Antibiotic resistance

The key role of manure management | 10

Looking forward to fall

The dos and don’ts of autumn application | 16

Storage matters

What’s the best option for you? | 20

July/August 2021

Antibiotic resistance

The key role of manure management | 10

Looking forward to fall

The dos and don’ts of autumn application | 16

Storage matters

What’s the best option for you? | 20

July/August 2021

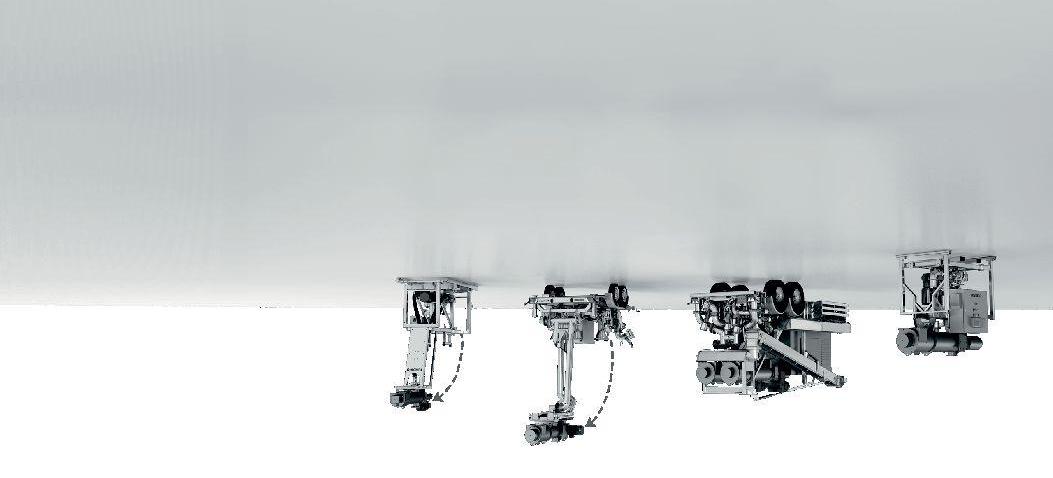

TURNING

SEPARATOR

•

•

Fan produces bedding material with a dry matter content of up to 38% in solids.

Timing is everything

Can you pinpoint the exact moment at which you’re supposed to apply manure that will result in the smallest nutrient loss?

Overcoming ‘superbugs’

New study looks at how manure management can tackle antibiotic resistance in livestock.

BY MADELEINE BAERG

Fall application fundamentals

Experts weigh in on how to know when the perfect time is for post-harvest application, and how to do it right

BY JIM TIMLICK

Storage solutions

Not all systems are created equal. Here’s what you need to know about these investments.

BY J.P. ANTONACCI

In manure management, there is indisputable science, chemistry and economics at play. However, the beautiful thing about those elements is that they are always evolving. Every year, every quarter, every day, we discover something new that enhances our practice. That’s why one of the most valuable traits in agriculture is openness to new ideas. Another trait that’s highly desirable: flexibility. Together, along with curiosity and willingness to adapt, those traits are as invaluable as manure itself.

It’s hard to be flexible if you don’t know what’s out there and what’s to come. That’s why when we moved the North American Manure Expo online this year, we made sure to not skimp on any of the popular elements from years past, including education sessions and equipment demos.

Education sessions include a trio of lectures on compaction –including the importance of avoiding it, as well as mitigation and recovery – and a session on real, actionable things farmers can do to help reduce

dollar. It’s why we, as the providers of informational resources, must ensure at all times that our content is current and relevant, yet innovative and forward-thinking. The ideal educational event – and magazine –is a mix of both.

In this issue, we have the ever-relevant and timely matter of seasonal application, as well as discussions on the perennial issue of timing – how that can be used to mitigate nitrogen losses and generate the most return on crops. We answer age-old questions on storage – how to choose the right solution for you, how to factor in finances and more.

But we also highlight the innovators – like the team at Iowa State University that is currently studying the link between manure management and antibiotic resistance. As our world becomes more challenging and unpredictable, it is important that we look to the new innovations to find solutions to keep stock healthy – and business equally healthy.

“We must ensure at all times that our content is current, yet forward-thinking.”

greenhouse gas emissions. It does us no good to pretend that big problems – like compaction, extreme weather events, or GHG emissions – don’t exist. Instead, we learn how to work around them, work with them and work to overcome them.

Working in ag is tough; one has to constantly re-educate and often must do it on their own time and

We’ve all demonstrated flexibility over the last year, whether it’s the flexibility to change up a business model or to move an event online. As we learn new information about how to best store, apply or manage manure, it is imperative to demonstrate the same level of flexibility – for the stock, for the business and for the future.•

The Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy has awarded Vermont’s Goodrich Farm with the 2021 Outstanding Dairy Farm Sustainability Award. The farm’s anaerobic digester (the result of a partnership with Vanguard Renewables, Middlebury College and Vermont Gas Systems) produces 180,000 Mcf of renewable natural gas and features the state’s firstever phosphorus removal system, which protects the Lake Champlain watershed.

The digester was originally a solution to two of the farm’s biggest business challenges – the volatility of the broader dairy industry, as well as scrutiny regarding its environmental impact, according to farm owner Chase Goodrich.

“Hosting the anaerobic digester diversifies our income, improves our carbon footprint while protecting water quality and makes us better neighbors, farmers and animal owners.”

A June cabinet shuffle by Ontario Premier Doug Ford saw a number of high-profile moves for ministers such as Rod Phillips and Merrilee Fullerton. One other move included Ernie Hardeman, the now former minister of agriculture, food and rural affairs. Hardeman was first elected to the legislature in 1995 and has held various minister, associate minister and critic positions. He first

served as minister of agriculture, food and rural affairs from 1999 to 2001.

Now in his former position is longtime MPP Lisa Thompson, who represents the constituency of HuronBruce. Thompson is no stranger to both Queen’s Park and the agriculture sector. She is currently serving her third consecutive term as MPP and is a graduate of the University of Guelph, as well as an alumnus

of the Class 6 of the Advanced Agricultural Leadership Program and the George Morris Executive Leadership Program.

Prior to entering politics, she served as the general manager of the Ontario Dairy Goat Cooperative (ODGC), Ontario 4-H Foundation chair and vice-chair of Ontario Agri-Food Education Inc.

The Ontario Federation of Agriculture issued a

12% 4.5

statement thanking Hardeman for his work on the file and welcoming Thompson to the position. “We engaged regularly with Minister Hardeman over the past few years and wholeheartedly appreciate his passion for agriculture and his desire to see our dynamic industry grow, innovate and move forward,” said Peggy Brekveld, OFA president, in a statement.

Amount of feces and urine, in pounds, a mature dairy cow can generate per day.

50-100 120

Minimum separation, in feet, manure storage should be from a property line.*

Average percentage of as-excreted solid content in a mature daily cow’s daily dumping.

