by Brett Ruffell

by Brett Ruffell

You’ll notice this issue has an international feel to it.

While Canada is a global poultry leader, we thought it’d be interesting to look abroad for ideas and innovations.

In our cover story (pg. 12), for example, producer and veterinarian Lloyd Weber makes the case for adopting the deep litter approach many U.S. producers employ.

But while global markets present opportunities to learn new ways to enhance your farming business, they also present challenges. Indeed, especially when trade agreements are being negotiated.

A nd as countries vie for greater access to Canada’s egg and poultry markets, it inevitably brings out the usual supply management critics – a handful of politicians and media figures who have a prominent platform to get their message out but who often have their facts wrong.

The events around the most recent trade talks underscore the need for more individual producers to stand up for the system and its benefits. That was the message speaker Andrew Campbell delivered at the Western Poultry Conference, which was recently held in Red Deer, Alta.

“If we want public as well as continued government support for the system, we as an entire industry have to be part of the solution in making sure that

message gets out,” says Campbell, who presented “Become a Supply Management Champion” at the event.

The Strathroy, Ont., native has a unique combination of skills. Raised a dairy farmer, he studied journalism and covered agriculture news for a while.

When he eventually returned to the farm, he continued to use his communications skills. He began advocating not just for the dairy industry but for agriculture as a whole through writing and speaking engagements.

Campbell notes that, especially as supply-managed in-

“We’ve got a whole bunch of people helping us reach our goals that we’re, in turn, supporting through our business”

dustries, dairy and poultry farming share many of the same principles. He speaks to both audiences regularly, and has been delivering his message about championing the system to poultry and egg groups from coast to coast in recent months.

Campbell acknowledges that marketing boards do a great job of communicating why supply management is important for their industries, rural communities and consumers.

That said, he feels too many farmers rely on advertising campaigns and newspaper op-

eds to get the job done on their behalf. While he knows firsthand how busy producers are, he believes each one has a responsibility to help sup port supply management.

H ow? For one, he says farmers can reach a broad audience through social media if they use it effectively. As examples of strong advo cacy on Twitter, he recom mends following dairy farm ers Bruce Sargent (@ FarmBoyProd) and Tim May (@MayMayhaven).

But to Campbell, producers can have the biggest impact simply by talking to people in their community about supply management, whether it’s at the golf course, place of wor ship or a family dinner. “Those one-on-one conversations can be really impactful,” he says.

To win over the public, critics often paint supply-man aged industries as small ‘car tels’ making a fortune off the backs of Canadians. To counter this tactic, Campbell says pro ducers should emphasize the impact their industr the local economy.

“We’ve got a whole bunch of people helping us reach our goals that we’re, in turn, sup porting through our business,” he says. “And without supply management how successful are some of those?”

Citing Alberta as an ex ample, he says there are only about 1,000 poultry and dairy farmers in the province. However, research shows supply m anagement creates thousands of jobs. “We as farmers need to know where to get that information so we can have it in our back pocket.”

canadianpoultrymag.com

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

National Account Manager Catherine Connolly cconnolly@annexbusinessmedia.com 888-599-2228 ext 231

approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

With more than 70 years of experience and more than 3 billion birds around the world drinking from a Lubing system on a daily basis, Lubing has established a rock solid position as a global leader developing innovative products that work!

No matter if you are looking for a drinking system for Turkeys, Broilers or Breeders or if you need an Egg Conveyor system to move eggs, we know your system will definitely perform better with LUBING!

Contact a local LUBING representative for information on our latest products.

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263.6222

Fax: (450) 263.9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963.4795

Fax: (780) 963.5034

The 2019 International Production & Processing Expo (IPPE) had a terrific year with 32,931 poultry, meat and animal food industry leaders from all over the world in attendance, setting a new record. There were also 1,426 exhibitors with 600,732 sq. ft. of exhibit space, two more records. The Expo is the world’s largest annual feed, meat and poultry industry event of its kind and is one of the 30 largest trade shows in the U.S. IPPE is sponsored by the U.S. Poultry & Egg Association, American Feed Industry Association and North American Meat Institute.

Merck Animal Health has reached an agreement with Rapid Genomics that grants the company exclusive rights to Rapid Genomics’ vaccination verification tool, Viral Flex-Seq. This tool will be utilized in combination with Merck Animal Health’s Innovax range of vaccines, including Innovax-ND-IBD, which provides long-term protection against three infectious poultry diseases, Newcastle disease, infectious bursal disease and Marek’s disease, in a single dose.

As a celebration of exceptional performance and dedication to poultry breeding, Cobb-Vantress recently presented its annual Flock Awards to North American poultry customers who demonstrated remarkable results in 2018. Launched in 2004, the awards program recognizes top-performing facilities in the United States, Canada, Mexico and Central America that are maximizing the genetic potential of Cobb breeding stock.

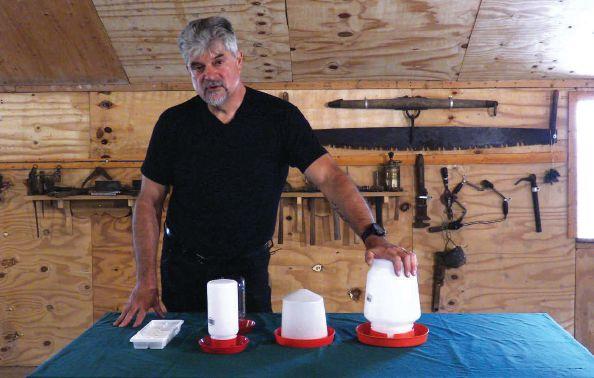

Long-time poultry veterinarian Scott Gillingham focuses each module on a different aspect of what he calls the poultry “law of FLAWS”: food, light, air, water and security.

Small poultry flocks are growing in popularity in Ontario. Many small flock owners have launched into raising their own meat and eggs without any previous farming skills or husbandry knowledge in how to best look after the birds in their care.

The Poultry Industry Council is leading the initiative to educate small poultry flock owners, with funding from the Ontario Independent Meat Processors.

With funding from the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (the Partnership), the Poultry Industry Council is supporting the development of an online poultry video and podcast training program in animal welfare basics, production efficiencies and minimizing poultry health risks that students will be able to complete at their own pace.

The goal is to showcase best management practices for biosecurity, production, human health and animal welfare and demonstrate that they’re the same regardless of the size of a flock.

Long-time poultry veterinarian Scott Gillingham is featured

prominently in the series of videos and podcasts. Using his years of expertise as a poultry veterinary specialist and his own experience with poultry, he focuses each module on a different aspect of what he calls the poultry “law of FLAWS”: food, light, air, water and security.

“Small flocks are a fast-growing hobby and people are hungry for premium information that is credible – the videos and podcasts filmed in local barns, coops and yards let Gillingham be a virtual coach to anyone with a small poultry flock right in the comfort of their own homes,” says Ontario agriculture minister Ernie Hardeman.

The Poultry Industry Council is leading the initiative, with Ontario Independent Meat Processors supporting the funding application. The free podcasts are available on iTunes; the videos will soon be available on ichicken.ca.

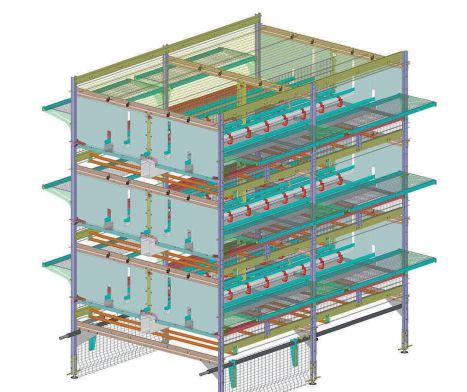

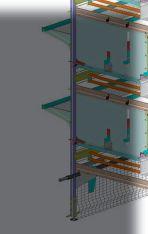

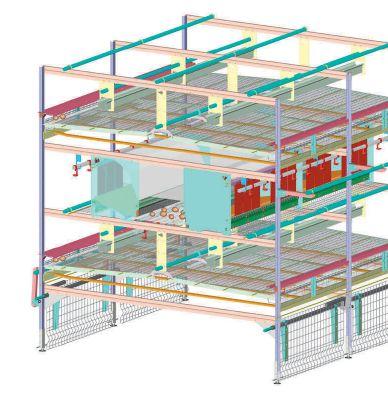

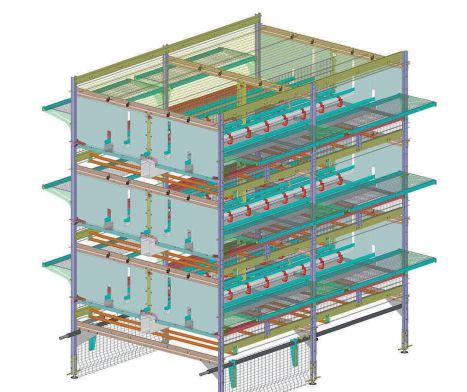

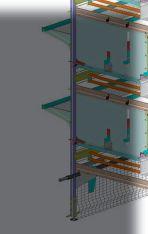

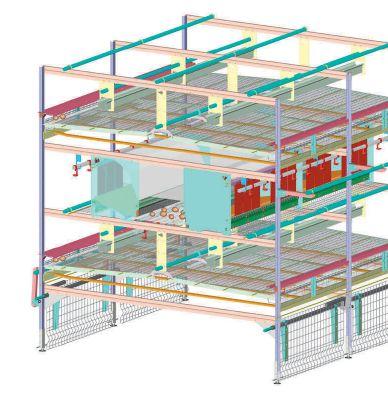

At November’s EuroTier trade fair in Hanover, German, Big Dutchman CEO Bernd Meerpohl spoke about the future of poultry houses. A Canadian Poultry correspondent interviewed him at the event about that topic, as well as about challenges and opportunities facing the industry and his thoughts on the perfect poultry barn.

