• Leading FCR

• Impressive Daily

• Strong Livability

• Highest Yield

• Excellent Breeder

Performance

• Exceptional Livability

by Brett Ruffell

The number of COVID-19 cases has started to rise again in some provinces. In fact, cars have been lined up around the block at my local testing centre in recent days due to an outbreak in our nightlife scene.

Many experts expect this trend to accelerate with kids back at school. Add to that the fact the flu season has started and many in the healthcare realm fear our hospitals will again become overtaxed.

With the country seemingly at another important crossroad in the pandemic, it felt like a good time for an industry check up. For that I spoke with leaders from each poultry sector about their response.

In terms of broilers, Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) scaled back production to adjust the supply to match the changes in demand brought on by COVID-19.

Foodservice companies, which represent 40 per cent of Canadian chicken production, were hit hard by stay-athome orders. While there was a pivot to retail, it wasn’t enough to make up the gap.

Thus, CFC’s board voted to adjust the previously decided allocation for the May-June and July-August periods by 13 per cent and 12 per cent respectively. However, it only adjusted the September-October period by two per cent.

“In doing so, CFC believes

it is in a better position to meet demands without the need to depopulate flocks on farm, which has been done in other countries,” says Lisa Bishop-Spencer, CFC’s director of brand and communication, in explaining the reductions.

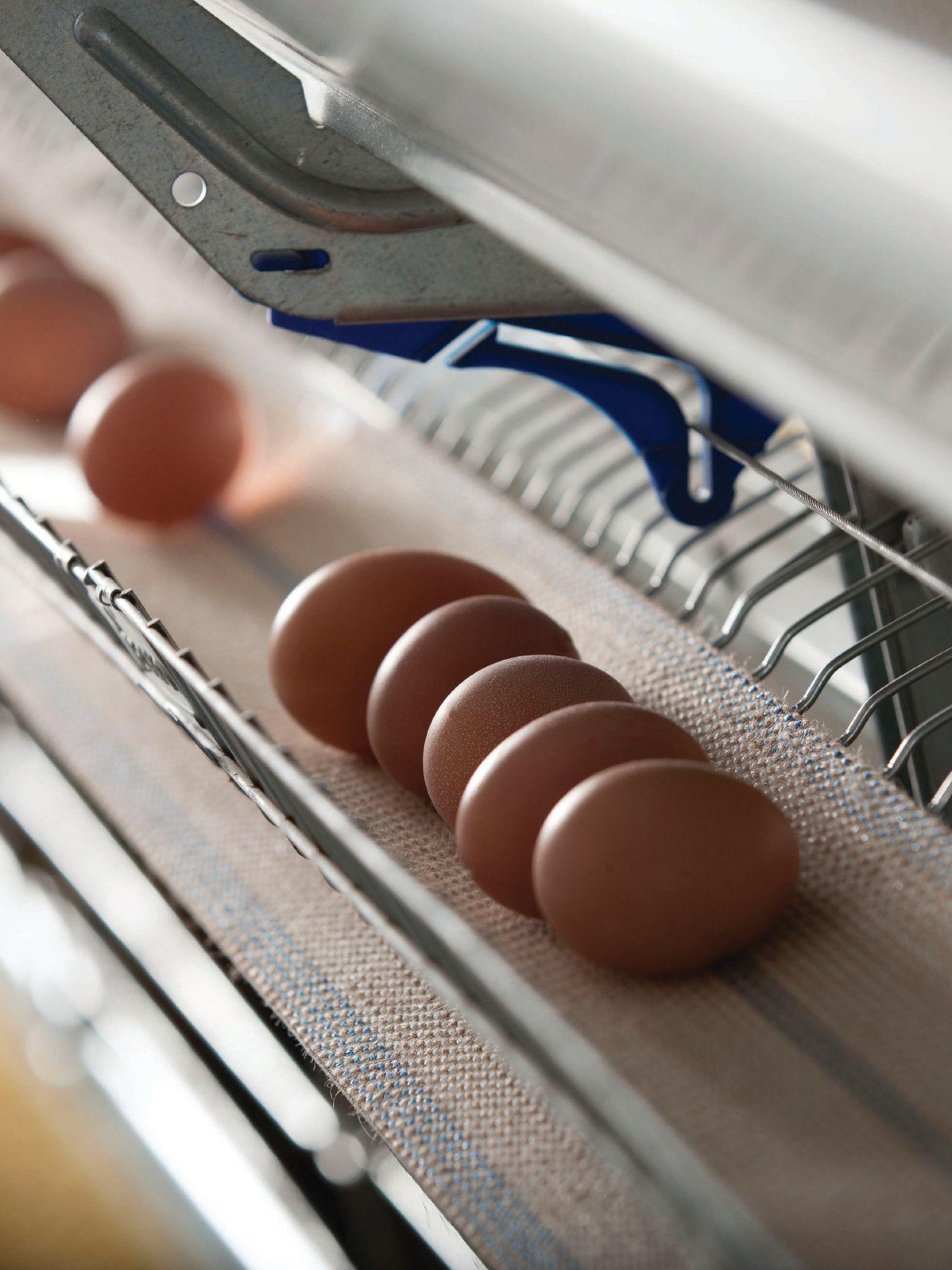

T hese adjustments had a profound impact on another sector. “A lot of those hatching eggs had already been produced,” says Drew Black, executive director of Canadian Hatching Egg Producers. “So, because we’re always months ahead of when the chicken quota is being set, it had a pretty dramatic impact when the demand was reduced.”

“It had a pretty dramatic impact when the demand was reduced.”

Hatching egg producers responded in a few ways. Some chose to delay the placement of new flocks. Others chose to take out existing flocks earlier. In fact, Black says most provinces took out some flocks at around the 56-week mark. “At that point producers aren’t really making any money,” Black says, noting that some provincial boards then compensated farmers to get them back up to breaking even.

Moving forward, CHEP has updated its plans to match

CFC’s adjusted forecast.

L ike the chicken sector, Canada’s egg producers were impacted by reduced demand from foodservice companies. They were, as a result, left with a surplus of eggs.

The sector implemented a number of measures in response. For one, it increased egg donations to longstanding partners like community food banks. In fact, EFC, egg boards and graders have donated millions of eggs to food banks. It also activated programs to reduce the size of Canada’s national flock by removing hens nearing the end of their production cycle.

L ooking ahead, EFC estimates a 13.5 per cent decline in demand for eggs in the egg processing sector for the entire 2020 year. “It will take many months for egg processors to resume their normal capacity,” EFC chair Roger Pelissero says. Despite that, the organization has no plans to adjust quota allocation in response to the pandemic.

L astly, Turkey Farmers of Canada reduced its allocation by seven per cent for its market year. It was hit not only by the reduced demand from foodservice companies but more specifically by the fact that some grocery stores had closed their full-service deli departments, which had been a promising growth area for the turkey sector.