15 3 6 1999

Amount of manure, in tons, a 100-cow herd on half-time pasture would accumulate every day in confinement, including milk wash wastes.

Minimum number of months manure should be stored.**

Maximum number of months manure should be stored.**

*ON-FARM COMPOSTING HANDBOOK, NRAES 54, 1992. PLEASE CHECK ON LOCAL STANDARDS **RUTGERS UNIVERSITY.

Number of meters any permanent manure storage must be from a drilled well in Ontario.

Year that North Carolina banned the construction of new manure lagoons due to overflows and health concerns.

Gleise M. Silva has been named as the first Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) Hays Chair in Beef Production Systems at the University of Alberta.

Silva, a native of Recife, Brazil, has moved to the Prairies for the first time to work with beef producers, translating her and colleagues’ research on cow-calf production into practical advice. The position is funded by the BCRC and the Hays family with additional support by McDonald’s Restaurants of Canada and Cargill. The position is guaranteed for 10 years with responsibilities

in teaching, research and extension and will be housed in the U of A’s Faculty of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences. Her work will focus on research that helps producers save money, maintain forage

With the fiscal year 2022 Georgia budget now signed off on, the University of Georgia has officially secured a commitment of $21.7 million for the construction of phase one of a new Poultry Science Complex in Athens.

The project will significantly increase the size of the department’s existing facilities, adding instructional and lab space, providing new facilities and helping attract more researchers.

The labs will allow UGA to add production courses and demonstrations, as well as field-learning exercises. It will also provide meaningful community connection by allowing UGA to expand its youth programs including FFA and 4-H.

“The new building will feature facilities and equipment to provide for advanced research to keep Georgia at the forefront of forwardthinking, relevant poultry research, advancing its UGA Cooperative Extension and outreach programs,” said Todd Applegate, head of the department of Poultry Science in a statement. “This will keep staff on the cutting-edge to ensure that industry and government entities increasingly seek them out to address research questions. It will also strategically provide UGA with a competitive advantage in terms of attracting extramural funding to lead innovation to solve grand challenges facing the poultry sector.”

He added, “The demand for poultry continues to grow with each new generation and the University of Georgia is committed to attracting the best and the brightest, and developing them into future leaders.”

lands and ensure an overall advancement of the Canadian beef industry, particularly in the area of sustainable production. She will explore ways to responsibly produce the best beef cattle and protect grasslands, with a goal of

advancing the economic, environmental and social sustainability of the industry. For example, she will focus on reducing the cost of feeding beef cattle during Canadian winters.

“[Producers] are the ones working hard for us from Monday to Sunday,” said Silva in a statement. “I want to help them get the most out of their production systems… I want my research to actually reach the people who need it the most.”

Silva’s PhD focuses on environmental and dietinduced stress in cattle, and on potential solutions to make cattle healthier and more efficient for the producer.

The Canadian Animal Health Institute has awarded its annual Industry Leadership to Dr. Mary Jane Ireland.

Ireland is executive director of the Animal Health Directorate and deputy chief veterinary officer at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. The award was presented to Ireland for her influence in the industry and her streamlining of key processes at the Canadian Centre for Veterinary Biologics and the Animal Feed Division.

“Mary Jane’s expertise and leadership, coupled with her unique ability to understand both industry and government perspectives, have allowed her to champion innovative and risk-based approaches to meet the unique

challenges of the Canadian animal health industry,” said Dr. Catherine Filejski, CAHI president and CEO.

“She is recognized and wellrespected internationally for her innovative attitude, and her commitment to a high quality regulatory system to ensure a safe food supply for Canadians, support our export markets, and uphold animal welfare by ensuring the health of our pets and livestock through better access to veterinary products.”

Initiatives under her leadership include the implementation of simultaneous veterinary pharmaceutical reviews through the Canada-U.S. Regulatory Cooperation Council, partaking in joint veterinary pharmaceutical reviews with New Zealand and Australia, and others.

Innovators continue to find ways to use manure for good in the quest for greater sustainability. Fertilizer production company Van Iperen International and Pure Green Agriculture have begun operations at a new Netherlands-based factory to produce nitrates from manure. The aim is to reduce nitrogen while producing sustainable and organic liquid nitrate fertilizers. Pure Green’s Ammonium Recovery Technology (ART) and Ammonium Inversion Reactor (AIR) will capture nitrogen in the form of ammonia from manure and agricultural waste streams, and then transform it into sustainable fertilizers under greenSwitch, the company’s end-to-end industrial-scale process.

Phil van Wakeren, CEO of Pure Green, said in a statement the company can remove 1,000 to 5,000 tons of nitrogen per year and reduce 180 to 900 tons emissions of nitrogen. “And on top [of that], we avoid the emission of 11,000 to 55,000 tons of CO2.”

David Vaillères has been named president of Valmetal Group, with his term effective for three years. He previously served as VP of sales and marketing for the company, a position he has held since 2013.

His appointment is supported by Dominic Vallières, VP of finance, IT and HR, and Eric Vaillères as VP of operations and R&D. The moves at the top come following a major change for Valmetal in February, which saw its three brands unified under the singular Valmetal name. The rebranding was the result of a series of acquisitions.

According to Valmetal, its board of directors also initiated a new strategic planning process, which led the board to reflect on various aspects of the company, therefore pushing it to position itself more as a group. Yvon Vallières, founder and chair of the board, said in a statement that the new structure “will allow the Group to grow in efficiency in order to adapt to the new realities of the agricultural market.”

“I am extremely grateful for the trust placed in me and I am convinced

that having an overview of all the Group’s strategies will be of great benefit,” said Vaillères in a statement. “My primary objective is to ensure that I go beyond expectations in achieving our objectives which aim, among other things, to become the industry benchmark in terms of customer experience.”

invests in health and safety tech for ag sector CYSA competition goes virtual

Canadian Young Speakers for Agriculture (CYSA) will hold its 2021 public speaking competition virtually. The competition is open to French or English speakers aged 11 to 24 with a passion for agriculture. Competitors are invited to upload their speeches to www.cysa.joca.ca prior to Sept. 30. The top-six entries in each category (junior and senior) will be chosen prior to the competition day and then invited to compete live via Zoom on Nov. 6.

Topics include:

• How a global pandemic changed Canadian agriculture – or has it?;

• What it means to be a woman in agriculture in 2021;

• Food waste, food security and food policy: What is agriculture’s/aquaculture’s role?;

• Canadian aquaculture: Opportunities in a growing industry; and

• Does a changing climate mean opportunities or headaches for Canadian agriculture?

Ontario is launching a new cost-share intake as part of a $25.5 million program to increase the adoption of technology to enhance health and safety in the agri-food sector.

The Agri-tech Innovation Program, valued at $22 million, is a cost-sharing program to help farm and processing operations adopt new technologies in the interest of worker health and safety. Ernie Hardeman, outgoing minister of agriculture, food and rural affairs, said in a statement that the investment is “a significant step forward” to help the sector address pandemic challenges while also positioning the sector for future growth.

