Test your barn alarm

Check water lines for signs of leaks

Maintain uniform barn temps

Ensure generators are running properly

Check ventilation system for performance issues

Monitor any equipment with the BarnTalk Wireless Dry Contact Sensor, including generators, controllers, feed motors, and more.

BarnTalk automatically completes a self–test every two minutes.

BarnTalk detects no water flow, large leaks, and sudden changes in use.

With BarnTalk, get notified if barn temps fall out of your safety zone.

If your generator fails, BarnTalk sends an alarm.

If your ventilation system fails, BarnTalk sends an alarm. Call

or scan the QR Code to learn more.

by Brett Ruffell

COVID-19. Supply chain issues.

Drought. War. Inflation. The world has shifted dramatically in recent years.

I’ve written numerous times about how some of these disruptions have impacted poultry producers. Recently, I heard an expert give a different perspective – how these issues have affected the business of feeding poultry.

Speaking at the Canadian Poultry Research Forum, a virtual event hosted by the Poultry Innovation Partnership, Tim Armstrong, director of procurement and risk management with New Life Mills, detailed the range of challenges his industry has been facing.

The disruptions Armstrong described started just before the pandemic and continue to this day.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Armstrong explained, China took an aggressive approach to securing agricultural commodities and Western Canada exported much of its stored supply.

And then, the following growing season, the West experienced a significant drought, which shorted supply and elevated prices.

Adding to these challenges, pandemic-related lockdowns created broken supply chains. This included trucker shortages, shipping container shortages and port issues. “We

created a lockdown scenario where, for the most part, world trade – unless it was an essential item – basically stopped. We created a whole pile of issues,” Anderson said.

What’s more, the Russian/ Ukraine conflict has further created supply issues, as the Ukraine is a significant producer of commodities to the world. Russian sanctions further reduced supply, as Russia is also a major producer of commodities.

In addition, pent up consumer demand created by lockdowns and financed by government stimulus spending has fostered inflationary pressure. “Everybody was tired of being locked down in their basement

“We’ve definitely seen our challenges as an industry

over the last year and a half, two years.”

and we basically saw a significant amount of consumer demand in the marketplace, largely financed by stimulus spending, foster the inflationary pressure that we’re seeing today,” Anderson said.

Furthermore, green energy policies are competing for fats and oils once subsidized through carbon credit policies, which are now self-perpetuating due to the price of crude oil and the shortage to global energy supply due to sanctions on Russia. “Oilseed production for biofuel/biodiesel is linking our food chain and fuel

chain and it’s going to be interesting to see how that changes the markets,” he said. “What this is going to do to us in the industry or to our customers is it’s basically going to change grain-based commodities.”

Indeed, it sometimes feels like we’re on a runaway train. The question is: Where is it headed? Anderson doesn’t see this turbulence settling anytime soon. “We’ve definitely seen our challenges as an industry over the last year and a half, two years and, as I look at things going forward, I don’t think we’re going to see a lot of changes,” Anderson said.

“I think things are going to continue to ramp up here as we go into some trying economic times,” he added, referring to governments’ fight to ease inflation and growing worries about an impending economic recession.

On a similar but more positive note about feeding poultry, welcome to our first annual nutrition issue! In the pages ahead, you’ll read about cutting-edge research and more.

For broilers, we highlight promising work that looked at feeding chickens cricket meal and we also cover the impact of gut health programs in a world with fewer antibiotics. For layers, we detail efforts to assess the sustainability of feeding hens black solder fly larvae and also how tweaking trace minerals can improve layer performance.

And for broiler breeders, we highlight a new Canadian-led international educational initiative.

I hope you enjoy the issue!

canadianpoultrymag.com

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Rep. Tel: (416) 510-5113

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor

Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Brand Sales Manager

Ross Anderson randerson@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-925-7565

Account Coordinator

Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer

Curtis Martin

Group Publisher

Michelle Bertholet mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5183

COO

Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $91.50 CDN Foreign – 1 Year $103.50 CDN GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2022 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Our egg conveying systems safely transport a large volume of eggs from the nest to the processing area, which is why over 75% of all eggs produced in the U.S. are riding on a LUBING egg conveying system.

Our conveying systems are flexible, and can be adapted to nearly any configuration with curves, angles, heights and distances.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664-3811

Fax: (519) 664-3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263-6222

Fax: (450) 263-9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963-4795

Fax: (780) 963-5034

In September, highly pathogenic avian influenza returned to Ontario for the first time in four months with an outbreak in a commercial poultry flock in Oxford County. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency confirmed the outbreak at a farm in the township of Zorra, about 20 km east of London. The outbreak was the first in Ontario since May 18, when CFIA confirmed the last in a run of six on commercial farms in the Regional Municipality of York over a span of about four weeks.

The National Poultry Show, presented in partnership with the Poultry Industry Council, is moving to a new date for 2023. The show will be held February 8th to 9th at the Western Fair District Agriplex, in London, Ont. Over the past three years, there have been many outside pressures that have influenced the ability of show organizers to present an in-person event. In 2020 and 2021, the show was impacted by Covid-19 shutdowns and, most recently in 2022, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) during the spring migration season.

With members of his family in the audience along with the attendees of the Poultry Industry Council (PIC) annual charity golf tournament, Charlie Elliot was surprised to learn he was the second winner of the “Ed McKinlay Poultry Worker” award for 2020. Elliot has been working in the industry for over 43 years primarily in feed inputs, starting a long career after graduating from University of Guelph and taking his first job at a small feed mill outside of Ridgetown, Ont.

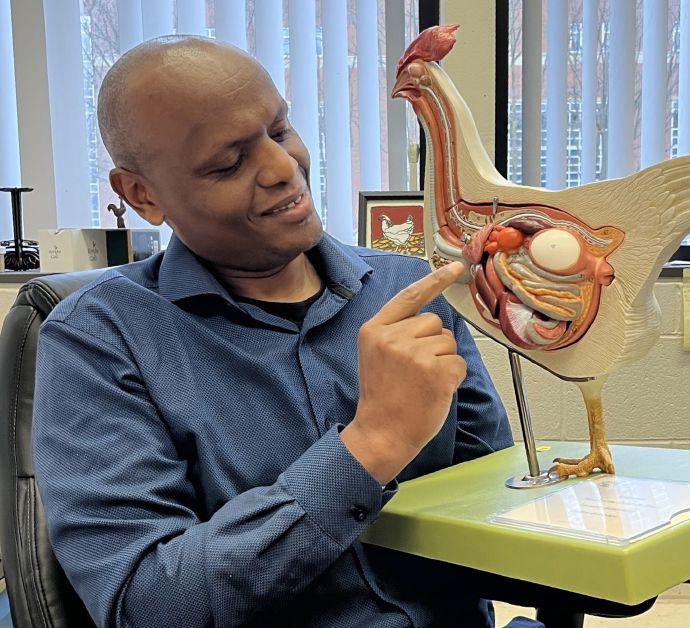

Dr. Shayan Sharif is a professor in the Ontario Veterinary College’s Department of Pathobiology

brings together Canada’s top health and biomedical scientists and scholars to address the country’s major health issues.

