YOUR WORK STRENGTHENS THE RAISED BY A CANADIAN FARMER BRAND!

“Mary Brown’s partnership with the Raised by a Canadian Farmer brand has been hugely valuable to our business. Knowing there is one consistent, national animal care program that all farmers are certified on gives us confidence in promoting Canadian chicken and the high standards to which it is raised.”

- Fergus Byrne, Vice President, Procurement and Culinary, MB International Brands

by Brett Ruffell

As producers look to lower their environmental impact, this issue of Canadian

Poultry offers a valuable roadmap – from the fully integrated “poult-to-plate” model at Hayter’s Farm to the closed-loop, regenerative system at Lakeland Farms. Both operations, featured in our cover story “Green by example” (page 8), prove that sustainability is not a one-size-fits-all solution, but a mindset – one grounded in efficiency, animal welfare, and stewardship.

”Sustainability isn’t a finish line – it’s a process. And every step counts.”

For those wondering where to start, integration is a powerful first step. Reducing transportation between farm stages, as Hayter’s has done by managing everything from hatch to harvest on one site, doesn’t just lower emissions – it increases control over quality, food safety, and resource use.

If full vertical integration isn’t feasible, producers can still look at consolidating steps within their region or partnering more locally across the supply chain.

Smart barn technologies are another low-hanging fruit. Remote monitoring systems and AI-driven climate controls not only cut energy

costs but allow producers to act quickly when conditions change –improving bird health while conserving feed, water, and power.

Lakeland Farm’s investment in heat exchangers and climate-responsive misting systems shows how tech can reduce both animal stress and utility bills.

Soil health and nutrient recycling deserve more attention too. By composting litter and returning it to their fields, both featured farms are reducing reliance on synthetic inputs while building long-term fertility.

Even if you don’t grow your own feed, working with a trusted local compost facility or testing manure-based amendments can move your operation closer to a regenerative loop.

Packaging is often overlooked, but it matters. Hayter’s decision to switch to roll-stock packaging reduced their plastic footprint and extended product shelf life – proof that sustainability can pay off in quality and cost savings.

Finally, connect with the wider industry. Whether it’s joining NESTT (p. 16), learning from researchers repurposing food waste into feed (p. 20), or reevaluating chick handling practices (p. 12), progress often begins with conversation. Sustainability isn’t a finish line – it’s a process. And as the stories in this issue show, every step counts.

canadianpoultrymag.com

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Rep.

Tel: (416) 510-5113

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor Brett Ruffell

bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Brand Sales Manager

Ross Anderson randerson@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-925-7565

Account Coordinator

Julie Montgomery jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5163

Media Designer

Brooke Shaw

Group Publisher Michelle Bertholet mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5183

CEO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Subscription Rates

Canada - Single-copy $10.00

Canada – 1 Year $33.15

Canada – 2 years $56.61

Canada – 3 years $78.54 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $93.33 CDN

Foreign – 1 Year $105.57 CDN

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer

privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2025Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

The LUBING OptiCOOL evaporative cooling system with plastic pad is easy to clean, keeps my broilers cool, and allows my ventilation system to run more efficiently. Best thing is, my birds are bigger!

Randall Ruff - Ruff Acres

EFFICIENT AIR-FLOW

EFFECTIVE AND CONSISTENT COOLING

Keep your barn climate controlled and your flock cool and healthy with the LUBING OptiCOOL plastic evaporative cooling pad system, featuring an easy-to-clean design and long service life.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664-3811

Fax: (519) 664-3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Les Equipments Avipor Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263-6222

Fax: (450) 263-9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963-4795

Fax: (780) 963-5034

As Canadian agriculture works towards a goal of net zero emissions by 2050, Dr. Suresh Neethirajan has developed an innovative new tool to help poultry producers get an accurate picture of their on-farm emissions and identify ways to reduce them.

Neethirajan, an associate professor and research chair in the Faculty of Computer Science and the Faculty of Agriculture at Dalhousie University, took a unique approach to gather information on greenhouse gas emissions from the poultry industry. His goal? To provide practical actions to help producers reduce emissions.

Reliable, quantifiable methods to measure on-farm emissions are limited, making it difficult for producers to see how management changes could effectively reduce greenhouse gases (GHG). Neethirajan and his team saw an opportunity.

“We are using artificial intelligence and satellite data to get a much more precise, quantified measurement of emissions on poultry farms and processing facilities across Canada at an unprecedented resolution,” he says. “The beauty is that these are not vague estimations.”

Getting a read on regional variations Neethirajan and his team pioneered a benchmarking system with a first-in-the-world approach for the poultry industry. At the core, they accessed satellite-based atmospheric data from agencies including the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

They integrated satellite imagery with advanced machine learning/artificial intelligence to gather snapshots of atmospheric levels of methane and carbon dioxide from more than 1,300 poultry farms and processors across Canada, using data from 2011 to 2024. By correlating emission data with regional climate differences, the team was looking to uncover patterns and trends that could inform more targeted and effective mitigation strategies.