The program is aimed at technologies that enhance protection of workers against COVID-19, lead to increased business efficiency and productivity and help build the sector’s resilience. Examples of advanced technologies include optical grading and sorting systems in vegetable processing or automated, robotic vineyard pruning robots.

Peggy Brekveld (pictured left), president of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture, added, “Technology and modern equipment make today’s farms more efficient and safer – both for people and the environment… [The funding] will enable investments in new processes and state-of-the-art equipment.”

Iowa State University will work to determine how manure management strategies can lead to healthier herds – and much more.

BY MADELEINE BAERG

According to the World Health Organization, antimicrobial resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development today. A growing number of infections in humans – from pneumonia to tuberculosis, and from gonorrhoea to salmonellosis – are becoming increasingly difficult to manage because microbes are overcoming our available antibiotic options.

The finger of blame is quite regularly pointed in animal agriculture’s direction, with concerns that the land application of manure from animals treated with antibiotics is a cause of increased antibiotic resistance. Yet, agriculture’s role in resistance development is still not well understood.

A new study from ISU aims to find answers to some major gaps in knowledge about antibiotic resistance development and spread, while also

ABOVE

coming up with some practical – and feasible – resistance-fighting manure management recommendations.

“We use a lot of antibiotics in agriculture to treat animals and in clinical settings to treat humans. The use is necessitated by good causes: we use antibiotics to prevent death and sickness, and to produce food. But we have become increasingly reliant on them, and we’re seeing them become less and less effective,” says the study’s lead researcher, Adina Howe. “What we don’t know is why. Where is the resistance coming from? Is the resistance we’re seeing in animals related to what we’re seeing in hospitals? And is antibiotic usage in agriculture a cause for concern for human health?”

Despite the risks associated with antibiotic resistance, these questions don’t yet have answers.

“We have evidence that this is a concern that is definitely worth looking into, but we have not

A new study, funded for four years, will help determine the impact of manure management strategies on antibiotic resistance.

yet demonstrated a direct link between agricultural and clinical resistance,” Howe says. “This research is novel, especially looking at all the interconnected parts of humans to animals to the environment. Our study is trying to fill the gaps and understand these linkages.”

The research team includes three scientists from the agricultural and biosystems engineering department at Iowa State University – Howe and colleagues Daniel Anderson and Michelle Soupir – as well as chemist Diana Aga from the University of Buffalo.

Together, the researchers aim to tackle three key areas of study. First, they hope to answer how resistant genes move in different pathways: whether the use of more or less antibiotics on the farm translates to higher or lower movement of resistant genes, and whether those specific genes transfer between ecosystems.

Second, they aim to determine whether specific manure management techniques – anaerobic digestion, composting, separating solids and liquids

– could minimize the movement of resistant bacteria.

Finally, they intend to learn how varying management techniques impact levels of antimicrobial resistance: for example, whether resistance actually develops during manure storage.

“Regulatory pressure is coming whether we want it or not.”

Antimicrobial resistance currently carries daunting costs: longer hospital stays, higher medical costs, increased suffering.

According to a 2019 report titled “When Antibiotics Fail” by the Council of Canadian Academies, approximately 26 percent of all bacterial infections reported in Canada in 2018 were resistant to first-line treatment. Additionally, 14,000 people died from those infections, with 5,400 of those deaths as a direct result of

the infection’s resistance to antibiotics.

Meanwhile, the Centre for Disease Control in the United States estimates that more than 2.8 million antibioticresistant infections occur every year in the U.S., leading to treatment costs of more than USD $4.6B annually and a death toll of more than 35,000. With costs so high, it’s no surprise that governments are eyeing regulation.

“Regulatory pressure is coming whether we want it or not. But this research isn’t government against farmers against hospitals. From my perspective, there’s no value in blame,” Howe says. “This kind of research allows all parties to be part of the discussion.”

In fact, agricultural producers are a critical partner in both the study and in developing solutions, she adds.

“This is very applied research. The intent is to find out what we can do together to manage manure practically, feasibly and effectively,” she says.

“We don’t have the data right now to understand where we can make the most impact. Without everyone’s help, it would be very difficult to come up with solutions.”

“Producers do seem to understand and support what we’re doing because they keep giving us their manure to work with,” Howe says.

The study, funded for four years, began this spring. The COVID-19 pandemic did place some pressure on the study,

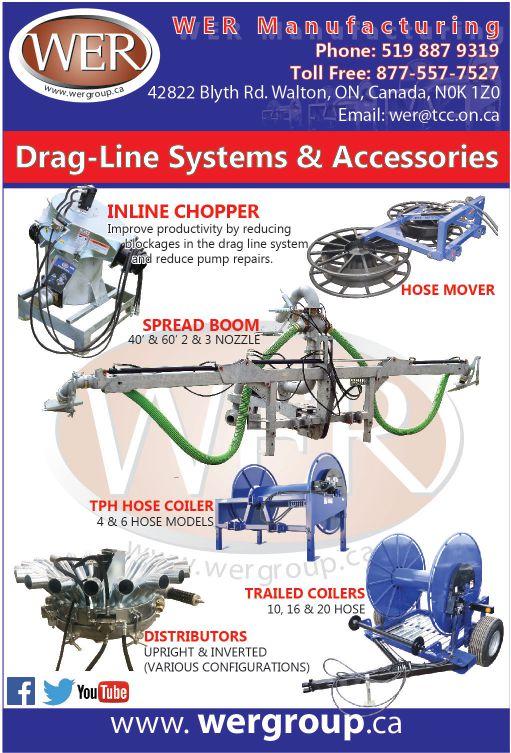

NEW! 3” SOLIDS HANDLING ON 6NHTC19 & 6819MPC PUMPS

Talk to your dealer about the superior solids handling and high head capabilities.

Hard Metal or White Iron materials available for abrasion resistance (MP Series)

Low head transfer to high head booster pumps

High efficiency — Lower HP required

Heavy duty construction — Low maintenance

50+ years’ experience in manure handling

CORNELL PUMP COMPANY www.cornellpump.com P: +1 (503) 653-0330 | F: +1 (503) 653-0338 manure@cornellpump.com

as recruiting students proved extremely difficult. Still, Howe thinks the research is on track. She hopes to have preliminary data available to share by this fall. As soon as the team starts determining results, they’ll include producers in ongoing conversation.

Howe intends to integrate results from the study into Iowa State’s manure management training program, publish findings in various scientific publications, and share information directly with farmers through field days.

Already, Howe says the team has shown preliminary evidence that anaerobic digestion appears to decrease some indicators of antimicrobial resistance. They intend to dig deeper into those findings, conduct side-by-side comparisons of anaerobic digestion versus composting versus liming, and expand their existing single-location trials in multiple geographic sites. For now, the work will be swine-specific, primarily because the team has extensive experience working with resistance in hogs.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very difficult issue, not only to mitigate, but also to research. Part of the issue is that researching the movement of resistant genes requires a challengingly wide field of view, including collaboration from experts in animal biology, microbiology, soil structure and chemistry, hydrology, and more.

