we saw Aphanomyces explode over the Prairies. A good survey time for Aphanomyces is in June about six weeks after planting if you’ve had a good rainfall.

A new rotation study was started in 2018. Each site has a different break of one to five years since the last pea crop depending on when the producer last grew peas. In these rotation trials, cereal and canola were included as standard rotational crops. The trial gives us one- to eight-year breaks between a pea crop, with or without an alternate pulse crop in the rotation. The alternate pulse crop at Swift Current and Lethbridge was chickpea, fababean at Saskatoon and Lacombe, and soybean at Redvers, Brooks, and Morden.

The roots of peas and the alternate pulse crops were assessed for their pathogen levels. We also wanted to see how the soil inoculum potential changes with the different rotation lengths and different pulse crops. Soybean tells the best story with no Aphanomyces and even very, very low Fusarium levels on roots. But peas had very high levels of Aphanomyces, so, I think soybean can be a very good alternate crop to pea. With fababean the picture becomes a little less clear because at the Lacombe site, the disease levels had really come down in 2019. In 2020 we’re going to add peas back into the rotation and see how quickly the inoculum builds up. At the Saskatoon fababean site, the Aphanomyces root rot levels were fairly low on pea, but there were higher levels of Fusarium colonization on the roots. On fababean, Aphanomyces colonization was very low, and it isn’t as favourable of a host to Fusarium species either.

For chickpea, we saw very low root rot at Taber and Swift Current with Aphanomyces or Fusarium. At Taber, Aphanomyces colonization is higher on pea than chickpea, but Fusarium levels are much higher on pea. At this stage in the research, it appears that soybean and fababean could be good pulse crop options for managing Aphanomyces, and we’re still waiting to see if chickpeas might be a good option as well.

Differences in crop and variety reaction to Fusarium spp.

We also did some pathogenicity tests with F. solani and F. avenaceum on soybeans, fababeans, chickpea, red lentils, and Meadow pea. The first thing to note is that soybean, CDC Consul chickpea, and red lentil HAD pretty good emergence, even in the presence of F. solani. The disease severities for these were also all fairly low. The other chickpea varieties, Cory and Leader, and Snowbird fababean had lower emergence levels. Interestingly, CDC Orion did not even emerge when F. solani was present. Clearly, with chickpeas and fababean, a seed treatment should be used.

With F. avenaceum, there was a similar story. The soybeans had very good emergence with very little disease severity. The fababeans had poor emergence and fairly high disease severity, but it’s interesting that we see this in the greenhouse, but not out in the field. Chickpeas and red lentils also had poorer emergence but the green lentil variety Impower had good emergence and low disease severity. This shows the complications of all these different pathogens and how they work together and the importance of seed treatments for targeting Fusarium species.

Brassica cover crops have been shown to have great biofumigation potential in the greenhouse, except for canola because the biofumigants have been bred out. Biofumigation is not like a seed treatment where it only works for four weeks. The cover crop could reduce oo-

spore levels and bring that threshold down. In our field trials, we are looking at mustards and some other Brassica crops. Originally we tried two years of shoulder season cover crops planted after harvest in late summer/early fall. But the weather was either very dry or it snowed in September so we didn’t achieve a very competitive cover crop. As a result, the whole project was revamped and we’re looking at a full season cover crop to see if it works, and then we’ll figure out how to fit it into a cropping system. The cover crops being investigated are oats, rye, two mustards, fababean, clover and five different blends of Brassica crops that include mustards, tillage radish, Dwarf Essex rape, forage collards, forage rape, turnip rape and forage kale.

The cover crops are terminated as green manure with a flail mower. The biomass is removed, weighed and put back on the field, where one-half of the plot is tilled. Pea will be seeded into this cover crop footprint in 2020 and differences in root disease will be assessed. We are also trying to quantify the oospore numbers in the soil before and after cover crops, with and without tillage. Then we’ll repeat it so we have two years of data.

Another research project is looking at using legumes in a cover crop mix since this is becoming more popular with farmers. We planted vetches, clovers, lupins and peas in the field, and tested them for presence of Aphanomyces and disease severity. The vetches were very susceptible to Aphanomyces. Some clovers (Crimson, Yellow blossom, Persian) didn’t get a lot of disease, but they can support Aphanomyces. Other clovers (White Dutch, Red, Subterranean, Berseem) didn’t get the disease at all, and they didn’t support Aphanomyces colonization. Lupins didn’t support Aphanomyces either.

Liming is a potential tool because calcium is very important in preventing oospores from germinating into zoospores. It’s very widely used in the U.S. in sugar beets to manage Aphanomyces root rot. Here, it might have potential for sugar beets or in systems where tillage can incorporate the lime. Liming may also have an impact for about five years, and it can help prevent clubroot of canola.

We did a greenhouse trial with soil from our Taber site and mixed different lime products at four different rates. Hydrated lime reduced disease severity with decreasing severity as the rate increased. Quick lime and ZeroG lime weren’t as effective, so there may be differences in the calcium availability of the products.

There was also an increase in root weight as the hydrated lime rate increased. Quick lime had some increase in root weight with increasing lime rates, but ZeroG did not have a significant increase. Our next step is to try and take this out into field trials and see if we have the same results as in the greenhouse.

Multiple modes, multiple rates and multiple species. Which combination is a winner?

Presented by Sheri Strydhorst, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

I’m going to focus my information on plant growth regulator (PGR) options, and mostly on gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitors. Gibberellin is a type of plant hormone that makes plants taller and skinnier. Gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitors prevent this taller growth. The only gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitor registered in Canada has the active ingredient chlormequat chloride (CCC) with the tradename Manipulator, and at this point, only on wheat. It was registered for use by PMRA in 2015, but it wasn’t until April 2018 that the EPA in the U.S. approved a maximum residue level (MRL) for CCC. Manipulator is registered in all of Europe, Australia and most wheat-producing countries.

Another gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitor is trinexepac-ethyl (TXP) under the trade name Moddus from Syngenta. It’s registered for use in many countries, and there are MRLs in place in the European Union, the U.S., and Japan. It was submitted to PMRA for registration in 2017, but it is not yet registered in Canada. A registration decision may be provided later in 2020 for hopeful product use in 2021.

Another PGR with a very different mode of action, Ethrel, is registered in Canada. It increases ethylene production and staging is incredibly particular or crop losses can occur. Bayer makes you sign a waiver before you use it. Application timing is when most of the tillers are between early flag leaf emergence to swollen-boot stage (Zadoks stage 37 to 45).