Two University of Guelph researchers, including a well known poultry expert, have been recognized for their expertise by the Canadian health sciences community. Dr. Dorothee Bienzle and Dr. Shayan Sharif, both professors in the Ontario Veterinary College’s Department of Pathobiology, have been elected Fellows of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS).

CAHS brings together Canada’s top health and biomedical scientists and scholars to address the country’s major health issues. Fellows volunteer their time and expertise, evaluating these challenges and providing practicable, evidence-based advice to improve the health of Canadians.

Sharif investigates how the immune system recognizes and responds to zoonotic pathogens — diseases that spread between humans and animals — as well as emerging pathogens.

Globally recognized for his work on animal-pathogen interactions, Sharif is an expert on the avian influenza virus and studies food-borne pathogens that can be passed to humans via poultry products. He and his team

develop immunization and other methods to curb the impact and spread of these diseases.

Sharif leads the Poultry Health Research Network, a team of poultry health experts from academia, government and industry. He also co-leads a translational health initiative at U of G that brings together veterinary and human health research to usher scientific discoveries from the lab into treatments.

Sharif advocates a One Health approach — recognizing the interdependency of human, animal and environmental health — to address complex health issues.

“Climate change, population growth, changes in wildlife habitats, international travel — so many factors affect the emergence and spread of novel and zoonotic pathogens,” Sharif says.

“To mitigate the risk of future pandemics and emerging diseases of animals, we need a One Health approach. This is what I want to promote as a Fellow, to encourage us to bring our different sets of knowledge and perspectives together and work collaboratively across disciplinary divides.”

By Crystal Mackay

Have you ever asked anyone, “What is your favourite part of your job?” I can guarantee you will hear a very common answer, particularly in agriculture, “The people.” At the same time, one of the most important threats facing the poultry sector is human resources. If people are our greatest strength and our greatest weakness, it’s time to build some bridges.

My previous articles in this series explained how we build bridges to help us get over obstacles and serve as a means of connection when it comes to earning trust and connecting with consumers. Ask anyone about their experiences hiring new staff recently and they will most likely describe some obstacles. While the agri-food sector prides itself on innovation, investing in new technology, equipment and research, how much do we invest in humans?

Here’s an example. Organization ABC hires a new person. They welcome them to the team with business cards, maybe a golf shirt and a hat with their logo on it. Perhaps the keys to a company vehicle, which could be an $80,000 truck or access to pieces of equipment worth five times that amount.

But what does onboarding, mentoring and training look like? What’s the business value put on people in real dollars, time and energy? Beyond re -

cruiting new hires, keeping and engaging existing employees has never been more important.

In McKinsey’s 2022 Great Attrition, Great Attraction 2.0 global survey, the top reason people gave for quitting their job was lack of career development and advancement. This topped the reason many might predict of inadequate compensation.

The third reason was uncaring and uninspiring leaders, followed by lack of meaningful work.

These results fit well with some other studies and theories about what people want in 2022 and moving forward, particularly young people. We want to feel valued, and part of a team that works towards a common goal that makes a difference.

So, what can you do? At a time when many are so busy with tasks and trouble shoot-

If people are our greatest strength and our greatest weakness, it’s time to build some bridges.

ing, it takes a strategic effort to make training and engagement a priority. For example, invest in creating a positive work culture where ideas are encouraged and saying thanks is a regular occurrence. Team building, fun events and rewards can go a long way towards this goal. For example, think of a charitable cause your team can help with locally that will help build morale and make a difference at the same time.

Everyone should map out their personal and professional goals and plans, with training and development budget to support them. This can be formal courses or programs, coaching, in-house training or mentoring.

Check out the online training programs on utensil.ca for a simple and affordable option to get started.

Attending industry events to build their networks is another area that hasn’t been given enough value. The experienced people in our industry know this best – agriculture is a people business, and you can’t build relationships with e-mails or texts. Coming through the past few years with travel and events at a minimum, this aspect of professional development and networks needs to be given priority.

According to a report by the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council, approximately 37 per cent of the workforce on Canadian farms is expected to retire by 2029. They also shared in 2019 that nearly half of employers report struggles filling their labour needs. Those numbers are staggering and continue to escalate.

We need to invest in our skills, such as leadership, human resources, communications, and sales and marketing. But we also need to have some fun, say thanks for good work, and help energize our teams and ourselves for the year ahead. This is important for the new hires we welcome to our teams, those who have been working hard for and with you, and for you.

Loft32’s the Grow Our People Summit ‘unconference experience’ is coming to Niagara Falls this November 2-4. Find out more and register at loft32.ca/ growourpeople.

• Use less straw (also works for shavings)

Use less straw (also works for shavings)

• Create a base that is nice and flat for waterers & feeders

• Save on fuel vs. blown in bedding

• Fast and easy process, can be done by 1 person

• Barn setup according to your own schedule, not dependent on weather

• Barn setup according to your own schedule, not dependent on weather

• 9’ Fork (9’ 8” Overall Width)

• 9’ (9’ 8” Overall Width)

• Available in Skid Steer, ALO & Manitou mounting configurations

• Hydraulically Driven using aux. machine hydraulics

• Levelling jacks to set bedding depth

• Levelling jacks to set bedding depth

• 5’ Fork (70.5” Overall Width)

• 5’ (70.5” Overall Width)

• Fits standard Ventrac / Steiner implement

• Fits standard Ventrac / Steiner implement mounting brackets

• Belt Driven using machine drive pulley

• Levelling jacks to set bedding depth

• Visit our website for links to videos of the Rotary Fork in action

Visit our website for links to videos of the Rotary Fork in action

Another great product from:

Another innovation available from: County Line Equipment

Another great product from:

8582 Hwy 23 N., Listowel ON N4W 3G6

Line Equipment Ltd. 8582 Hwy 23 N., Listowel ON N4W 3G6

8582 Hwy 23 N., Listowel ON N4W 3G6

PH. (800) 463-7622

PH. (800) 463-7622

PH. (800) 463

www.county-line.ca info@county-line.ca

PH. (800) 463-7622 www.county-line.ca info@county-line.ca

By Lilian Schaer

Arecently completed study at Dalhousie University shows cricket meal has potential as a protein source in Canadian broiler chicken diets. Crickets aren’t yet on Canada’s list of approved feed ingredients for poultry, but this research is an important step towards receiving that approval, says Stephanie Collins, Associate Professor in Monogastric Nutrition in the university’s Department of Animal Science and Aquaculture who led the project.

