Keep ‘em separated Making the most of your manure. | 10

Show litter some love Best practices for storing and applying poultry manure. | 12

Vermicomposting at scale Can worms work with commercial-level livestock operations? | 18

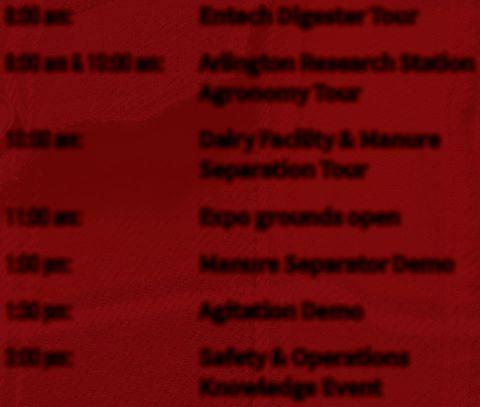

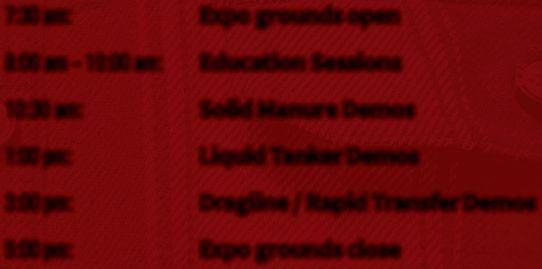

July/August 2023

Keep ‘em separated Making the most of your manure. | 10

Show litter some love Best practices for storing and applying poultry manure. | 12

Vermicomposting at scale Can worms work with commercial-level livestock operations? | 18

July/August 2023

July/August 2023 Vol. 21, Issue 4

Our annual storage and composting issue focuses on how to maximize the potential of your manure through storage solutions

4

storage safety in a wetter world. See page 8. Story by Jack Kazmierski

10 12 18 Keep ‘em separated Maximizing manure’s potential through separation technology.

BY BREE RODY

Show litter some love

Poultry litter can be a big money-maker for producers – if stored and handled correctly.

BY JACK KAZMIERSKI

Worm is the word Vermicomposting is a major innovation for composting – but can it work on a scale that supports commercial farms?

BY JAMES CARELESS

Last month, our team got a muchneeded dose of levity when going through the submissions for the North American Manure Expo’s annual “rejected slogans” contest, narrowing down to the top-50 and, eventually, the winning top-10. Just when you think you’ve heard all the manure jokes, our readers show us a few more!

Of course, we do sometimes get duplicate entries – classics like “we’re number one in the number two business” come around every year. That’s not a criticism, by the way. These slogan submissions endure because they’re true.

equation – 371 counties in the U.S. have been identified as having more manure-supplied nutrients than their crops need. Therefore, maximizing manure’s potential in terms of value means taking advantage of existing and emerging technologies – separating and processing manure can allow haulers to transport manure further afield with greater efficiency. Storing and composting manure in inventive new ways can generate energy and revenue while making the world a little greener.

Take, for example, poultry litter. While not applied at commercial scales as commonly as cattle and swine manure, producers and consumers alike are beginning to realize the value of the product for organic gardening. With the right storage and management techniques, they can stand to make big bucks off their poultry litter (page 12).

Manure management, including storage, is an area in which one must constantly innovate and improve if they wish to extract maximum value

“Many storage decisions aren’t cheap or easily reversible.”

Another slogan that emerges every year is “Smells like money!” And if you’re a farmer, you know that feeling all too well. Whatever smells that might prompt the general public to turn up their noses – whether it’s manure, machinery, rendering or other processing – are all smells you know are important parts of the process. And if you already read Manure Manager every two months, I don’t need to tell you of the tremendous value one can extract from this so-called “waste” product. But as much as manure “smells like money” to those who haul and spread it, there is still opportunity to extract even more value from manure. According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, manure was applied to only about eight percent of the 240.0 million acres planted to seven major U.S. field crops in 2021. Of course, it’s not always a simple

from their product. But decisions aren’t always easy, considering storage is one of the largest and most long-term investments of a manure operation. There are many storage decisions that aren’t cheap or easily reversible. But we can still make the best of what we have.

As always, one can never lose sight of the opportunity present. Just look at all that acreage not fertilized by manure. So stay on the ball and remember: manure smells like money. But it can always smell like more. •

#867172652RT0001 Occasionally, Manure Manager will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374 No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2023 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertisted. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

merci. gracias. danke. grazie. bedankt. obrigado.

The application of nutrients to crops has often been criticized for contributing to nutrient leaching into waterways. However, recent data from Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy dashboards indicates that positive progress has been made in terms of reducing nutrients flowing into the state’s waterways.

Nitrate and phosphorus declined considerably in 2020 and 2021. There is not yet data for 2022 included in the dashboard.

Although the five-year average for these figures has not declined notably since the strategy it was first implemented in 2013, ag officials say “real progress” is being made, and the state will continue its efforts.

The strategy is voluntary in nature, with no requirement for farmers to adopt the conservation practices it promotes, which include adoption of bioreactors, saturated buffers and wetlands.

Global pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca (AZ) stated this week that it would make a major change in its U.S. operations: switching to biogas produced from both livestock manure and food waste.

The new arrangement comes from a deal with U.S.-based Vanguard Renewables. It will source manure from three Massachusetts farms with about 900 cattle each, combined with food waste. The energy produced will be equivalent to the energy needed to heat nearly 18,000 U.S. homes annually.

AZ has stated publicly that it aims to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions it directly

produces by 98 percent by 2026. An analysis from 2022 found that the carbon output of the global pharmaceutical/ biotech industries is greater than that of the forestry and paper sector.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and environmental intervenors reached an agreement in April (fully executed May 11) under which the DNR will not require groundwater monitoring of land application sites if Casco-based Kinnard Farms “substantially eliminates” the land application of liquid manure within approximately four years.

In a statement, Kinnard Farms expressed excitement about the agreement, stating that this gives the business the opportunity to “move forward with the installation of state-ofthe-art manure management technology.”