Growth stage 37 is when the flag leaf is fully emerged but really tightly rolled. Growth stage 39 is when the flag leaf has unfolded, and is when you want to target application. At growth stage 45, which is late boot, you can see the swollen sheath where the head is pushing out of side of the sheath. Growth stage 49 has the first awns visible. The label on Ethrel says, “Do not apply Ethrel after 10 per cent of the awns have emerged.” If you count 10 plants and two of them have awns emerged, this window is closed. The label of Ethrel also states that “Correct timing is critical for successful results and to ensure crop safety.” If this product is new to you, be scared of it.

Research has documented some of the risks of PGRs. PGRs will not eliminate lodging in highly susceptible crops but may delay the onset of lodging. If lodging was originally going to happen at the end of July, you might delay it until mid-August, which could be beneficial.

When to apply GA inhibitors? Best is a single application at GS 30-32

The label of Manipulator states that you can apply Manipulator anywhere between growth stage 12 and 39. So, that’s the two-leaf to the flag leaf stage, but if you want to be really effective with Manipulator, you want a single application between growth stages 30 to 32. Growth stage 30 is the beginning of stem elongation. To determine these growth stages, you need to pull out plants, and split the base of the stem open. What you’re looking for is one centimetre (cm) of growth between the basal node and the first node. That’s the sweet spot for spraying Manipulator or Moddus. The end of the sweet spot is growth stage 32, defined when node two is at least two cm above node one.

In the absence of lodging, research has found variable effects on yield – sometimes a yield increase, sometimes a yield decrease, and sometimes no impact.

PGRs can also affect other hormones in the plant, and result in developmental and physiological changes. Green colour of the foliage can be intensified, and this can result in slower maturity.

The optimum temperature for gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitors is around 5 C, but it’s very possible to have a 3 C morning in early June when you’re out there spraying. That is not the optimum temperature for PGR application.

Height reductions may also be only short-term. Two weeks after a PGR application, we can see beautiful height reductions, but by the end of the season, it can be surprising that it is the same height. Sometimes the crop is taller and sometimes it’s only a centimetre shorter. We’ve seen a lot of inconsistency.

PGRs can also result in the production of late, unproductive tillers. Those may not make it to maturity and are going to cause harvest headaches. Reduced grain weight has also been very frequently documented.

PGRs should also be used with caution under environmental stresses. The label for Ethrel states, “Do not use under drought,

excessive moisture, or excessive heat.” The Manipulator label says, “Don’t use under waterlogging, drought, or nutrient deficiencies. In hot, dry weather a better result may be obtained from application in the early morning or evening.”

We’ve done a number of field trials, and have seen yield reductions, mainly when soil moisture content is 10 per cent or less, or when the humidity is quite low at less than 50 per cent. I think in these situations where you have hot, dry conditions at the beginning of June, Mother Nature is going to be your PGR because if you have drought, you don’t need a PGR.

I really like this quote by Wilhelm Rademacher in regards to his research on PGRs that, “The risk of lodging is strongly affected by variety and husbandry factors including sowing date, seed rate, drilling depth and rate of nitrogen application.”

A fairly old study in Indiana in 1988 looked at PGR application

improve standability.

Conversely, AAC Redwater lodged 67 per cent of the time but Manipulator did not significantly improve standability. Based on this data set, I wouldn’t necessarily recommend applying a PGR on AAC Redwater.

We looked at six different CPS varieties. AAC Crossfield, AAC Foray VB and SY Rowyn lodged fairly frequently and PGRs helped with standability. With AAC Crossfield though, the PGR only helped out 50 per cent of the time. AAC Penhold though did not lodge at all. It’s a variety that has some really good genetic standability, so we didn’t need a PGR on that variety, based on our research trials.

In terms of the take-home message for the interaction between cultivars and PGR response, for CWRS we’re fairly confident that AAC Brandon, AAC Elie, and Thorsby would be a good choice for varieties to use Manipulator on. These are the most responsive varieties but you won’t see a benefit 100 per cent of the time.

In the CPS class, AAC Foray and SY Rowyn would be the variet-ability, and AAC Crossfield, in the Alberta environment at least, we get fairly severe lodging but only a 50-50 chance that a PGR would actually help. I do want to put the caveat out there that not all cultivars have been tested, and different cultivars will respond differently in different environments in Western Canada. So, it is

stood beautifully with or without PGRs. The message is that nothing is textbook with lodging and PGRs. We can’t necessarily have a nice set of rules and just apply them directly.

In the Alberta research, we looked at 11 different CWRS wheat variety responses to Manipulator over one to two years. Three varieties, AAC Brandon, AAC Elie and Thorsby tended to lodge frequently, but also responded to PGRs. AAC Brandon lodged 83 per cent of the time, and Manipulator made it stand better 80 per cent of the time. AAC Elie lodged 100 per cent of the time, and 100 per cent of the time Manipulator made it stand better. Thorsby lodged 100 per cent of the time, and 100 per cent of the time a PGR did

Barley certainly is a crop that has standability issues, but at present, no PGRs are registered on barley. [Editor’s note: Manipulator was approved for use on barley in May 2020.] Ethrel was registered but

Our research on CDC Meredith barley showed a little bit of heightcation produced a beautiful height reduction, and it carried on quite nicely throughout the growing season. Manipulator doesn’t seem to be the right product on barley. Moddus looks good, but a higher rate than what is recommended in wheat is required on barley.

Cultivar-specific responses also complicate PGR use in barley. A 1977 study in Ontario looked at the response of 53 different barley cultivars to chlormequat chloride (the active ingredient in Manipulator). Thirty-three had a height reduction, five had no height reduction, and 15 varieties were taller. What works on one cultivar isn’t necessarily going to apply to others.

Research by Laurel Thompson at Lakeland College looked at how CDC Austenson feed barley, and CDC Copeland, AAC Synergy, and CDC Bow malt barleys responded to Moddus application.

Trinexapac-ethyl (left), Manipulator (centre) and no PGR (right), on CDC Meredith barley at Barrhead, July 5, 2016 – 22 days after PGR application. PGR was applied June 13 at BBCH 31-32.

With CDC Austenson (good lodging resistance) at Barrhead in 2019, lodging was just as bad with or without a PGR. This is a great example where a PGR will not prevent lodging in all conditions when you have that perfect storm for lodging with high fertility, a cultivar that tends to fall over, and favourable growing conditions.

On barley, the take-home messages are that to date, no PGRs are registered and a higher rate of Moddus will be required. I want to highlight that when you have a variety like Amisk barley with really good standability, you don’t need a PGR. The magic bullet to prevent lodging is to use cultivars that have great genetic standability rather than depending upon a PGR.

