by Brett Ruffell

by Brett Ruffell

Two poultry marketing campaigns launched this year are looking to change minds – and consumption habits.

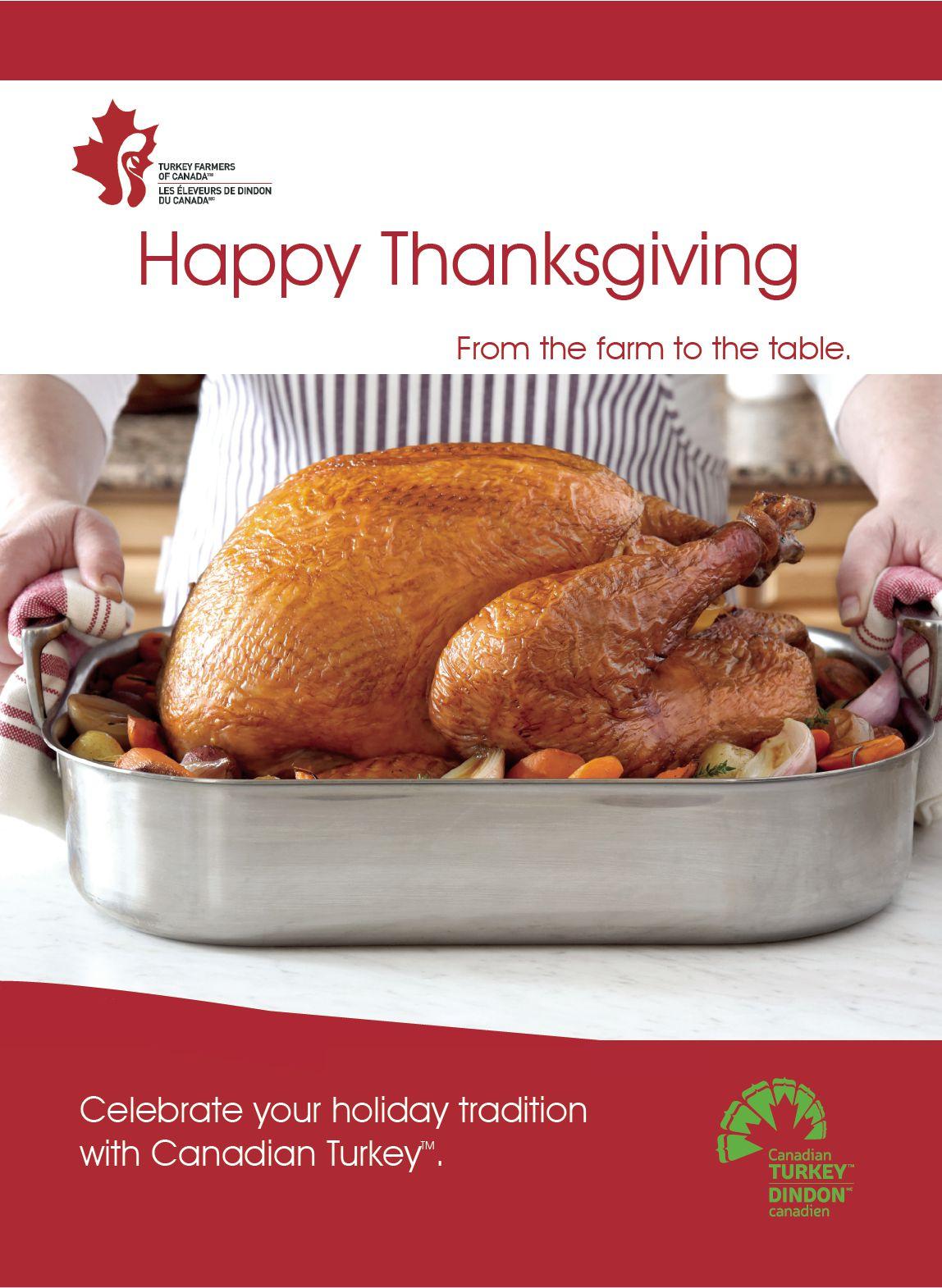

The turkey industry introduced Think Turkey in May while Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) rolled out Eggs Anytime in August. The goal of both initiatives is to increase consumption by reframing how Canadians view what these industries produce.

While we covered Think Turkey when it first launched, as a refresher it’s a collaboration between Turkey Farmers of Canada, the Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council and turkey primary processing sector members. It’s the first national, bilingual campaign to boost turkey consumption since 2004.

A five-year, integrated program, it targets primary meal planners and urges them to ‘Think Turkey’ at times when they’d usually consume another source of protein. For instance, with the message “What’s your beef with turkey?”, one ad suggests swapping a beef patty for turkey when consumers are in the mood for a burger. Another ad prompts consumers to pick turkey over chicken.

EFC is taking a similar approach. Eggs Anytime, which combines television, online and social media and runs into 2020, builds on a 2017 campaign that presented a “new”

kind of egg – the weekday egg. That initiative focused on moving people from consuming eggs for breakfast on the weekend to any day of the week. Eggs Anytime expands that to any time of day as well. The campaign uses bold and funny ads to show Canadians it’s normal to have eggs for lunch and dinner.

To take a deeper dive into the strategy behind Eggs Anytime, I spoke to Judi Bundrock, EFC’s chief marketing and communications officer. Firstly, she pointed out that the industry has experienced phenomenal growth for more than a decade. Just between

traditional breakfast food; they’re viewed as a high-quality protein that can be part of a varied diet and consumed throughout the day. With its latest campaign, EFC wants to bring more Canadians around to that way of thinking to get closer to the 300 to 350 eggs consumed range.

While it’s targeting all Canadians, Eggs Anytime is focused on one group in particular – a segment of the population EFC calls the ‘light buyers’. These are the 40 per cent of households research identified that eat less than a dozen eggs per month, typically on the weekend and only for breakfast.

Bundock and her colleagues set out to understand this segment.

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

National Account Manager

Catherine Connolly cconnolly@annexbusinessmedia.com 888-599-2228 ext 231 Cell: 289-921-6520

Account Manager

Wendy Serrao wserrao@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-6842

Account Coordinator

Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer Emily Sun

Circulation Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-442-5600 ext 3596

VP Production/Group Publisher Diane Kleer dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Circulation email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com

Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555

Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

2017 and 2018, the average Canadian ate 13 more eggs.

There’s also been a significant increase on the retail side as well.

Still, Bundrock sees room for growth. While she’s pleased with the fact that Canadians consume 250-plus eggs per year, she notes that people in countries such as Mexico, Japan and China are in the 300 to 350 annual egg consumption range.

One thing these countries have in common – consumers see eggs as more than just a “There were issues around time constraints limiting their ability to prepare eggs.”

“What we found out was the issue is not around affordability or awareness of the high quality of eggs,” the marketing expert says. “For some reason in their mind there were issues around time constraints limiting their ability to prepare eggs.” In short, they viewed cooking eggs as a time-consuming, complex process.

Thus, EFC is reaching out to these people – plenty of recipes in hand – to explain that there are many things they could do with eggs that range from simple to more complicated dishes.

To evaluate the campaign, Bundock says her team will continue to measure increases in consumption and retail sales. Will Eggs Anytime be able to convert a significant number of ‘light buyers’? Time will tell.