Even now, “Service delis aren’t moving product like they use it,” says Phil Boyd, TFC’s executive director, adding that “deli counter sales are a big part of the turkey market, for sure.”

canadianpoultrymag.com

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Associate Publisher Catherine McDonald cmcdonald@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-921-6520

Account Coordinator

Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer Curtis Martin

Circulation Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5183

VP Production/Group Publisher Diane Kleer dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Circulation email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes) USA – 1 Year $91.50 CDN Foreign – 1 Year $103.50 CDN GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2020 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

When you choose to install the LUBING 4023 Maximum Flow, All-Stainless Nipple with 360 degree action, you choose a real winner! It is constructed 100% from high grade, precision machined, stainless steel and is virtually indestructible.

This nipple is designed to be used with our one-arm LitterGard cup and has a wide range of flow that can be adjusted down for small 4 lbs. birds or adjusted up to over 100 ml for large 9.5 lbs. birds. You can decide the flow you want! Combine this nipple with our 28 mm (1.10-in) drinker pipe, the largest on the market, and you have the water volume you need 24/7.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Join the club of thousands of growers that have enjoyed the longevity and performance of this nipple/cup combination that has been proven time and time again for well over 20 years.

Got Lubing? You can’t afford not to!

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263.6222

Fax: (450) 263.9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963.4795

Fax: (780) 963.5034

An outbreak at a Calgary chicken processing plant in late August has led to several workers testing positive for COVID-19. The company initially learned of three positive cases but that number quickly grew. The latest reported figure was 19 cases. Despite the outbreak and calls from the workers’ union to temporarily shut down, the company was still vowing to stay open at the time of going to print.

Employees of a Fraser Valley chicken catching company in the middle of a BC Supreme Court animal abuse case are again alleged to have been caught on undercover video harming animals. In video alleged to have been taken on July 15, 2020 at an Abbotsford egg farm on Hungtingdon Road, employees are seen loading chickens into crates in ways described by a witness as “disturbing” and showing “sever animal cruelty.”

The federal government has started providing cash for food processors across the country to help them deal with COVID-19. A $77.5-million emergency fund was announced by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in May to help food processors adapt to COVID-19 protocols, including acquiring more protective equipment for workers. It was also supposed to help upgrade and reopen meat facilities shuttered due to outbreaks of the novel coronavirus. So far, the feds have approved 32 projects.

B.C.’s Stewart Paulson, who passed away peacefully at home in August, devoted his life to serving the poultry industry.

One of Paulson’s proudest achievements was establishing the UBC Specialty Birds Research Fund with funding support from the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture.

Stewart Paulson passed away peacefully at home in August at the age of 75. Stewart obtained his BSc and MSc (1970) from the University of B.C.’s Department of Poultry Science under the supervision of the late Bob Roberts, and continued his graduate education at UC Davis.

Upon his return to Canada, he joined the poultry department of Agriculture Canada in Ottawa. Subsequently, he was an industrial market researcher for Cominco in Vancouver, and for five years, had his own consulting company.

He then worked as the Poultry Industry Specialist for the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture (BCMAF). In this position, he became an effective liaison between the provincial government, UBC, and the B.C. poultry industry.

He spearheaded the formation of the B.C. Sustainable Poultry Farming Group and later, to counter the avian influenza

epidemic, designed a biosecurity and insurance policy for the industry to implement.

Among his proud achievements, he established the UBC Specialty Birds Research Fund with funding support from BCMAF. Stewart devoted his life to serving the poultry industry in B.C.

In addition to his devotion to the poultry industry, Stewart was an ardent chess competitor and enthusiastic supporter of his wife and daughters in their sports, arts, and career endeavours.

In memory of Stewart’s life and contributions to the poultry industry and sustainable production, family, and friends are now looking to establish the Stewart Paulson Memorial Scholarship Fund at the UBC Faculty of Land and Food Systems.

The fund will support graduate students whose theses focus on sustainable poultry or animal production and marketing.

Daniel Venne has been honoured with the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association’s (CVMA) Industry Award for his contributions to the improvement of poultry health, welfare and production.

“Dr. Venne devotes his energy to preventative poultry medicine,” says Stewart Ritchie, president of Canadian Poultry Consultants Ltd. “It is important to recognize persons with Dr. Venne’s skill set and energy because it is rare to find someone who so generously shares their knowledge and time, and so willingly participates in continuing education locally and abroad.”

Venne worked summer jobs in many poultry production areas, from washing barns to slaughter plant work, before becoming a veterinary student. He received his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine in 1990 and a Master of Science in Pathology and Microbiology in 1993 from the University of Montreal.

He is licenced to practice in Quebec and New Brunswick, is a Diplomate of the American College of Poultry Veterinarians and is actively involved in several veterinary organizations.

That includes years on the executive board of l’Association des vétérinaires en industrie animale du

Québec, as a member of the professional inspection and drug committees of the L’Ordre des médecins vétérinaires du Québec, and he is currently serving as co-director of the Canadian Association of Poultry Veterinarians.

Venne was also the veterinary services director for Scott Hatchery in Quebec, the science vice-president for Selected Bioproducts and a veterinarian for Shur-Gain Inc.

“I heard Dr. Venne use his engaging personality to present original field-oriented research and discuss poultry health issues for years at the annual American Association of Avian Pathologists meetings,” explains Bruce Stewart-Brown, senior vice-president of live production and technology innovation at Perdue Farms, Inc.

“His knowledge of poultry medicine, nutrition and production is impressive, and his understanding of avian physiology and pathology is remarkable. Dr. Venne is a pioneer in avian clinical pathology and significantly impacted our field by providing us additional tools to improve poultry health, welfare and productivity, while helping us reduce antibiotic use.”

Daniel Venne won the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association’s Industry Award for his contributions to the improvement of poultry health, welfare and production.

SEPTEMBER

SEPT. 20

PIC’s Science in the Pub, Webinar poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCTOBER

OCT. 7

PISW, Virtual Event poultryworkshop.com

OCT. 15

PIC’s Poultry Health Day, Webinar poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCT. 22

PIC’s Annual General Meeting poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCT. 20-22

Virtual Poultry Tech Summit, Online

wattglobalmedia.com/poultry techsummit

NOVEMBER

NOV. 12

Eastern Ontario Poultry Conference, Webinar poultryindustrycouncil.ca

NOV. 30

100 is the number of presentations Venne has made across Canada over 29 years.

PIC’s Science in the Pub, Webinar poultryindustrycouncil.ca

JANUARY

JAN. 25

PIC’s Science in the Pub, Webinar poultryindustrycouncil.ca

By Lilian Schaer, Livestock Research Innovation Corporation

Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC) fosters research collaboration and drives innovation in the livestock and poultry industry. Visit www.livestockresearch.ca or follow @LivestockInnov on Twitter.

