March/April 2023

March/April 2023

Our March/April issue is now focused on soil and water quality, and the role that nutrient management plays in both. 12 16 22

Heavy equipment can be a factor in compaction. See page 18. Photo by Stefanie Croley

The latest on the future of manure as a renewable fuel, and what hurdles remain.

BY RICHARD KAMCHEN

Understanding the behavior of phosphorus and potassium in soil, and why precise testing is important.

BY ROBYN ROSTE

Grazing vs. housing

Grazing is popular for consumers, but a "hybrid model" could be better for nutrient loss.

BY RONDA PAYNE

Odds are you haven’t worked a day in your life if you haven’t heard the refrain "there’s riches in niches" (a phrase which, for what it's worth, has varying impact depending on how you pronounce "niches"). This is especially true for those who haul, handle and apply manure for a living – it’s a niche, yes, but there are bountiful residual benefits. You make an honest living and you help growers achieve a better crop.

In previous years, the March/April issue followed the theme of “whole farm management.” After all, the management and application of animal nutrients connects to the whole farm – livestock diet and housing, barn enhancements and more.

However, every few years it helps to review what you’re covering and focusing on in your magazines. And for us, adding a new, more specific theme to our line-up – soil and water health – is a way of acknowledging just how much one needs to know to excel in the niche of manure management.

After all, manure applicators are

However, that does not mean that manure is a miracle amendment that can be applied indiscriminately with perfect results each time. According to the Livestock and Poultry Environmental Learning Community (LPELC), while current literature and research shows the effects of manure on soil health properties, results of these studies can still be mixed because of the variability of manure, soils and other practices. What affects soil health properties in Pennsylvania might not have the same effects in Texas. Rates, timing, amounts and other factors all must factor in to ensure not only the health of your crop but also the health of your surroundings.

Besides the manure itself, the equipment with which you apply it can also have long-term implications on the health of one’s soil. Compaction, explored on page 18, is an issue that can feel almost unavoidable for farmers. How can one spread the nutrients their crops clearly need while mitigating the damage to their land?

"What affects soil health in Pennsylvania might not in Texas."

now tasked with knowing much more about soil and water health. Given the current economic pressures facing growers, manure can be invaluable as a soil amendment – not just because of its cost-effectiveness, but because of its specific benefits for the environment and yields. It can help increase organic matter levels in the soil, which bolsters earthworm activity. Overall, manure is a net positive for soil.

On page 22, we explore the effects of housing vs. grazing on nutrient loss, and why the issue is not (like some cows) black and white. And on page 16, Robyn Roste takes a look at P and K fixation in soil – myths, misconceptions and more.

The thematic flip of our magazine is an acknowledgement that manure applicators are stewards of the land and true masters of their niches. •

Power. Performance. Comfort. Without the cost. That’s the Kubota M7-2 Rancher Edition. Built to handle the toughest jobs, the M7-2’s load sensing (CCLS) hydraulics allow you to run a variety of implements and gives you wide-ranging versatility to handle all your jobs. Work comfortably from the roomy cab with a built-in radio and comfortable seats. Plus, you can add a front loader with an impressive lift capacity of 5776 lbs. The M7-2 certainly earns its “Rancher” title.

kubota.ca | MM_Kubota_MarApr23_CSA.indd 1

The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) has committed to another Manure Mondays webinar series, running this winter and early spring.

First launched in late 2021 in partnership with Manure Manager following the first-ever virtual North American Manure Expo, Manure Mondays is an educational initiative delivered through weekly webinars. Although organized by OMAFRA, this year’s

presenters will also include speakers from Minnesota, Michigan and Pennsylvania. Lessons are meant to be “cross-border” in nature and applicable to manure applicators and producers in all parts of North America.

Following the final Manure Monday presentation on March 13, in which OMAFRA’s Christine Brown will answer common manure questions, all Manure Monday videos will be posted on Manure Manager.

The World Pork Expo will return to the Iowa State Fairgrounds this coming June. Set at the Iowa State Fairgrounds in Des Moines, IA, the World Pork Expo (WPX) is celebrating its 35th year. The event will take place June 7 to 9.

Presented by the National Pork Producers Council (NPCC), this year’s event will mark a major milestone for WPX, which is the world’s largest porkspecific trade show. Pork producers and industry professionals alike will be able to

Delaware’s Nutrient Management Commission has voted to move forward with changes to the state’s nutrient management rules. Changes to these rules tend to only take place once per decade.

The Commission, which is responsible for regulating the use of commercial fertilizers and manure in order to limit grounudwater pollution, voted on a change that would close what it calls a “loophole,” which currently can allow consultants hired by farmers to create nutrient management plans without undergoing phosphorus assessments.

So far, the proposed change has not faced opposition.

celebrate 35 years of WPX through highquality programming, educational seminars and networking opportunities in the pork industry. Participants can also further the conversation online through the hashtag

#35YearsofWPX. According to WPX, the three-day event will host hundreds of exhibitors from North America and beyond. In 2022, 400 companies partook in WPX. An estimated 10,000 pork producers and ag professionals attend WPX every year.

The land and water resources department of Dane County, WI held a meeting in February to gather input about farmer interest in the location for a manure digester or other types of manure handling systems. This would be the third manure digester for the county. The first two, built in 2010 and 2013, operate through a partnership with the county and work with local businesses and farmers to help process and repurpose manure. In 2021, the two digesters processed more than 90 million gallons of manure. Now, the county has allocated $3 million in its annual budget toward a feasibility study for another manure handling site. No site has been selected yet for the potential new digester.