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $70.50 USD Foreign – 1 Year $79.50 USD

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2019 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

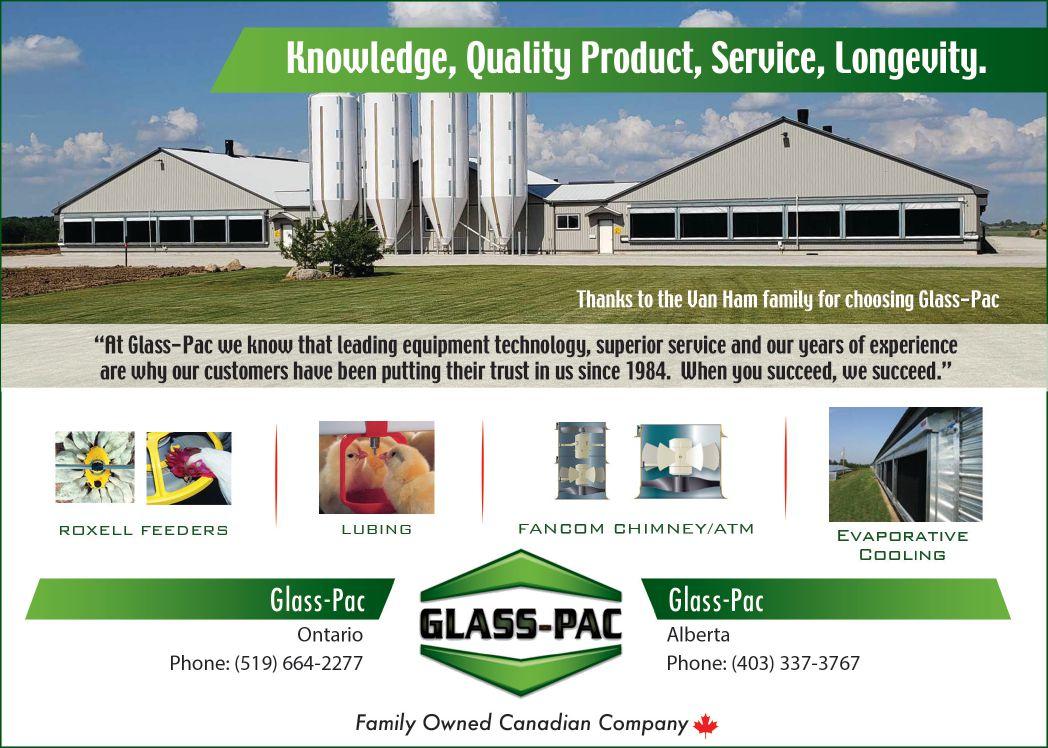

With LUBING’s OptiGROW drinkers you can say goodbye to Chicken Little and hello to Chicken Bigger! Customers using OptiGROW broiler drinkers are experiencing faster weight gains, better conversions and lower mortality rates.

pi

Large bottom pin that holds a drop of water to attract day old birds to nipple / great starts / average first week mortality below 1%.

) Greater side f rce allows all bird nd off to a g reater Finishes! ) to av 2 fo an G 1 2 3

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

o attract day old b verage m

Greater side flow with minimal triggering force allows all birds to easily trigger the nipple and get off to a great start. Great Starts =

Fax: (403) 337-3590 Les Equipments Avipor

Tel: (450) 263.6222 Fax: (450) 263.9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963.4795

Fax: (780) 963.5034

3) Both, vertical and side action, deliver the Opti-mum flow rates and ability to grow a 4 lb small bird up to a 10 lb Jumbo bird with the same nipple. After hundreds of house updates, customers are consistently seeing improved weight gains of up to 1/2 lbs/bird with dry litter conditions!

Many in the poultry industry are heartbroken by the sudden passing of Paul Leatherbarrow on August 16, 2019 at the age of 67. Born and raised in Elora, Ont., Leatherbarrow was a respected poultryman with 50 years of experience in the industry. He spent much of that time with Clark Companies and was also on the Poultry Industry Council (PIC)’s board. In recognition of his contributions to the industry, Leatherbarrow won the Poultry Worker Award in 2002. He was particularly fascinated by innovation in the industry and travelled internationally to bring to Ontario the technologies he learned of abroad.

Canadian dairy farmers who lost domestic market share resulting from free trade agreements with Europe and countries on the Pacific Rim will share $1.75 billion in compensation over the next eight years, Agriculture Minister Marie-Claude Bibeau announced in August. The sums will be allocated according to producers’ quotas, with an average farmer with a herd of 80 cows receiving $28,000 in the first year. Bibeau said negotiations are ongoing between the federal government and egg and poultry farmers, for a separate compensation program. She said money for those farmers will be available “as quickly as possible.”

Mike McMorris will be the new CEO of Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC). McMorris, most recently general manager of AgSights, assumes the position on September 1. He replaces outgoing CEO Tim Nelson, who’d been with LRIC since it was established in 2012.

August is when KFC’s Beyond Fried Chicken rolled out as part of an exclusive, one restaurant test, becoming the first U.S. quick service restaurant to launch such a product.

Kentucky Fried Chicken recently became the first national U.S. quick service restaurant to introduce a plant-based chicken, in partnership with Beyond Meat. Beyond Fried Chicken debuted in late August.

The new plant-based Beyond Fried Chicken offers a fried chicken flavor for those searching for plant-based meat options on-the-go.

is when Beyond Meat began developing its plant-based meat. Since then it has introduced several products across the brand’s beef, pork and poultry platforms.

Atlantans were the first to get a taste of KFC’s new Beyond Fried Chicken as part of an exclusive, one restaurant test. Beyond Fried Chicken is available in nuggets or boneless wings.

“KFC Beyond Fried Chicken is so delicious, our customers will find it difficult to tell that it’s plant-based,” says Kevin Hochman, president and chief concept officer, KFC U.S. “I think we’ve all heard ‘it tastes like chicken’ – well our customers are going to be amazed and say, ‘it

tastes like Kentucky Fried Chicken!’”

KFC turned to plant-based leader, Beyond Meat, to create a plant-based fried chicken that will appeal to lovers of both Beyond Meat and KFC. KFC will consider customer feedback from the Atlanta test as it evaluates a broader test or potential national rollout.

“KFC is an iconic part of American culture and a brand that I, like so many consumers, grew up with,” says Ethan Brown, founder and CEO, Beyond Meat.

“To be able to bring Beyond Fried Chicken, in all of its KFC-inspired deliciousness to market, speaks to our collective ability to meet the consumer where they are and accompany them on their journey.

“My only regret is not being able to see the legendary Colonel himself enjoy this important moment.”

latest poultry-related news, stories, blogs and analysis from across Canada at:.

Cyberbullying by vegan activists is a growing source of stress for farmers and agricultural producers who already face significant mental health challenges linked to the job, a farmer and a psychologist working in the agriculture sector say.

Farmer Mylene Begin, who co-owns Princy farm in Quebec’s Abitibi-Temiscamingue region, created an Instagram account a few years ago to both document daily life on the farm and combat what she calls “disinformation and the negative image,’’ of agriculture.

Today, she describes herself as the target of bullying from vegan activists.

Begin recently changed the settings on her account after having to get up an hour early to delete more than 100 negative messages a day – some of which made her fear for her safety, she says.

“There was one that took screenshots of my photos, he shared them on his feed after adding knives to my face and writing the word ‘psychopath’ on my forehead,’’ the 26-year-old says. “It made me so scared.’’

She says some of the messages compared artificial insemination of cows to rape, while others used the words “kidnapping’’ and “murder’’ to describe the work of cattle breeders.

The problem, she says, is that many city people don’t understand agriculture but become severe critics nonetheless.

