TOP CROP MANAGER

4 4R nitrogen management for wheat and canola

By Donna Fleury

6 Fine-tuning nitrogen best management practices By Carolyn King

9 Variable nitrogen fertility management on canola at the field scale

By Donna Fleury

12 Wheat variety influence on fungal communities

By Julienne Isaacs

14 In search of a better soil N test

By Carolyn King

Editorial Director, Agriculture: Stefanie Croley

Associate Editor: Alex Barnard

Western Field Editor: Bruce Barker

National Account Manager: Quinton Moorehead

Publisher: Michelle Allison

Group Publisher: Diane Kleer

Media Designer: Curtis Martin

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Essentially, all life depends upon the soil. There can be no life without soil and no soil without life; they have evolved together.”

This quote is attributed to Dr. Charles E. Kellogg, a former soil scientist and chief of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Bureau of Chemistry and Soils, in the USDA’s 1938 Yearbook of Agriculture – long before any of the research we report on in this issue came to fruition (or was even heading toward the research pipeline).

Imagine how amazed Kellogg would be if he came across this digital edition (and I’m only talking about the stories included – I won’t even get in to how technology has changed since he left the earth). But his words still remain true: there can be no life without soil and no soil without life, and our stories in this issue, the third installment of our summer Focus On digital edition series, dig deeper (pun intended) into the importance of soil fertility and proper crop nutrition.

As you move through the season, we hope you’re inspired by the research and trial results you’ll read about in these pages. There’s much to be done this time of year, but taking care of the soil that’s working so hard to help your crops grow still needs to be a priority.

/topcropmanager

Looking for something to listen to while you’re working this summer?

Stay tuned to topcropmanager.com/podcasts to catch the latest episodes of our summer series on Inputs – the podcast by Top Crop Manager. You can also catch up on all of the episodes from the Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture podcast series on AgAnnex Talks at agannex.com.

Side-banding N at seeding is still the least risky and most efficient N application method.

by Donna Fleury

Currently, the most commonly recommended best management practice (BMP) for nitrogen (N) application is side-row or mid-row band applications at the time of seeding. These placement options dramatically reduce the potential for environmental losses while maintaining seed safety. However, some growers are looking for ways to improve seeding efficiency and increase N management flexibility, particularly for crops with high N requirements like wheat and canola.

A recent project demonstrated different N fertilization strategies according to the 4R principles of the right source, rate, time, and place for fertilizer application. It was conducted to help farmers make informed decisions while taking into consideration both the advantages and potential disadvantages of the various options.

“In 2017, we initiated field trials with spring wheat and canola near Indian Head to demonstrate the response to varying rates, forms, and application method/timing options of N fertilizer,” explains Chris Holzapfel, research manager with Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) in Saskatchewan. “We continued the demonstrations in 2018 with similar treatments for both wheat and canola, which are both rotationally and economically important crops in Saskatchewan.

“Canola is highly responsive to N fertilizer and often receives fertilizer rates amongst the highest for crops commonly grown in Saskatchewan, while CWRS (Canadian Western Red Spring) wheat is sensitive to N management with regard to both yield and grain protein concentrations.

“In 2019, we continued only the wheat demonstration trials, and also replaced the fall in-soil banding treatments with a spring surface broadcast timing/placement option,”

Holzapfel continues. “This allowed us to explore different aspects of 4R N management, and although I like the fall in-soil bands agronomically, I don’t think it is something many producers actually do with the granular products we were looking at.”

The demonstration trials in 2017 and 2018 included 12 N fertilizer treatments for both wheat and canola, and used various N alternative management strategies: incorporating untreated urea, urea ammonium-nitrate, ESN, Agrotain and SuperUrea, and contrasting placement options, including side-banding, pre-seed surface broadcast or in-soil bands, and post-emergent (split) applications at the target rate (130 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha) for

wheat and 145 kg/ha for canola).

For wheat, the range of target N rates (soil N plus fertilizer) evaluated were 30, 80, 130 and 180 kg/ha, and for canola the target N rates were 35, 90, 145 and 200 kg/ha. The 2017 demonstrations began in the spring, while the 2018 demonstrations started with fall-applied treatments in October 2017. Various data were collected over the growing season and from harvest samples, including NDVI to assess N response during the season, grain yields and grain protein for wheat.

“We took a lot of care to select the appropriate N rates for the trials,” Holzapfel explains. “The rate selected was intended to allow us to detect differences in N

management, and not be excessive or severely limited to the extent that they would not be representative of the crops being grown. We recognize that the rate may have been a bit limiting for yield, and the optimal rate is likely somewhat higher.

“The best practice for determining fertilizer rates remains soil testing and knowing your soil and yield potential for individual fields to try and select an appropriate rate.”

Overall, the results showed that it is hard to beat side-banding at time of seeding as the gold standard for getting nitrogen into the soil as close to the time of crop uptake as possible, under most environmental conditions. “With the dry conditions in both years, the surface applications did not generally perform as well as sidebanded N,” Holzapfel says.

“The broadcast N ended up stranded at the surface for quite a while until there was some rain to move it down into the soil. It is well accepted that surface-applications of N need either incorporation or adequate precipitation to move the fertilizer into the rooting zone and minimize losses. While the broadcast N is stranded at the surface there is a risk of volatilization losses, and until the N moves down into the soil, it is not available to the crop. This would explain why the surface applications did not generally perform as well as side-banded N.”