New Holland Agriculture has officially unveiled its T7.300 Long Wheelbase (LWB) tractor with PLM Intelligence to North American users. The new model uses the Horizon Ultra cab and a range of inter-tab technology and features to maximize productivity, efficiency and uptime.

The new model was driven by demand for more power without a larger frame, said Oscar Baroncelli, head of tractors, New Holland. It features an enhanced FPT Industrial NEF 6 engine, which delivers 280 HP maximum power for draft work and 300 HP for PTO and haulage jobs. It also has enhanced processing power and in-cab connectivity through smart technology features.

Bazooka Farmstar has launched an updated Riptide Vertical Pit Pump. The new model has been redesigned to can move high volumes of liquid manure with less maintenance. It is 15 percent more efficient than the original model, allowing it to move up to 5,850 GPM. The improved Riptide features a single eight-inch vertical pipe and a 20.5″ Bazooka Farmstar Submersible Pump.

The Riptide is available with a twopoint hitch, two styles of three-point hitches, and a trailer-mounted version.

The trailer-mounted version includes a folding tongue allows users to move between sites faster, decreases set-up time, and maneuvers more easily.

Fort Equipment has launched the Pipe Bridge, which is designed to straddle a standard two-lane roadway. It boasts a 20’ flat height clearance and 25’ wheelbase. This gives operators more convenience by eliminating the need to hunt down culverts pipes.

The Pipe Bridge is fully self-contained with batteries, 12-volt hydraulic power packs and solar panel chargers.

Call the FAN/BAUER boys: East: Jim Dewitt, 1-630-750-3482, j.dewitt@bauer-at.com

• Midwest: Trey Poteat, 1-219-561-3837, t.poteat@bauer-at.com

West: Jeff Moeggenberg, 1-630-334-1913, j.moeggenberg@bauer-at.com

Sales Director: Ray Francis, 1-219-229-2066, r.francis@bauer-at.com

Parts/Operations: Rob Hultgren, 1-800-922-8375, r.hultgren@bauer-at.com

Visitors to the 2023 EuroTier Show in Germany were able to view for themselves the latest equipment and technology available to handle manure and slurry (liquid manure).

In a special edition of our U.K. Update, we hit the ground at the first in-person EuroTier Show since 2019 to evaluate the latest in manure technology.

BY CHRIS McCULLOUGH

Initially held every two years but cancelled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, EuroTier is widely recognized as the world’s leading trade fair for livestock husbandry.

Around 106,000 visitors from 141 countries attended the event in Hannover, checking out the latest innovations exhibited by 1,800 companies from 57 countries.

Slurry and manure equipment

ABOVE

came in all different sizes, colors and prices, but the general theme throughout the conference was that there is a big move to reduce the emissions from livestock farms produced by waste.

With numerous dribble bar options on many of the stands, farmers were left in no doubt that this type of spreading is the future.

Tankers, too, came in all shapes and sizes with single, tandem and triple axles competing to see which was best at staying above ground.

As always, there was a sold connection between slurry (or “muck”)

The Hanskamp CowToilet collects urine directly from cows, separating it from feces.

machinery and the equipment used to separate, and those used to produce energy.

There was even a machine to sieve manure from bedding – and let’s not forget the growing numner of little robots buzzing around the sheds cleaning up after the cows. A dedicated “robot zone” at the show highlighted how easy these little robotic scrapers can keep a cow barn clean with a number of manufacturers taking part.

With a lack of labor availability becoming a huge problem on livestock farms around the world, using robots is an alternative. But, of course, the cost of such a system will not fit into every farm’s operating budget.

Separating slurry is becoming very popular as farmers begin to realize the benefits. Fliegl’s Tapir 375 combines all the advantages of a mobile separator with those of a large press screw principle. An enlarged sieve with a diameter of 300mm and a length of 750mm enables the intake of up to 35 cubic metres per hour of cattle slurry. The optimised auger inside presses the liquid manure mixture even more strongly against the surrounding sieve and thus achieves an even better pressing result. As a result, the Tapir 375 separates 40 percent more efficiently than conventional standard separators.

Every cubicle house needs a toilet, so Dutch company Hanskamp came up with one for cows. The CowToilet collect urine directly from the source separately from feces, to ensure both nutrients can be optimally used separately. As the urine does not come into contact with the feces, considerably less ammonia is formed. This deals with an ammonia surplus at the source and makes the CowToilet a solution to reduce emissions. The CowToilet uses a natural nerve reflex that causes the cow to urinate. This technique has been automated by Hanskamp and integrated into a specially designed CowToilet cubicle that can be placed in any dairy shed. The urine is collected in the reservoir of the CowToilet and is then pumped out and stored separately.

Using liquid manure to power a tractor is one of the latest crazes to help reduce

dependence on emission-emitting diesel, but the theory has a long way to go. On display was New Holland’s T6 Methane Power, the world’s first 100 percent methane-powered production tractor. Its design has now been enhanced with a six-cylinder, 145hp rated/175hp boosted natural gas engine, which is coupled to the proven Electro Command four-speed semi-powershift transmission. With the same levels of power and torque as its diesel equivalent, owners benefit from up to 30 percent lower running costs. Producing 98 percent less

particulate matter, reducing CO2 emissions by 11 percent and overall emissions by 80 percent when using biomethane near-zero CO2 emissions are achievable.

Moscha exhibited its award-winning lightweight slurry boom, which has a plastic pipe as a supporting construction element. Moscha achieves this by using covered plastic pipes instead of metal, which significantly reduces the weight of the folding boom. The precise spreading

ABOVE

Joskin's Terraflex/2 XXL arable injector allows a better loosening of ground.

of liquid manure close to the ground with a drag hose or drag shoe attached to corresponding boom technology can also be used on lighter trailers requiring less tractive power and on more extensively contoured terrain.