Oat and PGRs

We’ve done a little bit of work on oats, although PGRs are not currently registered. [Editor’s note: Manipulator was approved for use on oats in May 2020.] With Manipulator, we saw an eight per cent height reduction, a 13 per cent height reduction with Moddus, and when we tank mix the two actives we get a 25 per cent height reduction. We did a little bit of work on different oat cultivars: AC Morgan, CDC Norseman, ORe5342M, OT3085, Summit, and Triactor. Five cultivars had height reductions, four cultivars had improved standability, four had reduced bushel weight, and three had improved yield. Again, this cross-species trend of “not all cultivars respond the same” is an important message.

On field pea, we looked at Ethrel, Manipulator, and Moddus. There

were very small, very inconsistent results. We also found that under dry conditions and peas under stress, our pea yields were cut in half.

A very common trend in Europe is to tank mix Manipulator and Moddus for improved performance. Manipulator works earlier in the gibberellin biosynthesis pathway and Moddus later. A tank mix can improve performance and consistency, however this option is not registered in Canada. In our research on wheat, the frequency of height reduction with Manipulator alone was 67 per cent, Moddus alone was 22 per cent, and tank-mixed together was 78 per cent of the time.

We also tended to get larger height reductions with the tank mix. Again, there were differences in standability response between cultivars where Manipulator worked quite well by itself on AAC Viewfield, AAC Wheatland VB, CDC Landmark VB, and Stettler, and the tank-mix (which is not yet registered) worked better on AAC Brandon, CDC Plentiful, AAC Foray VB, and AAC Goodwin.

In summary, we need to remember that PGRs will not eliminate lodging in highly susceptible crops. For wheat, Manipulator seems like the best options and is the only product currently registered. It works fairly well on AAC Brandon, AAC Elie, Thorsby, AAC Foray VB, and SY Rowyn. In other crops, no PGR is currently registered. Our barley research found Moddus is the PGR of choice, but we need to use a higher rate than the wheat rate. On oats, Moddus or Manipulator may be good choices. On peas, just don’t spray PGRs on them because there’s more risk than gain.

Evaluating different varieties, nitrogen rates, sources and timing.

Presented

by

Amy Mangin,

University of Manitoba, at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

My overall project is called “Agronomic Strategies to Minimize Lodging Risk While Maximizing Yield and Protein Content in Spring Wheat” and it was done for my PhD thesis. I looked at different varieties, different nitrogen rates, sources, and timings, as well as seeding rates and plant growth regulator applications. Today, I’m going to focus on the plant growth regulator treatments that were within these trials, which ran in 2018 and 2019 at Carman and Manitou, Man. In these trials, Manipulator was applied at the single application rate of 0.7 litres per hectare and compared to an untreated control. Application was at growth stage 31-32, and this typically fell around the second week in June.

The overall project looked at three main objectives: how agronomic management treatments affected yield components, nitrogen dynamics, and lodging risk of spring wheat. Over the two years, our sites fell well below the long-term average growing season precipitation from May 1 to September 1. The 2019 site years had the lowest growing season precipitation of the two years, and also came off of a dry fall from 2018. That led to lower than normal yield potential at those sites and also low lodging pressure.

Overall, we saw significant yield increases with Manipulator in two of four site years at Carman and Manitou in 2018 at around two to five bushels per acre. Yield at Carman 2018 with Manipulator was about 85 bushels per acre and about 75 bushels per acre at Manitou 2018.

the four sites – the two 2018 sites, as well as Manitou in 2019. The increase was likely a combination of increased spikes per acre and also increased kernels per spike (decreased floret abortion). We probably saw resources being reallocated and repartitioned from stem growth towards the developing head at that time.

We saw a decrease in kernel weight at every one of our sites, regardless of the yield response to Manipulator. The decrease in kernel weight was likely due to the increase in demand for resources across more kernels in these dry years. The grain fill period was shorter and with more kernels to fill, the plants actually didn’t have time to fill the kernels – resulting in lower grain weight.

When I say “nitrogen dynamics,” I mean dynamics within the plant –when is the nitrogen taken up, where the nitrogen is within the plant, and how it is moving to form final grain nitrogen (protein) content. In spring wheat, about 60 to 90 per cent of nitrogen is taken up by anthesis and stored as vegetative tissue of stems, leaves and chaff. After anthesis during the grain fill period, some of that nitrogen is remobilized and moved into the head, to make up grain protein content. Looking more in depth at stem tissue, research has classified that 60 per cent of the nitrogen in stem tissue was from reserve pool nitrogen. It didn’t actually serve other functions in the plant, such as structural, metabolic, or transportation functions.

We looked at how some of our agronomic management practices influenced this relationship of when the plant took up nitrogen and how it moved within the plant. We separated the plants into stems, heads, and leaves, analyzed them for nitrogen content, and assessed the movement from anthesis to maturity.

Overall, grain protein content was high across these four sites because of the dry growing seasons, ranging from about 13.9 per cent to about 14.2 per cent in the untreated plots. With Manipulator application we saw a decrease in grain protein content regardless of a yield increase. That decrease couldn’t just be attributed a dilution effect from nitrogen being spread over more yield. We saw some of the largest protein decreases at sites that we didn’t have a yield increase.

Spring wheat yield is typically made up of three main components: spikes (plants and tillers) per acre, kernels per spike (spikelets per spike and kernels per spikelet) and kernel weight. Looking at the three main yield components helps to unwrap why or how these yield increases came about. Spike density was counted around flowering time to soft dough. There was a spike density increase only at the Carman 2018 site with Manipulator. This increase in spike density was likely due to increased tiller survival rather than an increase in tiller production. There was an increase in kernel number per acre at three out of

In the untreated plots, we found about 70 per cent of the nitrogen was taken up by anthesis, which is similar to some of the background literature. But the Manipulator application significantly decreased the amount of nitrogen that was taken up in that pre-anthesis period. But by maturity, nitrogen uptake was similar between untreated and treated, so the total nitrogen uptake for the entire season was very similar.

There was a significant reduction in stem nitrogen content. As you would expect, shorter stems mean there is less stem tissue to store nitrogen. There was a similar trend in the leaves and the heads, but it wasn’t significant. At maturity, the majority of the nitrogen had moved to the head tissue, and there were no differences between nitrogen content in any of the plant parts at maturity between treated and untreated plots.

There was a significant decrease in the amount of nitrogen remobilized from stem tissue to the head with a Manipulator application. This could potentially explain some of the differences in protein content, because there is less nitrogen being moved up into the grain. There was a similar trend with leaf tissue, but it wasn’t significant. Overall, around 70 per cent of the stem tissue nitrogen was remobilized across treatments, and around 80 per cent of leaf tissue nitrogen was remobilized.

