TOP CROP MANAGER

Welcome to part two of Top Crop Manager Focus On: Herbicide Resistance. This final edition of our summer digital series summarizes more of the fantastic research presented at the 2018 Herbicide Resistance Summit, held Feb. 27 and 28 in Saskatoon.

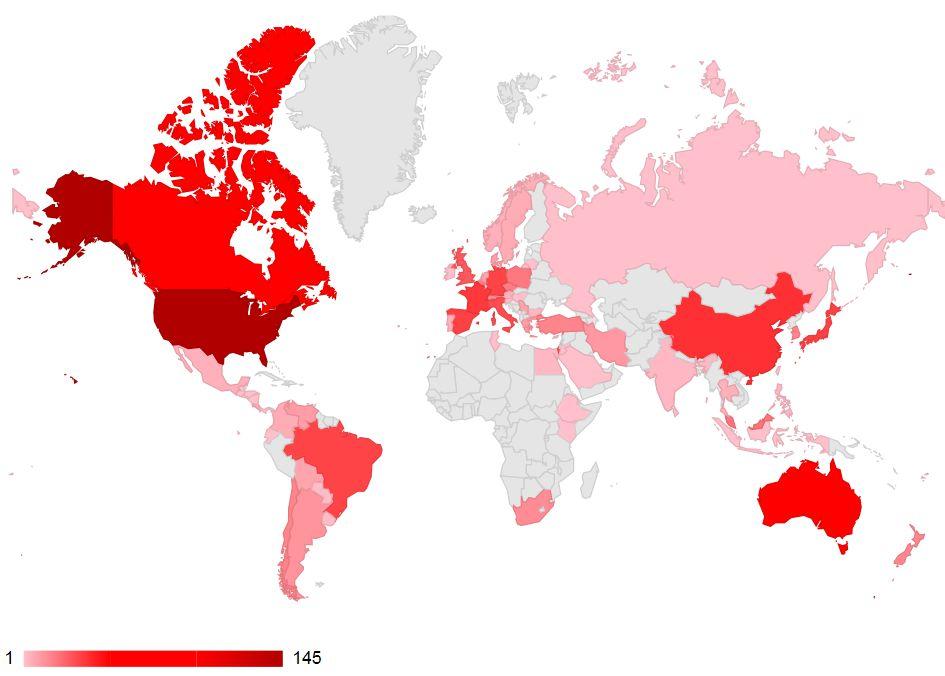

Now more than ever, herbicide resistance is a growing problem for field crop producers across Canada and around the world: in fact, between the beginning of June 2018 (when we released the first edition of Focus On: Herbicide Resistance) and the end of August 2018, nine cases of herbicide resistant weeds were entered into the International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds database at www. weedscience.org. According to the database, there are currently 495 unique cases of herbicide resistance globally. Based on that data, and the information our esteemed Summit presenters shared, this is not a problem that will easily disappear.

In this special edition, you’ll read perspectives and strategies from five herbicide-resistance experts from across North America. Though specifics vary, one message is clear: the management of herbicide resistance requires ongoing stewardship and attention.

PHOTO COURTESY OF PETER SIKKEMA.

your name and full postal address to Top Crop Manager , or subscribe at: www.topcropmanager.com. There is no charge for qualified readers. ON THE COVER Canada fleabane, shown here in corn, is one of Ontario’s most common glyphosateresistant weeds.

Editor: Stefanie Croley

Associate Editor: Stephanie Gordon

Western Field Editor: Bruce Barker

Associate Publisher: Michelle Allison

National Advertising Manager: Danielle Labrie

Group Publisher: Diane Kleer

Media Designer: Jaime Ratcliffe

As you prepare to wrap up another growing season, we hope you find answers to your resistance-related and other agronomic questions among our pages.

Presented by Mark Peterson, chair, Global Herbicide Resistance Action Committee, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Feb 27-28, 2018, Saskatoon.

Resistance is an evolutionary process by which weeds evolve to become resistant to whatever tools we are using to control them. It’s my contention that resistance cannot truly be eliminated. We can’t stop resistance but we can manage it. We can extend the life of these weed control tools as long as possible, and in some cases a very long time if we do the right things.

How does weed resistance develop? On a moderate to large field, there are millions and millions of weeds, and they’re not all exactly the same. There is a rare individual that happens to be resistant to the herbicide that you’re using. You spray and that rare individual survives and produces seed. Over time, as you use the same herbicide over and over again, that particular population grows and eventually what you end up with is a field that is dominated by this resistant population.

Resistance has been going on ever since herbicides were developed back in the late 1940s, early 1950s. A couple of examples of resistance to 2,4-D occurred in the 1950s but for a long time, about twenty-five years, there wasn’t very much resistance showing up. Not until around the early to mid-1970s were reports of resistance to triazines showing up, and after that point, the number of resistant cases kept increasing.

In Australia, resistant rye grass is a big problem; it’s resistant to almost every mode of action. In Western Australia, more than 90 per cent of the rye grass is resistant to one or more herbicide modes of action.

For a long time in Asia, resistance wasn’t a concern because a lot of hand weeding was used, but that’s rapidly changing as labour

shortages are developing because people are moving to the city. In China and India, herbicides are being used more and more, and as a result there is more herbicide resistance - in particular some of the grasses that you find in rice and wheat. About 15 to 25 per cent of the rice area in China has ALS resistance in grasses. About four million hectares of wheat in India is infested with resistant wild canary grass.

In Europe, resistance is a concern in grass species. Black grass in the northern part of Europe, and rye grass across Europe are areas of concern. Those grasses, like the rye grass in Australia, tend to be multiple resistant. In some areas of the U.K. they’re pretty much out of herbicide options to control black grass.

In the Americas, the concern is glyphosate resistance because of the widespread adoption of glyphosate tolerant crops. In South America, Conyza, a relative of Canada fleabane, is found on approximately 10 million hectares in Argentina; a lot of it is resistant to glyphosate and increasingly ALS herbicides. Glyphosate-resistant amaranthus species have become a problem. In Argentina some of it came from the U.S. on machinery and possibly with seed. In the U.S., resistance is about the pigweeds, mare’s tail, and kochia. Wild oat has been a problem in Canada for a long time.

Glyphosate resistance is the big headliner in the news over the last few years. Over the last six or seven years there has been a big increase in glyphosate-resistant weeds – now up to 40-plus per cent of the crop acres in the U.S. are infested with glyphosateresistant weeds. Again, dominated primarily by pigweed species, and mare’s tail.

ABOVE: A global perspective of herbicide-resistant weeds.

Target-site resistance is one of the key ways weeds become resistant. The weed has an “altered target site” so it’s not susceptible to the herbicide. Herbicides depend on target sites where they act and then interrupt some process in the plant that ultimately kills the weed. For a long time it was thought that target-site resistance was the main resistance mechanism, and a lot of the early weed resistance was target site.

However, non-target site resistance is a mechanism that is more concerning. In this mechanism, the target site does not change. The weed often has an enzyme that attacks the herbicide once it gets into the plant and breaks it down, and therefore makes it unable for the herbicide to do its job on the target site. This is also called metabolic resistance.

One of the most concerning things about metabolic resistance is that other herbicide modes of action that may not have been used in that field may not be effective because an enzyme in the weed can break apart several different modes of action. This potentially may even affect new modes of action that come along.

Some weeds and some herbicides tend to have more resistance. Weeds like kochia, wild oats, pigweed species, and ryegrass are genetically diverse. This results in a greater chance of a resistance mechanism showing up in any individual plant.

Some herbicides are relatively quick to develop resistance because the enzymes they work on are pretty diverse. The Group 2 ALS herbicides develop resistance pretty quickly. Group 9 glyphosate is thought

to have a pretty robust resistance mechanism. The enzyme in the weed that glyphosate works on doesn’t have a lot of variability, so it is a numbers game. Because glyphosate became so popular after glyphosate-tolerant crops, and glyphosate was sprayed so many times, that heavy selection pressure resulted in resistance.

For a lot of years, new herbicides and new technologies kept ahead of resistance. ALS chemistry fixed triazine resistance, and glyphosate fixed ALS resistance, and so on. The fact of the matter is there hasn’t been a real new mode of action for thirty years since the HPPDs came out.

Companies are continuing to innovate but it’s not easy. A lot of the low hanging fruit has been picked. They are looking for increasingly rare compounds that have to provide good performance and are broad-spectrum. There are a few ‘thought-to-be new’ modes of action but they are quite a few years away. Some of these molecules are quite expensive so it’s not going to be cheap. Some get thrown out because of toxicology or environmental characteristics, which leads to problems with regulatory approval. These are big hurdles that companies have to get over if they’re going to come up with something new.