One of the many shed scraping robots in action at EuroTier was the Auto Scraper Spray model from Royal de Boer. This unit is fully programmable in terms of cleaning routes, frequency of cleaning and a progress report. The robotic scraper comes in three versions. The most straightforward one, and also the base unit, is the Auto-Scraper. The Auto-Scraper Pro is more intelligent, and the Auto-Scraper Spray is equipped with a water spray system. The machine follows the sides of the barn and stops when it reaches its charging station. In places where no side guides are available, beams with a height of 8cms should be placed. The scraper robot will initiate its next lap when the next pre-programmed start time begins. The Auto-Scraper robot is available in operating widths of 140, 170 and 200cms.

Joskin’s Terraflex/2 XXL arable injector is made of a galvanised double-beam frame with two rows of Everstrong spring tines with 6.5 centimeters wide shares at their ends. The shape of the tines allows a better loosening of the ground thanks to their vibrating effect, a good mixing of the vegetable residue and a perfect tearing of the plough soil for a better preparation of the seed bed. The wide opening of the shares ensures a very good flow of the slurry and a wide distribution. The distance between the tines is 30cm or 37.5cm, depending on the model, and the distance between the two rows is 70cm. Slurry is usually injected on a 12 to 15cm working depth.

Krampe exhibited its huge RamBody 750 push-off trailer used to transport farmyard manure, poultry manure or crops. This trailer has a strongly built body with a load volume of 41.1 cubic metres. Besides the standard parabolic springs or a running gear with hydraulic axle compensation, Krampe recommends the pneumatic running gear. As a unique selling point, BPW steering axles with overhead brake cylinders are being mounted which

ABOVE

The Krampe RamBody 750 features five hydraulic rams to provide powerful feed force.

guarantee a high ground clearance. The core of this trailer is the push-blade mounted on a following-on table. The narrow designed tunnel in the centre protects the hydraulic rams from damage. A total of five hydraulic rams provide the powerful feed force and offer large reserves also in order to safely empty an overloaded vehicle.

With a working width of 15m, the Fliegl Snake 150 can be used to spread slurry directly connected behind the tractor or attached to self-propelled liquid manure spreaders. This particular model weighs in at 2.55 tonnes, has 60 operational spouts and measures 2.6m wide by 3.8m tall. With the help of the digital flow meter Fliegl Flow Control, a homogeneous spreading result can be achieved on the ground. It is equipped with the Fliegl screw distributor and has a drip stop bonus at the headland thanks to hydraulic folding.

Pulled by a tractor, the BeddingCleaner cleans the bedding from cow barns when required. The bedding material is sieved using a sieve mat. After this the bedding that is not contaminated drops back into the stable. Conversely, a small amount of the bedding material sticks to the settled faeces, with the result that it can be easily collected by the mounting and transported into the integrated storage bunker. Bedding material subsequently remains cleaner and drier, and can be used for longer periods. •

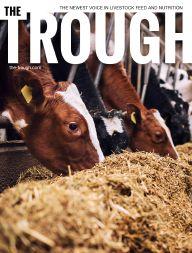

Manure Manager parent company Annex Business Media has launched a new media brand dedicated fully to livestock feed, nutrition and additives. The Trough delivers content to those in the livestock business including producers and breeders, grain farmers, veterinarians and animal nutritionists, distributors, processors, elevator operators and other key industry stakeholders. Content will be delivered through print issues, online news, eNewsletters, webinars and podcasts. Focusing on Canadian and U.S. markets, The Trough will produce content that targets producers of cattle, swine, poultry, ruminants, equine and other animals.

The launch comes at a time when Canada’s markets for both livestock and animal feed are growing. Higher cattle prices are forecast in Canada and the U.S. for the next year, while farm cash receipts of dairy products in Canada have grown consistently. The animal feed and grain market (including pet food) in Canada is estimated to be $12.1 billion as of 2021, and growing

at an annualized rate of 4.3 per cent.

“This growing industry is filled with many unique challenges and opportunities as more consumers want to know what the food they eat is eating,” says Bree Rody, editor of The Trough. “The feed decisions one makes for their animals influences animal health, marketability and even the environment. Our goal is to provide content that balances business issues, research and innovation to guide businesses through their everyday decision-making.”

“The launch of The Trough comes during a time where the demand for succession and sustainability is prevalent, while asking more of our land, animals and labour resources than ever before. The need to make strong input & feed decisions is indisputable,” says Michelle Bertholet, Group Publisher of Agriculture. “The absence of a media brand in this niche that reached across North America allowed for a modern approach to finding a balance between science and business, and that’s our goal."

Manure as a form of renewable energy is moving beyond niches.

BY RICHARD KAMCHEN

Anaerobic digesters are more common in ag, but there are enhancements yet to come.

A regular reader of Manure Manager knows better than to consider manure a waste. Manure has proven itself time and time again as anything but by regenerating soils and improving crop yields.

More so, researchers are endeavouring to prove its growing value as a source of sustainable energy.

“There’s always been a lot of interest in sustainable fuels, but more recently, given carbon programs and a greater focus on reducing agriculture’s and humanity’s impacts on carbon and the environment, I think opportunities have really taken off,” says Daniel Andersen, who specializes in manure management at Iowa State University (ISU).

As anaerobic digestion and alternatively fueled vehicles expand from niche novelties to widely adopted innovations, here’s a status report on advances in manure as alternative fuels.

How manure fits in as a source of renewable fuel is through anaerobic digestion.