Research and innovation have been essential in helping farmers produce more food and do so faster and more economically. But the power of innovation is also being put to use to address issues of a greater good, like animal welfare, labour and environment. There are many examples in the poultry sector of solutions that do just that.

According to Livestock Research Innovation Corporation CEO Mike McMorris, a large part of the organization’s mandate is to support innovation at all stages of the livestock value chain.

That includes fundamental research, often an essential building block in the development of new technologies. It also comprises the network and relationship building that is key to helping innovators market their solutions.

Poultry has struggled with how to handle the male chicks resulting from breeding for laying hens. They don’t grow as quickly as broilers or have tender meat. Thus, they aren’t moved into meat production.

A Canadian innovation called Hypereye, which has received considerable financial support from Egg Farmers of Ontario and government programs, could be the answer. It’s a light-based technology developed at McGill University that can separate male eggs from female ones the day they are laid. This ensures that only female eggs are incubated and hatched. It is now in the commercialization stage.

Ontario-based start-up Transport Genie is trialing its real time data capturing system with one of Switzerland’s largest integrated poultry com -

panies, Prodavi SA. Using sensors, the system monitors microclimate conditions inside poultry and livestock trailers and shares that information with the supply chain to help maintain welfare during transport. Prodavi transports over 1.5 million day-old layer chicks to Swiss poultry farms annually, as well as more than 15 million hatching eggs.

Research at the University of Guelph into how different light sources affect poultry brains led to the development of AgriLux, LED spectrum lighting specifically for poultry. In addition to increasing egg laying by up to five eggs per hen per year, it has been proven to reduce birds’ stress levels, resulting in lower mortality and increased growth.

Combustion technology

Irish agri-tech company BHSL

has developed a patented onfarm system called Fluidised Bed Combustion that converts chicken manure into energy for heating and electricity generation for farm needs. It’s low in emissions and produces a fertilizer high in potassium and phosphorus as a by-product.

Danish climate system company SKOV has a ventilation system that can be customized to both a farmer’s barn and their local climate region. This ensures optimal air quality within the barn all the time.

And Dutch ventilation supplier Scan-Air makes windows and doors specifically for livestock use instead of simply installing “regular” windows into barns. The Scan-Air windows each have their own dark-out features that makes it possible to regulate interior light directly through the windows.

Up and coming too are robots that can do anything from keeping birds moving around in barns for added health benefits to egg collection and cleaning and disinfection. Work is also underway to automate various stages of poultry processing using artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things makes it possible to constantly gather data and monitor almost every aspect of a bird’s life.

“Innovation has been key to the growth and success of Canada’s poultry sector, and it remains vital to helping the poultry value chain address ongoing challenges and emerging issues,” McMorris adds.

As head of one of Canada’s largest egg industry players, Burnbrae Farms’ president Margaret Hudson has quite the task on her hands leading the company through a pandemic. The business has egg grading, breaking and farming operations in five provinces across the country. And Hudson oversees Burnbrae’s strategy development and operations. Canadian Poultry spoke to her about coordinating the egg giant’s response to the virus.

What safety measures did you roll out?

We implemented a whole bunch of new safety protocols. People are wearing masks. We’re packing eggs, so most of us have to come to work. And sometimes it’s impossible to remain socially distanced. So, we put plexiglas between lines. And, obviously, we screen employees before they enter the facility.

We also enhanced our cleaning regimens, invested in PPE (personal protective equipment) and sterilized our baskets, because our industry uses a lot of returnable containers and carts. Even on the floor, we’ve worked very hard to create small cohorts.

So, people are coming into very limited contact with a limited number of people.

What if an employee tests positive?

Another measure that we’ve had to follow is if someone has symptoms or has come in contact with someone who’s been COVID positive, we’ve had to do contact tracing and isolation. We followed all of the public health guidelines around that. We’ve had a few instances where we’ve had to have employees self-isolate. But through contact tracing, we managed to limit the risk to our employee base and keep everyone safe.

Up until a couple of weeks ago, we would have a call every day and we might have two or three employees at two or three locations isolating waiting for test results. And then they’re negative. We had one instance where we had three employees isolating and they all came back positive. But they came through that without any major issues and they’re back at work after eventually testing negative.

So, distancing and segmenting employees makes contact tracing easier? Yes, because if you had someone with

symptoms and you weren’t segregating people you’d have to isolate the whole plant while you waited. I think it’s been part of our success. We’ve managed to have very minimal impact operationally, and on the health and safety of our employees.

How has the testing process evolved? Early on, it was tough because testing was difficult. You couldn’t just send employees for a test because you couldn’t get one. It was reserved for healthcare workers. And so, people had to go home for a couple of weeks and see if additional symptoms

materialized. More recently, it’s a lot easier to get testing and to get results back rather quickly.

Any issues securing PPE early on?

Honestly, we had a beautiful group of volunteers that made masks. We had one of our health and safety people initiate it by making masks. And then once people realized we needed masks, I had family members making them who knew how to sew. Longer term, we deal with TNT, which is an Asian supermarket chain. And they reached out to us and said if you need PPE, we’re here to help. And we’ve actually been sourcing some of our supplies through them.

How have changes in consumer behaviour affected Burnbrae?

People were panic buying and pantry loading. And, what we saw was a massive increase in retail. And then at the very beginning of the crisis there was a temporary egg shortage and you saw empty shelves. That was because people who normally kept two dozen in their fridge suddenly had five to 10 dozen.

Also, what’s happened is carton suppliers couldn’t keep up with demand for consumer formats like cartons. So, we had to pivot very rapidly. Foodservice is trays and boxes and retail is cartons and wire baskets and carts. As a result, you’ll notice a lot more 30 trays of eggs. And that’s because there’s not enough cartons in North America to serve the rise of retail.

As a large company, what was the process like coordinating everything?

I’m so proud of our team. People worked very quickly to pull together a pandemic preparedness plan and to address the needs of not just our employees, but our operations and supply chain as well. I think the most important thing, when you’re bigger, is communication.

We really increased our messaging throughout the crisis to all of our stakeholders. We’ve had daily leadership meetings at the top of the organization as well as with all our plant leads and one or two levels down.

What charitable work has Burnbrae done since the pandemic started?

We’ve donated over 3.6 million eggs to over 30 food bank and charities coast to coast in over 3,000 communities. We just really wanted to help. We also had some

issues where some product was approaching its sale date. So, we quickly pushed that out into food banks. We also wanted to support our healthcare workers. So, we donated $55,000 to 11 hospitals to help with the purchase of PPE.

