TOP CROP MANAGER

Canola is one of Canada’s fastest-growing crops, and it’s in high demand for good reason. Canadian-grown canola contributes $26.7 billion to the Canadian economy each year, according to a study conducted by the Canola Council of Canada in 2017. And as the world learns more about the advantages of canola – including the myriad benefits of canola oil, canola meal and other end-use products – the growth of the Canadian canola industry contributes more than 250,000 jobs (adding up to $11.2 billion in wages) to the Canadian economy as well.

But as you well know, with great power comes great responsibility, and growing such a high-value crop doesn’t come without challenges. Pests, diseases, weather and poor agronomic decisions can have devastating effects on canola yield and quality. Fortunately, fascinating research is taking place in Canada and around the world to keep canola profitable, and we’ve gathered some particularly interesting projects together for this issue of Top Crop Manager Focus On: Canola.

ON THE COVER

Marcus Samuel and his team have developed a bio-solution for green seed in canola.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY.

Marcus Samuel, an associate professor at the University of Calgary who’s pictured on the cover of this edition, spoke to Bruce Barker, our western field editor, about his efforts to mitigate green seed in canola – an issue that causes more than $150 million in losses every year. Samuel and his team are working to identify a gene that helps with the problem. You can read more about his research on page 9. We also explore a rotation study, weather impacts on quality, mixing hybrids for better yields and much more.

Our next edition, Focus On: Crop Management , covers an array of topics including tips for improving corn yield, sustainable fertilizer management and subsurface drip irrigation. Watch for it later in July. Until then, happy growing.

Editor:

Associate

Western Field Editor: Bruce Barker

Associate Publisher: Michelle Allison

National Advertising Manager: Danielle Labrie

Group Publisher: Diane Kleer

Media Designer: Jaime Ratcliffe

ABOVE: Information from the clubroot genome could result in markers for clubroot pathotypes, which would be much faster and cheaper than current pathotyping methods.

Genome sequencing provides new information on clubroot and the potential for new advances.

by Carolyn King

The impacts of clubroot on susceptible canola cultivars are usually pretty obvious – the plants look droughtstricken and have large, irregular swellings (galls) on their roots. But the pathogen itself has remained somewhat enigmatic. Now a team of researchers mostly from Western Canada, led by Hossein Borhan and in collaboration with scientists from England and Poland, has sequenced the clubroot genome. This work is generating insights into the pathogen and how it functions, and is providing a springboard for future advances in clubroot management.

The clubroot pathogen, Plasmodiophora brassicae, attacks plants in the Brassicaceae family, including canola, mustard, broccoli and cabbage. This unusual pathogen spends its complex, multi-stage life cycle hidden in the soil and inside plant cells.

“Plasmodiophora brassicae was first described by the Russian biologist Mikhail Woronin in 1878 as the pathogen of clubroot disease. Since its discovery, there has been progress in understanding

some aspects of the pathogen’s biology, such as its life cycle, infection and disease development, and the genetics of host resistance to clubroot. However, until recently we had very little knowledge about other aspects of the pathogen’s biology, such as its genome and genes that contribute to its virulence and growth in the host,” says Borhan, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon.

Progress in understanding the pathogen has been slow mainly because Plasmodiophora brassicae is difficult to study. “The pathogen is an obligate parasite. That means it can only grow and reproduce when living inside the host plant. So we can’t culture it, we can’t do experiments in Petri dishes and so on that we can do with other pathogens,” explains Stephen Strelkov, a professor at the University of Alberta.

Borhan adds, “It is one of the rare pathogens that is a multicellular pathogen that lives completely inside a plant cell. The majority of

plant pathogens live either entirely between the cells or they produce feeding organs inside the cells, but they don’t reside completely inside the cell. Interestingly, clubroot is the only example I know of a eukaryotic pathogen that lives completely inside the cell.” Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus, unlike prokaryotes, such as bacteria, which don’t. Plasmodiophora brassicae belongs to a diverse group of eukaryotes called protists.

To better understand this major pathogen, Borhan, Strelkov and the rest of their team, who were from various research agencies, started their clubroot genome study in about 2008.

Borhan explains the clubroot pathogen offers some challenges for genome sequencing. “Since the pathogen cannot be cultured, DNA for genome sequencing needs to be extracted from root galls. This causes contamination of the pathogen’s DNA with other soil microbes and plant DNA. In addition there could be more than one clubroot pathotype present within the galls. You don’t want a mixture of isolates because that would make sequencing and genome assembly very complicated. So the unwanted DNA needs to be removed.”

