NEW TOOLS TO BATTLE WIREWORM

Researchers are getting better at understanding the enemy. Promising results mean there’s hope on the horizon for stronger wireworm control.

BY JULIENNE ISAACS

2018 saw fewer problems with wireworm in Atlantic Canadian potato fields than past years, according to Christine Noronha, a research scientist for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada based in Prince Edward Island. But this doesn’t mean the problem has gone away.

“Producers using rotation crops saw less [wireworm] damage this year,” Noronha says.

In general terms, researchers are cautious about predicting wireworm damage. Of all potato pests, wireworm has proven one of the most difficult to understand. New research highlights the complexity of wireworm behaviour and the attendant difficulty of controlling the pest in the field. As few chemical controls are registered in potato against wireworm, an integrated pest management (IPM) approach is essential.

IPM forms the backbone of Noronha’s program. This past summer, her team worked with P.E.I. producers on a study combining two methods of wireworm control – NELT (which stands for Noronha

The

Elaterid Light Trap) traps to control adult female click beetles, and mustard or buckwheat rotation crops to target the larvae.

“I asked the farmers to leave two 1.5-foot strips unplanted up the entire length of the field. We installed 30 NELT traps in each strip for a total of 60 traps in a 50-acre field,” she explains. All trapped female and male beetles were removed from the field once a week during May and June, which is their activity period. The field was planted with brown mustard. Next year, potatoes will be planted in the same fields, and Noronha and her team will collect samples to evaluate damage to tubers.

“We’re catching females in the traps, which prevents the laying of eggs, but by using the rotation crop we are trying to control the larvae as well,” Noronha explains. “The two methods combined may give us reduction in damage for a longer period.”

Wireworm population in the field is the biggest problem confronting researchers and producers, Noronha says.

“There seems to be little

correlation between bait trap numbers and damage,” she says. “Often, we’ll put out our baits and think, ‘we don’t have a problem,’ and then we see damage.”

Producers don’t know how many bait traps to put out, or the optimal time of year for placing them in the field, she says. “We don’t know much about the movement of wireworms in the soil, so I’m looking at horizontal and vertical movement of wireworms in the laboratory and the field.”

In a lab study looking at horizontal wireworm movement, Noronha’s team found that wireworms in the larval stage can easily move about 3.6 metres in 24 hours to reach bait traps; by 48 hours, 50 per cent of wireworms in the study had reached the bait. The team also found that when bait traps were placed at 2.4 and 2.6 metres respectively, wireworms would reach the first trap, start to feed on the bait and then move to the second bait before the food was depleted.

“Even if there’s food available, they’ll still move on. If you

Noronha Elaterid Light Trap (NELT), created by Christine Noronha, controls adult female click beetles.

remove your bait after seven days and you’ve captured seven individuals, there might have been 10, with three moving on to a different food source sometime before the bait was removed. So that means we can never be sure what the population is,” Noronha says. Her goal is to use this information to find the ideal length of time to leave bait in the ground. Another field study ran in 2017-2018 looking at horizontal movement of wireworms. Noronha’s team put tubes in the ground to a depth of 80 centimetres in October and watched the wireworms move down through the soil as it froze. In the spring, 90 per cent of the wireworms had returned to the surface to start feeding by mid-May. This means early to mid-May is a good time to put out traps for monitoring, she says.

Noronha’s team will continue to work on developing ways to better predict wireworm populations.

AAFC research biologist

Todd Kabaluk is leading the Organic Science Cluster for wireworms for the next five years.

Kabaluk’s research focus is on biological controls for wireworms. One promising method uses entomopathogenic fungi, which kills insects by infecting them through the exoskeleton, to target wireworms in the larval stage. He’s working with the private sector to develop a control product using a virulent fungal pathogen that he discovered as the active ingredient: Metarhizium brunneum strain LRC112.

Field results have shown a 75 per cent reduction in wireworm feeding damage to potatoes using granular

formulations, Kabaluk says. Kabaluk is also working on a spray formulation for click beetles, the adult stage of wireworms, which can be used in rotation years and on headlands where beetles emerge. The treatment is specific to click beetles and has so far proven to be relatively easy on beneficial insects.