How do you see the poultry barn of the future?

There’s no doubt that the entire world is going to look at more animal welfare questions and it will also look at more sustainability. These are words that are often overused, but there is no doubt that it will move towards that.

This will, of course, also mean we need to look more at sensor technology to better understand where the problem points in the poultry barn are. That’s true for broilers as well as for layers.

We need to better understand what’s happening in the barn so we can adapt better than we are already. I think we are already pretty good, but there’s still a ways to go.

How about in terms of sustainability?

Yes, what I also see in the poultry barn of the future is that we will need to look at sustainability and economic points, as we have to feed maybe nine to 10 billion people in the future. We can’t gain on the one hand through animal welfare and environmental improvements, and lose on effectiveness. And that’s exactly why I believe we will need more measuring and more sensors.

Are there specific technologies that you think will be disruptors?

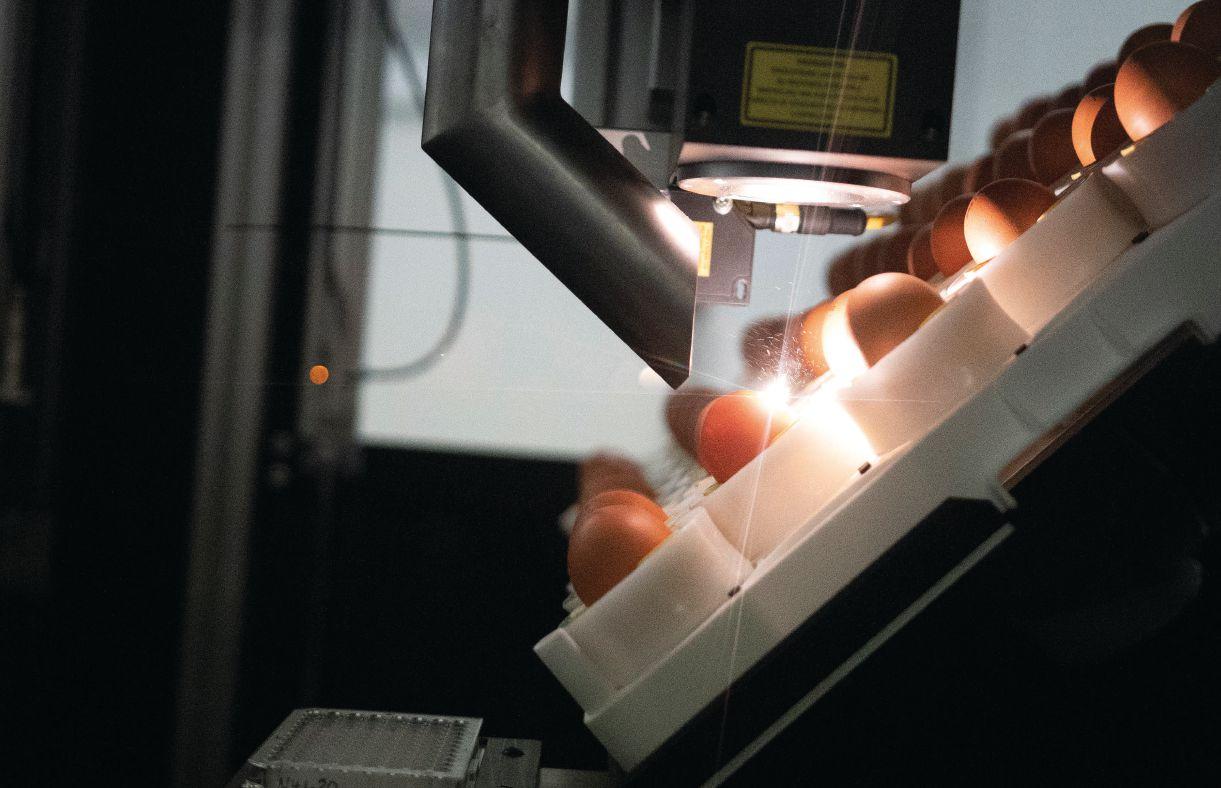

I think there are a few robotic solutions that could certainly be game changers. One thing that is already here today – not in the finally stages, but in the beginnings – is the in-egg chicken sexing. I think that is a game changer if we can use it. It’s being done, but the question is, it good enough yet? None of them are yet where they should be, but I tip my hat at what they are doing, for sure.

Which regulations present a challenge for poultry producers? What I’m a bit afraid of, to be honest, is that very small minorities are influencing politics, particularly in building permits. We have already seen this in Germany. It is already close to a point where we can’t do anything anymore. On the one hand, people are saying we need more animal welfare. And if I say, ‘Okay, I need a hole in the wall to let the chickens out,’ then I need completely new permits. That’s really a difficult subject.

What does the perfect poultry barn look like?

It would not be a free-range barn – for the purposes of influenza and so on. It would be an in-house barn, and it would be an aviary system – a real aviary system. It would be, depending on the location, solar powered. It would be pretty transparent with a lot of glass, and it would try to turn manure into electricity as well, so essentially a closed system regarding electricity and waste control. That’s what I would dream of.

Bernd Meerpohl is CEO of Big Dutchman and chairman of the EuroTier Expert Advisory Board.

MARCH

MAR. 23

PIC Raising Backyard Chickens, Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

APRIL

APRIL 3-5

Conference on Poultry Intestinal Health Italy ihsig.com

APR. 3-4

Canadian Poultry Expo, London, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

MAY

MAY 1

PIC Research Day Stratford, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

MAY 14

Western Meeting of Poultry Clinicians and Pathologists Abbotsford, B.C. westvet.com

MAY 15

B.C. Poultry Symposium Abbotsford, B.C. bcpoultrysymposium.com

MAY 29

Human Resource Day Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

JUNE 9-11

CPEPC AGM and Convention Victoria, B.C. cpepc.ca

JUNE 25

PIC Health Day Stratford, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

A group of Toronto scientists will soon attempt to develop a less-expensive way to grow lab-made meat after securing a grant from an American non-profit aiming to boost advances in cultured protein.

Cellular agriculture has been touted as the future of food thanks to its smaller environmental footprint and consideration for animal welfare, but until recently much of the research has been done south of the border.

Cultured food uses cell cultures to grow animal products like beef, eggs or milk in a laboratory without the need for livestock. Some companies have already made these kinds of products, but it’s an expensive undertaking and no such items are readily available on store shelves yet.

“This is our, my first foray into this kind of research,” said Peter Stogios, a senior research associate at the University of Toronto and lead researcher on the winning project.

He’s trying to overcome what he sees as one of the biggest hurdles for the whole industry of cultured meat – an expensive component to what he likens to a broth needed to grow meat in a lab.

The broth is composed of vitamins, minerals, amino acids and growth factors that are essential to sustain tissue culture. Those growth factors are very expensive, he said.

“Can we create those protein molecules, those growth factors better, cheaper and actually make them more potent?” he said.

The four-person team will

cast a wide net to look at growth factors from other species, like birds and fish, and attempt to mix those with cow cells. They hope to start the initial phase immediately and wrap it up within six months.

If they discover an exotic growth factor or multiple that works really well, he said, the team will enter into an engineering phase where it will try to make them more potent. The second phase could take a year and a half.

The Good Food Institute in Washington, D.C., awarded the team $250,000 USD over two years to pursue the project in an announcement made earlier this month. It’s one of 14 projects to receive the inaugural grant for plant-based and cell-based meat research and development, and the only cell-based project winner from Canada.

The GFI was particularly excited with Stogios’s proposal because it addresses the industry’s cost issue and isn’t just looking at lab-grown beef, but also possibilities for other proteins, like chicken, said Erin Rees Clayton, the scientific foundations liaison.

Whatever advances Stogios and his team make will be published and widely available, hopefully eliminating repetitive research and development at cell-based meat companies, she said.

“If Peter is able to create these, they’ll be relevant to many different companies and they won’t have to spend the time and resources to create those growth factors,” she said.

University of Toronto scientist Peter Stogios is the lead researcher on a cultured protein project that secured a $250,000 USD grant from The Good Food Institute in Washington, D.C.

The latest advances with an innovative new system for maximizing livestock feeding results were unveiled by Canadian Bio-Systems Inc. (CBS Inc.) at the International Production & Processing Expo in Atlanta. “What’s your FSP fingerprint?” is a new approach to advanced precision livestock feeding that helps individual operations identify how they can best integrate and capture synergies among different types of feed science technology platforms. An early beta version of this robust science- and data-driven system was introduced last year coinciding with the launch of new CBS Inc. Feed Science Platforms (FSP). The full official launch of What’s your FSP fingerprint? at IPPE 2019 featured the inclusion of further enhanced diagnostic technology and the introduction of a simple-to-use web-based application.

The federal government is investing up to $4.56 million in industry-led animal welfare initiatives, including efforts to make the transport of poultry and other livestock safer and more humane. It granted the funds to the Canadian Animal Health Coalition, on behalf of the National Farm Animal Care Council, to help update and develop codes of practice. Part of the investment will be used to update the transportation codes of practice for the care and handling of farm animals during transport.

Cobb-Vantress released new management guides and product supplements as part of the company’s enhancements to its Cobb Academy program. These resources were updated to reflect top-performing flocks, and provide best practices and recommendations to help maximize genetic potential. For more information, visit: canadianpoultrymag.com.

By Tom Inglis

Tom Inglis is managing partner and founder of Poultry Health Services, which provides diagnostic and flock health consulting for producers and allied industry. Please send questions for the Ask the Vet column to poultry@annexweb.com.