Fortunately Strelkov’s lab had prepared single-spore, purified isolates for all the clubroot pathotypes, or strains, known in Canada at that time – identified as pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8.

For the genome sequencing work, the samples for these five pathotypes were obtained from various parts of Canada. “Pathotypes 3 and 2 were single-spore isolates derived from Alberta samples, pathotypes 5 and 8 were from Ontario samples, and pathotype 6 came from British Columbia,” Strelkov notes.

The researchers generated draft genomes for pathotype 3 and pathotype 6 because these two pathotypes have some significant differences from each other. “Pathotype 3 is one of the most important and virulent pathotypes on canola. It was the predominant pathotype on Canadian canola and the one that could cause the most disease on canola before resistant cultivars became available,” Strelkov explains. “Pathotype 6 is mainly a pathotype of cruciferous vegetables; it doesn’t

do very much in terms of attacking canola.” The two pathotypes also differ in their geographical distribution: pathotype 3 is very prevalent on the Prairies, and pathotype 6 is mainly in Eastern Canada and British Columbia.

The researchers also “re-sequenced” pathotypes 2, 5 and 8 to get a more complete picture of all the Canadian pathotypes. Resequencing refers to genome sequencing and assembly that uses a standard or reference genome as a template, so re-sequencing these other pathotypes was easier than creating the first draft genomes of pathotypes 3 and 6. The researchers used pathotype 3 as their reference genome for re-sequencing.

They then studied the characteristics of the clubroot genome and determined how the pathotype genomes differed from each other.

The researchers also did some RNA sequencing experiments to explore how the pathogen causes the disease in the host plant and how it takes nutrients from the host. For this work, they used two host species, Brassica napus (canola) and Arabidopsis thaliana(a small plant in the Brassicaceae family that has a small genome).

Although a European group published a genome of a single clubroot isolate a few months before Borhan’s group published its genome work, the two groups were working in parallel. The sequencing work by Borhan’s group, which involved many more genomes, had already been completed when the European paper was published.

One of the most important findings from this work was that clubroot has a small, compact genome. “The genome is about 24 megabase pairs, which is small compared to most eukaryote pathogens, like fungal pathogens of plants. For instance, the clubroot genome is roughly half the size of the blackleg genome, which is about 45 megabase pairs, and it is around one-tenth the size of some of the oomycete genomes like the pathogen that causes late blight of potato,” Borhan says.

Their work also showed clubroot has about 11,000 genes –about the same number of genes as in the bigger genomes of fungal pathogens. Clubroot’s smaller genome is owed to the fact that it has relatively small spaces between the genes, called intergenic spaces, and a relatively low number of repeated DNA sequences, compared to many other organisms. Borhan explains intergenic spaces are important in gene regulation. Having such small intergenic spaces affects how the clubroot genes are regulated and how they are coordinated in terms of expression; for instance, it may mean there are overlapping regulatory sequences for multiple adjacent genes.

Another discovery related to how the pathotype genomes differ from each other. “We looked at the profile of the mutations in the DNA across the genome – the profile of single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNP] – and we found that pathotypes 6 and 3 are strikingly different from each other,” Borhan explains.

“Pathotypes 2, 5 and 8 were really similar to pathotype 3, so together they form one group, and pathotype 6 stands alone. That correlates with their distribution and host specificity, since pathotypes 2, 3, 5 and 8 are all found mainly in the Prairie provinces and they all infect canola, while pathotype 6 is mainly in the east and infects vegetable brassicas.”

The researchers learned about the prevalence of chitin synthesis genes in clubroot; chitin is a fibrous substance that occurs in the exoskeletons of arthropods, like crustaceans, and in the cell walls of fungi. Borhan notes, “Chitin has been reported in clubroot resting spores before, but we noticed that the expression of chitinrelated genes goes up when the spores are forming and when they are germinating. We believe chitin has a very important role in protecting the spores so they can survive in the soil for a long time [up to about 20 years].”

As well, they identified genes in clubroot that could affect the regulation of cytokine and auxin in the host plant. Strelkov explains, “These two plant hormones play a role in the development of the typical galls of clubroot on the roots, so this finding has potential implications for how the pathogen is causing the disease and how it is causing symptom development.”