He’s also developing another application technique for the biocontrol that uses an “attract and kill” method: a pheromone is deployed to attract click beetles to a biocontrol band laced with Metarhizium, which slowly kills the beetles over a period of days.

To make this system work, Kabaluk invented pheromone granules; previously, pheromones for click beetles had only been available in liquid form. He’s working with a Costa Rican company, ChemTica, to develop them.

In studies using the pheromone granules, 80 per cent of the beetles picked up a Metarhizium infection three hours after application, he says.

Pheromone granules have other potential applications; one of them is mating disruption. Kabaluk is collaborating with AAFC research scientist Wim Van Herk, who is currently investigating how the granules can be used to emit a sex pheromone to confuse male beetles and disrupt their ability to find females.

“We have pheromones that will be effective against the most pestilent invasive wireworm species on both the east and west coast – those in the genus Agriotes,” Kabaluk says.

Van Herk, who has continued Bob Vernon’s research program, says pheromones are a key aspect

of wireworm research. “Every species has its own unique pheromone. But we don’t have pheromones yet for the native species of wireworm in Canada. They’re unknown,” he says. “So that’s another project I’m working on –trying to identify, in collaboration with a pheromone chemist, what the pheromone structures are of the native species.”

Van Herk is working on another project in both British Columbia and P.E.I. using pheromones to trap adult click beetles in spring, as a monitoring technique. He’s currently developing a risk assessment guide for producers that will help them evaluate wireworm risk based on factors including the number of click beetles in traps, field history and damage to neighbouring fields.

Biological controls are emerging as a key growth market when it comes to insect pests, including wireworms. According to Kabaluk, the growth rate of biopesticides is about 15 per cent per year as large companies merge with the small- to medium-sized enterprises that have traditionally specialized in biological controls.

“There’s an acceleration in research and development for biopesticides, so I can see them becoming more mainstream pesticides in the future.”

It’s a much-needed advancement, particularly for the organic sector, for which there are currently few products registered against wireworm. Any new affordable and efficacious product for conventional producers would be welcomed, whether it is CONTINUED ON PAGE 11

PotatoesInCanada.com

FIGHTING BACTERIA WITH BACTERIA

BY CAROLYN KING

A biopesticide for managing common scab would be an exciting advance for two key reasons, explains Dr. Martin Filion with the Université de Moncton.

First of all, common scab is not effectively controlled by current methods. “For common scab, any solution would be welcome by producers. People are calling me from across the country saying they have problems with the disease,” he says. “Not many chemicals are available for common scab and those chemicals are not very effective against it. And if you want to modify your field conditions, with irrigation and so on, you might be able to reduce common scab, but you will likely have other problems eventually, such as late blight or other diseases.” Also, no potato cultivar is completely resistant to common scab, and whether or not a particular cultivar is tolerant to the disease depends on the local conditions.

“Second, many chemical

Several species of Streptomyces bacteria can cause the disease.

A naturally occurring beneficial bacterial strain shows promise as an inoculant for common scab control.

pesticides are toxic for humans and for the environment, so trying to find more environmentally friendly approaches, such as using beneficial microorganisms as biopesticides, is important. An environmentally friendly product for common scab control could be compatible with both conventional production and organic potato production, which is increasing as we speak.”

Common scab is a bacterial disease caused by several species of Streptomyces, mainly Streptomyces scabies. Filion points out that he and his research group at Moncton are among only a small handful of Canadian researchers working on common scab – even though the disease is widespread, economically important, and probably increasing.

Filion and his group have been investigating microbial possibilities for controlling

common scab for more than a decade. He collaborates on some of this work with Dr. Tanya Arseneault and Dr. Claudia Goyer, who are researchers with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Filion outlines what is involved in finding microbes to fight the disease: “Over the years, we have isolated many, many beneficial organisms from soils or root systems of plants in the Maritimes. We use a basic microbiology culture approach, growing the isolates on Petri dishes. From there, we use a DNA approach to find genes of interest in those organisms. For example, we look for genes involved in the biosynthesis of antibiotics that could be useful against plant pathogens, or for other genetic determinants that will give the organisms a competitive advantage over the pathogens.