“It affects you psychologically. It’s very heavy even if we try not to read (the comments),’’ she says. “The population has become disconnected from agriculture.

We all have a grandfather who did it, but today in the eyes of many people we’re rapists and poisoners, and that’s what hurts me the most.’’

Pierrette Desrosiers, a psychologist who works in the agricultural sector, says bullying on the part of hardcore vegan activists on social media is a new source of stress for a growing number of farmers.

“At school, the children of farmers start to be bullied and treated as the children of polluters, or else the kids repeat what they see on social media and say breeders rape the cows (when artificially inseminating),’’ she says.

“It’s now a significant source of stress for producers, and it didn’t exist a year or two ago.’’

Desrosiers, a farmer’s daughter and wife, is critical of the communications strategy used by certain animals rights groups and vegan associations.

“They use words like ‘rape’ and ‘murder’ to strike the imagination,’’ she says. “It’s anthropomorphism,’’ she added, referring to the attribution of human traits and emotions to animals and objects.

Beginning last year, the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food spent several months studying the mental health challenges facing farmers, ranchers and agricultural producers.

The report, completed in May, found that farmers are vulnerable to mental health problems due to “uncertainties that put them under significant pressure,’’ including weather and environmental challenges, market fluctuations, debt, and paperwork.

OCTOBER

OCT. 1-3

Poultry Service Industry Workshop Banff, Alta. poultryworkshop.com

OCT. 9-10

Alberta Livestock Expo Lethbridge, Alta. albertalivestockexpo.com

OCT. 24

PIC Annual Meeting Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCT. 27-29

AWC EAST 2019 Niagara Falls, Ont. advancingwomenconference.ca/ awca

NOVEMBER

NOV. 4-6

Poultry Tech Summit Atlanta, Ga. wattglobalmedia.com/poultrytechsummit

NOV. 21

Poultry Innovations Conference London, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

NOV. 27

Regional Poultry Conference St. Isidore, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

DECEMBER

DEC. 4

PIC Producer Update Belleville, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

DEC. 11

PIC Producer Update Brodhagen, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil

The Canadian Poultry Research Council (CPRC) approved funding for the first welfare research project it co-funded in 2006. That project investigated poultry transportation issues with the objective of identifying approaches to minimize stress on the birds during shipping and transportation.

The research was conducted by Trever Crowe from the University of Saskatchewan, who continues to study various transportation aspects and develop approaches for producers, transporters and processors to enhance poultry welfare.

Industry has continued to support welfare research as one of its most important research priorities. That’s because CPRC’s member organizations identified it as a main concern through annual

funding calls for proposals.

It’s also a major part of the three poultry science clusters that CPRC has administered on behalf of industry. The program, initiated by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) a decade ago, has had a major impact on agricultural research and has been a significant benefit to the Canadian poultry sector.

AAFC announced a third poultry science cluster in May. This supports more than $10.5 million dollars of research through both AAFC research facilities and Canadian universities.

It includes another $1.5 million in knowledge transfer and cluster-related expenses. Funding includes over $8 million from the federal government with most of the rest from industry. The third cluster focuses on four areas of research: Antibiotic stewardship; food

safety; poultry health and welfare; and sustainability.

While antibiotic stewardship was the overarching concern for industry and governments, welfare remains an important research priority. This support is clear from the continuing backing for welfare research in the new cluster.

Welfare research received funding of $2.0 million in the second cluster and $2.4 million in the third. This support is for direct welfare research and excludes research that would have an indirect welfare influence.

As well, much of the antimicrobial stewardship research targets improving the innate immunity of poultry and their inherent ability to fight disease. Improved health and ability to fight disease will also improve a bird’s welfare.

While the investment in wel-

fare research has increased 20 per cent between the second and third clusters, comparing the welfare projects provides some interesting information.

The second cluster had six independent welfare projects with five principal investigators (PI). The third science cluster has three projects with three PIs but, for the first time in a poultry science cluster, there are four subprojects with each led by individual researchers in one of the three projects.

This large project includes three researchers who had projects in the second cluster and a fourth researcher without experience of the poultry sector but with specialized knowledge and equipment.

The three researchers who were included in the second cluster are continuing to investigate some of the components of their previous projects in the new cluster. The new researcher provides expertise that brings together components of the research from the other three subprojects for analysis, a critical step in the overall research project.

This approach is becoming more common. CPRC has co-funded poultry research that has included researchers from a broad range of disciplines working with experienced poultry researchers.

These disciplines include genetics, engineering, human health and other biosciences. The cooperating scientists bring specialized knowledge to allow a project to examine broader questions being asked by industry and the research community.

By Lilian Schaer

Alternative housing options for poultry abound and there are likely more to come as the search for the best housing solutions continues and the Canadian industry inches ever-closer to drawing the curtain on conventional cages.

Burnbrae Farms has been working with free-run housing since its first single-tier freerun barns came into production in 1998. Today, two of those barns have been converted to aviary-style free-run housing – and in 2012, the company built the first enriched housing barn in Ontario.

In a free-run barn, hens can roam freely inside and lay their eggs in nesting boxes, whereas an enriched barn still houses birds in smaller groups, but provides nest boxes, scratch pads and perches.

“The trend is that as conventional cages need replacing, the switch is being made to enriched and free-run, but housing is still evolving,” says Craig Hunter, adding that Burnbrae has already been upgrading its first enriched housing facilities as the early ones did not meet the standards ultimately set out in the revised Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets and Laying Hens.

New Life Mills also has a long history with alternative housing system, starting cagefree production about 15 years ago, moving into aviary production about four years ago

and most recently adding enriched housing.

“The public seems to be demanding change and consumer choice is important,” says New Life’s Bill Revington. “If there is demand, we want to be part of meeting that demand.”

The alternative housing options certainly meet that consumer expectation of more freedom for birds. But the new systems come with their own sets of challenges, some of which conventional housing was originally designed to eliminate.

“The reason we got birds off the ground in the 1960s was so they didn’t recycle their manure – and we ended up with healthier birds, cleaner eggs and much better bird performance,” Hunter says.

In free-run and aviary barns in particular, it is harder to check on birds as they are free to roam inside the building. This also presents more chal-

“It will be interesting to see where the retail preferences go in the long term.”

lenges when it comes to catching, and Burnbrae estimates its labour needs are two to three times higher in those barns.

Those facilities are also dustier and with the birds being able to access their own manure, there is a higher risk of E.coli, necrotic enteritis and coccidiosis.

Both Revington and Hunter credit the industry for working hard to address emerging issues, though, from bringing new vaccines to market for E.coli and coccidiosis to breeding birds that are better able to adapt to the new housing environments, such as the more complicated social hierarchy that comes from living in a large group.

Small social groups in conventional housing led to less

feather-pecking and less aggressive behaviour, but in larger groups, competition and the pecking order structure is more complex, which means producers have had to re-learn how to manage birds in the new style barns.

They’ve also learned that birds going into aviary-style housing perform much better if they are reared in an aviary-style pullet house as well, as they learn to climb ladders and fly to perches on different levels at an early age. More exercise as a young bird leads to stronger bones to help them adapt better to the multi-tier environment, Hunter says.

Lighting management is also different than with a conventional cage system. According to Revington, New Life learned to stage their lighting so different sections of the aviary would come on at different times for different lengths of time to cue the birds’ behaviours.

Overall, though, birds in enriched environments are generally performing quite similarly to conventionally housed flocks, but there is a slightly greater chance of disease and mortality in the freerun and aviary systems, and egg production is not quite as high.