The researchers found the clubroot genome lacks genes for making thiamine (vitamin B1) and some amino acids. “It looks like the pathogen is completely dependent on its host to get these nutrients; it can’t synthesize them by itself. It helps to explain why the pathogen won’t grow on its own,” Strelkov says.

The researchers also figured out how the pathogen might be taking up nutrients from its host. Borhan explains, “We found a novel group of transporters that we believe are involved in the uptake of nutrients from the plant. They have some similarities to bacterial transporters and some similarities to eukaryotic transporters, so they are a bridge between prokaryote and eukaryote transporters. This has not been reported for any other organism that we know of. Our collaborators in the U.K. are now investigating the role of these transporters.”

One of the areas the Canadian collaborators are now delving into relates to how the pathogen infects its host and how that differs between the pathotypes. “In any pathogen, there are many, many pathogenicity genes; we call them effectors or virulence genes. For example, there are several hundred of these effectors in blackleg. Our prediction is that there are close to 600 of them in clubroot. So to get to the bottom of how they work together to overcome the plant defences is a daunting task,” Borhan says. “We have cloned some of these effectors and are testing them in plants. We have indications

that some of the effectors from pathotype 3, for example, make the plant more susceptible. Hopefully our work and other people’s work will provide some clues about clubroot virulence, for example, why pathotype 3 is more aggressive on canola than 6.”

Most of the funding for their clubroot genome sequencing work was from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through a program called the Canadian Crop Genomics initiative. The researchers also obtained some funding from Growing Forward 2 through collaboration with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry and the University of Alberta to study the virulence effectors.

Borhan and Strelkov see various ways the information from this research could be used.

In the short term, information about how one pathotype differs from another, such as the SNP profiles, could be used in developing molecular markers for pathotyping clubroot isolates. Markers would make it much easier for researchers to track changes in the pathogen strains, which would be very helpful for canola breeders and growers.

Strelkov explains that, currently, the pathotypes are identified based on testing the isolates on a standardized set of host plants, referred to as differential hosts, and then seeing which particular hosts get the disease. “We inoculate the isolates on many differential hosts and then let the plants grow for six to eight weeks [to assess the disease symptoms]. That takes a lot of labour to do the inoculations and space to grow the plants because the testing must be in a biosecure environment,” he says. “With molecular markers, you could potentially do the extraction of DNA and then run the tests in a day or two. So you would get the same information in a much, much shorter time for a much lower cost. And you could potentially run many more samples than we do now. At present we have only so much room in our greenhouses, so we always have to carefully consider which samples to include.”

Strelkov adds, “This research provides some very important information as a starting point. Since 2013-14, we have found 11 new clubroot strains that are capable of overcoming the genetic resistance we had against the older pathotypes, including resistance to pathotype 3. Potentially, as we move forward, we could get genome information about some of these new pathotypes that could help us to understand where they came from and how they differ from the older pathotypes and maybe provide clues as to how they can overcome resistance and so on.”

Borhan and Strelkov believe the information from the clubroot genome opens up many possibilities for research that could lead to new ways to control the disease. For example, perhaps scientists could find a chemical or biocontrol option that would affect chitin or some other factor important to spore survival. Or perhaps, as they learn more about the pathogen’s infection process, they might find ways to make changes in the host plant to disrupt that infection process, resulting in stronger and more sustainable disease resistance.

“We hope that what we have generated will be a tool and resource for the research community in Canada and worldwide to tap into and learn more about the biology of clubroot and to come up with new ways of tackling the pathogen,” Borhan says.

Visit us online at www.topcropmanager.com for more on plant breeding.

Long-term residual effects of alternative N management practices

by Donna Fleury

Nitrogen (N) fertilizer management continues to be a priority for farmers and researchers, with a large research focus on the effect of N management in the year of implementation. However, researchers also want to understand the longer-term implications of N fertilizer strategies and decisions in a cropping system.

“We were interested in understanding the cumulative effect of N management practices applied over time and how that may help to identify risks and benefits associated with specific management decisions,” explains Ramona Mohr, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Brandon, Man. “We had conducted a four-year rotation study beginning in 2010 to look at the effect of various N management practices on a wheat/ canola rotation. When that rotation study ended, we decided to monitor the study site for an additional two years to see what effect the previous N management practices had over the longer-term.”