Photos courtesy of Martin Filion.

Common scab is a widespread disease that is

We also look for certain groups of organisms that we believe are more efficient than others against plant pathogens.”

Through this work, Filion and his group have identified several promising candidates for reducing common scab symptoms. All the candidates are isolates of beneficial bacteria; most are species of Pseudomonas, but some are species of other bacteria such as Bacillus

The most promising candidate they have found so far is an isolate of Pseudomonas synxantha (formerly Pseudomonas fluorescens). This candidate, called Pseudomonas synxantha LBUM223, was isolated from a New Brunswick soil.

The researchers have been testing LBUM223 under laboratory and field conditions. Their studies show it can significantly reduce scab symptoms and may also boost tuber yields.

Filion explains that this strain’s mode of action is a little different than what is typically described in the scientific literature. “Usually beneficial organisms will either directly kill the pathogen, for example by producing antibiotics, or they will stimulate the plant’s defence mechanisms so the plant will defend itself more efficiently against the pathogen,” he says.

“LBUM223 produces an array of antibiotics including one that is called phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA), and originally we thought this PCA molecule would just kill the pathogen. However, we discovered under field conditions that the pathogen’s population remains the same but the pathogen is no longer capable of or is less efficient at creating the disease on potato tubers. LBUM223 affects the pathogen’s virulence and pathogenicity by altering the expression of cer tain genes in the pathogen.”

One of the big challenges in finding effective common scab control products – whether they are biological or chemical products – is that their efficacy can be strongly influenced by local factors like the specific potato cultivar, the soil’s physicochemical properties, the particular Streptomyces species and

strain, and the weather conditions.

The researchers are in the process of investigating this aspect for LBUM223. They have conducted field studies to evaluate the strain at two sites, one in New Brunswick and one in Prince Edward Island, to see how the strain performs under different soil and weather conditions and in two different potato cultivars.

So far, the results are very encouraging. “From what we have seen, we think LBUM223 could be efficient under different cultivars, and it could be very efficient under different environmental conditions,” Filion says.

Not many chemicals are available for common scab and those chemicals are not very effective against it.

As the researchers move the biopesticide towards commercialization, they will be conducting larger scale tests to determine its efficacy range. “For instance, we know that some cultivars are already more resistant to common scab than others, but the plant genetics behind this resistance are not well known at present. So we will need to see if our biopesticide is effective for all commercial cultivars,” he says.

“Regarding the pathogen’s strains, we published a paper a couple of years ago showing different strains in the Maritimes. And now we have a Canada-wide study where we are characterizing the genetic diversity of the pathogen across the country, so we will learn more about it. We are looking at testing our biopesticide against those different genetic strains of the pathogen.”

The researchers have already developed molecular markers for LBUM223 that will allow them to track the biopesticide’s persistence

under field conditions. “We can extract DNA from the soil and, by using these markers, we will know exactly how many bacteria of LBUM223 are in the field after the growing season or before the next growing season.” That type of information will be helpful in meeting the regulator y requirements for the product’s commercialization.

Filion suspects that LBUM223 might be able to persist in a field for a while after harvest of a treated potato crop since Pseudomonas synxantha occurs naturally in New Brunswick and LBUM223 was isolated from a sandy loam soil that is common in Eastern Canada. If the strain is able to persist for a period of time, that could be an advantage for the next potato crop. The researchers are not expecting any environmental problems from the strain since beneficial Pseudomonas bacteria are commonly found in soils across Canada and around the world.

Filion and his group are working on a way to apply the biopesticide as a potato seed treatment. They have experimented with several formulations and have come up with a peat-based substrate that works well. The bacteria are able to stay alive and active on this substrate for at least a full year at room temperature, so retailers and growers will not have to worry about refrigerating the inoculant.