SYSTEMS OPERATE AT DIFFERENT HEIGHTS TO PROMOTE EFFICIENT NO-SPILL DRINKING

HEADS UP DRINKING™ takes into account what broiler breeders have to do in order to drink - namely, lift their heads and let gravity do its work.

By incorporating gender specific drinker lines and gender specific Big Z Drinkers, water spillage is eliminated as the drinkers are positioned at the proper height for both males and females. The advantage with no-spill drinking is a healthy, ammonia free and a more productive breeder environment.

Benefits of Ziggity’s Broiler Breeder Concept include:

• Dramatically improved male uniformity, livability and performance

• Dry slats and litter means virtually no ammonia release

• Improved bird welfare

• More hatching eggs and improved hatchability

• No bacteria-laden catch cups

The Poultry Watering Specialists

Learn more about Ziggity’s exclusive HEADS-UP™ breeder watering system at ziggity.com/HeadsUp

Mike Edwards, CEO, Jones Feed Mills

Jones Feed Mills Ltd. is a family owned and operated feed mill and food-grain supply business based in Linwood, Ont. With more than 130 employees, customers across North America and numerous suppliers, CEO Mike Edwards and his team faced unprecedented challenges in responding to COVID-19. Canadian Poultry spoke to him about the strict, proactive measures the feed mill took.

How did the pandemic affect your operations?

Well, it definitely had a major effect. What we started doing right away was meeting as a management team every day to discuss the new developments. We each took charge of a different aspect. All of the decisions we made followed step with what the government recommendations were.

Ken

Early on, we closed our office and our two stories to the public. And we put measures in place where basically customers contact us from outside. They can phone, email or we have a phone that they can use outside the building. We have a disinfection process for that. And they can do their business with us remotely. We offered curbside pickup fairly quickly.

You have dozens of employees. Did you make any adjustments around staffing? Yes, for one we made everybody site specific. We have five manufacturing facilities. And for each of the teams that work in those facilities, we made them specific to that facility. So, there’s very little if any traffic between facilities. Once you’re in your workstation or the building you work in, you stay in there.

We also implemented shift changes. So, we have an actual delay of shifts. Some of our facilities are 24 hours a day and there’s a 15-minute window there for cleaning and disinfection.

In our office, we identified who could work from home. We’d normally have about 30 staff daily in here. We cut that back, too. Now, we only have eight or nine people in here each day.

Has the pandemic affected deliveries?

As far as loading trucks, we also early on excluded all outside carriers from entering any part of our facilities. They basically stay in their trucks and we do the unloading and loading. Even our own truckers don’t actually go into the mills.

Fraser Valley Specialty Poultry is a family farm based in Fraser Valley, B.C. As the name suggests, they produce unique poultry like duck, geese and Taiwanese chicken. Early on in the pandemic, a handful of the company’s 100-plus employees tested positive for COVID-19. Canadian Poultry spoke to Ken Falk, the company’s president, about how they responded to that outbreak and what they learned from it.

Could you give us an overview of the

We have one of our staff in the middle. We’ll load them from up above so they don’t cross paths and they don’t contaminate each other’s work areas.

Did you have any issues securing PPE?

Yes, we did struggle with PPE supplies at first. And part of that was there were a number of people taking an active role in purchasing different supplies. So, we consolidated that down to one person and a very limited number of suppliers and we have it all delivered. We do a better job of that now than we did before.

Have you received any feedback from customers about the changes you’ve made to operations?

Really, for most of our customers, they wouldn’t have noticed a difference. Our sales team has been off the road. They’re only allowed to do scheduled important visits with customers. And we’re just in the process of relaxing that. We’re going to allow them to do more regular visits. Our customers have been very understanding. But they are now saying we need to have some more contact. We need to have people on the farm.

Do you have any final key takeaways from this experience thus far?

I would say this has been difficult. But we definitely are going to come out the other side of it a much stronger company. A little bit leaner, much better communication skills and a lot more understanding as far as what’s going on in the company.

outbreak your plant experienced?

We had a couple of people who, I suppose, came to work not feeling 100 per cent. But we can’t control where they go or what they do in the evenings. And so, they come to work maybe not feeling the best. We’re doing our prescreening like we were supposed to be doing and they weren’t demonstrating really any major symptoms –they just weren’t feeling that well.

And the one person in particular went home at noon and within a day her symptoms really started. She had gone in to

OCT. 20, 2020 12:00PM

Register for a virtual mentorship event with some of the most influential leaders in Canadian agriculture.

This half-day virtual event will showcase select honourees and nominees of the IWCA program in a virtual mentorship format. Through roundtable-style sessions, panelists will share advice and real-life experiences on leadership, communication and balance working in agriculture.

have a COVID test and self-isolated on the advice of 8-1-1. And within 24 hours or so we found out that she had tested positive. By that time a second person had begun to show some symptoms – mild but some. At that point we had all 103 staff tested. And out of that 103 we had seven positives, three of which ultimately had some symptoms while four were asymptomatic. One was more serious than the others, but none were hospitalized. They just recuperated at home.

How did the company move forward after that?

Fraser Health, our health authority, came to the plant to see what was going on and to make sure that those who were experiencing symptoms stayed home. And we said we will shut down for a day and get

Ashley Honsberger, executive director, Poultry Industry Council

In December, Ashley Honsberger became the new executive director of the Poultry Industry Council (PIC). Only a few months into her new role, the meetings and events world in particular was turned upside-down by the pandemic. Canadian Poultry spoke to her about being baptized by fire and having to make big decisions right off the get-go.

It wasn’t long into your tenure with PIC that COVID hit. What was that experience like?

The first hurdle for us was that we were approaching the April timeframe of hosting the National Poultry Show, which is, of course, a massive event where everybody gets together and shakes hands and

our bearings so that they could come in. So, we took that one day just to determine what went wrong within our systems so we knew what to fix.

Fraser Health came up with a list of risk areas that we needed to concentrate on. So, we shut down another day just to look after those things.

But, initially, we could only have about 25 per cent of our staff return for various reasons. Today, we’re running at about 70 to 75 per cent capacity. And it’s really challenging because there are so many protocols that we have to go through in terms of staff movement that takes much more time than we’re used to taking. But we’re very grateful to be running at the rate that we are.

If you could turn back the clock to the

hugs and catches up. So, that was probably the biggest decision as far as is it a go or not. Because, really, nothing at that point had been cancelled quite to that extent.

So definitely, it was a huge challenge. It’s taking ownership of this precious thing that’s been built by the industry over the years. For me to have to walk in and start saying, okay, we have to stop doing significant events and initiatives. It was definitely a huge challenge.

But I think the thing I really appreciated was that the whole board was supportive. And we had a ton of calls. I called my chair probably two to three times a day leading up to decision-making day. It’s just amazing to see everybody pull together and make the right decision at the right time.