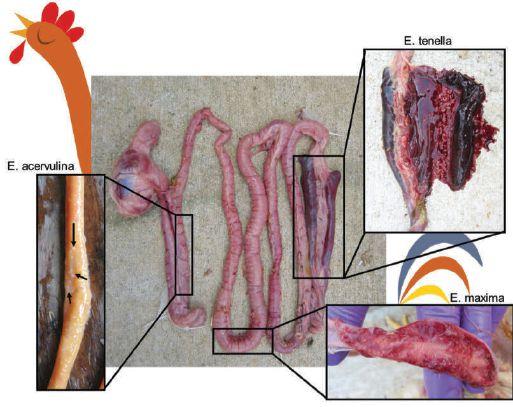

I’ve heard of the term coccidiosis before and know that medications are often added to the feed to prevent it. But what exactly is it and why is it important to watch for signs of it?

Coccidiosis refers to a parasitic infection of the gut that causes clinical signs of disease. The parasites referred to are coccidial species ( Eimeria ). Some key clinical signs include reduced feed consumption, increased water consumption, ruffled feathers, watery feces, dehydration, reduced weight gain, increased feed conversion, bloody dropping and mortality.

The latter two signs indicated are often associated with clinical coccidiosis, where signs of this disease are obvious. These signs, however, ar e less common than the other clinical signs listed, which often go unnoticed in a flock but can have negative effects on performance.

This group of less obvious signs may be better described by the term subclinical coccidiosis – which is far more common today because feed medications are used to prevent clinical coccidiosis.

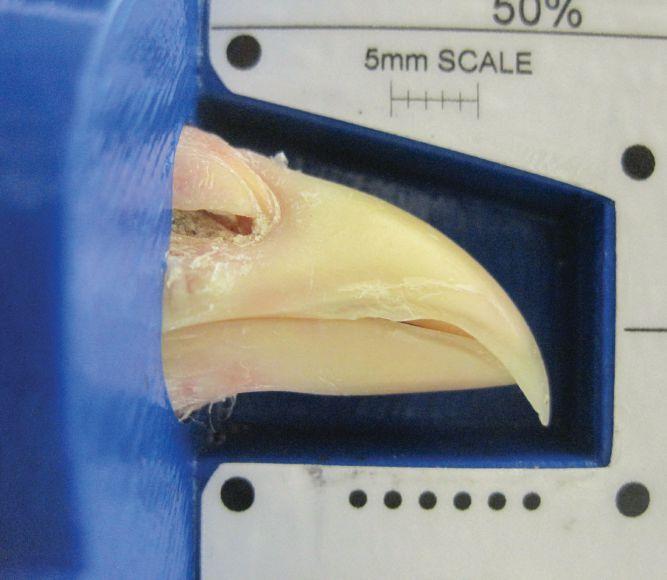

Coccidial species

The parasitic species that cause coccidiosis (coccidia) belong to the genus Eimeria There are many different species that can infect different types of poultry.

In broilers (see figure 1)

Species of primary importance:

• Eimeria acer vuline – infect upper intestinal tract

• E. maxima – infect middle intestinal tract

• E. tenella – infect ceca (lower intestinal tract)

In broiler breeders

Species of primary importance:

• E. acervulina – infect upper intestinal tract

• E. maxima – infect middle intestinal tract

• E. tenella – infect ceca

• E. necatrix – infect middle intestinal tract and ceca

In turkeys

Species of primary importance:

• E. adenoides – infect ceca and lower intestine

• E. meleagrimitis – infect midgut

• E. gallopavonis– infect lower intestine +/- ceca

• E. dispersa – infect upper, middle and lower intestine

Coccidial lifecycle

Poultry species ingest coccid-

ial organisms and, upon infection of the gut, they replicate. Once a cycle of replication is complete, new oocysts are passed in the fecal matter from an infected bird.

Oocysts that are passed in fecal matter are initially non-infective. Once environmental conditions are appropriate (requires the right amount of oxygen, heat and moisture), the oocysts can become infective and once consumed by the corresponding species of poultry, the cycle repeats.

The non-infective form of coccidial organism is extremely resistant to destruction, Thus, we will continue to deal with coccidial infection in poultry species. You will never completely get rid of all of these parasites, no matter how hard you try.

When does coccidial infection become subclinical or clinical coccidiosis?

The answer to this question is tricky and depends upon two main factors, the number of infective eggs present and the frequency of consumption of infective eggs. All poultry at some point in production will be exposed to coccidial species, but not all poultry will develop clinical or subclinical coccidiosis. Some low-grade cycling of coccidial parasites in a flock is even considered normal or unavoidable depending on what preventative or control programs are implemented. Some of the factors which impact the number of infective eggs present in a poultry environment include: temperature; oxygen; moisture; barn clean out; bird density; litter quality; feed availability; coccidial control programs; and other disease challenges

Making a diagnosis of clinical coccidiosis (bloody droppings and/or mortality) is far easier than making a diagnosis of subclinical coccidiosis, primarily because the symptoms of a clinical infection are far more visible. A diagnosis of subclinical coccidiosis requires examination of ‘normal’ birds from a given flock.

To further complicate matters, many of the coccidial species that parasitize birds cannot be observed with the naked eye and microscopic

examination is used for detection of these species. Knowing the factors listed above is also important in the interpretation of findings, understanding why a flock is affected with clinical or subclinical coccidiosis and in preventing the same problem in subsequent flocks.

In consultation with your veterinarian, normal birds from a broiler chicken flock can be submitted for coccidosis scoring based on the system devised by Johnson and Reid. Higher coccidiosis scoring lesions indicate more damage to the gut. The cost of a higher coccidiosis lesion score on growth has been calculated through highly detailed experiments.

Control of clinical or subclinical coccidial infection is an integrated process. It relies on the use of anticoccidial medications, vaccination, management and flock environment. Anticoccidial medications are often divided into two categories: Ionophores and synthetic (or ‘chemical’) products.

Vaccination is an alternate method of control, which relies on controlled exposure to coccidial parasites to stimulate a protective immune response. Coccidial vaccination also serves to re-populate the environment with coccidial strains, which are less tolerant to the anticoccidial medications often employed.

Along with the use of these different products, management of the flock and flock environment can play an important role in the success of the ov erall program. Certainly limiting temperature and oxygen would be a means of also limiting coccidial cy cling,

however this is not possible in the presence of live birds.

Controlling moisture level however is one example of a key area that can have a huge impact on the success or failure of a given coccidial control program. Too much moisture can encourage excessive coccidial cycling, even in the face of medications! Too much or not enough moisture can also negatively impact cycling of vaccine strains of coccidial organisms.

How is coccidiosis treated and what do I do if I think my flock has coccidiosis?

The products used for the treatment of coccidiosis are different from those used to control coccidial cycling. Treatments are implemented in response to clinical coccidiosis, or when subclinical coccidiosis is detected and having an impact on the flock. There are several treatment options available for coccidial infection and they include products such as amprolium (Amprol), Sulfa medications (such as Sulfaquinoxaline) or potentiated sulfa medications (Quinnoxine S).

Depending on the type of infection a flock is experiencing, one of these medications may be a better option that the others as each has optimal effect in specific locations of the gut. For example, coccidiosis due to Eimeria tenella, which results in bloody fecal droppings, is best treated with Amprol, which has a greater effect against this parasite in the ceca, compared to other coccidial species in other regions of the gut.

If you suspect your flock may be affected with coccidiosis, it is wise to consult with a veterinarian. It’s important to properly diagnos and monitor the coccidiosis as well as identify the species responsible.

