Building

The European pellet market is huge, and someone has to keep track of all that product.

Pinnacle’s Burns Lake wood pellet plant emerges as Canada’s current largest.

Canada’s extreme temperatures should be considered when designing material handling systems.

New Tier 4 Interim engines are coming in 2011, bringing tighter emissions restrictions that may reduce performance.

Ontario’s long-term energy plan involves substituting natural gas for coal.

ntario is phasing out coal-fired power generation by the end of 2014.

The options are to close these plants prematurely (wasting taxpayer capital expenditure) or to use alternative fuel. The province touts its Green Energy Act as “…expediting the growth of clean, renewable sources of energy, like wind, solar, hydro, biomass, and biogas...” So why is it replacing coal with another fossil fuel?

The feasibility of converting the province’s four coal-fired power plants to biomass has been explored. Plans are under way to convert Atikokan to wood pellets, with some new infrastructure required, such as pellet storage facilities and modifications to pulverizers and burners. Although there was talk of converting the other plants to biomass, they now face different plans.

pellet producers from the rest of Canada are actively pursuing additional markets for their more than two million tonnes/year capacity because of depressed export markets.

On the cost side, it appears the plan is first to spend the money to put in natural gas infrastructure, and later, to consider the additional cost of replacing handling systems similar to those used for coal to co-fire biomass. This seems strange, given that a study of Nanticoke and Atikokan conversions, led by a University of Toronto researcher, estimated higher initial capital costs of conversion to natural gas than to 100% pellets. Why not convert to pellets and skip the additional cost of the natural gas intermediary stage?

Volume 14

Editor - Heather Hager (519) 429-3966 ext 261 hhager@annexweb.com

Group Publisher/Editorial Director- Scott Jamieson (519) 429-3966 ext 244 sjamieson@annexweb.com

Contributors - Bruce Barker, Colleen Cross, Gordon Murray, Reg Renner

Market Production Manager

Josée Crevier Ph: (514) 425-0025 Fax: (514) 425-0068 jcrevier@forestcommunications.com

National Sales Managers

Tim Tolton - ttolton@forestcommunications.com Ph: (514) 237-6614

Guy Fortin - gfortin@forestcommunications.com Ph: (514) 237-6615 Fax: (514) 425-0068

P.O. Box 51058 Pincourt, QC J7V 9T3

Western Sales Manager

Tim Shaddick - tootall1@shaw.ca 1660 West 75th Ave Vancouver, B.C. V6P 6G2 Ph: (604) 264-1158 Fax: (604) 264-1367

Production Artist - Kate Patchell

Canadian Biomass is published six times a year: February, April, June, August, October, and December.

Published and printed by Annex Publishing & Printing Inc.

Printed in Canada ISSN 0318-4277

The Ontario Ministry of Energy announced in late November 2010 that the Thunder Bay plant will convert to natural gas, requiring new infrastructure such as a pipeline to feed the boiler. Ontario’s LongTerm Energy Plan, released by the same Ministry on the same day, says that in addition to the Thunder Bay conversion, the remaining coal-fired units at Lambton and Nanticoke will be shuttered or possibly converted to natural gas “if required for system reliability.” It also says, “Ontario will continue to explore opportunities for cofiring of biomass with natural gas…” Decisions will depend on “the ability to bring in fuel supply and the cost of conversion.”

On the supply front, no large-scale pellet plants are producing yet in Ontario, partly because they’re still waiting on the province’s wood supply competition. However,

European utilities co-fire pellets with coal or use 100% biomass. An exception is Denmark-based Dong Energy’s Avedøre plant, which co-fires wood pellets with natural gas and oil. However, a 2009 document by Foster Wheeler researchers states, “The difficult properties of the biomass fuels and their ashes are better compensated when wood is co-fired with coal instead of oil or gas...”

The wisdom of eliminating coal and replacing it with natural gas in Ontario is far from clear. A more practical solution might be to co-fire coal with biomass until the plants are obsolete. The poor transparency of the decision-making process has left the northern Ontario forest industry, the Canadian pellet industry, Ontario taxpayers, and other affected stakeholders in the dark.

Heather Hager, Editor hhager@annexweb.com

Circulation

e-mail: cnixon@annexweb.com P.O. Box 51058 Pincourt, QC J7V 9T3

do not include applicable

Occasionally, Canadian Biomass magazine will mail information on behalf of industryrelated groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above..

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission ©2011 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

A new system in Quebec will allow the auction of up to 25% of timber from public forests for forestry stakeholders and new entrepreneurs, opening more doors for biomass opportunities not associated with tenure holders. Quebec is the second province, after British Columbia, to formally offer public forest timber for auction. A Wood Marketing Office (Bureau de mise en marché des bois) will be responsible for the sale of 20–25% of wood from public forests on the open market from April 2013. Auctions will begin this winter, with plans to sell about 200,000 cubic meters of wood in the southwest (Ottawa), south-central (Mauritius and Laurentides), and north-central (Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean) regions.

Ontario intends to introduce legislation in 2011 to modernize its forest tenure and pricing system. Under the proposed system, Local Forest Management Corporations would manage Crown forests and oversee local timber sales. Enhanced Shareholder Sustainable Forest Licences would comprise groups of mills and/or harvesters that manage Crown forests under Sustainable Forest Licences. The system is expected to create new opportunities and facilitate greater local and Aboriginal participation in the sector. The province made its first series of Wood Supply Offers under the Provincial Wood Supply Competitive Process in late November 2010, with proponents given 30 days to accept. The process con-

tinues, with further Wood Supply Offers and announcements to be made as details are worked out.

Changes to the way Nova Scotia’s forests are managed were proposed in December 2010 as six strategic directions to guide future forestry policy. “We will be meeting with the Mi’kmaq, small woodlot owner representatives, large mills, and nongovernment environmental organizations for input,” says John MacDonell, Nova Scotia’s minister of natural resources. The strategy’s aims include reducing clear-cutting, prohibiting whole-tree harvest, setting a province-wide annual allowable cut, and incorporating biomass harvest requirements in the Code of Forest Practice. The natural resources strategy is in the

final writing phase.

New Brunswick will be taking actions to strengthen and renew its forest industry based on recommendations developed at a November 2010 summit involving stakeholder groups, industry, First Nations, and government and non-governmental organizations. These include establishing wood sales and timber objectives for private and public forests, undertaking an assessment of forestry innovation outside of New Brunswick, and identifying future areas of transition such as using wood pellets in government buildings and exploring new technologies. A complete report on the summit is available at the Department of Natural Resources’ website.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has signalled its acceptance of the Pellet Fuels Institute (PFI) pellet standards program and supports its use for the New Source Performance Standard for Residential Wood Heaters. The PFI Standards Committee and staff continue to work on the implementation of the new standards program.

PFI is continuing discussions with the American Lumber Standards Committee

(ALSC) for the ALSC to serve as the program’s accreditation body. PFI and ALSC met in December 2010 and January 2011 for a formal review of the standards program documents in an effort to work out the final details of the program structure. Since then, the PFI Standards Committee has been editing program documents and finalizing the structure of the program. Standards program documents are available at www.pelletheat.org.

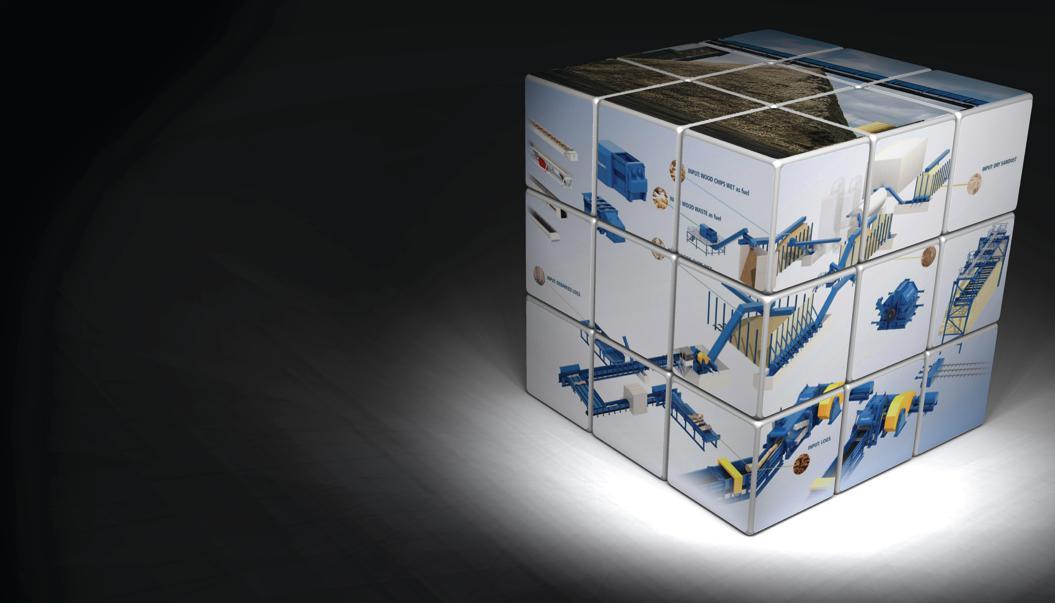

Quality pellets, guaranteed. For perfect pellets the entire production system must work together flawlessly. Buhler enables total process control by providing a complete process design package and key equipment for drying, grinding, pelleting, cooling, bagging and loading. This, combined with Buhler ’s integrated automation system, unrivaled after sales support and training provides a seamless solution, guaranteed.

