Building

The critical need for data-driven fire safety in Indigenous communities By Len Garis and Mandy Desautels

I recently gained a new appreciation for the challenges of public safety education after witnessing a number of breaches in a single afternoon on my home front beach.

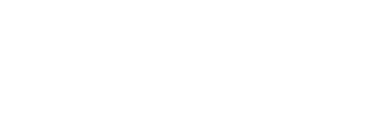

I live in a resort town and primarily powerboating community. It’s a common weekend day to anchor off the beach’s shoreline and socialize in the shallow waters. One Sunday, I watched two children in life jackets swimming right in the line of fire where jet skis and powerboats rip by the shoreline. On Aug. 1, in Sudbury, Ont., a boat struck and killed a 52-year-old accomplished swimmer. In Vancouver, a 10-year-old died and another was critically injured when their inflatable was hit by a powerboat. The two little heads bobbing around in my view this particular Sunday could be easily missed and were out significantly farther than other swimmers.

I witnessed a jet-skier using a young child as a spotter for an even younger one on a plastic raft of sorts being towed behind. Looked like fun, but in Ontario you legally

need to be 13-years-old to be a spotter for water sports. This same jet ski proceeded to bomb into shore under speed. It’s illegal to operate a vessel faster than 10 km/hr within 30 metres of shore. I saw with a very young child, perhaps three years old, being carted around in deeper waters without a life jacket. How easy it can be for an upset wee one to slip out of wet hands. Accidents happen so fast. Toddlers are safest, always, in jackets.

I regularly see swimmers congregate over the end of anchor lines, a real recipe for getting a foot carved up by the anchor. It was not a safety Sunday. It is also far from the only day I have seen questionable, dangerous or illegal behaviour.

Ontario has seen a jump in drownings this year. By the end of July, the OPP reported more than double in eastern Ontario than the year before. There has also been an increase in fatal boat crashes. The summer has been hot, and with the heat comes more flocking to the water. Canada is home to many new-

comers, and they may not be as educated on water safety as citizens who grew up around Canada’s many lakes and rivers.

Life jackets are to water safety pub ed what smoke alarms are to fire prevention. And we know, that despite decades of messaging, there are still homes without working smoke alarms — and still people without life jackets who ought to have them on.

Medical calls, including water rescue, are a big part of many fire department’s reality. Incidents around water are increasing. Increased police presence on the water is key. But, perhaps there is more that fire departments can do to help with water safety in their communities, including messaging around common sense behaviour in the increasingly hot summer months.

LAURA AIKEN Editor laiken@annexbusinessmedia.com

1,400

international firefighters have helped fight Canadian fires so far this year. (Jordan Omstead, The Canadian Press)

As of Aug. 6

6,625,375

hectares of land in Canada have burned due to fires, which is about 140% higher than the same date in 2024 when 2,785,140 hectares were burned, reported the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.

MORE THAN 600 American firefighters have traveled to Canada this summer to help battle those wildfires, the U.S. Forest Service reported in July. (CBS News)

In Canada, around 450 people are victims of drowning each year. Drowning is the third leading cause of injury related death for children under 14. July is the deadliest month for drownings in Canada. (Google)

Canada’s 2025 wildfire season is now the second-worst on record.

The latest figures posted by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre suggest the fires have torn through 72,000 square kilometres, an area roughly the size of New Brunswick.

That surpasses the next worst season in 1989 and is about half the area burned during the record-setting 2023 season, according to a federal database of wildfire seasons dating back to 1972.

Climate change, driven by the burning of fossil fuels, has made Canada’s fire season longer and more intense, scientists say. The last three fire seasons are all in the 10 worst on record.

“We really need to do a lot more to manage our forest, to reduce the impact of climate change and better prepare the communities that are at risk,” said Anabela Bonada, managing director of climate science at the Intact

A helicopter refills a bucket of water at Cameron Lake off Highway 4 where the Wesley Ridge wildfire continues to burn out-of-control near Coombs, B.C., on Sunday, August 3, 2025.

Centre on Climate Adaptation at the University of Waterloo.

This season has displaced thousands of people and stifled communities across Canada with wildfire smoke.

Manitoba and Saskatchewan account for more than half the area burned so far, but British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario are all also well above their 25-year averages.

Meanwhile, the military and coast guard were called in to help fight fires in Newfoundland and Labrador this week.

This season has put a strain on Canada’s firefighting resources.

The country has been at its highest preparedness level since late May, relying on international help to tackle the fires.

There were 446 international firefighters in Canada as of Friday, said Alexandria Jones, a spokesperson for the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, which co-ordinates Canada’s firefighting response.

This season has officials exploring partnerships with countries whose fire season doesn’t so closely overlap with Canada’s, unlike the United States, Jones said. More firefighters are coming from Chile, Costa Rica and Mexico this year than in years past.

In all, about 1,400 international firefighters have helped fight Canadian fires so far this year.

“It is very exhausting work, and it does have impacts on mental health and so we’re very cognizant that our crews start to get tired,” Jones said in an interview Friday.

“That’s another justification why we bring in more international resources.”

Bonada, the University of Waterloo expert, said this season has underlined the importance of better preparing for intensifying wildfires.

Along with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, she pointed to a slew of possible changes to help communities prepare for the future.

At the local level, she suggested communities should be integrating fire breaks into their design, planning safe evacuation routes and completing annual emergency planning exercises, among other things.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 8, 2025

The province has released the findings of a comprehensive value-for-money audit of the Nova Scotia Firefighters School.

“The results are clear, and they are appalling. We are ending our relationship with the school and will set up an interim training plan for firefighters right away,” said Kim Masland, minister of emergency management, in a press release.

“Our firefighters respond when other people’s lives are on the line. They need and deserve, at minimum, a safe place to train. We’re going to ensure they have one.”

The value-for-money audit was commissioned in June to help ensure the safety of students and staff at the school. This stems from the preventable death of firefighter Skyler Blackie during a training exercise in 2019.

A steering committee for firefighter training will be established in Nova Scotia in near future.

Key findings from the report include:

• systemic and governance issues

• a breakdown in safety accountability

• lack of stakeholder engagement

• inadequate governance and oversight of the executive director

• eroded public trust

• lost confidence of firefighters. The audit revealed a failure to uphold a culture of safety; unaddressed safety-related deficiencies; a lack of strategic planning; and a decline in infrastructure.

A steering committee for firefighter training will be established in the coming weeks to oversee an interim training plan and to guide the work on a long-term, comprehensive training model for firefighters once the results of a broader fire services review are in. The goal is to have the interim training available by fall.

The broader fire services governance review is a second, separate review being led by the Fire Service Association of Nova Scotia and focusing on governance, operations, communications, funding and more.

“We look forward to reviewing the report in detail. The fire service in Nova Scotia requires effective and consistent training to support the retention, recruitment and operational readiness of fire service members,” said Greg Jones, president of the Fire Service Association of Nova Scotia, in the press release.

“This report, along with the fire and associated services governance review, is critical to gaining a full understanding of the challenges and opportunities ahead.”

More than 680 firefighters from across the province participated in the value-for-money audit, along with 52 fire service leaders and eight members of the board of directors of the Nova Scotia Firefighters School.

STEVEN GOODE is the new fire chief for the Guelph Fire Department in Ontario. He has been with the department since 2017, serving as deputy chief of fire operations where he demonstrated decisive leadership abilities and a strong understanding of organizational functions.

The Township of West Lincoln appointed ZOLI RAKONJAC as its new deputy fire chief. Rakonjac became a volunteer firefighter in 2010 with West Lincoln Fire and Emergency Services and has served in multiple leadership roles.

Oshawa Fire Services promoted LANCE FASS to the role of deputy fire chief. Beginning as a frontline firefighter, he has played an instrumental role in shaping the department’s high standards through his active involvement with the Oshawa Professional Fire Fighters Association and key contributions to corporate initiatives.

ROB PILON became the new fire chief in Meaford, Ont. Pilon brings more than two decades of experience with the Meaford Fire Department. He began his career as a firefighter in 2004, and has since held several leadership roles, including deputy chief and most recently interim fire chief.

The City of Belleville appointed KYLE CHRISTOPHER as deputy fire chief. He began his career with Belleville Fire and Emergency Services in 2005 as a volunteer and progressed through the ranks. He also volunteers with the Tyendinaga Township Fire Service.

South Glengarry Fire Services welcomes BILL CHAFE as its new deputy fire chief. He brings both professional leadership and lived experience to the role as a former teacher and volunteer firefighter.

East Gwillimbury Fire and Emergency Service made STEVEN COOK its deputy chief of operations. Cook joined East Gwillimbury as a paid-on call firefighter in 2004 and was later hired full-time and promoted to the rank of captain in 2012. Prior to joining the East Gwillimbury department, he was a fulltime firefighter in the Town of Georgina.