The benefits of side-banding N in wheat were particularly evident in the 2017 protein levels. Although there were no significant differences in wheat yield across the various treatments that year, protein was substantially higher when all of the N was side-banded under the environmental conditions encountered.

“The side-banded N protein levels were in a class of their own; all of the other treatments where pre-seed surface broadcast or split-applications were utilized had significant lower protein. This is consistent with previous research, which has shown that early insoil applications are generally most advantageous under dry conditions while, under more optimal conditions, N fertilizer placement and timing of application tend to be less critical. This would, to a large extent, explain why the surface applications did not perform as well as side-banded N, especially when protein was considered.”

With respect to formulations, urea and UAN tended to be least effective when applied as a pre-seed broadcast application while urea, Agrotain, and SuperUrea all performed similarly in the splitapplications. Both application dates of surface-applied N were subject to stranding at the soil surface and volatilization, as the most significant rainfall events of the season occurred over five weeks after the pre-seed applications and prior to the split applications in 2017.

“Under optimal moisture conditions, timing and placement methods tend to be less important while, under extremely wet conditions, enhanced efficiency (EEF) products and split-applications generally have the greatest potential to be advantageous,” Holzapfel explains. “In very wet years, environmental losses can be high regardless of application method depending on the formulation. It is in these years that denitrification inhibitors or split-applications are likely to be most beneficial.

“The most common examples of EEF products include polymer coatings (i.e. ESN), volatilization inhibitors (i.e. Agrotain) and volatilization/nitrification inhibitors (i.e. SuperUrea). Enhanced efficiency N products are more expensive than their more traditional counterparts. However, this higher cost may be justified by the potential improvements in efficacy and logistic advantages of alternative fertilization practices.”

In 2019, the demonstration trials continued with wheat only, comparing fertilizer treatments of fall broadcast, spring broadcast or spring side-band at seeding, with all the same forms evaluated in 2018. Holzapfel notes that so far the trial is in good condition and all placement/timing options appear to be performing reasonably well, even in the broadcast treatments, where early spring rains did move the N into the soil in a reasonably timely manner. Although there aren’t any visible deficiencies, treatment differences may be detected when the results are finalized this fall after harvest for yield and protein measures.

“On the other hand, we set up a similar demonstration with winter wheat in the fall of 2018, comparing a range of different N rates applied as either a side-band at seeding, spring surface broadcast, or a 50:50 split application. The spring broadcast N applications were made in the last week of April 2019 and, here, the fertilizer sat for quite a while on the surface before there was sufficient rain to move it into the rooting zone,” Holzapfel says.

“In this case, it looks like there definitely was an advantage with the full amount of N side-banded at the time of fall seeding, which ensured the winter wheat had access to the N when it was needed. We will have final results on yield and protein once harvest is completed.”

“Although side-banding N remains the benchmark and is the least risky and most efficient application method for N regardless of form, growers do consider all kind of alternatives, mostly for logistics reasons,” Holzapfel says. “Under the 4R N management practices, first and foremost consider the rate, placement method and timing of N applications. If all of those factors are done right, then getting the right form may be less critical.

“In my experience, if you do a good job of managing N under normal conditions in well-drained fields and not excessive moisture, there doesn’t tend to be a lot of difference in performance amongst the major forms. If conditions are such that the N is more susceptible to losses, then consider some of the options that can protect against the types of losses that are most likely to occur. Of course, results can vary widely from season to season with weather conditions.”

Evaluating enhanced efficiency fertilizers to reduce N losses while maintaining yields.

by Carolyn King

The idea with enhanced efficiency nitrogen fertilizers (EENFs) is to get more nitrogen to the crop when the crop needs it, while reducing nitrogen losses. Minimizing those losses is important for improving production efficiency, environmental stewardship, and access to markets that have an interest in sustainably produced crops. A key nitrogen loss issue for Prairie crop production is nitrous oxide.

The University of Saskatchewan’s Richard Farrell is evaluating the effects of EENFs on nitrous oxide emissions to develop practical options for improved fertilizer management.

“Most growers have heard about 4R nutrient management, with the right source, right rate, right time, and right place. Using an enhanced efficiency product would be part of that right source,” explains Farrell, an associate professor in soil science.

“What we are trying to do through this research is to tweak the fertilizer best management practices to maintain the agronomic and economic potential of cropping systems while reducing any environmental impacts from the fertilizers.”

He explains why nitrous oxide emissions are such an important

issue for Prairie agriculture. “Nitrous oxide is 300 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Depending on the country and other factors, about 65 to 80 per cent of total nitrous oxide emissions can be from agricultural soils, and the biggest source of those emissions is synthetic fertilizers. Although nitrous oxide emissions are generally relatively small on a per-acre basis, there are tens of millions of farm acres in Western Canada. Moreover, about 80 per cent of all synthetic nitrogen fertilizer used in Canada takes place in the three Prairie provinces.” So, to maintain access to markets that are concerned about carbon footprints, Prairie crop production systems will need to lower their nitrous oxide emissions.

Along with reducing nitrous oxide emissions, adoption of EENFs could also decrease other nitrogen losses, helping crop growers to increase their nitrogen use efficiency. Farrell says, “In Prairie conditions, nitrogen use efficiency is probably around 40

ABOVE: One of the sites in Farrell’s previous study on enhanced efficiency fertilizers.