The University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC) started its new biomassfired heating system in November 2010. The Nexterra gasification system will heat all of the university’s core buildings and reduce fossil fuel consumption by ~85%. It joins a campus wood pellet facility that has heated the forestry lab since 2009. UNBC shares the 2010 award for top campus sustainability project in North America with Harvard University.

Buhler Inc., 13105 12th Ave N., Plymouth, MN 55441, 763-847-9900 buhler.minneapolis@buhlergroup.com, www.buhlergroup.com

Innovations for a better world.

The government of Newfoundland and Labrador is focusing on two proposals to use fibre that was formerly allocated for the AbitibiBowater paper mill in Grand Falls-Windsor, reports the Farm Focus of Atlantic Canada. Both proposals are said to involve lumber and pellet production.

Maine Energy Systems has developed a fully pneumatic bulk pellet delivery truck. Made in co-operation with Trans Tech Industries of Brewer, Maine, and Tropper Maschinen Und Anlagen of Redlham, Austria, the pressurized tank delivers pellets into storage bins at less than four minutes/ton with minimal damage to the fuel.

It was a bad autumn for fires and explosions at North American pellet and bioenergy plants. Incidents were reported at pellet plants in Michigan, New Hampshire, and British Columbia, and at a hog fuel pile in Nova Scotia.

The European pellet market is huge, and someone has to keep track of all that product.

By Gordon

Murray

is now the world’s largest

wood pellet market, with annual consumption of more than 9 million tonnes. In 2010, Canada shipped about 1.1 million tonnes of wood pellets from British Columbia and about 175,000 tonnes from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the UK for co-firing with coal in electrical power stations. But many people are unaware of the significant co-ordination and rerouting that takes place in Europe before pellets arrive at their final destination.

Pellets from British Columbia are generally shipped in Panamax ships, so called because they are the largest size that will fit through the Panama Canal. A Panamax ship generally has a draft (submerged depth) of about 12 metres. Because many of the coastal power plants in western Europe are next to shallow water ports, they are not able to berth Panamax ships. Even if they could, power plants may not wish to take delivery of an entire shipload of pellets at once, preferring instead to receive smaller quantities. Thus, it is normal practice for Panamax ships to be off-loaded at a central location, the pellets stored, reloaded onto barges or smaller ships called coasters, and then shipped to the power plant, where they are unloaded once again. This process is known as transhipping.

The majority of wood pellets are tran-

shipped through the Port of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, which competes with nearby Amsterdam and Antwerp for wood pellet handling. The three ports are often collectively referred to as ARA.

Rotterdam was the world’s largest port until 2004, when it was surpassed by Shanghai and Singapore. It remains Europe’s largest port. In 2010, Rotterdam handled 430 million tonnes of dry and liquid bulk cargo, containers, and break bulk (general cargo shipments), and it expects the total to rise to 440 million tonnes in 2011. Antwerp was far behind, handling about 200 million tonnes, and Amsterdam handled about 90 million tonnes. By comparison, Vancouver and Halifax are tiny, handling 75 million tonnes and 12 million tonnes, respectively.

The Port of Rotterdam is vast, covering about 100 km2 and stretching some 40 km up the Maas River. About 90,000 jobs are directly related to the port complex; a further 56,000 are indirectly related.

European Bulk Services (EBS) is a Rotterdam company engaged in the transhipment of wood pellets. It is also a member of the Wood Pellet Association of Canada. “EBS is the dominant multi-purpose bulk terminal operator in the Port of Rotterdam,” says Frank van der Stoep, sales manager at EBS. “With our 220 employees, we engage in the transhipment, loading, discharge, and storage of all kinds of dry bulk products such as coal, minerals, agri-bulk, scrap metal, and biomass prod-

Floating cranes with clamshell bucket grapples unload bulk cargo such as coal and wood pellets from ship’s holds and transfer it to dry land or floating barges.

ucts—wood pellets—to and from Europe.”

“We have a market of over 350 million people at our doorstep and can access them by ships and barges along the coast and inland via the Maas and Rhine rivers and their tributaries,” he adds.

EBS’s customers include mining companies, energy producers, processing industries, ship owners, traders and commodity brokers, and forwarding agents, says Paul Tromp, sales and projects at EBS. The company operates 24 hours/day, six days/week, and will even run seven days if it is busy enough.

“EBS conducts its business operations from two strategically located areas in the Rotterdam port area: EBS Europoort for handling the import and export for agri-bulk products and coal; and EBS St. Laurenshaven, a Panamax terminal that handles mainly mineral, coal, scrap metal, agri-bulk products, and biomass, including wood pellets,” explains van der Stoep.

“These two large terminals are equipped with excellent unloading, loading, and storage facilities,” adds Tromp. “Our terminals are also optimally connected to deep seaways, inland waters, railways, and highways. The terminals can be reached without having to pass a single lock. All types of vessels

can be handled at these terminals, from Capesize vessels to river barges.”

EBS handles some 16 million tonnes/year of cargo at its two terminals, using gantry cranes, level luffing cranes, floating cranes, mobile grab-cranes, pneumatic unloading machines, weighing towers, and wagon loaders and unloaders. The company provides direct transhipment from very large bulk carriers and smaller sized vessels into coasters, river barges, rail cars, and trucks.

When a Panamax carrying pellets arrives at St. Laurenshaven, it is moored dockside. A gantry crane equipped with a grapple unloads pellets from each ship hold. Pellets are dropped into a long storage building with a retractable roof. As each portion of the building is filled, its roof section closes, providing rain protection. As each ship hold is emptied, the crane moves along rail tracks to the next hold and fills the next section of the long storage building. When a ship’s hold is close to empty, workers use a skid-steer loader and brooms to unload the remaining pellets.

From the long storage building, pellets may be transferred to storage pyramids or silos. The EBS terminal has 106,000 m3 of

silo storage capacity for wood pellets, and 80,000 m3 of pyramid storage capacity. Overall, the company has 200,000 m2 of open storage space and 475,000 m3 of covered storage space.

EBS is conscious of the hazards of wood pellets. It takes special care to control temperature, moisture, and dust, and uses a sophisticated remote monitoring system to track pellet temperature and off-gassing for early warning of potential problems. Because most of EBS’s customers adhere to various chainof-custody certification systems, the company is certified under ISO 9001, GMP+ Code, USDA-NOP, BLU Code, and ISPS-certified administration procedures.

Transportation and handling makes up the highest proportion of the final cost of wood pellets. For producers to be successful, it is essential that logistics be handled efficiently. When so much of it is handled thousands of kilometres and many time zones away, pellet producers are fortunate to be able rely on EBS to co-ordinate the movement of pellets. •

Gordon Murray is executive director of the Wood Pellet Association of Canada (www.pellet.org) and can be reached at 250-837-8821 or gord@pellet.org.

AWritten and published timelines are essential to keep your biomass project on schedule.

By Reg Renner

s I sit down to write the seventh article in this series on project financing, I can’t help but think about a magazine editor’s nightmare—trying to corral novice writers into meeting strict and regular timelines. I don’t know about you, but I tend to work best when I have a timeline. Approaching your biomass project, do you have an 18-month chart with deadlines and benchmarks laid out in a logical flow? My experience is that people spend a lot of time talking about the project and sharing their vision with the team, but rarely share benchmarks that let everyone know whether they’re on track.

Why is this important, and what about flexibility and unexpected delays? There can be uncontrollable delays, but your investors and partners need to know there are planned benchmarks. If you are behind schedule, you want to know as soon as possible and make adjustments to get back on track. Consider a finely tuned bobsleigh team. Teams are judged by their start times, interval times, and finish times. The coach, technicians, and drivers analyze these benchmark times and make adjustments to the equipment, team dynamics, and lines of attack. The team runs the course again and checks to see if their strategic changes had the desired effect.

In project financing, falling off the pace can be deadly, as you can run out of cash, enthusiasm, and support. Many funders are looking for a finely tuned team that can make the necessary adjustments in a timely manner and stay at the top of the leader board. In this fast-paced, everchanging industry, you need to know exactly where you are in the timelines and make necessary adjustments.