The focus of the original management study, conducted near Brandon from 2010 through 2013, was to determine the effect of N rate and timing on crop yield, and on N uptake and removal by the crop. The project involved a two-year canola/spring wheat rotation and various N management practices were studied. The study treatments ranged from control plots receiving no N fertilizer to treatments receiving 150 per cent of soil test N recommendations in one of four years.

“In 2013, the final year of the management study, the study produced good wheat yield averaging about 3700 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha), but very poor canola yields due to poor emergence,” Mohr says. “This provided us with a unique opportunity in the follow-up study to compare the effects on N availability of growing a poor- versus higher-yielding crop. Although this study was conducted in Manitoba, results are expected to apply to similar ecozones in Saskatchewan.”

The objectives of the follow-up study were to determine the effect of previous N management on plant-available N levels in two subsequent growing seasons (2014 and 2015). Researchers also wanted to measure the effects of a preceding crop failure versus a productive crop on N availability in the two following growing seasons.

In 2014 and 2015, wheat receiving no N fertilizer was established across the entire experimental site of the previous canola-wheat rotation. In both years of the study various measurements were taken, including plant stand, grain and straw yield and N concentration, protein, test and seed weight. Soil samples were collected periodically over the course of the study including fall samples at a depth of zero to 15, 15 to 30 and 30 to 60 centimetres.

“The results of the study showed that there were residual effects of both preceding crop and preceding N management in 2014 and in 2015,” Mohr explains. “In comparing the results in 2014, we found higher grain yield and increased N availability following the poorly-yielding 2013 canola crop compared to the higher-yielding 2013 wheat crop. This was likely due, at least in part, to lower N demand and removal by the 2013 canola crop compared to the wheat crop in 2013, which utilized that N to grow the crop and was taken off in harvested grain. The results confirm what we would generally expect to see, but the study allowed us to quantify what those differences were.”

On average, the results in 2014 showed that those treatments that included a one-in-four year application of the higher 150 per cent N rate resulted in increased crop N uptake, fall soil nitrate content, and available N supply compared to those treatments that included a one-in-four year application of no N. By 2015, the effects of preceding treatments appeared to diminish somewhat. However, fall soil nitrate content and available N supply followed a similar trend as in 2014.

The key is to consider these N residual effects, regularly soil test to know where your N levels are at and make fertilizer decisions accordingly.

These findings demonstrate that preceding crop productivity and N management have the potential to impact N availability in the cropping system in

subsequent years under prairie conditions, and therefore should be considered when making N management decisions. For example, where higher rates of N had been applied in the past, there seemed to be evidence of greater N availability in the subsequent year. Various factors may influence residual N levels in a cropping system, from overlaps in equipment passes that contribute to higher than planned fertilizer N rates in select areas of a field, to growing season conditions that result in lower or higher crop N uptake and removal than expected.

“Therefore, it is important to keep these residual effects in mind when managing N. Soil testing provides a useful tool for measuring how much plantavailable N is in the soil, so that fertilizer management decisions can be adjusted accordingly,” Mohr says. “This soil nitrate, together with N mineralization during the growing season, will contribute to the N supply available to the crop. Knowing what soil test N levels are and looking at what crop N demands are expected to be are important to consider when making fertilizer decisions. The key is to consider these N residual effects, regularly soil test to know where your N levels are at and make fertilizer decisions accordingly.

Gene helps de-greening process.

by Bruce Barker

Green seed in canola is a downgrading factor that causes more than $150 million in losses annually. But researchers at the University of Calgary hope to help reduce those losses with the identification of a gene that helps the degreening process.

“Through some foundational research, we’ve come up with some novel technologies to help with the green seed problem,” says Marcus Samuel, associate professor at the University of Calgary.

Normally, as canola matures, the green chlorophyll gradually disappears and at maturity, the seed is yellow and produces high quality oil. Samuel says studies in his lab have found that frost between 22 to 30 days after flowering results in the green colour becoming fixed in the seed, producing coloured oil with an unpleasant odour and reduced shelf life. Two per cent green seed is tolerated in Canada No. 1 canola and six per cent is tolerated in Canada No. 2 canola.

“Frost can increase green seed [from] six to 20 per cent. Bleaching clays can be used during oil processing, but that is an additional cost,” Samuel says.

De-greening pathway identified in Brassica cousin Arabidopsis thaliana is a plant the scientific community has adopted as a model organism for research into plant biology. It is a member of the Brassicaceae family and closely related to canola. Although it is not an economically important plant, its traits make it a desirable plant for scientific study.