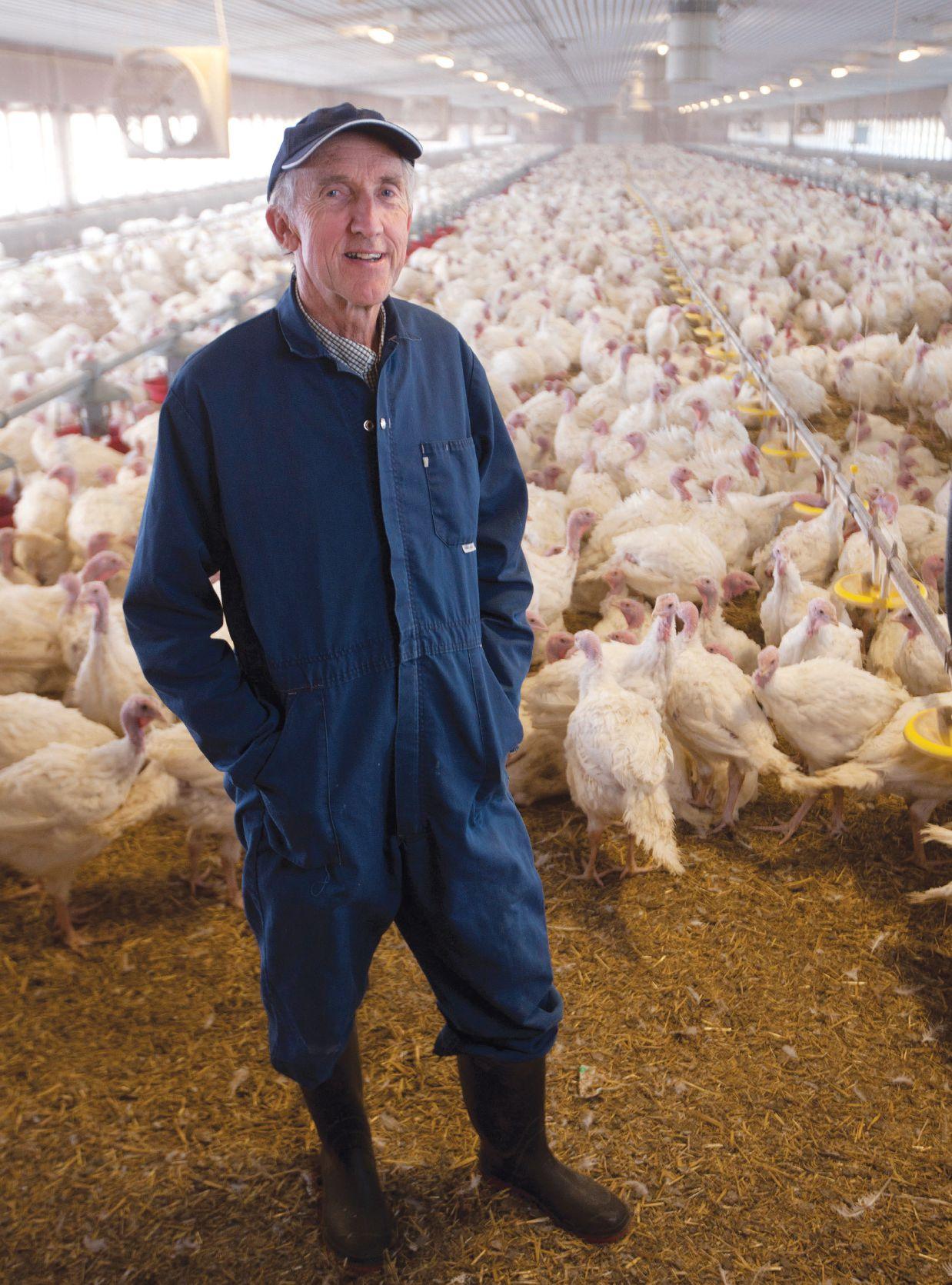

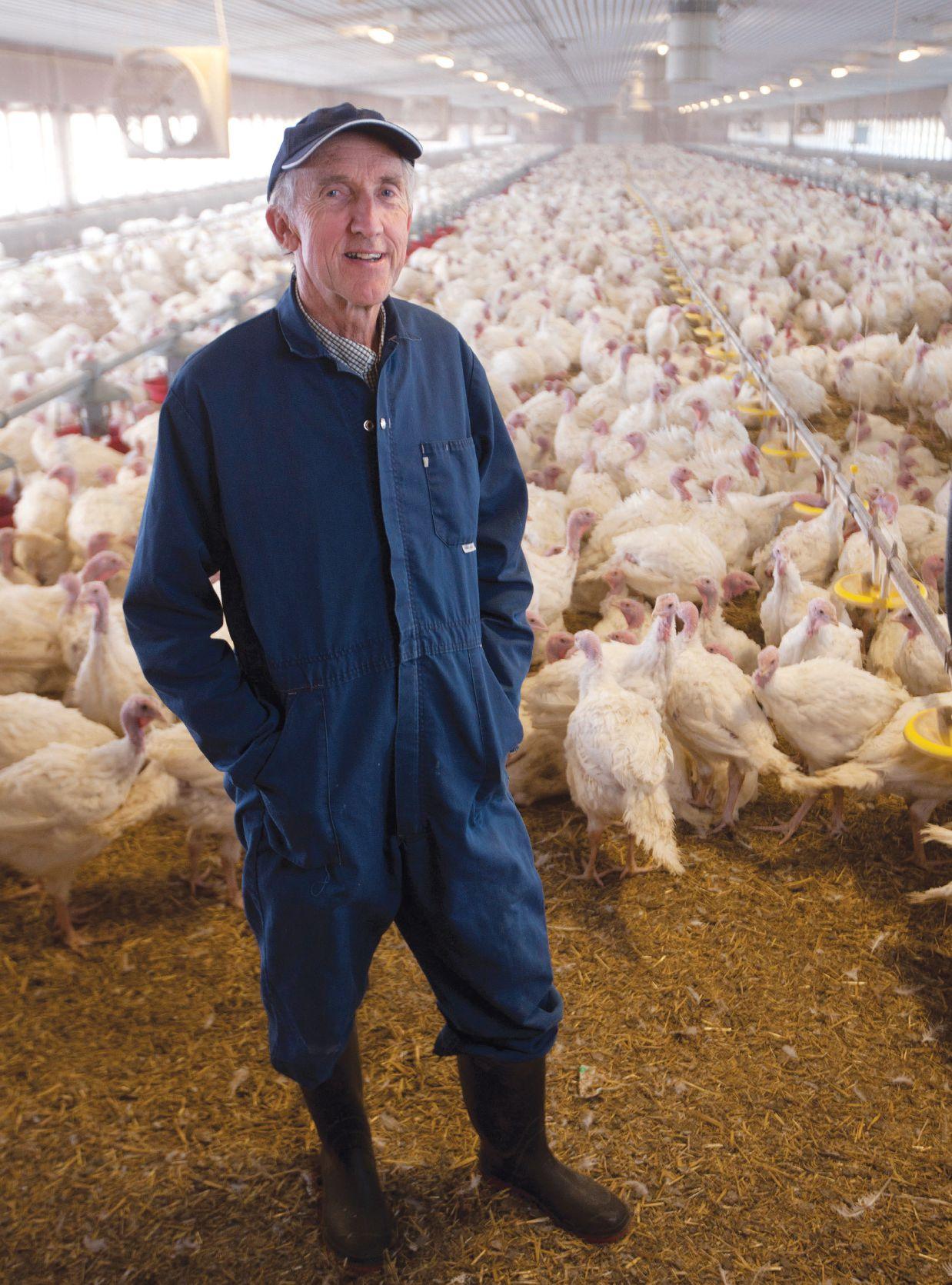

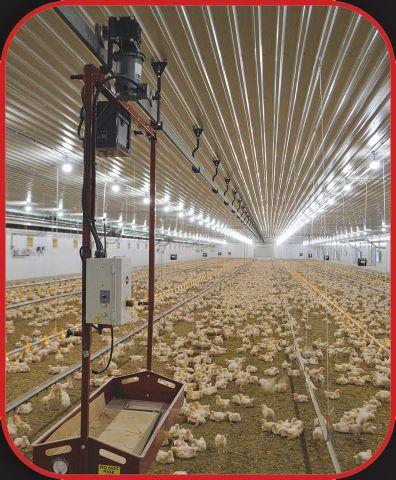

Producer and vet makes the case for built-up bedding.

By Karen Dallimore

The Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) requires producers to monitor litter quality daily. According to its 2018 Animal Care Program manual, currently under review from a gut health and food safety perspective, farmers must also clean out litter after each flock and replace it with clean bedding material.

Similarly, the Turkey Farmers of Canada’s 2010 Flock Care Manual stipulates that producers must clean out combined brooder and grow-out barns after every flock with a recommended downtime of 14 days. In addition, it says farmers need to completely clean out growout barns at least once per year.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. producers commonly use deep litter.

“ What the Americans do is dramatically different than us,” said Lloyd Weber, a well-known Ontario-based poultry veterinarian and a poultr y farmer. Speaking to the Poultry Industry Council Science in the Pub event in September 2018, Weber, who has grown out many crops of turkeys on the same litter and has grown out one crop of broilers back in 1978 with good success, made the case for having another look at reusing litter in poultry barns.

Our birds have evolved, said

Weber. They’re drinking 40 per cent more water than they did in 1985, he explained, meaning that there is 40 per cent more water going into that barn, into the birds and into the litter. For this reason, he said litter may not be at the ideal moisture content – something to monitor as the genetics, nutrition and management of our flock changes.

A ll birds are growing faster. Some producers use air exchangers to keep the heating costs down. We have new heating systems such as in-floor, hot water, and radiant tubes. There are new feed programs as well. Indeed, they’re not just standard broilers anymore. And more changes are coming: Weber predicts that in the next three years all chickens will be raised without antibiotics (RWA).

All this said, is it a good time to have another look at reusing litter?

The most obvious plus in reusing litter is the cost savings, along with lessening the actual job of cleaning out the barn. The deep litter provides a cushioning effect as well as adding extra heat.

The biggest drawback to reusing litter is managing the moisture and ammonia levels.

Check the litter every day with a moisture meter, suggested Weber. It’s a case of getting your M.B.A., he recommends: “Management by Being Around.” He is adamant that you must be in the barn, not just looking at your cell phone.

Twenty to 25 per cent litter moisture is perfect for cocci cycling and dust control. If you clearly see your footprint, it’s too wet.

Is ammonia increased by reusing litter? It depends on management, Weber said. With high humidity it

can be an issue all year around. The association between ammonia and moisture has been well validated.

Ammonia contributes to poor air quality, along with CO2 , dust, humidity and temperature. It irritates the lining of the respiratory system, increases mucous production and inhibits clearance of debris and pathogens from the trachea.

CFC says ammonia exceeding 25 ppm is unacceptable. At high levels over 50 ppm you can smell it – your eyes are burning. It can cause blindness in birds, airsacculitis, foot pad lesions and leaves the birds more susceptible to viral infections and secondary infections leading to condemnations. Feed conversion may be increased by up to eight points and final body weight may decrease by up to 0.25 pounds.

According to unpublished work from the University of Georgia, high levels of ammonia may also exacerbate incomplete vaccination – exposed birds are not as well protected. Many producers have acclimatized to higher ammonia levels in the barn, therefore the use of ammonia meters would be advantageous.

“It’s called stress,” Weber said. We know that when birds are stressed the energy from feed that should be going into growth and performance is taken away. Ventilate a bit more and you will get a payback.

Although the reason is unclear, RWA flocks all seem to have loose droppings, which would add to litter wetness. Pushing diets to the limit could be adding excess protein, which contributes to higher ammonia levels, Weber said. He added that lowering the pH of the water to four or five could play a part as well.

Immunity through exposure?

From a biological standpoint, a greater volume of bedding not only has a better holding capacity for ammonia but it can also help to provide immunity to coccidiosis.

“The biggest problem we face growing birds without antibiotics is to get the amount of cocci just right so that they have immunity but they don’t break with necrotic enteritis,” Weber said.