The two field seasons weren’t great years for lodging because of the dry conditions but I did get lodging ratings for Manitou in 2019. There were a couple heavy rainfall events later in the season when lodging occurred. When lodging occurred, there was an interaction with nitrogen management as well as plant density. When over 140 pounds of nitrogen per acre was applied, there was a decrease in lodging with Manipulator application. And with medium (25 plants per square foot) to high (35 plants per square foot) plant densities, lodging was occurring, and Manipulator was reducing that lodging.

When I tested at anthesis – right after the plant has gone through that rapid stem elongation phase – there was an increase in stalk strength when Manipulator was applied. But when I tested at maturity, there was no difference in terms of stalk strength. So, depending on when you have high lodging pressure conditions, the increase in stalk strength with Manipulator might have been beneficial.

There was a reduced canopy height with Manipulator application at all sites across all varieties. I did see a magnitude interaction between site year and PGR, and cultivar and PGR. This means that the degree of the height reduction was different across the different sites and across the different varieties. For example, AAC Cameron had a greater height reduction than Prosper. Overall the height reduction was about two inches (five centimetres) when measured at soft dough stage. If I had measured at anthesis, I probably would’ve seen a little bit bigger height decreases.

We looked at internode length measured from the second basal internode two weeks after application. We chose that internode because that’s likely one of the internodes where you’re going to see breaking that causes stem lodging. Manipulator did decrease the length of that internode. We also measured the diameter of the stem thinking that if the internode was smaller, we might have thicker stems. There was no difference between treated and untreated in terms of stem diameter with Manipulator.

We also looked at structural root plate – the area of the root core that has thickened, lignified roots. Research has indicated that the area with those thick, lignified roots is really what is providing anchored strength in your wheat crop. It’s not necessarily the amount of total roots, but the spread as well as the depth of that structural root plate.

We dug up, washed and measured a whole lot of roots. At Carman 2018, there was a significant increase in root plate spread with Manipulator, which is something that hadn’t been documented before so we weren’t expecting that. We also saw that root plate depth was increased at three out of the four site years with Manipulator application. Potentially, the resources that were used previously for stem elongation are now being reallocated to root growth and increasing that structural root plate. This means there may be increased anchored strength as well as stem strength with some of these Manipulator applications.

We also look at stem composition by measuring lignin and cellulose, which are thought to have a really good relationship with lodging potential. For lignin, there were no differences between treated and untreated. There was a significant decrease in cellulose content with Manipulator application. We’re still kind of looking into more reasons why we might have been seeing this.

We also looked at stalk strength as a proxy for lodging because in small plots, it’s not always likely that you’re going to have lodging or differential lodging within each treatment. We used a tool to measure stalk strength. Resistance force was measured as the crop was pushed from vertical to 45 degrees from vertical. This was done at anthesis and maturity to see if we could see differences between our treatments.

In summary, grain yield increase happened 50 per cent of the time at two of four sites, but it was at the higher yield potential sites, and the yield increase was only three to five bushels an acre averaged across all of my treatments. That yield increase occurred from increased kernels per acre because we did actually see a decrease in the kernel weight across all sites. So, we saw more kernels, but they were lighter. Grain protein content was decreased at all sites with the treated plots. Stem nitrogen content at anthesis was reduced with the Manipulator application, and that led to reduced stem remobilization of nitrogen. There was a reduced lodging risk with Manipulator application in the high-risk situation of high nitrogen fertility and high seeding rates. Decreased canopy height reduced our plant and stem leverage. We had increased anchored strength at three out of four sites, and we didn’t actually see any differences in structural composition with Manipulator application.

Breaking down the big players in the world of beneficial insects.

Presented by Tyler Wist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

First, let’s define what a “beneficial” is. If it’s an insect helping me, it’s a “beneficial insect.” The beneficials that I’ll discuss here provide biological control, and are further defined as predators and parasitoids.

Western Grains Research Foundation has funded the Field Heroes project. This is a campaign championing beneficial insects. What I’m going to do today is teach you guys what a beneficial insect looks like and what they’re doing in your field, and maybe that will make you more apt to protect them. What Field Heroes is trying to do is to take away that “nothing to lose by spraying” mindset. If you are on Twitter, you can follow Field Heroes, @FieldHeroes and you can find it on the web at www.fieldheroes.ca.

No talk on beneficial insects is complete without talking about – I call it “#AAFCbugbook,” because this name is super-long to say – “Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada.” It’s available in print or you can download it from the Prairie Pest Network Monitoring Blog.

The Prairie Pest Monitoring Blog is a great way to get information on insect pests and beneficials and you should all sign up to receive emails. It’s run out of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and includes input from the provincial ministries of ag, but it’s been funded for the last 20 years by pretty much all the grower groups through checkoffs, and so thank you to them for funding this service to agriculture.

I’m working on wheat midge, and this is one of the “big bads” in wheat. It’s been kind of suppressed for the last little while, but if you get $130 million in yield losses like we did in the 1990s, that’s why you know it’s a “big bad.”

Ag Canada has thrown a lot of research at it. Back when the wheat midge first reared its ugly orange head, they had six or seven full-time research scientists working on this problem. At the same time, we had over 500,000 acres sprayed and we still got crop losses. Ian Wise and Marge Smith, two of the scientists who were working on this, called this “the most serious insect pest of spring wheat in Western Canada.”

Let’s define what is a parasitoid. This is a parasite that kills its host. A good parasite doesn’t kill its host, but a parasitoid does. Wheat midge has a parasitoid, Macroglenes penetrans. It is little, it

is black, and it goes after eggs and first-instar larvae of the wheat midge. This one stays inside the wheat midge larva and it doesn’t kill the wheat midge until the following year. Wheat midge overwinters as a third instar in a cocoon and when it is time to emerge in the late spring, instead of getting a wheat midge you’ll get one of these Macroglenes penetrans wasps coming out of the soil. They can reduce about 40 per cent of your overwintering population of wheat midge.

Macroglenes penetrans is why you don’t want to spray about a week after wheat midge has come out. If you’re a little bit late, go to your field, take a sweep net, and you can find these little black specks running around against the white background of the net– during the daytime you’ll see them searching on wheat heads as well. And remember that last year’s wheat field is probably this year’s canola field, so it’s another reason to stay out of flowering canola with your sprayer full of insecticide – because you might be wiping out Macroglenes as you’re spraying your canola. They will come out in last year’s wheat field, nectar in the canola, and then will move into wheat to go after wheat midge for you. Up in the Peace River Region, we started studying this, and we actually had fields with pretty much 100 per cent parasitism by this parasitoid on wheat midge.

I can never step away from talking about cereal aphids. Aphids are literally born pregnant, and they’re all female, so there’s no egg period. They just drop out and they tap into the phloem and they

start feeding, so your aphid populations can increase exponentially unless you’ve got a beneficial insect that acts on them. An aphid can produce two to seven live clones per day, and about 60 in her lifetime. And within about seven or eight days, those babies can start having their own babies.