What they found was significant regional and seasonal variability in GHG emissions from poultry operations based on climate conditions and operational practices. Methane and CO2 emissions were highest in Ontario, Alberta, Quebec, and B.C., mirroring dense poultry farm and processor regions.

The impact of weather on emission levels was also very distinct. Methane emissions were higher during the summer and fall months when heat and precipitation drive more microbial activity in manure, and more emissions. In winter, microbes are inactive, and methane emissions go down.

“Our findings really highlight the need for seasonal emissions management strategies that account for local conditions,” he says. Those strategies to reduce overall emissions could include advanced manure management (e.g., composting or anaerobic digestion), optimized feed production, incorporating renewable energy options and improving overall feed efficiency.

By benchmarking GHG emissions in Canada, the research team was able to use artificial intelligence to “predict” farm practices that could reduce emissions based on local conditions mapped through satellite imagery.

“The AI component allowed us to run different management scenarios so we can now give actionable, measurable recommendations for how and where producers can work on reducing emissions that also take regional weather differences into account,” says Neethirajan.

Neethirajan knows that reducing emissions on poultry farms will require different activities for different farms, and will also be based on their geographic location. “There is no one size fits all solutions to climate change,” he says.

To make the info relatable and farm-specific, Neethirajan’s team is developing a new mapping app.

The free GHG Mapper app – now in testing – is expected this fall. Built with data from poultry groups across Canada, it shows farm-specific emissions and lets users simulate how changes to manure, feed, or energy use could reduce their footprint –based on their location and climate.

“There are significant differences in farm size, weather patterns and management practices across Canada, and we’ve incorporated all these variables into the GHG Mapper app to provide an effective tool to

help the industry reduce emissions,” says Neethirajan.

“This opens up new opportunities and incentives for producers to adopt sustainable practices that help bridge the gap between environmental stewardship and economic gain.”

The new app will offer several “what if” scenarios so producers can explore small,

actionable changes and their potential impact on reducing farm emissions:

• What if I cleaned the barns more often to improve air for the birds?

• What if I made some changes in ventilation maintenance to improve airflow?

• What if I considered seasonal variability for manure management?

• What if I look at barn insulation and heating systems for improved efficiency?

• What if I look at alternative feed ingredients to improve feed efficiency?

“Our approach provides a precise, actionable blueprint to help the Canadian poultry industry achieve significant reductions in methane and carbon dioxide emissions that are tailored to local conditions,” says Neethirajan.

How two Canadian poultry farms are embracing integration, innovation, and a full-circle approach to sustainability.

By Brett Ruffell

As the poultry industry responds to growing environmental challenges and consumer demand for transparency, a new generation of farmers is stepping up with bold, system-wide solutions. In this two-part profile, Canadian Poultry highlights two operations redefining what sustainability looks like in Canadian egg and turkey production.

With practices ranging from onfarm feed milling and precision composting to solar energy and smart barn tech, these farms are showing how innovation and stewardship can work hand in hand.

Hayter’s Farm has spent over 75 years producing high-quality turkey products with a clear focus on sustainability. As the only turkey farm in Canada that raises birds and processes products entirely on-site, the Dashwood, Ont.-based farm has created a rare “poult-to-plate” model.

This approach minimizes environmental impact while maximizing

control over animal welfare, food safety, and product quality.

This vertically integrated approach not only ensures product consistency but also reduces emissions, waste, and resource use across the entire production chain.

“At Hayter’s, everything happens here,” says Sean Maguire, CEO of Hayter’s Turkey Products. “We raise our birds from one day old, process them on-site, compost our litter and byproducts here, and even sell directly to customers through our farm store. That level of integration is key to both our environmental and financial sustainability.”

By eliminating the need to transport birds between separate facilities, Hayter’s significantly cuts fuel use and emissions.

Tractor-drawn flatbeds replace long-haul trucking, while on-site composting of litter and inedible byproducts reduces the volume of waste sent off-farm. Each link in the chain is optimized to work efficiently within the same footprint.

Modern barn technology plays a central role in reducing the farm’s environmental impact. Hayter’s uses the Rotem Platinum Plus system to remotely monitor barn temperatures, water, and feed consumption, helping the team maintain healthy and comfortable environments with precision.

Another tool, the PrevTech monitoring system, flags electrical issues

in real time – helping prevent equipment failure and fire risk while conserving energy. Automated weighing systems track bird growth and alert staff to any changes in feed or water consumption, enabling swift intervention that avoids unnecessary feed use and medical treatments.

“These technologies keep us proactive, not reactive,” says Maguire. “If something’s off, we know right away.”

Sustainability continues beyond the barn. On the processing side, Hayter’s has adopted the Multivac R 245 Thermoformer, which uses roll-stock packaging to reduce plastic waste. This switch has cut tray thickness by 30 per cent, and the machine’s modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) feature extends product shelf life –reducing spoilage and the need for preservatives or wasteful overproduction.