Ret. Fire Chief MATTHEW PEGG will be Ontario’s new deputy minister of emergency preparedness and response starting Oct. 6. He retired from his role as fire chief for the City of Toronto last year and has since led mental health support for public safety personnel. He is also a keynote speaker inspiring the industry.

TONY QUESNELLE has been promoted to deputy fire chief at Honda Canada Manufacturing (HCM). He has previously served 16 years as a volunteer firefighter and worked at HCM for 26 years including their emergency services team.

Fire Chief KAREN ROCHE has announced her retirement, effective April 30, 2026, from the Burlington Fire Department. With a career spanning more than 30 years in the fire and emergency services sector, Roche was appointed Burlington’s fire chief in 2020.

The long-serving fire chief of the Keremeos and District Volunteer Fire Department, JORDY BOSSCHA, announced his retirement. He has stepped away from his leadership role after 37 years of service as a firefighter and 27 of those years as chief of KVFD.

Ret. Fire Chief HARRY NELSON passed away July 22. Nelson was a member of the Greenfield and District Fire Department in Nova Scotia for over 40 years; 23 of those years he served as chief. He was a director for the Nova Scotia Firefighter School and a member of the Nova Scotia Fire Chiefs Association.

CLOCKWISE:

North River District Fire Brigade, Sherbrooke & Area Volunteer Fire Department, Montreal Metropolitan Airport, Pasqua First Nation, County of Paintearth No. 18 Protective Services, Bowen Island Fire Rescue.

This pumper tanker delivered by Fort Garry Fire Trucks was built on a Freightliner M2 112 chassis and powered by a Detroit DD13 505 HP engine and Allison 4000 EVS transmission. It also features a cross control pump panel with the Hale DSD 1500 midship pump and a co-poly 2000 IG water tank.

This E-ONE HP100 platform was built on a Thyphoon chassis with a Cummins X12 500 HP engine and a 4500 EVS Allison transmission. Features include Federal Signal lighting package, 6 kW Onan generator and 3480 StreamMaster II gun on the ladder. The apparatus also includes the PA300 electric siren and Q2B from Federal Signal.

4

This Oshkosh Airport Products 6x6 Sriker holds seating for four and is powered by a Scania DC16 V8 670HP engine. The apparatus also includes a 12,500 L water tank and a 1,600 L foam capacity, also utilizing the Eco-EFP foam management system.

Delivered by Fort Garry Fire Trucks, this MXV Wildland fire truck was built on an International HV 507 chassis and has a 350 HP Cummins L9 engine paired with an Allison 3000 EVS transmission. The black-coated aluminum pump panel features a Darley PSP1250 pump and a co-poly 1000 IG water tank.

Built on a Freightliner M2 106 chassis with a Detroit DD8 350 HP engine and Allison 3000 EVS transmission, this Fort Garry Fire Trucks apparatus includes a top control pump panel with a PTO-driven Darley PSP 1000 pump, 1000 IG co-poly water tank, and a FoamPro 2001 Class A system.

This Fort Garry Fire Trucks mini pumper was built on a Ford F550 chassis, and is powered by a Powerstroke 6.7L V-8, paired with the TorqShift 10-Speed transmission. Includes a 5083 aluminum body, side control pump panel with a Darley LSM1000 pump, and a 300 IG co-poly water tank.

With over 60 years of experience, Smeal delivers one of the industry’s most trusted lines of premium, custombuilt aerial apparatus—engineered to meet the unique needs of fire departments in rural, metro and urban communities. Backed by a professional nationwide dealer network, Smeal provides expert local support and service you can count on, from build to deployment and beyond.

Built for performance. Backed for life. Always Pu ing First Responders First.

Scan for more information, or contact your Spartan Emergency Response dealer today.

By Chris Harrow, Director of Fire Services, Town of Minto and Township of Wellington North, Ontario

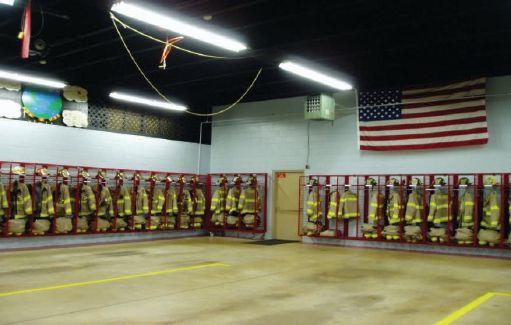

Recently, I had the pleasure of being able to visit multiple fire departments across our great country. I saw many different organizations and firefighters from all walks of life serving their communities in various ways, all dedicated to their departments and receiving very little compensation to do so. What I also witnessed were great examples of leadership from numerous senior officers under many different circumstances. It was both refreshing and a great learning experience for me and my passion for leadership.

During the tours, there were numerous examples of respected leaders. Many were respected by their peers because of how they lead by example. They were the first to be seen at the station, completing paperwork all hours of the day and jumping in with their personnel at calls and training. Leading by example was prevalent in most stations I had the opportunity to visit.

The situation caused pause for thought as leading by example is something people in leadership positions tend to forget. Many new captains that I have personally witnessed forget that leading by example and earning the respect of their firefighters is what got them to the promotion in the first place.

In the volunteer sector, many new officers no longer think they need to participate in regular training sessions. They stand back and let the “younger ones” get the learning they need. It is forgotten that sometimes the best way to learn is to have the officer complete the training with you and teach as they go. It’s as if the new coloured helmet is a ticket to stand back and give instruc-

Firefighters tend to respect leaders who are in the trenches with them, demonstrating that they have the knowledge and experience to back up any orders or tasks they request to be done.

tions instead of demonstrating and completing tasks.

Firefighters tend to respect leaders who are in the trenches with them, demonstrating that they have the knowledge and experience to back up any orders or tasks they request to be done. Firefighters witness firsthand the abilities of their leader and gain respect for them. Whether it is donning an SCBA in practice and doing search and rescue with them on a 35 C day or being the first one to grab the wash brush to clean the truck when you get back to the station, respect is gained by these small gestures.

It seems like such a simple concept that respect is earned from your peers and cannot be demanded. Many officers for whatever reason believe that as soon as their promotion occurs, they are immediately respected because of their rank. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Firefighters must listen and receive orders from their superiors, but they do not have to respect the person giving them. For a majority of officers, this is common sense, but for too many it is not obvious to them.

Gaining respect of your personnel comes naturally to many people. Those are the people that rise to the top of any candidate pool for future promotions. For the others, you try and teach the concept of earning respect. However, many cannot get the concept and continue to think it is an automatic occurrence once rank is achieved. It is very frustrating sometimes that they think that strutting around like an officer on Chicago Fire will gain you the respect you think you deserve.

Observing firefighters in different

Chris Harrow is the director of fire services for the Town of Minto and Township of Wellington North in Ontario. He can be reached at c.harrow@mintofiredept.on.ca.

areas of our country gives a great perspective for those of us that have been in the fire service for a long time. There are still many in our country who are true volunteers and receive no compensation for their work. They do it for the community and the respect they get for dedicating so much time. As a colleague of mine said, the social card that these departments have in their communities is truly commendable.

Many departments still must fundraise money to purchase equipment needed for them to complete their tasks on a daily basis. All of this is done on top of the regular duties of training and responding to calls. These campaigns in the community and within the fire stations would not be possible if the firefighters and the community did not respect the ones leading the organization. Again, all of this is earned in the community, not demanded. People in the community would not give their money in fundraising efforts if there was a total lack of respect.

I am privileged to be able to get out and visit various fire stations in Canada. If anyone has the chance they should jump on it. The perspective it gives you makes doing your day job in a fire station so much better. It shows the battles and the efforts various people must put in to survive. But it also gives you a grounded message that no matter how complicated things may be in your department, the basic concepts of leadership will always be true. Work to gain the respect of your coworkers, don’t expect it to be automatic. At the end of the day, it will make you a better person knowing you have worked hard to earn it.

By Joey Cherpin

Advancing effective fire fighting tactics.

Author’s note: This article is written in U.S. measurements (U.S. gallons/ pounds per square inch of pressure) as that is how the nozzles and appliances are manufactured. There are often errors in conversions when liters are converted to gallons or vice versa, if imperial gallons are mistakenly used as the measurement, or when nominal measurements are converted literally. This article also discusses the application in regard to 1.75” hoselines, not 2.5”. Many benefits listed for the 1.75” apply to the 2” and 2.5” hoseline as well, with even greater benefit in some cases.