What was the process like around deciding whether to postpone this year’s event or cancel it all together?

At first, in my ignorance, I thought maybe this will pass. But then once we realized it wasn’t going to happen over the summer, we didn’t want to impact other things that perhaps were happening. And we didn’t want to take away from the experience the National Poultry Show normally brings. And so just to host it and not know if it would be a safe environment for everybody – it just didn’t sit well with everybody.

early days of the pandemic, what would you do differently?

I suspect one of the first things we would do is make it mandatory for everybody in the plant to wear masks. At first, we were being told that masks don’t do any good. Now, we’re being told the opposite.

Are you doing anything differently around cleaning and disinfecting?

Yes, previously we were doing an evening cleanup where we would have our staff do a complete cleaning of the facilities, including shared areas like lunch rooms and washrooms. Now, we have several fulltime staff where the only thing they do all day long is continuously wipe down high contact surfaces. And so that’s a new cost of doing business.

So, ultimately, that’s why we cancelled.

Did you consider making it a virtual event instead?

We definitely talked about it. At that time, could we pull off a virtual event this year? I just don’t think that we had our heads wrapped around what that would look like. But definitely since then, we’ve been talking to Western Fair about having a virtual option available for the show, regardless of what happens next year. That way, people from across Ontario and Canada could participate in the show without necessarily having to travel.

When do you foresee returning to live events?

I don’t know. It’s very up in the air. Personally, I take a bit of a pessimistic view because I, fortunately, have access to scientists who work at the University of Guelph. They’ve been doing quite a few op-eds around how challenging the notion of a vaccine is, particularly with this type of virus, and how challenging the idea of herd immunity is. So, I’m not sensing that there’s going to be a silver bullet. And I know that’s really challenging for people. But knowing that maybe it’s not going to be very rosy for the next six to 12 months, I think we can prepare ourselves and the community.

Sign up for our e-newsletter eggfarmers.ca/newsletter Like us on Facebook Facebook.com/eggsoeufs Follow us on Twitter @eggsoeufs Follow us on LinkedIn LinkedIn.com/company/ egg-farmers-of-canada

A look at the benefits and cost of warming barns from the ground up. By

There are few Canadian poultry farming families more experienced with the many types of heating than the Cornelissens in Watford, Ont. To keep their broiler flock warm, they’ve used everything from box and thin pipe heaters to in-floor and hydronic heating.

In 2002, they built a new barn and became the first poultry farm in Canada to use geothermal technology as a heat source. But without hesitation, Kyle Cornelissen will tell you he prefers hydronic and in-floor heating. The benefits, he said, outweigh the costs. And they’re not alone.

Temperature plays an important role in terms of development and weight gain in broiler chickens. In poorly heated barns, growth can be stymied as birds utilize energy to stay warm rather than to put on weight.

How the barn is heated depends on

barn design and the type of heating system that’s installed.

In a broiler barn, the benefits of heating the floor directly beneath the birds are clear. Heat is distributed precisely where it’s needed most, minimizing energy loss and improving energy efficiency. Producers who’ve opted for this system say it’s a good investment, as it’s designed for longevity.

To create hydronic heat, special tubing is embedded in a concrete foundation. Hot water, which is heated in a boiler in a separate room outside of the main barn in most cases, flows through the tubing to warm the thermal mass flooring. Hydronic systems can be fixed with a number of boilers, including wood, oil, natural gas or solar heaters.

From a builder’s perspective, one of the big benefits is ease of installation. While some builders opt to zip-tie PEX tubing to

wire welded mesh and then pour concrete over top of it, a product from Amvic Inc. makes the process even simpler.

Amvic manufactures expanded polystyrene insulation material. Eight years ago, they introduced an insulated panel that holds PEX tubing. The Ampex Insulated PEX Panel interlocks and can be installed without a vapour barrier. Since PEX tubing easily locks in the panel, installation is as easy as walking the tubing in place.

“It’s designed so that as it holds PEX tubing it’s at a more optimum space than just laying it on top of the insulation,” explains Gary Brown, vice president, Amvic. “It actually allows concrete to flow around it, which gives it better thermal properties.”

The benefits of using hydronic heating in poultry barns include lower humidity levels, lower CO levels and better overall health, Brown says. Since heat loss is minimized, radiant floor heating is considered to be more energy efficient too. While it does take time to heat the thermal mass of concrete,

once it reaches the desired temperature it stays there, Brown says.

Although Wilma and Tony Baas of Russellview Farms Inc. in Russell, Ont. have been farming since 1991 when Tony bought the farm from his parents, they didn’t start in broilers until 2014. As first-generation broiler farmers, they wanted to see as many barns as possible before they built their own.

They were just about to give the go ahead on a conventional barn when they visited another farm near their home. The barn had in-floor heating and a cathedral ceiling. Wilma notes the air was clean and the floor was dry.

“We went to other barns too with the flat ceiling – it was eight or nine-feet high and it was darker and the air was very dense,” she says. “It was hard to breathe.”

Fernand Denis, a local contractor, designed and installed the system in the couple’s 400 x 64-foot barn. He stapled plastic tubing to two-inch Styrofoam, and then put the cement on top. The line is tough, Tony says, and should last forever.

For ventilation, the chicken produers went with a system from Hotraco Agri in The Netherlands.

The propane-fuelled boilers are situated inside the barn, but in their own room to improve safety and biosecurity. Using propane significantly lowers fuels costs, Tony says.

The Baases say there are several benefits to their system. In-floor heating produces even heating across the floor. Although they don’t have to use shavings, they use a little because the chicks like it. They save on the cost of shavings, as well as on the cost of heating. Cleaning the floor between flocks is a bit more difficult with fewer shavings, though.

“We priced it out and compared it to other barns,” Tony says. “Last winter we kept track of what it cost us in propane compared to other barns, and we were half the cost.” Last year, they paid $0.02/kilo of bird weight, on average.

The barn does not require an exhaust system either, as there is no CO2 in the barn. This saves them from further heat

loss as well.

The floor takes around two days to reach the desired temperature, and it can be trickier to get the temperature right in summer when the outside temperature is higher than the desired floor temperature.

But the couple has found ways to work around these issues. For example, they learned that closely watching the return temperature allows them to better control the actual temperature of the floor. Another benefit of in-floor heating,

Tony observes, is that the manure stays drier in the barn. This, they believe, has lowered ammonia levels and minimized footpad issues.

George Cornelissen started broiler farming in 1994. At that time, he had two double-decker broiler barns. One was equipped with box heaters, and the other with fin pipe heaters, the latter of which uses hot water to heat the barn. The system is 70 years old, but still runs well, although air distribution isn’t great.

Today, he manages six barns that hold 98,000 roasters together with his son, Kyle. Each barn uses a different system for heating.