The other challenge is that the specific source of resistance can be very difficult to determine because resistance can be passed from one bacterial strain to another, and even one generation to another.

“Even if you grow pigs to whom you never gave antibiotics, your pigs probably came from a mom that was given antibiotics. So, there’s a legacy effect: a transfer of antibiotic resistant bacteria,” Howe says..

Despite the challenges of the research, Howe is enthusiastic about the work and confident her team can make meaningful steps towards a better understanding of antimicrobial resistance’s mechanisms and its mitigation.

“I’m super excited to get rolling on this work. It has global impact; it has local impact. It’s definitely a place we want to make a difference.” •

OCT. 19, 2021 12:00PM EDT

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

Register for a virtual mentorship event with some of the most influential leaders in Canadian agriculture.

This half-day virtual event will showcase select honourees and nominees of the IWCA program in a virtual mentorship format. Through roundtable-style sessions, panelists will share advice and real-life experiences on leadership, communication and balance working in agriculture.

JOHN LAUZON

Black Gold: Maximizing Manure Nutrient Utilization

CLAUDIA WAGNER-RIDDLE

Managing manure to reduce GHG emissions

ADRIAN GÜNTESPERGER, RICK

MARTENS, JOHN MOLENHUIS & DAN BRICK

Determining the real cost of handling manure – when to hire a custom applicator

CHERYL SKJOLAAS

Safe travels: Transporting Manure Safely

IAN MCDONALD & ALEX BARRIE

Compaction: The Problem

GLEN ARNOLD & LARRY BEARINGER

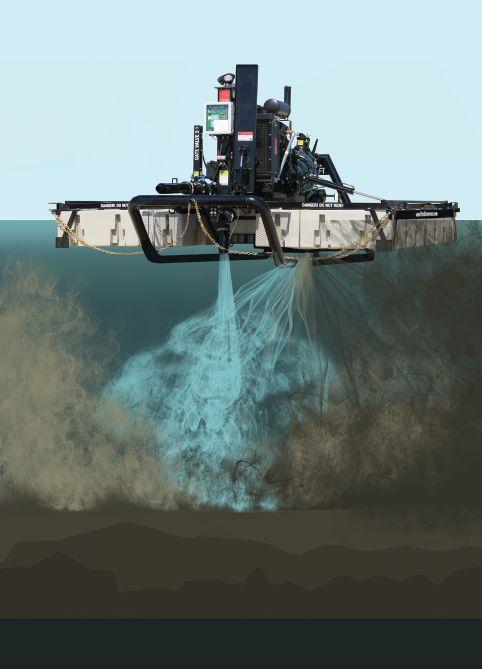

Maximizing growing season and in-crop manure application using drag hose systems

JULIA ROMAGNOLI, REBECCA

LARSON & FRANK WEBER

On-the-go tracking of applied nutrients

MERRIN MACRAE

Phosphorous and manure

IAN MCDONALD & JAKE KRAAYENBRINK

Compaction: Finding solutions

MEL LUYMES

Modifying purchased equipment to enhance performance

Post-harvest application is unique from other periods in the year. How can you make the most of it?

BY JIM TIMLICK

Despite how helpful manure is, it can also prove challenging to manage during weather shifts. Fall applications pose several specific challenges for farmers and custom manure applicators alike. When is the best time to apply manure postharvest? How warm or cool should the soil be when you are applying? Is a single application best or should you consider a split application? We spoke with several agricultural experts to get their advice on what growers should know about how and when to conduct fall applications. We also asked them to address some common myths about fall applications and what producers should be aware of regarding these misconceptions. Here’s what they had to say.

Even though most farmers won’t begin fall applications until at least September or even October, they can learn a lot about what may be required then during the summer.

Robb Meinen, a senior extension associate with Penn State University Extension, says if production turns out as expected come harvest, that likely means the nutrients that were applied to that field were properly utilized. However, in a scenario where something went wrong (such as a drought) and there was a decrease in expected production there could be residual nutrients left over for next year. In such a case, that means the grower might not need to use as much of a nutrient like phosphorus on their field in the fall and may be able to utilize it elsewhere.

Wet summer weather can also significantly change how or when fall applications occur, says to Erica Rogers, an environmental management educator at Michigan State University Extension. Rogers points to a particularly wet summer Michigan experienced a few years ago that delayed application until much later that fall and in some cases forced farmers to postpone application until the following spring. Such a scenario could very well play out again soon as weather patterns

appear to be trending in a more extreme direction.

“That’s definitely making a difference in planting and harvesting and fertilizer applications, whether that’s commercial fertilization or just manure,” she explains.

That’s why it’s important, Rogers says, for farmers to keep records of such trends in order to help them determine and adjust management practices so fertilizer can be applied most effectively in the fall.

A split application is hardly a new concept, but it’s one that seems to be gaining traction with a growing number of farmers.

How does a grower know when a split application is required? That’s a good question, says Brian Dougherty, a field agriculture engineer with Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. One way to tell whether a split application may be necessary, he says, is if you’ve historically used just a single fall application and seen a subsequent reduction in yield

Dougherty’s advice in such a case is to try backing off on your fall application rate and then come back in the spring to apply some side dressing such as liquid nitrogen.

The upside to a split application is that you are less likely to apply too much fertilizer and end up losing some of those valuable nutrients, says Meinen. Applying fertilizer at a lower rate in the fall, means nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus are more likely to stick around for next year’s crop, he adds.

Regardless of when or how you apply fall fertilizer, growers need to be aware of any relevant regulatory or safety requirements, which can vary from state to state and province to province.

Rogers advises farmers in the U.S. to familiarize themselves with best management practices – a set of recommendations designed to make economic and environmental sense and supported by the best science available.

Meinen says the onus is on growers and applicators to know what local regulations are and what they are required to do when it comes to fall applications, including application rates and setbacks in environmentally sensitive areas. That could include having a certain amount of crop residue or a cover crop in your fall management plan to assimilate nutrients applied to the field and holding

them there until spring.

Regardless of differences in regulations from region to region, safety concerns are pretty much the same where fall applications are concerned. Dougherty says one of the primary safety issues related to fall applications is potential gas buildup (particularly methane and hydrogen sulfide) when manure is being agitated or pumped out of a storage facility. He suggests producers use a well-ventilated area when they’re agitating, not to go into any confined spaces during pump out and keep an eye on their animals for any signs of stress. He also advises growers who are hauling their own manure to check with the Department of Motor Vehicles on axle weights and to make sure they have all the necessary lighting and slow-moving vehicle signage in place to reduce the risk of collisions with other vehicles.

All the knowledge in the world isn’t going to serve you well if you don’t have the right equipment to do the job.

Rogers says one of the most important pieces of equipment for applying fall fertilizer is a manure injector. Although it is more commonly associated with summer application, it still has a role to play in the fall by placing nutrients closer to the root zone where they can do the best job in boosting plant health. It also contributes to reducing loss of the manure nutrients through surface runoff during storm events and winter wind.