During this natural process, microorganisms break down biomatter and produce biogas – a combination of methane and carbon dioxide.

Anaerobic digesters – such as municipal digesters or on-farm digesters – tend to nab a lot of the spotlight. But Andersen says anaerobic digestion occurs in all situations, to some degree. “No matter how we’re storing our manures, some amount of anaerobic digestion will occur,” explains Andersen. But unless captured, both methane and CO2 go

A $10 million, five-year grant awarded to Iowa State University in 2020 will power the Consortium for Cultivating Human and Natural regenerative Enterprise (C-CHANGE).

into the atmosphere. Methane’s especially problematic, as the potent greenhouse gas has about 28 times the global warming potential of CO2 over the course of 100 years, Andersen says.

Given that, researchers are looking for more sustainable practices by enhancing anaerobic digestion, and capturing the methane that manure produces. In this way, methane, the main component of natural gas, not only is prevented from escaping to the atmosphere, but it isn’t wasted either.

“Improved manure management, improved sustainability of livestock, can make a difference,” says Andersen. “If we can reduce our footprint for producing milk, meat and eggs, while making renewable energy, I think that’s an opportunity that’s pretty exciting.”

In 2020, ISU, Penn State and Roeslein Alternative Energy received a five-year, $10 million federal grant to develop new methods of turning manure and biomass into fuel.

An ISU press release at the time explained that new separation technologies would allow biogas to be upgraded to renewable natural gas, which could then be distributed through a gas pipeline network, similar to how renewable electricity is distributed through an electrical grid.

“We will enhance that methane production by providing the right environment to maximize the microbe growth,” says Andersen. “Those microbes are really what are breaking down that carbon that’s in the

manure, and just increasing the amount of methane that it’s making, capturing that and either combusting it for electricity, or in many cases, cleaning it, taking it to relatively pure methane instead of biogas.”

He notes equipment to clean biogas for electricity is oftentimes less expensive. Although the carbon credits might be less lucrative too, it’s balanced out by the lower capital cost of getting a project going.

Much of the research done on anaerobic digestion goes back to the 1960s and ’70s and the first energy crisis, and then again in the early 2000s, Andersen explains. “As we think about reducing humanity’s carbon footprint on the world, transportation and energy clearly are the drivers.”

Anderson has watched a rapid expansion in the amount of anaerobic digestion facilities throughout the Midwest. In the last year in Iowa alone, there’s been more than a tripling in the number of anaerobic digesters, from four to 13.

“And we’ve seen massive expansion of this technology in states like North Carolina, Oklahoma and Texas,” he adds. “We’re already on the front edge of a lot of implementations, because the carbon credit market is quite lucrative at the moment, from programs like the EPA’s D3 RIN market, as well as low carbon fuel standards that various states out west like California, Washington, Oregon – and even Canada –have implemented in recent years.”

Governmental emphasis on putting

more electric-powered vehicles on the road and new EPA proposals look to be a boon.

The EPA last December proposed a rule to establish required Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) volumes and percentage standards for 2023, 2024 and 2025. The EPA explained its proposed rule included regulatory changes to prescribe how RINs from renewable electricity (eRINs) would be implemented and managed under the RFS program. This would allow parties to register with the EPA and generate eRINs produced from qualifying renewable biomass used as transportation fuel.

“The EPA’s finalizing the rules of how eRIN would work right now, and that would really open up powering electric cars with electricity made from manure,” says Andersen.

He adds, however, that Iowa would have a tough time relying on manure alone to feed its digesters.

“One of the challenges we see here in Iowa is that oftentimes these projects need relatively large farms, probably at least 1,000 dairy cattle, 15 to 20,000 pigs. And while Iowa has lots of animals, our farms tend to not be that big. To help our farms be more competitive in this space, we’re really interested in other biomass materials that we can use to supplement that gas production to reach the scale we need.”

ISU received another grant, this time in 2022, of about $10 million to demonstrate how generating renewable natural gas from cover crops and prairie grass could finically motivate farmers to implement conservation practices that would sequester carbon dioxide and improve water quality.

He says the Midwestern landscape, once mostly prairie, is dominated by corn and soybeans, and that this project aims to find a way to incentivize a return to prairie or crops other than corn and soybeans.

Through both the 2020 and 2022 grant-funded projects, researchers hope to achieve a several goals. “One is to demonstrate a model of what a system could look like to really get water quality, wildlife habitats, and energy production benefits at a reasonable farm scale, where people could see how it would work, and what it might look like on their farm,” says Andersen.

Another is to help manure management become more sustainable, and “to turn rural areas, especially rural Iowa and the Midwest, into an area [with] economic opportunity from the energy production.” •

Partners:

REGISTER NOW FOR DAY-ONE TOURS AND EXPO FAST-PASS TICKET:

DAY ONE – AUGUST 9

8:00 am: Entech Digester Tour

8:00 am & 10:00 am: Arlington Research Station Agronomy Tour

10:00 am: Dairy Facility & Manure Separation Tour

11:00 am: Tradeshow Opens

1:00 pm: Agitation Demo / High Volume Rapid Release Demo

3:00 pm: Safety & Operations Knowledge Tour

DAY TWO – AUGUST 10

8:00 am – 10:00 am: Education Sessions

10:30 am – 11:30 am: Solid Manure Demos

1:00 pm – 2:00 pm: Liquid Tanker Demos

3:00 pm – 4:00 pm: Dragline / High Pressure Hose Break Demos

4:00 pm – 4:30 pm: Spill Response Demo

Education Session Sneak Peek

• Manure emissions during agitation and processing

• Applying fall manure for hybrid rye

• Nitrification inhibitors and manure

• Real-time nutrient sensing for precision manure application

• Biochar and manure management

• Nitrogen mineralization in treated manures

• Manure innovations of the Northeast

• Manure separation systems

• Interaction of cover crops and manure

• Interactive calculator to estimate manure value

BY ROBYN ROSTE

When it comes to soil management, whether you’re a grower applying your own manure or someone hired to spread manure on someone else’s land, there’s a lot to consider.