Are herbicide-tolerant crops a solution? After glyphosate-tolerant crops there is the next generation of herbicide-tolerant crops. Monsanto Extend technology and others like Dow Enlist can help.

These new traits add some new tools to the toolbox for a given crop. For glyphosate-resistant waterhemp, the Enlist trait uses 2,4-D in the tank-mix to turn back the clock and get clean fields

again. But you cannot turn back the clock entirely. You cannot go back to the same practice of just spraying that same herbicide postemergent over and over again. The new traits have to be used as part of a program or you will end up right back in the same spot again.

Gene editing is a new technology that is different from GMOs. It is a way that the genetic material of a crop can be edited without interjecting anything new into it. Basically rearranging genetic material like plant breeders have done for many thousands of years. It has been demonstrated for ALS tolerance in canola, dry beans and rice, and glyphosate tolerance in flax. Currently, in a lot of jurisdictions these are not considered to be GM crops. But again environmental groups are looking at ways that they can generate a lot of fear around these, too. But for now, these tend to have an easier path to approval, so we’ll see what comes of it in the future.

RNA interference is another potential technology for the future. DNA is the blueprint in the weed for plant development, and proteins are the bricks and mortar that make up the plant. RNA is the means by which that blueprint gets translated into the actual bricks and mortar. What’s been discovered is that the RNA process can be interfered with by developing similar RNA types that break up that process. Potentially, this could provide unlimited modes of action. It can also thwart the weed’s processes for the development of resistance.

Finally, diversification of weed control practices is critical. Use multiple modes of action. Those modes of action should be overlapping. Use different cropping systems and different cultural practices such as injecting some tillage or maybe some delayed seeding. In Australia, they’ve had some success with harvest weed seed control.

Cover crops provide benefits in reducing weed populations as well as nutrient management. In some areas they aren’t practical because of the short growing season, but they can help with resistance management.

We know what we need to do but what’s preventing us from doing it? We have to be practical. We have to understand what farmers are up against. Macro-economic factors are something that everybody has to recognize as barriers. Some of these resistance management practices require increased investment of time and dollars. It’s important to acknowledge this and figure out how to deal with them as we try to implement best management practices.

Companies have stewardship programs because it costs hundreds of millions of dollars to develop new technologies and they can’t afford to loose those products within a few years. They spend

RNAi is an exciting technology but you’re not going to see it right away. There are a lot of hurdles. First, the development of field stable formulations will be necessary. These are fragile molecules, that don’t hold up very well in the environment. They are slow acting so if you’re trying to thwart resistance you probably have to spray RNAi products first and then spray an herbicide. RNAi products are very highly specific so a product has to be developed for each weed and each herbicide combination. The regulatory path is also uncertain; we really don’t know how regulatory agencies are going to look at these. And resistance will develop to RNAi technology as well - this has already been have determined on the insect side.

Investigate weed biology and educate growers

Develop new tools and cooperate to steward herbicide resources

Robotic weeding may be a possibility that is starting to come of age. John Deere recently acquired a company called Blue River Technology that’s focussed on this area. A website at www.seeandspray.com has a video that shows some of the potential for this technology. We have to keep an open mind in terms of new things to come. We’re going to have to find new, non-chemical means in order to keep our herbicides supported.

Think longer term and implement sustainable systems

ABOVE: Successful weed management

money on research, education, farmer advisor resources, and farmer incentives. More and more I’m seeing public/private education partnerships. One that I often point to is the Take Action program that’s supported by the United Soybean Board. I would encourage you to work with your commodity groups to develop practices that fit your area and with your crops. Weed resistance is a communal issue. Everybody has to play if we’re going to solve it.

How do we do the things that are going to maintain longevity of the tools we have in our toolbox right now? A lot has been published on best management practices, but I think it boils down to three main areas. One is to manage the seed bank. The best thing to do is keep the weed population low. You have to scout and control escapes. For example, if you have a wet spot in the field and you drive around it all season, don’t let the weeds go to seed. Some of weeds produce several hundred thousand seeds per plant so there can be millions of seeds coming out of that patch. Control weed seed production throughout the entire year using different methods.

Second, make sure to use herbicides appropriately. Spray weeds when they’re small. If you’re spraying big weeds, you’re putting more selection pressure on that herbicide. It is really critical to use the right rate at the right time.

The Global Herbicide Resistance Action Committee is part of Crop Life International. It consists of a host of associated organizations, industry organizations around the world. As an industry, we work together across companies to try to develop research programs, support symposiums for researchers, and share information on resistance to make sure there is a robust network of people working on resistance.

But at the end of the day, I think successful weed management really requires everybody to work together. Public researchers investigate weed biology and to help educate growers. Industry works on new technologies for the market place, and try to steward those that we introduce. And I think farmers are helping to solve this problem by thinking longer term to implement sustainable systems on their operations.

Presented by Peter Sikkema, professor, University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Feb. 27-28, 2018, Saskatoon.

There are now 41 glyphosate-resistant weeds in the world. Seventeen of those occur in the United States. There are six species in Canada, and four of those occur in Ontario. In Ontario, glyphosate-resistant giant ragweed was confirmed in 2008, Canada fleabane in 2010, common ragweed in 2011 and waterhemp in 2014.

The glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane problem started in 2010. I remember the day quite well. I received an email from an ag retailer in southwestern Ontario. They had applied glyphosate at twice the label rate as a burndown in a soybean field, and had excellent burndown, but there were individual plants that were not controlled. The weed escapes didn’t look like a typical fleabane plant. Typically, fleabane has one stem per plant, and in this biotype the growing point was burnt out with glyphosate but the plant regrew with multiple stems.

Joe Vink, a masters’ student at the University of Guelph, started research on glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane in 2010. The susceptible biotype was controlled with Roundup Weathermax at 0.33 and 0.67 litres per acre. In contrast, the resistant biotype was not controlled and there was no symptomology at all. The plants were highly resistant to glyphosate.

In 2010 there were eight fields in Essex County with glyphosateresistant Canada fleabane. Five of those fields were near Leamington, Ont., and three of those fields were adjacent to the Michigan border near Amherstburg, Ont.

The following year, glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane was found in five additional counties in Ontario. In 2012, it was found in eight counties. In 2013 it was found on the east side of Toronto. In 2014 it was in 28 counties in Ontario. And in 2015 glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane was in 30 counties in Ontario. The weed moved more than 800 kilometres over a five-year period, and now it’s found right from the southwestern part of the province to the county adjacent to the Quebec border. It’s occurring at densities that are causing significant yield losses in corn, soybean, and wheat. Ontario farmers consider glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane to be the number-one weed management issue in the province.

However, the problem has become even more challenging for Ontario farmers. There now is multiple resistant Canada fleabane. On a farm at Mull, Ont., we found Canada fleabane resistant to glyphosate and Broadstrike RC (Group 2). So we screened all of the weed samples in our seed storage at Ridgetown Campus, and 23 of the 30 counties with have glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane also have Group 2-resistant Canada fleabane. This makes the problem much more challenging for Ontario farmers.

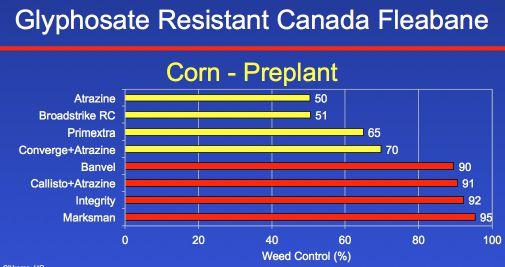

The first experiment that we looked at in corn is what farmers can add to pre-plant burndown to control glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane. Glyphosate was tank mixed with atrazine, Broadstrike, Primextra, or Converge, and you can see all of those provided less than 70 per cent control. However, Banvel, Callisto plus atrazine, Integrity or Marksman, all provided greater than 90 per cent control. The best treatment was Marksman, which is a combination of dicamba and atrazine.