In 2002, the Cornelissens built a new barn, which they designed for geothermal. The 32,000 sq. ft. barn holds approximately 22,000 roasters. While the in-floor heating system uses geothermal heat, the barn is equipped with box heaters as well. The systems are run together because infloor heat is really slow to react to temperature changes, Kyle explains.

“On a cold night when the temperature drops hard, the floor heat will respond too slowly,” he says. “To speed up that constant heat we have the box heaters to bring up the temperature quicker so the birds don’t get chilled.”

When asked why they didn’t just use the box heaters, Cornelissen says the exhaust that comes out of the box heaters contains carbon dioxide, moisture and heat.

“We don’t like to have that environment with the extra CO 2 and moisture in the barn,” he explains. “It brings up our humidity too high and we have to exhaust all that air out of the barn. In the wintertime, when we have to exhaust more air it costs us more in heating charges.”

In addition, the quality of the air they get from the box heaters is of lower quality than what they get from the hydronic heaters. “But box heaters are very cheap to install, so that’s why a lot of growers still have them,” he says.

When the geothermal system was first installed there was a lot of buzz in the

media, especially after Cornelissen Farms received the Innovation Excellence Award in 2007. Today, though, they don’t use geothermal energy as a heat source. In fact, they haven’t used it in over five years. Hydro costs skyrocketed, Cornelissen says, and the geothermal system runs strictly on hydro.

“With hydro prices slowly creeping up, it didn’t make sense to continue to run it,” he says.

Instead of using the geothermal units, they run in-floor heating using a natural gas boiler.

The last two barns they built in 2016 and 2019 are equipped with a fireproof room that holds the boilers outside of the barn. “Everything we do in the new barns is all hot water heat,” Cornelissen says. “We still have the in-floor heat, and then for the constant heat, we have the hydronic heaters.”

Each 32,000 sq. ft. barn is outfitted with five hanging hydronic heaters, and they have 1.15 million BTUs for heating the barn. All the boilers are in a room right beside the barn, which is up to fire code. Currently, this is not a requirement in Ontario, but the Cornelissens believe it will be in the short term.

Experience has taught the Cornelissens that in-floor heat using boilers and hydron-

ic radiators is the best option on their farm. Kyle says it’s all about the quality of the heat, which is clean.

“You’re not adding any more moisture or CO2 ,” he says. “In return, our humidity levels are lower, and we don’t have to exhaust as much air to keep the CO 2 down.”

The biggest drawback to hydronic and in-floor heating is the cost to build. Cornelissen says it’s one of the more expensive options. Per barn, he estimates they spent $70,000 for the in-floor heating and hydronic heaters.

“But longevity – I feel like we can get 40 years out of the system, and hopefully more,” he said.

By comparison, for the same sized barn, Cornelissen estimates both thin tube and box heaters set him back just $10,000. Box heaters and tube heaters, he says, will last about 15 years before they need replacing.

Beyond the cost to build, though, there’s still the cost to run the equipment to consider. Each year, gas costs about $0.01/kilo (bird weight), which is standard for all barns, Cornelissen says.

“The big thing we’re looking for is longevity,” he explains. “That’s kind of what we sell ourselves on – simplicity. It’s a very simple system. We know it’s going to last us a while.”

The Hog Slat team of service techs add field support to our network of local stores. We feature GrowerSELECT ® parts as cost-effective repairs or replacements for all types and brands of production equipment. Call us today to schedule an appointment.

Five practical best management practices to assist poultry farmers in averting these devastating events.

By Daniel Ward, P. Eng

The topic of barn fires and how to prevent them has received a lot of attention in Ontario over the past 10 years. The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) created a technical advisory group in 2007 to discuss this serious topic and develop some recommendations to reduce its’ occurrence.

The group has developed numerous factsheets and a booklet titled Reducing the Risk of Fire on your Farm in the intervening years. The ministry posted these resources on its website.

Looking at several of the broiler barn fires in Ontario over the past 10 years,

experts have observed a common trend around the timing of when the fire occurred. Often, it was just before chick arrival when the barn was being heated up or in the days immediately after chick placement.

The exact cause of the fire is often undetermined due to the degree of damage to the building. However, some possible reasons include dust and debris on heater surfaces after bedding placement igniting and dropping to the bedding on the floor when the heaters are started. Another possible cause is the heater malfunctioning during extended use when producers are warming up the barn.

There have also been fires that were

started during bedding placement – if the farmer was using a straw chopper in the barn and something caused a spark (e.g., a piece of metal in the straw bale), which ignited bedding.

This article will focus on five practical best management practices (BMPs) to assist poultry farmers in reducing the risk of barn fires. They are devastating events for farming families to deal with and the financial and emotional impacts are felt for many years. Using BMPs in the farm’s daily operations will reduce the risk of such a catastrophic event occurring.

Maintaining a clean and organized barn is a simple and cost-effective way to reduce the likelihood of barn fires. Practical actions like removing clutter and

properly storing combustible materials can limit the spread of a fire.

To reduce the risk:

• Keep clutter, bedding, and other combustibles at least one metre (three feet) away from electrical systems.

• Remove highly combustible materials such as cobwebs and dust from building surfaces and equipment like heating appliances.

• Routinely clean motors on fans, grain augers, etc., with compressed air to remove dust and debris.

• Ensure the barn is a smoke-free workplace and provide an outdoor location as a designated smoking area.

• Remove debris and clutter from fire exits and outside the building.

• Remove grass and weeds from outside the barn.

• Maintain accessible driveways around buildings during all seasons, including in winter.

2. Regularly inspect and maintain permanent electrical systems

The permanent electrical system is one of the most vulnerable areas within a livestock barn. The humidity and corrosive gases generated by livestock and manure degrade the electrical system. The Electrical Safety Code has specific requirements for the installation of electrical equipment within livestock housing areas due to the humid and corrosive environment

To reduce the risk:

• Ensure electrical equipment in concealed areas (i.e., within a wall or in an attic) is placed in conduit and junction boxes to prevent damage by rodents.

• Regularly inspect electrical equipment with a thermal camera to identify equipment that is overheating and needs to be serviced or replaced.

• Use equipment that is designed for the humid and corrosive environ -

ment of a livestock barn (NEMA 4X). Only replace existing equipment with the correct components for the environment.

• Consider using arc fault-protected electrical equipment.

• Maintain permanent electrical equipment such as fan motors or feed auger motors according to manufacturer guidelines.

• Keep combustibles away from electrical equipment.

“With attention to detail, fire safety risks to farm workers, emergency responders and livestock can be reduced”

3. Limit the use of temporary electrical equipment

Equipment that is not hard-wired into the electrical system is considered temporary equipment. This equipment may be plugged directly into an outlet using an extension cord or it could be powered from an external fuel source such as a standby generator. Extended use of temporary equipment can increase the chance of a fire occurring through degraded outlets and extension cords, which can be a source of ignition.