Modes of action used in enhanced efficiency nitrogen fertilizer (EENF) technologies: [1] polymer coating to control (slow) release rate of urea; [2] urease inhibitors to block urea hydrolysis; and [3] nitrification inhibitors to delay the oxidation of ammonium (NH4+) to nitrate (NO3-). Nitrous oxide is N2O.

to 50 per cent. So, about 50 to 60 per cent of the nitrogen that you apply doesn’t get used by the crop in the year that it is added. We would really like to increase that efficiency.”

Based on what people in the industry have told Farrell, adoption of EENFs in Western Canada is around 10 to 12 per cent at present, which is up from about two per cent five or six years ago.

Farrell’s current EENF project builds on the results from his previous three-year evaluation of EENFs under Saskatchewan conditions, which was completed in 2018. That earlier study was part of a tri-province project with Mario Tenuta at the University of Manitoba and Guillermo HernandezRamirez at the University of Alberta. Tenuta led the overall project.

The three studies evaluated a wide range of nitrogen fertilizer products and compared fall versus spring applications. All three studies involved wheat and used the same fertilizer treatments, measurement protocols and so on, to enable the researchers to bring all of the data together for a Prairie-wide perspective. In addition, each study had its own particular emphasis – Farrell’s study evaluated the fertilizer treatments under irrigated and dryland conditions in Saskatchewan’s Dark Brown soil zone.

The fertilizer treatments mostly focused on urea and urea-based EENF products. They included: urea; polymer-coated urea; urea with a nitrification inhibitor; urea with a urease inhibitor; urea with both a nitrification inhibitor and a urease inhibitor; and an unfertilized check. The project also included a few treatments us-

ing anhydrous ammonia with and without a nitrification inhibitor.

Polymer-coated urea is intended to slowly release nitrogen to the crop. The urea-based inhibitor products slow down the microbial-mediated processes that convert urea into other forms of nitrogen, including forms that are easily lost from the soil.

The researchers’ primary focus was to assess the effect of the different treatments on nitrous oxide emissions, although they also looked at wheat yields. Because of that focus, all the fertilizer products were applied at the rate recommended by a site-specific soil test.

He explains, “Normally with an enhanced efficiency product, you can use a reduced nitrogen rate. For example, if your soil test recommendation is 100 kilograms per hectare, then you could put on perhaps 80 kilograms because you can lower the rate by about 20 or 25 per cent – some of the manufacturers suggest even greater reductions – to get the same yield. But reducing the amount of fertilizer also reduces nitrous oxide emissions, and we didn’t want to confound what was going on by changing the nitrogen amounts. So, everything was applied at the soil test recommendation.”

As a result, even if some of the EENF products had increased the crop’s nitrogen use efficiency, it probably wouldn’t have shown up as a higher yield under most conditions. The recommended rate would usually have provided enough nitrogen for the crop to achieve its potential yield and protein levels.

However, he adds, “In our second year, it was looking like there might be some yield effects, but then the whole trial was wiped out by hail. That didn’t really

affect the greenhouse gas part of what we were doing, but it meant that there was no yield data.”

Farrell and his research group found some big differences in the nitrous oxide amounts emitted from the different treatments in the Saskatchewan study.

“Any product with a nitrification inhibitor really reduced nitrous oxide emissions. Those products were also the most consistent – whether they were applied in the fall or the spring, they gave large emission reductions,” he says.

“A nitrification inhibitor keeps the nitrogen as ammonium. If the fertilizer didn’t have the nitrification inhibitor, the urea would rapidly convert to nitrate, which would then be available in the spring when there is a lot of moisture from the snowmelt. And that would result in large nitrous oxide emissions.”

Urea with a urease inhibitor consistently reduced emissions when spring-applied, but not when fall-applied. During the study, fall was milder than usual, so the fall-applied urease inhibitor products were put on when the temperatures were still mild, which may have impacted their performance. He explains that urease inhibitors slow the breakdown of urea to ammonium, but with the prolonged mild weather there was time for this conversion to occur in the fall. Then, once the ammonium was formed, it was probably converted to nitrate rather quickly, resulting in high emissions during spring snowmelt.

“The polymer-coated product was inconsistent across everything,” Farrell notes. “There was one year at both irrigated and non-irrigated sites where it did reduce emissions, but in the other years it had no effect. So for this product in particular, the environmental conditions seemed to really control what was going on.”

The Manitoba and Alberta studies had similar results to the Saskatchewan study, with the same products giving the same types of effects.

step:

and agronomics Farrell’s new project takes his EENF research to its logical next step. “We knew that we needed more information about how these products would perform from an agronomic standpoint. Could we maintain yields while dropping the fertilizer amounts? Lowering the amounts would also give us an added reduction in nitrous

oxide emissions,” he says.

“And we needed to see how the products performed with some of the other major crops. So we chose canola for this project.”

This new project is a collaboration with Kate Congreves in the University of Saskatchewan’s department of plant sciences. It is funded by Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund and the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission.

The fieldwork for this three-year project will be starting this fall and will take place at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. The fertilizer treatments will include: urea; urea with a nitrification inhibitor; urea with both a nitrification inhibitor and a urease inhibitor; and an untreated check. The project is focusing on the EENF products that performed best in the previous study.

The EENF treatments will compare the soil-test nitrogen rate and the reduced nitrogen rate recommended by the EENF manufacturer.