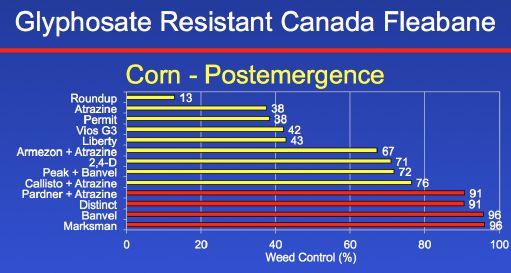

We did a parallel study to find out what a farmer can spray post-emergence in corn. Roundup, atrazine, Permit, Vios, Liberty, Armezon plus atrazine, 2,4-D, Peak plus Banvel, and Callisto plus

atrazine all provided less than 90 per cent control. But once again, we do have some good options in terms of managing this weed postemergence in corn. The dicamba-based products – Distinct, Banvel, and Marksman – all provided greater than 90 per cent control. And really interesting to me, a very old herbicide called Pardner (bromoxynil) plus atrazine also provided greater than 90 per cent control. The most efficacious treatments were the dicamba-based herbicides, either Banvel or Marksman. So in terms of managing Canada fleabane in corn, we have some really good options.

GR Canada fleabane control in soybean

The real challenge in terms of managing glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane in Ontario is in soybean. It is much harder to remove a dicot weed from a dicot crop than it is to remove a dicot weed from a monocot crop.

We ran three parallel studies; in the first study we looked at what an Ontario farmer can add to glyphosate in his preplant burndown to control glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane. We tank mixed Roundup with 2,4-D, Aim, Liberty, Gramoxone, Eragon, Integrity, FirstRate, Classic, Valtera, and Guardian Plus. None of those tank mixes provided 90 per cent control.

The second study looked at soil-applied residual herbicides that provide both burndown and full season residual activity. We tank mixed Roundup with Classic, FirstRate, Lorox, Sencor, Broadstrike, Pursuit, Command, Fierce, Guardian Plus, and Conquest. None of those provided 90 per cent control.

The third experiment looked at what herbicide could be added to glyphosate post-emergence to control glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane in soybean. We tank mixed Roundup with Blazer, Reflex, Basagran, Pinnacle, Classic, FirstRate, Pursuit, Cleansweep, as well as Flexstar. None of those provided 90 per cent control. Our best treatment post-emergence tank-mix with glyphosate was FirstRate, and it provided 51 per cent control of glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane, so that was very disappointing. These studies were done between 2011 and 2015 with every single broadleaf herbicide registered for weed control in soybean in Ontario, and not one of them provided 90 per cent control.

Just so you can appreciate why I say 90 per cent control is important: in the fields with the heaviest weed pressure on commercial farms in Ontario, the highest density that we counted was 8,000 per square metre. So 90 per cent control of 8,000 still means you have 800 left per square metre and that is not nearly good enough. You are still going to have dramatic decreases in soybean yield.

Dr. Mark Loux from Ohio State University says, “The bottom line in Canada fleabane management is that we are trying to avoid having to control it with post-emergence herbicides since they largely do not work.”

In our research, we’ve concluded that Roundup plus Eragon (Heat in Western Canada) applied preplant is the foundation for glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane control. But, there’s a big “but” here – and that is the consistency of control.

We did 84 studies with Roundup plus Eragon plus Merge as one of the treatments in those studies. In 54 per cent of those studies, Roundup plus Eragon plus Merge provided greater than 90-per-cent control. However, 46 per cent of the time it didn’t provide acceptable control.

So we’ve concluded that Roundup plus Eragon, even though it’s our best treatment, does not provide consistent control.

We concluded that a three-way tank mix is required for the control of glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane in soybean. Roundup plus Eragon, in one study, provided 84 per cent control. We tank mixed Roundup plus Eragon with either 2,4-D or Sencor. The three-way mix of with 2,4-D provided 92 per cent control and the three-way tank mix with Sencor provided 97 per cent control. If you’re not growing Xtend soybeans in 2018 and you have glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane on your farm in Ontario, I’m recommending the Roundup plus Eragaon plus Sencor tank-mix on soybean this spring,

However, there’s a new player on the market. Roundup Ready Xtend Soybean was introduced in 2017. I used to think that dicamba was almost bulletproof in terms of the control of glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane, but I was wrong. I looked at all of the studies that we’ve done over the years and found there was a rate response with dicamba for the control of glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane. When dicamba was applied at 300 grams per hectare (330 millilitres of Xtendimax per acre), 450 grams and 600, there was a rate response moving from 80 to 88 to 94 per cent control. You need to use the higher rate of dicamba to get greater than 90 per cent control.

However, in 2017 there was one field in Ontario with four different experiments sprayed on four different days with glyphosate plus dicamba. In all four experiments there were fleabane plants where the growing point was killed but the plant grew back with multiple stems that arose from axillary buds at the base of the plant. It wasn’t an environmental effect. I had never seen that in the first six years that I studied the control of fleabane with dicamba. So even dicamba is not perfect for the control of glyphosateresistant Canada fleabane.

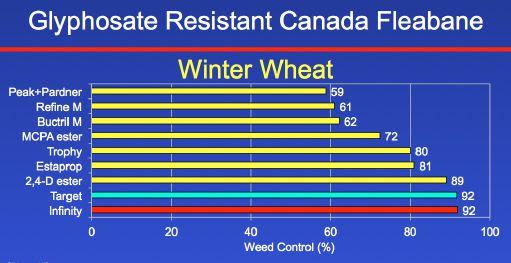

We studied the commonly used broadleaf herbicides in winter wheat in Ontario. Peak, Refine, Buctril, MCPA, Trophy, Estaprop, and 2,4-D ester provided less than 90 per cent control. Target provided 92 per cent control. However, I will never recommend Target for weed control in winter wheat because dicamba in Target is just simply too hard on the crop. We have had up to 25 bushel per acre yield losses where we include dicamba in our broadleaf herbicide in winter wheat. I think we’re down to essentially one herbicide to manage glyphosateresistant Canada fleabane in winter wheat. Infinity (pyrasulfotole and bromoxynil) provided 92 per cent control.

Two or three years ago I would have never reached this conclusion, but our research and farmer practices indicate that glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane is a manageable problem. But I would also say that Ontario farmers will lose a tremendous amount of money due to yield loss due to glyphosate-resistant weed interference, as well as increased herbicide cost. If farmers are going to use my favourite tank mix,

Roundup plus Eragon plus Sencor plus Merge, their burndown treatment goes from $5 an acre to $30 an acre. Their first two bushels of soybean that they produce is just to control this one weed on their farm. If you think that the first 40 bushels of soybean just go to cover your variable cost, and you have an average yield of 50, you’ve reduced your profitability by 20 per cent just because you have this weed on the farm.

Can Ontario farmers eliminate this problem through good weed management? I would suggest that they can’t. Glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane grows in non-crop areas. It has windblown seed. There’s an indefinite source of Canada fleabane seed. Ontario farmers will have to continue to manage this weed indefinitely into the future.

Mike Owen from Iowa State University says, “The evolution of glyphosate-resistant weeds is not a problem with the herbicide glyphosate or the Roundup Ready technology. Glyphosate-resistant weeds develop because of the way we used glyphosate and the Roundup Ready technology.”

North American corn and soybean farmers have indicated by their purchasing patterns that they value Roundup Ready crops and the use of glyphosate for weed control. In Ontario in 2017, 78 per cent of soybeans were seeded to Roundup Ready cultivars and 97 per cent of corn was seeded to our Roundup Ready hybrids. But I think that for farmers to continue to get benefit from this technology in the future it must be used less frequently or it must be used differently than it was in the past. If we continue to rely on glyphosate to the exclusion of other weed management practices, we will continue to select for glyphosate-resistant weeds in Ontario.

In order to preserve the use of glyphosate for weed management I’m going to ask seven questions. Would you consider adding a non-Roundup Ready crop to your rotation or adding an additional non-Roundup Ready crop to your diversified crop rotation? In Ontario, there are lots of possibilities for adding diversity to your crop rotation including conventional corn, identity-preserved soybean, Xtend soybean not sprayed with glyphosate, cereals, dry beans or forages. There are lots of other cash generating crops that Ontario farmers could include in their rotation.

The second question is would you consider applying multiple herbicide modes of action on every acre every year by using a twopass program? We have lots of options of introducing diversity into our weed management programs. In corn we have excellent pre-emergence herbicides, such as Acuron, Converge, Engarde, Integrity, Lumax or Primextra. And in soybean you could use products like Boundary, Canopy, Conquest, Fierce, Freestyle, Integrity, Optill, Pursuit or TriActor.