“We’re shipping less plastic across the country and reducing food waste,” Maguire explains. “That’s a win-win.”

Hayter’s antibiotic-use policy is grounded in restraint. “We don’t use antibiotics for digestive health or prevention,” says Maguire. “We only treat when necessary and under veterinary supervision.”

This measured approach not only supports animal health and public trust but also contributes to responsible stewardship of environmental microbiomes.

“Because

Frequent barn checks, natural ventilation, and close monitoring of bird behavior all ensure that welfare is prioritized. A healthy bird, Maguire emphasizes, is the foundation of a sustainable operation.

Hayter’s food safety certifications –including BRC and Halal – also align with its sustainability mission. BRC’s continuous improvement framework requires the team to regularly assess and refine their processes.

“These audits don’t just focus on safety,” Maguire explains. “They push us to be more efficient in how we use water, energy, and materials. It’s a mindset that keeps us moving forward.”

Looking ahead, Hayter’s is preparing for a major processing plant expansion that includes a more efficient water-chilling system. The farm currently uses about 14,000 gallons of water per day for chilling. With the

new cold-hold system, up to 20,000 gallons of water will be recirculated, filtered, and reused across multiple days – greatly reducing water use per bird while maintaining strict food safety standards. “We’re proving we can do more with less,” says Maguire.

Hayter’s sustainability mission also includes deep community engagement. From hosting the Turkey Ontario Tour to supporting local charities, the farm recognizes its responsibility as a land steward and employer in southwestern Ontario.

“These are the communities we live in, where our people work,” says Maguire. “It’s in our interest to grow sustainably and give back.”

One of the farm’s long-term sustainability goals is cultural as well as environmental: to make turkey a weekly staple on Canadian dinner tables.

By offering a growing variety of lean, protein-rich products in every-

day formats – like burgers, roasts, and filets – Hayter’s aims to reduce the need for long-term cold storage and seasonal surges in whole bird demand.

“The more often Canadians eat turkey, the more efficient we can be across the board,” says Maguire.

Hayter’s Farm has made sustainability more than a slogan – it’s built into the architecture of their operation. Through smart integration, technological innovation, and a commitment to responsible farming, this Dashwood-based turkey producer offers a compelling model of what sustainable poultry production can look like – today and in the years to come.

When Mike and Sarah Schroeder launched Lakeland Farms in Salmon Arm, B.C., their goal was to create a self-sufficient, environmentally conscious poultry operation rooted in organic principles. Seven years

Five ways Hayter’s Farm champions sustainability

1. Poult-to-Plate Integration: Raising, processing, and retailing all on-site reduces transportation emissions and improves efficiency.

2.

3. Waste Reduction: On-site composting and roll-stock packaging minimize plastic use and food waste.

4. Antibiotic Stewardship: Medications are used only when necessary, promoting responsible animal care and environmental health.

5. Water Efficiency: New chilling systems aim to recycle water, cutting daily usage while maintaining food safety standards.

later, they’ve built an integrated, closed-loop system that supports both bird health and long-term soil vitality.

Lakeland Farms began with organic grain production, but after entering B.C. Egg’s New Producer Program in 2017, the Schroeders quickly identified a gap: organic feed was being shipped hundreds of kilometres from the coast. Their solution was to build Lakeland Feed Inc., an on-site certified organic mill that not only supplies their own layers but also services other regional farms. Most feed ingredients are grown just metres away, drastically reducing transportation emissions and allowing for full control over nutrition.

This local approach extends into nutrient cycling. Manure from the hens is composted and blended with materials like sawdust and dairy pack, then customized for each field using soil and tissue tests. Cover crops and micronutrient balancing help regenerate the land and improve grain quality – which, in turn, supports the hens’ diets.

In 2024, the Schroeders expanded their barn and installed a suite of smart technologies, including heat exchangers, cooling pads, and AI-driven climate controls. The ESA-brand heat exchangers –

826 Nanticoke Creek Parkway, Jarvis, Ontario, N0A 1J0

Call us on: 519-587-2667

Or visit our website: www.mellerpoultry.ca

sourced secondhand – have proven especially valuable in cutting winter energy use. “We went through a -25°C stretch without needing much supplemental gas heat,” says Mike. He also reports significantly better air quality and reduced dust, both of which have improved flock health.

With full control of their feed, the Schroeders incorporate prebiotics, essential oils, and fiber-balanced rations to support gut health and reduce reliance on antibiotics. Their commercial feed clients also provide valuable performance data to refine nutrition strategies.

Whether it’s composting, cover cropping, or climate control, Lakeland Farms is guided by a systems-based approach to sustainability – one that regenerates land, supports healthy birds, and strengthens farm resilience.

With a major U.S. contract and growing research, this chick-first approach is poised to reshape broiler production. By

Treena Hein

Due to the many benefits of on-farm hatching systems in broiler farming, adoption is spreading. These systems obviously avoid transportation stress for chicks, boosting their welfare, but also health and performance parameters such as daily gain and breast meat yield.