Finding and maintaining optimal biological, chemical and physical conditions while also minimizing environmental risks is a careful balance in the best of times. And with the ever-rising prices, not to mention market volatility, supply-chain breakdowns and extreme weather fluctuations, there’s a lot of pressure to manage production costs and timelines without impacting yields.

“With what the fertilizer prices are right now, soil and manure tests will help identify where it might be the best target for those acres, if you have flexibility for application,” says Daniel Kaiser, associate professor at the University of Minnesota.

Kaiser has written extensively on crops and nutrient management, and focuses on potassium (K) and phosphorus (P) fixation in the soil.

ABOVE

He says both potassium and phosphorus follow a “diminishing return” for each additional pound of fertilizer applied, so one of the best ways to manage costs is to perform regular soil and manure tests. That way, growers can focus on applying manure to the acres that are deficient, or where they’ll see the best return.

When deciding which manure to apply, the government of Saskatchewan points out that solid and semi-solid manures have higher organic content than liquid, and both solid and liquid manures provide a lower concentration of nutrients compared to commercial fertilizer.

“When using manure as a fertilizer, it is important to understand that only a portion of the manure nutrients are immediately available,” the government says on its website.

The agriculture department of the government of Manitoba released a fact sheet recommending the best way to estimate the nutrient content of manure

It is recommended that optimum sample test results come from testing at the same relative time every year.

is by testing before each application.

“This should be based on well-mixed, representative sample (which can be difficult). Sometimes more than one sample is required to estimate the nutrient concentration because the characteristics of the manure change,” it reads.

The fact sheet also suggested that while field test kits provide immediate estimates, laboratory analysis should also be consulted to indicate total nitrogen, ammonium N, total P, total K and dry matter content.

Soil testing is now widely accepted in agri-business, although Kaiser cautions growers to look at the big picture when analyzing soil and manure data to make manure application decisions, rather than at one individual test.

“Growers tend to switch sampling time and get different results, then panic seeing the soil tests change—particularly when it drops,” he says. “Try to sample at the same relative time during a calendar year.”

A term that often comes up with discussing nutrient management is “fixation.” In an article written for Minnesota Crop News entitled P and K “fixation” in the soil: What you need to know, Kaiser explained how fixation is often misunderstood to mean a nutrient is lost forever once it is fixed, rather than retained by the soil for a period of time before becoming available to the plant once again.

Fixation is normally applied to potassium and ammonium. Both nutrients can fit into pockets of clay and are then released as the soil shrinks and swells. However, phosphorus in the soil forms compounds rather than sitting in air pockets.

“P is not ‘fixed’ in the same sense as K and ammonium. Phosphorus forms compounds in the soil with calcium, iron and aluminum that can be very insoluble, making P in the soil less available for crop uptake,” Kaiser said.

In the article, he added that research from Iowa State University found instances where potassium fertilizer didn’t increase in the soil test, yet there was a yield increase.

“P is retained in a less available form maybe, but you’ll see cycling back and forth,” says Kaiser. “It’s not a one-way door; it’s a dynamic process.” He suggests using the term “retention” instead of “fixation,” for phosphorus, since it can be chemically reactivated in the soil and used by plants at a later date.

At present, the research is showing a natural process of fixation and release for

nutrients retained in the soil. There is not a lot a grower can do to access retained nutrients, other than gaining a better understanding of the chemical reactions happening, and keeping track of the annual cycling process through regular soil samples.

“P tests are more stable overtime while K has a seasonal variation. Monthly samples

vastly different.”

“It comes down to soil testing; how things behave,” says Kaiser. “P tests are more stable over time while K has a seasonal variation. Monthly samples over the growing season can be vastly different fixation—less available forms that tend to impact the soil test itself.”

Kaiser’s research aims to develop better options to determine available phosphorus and potassium for crops, and a stronger

understanding of the nutrients’ dynamics in the soil.

“I have been asked about whether biological products can ‘unlock’ fixed nutrients. The simple answer is that there is nothing out there that can be considered a silver bullet that would allow us to not apply fertilizer. Soils that are low in available nutrients will need fertilizer or manure application to produce a profitable corn crop,” he says.

While most growers don’t need to have deep knowledge of the chemical reactions nutrients have within the soil, it’s important to understand that it’s possible for soil to retain nutrients and then re-release them for plant uptake in future months or years.

That said, Kaiser still recommends using tests to determine how much P and K to add with manure.

“Research has not shown that accounting for some of the larger pools of nutrients in the soil is better than the routine soil tests suggested for use in determining nutrient availability for crops. Routine soil tests are still the best way to determine how much P and K are available to the crop at a given point in time,” he says. •

BY

Heavy equipment can cause soil compaction. How can manure applicators mitigate any damage?

BY BREE RODY

On one hand, compaction in soil is essentially a black-and-white issue. At least, it's black and white in the sense that few would argue that compaction is good. It’s not ideal for crop quality or yield, nor is it ideal for the overall health of a farm’s soil infrastructure. Healthy soils are soils with pores large enough to allow maximum water infiltration and has high water-holding capacity. When the number of moderate to large pores decreases in favor of smaller pores – the result of soil compaction – it can disrupt the movement of air, water, earthworms and other soil micro-organisms.