Samuel and his colleagues worked on Arabidopsis to develop an understanding of how de-greening of seed works. They believed that if they could identify the de-greening pathways, the technology could be easily shifted over to canola.

Abscisic acid is an important plant hormone that is part of the de-greening process. Samuel identified an abscisic acid insensitive 3 (ABI3) mutant gene that had a defect in seed de-greening, resulting in green seeds at maturity. By identifying this gene, he was able to prove the ABI3 gene controls two other genes – SGR1 and SGR2 – responsible for embryo de-greening. In the absence of the mutation in the ABI3 gene, the de-greening of seeds occurred naturally.

Samuel then looked at what would happen if he added more of ABI3 into an Arabidopsis plant and subjected it to frost.

By over-expressing the ABI3 gene in Arabidopsis, the plants were able to tolerate a frost better and continued to de-green the seed after the frost. In the Arabidopsis plants without the over-expression of ABI3, the green colour was fixed into the seed after a two-hour frost of -5 to -10 C per day at one, two or three days.

“Most Arabidopsis research stops here as foundational research, but we had this amazing pathway for understanding the de-greening process, and asked ourselves what we could do to exploit this pathway,” Samuel says. “We knew there was this problem in canola and thought we might be able to exploit this research to help the canola industry.”

Arabidopsis thaliana and brassica (canola) diverged 43 million years ago, but have 85 per cent gene sequence similarity. Samuel believed what his lab found with Arabidopsis could be easily applied to canola.

The first step was to isolate the ABI3 gene out of Brassica napus (canola) germplasm and confirm that it worked the same way in Arabidopsis – which it did.

The next step was to take the canola ABI3 gene and over-express it in canola. The team proved over-expressing ABI3 in canola worked very similarly in helping the de-greening process after a frost. The researchers came up with two separate transgenic platforms to allow breeders to move the ABI3 gene into canola germplasm. They also found the transgenic ABI3 gene in canola improved frost tolerance.

Further research also confirmed the over-expression of the ABI3 gene did not change canola yield or alter the fatty acid profile of the oil. Oil content was marginally altered.

The researchers also noticed ABI3 over-expression resulted in a thicker pod wall (replum) that was more resistant to shattering. Looking further into this finding, they found the pod structures were highly lignified, resulting in better shatter resistance, better frost protection for the seed and more resistance to desiccation after frost.

SOURCE @ RIGHT RATE, RIGHT TIME, RIGHT PLACE®

A new 3 year survey has captured data on fertilizer use from 3,292 Canadian growers who have completed the online survey detailing fertilizer use practices on 8.3 million acres of cropland

This is just a snapshot. More information can be unearthed in the full

Thanks to our supporters for making this work possible: Canadian Canola Growers Association, CropLife Canada, Fertilizer Canada, Grain Farmers of Ontario, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, and Pulse Canada. This initiative has been made possible through Growing Forward 2 a federal-provincial-territorial initiative.

ABOVE: Continuous canola or wheat-canola rotations were no better economically.

The economics are similar to a two- or three-year rotation, but blackleg and root maggot start to build up.

by Bruce Barker

With high canola prices relative to other commodities, the temptation to run continuous canola is high. But does it really pay in the short term? A research study shows that net returns aren’t necessarily better, and that insect and disease pressures increase over time.

“We have a study that has been going since 2008 looking at the risk of growing continuous canola compared to rotating out of canola for a year or two. We just received funding for another three years so we will have a 12-year rotation study when it is completed,” says Neil Harker, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta. Harker and colleague Breanne Tidemann summarized research results at Alberta Canola’s 2017 Science-O-Rama.

From 2008 to 2016, continuous canola and one- and twoyear rotations out of canola were grown at five Western Canada locations. Rotations included continuous Liberty Link canola (LL), continuous Roundup Ready canola (RR), LL/wheat, RR/wheat, LL/pea/barley, RR/pea/barley, lentil/wheat/LL/pea/barley/RR.

Fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides were applied as required.

The five sites were in Lacombe and Lethbridge, Alta., and Melfort, Scott and Swift Current, Sask. The crops were directseeded on no-till plots. Most fertilizer was side-banded 0.75 to 1.5 inches beside and 1.2 to 1.6 inches below the seed row, with small amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus also placed with crop seeds. Seeding was performed with air seeders equipped with knife openers, and crops were seeded at optimal depths in nineto 12-inch rows.