Adoption in Europe – where the concept originated – has been growing over the last 20 years, and now, significant inroads are being made in North America. Perdue Farms, the world’s largest chicken producer, is purchasing two systems from Belgian-based NestBorn this year. It is the first NestBorn contract in North America. In Canada, about two years ago the Canadian Food Inspection Agency stopped regulating barns with on-farm hatching as hatcheries (requiring a hatchery licence) and they are now regulated by Chicken Farmers of Canada’s Animal Care Program and On Farm Food Safety Program, making the investment easier.

Perdue had been piloting a NestBorn machine over the last 18 months or so, gathering data and developing best practices for deep litter conditions, explains NestBorn’s General Manager Erik

Hoeven. “The data is quite promising, and now we are moving to a four-year contract from this summer, with two machines able to do much higher weekly volumes.” Perdue Farms Senior Communications Manager Bill See says, “we like the potential for this technology and are working through nuances.”

Hoeven also reports that “this contract has triggered a lot of attention in the U.S. and Canada. I have been in Canada twice during the past few months.”

review of the three systems

Here are the basic differences between NestBorn and the other two main commercial on-farm hatching systems, in terms of operation and biosecurity. But first, Dr. Julia Malchow of the Institute of Animal Welfare and Animal Husbandry in Germany points out that from an overall biosecurity perspective, any onfarm hatching system provides a way to continue chicken production if there are chick transport restrictions in place, which has happened recently in Germany, for example, because of avian influenza.

The NestBorn machine is loaded with egg trays and auto -

matically picks up and places individual eggs directly in the litter on the barn floor. From a biosecurity perspective, the machines are built to the same standards as all in-hatchery equipment, says Hoeven, and are hence able to be fully disinfected as needed.

Netherlands-based One2Born places specially designed egg trays on the barn floor, with trays recycled after use so only freshly made trays are used each time. “We don’t have plans in North America, but if there is interest, we will and can supply of course,” says company co-founder Frank de Louw. “We know the interest in the region is scaling up.”

Vencomatic Group, also based in the Netherlands, has had systems installed several years ago at two broiler operations in North America so far, at a farm in Quebec and at Groupe Westco in New Brunswick. Another installation in Quebec is pending, says Western Canada sales rep Tom Randall. (See sidebar for layer on-farm hatching system news from Big Dutchman.)

The Vencomatic system enables the hatchery setter trays to be suspended at different heights to capture the best airflow and temperature before the trays are lowered for hatching. Westco agrologist Marco Volpé notes that it’s better to keep eggs a bit

cooler than too warm. “A bit colder might slow the hatch time but overheating will be more harmful,” he says. “It will affect your hatch and chick quality. Avoid any airflow coming from heaters because those egg too close to it might not hatch.”

Quite a few studies have found that the immediate access to feed and water provided to chicks hatched in the broiler barn result in several health and performance parameters such as average daily gain and mortality. Some studies have also shown on-farm hatching provides better development of the chick digestive system.

This can result in less wet manure, the main cause of foot pad lesions.

Looking at the gut, Dr. Nadia Everaert at the Nutrition and Animal-Microbiota Ecosystems Laboratory (KU Leuven) in Belgium and colleagues published a study in February 2025 adding to the evidence that early broiler chick feeding can promote favorable gut development. They concluded that although the chicks in the study hatched on-farm showed only transient growth advantages, this practice “enhanced mucosal morphology and modulated immunity, indicating improved intestinal health.” NestBorn will release a paper on the microbiome of NestBorn chicks at the ICPD 2025 this summer in Belgium.

Everaert also notes that various studies in Europe that’s shown that on-farm hatching can reduce use of antibiotics throughout the life of the broiler compared to conventional chick delivery, but the impact of the farmer’s flock management skill must be carefully examined.

In a new published study, Malchow and her colleagues concluded that on-farm hatching (and ramped platform-enrichments) can result in improvement of certain aspects of bird welfare in chicks, “although in our study we did not find

advantages of on-farm hatching regarding anxiety or activity of chickens later in life.”

A 2024 study from France found that, for both on-farm and conventionally hatched chicks, including an adult hen as an enrichment had a negative impact on eventual broiler body weight.

In terms of both welfare and chick performance, Malchow and her colleagues have also found that on-farm hatched chickens have a lower body temperature during the fattening phase, and therefore, she says “on-farm hatching can increase the broiler’s ability to adopt to heat stress.” Fast-growing broilers are prone to heat stress, she notes, as they have a higher metabolism than laying hens and a corresponding higher body temperature.

The adoption rate for any new technology depends mainly on the benefits and the cost. It’s important to remember that the benefits of on-farm hatching in terms of chick welfare and performance are affected by the management skills of the individual farmer during the chick phase but also care of the eggs before they hatch and then throughout the flock cycle. This makes it difficult to establish when return on the investment of an on-farm hatching system would be reached on any specific farm.

See the full picture – Track and benchmark flock performance.