To avoid the pitfall of losing investor interest and confidence, it is of utmost importance to build a realistic timeline.

Talk to others who have built similar projects or ask a funder ahead of time what the real timelines might be for approval. The first question often asked is, ”How long will the financing approval take?” This is difficult to answer, as a lot depends on how quickly the necessary credit information can be pulled together. A general rule of thumb is the bigger the dollar amount, the longer it takes. If you have financial statements, business plan, and fuel supply contracts in hand, the funding approval process will go quicker. A $1-million project might take four to eight weeks for approval, plus four weeks for documentation and funding, and that is with all the necessary financial information in hand.

In addition to funding timelines, you must bear in mind environmental permits, design, engineering, and installation timelines and put them all together so you can focus on multiple tasks simultaneously. One way to build the timeline is to decide when you want the finished product to reach the marketplace. With biomass energy, for example, it is often advisable to be ready to supply the marketplace for the fall/winter heating season. Good planning at the start of the project can save tremendous stress and disappointment by building in contingencies and flexibility. Equipment suppliers are often very busy supplying other projects, so sitting down with them and mapping out a realistic delivery and installation schedule may be more critical to your success than negotiating the final purchase price. The

other advantage to being prepared is that you can schedule in suppliers and installers during their quieter times, when pricing can be better and technical tradespeople are not overwhelmed with the late-season rush.

As you plan your project, gather your team to help plan the to-do lists and put the tasks on a construction timeline like a Gantt chart or Critical Path Method flowchart. Allow sufficient time for delays and setbacks, but build a schedule that you can refer to at a glance to keep track of your progress. Put in measurable benchmarks that allow the team to make

“Many funders are looking for a finely tuned team that can make the necessary adjustments in a timely manner and stay at the top of the leader board.”

necessary changes as it navigates the twists and turns on the bobsleigh track of project development. You do not want to run out of cash or investor support before you get to the finish line. There is nothing worse than having a financial institution walk away from the project because you missed the window of opportunity. After all, I’m amazed at how quickly two months can go by and it’s time to write another column for Canadian Biomass! •

Reg Renner of Atticus Financial in Vancouver, BC, finances machinery ranging from biomass boilers to densification equipment. With 38 years of industry experience, he recently helped secure carbon offset credits for four greenhouse clients. E-mail: rrenner@atticusfinancial.com.

Building on recent advances and overcoming challenges: here’s where biomass is headed in 2011.

by Heather Hager

has boomed over the past few years. While helping to support a limping forest industry, it has developed into an industry in its own right. This fledgling field continues to see new challenges, however, such as a steady decrease in the capital costs of solar- and wind-based renewable energy and continued low prices for natural gas. As the Canadian forestry industry restructures and begins to pick up again, biomass must find and settle into its own niche. Optimism is high, with some newer technologies moving towards commercial production and hopes for biomass-related policy improvements.

Lumber and pulp and paper producers have long used biomass to provide heat and power for the manufacturing processes. In fact, about 60% of power used in the forest industry is currently provided by biomass, says Avrim Lazar, president and CEO of the Forest Products Association of Canada (FPAC), and recent additions and upgrades have been made with funding support from the federal Pulp and Paper Green Transformation Program. Biomass improves the economy of these operations because the fuel is on site and essentially free.

For other potential biomass users, however, the low price of natural gas and its increasingly touted reputation as the “cleaner” fossil fuel continues to be an obstacle. “The single biggest economic barrier—not just unique to forest biomass, but applicable to all renewable energy—is the low price of natural gas,” says Don Roberts, vice chairman and managing director, renewable energy and clean technology, for CIBC World Markets. Large energy consumers, such as greenhouses, that once switched to biomass to save money are switching to natural gas because of the cost and convenience. Even Ontario Power Generation, which must cease coal-fired power generation by 2014, has indicated that it’s now pursuing a conversion to natural gas, rather than biomass, at its coal-fired Thunder Bay generating station. Until fossil fuel

A

A rail fleet to move your cargo. Prices and terms to move you.

costs increase or a fossil tax levels the playing field, focusing biomass energy efforts in areas that have little access to natural gas will provide a cost-effective alternative to expensive bunker oil or propane.

As biorefining and bioproduct technologies continue to advance, another challenge is in determining which applications will be most economical. In 2010, FPAC completed a groundbreaking modelling study called the Future Bio-pathways Project. It examined a mix of emerging biotechnologies and traditional forest product operations to determine which combinations of biomass-derived bioenergy, biofuels, biochemicals, and other bioproducts maximize economic, social, and environmental returns. It turns out that integration is key.

“It became obvious that, from an environmental perspective, it makes more sense to use the waste stream, rather than going to roundwood for bioenergy,” explains Lazar. “From an economic perspective, when it (bioenergy, biofuels, biochemicals) is integrated into existing industry, like the pulp and paper and wood industry, the economics pretty well work without government’s intervention,” he adds. “But when it’s stand alone, for the most part, you need government subsidies for the economics to work.” Model updates continue as more data become available for newer technologies.

With the addition of new bioproducts to traditional forestry has come a shift in thinking, says Lazar, from the concept of value added to the concept of value extraction. He notes that although value added is still important, the cost of labour to make value-added products decreases Canada’s competitive advantage compared to countries like Indonesia and China. However, extracting products from every bit of each tree is another way to add value to the resource. “Value extraction is trying to find as many products and as high value products as possible extracted closer to the natural resource,” he explains. “This is a bit of a step change in thinking about it, from getting some cheap energy to actually seeing a whole new product line from each tree harvested.”

As the forest industry continues to restructure to maintain economic feasibility, this kind of integration with the bioeconomy is likely what will allow it to survive and prosper into the future. “I would say that, at the end of the day, any kind of traditional forestry operation that is not actively looking at some kind of bioenergy angle—and I’m not saying it’s economic in all cases—but if you’ve not explored it in detail, then you’re perhaps missing some opportunities to improve your economics,” says Roberts.

Finally, biomass faces a distinctive economic hurdle that other forms of renewable energy do not. “One of the negatives of bioenergy is that we’ve got this pretty high variable cost—the cost of delivered biomass—and that is a problem, definitively,” states Roberts. He points out that technologies for all forms of renewable energy are improving and their capital costs are falling. That gives increasing advantage to renewables like solar and wind power, which have only capital costs and no variable costs. “So we’re going to see a deterioration in the cost of bioenergy relative to other forms of renewable energy.”

To counteract this effect, says Roberts, “you have to take advantage of the unique properties of bioenergy.” He lists two. First, bioenergy is dispatchable, which means it can be used when it’s needed, when it’s cloudy or dark and there’s no wind. “One of the implications is that maybe we should be looking at renewable energy complexes where we have wind and solar and we complement that with bioenergy,” he suggests. Second, like fossil fuels, biomass can be used to make products other than electricity, for example, chemicals and

possibly transportation fuels. Other renewables cannot do this. “And we should take advantage of that more,” he concludes.

A number of exciting biomass processing and conversion technologies continue to proceed through the demonstration and commercialization pipeline. For some of these products, likely the biggest challenge in promoting their uptake is that they are unfamiliar and unproven, says Canadian Bioenergy Association (Canbio) president Douglas Bradley, citing pyrolysis oil as an example. Companies must undertake major trials to ensure it can be used in their current energy systems, and they also need to be sure that a regular supply will be available in the marketplace. Commercial-scale demonstrations of new technologies are critical to their uptake.

Roberts lists three technologies that he thinks are particularly promising: smallscale gasification, pyrolysis, and torrefaction. All three are moving towards commercial scale in Canada.

Small-scale gasification is the most advanced of the three, with some installations fired up in late 2010 and others under construction. For example, the Kruger Products tissue mill in New Westminster, British Columbia, commissioned its Nexterra gasifier in late September, producing low-pressure process steam; and the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, British Columbia, fired its Nexterra gasifier in mid-November, producing heat. The University of British Columbia in Vancouver is scheduled to commission its Nexterra gasifier, producing 2 MW of power and steam for heating, in late 2011.

Gasification itself is not new, with many large-scale, industrial, biomass-fired installations functioning worldwide. However, producing efficient heat and power at a scale of less than 10 MW is a new advancement, says Roberts. “Historically, you needed a fair scale in order to be efficient and get the technical efficiencies up and to be economic,” he explains. “But, we’ve seen improvements both in the gasification technologies as well as some of the engine technologies, which utilize the gas from biomass, which have allowed us to get to smaller scale.” He notes that Canada has global leaders in this area, such as Vancouver-based Nexterra.

The advantages of small-scale gasification are several, says Roberts. A small sys-

tem requires much less capital investment than does a larger one, making it more accessible for communities and small industries. It also requires less fibre than larger systems, which minimizes effects on the fibre market and thus the feedstock price risk. Finally, smaller systems are more practical for more applications. “Critical for the economics to work in combined heat and power applications is that you need someone to use the excess heat—so not just selling the electrons into the power grid,” says Roberts. “The challenge when you have a really big power plant is that you produce so much heat that it’s difficult to find a big enough heat sink for it. When you get a smaller plant, then there’s a lot more heat sinks out there, so that increases the number of potential sites for your system.”