On old litter there are more oocysts present and the birds get exposure early. It’s one case where a little bit of dirt is a good thing. Birds are coming into the barn with bacterial flora on chick box paper liners so it’s already there. You’re talking about the microflora – the good bacteria in the litter, Weber said, that helps to competitively exclude the bad.

Anastasia Novy is a veterinarian now working with Weber at Guelph Poultry Veterinary Services. As she told the meeting, there hasn’t been a lot of research on using fresh litter versus reused litter. One unpublished U.S. study found the highest mor tality from necrotic enteritis (NE) with clean shavings and early exposure to the NE pathogen. Researchers suspected that birds weren’t exposed early enough to Clostridium perfringens – the organism causing NE.

“Fresh litter has more environmental bacteria, while the reused litter has more intestinal bacteria,” Novy explained. “It makes sense.” That load could be good commensal microflora but can also be p athogenic strains. This means that the birds are supplied with more intestinal organisms at an

earlier age, developed immunity to the pathogenic bacteria and that’s why they better tolerated the NE challenge during their most susceptible period.

Wet litter may be implicated in turkey cellulitis, where the contact of the skin to the wet litter results in the sternal bursa filled with fluid. It looks terrible, Weber said, and could get condemned. In his opinion these issues are tremendously litter related, but in the opposite w ay than you might think: in built-up litter there is less problem than when we clean out, possibly because of the reduced ammonia and moisture holding ability of new litter, or perhaps because new litter is more abrasive. The reason is unclear.

From the CFC Animal Care Program Manual 2018:

“Litter quality must be monitored daily. If the litter quality is inadequate (that is, too wet or too dry) immediate measures must be taken to improve it.

The following is a guide for determining the moisture level in the litter:

• When the moisture content is appropriate, the litter should be loosely compacted when squeezed; when squeezed into a ball, the ball should easily fall apart.

• When the moisture content in the litter is too high, the litter will tightly compact when squeezed; when squeezed into a ball, the ball remains intact.

• When the moisture content in the litter is too low, the litter will not compact when squeezed; it cannot be squeezed into a ball.”

Harry Huffman is an agricultural engineer based in London, Ont. He admits he’s not a fan of leaving litter in the barn for brooding turkeys for subsequent bird crops. Litter is commonly reused for grow-out turkeys; brooder barns are cleaned out after each flock.

With some turkey brooding barns, the producers actually want some extra moisture in the air to assist with various vaccinations, Huffman explained. Given the desired very hot barn environment (90 to 95°F), the barn air can become very dry (low relative humidity).

Some producers will disconnect the exhaust flue on their radiant tube heaters that would normally vent the products of combustion to the exterior of the building. These gases, primarily CO2 and water vapour, are then added to the room environment on a short-term basis to help raise the relative humidity.

If there is deep litter in the building producing extra ammonia then the added humidity will increase the absorption of the ammonia gas and reduce air quality. However, Huffman thinks this is a non-issue.

Cellulitis, described as an E. coli infection in the skin, is a major challenge that presents differently in chickens and turkeys. Weber said it’s the number one reason for condemnation in Canada and it amounts to a $20 million loss in broilers. If you have a cellulitis problem at processing with broiler chickens, clean out your barn and disinfect it – that would be the most beneficial thing you can do.

If you want to use old litter for turkeys, keep it dry, Weber said.

Drying agents can be useful for spot treatment but they can’t replace good management – look at controlling ammonia by ventilation or managing watering systems. Be tter drinkers mean less water wastage and make sure that nipple drinkers are at the right height for optimum use.

Top dressing reused litter may be of benefit to help keep the pack drier. Heating and ventilating before chicks come in to try to vola-

“What the Americans do is dramatically different than us.”

tilize ammonia may also be helpful, as would windrowing, composting, or de-caking the litter.

Deep litter may become an issue with machinery use in barns with lower ceilings, especially with modular loading, and water lines will need to be raised and lowered with the pack.

Can we reuse litter in Ontario?

“We think we could in certain situations, especially RWA and organic flocks,” Novy said. Management is always going to be something we need to focus on concerning ammonia, keeping moisture levels under control, and taking precautions before placement.

If exposure to pathogenic organisms outweigh the benefits – clean out! If performance is good, keep going. Maybe if the last flock did

well, it would be beneficial to keep that litter around? Downtime should always be respected, however. That is the key for any type of broiler production – experts recommend a minimum of 10 to 14 days. Always keep in mind that if there are performance-limiting viral or bacterial challenges then cleaning out, disinfecting and an appropriate length of downtime is imperative. As Canadians, we live in colder conditions than most American broiler chicken states, meaning that more heat is required to maintain air quality and keep ammonia down.

Deep litter won’t necessarily work for everyone, Weber concluded. Rules are for the majority; clean out may be best for the industry as a whole.

• Consistent Annual Genetic Progress

• Regional Technical Ser vice Exper tise

• More Saleable Yield

• WOG Yield Advantage

• Best Uniformity

• Supported by World Technical Suppor t (Hatchery to Processing)

Europe’s first AD plant operating solely on poultry litter at full capacity.

By Chris McCullough

Northern Ireland produces an estimated 260,000 tonnes of poultry litter each year.

This leads to the problem of how to dispose of it in an environmentally friendly way. Until now poultry farmers have relied on arable farmers to take the lion’s share of the litter. But a new solution is now in operation.

While the overall flock size in the country keeps on growing each year, the problem of how to handle the mountain of poultry litter produced from the birds intensifies.

In June 2017, the total poultry population in Northern Ireland was almost 25 million birds. Compare that with the figure back in 1981 at 12.2 million and it tells you the population has doubled in the past 36 years.

However, look more closely at the breakdown of the figures and its clear the broiler bird population has tripled in the same timespan to a total of 16.7 million

birds in June 2017. No matter how you look at it, that’s a lot of birds producing a lot of poultry litter.

Estimates from Northern Ireland’s department of agriculture, Daera, suggest the total amount of poultry litter produced in the country is around 260,000 tonnes annually.

That’s a lot of litter heaps. But now a solution to use 40,000 tonnes of that each year is in operation.

There have been many attempts to come up with a solution to solve the escalating concerns over poultry litter in Northern Ireland. After eight years in planning and 18 months building time, a new state-of-the-art biogas plant situated in the town of Ballymena is running at full capacity.

While there are similar plants in China, it is the first facility in Europe to run solely on poultry litter. According to the developers, it certainly won’t be the last one to be built.

The Tully Centralised Anaerobic Digestion Plant has a capacity to produce 3MW and cost $34.4 million to construct. It represents a huge investment for Dublin-based Stream BioEnergy Ltd. The compan y developed the project with Danish energy specialists Xergi, who also helped build the plant assisted by local firm BSG Ltd.

Stream BioEnergy managing director Kevin Fitzduff says the plant is operating well. “We are now running at full capacity and producing energy,” he says. “ The plant runs 24 hours per day and seven days per week.”

Heavy burdens of red tape as stipulated by the European Commission in Brussels means there are restrictions on the quantities of nitrogen and phosphates Northern Ireland farmers can spread on their land. While Daera investigated a number of small systems for utilizing manure over the years, none of them were actual-

Discover HATCHPAK® COCCI III, a new coccidial vaccine containing three attenuated, precocious strains that stimulate a strong natural immune response, while minimizing tissue damage.

There is a somewhat similar digester system running in Ontario that produces 500kW of electrical output from organic waste but not solely from poultry litter.

This one is based at Athlone Farms, which is a family-owned and operated 600-acre dairy and crop farm. The solid output from their digester produces bedding for their entire herd.

The Athlone anaerobic digester pumps liquid dairy manure and other liquid substrates into the anaerobic digester. The solid material is transferred into the anaerobic digester using a hopper and auger system.

The material is converted into biogas by microbes within the anaerobic digester at a temperature of approximately 30°C. This anaerobic digester system is a continuous system that has material entering and leaving it on an hourly basis. The material spends about 60 days in the system.

The resulting material, or the digestate, is stored and applied to the land when conditions allow. The biogas generated by the system is transferred to Combined-Heat and Power (CHPs), which covert the biogas into electricity and heat. The operation sells the electricity under a feed-in tariff contract.

Vicki Hilborn was part of the team that helped with the Canadian digester plant during its early days when she was employed by PlanET Biogas Solutions.

Says Hillborn: “I provided biological and technical support to the operation until 2015. This project was built to digest manure and other organic waste and to generate up to 500 kW of electricity.

“The capacity for the system to treat poultry litter varied on the other substrates available to this operation. Normally it was limited to 1.5 to two tonnes per day.

“This material was mixed with the dairy manure as the poultry manure was easily accessible to the farm, as the neighbour is a chicken farmer, and poultry manure has a relatively high biogas content.”

ly brought into commercial production.

For now, the manure used by the energy plant is delivered from dozens of poultry farms contracted to Moy Park, the country’s largest chicken processor now owned by Pilgrim’s Pride Corporation in the U.S.

“The litter comes from over 100 Moy Park contracted farmers in the local area. Xergi (the EPC contractor) provide operations services to the plant and have 12 full time staff on the site. In addition, many off-site jobs have been created through a range of contracting and professional services that the plant requires,” Fitzduff explains.

“Stream Bioenergy has five staff in total and is the original developer of the project. Stream Bioenergy is also an owner of the plant alongside the funders and we also provide management services to the project.”

Xergi has been contracted to manage operations at the Ballymena plant for the first 10 years, according to the chief executive officer Jorgen Ballermann, who says: “It has been a long development process and we appreciate the patience and willpower that Stream BioEnergy has shown.

“It’s not enough to have a good biogas plant. It is essential that the operating staff know how to manage biogas plants. Therefore, we always supply biogas plants in combination with a well-developed training program that ensures that employees can manage efficient operations of the plant.