“Each offers its advantages and comes with its costs. If the consumer is prepared to recognize the additional cost, there’s no reason why we can’t continue with these systems,” Revington says. “It will be interesting to see where the retail preferences go in the long term.”

By Cindy Huitema

It’s been just over a year since I, Egg Farmerette, did any writing about our enriched colony housing barn. So, here’s an update on our experiences since our first flock hen placement.

In May, 2018, we gave our first flock of Dekalb hens a new home in the Farmer Automatic Eco II enriched colony housing system. To recap from my previous writings, this housing system caters to the birds’ natural instincts. When describing this housing to urban friends, I would compare it to flying first class or travelling in a limousine. It includes features such as two perches running the length of each house, curtained and darkened nesting boxes for laying eggs, scratch pads for dust bathing instincts, nail files for scratching behaviour and much more space to roam within each housing unit.

After housing the hens in mid-May, there were still some projects we needed to complete.

Before I go through those, I must comment on my husband Nick’s resourcefulness. Although I knew he was pretty handy during the build and with home renovations (I am sure fellow farmerettes can relate to this!), I am sometimes amazed at how many things he can do. Indeed, he’s earned the nickname MacGyver for his creativity and inventiveness!

Nick worked on getting the bathroom framing finished, having our plumbing apprentice nephew Andrew install a toilet and sink in this bathroom and completing the walls and counter so we would have a functional and clean bathroom space as part of the barn. This was built into some of the ante room space and

We look ahead to future growth and innovation on our family journey as egg farmers.

was always part of our design layout.

To finish the exterior of the barn, one of the first jobs was to apply vinyl siding. Our son John had a vision for what the outside of the barn should look like since we would see it numerous times every day. It is in plain view from the kitchen window, people can see the barn from the road and that it should be pleasant to look at, he noted. They got the siding done very methodically and chose which part of the barn to work on based on the location of the sun to avoid working in direct sunlight – you may remember that last summer was extremely hot, humid and dry.

We had the in-floor heating roughed in at the time the hens were housed in May, but as there was no need for heat in the summer, we could complete this later. As we learned during our previous year of construction, the barn building industry is very busy and you need patience when waiting for their availability. The in-floor heating got finished in December between Christmas and New Year’s after we pressured the installation contractor.

During the first week of the placement, Nick and John carried out doing an epoxy coating on the entrance/ante room and bathroom floors. They did this with the Beautitone kits from Home Hardware. This was a good first area to do before the packing room floor, which is at least four times more space to apply the epoxy coating to.

The epoxy coating for the packing room floor ended up getting done one year after the barn build completion and after the first flock was finished. In May of this year, John and Charlotte carried out this task, coating 500 square feet. The egg packer and any other items in the pack room had to be removed for this job and the empty cooler proved to be a good place for this.

We also had put off installing a counter/desk with cupboards until we knew the pack room floor would be completed. We put in two cupboards, a desk area, countertop and floating shelf, making this workspace

very functional and aesthetically appealing.

With John back at University of Guelph in his last year studying to achieve his Bachelor of Commerce, it was more difficult for the to-do list to get any checkmarks. However, he took advantage of the Black Friday sales and purchased a TV screen and camera package so that we could have eight different views of the inside and outside of the barn from the pack room vantage point.

The cameras got installed during the Christmas break and are a very valuable tool for barn security, hen care, monitoring the barn via cellphone when we’re off-site and checking on someone working in the barn.

We had our first third party audit last December. For readers outside the industry, egg farmers must undergo an

audit by an audit company from outside of the poultry/ agriculture sector. This includes inspecting the barn, housing, hens, hen care, flock and barn records and paperwork, as well as answering any questions that the inspector asks about your operation. Egg farmers are also inspected at least once a year by an inspector on staff with Egg Farmers of Ontario.

After sweeping our barn floor by hand for a couple months, we invested in a push sweeper to make this task less labour intensive for my daughter, Charlotte, and myself. Our new barn is at least four times larger than our old one, making sweeping a much bigger job.

At flock change time in May, after the barn was washed, we poured a cement pad for a fourth row of enriched colony housing. Our goal was to be prepared if the time and need arises in the upcoming year for more space for hens.

All of the above things we did have turned out to enhance our barn routine and barn appearance and have made our workplace a more pleasant and functional place to be.

Both Charlotte and John are keen to participate in the growth of the operation and embrace the technology and new barn routine. Additionally, Nick and I are getting used to the technology and ideas of our next generation of egg farmers. We look ahead to future growth and innovation on our family journey as egg farmers.

A growing trend in Europe, could it catch on in Canada? Two companies are looking to find out.

By Melanie Epp

While on-farm hatching has been a growing trend in Europe for the past 20 years, its adoption in Canada is fairly recent. A few companies have presented hatching systems at poultry events, piquing the curiosity of producers who’ve heard about their benefits.

While current on-farm hatching systems vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, the benefits of having immediate access to food and water are clear.

Research has found welfare, mortality and footpad health are all improved in on-farm hatching systems.

Standard hatcheries deliver chicks to the farm shortly after they hatch. The chicks receive their first food and drink when they arrive on the farm.

This usually occurs within 24 hours of hatching. In on-farm hatching systems, however, chicks have immediate access to food, water and chick paper, which is of great benefit to gut development and building a healthy immune system.

It also spares them the stress of transport.

The following two on-farm hatching systems were showcased at recent events.

Vencomatic, based in The Netherlands, offers a system called X-Treck, which was first introduced in 2006. The system uses setter trays that contain 18 day-incubated eggs, which are placed on a rail system that is suspended and positioned freely in the air. This placement ensures optimal airflow around the eggs during hatching.

By controlling the height of the system, the farm manager can manage airflow and temperature around the embryo.

On incubation days 19 and 20, the chicks hatch in the house and have immediate access to feed and water.

Direct feed and water access boosts the intestinal development and the immune system, resulting in robust broilers.

In combination with hatching in healthier air and making chick transport unnecessary, this forms the basis for further profitability in broiler production.

Making X-Treck work in Canada presents its own unique set of challenges, explains Tom Randall, Vencomatic North American sales manager for Canada. The roofs of Canadian barns are quite low, and extra room is needed for crews to come in and load the containers.

Furthermore, Canadian hatcheries use different sized trays than those in Europe. Randall says Ven-

comatic has been able to tweak the system to work in buildings using Canadian trays, though. For example, using a dolly that mounts in the track, producers can use 165 trays in the Vencomatic system, Randall explains.

The company has also developed extracts to work other trays, including the popular 84SST offset tray.

Canada’s colder climate also presents a challenge. With engineering support out of Europe, though, Randall says the company helps farmers in assessing barn layout and tray placement.

Another challenge is that eggs are not sexed before delivery. “Unless your system and your processing are accepting mixed birds, that may be an issue,” Randall says. “Some of the processors can sex birds or weigh birds in processing. But others still want a flock of males or a flock of females.

“That’s a whole other discussion,” he continues. “You’re not going to be sexing these birds in-house.”

Another on-farm hatching system currently on the market is NestBorn, a Belgian/Dutch system designed to address high equipment costs for farmers. Erik Hoeven, research and development, Belgabroed, explains how the system works.

The average barn in Belgium, which houses 40-45,000 birds, requires a 100 by two-meter space with five to six centimeters of litter. Once prepared, the hatchery delivers the pre-incubated eggs to the pre-heated barn.