The researchers already have enough scientific data about the biopesticide’s effectiveness and safety to apply for registration of the strain, an important step toward commercialization. Filion estimates that registration and scaling-up for commercial production will take between three and five years, and he is hopeful a commercial product could be on store shelves in a few years. Filion is currently looking for the right commercial partner to bring the product to market.

This biopesticide research has received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation, and Genome Canada, and many potato growers and potato production and processing companies are collaborating on the research.

ON THE WATCH FOR ZEBRA CHIP

An

update on this potential disease threat, the insect that transmits it, and the natural enemies that prey on the insect.

BY CAROLYN KING

Zebra chip is a serious disease that can kill potato plants, significantly reduce yields, and make infected tubers unmarketable. It was first documented in Mexico in 1994 and in Texas in 2000. Since then, it has spread northward through much of the Western United States, as well as to Central America and New Zealand. Serious losses from zebra chip in the U.S. Pacific Northwest in 2011 sparked increasing concerns in Canada.

In 2013, a five-year Canadian effort was launched to monitor for the disease and the potato psyllid, the insect that transmits the pathogen. Fortunately, only very small numbers of potato psyllids have been found, and of those psyllids, only a tiny percentage actually carried the

pathogen. The disease has not yet been found in Canadian potato crops.

However, the potential threat of zebra chip remains. Monitoring is continuing in Alberta, where most of the psyllids were found, to ensure that growers will be ready if potato psyllid populations increase and the disease emerges. Plus, the monitoring effort is providing helpful information on the rest of the insect community in the province’s potato fields.