To reduce the risk:

• Use temporary equipment only in an emergency. Monitor temporary equipment regularly during its use.

• Do not use extension cords that are damaged or frayed.

• Store extension cords out of livestock housing areas to reduce corrosion on the components.

• Consider hard-wiring all permanent equipment that will be installed in the barn such as fans or heaters.

Keep a 10-lb ABC fire extinguisher within reach when using temporary equipment Note that an ABC fire extinguisher refers to the class of fire they are designed to extinguish: Class A for trash, wood and paper; Class B for liquids and gases; and Class C for energized electrical sources.

4. Regularly maintain heaters

To reduce the risk:

• Consider another heating source that eliminates open flames and other ignition sources inside the housing area.

• Ensure all natural gas or propane-fired heating appliances are installed as per manufacturer specifications and appropriate codes (e.g., the Natural Gas and Propane Installation Code).

• Regularly inspect heat shields to ensure they have not been displaced or damaged.

• Keep heaters suspended well above combustibles (bedding) or where they can be damaged by livestock.

• Suspend electric heaters (heat lamps) using non-combustible materials such as chains.

• If necessary, only use portable heaters designed for agricultural purposes (i.e., Stelpro FUHGX Agricultural unit heater).

5. Location of standby generators

Standby generators are a necessary item on a poultry farm to provide critical electricity to operate ventilation equipment, deliver feed and water to birds, etc. during power outages. These appliances are self-contained units powered by an internal combustion engine burning natural gas or diesel. The engine produces a lot of heat during operation. It is critical to provide ventilation to prevent the motor from overheating.

To reduce the risk:

• Locate the standby generator in a well ventilated, free-standing building away from the poultry barn or locate the generator in a well-ventilated room that is separated from the rest of the barn by a one-hour fire rated wall.

• Perform regular maintenance on the standby generator as per manufacturer recommendations.

• Ensure location where hot exhaust pipe transits through building wall has the appropriate heat shield in place.

It is possible to reduce the risk of fire on a farm by implementing these BMPs as part of the routine operating procedures. Simple actions like keeping a clean and tidy environment, properly installing and maintaining equipment and conducting a fire assessment are fire safety best practices. With attention to detail, fire safety risks to farm workers, emergency responders and livestock can be reduced and the trend of increasing financial losses reversed.

Improperly installed or maintained heaters are a common cause of barn fires. The presence of combustible materials such as bedding, dust, etc., in the barn is a contributing factor to fires.

» Outlet chevron design is

Tavistock, Ontario 1-888-218-7829 sales@ruby360.ca ruby360.ca

Quebec, New Brunswick & Eastern Ontario

Jacques Plante Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec 514-232-2539 jacques@ruby360.ca

British Columbia, Alberta & Saskatchewan

Lance Fluckiger Leduc, Alberta 587-926-0090 lancen@fluckigercarpentry.com

Genomics project aims to improve the health, welfare and productivity of Canadian turkeys.

By Lilian Schaer

New research is making the benefits of genomics available to Canada’s turkey industry. Hybrid Turkeys has teamed up with the University of Guelph to adapt technology already being used in laying hens and pigs by its parent company Hendrix Genetics to bring genomics-based breeding to turkeys.

Genomics will allow Hybrid to improve the accuracy of the genetic information it gets through the DNA of its birds by linking together DNA and phenotypic performance; it will also accelerate the breeding process.

It was Ben Wood, formerly a geneticist with Hybrid Turkeys and now an associate professor in the School of Veterinary Science at Australia’s University of Queensland, who first approached Christine Baes with the idea for the project when Genome Canada was seeking research proposals using genomics-based

technologies several years ago.

Baes is a professor in the University of Guelph Department of Animal Biosciences and Canada Research Chair in Livestock Genomics. She has extensive experience in genomics in the dairy sector, and now heads the five-year project to improve the health, welfare and productivity of Canadian turkeys. The work is focused in three main areas: meat production; meat quality; and health and welfare.

“The whole premise of the project is to connect these three areas of traits and make sure we have a really balanced and economically feasible breeding program,” Baes explains. “If birds are stressed, they won’t grow as fast and the meat won’t be as good.”

According to Baes, the poultry industry as a whole but turkey in particular has been highly successful in breeding to increase meat production. That said,

meat quality and health and welfare traits have been a key focus as well.

The challenge is developing a breeding system that focuses not just on specific production traits, but that those traits are also easy to measure in large number of animals, are economically feasible to include and that the breeding program is balanced with equal weighting of the different novel traits.

Baes and her team began with DNA samples from one male and two female Hybrid turkey lines. They started collecting phenotypic traits related to meat quality and production and health and welfare.

“The main premise of the project is to implement genomic selection in turkeys, so you take a piece of DNA and associate the genes in the DNA with the specific traits we want,” Baes says. “Then we come up with the optimal mix of genes so the commercial product is the best that it can be.”

Under the meat production pillar, the team is looking at carcass components, allometric growth and overall production value. The meat quality work includes meat colour, its sensory properties like taste and juiciness. In both areas, they are developing and implementing digital analysis to make it easier to measure those traits within a specific line of birds.

The health and welfare aspects of the project proved to be a bit more challenging, with Baes admitting the team didn’t really know how to start. So, they turned to turkey producers for help, asking farmers what they thought the actual problems in their flocks are.

“That’s never been done before in Canada and it gave us an idea of what they’re facing, from digital dermatitis and leg problems to why birds are dying,” Baes says. “If we understand why they’re happening, we can address through breeding.”

An analysis of corticosterone levels in feathers from over 7,000 birds gave insight into feather growth and how stress bars on the feathers can help identify at what age birds feel stress. Work related to egg production and broodiness helped identify genetic differences in birds naturally inclined to that condition so it can be avoided in future breeding activity.

And a study in collaboration with North Carolina State University into blackhead disease has provided data that will help determine what genes make some birds more susceptible to this than others. A final main analysis involved looking at levels of inbreeding and how to manage and understand its implications.

As part of the project, Baes and the team also developed an actual statistical methodology that they used to examine each of the traits, one focused on random regression that, although used in dairy, was never before applied in poultry. The second built on causal relationships that help identify specific traits that cause other traits.

According to Baes, the project has shown an increase in accuracy of genomic evaluations of 30 to 60 per cent compared

to conventional evaluations. Ultimately, farmers will see better birds, which is what drives the industry’s commitment to research, believes Hybrid’s R&D Director Owen Willems. “The main goal of our research is to produce actionable results that

can contribute to a more sustainable industry through progress in areas that address evolving market needs, trends and customer feedback,” he says.

The project, slated to wrap up by the end of 2020, is now in its final few months.