Fire departments have seen or are starting to see the reversion

of the service’s tactical culture back towards engine work. Hose and nozzles, and confinement and extinguishing are attractive topics. The idea of a smooth bore paired to high quality hose intrigues firefighters and officers who envision a more effective fireground. They are looking to make things easier for their members, and to create and maintain survivable space for any possible fire victims. There is a valid case for the return to low pressure lines, but often the conveyance is where the message can be lost. Undoubtedly, whether smooth bore or a combination fog, a 50 psi nozzle flowing greater than 150 GPM being pumped correctly and placed accurately has many benefits and is the premier choice for handlines when considering effectiveness and safety.

Many fire departments are using combination fog nozzles that operate at 100 PSI to flow 95-125 GPM maximum in a selectable gallonage combination nozzle. This gives a nozzle reaction (NR) force of 48 to 63 lbs. This flow rate can be effective in many applications. A room and contents fire in a dwelling is often easily managed by this flow. Once that room reaches flashover, results will diminish. Results are impeded

Easy, intuitive cleaning for hard-working gear.

Smart-Wash Extractors deliver advanced cleaning through intelligent controls. Pre-loaded NFPA-compliant cycles optimize every wash, ensuring consistent, thorough decontamination. New cycles can be easily uploaded via the USB port, keeping your system compliant and future-ready. New standards. New programs. No problem.

further when the fire extends beyond the room of origin, and the structure itself becomes involved in fire. Fire departments using these nozzles will frequently find themselves fighting the fire, not simply extinguishing it.

Bear in mind, legacy often refers to furnishings of the 1970s and earlier, prior to the dominance of synthetic materials. Wood, cotton, and typical class ‘A’ materials with lower heat release rates were commonplace. Underwriter Laboratories, NIST, and others, have all released data on legacy versus modern furnishings, legacy versus modern construction materials, legacy versus modern fuel loading, and legacy versus modern building layouts. The synopsis of the research is simple: rooms are now larger, rooms hold more fuels than before, and the fuels in the rooms have a higher heat release rate during combustion. The rate of 95 to 125 GPM does not have the same extinguishing effect it used to. This is a driving influence to increasing flow rates at structure fires.

It is commonly accepted that 150 to 175 GPM is the sweet spot for flow from a 1.75” handline. NFPA, and many subject matter experts support this target. Multiple departments have conducted thorough nozzle evaluations with findings that correlate and support the 150 GPM and higher theory.

Flow rate is not the sole solution to a better extinguishment. Manageability is as important, if not more. The accurate placement of a water stream is the only factor that determines if the volume delivered will provide extinguishment. A difficult to manage hoseline will prohibit nozzle management and water placement, making the increased volume a nil effort.

The lowest industry accepted nozzle pressure is 50 PSI and the highest accepted flow rate for a nozzle has to do with the hoseline behind it. John Freeman developed the ‘Freeman Ratio’ for smooth bore nozzles in the late 1800s. The Freeman Ratio states that the (smooth bore) nozzle outlet diameter should be half of the

A selection of 50 PSI/ 350 KPA nozzles, in smooth bore and fog varieties.

hose’s inside diameter. This results in a four times increase in water velocity from hose to nozzle. Half of a 1.75” hose is 7/8. A 15/16 nozzle is .9375 of an inch, and doubled is around 1.88”. The 1.88” is a common actual diameter

Evaluate attack packages and quantify flows and pressures before placing them into service.

of marketed 1.75’’ hose. The 7/8” and 15/16” smooth bores flow 160 and 185 GPM at 50 PSI respectively. When considering both the lowest operating pressure and the highest recommended flow rate for a hose size, a 15/16” at 50 PSI is

at the top end for flow and manageability. The 7/8” nozzle has a nozzle reaction of 59 pounds, and the 15/16” has a reaction force of 69 pounds. One is slightly higher and one slightly lower than the 125 GPM at 100 PSI (NR of 63 lbs). This uses substantially more water, with minimal change in nozzle reaction. A 100 PSI stream will have a higher stream velocity, but maintaining the desired flow rate of 150 GPM or higher does not equate to a desirable nozzle reaction force. Selecting a nozzle and target flow rate requires additional research beyond this article. It is the opinion of myself that the 7/8” smoothbore at 50 PSI is the optimal balance of flow, impact, and nozzle reaction. The 15/16 should not be disregarded either, as the additional 25 GPM is a fair return on investment for another 10 lbs of nozzle reaction through the same size (nominal) hoseline.

Readers should note that the Freeman ratio can be used in application with fog nozzles as well. Take the ratioed smooth bore flow and consider that as the appropriate fog nozzle flow and pressure for that hoseline. In the case of

a 7/8” smooth bore, the equivalent would be a 160 GPM at 50 PSI combination fog nozzle. Trying to get more water out of a Freeman ratioed hoseline results in substantial friction loss increases. Flowing much less only results in unneeded water weight and lower tube velocity which would otherwise help kick out kinks. If you plan on sticking with 125 GPM, stay with a 1.5” hose.

Fire fighting is inherently dangerous as we know, but if something as simple as a new nozzle can drastically reduce our risk, then it becomes sensible to make the switch. The U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) publishes all reported U.S. firefighter line of duty deaths (LODDs), including cause of death. At the time of writing this, the USFA LODD data includes reports for 3643 deaths from Jan. 1, 1990 to current. One thousand four hundred and sixty two (40 per cent) are declared as heart attack or heat exhaustion as the cause

of death. This data does not take into account cancer related deaths.

The lower pressure with higher flow rates results in a more rapid fire suppression with less nozzle reaction. This minimizes working time overall, reduces interior temperatures much more rapidly, and reduces exertion by firefighters. There is no real data to correlate, and it is very presumptive, but one can formulate that reducing working time and working conditions will be favourable for firefighters working in the environment. It also makes the fire environment more tenable for possible victims by quickly controlling fire and reducing its effects.

Change must be system wide. Unfortunately, many view the nozzle as the sole piece of the puzzle. There is one significant downside to halving the nozzle pressure; the hose may become “whippy.” One hundred PSI maintains significant rigidity, minimizing hose whip.

Flowing in the 150 or 160 GPM-plus range at 50 PSI results in lower nozzle reaction than 100 PSI, but the lowered residual pressure does not maintain hose rigidity. It is up to the construction of the hose to maintain rigidity at the lower pressure. The only real way to determine if your hose is adequate is to test it. Nearly every hose manufacturer has an ‘antikink’ hose construction like the Matex Cobra Combat fire hose.

It is worth noting that higher pressures in 2.5” hose actually restricts nozzle movement due to the mass of the water in the line. The 2.5” is very difficult to bend and maneuver at 100 PSI. A beneficial consequence of the mass of water in a 2.5” hoseline is that hose whip will not be

induced by common 50 PSI flow rates. The hose does not require the same rigid construction features and although some hoses are better than others, nearly all common 2.5” hoses will support a 50 PSI nozzle without hose whip.

Use the 2.5” more liberally. Knock it down. If you’re not flowing enough, you’re not flowing enough, so pull the big line when you need it, reset the fire, and get to work with the 1.75”. No shame in doing the job well with what you have.

Seek out a demo. Companies like Elkhart Brass and their Canadian dealers typically offer free hands-on demos which include flow testing, trialing different hose/nozzle combinations, and getting to try out many various appliances.

Wholesale change can be expensive. Start with hose. Purchase a unique colour and use it as the nozzle section on each preconnected hose line. Once you have a stronger, kink-resistant hose on the nozzle section, you can slowly start purchasing 50 PSI nozzles. From there, replace hose on a regular basis and you can change a single apparatus up to a large fleet at whatever pace works for your budget.

The information and wisdom written above has been collected from numerous fire service mentors and instructors, whose names would generate a list to large to fit.

Joey Cherpin is the deputy fire chief in Edson, Alta., supporting the paid-on-call membership. He runs a small training company that focuses on rural operations and hosts the annual training conference Engine Company Fundamentals.

By Andrea Perchotte

Managing chaos, battling exhaustion, and enduring discomfort are all in a day’s work for a firefighter. But when the gear comes off, personal struggles often surface. Canadian fire personnel face an elevated risk of depression, alcohol misuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) according to researchers (Cramm et al., 2020). While the settings of a counsellor’s office, a 12-step meeting, or a gym can assist with turning the corner on these issues, there is a growing number of alternative, transformative environments that offer paths to recovery. Across Canada, yoga studios, Nordic spas, and makerspaces are emerging as powerful destinations for healing and growth.

Troubled by a senior colleague’s remark about anticipating mobility issues from years on the job in Edmonton, 23-year veteran firefighter Tim Seutter stepped into a space that would set him on a life-changing trajectory: a yoga studio.