“The main issue here is food security and in the case of poultry producers, that means affordable and available feed ingredients,” explains Collins. “Especially now, we are seeing drastic changes in feed costs and competition for feed ingredients from other industries, so we need to have more available alternatives to choose from when formulating diets for poultry.”

Poultry naturally consume insects so adding crickets as an approved feed ingredient – the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) approved the use of black soldier fly larvae in poultry feed in 2019 – is a powerful way to give the poultry industry additional tools, she adds.

Collins’ work included two different trials, but both were conducted at the Atlantic Poultry Research Centre on Dalhousie’s faculty of agriculture campus in Truro. A digestibility trial, which went

towards the master’s work of graduate study Holly Fisher, looked at different types of cricket meal products compared with black soldier fly meal and a control group of soybean meal.

The trial included 320 birds who were fed the experimental diets for 21 days. Between days 15 to 21, students collected manure from the birds and analyzed it for nutrient composition and energy and calculated apparent available nutrients.

The birds performed well across all test ingredients, and results were comparable in digestibility and protein profile. “The most important thing was it generated

data for formulation using oven-dried and freeze-dried cricket. Both are a good source of protein although at 40.4 per cent available protein, oven-dried was higher than freeze-dried,” Collins says.

The accompanying research was a growth trial where birds were fed different levels of dried and ground cricket meal in non-medicated feed diets. Cricket meal made up 15 per cent, 10 per cent, five per cent and zero per cent of the broiler chickens’ diets and their meat quality was evaluated at the end of the trial. It ran for

a 35-day production cycle and included 624 birds. There was no detrimental impact on bird growth at any of the cricket meal levels, as well as no difference in intestinal lesions, nor any detrimental impacts on meat quality.

“What was interesting was that the lowest five per cent cricket meal inclusion level didn’t perform as well as higher inclusion levels, so a future research direction could be to look at why that is,” she says. “The final live weight of the 5 per cent birds was lower than birds fed the 10 per cent cricket meal inclusion diet, but they were still healthy chickens.”

Cricket ingredients for both trials were provided by Midgard Insect Farms Inc., a Nova Scotia-based cricket producer. Broiler used were Ross 308 strain.

Additional research needed

More research trials will need to be done to gather enough data for CFIA review and approval of cricket meal in broiler chicken rations. Collins says there is also potential to investigate suitability in laying hens or turkeys, as well as looking at the potential that other insect components could offer poultry production. There is also interest in other insect species like mealworms too.

“We could investigate different bioactive compounds, extract them and see if they have other attributes that could be beneficial – this could especially be of interest for raised without antibiotics production,” she says, adding that protein concentrates could also be an alternative to ground crickets. “Insects present a lot of potential for the poultry industry but also for people who might want to go into cricket production.”

Cricket meal was approved for broiler chicken diets in the European Union about a year ago, and Collins believes the Canadian industry can watch and learn from developments in Europe while waiting for it be given approval for use in Canada. Already, producers eager to experiment with insect protein can opt for black soldier flies.

By Madeleine Baerg

Over the past 60 years, broiler genetics have improved dramatically, resulting in leaner, faster-growing, more efficient birds. However, because broiler breeder management research is so expensive and complex, technologies and practices haven’t kept pace with genetic improvements. The result is that the toolkit of management practices producers rely on today is nearly identical to what their predecessors applied decades ago.

The gap between genetic potential and management reality translates to breeders coming into production late, poor flock uniformity and fertility challenges: all lost opportunity for producers and inefficiency for the industry. Alberta’s Poultry Innovation Partnership (PIP) wants to change that.

In late June, PIP launched the Feeding Breeders Summit: a bringing together of the brightest minds in broiler breeder research and production from around the

world. The initiative featured an eightweek webinar series of presentations by world-renowned experts in broiler breeder production.

Once a collective baseline of knowledge was laid via the webinars, participants gathered in-person in Canmore, Alta., and online for a two-day summit at the end of August. Working together, they charted a path forward for broiler breeder production.

Valerie Carney, PIP lead, says her rationale for spearheading, ring-leading and tirelessly organizing the webinar series and Summit stemmed from frustration.

“What we’re facing today is birds that are much less resilient: they’re much more susceptible to any kind of disruption or stress and they don’t always respond to stimuli like lighting in a way that we expect them to.

“People use the analogy that broiler breeders have become like Ferraris to

manage. They’re very high maintenance. They need a lot of attention. Given very narrow margins, that decreased productivity is a real problem. We all know the issues, but – until now – we haven’t been collaborating.”

In November last year, Carney pulled together an organizing committee from various parts of the broiler breeder industry. Initially, they thought they could pull off a simple conference event by February. However, their vision and reach soon grew.

“At the beginning, we were just talking about Alberta and then we started talking about expanding to all of Canada. Then, Val took that vision and made it grow to something even bigger,” says Jeff Notenbomer, a broiler breeder producer from Southern Alberta, chair of the Alberta Hatching Egg Producers, a director on the Canadian Poultry Research Committee and former PIP chair.

Bigger, indeed. The one hour per week webinars, which took place over eight weeks between June and August, featured

nearly 20 leading geneticists, veterinarians and avian scientists from Canada, the U.S., Europe and beyond. Presentations covered multiple perspectives on broiler breeder feeding and productivity, from nutrition and gut health to genetic advances, disease and more.

“The plan from the get-go was always that it was going to be a summit, but we started to realize that there’s so much information and it’s so interrelated that there’s no way we could cover it in just a couple of days,” Carney says.

“The webinars were kind of the educational component leading up to the more collaborative component, which was the summit.”

The summit itself drew together participants’ expertise to identify feeding issues, explore best practices and prioritize research objectives to sustain the future of the industry.

The event’s value was much less about specific takeaways and production strategies and more about future potential derived from new relationships, fresh collaborations and aligned agreement for research.