The third question is would you consider applying multiple

herbicide modes of action on every acre, every year by adding a tank mix partner to Roundup applied post emergence? Once again we have lots of options. In corn you could use Banvel, Halex, Marksman, Vios, and in soybean it could be Classic, FirstRate, Flexstar or Pursuit.

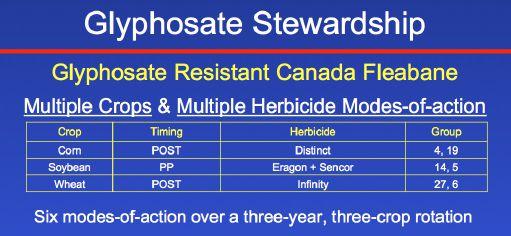

If you implemented those three strategies in a diversified crop rotation of corn, soybean and wheat, you would be using six different modes of action over your three-year, three-crop rotation. I can assure you, with that kind of diversity in your weed management program, you would reduce the selection intensity for glyphosateresistant weeds.

The fourth question is would you consider strategically incorporating some of the alternate or new technologies when they become available rather than relying on Roundup Ready exclusively? In corn, Liberty Link corn and Enlist corn are available. In soybean, Liberty Link or Roundup Ready Xtend soybean are registered. And it’s expected that Enlist and Balance soybean will be available in the near future.

Fifth question is would you consider incorporating tillage at strategic points in your diversified crop rotation? I’m not a big tillage guy, I think we have to do everything we can to conserve that topsoil resource for future generations. However, tillage may be one component of a long-term, diversified weed management program.

Number six is would you consider seeding a cover crop after winter wheat harvest to reduce Canada fleabane emergence? My brother grows winter wheat. The day that he takes his wheat off, he seeds a cover crop. Fleabane doesn’t establish very well if you have a really dense cover crop. You can approach 100-per-cent control of fleabane in the subsequent corn crop the following summer by planting a dense cover crop after combining winter wheat.

And the last question is would you consider making near-perfect weed control your objective in your corn, soybean, and wheat rotation? We simply have to reduce weed seed return to the soil or we’re just going to perpetuate this problem in the future. I think with the tools we have in 2018 we can do that.

My hope is that Ontario farmers will implement weed management practices that limit the selection of additional glyphosateresistant weeds. This will ensure the usefulness of glyphosate and Roundup Ready crops for many years in the future. I think glyphosate’s a fantastic herbicide, and I think it’s incumbent on all of us, whether we’re in research, if we’re making recommendations to farmers, or farmers to ensure that we use this technology properly so that future farmers will get the same benefit as what farmers did in the past 20 years. If you do not have glyphosate resistance on your farm yet, adopt integrated weed management now and use glyphosate judiciously at strategic points in your long-term crop rotation.

Presented by Steve Shirtliffe, University of Saskatchewan department of plant sciences, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Feb. 27-28, 2018, Saskatoon.

Integrated weed management requires as many weed control methods as possible. You try to prevent weeds from becoming established. Weeds can be controlled with tillage. Cultural weed control can be used by making your crop as competitive as possible. Biological weed control utilizes organisms that may be pathogens that kill the weeds. Rodents and insects eat weed seeds in your crop and can have a huge effect. Integrated weed management includes herbicides as well.

I know that the idea of integrated weed management has overwhelmed producers with complexities and checklists of all the possible control measures. Farmers want to know what works and what doesn’t.

The first practice is harvest seed management. I did my PhD work in Manitoba 23 years ago and looked at chaff collection. We were looking at it as a way of weed control for Group 1 herbicide-resistant weeds. The first thing we noticed with wild oats – and others have found this, too – is that as the harvest timing goes later, most of the seeds fall off. But in my work in Manitoba with wheat, when you swath the crop about 50 per cent of the wild oat seeds would still be in the swath. If you straight cut, most of them would’ve fallen off.

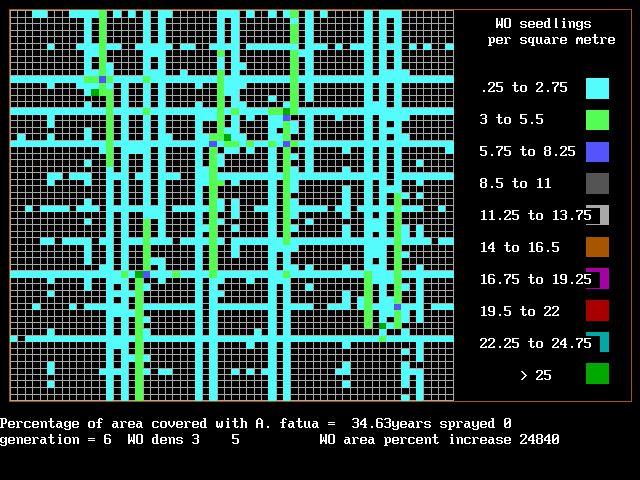

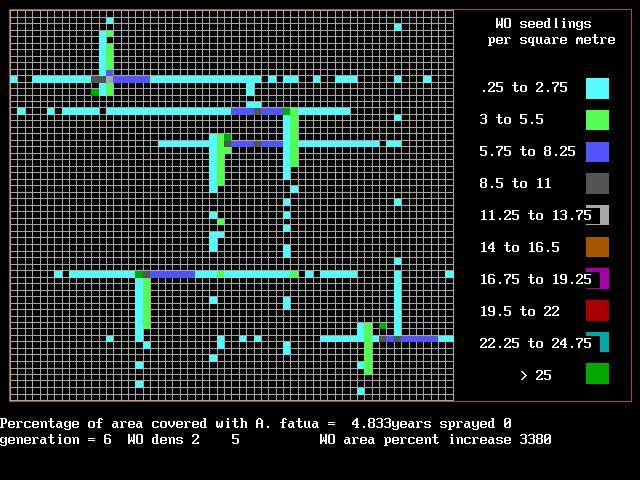

This characteristic of seed drop prior to harvest should write off the idea of harvest weed seed management, but I think a key idea here is wild oats have very little seed dispersal. They don’t have a seed dispersal mechanism other than something mechanical like a combine spreading the chaff and seeds. So, if the wild oat seeds fall down in the exact same spot every year during straight combining that may not be a big problem. My approach is that we have to start looking at herbicide resistance as a proportional argument and not as a yes/no argument – “does this field have it or not?” We have to start looking at it as a spatial argument – i.e. if you have one small patch of wild oat resistance in your field, that’s not a big problem. If we can isolate it and keep it there, that’s a good thing. So, I think having weed seeds that fall off early is a good thing.

One thing that we did realize was how harvest weed seed management – in the case, we were using chaff collection – influences the dispersal in the field. What we found was that chaff collection reduced the spread of wild oats by about a factor of ten. Without chaff collection, the wild oat seeds are moved down the field with the combine, which results in the wild oat patch growing in size.

As part of my PhD thesis I went to Montana in the late 1990s and

learned computer modelling from Bruce Maxwell. I wanted to model the dispersal of wild oats in the field, and to test harvest weed seed management and timing of harvest. My idea was that maybe you’re better off letting the weed seeds fall off rather than going through the combine and being spread around the field.

We simulated wild oat combine dispersal with and without chaff collection and compared swathing (early harvest) and straight cut (late harvest). We started off with five little patches of wild oats that were two metres by two metres (six feet by six feet).

After five years of the model running, the patches with chaff collection had spread out somewhat. With a late harvest and chaff collection the patches hardly got bigger at all. When we harvested without chaff collection, the wild oat dispersal when swathing was much worse. With a late harvest, most seeds fell off and there was much less dispersal.

I think with straight cutting in Western Canada, most of our wild oat seeds are falling off and the patches aren’t spreading that much. I would present this as a hypothesis: that Group 1 resistant wild oats has gotten worse, but it hasn’t affected how we manage weeds that much; that in many cases, it’s still isolated patches that haven’t been spread around. I can’t prove this, but I would say that, definitely, allowing

those seeds to fall off onto the ground –because there’s probably a big seed bank there already – it’s probably a good strategy, but that should be tested by somebody.

In lentils, Pursuit (imazethapyr) herbicide was used off-label for many years to control wild mustard. When the imi-tolerant lentils were released, Odyssey, (imazamox + imazethapyr) was relied on heavily without any tank mixes. Not surprising within a few years Group 2 resistant weeds were selected. I would look at fields in lentil-growing areas and think, “That’s terrible. I can grow organic lentils that are less weedy than that.”

First thing to look at is seeding rate. If you seed your lentils at what would be considered a normal rate, you get half lentils and half weed biomass. If you increase the seeding rate, you decrease the weed biomass. You’re putting more plants in there to take up more space, essentially increasing the competition. Increased seeding rate increases the yield, as well.