“Yoga helps you slow down, process life, be in the present and learn you don’t have to think of calls and terrible things you have seen,” he says. “When those creep up, you can learn to deal with them, breathe through them, instead of reliving them.” While Seutter emphasizes the value of the mental side of getting on the mat, he also points out the physical benefits such as improved range of motion and ability to both run and lift weights.

After the challenge of relocating to New Zealand with a young family 12 years ago, yoga became a way for Seutter to connect with himself and his new colleagues, which led him

ABOVE Edmonton

to deliver classes at the fire station. Encouraged by the improvements he saw in the overall vitality of his crew members, Seutter took yoga teacher training. Following that, he founded Yoga Fire.tv – an online platform for classes ranging from relaxing “yin” sessions to strength-focused “power” yoga. Other common styles yogis practice includes “hatha” which is an introduction to basic poses, “vinyasa” which emphasizes cardio and strength, and “ashtanga” which is more physically demanding.

Seutter explained: “We see pretty traumatic and horrific things every shift and multiple times a day. Without good tools, years and years of this trauma builds up and unfortunately many firefighters can get PTSD.”

For over 105 years, Fort Garry Fire Trucks has built fire apparatus trusted by departments across North America. Every truck is engineered for tough road conditions and frontline performance—designed by Canada’s largest fire apparatus engineering team and backed by a reputation for durability and innovation.

We’re proud to be a sponsor of Fire-Rescue Canada 2025, hosted by the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs in Winnipeg, Manitoba. If you’re attending, we invite you to join us on Tuesday, September 23 for an exclusive Fort Garry plant tour, our Manitoba Social Night, and evening Hospitality Suite.

Scan the QR code to register as spots are limited.

We also have a lineup of stock trucks available for immediate purchase, including several of our most in-demand models:

• ER Pumper 4-Man Crown – Built on an International chassis with a 350 HP Cummins L9, 800-gal tank, and Hale DSD1250 pump. Features a full Whelen emergency lighting package and Gentili drop-down ladder rack.

• ER Pumper Side Control – Available on HME 1871 and HME Spectr II chassis—combine proven drivetrains and high-flow Hale 1500 USGPM pumps with 1000 IG water tanks.

• 4-Door Liberator Side Control – Mounted on a Freightliner M2 crew cab with a 350 HP diesel, 1250 GPM Darley pump, and versatile response features.

Whether you’re looking to buy or just stopping by during the conference, we’d love to connect.

For availability and pricing, contact your local Fort Garry sales representative. Not sure who to speak with? Call 1-800-565-3473 and our team will connect you.

When readiness matters, trust One Tough Truck.

While settings based on traditional practices make for soothing decompression zones, contemporary ones do too. As the technology and do-it-yourself culture evolved in the early 2000s, makerspaces – also known as hackspaces – gained momentum. Located in schools, libraries, and public as well as private facilities, a listing of makerspaces across Canada can be found at hackspace.com.

Participants have access to a wide variety of equipment from 3D printers and laser cutters to power tools and Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines which are computer-controlled and used for automated machining. These creative environments spark innovation, learning, and problem-solving. Makers of all ages collaborate while building confidence and exploring woodworking, photography, music, and more.

Cameron Bennett, a 20-year veteran of the Canadian Armed Forces reflects on a concern shared with many fire professionals. “In our line of work, we’re trained to take action, to respond to emergencies, to fix what’s broken. But when our careers end or injuries happen, that sense of purpose can get lost.”

After facing his own struggles and discovering blade smithing post-service, Bennett’s journey evolved from navigating fear, doubt, and anxiety to experiencing improved sleep, focus, and concentration, drawing him into the maker movement. Vowing to “rebuild” himself and others, Bennett founded Forging Ahead, a not-for-profit charity based in St. Adolphe, Man., south of Winnipeg.

Offering a “therapeutic and supportive space”, the organization welcomes first responders and veterans, providing encouragement while they manage mental health issues and engage in artistic blacksmithing and metalworking.

“In the forge,” Bennett explained, “The noise of trauma, the weight of experiences we carry—they get pushed aside…by the need to be fully present…You don’t have to be ‘creative’. You just need to show up, take a breath…it’s about giving your brain and body something meaningful to do.”

His thoughts are echoed by a study of 7,182 adults which concluded that engaging in creative arts and crafting enhances personal happiness and, “a sense that life is worthwhile” (Keyes, H., et al., 2024). Bennett added, “I’ve

seen big, tough guys walk away from a day in the forge with tears in their eyes—not because they were weak, but because for the first time in years, they felt seen and capable again.”

Creative outlets like these can reduce stress, providing a chance to recharge and prepare for the challenges ahead. In the future, though, the primary role of firefighters will continue to be to put out fires. But there’s one area

that should never be extinguished: one’s own self-care. Together, fire personnel - along with other first responders can make healthy living more accessible by collaborating with wellness destinations negotiating extended hours, special rates, and vitality-boosting events. By fanning the flames for a vibrant future, well-being can be woven into firehouse culture and beyond.

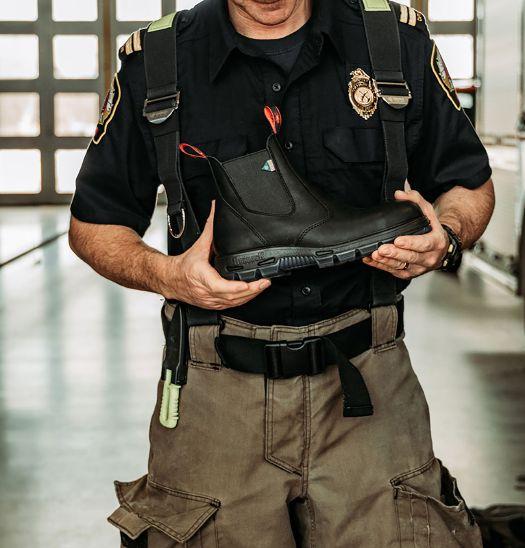

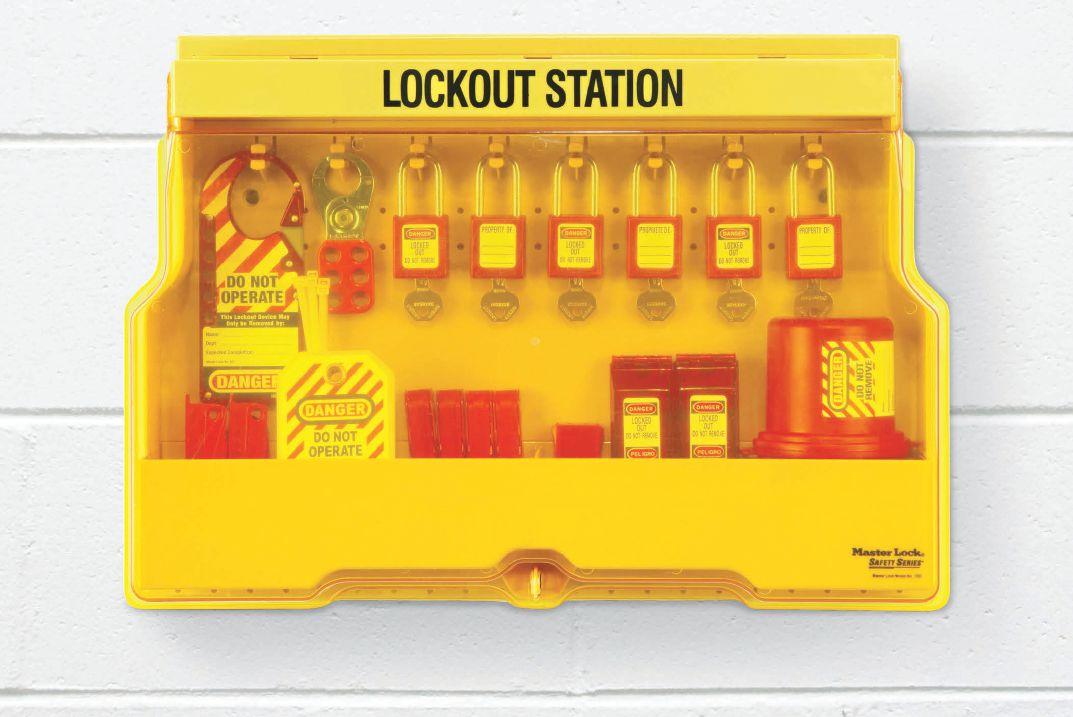

Historically dirty personal protective equipment (PPE) was a rite of passage; a sign of hard work completed. Probationary firefighters would start their careers and witness the soot filled helmets and dirty bunker gear and reflect in awe. The reality is, however, that every year 50 to 60 Canadian firefighters die from cancer. It is imperative that post decontamination practices, such as preliminary exposure reduction (PER) are developed, implemented and adhered to. These practices must also include PPE cleaning and turnout gear laundering as soon as possible after an incident. These measures are an important way to mitigate risks posed by contaminated gear.