In November 2024, Big Dutchman introduced the Natura Life layer rearing concept, which was developed in close collaboration with the owners of Claessens-Jenniskens Pluimveebedrijven, a family farm in the Netherlands. This concept involves adding temporary hatching infrastructure into aviary housing so that hens have one environment for life, rather than first spending time in pullet housing.

Testing at the Claessens farm was carried out in March 2024 with one group of chicks being hatched in an aviary barn, with eggs delivered from the hatchery. For comparison, the same hatchery shipped chicks to the farm, which were placed as usual in a pullet rearing aviary.

The chicks hatched on-farm had above-average weight gain, fewer mortalities and achieved full laying potential very quickly. They also demonstrated stable laying performance that was slightly higher than in the control group. A spokesperson for Big Dutchman, notes that this system may be a niche product in the North America market, with how it will be utilized the most to be seen over time.

Turn data into action – Make informed decisions with real-time insights.

Stay proactive – Catch issues early and optimize egg production.

Volpé has also noted in the past that ROI mainly depends on how much automation is used, and there are many ways to look at ROI and many different types of on-farm hatching systems. Some European farmers manually place trays of eggs or individual eggs on the barn floor, or have created their own automated systems, and some purchase fully automated systems.

Malchow also notes that there are also additional costs with on-farm hatching, in pre-heating the barn before egg arrival and during the on-farm incubation period of two or three days, where if chicks are delivered, the barn is pre-heated for a shorter period and heating for egg incubation is obviously avoided. Malchow adds that the barn should be inspected during hatching to ensure optimal conditions, which presents another cost.

Everaert says some countries are examining whether eggshells need to be removed from the litter, and there may be countries where this is required, adding an additional task to on-farm hatching. However, there is no requirement from Chicken Farmers of Canada’s (CFC) in-farm hatching program to remove eggshells following hatch. This is because there are no food safety concerns and shells gradually break down into the litter. In addition, eggshells can also serve as a natural source of calcium and provide enrichment from an animal welfare perspective.

“These requirements were developed collaboratively with provincial boards and industry stakeholders and have been reviewed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and the National Farm Animal Care Council,” says CFC communications officer Chris Hofley.

“In addition to consulting with companies such as NestBorn and One2Born, we also engaged with the British Poultry Council and other organizations in the EU, none of whom identified shell removal as a concern or requirement. That said, this remains a developing area for CFC. Our requirements reflect the best available knowledge at this time, and we remain open to new information and research that may inform future updates.”

Everaert adds that there may also be additional added workload with on-farm hatching related to chick evaluation and culling, which would otherwise mostly be done at the hatchery.

“Overall, like with any new system, there’s going to be a learning process when

a farmer switches to on-farm hatching,” she concludes. “The first time through, you will learn a lot. There is enough evidence to show that this practice is better for the broiler’s health and welfare, but the management skill of the farmer is going to continue to play an important role.”

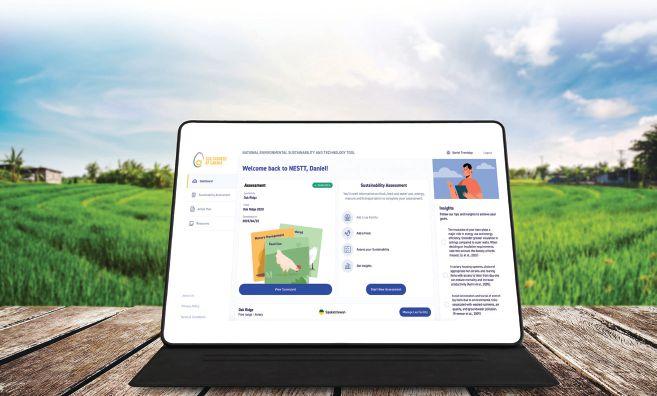

By Jane Robinson

Egg Farmers of Canada launched a new online tool in 2022 to help farmers assess the sustainability of their operations. NESTT –the National Environmental Sustainability and Technology Tool – was developed at the Food Systems PRISM Lab at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in collaboration with Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC).

NESTT provides a streamlined way for egg farmers to measure, monitor and manage the environmental impact of their farm based. The tool focuses on six key areas that impact environmental sustainability – hen productivity, feed and water use, manure management, on-farm energy use, spent hen management and mortality management.

Vivek Arulnathan knows the program inside and out. He’s a post-doctoral fellow at UBC and his PhD research was focussed on developing the models that underpin this decision support tool.

“The idea behind this project was to bring together farm-level flock information in a platform that farmers can easily access to help support every day decision making about sustainability,” says Arulnathan. “We look at the environmental impacts of a farm from a life cycle perspective. That means looking at farms as part of larger system and considering all of the resources and materials that go into producing eggs to provide a more holistic picture of environmental sustainability.”

NESTT was created specifically for egg farmers in Canada using a strategy called participatory design that includes end

users from the beginning to influence how the tool would work and what features to include. Farmer feedback, from early testers of the tool like Harley Siemens, helped Arulnathan streamline data collection so farmers wouldn’t have to spend a lot of time entering data.