Increase in blackleg and root maggot with continuous canola

Blackleg incidence was measured at all sites. Harker says there was a significant decrease in blackleg incidence averaged over all sites when rotations were increased with one or two year breaks in continuous canola.

“There was a similar pattern with root maggot. The more years between canola, there were fewer root maggots,” Harker says.

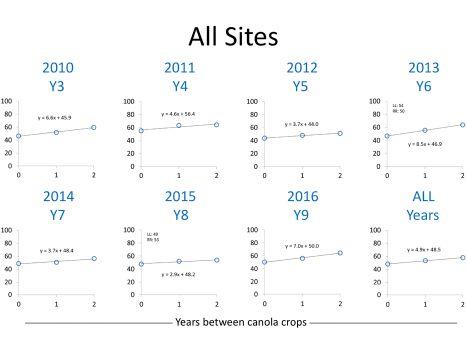

Yield also increased with a break in rotation. With 35 site-

ABOVE: Average canola yield, all sites, zero, one and two years out of rotation. Courtesy of Neil Harker et al, AAFC.

years of data after 2016, the overall trend was predictable, he adds. “When averaged across all years and sites, there was a five bushel increase for each year out of canola.”

The average yield for continuous canola for all site years was 48.5 bushel per acre. One year out and the yield increased to 53.4 bushels while two years out of canola produced an average yield of 58.3 bushels per acre.

One or two years out of canola didn’t always produce higher yield. For example at Lacombe, yield for continuous canola in some years wasn’t always significantly lower. But when averaged across all years, rotating out of canola for one year yielded 3.5 bushels higher, and two years produced seven bushels per acre more than continuous canola at Lacombe.

The Melfort site produced interesting results. In 2016, there was a 17-bushel per acre yield increase for each year out of canola – a 34-bushel yield advantage in a three-year rotation compared to continuous canola. On the other hand, 2013 had no significant difference in yield among treatments. But averaged across all years, yields in Melfort still increased 6.3 bushels each year out of canola.

Economics no better

Harker also ran an economic analysis, since growers would say to him that even though yield was higher with one or two year rotations, they still thought the economics would be better with continuous canola.

For each year of the study, gross and net returns were estimated using yearly commodity and variable costs as calculated by Saskatchewan Agriculture’s annual Crop Planning Guides. Costs were also broken down by soil zone to more accurately reflect input costs.

The results at each site and during each year were variable. During some years more diverse rotations had higher economic returns, while other years no differences were seen.

The Lacombe site was an anomaly. Averaged across all years at Lacombe, continuous Liberty Link canola had greater returns compared to one-third of the diverse rotations. However, those diverse rotations included a year of low-yielding peas as a result of unexpected disease, insect pests and weed resistance (Group 2-resistant cleavers). These issues were and will be mitigated in subsequent years.

“That was the only site across all years where that happened.

Lethbridge and Swift Current were the opposite, where some three year rotations had greater net returns than continuous canola,” Harker says.

At Melfort and Scott, economic returns were not different between rotations.

Averaged across all sites and years, nothing was better or worse than continuous canola. The research challenges the notion that continuous canola will provide higher economic returns, and highlights the risks of increased blackleg and root maggot infestations.

“The message is that people say ‘I have to grow continuous canola because I get the highest net returns.’ But, we don’t have the evidence for that. Perhaps in Lacombe, continuous canola was better sometimes, but overall that wasn’t the case,” Harker says.

Additionally, Harker cautions that the short-term net returns may be similar, but in long-term continuous canola, returns may decrease for continuous canola due to high disease, insect and weed pressure

As part of the study, the researchers also looked at whether canola hybrid mixtures or rotating between canola hybrids in continuous canola could help overcome increasing blackleg and root maggot pressure. The results from 2008 through 2013 have been summarized.

“Mixing cultivars or rotating cultivars over years has been done in cereal crops and there was a benefit,” Tidemann says. “The results in canola did not show any advantage.”

The researchers found that rotating herbicide resistant canola hybrids over the years or mixing two hybrids of the same herbicide-resistant system in continuous canola did not decrease root maggot pressure, or increase yield or seed quality compared to seeding the same herbicide-resistant hybrid each year.

“For blackleg, we were probably using the same blackleg resistant genetics in all the varieties because we didn’t know what resistant genes we were using. We were ‘flying blind’ so maybe that’s why there wasn’t a reduction in blackleg disease,” Tidemann explains.