“Based on this, Xergi has recruited and trained a group of local employees to manage operations. If there are unexpected challenges, we naturally have experts who come and assist the local staff, just as we have online access to the plant from our monitoring centre in Denmark,” Ballermann says.

When the poultry manure arrives on site it is fed into two industrial sized hoppers with walking floors that feed it to the next stage. It is then mixed with recirculated liquid before being pumped into the digesters.

During the mesophilic digestion process, bacteria break down the litter and produce biogas. The total digestion time is approximately 45 days and the biogas produced by the plant is fed into the two 1.5MW gas engines that generate electricity on site, which is then sold to the national grid.

The process is enabled by a unique device from Xergi called NiX technology. It converts the poultry manure raw material into energy. As part of the process, the machine strips the nitrogen from the litter. This allows it to digest up to 100 per cent poultry manure.

In normal circumstances, it is difficult to convert large amounts of poultry manure in biogas plants because it contains high levels of nitrogen, which inhibits the bacteria that produce biogas.

“The digestate is pasteurised before being separated into a fibre and liquid fraction. Most of the liquid fraction passes through an ammonia removal process before being mixed with the incoming poultry litter,” Fitzduff continues.

“The remaining liquid and the fibre digestate are a safe nutrient rich fertilizer that can be used by farmers. The electricity is exported to the grid and is enough to power 4,000 homes.”

Stream Bioenergy say it has plans to further develop potentially similar plants in Ireland. While the Ballymena plant is using up to 40,000 tonnes of poultry manure per year, this is only around 15 per cent of the total poultry manure produced in Northern Ireland.

“We have plans to develop further plans but are not in a position to announce these yet,” Fitzduff adds.

Water quality is often underestimated and yet it is such an important nutrient for each animal. Did you know that your animals drink twice as much water as the food they eat? When working with our Total Water Care concept, you are guaranteed the continual clearing of water lines to eliminate biofilm and simultaneously cleaning the water while maintaining taste. Total Water Care ensures that your water lines and water itself are toxic free and safe for you and your animals to consume.

The world’s first ‘no-kill eggs’ are on the supermarket shelves in Germany. Respeggt eggs first hit the shelves in Berlin in November and have since been rolled out in other parts of Germany. They’re the result of the success of Seleggt Acus, patented technology that determines a chick’s sex before it hatches. The innovation is being hailed a breakthrough in animal welfare technology.

Each year, over 45 million day-old chicks are slaughtered in Germany. Globally, that number is estimated to be somewhere between four to six billion.

Male chick culling has been a difficult-to-tackle issue, and one that has recently surfaced on the radar of animal welfare activists in Europe.

Chick culling entered the spotlight there when a video showing an Israeli animal rights group trying to shut down the machine used to shred day-old male

chicks was released. In the video, an activist is seen challenging a police officer to turn the machine back on. The video went viral, prompting the development of a more humane solution.

One of those solutions, Seleggt, was developed in Germany. It’s a non-invasive technology that is able to determine a chick’s sex before it hatches. M ale eggs, therefore, can be sold to supermarkets or used as feed rather than macerated.

The big news is that the technology is now non-invasive, says Carmen Uphoff, assistant of the general manager at Seleggt, in an interview at EuroTier in Hanover, Germany. In the earlier stages of its development, Seleggt extracted liquid from hatching eggs for hormonal analysis using a needle. While the needle worked well, it was incredibly slow, Uphoff noted. Following each pinprick, the needle needed to be cleaned. This was done to avoid hygiene issues and

cross contamination during the process.

Every two years, EuroTier, the world’s leading trade fair for animal production, presents 26 products with one gold and 25 silver Innovation Awards.

An independent expert committee appointed by the DLG (the German Agricultural Society) determines the winners. Seleggt won a silver medal at EuroTier 2018.

It uses a laser that makes a tiny 0.3 mm-wide pinhole, a process that is both non-invasive and completely hygienic. Air pressure pushes the liquid, called allantois fluid, out of the tiny hole.

The process – called endocrinological analysis – works much the same as a human pregnancy test where a chemical marker detects a hormone present in female eggs. The results are displayed through a colour change, which indicates the presence of a male or female embr yo. Female hatching eggs are returned to the incubator, while male eggs

are stamped and moved to a refrigerator, which stops the development of the egg. The procedure takes place on day nine of 21.

The process takes just one second per egg for a total of 3,500 to 3,600 eggs per hour. One machine can identify 60,000 to 70,000 eggs per day, assuming it’s operating for 18 hours a day. Samples are automatically collected, so human hands need not touch the eggs.

While male eggs in Germany are currently being sold in superstores, there are other uses for them as well, explained Uphoff. Male eggs could also be used in pig feed to address health issues, he says.

“We have a huge problem with diarrhea with piglets,” he says. “Today, you have normal egg powder in the recipes for the feed of piglets. The problem is that egg powder is a normal food for humans as well, so it’s expensive. It’s also a waste of a good product since you put it back into the food production chain,” he adds.

It uses a laser that makes a tiny pinhole, a noninvasive process that is also hygienic.

Similar technology developed in Canada

In Canada, researchers from McGill University, with support from the Egg Farmers of Canada, are developing similar technology, called Hypereye.

Hypereye is a non-invasive egg sex identification tool that uses hyperspectral imaging to identify infertility and gender of day-old chicks, instead of testing fluid inside of the egg for the presence of hormones.

In July of last year, the Lawrence MacAulay, minister of agriculture and agri-food, visited the farm of Egg Farmers of Canada chairman Roger Pelissero, where he announced an investment of $844,000 in support of Hypereye research.

By Melanie Epp

Currently, European Commission (EC) directives on the protection of chickens kept for meat and egg production allow beak trimming. However, some countries, like Austria, The N etherlands, Germany and most of Scandinavia, have banned the controversial practice outright. Others, like the United Kingdom, are working towards a ban, but not without debate. A cross the continent, opinions and perspectives vary.

Two EC directives govern beak trimming in Europe: one in broiler production, the other in egg production. Directive 1999/74/EC for laying hens allows beak trimming, while Directive 2007/43/ EC for broilers permits beak trimming only in certain cases.

Annex point eight of 1999/74/EC states: Without prejudice to the provisions of point 19 of the Annex to Directive 98/58/EC, all mutilation shall be

p rohibited. In order to prevent feather pecking and cannibalism, however, the Member States may authorize beak trimming provided it is carried out by qualified staff on chickens that are less than 10 days old and intended for laying.

Beak trimming is banned in the Scandinavian countries of Norway (1974), Finland (1986), Sweden (1988) and Denmark (2013). The practice was also banned in Austria in 2013, and more recently in The Netherlands, since September 1, 2018.

Unlike bans that are driven by policy, activists or retailers, the ban in The Netherlands came in response to consumer demands for eggs from birds with intact beaks

“I think that made it more acceptable to the industry, because if the person who buys your eggs places those demands, you are more likely to respond

than when it’s prescribed by the government,” says Bas Rodenburg, professor of animal welfare at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Utrecht University.

So far, the transition is going smoothly, he says. Farmers and advisers are k een to learn more about research on enrichment, rearing, nutrition and genetics.

Farm size could be contributing to ease of transition. A typical poultry barn in The Netherlands houses 30,000 birds. Each barn, however, is split into five compartments of 6,000 birds. Keeping hens in smaller compartments helps to reduce problems like feather pecking, Rodenburg says.

“You can also see clearly, for instance, when it’s a nutrition issue,” he adds. “When you see feather pecking develops in the back of the house, but in the front the birds are fine, you also know that it’s due to the fact that the birds in the front are eating all the larger particles, and

the birds in the back are lacking.”

Housing birds in smaller compartments also lowers panic and overall movement in the house, he says.

After watching the transition in The Netherlands, Rodenburg believes production of birds with intact beaks is possible. “You might have to accept that it’s not always smooth,” he said. “But you could have, on average, higher mortality due to pecking problems.”

Rodeburg is vice-chair of the EU COST Action GroupHouseNet. The aim of the network is to provide the European livestock industry with innovations in breeding, as well as management tips for intact pigs (tails) and poultry (beaks) that are being transitioned to large group housing systems.

Group housing is associated with increased risks of damaging behavior among animals, such as feather pecking, aggression and cannibalism in laying hens. GroupHouseNet brings together researchers and industry partners that deal with animal breeding and genetics, animal nutrition, epidemiology, engineering, animal behavior and welfare, epigenetics,

immunology, (neuro) physiology, economics and ethics.

The network’s activities are not only of interest to Dutch and German farmers. Rodenburg says there’s been interest from other countries as well, including farmers from the Balkan region and Eastern Europe. This year a producer meeting will be held in Slovenia to inform producers about management practices that help to control feather pecking.

It wasn’t Dutch consumers that drove its farmers to halt the practice of beak trimming. A large percentage of Dutch farmers sell eggs on the German market, a nd in order to do so, they must be in compliance with regulations set out by KAT.

KAT is a supervisory body that oversees the origin and traceability of eggs from alternative poultry rearing methods. The association operates in Germany and neighboring European countries.

A ccording to KAT managing director Dietmar

hybridturkeys.com

At Hybrid, you’re a partner not a customer. Partnership means reliable access to our global supply chain. It means a team of industry experts focused on your business. It means you can count on us every step of the way. Our world is all about you.

Maintain complete control during load-out, cleaning and restocking with Cumberland’s scenario feature for EDGE®. The bypass option allows for system changes with the press of a button. he EDGE® esponds with self-diagnostics, triple layer protection ith the next generation of controls. g T re wi

for your custom solution? Ready Find your dealer and learn more at cumberlandpoultr y.com

Tepe, approximately 95 per cent of egg German farmers are connected to the system. “Only a few small German farms do not belong to the KAT system,” he says. “The German food trade has made the KAT logo on egg packaging obligatory.”