Kinnard Farms is installing technology to transform liquid manure into three separate, pathogen-free products: clean water, dry organic fertilizer and an organic ammonia fertilizer. According to the farm, this technology is the first of its kind in Wisconsin. “The technology will remove most of the truck traffic from our local roads and greatly reduce the need for long-term storage of liquid manure in lagoons,” the farm stated. “Removal of the water from the manure hastens our ability to increase our family’s already

extensive use of regenerative agricultural practices, allowing us to plant cover crops and eliminate tillage on an even greater number of our fields. These practices are proven to regenerate soil health, prevent erosion and sequester carbon, and are highly protective of water quality.”

Kinnard Farms expressed appreciation on the part of other parties to “come to the table in pursuit of the common goal of protecting our precious water and soil resources.” The agreement formally recognizes that Kinnard Farms is currently working with a partner to develop this

treatment facility, and also formally recognizes the benefits of the technology and the likelihood that it will eliminate the land application of liquid manure by the farm. As such, DNR will not take action to enforce permit terms that are currently stayed due to the pending contested case, and DNR will retain terms and conditions relating to groundwater monitoring of land application sites in Kinnard Farms’ reissued WPDES permit, making only limited changes to provisions concerning the mechanics of groundwater sampling.

Groundwater monitoring of land application sites will only need to be completed if Kinnard Farms proposes to land apply liquid manure after the fourth anniversary of the reissued WPDES permit — the target timeframe for Kinnard Farms to effectively eliminate its need to land apply liquid manure from its dairy.

The agreement includes project milestones, designed to ensure that efforts to construct and operate the facility remain on track. Kinnard Farms also commits to provide periodic progress reports to DNR and the intervenors.

PHOTO BY JOHN MACIEL

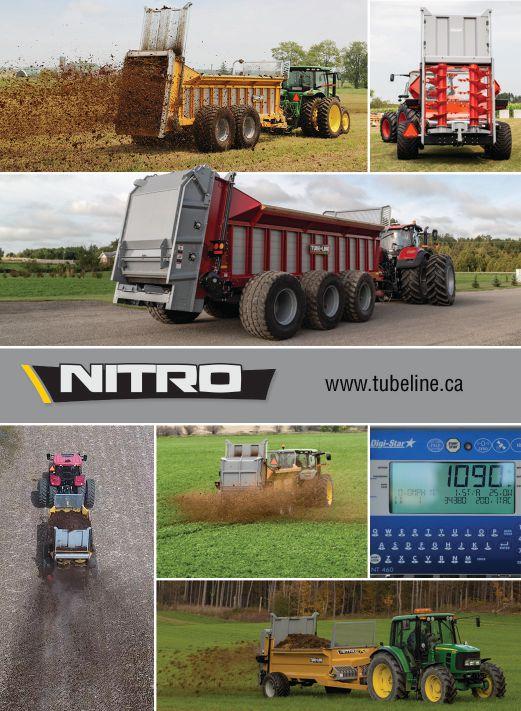

A report by global market research firm Transparency Market Research predicts that the global manure spreader market will cross the billion-dollar mark for total valuation in in the next decade.

The global manure spreader market was valued at just under $1B in 2022, at USD $980 million. By 2031, it is projected to reach $1.3 billion. The current growth is driven by a consistent increase in adoption of manure spreading equipment in developed countries and the development and production of new agricultural equipment. This includes advanced designs in side-discharge and rear-discharge spreaders, as well as manure spreaders with integrated industrial IoT.

Additional opportunities identified include government subsidies to farmers for the adoption of new equipment, although high investment and market fluctuations are highlighted as possible restrictions.

Three-axel machines are expected to take the lion’s share of sales, followed closely by two-axel machines. The North American market will continue to dominate, with Europe and APAC close behind.

Utah-based Resonant Technology Group has released peer-reviewed research from the University of Milan and UC Davis, published in Sustainability reporting significant reduction of GHGs from dairy lagoons within weeks of the first use of its SOP Lagoon product. Specifically, the lagoons saw 80 percent less methane and 75 percent less carbon dioxide.

SOP Lagoon is a pit additive developed by Italian Firm Save Our Planet and marketed by Resonant.

The study took place over three-and-a-half months in-

field at a 520-head dairy in Northern Italy.

According to Resonant, a 250-head dairy farm would require 3.7 ounces of product per head per year, resulting in an approximate retail cost of $2,000.

The University of Milan study also cited observations by farmers and researchers alike that the product reduced or eliminated noxious odors flowing from dairy operations.

U.S. dairy Tillamook County Creamery Association, has also used the product, citing similar results in odor elimination.

Responsible storage and effective prevention strategies are key.

BY JACK KAZMIERSKI

Acommon form of liquid storage, manure lagoons are a practical solution to a perennial problem: how to store large amounts of manure before it’s needed as a fertilizer.

A report published by the Mississippi State University Extension Service sums up the benefits of this manure storage system: “Lagoons are pond-like earthen basins sized to provide biological treatment and long-term storage of animal waste. Livestock lagoons are small-scale waste treatment plants containing manure that is usually diluted with water and rainfall. Lagoons are designed to enhance microbial digestion of organic matter and volatilization of nitrogen compounds, thereby reducing the land area requirements for disposal by 50 to five percent.”

While the benefits of lagoons are clear, there are some challenges and dangers that need to be considered and managed when employing this manure storage system.

A Mississippi State University Extension Service report explains the issue: “There is a danger of effluent leaching into groundwater if the lagoon leaks, so proper lagoon construction is required. Overflow events or embankment failure can result in large volumes of effluent discharge with severe environmental impacts (fish kills, water quality destruction, and soil contamination) and legal consequences (fines, penalties).”

example, can cause lagoons to overflow, adversely affecting the environment, wildlife and even the human population.

The University of Minnesota Extension published a paper in 2021 outlining some of the measures farmers can take to prevent this problem. The paper explained that most manure spills occur when a lagoon overflows or is damaged. The solution: “Monitor and pump pits and lagoons before they reach the level where a large rain event could cause overflow. Installing a liquid level marker/gauge is a good way to monitor pit/lagoon depth since it will indicate when storage is getting too full. Inspecting pits and lagoons for any rodent or erosion damage will also help prevent spills or leakage. Fix any damage found immediately so that the problem does not worsen.”

The report then offers the following advice: “Lagoons should be filled with water [from] one-third to one-half of the design volume before introducing manure into the lagoon. This will minimize start-up odors and ensure sufficient dilution water is available for the establishment of bacterial activity.