Siemens was one of the egg farmers selected to beta test early versions of NESTT and now it’s part of his flock

management routine. “I’m a big numbers guy, so this program really interested me,” says Siemens, who operates three free run aviary farms with his family in Rosenort, Manitoba.

NESTT uses individual farm data to generate a report card to show how flock performance compares to industry bench-

Reducing GHG emissions

Supplying high-quality eggs

Canadian egg farmers are passionate about providing fresh, high-quality eggs while looking after their animals, communities and the environment. Find out more at e ggfarmers.ca/sustainability

Caring for our animals

Following rigorous standards

Supporting the future of our food system

NESTT was developed as part of an overall initiative for EFC – and Canadian agriculture as a whole – to help reach net zero emission targets by 2050. It’s an online tool designed to help farmers take an active role in reducing the environmental footprint of egg farming in Canada.

The program grew out of a study done by Dr. Nathan Pelletier, Egg Farmers of Canada Research Chair in Sustainability at the UBC, on behalf of EFC, to establish what the environmental impacts of egg production are in Canada. The goal was to ensure the right data was available from farms to support sustainability research for the sector – and identify specific technologies and strategies to improve on-farm sustainability.

By providing flock-by-flock insights, NESTT can be used to calculate a farm’s environment footprint, identify efficiencies, compare performance year over year, and see how adding green technologies can improve sustainability. Farmers can also opt to anonymously share their data with EFC and UBC to help improve the models that NESTT runs on and to support future sustainability research.

EFC estimates that nearly one in five farmers have used the NESTT assessment tool since it was fully launched. NESTT is available to all registered Canadian egg farmers at eggsustainability.ca.

marks for key sustainability measures. It’s designed to be a simple but meaningful way to give farmers specific feedback they can use to improve the overall sustainability of their operations.

At the end of each flock cycle, data is entered on the six categories and takes about 20-30 minutes if the data is readily available.

NESTT produces a scorecard for each flock with indicators for each category (rate of lay, feed conversion efficiency, etc.). Flock performance is categorized as low, medium or high, compared to industry averages. NESTT also provides farmers with more complex environmental indicators such as their carbon and water footprints.

Siemens uses the program routinely at the end of each flock to be able to benchmark performance against other flocks and see where they can make improvements in sustainability. “I look at it from two angles – how can I reduce my energy consumption, and how can I reduce my feed consumption?” says Siemens. “Those are all cost savings and also help reduce my carbon footprint.”

NESTT also provides tools and resources to help farmers look at potential changes in their operations, such as adopting green technologies, that would improve their sustainability and environmental footprint.

“When we talked to farmers before developing NESTT, they were particularly interested in the ability to benchmark their flock’s performance,” says Arulnathan. “We built in features where farmers can compare performance against their own flocks, and also against housing system-specific regional and national averages.”

Siemens understands how it might be a bit daunting for first-time users of NESTT if they aren’t used to having all of the data at hand that the tool runs on. Users can also opt to use industry averages for data points they don’t have that the tool needs to provide a report for a flock. “The more often you do it, the

“We built in features where farmers can compare performance against their own flocks, and also against housing system-specific

more you understand it,” he says.

One of the features Siemens really appreciates after reviewing a flock’s report card is the ability to change some inputs to see if he can get a better grade. It’s all part of the big picture, long-term view he takes as an egg farmer and a steward of land that might one day go to his young family.

“We want to make sure that we’re being conscious of every decision that we make on our farm and NESTT is a good check to see if we’re doing the right things,” says Siemens.

Continuous improvements

The idea from the start with NESTT was to be able to adapt and adjust

the tool. “We developed the tool by consulting with egg farmers, and we’re continuing to consult with farmers on updates,” says Arulnathan.

Users can expect updates to NESTT that shorten the amount of time it takes to input farm data, and more resources to help farmers interpret their report and learn about tools, technologies and practices to support sustainability.

“The most rewarding part of this project – as a sustainability scientist – was knowing that the work I was doing would actually help day-today decision making,” says Arulnathan. “Sustainability research in the agri-food space isn’t meaningful if it doesn’t help farmers make changes for better sustainability outcomes.”

Wired or wireless: The DOL 2400 alarm system can be connected to traditional landline or cell network for alarm notifications. Use any mobile GSM carrier. If you want to switch providers simply insert a new SIM card.

• 7" or 10" touchscreen

• Base units come configured as 10 inputs and outputs, expandable to 100. Connect multiple barns using master/slave mode using one dialer (less monthly fees)

• Phone call or text message (GSM units) notification options, as well as siren, flashing light or silent (burglary)

• Status reports via text message (GSM units) NO DATA OR INTERNET REQUIRED

• Can activate backup equipment in case of alarm (outputs)

• Self learning temperature curves

• Optional fingerprint scanner for additional security

• Sensors available: temperature, humidity, CO2, ammonia, dry contact, power failure

Researchers explore how food waste can be safely transformed into feed.