Alex Barrie, field specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) says this is especially evident in tile-

ABOVE

drained fields. “You go along fields that have been tile-drained, and it works really well, but then [the drainage] gets less and less productive,” he explains. “Part of that can just be that there’s more moisture. But part of it is [compaction] slowly wearing on the efficiency of that subsurface drainage, whether that’s subsurface compaction, or compaction.”

A dataset collected by Ohio State University’s Scott Shearer and extrapolated by the Ontario Soil Crop Improvement Association (OSCIA) in 2016 attempted to calculate the estimated cost of compaction for growers. OSCIA found the data demonstrated a six bu/acre (bushel-per-acre) yield difference from wheel traffic in soils with normal moisture, and a 27 bu/

Multiple spreaders on the field at the North American Manure Expo in Chambersburg, PA in 2022.

acre yield difference from wheel traffic in wet soils. At an estimated CAD $4.50/bu for corn, this would cost close to $50/acre with narrow width spread pattern manure application equipment.

What’s more, the size and weight of equipment has undoubtedly increased. Historical results from the Nebraska Tractor Test Laboratory program shows that tractor weights have increased by, on average, 900 lbs/year for tractors purchased on North American farms.

But, while there’s no grey area concerning the effects of compaction, there is a grey area when it comes to the question: what are growers to do?

For most medium- to large-sized farming operations, heavy equipment moving across a field, whether installing drainage and irrigation systems, spreading pesticides, harvesting crops or spreading manure, is unavoidable. The size and weight of tractors and spreaders has increased in large part because demand for more efficient application is much higher. As commercial manure applicators aim to improve the health and quality of crops and the fields on which they are grown, knowing how to do so while mitigating

damage from compaction makes for a tricky dance.

One of the things Barrie remembers most about the recent summertime field days known as “compaction days” was how much sweat went into the demonstrations. Literally.

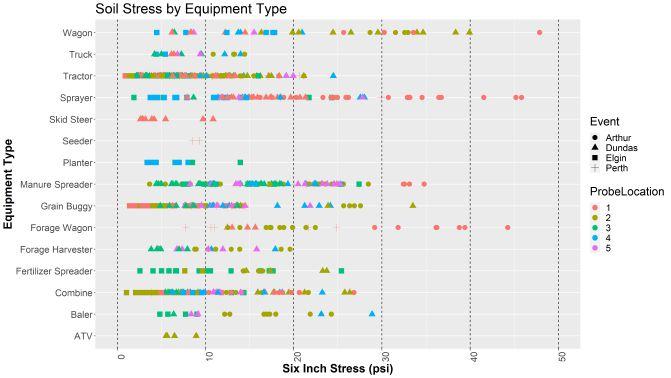

They were long days, says Barrie, in which he and a team of local soil and crop directors gathered at various sits – Arthur, Dundas, Elgin and Perth – to run equipment demonstrations with equipment provided by local farmers and dealerships.

Equipment included heavy-duty pickup trucks, tractors, manure tankers, grain wagons and more. “We bring them in, we load them up as heavy as they’ll ever be in operation and weigh all those tires on all of those vehicles.”

During the running of said vehicles, Barrie and his team had a number of sensors throughout the field. The vehicles were run across dryer and wetter pits in order to test the stress on soil in different conditions. The data points were plotted in real-time thanks to those sensors, resulting

in readings for all types of ag equipment and enabling the field technician to plot their stress (PSI) at both six and 12 inches of soil. More than 540 individual readings were produced at the field days.

In some ways, says Barrie, the results weren’t necessarily telling him anything surprising. At a high level, he says, most farmers know that more weight and more pressure cause more compaction. The demo day, however, gives technicians such as Barrie valuable, tangible data that allows for more specific comparisons. And for farmers and for-hire applicators, it helps them understand the impact at the equipment level.

“What farmers want to see are those specific tires. They don’t really approach it from an engineering perspective. They get to see the different configurations and see the effects on the soil.”

While most agriculture professionals are most familiar with their own equipment and the specific scenarios in which they operate, Barrie says the demonstration day made room for “those hypotheticals.” For example, he said for applicators who always have their tires inflated for road pressure, the crew had the ability to

lower the pressure on the go and demonstrate the benefits.

“We’ll do a high-pressure run and a low-pressure run [of the vehicles] and it’s actually quite shocking. [The audience] will say, ‘wow, that really made a big difference.’”

He said some were also shocked to see that a loaded Ford F150 pickup truck had “just about the same” amount of pressure as a manure spreader in terms of surface stress.

General results from five different probe locations at the Dundas site found that higher-parameter tires caused more soil pressure at the six-inch level.

Manure spreaders, says Barrie, are among the less impactful vehicles for soil pressure. All manure spreaders use radial tires, and tire loads were as low as just over 5,000 lbs and never higher than 20,000 lbs. Tire pressure from these vehicles were generally low-to-medium-low.

The pickup trucks observed were all well under 5,000 lbs for tire load, but had higher tire pressure, with most observed trucks at medium-to-high levels. Tractors, meanwhile, had a much bigger range of weights; at their lowest, tractors’ tire loads were as low as some pickup trucks, but at their highest, they were as heavy as a heavy manure spreader. Tractors with radial and bias tires tended to post lower tire pressure than those with tracks.

By comparison, grain buggies and combines had a much bigger variance in weight and, at their heaviest loads, were much higher (with the heaviest grain buggies higher than 45,000 lbs and the heaviest combines at around 35,000).