The treatments will also compare spring and fall applications. “We really want to see if we can minimize any environmental impacts from a fall application while maintaining the yield benefits that come from the products,” Farrell notes.

“One of the conclusions of the tri-province project was that fall nitrogen applications are at a higher risk for nitrous oxide losses. So, usually the recommendation is to not apply nitrogen in the fall. But, if you’re going to fall-apply it, then do it when the weather is really cold so the microbial communities are working really slowly and aren’t going to covert a lot of the nitrogen to nitrate,” he explains.

“As farms just keep getting bigger and bigger, the importance of

time management increases. In some cases, managing your time is more important than managing other things. [Fall fertilizer applications are a way for growers to manage their heavy spring workloads.] Also, fertilizers tend to be a little cheaper in the fall. So, a lot of people want to do fall applications.”

His research group will be collecting data on the crop’s nitrogen uptake, nitrogen use efficiency, yield and oil content, and measuring the nitrous oxide emissions.

“We are hoping to be able to demonstrate that you can use lower amounts of these enhanced efficiency products. You pay a little bit more for them, so to make your money back you either have to increase your yields or lower the amount of nitrogen that you are applying,” Farrell says.

“If you can use lower amounts of nitrogen and still maintain yields, that would reduce your nitrous oxide emissions and lower your carbon footprint. So, a lot of the commodity groups are interested in this type of research because the European Union and other countries, as well as companies like Walmart, are looking for products with a low carbon footprint.

“In addition, if we can show that using enhanced efficiency products can reduce the environmental impact of a fall nitrogen application while maintaining the agronomic potential, it would be another advantage for Prairie farmers.”

Farrell emphasizes, “If you follow best management practices, you get environmental benefits. They go hand-in-hand. So, we’re just trying to figure out the best way to manage nitrogen in a sustainable fashion.”

Economic return and fertilizer use efficiency from variable rate management varied between fields and between farms, as did canola yield.

by Donna Fleury

Nitrogen fertilizer is a costly input for crop production, and canola is a heavy nutrient user, making fertilizer management an important strategy for growers of the crop. The concept of precision farming or variable rate management of fertilizer has attracted a lot of attention, and growers often question how it can work in their management systems and if it can be improved upon.

“There are a number of organizations and crop consultants who have developed systems to variably apply fertilizer to optimize the return on fertilizer and optimize crop yield,” says Alan Moulin, honorary research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Brandon, Man. “Building on some earlier research we had completed in Manitoba, we wanted to take the next step to a broader field-scale project. In the previous study, we monitored crop yield over five years using a yield monitor, and after analyzing the data realized there was a consistent pattern of high, average and low-yielding zones in the field.”

Moulin initiated a four-year multi-site study across Western Canada in 2014 to examine the impacts of variable rate nitrogen fertility programs on canola yield in areas with consistently low, average and high production. During the project, 27 site years of data were collected from commercial farms over four growing seasons in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. The trials were conducted in collaboration with growers on field-scale plots using their own seeding and harvesting equipment. Moulin worked with grower associations in each province to help identify producers who already had three to five years of historical yield maps for their fields to participate in the project.

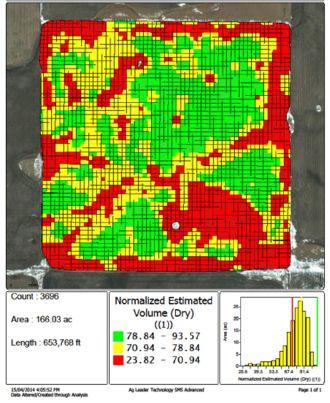

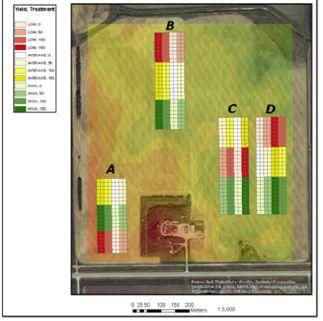

“The study was designed to assess the application of management zones based on the yield maps, and to develop individual field maps showing high, average and low-yielding zones on each field,” Moulin explains. “Based on spring soil test results and the target yield goals for average yield set by each grower, we set up a program to apply four levels of N fertilizer treatments across the field, comparing zero, 50, 100 and 150 per cent of the recommended rates. The other nutrients were applied at recommended soil test rates to ensure they weren’t limiting crop production.”

The yield goals were adjusted for each zone, and producers uploaded the program into their seeder to apply fertilizer variably across their fields and management zones. The size of the treatment

plots was based on two swather-widths wide to eliminate variability. At harvest, the protocols were to calibrate either weigh wagons or local commercial scales to further reduce the variability between farms and combine equipment.

Moulin notes that there was a tremendous amount of data collected across all of the sites and years of the project, with lots of variability between farms, fields and soils. Along with soil test data, other information was collected, such as soil texture, soil pH conductivity and satellite imagery, terrain attributes, and the digital elevation data that is part of yield monitor data collected by the combine. “We have analyzed the yield response to fertilizer over the four years of the project, and overall the results show that the Manitoba N fertilizer recommendations for canola are appropriate,” Moulin says. “The economic return and efficiency of fertilizer use from variable rate management varied between fields and between farms, as did canola yield. Soil properties and the interaction with canola variety, growing season precipitation and temperature also varied considerably with respect to yield. The 100 per cent N rate worked well across the high and average yielding zones, and to a lesser extent to

the low zones; however, the fertilizer rate at 150 per cent actually resulted in a little less yield than the full rate. My colleague, research scientist Mohammad Khakbazan has completed a detailed analysis, which has been submitted for publication.”