We’ve looked at this in the context of an integrated weed management system, where colleagues Chris Willenborg and Eric Johnson at the University of Saskatchewan looked at using fluthiacet-methyl – which is Cadet in the U.S. – as a possible herbicide on lentils. The lentil-breeding program is still looking at this, trying to find some varieties that are more tolerant to it. But tolerance is a big issue in this crop. As the rates get higher, you get a lot of leaf bleaching.

We used the concept of a dose response curve. As we increased the dose of the herbicide on a log scale, it decreases mustard biomass. But what we also found, as we increased the seeding rate from low to regular to double the recommended rate, we were able to shift the dose response curve down. This means the herbicide could work a lot better with a higher seeding rate than a lower seeding rate. Colleen Redlick, who did this work, likes to refer to this as a tank mix, but instead of adding another herbicide to your spray tank, you’re adding more seed to your air seeder tank.

This came through in the lentil seed yield as well. If we had too low of a dose of the fluthiacet-methyl, the yield was lower. However, when we doubled our seeding rate, we had this nice, flat response. We weren’t relying on the herbicide as much and could have a less toxic dose. So, increasing the lentil seed rate increased our herbicide efficacy.

Essentially, we’re not relying on the herbicide as much. About 260 seeds per metre squared was where it resulted in greater efficacy.

We have used mechanical weed control in field pea using a small flex-tine weed harrow at the third node stage. There’s a sweet spot in the amount of crop burial at around 75 per cent. The one key problem is that most of the research is on fields with almost has no residue. Working on a no-till field with narrow spacings will just plug up the harrow.

Eric Johnson started working with a mintill rotary hoe about 10 years ago. The great thing about a rotary hoe is that it can work in fields with a lot of residue. Eric found a lentil crop to be quite tolerant to the rotary hoe. They’re available in wide widths, and are starting to be used in some areas.

Research is also looking at inter-row cultivation. Some producers are using inter-row tillage on row widths as narrow as seven or eight inches. The tillage units have camera-guided systems which steer the cultivator between the rows. It can work really nicely, but of course you can’t get the weeds in the row.

Katherine Stanley did some work on the tolerance of field pea to inter-row cultivation. We found that within the critical period of weed control in peas, between five and 10-node stage, you weren’t damaging the crop at all. Going later, started to damage the potential yield. We were encouraged with the results.

The question I always get is, “What machine should I buy? What works? What doesn’t work?” Some of the decisions are going to come down to timing. The rotary hoe only works when the weeds are just emerging, but it has good tolerance on the crops. The harrow will work with bigger weeds, but it’s hard on the crops, so you tend to use it later. Inter-row tillage doesn’t control the weeds in the crop row, and you actually need the crop to be up so the machine can steer between the rows.

Research was conducted in lentil and field pea looking at all three tillage options and in combination with each other. What we started to see before we analyzed the data was that the rotary hoe was working well. We were getting very nice visual weed control. The rotary hoe followed by inter-row tillage was also giving nice visual weed control. One of our best treatments was often our rotary hoe followed by inter-row tillage. We were getting about 76 per cent reduction in

weed biomass without an herbicide. This was under organic conditions with severe weed competition. But when we combined all three machines, we started to get into issues of crop tolerance – we were beating up the lentils a bit too much from all the mechanical control passes.

We had a seeding rate effect as well –increasing our seeding rate, reduced our weed biomass by 16 per cent. In terms of yield response, increasing our seeding rate gave us a 30 per cent yield boost. Our best weed control, rotary hoe followed by inter-row tillage, gave us about a 55 per cent increase in seed yield, which was getting close to that of the hand weed-control. Overall, the best combinations of increased seeding rate and tillage increased seed yield by about 70 per cent and reduced weed biomass by about 80 per cent.

These tillage treatments are effective on annual weeds. Of course, they’re ineffective on most perennial weeds. The question is whether they have a fit on conventional farms. I don’t know. I’m not a conventional farmer. I’m just throwing it out there. “Are we desperate enough yet” is basically what it comes down to, right?”

As an extension of harvest weed seed management, there are other ways to reduce weed seeds returning to the field. One way is to target weeds that mature before the crop with weed wiping and weed clipping. There are many weeds that grow through shorter crops like lentils or flax. Most of their flowering bodies and seed production will take place above the crop canopy. Good candidates are wild oat, wild mustard and Canada thistle. Lower growing weeds like wild buckwheat and cleavers would not be good candidates for weed wiping or weed clipping. Crop yield is still going to take a hit, but the idea is to prevent the weed seeds from entering the seed bank and to reduce the problems the following year.

This has been done for years. Farmers have jury-rigged equipment to clip weeds above the canopy. One example is a farmer who modified a swather by taking off the canvas and putting metal over the support frame to allow the swather to clip weeds and let them fall to the ground.

Eric Johnson looked at hand weedclipping above the crop canopy for wild oat control. He found that either late clipping or clipping three times was as good as the

herbicidal weed control in how many wild oats came up the following year.

Some commercial machines have been developed. Out of England, there’s a CTM weed surfer that has rotors that cut off weeds above the crop. There’s also the CombCut machine, which has knife blades and a reel that spins quickly. It allows grasses to go through, or in broadleaf crops, you can clip the weeds above the canopy. Right here in Saskatchewan, Borgault has started building a weed clipper. So, clearly, the industry perceives that there is a need for this technology out there.

We’ve looked at clipping in lentil with the CombCut in an experiment we’re doing with Breanne Tidemann in Alberta. We’ve done two years in Saskatoon and one year in Lacombe [Alta.]. What we’ve seen is that when we do multiple clippings at Saskatoon, we had really good curtailment of the mustard seed production. The results weren’t quite as good in Lacombe but growing conditions in Lacombe are not great for lentils.

If we just went early, it didn’t work very well, which makes sense since not all of the wild mustard would have emerged. We found that one clipping was maybe enough, but that two was probably better. Use the weed stage as a timing guide for clipping. Clip the weeds when flowering is fully extended above the crop but before seed development. Repeat if necessary.

In cereals, the idea is that you can go beneath the crop canopy because the cereal leaves can slide through the knifes before they’ve elongated while the more rigid stems of a dicot will be cut by that.

We did have some success in wheat. We were reducing wild mustard weed seed production by about one-half. The trouble is, though, we were also clipping off a lot of cereal leaves and heads by going in there because our mustard never really got that tall.

Weed wiping with a non-selective herbicide was used in the ’70s before we had herbicide tolerant crops. There are different commercial machines that have been developed to wipe the weeds above the crop canopy. We are starting to use a Garford Weedfoil, which is a better design than a lot of the older ones. It has a wider felt area that is pressure-saturated with herbicide. In our research on wild mustard, glyphosate worked best followed by dicamba. We had some problems with dicamba because it worked well for weed control the first year and didn’t work that well in the second year. We did have dicamba injury with weed wiping with both the normal and the low-volatile formulations. The vapour damaged the lentils a lot, so we threw that treatment out.

In terms of the timing and the seed yield, earlier, but not too early, was often the best. Under the best possible situations, it could work well, but it didn’t always work that well. Weed wiping also was able to reduce the next year’s repopulation that emerged by about onehalf, which was much better than we thought it would be because we thought there was enough in the seed bank that reducing the seedbank would take longer.

We are going to scale the research up and do further work with 2,4D and glyphosate for weed wiping, but given how good the results have been from the clipping, we are going to combine the two projects.

Presented by Todd Gaines, Colorado State University, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Feb. 27-28, 2018, Saskatoon.

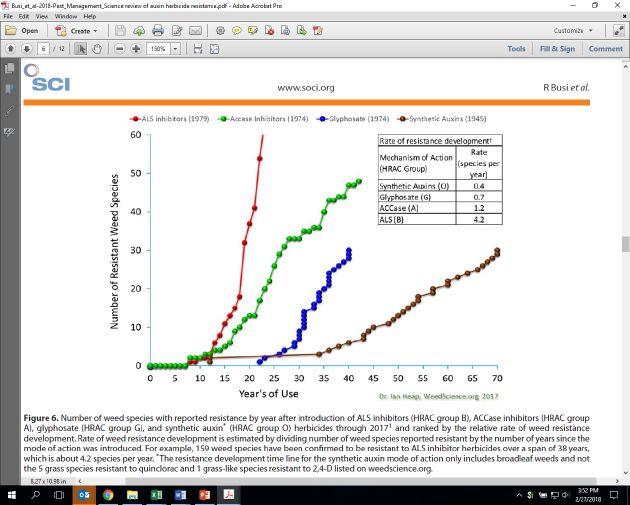

Group 4 herbicides, synthetic auxins, were used on an estimated 366 million hectares globally in 2014. The top three modes of action are Group 9, glyphosate, at 508 million acres, then Group 2, ALS inhibitors at 477 million hectares, and then Group 4. We know that Group 9 and Group 2 have a lot of selection pressure for resistance, but what about the Group 4?