For soil stress, manure spreaders resulted in a moderate amount of stress at both six- and 12-inch depths. The highest-recorded amount of stress from a manure spreader at six inches was just under 35 PSI at the first probe location at the Arthur site. That same probe location saw higher stress at six inches from wagons, sprayers and forage wagons. The lowest stress recorded at six inches from a manure spreader was at the second probe location at the Arthur site, at under five PSI.

At 12 inches, manure spreaders topped out at around 23 PSI, once again at the first probe location at the Arthur site. Wagons, sprayers and forage wagons were once again the most impactful at this site. Most manure spreaders’ pressure was recorded at between five and 18 PSI. Results

were also recorded at 20 inches, however most equipment posted lower pressure at 20 inches, with none over 15 PSI save for one wagon recording (second location, Arthur site) and one grain buggy reading (second location, Arthur site).

Barrie notes some limitations in the specific data, because the different sites have different conditions. “The strain rate on the soil is so different from site to site,” he says. “I can’t compare Arthur two years ago to Dundas last year.” He says for this reason, not only must forhire manure applicators be prepared for anything, but landowners also have a certain responsibility when spreading manure or hiring someone to do so. “What they need to do is try to figure out how

strong their soil is in any given sense of conditions, so I can say, ‘well, you can get your tire pressure to a certain limit.’”

Nevertheless, he was able to come out with some central takeaways. He says the forage equipment can be “sneaky” in terms of their pressure. Manure tankers, meanwhile, “have the benefit of being empty a lot of the time, whereas a piece of forage equipment is the same weight all of the time.”

While manure tankers are not among the worst culprits for pressure on soil, Barrie says there are always ways to ensure minimum impact for maximum production. He says it comes down to thinking critically when it comes to purchasing decisions, especially with tires.

“If you’re at a point in time where you need to replace tires on your equipment – and you should already be on radials – consider going to an IF or VF tire,” he says. “They’ll get you lower pressure for the same weight, and IF will get you [even] lower pressure.” He says the industry now favors IF tires, and thus most technology will skew toward IF tires. Either say, says Barrie, spending the money on a better tire is worth it.

Money spent on upgrades is often made back in efficiency, he notes. He says custom operators’ payback is “probably higher” when they use central tire inflation. “You get the benefit of high pressure on the road and low pressure on the field, which saves you a whole whack of fuel. You’re better set up to save fuel in both cases, and the payback is on both fuel savings and tire wear, rather than just the yield benefit from not compacting your soil” • ABOVE

Now manure applicators can cross a road wherever it is convenient to them.

and sets up in a minute, no

For cattle nutrient management, a balance of grazing and housing has its benefits

BY RONDA PAYNE

People may be tired of hearing how creating a better life is all about balance, but for dairy farmers around the world, a new study incorporating existing research and fresh modelling finds that balance really is the key to making everyone happy. The study was designed to find the right mix of dairy cattle housing and/or grazing conditions to reduce the impacts of nutrient losses (particularly nitrogen and phosphorus losses into water sources) while also ensuring financial viability of operations.

Rich McDowell, chief scientist with the New Zealand-based Our

ABOVE

Land and Water National Science Challenge, had seen a report from a colleague, noting New Zealand dairy farms have the lowest carbon footprint. He wanted to know if the same applied to nutrient losses. He and a team found 156 existing studies from around the globe to allow them to compare and contrast the various systems from year-round grazing to year-round indoor, barn-living and the associated nutrient losses.

“This was partly a literature study that used published and validated data,” he says. “There was no direct interaction with farmers, although

Rich McDowell’s research found that a balance between housing and grazing can improve the health of livestock cattle while minimizing nutrients lost in manure.

each of the authors regularly do, do that.”

The authors of the study couldn’t rely on the existing literature alone as dairy farm management is driven by local climate and soils. To ensure they were comparing apples to apples, so to speak, they also modelled three dairy systems based on varying the duration of outdoor grazing. The models looked at durations of less than two months, three to eight months and greater than nine months leading to monikers of: confined, hybrid and fully grazed systems, respectively. This was conducted in subregions in New Zealand, the Northeastern United States and the Netherlands. Study results should be applicable to any temperate region.

Consumer-facing information has led to the belief or assumption that a system of 100 percent grazing is “better” than confined systems for animal health and welfare, reduced labor, profitability and nutrient losses. Although claims such as “pasture-fed” have created an increased pricing model for certain dairy products in many regions, there was little data to support the claims of reduced nutrient losses and environmental benefit.

likelihood of leaching and runoff. This hybrid model of housing and grazing also improves animal welfare during inclement weather periods.

He noted there is no evidence of differences in the phosphorus loss between the systems as phosphorus loss varies because it is dependant upon location (such as slope or flat), while nitrogen is not.

“The results have been given to respective industries,” he says. “There are different drivers within each of the countries that the authors represent.”

In a footnote from the study’s brief, he adds, “It is hoped that this study highlights the synergies or tradeoffs for different dairy production systems and to guide which of those could be used to lower water quality impacts.”

“In a housing system, urine and dung can be collected and distributed more evenly.”

The outcome from McDowell and the research team? Nitrogen losses were greatest in all-grazed (non-housed) dairy systems, but these losses are reduced by incorporating a period of housing during periods of high-risk for nutrient losses.

Therefore, housing in winter and early spring months allows for the controlled collection of manure to later be applied when needed to crop fields to increase nutrient uptake and reduce the

In New Zealand, McDowell says, the dairy system is primarily based on year-round pasturing. On the other end of the spectrum, he says, animals in year-round housing are proven to have health issues and reduced quality of life. Presenting the benefits from a blended system of something like seven to nine months on pasture and the remainder in housing could have positive results in the global dairy industry by bringing out the best of both systems.