Biomass pyrolysis has also seen technological improvements. Fast pyrolysis involves heating biomass in the absence of oxygen, producing pyrolysis oil and a biochar byproduct. “Pyrolysis oil, I think, will be a really good product because it’s twice as energy dense as pellets and can be transported more cheaply than pellets long distance,”

says Bradley. “I think this is going to be a competitive product in the future.”

In Canada, Ottawa-based Ensyn and Vancouver-headquartered Dynamotive have been the main developers of fast pyrolysis.

“Ensyn has some operations up and going, and they are continuing, especially through their joint venture with UOP (a Honeywell company) to drive down the costs through improvements in their technical processes,” says Roberts.

Another joint venture, between Ensyn and Canadian wood-product firm Tolko Industries, will produce pyrolysis oil at a large, commercial scale. Announced in June 2010,

Torrefied wood pellets are expected to revolutionize the pellet market for co-firing with coal.

the High Level, Alberta, facility will be capable of producing 85 million L/year of pyrolysis oil. Most of the product will be burned to make heat for the sawmill and power for the grid, but a small portion will be used to extract phenolic light compounds, says Roberts. Those can be processed into phenolic resins, which are usually derived from fossil fuels and used in a wide variety of applications. Another use under study is the further upgrading of pyrolysis oil to drop-in transportation fuel for automobiles, which is expected some years down the road.

Biomass torrefaction is also approaching its first commercial demonstration in Canada. The process has been described as a mild form of pyrolysis, which essentially roasts the biomass to produce a more en -

ergy-dense and hydrophobic product. “If you have something that’s hydrophobic, it means you can avoid some of the capital costs at the front end of your power plant, essentially the kind of capital costs used to protect the regular pellets from water, and that’ll save you some money,” says Roberts. And in theory, torrefied wood behaves more like coal for storage and processing than do regular wood pellets, which would be a game-changer for co-firing with coal.

“We don’t have anyone in the world commercially producing torrefied pellets,” says Roberts. “But I would expect that by early 2012, we’ll see a couple of these commercial plants up and running, and it will be the solid wood fuel of choice for the power plants that want to co-fire biomass with coal,” he predicts.

In fact, the Wood Pellet Association of Canada (WPAC) is in the process of establishing a commercial-scale facility to produce torrefied pellets. “We want to have a plant producing 5 tonnes/hour, so about 30,000 tonnes/year,” says Gordon Murray, executive director of WPAC. WPAC and a selected pellet manufacturer are now

applying for funding to support the project’s construction. The aim is to market torrefied pellets in Canada for co-firing in coal-fired power plants, and then grow the market, says Murray.

Next-generation cellulosic ethanol technologies are also advancing towards commercial demonstration, says Gordon Quaiattini, president of the Canadian Renewable Fuels Association. “We’ve had a number of positive developments,” he notes. For example, Quebec-based Enerkem and Ontario-based Greenfield Ethanol’s joint waste-to-ethanol project is now under construction in Edmonton, Alberta. It will be the first full commercialization scale-up of Enerkem’s technology, which involves gasification of the feedstock and reaction of the resulting syngas with catalysts to produce ethanol or other chemicals. The technology platform “will provide opportunity for forestry residue as well as agriculture residue to be the feedstock,” says Quaiattini.

Other cellulosic ethanol technologies such as those based on fermentation, however, will likely remain most economical with agricultural biomass, suggests Roberts. It’s more cost effective to modify grain ethanol plants to include a cellulosic component from agricultural residues because of shared infrastructure and feedstock opportunities. “Cellulosic ethanol may be one of a series of products that we produce out of a biorefinery, but I don’t expect us to have pure production facilities that just do cellulosic ethanol from woody biomass,” he says.

Finally, although popular in Scandinavia and elsewhere in Europe, small-scale community heat and combined heat and power projects have received only a little attention in Canada. However, Bradley expects to see several community projects start in Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia in 2011, which would help to showcase the technology. Visits to Scandinavia and Europe led by Canbio have allowed participants to scope out technology and bring back ideas for future projects, he says.

Without an overriding impetus for bioenergy, however, its uptake in Canada will lag. “We haven’t got a national energy policy, we haven’t got a national carbon policy, we don’t know where the federal gov-

ernment’s going to go on climate change regulations. So the pricing of carbon, the economic advantage of moving away from fossil fuels, is all basically speculation on (future) government policy. That’s a huge stumbling block,” says Lazar.

Roberts agrees: “A big impediment is the lack of clarity, especially at the national level, and I would say outside of British Columbia, in the regulatory treatment and pricing of carbon.” There’s no telling when this problem might be remedied, as the current Canadian government seems content to wait and follow the United States’ lead.

Perhaps the only bright spot on the bleak national energy policy landscape has been the introduction of a national renewable fuel mandate for blending ethanol or biodiesel in transportation fuels, a policy that “builds on a number of provincial standards that have been in effect for some time,” says Quaiattini. “With the mandates coming into effect—both the 5% ethanol (on December 15, 2010) and then the 2% renewable diesel mandate in 2011—that provides the regulatory platform through which companies can know that the Canadian market is going to require this fuel. They can make investment decisions based on that certainty,” he says. “We won’t have next-generation renewable fuels in Canada if we don’t build a solid foundation based on first-generation technology and first-generation feedstock.” Quaiattini also stresses it will be critical to ensure that future renewable fuels mandates include specific cellulosic or next-generation requirements.

Elsewhere in energy policy, it has been up to individual provinces to step up and fill the void, and there have been some notable advances. For example, a few provinces have introduced feed-in tariffs for renewable energy, and British Columbia has called specifically for power from biomass. However, incentives for combined heat and power have not yet been introduced, notes Bradley, which would be a more efficient use of biomass than power alone and could give it an edge over other renewables.

Changes to boiler regulations in British Columbia have also increased opportunities for bioenergy. The requirement for small power projects to have a steam engineer on site at all times has been cost-prohibitive for some, even though newer technology provides remote moni-

toring and automated control systems. The province also revised its boiler certification requirements to accept non-ASME boilers if they meet equivalent standards, which should allow more of the latest, state-ofthe-art equipment manufactured in Europe to be used in Canada, says Bradley. “B.C. became the first province to dismantle that legislation this past spring, and I’m hoping that the other provinces will follow suit.”

Securing a reliable, long-term fibre supply is critical to any biomass or bioenergy operation. Sawmilling and wood processing are expected to pick up again, although

likely not to their former extent, which should make additional residual fibre available from forestry and processing. However, Bradley suggests that adjustments in feedstock supply are needed in the form of long-term fibre contracts, which would reduce the variable cost risk and encourage investors and lenders.

“Back around 2000/2001, you could still walk up to a sawmill and sign an agreement for 20 years to take their biomass at a particular price,” he says. “Within about two to three years, it became impossible to get long-term contracts.” He says mill owners became reluctant to lock in for long periods as the demand and then

Once piled and burned in open air, slash is increasingly becoming a saleable product with value for the forest industry.

prices for fibre increased.

It has also been difficult to access longterm sources of in-woods fibre for biomass users without forest licences, he adds. “With a bioenergy project, they never had any of this wood; it would all belong to the sawmills and pulp mills.” A positive sign is that various provinces are looking at novel ways to make unmerchantable timber available for bioproducts and bioenergy projects.

On the demand side, the experts expect to see increased conversion from fossil fuels to biomass, which could result in expanding or shifting domestic and export markets. Although European demand for Canadian wood pellets has been negatively affected by currency exchange rates and new pellet capacity closer to Europe, Murray is forecasting significant market growth for wood pellets in Europe. Still, Canadian pellet manufacturers continue to look for new markets. Canbio has launched a Go-Pellets campaign to promote pellets for heating residential, commercial, and institutional buildings in Canada. Meanwhile, WPAC is pursuing new, large-scale industrial markets, both within Canada (e.g., co-firing with coal by Ontario Power Generation) and internationally (e.g., Korea).

Relevant policy support will be critical to maintain demand for bioenergy and bioproducts, as long-term, continuing subsidies are not economically viable. “One of the challenges that we’re going to have going forward is the public financial constraint to support a lot of these projects,” says Roberts. “I think we should not expect a great deal of subsidy.”

Indeed, FPAC’s Future Bio-pathways analysis shows a positive role for increased integration of new bioenergy and biorefining technology with the traditional forest industry. “The study said that the forest industry economics, for the most part, won’t work without the more intelligent utilization of biomass,” says Lazar. “The extraction— not just of bioenergy but also biodiesel, bioethanol, biochemicals—the extraction of all those extra values changes the economics of forestry to make them quite a bit more viable. Without that, the economics continue to be difficult.” •

Pinnacle’s Burns Lake wood pellet plant emerges as Canada’s current largest.