Workers’ compensation claim data suggests that cancer is the leading cause of occupational mortality among firefighters. The BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit determined that 85 per cent of work-related fatality claims of firefighters between 2007 and 2021 in Canada were cancer-related. Firefighters are exposed to a variety of toxins when synthetic fibers such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) burn, hence the necessity of on-scene decontamination and PER (utilizing air, brushes or water) and timely proper cleaning of turnout gear (laundering using extractors) process.

Current statistics indicate that PER using the wet-soap method reduces carcinogenic exposures by a median of 85 per cent present on turnout gear after fire fighting (Craig A. Haigh, fire chief, Hanover Park, Ill., and National Institute of Medicine). When using the wet-soap method it is important to ensure the environmental impact is considered by capturing contaminated runoff should it be required. Contaminated runoff can be captured in shallow hazmat pools and pumped

into totes for proper disposal at a later time.

Further reduction of contamination can be achieved by having policies or procedures in place for mitigating contaminated gear on scene after doing PER as well as having a process in place for transporting contaminated gear back to either the department’s laundry facilities or a pickup location for an Independent Service Provider (ISP) who does the extracting. In an ideal world, dispatching a decontamination vehicle capable of providing a dry isolated environment for all seasons where firefighters can isolate helmets, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), gloves and boots for transport from the scene directly minimizing the spread of contaminants to vehicles, stations and minimizing exposure time. A decontamination vehicle allows responders to remove their

turnout gear in an environment that is climate controlled (warm in the winter, cooler in the summer) and provides privacy on scene. In some case departments utilize a vehicle where turnout gear can be exchanged for clean gear; however contaminated gear will still need to be transported to the department’s laundry service or ISP.

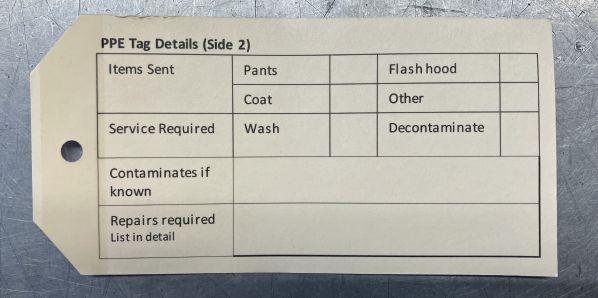

Once the contaminated gear is isolated, it is critical to have a bag and tag system to reduce further contamination while en route to the department’s laundry facility or ISP. A bag and tag system allows firefighters on scene to separate their gear, turn liners inside out and bag contaminated gear, place a tag on the bag which identifies the firefighter by their station, identifies the call number and type of contaminant the gear was exposed to. This system will also assist with tracking exposures, if necessary.

As a firefighter and now maintenance coordinator I have been present at many fires and have witnessed the evolution of my own department’s decontamination processes.

The maintenance division’s responsibility is to develop and implement robust plans and processes to ensure the health and safety of firefighters based on new and innovative

techniques all while being fiscally responsible. Ottawa Fire Services (OFS) is the largest composite fire service in Canada. OFS is unique as it covers 2790 square kilometers with 950 full

time professional firefighters and 488 volunteer firefighters, it is both geographically and logistically challenging. OFS has the ability to launder its own bunker gear and uses an ISP for annual hydrostatic testing, repairs and in some cases, they launder our gear when we are over capacity. PER and laundering turnout gear removes approximately 70 per cent of VOC and heavy metals and 99.95 per cent of biohazards. Both the ISP and OFS in-house laundry facilities utilize commercial extractors.

Currently drying is completed in tumble dryers but OFS will be transitioning to a hang dry or cabinet dryer system to meet the new NFPA 1851 standard. OFS laundry facility is an isolated room with negative pressure ventilation. During the washing process, members must be wearing gowns, eye protection, gloves and either a N95 or APR for protection against contamination by inhalation, absorption or ingestion. All members are trained and must comply with department policies regarding OFS decontamination procedures. The goal is

to reduce further contamination and exposure.

Department chiefs, division chiefs and suppression staff must work cohesively and collaboratively to coordinate the efforts necessary to ensure safe practices are in place and followed. As Ret. Captain Mark VonAppen aptly pointed out in his lecture at FDIC 2025, “firefighters hate two things, the ways things are and change.” For new practices to be implemented and adopted consistently there must be buy-in. Firefighters must understand why this is a good thing and how it will benefit them. It is leadership’s responsibility to educate, facilitate and lead by example. Regardless of position, all fire service leaders are obligated to ensure staff are educated, help to facilitate positive change and lead by example.

Moving forward, the new NFPA 1850 Standard on Selection, Care, Maintenance of Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting will be a consolidation of NFPA 1851 and 1852. This new standard will streamline the guidelines for equipment management and will highlight

the introduction of a PPE technician and PPE manager. The introduction of these new positions will aid in management of turnout gear as it relates to the new NFPA 1850 standard, including tracking of turnout gear repairs and cleaning. It will also provide an opportunity for fire services that do not currently have robust policies and practices in place, to look developing or evolving the service’s PER programs.

Ultimately the goal of having a policy and procedure with systems in place is to negate and reduce the amount of exposure firefighters are subject to. This exposure reduction is not limited to only suppression fire fighters but will include all staff who participate in suppression activities, fire investigations as well as those who are responsible for PPE cleaning and repair; essentially anyone who is subjected or exposed to byproducts of combustion.

Captain Koert Winkel is a 19 year veteran with Ottawa Fire Services. Having served 18 years as a suppression fire fighter, he recently adopted the role of maintenance coordinator in charge of logistics and procurement.

By Ed Brouwer

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., a retired deputy chief training officer, fire warden, WUI instructor and ordained disaster-response chaplain. Contact aka-opa@hotmail.com.

For the last 20 years, my wife and I have been raising Quarter horses. Along with the breeding program, we rescue, re-train, re-home and even provide an equine retirement program.

The most difficult of those programs is the re-training aspect.

With horses and humans alike, it is much harder to “unlearn” something than to learn something new. It is easier to train a completely unbroke horse than one which has had bad habits trained into it.

As fire service trainers we often find ourselves re-skilling, re-training or up-skilling. Much of this comes from acquiring new information, but also reevaluating and, when necessary, discarding outdated information.

Unlearning is not about forgetting what we have learnt, but more about letting go of outdated information. Think back over the last few years to the changes we’ve seen in our bunker gear, our SCBA and our ventilation protocols.

Much of our fire fighting training comes from repetitive actions at our weekly practices. The more we do something the more it becomes our way of doing it. It takes a conscious effort to unlearn automatic responses.

For example, on the ranch I put a lot of hours on a tractor that has a shuttle shift transmission. It allows me to change direction (forward or reverse) quickly without needing to use the clutch every time. It is controlled by a lever near the steering wheel. The problem comes when I jump into my F350 and wonder why I’m not moving forward even though I turned on my right signal light (same location as shuttle shift lever).

As much as we want our members to respond automatically to fire scene situations, those responses must be the correct and most effective respons-

es. With more aggressive tactics, hotter fires, lighter construction, and less live-fire training, firefighters are twice as likely to die inside structures as they were 20 years ago. The fire scene has changed.

A leading cause of these line-ofduty deaths is getting lost, trapped or disoriented. Considering that, when was the last time you did a drill that involved calling a Mayday?

We must update our Mayday protocols. Your members need to know the difference between emergency radio traffic and calling a Mayday.

According to standard radio terminology there is a significant difference between the two. Mayday is used to report a firefighter in trouble and requiring immediate assistance. Emergency traffic is used to report hazardous conditions or situations.

Fundamentals of Fire Fighter Skills says, “The most important emergency traffic is a firefighter’s call for help. Most departments use ‘Mayday” to indicate that a firefighter is lost, missing, or requires immediate assistance.”

Firefighters are twice as likely to die inside structures as they were 20 years ago

It bothers me that our training manuals say, “most departments use Mayday.” Every department, in my opinion, should be speaking the same thing. After all, Mayday is an internationally recognized distress signal; it comes from the French m’aider (help me).

The paragraph continues: “If a Mayday call is heard on the radio, all other radio traffic should stop immediately. The firefighter making the Mayday call should describe the situation, location, and help needed. Firefighters should study and practice the procedure for responding to a Mayday call.”

To my way of thinking that word “should” ought to read “must.”

Fundamentals of Fire Fighter Skills gives the following example of a Mayday call:

Firefighter: “Mayday… Mayday… Mayday.”

All radio traffic stops

IC: “Unit calling Mayday go ahead.”