By Ronda Payne

Composting is a valuable tool for dealing with food-based organic matter, but is it always the best use? The reality is that food waste can have value. While composting is one way to create value, another approach may be in creating poultry feed.

Three studies conducted by researchers at two Canadian universities reviewed options for disposing and upcycling of food waste with focusing on offsetting costs by converting that waste into an input for other forms of food production.

Shaiyan Siddique, a PhD student in the Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies Sustainability Program at UBC and a member of UBC’s Food Systems PRISM Lab in Kelowna, conducted two related studies to review different options for converting food waste into viable feed.

“This study comprised of a literature review of cases from across the world that used the life cycle assessment approach to assess the environmental sustainability implications of food waste to animal feed valorization systems,” Siddique says of the first study.

He notes that life cycle assessment (LCA) is the “most popular approach” in the agrifood sector to consider environmental impacts and benefits of potential technologies.

This literature review included 27 research articles which reviewed a variety of food waste inputs (primarily mixed food waste from households, supermarkets, restaurants and other food service oper-

ations) and technologies to go from waste to feed. The stages of waste processing included steps like collection, sorting, grinding and drying.

“Amongst the key findings was that countries such as Japan and South Korea are already pioneers in food waste to feed valorization and that such technologies hold a lot of potential for similar application countries such as the US and Canada,” he says.

The second study used LCA to assess the environmental performance of a commercial-scale Pennsylvania facility which converts grocery food waste to laying hen feed. This valorization process is automated through the processes of sorting, grinding, cooking, centrifuging and drying.

“We found that including their product

in laying hen feed could reduce the carbon footprint of eggs by about 17 per cent,” Siddique says. “Researchers at North Carolina State University found that a five per cent inclusion rate best supported hen performance.”

The benefits are likely obvious: food waste in landfills is common and produces methane gas, and reducing reliance on commercially produced, traditional livestock feed. To fully appreciate the benefits of food waste valorized as poultry feed, environmental assessments of food waste to feed pathways should include the prevention of landfill emissions.

It certainly sounds like a win-win situation; however, despite the benefits, the challenges are far from insignificant. Dis-

ease transmission and energy consumption are two of the main hurdles to bringing food waste to the poultry barn.

“There is an obvious concern surrounding the spread of prion diseases in ruminants (such as mad cow disease) originating from feeding animal origin products,” he says.

While feeding animal-origin food waste to ruminants is banned in Canada and the European Union, it is commonly done with poultry.

“Studies have found no evidence of prion disease affecting non-ruminants such as poultry and pigs,” Siddique says.

“In fact, the inclusion of food wastes may actually improve the egg-laying performance of layer hens.”

But conventional feed supplementation is needed because the waste-converted feed is not complete enough for monogastric species like chickens

“More feeding trials are needed to optimize the inclusion rates for such feed inputs,” he says.

Energy use to convert food waste to

valorized feed through drying is a key hurdle. Siddique suggests central regions within cleaner energy grid areas like Vancouver, BC and Montreal, Quebec could be potential options for food waste valorization facilities with centralized transportation access.

“Drying the valorized feed product is an energy-intensive process and contributes most of the resource, environmental impacts of such a system,” he says.

Japan and South Korea may be considered pioneers in the valorization of food waste, but differing regulations and practices for poultry in other countries, like Canada, may hinder the application of information from these leaders. Because six of the seven commercial-scale studies reviewed are from Asia, functionality in North American farming may be challenging.

“Working with CFIA for regulatory approval should be undertaken by companies aiming to market valorized food waste-to-

Theoretically, making use of food waste in the poultry house is a viable solution. However, the review of existing studies about the practice found that more than half (56 per cent) made use of theoretical information. Other considerations include:

• Few studies reviewed had comparable processes and methods

• Technological needs and readiness information was not included in most studies

• Regulations in Asia (where six of the seven commercial-scale studies were conducted) are vastly different from those in North America

• Processes to valorization are energy-heavy with the drying process contributing up to 94 per cent of Global Warming Potential (GWP)

feed products,” Siddique says. “Farmers will need to communicate with their feed producers and feed nutritionists about sourcing and incorporating valorized food waste products into their feeds and monitoring their herds/flocks accordingly.”

He feels there is promise for food waste to poultry feed options in North America.

“We have already seen an example of it at commercial scale,” he says. “It is also important to understand people’s perspectives on food waste and raise awareness about the benefits of such a system to ensure a sustainable and viable business prospect.”

The third study is that of Xujie Li, a post-doctoral fellow at Dalhousie University. In potato processing regions like Atlantic Canada, potato peels are abundant. Together with his supervisors, associate professors, Stephanie Collins and Bruce Rathgeber, the study was able to consider how potato peel meal might be beneficial in poultry diets.

But peels also contain a decent nutrient profile. The scientist says there is 13 to 18 per cent crude protein, 40 to 50 per cent fibre and a significant amount of potassium, zinc and iron.