“Starting a new lagoon in late spring/early summer is best and will allow establishment of a bacterial population before cold weather and help prevent excessive odors the following spring.

“Generally, the bottom liner of most lagoons is compacted earth. Some type of clay is the preferred material. Materials such as bentonite can be added to improve the acceptability of soil for liner material. If the soil type is inappropriate, then an impervious liner may need to be added (plastic, concrete, etc.).”

Even if a lagoon is properly constructed, problems can arise if the lagoon is filled beyond capacity. A major rainfall, for

Bill Field, professor, department of agricultural and biological engineering at Purdue University explains that measuring the liquid level is vital and that it’s not something that should be left to chance.

“Many locales have zoning ordinances in place about how full [lagoons] can be before you have to stop adding manure to them,” he explains.

Diligent monitoring of lagoons is a must. A 2020 report published by North Dakota State University, entitled “Manure Spills: What You Need to Know and Environmental Consequences,” stressed that “Prevention is always the best means to minimize the risk of manure spills and the resulting environmental damage.”

The report recommended taking the following steps to prevent manure spills from lagoons: “(1) Install a permanent marker/staff gauge and regularly monitor manure levels. (2) Make proper liquid level management a year-round priority. (3) Reserve maximum storage capacity for times when open fields are not available/extended wet weather prevents application. (4) Pump down the liquid level or take action to remove liquid from storage and properly apply or transfer it to another storage structure when the pond has reached its maximum operating level.”

While water is essential for a lagoon to function properly, too much of it can be a problem. A cover would seem like a natural way to keep excess water out of a lagoon, but as Purdue

ABOVE

An on-farm manure storage pond.

BELOW

An aerial view of a manure lagoon; specifically, a swine treatment manure lagoon.

University’s Field explains, that’s not always possible, practical or cost-effective.

“There are lagoons that are smaller, deeper and have covers over them,” explains Field, “And they’re often found where you have a lot of rainfall. But some lagoons cover several acres, and building a roof over them would costs hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

While a solid roof isn’t always cost-effective or possible, some lagoons benefit from other types of covers. Iowa State University, Extension and Outreach published a report on how a variety of permeable and impermeable covers can reduce odors and emissions from lagoons. The report highlighted the pros and cons of both types of covers.

According to the report, an impermeable cover “increases nitrogen retention in the manure, reduces dilution of manure due to rainwater, and can be used to capture methane gas produced by manure.” A permeable cover, on the other hand, will not reduce dilution of manure from rainwater or capture gases, but will increase nitrogen retention. It’s also easier to apply.

The same report offered examples of permeable covers: “natural crusts, layers of natural vegetative materials (such as straw, corn stalks, ground corncobs, etc.), vegetable oils, permeable fabrics (geotextiles), as well expanded clays, ceramics,

and ground rubbers (examples include LECA and Macrolite).”

Impermeable covers, according to the report can be either rigid and flexible. “Examples of rigid covers include concrete, wood/metal roofed structures, and plastic coated fabrics stretched over framing,” the report explained. “Flexible covers are generally plastics, including geomembranes and geosynthetic materials, are typically constructed of high-density polyethylene, linear lowdensity polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, or similar.”

The report added that “impermeable covers provide excellent odor and emission control, but have a high capital cost. Permeable covers generally are not as effective, but generally have a substantially lower capital cost.”

Occasionally, freak storms can overwhelm a lagoon, whether or not it has a roof or a cover. Massive amounts of rainfall can cause lagoons to flood, leading to an environmental disaster. The only way to deal with these once-in-a-century weather events is to prevent the disaster from happening in the first place. In other words, the lagoon must never be allowed to overflow in the first place.

As noted in the report from North Dakota State University, “Prevention is always the best means to minimize the risk of manure spills and the resulting environmental damage.” That’s why when back-to-back storms dumped excessive amounts of rain on Western Washington in late 2021, everyone worked together to prevent a disaster.

Whatcom and Skagit counties were hit especially hard by the storms, and according to reports, a total of more than 30 million gallons of liquid manure was at risk of spilling out of lagoons and into the environment in those two counties.

No amount of cover, and no roof would be enough to handle the deluge. The only solution was to move the manure out of the lagoons before they overflowed, which is why the state Department of Ecology, the Conservation Commission, local officials and the affected farmers worked together to avert the disaster.

Some of the manure was pumped through existing buried manure lines, and some was trucked out of harm’s way. Some farmers used their own trucks, while others hired contractors. According to a report published by the Washington State Department of Health, the cost of moving all that manure was roughly $360,000, but well worth it when contrasted with the cost of the environmental disaster that was averted.

That same Washington State Department of Health report concluded with a statement that puts into perspective the challenges facing communities throughout North America as our planet deals with climate change: “Recent rains continue to threaten water quality in Western Washington. We continue to work to keep people in Washington safe from disease when flooding and other incidents occur.”

Indeed, as weather patterns change, leaving some part of North America wetter than others, it will be increasingly important for everyone to work together, and for lagoons to be properly maintained and properly managed.

The key to averting a disaster, whether it’s caused by a single lagoon leaking its contents into nearby water systems, or by a once-in-a-century rainfall event, we’re going to have to work together with the same mantra in mind: “Prevention is always the best means.” •

Capitalizing on innovations in separation.

BY BREE RODY

If you’re a regular reader of Manure Manager –whether it’s because you’re a custom applicator for hire or because you manage and apply your own manure on your farm – you don’t have to be told about the value of manure. That’s why it’s practically an industry curse word to refer to manure as a “waste” product.

However, a new study from the USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) has found that there is nevertheless still plenty of value to be extracted from manure – and that, whether or not “waste” is a dirty word in the livestock world, plenty of nutrients from manure are, indeed, going to waste. For the year 2021, manure was applied to only about eight percent of the 240.9 million acres planted to seven major field crops in the U.S. There’s potential for much more activity, particularly considering the rising demand for organic food in the U.S.

Unfortunately, the problem is not quite as simple as convincing more growers to fertilize using manure.