“By having equipment that allows you to work the nutrients into the soil and it’s not just surface supplied then you can keep those nutrients in place and you’re not as likely to lose them in runoff situations,” she explains.

Dougherty says another important tool to have on hand for fall applications is a gas monitor to ensure chemical compounds such as hydrogen sulfide don’t exceed recommended safety levels. He also encourages growers to have a manure testing kit on hand in the fall “so they know what they’re going to be applying or can at least calculate after the fact how much they put on.”

Perhaps the most important tool to have on-hand for fall applications isn’t really a tool at all, Meinen says. He recommends every grower have a nutrient or manure management plan and to adhere to it during their fall applications to ensure nutrients are being

placed in their field in a manner and location where they’ll do the most good.

Regardless of the volume of information available, some misconceptions regarding fall applications still exist.

One of the most common ones is that it doesn’t really matter when nitrogen is applied in the fall. That simply isn’t true, Dougherty says. He says growers should wait until soil temperatures have dropped to below 50 F (10 C) before applying any fall manure since that’s the point at which microbial activity in the soil starts to slow down. Applying any sooner means the microbes in the soil can start converting the nitrogen into nitrate form, which can then be easily leached through the soil and lost.

“We’ve got a comparison looking at early fall manure application when soils are still really warm versus late fall application… and we see a big yield difference. It’s about 40 bushels per acre,” he adds.

At one time, most growers believed fall fertilizer had to be applied before any cover crops could be planted. Meinen says many growers have now come to realize that isn’t necessarily true. In fact, an increasing number are now putting manure on top of established cover crops.

“People used to be worried if they drove over the cover crop that the cover crop stand would be harmed,” he explains. “That can happen, but we see more and more people placing cover crop seed immediately after fall harvest, for instance the silage chopper and grain drill may be in the field at the same time.

“If it’s already established and you do drive on it you are still usually better off because you have that extra week or two of cover crop growth which in the fall can really make a difference. If you get a really cold fall and you still haven’t gotten your cover crop in, but you’ve put manure on…you haven’t really gained as much.”

Another misconception about fall

applications is that you don’t really have to work fertilizer into the ground because nitrogen isn’t as likely to volatilize due to cooler soil temperatures. Rogers says that isn’t correct in many cases. “There is some research that shows the nitrogen doesn’t volatilize, but you are still at-risk for nutrient run-off, especially when it’s surface supplied and you get rain coming in or snow and it melts. It’s still best practice if you can work that manure or fertilize into the soil to help prevent runoff and volatilization of nitrogen.”

Come fall, many farmers’ thoughts turn to storage and how their storage system will cope through the cooler months.

Rogers says a rule of thumb is for growers to determine if their storage system has the capacity to withstand a 25year, 24-hour storm event that produces a maximum amount of precipitation. “Do you have a storage system that can hold six months of manure to make sure you can get through that winter season without having to apply manure?”

She also recommends keeping accurate records of animal head counts and note any increases and what they could mean for manure storage capacity. “I know it sounds like a no-brainer but it’s an important management check.”

Even if your capacity is sufficient, Dougherty recommends checking it in the fall to make sure it is in proper working order. That includes an inspection after it has been pumped out to make sure there are no cracks or leaks anywhere. Growers may even want to consider using a long-scoped inspection camera to make sure there are no cracks below the surface. In the case of outdoor lagoons, Dougherty suggests taking a walk around the perimeter to check for any animal burrows and fill them in as well as removing any vegetation or brush with a deep taproot. •

If you can’t handle the stress, get out of farming.

talk to someone who can help

It’s time to start changing the way we talk about farmers and farming. To recognize that just like anyone else, sometimes we might need a little help dealing with issues like stress, anxiety, and depression. That’s why the Do More Agriculture Foundation is here, ready to provide access to mental health resources like counselling, training and education, tailored specifically to the needs of Canadian farmers and their families.

The options are plentiful, but what’s the way to go for a modern farmer?

BY J.P. ANTONACCI

It’s a fact of life on every livestock farm – along with milk, wool, eggs or meat – that animals produce manure, and lots of it. More animals housed in one location means the amount of manure produced grows, therefore storing manure until it can be spread on fields or hauled away becomes a significant concern.

Farmers have several options when it comes to capturing manure and washwater to prevent nutrient loss and environmental degradation through runoff. Systems that manage liquid manure or slurry – which moves with the help of gravity, pumps and pipes – differ from those that handle solid manure.

“There are pros and cons to any type of system,” says Erin Cortus, an extension engineer at the University of Minnesota who works with livestock production systems. “It’s a question of ‘do we want to handle the manure mechanically or hydraulically?’”

On small farms, manure can be stockpiled under a tarp or three-sided structure, or composted with straw and organic waste until it is spread on the fields or hauled away. But with

the consolidation and expansion of livestock operations in recent decades, large-scale manure storage systems – such as deep pits under barns, open-air holding ponds and lagoons – have become more common, making the storage of massive quantities of manure a significant concern for farm operators.

Outdoor manure pits and lagoons may look similar from the air, but where they differ is what is happening under the surface. Pits – also known as holding ponds when filled with liquid manure or feedlots when stocked with solids – are meant solely for long-term storage, while manure inside a lagoon undergoes anaerobic respiration as microbes break down organic material.

Storing manure away from the barn improves indoor air quality for livestock and farm workers. But open-air storage systems are vulnerable to intense weather events, present more odor issues, and increase the farm’s footprint, typically resulting in higher emissions in summertime.

Lagoons are most often found in southern

states because the bacteria that break down manure cannot survive the cold northern climate. Farmers who use lagoons must take care not to overload them with too much manure and risk microbial system collapse.

“You’re essentially managing microbes,” Cortus explained. “You have to keep those microbes happy. If you overwhelm them with too fast of a feeding rate, they’re not going to digest the organic material and you’re going back to more of a storage system.”

As a result, she added, a lagoon’s storage capacity “is a lot less (than a manure pit) for the same amount of area.”

Due to geographical limitations and regulatory trends, holding ponds for liquid runoff are much more common than lagoons, says Justin Bonnema, a South Dakota-based agricultural engineer with the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Bonnema visits operations and gives technical advice to livestock operators about how to manage the waste products their farms produce.

“Far and away what we do the most is the holding pond,” he says.

Most holding ponds are made of earthen materials and lined with clay. Some have concrete bottoms or synthetic liners, with the occasional full concrete walled pit.

The earthen liners are not impermeable, but Bonnema says for systems designed to meet governmentmandated permeability limits, “the seepage amount is going to be way, way less” than uncontrolled runoff.

“The seepage amount is going to be way, way less than it would be if it was uncontrolled runoff,” he says.

At the other extreme, hurricanes and violent storms can see millions of liters of liquid manure jump the banks of holding ponds and lagoons and flood surrounding farmland and waterways, killing untold fish and polluting the water supply.