Equipment providers says the benefits of on-farm hatching are that chicks get early access to feed and water and also it spares them the stressful experience of being transported from the

The hatchery takes the eggs from the incubation trays and places them directly on the floor using special equipment. The newest machines for this task are fully electric and can place up to 6065,000 eggs an hour.

The benefit of adopting the NestBorn system, Hoeven says, is that the farmer doesn’t have to invest in any equipment or machinery, and buildings do not need to be modified.

If for some reason the system is not a good fit for the farmer, they can switch back to conventional methods without losing money, Hoeven adds.

The advantage for the hatchery is that they do not need to leave their setter trays on the farm during the hatching process.

Concerning environmental conditions, the requirements are no different than those needed for day-old chicks, so a floor temperature of 28°C. Eggs are hatched between 33 and 35°C, he says (relative humidity > 30 per cent).

The hatchery and NestBorn team stay involved over the next three days and farmers receive coaching from a distance.

OVOSCANS – a device developed by Petersime – are placed in between the eggs and measure

eggshell temperature, the air temperature, relative humidity and levels of CO2.

The hatchery and farmer can consult their values in real time on a website (mynestborn.eu) and follow the hatching process from a distance, adjusting conditions in the barn as necessary.

Producers who are curious about the system have asked questions about broken eggshells and unhatched eggs.

Unhatched eggs, Hoeven says, need to be collected and removed from the barn.

Eggshells are left in the manure and removed with the litter at a

Here are more highlights from the Wageningen University study that compared on-farmed hatching to conventional hatching.

- In two successive production cycles on seven farms, a total of 16 on-farm hatched flocks were paired to 16 control flocks, housed at the same farm.

- On-farm hatching resulted in a higher bodyweight at day zero and day seven, but day-old chick quality as measured by navel and hock quality was worse for on-farm hatched birds.

- Body weight, first week and total mortality, and feed conversion ratio at slaughter age were similar for both on-farm hatched and control flocks.

- On-farm hatched flocks had less footpad dermatitis. This was likely related to a tendency for better litter quality in on-farm hatched flocks at 21 days of age in comparison to control flocks.

- No major differences in gross pathology or in intestinal morphology at depopulation age were found between treatments.

Source: Animal, Cambridge University Press

later date.

Farmers also ask questions about lighting needs. During the three days that it takes to hatch the eggs, Hoeven advises farmers to leave the lights on permanently but at a reduced intensity. This keeps the newly born chicks calm and helps them to find food and water shortly after hatching.

NestBorn will be present as a speaker at the Hatchery Education Day of the Ontario Hatcheries Association on Wednesday, October 30, 2019 in Guelph, Ont.

Bert Munsterhuis owns a traditional hatchery in The Netherlands. For the most part, he works with farmers in traditional systems. Only about five per cent work with on-farm hatching systems.

While on-farm hatching caught on quick in The Netherlands, growth has since slowed, he says. Munsterhuis attributes this to lost time, as farmers need an extra three days to hatch on-farm instead of growing.

“So, they’re losing three days of their time to grow them, so that is a disadvantage of the system,” he says. That disadvantage

could cost a producer.

It takes them a lot of time to get it right too, he adds. Management is definitely more intensive, which is a disadvantage for bigger farms that already have long to-do lists.

When they’re really busy, the same farmers who choose onfarm hatching switch back to traditional hatching because the system is time consuming and labour intensive, he says.

Munsterhuis says the hatchery manager does provide assistance during the early stages of adoption and most farmers who have made the changeover stuck with it.

In The Netherlands, Wageningen University researcher Ingrid de Jong conducted several studies comparing the health and welfare of birds hatched on-farm and in a hatchery. The on-farm hatching systems offered several benefits, including better litter quality, less footpad dermatitis, less dirty birds and less hock burn, De Jong says.

“In on-farm hatching, using the X-Treck system, we think the birds are more resilient to challenges from the environment,” she notes. “They seem to be more robust.”

In the commercial study, there was almost no difference in technical performance on some welfare indicators.

De Jong believes the improvements are the result of birds starting to eat within the first 30 minutes to 2.5 hours of their life, which helps with gut development.

At this point, the researchers are uncertain as to what is causing the differences.

De Jong says they plan to conduct follow up research in the near future.

The next batch of experiments, she says, will look at improving the resilience of broiler chickens.

The researchers will compare broilers from the hatchery with on-farm hatched broilers, as well as chicks that are hatched in the hatchery but then transported to the broiler farm. Their plan is to measure behaviour and welfare indicators in more detail, and the challenge birds with various diseases. This work will be conducted in the next year.

Some

producers are adding enrichments

to enable more natural behaviour. Do they enhance animal welfare?

By Mark Cardwell

Roost and relax.

That’s the guiding principle the Schroeders family use when thinking of ways to improve the decidedly short lives of chickens in the broiler barns they operate at five locations in Ontario’s Huron County region.

“It’s our unofficial motto,” says Jos Schroeders, who runs the family owned farming business with his brother Eric and sister Marie-José. “We’ve done a lot of work creating an environment where chickens can express more natural behaviour.”

In addition to increased natural lighting, improved air quality and drier bedding through the use of ventilation methods and technology used in Europe and the swine industry, the Schroeders have introduced several simple, homespun innovations they believe make their birds happier.

The most popular are step stools that birds can perch on or hide under, and pails with holes in the bottoms that are laid on their sides on barn floors.

“Chickens just love to sit inside them to hide and feel protected,” says Schroeders, whose family got into the organic broiler business in 2011 as a way to diversify their hog farming and commercial grain growing operations. “We have dozens of pails and they’re always in use.”

Some enrichment duds include small balls with bells that are popular with dogs and cats.

“Chickens are very picky about their toys,” Schroeders quips. “You can’t teach them to play fetch. But there are things they like to do. You have to experiment to find them – it’s really trial and error.”

Making chickens’ lives better, he adds, is both good animal husbandry and a smart approach to business.

“We take pride in producing poultry as

a food source in the most sustainable and humane way possible,” Schroeders says. “Our birds are more active now, there’s more background noise and combs are brighter on older ones. That’s only anecdotal evidence though – something a farmer knows. More research would be required to find metrics you could measure it by.”

Such scientific validation is now slowly emerging. In recent years, a growing number of animal researchers and poultry companies in North America and Europe

have been studying ways to improve animal welfare by finding alternatives to conventional production methods in which chickens are raised on the floors of solid-walled barns with artificial light cycles that only

allow a few hours of darkness daily.

The central premise is that enrichments allow chickens and turkeys to better express natural behaviours that enable them to lead happier, more meaningful lives.

Until recently, much of that animal welfare research had been focused on longer-living laying hens. But experts have now turned their attention to issues involving the production of both conventional and organic broiler chickens.

This fall, for example, animal research scientist Stephanie Torrey is conducting a study at the University of Guelph to determine if and to what extent broiler chickens even care about barn enrichments. “We just don’t know how much these things matter to them,” Torrey says.

To find out, the researcher is running a preference and motivation study using a small number of broilers in a barn on the Ontario university campus. The study involves a weighted door that the birds must push through in order to access things they enjoy, like dust baths.

Torrey has conducted similar tests using food and fake worms to test and determine everything from physical fitness to the behaviour of several chicken breeds.

She said trying to gauge a chicken’s level of contentment is far from an exact science. “We have to infer that an animal is happy or content or experiencing pleasure based on their behaviour,” Torrey says.