Ray Massey, extension professor of agricultural

ABOVE

economics at the University of Missouri, and one of the research study’s co-authors, says it’s not simply a matter of looking at the land and assuming you will get a certain dollar value per acre – because not all cropland needs the same nutrients. When manure-supplied nutrients exceed crop needs, crop producers will not demand the excess nutrients, lowering their value. According to the study, 371 counties in the U.S. have been identified as having more manure-supplied nutrients than crop needs. And therein lies the logistical challenge.

“It really is all about capturing the value of the manure nutrient,” says Massey. “Take phosphorus, for example. If you’re able to take phosphorus and label it at 50 cents per pound, but you’re putting it on land that doesn’t really need phosphorus, then there’s no value to that phosphorus.”

But in challenge often lies opportunity.

“If you’re able to haul [the manure] an extra two miles to some land that needs phosphorus, then you’re capturing that value.”

The study found that producers who make better

Stored manure can be separated at a farm level through various means, starting with a method as simple as a screen or filter.

use of existing and emerging technologies including solid-liquid separation, composting and anaerobic digestion technologies, will obtain even more value from their manure.

Many are already taking advantage of existing and emerging innovations – Manure Manager has profiled its fair share of farms implementing anaerobic digesters, and our in-house podcasts have explored the time, money and emissions that can be saved using precision technology in the field. Nevertheless, according to the report, there is still plenty of money to be saved.

One of the first steps in realizing the value of manure is in separation – the separation of solid and liquid matter can allow producers and haulers to transport nutrients to where they’re needed more efficiently, and for overall more efficient nutrient uptake.

When economic studies find that money is wasted, that generally does not mean farmers are writing cheques on wasteful purchases. Instead, that money is generally wasted through the expenditure of too much time and effort on a task, which could otherwise be spent elsewhere – such as equipment that breaks down, practices that don’t net any returns.

Massey adds: “It really depends on what the return to assets or to equity that they’re seeking.” Some of the study conducted in Missouri found that there is indeed a return, but not one so high that one might invest in growing a livestock operation.

However, solid-liquid separation, says Massey, is “not a money loser.”

There are a number of different methods for solid-liquid separation, which all come with different advantages and barriers.

Some of these methods, say Massey, are pricey enough that they would have to be installed in a new build. “Ideally, they would do it in a new facility, as opposed to retrofitting an old facility.”

However, one of the most accessible methods for separation is through a screen. Of all the various separation technologies listed in the USDA study, screens were the only method that did not have cost listed as a barrier. “That’s the easiest to manage,” says Massey. “A screen system is pretty much a passive system.”

There are different forms of screens; farmers may choose to implement mechanical screens such as rotary drums or

sloped screens; they might also opt for nonmechanical screens such as weeping walls, baffled sedimentation basins. Both types function by ultimately minimizing the amount of solid material entering lagoons. This gives the lagoon greater capacity to hold liquid and reduces related costs for farms to remove solids from the lagoon. As an added benefit, screens remove some nutrients – estimated to be five percent of nitrogen and phosphorus for mechanical screens versus 10 percent of N and 18 percent of P for a two-stage weeping wall.

Most screens come with a relatively affordable price tags, at approximately USD $40,000 for a 120-head dairy farm. The study identifies these as a viable “first step” toward better manure management and better management of nutrients.

Centrifuges and presses are other examples of separation technology that makes for more efficient management of manure nutrients. However, Massey says these would be more typically installed in new builds – although he adds that his fellow Missouri professor and study co-author Teng Lim has more experience with farms that

retrofit on various separation technology. Centrifuges, like screens, are ideal for high-moisture manure such as hog and dairy manure and can work on mediumto-large farms. The practice of a centrifuge is nearly a century old.

In a conventional centrifuge system, a liquid-solids slurry, typically with three to 10 percent solids content, is introduced into a tube, which then spins at high speeds to separate solids from liquids. The separated solids are discharged from the centrifuge with solids content of 18 to 26 percent.

Centrifuges have also been noted to remove particles that conventional cloth filtration and microfiltration would screen.

There are, of course, barriers to centrifuges, with cost being the biggest. Additionally, polymers – chemicals added to increase aggregates and enhance separation – might be needed. Additionally, centrifuges require a high degree of power. The centrifuge requires 10 times more power than a screw or belt press, and maintenance costs and management costs are another factor to consider.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 20

No matter how challenging your needs, V-FLEXA is your best ally for agricultural trailers, tankers and spreaders. This latest-generation product features VF technology, which enables the transport of heavy loads both in the fields and on the road at lower inflation pressure. V-FLEXA is a steel-belted tire with a reinforced bead that provides durability, excellent self-cleaning properties and low rolling resistance even at high speeds.

V-FLEXA is BKT’s response for field and road transport with very heavy loads avoiding soil compaction.

APoultry litter is more valuable than ever. Here’s how to make the most of it.

BY JACK KAZMIERSKI

Poultry manure (litter) is an increasingly valuable nutrient source. Because poultry farmers now stand to make more from poultry litter than before, best management practices are key to assuring maximum profit while retaining nutrient value.

Shawn A. Hawkins, professor and extension specialist, biosystems engineering and soil science, University of Tennessee explains that the majority of the birds produced in his state are broilers. “They’re raised on an open floor, usually with some type of bedding,” he says. “We produce successive flocks on that dirt floor, and we get a buildup of litter that is managed in different ways.”

ABOVE

Hawkins says that the litter ends up as a mixture of a number of components: spilled feed, manure, the used bedding, and feathers.

While litter storage is an option, and one that many poultry farmers will find practical, Hawkins recommends using litter right away. “Rather than store it, you want to remove it at the time when you have crop demand, and directly land apply,” he says. “That’s the best approach.”

If applying the litter immediately isn’t an option, the good news is that storing litter won’t significantly impact its nutrient value. “The losses during storage are

A litter shed containing poultry litter material in Tennessee.

frankly pretty small,” says Hawkins. “Now, I’m not suggesting that you could take this material and store it for years. That would not be a good practice, because some of the moisture content is going to be lost, and the nitrogen content will be reduced.”

The vast majority of the nitrogen is associated with organic compounds, Hawkins adds. “That material has to be broken down in the soil to become plant available, and it’s fairly stable when it’s stored,” he says. “The ammonia of course is not, but that’s a minority of the total nitrogen that’s in the litter – perhaps, on average, about 15 to 20 percent. So that material is prone to being lost during storage, but it’s not the majority of the

nitrogen that’s present in the litter.”