By Jean Sorensen

Renewable Energy’s newest

pellet plant arcs into production with the potential to be Canada’s largest pellet mill, producing 400,000 tonnes/year. Located in Burns Lake, British Columbia, the $30-million facility is not only pushing the envelope in production, but is honing ways of using raw fibre resources, including roundwood, and landing a quality pellet on the doorstep of international buyers in Europe and Asia.

Pinnacle’s newest plant is its sixth achieved in just over a decade. Chief operating officer Leroy Reitsma says that Pinnacle has been evolving its own set of best practices and has a corporate culture of keeping a low profile. As it has grown from a smaller entity to one of North America’s largest pellet producers, it has become increasingly hard for the company to fly below the radar. Reitsma isn’t keen to talk about technology or to “disseminate the information, as we are paying a price for its development.” But, Pinnacle has progressed from its humble beginnings in 1989 with the Pinnacle Feed and Pellet plant in Quesnel, central British Columbia, to become a big-time player on a world stage.

The Burns Lake pellet plant will shoulder its way into the ranks of international heavy-weight mills when finished, although it’s smaller than the newly built $65-million 550,000 tonne/year Green Circle Bio Energy facility in the southern United States and the 900,000 tonne/year Vyborgskaya Cellulose pellet plant in Vybork, Russia, which was slated to begin production in late December 2010. However, the Burns Lake plant is considered large by international standards, bringing Pinnacle’s total production capacity to close to 1.2 million tonnes/year.

Reitsma says the ability to handle diverse fibre input is the initial element in a process designed for efficient delivery of energy. “At the end of the day, we are trying to build the most cost effective means of moving energy in wood form to the point of consumption,” he explains. “The distinct feature of this mill is that it will take all types of fibre: shavings, full-tree-length logs, any kind of wood that can be processed.” Pinnacle’s Meadowbank pellet plant—its fifth—processes a full array of sawmill and bush residuals. The Burns Lake mill is simply marching in stride to what has become a worldwide trend towards greater fibre diversity and roundwood use.

Low-grade roundwood provides a supplemental fibre source for pellet plants should traditional sawmill residuals dwindle in down-turned markets. In Europe, pellet plants have been able to extend the fibre circle even further, using thinnings from new forests. While it may seem a long-term future consideration in the Burns

Lake area, the viability of forests and operators is increasingly a focal point for local governments as mountain pine beetle wood is harvested. Burns Lake Village Mayor Bernice Magee says the town reaps employment and expenditure benefits. “We are in a situation where we are looking at a declining timber supply (as beetle-killed wood is exhausted),” says Magee, adding that northern timber-dependent communities want to ensure the existing base is used wisely and the regrowth of new forests offers opportunity. “We are looking at ways to sustain ourselves, and pellet plants will help extend the use of the timber supply.”

The plant is located in the BulkleyNechako regional district and lies 24 km southeast of Burns Lake village. The site is approximately 40 ha, with buildings covering about 3 ha. It follows what has become a formula for Pinnacle: located close to essentials such as power, access routes, and materials. The main BC Hydro 138 kV power line to the northeast of the plant will feed into the small substation powering the plant.

TOP: The bank of eight Andritz-Sprout pellet mills will double in phase two, for a production capacity of 400,000 tonnes/year of wood pellets.

MIDDlE: The foundation for the first silo, one of two 5,000 m3 Westeel units, was poured in December 2010.

BOTTOM: Burns Lake plant manager Gerry Clancy came out of retirement for the challenge of the project.

The Canadian National Railway line on the south boundary will include a 1.3-km rail spur able to accommodate up to 29 rail cars, with two rail loading bins suspended over the rail spur.

A nearby major highway links the mill to two Hampton Affiliates sawmills: Decker Lake Forest Products in Burns Lake, and Babine Forest Products’ mill, located 4 km southeast. The Decker and Babine sawmills have already shut their beehive burners, with waste material being sent to a storage site at the Burns Lake facility. Fibre such as sawdust, wood shavings, hog material, and low-quality roundwood could also come from other mills, as beehive burners are being phased out by 2016. Public information provided to the regional district from Pinnacle states that a second road is being used within the BC Hydro power line right of way, which will allow the Burns Lake operation to connect to the Augler FSR off-highway logging road used by Babine Forest Products. The off-highway route will allow Pinnacle to haul larger payloads such as logs and use large chip trucks.

“We are taking everything they can throw at us,” says new plant manager Gerry Clancy, a 33-year mill superintendent with Babine who came out of retirement to take on the challenge of starting a new, large production facility. Clancy says that forestry residuals would be processed at the logging site and roundwood at the plant using a Peterson grinder.

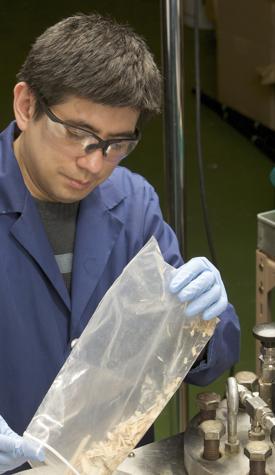

One challenge will be to minimize the dirt, rocks, and metal that come along with residual debris. Density separation equipment will allow stones and dirt to escape, and metal detectors will pick up stray metal. Spark detection and fire suppression systems from Clarke’s Industries are installed to enhance safety should contaminants make it into the pelleting process.

The plant also faces a challenge in mix-

ing wet or green feedstock with drier sawmill residuals. The fibre will be dried from about 45% to 4.5–5% moisture content, which Clancy says will require gauging the moisture content of the feedstock at the front end and learning how to mix and dry it. The Meadowbank plant is already taking bush residues and mixing wet and dry feedstock, which is a plus in the learning curve. Burns Lake plant operators were in other Pinnacle mills during December 2010, learning the mixing processes, says Clancy. The ability to piggyback on other plant knowledge will shorten Pinnacle’s start-up time. “We will have operators from the Quesnel plant for the first little while,” he adds.

Reitsma says the plant’s MEC dryers are designed to handle controlled fluctuations in the moisture content. The key will be ensuring that the degree or rate of change is not “quicker than the dryer’s ability to respond.”