In 2014 through 2016, the canola rotation moved to a Liberty Link/Clearfield/Roundup Ready sequence. Some additional agronomic treatments were also set up to try to mitigate yield losses. Fertility treatment at 150 per cent of recommendation, higher seeding rates, tillage, and chaff removal were the additional treatments.

Tidemann says the results were variable. In 2014, no treatments increased yield. At Beaverlodge in 2015, there was a response to increased fertility and fungicide application. But averaged across all locations in 2015, none of the treatments could reduce the yield loss from continuous canola. In 2016, rotation with non-canola crops was better than any agronomic treatment.

“It is not easy to mitigate yield losses in canola. Your best bet is to rotate out of canola. Extra fertility might help but the response will depend on environmental factors. Fungicide at one location in one year helped but that was likely related to disease pressure at that site,” Tidemann says. “If you want to increase your yield in canola, rotate out for a couple years.”

Planting a blend of different hybrid seed could enhance performance.

by Bruce Barker

One part BY 6060. Two parts CS 2000. Equal pinches of Nex 1022 and BY 6074. This fancy cocktail of canola hybrids just might perform better than planting only one of the hybrids in a field. Greg Stamp of Stamp Seeds in Enchant, Alta., ran demonstration trials in 2016 and 2017 to see if a blend of hybrids would perform better.

“I talked to a few farmers who have done that with leftover seed and thought there might be potential for higher yield,” Stamp says. “It worked out in 2016 but not in 2017.”

In 2016, a blend of six different canola hybrids averaged seven per cent higher yield than the plot average and five per cent higher than the highest yielding single variety. The varieties were a mix of medium and long-term varieties, and because seed size was different, Stamp averaged the thousand kernel weights to come up with a seeding rate to target his plant population.

Some hybrids might do better under one type of climatic condition and a different hybrid might perform differently under another climatic condition. With a mixture, some of the genotypes may be able to produce a higher yield to compensate for the lower yielding ones.

In 2017, the blended hybrids averaged the same yield as the overall plot average, but less than three of the five single hybrids.

Stamp Seeds canola trials

The idea of mixing different varieties together isn’t new. Called a “composite” cultivar, it was common practice in Europe, especially Germany, and was even done in Canada. A genotype by interaction effect plays a role in potential higher yield. Some hybrids might do better under one type of climatic

ABOVE: A blend of hybrids yielded higher in 2016, but not 2017.

LEFT: A composite blend of multiple hybrids provided varying results.

condition and a different hybrid might perform differently under another climatic condition. With a mixture, some of the genotypes may be able to produce a higher yield to compensate for the lower yielding ones.

Stamp says this environmental interaction could have contributed to the differences between 2016 and 2017 outcomes. Although the trials in both years were planted under irrigation, the summer of 2017 was much hotter than 2016.

“Maybe some years a mixture could flower longer and take advantage of the longer growing season. Maybe in 2017 the mixture couldn’t take the heat blast at flowering as well as some of the individual hybrids did,” Stamp says.

The practice of registering composite cultivars is no longer acceptable in Canada. The introduction of Plant Breeders’ Rights Act meant Canadian plant breeders could no longer mix varieties together because a variety has to be clearly defined rather than a mixture of genotypes.

With a mixture of maturities, the uneven growth resulted in a few challenges. Stamp says fungicide application timing is more difficult to target. Uneven maturity also made swath timing more difficult. In 2016, the blend was also more difficult to swath, although Stamp isn’t sure why – perhaps more branching and tangling of the stems.

The trials are demonstration plots and not randomized, so drawing conclusions is difficult. However, the “composite” approach might make sense from a risk management perspective. Some hybrids do better than others in different years. Blending a few hybrids together might help compensate for years when some perform poorly and the other pick up the slack.

Alternatively, Stamp says maybe growers could look at seeding more than one hybrid on all their canola acres. For example, grow four different hybrids on four different fields. If one doesn’t perform, the others could compensate as a hedge against the weather.

“A lot depends on the environment,” Stamp says, “Whether mixing hybrids together in one field or growing different hybrids on different fields is a better way to go, it’s hard to say.”

ABOVE: Canola is known to be a very “plastic” crop, able to compensate for weather conditions ranging from hail and wind damage to moisture extremes.

Can growing season weather patterns be used to predict harvest crop quality?

by Donna Fleury

Along with good agronomic practices, weather and growing conditions impact harvest seed yield and quality of annual field crops including canola. Although predicting growing season weather remains a challenge, a team of researchers wanted to know if it might be possible to predict canola quality prior to harvest by looking at growing season weather and environmental conditions during the crop year.