The analysis shows that variable rate application paid off in some fields and in others it did not, relative to applying fertilizer uniformly across the field based on average yields and at 100 per cent of recommendations. Overall, nitrogen and production zones were significant, with variable rate management generating up to a net $65 more per hectare on average, compared to average zones. Variable rate management resulted in about eight per cent less nitrogen use, as nitrogen supply matched crop demand more effectively.

Farm location had significant effects on canola yield, with profitability ranging from -$91 to +$352 per hectare. The data can also be used to develop profit loss maps across the field, which can show whether or not those low-yielding zones are making money, or if it may be appropriate to revise the management for those zones and put the priority on the high-yielding areas. Differences in management, including agronomic practices, variety selection and types of fertilizer, as well as soil properties, elevation and terrain attributes all impact fertility and should be considered, along with historical yields, when planning out a variable rate fertility program or studying fields that utilize this technology.

Moulin adds that developing and integrating an effective variable rate fertility program is very complicated, so carrying out field-by-field analysis is paramount to

potential success. “Yield maps are an extremely valuable source of information, although data collection can be time-consuming, and if equipment is not working at harvest, growers likely can’t afford to take the time for repairs. In this project, we did have several other fields that we had to eliminate because, for various reasons including technical hurdles with the prescription maps or yield monitors not working, we weren’t able to collect the data.

“Nevertheless, that yield data is quite useful and does reflect overall trends in terms of relative variability of yield within the field, so it is worthwhile for those growers who want to consider this as part of their management. Thorough preparation well in advance of seeding, combined with post-harvest or pre-seeding soil sampling are recommended to ensure accuracy when carried out at busy times, especially in regions with short growing seasons.”

With the large amount of data collected in the project, researchers continue to analyze and report on various aspects. “We have identified one particular terrain attribute that may account for a lot of the variability, so we are looking at the potential to improve prescription maps by including that terrain attribute,” Moulin says.

“The next step includes looking at relationships between soil properties and terrain attributes, which also reflects drainage in systems, where water is flowing, soil erosion and nutrient management. Further research is required to account for fertilizer requirements of new canola hybrids and other new crop varieties, and the N-supplying potential of soil as it varies with management between farms and in the landscape. These studies will identify management or soil properties that resulted in significant canola yields observed for zero per cent of recommended N fertilizer

Comparison of average canola yield at the four levels of N fertilizer treatments across low, average and high-yielding management zones over the four years of the project.

rates on many farms in the previous study.”

The field-scale research and model development to assess different management systems in a broad range of crops continues, now led by research scientist Taras Lychuk. This three-year project is part of a larger collaboration with other researchers and part of Living Labs, which will also include assessing consequences of climate change, precipitation and temperature and field hydrology, among other aspects. This model development for assessing different management systems complements precision agriculture management.

This research was supported by a large group of agronomists and technicians across Western Canada. Andrew Kopeechuk (AAFC Brandon Research and Development Centre) developed prescription maps, compiled and organized data, supervised laboratory analysis and provided logistical support to collaborating agencies. Arnie Waddell (AAFC Brandon Research and Development Centre) provided GIS support and compiled remote sensing and terrain data. Rejean Picard (Manitoba Agriculture), Steve Sager (AAFC Morden Research and Development Centre), Don Cruikshank (Deerwood Soil and Water Management Association) and Jason Patterson (AAFC Melfort Research Farm) managed field activities and collected data. Field trials were organized and run by staff from Farming Smarter near Lethbridge, Alta., the North East Agricultural Research Foundation near Melfort, Sask., and the Deerwood Soil and Water Management Association near Somerset, Killarney, Miami and Morden, Man. Staff from the Canola Council of Canada provided support for logistics, administration and extension. The project was funded by AAFC and the Canola Council of Canada.

Study results show there is potential to direct plant-AM fungi symbiosis through breeding.