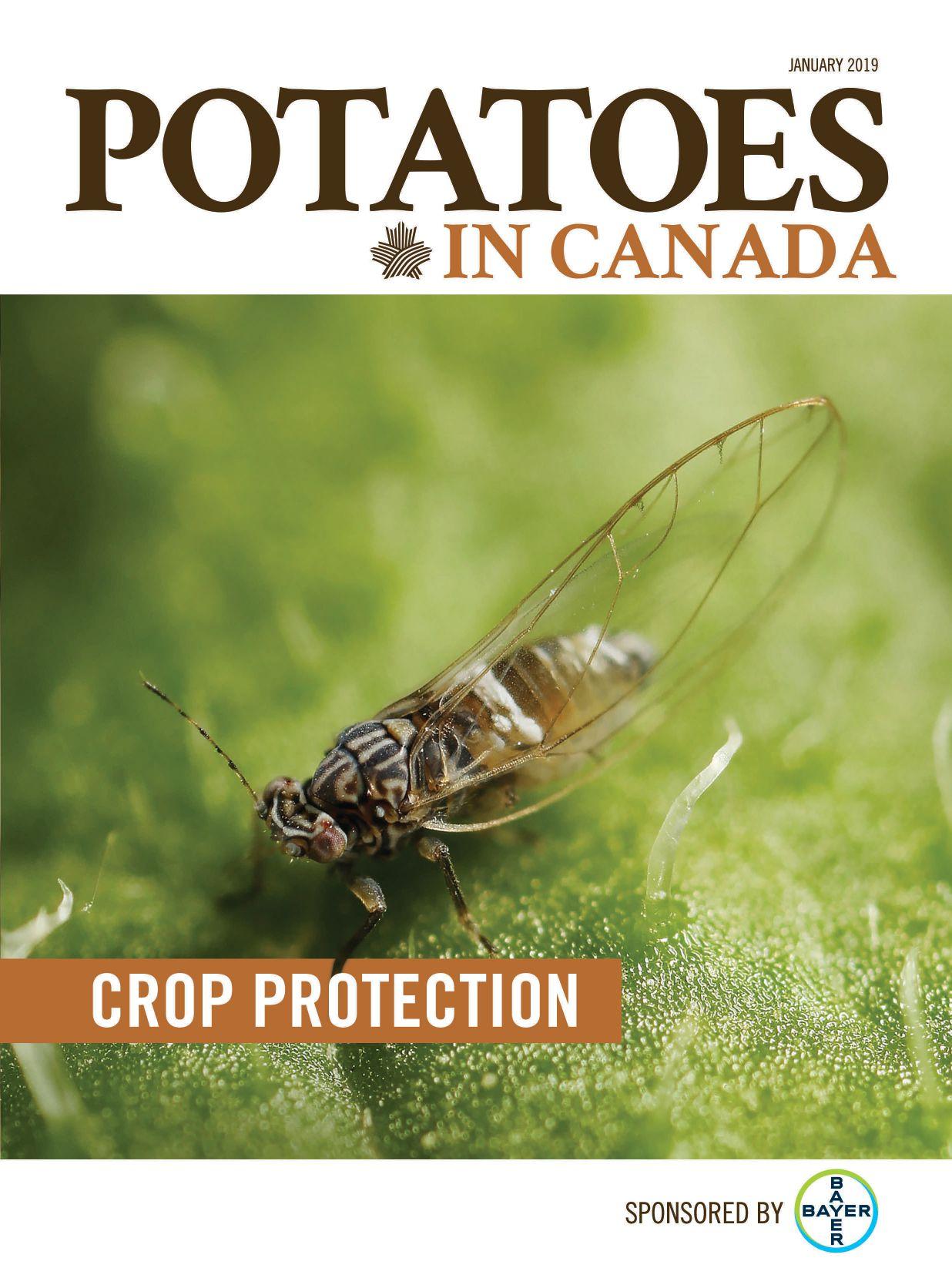

“Zebra chip is caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum (Lso). Its vector, the potato psyllid (Bactericera cockerelli), is a small flying insect about two to three millimetres in length. This phloem-feeding insect prefers to

lay its eggs on potato plants and other plants in the same family like tomatoes, peppers and nightshade weeds,” explains Dan Johnson of the University of Lethbridge, who led the national monitoring program from 2013 to 2018.

The psyllids acquire the Lso bacterium by feeding on infected potato plants, and they spread it to other plants when they feed on them. Infected adults can also pass Lso to their offspring.

Infected potato plants have such symptoms as stunting, and misshapen and discoloured leaves. They look similar to plants with diseases like psyllid yellows, which is also caused by the potato psyllid, and purple top.

Zebra chip was first documented in Mexico in 1994 and Texas in 2000. Now, it can be found through much of the Western United States.

Photos courtesy Of Dan Johnson.

Potato psyllids are able to transmit the bacterium that causes zebra chip disease.

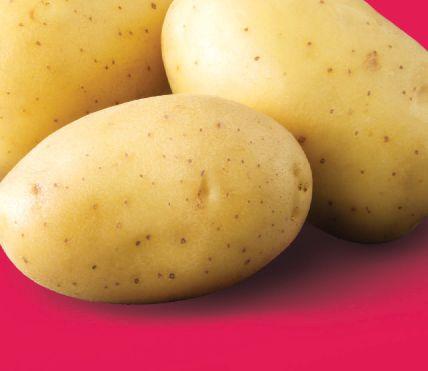

Tuber symptoms of Lso include brown streaks and flecks. Infected tubers are safe to eat, but the disease causes a higher accumulation of sugars, which alters tuber flavour and colour. In particular, the streaks and flecks in the raw tubers turn into dark blotches or stripes when the potatoes are fried.

HIGHLIGHTS FROM 2013 TO 2017

The national program involved Canada-wide sample collection. In addition to Johnson, the primary applicants and research team included Larry Kawchuk with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) and Scott Meers with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. They and research staff collaborated with people across the country to carry out the sampling. The program was funded under Growing Forward 2, with support from AAFC, Canadian Horticultural Council, Potato Growers of Alberta (PGA), Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, and the University of Lethbridge. In addition, the PGA worked with Promax Agronomy Services to conduct extra monitoring in Alberta and provide weekly reports to growers.

Participants in the national and Alberta efforts used sticky cards, replaced on a weekly basis, to capture adult potato psyllids and other insects in potato fields. The national program also did some monitoring in roadsides, greenhouses and other areas, and supplemented the card sampling with leaf examination, sweep sampling and vacuum sampling to look at other stages in the psyllid’s lifecycle.