Researchers at the University of Manitoba conducted at two-year project to try to answer questions around weather and canola seed quality. The overall objective of the project was to quantify the effects of growing season weather on canola quality for the purpose of predicting canola quality prior to harvest.

“We were trying to quantify the impact of the environment on different genotypes or varieties of canola, and whether or not the interaction between canola genotype and environment was significant,” explains Paul Bullock, professor and head of the department of soil science at the university. “The study included two different approaches to collecting data. In one, a few sites seeded to canola

were intensively monitored for a large range of weather factors. In the other, a large number of canola samples from the Canadian Grain Commission (CGC) harvest survey were analyzed. The samples selected were just those that provided a legal location of the field of origin so that a nearby weather station could be used as a source of weather data, as well as the planting date so that the stages of the canola phenological development at each field could be modelled.”

Graduate student Taryn Dickson led the project. She is now with the Canola Council of Canada.

For the intensively monitored sites, a large number of weather parameters were measured and data on canola development stage was collected. The parameters monitored ranged from growing degree days and calendar days to temperature, heat stress measures, evaporative demand and precipitation at various stages of development from the time of seeding until harvest. Critical canola quality parameters were measured such as oil content, protein content, chlorophyll, glucosinolates, and specific fatty acids, including oleic, linoleic and linolenic acid content.

The CGC harvest survey samples also underwent the same quality analysis. Specific canola varieties were selected to determine the effects of genotype on quality. Weather databases were used to determine growing season conditions at each sample site and to generate a similar set of weather parameters for factors such as precipitation, heat stress and water stress at different stages of canola development at each location.

“We used a partial least squares (PLS) statistical analysis approach to incorporate the large number of weather parameters collected and determine whether or not they could help us predict crop quality ahead of harvest,” Bullock explains. “[Graduate student and project lead] Taryn worked alongside the researchers at the CGC Research lab to do the canola quality work. Although the results were not quite what was expected, the outcomes can be considered good news.”

Overall, the PLS models could only predict between seven and 49 per cent of the variation in quality of canola based on the weather information. This is not a very strong correlation, and shows that the weather parameters make up only a portion of the total environmental impact on canola quality parameters. Other important factors including soil characteristics, available plant nutrients and overall farm management practices.

“The takeaway is that this is a good news story,” Bullock adds. “Although no one will argue that weather doesn’t have an impact on quality, this study emphasizes that the impact of growing season weather on canola is perhaps smaller than for other crops. Canola is known to be a very ‘plastic’ crop able to compensate for weather conditions ranging from hail and wind damage to moisture extremes and seems to be more robust. These results showed fairly muted responses in canola quality to the impact of weather.”

ABOVE:

conclusion that you can not predict crop quality based on weather parameters alone. Although weather is important, there are

Although no one will argue that weather doesn’t have an impact on quality, this study emphasizes that the impact of growing season weather on canola is perhaps smaller than for other crops.

With the completion of this project on canola, Bullock decided to conduct another wheat quality study, based on some earlier work about 10 years ago. The project will focus on how environmental conditions affect the production of wheat proteins, protein quality and gluten strength.

“[With these projects], I’ve come to the

many other factors that impact quality: soil characteristics, amount of N fertilizer used, type of seeding implement, [planting date], and other agronomic practices,” he continues. “Therefore, we have moved beyond the whole notion of predicting quality based on weather and are looking at other strategies. The systems are very complex and attempting to develop a weather-based quality model may not be the most useful approach.”

The wheat-focused study is now in its third year, and Bullock expects to be able to report on the results in another year. “We are looking at a different approach to weather

conditions by placing weather into broad categories or clusters and then trying to determine whether or not there is any broad impact on wheat quality in terms of grade, protein, and quality parameters such as gluten strength in bread dough,” Bullock says. “We are looking at weather patterns at different times of the growing season to see if we can find clusters that have a strong and consistent impact. For example, hot and dry conditions, or dry spring and wet summer conditions, and other patterns.”

For now, although growers can’t control the weather, they can focus on implementing good agronomic practices to minimize the impacts of other variables and maximize canola quality. In the future, weather may be able to be used to predict specific quality trends such as protein or gluten strength in wheat, but for crops like canola it is other factors that will play a bigger role in quality.