There are quite a number of different active ingredient herbicides within Group 4. The herbicide 2,4-D is by far the most commonly applied one – and also the oldest – at nearly 162 million hectares treated in 2014. In second place, dicamba is used on 50 million hectares. Since we’re talking about kochia, fluroxypyr was used on nearly 29 million hectares treated in 2014.

Group 4 is also a mode of action in which there’s still active discovery going on for new active ingredients. Within the last several years, aminocyclopyrachlor was introduced, and even more recently, halauxifen-methyl.

It is often stated that the Group 4 synthetic auxin herbicides, have a lower incident of resistance than other herbicide modes of action. Within the first 35 years of use, there were only a couple of species reported resistant, and two of those were reported in the ‘50s. It’s certainly safe to say that the rate of occurrence of resistance to Group 4 was slower, and a lot of these species, while resistant, didn’t necessarily have major impact on the choices that managers had to make. However, in the last few years, and perhaps over the coming years, there may be some different trends as the herbicides in this group will be getting more use.

Kochia is one of the most significant Group 4-resistant weeds, with a number of populations reported in Canada as well across the US. In Canada, there are other species that have been reported. These include spotted knapweed, hempnettle, false cleavers, and wild mustard. The very first 2,4-D resistant species reported was wild carrot in Ontario. Another species in the U.S. that is definitely of importance is waterhemp, Amaranthus tuberculatus. There are now at least two populations reported as resistant to 2,4-D. Also in the U.S., particularly in the Pacific Northwest – Oregon, Washington, Idaho area – prickly lettuce resistance to 2,4-D has been confirmed.

In Australia, wild radish has some populations resistant to 2,4-D, and that certainly has some economic impact. In Europe in cereal production, there is corn poppy resistance to 2,4-D. Recently in South America and Argentina, smooth pigweed has been reported as resistant to both 2,4-D and dicamba.

<LEFT: Several different mechanisms of resistance have been identified in kochia.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TODD GAINES.

<LEFT: Fifteen to 20 per cent of kochia in Colorado is resistant to both glyphosate and dicamba.

BOTTOM: The occurrence of resistant weeds

PHOTO COURTESY OF IAN HEAP, WEEDSCIENCE.ORG.

Plants can be resistant in three different ways. One is through the target site. There are proteins where these synthetic auxins bind and have their signalling effect. These auxin receptor proteins are called TIR1 or AFB, and another group of auxin co-receptor proteins are called Aux/IAA. When you apply a synthetic auxin herbicide, it brings the TIR1 or AFB protein to the AUX/IAA and takes it away to be destroyed. That allows genes to be activated, and it turns on all kinds of plant growth pathways. The plant cells lose their regulation of growth – that is division, expansion. You get all the symptoms you’re familiar with from synthetic auxins – epinasty, leaf curling, leaf cupping – that eventually starts to lead to cell death, and ultimately the plant dies. When resistance develops, mutations in these target site proteins interrupt this process.

What’s important to know is that both dicamba and 2,4-D are structurally similar to the auxin hormone, indoleacetic acid (IAA) in plants. This seems to be what allows these herbicides to signal through that two-protein sandwich at the target site.

A second way resistance may develop is through a transport system at the cell level where the synthetic auxin may not enter the cell, or it may leave the cell at a different rate.

A final mechanism is metabolic. For example, the new crops with auxin resistance traits, Roundup Ready Xtend (dicamba) and Enlist (2,4-D) have a gene that rapidly metabolizes dicamba or 2,4-D, respectively. We know this is a way that plants can become highly resistant to the auxin herbicides.

Until the last several years, the mechanisms of resistance weren’t really known in Group 4 herbicides. Some work was done in Canada on wild mustard to help understand the physiology, but it hadn’t quite gotten to the level of a specific gene. Recently at the Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative, some work from Danica Goggin and her group showed reduced 2,4-D translocation in wild radish. Of those three basic types of mechanisms– translocation, metabolism, or target site – it suggests translocation may be the reason for resistance there.

Kochia resistance

Dicamba was first introduced in 1967, and resistance was first reported in kochia around 1990. It’s interesting that through the mid-’90s, various sites would report lack of kochia control with dicamba. Then, it would be investigated, could often be confirmed, but then, over subsequent years, it really wouldn’t be a problem in that field anymore. So, kochia seemed to have this pattern of appearing and going away, which is obviously different than the patterns for resistance to ALS inhibitors where resistance was discovered and became widespread fairly quickly.

The situation, at least in Colorado and a good part of the Southern Great Plains, is that glyphosate resistance has become fairly common in kochia. The tank mix that’s common for fallow is glyphosate plus dicamba. Fluroxypyr is getting used more where glyphosate and dicamba resistance are becoming common. We haven’t yet found fluroxypyr-resistant kochia populations in Colorado. This becomes really important because we have a set of populations, 15-20 per cent, that are resistant to both glyphosate and dicamba. Certainly there are some clear management challenges once you start getting multiple resistance stacked in populations.

Over the years, kochia resistance has been shown that it’s a single gene, dominant inheritance. An interesting thing about kochia and dicamba is that typically we see that dicamba-resistant kochia can be controlled by the label rate for a pre-emergence application. But what’s important to know is that dicamba has some residual activity that is decreases as the product breaks down in the soil. The concentration at which the resistant kochia can grow is going to occur earlier than for susceptible. Practically speaking, you won’t have as long a residual time using dicamba pre-emergence for control of kochia if you have a resistant population.

One of the things that happens when you treat plants with a synthetic auxin herbicide is the plant makes a gas called ethylene. We found that the gene that leads to ethylene production is turned on in susceptible kochia after treatment but it is not turned on in resistant kochia. There’s also another gene that’s known to be activated by synthetic auxin treatment. In the susceptible kochia it is activated but not activated very much in resistant kochia. This suggests that the dicamba goes into the resistant plant, and it’s not having the signalling effect that it normally would. We also tested metabolism, and we found that it wasn’t metabolism. This is a target-site mutation and is pretty exciting to share.

Sherry LeClere with Monsanto looked at the target-site mutation. In the Aux/IAA protein, there’s a conserved part of these proteins that has a certain amino acid signal. The alignment of the receptor and co-receptor proteins is critical in order for the auxin to have the signalling and to take this protein away and have it destroyed. In the susceptible kochia, it’s a “G” amino acid as it normally would be, but in the resistant kochia, there’s a mutation, and now it’s an

“N” amino acid. This mean that the auxin no longer binds.

Researchers also looked at a “yeast 2-hybrid assay.” What they found is that the two proteins AFB and Aux/IAA, are interacting in the presence of dicamba. When there is a resistant mutation, they don’t interact, and the dicamba doesn’t turn on all the growth pathways, and this is why they’re resistant. This is fantastic scientific work and something that we didn’t know before.

A DNA marker has been developed so we can genotype this mutation. We tested four additional resistant populations from Colorado. One had the same mutation. The other three did not have the mutation. We also tested a dicamba-resistant population from Kansas, and it did not have the mutation in this particular AUX/IAA gene. This suggests that some dicamba-resistant populations out there have this mutation, and others don’t have it. So, therefore, we have at least a second type of mechanism out there that we need to figure out. But this helps us know that we could test for this mutation and at least give a determination on whether that is present in a population.

To summarize what we know about dicamba resistance in kochia: we know that they are resistant to both pre- and postemergent applications, but the high end of the label rate of pre-emergent does control resistant kochia. Keep in mind that you’re going to most likely have less residual, and you’ll be still applying selection pressure for potentially an even higher level of resistance. Growers need to think about other modes of action that could be effective pre-emergence on kochia to use as part of that system.

What’s been found so far is that targetsite mutation in this Aux/IAA gene prevents dicamba from binding. It also appears that this mutation has a fitness cost. That makes sense because this pathway is so important for plant growth. If you mess with it, there’s going to be a trade-off. It appears that when kochia has this mutation, it is going to grow slower, and make fewer seeds. In the absence of dicamba, they’ll be out-competed by a susceptible genotype. The implication is that you could potentially have the resistance trait drop in frequency if you were to stop using dicamba. We also suspect that there are at least two different mechanisms for dicamba resistance. In Colorado, in our surveys over years, roughly 30 per cent of our populations now in our no-till system are dicamba-resistant.