We have three cereal aphids to worry about. The English grain aphid, the greenbug, and the bird cherry-oat aphid. They can cause honeydew issues. They basically poop sticky sugar, which can get mouldy and cause problems for the crop. They can also transmit viruses like barley yellow dwarf virus. And they of course they suck on the phloem and affect yield directly that way.

Our economic threshold for cereal aphids is 12 to 15 aphids per head, but that’s an average. If you have one head with 60 and you have 20 heads with zero, you are not at your threshold yet. You need to get out there and count 50 to 100 heads per field, and then take the average.

Originally, we used a conventional action threshold where if we get to that economic threshold of 12 to 15 per head you would spray. Now we are using a dynamic action threshold that takes the beneficial insects in the field into account. It uses an equation that predicts the number of aphids eaten by these beneficials. We have an app for that, the Cereal Aphid Manager app. This is free on the Apple and Android systems, and we released it in March 2018. This was a big project of mine.

I’ve been working on pea aphids lately. We have a good economic threshold for peas at nine to 12 per sweep at flowering. But lentils is a nominal threshold. “Nominal” means “anyone’s best guess” and is 30 to 40 per sweep. So we are working on a threshold for lentils. Until we started working on it, science had absolutely no idea what pea aphids were doing to fababean. No one had done any research on it before.

In conjunction with Sean Prager at the University of Saskatchewan and Ningxing Zhou, a master’s candidate, we are looking at improved management of pea aphids in Saskatchewan pulse crops.

In this research, we are actually counting individual lentil plants. My summer student Haroon Andkhoie doesn’t hate me yet, but I’ve been getting him to count aphids on individual plants. Another summer student figured out that one cup holds 38,000 pea aphids. There is an actual economic threshold down in the United States where they use quarter cups, half cups, and full cups of aphids, so I wanted to know how may aphids they actually had.

Our research on fababean is looking at a cumulative aphid density. That is the number of aphids on the plant and how long they’re on that plant for. At our first density fairly early on, we would reach that density and then spray. By our third, fourth, fifth density the aphids had overwhelmed the plants and we had huge yield losses. There were no pods on density 4. I think that the lack of pods in fababean was due to the aphids just stressing the plants out and they aborted their flowers.

Lentil research was basically the same as fababean. With insecticidal treatments at our first two densities, we get some yield, but no

yield at the three later densities. So what we need to do in the future is look more at thresholds in the early spray timing and completely forget about those really high aphid densities later on, because obviously lentils and fababean cannot handle really high populations –they have to be sprayed earlier. Crop staging is likely a major factor.

Aphids have parasitoids, too. The larva develop inside an aphid and create dead aphid mummies that are stuck to plants. These are great visual cues to say, “Hey, you’ve got parasitoids active in your field.” Aphidius spp. create brown mummies and Aphelinus spp. create flat black ones. After the parasitoid lays an egg in the aphid, about 10 days later you get these aphid mummies and then five days after that parasitoid wasps emerge. These wasps attack other cereal aphids and start the cycle over again.

For pea aphids, there is also a different genus of parasitoids, the Praon. Instead of staying inside the mummy, the larva crawls out underneath the aphid and it pupates underneath this now-empty aphid-mummy.

Not all wasps are “beneficial.” Pteromalus venustus is a little wasp that is not beneficial because it goes after alfalfa leafcutter bees. Another parasitoid, Dinocampus coccinellae attacks ladybeetles. This wasp lays an egg into the ladybeetle, and also leaves behind a virus that becomes active as soon as its offspring is ready to crawl out. It paralyzes the ladybeetle when the larva crawls out from underneath it’s wings, and then it pupates between the legs of the ladybeetle as the ladybeetle gently hug its parasitoid that has just crawled out of it.

Dinocampus coccinellae are all female. They can emerge from a ladybeetle and lay an egg right back into that ladybeetle. The ladybeetle is alive and still kicking, but still paralyzed.

There are other wasps that we don’t like and they are called a “hyper-parasitoid.” They will lay an egg into a parasitoid that’s inside the mummy. So we’ve got wasps that attack the wasp inside the aphid, and these guys are not our friends. Dendrocerus bicolor and Asaphes suspensus are two hyperparasitoids that are not beneficial.

Predators eat other insects. The hoverfly larva is “aphidophagous” and that means, “I eat aphids.” That’s basically all the hoverfly larva does. They’ll take out about 12 aphids a day.

Also associated with pea aphids is the soft-winged flower beetle (Collops). They look like a cereal leaf beetle, so you have to look at the different patternings and what they’re doing. When you see this beetle associated with pea aphids in a pea crop, it’s probably not a cereal leaf beetle because it’s in a pea crop. These soft-winged flower beetles can eat about 54 pea aphids a day.

We’re also finding soft-winged flower beetles associated with Peritrechus convivus. Back in 2017, we just called this “the Twitter mystery red bug.” We had it identified by experts in Ottawa and we identified it by genetic barcoding, and the name of the genus is “dirt-coloured seed bug.” The nymphs are red while the adults are actually coloured like dirt. This insect has been bringing up more questions than answers. We didn’t have any funding to look more into these questions, so I just went out, looked at a few fields, and brought some to the lab.

What I can tell you about these red bugs is the literature suggests they like to hang out in the edges of sloughs. During our drought years, we often plant into the sloughs. So there’s a good chance that we’ve planted crops right into those slough edges, and now we’re seeding in their territory.

This is one of those insects that we just don’t know when it’s going to become a pest and why it’s becoming a pest. I’ve seen

them go after flax, canola, and soybean – whatever is there. After it rained though, they stopped feeding on the plants, so it might just be a drought trigger, because there’s nothing else for them to get water from, and that’s why they are feeding on the plants.

Bertha armyworm goes in cycles. Prairie Pest Monitoring Network monitors them with a pheromone trap so that we can let growers and agrologists know if populations are building up. They get attacked by Banchus flavescens, this amazingly big and orange parasitoid. Bertha armyworm also gets attacked by flies that parasitize them.

Predatory ground beetles will also attack bertha armyworm. Bertha armyworms, if found on the ground, will get torn apart by ground beetles. Pterostichus melanarius is an introduced ground beetle from Europe, and it, other ground beetles and a few species of rove beetle might also attack bertha armyworm.

Calosoma species, another ground beetle, actually has the common name “caterpillar hunter,” and eats bertha armyworms. If it’s got big eyes that are forward-facing, you know it’s a predator. These guys are excellent predators, and most of our insecticidal sprays will leave the ground that they’re running across toxic to them for about a week afterwards. These ground beetles are kind of the unsung heroes in your field.