The results of a 2018 study by animal scientists at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands suggests that enhanced natural living conditions in broiler houses do have beneficial physical and mental effects on birds.

The study compared the effects of natural light versus artificial light on indoor-housed commercial broilers in three identical houses on a single farm. Other enrichment materials the researchers added to the houses included wood shavings bales, round metal perches and metal chains as pecking objects.

Carried out over five consecutive production cycles, the study compared the animals’ behaviour at 25 and 39 days of age and issues like lameness, footpad dermatitis, hock burn, cleanliness and injuries.

The findings suggested that the birds exposed to natural lighting and enriched environments walked, explored and foraged more than those without. “We concluded that providing environmental enrichment and natural light stimulated activity and natural behaviours in broiler chickens,” reads the study.

For its part, a recent scientific literature review on the use of various types of environmental enrichments found that elevated resting-places, panels, barriers, bales of straw, covered verandas and outdoor ranges “could” offer benefits in regards to broiler behaviour and overall animal health.

The review suggested that ideas for the practical application of broiler house enhancements –together with considerations of genotype, production system, stocking density, light, and flock size – “need to be further developed and studied, preferably in commercial trials.”

At least one big American poultry producer – Perdue Farms – has made a major commitment to finding ways to raise broiler birds more naturally.

Part of a sweeping care plan that Perdue launched in 2016, the plan revolves around the Five Freedoms for Animal Welfare – a set of ‘rules’ that were developed in Europe in the 1960s. As a refresher, they in-

clude freedom from hunger and thirst, discomfort, pain and injury, fear and distress and freedom to express natural behavior.

“It’s all based on the understanding that animals deserve an environment that provides them with the things they want and meets their basic needs,” says Bruce Stewart-Brown, a veterinarian and senior vice president of food safety, quality and live operations for Perdue.

The company harvests roughly 14 million broilers every week from approximately 2,000 privately owned farms across the U.S., making it the country’s fourth largest chicken producer and the number one brand of fresh chicken.

“We’ve done a lot of work creating an environment where chickens can express more natural behaviour.”

According to Stewart-Brown, Perdue continues to do research and testing to determine which enrichments most improve the lives of broilers over conventional production methods.

Earlier this year it also held its first Chicken Welfare Enrichment Design Contest, which invited Perdue family farmers to invent and successfully test devices that allowed chickens to roost, perch, play and exercise using. Inventions had to be easy to build, store and integrate into chicken houses.

The winning entry – a design dubbed The Carpenter Bench that consisted of a foot-wide, six-footlong shelf with a cleated ramp access and hinges for folding for catching and cleanouts – earned a North Carolina farming family $5,000.

“It’s clear that it’s good for chickens to get off the litter and have places to roost or hide,” Stewart-Brown says. “Doing things that enable them to do that seems more respectful to the animal. We’re very proud of the work we’re doing and to see our efforts to improve animal welfare evolve in this way.”

Salmet offers high quality, easy to manage cage free systems to ensure the highest laying performance.

The Pedigrow 2 rearing system for pullets has undergone some improvements. 3 versions are now available:

• Normal Pedigrow 2

• Pedigrow 2 with raised legs

• Pedigrow 2 with raised legs and closed top tier

Collaborative team evaluates common killing methods for effectiveness and welfare to develop evidence-based recommendations.

By Karen Dallimore

When poultry become sick, injured or exposed to the risk of disease it may become necessary for farmers to perform an effective and humane cull. Some of the methods currently available include cervical dislocation, carbon dioxide and the use of non-penetrating captive bolt devices.

In order to facilitate science-based recommendations, a collaborative team led by Tina Widowski and Stephanie Torrey at the University of Guelph (U of G) recently completed a multi-year project examining multiple on-farm killing methods for broilers, layers, breeders and turkeys. Collaborators included U of G’s Patricia Turner, Karen Schwean-Lardner of the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) and Suzanne Millman of Iowa State University.

Torrey is a senior poultry research scientist. As she describes, any method of

euthanasia needs to provide rapid loss of sensibility followed by a quick cessation of respiration and cardiac arrest that indicates death. In a series of recently completed research studies, Torrey and several other poultry scientists evaluated some of the currently available methods of euthanasia from an effectiveness and animal welfare point of view.

DISLOCATION: IS A TOOL BETTER THAN A TRAINED HAND?

The process of manual cervical dislocation is a common and effective method of killing poultry but it can be difficult emotionally on those performing the task. Use of this technique is further restricted in the European Union, where legislation has limited the use of manual cervical dislocation to birds weighing less than three kilograms and to 70 birds per person per day.

To address these limitations of use, R.

Amila Bandara, as part of her PhD research at U of G with Widowski and Torrey, investigated the efficacy of a novel mechanical cervical dislocation device for use in layer hens.

The researchers compared the commercially available Koechner Euthanasia Device (KED) versus manual cervical dislocation, measuring the time to irreversible insensibility, or brain death, in anesthetized birds.

Radiographs indicated that the majority of birds killed by manual cervical dislocation had dislocations between the skull and atlas (C1) or between C1 and C2 cervical vertebrae while those killed with the KED had the majority of dislocations between C2 and C3.

The KED caused less brain damage, resulting in longer times to brain death and cardiac arrest when compared to manual cervical dislocation. Based on the results of this study, the researchers suggest that

manual cervical dislocation remains a more efficient and humane method of euthanasia for layer chickens than the KED.

Caitlin Woolcott, during her MSc thesis at U of G with Widowski and Torrey, investigated the efficacy of a mechanical cervical dislocation device designed for the on-farm killing of poults and young turkeys.

Humane killing methods may be required for turkey poults between four and nine days of age that may have developmental abnormalities or unthriftiness which may pose a risk to the rest of the flock but up until now, no studies have investigated euthanasia methods for these particular birds. Cervical dislocation is commonly used but it can be difficult on both larger birds and very small birds, leading to

the development of a scissor-like mechanical cervical dislocation device known as the Koechner Euthanizing Device (KED).

In this experiment, birds aged one to three weeks were assigned to three groups – awake, lightly anesthetized manual cervical dislocation and lightly anesthetized mechanical dislocation. The use of anesthetic did not affect jaw tone, an indicator of insensibility, or pupillary light reflex, used as an indicator of brain death. However, it did allow for critical brainstem reflexes to be assessed while minimizing pain and distress to the birds.

Which one is the most efficient method?

Results here showed that mechanical cervical dislocation was not effective in killing one-week old poults compared to manual cervical dislocation, with more fractures and no dislocations. However, the KED was effective for three-week old poults.

Neither method caused immediate insensibility; manual cervical dislocation demonstrated a shorter time to brain death and more subdural brain hemorrhage.

Radiographs indicated that mechanical cervical dislocation caused more fractures and less displacement than manual cervical dislocation. Researchers did point out that mechanical dislocation devices vary in design and application and the results obtained in this study may not generalize to other devices.

The use of carbon dioxide is a common method of chemical euthanasia. Birds are chemically asphyxiated by the introduction of CO2. But, at what level would CO2 cause discomfort for the birds? In conjunction with professor Suzanne Millman from Iowa State University, Bandara investigated the aversion of turkeys to increasing levels of CO2

Typically, aversion has been measured by visual cues such as gasping and head shaking prior to the loss of posture, indicative of insensibility. But in this study, researchers decided to simply ask the birds. Eleven four-week old turkeys were subjected to a preference test. Birds were initially trained to enter a treatment chamber for food reward. Over the course of several days, the birds were then exposed to 25, 35, 50 or 70 per cent CO2 concentrations in the treatment chamber.