by Julienne Isaacs

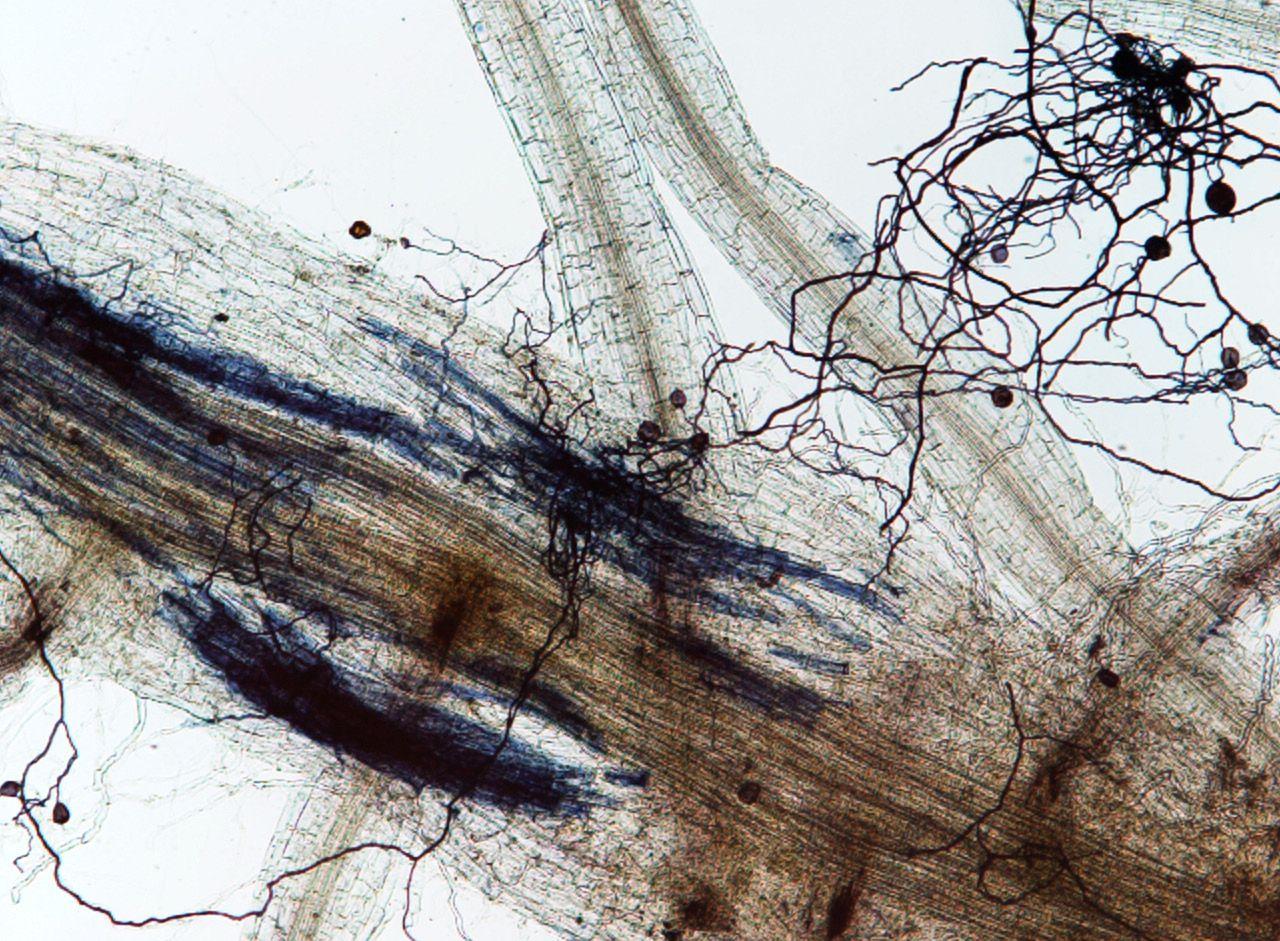

Arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) are symbiotic relationships between plant roots and fungi. Research has only described a relatively small number of fungal species, but it is known that they can help crop plants extract nutrients from the soil and protect them from environmental stressors.

In 2018, researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Swift Current Research Station in Saskatchewan published a study looking at interactions between durum wheat genotypes and AM fungal communities.

Because not much is known about how interactions between plants and soil micro-organisms work, it’s a happy accident when new wheat genotypes have beneficial relationships with AM fungi. The purpose of the study was to lay some foundations for future breeding projects that could deliberately take advantage of that compatibility.

“Growing wheat varieties with improved compatibility with beneficial soil micro-organisms can be a powerful way to manage soil micro-organisms and a good strategy to enhance soil nutrient

use efficiency in agro-ecosystems,” explains Oualid (Walid) Ellouz, the publication’s first author.

Ellouz, who now works as a research scientist at AAFC’s Vineland Research Station, says plant-soil microbial interactions have the potential to decrease crop dependence on fertilizer, reduce farm input costs and ultimately increase the value of Canadian wheat.

Ron Knox, a plant pathologist and geneticist at Swift Current, was involved in the study’s big-picture planning. He says early on he was hoping to see whether it was feasible to combine durum genotypes with species of mycorrhizal fungi to promote crop growth.

But the question was naïve, he says, due to the complexity of soil flora and the difficulty of evaluating which relationships are beneficial to the crop.

ABOVE: Part of a durum wheat root naturally colonized by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Some hyphae are seen radiating from the root surface, bearing several large spores of the fungus; others are within the root tissues.

“It’s a really difficult thing to measure,” Knox says. “There is a vast array of different interactions – you have these three-way interactions as environmental interactions are superimposed over two types of organisms coming together, and soils are variable and change from region to region, and those soils are exposed to different climates.”

A field study comparing 32 genotypes of durum wheat was set up at two sites in Swift Current and Regina. The genotypes chosen included a set of five landraces that had been introduced to Canada before 1920, as well as cultivars developed at various times in the subsequent period, including six recent cultivars.

Knox says the team wanted to include wheat that was not exposed to modern farming practices, such as the use of inorganic fertilizers; most varieties are now selected and bred using these cultural practices. The study’s breadth of genotypes allowed them to evaluate whether there was a difference in how older and newer varieties performed.

In previous research, Ellouz adds, the team had found little evidence that landraces regulate AM symbiosis better than modern varieties. “Plant breeding had inconsistent effects on AM symbiosis, and cultivars with a range of AM symbiosis efficiencies from unimproved to inefficient have been developed,” he says.

Wheat was planted into soil that had been summer fallow the previous year. The rotation at the Regina site was summer fallowwheat, while the rotation at the Swift Current site was fallowwheat-oats.