Diamondback moth is another pest that blows in, so we also use pheromone monitoring traps. If they come in early, we can have problems on the canola. They get attacked by a lot of different parasitoids though. Diadegma semiclausum is one that lays its eggs inside a diamondback moth larvae.

Ladybeetles also eat diamondback moth larvae. If you have ladybeetle larvae in your field, you want to scout for whatever they’re eating, because mama ladybeetle won’t lay eggs in a field unless there is something for her offspring to eat.

7-spotted ladybeetle larva.

In the dynamic action threshold for cereal aphids, adult ladybeetles are eating about 50 to 80 aphids per day, which is pretty good, and their larvae will eat about 70 per day.

Green lacewings are green and have wings that look like lace. Their larvae are commonly called aphid lions. If you’re sweeping and you find one of the adults in your sweep net, the first clue that you have a green lacewing will be the smell. They

release something that smells really bad, because it doesn’t want you to eat it. In the dynamic action threshold, their larvae will take out about 30 aphids per day, and they leave behind the dried husk of an aphid. Their big mandibles inject a digestive enzyme that liquefies the inside of the aphid, and then it sucks out the digested insides like an aphid milkshake. It takes about 15 minutes or so to eat an aphid. For a cabbage looper, the green lacewing larvae takes about one hour to suck out all the juices.

Another one that uses this piercing and injecting of digestive enzymes is the minute pirate bug. Around Saskatoon, we get Orius tristicolor and in Eastern Canada they have Orius insidiosus It’ll eat about 12 aphids a day, but it will also eat things like diamondback moth eggs.

Damsel bugs are like a little praying mantis, with raptorial front legs. They have a long beak, and they will also inject digestive enzymes.

Spiders are also predators, although they aren’t ‘insects’ because they have eight legs.

Some spiders build webs in your fields, and others run around on the ground eating insects. Their impact is kind of understudied in Canada right now. “Daddy longlegs” or “harvestmen” are not quite spiders but have these huge fangs that they use to capture their prey.

Wheat head armyworm has started to show up. You often don’t know that you have a problem in your field until you go to swath it, and you see a mess of them on your cutter bar.

This insect will attack barley and wheat. One can take out an entire wheat head in one day. It has two generations in one year. If parasitoids don’t take out the first generation, you can get a buildup into the second generation that continues the damage.

We don’t usually have too much in the way of issues, though, because it’s got a pretty good parasitoid, a Cotesia species. You may see the pupae of Cotesia in white clusters on the awns of the heads of cereal crops. The wasp lays an egg in the wheat head armyworm and the egg splits multiple times before each cloned egg hatches inside the armyworm. The genetically identical female Cotesia larva all emerge at the same time from the one egg that has split inside the caterpillar. As soon as they come out, they start making their cocoons and you get these Cotesia clusters in the field.

The two main flea beetles that are attacking canola are the crucifer and the striped that is moving down from the north. When you’re scouting, you want to look for 25 per cent damage – that is the action threshold. If it’s a hot day, by the afternoon that plant can be at 50 per cent damage, which is where we see yield losses in canola. We have two generations of flea beetles, so you’re going to see them coming back into the field in the fall for the “overwintering generation.” Conventional wisdom used to be to plant early to escape flea beetles because the crucifer didn’t peak until mid- to late-June. But the striped flea beetle peaks before the crucifer flea beetle. So now we have a longer period of flea beetle feeding from mid- to late-May through late June.

I’ve had the question of whether there were just more flea beetles in 2019. I compared the number of flea beetles collected on sticky cards in my plots at Saskatoon in 2018 to 2019. The answer was yes, there were a lot more in 2019. If we look back 10 years ago, they would have been mainly crucifer, but the striped has really been taking over recently. The second generation will come back in the fall, and they’ll feed on anything that’s green. If it’s nothing but pods, they will feed on pods, and they can cause debarking, and this can lead to pod shatter. But none of the research has indicated that this is economical damage at this point in time.

Microctonus vittatae parasitizes flea beetles, but unfortunately this parasitoid doesn’t do a really great job. It has only 2.5 to 5 per cent parasitism rate, which is not enough to control populations.

A well-fed crop is a strong crop.

Presented by Jeff Schoenau, College of Agriculture and Bioresources, University of Saskatchewan at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

We think a lot about yield, but another important part of crop production is the influence that plant nutrition has on crop quality and health. And that transcends to human health as well. Soil health affects plant health, and that ultimately affects human health.

A basic premise of plant health is that a well-nourished crop with the balance of essential macro and micro nutrients really provides the best yield, and also the best ability to fend off foes, whether it’s diseases or maybe even insects. We can probably sum it all up into a single short statement: “a well-fed crop is a strong crop.”

The first key principle of plant health from a nutritional standpoint is concentration of nutrients in plant material. Concentration may be linked to nutrient density. I like to think of nutrientdense foods defined as a food that is rich in minerals, vitamins, and other components that are desired for human health.

To increase the nutritional value of foods requires an understanding of those factors that affect the concentrations that are found in the plant. The most important is genetics. For example, canola has a high requirement for sulphur because of the sulphur containing compounds that are involved in the physiology of those Brassicae crops. So, genetics is important.

Anybody that does crop scouting and takes tissue samples is certainly aware of the importance of the effect of plant part and age on nutrient concentrations in a plant. For example, annual crops take up most of the nutrients they need early on in their life cycle, but as they grow and photosynthesize and fix carbon, that concentration decreases.

Environment is very important. For example, nutrient concentration might be higher if something shuts down plant growth, so that nutrient isn’t diluted by photosynthetic fixation of carbon and higher yield.

Another consideration is the availability of a nutrient in the soil. Nutrient concentration in plant tissue can be influenced through fertilization. That concentration typically follows an S-shape relationship in soils with very low levels of nutrients. For example, nitrogen concentration in plant tissue may actually decrease initially with fertilization in a very nitrogen-deficient soil. That is called growth dilution. A little bit of nutrient added under a condition of extreme deficiency results in an explosion of plant growth and a production of dry matter such that the concentration may actually decrease initially.

Beyond that, as we increase the nutrient availability, the concentration in plant tissue increases. Finally, depending on the nu-

trient, as we increase nutrient availability further, there may be no further increases in concentration as the plant reduces or ceases uptake. But for some nutrients – for example, nitrogen – as nutrient availability increases further in that soil, the plant continues to take it up beyond the point of maximum yield. There’s no further increase in yield, but the concentration increases, and this is referred to as “luxury uptake.”

In cereals there is a critical level where further increases in nitrogen fertility are not associated with any yield increase but instead the nitrogen is going towards increasing protein content. In spring wheat, that is around 13.5 or 14 per cent.

Typical grain and protein curve in wheat. Adapted from Engel et al.,1999.