In other words, nutrient loss is not a big issue with litter, except if it’s stored too long or in the wrong environment. “There isn’t a mechanism for nutrients to be lost during storage, especially if the litter storage building has a roof,” explains Hawkins. “It would be different if the material was stored in the field for many months at a time, which is not a good practice. And you can have losses of potassium when litter is field-stored for quite some time.”

Storage is not an issue for poultry farmers in Tennessee, says Hawkins. “Our bigger problem is that there’s a large demand for the litter by row crop producers in our state,” he says. “The issue is that everyone wants the litter, all at the same time.”

The high demand for litter translates into higher costs for those who want to purchase it. It also means that the litter supply can be exhausted before all the demand is filled, which is why some farmers have to do without. “That’s the scenario that is most common in West Tennessee right now,” he adds. “We have more demand for the litter than we can actually supply.”

The old laws of supply and demand certainly apply to litter, which means that the prices for litter have gone up in recent years. “The value varies with fertilizer prices,” explains Hawkins, “and it has gone up dramatically.”

He adds that in areas where demand is high in Tennessee, the price might be $50 per ton. “And if you were to go in and do your evaluation, based on your litter analysis, you’re going to see that obviously, the litter has more intrinsic value than $50 per ton,” adds Hawkins. “But you’ve got the cost of transportation and applying it, which can be pretty significant.”

In areas where demand is low in Tennessee, it’s not unusual to be able to get litter for half that price. “As you move east in Tennessee, where more and more of the of the litter is going on pasture and hay fields, the value of the litter is significantly reduced,” says Hawkins.

The $25 to $50 per ton price for litter today in the state of Tennessee, as an example, is much higher than it was even a few years ago. “If we go back five years, it would not be unusual to get litter for $15 a ton, particularly in east Tennessee,” adds Hawkins.

Knowing that the price of litter is high in one part of a state, and lower in another, some enterprising individuals have decided to buy low, load the litter onto a truck, and sell high in another part of the state. “I talk to producers every year who transport dry manure and litter products, but frankly, I’m not sure it adds up once you consider all the costs,” says Hawkins. “A good rule of thumb: Don’t move litter more than about 10 miles.”

A common practice in Tennessee, according to Hawkins, is poultry producers using a third party to clean out the litter. “A lot of our newer farms do not have litter storage buildings,” he explains, “so they will rely on what we call a litter clean-out service. They, in effect, become a dealer/broker for the litter: They trade the clean-out service for the litter itself, and then they make a profit by marketing the litter to producers who are interested in using it as a fertilizer.”

How litter is stored will affect its value and nutrient content. As with all things, there is a good, better, best scenario. “The worst is long-term field storage, where you do not have the material covered with a tarp or in a storage building,” Hawkins explains. “I would not say that’s common, but I do see it occasionally.”

The better option would be to store litter in a dedicated litter storage building, and then time the removal of the litter with the nutrient demand by local farmers. Hawkins says that these buildings commonly have concrete floors, but not always. In Mississippi, for example, dirt floors are common. A roof typically covers the structure, and the buildings have to be well ventilated.

“Many of our litter storage barns don’t have open sides,” he adds. “They have a covering on the sides of the building that prevent windblown rain from getting in and wetting the stored letter.” Mixing dry and wet litter can lead to fires (more on that below).

“And then the best practice, in my opinion, would be if a row crop producer

had neighbors that had barns, then they would ask when they’re going to be removing litter,” adds Hawkins. “They would then apply the litter directly. In other words, they would remove it from the house and take it straight to the field to land apply within four weeks of planting a crop that has a high nitrogen demand, such as corn.”

A key concern with litter storage is the high possibility of fire. Hawkins warns against stacking litter too high, because litter storage buildings are prone to fire when the litter is stacked too high.

“I’ve witnessed it probably a dozen times in Tennessee,” he says. “These buildings are sized based on the production rate of litter, and then they’ll size them based on the density of the litter, assuming that you’re not going to stack the material more than six or seven feet high.”

Stacking the litter higher than six or seven feet can lead to overheating, which in turn can cause spontaneous combustion. “If wet litter is stored next to dry litter,” Hawkins explains, “that interface will be where spontaneous heating begins. The high bacterial activity within the litter itself begins, and then it

becomes a runaway biochemical process. So the reason we recommend not stacking the litter too high is to limit the amount of mass that you’re accumulating so that there’s more dissipation of that heat.”

This is also why it’s important to cover the sides of the building in order to prevent windblown rain from wetting the litter, which would also create an ideal environment for bacterial activity, leading to overheating and fire.

If producers cram the litter into a building, stacking it 10 or 12 feet high, that can lead to trouble, explains Hawkins. “There’s more mass there for heat retention, and that’s when it’s a problem,” he adds. “I’ve seen numerous storage fires over the years, not just in Tennessee, but in other states as well.”

Hawkins concludes with a warning to all managers of litter buildings: “I wouldn’t say that fire is uncommon. It’s a problem to be expected if litter is not stored properly.”

Properly collected and properly stored, litter can offer poultry producers a sizeable return, especially now that fertilizer prices have increased dramatically. •

Building vacuum spreaders up to 8,000 Gal. with: -Hydraulic Top Hatch -Rear Mount Injector -Wallenstein Vacuum Pump

-35.5 x 32 Radial Tires -12 Bolt Hubs -8" Boom Loading Arm

AgrifoodJobsite.ca is Canada’s premier online job portal for the growing agrifood sector. A laser focus on the right people across the country’s largest agrifood media audience means you get the right applicants the first time. No more massive piles of unqualified applicants, just professional employers reaching qualified professionals.

Powered by the top agrifood media brands in Canada, the reach to over 500,000 industry professionals on AgrifoodJobsite.ca is amplified by:

Website advertising to 185,000 qualified monthly site visitors

A comprehensive and magnifying reach across multiple associated job boards

Email promotion and job alerts to 131,000 industry emails using Canada’s largest CASL-compliant direct access to agrifood professionals

Social media promotion to all brand networks on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn

10

Could vermicomposting manure work on a commercial scale?