Ellouz says durum wheat roots and rhizosphere soil samples were collected from the top zero to 7.5 cm soil layer in the plant row. DNA was then extracted from the samples, and then amplified using PCR; AM fungal communities in roots and rhizosphere soil were determined using next-generation sequencing.

The study found that durum wheat genetic selection seems to have a positive impact on plant-AM fungi symbiosis, Ellouz says.

“Four of the six newest high-yielding durum wheat genotypes (Commander, Enterprise, Eurostar, and Brigade) seemed to favour the proliferation of fungal orders Diversispora and Claroideoglomus, and exclude the fungal order Dominikia,” he says. The latter, Ellouz adds, has been shown to be negatively related

Regina. “Climate, soil properties, and field management influence the composition of AM fungal communities,” he says.

“No matter the cause of variation in the AM fungal community from site to site, it appears that site characteristics had a stronger influence than plant genotype did.”

Knox says that the results of the study make it clear that there is potential to direct plant-AM fungi symbiosis through breeding, but this is still “way down the road.”

“Growing wheat varieties with improved compatibility with beneficial soil micro-organisms can be a powerful way to manage soil micro-organisms,” Ellouz says.

to wheat productivity and N and P uptake efficiency; the former two are both positively linked to wheat productivity and N and P uptake efficiency.

“The recent durum wheat genotypes might trigger a positive feedback reaction from the soil fungal community,” Ellouz says.

But very different root- and soil-inhabiting AM fungal community structures were found at the two sites. Ellouz believes this is perhaps due to the use of summer fallow every other year in

“There are a lot of questions that need to be answered before breeding can coincide with the microbiology research which would be needed to look at whether there is an increase in productivity,” he says.

Ellouz adds that researchers will first need to learn which alleles of which genes in wheat are involved in favourable relationships between wheat roots and fungal communities.

But it’s a worthy goal: this kind of symbiosis can lead to increased yields with lower inputs, which will reduce crop dependence on fertilizers and benefit producers’ bottom line.

“Wheat genes responsible for AM fungi compatibility need to become a breeding target to reduce crop dependence on fertilizer, environmental impacts of fertilization and farm input costs,” he says.

Developing an improved test that more accurately predicts nitrogen fertilizer needs.

by Carolyn King

University of Saskatchewan researchers are working to create a soil nitrogen (N) test that will provide a better measure of how much N the soil could supply over the growing season. That crucial information will allow more accurate estimates of the crop’s fertilizer requirements, helping growers to reduce fertilizer inputs and minimize N losses to the environment.

“Over the last few years, there have been a lot of anecdotal reports that N fertilizer recommendations based on the standard soil N test didn’t really align with what farmers were seeing in terms of yield response. And we have been finding the same thing in some of our research plots,” says Richard Farrell, an associate professor in the university’s department of soil science. He is co-leading this research project with fellow department of soil science professor Fran Walley.

“We’ve had plots in recent years where the soil test came in with relatively low available N and a recommendation for the application of 125 kilograms of N per hectare. Then we’d add anywhere from zero to 220 kilograms per hectare and get no fertilizer response at all, or there was a small fertilizer response up to perhaps 90 kilograms and then nothing beyond that. So, the test was telling us to put on more nitrogen than we actually needed.”

As a result, Farrell and Walley started questioning whether the standard soil N test that people have been using for the past few decades is adequately capturing the soil N pool that provides nitrogen during the growing season.

Farrell explains that the standard test just measures the inorganic soil N pool, which is the nitrate and ammonium in the soil. That’s the N pool that is immediately available for plants to use. Organic N needs to be mineralized – converted by soil microbes into inorganic forms – before plants can use the nitrogen. The inorganic N pool is relatively small compared to the organic N pool.

Furthermore, the standard test only provides a snapshot of the inorganic N pool at the time when the sample is collected and analyzed. “But the inorganic N pool changes relatively rapidly. For instance, if you sample when the soil is dry, you’ll get one value for inorganic N, and if you sample two weeks later after a big rainfall event, you might get a different value,” Farrell says.

“So, while the test does give an indication of the total amount of nitrogen that is present in the soil, it doesn’t necessarily give you a good feel for how much soil N could become available during the growing season.”

He notes that some labs also conduct what are called mineralizable N tests, which measure the amount of ammonium and/or

nitrate released when a soil sample is incubated under certain conditions in the lab. “These tests estimate long-term N release based on the measured N release under lab conditions and then use the results to estimate the amount of N that could be available over the growing season. So, whereas the tests are providing an estimate of what might be there, we’re not really sure what soil N pool they are actually capturing.”

Farrell sees a couple of possible reasons why the old soil N tests no longer provide a reliable basis for predicting fertilizer needs.

“These soil N tests worked really well when they were developed years ago, but soil and crop management on the Prairies have changed dramatically since then. When these tests were developed, no-till really wasn’t very popular as compared to now. A lot of cropping systems were monoculture systems, like continuous wheat, and summerfallow was part of rotations.

“These days, rotations include cereals, oilseeds, pulses, and we’re now looking at incorporating cover cropping and intercropping into these systems. These types of changes all have effects on the soil organic matter pool and the soil N pool. We just haven’t done a good job of keeping up with monitoring these reservoirs and seeing what is available,” he explains.

“Also, while some soil tests recommend that you sample down to about 24 inches deep in the soil, many people only sample the top 12 inches or so. So, there might be some N deeper in the soil that we are not capturing with the testing, and that N becomes available as the crops put their roots down.”