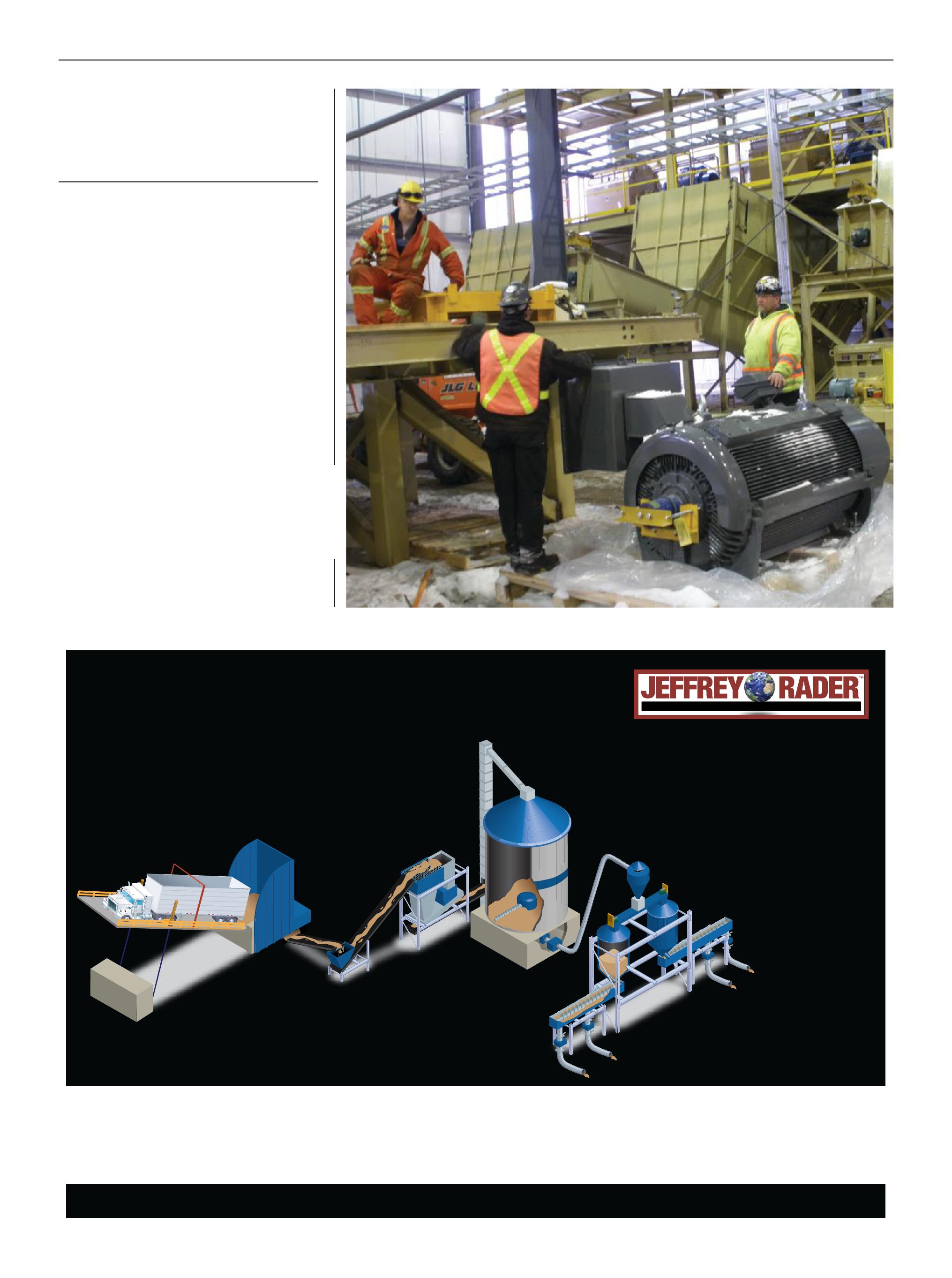

The plant’s design features a receiving area for the storage of residual fibre and roundwood storage; a hammermill facility to reduce the fibre material to a uniform size; a fibre drying facility, with process heat supplied by the plant’s own wood-fired burners; pellet mills to manufacture the wood pellets; storage silos to inventory the finished goods and a railcar loading facility. “The design of this plant is reflective of both the continued evolution of our process design and our 20 years of technical experience,” says Reitsma.

The conceptual design, budget, and detailed engineering was done by Stolberg Engineering of Richmond, British Columbia, a company long known for engineering sawmills and one that has firmly niched into the province’s burgeoning pellet plant industry, starting with design work in 2000. This Burns Lake operation is the largest greenfield pellet plant the firm has designed, says John Ingram, president of Stolberg Engineering. “From an engineering perspective, a lot of our material handling experience from the sawmill industry was directly transferable to the pellet industry. On the plant process side, we worked closely with the client and the major equipment vendors.” Input from Pinnacle, which has evolved is own modular-style construction for the steel structure after five plants, ensured a fast start.

The plant features a fully integrated plant-wide electrical and proprietary control system, developed in cooperation with Cogent Industrial Technologies, that helps

Roger Hull (left) and Kerry Eglin (centre) of K2 Construction and Derek Dezamits (right) of Pinnacle Pellet stand near the outfeed from three Bliss hammermills.

coordinate activities among the key production areas. Like Stolberg Engineering, Cogent is building a reputation for providing control systems to pellet plants. “We have a great relationship with Cogent,” says Reitsma. “Good things happen when you enjoy working together, and this is certainly the case in respect to Cogent.”

“The system boundaries are defined, the process layout accommodates operability and maintainability requirements, and the system adheres to plant standards,” says Cogent marketing representative Krystal Souza.

“The Burns Lake facility will also include a state-of-the-art information technology and information management system to connect people to the plant equipment and process.”

She notes that the system interface translates data into useful information that can be used by plant personnel to monitor and make adjustments for continuous improvements.

Pulverized Coal Boiler Conversions CFB Boiler Feed Systems

The plant will initially start up with wood shavings, which will enter the system through this infeed, says plant manager Gerry Clancy.

Service Electric, out of Quesnel, British Columbia, is the electrical contractor for the mill. It has also provided services to Pinnacle’s Meadowbank and Williams Lake operations.

Once through the primary breakdown phase and dried, the fibre undergoes further breakdown in a series of Bliss Industries hammermills. After conditioning, the material moves to Andritz Sprout-Bauer pellet mills. “We will have eight pelletizers in phase one,” says Clancy. When the plant is at or near full production in phase two, 16 pelletizers will be operating.

Once the pellets are extruded, they pass through pellet coolers of Pinnacle’s own design and construction. They’re then transferred in bulk to one of two 5,000 m3 Westeel silos for storage prior to rail load-out and transport.

Eric Hilger, general manager of bulk sales and logistics for Pinnacle, says that pellets will be transported in covered hopper cars to port. Pinnacle is a partner in Houston Pellet Limited Partnership with Canfor and the Moricetown Indian Band, and the partnership has had a wood pellet

terminal facility at Ridley since 2007. A number of advancements have been made to minimize pellet breakage and fines by using systems that are common in grainhandling facilities, particularly for brittle or fragile items such as dry beans, lentils, and chickpeas, says Hilger. Such grain-handling systems use a series of baffles that slow product flow by passing it from side to side or in a spiral as it flows downwards.

Jim Sawby of Alberta-based Skyway Grain Systems says that his company has been working with Pinnacle since 2004 for pellet handling and that it has been a learning experience in how to minimize product damage. Skyway supplied the two storage silos, the conveyance system to the bins, and the conveyance away from the silos. Skyway has also worked on pellet projects at Williams Lake, Houston, Meadowbank, and Ridley Island facilities.

The 400,000-tonne/year Burns Lake plant is a hefty leap forward in production for Pinnacle, whose other five plants, including Houston Pellet, have a combined total capacity of 760,000 tonnes/year, already making it a leader in Canada. When fully productive, the new plant will raise Pinnacles’ combined output to 1.16 million tonnes/year. British Columbia’s contribution to the world wood pellet market has risen from 64,000 tonnes/year in 1996 to 1.2–1.3 million tonnes/year in 2010, produced by about 10 pellet plants, according to Staffan Melin, research director of the Wood Pellet Association of Canada. By comparison, all plants in Canada combined ship approximately 1.8–2 million tonnes/year.

Canada’s

By Paul Janzé

material handling systems

for use in extreme northern environments requires special care. Temperatures in northern Canada can vary from –45˚C in winter to +35˚C in summer. In winter, snow load, blowing snow, and ice build-up are always problems to be encountered. And in extreme cold, steel becomes very brittle and susceptible to damage from impacts.

In warmer climates, you can always push the design limits and use short, steep, small, highspeed conveyors. In extreme cold climates, however, simultaneously pushing all design limits is a recipe for disaster. It’s best to be conservative in the design of material handling systems.

Biomass is particularly difficult to handle. It is inherently wet and therefore freezes, it can have ice particles frozen to it, and it may contain loose snow. The particle size of biomass is rarely uniform, and the product tends to knit together and doesn’t flow well, particularly when packed with snow. Frozen wood chips are brittle and readily break up on impact into smaller particles, which is a concern for certain processes. In addition, contaminants such as dirt and grit, which may normally be removed by screening, can freeze and stick to the biomass. These challenges require special consideration but can be addressed. The following is a list of biomass handling remedies and recommendations for cold climates that I have learned over the years.

Expect that biomass stored in open storage piles will be covered with snow for much of the year. Unless the snow is scraped off, conveyors should be sized to handle the additional amounts of loose snow that will be reclaimed with the product. Also, expect frozen lumps to come off the pile. If there is no

scalping screen or lump breaker ahead of the conveyor, design the chutes and skirtboards to handle the largest anticipated frozen lump.

The load on the conveyor should be kept lower than normal to increase belt-to-product contact, and the speed should be kept fairly slow. This will result in a wider than normal belt.

Transitioning from one conveyor to the next requires special care to give the frozen and slippery product time to reaccelerate. To ease the transfer of material from one conveyor to another, limit the conveyor slope in the loading zone to 6˚ or 7˚. Limit the maximum conveyor slope to 12˚ and avoid across-theline starting to prevent material slide-back when restarting a loaded belt. I prefer electrical soft-starts, as they are not affected by temperature and are easily adjustable. Additionally, maintenance can be done in warm electrical rooms rather than out in the cold.

If conveyor slopes greater than 12˚ can’t be avoided, consider using grooved belts (negative cleats), which are fine for slopes up to 15˚. For slopes greater than 15˚, use belts with positive, vulcanized multi-cleats. Generous vertical concave curve radii are recommended.

Avoid having a long, outdoor conveyor entering a warm, moist building. Moisture will condense and freeze on the cold conveyor. It is better to have a transfer occur outside the heated building onto the tail end of a warm conveyor that is mostly inside the heated building.

Snow-covered logs wait to be chipped or ground into biomass.

If slide-back is an issue on existing conveyors, you may choose to use de-icing chemicals, which can be sprayed or dripped onto the belt. De-icing systems are costly and should be installed only as a retrofit.

Use belts designed for extreme low temperatures, i.e., those that retain their flexibility and won’t crack.

If the conveyor system uses belt weigh scales, plan on recalibrating them at least twice yearly: once in winter and again in summer.