BY JAMES CARELESS

Never underestimate the manure management power of earthworms. That’s the lesson inherent in vermicomposting, the natural process by which earthworms consume manure and then excrete an ecologically benign natural fertilizer known as “worm castings.” (A more accurate term might be “worm manure”.)

“Vermicomposting is a degradation and stabilization of organic wastes by earthworms and microorganisms into soil amendments that are rich in plant nutrient elements, high water holding capacity and contain plant growth regulators,” says Dr. Norman Q. Arancon, of the University of Hawaii at Hilo.

The usefulness of vermicomposting for consuming manure has been explored in Manure Manager magazine previously (‘Digging into vermiculture” by Alex Bernard: https://www. manuremanager.com/digginginto-vermiculture). However, the question that matters most to manure managers is whether or not this approach can be used for large-scale manure conversion. Here is what we have found.

its first stage, which kills off some beneficial bacteria and motivates earthworms to leave. Curing allows this process to reverse.

Speaking of vermicomposting manure systems – which do not heat up quite significantly – the rule of thumb is to mound them no more than two inches high and eight wide “because you need to stand on both sides of that pile and be able to look into the middle of it,” says Rhonda Sherman, a retired extension specialist formerly with the department of horticultural science at North Carolina State University. “You need to put your eyes on all parts of the pile, so that you can check the conditions for the earthworms.”

“Worms should not be crowded, so the ideal stocking density is 150 earthworms/L of wastes,” recommended www.Ontario.ca. “Earthworms ingest about 75 percent of their body weight/day; a 0.2 g worm eats about 0.15 g/day. If you discover earthworms trying to escape any system, it is a good indication that something is wrong with their feed or environment.” (Note: Christie says the actual percentage is “more like 25 percent”).

VERMICOMPOSTING REVISITED: A QUICK PRIMER

Vermicomposting is a natural aerobic process which differs from traditional composting. Earthworm casts are a ready-touse fertilizer that can be used at a higher rate of application than compost, with nutrients released at rates growing plants prefer. In terms of the actual amount that can be added, “general industry knowledge is anything more than 20 percent by volume can be detrimental, depending on the plant and soil,” says Cristy Christie, owner of Black Diamond VermiCompost in California

Better yet, it only takes earthworms 22 to 32 days to convert organic wastes into casts, depending on the density of the waste and how mature/large the earthworms are. Once the casts are ready, they require two weeks for their natural ammonium to convert into nitrate, a substance that plants can use.

In contrast, regular composting requires 30 to 40 days, followed by three to four months ‘curing’. This last phase is required because compost generates a lot of heat during

As for the right mix for vermicomposting rows? “Cow dung is added with water and mixed well to allow the gasses to evaporate,” says Dr. Venkatesh Devanur, managing director of Som Phytopharma (India) Ltd. At his company, they “dry the slurry to 40 percent moisture. Spread the dung to one metre width, 10 metres length and 0.5 metre height, and spread earthworms on top of the bed.”

“When we look at the effect of the worm compost on the yield, we didn’t see much,” says Dr. Medhi Sharifi, research scientist at the Summerland (BC) Research and Development Center. “But when we look at yield quality, which is very important in wine making, then we see some positive effects. We also noticed that the size of each cluster in the grapes increases when we apply vermicompost.”

“Some observations we have received from growers was the reduction in powdery mildew where vermicompost is used,” he adds. “Powdery mildew is a major fungal disease in grapes, and it causes significant damage yearly to production. ABOVE

Vermicompost from pre-composted dairy manure after 70 days.

The observations that we collected was that when we applied the vermicompost spray, the need for spraying powdery mildew afterwards was significantly reduced.”

Having established that vermicomposting is a good way to convert manure into an odourless, efficient fertilizer, the next question is whether or not vermicomposting be used on medium- and large-sized cattle farms?

“The vermicomposting system is practical for farm operations since a farm is a good source of organic wastes,” says Arancon. “There are vermicomposting operational units that can even be set up on a household level, so a medium-sized livestock farmer should be able to set up this a system suitable for his scale.”

The same is true for the largest cattle and dairy farms; the only variable is space. Now a large-scale vermicomposting operation “is going to take up more room than your typical mechanical separation system,” said Rick Naerebout, CEO of the Idaho Dairymen’s Association, “so you’re going to have to have the space to do it. But part of what we really like about vermicomposting is the fact that it’s scalable. So depending on the number of cattle you have and the effluent you have to treat, you can scale it to fit your facility: just increase or decrease the number and size of the worm beds you have to fit. After that, vermicomposting is a fairly straightforward technology. It doesn’t take somebody with an advanced degree to know how to run it.”

To set up a vermicomposting operation, one needs to set up a system in “which processed manure are set up in windrows on a relatively flat surface, inoculated with earthworm and after a period of time, processed manure are harvested by separating the earthworms from manure,” Dr. Arancon said. “A more automated system would be based on a continuous flow reactor that allows automation of the process. This will consist of a container equipped with a screen at the bottom to allow harvesting of processed manure at this portion of the system while continuously feeding earthworm at the top portion of the set

up. This setup will naturally separate the earthworms from the processed wastes since earthworms will be continuously fed on top leaving the bottom portion of the system processed and then harvested.”

According to the experts, farmers can build their own vermicomposting systems, or hire third-party experts to do the work. One good source for mastering this topic is Sherman’s book, The Worm Farmer’s Handbook , which is available at bookstore.acresusa.com.

And the output of such systems can be impressive, whether for use on one’s own farm or for sale to other farms and the public. “Even a farm with just 10 cows can get 50-75 kg of dung per day that can give 20-25 kg of vermicompost a day,” says Devanur.

This said, “a large farm would likely need an expert in worms on staff,” says Christie. “Worms are livestock too, so the same level of knowledge is required for them as it is for cows, horses or pigs.” •

www.yokohama-oht.com

For decades, manure applicators and livestock producers have counted on Alliance, Galaxy and Primex tires for reliable performance on the toughest jobs and slickest conditions. We provide high-speed flotation tires for slurry tanks and manure spreaders, rugged skid steer tires, high-performance loader tires, the most complete line of VF tires in the industry, and much more.

Ask your tire dealer about Alliance, Galaxy and Primex tires; call us at (800) 343-3276; or visit yokohama-oht.com.