Of course, no test will always perfectly predict a crop’s N fertilizer uptake, as moisture and temperature conditions during the growing season strongly influence the amount of available N in the soil and the crop’s ability to take up N. So, Farrell and Walley are looking to provide a measure of how much N could potentially become available from the soil in a year with typical weather conditions.

Because the reliability of N fertilizer recommendations is so important for agriculture and the environment, various researchers are working on this issue. “People in different regions across the country, from Atlantic Canada to B.C., are trying to develop different versions of tests that look at this potentially available nitrogen, and we’re the ones doing it here,” Farrell notes.

He and Walley are particularly interested in whether soil protein N might provide a better basis for evaluating how much N could potentially become available over the growing season.

They first started thinking about this possibility a few years ago, when their graduate student Adam Gillespie was working on glomalin.

“Glomalin is a protein produced by mycorrhizal fungi [soil-borne fungi that form a beneficial relationship with a plant’s roots]. Glomalin is extremely stable; it’s thought to contribute to soil aggregation and is viewed as sort of a soil carbon and nitrogen bank account,” Farrell says.

Because there is a great deal of scientific debate about the exact nature of glomalin, one of their studies looked at what is actually measured by the lab procedure designed to extract glomalin from soil samples. They discovered that the procedure not only captures glomalin but also a lot of other proteins and lipids that soil microbes produce from plant and soil sources.

The protein mix extracted by this procedure is often called ACE protein; ACE stands for autoclaved citrate extractable soil protein, which is a description of the extraction procedure. Only a small percentage of ACE protein is actually glomalin.

During and after this glomalin research, Walley and Farrell talked a few times about whether the ACE test could be looked at as a better way to estimate the amount of organic N that is likely to be mineralized during the growing season.

“Although the glomalin protein is thought to be relatively stable – especially over the short term – many of the other proteins, amino acids and sugars, and other N-containing compounds extracted by the procedure are more easily broken down, thereby making some of this N available for crop uptake. The question is: how much?” Farrell says.

“However, the ACE procedure is kind of clumsy and it can be really finicky. It didn’t look like something that could be adoptable on a commercial scale. So, we put the idea on the back burner.”

While he worked on other research during the subsequent four or five years, Farrell kept thinking about this idea. He came up with a possible way to tweak the ACE test to make it faster and less finicky so that it might be more practical for use in commercial labs.

“But the missing information was: Can you use this test to predict fertilizer recommendations better than the current test? So, we put this project together.”

project so far

Farrell and Walley are currently finishing the first year of this threeyear project. Their objective is to develop a practical lab test that better indicates the amount of soil N that is potentially available

during the growing season, providing a better estimate of a crop’s fertilizer needs.

The project team has already collected soils from across Saskatchewan’s different soil zones, which reflect different production potentials. They sampled down to a depth of at least 24 inches to check whether there is a significant amount of N below the usual 12-inch sampling depth.

They have been characterizing those soils in terms of their basic soil properties and various measures of different soil N pools, including: total N; total soil organic matter; inorganic N; mineralizable N; and ACE protein N.

“Ultimately, the idea is to use this information to build an algorithm or a model that allows you to take the soil test value and predict crop uptake, so we need to work with a wide range of soils,” Farrell explains.

The team has also conducted fertilizer N plot studies with canola and wheat at six Agri-ARM sites. (Agri-ARM is a network of applied research and demonstration organizations located across Saskatchewan.) They applied a wide range of N fertilizer rates, from much lower to much higher than the standard soil test recommendation, to create complete yield response curves. Then they will determine how well the results from the five different N tests correlate with fertilizer uptake.

Farrell and Walley’s hypothesis is that soil protein N will be the best predictor of yield response to applied N fertilizer. For this initial phase of the project, they are using the regular ACE test to measure soil protein N. If soil protein N is indeed highly correlated with the crop’s N fertilizer uptake, then they’ll move into the second phase of the project, which is to develop a more rapid version of the ACE test.

“If we develop a test that provides a better indication of how much N the crop can actually access from the soil, then that should allow us to make better predictions of N fertilizer requirements. And presumably that will mean recommending lower amounts of nitrogen fertilizer. In which case, it will have a bottom-line benefit for growers: if you’re putting on less fertilizer, then you’re not paying for as much,” Farrell concludes.

“You’re banking more on the soil to provide some of the N that the crop needs.”

This project is funded by the Western Grains Research Foundation, Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission, Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission and Alberta Wheat Commission.

August 3 – 8, 2020

Join us for the launch of The Harvest Hub – we’re sharing harvest best practices and insights to help Canadian farmers prepare for a safe and successful harvest season!

• Pre-harvest crop management

• Cover crop agronomy

• Grain storage & aeration

• Data management

• Product showcases

• Market insights

Stay tuned to topcropmanager.com or subscribe for free at topcropmanager.com/subscribe to ensure you don’t miss any of the 2020 Harvest Hub highlights!

Interested in a content, product demo or sponsorship partnership with the Harvest Hub? Connect with us today to secure your spot! (availability is limited)

Quinton Moorehead | National Account Manager 204-720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

Michelle Allison | Publisher 204-596-8710 mallison@annexbusinessmedia.com

Six women who are making a difference to Canada’s agriculture industry have been chosen and will be highlighted through podcast interviews on AgAnnex Talks starting June 15.

Stay updated by visiting AgWomen.ca or subscribing to the podcast at AgAnnex.com