The other example of Group 4 resistance that I will mention is waterhemp, Amaranthus tuberculatus. From what I understand, this is something you’re keeping your eye out for in Canada to make sure it’s not introduced. We currently have two populations in the U.S. with reported resistance to 2,4-D. Marcelo Figueiredo, a PhD student from Brazil, has been working on a population from Nebraska and is looking at metabolism. A lot of herbicides are normally selective in crops due to metabolism – that is, the crop breaks it down. Some insecticides, such as malathion, can inhibit that, but if you co-apply certain herbicides and certain insecticides, you can get some crop injury. Malathion, in particular, we know inhibits a type of protein called cytochrome P450, an enzyme that does this metabolism in some plants. We looked at 2,4-D dose response on susceptible and Group 4 resistant waterhemp in the absence or presence of malathion. We found than when malathion was added to 2,4-D, the resistant waterhemp was controlled fairly similarly compared to the susceptible response.

To summarize the message around synthetic auxin resistance, dicamba resistance in kochia is a fairly big issue. For the target-site mutation, we see a fitness cost. In waterhemp, we see enhanced 2,4-D metabolism, and we don’t know yet whether there’s a fitness cost there or not. Both 2,4-D and dicamba are expected to be used more in the U.S., Canada, and soon in South America with Roundup Ready Xtend and Enlist. These are very important herbicides in many crops so it is very important to be thinking about resistance management. They’ve been around for 60-plus years, and we want to keep them working.

The North American Kochia Action Committee was formed last year where university, government, and industry scientists from the U.S. and Canada are working together. The goal is to co-ordinate our strategies for what we’re doing on herbicideresistant kochia research, including thinking about funding. We anticipate that this will facilitate collaborations among industry, government, and university around communication and extension as well as research. We hope to develop very effective stewardship guidelines, bulletins, and best management practices so that everyone thinks about integrated management for kochia and how to sustain the management tools that we have.

Presented by Tom Wolf, Agrimetrix Research and Training, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Feb. 27-28, 2018, Saskatoon.

Ihave had an evolution of views on herbicide resistance as it pertains to spraying. I’ve always believed that if you want to combat resistance with application technology, you need to spray less. After all, herbicide resistance is a direct consequence of relying too much on herbicide sprays.

But last year, I read a paper in Weed Science by Parsa Tehranchian that changed the way I looked at things.

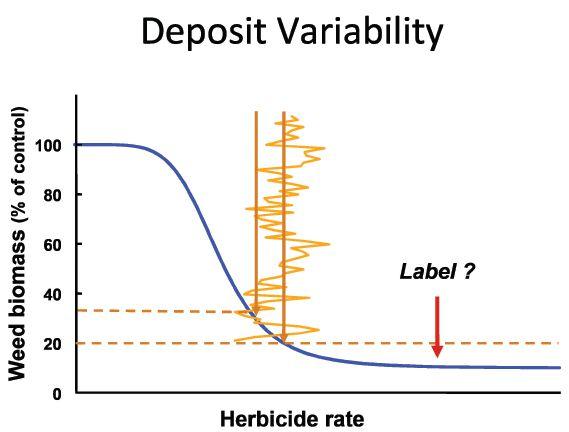

Tehranchian et al. did a study where they showed that in three generations, sublethal applications of dicamba evolved polygenic resistance in Palmer amaranth. They chose a completely susceptible population of Palmer amaranth and applied sub-lethal doses of dicamba to it, and allowed the survivors to cross-pollinate and go to seed. They took that seed and repeated the experiment at a number of doses, always choosing sublethal rates and picking survivors to again cross-pollinate. After three such generations, they had a GR50 ratio of approximately 3:1. Suddenly, my interest was piqued because I felt that sublethal application is something we could do something about. Spray technology can prevent the repeated application of sublethal doses in the same location.

The first way to prevent sublethal rates is with turn compensation. Turning with a sprayer can result in a large variation in application rate. Fields have topographical features, obstacles like sloughs that are repeatedly gone around year after year. When the sprayer turns to go around an obstacle, the inside wing turns a smaller radius than the outside wing. When we go around an obstacle of 60 feet in diameter with a 120-foot boom, the inside nozzle is overdosing by a factor of three and the outermost nozzle is underdosing by about 40 per cent. That may be sublethal. If you do that year after year after year because of a permanent feature, I would suggest these permanent features is where I would look for resistance onset for outcrossing species.

That’s what turn compensation is all about. We have to provide a higher dose to the outside wing and a lower dose to the inside wing. Technology to take care of this variation during turns and is called pulse width modulation (PWM), a technology that is capable of controlling the flow of each individual nozzle on a spray boom

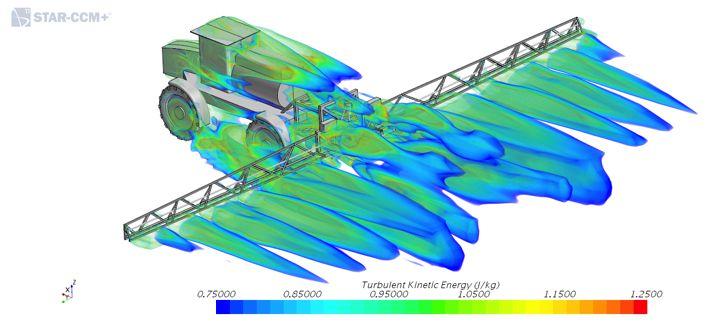

ABOVE: Turbulent Kinetic Energy.

Number

Volume

independently. As the sprayer is making, say, a right-hand turn, the furthest right nozzle puts out a lower dose and the furthest left nozzle is putting out a higher dose. Turn compensation, coupled to PWM, is commercially available. These systems are coming into the market at $25,000 to $65,000 for a 120-foot boom.

Turn compensation provides true, uniform distribution of the spray across the width of the boom, but there are limits to what the technology can do. If you want to go around a stone pile with a diameter of 10 feet, the capabilities of the system will be grossly exceeded. In PWM, the ratio from lowest to highest dose, from the inner to the outermost wing, is about four- to eight-fold, depending on the system. In practice, that means going around an object with a diameter about one-half the boom width.

Another element to sublethal does application is called “boom sway and yaw,” which is basically the boom movement up and down and forward and backward as you navigate across a field. This can produce quite variable results. Research by Syngenta in Europe found that improper height and stability of the boom resulted in an 80 per cent loss of performance of a soil-applied herbicide for black grass control.

Boom yaw is a forward-backward movement of the boom. If you’re going 10 miles an hour the boom jostles a little bit and the left boom is moving forward faster than 10 miles an hour, and the right boom is moving back. The result is under-applying and overapplying on opposite sides of the boom.

Technology from Amazone, a German manufacturer of farm equipment and sprayers, uses an accelerometer to determine when the boom is moving forward and backward. The movement is compensated for with hydraulic cylinders to keep the boom as steady as possible. They have also added on pulse width frequency modulation (PWFM) that also varies the dose to compensate for boom movement. This system knows exactly how fast the boom is

moving and gives it a higher dose or a lower dose along the boom as necessary. The system is called SwingStop pro. Using this system, if you drive through a field and your boom is swinging back and forth, you’re always putting on the right dose. However, there is a limit to the technology and that again is the dynamic range that the PWM system is capable of. SwingStop pro was featured at Agritechnica in Hanover in November 2017.

We’ve covered two ways that spray technology can reduce the application of sublethal doses, both using PWM: turn compensation and boom yaw compensation.

But there are other trends in spraying which are more difficult to correct. One such trend is to drive ever-faster, which creates aerodynamic challenges for uniform spray deposition. The faster the speed, the more fine droplets leave the spray plume and become subject to displacement due to forward motion-induced turbulence. Funded by Western Grains Research Foundation, Hubert Landry with PAMI Humboldt did some modelling of turbulence behind sprayers through “computational fluid dynamics” (CFD). CFD is software that can document, among other things, turbulent kinetic energy – TKE – an indicator of turbulence. At 18 miles per hour travel speed, structural components on the sprayer such as booms and wheels can create significant turbulence.