Firefighter: “This is Engine 4. We are on the second floor and running out of air. Fire has cut off our escape route.

Whether it’s breaching doors, cutting locks, or lifting heavy materials; with the T1, you always have the right tool for the job.

T1 is the only tool that can hammer, cut, spread, lift, wedge and ram.

T1 can easily cut rebar, chain and padlock; easily replace the cutting blades when they are damaged.

Load-holding function makes the tool suitable for (progressive) lifting.

High power transmission gives you a maximum cutting force of 14,2 ton/31 248 lbf and a maximum spreading force of 3,4 ton/7 419 lbf.

We request a ladder to the window on Charlie side of the building so we can evacuate.”

IC: “Command copied Engine 4, your escape route cut off by fire. I am sending the rapid intervention team to Charlie side with a ladder.”

Sounds good, but this is how it could go in real life…

Thompson: “This is Thompson…. we need some help.”

Champaign: “Which way out?”

Champaign: “Which way out?... Everybody out!”

Champaign: “We need some help out.”

Champaign: “Firefighter needs some help out, lost connection with the hose.”

Champaign: “Can you hear me dispatch?”

Unknown transmission of a firefighter saying, “I love you.”

All throughout the recordings you hear a PASS (Personal Alert Safety System) going off in the background.

There are three more transmissions from Champaign, “In Jesus Name…”, then no audible…… just breathing……and then silence.

Twenty-eight minutes and twenty-one seconds into the call marked the last transmission of Champaign.

NO ONE came to his rescue! NO ONE even acknowledged hearing him, yet it is right there in the transcripts!

The recorded radio traffic included:

• Nine minutes and three seconds of calling out for help

• Ten calls for help

• Nine keyed mics

• One last breath

Only one firefighter, French, actually called a Mayday, but French’s Mayday was not heard on the fireground. I still get a cold chill thinking of him calling for help not once but three times and no one responding.

Can you imagine, six minutes waiting, hoping and praying for a response to your call for help….to no avail.

I’m not making this up – it is straight from the radio traffic transcripts of the Sofa Super Store fire in Charleston, S.C., reported as the U.S.’s deadliest single disaster for firefighters

since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Fire swept through a warehouse, collapsing its roof and killing nine firefighters inside on June 18, 2007.

But hang on, here is something you need to know: Out of the survivors, seven firefighters lost connection with hose line and their crew; two firefighters ran out of air but made it out … and NONE of them called for HELP!

We are pretty sure that within the first nine minutes of the call six of the nine firefighters lost their lives. Only three firefighters called for help. The six who never called for help had a total of 125 years of service. Only French called a Mayday and activated his EIB, Thompson called for help once and Champaign made multiple calls for help. Those three had a total of 7.5 years of service.

Over 130 years of training and service and only one called a clear Mayday!

The main problem is that then and now we have left it up to each firefighter to decide when he/she is in a Mayday situation. Therefore, we must re-train or reskill our members in the right way to call a Mayday.

With 32+ years of experience, we help municipalities and corporations enhance fire safety, efficiency, and preparedness through Community Risk Assessments, Master Fire Plans, and Fire Department Training - All tailored to your needs.

empower communities with informed decisions and strategic fire safety solutions

They must be taught the differences between emergency radio traffic and calling a Mayday. Calling Mayday must become an accepted decision!

Here is a comment from a firefighter interviewed after his rescue. “I knew I was in trouble. I thought about using the radio, but I thought, ‘I found my way in; I can find my way out.’”

Trainers must take advantage of the fact that firefighters are great at following orders. We must give clear “if-then” Mayday guidelines.

We instruct them that “if” this is happening in the thermal layer “then” this is what you do. “If” this is happening in the compartment fire “then” this is what you do. We never rely on the firefighter’s perceived need to comply with these rules. Firefighters do not usually get in trouble for following the rules. So, my question for you is, what are your rules for calling Mayday?

Analysis of the recorded radio traffic indicates that the deceased members did not attempt to call for assistance until they were in critical distress.

All the recorded messages indicate that the firefighters are lost, disoriented, and either running out of air or already out of air. They were already in imminent danger, deep inside the building, when they began to call for assistance. And even then…none of these messages were heard by a command officer on the scene. They were ignored, neglected and left unanswered…how would you feel if that was your brother or sister calling for help? Well, I got news for you – it was nine of your brothers, and they all died!

Here’s the kicker, there is no suggestion that any CFD members lost or surviving failed to perform their duties as they had been trained or as expected by their organization. The final analysis does indicate, however, that the CFD failed to adequately prepare its members for the situation they encountered at the Sofa Super Store Fire.

As I listened to the fire ground tapes and read the 44 pages of radio transmission and phone call transcripts, it became clear that the fragmented messages of distress were not heard.

There was no Mayday plan in place. Firefighters were unclear when to call a

Mayday. Firefighters had little if any idea of what to do to save themselves while waiting to be rescued.

We in the Canadian fire services need to develop clear Mayday decision-making parameters (rules that specify when a Mayday must be called) and institute Mayday training programs firefighters must take and continue to pass throughout their fire service experience. We must equip them with survival skills. NFPA 1404, sets forth the standard for air management. According to the article a firefighter is supposed to exit the IDLH environment BEFORE their low air alarm goes off. And if it goes off while a firefighter is in an IDLH environment, it is to be treated as an event comparable to a Mayday situation.

We still have firefighters using their low air alarm as an indicator to leave the building!

We still have firefighters entering burning structures without radios!

We still spend more time tying knots than we do practicing on a Mayday!

Firefighter’s Handbook 2nd Edition by Thomson Delmar states: “The first step a firefighter should take in an entrapment is to get assistance. Activation of a PASS device is warranted, and the declaration of a “Mayday” should be made over the radio….”

Did you know the PASS alarm is heard in the background during 52 radio transmissions at the sofa Super Store fire, but no reaction. Have we become so accustomed to hearing that alarm that it is no longer alarming?

One thing we need to do is “unlearn” yelling “shake” when a PASS alarm is activated during practices!

Please help me address these weak areas in our training… the lives of your members depend on your decision to stop this insanity.

Next issue I hope to help you deal with both pre and post Mayday incidents. In the meantime, stay safe a remember to train like lives depend on it … because they do — 4-9-4 - Ed. In honour of Melven Champaign (46) “…… can you hear me dispatch?”

With a Touch Screen and rotating mounting feet, installation is hassle-free

Dual Battery Type Technology enables simultaneous charging of two different battery chemistries

Optional Remote Touch Display available

By James Rychard and J. Gordon Routley

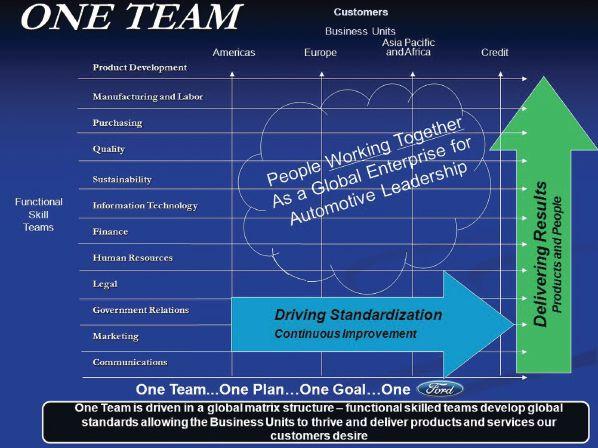

If there is one resource that no fire service leader should be without, it is Bryce G. Hoffman’s book, American Icon: Alan Mulally and the Fight to Save Ford Motor Company. Not only because of Hoffman’s true account of what transpired, or the in-depth knowledge of the inner workings that Ford Motor Company (Ford) graciously provided him, but also because the fire service can take a page from Mulally’s brilliance and apply it accordingly.

Leaving Boeing was never something Mulally considered. However, like a fish taking bait, he would later share that the lure from Boeing to Ford was the opportunity to help yet another manufacturing icon succeed. Mulally believed that Boeing’s success was largely due to the management philosophy he developed at the MIT Sloan School of Management years ago called Working Together. He believed the same could be replicated at Ford. Although Boeing was a completely different type of manufacturing, both required parts for a vehicle: cars had thousands that kept them on the road, while airplanes had millions of them that kept them in the air.

Soon after Mulally decided to take on the roles of president and CEO, he began devising a plan to rebuild the automaker. Mulally’s initial environmental scan revealed that Ford’s hierarchical organizational structure and reporting system were too rigid. There were too many reporting layers between the divisional/departmental leaders and the CEO himself, which prevented critical information from reaching the top tier. Such a structure and reporting system, popularized for compliance and management, hindered both transparency and accountability: two essential building blocks for success.