“One of the biggest positive results for this summit was that we started to develop a network so we can consider different perspectives, learn from each other and start to grow a community,” Carney says. “A lot of us in this industry are getting on in our careers. Part of the importance of this summit was finding a way to start future proofing: working together and collaborating to get more out of research projects than each of us individually can do and building for the future.”

Another major priority summit participants identified and committed to is knowledge mobilization.

“It’s more than just putting information out there: what we meant by mobilization is really about the collaborative effort to get research into on-farm practice,” Carney says.

Martin Zuidhof, a professor of poultry systems modeling and precision feeding at the University of Alberta and a mem-

ber of the summit’s organizing committee, says coming to strong consensus on two research priorities – the improving of uniformity within flocks and the improving of grading for more targeted feeding – has him excited about the future.

“I’m working on those priorities myself daily, so it’s gratifying to see that I’m not alone. Stay tuned. These are themes that resonate and now there is a list of people who are committed to making progress towards solutions. We won’t have solutions immediately but we’re well on our way to a more integrated approach to arriving at solutions.”

While the big picture priorities may offer industry the longest term and most meaningful difference, countless ideas and takeaways from individual presentations and discussions “really got my brain going,” Notenbomer says.

He says he was particularly interested to hear how different countries handle similar challenges. Contrary to many Canadian farmers’ focus on technology, some of the very biggest productivity gains being made in other parts of the world aren’t being realized because of high tech tools, artificial intelligence or automated management.

“Some countries have way cheaper labour forces than Canada. With more labour, there’s a lot of potential of what you can make birds achieve,” Notenbomer explains.

“While that’s not always possible in Canada, the discussion definitely opened my eyes to what’s possible if you put in the hours in terms of feeding them and sorting them for improved uniformity. The numbers that some countries are putting out are pretty amazing.”

The fog generated by PulsFOG will cover all hard to reach areas Assortment of PulsFOG models to choose from

By Lilian Schaer

New research from the University of Guelph shows that broiler chicken producers can transition to production systems with minimal or no antibiotics without impacting bird performance.

Given global concerns around antimicrobial resistance, Canadian poultry producers are adapting their production practices to meet mandated reduction and elimination of antibiotics that have long been used in production.

Gut health programs are seen as key in maintaining bird health and performance when antibiotics are no longer used or used to a lesser degree. But a lot is still unknown around how different feed additives perform in commercial settings.

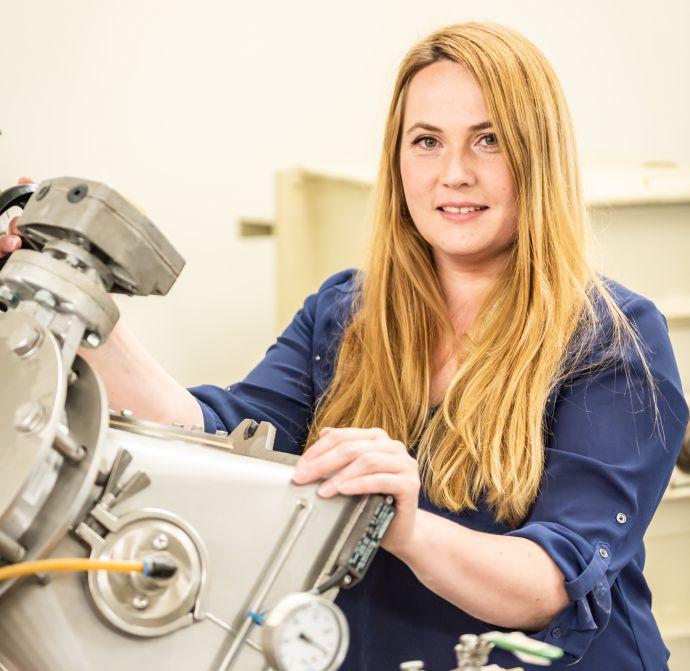

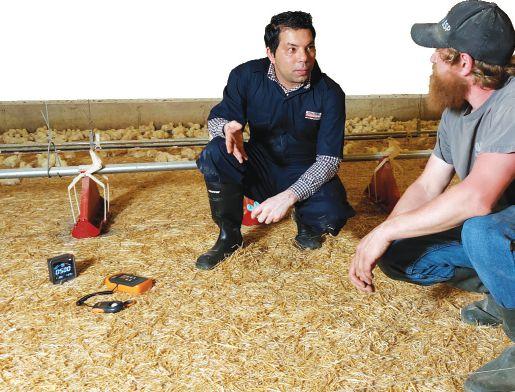

Elijah Kiarie, associate professor of monogastric nutrition in the Department of Animal Biosciences at the University of Guelph and holder of the McIntosh Family Professorship in Poultry Nutrition, and Lisa Hodgins, monogastric nutrition manager at New-Life Mills, led the research that evaluated commercially available gut health programs for broilers to gain a better understanding of what impacts they have on birds.

“So many feed additives claim to have health benefits, but when you go to industry, everyone has a lot of questions. Generally, we only test one additive at a time, but producers will often use them in combination,” Kiarie explains. “So, we want to know how they interact, how can we help industry navigate these changes

and is the feed we are providing viable.”

“Commercial nutritionists like me are challenged to create gut health management programs that use less or no antibiotics – and gut health programs are even more important now,” Hodgins adds.

“So, we were looking to benchmark growth and performance of birds reared on commercial gut health programs, and measure their performance, gut physiology, plasma biochemical profiles, and bone attributes.”

As part of the project, the research team evaluated three commercial gut health programs that represent most of Canada’s poultry production: conventional; raised without medically important antibiotics (RWMIA); and raised without antibiotics

(RWA).

In the conventional program, some use of antibiotics designated as medically important to human health is allowed.

The RWMIA program allows no use of medically important antibiotics and the RWA program allows no use of antibiotics of any kind.

The first significant trial of the three gut health programs was carried out on nine commercial broiler farms in Ontario, starting in May 2019 and continuing to June 2020. Three commercial farms were assigned to each gut health program and each farm was followed for six consecutive flocks. In total, 1.15 million birds on commercial farms were part of the project.

The same three programs were evaluated in a research setting at the Ontario Poultry Research Centre at the University

of Guelph’s Arkell Research Station from late March to May 2020. Here, 2,304 male and female birds were followed from placement to day 42.

In both the commercial and research settings, birds were fed commercially available three-phase feed programs for starter (0 to 14 days), grower (15 to 28 days) and finisher (day 29 to slaughter) periods. Diets for RWMIA and RWA flocks were supplemented with butyric acid and a bacillus-based probiotic, and RWA diets also contained fumaric acid, dehydrated yeast, yeast products, thymol, eugenol and vanillin.