Extraordinary expansion and contraction can be expected with extreme temperature ranges and must be accommodated in the design of conveyors and structures. For example, a 500-foot conveyor will expand and contract approximately six inches with a temperature range of –45˚C to +35˚C. Conveyors and structures must have a sufficient quantity of properly placed expansion joints to accommodate this extreme expansion and contraction.

Avoid high alloy steel shafts. It’s best to stay with large-diameter, low-carbon shafts.

Use lubricants designed for the extreme temperature variation. Under extreme cold temperatures, viscosity should not increase to the point that grease and oils solidify; they must remain fluid. At extreme warm tempera-

In cold climates, frozen biomass, ice, and loose snow can add to the difficulties inherent in handling biomass.

tures, lubricants should not thin out to the point at which they are no longer lubricating.

Conveyors should be covered to prevent material from blowing off the belt. However, it is recommended that conveyors be carried inside enclosed galleries. At extreme cold temperatures, even a slight breeze can cause frostbite in just a few seconds. If working conditions are poor, equipment will not be maintained.

The bottom of the gallery below the belt should be kept open to permit snow and dust to fall from the return belt. This avoids snow and dust build-up inside the gallery, which is not only hard to remove, but can result in serious structural overload. The amount of snow and dust falling off return idlers can be substantial, so provide lots of space under conveyors for clean-up access.

Access on frozen, snow-covered surfaces can be treacherous. Use stairs and avoid ladders wherever possible. Use safety-grip grating on walkways and platforms. Northern areas have very short winter daylight, so provide good lighting along conveyors.

Avoid using belt brush cleaners; they will immediately fill up with snow and dust. Two sets of carbide-tipped belt scrapers are recommended for scraping frozen snow and dust off the belt. There will be a lot of snow dust coming off the scrapers, so provide a lot of room below the scrapers inside the head chute.

Raised-cleat belts are hard to clean; belt scrapers cannot be used. The only effective way to clean them is to use a properly designed and applied air-knife. Also, consider using a “thumper” roll to shake the frozen snow and dust off the return belt.

Snow and dust will stick to almost any surface; therefore, use steep chute angles and large-radius corners between chute plates. If possible, line chute plates with UHMW PE (ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene) or PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) plastic, to which ice and snow don’t readily stick.

If dust control is part of the material handling system, the amount of airborne dust to be handled will be many times greater in winter because snow crystals will loosen from the product and be sucked into the dust pickups. If possible, avoid baghouses, as they can become clogged with packed snow. Highefficiency cyclones are less prone to plugging.

Avoid heating the equipment or low-occupancy structures to the point at which the product will thaw out. Not only is heating costly, but there is a danger of the material re-freezing. There is a tendency to apply heat to chutework, which is susceptible to freezing. This is not a good thing to do; it will only increase the freezing problem by moving it further downstream. Experience has shown that the worst seasons for conveying moisture-laden materials that will freeze are the spring and fall “shoulder” seasons, when temperatures are +/–5˚C.

Use drive pulleys with large diameters and vulcanized diamond-shaped lagging to increase traction. Snub pulleys are recommended.

Space pre-tensioned safety pull cord switches closer together than normal to minimize the effect of pull cord contraction/ex-

pansion causing nuisance trips.

Special care should be taken with the design of fire protection. Dry systems are required. Keep the size of sprinkler zones small, so that if one is activated, there isn’t a huge area to drain before it can freeze. Heat or flame detection is recommended.

When handling biomass, the material density can vary widely depending upon the form of the biomass and the moisture content. Determine the amount of bone-dry fibre needed for the process and use the lowest density for volumetric calculations. For power and strength calculations, use the selected volume but at the highest density. Be sure to allow extra capacity for the handling of loose snow.

All of the above recommendations cannot always be accommodated, particularly those having to do with conveyor geometry. For

example, sometimes there is no option but to use conveyors steeper than recommended. Also, many installations are not constructed as I have described, but they work satisfactorily. Every installation is unique, and all conditions should be considered, but if you have the real estate and the budget and you follow these rough guidelines, there will likely be few conveying problems. •

Paul Janzé is a senior industrial material handling specialist with more than 30 years of experience in engineering, equipment design and manufacture, project management, and maintenance, primarily in the forest products industry. He is a specialist with difficult-to-handle materials such as wood chips, waste wood, bark, biosolids sludge, wet pulp, poultry litter, animal tissue, and fly ash, which all have unique handling characteristics. Paul can be reached at pjanze@telus.net or through his website at www.advancedbiomass.com.

Wondering how your colleagues are faring or what they’re up to? Help us learn about your role and information needs, and define the current state of the sector by participating in Canadian Biomass magazine’s first industry survey. The survey will take less than 10 minutes to complete, and you will be eligible to win a GPS!

New Tier 4 Interim engines are coming in 2011, bringing tighter emissions restrictions that may reduce performance.

By Bruce Barker

theworld might be breathing easier, but a lot of diesel engineers are hyperventilating in their efforts to reach the new Tier 4 Interim (IT4) standards for 2011. The new standards for forestry diesel engines will require a 90% reduction in particulate matter (PM) and a 50% drop in nitrous oxide (N2O) compared to Tier 3 regulations. The standards are part of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) emission policy for diesel engines, and Canadian biomass harvesters have no choice but to follow along because off-road engines are primarily made in the United States or Europe, where the same standards are being applied.

Until 1994, off-road diesel engines were unregulated for vehicle exhaust emissions. That changed when the first of the EPA’s emission standards was implemented. The EPA’s initiative to lower diesel engine emissions goes back to the U.S. Clean Air Act of 1970, passed just after the first Earth Day. First to be regulated were automobiles, followed by on-highway trucks.

Since then, emission standards for offroad diesel engines have steadily become more stringent. The first Tier 1 standard was phased in from 1996 to 2000, and more stringent standards for Tier 2 and Tier 3 were phased in from 2000 to 2008. IT4

standards will be in place in January 2011, with full Tier 4 final standards implemented by 2015. At that point, an additional 80% reduction in N2O will be required compared to IT4 while maintaining PM emissions at IT4 levels.

Roger Hoy, director of the Nebraska Tractor Test Laboratory (NTTL) at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, has been following the development of the Tier 4 technology closely. He has had a chance to preview some of the new emissions reduction technologies. He is pleased with their performance, but, like other off-road engine experts, has some concerns about the effect on engine efficiency.

“So far, the EPA will tell you that reduc-

Off-road diesel engines will have to conform to Tier 4 Interim regulations in 2011.

tion in emissions will increase fuel economy. That is sort of true and sort of false. Applying emissions reductions alone will reduce fuel economy, naturally, but some of the things that manufacturers have introduced at the same time to reduce emissions have improved fuel economy,” says Hoy. “Electronic fuel injection to control emissions has improved fuel economy. We’ve seen two valve heads go to four. When John Deere went from the 8020 series to the 8030 series, they got a huge increase in fuel economy because they redesigned their

engine to give it more air. My personal opinion is that going to Tier 4 Interim might be a wash, but going from Tier 4 Interim to Tier 4 final is probably going to lose some fuel economy.”

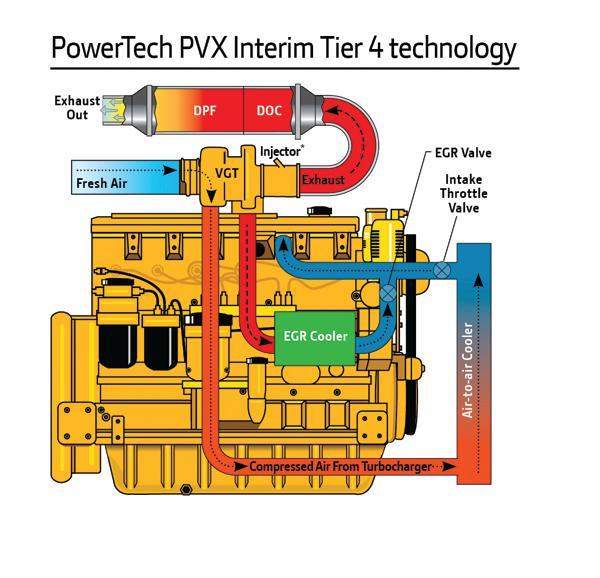

Hoy explains that several technologies are being used currently for Tier 3 reductions that will be used in Tier 4 Interim reductions. Two that have helped achieve Tier 3 reductions are internal exhaust gas re-circulation (IEGR) and cooled external gas re-circulation (CEGR).

IEGR is primarily used at engine startup to reduce emissions by recirculating exhaust gases back into the engine for more complete combustion. CEGR cools the gas

through a heat exchanger to allow a greater mass of exhaust gases to be recirculated back into the engine.

Two other key technologies will help manufacturers meet IT4 reductions: selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and regenerating particulate filter (RPF). They take divergent approaches.