“We just want to investigate if the potato peel can be used as an alternative nutrient source without jeopardizing the health of the broilers,” Li says.

The researchers conducted two studies with different broiler producers each time. The first was straightforward with chicks getting either a 10 per cent inclusion of the dried potato peel or not getting the potato peel meal. Birds given the meal were also given a blend containing seven types of enzymes to aid in digestion, but the result was poor.

At the 10 per cent inclusion rate, the birds’ feed consumption dropped.

“They didn’t like it as much,” says Li. “The difference in body weight [compared to the control birds] was quite obvious.”

Enzymes and

“For the second study we asked for a different enzyme product,” he says. “Higher cellulase, galactanase and glucanase. If the birds are given something to help break down the increased fibre, it is beneficial.”

In this study, there were eight groups of

Regardless of whether potato peel meal is fed or not, early feeding during transport is a key driver of chick health and wellness. If potato peel meal is included, insights include:

• Enzymes are essential. Potato peel meal will have a negative impact without tools to break the fibre down.

• Negative impacts can include substandard weight gain, less food consumption and significantly larger gizzards and intestines.

• Including an enzyme more specific to potato peel saw great feed conversion and greater weight gains in birds when five percent potato peel meal was included in the feed.

chicks. The first four were: the control diet; five per cent potato peel meal inclusion in their diet; five per cent inclusion plus the new enzyme; and 10 per cent inclusion plus the enzyme. The fifth to eighth group were the same, but these chicks were given food and water during the transportation pro -

cess for approximately four hours.

The results were telling. Birds with standard starter feed during transport had lower (nearly half) corticosterone levels post-transport .

“Giving chicks the access to feed and water during the transportation improves the body weight and reduces the stress,” he says. “It has a long-lasting impact on the bird’s performance.”

Throughout the study, birds given the five per cent potato peel meal and enzyme treatment saw statistically higher feed conversion ratios than birds in other feed groups.

“Right now, we are having a positive outcome from the study,” Li says.

Easy

Waste not, want not. The practices of ancient farmers who tossed food scraps to chickens are getting a technological twist that has potential for how birds grow and thrive.

By Crystal Mackay

What’s good for people, poultry and the planet? It’s interesting how terms and issues come and go in and out of fashion in the poultry industry. I first heard the term “sustainable” while studying animal science at the University of Guelph in the 90s.

This makes sense, as a fundamental building block of the term came together in 1987 in “Our Common Future - The Brundtland Report.” The same report introduced the three pillars of environmental, social and economic sustainability, also known as ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance).

While those very principles are deeply rooted in our food system, I didn’t hear the term “sustainable” again for at least a decade after entering the workforce. ESG started showing up on agendas and corporate commitments in the last 10 years.

Once sustainability started coming up in conversation again, it almost always and inevitably was stopped in its tracks with the statement, “well, it depends how you define it.”

Fast-forward 20 years, and our agriculture and food system has moved well beyond the definition question block, and into the actions and communications era of sustainability.

I was working with Farm & Food Care and the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity to

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” ~

Gro Harlem Brundtland

model for the next time you have a conversation or an opportunity to share a message in person or online. You won’t always have the time or space to share all these but keep them in mind. Make them your own and select the one that will be most meaningful for the person you’re reaching.

Start with your why: “I’m passionate about feeding our country and … for the future.”

Do the right thing:> “We care for birds and the environment …”

Trusted assurance systems: “Our farm/business is part of … programs and follows … regulations.”

develop early efforts for earning public trust in food and farming. We recognized the need for a strategic model that helped solidify what was happening and what was missing. Together, with much input from farm, industry, government and academic leaders, we came up with a solid model for earning public trust, which still stands true today.

Picture three pillars: do the right thing; trusted assurance systems and regulations; and communications. Each pillar isn’t enough on its own. There is a need for coordination between all three pillars, a commitment to continuous

improvement, and research as the base to help inform and advance it all.

For example, for many years our sector focused on productivity improvements, but we didn’t communicate about it. Or in reverse, if we weren’t doing the right thing but just communicated about it, that would be greenwashing. Without assurance systems, we would have to say, “Trust us, we are doing great work!” Each pillar needs investment and resources, and collaboration to be most effective in the big picture.

Now, let’s think about sustainability and the public trust

Continuous improvement lens: “We work with people, birds, equipment, and Mother Nature. It’s never perfect, but we are always working on getting better.”

Make it real. Have an easy to share and understand example for each of the above that will make it real to the person you’re reaching.

Sustainability starts with you. Many people in our sector are hard-working subject matter experts who spend most of their time in the “do the right thing” pillar 365 days a year.

Remember the bigger picture and the importance of your credible voice to shine a light on what you’re doing and why that is good for people, poultry and the planet. For today and tomorrow.

S T R EN G T H EN Y OU R

B R OILE R F L OC K

Reduce mortality

Reduce E. coli associated lesions

Potential to reduce antibiotic use