Monitoring the “integrity” of every storage system and making needed repairs immediately is essential to prevent ecological disasters, Cortus says, as is ensuring each system has the capacity to handle a sudden surge in precipitation and high winds.

“You always want to have room for a storm event,” she says. “Knowing where you could move manure in a short time frame if absolutely needed – that’s the second line of defense for a catastrophe.”

Holding ponds have markers half

to two-thirds of the way up the slope that indicate when the liquid or slurry should be pumped out to make more room.

“If you’re a foot from the marker, pump it down even so,” Bonnema says. “Because the more producers push that water level at or above the marker, the more likely it’d be that a big storm could overtop them.”

Some states, such as Iowa and Minnesota, have rules in place discouraging open manure storage out

of concerns over runoff and odour, while new lagoon construction was outlawed in North Carolina in 1999 after repeated overflows and subsequent environmental devastation.

While engineers are available to offer advice and state regulators provide some oversight through infrequent inspections, ultimately it is up to operators to follow operational guidelines, flag issues with aging lagoons or pits past their structural prime, and ensure their manure storage system is

able to withstand a major storm.

“Typically, if a producer manages their pond well, they shouldn’t have very much chance of that runout event, absent a very big storm,” Bonnema says.

Manure pits and lagoons can pose serious safety risks to farm workers. Anaerobic digestive fermentation – the process by which manure becomes fertilizer – generates methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide.

These highly toxic and potentially explosive gases displace the oxygen inside a confined storage area, and exposure can be harmful or even fatal. Workers are at heightened risk in the hot summer months and during agitation and pumping of the manure.

Tracey Erickson, dairy field specialist with South Dakota State University Extension, says pits should be continuously ventilated using a powered, explosion-proof system and covered with ventilated grating, with hazard signs

posted to discourage unauthorized entry.

Workers who must enter a manure pit should first test the air quality and ensure they are wearing a safety harness attached to a lifeline so their partner on the surface can rescue them should they lose consciousness. Workers should use a self-contained breathing apparatus and maintain constant auditory or visual contact with coworkers outside the pit.

Lagoons should be ringed with fencing and locked access gates to prevent people or animals from falling in and drowning. Erickson recommends each manure pump have rescue equipment such as a lifeline or flotation device attached.

Erickson says injury and death can be avoided if farm operators take all safety precautions and ensure workers are properly trained and equipped to minimize the risks inherent in manure storage. Speed should never trump safety, she adds.

Worries over worker safety and the environmental impact of holding pond and lagoon spills have a growing number of farmers opting to store manure in deep pits under their barns.

“In the beef world, we’ve seen an increase in the last five or 10 years of manure in deep pits under a building,” Bonnema says.

Cortus has noticed the same trend on cattle farms in Minnesota, where deep pit barns are already the most common storage system for swine manure. Putting rubber mats on the concrete slatted floor to protect cows’ feet made deep pit barns hospitable for finishing cattle, who have a longer lifespan than pigs.

While costly, Bonnema says deep pit barns have several advantages for longterm storage of manure and wash water.

“We do work with producers who are choosing to abandon outside lots and go to buildings to stop runoff,” he says.

“Buildings help capture more of the nutrient value and take much less space than an open feedlot. It’s maybe a 10 percent area required for the same number of cattle in terms of their housing.”

Keeping cows out of the elements in the winter and shaded from the hot summer sun is another bonus, Bonnema adds, while Cortus says having a smaller footprint for storage and producing more potent and nutrient-rich manure by blocking precipitation can help a farmer’s bottom line.

“From an agronomic perspective, that pays off,” she says.

However, having highly concentrated manure under the barn puts livestock and laborers at higher risk of exposure to potentially harmful gases, especially when the manure is agitated.

“You have ventilation systems, but you are going to have higher gas levels in the barn than you would compared to shorter-term storage,” Cortus says.

As one final point in favour of deep pits under completely slatted floors, farmers get a hand from gravity when it comes to moving manure from the barn into storage.

“The transfer happens automatically,” Cortus says.

When it comes to deciding what manure storage option is best for a particular operation, Cortus says local laws and regulations essentially spell out what is allowed for livestock farms with more than 1,000 head.

“It’s likely almost dictated by the rules or norms in an area for a given type of animal,” she says. “For larger operations, that’s really the starting point – what’s permitted by law? If it’s a smaller operation, you have a little bit more freedom to choose what you can do.”

But even that is not a hard and fast rule, as certain states have stringent requirements not just for concentrated animal feeding operations, known as CAFOs, but livestock farms of any size.

“In some states, if you have one goat you probably need a permit, but in other states, the rules don’t come into play until you have 1,000 animals,” Cortus says.

Farmers in South Dakota looking to expand past the 1,000-head threshold – which requires farms to fully contain manure, control runoff, and keep records for state inspection – often call Bonnema for advice.

“It can be a pretty big switch. Their level of management increases,” he says of containment systems that can involve a holding pond to catch runoff and a settling basin to capture solids.

“Of course, another big question: ‘What is it going to cost?’”

Some farmers are reluctant to make big changes because of the money they have already sunk into their existing manure management system.

“We see a lot of variety. Some operations are much more flexible than others,” Bonnema says.

“We’ve had producers pick up their entire feedlot and move it up the hill to another location. [Whereas] the next producer might not have easy options.”

Along with the return on investment expansion can bring, engineers like Bonnema remind farmers of the hidden future costs of maintaining the status quo – for example, keeping a low-lying storage area in an undesirable location may require an expensive pumping system to move the manure.

Bonnema says some producers who stay under 1,000 heads still choose to voluntarily implement a manure containment system to protect the health of nearby waterways.

‘A

Cortus and Bonnema both cite anaerobic digesters as a possible next frontier in manure management. “There is a rejuvenated push for digestion” spurred by government subsidies for biogas converted to renewable energy for the California market, Cortus says.

Proponents say they remove methane from the atmosphere, reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural

operations and turn a waste product into renewable energy.

But digesters are not without their detractors, including environmental groups who argue government subsidies for power generation from biogas enable the expansion of CAFOs and discourage the move to smaller, more environmentally sustainable farms.

Digesters only work with outdoor storage systems, since fresh manure has to move through the digester before it goes to storage. Deep pits under barns, therefore, are not ideal.

The technology is most often found on dairy CAFOs, but swine farmers are asking extension experts if digesters could be a fit for them as well. Cortus says farmers attracted by the idea of turning waste gas into profit should realize the work and cost involved.

“It’s a whole new level of management and a whole new type of management, so you almost need someone full-time dedicated to a digester,” says Cortus, noting some farms hire an outside company to install and manage their digester.

“It’s almost like it’s a whole other operation,” she says. •

BKT provides you tires that are reliable and safe, sturdy and durable, capable of combining traction and reduced soil compaction, comfort and high performance.

BKT: always with you, to get the most out of your agricultural equipment.

Nitrogen management is risk management – how can you capitalize and find the best application solution?