SCR operates like a catalytic converter on a car. In one such system, a 32% urea solution is sprayed into the exhaust gases as they leave the engine and just before they enter the catalytic converter. Inside the SCR system, the exhaust heat turns

Diesel-powered non-road equipment such as chippers and grinders will also be subject to Tier 4 regulations.

the urea into ammonia, which reacts with N2O to produce water vapour and harmless nitrogen gas. “What they have done is say that they aren’t going to worry about some of the emissions within the engines. They will let the N2O go back to a Tier 2 setting, and they are going to take out the N2O with a separate component like the SCR,” explains Hoy.

The urea solution is commonly called diesel exhaust fluid (DEF). It is stored in a separate, refillable tank. “The DEF is a consumable quantity,” says Hoy. “These machines have a separate tank where you might put 5 or 10 gallons of DEF, and if you try to put water in, or don’t fill it, the machinery won’t run, or it de-rates to a point that is so obnoxious that you put the right stuff in.”

Hoy had the opportunity to test the performance of an off-road engine equipped with SCR technology. He found that, depending on operation, DEF consumption was 2–4% of diesel fuel consumption. At an average 3% consumption, an operator using 1,000 litres of fuel could expect to use 30 litres of DEF. “We realize this is an operating cost that should be tracked, just like you do with diesel fuel,” says Hoy.

Overall, though, Hoy explains that the fuel economy with the system he tested was excellent; the engine was allowed to

use more fuel-efficient operating modes because it did not have to deal with N2O emissions within the engine.

The other main technology that will be employed to reach IT4 standards is RPF. In many cases, the RPF replaces the muffler, trapping and holding particulates remaining in the exhaust system. Trapped particles are eventually oxidized within the RPF in a process called regeneration.

“In this case, the N 2O emissions are controlled within the engine without worrying about particulates,” explains Hoy. “What it does with the PM is to replace the muffler with a particulate filter trap. That all sounds nice, but eventually the PM builds up, and periodically, the machine may have to inject diesel fuel into the exhaust system to raise the exhaust gas temperatures up to burn off the particulate that has been trapped.”

“When the filter starts building up soot (PM), the back-pressure in the system starts to go up, and if exhaust gas temperatures aren’t high enough, or not in the right range, this soot won’t convert to ash on its own, so something has to be done to bring it up, so

diesel fuel is injected,” explains Hoy. “You might see a change in fuel consumption as these things burn.”

PM is converted to ash during regeneration, and remains inside the filter. The amount of ash accumulated during a period of use will eventually mean the RPF will need replacing after about 3,500 or 4,000 hours.

In the agricultural market that Hoy studies, John Deere is combining a diesel oxidation catalyst (DOC) with RPF (Deere calls it a diesel particulate filter, DPF).

The company’s IT4 information says that under normal operating conditions, the DOC reacts with exhaust gases to reduce carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and some PM. The downstream RPF forces exhaust gases to flow through porous channel walls, trapping and holding the remaining PM. Trapped particles are eventually oxidized within the RPF through a self-cleaning process called passive regeneration, using exhaust heat created under normal operating conditions. When the

exhaust temperature is incapable of oxidizing the PM, the RPF filter reverts to active regeneration with the injection of diesel fuel to help burn off the PM.

Hoy observed a John Deere IT4 engine at a John Deere test facility. He saw that engine torque was within 3/10% between soot load and fully cleaned after regeneration with the RPF system. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development requires test measurement tolerances to be within 0.5–1%, so the Deere result is within the measurement requirements. “I do have the conclusion that Deere has a very well designed system here. There is no guarantee that similar systems from other manufacturers will be well designed, so we are going to ask that that this type of performance information be recorded and supplied to us,” says Hoy. Deere told Canadian Biomass that it will be using the same base technology for all off-road markets, including cut-to-length, bundler, and full-tree systems being marketed in Canada.

For the time being, the Nebraska Tractor Test Lab will not be conducting these

We hope you’re enjoying your free issue of Canadian Biomass, bringing you the latest on this rapidly changing industry, and its evolving opportunities.

To make sure you’re on our list as a regular subscriber, follow one of these three easy methods:

1) Email Carol Nixon at cnixon@annexweb.com, and she’ll handle the rest.

2) Visit www.canadianbiomassmagazine.ca and sign up in our subscription centre. Ask for our free e-newsletter while you’re there.

3) Fax your request to 519-429-3094, including an email address or phone number to get back to you.

...all the time

additional tests related to the IT4 technology, but will be recording manufacturer results on the NTTL reports. They are currently working at developing the necessary standard tests. The reports will also require mention of any special conditions for regeneration of the RPF. Hoy explains that the Deere system does not require any, and an operator might not even know it is going on, but says, “It is possible, due to a system design, or the operating conditions, that the tractor might force you to stop what you are doing and let the system regenerate. If that is the case, we want it to be identified.”

Joe Mastanduno, product marketing manager, engine/drivetrain, with John Deere Construction and Forestry, adds that when it comes to getting the best durability and reliability from these new IT4 machines, operator and maintenance training at the outset is a good idea. “There are some issues that need attention when using IT4 machines, including using the proper fluids (oil, coolant, fuel) and proper maintenance of the diesel particulate filter. As with any machinery, the proper maintenance and operation is key,” he says, adding that Deere has a bulletin on these issues.

Another major off-road player, Caterpillar, is using a combination of DOC, DPF or RPF, and a Cat regenerative system (CRS) that removes trapped soot. The CRS is controlled electronically and its operation is transparent to the operator.

With the two main IT4 technologies now firmly entrenched in most manufacturers’ programs, the choice will be either an SRC or RPF system as the main component. They will likely be seen on virtually every Tier 4 Final engine by 2014, unless some other new technology is developed in the next few years.

For those in the market for new gear, the question might be whether to buy a Tier 3 or IT4. One issue may be cost. Research and development costs are high. The EPA admits there will be an additional cost to equipment, anticipated in the range of 1–3% of the total purchase price for most off-road diesel equipment categories.

Hoy says that IT4 regulations were implemented three years earlier for on-road diesel engines and there was a large pre-buy of diesel trucks in the transport industry. And some bugs had to be worked out of the new technology. However, the off-road sector had three additional years to finetune the technology. Whether to wait to purchase the new technology (some 2010 models may already have the technology) may be a matter of personal preference. •

WWith the search on for new markets for Canadian pellets, South Korea holds potential.

By Gordon Murray

ho knew that being executive director of the Wood Pellet Association of Canada could be such a hazardous job? On the afternoon of November 23, 2010, I flew from Bejing over Yeonpyeong Island en route to Incheon City, South Korea, just 80 km to the east. Imagine my surprise when I arrived at my hotel and turned on the news to discover that, while I was in the air, North Korea had been firing dozens of artillery shells at the island and South Korea was returning fire!

The purpose of my trip was to promote Canadian wood pellets to South Korea and to give a presentation at a biomass energy seminar hosted by Incheon Metropolitan City. The South Koreans wanted to learn about European experiences with biomass energy, particularly co-firing, and about Canada as a potential source of wood pellets.

Although South Korea is a tiny country, just slightly larger than the province of New Brunswick, it is the world’s tenth largest energy consumer, fifth largest oil importer, and second largest coal importer. It produces about 64% of its electricity from fossil fuels.

South Korea presents a great opportunity for Canadian pellet producers. The country has become serious about reducing greenhouse gas emissions and has committed to a 30% reduction in CO 2 emissions from projected levels by 2020. The government has directed 374 of the country’s largest companies to reduce emissions by 30% by 2020. The companies, which include 78 petrochemical producers, 57 paper and wood manufacturers, 36 power generators, 34 steel manufacturers, and 31 electronic chip manufacturers, are required to submit action plans to the government by mid-2011 and must begin making meaningful emissions reductions

starting in 2012. In addition, the Korean government has introduced renewable portfolio standards that require coalfired power generators to begin producing a minimum of 2% renewable energy by 2012, increasing by 0.5%/year until 2020, at which time they will be required to produce a minimum of 10% renewable energy. At least 60% of renewable energy is expected to come from biomass, i.e., wood pellets, leaving about 40% for other sources such as wind, solar, and tidal.

The power sector presently consumes 75 million tons/year of coal. With economic growth, it will likely consume more than 100 million tons/year of coal by 2020. For 2012, wood pellet consumption by the power sector will likely be at least 1.4 million tons/year (calculated as 75 million tons of coal times 2% renewable energy times 60% biomass times 1.5 tons of wood pellets per ton of coal). By 2020, wood pellet consumption should increase to at least 9 million tons (calculated as 100 million tons of coal times 10% renewable energy times 60% biomass times 1.5 tons of wood pellets per ton of coal). To put this in perspective, the European Union presently consumes about 9 million tonnes/year (9.9 million tons/year) of pellets.