Need speed? Check out our new 850/50R30.5 Alliance 885 radial, with its 182D load index, the 885 radial 710/40R22.5 165D, or the updated Galaxy Super Soil Softee 850/50R32 with its 183D index! 800-343-3276 | @yokohamaohta

TIRES FOR EVERY JOB!

• Great warranties

• Top performance

• Great return on investment

Because of the cost barrier associated, Massey says it’s highly unlikely one would retrofit an operation they are already running to add a centrifuge. However, he says it might be a smart idea for someone installing a new system. “If you’re going to spend [the money] on a lagoon or other form of separation, it’s not going to double the cost, it’s going to add a percentage onto the cost,” says Massey. “They can make a positive return on investment, [although] not a high return.”

Centrifuges, along with filtration and dissolved air flotation technologies, separate fine solids from liquid. Those, too, are cited as having high costs, with filtration being identified as “high to very high” costs. Some advancements have occurred in filtration, including metal membranes and vibrating membranes. At least two companies have begun to offer titanium and stainlesssteel membranes to extend operational life. However, the study notes that these technologies are new to market, and the effectiveness remains unclear.

Presses, which dewater coarse fiber and

fine solids, are often a core component of recycling fiber for animal bedding. The three main forms of presses are belt presses, which conveys the solids on belts with small perforations and through a series of rollers with increasing pressure; filter presses, which uses a series of filter bags on a rack or bar; and screw presses and moving ring/disc presses, which moves the solids through a cylinder using an auger. Press systems can begin to process slurry at three percent or higher solid content, and they produce an end product called “cake” with a solids content of 30 to 50 percent.

Once manure has been separated into solid and liquid, even through something as simple as a screen, Massey says an operation needs to then ensure that it’s able to distribute the manure effectively. “You need liquid distribution equipment and solid distribution equipment,” he says. “The benefit we found here in Missouri is that… if nearby land is already high in nutrients, the liquid can be distributed nearby [and] the separated solid, because there’s more

nutrients per ton, can be hauled a greater distance. If you do have a system where you’re trying to move it further away to a land that needs more nutrients, the solid-liquid separation can change that.” In general, with separation, Massey says liquid can be applied more closely, whereas solid can be applied at a greater distance. He points to programs such as the National Resource Conservation Service’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), which can provide grants or subsidizations. “EQIP is what most people would rely upon. There are also some local soil and water conservation district programs that... subsidize it in some way through a cost share. But those would be very specific. Even Missouri, there would be a couple counties that might not [subsidize].”

In the end, says Massey, the goal is to capture the value of the manure nutrient – and not just nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. “Is there sulfur that you can value? That’s becoming a more important nutrient, and [it’s important to] actually understand if your manure contains sulfur.” •

Bazooka Farmstar has unveiled two new innovations.

The Phantom 2 Injector, a liquid manure injection unit, is designed for longevity, little-to-no in-season maintenance and easy-to-replace wear parts, ensuring uniform nutrient coverage across the entire field by precisely injecting liquid manure four to six inches beneath the surface.

The Phantom 2 Injector can apply and cover 2,500 up to 20,000 gallons per acre (GPA), or up to 25,000 GPA with the Phantom 2 Edge upgrade.

One of the key features of the unit is its little-to-no in-season maintenance requirement. The greaseless main pin and closure pin bushings, as well as the heavy-duty sealed main hub and closure hub bearings, make the unit entirely maintenance-free during the application season. The Phantom 2 Injector also features easily replaceable bolt-on subcomponents and wear parts for simple, low-cost maintenance and repairs.

The Phantom 2 Injector is only available fully assembled on new Bazooka Farmstar Titan toolbars and Standard tank bars. The Phantom 2 will offer two downforce options: spring or hydraulic.

Additionally, the company used the recent World Pork Expo as the stage on which to announce its new 42′ and 52′ Outlaw force-feed trailers, as well as the Renegade 2 agitation trailer.

Bazooka Farmstar has designed these trailers to efficiently pump and agitate the deepest lagoons, pits, and slurry storage. These agitation and pump trailers are ready to maximize operations with over 4,000 GPM and 10-inch plumbing.

Visitors to the Iowa event were given the exclusive opportunity to witness the new products in action.

More information is available at www. bazookafarmstar.com.

Agronomy and input manufacturer Brandt will break ground on a new production facility in Aurora, NE later this summer. To be called Advanced Ag Formulations, the 100,000 square-foot facility is expected to open for production in the third quarter of 2024.

The facility will produce the full line of Brandt’s products including the Brandt Smart System, Brandt Manni-Plex and Brand EnzUp.

Bill Engel, EVP of Brand, said in a statement that the plant will better enable to company to serve its existing and new customers in the upper Great Plains. “This is our first ‘clean-sheet’ plant in the U.S. for many, many years,” said Engel.

ABOVE

Dairy cows in Ireland, where farming advocates fear climate strategies could make livestock “collateral damage.

First, the government in The Netherlands made outlandish statements that thousands of cows needed to be culled in order for it to reach emissions targets plucked from the air. Now, the Irish government is the next to follow.

I think the savvy amongst us agree that the climate is changing and something needs to be done about it to prevent us from cooking, but picking on livestock farmers is a drastic measure gone too far.

Sure, cows do produce methane that add to GHG emissions, but so do aeroplanes, large factories all over the world, and the millions of wildlife that roam the savannas.

A few weeks ago, the Irish government drew the ire of its dairy and beef farmers even more by releasing figures suggesting 65,000 cows per year need to be culled over a three-year period to meet emissions targets.

Released under a Freedom of Information request, the cow cull numbers, deemed to be compulsory, came with an alarming cost of

€200million per year to the taxpayers in the Republic of Ireland. However, some farming bodies have hit back hard saying any such a dramatic cull must be on a voluntary basis as farmers had taken out business loans in the past, based on their cow numbers, and therefore could be put out of business.

Responding to the disclosed figures, Ireland’s Department for Agriculture said the report was merely a “modelling document” and not a “final policy decision.”

Dairy cow numbers in Ireland have risen since the abolition of milk quotas in April 2015 with numbers currently totalling 1.5 million head. Also incorporated in the country’s total cattle tally of seven million head are just over 900,000 beef cows.