BY JULIENNE

ISAACS

What’s the best time to apply nitrogen in corn to boost yields while minimizing nutrient losses? In Minnesota, a succession of very wet autumns, even in the western part of the state where it’s historically been dry, have signalled a change in best management practices. With wetter conditions comes greater potential for N losses, and experts are re-evaluating the guidelines.

“In Minnesota the guidelines for N indicate that fall application of urea is an acceptable practice in the western part of the state – but we’ve seen over the last seven or eight years that conditions have gotten wetter,” says Fabián Fernández, a nutrient management specialist in the department of soil, water and climate at the University of Minnesota.

Fernández has spent the past five years conducting N application timing trials across the state, comparing fall versus spring applications of urea, anhydrous ammonia and ESN. In these trials,

Sidedressing

Fernández’ team found fall-applying any of these N sources resulted in greater losses compared to spring application – especially urea, even if urea is subsurface banded or applied with a nitrification inhibitor. “We’re working to revise some of these guidelines, because what we’ve seen from the research as well as from anecdotal evidence shows that it is a problem to apply urea in the fall,” he says.

“These studies are timely because anhydrous ammonia used to be the number one source of N in the state, but it’s disappearing from the marketplace in Minnesota, so some folks, especially in the southern part of the state, say, ‘We’ll continue our fall applications and just change from anhydrous to urea.’ But this is a big problem because you have more potential for N loss with urea than anhydrous” he says.

Averaged across continuous corn and cornsoy in Lamberton, Morris and Crookston, the researchers found that it took 29 additional

Stationary or Mobile Skids

Counter Bearing

+ No Auger Screen Contact

+ Multi Disc Technology

pounds of N per acre for fall versus spring application to produce nine bushels less yield, meaning it was doubly costly to producers to apply N in the fall.

The math is clear, says Fernández, and that’s why most producers are moving away from fall or early spring applications and focusing more on preplant and sidedress applications.

It’s always difficult for farmers to know which approach will work best on their operations, and farmers have to balance both nutrient requirements, nitrogen

loss, and logistical considerations such as timing and storage.

“Nitrogen management is risk management: it’s looking at your situation and figuring out what is the least likely to happen or most likely to happen and then figure out the best approach,” says Fernández.

So far, so promising. But if preplant and sidedress application is preferable to

fall application, how should livestock producers approach applying manure?

Melissa Wilson is an assistant professor and extension specialist in manure nutrient management and water quality at the University of Minnesota.

A few years ago, Wilson set out to assess producers’ options for applying swine manure as a sidedress treatment using a dragline hose system or a tanker truck. The applicator community was skeptical at first, she says.

“When I started with the program I told people I was going to sidedress manure and they told me it wouldn’t work, and then I came back with the data from the dragline hose system and it was fun to see people scratching their chins and saying, ‘That is interesting.’ We had a couple of really wet years – record breaking years. A lot of people were thinking we need to consider other methods,” she says.

The project seemed helpful from both the nutrient uptake standpoint and the environmental standpoint, says Wilson, as the region has been getting wetter and wetter in the fall. Sidedressing manure could offer producers another opportunity to apply as potential windows of application narrow.

Wilson is going into her fourth year of the project this summer, she says, with dragline hose-applied treatments on research farm plots as well as tankerapplied treatments on a local operation. The treatments compare swine manure to anhydrous ammonia and UAN.

In the first two years of the study, using a dragline hose system, the team found that liquid swine manure could be used as a sidedress N source when corn was at the V4 growth stage.

Wilson tested the dragline method in smaller research farm plots, where she opted to fill a six-inch hose with water, capped at both ends, pulled behind a tractor and dragged over about four rows of corn at a time in both directions along the row to assess the physical impacts on the growing corn.

• Barn Flush Pit

“From an applicators’ standpoint it works really well as long as the hose isn’t dragging a bunch of mud – so don’t do it in wet conditions,” says Wilson. “But the corn has to be pretty small. Beyond the V3, V4 stage it got a little iffy - but as long as the whole plant didn’t get ripped up it would grow back, because the growing point is below the soil before the V5 stage,” she adds.

Vancouver-based EverGen has officially acquired Fraser Valley Biogas in Abbotsford, BC.

The plant has been called “the original RNG project in Western Canada,” and is the first project to produce RNG into FortisBC’s network. The project was established in 2011 and uses a combination of anaerobic digestion and biogas upgrading to produce RNG. Its energy is driven primarily from agricultural waste from local dairy farms. It also produces organic liquid fertilizer for use on nearby farms.

Fraser Valley Biogas currently produces more than 80,000 gigaojoules of RNG per year, the estimated equivalent of heating 1,000 homes. EverGen plans to expand the project and increase RNG production by approximately 50 percent.

EverGen has an overall goal to develop infrastructure to support the province and country’s clean energy goals. Co-founder and CEO Chase Edgelow said in a statement there is a “significant gap” in infrastructure across Canada. Other EverGen projects include Net Zero Waste Abbotsford and Sea to Sky Soils in Pemberton.

Livestock producers know what it’s like to accumulate animal waste. But the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden also has quite a bit of dung to deal with.

The zoo generates roughly 1,000 tonnes of organic waste per year – and with its elephant program expected to expand, that number only looks to rise. Now, the zoo has partnered with Harp Renewables to turn that waste into something with far more benefits. With its new trial digestion unit up and running, the zoo is aiming to generate an end product that will become certified as fertilizer, which will also be available for the public to purchase – on top of being used in the community gardens in Avondale.

Unofficially, the product is named “Fionalizer,” after the zoo’s resident hippo, Fiona.

The zoo says this sort of technology is a Cincinnati first, although digester projects are increasingly common across farm and agriculture operations in the U.S.

More than 100 farmer veterans will be the lucky recipients of equipment thanks to a grant from the Farmer Veteran Fellowship Fund, as part of the Farmer Veteran Coalition program. The grant supports veterans in their early years of farming and ranching.

The Farmer Veteran Coalition directly purchases pieces of equipment that the farmer has identified as critical to their operations. The program has been ongoing for 11 years and helped more than 700 farmers with $3.5 million worth of equipment distributed. This class of recipients include representation in nearly 40 states and territories, including Guam. Of the more-than-100 recipients, 47 are female, which is double the percentages of female recipients compared to previous years. More than half of the veterans are from the U.S. Army, followed by 18 percent from the Marines, 17 percent Air Force, 11 percent Navy and two percent Coast Guard.

Equipment will be delivered to farms throughout the spring and early summer. Supplies include greenhouses and grow tents, walk-in coolers and cold storage units, milking systems, water filtrations and honey extractors.

The strength and reliability of Nitro Spreaders set the standard for nutrient management.

The hydraulically driven variable speed apron chains feed fastmoving beaters that ‘bite’ the load and throw it into the field with remarkable consistency.

AtheneVariableRateControlSystem

ISOBUSUTdisplaysspreadercontrolsand variablerate&overlap(ifavailableonterminal).