A study by Amy Mangin and Don Flaten at the University of Manitoba showed that split applications of nitrogen – for example, 80 pounds (lbs.) of nitrogen per acre at planting, plus 30 to 60 lbs. at stem elongation to flag leaf – bumped protein content up by about half a protein unit. Late supply of nitrogen in a cereal crop will go more towards protein and less towards yield. High yielding spring wheat varieties need high rates of N to optimize both yield and protein.

Sulphur is another important nutrient, and is a building block of two amino acids, cysteine and methionine. Research by Rigas Karamanos showed that wheat grown on soil that is highly deficient in available sulphur may respond to sulphur fertilization and increase protein concentration.

There is also some research that shows that having adequate amounts of sulphur-containing amino acids can also contribute to increased protein quality and improved bread-making quality.

Forages benefit from fertilization. For example, a study conducted by one of my graduate students, Bayartulga Lkhagvasuren, looked at the response of brome grass to nitrogen fertilization. At one of our sites close to Colonsay, Sask., 50 to 60 lbs. of nitrogen per acre added as dribble banded urea ammonium nitrate solution

maximized yield and also produced significant increases in protein content of brome grass. Rates of nitrogen fertilizer added above that continued to increase protein, but there was no further increase in the brome grass yield.

In pulse crops, protein content is generally not highly responsive to nitrogen fertilization. One of my graduate students, Harshini Dona, conducted a field study in south-central Saskatchewan with soybean and lentil and different rates of starter fertilizer. A starter blend of urea and monoammonium phosphate – a 50-50 blend of 11-52-0 and 46-0-0 – was applied at increasing rates of zero, 10, 20 and 30 lbs. N per acre. There was not any increase in protein content with increasing N rates. The reason is that with a legume, the biological nitrogen fixation process will generally compensate for low nitrogen availability when conditions for fixation are good.

Some studies have reported that under phosphorus deficient conditions, starter phosphorus can give a protein boost to pulses, and this is related to the importance of phosphorus in the nitrogen fixation process.

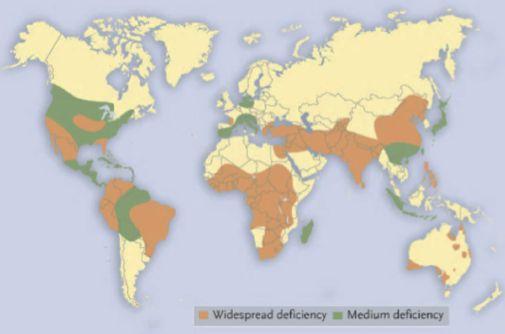

Micronutrients are also important for crop quality. The contents of bioavailable zinc and iron in grains are of special interest. For example, zinc deficiencies in humans are estimated to affect over 30 per cent of the world’s population. There are areas that have quite widespread crop zinc deficiency. One particular area is the Middle East, where human deficiencies of zinc are quite widespread in the population. A high content of bioavailable zinc is desirable in pulses that are exported to countries like Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.

On the Prairies, we’re quite fortunate because our soils, in general, are relatively high in available zinc. As a result, our pulse crops tend to be quite high in zinc content compared to some other parts of the world where the soils are low in available zinc. That gives our pulse crops a bit of an edge when it comes to marketing and selling.

There are several ways to help ensure high zinc content in pulse crops. Work at the Crop Development Centre by Dr. Vandenberg and Dr. Warkentin is looking at ways to increase the content of these important micro-elements in grain through plant breeding efforts.

Fertilization is another potential strategy for improving plant health. Sarah Anderson, as part of her MSc work at the University of Saskatchewan, looked at the effects of zinc fertilization on the phytate:zinc molar ratio and the estimated bioavailable zinc in lentil grain.

Phytate is a major storage form of phosphorus in seeds. It has plant and human health benefits but is also anti-nutritional be -

cause it inhibits absorption of zinc ions within the human intestine if it is too high in concentration. The phytate:zinc molar is the ratio of phytate to zinc. If the ratio is low, that indicates generally higher bioavailability of the zinc content in the grain.

In Sarah’s research, compared to the unfertilized control, fertilization with zinc decreased the phytate:zinc molar ratio, which is a good thing for human bioavailability. It appeared that the chelated form was slightly more effective than the sulphate form in enhancing bioavailability.

Zinc bioavailabitity in lentil fertilized with various forms of Zn

In terms of genetic effects, Sarah looked at three different classes of lentil – Maxim red lentil; Invincible, small green; and Impower, large green lentil at two field sites. At both of the field sites under the same zinc availability status, there was significantly higher concentrations and higher bioavailable zinc in the large green lentil compared to the small green or the red lentil.

Some other work conducted by Noabur Rahman, one of my PhD students, looked at zinc concentration in pea grown on a Brown Chernozem soil that had quite low concentration and supply rate of available zinc. Compared to the unfertilized control, zinc fertilization increased the concentration of zinc in pea seed. The chelated form also produced some of the highest zinc concentrations.

Another question that we addressed in some of our research is how does the addition of phosphorus influence the phytate and the zinc concentrations in grain? As part of the work that Steven Froese did in his thesis work, we looked at the effects of 20 kg of P2O5 per hectare added in different combinations of seed-placed monoammonium phosphate and a mid-season foliar monopotassium phosphate spray to field pea. The treatments include all the phosphorus applied at seeding, three-quarters at seeding and remaining at foliar, a 50:50 split between seeding and foliar, and the entire 20 kg at foliar timing. Each treatment had the same total rate of 20 kg/ha.

There was a trend towards lower phytate concentrations in the seed as the proportion of applied phosphorus at the foliar timing was increased. But as the proportions of foliar P were increased, yield was lower than with seed-placed P. Overall, there was no significant effect on total phytate content between the treatments.

Looking at zinc, there was occasionally slightly higher concentration of zinc in the grain when the phosphorus was applied in the foliar form. This suggests that foliar application may reduce that phytate:zinc molar ratio, but we really didn’t see any large effects, and no effects on the iron concentrations.

Nutrient management can affect the incidence of a plant disease. It can stimulate root and shoot growth, but very high rates of nitrogen can produce a heavy crop canopy with high humidity within that canopy that may favour the spread of certain pathogens. Work done by Randy Kutcher at Melfort showed that very high rates of nitrogen in canola, for example, were associated with increased incidences of blackleg and sclerotinia. With high fertilization rates, attention must be paid to address potential disease issues from a heavy canopy through fungicide application.