In the national program, Johnson’s group at the University identified the insects on the cards, including potato psyllids, other psyllids, other pest insects, and natural enemies of the psyllids. The various psyllid species look quite similar to

each other, so a microscope is needed to identify the potato psyllid. Kawchuk’s group tested the psyllids and plant samples for Lso using DNA. They also used DNA to identify the haplotypes (distinct genetic types) of the potato psyllids and the pathogen.

In 2013, sampling in the national program took place at locations across southern Alberta. No potato psyllids were found. In 2014, the monitoring expanded to more Alberta locations as well as locations in Manitoba, Quebec, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Again, no potato psyllids were found.

From 2015 to 2017, most provinces had at least some sampling sites. Alberta and New Brunswick usually had the most sites, with about 500 cards per year from New Brunswick and about 1,000 or more from Alberta.

No potato psyllids were found east of Manitoba. A few were found in Manitoba and Saskatchewan but only in 2016. In Alber ta, small but increasing numbers of potato psyllids were collected from 2015 to 2017. Then late in 2017, a few Lso-infected psyllids, or “hot” psyllids, were collected at several Alberta sites. Lso was not found in any plant tissue from any province during the monitoring program.

“We looked at roughly three million insects on almost 8,000 cards in order to find the few hundred potato psyllids that we collected in potato fields,” says Johnson. “In the U.S. and other affected regions, zebra chip does not normally become a problem unless the potato psyllid numbers are much higher than we found.”

The findings from the PGA’s monitoring effort were similar to the national program’s results for Alberta. “We saw very low numbers of potato psyllids. For example, in 2017 with our 70

monitoring locations, we found just over 190 potato psyllids in total in southern Alberta [over the course of the growing season],” explains Thomas McDade, PGA agricultural director. “When I talk to some of my counterparts in Idaho for example, in some cases they were finding about 80 to 100 potato psyllids on one card overnight. In that case, they were spraying to control the psyllid. We were finding just two or three psyllids per week.”

McDade also notes, “We did not find any hot psyllids until right at the end of the 2017 growing season, when we found four over a two-week period. So the numbers were very, very small. We looked really closely at the production area where the hot psyllids were found and didn’t find any evidence of zebra chip disease.”

Johnson’s group at the university also conducted some related research studies, including an evaluation of the potential for beneficial insects to control the psyllid. “Our field study showed that the communities of natural predators in potato fields were at levels that could significantly reduce potato psyllid numbers,” says Johnson. “In our lab experiments, we found that some predators like ladybird beetles (also called ladybugs) can rapidly consume hundreds of psyllids per day.”

Over the course of the five-year program, Johnson shared updates with the other network participants, growers and others who might be interested in the work. As well, he and Kawchuk have made many presentations at potato grower meetings and scientific conferences.

ALBERTA FINDINGS IN 2018

Although the national program ended in March 2018, the PGA has launched a new five-year insect monitoring program in

“In our lab experiments, we found that some predators like ladybird beetles (also called ladybugs) can rapidly consume hundreds of psyllids per day.”

Alberta. This new program is a partnership between the PGA, Cavendish Farms, McCain, Lamb Weston, Old Dutch, Frito Lay, Promax Agronomy and Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

The new program identifies all the insects on the sticky cards, and provides weekly updates to growers on potato pests, like potato psyllids and flea beetles, and beneficial insects. Any potato psyllids found on the cards are tested for Lso.

“With this monitoring network, we are able to give our growers, and all of the agronomists and processing partners that work with our growers, very good information about what is in their fields. It allows them to identify an affected area really quickly and make very good, timely decisions on whether or not to do some targeted, localized spraying,” McDade explains.

“If you just spray everything, you could make your problems worse ultimately because you’ll also kill the beneficial bugs that feed on some of these pests. For instance, when psyllids first hatch, ladybugs will feed aggressively on them, eating as many as they can possibly find.”

He adds, “We want to know immediately if there is ever a flare-up of potato psyllids. We haven’t had to spray for them and hopefully that holds, but the only way to know is to monitor. If you wait until the potatoes are processed to find out if the disease is present, then that is much too late.”