Of the eight birds that completed the testing, all eight would enter the treatment chamber at 25 per cent CO2 for their food reward, while three entered at 35 per cent, only one entered at 50 per cent and none entered at 70 per cent CO2 concentrations.

The birds were removed from the chamber for recovery and exposed to treatment on consecutive days. The research results suggest that a 25 per cent CO2 level is effective, not causing aversive behaviour while causing loss of neck tone indicative of loss of consciousness within less than one minute.

To evaluate carbon dioxide induction methods for the euthanasia of day-old

broiler chicks, Bethany Baker, as part of her PhD research at U of S with Schwean-Lardner, evaluated different CO2 induction techniques for their effectiveness in minimizing distress and inducing a rapid loss of sensibility and death.

A total of 110 cull chicks were either immersed in 100% CO2 or exposed to gradual displacement rates of CO 2 . Through monitoring behavioural responses such as head shaking or gasping the researchers were able to assess the welfare of the chicks up until loss of posture, which indicated insensibility, and cessation of movement and rhythmic breathing, indicating

death. Overall, the least distress and the quickest death occurred with complete immersion in CO2 compared to gradual displacement rates.

Bandara also evaluated the anatomical, behavioural and physiological responses of layers to the use of non-penetrating captive bolt devices to euthanize layer chickens.

In this study, three common commercially available models, the Zephyr-E, Zephyr-EXL and Turkey Euthanasia Device (TED), were assessed for time of loss to insensibility and degree of brain damage for four groups of male and female layer

chickens ranging from 10 to 70 weeks of age.

As with other methods of euthanasia, the intent was to assess the time required for the onset of insensibility and cardiac arrest to determine if these tools provided a humane and effective death.

A captive bolt is often used in larger animals such as cattle or sheep, but frequently requires a second step so that the animals do not return to sensibility. In layer chickens, however, the use of all three devices resulted in rapid insensibility through significant trauma to the midbrain and spinal cord and can be recommended as a humane one-step euthanasia device for all ages of layer chickens.

All three devices are applied perpendicular to the frontal bone, just behind the comb on a mid-line between the eyes and ears. Application causes a loss of the pupillary light reflex, nictating membrane reflex and breathing within five seconds of application by direct or indirect trauma to various regions of the brain, quickly leading to functional disruption and rapid brain death.

Slight differences were noted between the Zephyr devices that were attributed to the different shape of the bolt heads – flat on the TED versus round or conical on the Zephyr models – that delivered the force to and through the skull. External damage was evident on over 80 per cent of the birds, indicating a need to balance effectiveness with aesthetic and biosecurity concerns. While the Zephyr-EXL may be effective with lower air pressure levels in an attempt to alleviate external damage, based on

their observations, researchers recommend using the Zephyr-E in particular at 120 psi in layer chickens of all ages and weights to optimize its effectiveness. Other non-penetrating captive bolt devices are commercially available for layer chickens. For example, the Shelvoke Cash Poultry Killer is effective but heavier and more difficult to use. The researchers suggest that further evaluation is required on other lightweight, pneumatically powered devices.More research results using slightly different methodologies or birds are currently in preparation or review at various journals.

This project was funded by NSERC-CRD, OMAFRA, LRIC-PIC, Canadian Poultry Research Council, Egg Farmers of Canada, Hybrid Turkeys and Chicken Farmers of Saskatchewan.

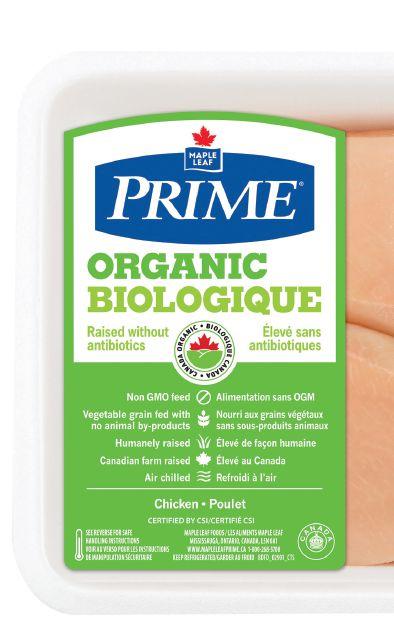

Whether it’s attributes such as flavour or texture, perceptions of health benefits, more availability or other reasons, demand among consumers for Canadian organic poultry products is growing.

Organic chicken producers in Canada both sell directly to their customers, such as Whispering Meadows in Desboro, Ont., and also supply larger food companies. Windberry Farms in Abbotsford, B.C., for example, started organic chicken production in 2011 and markets it through Fraser Valley Specialty Poultry.

What’s more, several organic chicken producers in Ontario are now supplying the new Maple Leaf organic program. In May, the company launched Maple Leaf Prime Organic Chicken in Eastern Canada through two major grocery store chains, Metro and Sobeys. It’s a full line of popular consumer cuts that includes boneless skinless breasts, boneless skinless thighs

and whole birds.

As for some of the other large firms, Maple Lodge offers one organic product so far, shaved deli oven-roasted chicken breast. And Peterborough, Ont.-based Yorkshire Valley Farms, Canada’s largest organic poultry producer at present, currently offers organic chicken, eggs and turkey products, including value-added fully-cooked meatballs and chicken pot pie. Both Loblaw (President’s Choice) and Wal-Mart currently offer organic eggs and more.

Maple Leaf says it’s pleased with its Prime Organic Chicken product sales since the launch this spring. In terms of feed sourcing, the Maple Leaf media team explains that the feed ingredients for its independent organic producers are purchased both within Canada and beyond.

“Meeting the requirement to be organic requires specialized non-GMO feed, which has some supply constraints. To this point, we’ve been able to secure adequate supply for our current program.”

To help develop both domestic and foreign markets for all organic products, the Canadian Organic Trade Association (COTA) has been awarded $992,000 from the federal Canadian Agricultural Partnership (CAP) Agri-Marketing Plan over the next three years.

Opportunities to promote the ‘Canada Organic’ brand will be explored and some market access issues will be addressed.

“Existing market issues are related to adventitious glyphosate residue on organic products, creating market barriers for export sales mostly, as well as GMO contamination issues,” notes COTA Executor Director Tia Loftsgard. “Issues of organic integrity are also addressed through our programming in which we look at any issues that might compromise or pose a risk to the industry.”

COTA is also reviewing import requirements and practises required by the federal government and existing related data gaps that prevent the industry from prop-

Here’s a sector by sector look at the state of organic poultry production in Canada.

Broilers

A Chicken Farmers of Canada member survey from 2014 showed that three per cent of farmers raise organic chickens and 20 per cent have free-range operations, which could include organic.

Layers According to Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC), 71 per cent of Canadian eggs are produced in conventional systems, 14 per cent in enriched colony and 14 per cent in specialty housing (i.e., free-range, free-run and organic) as of January 2019. Based on data from Nielsen, EFC also reports a demand of seven per cent of eggs at the retail level for eggs produced in specialty housing. There are also additional requirements for free-range, free-run and organic eggs in the food service and processing sectors.

Turkeys Data is spotty but organic production is believed to be about three per cent of total turkey production, according to Turkey Farmers of Canada.

erly evaluating business opportunities or challenges.

Organic poultry leader Yorkshire Valley Farms has had an active couple of years. Two years ago, the company launched its organic pasture-raised egg program for the 2017 season.