“It was hoped that this would make folk aware through the understanding of these systems that there was room to change,” he says. “There are all kinds of hybrid systems like grazing for a few months. [These hybrid systems] are probably more indicative of dairy production around the world.”

In looking at the two systems and the myriad potential blended options in between both of them, there is a tipping point in terms of nutrient losses and income loss.

“A confined system creates more milk,” he says. “Hence why we thought that a hybrid system would have the benefits of both increased milk production and lower losses of nitrogen per unit of productivity. You also have the some of the benefits of grazing.”

In New Zealand, there are factors that are pushing for improvements to nutrient losses making the study even more relevant in that region. Moving to a partly housed system in areas of wet soils during winter and early spring would reduce nutrient leaching.

“It’s very important here because next year we will have very stringent freshwater targets,” he says. “A law was recently passed that every

farmer in the country had to have a freshwater farm plan to reduce their water quality footprint.”

While other regions may not have a regulatory reason to make this kind of switch, yet

the need for reduced nutrient losses is present and the pressures from consumers, advocacy groups and governments are growing.

McDowell says annual loss of nitrogen and phosphorus can range from 5 to 200 kg of nitrogen per hectare and .5 to 20 kg of phosphorus per hectare. A grazed urine patch can contain between 600 and 1,000 kgs of nitrogen per hectare.

“Given that your pasture will only take up about 250 kg of that, the remainder lost through leaching,” he says. “The more cows that you have on pasture for a greater period, the more urine is deposited on the ground. In a housed system, that urine and dung is collected and can be distributed more evenly at a time of year when runoff is less likely. That crop or pasture would have more of an opportunity to take it up; that’s provided you don’t apply a ridiculous amount.”

This means regardless of whether a dairy has housed or pastured cows – or a mix of both – there needs to be a balance of land available for nutrient distribution and cow output of those nutrients. Plus, feed supply, animal health and

welfare, production yields and financial viability need to be considered in the equation.

“You’re looking at what’s the cost from feed production from pasture versus feed production from TMR,” he says. “TMR is a hell of a lot more expensive here but, we can grow pasture year-round.”

Plus, he notes that in the U.S., grass-fed or pasture-produced milk earns much more than milk in a confined system, even though the pasture animals may be in a hybrid system.

In a hybrid model, farmers gain the improved milk production of a confined system along with the health and greenhouse gas benefits of grazing while better managing nutrients.

“Of course, many confined systems have developed as a confined feeding operation and they won’t have sufficient land to spread the manure, but if they did have the land available, they could convert to a hybrid system, reap some of the benefits,” he says, adding, “provided those benefits transfer down the value chain.”

A hybrid of grazed and housed systems may prove to be the right option for everyone.

Though winter seemed endless, it is once again time to start thinking about manure applications for the spring! While you are in the planning stage, you might be considering using precision agriculture for manure.

Precision agriculture means using variable rates based on management zones, and it has been gaining popularity over the past decade. Variable rate planting and commercial fertilizer application are the most common types of precision agriculture, but manure may soon be joining the ranks.

Many research studies show that variable rate manure application works, and that it’s economical; but there are also imperfections that make it complex. Luckily, in addition to the constant improvements of precision manure applicator technology, there are some practical methods that can increase the success of variable rate manure applications.

Precision application of manure is tricky because manure itself is not precise. It can be difficult to be certain exactly what nutrients are present in manure for a couple reasons.

For one, some of the nutrients in manure are in organic forms, meaning they are not immediately available to the crop.

Over time, those organic forms will break down into forms that can be used by plants; but the pace of that transformation is difficult to estimate since it is a microbial process that varies based on the environment.

because manure application sometimes occurs during a time crunch. Perhaps harvest was late, or planting was early, or the ground was too wet, or impending ground freeze came too soon; or perhaps storage was in danger of overflowing. Whatever the case, when application must be done on a tight schedule, it is easier to have a “just get it on the field” mentality, which leaves no time for the planning and that precision agriculture takes.

Now that we have the doom and gloom out of the way, what can be done about these challenges?

Properly sampling manure for testing is a practical way to better understand the actual nutrients applied. To get the best representation of the manure, many samples should be taken during application and mixed well.

Keeping detailed records of sample analyses will ensure planning for future applications is done with the most accurate information possible. Speaking of sampling, soil should also be sampled regularly to determine which areas of a field are in need of different nutrient management.

While it might not be a practical option for all farmers, composting can remove some of the inherit uncertainties in manure.

Through the composting process, manure is broken down in size and is made more uniform. With composted manure, you can be reasonably certain that the first load contains roughly the same nutrient content as the last.

Finally, a little planning goes a long way.

While tools and calculators exist to help estimate how quickly organic forms will become plant-available, they can never be 100 percent accurate.

Another issue is that manure nutrient content is not uniform. This is especially true for solid manures as the nutrient content in one area of a stockpile will certainly vary from another area.

And no matter how well a liquid manure pit is agitated, some variability will still exist. In addition to spatial variations, manure nutrient content varies over time. Nutrient content from storage and handling to what is actually applied can drastically vary.

Also, using variable rates might be a challenge

While inclement weather can’t always be foreseen, you can still minimize a possible time crunch by using down time (such as in the winter or before the ground thaws) to plan and prepare for variable rate applications.

During that time, you can calculate how much manure will need to be spread to sustain storage until future applications can be made, make or update detailed management zone maps for each field, and decide what rate will be applied in each management zone.

That way, even when the environment causes delays, you’ll have done all you can to hit the ground running with manure applications. •