In 2018, the PGA’s program had 70 monitoring sites, located throughout

the processed acres in southern Alberta and in the key seed growing regions near Lacombe and Edmonton.

“This year, we didn’t find any potato psyllids at all and very few flea beetles,” McDade notes. “Very little to no insecticide was sprayed on our potato fields because we knew it wasn’t necessary.”

In 2018, Johnson did some limited monitoring in Alberta just out of interest, regularly sampling only eight sites. Also, some monitoring was done in Manitoba and British Columbia. Although the insect identification is not quite finished, so far they have found almost no potato psyllids.

Comparing notes with his U.S. colleagues, Johnson learned that potato psyllid numbers had also really decreased in Idaho, Washington and Oregon in 2018.

At present, the reason for the population decline is unknown.

Johnson says, “A lot of factors could influence it – a weather effect, something about the insect or its internal microbial environment, a population cycle of some kind.”

He suspects the weather played an important part in the very low psyllid numbers in Alberta. “We had such a cold start to spring that anything cold-blooded that overwinters and has to get going in the spr ing had a hard time. The degree-day accumulation in April was lower than any other year in the past decade. Then, after it finally warmed up, the temperatures slammed back down again. I have a feeling those conditions might have hammered a lot of insects.”

CONSIDERING THE LONG-TERM OUTLOOK

Although there are still many unknowns, the work so far is providing food for thought about the outlook for potato psyllid populations and zebra chip in Canada.

For instance, Johnson is pretty certain that some potato psyllids are overwintering in southern Alberta. He bases his opinion on several indicators. One is that the adult potato psyllids collected on the sticky cards did not appear to have undergone long-distance flights. “If you look at them under a microscope, you can see that all the little hairs and all the parts of the wings don’t show a lot of wear. In other words, they look like they recently transitioned from a non-flying nymph to a winged adult.”

Another indication of overwintering is that the psyllids tend to be found in the same areas from one year to the next. If the adults were dying off each fall and being replaced by a new batch of adults falling out of the jet stream the next year, then there would likely be a more varied distribution.

For now, Johnson’s best guess is that potato psyllids and zebra chip will not be a serious problem under the current climate and natural enemy conditions in Prairie potato fields.

“When I sample potato fields, I am very impressed with the range and diversity of the natural enemy community. The community is pretty healthy because growers really haven’t been spraying much insecticide. So potato psyllids have a lot of predators waiting and continually searching for them, and that is a good thing. I would not

Left: A microscope is needed to accurately identify potato psyllids. Centre: Potato psyllid nymphs are pale green and flat. Right: The five-year monitoring program examined several million insects on thousands of sticky cards and found a few hundred potato psyllids.

want to see a lot of insecticide spraying,” he says.

“Also, I think we’re on the edge of the optimal climate range for potato psyllids, and that every few years, the weather probably knocks their populations back quite a bit. So I think they will remain as a resident population and will pop up in noticeable numbers around the Prairies. A certain proportion of those will carry the zebra chip bacterium. My gut feeling is that we probably won’t see huge outbreaks like the ones that have occurred in some years in the U.S. and elsewhere.”

However, he cautions, “With a changing climate, outbreaks might happen.” Qing (Summer) Xia, in her 2017 University of Lethbridge master’s thesis, compared weather and climate data with scientific records of potato psyllids and psyllid yellows in North America as far back as the early 1900s. Those records include some Canadian observations; most of those were southern Alberta observations occurring from 1928 to 194 4. Xia’s findings confirm that warm temperatures coupled with moderate precipitation favour higher potato psyllid populations. Her results from using various climate models suggest that ongoing climate warming would increase the psyllid’s range in Canada, particularly in parts of Western Canada.

Ongoing research and monitoring would help to get a firmer handle on the potential risk level for potato psyllid and zebra chip problems in Western Canada. Johnson says, “I think continued monitoring with a scientific approach and some transparency of sharing the results with growers and researchers could achieve a lot with very little resources.”