“All three programs used enzymes and products that are commercially available and would be used by feed companies,” Hodgins notes.

The researchers observed some differences in breast attributes, plasma metabolites and gastrointestinal responses. But, overall, birds on all programs showed similar performance. This illustrates that gut health programs are effective at maintaining bird performance and that any identified differences did not impact that performance.

“The bottom line for producers is that you can go into production without antibiotics,” Kiarie says. “The alternatives work if you want to make that transition.”

What’s important though, is that producers think not just about the additives but the entire diet, including the sources of any nutrients or the quality and type of feed ingredients that are used. And when antibiotics are removed as a tool, farm management also becomes a critical factor in the success equation.

Antibiotic use reductions and restrictions will continue, so producers should consider using complementary strategies in their search for alternatives. This is best done by producers working in tandem with their processor, nutritionist, hatchery representative and veterinarian to pick the best program for their particular farm, recommends Hodgins.

According to Kiarie, this is also where applied industry research with farmer involvement is critical to helping find and expand solutions. True commercial farm conditions can’t be properly replicated in a research setting, for example, and stresses flocks are exposed to in these two situations are different in each setting.

“This was a very unique aspect of this project. Lisa has proven that farmers can be partners in research – the cost of this project was not really different from any other research even though it was much bigger with respect to the number of birds involved,” he says. “We would like to see more of this and will continue to pursue these kinds of opportunities.”

Further research needed

The rations used in these trials were cornbased and with antibiotic restrictions ap -

plying to all producers across the country, there is a need for more research focused on wheat as an ingredient.

As well, Hodgins believes, future research should also investigate gut health programs using animal proteins, fats and blood meal, and vitamins coated in gelatin – all of which are restricted under RWA programs currently.

“If we can’t use these products in rations, how will we use them in the future? Will they go into landfill, for example?” she asks. “There is also the sustainability question to consider here.”

The research project was funded by the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance (formerly the University of Guelph – Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs partnership), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Centre Discovery Program.

By Jane Robinson

Not all micronutrients are created equal when it comes to layer diets. The mineral source, inorganic or organic, impacts the availability of the nutrients to laying hens. Trouw Nutrition, that includes the Shur-Grain brand in Canada, has completed a new research study to evaluate the impact of adjusting mineral sources on layer performance.

“We wanted to see if we could move the needle a little on mineral nutrition in layers, and maybe egg shell quality, by adjusting the combination and sources of some of our micronutrients,” says Mark Malpass, director of technology application for poultry with Trouw.

Malpass points to the fact that research has already clearly demonstrated that the source of trace minerals impacts how “available” they are for layers to access from the diet. On a spectrum, inorganic sources of minerals like copper, zinc and manganese are the least bioavailable for birds. Minerals that are hydroxy based are midway and more bioavailable. And organic sources are the most bioavailable, and the most expensive.

“We have a good offering of micronutrients in our layer premixes that balance performance and producer returns, but we always want to challenge ourselves about how we can use these ingredients differently or combine them in slightly different ways to be more effective.”

Trouw recently completed a 40-week trial at its layer validation farm in Ontario to see if adjusting the mix of some of the trace minerals – and combinations of in-

organic and organic sources – would improve layer performance. “Our validation farms provide a real-world commercial style setting where we can conduct scientific research,” Malpass says.

Using 12,000 Dekalb layers, they compared their standard feeding program that already contains a mid-level of bioavailable copper and zinc, to a diet with more bioavailable, organic trace mineral sources of zinc and manganese.

“What we found is that the partial replacement of inorganic trace minerals with more bioavailable sources led to better productivity and a higher return on producer investment,” Malpass says. “And we’re now looking for opportunities to implement these micronutrient changes to commercial feeds across Canada.”

The partial replacement of zinc and manganese with more bioavailable sources, combined with a reduction in overall levels of levels of copper and manganese, resulted in: lower bird mortality; higher average daily egg production

and egg mass; higher revenue and profit; and no difference in feed costs per bird. These productivity improvements were achieved without impacting feed efficiency, indicating that layers were more productive because they were able to use the micronutrients more efficiently.

So, more isn’t always better. “We are always trying to balance the use of micronutrients,” he says. “Adding more isn’t necessarily the goal, it’s about the optimum mix that improves bird performance and producer ROI.”

The research also evaluated the impact of micronutrient adjustments on shell quality – including shell thickness, breaking strength and egg yolk height. Surprisingly to Malpass, the switch to more organic, available nutrients didn’t alter shell quality.

“I think what this part of the research confirms for us is that we are already doing pretty well with providing premixes that optimize shell quality for layers that include a mid range of bioavailable minerals,” Malpass says.

By Leonel Mejia

Since the onset of commercial broiler production several decades ago, the industry has made rapid progress resolving hot weather situations, but ventilation issues for cold weather remain. Technologies such as evaporative cooling, high-efficiency fans, and tunnel ventilation have made the summer months manageable for many companies. However, some still seem to struggle during the winter months where the costs of fuel, litter, and housing make good cold-temperature performance a real challenge.

There have been some great improvements for winter housing, including insulated solid sidewalls, stir fans, controllers, and litter amendments, yet adequate heating, moisture removal, and fresh air often become a challenge in the winter.

Due to typically moist conditions within the chicken house during the winter, gut

health can be affected by coccidiosis and enteric bacterial and viral challenges. In many cases, the nutritionist will attempt to make adjustments to feed formulation to help maintain performance, make floors drier, and improve foot quality. The feed formulation adjustments can assist performance in cold weather, but it is not as powerful as providing good heat and air. The nutritionist, husbandry manager, and veterinarian must work together to keep performance from slipping during the cold part of the year.

Typically, one of the first changes by a nutritionist in cold weather is to reduce the sodium in feed. It is well documented that lower sodium can reduce water intake and, in turn, water excretion and litter moisture. Adjusting electrolyte balance in the winter will need to be driven by footpad quality goals and the welfare

and economics of footpad dermatitis versus overall production benefits.

Research indicates a minimum requirement for sodium to achieve optimal growth and FCR. But this level of sodium may be higher than that desired for optimal litter moisture control and footpad quality. In other words, your priorities should dictate how low you go in cold weather.