When the ‘ban’ was first introduced in 2016, it was voluntary. During the voluntary transitional period, KAT assisted its members by providing information, including how system participants can best handle various potential situations. On September 1, 2018, however, KAT introduced a new standard for beak trimming stating that every product marketed under the label, including shell eggs, liquid egg and egg powder, must come exclusively from laying hens with untreated beaks.

In order to avoid possible negative consequences such as cannibalism or feather pecking, Tepe says German laying hen farmers use material such as mineral salt pick stones and coarser bedding. “In principle, measures should be found to make the hens peck, as this corresponds to their natural behavior,” Tepe says.

Various training courses and workshops were also offered to laying hen farmers by industry associations.

At the moment it is estimated that up to 80 per cent of EU laying hens are still beak trimmed. Rodenburg believes that more will move towards intact beaks, though, especially once the larger egg producers make the switch and show that it is indeed feasible. Not everyone is ready, though.

Change, Rodenburg says, usually starts in Scandinavia and slowly trickles down and then east through Eu rope. As long as EU regulations allow beak trimming, producers are not obligated to discontinue the practice. They can continue to export eggs to neighboring EU countries as well. Until bans on the practice spread further, eggs from intact birds will continue to fetch a higher price, Rodenburg says.

Countries that don’t yet have a ban on beak trimming aren’t simply waiting for EU regulations to force change. Some just aren’t ready to transition just yet.

In the U.K., for instance, Christine Nicol, professor of animal welfare at the Royal Veterinary College, University of London, doesn’t think farmers are ready for a ban on beak trimming, partly because they are already wrestling with a range of other issues and pressures, like Brexit.

“Flock sizes are increasing in free-range systems, and many farmers are moving from colony cages to cage-free indoor barn systems,” Nicol says. “These changes may have welfare benefits, but also make flocks harder to manage and increase risks of pecking but also of other problems such as bone fractures.”

“If there was a more settled period for the industry and more consensus on best housing then farmers would be in a better place to move towards keeping birds with intact beaks,” she continued. “I feel U.K. farmers are simply juggling too many balls at present.”

Nicol believes the transition process could be accelerated if breeding companies were to work on developing breeds of chickens with naturally blunter beaks that do less damage.

“We know there is some variation in beak shape, but the heritability of this trait and its interactions with other traits requires more work,” she says. “But it would be good if farmers started to ask for naturally blunter beaks to encourage the breeding companies in this direction.”

“There could be a very nasty transition period where bird welfare is terrible.”

While there are benefits to eliminating the practice, Nicol reiterates her concerns. “The pros would be that farmers would ha ve to make changes that reduced risk of injurious pecking instead of considering these optional,” she says. “But in my opinion the risks are still currently too high – there could be a very nasty transition period where bird welfare is terrible.”

An innovative way to boost gut health.

By Lloyd Weber

Water quality has never been more important. The elixir of life, as water is known, gives farmers an early warning system for disease, and a delivery mechanism for medication and vaccines. Water is of such importance in any life that John F. Kennedy once said, “Anyone who can solve the water problems is worthy of two Nobel prizes- one for peace and one for science.”

Science tells us that chickens consume twice as much water as feed, so slight improvements in your water can have a significant impact on feed conversion, livability and disease. In the new era of reduced antibiotics, water treatment options such as acids and sanitizers will be crucial to your operation.

Evaluate the birds and equipment in the barn by asking yourself:

• Am I raising water lines correctly as they grow?

• Do I believe the myth that water treatments damage equipment?

• Are too many birds trying to access water at once? (too few nipples for number of birds?)

• Are the nipples leaking or plugged?

• Is the pressure in the system correct for age?

Next assess the quality of what the birds are drinking:

• How often is the water filter changed? (i.e. red sediment means high levels of iron, which feeds bacteria like E.coli)

• W hat is the water pH? (birds prefer

more acidic water - high pH can lead to plugged nipple drinkers and most sanitizers function better at lower pH values)

• Does my water have a high mineral content? (hard water has high calcium and magnesium which may plug up water lines)

• Does their water have fecal coliforms or E.coli? (preferably none)

• How often do I flush the water line? (weekly flushes are recommended (unless using chlorine dioxide) since biofilm is formed by stagnant water

and from adding medicines/chemicals to the water lines)

• What is the sodium, chloride and sulfate content? (high levels of these minerals can cause wet litter)

Is there a better way to clean and sanitize water lines? Hydrogen peroxide or chlorine bleach are the most common methods in the industry. Hydrogen peroxide alone is considered a good sanitizer at optimum levels and is not dependent on pH, but the shelf life and residual level

It’s simple arithmechick, whether you raise 4,000 chicks or 4 million. Victrio® is a preservative-free, antibiotic-free way to jump-start your chicks’ immune systems, preparing them to fight E. coli the natural way. Administered in-ovo at the hatchery, Victrio significantly reduces post-hatch mortality due to E. coli infection and supports your RWA production goals.

Ask your hatchery for Victrio chicks today. Learn more at Victrio.ca.

in the water lines is short. Chlorine bleach effectiveness is greatly r educed when the water pH is high, meaning greater than seven, which is the case in most water sources.

A promising disinfectant against bacteria and viruses is chlorine dioxide. It is less corrosive and more effective than bleach in the removal of iron. Chlorine dioxide is 2.75 times more active (even in contaminated water) and more reliable. Chlorine dioxide does not affect the smell or taste of drinking water. It is also effective in water that has high sulphur content.

Chlorine dioxide has the stability to disinfect in the pH range of three to 10 and studies show better taste and improved water intake. Another benefit is its effect on breaking apart biofilm (a complex substance created by bacterial and fungal organisms) and delaying the rate of its regrowth.

Chlorine dioxide is created through a chemical reaction by combining sodium chlorite liquid and an acid activator. Producing chlorine dioxide in a container (creating a stock solution) may put the farmer at risk of exposure to chlorine dioxide gas.

There are ways to do this safely – by making sure you always have the water in the container first and then add the chlorine dioxide liquid or powder components in the sequence provided by the manufacturer, or you can contain the reaction in the water line itself.

Two separate pumps controlled by a flow meter inject each chem-

Red sediment on your water filter, as pictured above, means high levels of iron.

ical directly into the water line. Some chlorine dioxide vendors provide automated systems with water measurement, treatment and sanitation components.

Are organic acids the future, especially as antibiotic-free production increases? The science is clear –birds that consume water treated with organic acids have improved feed conversion, improved pathogen control and reduced gastric pH levels in the lower gut. Organic acids such as formic, propionic, sorbic and lactic, are useful for moderating gut flora in the bird.

Some antimicrobial activity happens at a pH of five to six, but most pathogenic bacteria important to poultry cannot survive

“We believe that lactic and formic acid have really positive effects within the bird.”

below a pH of four. For example, E. coli and Salmonella can’t survive when the pH is below four. A low pH is helpful in the bird’s crop and digestive system since these are major sites of bacteria colonization. To keep the pH level steady at 3.8 (or at least below four) the organic acid mix should contain a buffer (a salt).

Improved weights for age (breed standard weight gain per day of age) are often seen when using organic acids, particularly lactic and formic acid. This is likely due to the reduction of pathogenic bacteria as well as increasing the numbers of beneficial bacteria such as lactobacilli.

According to Arian de Bekker, who sees the positive effects of water acidification at MS Schippers Canada, “We believe that lactic and formic acid have really positive effects within the bird. Throughout the gastrointestinal tract, these acids optimize the chicken’s own enzymes and acids and allow the feed to be used more efficiently.”

There is also evidence that organic acids increase intestinal cell

Water treatment and disinfection prevent disease outbreaks and improve flock performance.

growth, allowing for more surface area and absorption of nutrients. Another reason to use organic acids is to potentially reduce the need of feed antibiotics. Antibiotics and organic acids both reduce competition against good bacteria, increase protein and energy digestibility, and reduce the significance of subclinical infections.

For water acidification to work well it is important to have clean water lines. Organic acids will have a reduced effectiveness in the presence of biofilm inside the water lines before it even reaches the birds.

Conclusion

Improving water quality with good management practices must be a new focus for every producer. Water treatment and disinfection are excellent methods to pr event disease outbreaks (by opportunistic pathogens such as E. coli, Salmonella sp. and Clostridium) and at the same time improving the performance of the flock.

Acidifying and sanitizing are great options for all types of poultry production, particularly those without the benefit of antibiotics in the feed. Water sanitation is critical as outbreaks can happen more frequently and with greater costs, particularly in raised without antibiotic (RWA) poultry production.

John Brunnquell gains new understanding through hen behavioural studies.

By Melanie Epp

The first time American egg farmer John Brunnquell walked into a cage-free barn everything he thought he knew about hen welfare was called into question. It was the early 1990s, and Brunnquell could recite the benefits of caged production by heart: Birds don’t walk around in their own manure, cages protect them from predators and they can be quickly fed if they get sick, he said. His visit to that cage-free barn changed everything and was the beginning of a lifelong journey to better understand hen behaviour.

But Brunnquell didn’t just recite the benefits of caged production; he believed them to be true. That said, a visit to his first cage-free barn in Indiana called into question everything he thought he knew about good welfare.

“I simply could not accept that the hens I was looking at in the cage-free barn had a poorer welfare than the caged hens I was familiar with,” he says.

“The event was transformative,” he continues. “I resolved that where I had influence I was going to have the hens under my control have a higher level of welfare than previously provided. We began the process of removing all cages and the education process of what does welfare really mean to a laying hen.”

Today, Brunnquell’s barns are 100 per

cent cage free and birds have access to outdoor pasture.