The second way that nutrient manipulation can influence plant disease is by changing the physical or biological micro-environment in the soil. A good example is how different fertilizers may affect the pH of the soil. For example, ammonium produces acidity when it’s oxidized to nitrate in the nitrification process, versus nitrate, which is not associated with acidity. Some work conducted on winter wheat in northwestern United States showed some interesting interactions of how ammonium versus nitrate influenced the population of pseudomonas bacteria in the rhizosphere, which is actually an antagonist to root rot disease that was affecting the winter wheat.

Another way that nutrient manipulation can impact plant health and disease is by increasing plant vigour and strength. Some recent research found that the optimum rate of phosphorus fertilizer for field pea is higher when the root system is compromised by Aphanomyces. The crop may be especially challenged in accessing an immobile nutrient, like phosphorus, in the soil under conditions of reduced vigor and root growth. However, it is desirable to try to get rid of the source of the problem rather than using a Band-Aid to try to address it.

The next year peas were grown on the wheat stubble, and were fertilized with zinc. There was a bit of response to zinc, but in many cases, it wasn’t statistically significant. But the interesting thing was that pea yield was significantly higher in the treatments where we had applied copper to the wheat the year before. It had us puzzled. We really couldn’t find evidence that it was a nutritional response, but pondered that perhaps it had something to do with the effect of the copper in reducing disease pressure in the pea. I think this is something that deserves some further attention down the road. Chloride fertilization can also play a role in plant health. Potash (KCl 0-0-60) is the most common source used to meet chloride recommendations on the Prairies. We’ve known for a long time – for example reported in literature in the 1990s south of the border in Montana – of the role that chloride fertilization can play on low-chloride soils in reducing the incidence of leaf diseases and root diseases in cereals. Brian Fowler at the University of Saskatchewan, in his program with winter wheat, also showed some responses of the winter cereals to chloride fertilization in the reduction of leaf spot in winter wheat.

Based on work by Ieuan Evans in Alberta in the 1990s, lower copper fertility was identified to aggravate ergot infections in wheat. A copper deficiency causes the self-pollinating florets to remain open longer, which increases the likelihood of the infection entering into that floret and the ergot body developing. On copper-deficient soil, copper fertilization may help to reduce the incidence of ergot in cereals, although this may not be a 100 per cent effective management strategy. And I think you’re only going to see this effect on soils that are truly copper-deficient.

Rotation can also impact micronutrient nutrition and response. My colleague, Dr. Ryan Hangs, looked at copper and zinc in a wheatpea rotation – copper added to wheat, followed by zinc added to pea. Soil was collected from 47 different locations across Western Canada. Some of these soils had available concentrations and supply rates of a micronutrient that indicated potential responses to fertilization. When copper was applied to wheat on 12 mineral soils that were suspected to be responsive to copper, there was a significant yield response. Foliar and banded application of copper sulfate significantly increased yield. However there was a lower yield from banded chelated copper compared to the control, which I think was because our rate was too high, and we saw some toxicity show up. We always need to be aware, with micronutrients in particular, there can be a fine line between sufficiency and toxicity.

I was involved in a study in the 1990s looking at the application of 40 lbs. of KCl at foot slope positions versus upper slope positions in the landscape in a farm field southeast of Saskatoon. We were interested in this topographic effect because the foot slope positions in this landscape had very low chloride levels in the top two feet. In the two years of the study, one year we had a significant wheat yield response to the application of potash in the foot slope regions, which we were able to attribute to the effect of the chloride. Was it a disease thing, or was it a nutritional factor? Unfortunately, we did not do any disease ratings. I think it had to do with a lot of snow the winter before that leached the chloride out of the upper profile in the depressions where the snowmelt water accumulated. The next year was drier and there wasn’t any response to the potash at either the upper or lower slopes.

There is less talk about chloride as a limitation in recent years, and I think one of the reasons is that there is more widespread use of potash in fertilizer blends, particularly for cereals. With chloride, the important thing to remember is that almost all of the chloride remains in the straw, which means that that all of it gets recycled back into the soil if the straw isn’t baled off the field.

A question was raised in the past about whether boron addition can reduce the incidence of clubroot in canola. Some early work indicated that boron addition reduced the infection of Brassicae by clubroot, but it was also associated with phytotoxicity. Followup work that was done in 2014 in a study conducted in Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec showed no reduction in clubrooted incidence with boron fertilization and no yield response except on one organic soil in Ontario.

Calcium is another nutrient that some researchers are looking at to help control clubroot. It seems that soil pH of 7.2 or 7.4 would be an optimum pH to help reduce the incidence of clubroot. We also need to be thinking about how fertilizers may be influencing soil pH and how that might perhaps have an indirect effect on the incidence of this disease.

Disease updates, reducing risk and practical management tips.

Presented by Dan Orchard, Canola Council of Canada & Curtis Henkelmann, central Alberta canola grower at the Top Crop Manager Plant Health Summit, Feb 25-26, 2020, Saskatoon.

My name is Dan Orchard and I’m an agronomist with the Canola Council of Canada at Wetaskiwin, Alta. I guess my claim to fame was the first discovery of clubroot in canola. A farmer called me because he had a problem in his canola and he didn’t know what it was. I helped identify it, so I guess my claim to fame is kind of the inventor of clubroot in Alberta.

Curtis: Well, that’s how I got to know Dan back in 2003. We farm just south of the Edmonton International Airport area. We’re spread out about 30 miles across and we crop about 4,000 acres. I figured out that we move 96 times down the road, in and out of about 128 parcels of land. In ’03 when we discovered this disease, it was quite devastating at the time. But, hey, we’re here today, and at the point now where we feel that we’re seeing a reduction in what we had initially.

Dan: I realized that the county south of where I discovered clubroot on Curtis’s farm was just as bad, but nobody knew how to look for it or what it was. So, I think one of the big take-home messages here is that you need to find clubroot early. You need to look for it.

Some other key points are to keep your spore loads low. The lower your spore load, the easier clubroot is to manage. We have incredible resistant varieties, but when they’re overused, they’re not going to last forever.

I think it’s also important for everyone to understand that as an agronomist or as a consultant or as a farmer, you need to always be thinking about a clubroot management plan because this is a

very controllable, manageable disease if it’s proactively managed. If we wait until we can see huge patches of clubroot, we’re behind the eight ball.

Plant cells are meant to be hollow to transport water and nutrients. Instead clubroot plugs the cells with microscopic clubroot spores, and that keeps the plant from up-taking water and nutrients. It’ll wilt and potentially die. You could fit 10 clubroot spores across the width of a human hair, and, in my opinion, this is why it’s so difficult to control and so prolific.

How is it spreading? Canola propagates clubroot but it doesn’t spread it. Moving soil spreads clubroot. Whether you’re growing barley or wheat or oats or just tilling your land, that’s what’s moving clubroot around.

When I first met Curtis, he was the first and only person to sanitize every piece of equipment.