Some early work showed that lower sodium levels resulted in lower litter moisture. A minimum of 0.19 per cent was needed in early diets and 0.15 per cent in later diets to maximize growth and FCR. Recognizing that every situation is different, it is important not to overreact to cold weather by dropping salt levels beyond what is optimal for good performance and health and welfare.

Other research has shown that using lower calcium and phosphorus levels in cold weather will decrease fecal and litter moisture. Again, lower minerals will re-

sult in lower water intake, but too much of a decrease can impact performance.

For several years, Cobb-Vantress has demonstrated that raising the amino acid levels, even above recommended levels, will support better FCR, higher growth rates, and higher breast meat yields. Amino acid density then becomes a matter of setting economic priorities.

Higher crude protein diets will result in higher water intake, more water excretion, and higher deposition of nitrogen in the litter. Therefore, if managers are unable to accommodate the moisture and ammonia load from feeding higher crude protein diets, they should use low crude protein feeds. Similarly, some work demonstrated that reducing crude protein and supplementing feed with higher levels of crystalline amino acids also reduces nitrogen excretion and decreased gut disorders.

In fact, my own experiences have indicated that slightly lower protein feeds seem to reduce gut insults, especially during cold weather. The reduced metabol-

26%

ic heat (produced from digestion) inherent in lowering crude protein levels will place more pressure on providing adequate facility heat.

Several nutritionists have observed performance improvements and better litter conditions when they replaced a portion of the soybean meal with a reliable animal protein. In cold weather, this becomes a useful tool as the non-starch polysaccharides and high potassium levels in the soy meal can stress the intestinal tract.

Generally, if the soybean meal can be reduced in a broiler feed from 31 per cent to 26 per cent using animal protein and all amino acids balanced, performance can be maintained and litter can be drier.

Comparisons have been made between corn- and soy-fed broilers and broilers with a percentage of substituted poultry meal. The corn and soy group used soya oil as the liquid fat source, while the animal protein group used poultry fat. In one study, the animal protein group had the same performance results as the

all-vegetable group but had significantly less water intake and excreta moisture.

When examining the diets, it could be argued that a key difference was the lower potassium levels in the animal protein feed. Even all-vegetable producers will substitute lower potassium protein sources such as canola meal, sunflower meal, and dried distiller’s grains as a partial replacement for soybean meal. Therefore, protein substitution reveals another tool to help combat poor litter conditions in cold weather while maintaining good performance.

I have observed that FCR deteriorates when daily temperatures fall below 50°F (10°C). In many cases, producers will restrict fuel consumption by turning off brooders and furnaces, forcing bird body heat to keep the house at or around thermoneutral (70°F/21.1°C). The introduction of fresh air is then limited as efforts are made to maintain temperatures inside the house.

As bird heat is transferred from inside the house to outside the house via simple thermal transfer or through minimum ventilation, the sole source of energy in many instances is feed. With no other background source of heat, the birds will consume more feed in an effort to keep comfortable. However, I have recently seen cases when heat is generated, even in older flocks, that good FCR is maintained.

One example in the Northeast USA is the use of attic vents where sun-warmed air is pulled into the house after being stored in the house’s attic plenum. Farms

that have mastered this supplemental heating method have improved FCR, a reduction in fuel expense, and drier litter. Another system observed in Western Europe involved a direct fire boiler system using straw. The boiler was connected to a heat exchanger, which delivered warm air to the entire house. Such systems can work off multiple raw materials, including straw, wood, or cellulose pellets.

Farms with this system have shown better performance and less pododermatitis. The common theme is supplying heat — not relying on the bird-generated heat during cold weather. In both examples, more air was moved as thermostat-triggered fans cycled more often.

Even with a pure heating fuel such as propane, it is still less expensive to heat with propane than with feed consumption. For example, consider that 1 liter of propane costs $0.66 and generates 24,024 BTUs, or 6,054 kcal. In simple terms, the cost of the propane becomes $0.11 per 1,000 kcal.

Conversely, a grower feed costing $400 per ton ($0.40 per kilogram) with 3,130 kcal per kilogram of feed will cost $0.1278 per 1,000 kcal. However, based on a host of information on metabolizable energy partitioning, feed is at best 40 per cent efficient at generating body heat, so the new calculation is $0.1278

divided by 0.40, equaling $0.32 per 1,000 kcal.

This is strictly a cost of energy comparison and does not account for the expense of moisture and nitrogen removal resulting from poorer feed conversion. Another way to view this is to consider the loss of 5 points of FCR during cold weather on a 2 kilogram bird. This is an additional 100 grams of feed consumed per bird, 313 additional kcal, or $0.10 USD in added feed cost. Had propane been used to provide the 313 calories, the cost would have been $0.0344 per bird USD.

In the poultry industry, those paying for feed (companies) are typically different from those paying for fuel (farmers). Fuel allowances have been administered with varying successes across the industry to

our industry, we need to continue to work on this concept.

Some nutritionists will increase dietary energy (not protein) during cold weather to maintain constant feed intake, growth, and FCR.

This is costly but most certainly less costly than allowing FCR to increase. In theory, extra calories offset bird heat lost to the environment without creating added intake in protein and minerals.

It has been observed that higher energy feed results in less water intake, most likely due to lower feed intake. Other nutritionists have noted that raising feed energy levels during cold weather did not alleviate lower performance. It may be prudent to evaluate feed energy adjustments on a few flocks before instituting this change.

There have been some feed or water additives that have reduced fecal moisture. These include bentonite, turmeric, yucca extracts, and betaine. Not to discount these, but attempts should be made to control the house environment through management and basic nutrition without resorting to the expense of additives.

There are times, however, when the nutritionist must try some of these products. Maintaining cold weather performance can be challenging and can be accomplished with an integrated approach by the housing manager, farmer, veterinarian, and nutritionist spending time on the farms evaluating and discussing the best options.

Dr. Leonel Mejia is an associate technical director within (CAMEX)

New research to assess overall impact of feeding poultry black soldier fly larvae. Meanwhile, progress on breeding.

By Treena Hein

Use of insects as a food source for commercial poultry is well underway in North America, Europe and Australia. Insects are a natural food source for birds and many other animals and the sustainability of using insects like black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) in feed is high. BSFL are very efficient feed converters – and they are fed food waste that would have gone to the landfill site. Their production, therefore, requires no dedicated crop production.

The first layer farm in Canada to include BSFL in its ration was Lockwood Farms on Vancouver Island. They won the Outstanding Young Farmers Award for B.C. in 2019 for this and other innovations such as generating all electricity needed with on-farm solar production.