A third-generation egg farmer, Brunnquell, 56, grew up on a small family farm in the American Midwest with just 7,000 hens. Like many young rural Americans, Brunnquell joined 4-H. Later, he pursued a Bachelor of Science in Agronomy and a

Masters in Poultry Science, both from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Avian Ethology at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. Brunnquell is also president and founder of Egg Innovations, an egg company with a unique model for organic, free-range egg production. Egg Innovations

owns 65 layer barns. Each houses 20,000 birds. Brunnquell utilizes a contract model where the farmer owns the building and pays for labour and utilities, but Brunnquell owns the birds. Farmers are paid at the upper end of the market, he says.

All of the 1.5 million birds under the model have access to the outdoors every single day. Of the 65 barns, 60 per cent are located in Indiana; the remaining farms are located in Wisconsin and Kentucky. Barns have dedicated perch and scratch areas, as well as access to the outdoors. All 65 barns are designed exactly the same way, making them perfect for conducting research.

Brunnquell works closely with researchers from the Center for Proper Housing, Poultry and Rabbits (ZTHZ) in Switzerland. Led by Michael Toscano, ZTHZ researchers run small-scale trials with the goal of better understanding hen behaviour. Sometimes Brunnquell applies their research in his barns to see if results can be replicated at commercial scale.

In one of his projects, Brunnquell examined how light, particularly light wavelength, impacts hen behaviour during depopulation. The literature seems to suppor t the idea that blue LED lighting calms the birds, which leads to more injury-free depopulation.

Other research projects include finding novel ways to motivate hens to move around on range without paddocks, looking at the relationship between a farmer’s personality and flock productivity, and developing the first commercial non-beak trimmed layer flock in U.S.

Brunnquell believes that every animal is hardwired to certain behaviour, and if given the opportunity, animals will express those hardwired behaviours.

“In the case of a chicken, it is hardwired to perch, to scratch, to dust bathe, to pasture and to socialize,” he says. “If you give it an environment where it’s allowed to do that it will display those behaviours in high percentages.”

The benefits to allowing hens to display those behaviours are innumerable, says Brunnquell, who saw marked improvement in production. “Every time we took an incremental step, we saw improvements in production and drops in morbid-

ity and mortality,” he says.

And while each improvement was rewarding to Brunnquell as a producer, he understands that the sy stem isn’t for everyone.

“There is no benefit in criticizing producers who believe differently than you,”

he says. “Having said that, I always engage them in the conversation and ask: What are you really trying to accomplish?

“As in everything, it always comes down to management,” the egg producer adds. “The facility itself does not guarantee good welfare.”

By Alice Sinia

It may seem ironic, but even poultry facilities need a bird control plan. With bountiful food (including bird f eed) on the property, pest birds like pigeons, starlings and sparrows can easily become an issue if proper control methods are not taken.

From property damage to health risks, birds can stir up a lot of trouble. One of the most intelligent pests that pest control specialists encounter, birds can both adapt to and fight back against many traditional control methods.

Each year, birds cause tens of millions of dollars of damage to machinery, cars, roofs and ventilation systems, according to the International Association of Certified Home Inspectors.

Bird droppings contain acid and can corrode many types of building materials, clog gutters, discolor paint, r uin cloth awnings or even short out electrical equipment.

These damages can be expensive to repair and, in some cases, can even start a fire or lead to moisture damage in the building if left unattended. In a worst-case scenario, bird nesting could block drains or gutters, creating excessive standing water that causes the roof to collapse

While larger birds can be easily discouraged from claiming a building as their home, small birds like sparrows and swallows can be more difficult to deter. These birds require a more proactive approach and, in some cases, may even qualify as protected species in the area.

Birds can threaten the health of

employees, customers and guests as they can carry more than 60 diseases and spread micro-organisms that cause lung disease, toxoplasmosis and bird flu.

According to the World Health Organization, birds are the principal hosts or amplifying hosts for several viruses that can be spread to humans. Bird feathers can also cause respiratory problems in sensitive individuals and can cause flare-ups in allergies.

In addition to causing illness, birds carry bird mites, which are parasites that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Bird mites can jump from an infested bird or bird habitat onto a human, and the bites can cause small red bumps, intense itching, lesions and a crawling sensation on the body.

Bird droppings also can pose serious liability if left unaddressed as they can lead to dangerous accidents, such as slipping and falling.

For the most effective bird control, you should take a proactive approach

When removing bird droppings, make sure your staff is aware of the possible health risks and equip your team members with knowledge on the most effective ways to clean up the area.

If you have pest birds on your property, it’s important to know how attached they have become. Depending on their level of attachment, pest birds are increasingly difficult to remove. There are four stages of attachment birds pass through that lead to their decision to nest in a specific area:

1. Socializing

In this stage, birds simply gather to rest and communicate amongst one another. While flock sizes vary among bird species, any number of unwelcome birds can quickly become a nuisance to a business or work facility.

If nuisance birds think they can find a free meal on your property, they are likely to swoop in and claim their territory. Keeping the area clean of debris and m aking sure trash cans and recycling bins are covered and emptied on a regular basis can discourage birds from flying in when they are searching for their next meal. Make sure to remind employees and guests to keep outdoor areas clean and to never feed birds close by.

Many pest birds prefer to roost on flat surfaces and roof ledges. When birds reach this stage of attachment, they have found shelter and are regularly spending the night on your property. Inspecting rooftops and clearing standing water following a rain shower is a great start to prevent birds from turning your facility into their next home.

When birds decide to settle down, they will build their nests and start reproducing. In this nesting stage, birds have made the pr operty their permanent home and do not plan on leaving in the near future. At this point, many traditional control methods could become ineffective and additional assistance may be necessary to remove the birds.

Managing a bird infestation is a multistep process that begins with an inspection. Working with a pest management professional to look for feeding, roosting and loitering areas is essential to identifying and monitoring problem species around your facility. Once you’ve identified the source of the problem, you can work with a professional to install repellants, arrange for relocation or implement exclusion techniques.

C ontrolling natural and wild bird populations can be difficult, and it’s important that birds aren’t harmed during t he process. For the most effective bird control, you should take a proactive approach and assess your property for po -

tential hot spots and weak points before there is a problem. If you notice birds on your property, the best strategy is to contact your pest management provider to explore solutions that shoo birds away before nesting begins.

Watch for Canadian Poultry ’s first Pest Management Supplement included with the May issue. It will feature updates on pest control trends, new products, success stories and tips.

By Babak Sanei

It’s one of the most significant immunosuppressive diseases in the C anadian chicken industry. Infectious bursal disease (IBD), also known as Gumboro disease, is caused by a very highly contagious and immunosuppressive virus (family Birnaviridae ) in chickens.

The virus is hardy and survives in the poultry house for a long period, and common dry-cleaning practices (without complete washing and disinfection between crops) does not eliminate the virus and can affect the future flock placements. Proper breeder and broiler vaccination are also required for successful control of this costly disease.

There are two distinct types of IBD viruses, serotypes I and II, but only serotype I viruses are pathogenic to chickens. Based on virulence of the virus, IBDV is further divided into: classical strains (with high bursal lesions and mor-

tality of usually less than 20 per cent); ver y virulent IBD strains (with severe bursal damage and high mortality of greater than 20 per cent); and variant strains (that can potentially cause significant bursal lesions and immunosuppression and secondary infections with low mortality).

In Canada, based on available data, there have been no c onfirmed diagnosis of very virulent IBD in commercial broilers. However, variants IBD strains are quite common and can result in subclinical form of disease with no apparent clinical signs. With high level of infection, IBD variants can result in significant damage to bursa and result in subsequent immunosuppression.

The importance of proper vaccination and thorough cleaning and disinfection against IBD would become more prominent if other concurrent infections occur such as infectious bronchitis (IB)

Administering the right vaccine at the right age for vaccination is your best bet for success.

and virulent reoviruses that are currently present mainly in Ontario and Quebec.

If birds are infected with variants strains of IBD, the consequences depend on several factors. These include the age of birds, level of virus load, level of maternal antibodies (MABs) during the first two to three weeks of life, vaccination program and presence of other concurrent diseases.

Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) will affect the most important immune organ of young broiler chickens, Bursa of Fabricius. The negative impact on this organ during the life of a broiler flock directly affects the immune status and ability to resist

against other pathogens. If birds are infected at early ages (before two to three weeks), the developing B lymphocytes (main cells of bursa) will be permanently damaged and result in significant immunosuppression. The affected broiler flock is prone to secondary infections that can manifest in different forms such as colibacillosis due to E.coli, lameness (e.g., arthritis and tenosynovitis due to Staphylococcus, enterococcus and/or E.coli infections), higher susceptibility to coccidiosis (e.g. Eimeria tenella breaks) and higher condemnations (e.g., higher cellulitis) and overall poor performance. In the context of current spread of DMV strain of IB in Ontario and Quebec, control of IBD becomes even more important. That’s because if a bird’s immune system is compromised vaccination against IB would prevent ideal protection. Higher negative impact due to IB and possibly higher condemnation rate can be expected if concurrent infections of IB and IBD occur in the same flock.

On the other hand, if the broiler flock is infected at later stages of grow out (greater than three weeks of age), then it can still result in destruction of B-cells but the immunosuppression is temporary and the severity is milder. Under this scenario, producers may notice a mild increase in condemnations and slight increase in FCR and poor flock performance.

If flocks are very close to shipping then there might be no immediate negative impact on performance. However, the virus can gradually build up in

Ziggity makes upgrading your watering system fast, easy and affordable with its lineup of drinkers and saddle adapter products, designed to easily replace the nipples of most watering system brands with our own advanced technology drinkers. So if your watering system nipples show signs of wear, leaking and poor performance, just upgrade to Ziggity drinkers to start enjoying improved results! See how easy it is and request a quote at www.ziggity.com/upgrade.