Riddled with too many global regions, brands, and a culture characterized by infighting, Ford indirectly created silos. The structure appeared more like fiefdoms, with leaders who chose not to collaborate or share valuable information when issues arose, and no one admitted to having a problem either. Mulally’s matrix would be different. For the first time in Ford’s history, both senior and divisional leaders were asked

to work together to help solve their divisional problems and assist their colleagues with theirs.

By reorganizing Ford’s various global regions into three business units, with Ford Credit as the fourth, Mulally streamlined Ford on a global scale. He said, “To construct your leadership team, you need to include the head of every business unit [vice-presidents] … and each function [divisional leaders] … this is how you’ll align the entire organization and ensure everyone is executing one plan.” Mulally devised a structure that increased the number of people reporting to the top executive, providing exceptional transparency and accountability, as well as the much-needed recruitment of help to tackle Ford’s issues and problems.

According to Hoffman, “…[Mulally’s] system made each business unit fully accountable but also made sure that each key function of the organization was managed … to maximize efficiencies and economies of scale.” To ensure continuity and succession planning, Mulally informally identified three to four individuals for each business unit as well as in the functional areas. Should one of the VPs or divisional leaders become ill, take stress leaves, or leave Ford entirely, these individuals would help keep Ford on plan.

Similar to how Mulally came to Ford from Boeing, fire service leaders can also be drawn to or recruited to assist struggling fire departments. Unlike the private sector, which focuses on shareholder value, the public sector has its own unique shareholders: taxpayers.

Most fire departments continually face a wide variety of challenges: tight budgets, high turnover rates, mental and behavioural health concerns, poor morale, and even

This year, we’re bringing you an event that’s bigger, better, and packed with more value than ever before. With two full days of immersive content, increased networking opportunities, and more ways to engage with industry stakeholders, this is the ultimate platform for showcasing your brand as a leader in wildfire suppression. It’s time to elevate your presence — this is the must-attend event of the year, designed with your success in mind.

The Canadian Wildfire Conference is an educational program designed to unite air and ground personnel alongside its trade show component. The conference agenda includes a range of presentations from industry leaders to provide critical information on the challenges and opportunities of effective wildfire suppression.

Secure your exhibitor and/or sponsor spot today – spaces are limited.

leadership team members reluctant to collaborate due to interpersonal competition and conflicts, or ulterior motives such as advancing their own brand. Choosing to restructure a fire service’s organizational chart is not an easy feat and certainly one that might not appeal to many fire administrators. Yet, when considering the possible benefits, it is worth exploring.

If the fire department is struggling to increase transparency, accountability, and trust, this is where the fire service can consider Mulally’s matrix concept. The business units and functional areas involved in automobile manufacturing and the fire service are obviously quite different, but there is potential for restructuring that could yield similar success as that achieved by Mulally at Ford.

According to the late Dr. Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi, “the most often mentioned trait of a healthy organization is communication based on trust. Unless subordinates can trust their leader’s commitment to the firm’s [organization’s] vision and values, and unless the leader can trust his subordinates to be candid, the organization will soon self-destruct.”

Too often, the rigid traditional hierarchy creates barriers and promotes competition among an organization’s components. The key concept of the matrix is to encourage collaboration to solve issues across different functional areas. Individual managers remain responsible for getting things done within their assigned areas, but the management team collaborates to develop strategies and resolve problems. This approach allows for diverse thinking regarding issues that may arise beyond someone’s scope of responsibility.

Let us begin with the functional areas. In the fire service, these may include suppression, logistics, fire prevention and public education, training and professional development, communications, occupational health and safety, organizational well-being, administration, finance, human resources and labour relations. Typically, chief officers or administrators oversee each component listed above, along with those assigned to rotating shift work in operations; it is not much of a stretch to view them as part of a matrix.

The business units would be somewhat more unconventional compared to traditional methods. Choosing, for example, to assign VPs of a fire department, aka deputy fire chiefs, to

oversee specific platoons or districts, rather than the typical operations and administration portfolios, may seem unorthodox. However, as demonstrated by Mulally, this approach enables the heads of functional areas and division leaders to collaborate effectively with the business units to share valuable information. Essentially, it creates a universal problem-solving platform that prevents silos, enhances communication and, most importantly, fosters team trust.

Interestingly, the fire service has attempted something similar. The late Fire Chief Alan Brunacini organized the Phoenix Fire Department (PFD) in a comparable way during the 1980s. I was eager to learn more from his former assistant, J. Gordon Routley, who recently retired from the Service de Sécurité Incendie Montréal (SIM) as an assistant chief.

“The organization structure of the PFD was significantly wider and flatter than most comparable fire departments at that time. The levels of hierarchy were limited, so the distance from the top of the organization to the level where ‘the rubber meets the road’ was not too far. This increased the number of participants around the management table, where there was a lot of discussion of issues and sharing of ideas. One of the fundamental beliefs was that we all succeed together, or we all fail together, so mutual support and cooperation were valued. Everyone was regularly updated on what each other was doing within their areas of responsibility, so the tendency to create ‘silos’ was resisted.

We were very successful within an organization of that size, but I would attribute most of the success to Bruno’s [Brunacini] leadership and vision, along with the calibre of the management team. We had a very capable group of individuals working together at the upper management level, with exceptional interpersonal dynamics and group cohesiveness. We certainly didn’t function like most other fire departments of that era,” said Routley.

What is interesting is that Routley’s comment on “working together” echoes Mulally’s management philosophy. Like Mulally, many of Brunacini’s “management methods were unorthodox [in terms of traditional ways of doing business], but they were effective as a result of his unique combination of intuition and innovation.”

Routley stated that, “the PFD functioned effectively as a management team of eight to

10. The Ford-Mulally model was much larger in scale and involved huge business units.” Even though this is true about Ford, if a similar matrix could be used as a model, scaling down to either using platoons or municipal districts, perhaps there is a silver lining in this big cloud. Utilizing Mulally’s decision to informally uncover three to four deep for the business units and functional areas provides the necessary depth for continuity and succession planning, which the fire service needs to ensure service excellence.

Hierarchical organizational structures usually work well during emergency incidents; however, it is during non-emergency times that strategies are planned, goals are identified and creativity and innovation are needed to solve problems. Choosing to adopt a different organizational structure might upset traditions, but it makes sense to do so proactively and progressively.

Mulally achieved global success and returned two manufacturing companies to profitability; why can’t the fire service do the same, especially if they are struggling too? Creating a structure that encourages leaders to collaborate and support each other optimizes resource utilization. If the PFD, led by Chief Brunacini and his fire leadership team, operated with overarching success so many years ago, employing a unique matrix somewhat similar to Mulally’s organizational structure, perhaps the fire service of today could take a page from manufacturing and the PFD to help make the fire service exceptional.

• Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi. 2003. Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the making of Meaning. Penguin Group.

• Gist, Marilyn. 2020. The Extraordinary Power of Leader Humility: Thriving Organizations – Great Results. Accessed at https://www. workingtogetherbrightfuture.com/working-together-library-1/wt-12.

• Hoffman, Byrce. 2012. American Icon: Alan Mulally and the Fight to Save Ford Motor Company. Crown Business (Crown Publishing Group).

• Mulally, Alan and Witty, Adam. 2019. Relentless Implementation: Creating Clarity, Alignment, and a Working Together Operating System to maximize Your Business Performance. Forbes Books.

CANADIAN SAFETY EQUIPMENT IS PROUD TO BE A DISTRIBUTOR FOR THE INTERSPIRO RESPIRATORY PROTECTION LINE. STATE OF S9

INCURVE IS ONE OF THE MOST COMFORTABLE SCBAs YOU WILL EVER WEAR.

GIVE US A CALL AT 0182 OR EMAIL US AT INFO@CDNSAFETY.

No company has a richer history in respiratory protection than Interspiro. Their innovations have become industry standards, time and

•Heavy Duty Air Berms – FSI utilizes extremely heavy duty air berm construction in all DAT® series mass casualty portable hazmat decon shower systems FSI uses the same 1100Dtex, quadruple overlapped and glued berms found in our wide range of transom rescue boats –known for the extreme conditions they are subjected to

•Extremely Rapid Deployment – FSI Portable Shower Systems are compact, fully integrated, and supplied complete in a heavy duty carry sleeve/bag FSI Shower systems inflate virtually unaided – with the use of compressed air, or via a supplied electric inflator/deflator with a hands-free connector within minutes (size of unit and method of inflation dependent) The inflatable decontamination shower units are meant to be deployed simply and quickly – with modest training and few personnel

The Solo SCBA Decon/Washing machine was designed and built for one purpose only…to protect Fire Fighters from Cancer causing agents found in the Smoke and residue left on their SCBAs. As an added bonus it can clean Gloves, Boots and Helmets. In addition, it substantially lowers the

ü REDUCED HEALTH RISK

ü SAVES TIME 2/PKS IN 8 MIN ü EASY TO USE

Qualified by MSA, SCOTT, DRAEGER & INTERSPIRO for cleaning their SCBAs.