The addition of a variable rate control system, further reduces overhead, increases yields, and verifies field application rates.

When you’re ready to spread, we’re ready for duty.

For the second two years of the onfarm portion of the trial Wilson’s team is using a tanker instead of a dragline to assess sidedress applications at the V1, V4 and V7 growth stages. In the first two years of the trial when a dragline hose

was used, yields were similar regardless of nitrogen source.

In the third year, when a tanker was used, yields were lower, perhaps due to compaction. The fourth year of data will be important to judge yields.

The adoption of best management practices for N loss mitigation is still voluntary, but local advisory teams that include landowners, farmers, agronomists and extension specialists

like extension educator Taylor Becker are working to increase adoption. Becker, an educator with the University of Minnesota in St. Cloud, focuses her research on agricultural water quality protection.

- AGITATION MAKES THE DIFFERENCE

Center agitation system evenly blends nutrients

Better utilization of “waste” translates into less purchased fertilizer

ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND

Designed and constructed using bolted glass-fused-to-steel panels for secure storage and high corrosion resistance

Aboveground - minimizes the danger of run-o , leaching and groundwater contamination

Environment-friendly odor control - releases odors above ground level into higher air currents

•

She says farmers with sandy soil versus irrigated soil have more options when it comes to in-season N application: farmers can apply N up to the V12 stage. Farmers with fine-textured soil, or soil that isn’t well-drained, should stick to applying before V7. “It’s a hard thing to manage, so give yourself some grace,” she adds. Because every farm has unique conditions that impact N losses, farmers can develop their own best practices by doing their own trials.

“You can be in a field and your neighbor has more finely textured soil and that will completely change how the nitrogen moves in that system. That variability can be pretty stark. That’s one reason why doing replication is so important on the university side. That being said, you can’t account for everything [in research trials] – if your field is no-till or not, or if it’s continuous corn or rotated – these factors can be really important and affect N management. You can’t account for all of that variability, so that’s why on-farm trials are really important,” she says.

Fernández says farmers should keep it simple and collect at least two to three years of data to see how different application sources and methods work on their farms. “A lot of the responses farmers get are so related to specific conditions in their field. As long as studies are done correctly at the local level, there’s no substitute for that level of specificity,” he says. •

The University of Minnesota offers nitrogen fertilization guidelines online at https://extension.umn.edu/ crop-specific-needs/fertilizing-cornminnesota.

In addition, the UMN-developed “Nitrogen Smart” course, offered online, presents fundamentals for maximizing economic return while minimizing N losses. Producers can sign up here: https://extension.umn. edu/courses-and-events/nitrogensmart.

Farmers understand that animal waste is not waste at all, but a valuable (though smelly) nutrient source for plants. And aside from nutrients, it adds organic matter to the soil which, over time, improves water holding capacity and infiltration. You might say it’s some good “stuff”.

However, applying manure is not all rainbows and butterflies, and there are some limitations that make manure complicated. One of which is that the nutrient ratios are fixed. Unlike commercial fertilizers that can be mixed and adjusted to fit crop nutrient needs, manure is what it is. This is a problem because applying the necessary amount of one nutrient with manure inevitably over- or under-applies another nutrient; and over-application of nutrients can lead to runoff and nutrient pollution of waterways. For example, turkey manure is often guilty of having a bit too much phosphorus. When it’s applied at a rate to supply necessary nitrogen, phosphorus is overapplied. In some instances, turkey manure applied to meet the nitrogen needs of corn supplies over five times the phosphate needed; and fields that receive turkey litter each year often show high levels of phosphorus buildup.

You might be thinking, why is phosphorus buildup such a big deal? It’s not very mobile in the soil like nitrate, so why is it a problem if my soils have

Apply manure at a phosphorus-based rate. To prevent phosphorus buildup in soil, apply manure at a rate that fits the phosphorus needs of the crop. Of course, this will probably underapply nitrogen, so supplemental commercial nitrogen will be needed to fulfill the crop’s nitrogen needs.

Apply manure less-than-annually at a nitrogen-based rate. Another method to prevent phosphorus buildup is to apply at a rate that meets the nitrogen needs of the crop, and then refrain from manure applications in following years until the excess phosphorus has been depleted by crop uptake. This method works best with rotations that include crops with adequate phosphorus uptake. Otherwise, it might take many years before manure could be applied again. For example, in some pasture systems, turkey manure applied using this method would receive 15 years’ worth of phosphorus. And some regions have regulations stating that no more than five years’ worth of phosphorus can be applied at a time from manure.

Use feed containing phytase. Grains and oil seeds contain a type of phosphorus called phytate that must be broken down by the enzyme phytase to be digested by livestock.

“Unlike commercial fertilizers, the nutrient ratios are fixed.”

extra phosphorus? Well, you are correct in that phosphorus is fairly immobile compared to nitrate, but the idea of “banking” extra phosphorus is problematic when it never gets used. Continuously adding more phosphorus to soil will eventually lead to phosphorus runoff in either a dissolved or particulate form; which is not only an environmental threat, but a waste of valuable nutrients.

Excess phosphorus of just 20 to 50 ppb (that’s parts per billion, not million) in freshwater, such as a lake, can set off a chain of events that lead to low oxygen states, fish kills, and loss of habitat for aquatic life. And even though there are many other contributors to phosphorus pollution besides agriculture, manure managers still need to do their part to be good stewards of the environment.

Poultry and swine typically have low levels of natural phytase, so the enzyme is often added to their feed. Since phytase makes the phytate in turkey feed digestible, supplemental phosphorus is often unnecessary to meet turkey nutrition needs. That means that turkey manure from phytase-fed turkeys will contain less phosphorus than manure from turkeys that received no phytase and, therefore, needed supplemental phosphorus.

Managing manure can be tricky from both the livestock and crop side, and preventing phosphorus buildup in soils from turkey manure is no exception. By using the above information and tips, you will be better prepared to minimize phosphorus buildup while retaining the benefits of manure. Happy spreading! •

HARDOX® - EXTENDED SERVICE LIFE

Harder. Better. Stronger.

Don’t let sand wear you down.

HARDOX® - LESS DOWNTIME

HARDOX® - COMPONENTS MANUFACTURED IN HOUSE

HARDOX® - NEW PUMP HOUSING DESIGN FOR EASIER SERVICE

I WANT A PUMP THAT CAN STAND UP TO MILLIONS OF GALLONS BEFORE REPAIR.

GEA now offers the impeller, housing and cover plate constructed with Hardox® for all PTO pumps with 8” and 10” discharge. By choosing GEA Hardox®, we provide you with extended life, reduced downtime, and increased affordability all while keeping manufacturing in house.

• Covers manure more effectively than the competitors.

• Less maintenance required.

• Swiveling units can pivot without high side loads.

Toolbar Framework

• Designed for forward and rear tillage units to create 18” spacing.

• 6” or 8” plumbing available.

• 30’ - 40’ lengths available.