IF THE PSYLLIDS DO BECOME A PROBLEM…

In places like Texas, where zebra chip is an ongoing major problem, the main way to fight the disease is by insecticide applications to control potato psyllids. Because

potato psyllid control has not been needed in Canada, only a few products are currently registered for it in this country.

One example is Movento, a Group 23 systemic insecticide that moves in the plant’s xylem and phloem. “The psyllids feed right in the phloem, and few insecticides move through the phloem. Movento’s activity is largely through ingestion. It works primarily on the potato psyllid nymphs but it also has activity on the adult females indirectly by causing them to lay less viable eggs,” says Andrew Dornan with Bayer Crop Science Inc. Canada. He explains that, like a lot of new insecticide products, Movento has a narrow spectrum of activity, which is a good thing. For example, it has little activity on some natural enemies of potato psyllids such as ladybird beetles, parasitic wasps, lacewing larvae and predatory bugs like pirate bugs.

Like McDade and Johnson, Dornan stresses that potato psyllids are not a problem in Canada at present, and insecticides should only be used if the psyllids really become a problem.

McDade emphasizes, “Running a good monitoring program is far cheaper than widespread insecticide applications. The cost of our sur veillance program averaged out to about 65 cents an acre. This program allows us to take a very targeted and scientific approach to insect management. Knowing what the total insect population is out there and knowing if it can maintain itself at a healthy, balanced level, allows far better decisions on spraying.

“We are also very aware of the importance of only using chemicals such as insecticides and fungicides strategically to reduce the risk of creating resistance to these chemicals. Particularly now with the increased regulatory pressures regarding a lot of chemicals, taking this surveillance approach shows we are sustainable and continuing to grow as healthy and as high quality products as we can.”

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 4

biological or chemical, according to Kabaluk.

Van Herk’s team is conducting an efficacy study across Canada, testing different compounds for use against wireworm in potato. His team has also done studies in wheat, which can be used to help control wireworm in potato in two different ways.

“You can use wheat treated with insecticide either as a rotation crop – if you can eliminate your wireworms in cereals then the following year you have a clean field as far as wireworms go – or you can use treated wheat as an in-furrow application in between your tubers.”

Using the latter method, Van Herk’s team found damage control between 70 and 80 per cent when the broad-use insecticide Fipronil was used on wheat planted in potato rows. Fipronil is not registered in Canada, but the team is attempting to find another insecticide that is equal in efficacy.

In terms of insecticide options, producers can use Thimet 20G, an organophosphate systemic insecticide, against wireworm in potato. The product is restricted, so producers who want to use it have to complete a certification and licensing requirement.

According to Andrew Dornan, a senior field development representative for Bayer CropScience Inc., the company currently has one product registered for wireworm in potato – Titan, a second-generation neonicotinoid insecticide. “What we’ve found, particularly in P.E.I., which is really struggling with a species that’s hard to control, is that if we do combinations of Titan as a seed treatment and bifenthrin (Capture insecticide) as an in-furrow, they’re getting control of wireworm that is equal to use of Thimet,” Dornan says. However, Capture has been scheduled for a three-year phase-out ending in 2021.

BASF has also launched a new Group 30 insecticide, Broflanilide, and anticipates registrations in Canada and the United States. The insecticide has seen good performance as a cereal seed treatment for wireworm control.

“Wireworm needs a lot of research attention right now,” Kabaluk says. Producers may have to wait several years for research to translate into products that work in the field against this difficult pest – but promising results on many fronts mean there is hope on the horizon.

DISEASE & INSECT PROTECTION YOU CAN COUNT ON

We’ll let our product do the talking. Titan® Emesto® is the number one potato seed-piece treatment used by Canadian potato growers. The unique red formulation is easy to apply and see. It protects against the broadest spectrum of insects plus all major seed-borne diseases, including rhizoctonia and silver scurf. It also provides two modes of action against fusarium, even current resistant strains. It takes a lot of confidence to grow a healthy potato crop season after season and we’re proud Canadian potato growers keep choosing Titan Emesto to do it.

Learn more at TitanEmesto.ca