Smaller droplets are doing a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of efficacy. They provide coverage that’s important for contact herbicides, and they can go places in the canopy that larger droplets can’t reach. These are also the droplets that are most likely to be displaced because of their small size and low mass. So, we have to understand how to manage that and how to mitigate that displacement.

I was with a co-operator in 2016 doing a fungicide trial. When we were done he went to finish spraying a field. He had someone bring a drone and take photos from the air. He was going 27 miles

an hour because he wanted to finish the field that day. He left a long plume of fine droplets behind the sprayer. He lost control over those droplets. They were at the whim of the turbulence induced by the sprayer, and could be move up or down or across from where they were intended to deposit. If weather conditions were poor, i.e., windy, then this could make things even worse. That’s an issue.

What proportion of the spray volume is actually at risk? It’s a small dose, probably less than 10 per cent, depending on the spray quality. However, this small dose represents the majority of the total number of droplets in the spray. In other words, the ones that provide that elusive and important “coverage” are the ones most affected by turbulence.

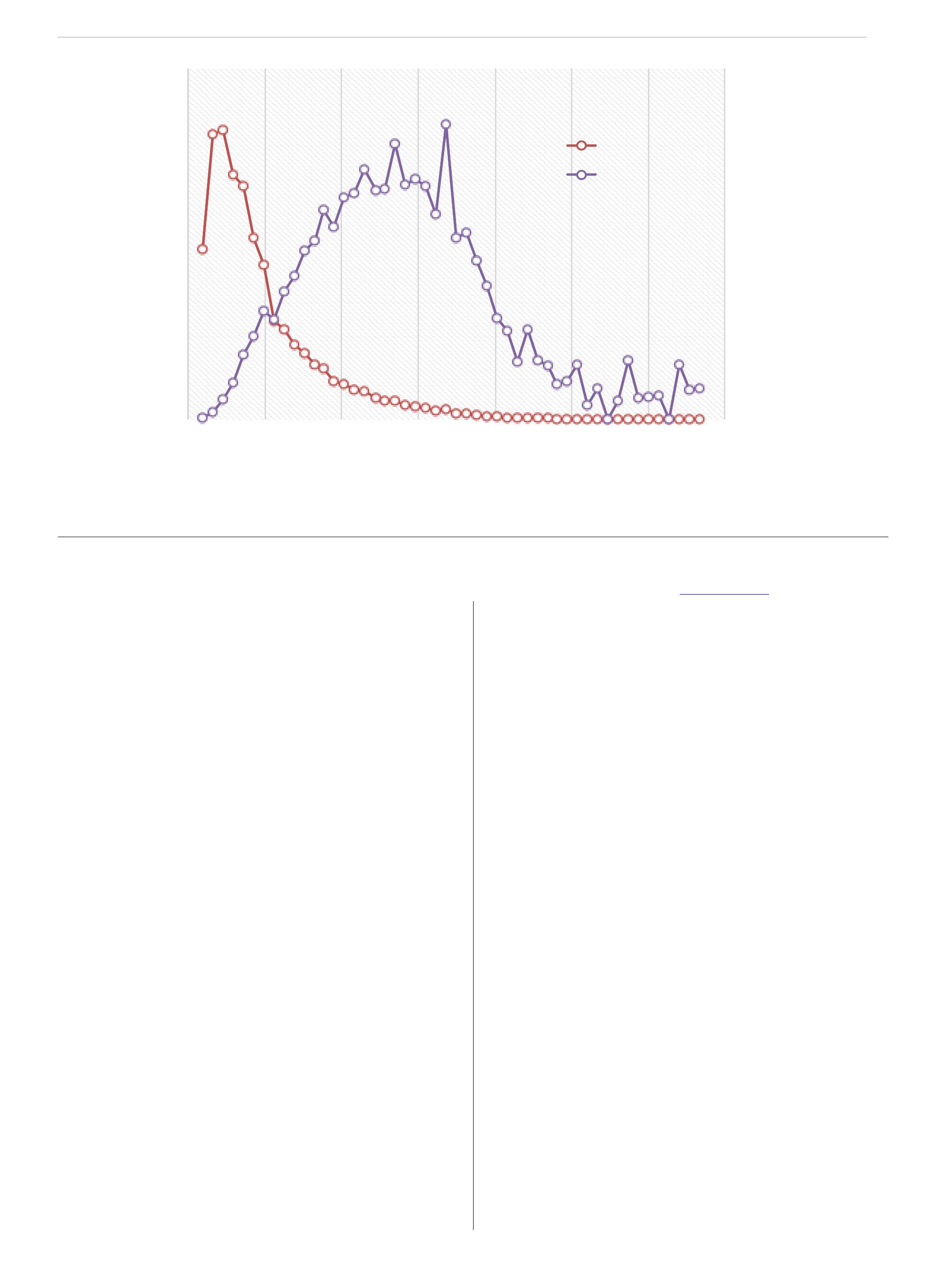

At Ohio State, we conducted a study that looked at deposit uniformity with a high-resolution analysis of a square metre in bare soil and stubble and with a medium and fine spray. Five-centimetre diameter petri plates were placed at 12.5-centimetre intervals, so there were 64 data points in the square metre.

We noticed that the spray was overdosing by 50 per cent and underdosing by 30 to 40 per cent in some cases. We were surprised by the variability but in subsequent studies have come to accept this as normal. We don’t observe problems due to this variability because the label rate over-applies to compensate for the variability. But if, for whatever reason, we are a little bit less than perfect on the application, we are going into sublethal territory.

Imagine poor growing conditions that challenge the herbicide performance. Or later growth stages. Or antagonism from a tank mix or poor water quality. In all cases, the label rate protects the user from noticing lower performance. But these conditions do bring us closer to the edge.

When we analyze the relationship of herbicide performance and dose when the dose is just at the sublethal stage, we see how variability can he a problem. As we enter the sublethal doses, the herbicide response curve assumes a convex shape. At this stage, the benefit from overdosing is much smaller than the penalty from under-dosing. When we superimpose the typical variability in dosing, such as the one from our Ohio State study, we quickly learn that a variable dose is also a less efficacious dose. Perhaps the loss of overall efficacy is enough to cause sublethal doses to reach certain weeds, allowing survival that can eventually lead to polygenic resistance development.

deposit for any spray pass with the Coefficient of Variation (CV), which is the standard deviation of the deposit expressed as a percentage of the mean. Looking at the total inventory of drift data that we had from 1986 to 2011, we observed three statistically significant trends:

• Spray deposits had higher CVs with higher wind speed.

• Higher travel speeds resulted in higher CVs.

• Finer sprays had higher CVs.

The move that our industry has made to coarser sprays has been very good. We now need to repeat that accomplishment for travel speed and wind speed.

There is new technology that I think is worth thinking about. Tramontana Agro Technologies is a Toronto company who has introduced WEEDit, a system made by Rometron, a Dutch company. A WEEDit boom is equipped with sensors at one-metre spacing. Every sensor has five channels, so the resolution is 20 centimetres.

The sensors emit a light that can identify living plants by sensing chlorophyll. If chlorophyll is present, the nozzle directly behind that 20-centimetre section will apply a burst of spray to target the plant that triggered the system.

Tramontana has sold five units in Western Canada. It works for pre-seed and post-harvest applications, but is not suitable for broadcast crop spraying because it cannot yet differentiate crops from weeds.

Boom height and travel speed is one of the areas where we need significant technological improvement. Even sprayers with automatic boom height control have trouble keeping the sprayer boom level to the ground because of faster travel speeds.

In 2006, we worked with PAMI to study spray deposit uniformity at various travel speeds and boom heights. The variable deposit uniformity we saw across the boom was improved with slower travel speeds.

When conducting spray drift trials, we always measure 24 on-swath deposit plates. They’re always in the same locations. We make a pass, and then we see how much landed on the swath and how much landed down-swath. We can calculate the variability of the spray

WEEDit is also pulse width modulated, and capable of a speed up to 25 kilometres per hour. With PWM, turn compensation is possible, and dose is held constant at most travel speeds.

This kind of technology facilitates the delay of the onset of resistance through the tank mixing of effective modes of action because it makes tank-mixes affordable. If you’re only spraying 20 per cent of the field because you have a weed sensing technology on the preseed burn-off, a $50 tank mix becomes a $10 tank mix.

An Alberta farmer purchased this system in 2017 and uses it on his 15,000-acre farm. He saved $82,000 last year. His average saving was 80 per cent. This system can pay for itself in just a few years, depending on the farm size. It was met with much success in Australia, particularly for custom spray operators. It’s an important system, and it has implications for management of resistance.