In addition to following organic practices, farmers in the pasture-raised program provide an enhanced pasture area for hens to forage outdoors. As with all Yorkshire Valley Farms laying hens, the pasture birds enjoy organic nonGMO feed and a cage-free environment in which to lay their eggs.

Since ‘pasture-raised’ is not a defined labelling term in Canada, Yorkshire Valley Farms worked to create a set of standards to which all participating pasture farmers must adhere.

These pasture-raised criteria incorporate the organic standards, while also requiring that hens spend a minimum of six hours outdoors per day, weather permitting, in an organically managed pasture that offers at least 20 ft2 (1.85 m2) per hen.

The realities of the Ontario climate mean that this enhanced pasture access can only be ensured for a limited period each year. The

pasture program generally runs from late May to October and the eggs are offered as a special seasonal offering.

When consumers buy a Yorkshire Valley Farms product labelled ‘pasture’, they are getting a product that comes from animals that have truly spent time outdoors, foraging on pasture.

Then last year in Ontario, Yorkshire Valley Farms finished a market expansion project supported by a $45,000 grant from the Greenbelt Fund. The funding helped the organic poultry producer expand its existing Small Organic Egg Program to 13 pasture-organic producers, expand market reach for these eggs and develop a new logo for cartons and point-of-sale materials, explains Greenbelt program manager Sagal Dualeh.

A video with one of the farmers was also created. Dualeh says the grant amount was below average and that Yorkshire Valley was chosen, among other reasons, because it had an existing market network where expansion was deemed achievable.

The Lefebvre family, who own and operate Ferme St-Ours in SaintOurs, Que., decided to start organic egg production at the end of the

“As they have access to outside, we need to be rigorous in the way to manage the layers’ outings, especially in the periods of bird migrations.”

1990s when demand for organic eggs started to emerge. In 1999, they began organic egg production with 2,500 organic layers, and by the end of 2020, they will reach 76,000 organic layers (they also raise all their own pullets).

Also by the end of next year, all birds on the farm (about 200,000 layers and pullets in total) will be housed in free-run systems (they also produce non-organic eggs on the farm).

David Lefebvre says the most significant current challenge in organic egg production is layer health. “As they have access to outside, we need to be rigorous in the way to manage the layers’ outings, especially in the periods of bird migrations,” he says. “Another challenge is the feed.”

Twenty years ago, when the Lefebvres started organic production, certification required that part of the feed be produced on-farm, and so the family converted their crop production to organic.

“At the beginning, we bought the organic feed, but the quality was irregular,” Lefebvre remembers. “As

we had begun our own organic grains production, we decided to build a feed mill in 2003, so that we could…have better control of the quality. Today, we produce a part of the organic grains needed to produce the organic feed for organic layers and organic pullets, and we buy organic grains from different local certified producers.”

The Lefebvres are also concerned about the regular five-year review of the Canadian Organic Standards occurring right now. Contributed feedback from stakeholders is open for public response this summer, and final updates to the standards will be in place by late 2020. Lefebvre fears that these updates might result in increased costs and production capacity decreases, as well as increased risk to layer health.

Regarding proposed updates, in early July 2019, the Organic Council of Ontario (OCO) reported that the associated ‘Working Group on Livestock’ “has had many heated debates on poultry farming conditions. The Revised Standard proposes, among other changes, to provide shade on outdoor runs, clarifies requirements for access to the outside and perches, and introduces the concept of ‘winter gardens.’” Watch OCO’s webinar on poultry outdoor access to learn more.

Lilian Schaer

Although Jonathan Giret was raised on a small beef farm near Springfield, Ont., his immediate career path after graduation from the University of Guelph took him out west and away from agriculture.

Five years in Alberta’s oilfields helped him purchase two farms near Dutton, and thanks to the Chicken Farmers of Ontario new entrant program, Jonathan and his wife Andrea, a high school teacher, became broiler producers, placing their first flock in January 2017.

Thanks to his certifications as a safety officer and a nutrient management consultant, he also launched Elite Agri Solutions last year, a consulting business to help fellow farmers with nutrient management, farm safety and grant applications.

Good business planning is what helped Jonathan oversee his barn building project and make the transition from day job to self-employment. In fact, according to the Agri-Food Management Institute (AMI) Dollars and Sense study, having a formal business plan in place is one of the

top seven habits of successful farmers.

Others include continuous learning, using accurate financial data, working with advisors, knowing and monitoring cost of production, assessing and managing risk and using budgets and financial plans.

“During my barn build, my business plan helped keep me sane. By having a plan and budget in place, I was able to track the build against my anticipated costs and make changes to accommodate overages,” Jonathan explains.

And now that he’s up and running, the plan and its one-year and five-year goals help keep him on track and prioritize by the numbers. His farm’s mission statement, he says, is “we make choices on math, not emotion.”

Benchmarking helps him with the numbers, too, and so far, he’s happy with his results. And he makes use of key advisors, which are mainly other farmers with more experience in the industry, but also lawyers, accountants and financial advisors who each bring their own specialty to the table.

Jonathan is an advocate for continuing education, prioritizing a large amount of his time into research, reading and attending industry events.

“Professional development is very important to me; I hope that through selfstudy and networking, I can avoid issues and capitalize on opportunities that I may not be able to otherwise,” he says.

Many of the top seven habits are linked and work well together, according to AMI executive director Ashley Honsberger, but they can also be applied individually.

“For farmers first starting down the business management path, it can be a bit daunting to think that you have to start with all seven habits at once,” Honsberger says. “But even making one change can have benefits for your farm business – and because many of the habits are connected, once you start one, the next one will come more easily.”

This story is provided by the Agri-Food Management Institute. AMI receives funding from the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative.

Opening Day highlights new and renovated barns and hatcheries. Do you know of a good candidate to be featured? Let us know at poultry@annexweb.com.

Hamlot Poultry Hillside broiler chicken farm was started in 2017 by Jerry and Rina Van Ham with their young children Nathan and Luna. Jerry had been poultry farming since 1999 with his parents. The Van Hams sell their chickens to Maple Lodge Farms, and its mainly marketed through Costco and Swiss Chalet. They purchase their feed from Masterfeeds.

LOCATION

Tillsonburg, Ont.

The Van Ham’s needed a second barn to expand to their current 70,000 birds. “Our goal was to create a more efficient and better environment for the birds,” Rina says, “and for ourselves.”

SECTOR Broilers View more photos at

Instead of having a separate feed system for each barn, a new central feeding system now supplies both barns. From four silos (Eurosilos) between the buildings, feed gets augured to one weigh system, then gets distributed to each barn’s storage hopper. This system also has the capability of blending other feed ingredients such as wheat.

“We also installed hot water boilers with multi-heat radiators/blow fans from WRC Plumbing, who did great work installing it,” Rina explains. She says, traditionally, they used box heaters to heat the old barn, which emit CO2 gasses. They converted the box heaters to the new type on the old barn and converted the lighting in the old barn to LED to make both barns identical.

TOP: From four silos between the buildings, feed gets augured to one weigh system and is then distributed to each barn’s storage hopper.

ABOVE: This system also has the capability of blending other feed ingredients such as wheat.

Are we in your news feed?

Stay in the know with Egg Farmers of Canada’s Facebook page. Get updates on Canada’s egg farmers, the latest egg farming news and upcoming events!

Like us on Facebook and visit eggfarmers.ca to learn more. Facebook.com/eggsoeufs @eggsoeufs @eggsoeufs @EggFarmersofCanada