Their eggs are branded as EcoEggs and sold in specialty retail stores and restaurants in the Victoria area. “We produce about 5,800 a day and the retail price is in line with organic eggs, generally about $7.50 for a dozen large,” farm co-owner Cammy Lockwood says. “We tend to get more medium eggs than large. We’ve noticed feather coverage is better and for longer in the life of the hens.”

They’ve been using BSFL from B.C.-based Enterra, but due to supply and cost issues, including high cost of transportation, they

are looking into producing their own.

Enterra began BSFL production in 2007 using pre-consumer waste food collected from farms, grocery stores and food processing. The larvae are dried and processed into three products: EnterraGrubs (whole BSFL); EnterraProtein; and EnterraOil.

In terms of just how much the sustainability of BSFL exceeds other conventional poultry feed ingredients such as grains, new research is about to provide greater insight.

Daniela Dominguez, a master’s student at University of British Columbia under the supervision of Nathan Pelletier (and

part of the Food System PRISM Lab), is currently doing a life cycle assessment (LCA) of using black soldier flies to feed laying hens. She recently presented her project at the Canadian Poultry Research Forum.

The scope of Dominiguez’s study is cradle-to-farmgate, including the production and processing of the BSFL, the production of the insect-based feed and its distribution to and use on egg farms.

Dominguez is working with data from EnviroFlight, a U.S.based BSFL firm. Using this producer as a case study, Dominguez is currently building LCA models, which will

enable her to identify hotspots and evaluate opportunities to improve the environmental performance of BSFL through energy-efficiency measures and assess the use of BSFL meal in the context of sustainable feed formulation.

“I will be comparing BSFL meal to conventional feed ingredients,” she says, “in order to identify the potential to reduce the environmental impacts of egg production by using BSFL as a feed input.”

In terms of potential opportunities in energy efficiency that would further improve the sustainability of BSFL, Dominguez says that the breeding and processing of

BSFL are the stages with the highest environmental burdens due to electricity and natural gas required.

“Therefore, I will first compare the pilot and commercial facilities to determine if a larger scale of production represents an improvement in efficiency and to understand the extent to which efficiencies have already evolved in the EnviroFlight facilities,” she explains.

of production to meet the rising demands for proteins in the feed and food industries under limited resources.”

“Next, using the commercial scale facility as the baseline, I will model and assess different scenarios to determine the possibility of optimizing energy efficiency at key process stages. For example, by implementing different technologies such as new drying processors or heat recovery ventilators, as well as by using renewable energy sources.”

Dominguez says the diet of the BSFL is also an important element in the production system regarding environmental impact (as well as nutritional profile).

To address this aspect, she will also be looking at the use of food waste and processing by-products as well as other rearing substrates.

In July, collaborators Hendrix Genetics and Protix shared exciting news about BSFL sustainability when they announced major breeding progress. They recently published results of a two-year breeding selection project in the journal Frontiers in Genetics that shows heavier larvae with more protein and fat harvested per crate.

Hendrix has stated that it conducted this research because of the exponential growth in BSFL farming and “a need to further improve the efficiency

The team selected for body weight and that genetic line was compared to a base population line over six experimental rounds under different environmental conditions. Under automated production settings, an average increase of over 39 per cent in larval weight was achieved, along with a 34 per cent increase in wet crate yield, 26 per cent in dry matter crate yield, 32 per cent in crude protein per crate and 21 per cent crude fat per crate.

Noting that exploring potential changes in genetics as a sustainability factor is outside the scope of her current research, Dominguez does believe that genetics could play an important role in the sustainability of BSFL and other types of insect farming if it improves the feed conversion ratio, reduces mortalities rates, or otherwise contributes to improved efficiencies.

“Certainly, improved genetics have been a key lever in reducing environmental impacts in other animal production contexts,” she says.

Dominguez says that BSF has the potential to become a sustainable input for poultry feed due to its high nutritional qualities and its capacity to convert bio-waste into valuable products. Still, she adds that the potential net benefits will be highly dependent on numerous factors.

“Overall, I think that there is a lot of potential here, but that a lot of research as well as technological innovation and maturation will be necessary before we can draw conclusions.”

By Jane Robinson

As laying hens convert to open-concept housing, with more opportunities to move, the question of how they respond to fearful situations may factor into the choice of aviary rearing style. New research at the University of Guelph evaluated how different aviary rearing styles, as well as genetic strain, feed into fearfulness in pullets.

“Research has already discovered that birds reared in cages are more fearful than those reared in aviary housing – those from cages tend to freeze in the face of fear, and birds from aviaries tend to flee,” says Dr. Tina Widowski, Egg Farmers of Canada Chair in Poultry Welfare at the University of Guelph.

What wasn’t known was if there is a difference in fear response for birds raised in the different styles of aviary housing used in Canada. The styles differ in the level of complexity – number of platforms and perches – offered to young birds. Widowski and her PhD graduate student

Ana Rentsch led a new research project, the first to evaluate fearfulness in pullets raised in different styles of aviaries.

When birds are exposed to new, unfamiliar situations – spaces and objects – there is an increased risk of injury if they flee or if there is mass panic in open-style housing that could lead to piling or smothering. All these reactions can have economic and welfare implications for the birds and for producers.

“Fear is very subjective and tough to measure, so we look at how the birds respond and their behaviours when presented with potentially frightening situations,” Rentsch says.

The research involved exposing pullets to situations that may cause fear and observing their behaviour. Rentsch compared the response in pullets raised in three aviary styles that offering varying degrees of complexity, including the number of perches, levels and ramps

available to the birds.

“The styles ranged from very simple to very complex where chicks had the full run of the space from day one with multiple platforms and perches,” Rentsch says. “We also included conventional pullet rearing cages for comparison with the bare minimum of complexity.”

Birds were presented with situations similar to what they would experience in a normal rearing environment, especially in aviary housing, that included a new space and new objects introduced within that space.

Two birds from each different rearing aviary, as well as from caged-rearing, were placed at the edge of a new circular space at 14 weeks of age. Rentsch noted how much they explored the space and how long it took them to move to the centre. “We presume that if birds explore a lot they are likely less fearful because they feel comfortable in the space,” Rentsch says.

“And as a prey animal always on alert about potential predators, the faster birds moved into the centre (more exposed area of the space) the less fearful we assume they are.” Behaviour and response of brown-feathered and white-feathered birds was also measured.

Rentsch recorded other types of behaviour in the space to gauge how agitated the birds were, including exhibiting an outstretched neck or escape attempts.