Dairy cow numbers rose by 1.4 percent (22,800 head) to 1.6 million in 2022 but over the past decade have increased by around 40 percent. The latest (January 2023) numbers suggest a fall to 1.5 million.

Beef cow numbers, however, have fallen about 17 per centover the same period and saw another

2.9 per cent (27,100 head) drop from 2021 to 913,000. The Irish government, just like the Dutch government, have told farmers they will be compensated for their loss of livestock, but concerns have been raised about payment rates and what percentage of their herd must each farmer cull.

Pat McCormack from the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers Association said: “If there is to be a cull scheme, it needs to

be a voluntary scheme.

“That’s absolutely critical because there’s no point in culling numbers from an individual who has borrowed on the back of a huge financial commitment on the back of achieving a certain target that’s taken from under him.

“We should be investing in an infrastructure that can deliver from a scientific perspective. And we know low emissions are better and we should be

A dairy cow in Ireland, where the government is looking to cut GHG emissions from agriculture by 25 percent.

continuing to invest in further science and research because that’s absolutely critical as we move forward.

“This isn’t a start. This isn’t the end. This is an environmental journey and agriculture can play a significant role there,” said Mr McCormack.

The Irish government is focused on cutting GHG in the country with agriculture as a main target given it is the single biggest greenhouse gas polluter, accounting for 37.5 percent of emissions in 2021. With the sector emissions rising each year, the government is aiming for a 25 per cent emissions reduction target for agriculture by 2030.

This means agriculture has been tasked to reduce its emissions by a total 5.75 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent the end of 2030.

However, in a bid to reduce the

tensions their figures already stoked, the government tried to talk down the situation.

A Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine spokesperson said: “The paper referred to was part of a deliberative process. It is one of a number of modelling documents considered by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine and is not a final policy decision.

If there is a cull scheme, it needs to be voluntary.

“As part of the normal work of government departments, various options for policy implementation are regularly considered.”

Figures suggest 0.45 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions could be saved for every 100,000 dairy cows cut, but It is yet unclear how farmers will be paid for reducing their stock numbers.

The spokesperson added: “The government is fully committed to the

Agriculture has been blamed for 37.5 percent of GHG emissions in Ireland, but ag advocates are urging a voluntary approach to any culling.

long-term viability of the Irish sector including our farm families who are the bedrock of the industry. It is a sector that is the jewel in the crown of our overall agri-food sector. We will ensure that the sector is put on a firm footing for this and subsequent generations.

“The dairy sector already displays huge sustainability credentials, and we are now stepping this ambition forward. Government is focused on providing voluntary, financially attractive options for farmers which includes diversification.” •

CHRYSEID MODDERMAN | University of Minnesota Extension

ABOVE

The ideal stockpile location is in a flat area and out of the way.

On-farm manure stockpiling doesn’t need to be complicated, but there are a few important things to keep in mind.

As in real estate, it’s all about location, location, location. The ideal stockpile location is out of the way, can be accessed with hauling equipment, and will not lead to runoff into sensitive features.

A flat area, outside of areas that flood, with a non-permeable base to avoid leaching is best. Also, try to be considerate of your down-wind neighbors; a colleague recently told me his neighbor is building a “Mt. Vesuvius of Crap” too close to his house.

Clean water from rain, roofs, or uphill areas should not be allowed to pool around or run through a manure stockpile because any water that comes in contact with the manure will carry away pollutants. Soil berms may be built to divert rain and uphill water, and gutters and downspouts can be added to barns and buildings to divert water.

Once you have the perfect location picked out, it’s time to think about what the storage area will look like. First, to determine how much space is needed, ask yourself the following questions:

• How many animals will contribute to the manure stockpile?

• How much, and what kind of bedding will be in the manure?

• How long will the stockpile remain before being hauled away?

Let’s say you’re a horse owner. With manure and bedding, a 1000 lb. horse can produce 60 to 70 lbs. of waste per day, occupying around 2.4 cubic feet.

Say you have five horses that each weigh 1,100 pounds. That’s 5,500 pounds total (5 x 1,100). And you haul away your manure twice per year, once in the spring and again in the fall.

You know that an average of 2.4 cubic feet of manure is produced each day per 1000-pound horse. So how much space will you need for manure storage?

2.4 cubic ft x (5500 lb / 1000 lb) x 365 days = 4,818 cubic ft per year

But, you haul manure twice per year, so you really only need storage for half of a year (182.5 days).

2.4 cubic ft x (5500 lb / 1000 lb) x 182.5 days = 2,409 cubic ft needed.

So does that mean you should build a storage pad that is exactly 2,409 cubic feet? No.

These calculations were based on averages to give you an idea of the size needed.

Actual space allotted for storage should be larger than the calculated value to account for variability.

For one, you will likely not haul the manure away at exactly 182.5 days, and you need to ensure that you’ll have enough storage if it is a long winter.

And the actual manure and soiled bedding might vary based on the horse or bedding type.

It’s always best to err on the side of having too much space for manure, rather than cutting it close. That way, if you change bedding or add animals, you won’t need to expand your storage size. •

The washer removes soil from the front and internal compartments of the screen to keep operating capacity at a maximum without sacrificing water quality.

Dave Styer of Alfalawn Farm in Wisconsin has been using the GEA SlopeScreen on his dairy farm for 7 years. After years of manually cleaning his separator system with a pressure washer, he transitioned to an automated circular spray bar system which ran every two hours. He still wasn’t satisfied with the job that was doing and was looking for something better. That’s when he discovered the new OptiClean automated cleaning system from GEA, which he’s been using for almost a year. Here’s what Dave had to say about it:

How has adding the OptiClean changed your cleaning process?

It’s a very thorough cleaning system. I can notice a substantial difference when it’s done cleaning — the amount of material that’s going through the screen and separating is much higher. Right now, we’re running it four times a day.

How does it compare to your previous system?

It is a cleaner washing system. With our other system, we’d get a lot of debris that’d blow off the screen onto the outside edges. Because of the shielding on the OptiClean system, it doesn’t make a mess.

How is it helping your dairy overall?

Our flume system operates on good water quality — the cleaner the water is, the better it performs. OptiClean helps increase the performance of our flume system by improving the water quality.

What’s your favorite feature?

I don’t have to worry about it — it takes care of itself.