5 GALLON COLLAPSIBLE TANK PADDED HARNESS DUAL TOP HANDLES

By Joel Johnson

The month of May marked two significant 9th anniversaries. The first was for the devastating wildfires that tore through Fort McMurray, Alta., where, over the course of two months, more than 88,000 people were forced to evacuate their homes, and over 2,400 homes and businesses were destroyed. Known as “The Beast”, this wildfire became Canada’s most costly natural disaster, burning nearly 1.5 million acres of land in Alberta and crossing into Saskatchewan.

The impact of this disaster is still felt by many in the Fort McMurray region. The wildfires left behind not just physical damage, but also psychological scars. High incidents of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression have been reported years after the event. For some, the memory of the fire lingers in subtle ways: the smell of a campfire, for example, remains a trigger for some who lived through the disaster. Years later, those triggers can transport people back to that time of fear, displacement, and uncertainty. This underscores how deeply wildfires affect not just the landscape, but the very essence of a community and those in it.

But from this devastating event came something powerful: the birth of Team Rubicon Canada, a veteran-led humanitarian organization. Volunteers, or Greyshirts, from Canada, the U.S., the UK, and Australia came together to provide crucial support to the community. Team Rubicon’s 80 volunteers helped train over 300 locals and assisted 900 homeowners in recovering personal belongings from their destroyed properties. Since then, Team Rubicon Canada has become a trusted organization, providing support before, during, and after disasters.

On this anniversary, Team Rubicon Canada again mobilized to support Fort McMurray communities at risk of wildfires. Through Operation Slow Burn, teams of Greyshirts worked in Wood Buffalo and the East Prairie Métis Settlement (EPMS) providing critical fire mitigation services. This collaborative effort, in partnership with FireSmart Alberta and with financial

support from the Canadian Red Cross, is vital as these communities continue to face the threat of wildfires.

The focus of this effort was to reduce wildfire risks by removing danger trees, managing vegetative fuel loads, and clearing debris from at-risk areas. These mitigation strategies are essential in preparing communities for future wildfire seasons and reducing the destructive potential of wildfires.

“We’re no longer a community impacted by wildfire, we’re a community that lives with wildfire,” emphasized Chris Pottie, program manager at FireSmart Wood Buffalo. “Thinning the forest reduces the intensity of potential wildfires. As someone who lost their home to wildfire in 2016, I understand the importance of projects like these to make the community safer.”

Over five weeks, more than 80 Greyshirts from across Canada worked alongside FireSmart Alberta to implement these fire mitigation strategies. “The build-up of combustible materials in the forest increases hazards over time,” added Pottie. “Clearing these materials before a wildfire strikes makes it more manageable, and safer for firefighting personnel to control.”

This work was physically demanding and required careful planning and coordination. However, these efforts are critical in building resilience and ensuring that communities vulnerable to wildfires are prepared for the future.

The wildfire mitigation projects in Alberta’s communities of Wood Buffalo and East Prairie Métis Settlement exemplify how volunteerism is at the heart of Team

Certificate in Fire Service Leadership

NAME POSITION DEPARTMENT

Adam Charles Walker Acting Lieutenant Saint John Fire Department

Braden Gartner Fire Service Instructor Saskatoon Fire Department

Bradley Butler Director of Protective Services / Fire Chief Town of Happy ValleyGoose Bay Fire Rescue

Clark James Whelpton Fighter/Paramedic Brandon Fire and Emergency Services

Cody Asselstine Captain Kitscoty Fire

Dakota Murray Deputy Fire Marshal PEI Fire Marshal’s Office

Dallas R. D’Aoust Deputy Chief Yorkton Fire Protective Services

Dustin W. Drew Lieutenant Halifax Stanfield International Airport Fire Department

Eric Sohi Fire Prevention Officer Saint John Fire Department

Eric Walker Deputy Fire Chief Mayne Island Fire Rescue

Gage Wood Firefighter Paramedic Brandon Fire and Emergency Services

Jason Knack Training Officer Innisfil Fire & Rescue

Jeremy Harley Qualified Lieutenant Saint John Fire Department

Matthew Hill Firefighter St. John’s Regional Fire Department

Ryan Ferris Qualified Lieutenant Saint John Fire Department

Tyler Robbins Firefighter/Paramedic Brandon Fire and Emergency Services

Adam Read Deputy Chief Grand Bay-Westfield Fire-Rescue

Bradley Barth Captain Brampton Fire and Emergency Services

Jody Woodford Chief Tulameen & District Fire Department

Mathieu Jean Dorval Lieutenant Moncton Fire Department

Certificate in Fire Service Administration

André R. W. Lavoie Firefighter Engineer Halifax Regional Fire and Emergency Services

Advanced Certificate in Fire Service Administration

Jody Woodford Chief Tulameen & District Fire Department

Certificate in General Fire Service Administration

NAME POSITION DEPARTMENT

Amy Diane West Assistant Fire Chief –Training Town of Taber Fire Department

Richard Hynes Firefighter/Captain St. John’s Regional Fire Dept/Conception Bay South Fire Dept

Certificate in Advanced Fire Service Administration

Cale McLean Fire Prevention Officer/Captain/Fire Investigator Midland Fire Department

Certificate in Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Accessibility in the Fire Service

Allan McLeod Platoon Chief Saint John Fire Department

Diploma in General Fire Leadership

Cale McLean Fire Prevention Officer/Captain/Fire Investigator Midland Fire Department

Mathieu Jean Dorval Lieutenant Moncton Fire Department

Diploma in Executive Fire Leadership

Constant Rosa C.D. Fire Chief Saint-Vallier Fire Department

Joshua Hennessy Platoon Chief Saint John Fire Department

Mathieu Jean Dorval Lieutenant Moncton Fire Department

Scott Tuton Assistant Deputy Chief Red Deer County Protective Services

Fire Officer IV

Scott Tuton Assistant Deputy Chief Red Deer County Protective Services

Fire Officer III

Constant Rosa C.D. (Graduate 2023-24) Fire Chief Saint-Vallier Fire Department

Scott Tuton Assistant Deputy Chief Red Deer County Protective Services

Fire Officer IV

Constant Rosa C.D. (Graduate 2023-24) Fire Chief Saint-Vallier Fire Department

Joshua Hennessy (Graduate in 2022-23) Platoon Chief Saint John Fire Department

Mathieu Jean Dorval (Graduate 2023-24)

Moncton Fire Department

Rubicon Canada’s mission first culture. These Greyshirts, many of whom are veterans and first responders, not only brought specialized skills but also a deep commitment to serving others. Their role goes far beyond simply clearing trees or debris, it ensures that communities prepare, recover, and are more resilient. By stepping in before disaster strikes, these volunteers take proactive steps to reduce future risks, ensuring that wildfires’ impact doesn’t last indefinitely.

The scale of the work involved in Operation Slow Burn was complex, both logistically and operationally, especially considering the challenges Team Rubicon Canada faces in coordinating such large-scale projects while remaining responsive to other emergencies across the country. Team Rubicon Canada’s ability to adapt and tackle multiple operations at once, with military precision, expert skills, and a team of volunteers

Slow Burn was in support of the preventing wildfires and supporting communities in Fort McMurray.

who have a passion for serving people and improving community resilience, is what makes it unique.

Kenney, chief operating officer, Team Rubicon Canada. “Coordinating this fire mitigation project while maintaining our ability to respond to other disasters across the country highlights the depth of our capabilities, and commitment of our volunteers. This project is a true collaboration, requiring skill, experience, trust, and adaptability to meet the challenges of wildfire risk reduction.”

The work being done through Operation Slow Burn is just one example of the incredible impact that Team Rubicon Canada has on communities before, during, and after a disaster. But the work is far from over. As disasters and the risk of wildfires continue to grow in severity, as seen so far this summer, the need for trained volunteers has never been greater.

25_007023_Firefighting_In_Canada_SEP_CN Mod: June 16, 2025 3:38 PM Print: 07/23/25 9:56:48 AM page 1 v7

“Operation Slow Burn is crucial to reducing wildfire risks in these communities and others like it. But it’s also a testament to the complexity and scale of Team Rubicon Canada’s work, and the relationships we benefit from with organizations such as FireSmart Alberta and the Canadian Red Cross,” explained Tim

Are you ready to make a difference? Step into the arena and become a Greyshirt and share your skills and passion to help communities in need.