After a few minutes in this new space, an object was lowered from the ceiling into the centre of the space, and again, response was measured based on the style of housing and feather colour. They looked at whether the birds moved away (walking, jumping or flying) to avoid the object, or if they stayed put.

Staying calm amid complexity

As expected, birds in all three aviary styles were calmer than birds raised in conventional cages.

When the object was introduced to cage-reared birds, they didn’t move the entire time they were observed. “This probably means they were frozen in fear,” Rentsch says. “While the birds in aviaries approached and investigated the object which leads us to believe they were less fearful.”

The researchers did find some interesting difference in fearfulness between the three styles of aviary housing.

Based on the fact that aviary-raised birds tend to be more reactive and fly away more than conventional cage-raised birds, they actually found birds raised in the most complex aviary style were less likely to have a flight response when faced with a potentially fearful situation.

“Birds in the low and medium complexity aviaries were very reactive at first with the object, and then recovered quickly,” Rentsch says. “While the birds in the most complex aviary did not react at all. They stayed where they were when the object was lowered into the space and then approached it and investigated it.”

Birds reared in highly complex aviaries appear to be calmer in the face of

fear, and Rentsch and Widowski are the first researchers to show these differences in fearfulness between the different aviary housing styles.

“We also found that white-feathered and brown-feathered birds reacted differ-

ently,” Rentsch says. “We can’t say that one is more fearful, they just have different responses.” Brown birds were more agitated in the new space.

And when the object appeared, white birds were more likely to flee from it while

MALE

SYSTEMS OPERATE AT DIFFERENT HEIGHTS TO PROMOTE EFFICIENT NO-SPILL DRINKING

FEMALE

HEADS UP DRINKING™ takes into account what broiler breeders have to do in order to drink - namely, lift their heads and let gravity do its work.

By incorporating gender specific drinker lines and gender specific Big Z Drinkers, water spillage is eliminated as the drinkers are positioned at the proper height for both males and females. The advantage with no-spill drinking is a healthy, ammonia free and a more productive breeder environment.

Benefits of Ziggity’s Broiler Breeder Concept include:

• Dramatically improved male uniformity, livability and performance

• Dry slats and litter means virtually no ammonia release

• Improved bird welfare

• More hatching eggs and improved hatchability

• No bacteria-laden catch cups

The Poultry Watering Specialists

Learn more about Ziggity’s exclusive HEADS-UP™ breeder watering system at ziggity.com/HeadsUp

brown birds had a more stationary, stay-put response.

Take home messages

“We know birds need to be smart, calm and physically fit to manage in aviary housing systems,” Widowski says. “And when they are young, they need to be prepared because there are a lot of challenges. This work has demonstrated the importance, once again, of rearing pullets in environment that will prepare them for a long, healthy productive life.”

From Rentsch’s perspective, she has a few take home messages for producers about fearfulness.

• Be aware of the differences

“We know birds need to be smart, calm and physically fit to manage in aviary housing systems.”

between white- and brown-feathered birds when it comes to fear responses and reactivity, especially if you are considering switching genetics.

• Choose an aviary rearing style that works for your management and staff. More complex aviaries that provide more freedom for the birds, also require more management.

• Talk to other producers who

are already using various rearing styles to find out about their experiences.

• Don’t avoid providing the birds with novel objects (extra enrichments) and experiences during rearing. It’s important to expose birds to potentially frightening situations so they become familiar and more robust as adults.

This research is funded by the Canadian Poultry Research

Council as part of the Poultry Science Cluster which is supported by Agriculture and AgriFood Canada as part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. Additional funding was received from Egg Farmers of Canada, Egg Farmers of Alberta and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) through the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance.

Location Saint-Ours, Que.

Sector

Layers and pullets

The business

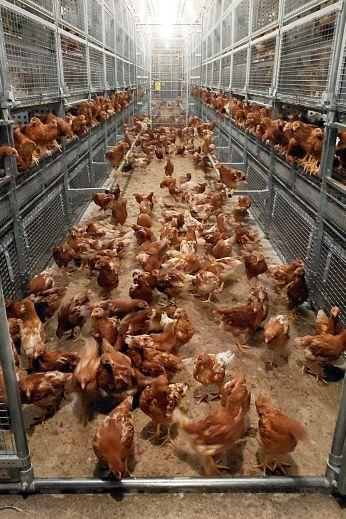

Ferme St.-Ours inc, owned and operated by the Bourgeois-Lefebvre-Laperle family, has been in the egg production business since 1993. They currently have 200,000 free-run layers in Quebec, 76,000 of which are in organic production.

The need

In 2015, the producers saw an opportunity to get into aviary production. “There was a growing need for this,” notes David Lefebvre, head of operations and project manager. Thus, they started to convert their conventional barns to aviaries that year. In 2020, they hit a milestone – that’s when they replaced their last two original conventional barns with free-run systems. They now have six aviary layer barns and three pullet barns with aviary rearing systems. A fourth is on the way this year.

The barn

The producers worked with Hellman on all their barn conversions. For the two most recent projects, which are used for organic production, they went with Aviary Pro 11 systems. Each facility has a capacity for 10,000 layers in organic production and 18,000 in standard production if they ever choose to go that route. Windows provide natural lighting and the birds typically have access to an outside yard except during avian influenza outbreaks. A trained engineer, Lefebvre designed the barns’ ventilation systems. They include tunnel ventilation and heat exchangers for energy efficiency. For more, see the photos and descriptions to the right.

• self-training from day 1

• easy-to-operate

• excellent monitoring

• smooth transition to aviary laying system

Western Canada

Greg Olson

Tel: +1 (306) 260 8081

Ontario

Clarence Martin

Tel: +1 (519) 669 2225

Danny Gilbert

Tel: +1 (506) 470 7370

Manitoba Calvin Hiebert

Tel: +1 (204) 346 3584

+1 (519) 777 1495

British

Dave Coburn Tel: +1 (778) 245 2765

+1 (519) 348 8483

Chouinard Tel: +1 (450) 266 9604

YOU HAVE AN INSTINCT TO PROTECT. WE HAVE AN INSTINCT TO PROTECT FAST.

Introducing Poulvac® Procerta™ HVT-IBD. Timing is everything in a poultry operation, and Zoetis created its newest vector vaccine to put time back on your side. Backed by the latest science resulting in excellent overall protection, studies found that Poulvac Procerta HVT-IBD protected chickens fast against classic and important variant IBD strains.1-3 It’s a quick way to full protection from infectious bursal disease. Contact your Zoetis representative.