Time and again, the industry has voluntarily made changes to improve animal welfare.

By Mike Petrik

Poultry production has long been an important industry in Canada. And it’s always evolving. Just look at the courses offered at the agricultural colleges across the country.

In the 1970s, students applied to animal science courses, with emphasis on productivity and efficiency. In the 1990s, animal husbandry became the course description, with lessons devoting more attention to the birds’ environment, nutrition and care.

Since the turn of the century, poultry education has centered on veterinary medicine and animal welfare.

Everyone who works with poultry knows that course descriptions illustrate the changing attitudes of the general public towards animal production and the relative importance of all the aspects of raising poultry.

Everyone who works with poultry also knows that our industry is constantly changing. That said, the rate of change in the past several years has been unprecedented and directed by pressures from outside our industry.

All industries evolve, but the changes that have been adopted in the past decade have been revolutionary and fundamental. For various reasons, the public has become more interested in food production, while simultaneously being

more distanced from agriculture and ignorant of realities on the farm.

Consumers have put pressure on all agricultural industries to align more closely to the values that are based primarily on interactions with pets, since that is the only first-hand animal experience most people have. They expressed concerns

regarding animal housing, transportation, handling and food quality.

Various food production sectors have responded to these concerns, but the poultry sector has been exemplary in its response to consumer demand. Sector by sector, the poultry industries have not merely adapted to consumer demands,

but have reinvented and rebuilt production systems to better reflect the ethics of our primarily city dwelling customers.

Broiler production had been very consistent and predictable for decades. But recently, public pressure for antibiotic reduction, organic production and slower growth have changed the landscape significantly.

The amount of chicken and turkey meat that is sold under antibiotic free, no antibiotics ever, free-from and raised without antibiotics schemes have exploded. In fact, almost 50 per cent of production fills this market.

Farmers have also gone against the industry norm of producing birds in the most efficient manner possible by producing slow growing birds.

The main concerns facing egg farmers centered around housing. Much more emphasis on animal freedom and ability to perform natural behaviours meant that conventional cages would no longer be an acceptable housing method.

In 2017, the Egg Farmers of Canada voluntarily adopted the Code of Practice Care and Handling of Pullets and Laying Hens. This meant committing to phasing out conventional cages.

As a result, 95 per cent of barns across Canada must be rebuilt or retooled so that

all laying hens are housed in furnished cages or non-cage systems. This rebuild of requires a multi-billion-dollar investment by the egg producers, with no commitment for higher prices or consumption.

Egg boards have also invested in improving euthanasia programs and end-of-lay management of flocks. Programs adopting more humane methods of depopulation, including in-barn gassing with CO2, have been developed and expanded in many jurisdictions. What’s more, experts have developed standards and education for humane euthanasia across the country.

Many of the major poultry slaughter plants have made commitments to switch to CO2 stunning. This anesthetizes the birds in the crates they arrive in, thereby stopping the need to catch and hang conscious birds on the line. This improves welfare by reducing fear and stress on the birds, but does little to improve carcass quality, and with no assurance of

increased value to the meat produced.

The investments by these plants is in the millions of dollars and requires a complete rebuild of the receiving area.

Transportation of livestock in Canada is some of the most challenging in the world. Long distances and extremes in temperature and humidity make this an area of public concern, since the sight of trucks on the road is the most intimate contact many consumers will have with food producing animals.

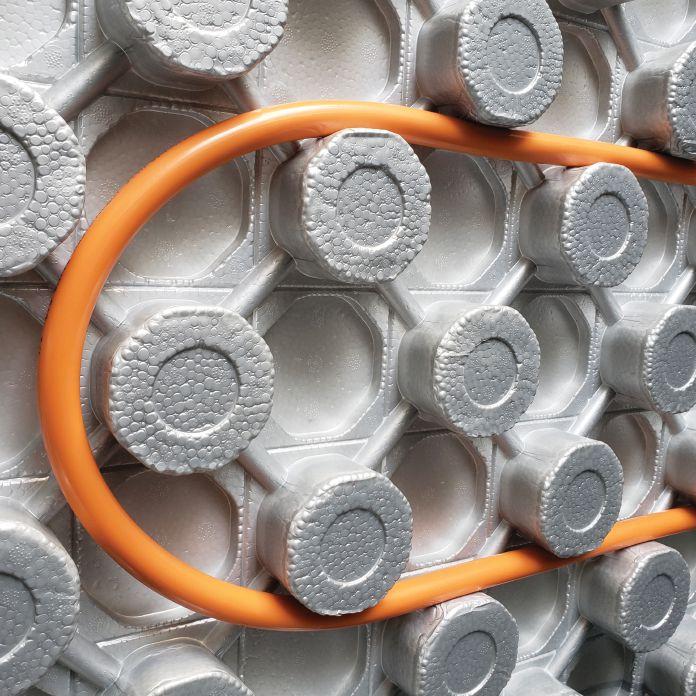

Poultry transporters have to adapt to the new Canadian Food Inspection Agency transportation regulations, which determine maximum distances, rest stops and fitness for transport. Yet, before these regulations were imposed, the industry had voluntarily committed to changing trailers, unloading equipment and loading areas to accommodate modular loading.

Many broiler and turkey barns also had to be modified to allow for modular loading. Modules result in an improvement in animal welfare by allowing birds to be loaded into conveyances inside the barn.

Once all the modules are filled, they can be quickly loaded onto a truck and begin their journey to the plant, rather than being exposed to the elements for the entire duration of loading.

This is important in both hot and cold weather, since the movement of the truck is crucial for ventilation and temperature control of the birds. Poultry are much more comfortable on a moving truck, and modules minimize the amount of time birds spend on a truck that is parked at a barn.

The Steele family has been in the turkey business since the 1980s. That’s when Ron Steele forged a partnership with Harvey Beaty, owner of Cold Springs Farm, to start producing heavy toms. Today, the Steeles run an integrated, multi-site and multi-age operation that also includes crops and a feed mill.

SECTOR

When Ron’s sons Matt and John returned to the farm after a stint with Farm Credit Canada, they purchased a few older turkey barns with quota attached to them. They were joined by their sister Julie, who now manages health and nutrition. The natural next step was the build a feed mill. After that, they set their sights on a 10 to 15-year modernization. That’s because they were looking to streamline and improve efficiencies in order to accommodate future growth.

The Steeles started their modernization by building a new 65 ft. by 500 ft. grower facility, which opened in 2019. Matt describes it as a “super low-cost barn”, largely due to its high efficiency tunnel ventilation system. It includes MagFans, which are variable speed and direct drive fans. The Steeles found energy consumption was 50 per cent lower in the new barn. It also included a Maximus controller, which allowed for remote monitoring. “Which is a huge step for us, coming from more manual, older style controls,” Matt says.